英美合同法-讲义

- 格式:doc

- 大小:684.50 KB

- 文档页数:33

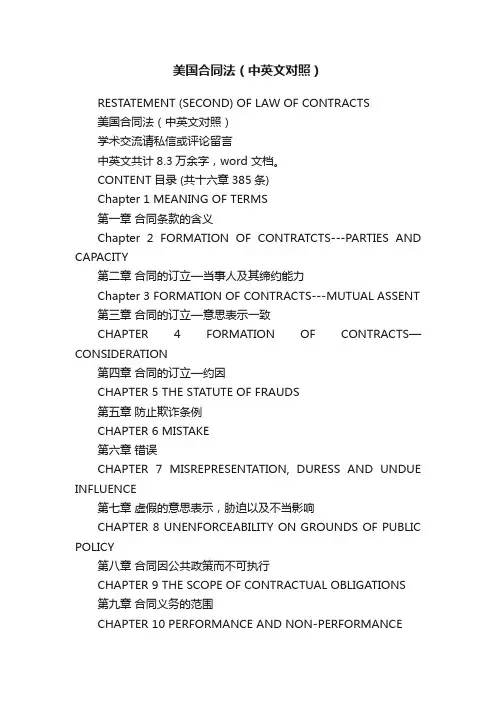

美国合同法(中英文对照)RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF LAW OF CONTRACTS美国合同法(中英文对照)学术交流请私信或评论留言中英文共计8.3万余字,word 文档。

CONTENT目录 (共十六章385条)Chapter 1 MEANING OF TERMS第一章合同条款的含义Chapter 2 FORMATION OF CONTRATCTS---PARTIES AND CAPACITY第二章合同的订立—当事人及其缔约能力Chapter 3 FORMATION OF CONTRACTS---MUTUAL ASSENT 第三章合同的订立—意思表示一致CHAPTER 4 FORMATION OF CONTRACTS—CONSIDERATION第四章合同的订立—约因CHAPTER 5 THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS第五章防止欺诈条例CHAPTER 6 MISTAKE第六章错误CHAPTER 7 MISREPRESENTATION, DURESS AND UNDUE INFLUENCE第七章虚假的意思表示,胁迫以及不当影响CHAPTER 8 UNENFORCEABILITY ON GROUNDS OF PUBLIC POLICY第八章合同因公共政策而不可执行CHAPTER 9 THE SCOPE OF CONTRACTUAL OBLIGATIONS第九章合同义务的范围CHAPTER 10 PERFORMANCE AND NON-PERFORMANCE第十章合同的履行与不履行CHAPTER 11 IMPRACTICABILITY OF PERFORMANCE ANDFRUSTRATION OF PURPOSE第十一章履行不能和履行目的落空CHAPTER 12 DISCHARGE BY ASSET OR ALTERATION第十二章双方合意或变更合同以解除合同义务CHAPTER 13 JOINT AND SEVERAL PROMISORS AND PROMISEES第十三章连带允诺人和受允诺人CHAPTER 14 CONTRACT BENEFICIARIES第十四章合同受益人CHAPTER 15 ASSGINEMNT AND DELEGATON第十五章合同权利的转让与合同义务的转托CHAPTER 16.REMEDIES第十六章违约救济部分章节示例如下:Chapter 1 MEANING OF TERMS第一章合同条款的含义§1. CONTRACT DEFINED 合同定义A contract is a promise or a set of promises for the breach of which the law gives a remedy, or the performance of which the law in some way recognizes as a duty.合同指的是一个允诺或一组允诺,如果违反此允诺,则法律给与救济;如果其履行了允诺,则法律以某种方式将其视为一项义务。

论英美合同法中的对价制度引言合同是商业交易中的基本法律形式,而合同法中的对价制度是合同法中一个重要的概念。

本文将以英美合同法为基础,探讨对价制度在合同法中的地位、原则和适用。

对价的定义和地位对价是指合同当事人为了达成协议而作出的相互交付一定权益的行为。

对价在合同法中占据着重要地位,它是合同成立以及合同履行的基础。

对价制度的基本原则1. 等价原则等价原则是对价制度的基本原则之一。

按照等价原则,合同当事人应当在交换中获得相对等的价值。

这意味着对价应当具有一定的价值,并且相互之间价值相近,不应当存在明显的不对等情况。

2. 价格自由原则价格自由原则是对价制度的另一个基本原则。

按照价格自由原则,合同当事人在交换中的对价应当由市场自由决定。

合同当事人可以根据市场供求关系和价值评估来确定对价的金额或价值。

3. 诚实信用原则诚实信用原则是对价制度的又一个基本原则。

按照诚实信用原则,合同当事人应当在交换中保持诚实守信的态度,并履行诚实交易的义务。

合同当事人不能以欺诈、误导等行为获取不当优势。

对价制度的适用范围对价制度适用于合同法中的大部分合同,特别是涉及买卖、租赁和服务业务的合同。

对价制度对于保护合同当事人的权益和确保合同的有效性非常重要。

对价制度在不同合同类型中的运用1. 买卖合同在买卖合同中,对价通常是货物或者款项的交换。

买卖合同的对价制度要求卖方将货物交付给买方,而买方则需要支付相应的款项。

双方通过对价的交换来实现经济利益的转移。

2. 租赁合同在租赁合同中,对价通常是租金。

出租人提供房屋或者其他设备给承租人使用,而承租人则需要支付相应的租金。

租赁合同中的对价制度对于维护出租人和承租人的利益平衡非常重要。

3. 服务合同在服务合同中,对价通常是服务费用。

服务提供者根据合同约定提供相应的服务,而服务接受者需要支付相应的费用。

服务合同中的对价制度要求服务提供者提供高质量的服务,同时要求服务接受者履行相应的支付义务。

英美契约法中文译本英美法系的合同第一课简介教学模式:课教学目的:让学生学习历史发展合约,普通法法律关键点:历史上的合同法英语要求:阅读能力和相关案例的分析教学手段:实施结合课堂教学,说明和案例分析社会进步运动迄今的运动是一个从身份到契约。

亨利希缅因州《古代法》历史上的合同法:第十六世纪的面貌第十七、十八世纪的发展缓慢第十九世纪的最高点第二十个世纪“地位”的标准化关系例:1、给出一个二书回报的承诺给予50美元的下一周。

承诺给书回报的承诺给予50美元的下一周。

2、under上岛咖啡店,货物销售合同和价值500美元以上的必须是书面的才能执行。

如果没有书面证据,这样的合同,合同是不可执行。

3、合同杀人无效,法院将不在其执法援助。

4、签订了合同,未成年人和成人是无效的未成年人的选择。

学习一步一步:接受;同意;广告;拍卖;双侧;不真诚善意的;违反合同;容量;考虑;民法法系;公约在联合国国际货物销售合同;还盘;交易过程;损害赔偿;损害公平;胁迫;期待利益;预见性;欺诈;合同自由诚信;要约邀请;时间间隔;虚假陈述;错误提供证据规则;期权;帕罗合同相对性;约定estopple 承诺;公共政策;qausi-contract;合理地确定\\男人\价格、时间信赖利益;救济;重申撤销合同;;终止;不适当的影响;不当得利;统一商业代码执行单方面;合同;可撤销合同无效;有效;第二课第一章:合同的成立(一)要约教学模式:课教学目的:让学生的基本规则,提供收费关键点:提供的定义英语要求:阅读能力和相关案例的分析教学手段:实施结合课堂教学,说明和案例分析这是第一课的合同法在普通法。

从这个教训,我们将学习第一部分:合同的成立。

比较合同法中民事法律,除了要约和承诺,另一个元素,就是考虑,是必要的元素,形成一个合同。

这是杰出人物的共同规律。

在这一课,我们将学习规则的要约和承诺。

你要注意区别普通法和民法。

现在,让我们看看有关规则提供。

每个合同要求提供和接受。

Common law control of exclusion clauses(p104)普通法对免责条款的控制为了使免责条款在普通法上有效,它必须满足三个条件:1、它必须是合同的一个条款(即,该条款必须包含在合同内)2、它必须包括所造成的损害3、而且必须是合理的Incorporation of exclusion clauses(p105) 纳入免责条款排他性条款的合并规则一般与适用于一般合同条款的合并规则相同-Incorporation by signature 公司的签名如果签署了包含合同条款的文件,那么即使签署方没有阅读或理解合同条款,这些条款仍然是合同的一部分。

因此,如果文件已经签署,即使一方当事人不知道或不理解免责条款,则该免责条款也将是合同的一部分。

但是,如果对免责条款的效力有虚假陈述,已签署的合同可能全部或部分无效。

-案例一事实:莱斯特兰奇开了一家咖啡馆。

她从制造商那订购了一台有故障的香烟机。

她所签署的合同中包含了一个条款,“任何明示或暗示的条件、声明或保证、法定或其他在此声明的内容均被排除在外”。

莱斯特兰奇声称违反了1893年《货物销售法案》的一项条款,货物不适合用于目的。

她还说她没有见过这一条款,因此不知道其中的内容。

法理:当一份包含合同条款的文件被签署时,在没有欺骗或虚假陈述的情况下,签署该文件的一方受其约束,且该方是否阅读了该文件完全无关紧要。

-案例二事实:索赔人拿了一件湿衣服要洗。

她签署了一份文件,据称这份文件将免除干洗店对任何损坏的责任。

当被问及这个问题时,女店员说这个条款只包含衣服上珠子或亮片损坏的免责。

这件衣服被弄脏了,索赔人要求赔偿。

干洗店试图依靠免责条款的原则。

法理:索赔是成功的。

法院认为,由于店员的陈述,被告不能依赖免责条款。

法院说,免责条款只在损害珠子或亮片的情况下才有效。

-Incorporation by notice 公司的通知免责条款必须在合同签订前或签订时提出。

英美合同法讲座一、合同法的渊源(一)英国契约法的历史发展演变。

14 至 15 世纪,一般法新建立的违约伤害赔偿之诉填补了伤害诉讼令状最先只合用于暴力性的、直接的伤害行为的明显缺点,但它最先不过作为伤害诉讼的一个分支出现,也就是说,契约法出自于伤害诉讼这一渊源。

至 19 世纪,英国契约法最后形成。

这一方面是因为遇到大陆法系契约法的影响,汲取了大陆法系契约法的某些重要原则;另一方面,最重要的原由是英国资本主义工商业的迅猛发展和自由听任经济思潮的推进。

在这种背景下,英国契约法在“缔约自由”与“契约神圣”等口号下发展起来并最后形成。

进入 20 世纪后,契约法的基来源则没有发生重要变化,但是因为垄断经济的发展,国家干预经济生活的增强,缔约自由原则遇到极大限制。

此外,契约神圣原则也有所修正,因为社会发展状况瞬间万变,假如出现了某些在缔约时没法料想的事实,进而使契约目的落空或事实上不行能执行,法院能够依据案情排除契约,而不象过去那样一味依照契约条款严格执行,此即“契约(目的)落空”原则。

(二)美国合同法的渊源(1)《美国合同法重述》:从渊源上说,美国合同法是由判例法和拟订法共同组成的。

但是,判例法的发展是美国合同法发展的核心环节,判例法组成了美国合同法的主要渊源。

美国法学会从各州的大批判例中归纳总联合同法的基来源理和规则,写成《合同法重述》,“重述”初版达成于 1932 年,第二版则于 1979 年达成。

第二版其实不取代初版,但是许多地反应了本世纪美国合同法的发展。

《美国合同法重述》固然没有法律效劳,但是法官们常常授引,作为判案的指导。

( 2)《美国一致商法典》:《美国合同法重述》本世纪以来,美国法学会和州法一致专员会议向来致力于草拟并促进各州采用《一致商法典》简称“UCC ”。

《美国一致商法典》是美国商事法律不停一致的标记之一,它以合同法为主体,以买卖为中心,波及一系列商事关系的程序和制度,但其实不是对美国商事法律的全面编纂。

英美合同法讲座一、合同法的渊源(一)英国契约法的历史发展演变。

14至15世纪,普通法新设立的违约损害赔偿之诉弥补了侵害诉讼令状最初只适用于暴力性的、直接的侵害行为的明显缺陷,但它最初只是作为侵害诉讼的一个分支出现,也就是说,契约法出自于侵害诉讼这一渊源。

至19世纪,英国契约法最终形成。

这一方面是由于受到大陆法系契约法的影响,吸收了大陆法系契约法的某些重要原则;另一方面,最重要的原因是英国资本主义工商业的迅猛发展和自由放任经济思潮的推动。

在这种背景下,英国契约法在“缔约自由”与“契约神圣”等口号下发展起来并最终形成。

进入20世纪后,契约法的基本原则没有发生重大变化,但是由于垄断经济的发展,国家干预经济生活的加强,缔约自由原则受到极大限制。

另外,契约神圣原则也有所修正,由于社会发展状况瞬息万变,如果出现了某些在缔约时无法预料的事实,从而使契约目的落空或事实上不可能履行,法院可以根据案情解除契约,而不象过去那样一味按照契约条款严格执行,此即“契约(目的)落空”原则。

(二)美国合同法的渊源(1)《美国合同法重述》:从渊源上说,美国合同法是由判例法和制定法共同构成的。

然而,判例法的发展是美国合同法发展的核心环节,判例法构成了美国合同法的主要渊源。

美国法学会从各州的大量判例中归纳总结合同法的基本原理和规则,写成《合同法重述》,“重述”第一版完成于1932年,第二版则于1979年完成。

第二版并不取代第一版,但是较多地反映了本世纪美国合同法的发展。

《美国合同法重述》虽然没有法律效力,但是法官们经常授引,作为判案的指导。

(2)《美国统一商法典》:《美国合同法重述》本世纪以来,美国法学会和州法统一专员会议一直致力于起草并促使各州采纳《统一商法典》简称“UCC ”。

《美国统一商法典》是美国商事法律不断统一的标志之一,它以合同法为主体,以买卖为中心,涉及一系列商事关系的程序和制度,但并不是对美国商事法律的全面编纂。

根据目前多数州使用的1972年正式文本,法典分为10篇,分别是:总则;买卖;商业票据;银行存款和收款;信用证;大宗转让;仓单、提单和其他所有权凭证;投资证券;担保交易;账债和动产契据的买卖;生效日期和废除效力。

《A Brief Introduction To The Anglo-American Law ofContract》讲义CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO ENGLISH AND AMERICANCONTRACT LAW第一章导论Many students wrongly imagine that the law of contract is difficult in that it will deal with complicated commercial situations. They also think of contracts as complicated written documents only entered into on rare occasions such as accepting the offer of a job, renting or buying a house, or engaging in a major business transaction.In fact, most of us enter into contracts every day and the vast majority of them are less complicated. Buying a bus or train ticket, a cup of coffee or a book are all example of contracts and we hardly ever bother to record these affairs in writing, negotiate them in detail.Although it is usually fairly easy to recognize a contract once formed, it is by no means such an easy task to describe in general terms what a contract is. It is usually, perhaps universally, said that a contract is a legally enforceable agreement and that it is formed by the process of “Offer and Acceptance.” It is also said that the agreement must be supported by “consideration” for it is the presence of consideration that makes the agreement enforceable.The contract law course taught in this semester usually deal wi th the “general principles of contract”. We will not concern with those more advance fields such as contracts of employment, of the sale of goods between business and to consumers, of international sales, of the disposal or retention of intellectual property rights, of shipping, of insurance, and of construction deals. [Aims and Requirements]This chapter introduces some basic theory in Common Law system on contract law. The section A begins our survey with the definition of contract, which introduces a number of themes including the basis of contract and the conditions for enforcement of promises. Section B presents an overview of some theoretical issues and provides some very basic information that often emerges in class only incidentally and may therefore be missed by some students. Section C concentrates on the development of Anglo-American contract law in the past century. It is useful for the student to understand new characteristics of modern contract law.[Time Allocation] 4 hourPlease brief the case and provide me with a copy of your brief at the first class.SECTION A.THE MEANING OF “CONTRACT” AND BASIS OF CONTRACT第一节合同的定义和合同基础I. Meaning Of ContractPurpose and demandIn this certain part of the chapter we must cover the following purpose and demands: the students should master the definition of Contract. They will be familiar with the sources of contract law. The understanding of the differences between England and The USA is also very important.Main contentI.The Meaning of “Contract”A contract is a promise, or set of promise, for breach of which the law gives a remedy, or the performance of which the law in some way recognizes as a duty. (Restatement of the Law, Second, Contracts, Section1.)A contract is defined as an exchange relationship created by oral or written agreement between two or more persons, containing at least one promise, and recognized in law as enforceable.Briefly speaking, a “contract” is an agreement(a promise or a set of promise)that the law will enforce.A contract is a legally binding agreement between two or more parties or a set of legal binding promises made by one party or more. (See G.C. Lindsay, Contract, (3 rd, 1992) at 6~7.)Although this definition will not likely satisfy everyone, it does reflect the essential elements that everyone seems to accept:II. So there are five essential elements in a contract:1.An oral or written agreementProbably, the most important attribute of contract is that is a voluntary, consensual relationship. A contract is created only because the parties, acting with free will and intent to be bound, reach agreement on the essential terms of their relationship. It is the element of agreement that distinguishes contractual obligation from many other kinds of legal duty, such as the obligation to compensate for negligent injury or to pay taxes that arise by operation of law from some act or event, without the need for assent.Although agreement between the parties is essential to the creation of contract,the question of what constitutes legally sufficient agreement can be difficult;the question is discussed in detail later. For the present, it is sufficient to point out that the law does not demand an inquiry into the mindsof the parties to decide whether they had formed an actual intent tocontract. Such an investigation into the actual thoughts and understanding of a party (called subjective intent) would not adequately protect the other party’s reasonable reliance on apparent intent, as portrayed by words and conduct. Also, because the only means of establishing the true state of mind of a person is the testimony of that person, evidence of true intent is likely to be unreliable and colored by self-interest. Therefore, in deciding whether a person agreed to a contract, the law gauges intent objectively. That is, it evaluates the person’s overt acts—words and conduct—to decide whether they reasonably signified an intent to enter the transaction.The concept of volition must also be approached with caution. Although a contract is a voluntary relationship, this does not mean that a party must be completely free of all pressure and must exercise unfettered free will. It is inevitable and tolerable that a party suffers some degree of compulsion from personal circumstances, desires, and needs, and from external market forces. However, where this pressure becomes too intense and is taken advantage of by the other party, it undermines volition and negates the apparent accent. The definition also indicates that agreement may be oral or written. Under a legal rule called the statute of frauds, certain specified contracts must be recorded in writing and signed to be enforceable. However, unless a contract falls within the statute of frauds, it is fully binding in oral form. It is common for both lay persons and lawyers to use the word “contract”to refer to the document setting out the terms of the agreement that is signed by the parties. Strictly speaking, the document is not the contract, but merely the memorandum or record of the contract. The contract is the legal relationship that arises from the agreement that may or may not be recorded in a written memorial.2.The involvement of two or more personsAs with tangos, it takes two to contract. This proposition seems so self-evidentthat it is hardly worth mentioning. Unlike the tango, however, a contract is notconfined to two participants. There can be as many parties to a contract as the needs of the transaction dictate. In fact, multiparty contracts are common.3.An exchange relationshipAs mentioned earlier, a contract is a relationship. By entering into the agreement, the parties bind themselves to each other for the common purpose of the contract. Some contractual relationships last only a short time and require minimal interaction. For example, a contract for a haircut involves a fairly quick performance by the hairdresser, followed by the fulfillment of the customer’s payment obligation. Other contractual relationships, such as leases or long-term employment or supply contracts, could span many years and require constant dealings between the parties, regulated by detailedprovisions in the agreement.The essential purpose of the contract relationship is exchange. It lies at the heart of contract. Contract and trade go hand in hand: because trading is a vital and indispensable facet of our society, contract law exists to facilitate it.In other words, the very essence of contract is the reciprocal relationship in which each party gives up something to get something. These “somethings”are as varied as one could imagine: a goatherd may promise to trade a goat to a miller for a sack of flour; an inventor may trade the rights to her idea for a promise by a manufacturer to develop the idea for mutual profit; a fond uncle may promise his nephew money in exchange for an undertaking not to drink, smoke, and gamble. These situations vary greatly. Some involve tangible things, others intangible rights. Some of the promises have economic value, others do not. Yet their basic format is the same-a bargain has been reached leading to a reciprocal exchange for the betterment (real or perceived) of both parties.4.At least one promiseAs already stressed, contract is a relationship. If two people chat for a few minutes at a reception and then part with no intention of ever seeing each other again. Their encounter would not likely be described as a relationship. So as for contract, instantaneous exchanges, even though consensual, do not constitute contracts. For a contract to exist, there must be a promise-that is, some commitment for the future, some assumptions of liability lasting beyond the instant of agreement. This is because is neither party makes a commitment, there is nothing to enforce and no need for the law of contracts to be concerned with the exchange.III. A few illustrationsThe concept of promise or commitment needs explanation and refinement. A promise is an undertaking to act or refrain from acting in a specified way at some future time. This promise may be made in clear and express words, or it could be implied – that is, inferred from conduct or from the circumstances of the transaction. Furthermore, as the definition indicates, only one promise needs to be made for a contract to come into existence.Where at the instant of contracting, promises remain outstanding on both sides, the contract is called bilateral. Where, at the instant of contracting, one party has fully performed and all that remains is a promise by the other, the contract is called unilateral.This sounds rather abstract. A few illustrations may help to make it more concrete.A. An Instantaneous Exchange: No Contract. Where an exchange is entirely instantaneous, and neither party makes any promises to the other, their exchange is not regarded as a contract. For example, say that while Rocky was walking along the bank of a river he encountered Eddy sitting on the shore next to his kayak. Rocky took $400in cash out of his pocket andoffered to buy the kayak from Eddy “as is” (that is without any warranty from Eddy as to its condition or quality). Eddy accepted the cash, and Rocky climbed into the kayak and paddled off. At this point, there is a simple,instantaneous exchange without any expectation that Rocky could complain if the kayak was substandard or defective. Each party has fully performed, and no promise has been made. The transaction is not a contract, in contract law, it is described as an executed exchange.B. A Promissory Exchange: Bilateral Contract.Change the facts inIllustration 1: Rocky said to Eddy, “I will buy that kayak from you provided that it is watertight. I will give you a check for $400 immediately.”Eddy replied, “It was watertight, I accept. Give me the check and take the kayak.”Even though the parties immediately exchange the check and kayak, the delivery does not end their duty of performance. By giving his undertaking Eddy has made a promise concerning the kayak’s condition, which will allow recourse if it does not meet the agreed standard. Similarly, Rocky’s check is not an immediate payment, but is nothing more than a commitment that his bank will pay the money upon presentation of the check. Thus promises exist on both sides after the moment of agreement, and a bilateral contract exists. This is called an executor exchange.C. A Promissory Exchange by Implication: Bilateral Contract.InIllustration 2 Eddy made an express promise that the kayak was watertight. However, it is not always necessary for promises to be stated in express terms. Often, the circumstances of the transaction, the conventions of the marketplace, or the policy of the law imply a promise even in the absence of promissory language in the agreement. Therefore, if it is commonly understood in the market that a seller warrants the fitness of what he sells, a simple exchange, without any express words relating to the kayak’s condition, will give rise to an implied promise that kayak is watertight.D. A Promise for Performance: Unilateral Contract. Finally, say thatRocky offered to buy the kayak for $400 and tendered his check. Eddy agreedto sell it “as is”, making it clear that he made no promise about its condition or quality. Rocky agreed, handed the check to Eddy, and paddled away. Here Eddy’s performance is instantaneous, but Rocky has made a promise of future performance (payment on presentation of the check). When, at the point of contract formation, only one party has a promise outstanding, the contract is unilateral.5.Legal Recognition of EnforceabilityContracting is often described as an act of private lawmaking by which persons create a kind of personalized “statute”to govern their relationship. One can only envisage contract as private legislation if it has the attribute of any law –recognition and enforcement through the compulsive power of the state, acting through its courts. It is therefore a hallmark of contract that it creates law binding on the parties and confers on them rights and obligations cognizable in law.[Key Points and Difficult Points]Essential elements which constitute a contract in Anglo-American contract law. [Questions]In what circumstances a contract could be seen as enforceable under American contract law?SECTION B.THE FUNDAMENTAL POLICIES OF CONTRACT LAW第二节合同法的基本原则[Main Content]I. The Fundamental Policies of Contract Law1.Freedom of contractThe consensual and voluntary nature of contract was stressed in previous section. The power to enter contracts and to formulate the terms of the contractual relationship is regarded in Common Law system as an exercise of individual autonomy-an integral part of personal liberty. The converse is also true: because contracting is an exercise of personal liberty, no one may be bound in contract in the absence of that person’s assent.While freedom of contract is a fundamental value, the exercise of this freedom by one person cannot be untrammeled. Like other liberties, it is delimited by corresponding rights held by other persons, and by state’s legitimate interest in appropriate regulation. It stands to reason that the absolute exercise of contract freedom by a dominant party will diminish or defeat the exercise of similar freedom by the weaker party. To avoid this happening, the courts or legislature must provide rules that protect the weaker party from being overwhelmed by the free exercise of contractual power by the stronger. Therefore, for example, a large insurance company or an employer may have its freedom of action curtailed so that it cannot impose harsh or one-side terms on an insured or an employee.Quite apart from the problem of ensuring a proper balance in the contractual freedom of the parties, the state may have an important interest in reaching an accommodation between freedom of contract and other fundamental values. For example, policies prohibiting criminal enterprise, protecting the environment, or forbidding anticompetitive behavior may require restrictions on the right to make certain contracts or on including certain terms in them. It is worthwhile to note that while contract liberty is an important value, it is subject to a variety of limitations that are justified either by the protection of corresponding rights in other persons or by the demands of other public interests.2.The morality of promise – Pacta Sunt Servanda(有约必守)The Latin maxim pacta sunt servanda (agreement must be kept) reflects a longstanding moral dimension of contract in contract law –that there is an ethical as well as legal obligation to keep one’s contractual promises. Contractsshould be honored not only because reliability is necessary to foster economic interaction, but simply because it is morally wrong to break them. The role that this basic moral value plays in contract law is subtle.3.Accountability for conduct and relianceIn determining whether or not a person agreed to a contract or specific contractual terms, the person’s manifested conduct by words or action is given more weight than her testimony about her actual intentions. An emphasis on the objective appearance of assent is important not only because evidentiary considerations but also because one of the fundamental values of contract law is that a person should be held accountable for words or acts reasonable manifesting intent to a contract, and that the other party, acting reasonably, should be entitled to rely on that manifestation of assent.The principles of accountability and reliance quality the value of voluntariness – volition is not measured by the true and actual state of mind of a party, but by that state of mind as made apparent to the outside world. Even if a person does not really wish to enter a contract, if he behaves as if the contract is desired and intended, that conduct is binding, and evidence of any mental reservation is likely to be disregarded.The value of protecting reasonable reliance is pervasive in contract law. It has both a specific and general aspect. It is specific in that a person who has entered a contract has the right to rely on the undertakings that have been given. If they are breached, the law must enforce them. It is general because when parties in numerous specific situations feel secure in relying on promises, the expectation arises in society as a whole that contract can be relied on, and that legal recourse is available for breach. This general sense of reliance, sometimes called “security of contracts” or “security of transactions,”is indispensable to economic interaction. If it did not exist, there would be little incentive to make contracts, which would not be worth the paper on which they are written.In summary, accountability for conduct that induces reasonable reliance is a vital goal of contract law. This is tempered by the consideration that in some cases manifested conduct is induced by illegitimate means, and one who uses such means cannot truly be regarded as having relied on the apparent assent.4.FairnessIn the contract setting, it must also be evaluated in light of the various goals and policies mentioned in this section. Nevertheless, it would be remiss not to at least draw to your attention that courts do not mechanically apply rules of law. Judges and juries are sensitive to the equities of individual cases and the circumstances of the parties, and where a mechanical application of rules achieves a result that seems to be unjust, there is likely to be some adjustment or even manipulation of the rule to avoid it.[Key Points and Difficult Points]The meaning and application of the principle of freedom of contract and fairness. [Questions]How is the principle of freedom of contract reflected in the American and English contract laws?SECTION C. Sources of Contract Law第三节合同法的渊源Purpose and demandAfter reviewing the definition of contract、promise and agreement. In this part of the first article we should get more knowledge of sources of Contract law, esp. the UCC.Main content1. EnglandThe Law of England today has three main sources or elements –the common law, statute law, and the law of the European Community.2. The USAIn most state of USA, most aspects of contract law are governed by case law (i.e., “common law”), rather than by statute. But, contracts are generally governed by common law except to the extent that legislation has been enacted to codify, change, or add it. The Uniform Commercial Code is such a statute.Briefly speaking, the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) is a collection of modernized, codified, and standardized laws that apply to all commercial transactions with the exception of real property.The goal of harmonizing state law is important because of the prevalence of commercial transactions that extend beyond one state. For example, goods may be manufactured in State A, warehoused in State B, sold from State C and delivered in State D. The UCC therefore achieved the goal of substantial uniformity in commercial laws and, at the same time, allowed the states the flexibility to meet local circumstances by modifying the UCC's text as enacted in each state.The only way to create uniform commercial law among the states is to draft a model statute and to persuade the legislature of each state to enact it. This task was undertaken jointly by two very influential national law reform organizations, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), and the American Law Institute (ALI).The Code, as the product of private organizations, is not itself the law, but only a recommendation of the laws that should be adopted in the states. Once enacted by a state, the UCC is codified into the state’s code of statutes. In the 1950s, the UCC was adopted by most states and the District of Columbia. (Louisiana has a civilian system, and the enactment of the UCC as a whole was not appropriate. Louisiana has enacted some portions of the UCC)Main Problems, priority and difficult points1. What is the main source in America?2. What is the main source in England?3. Compare to our country, which law we have not it?CHAPTER 2 FORMATION OF CONTRACT第二章合同的成立[Aims and Requirements]The students are supposed to know how contracts are formed inAnglo-American contract laws, the nature of promises, and the basic elementsfor a contract to be effective after the study of this chapter. They are also supposed to have the ability to analysis some leading cases andcomprehensively understand the decisions of these cases. The students are required to understand the difference between Anglo-American and Chinese theories on formation of contract.[Time Allocation] 8 hourFrom the first chapter we can know the primary basis for enforcing a promisein the common law system is that it was made as part of a bargained exchange. This requires an agreement between the contracting parties pursuant to whichthe bargain (a bargain is an agreement to exchange promises or toexchange a promise for a performance or to exchange performances) is made. The elements of this bargained exchange are typically stated to be offer, acceptance and consideration.Section A. OFFER第一节要约This chapter is concerned with issues of contract formation. The formation ofthe contract is the beginning of the parities legal relationship, but it is also the culmination of a process of bargaining. This is reflected in the expression that parties “conclude a contract,”which means, not that they have finished performing, but that they have completed the interaction leading up to the execution of a contract.In some cases, a deal may be struck very quickly, with a minimum of bargaining: one party may make a proposal that is accepted without modification by the other. In other cases the path to contract formation may be long and arduous. Initial proposals may lead to counterproposals, negotiations, and compromise. If the transaction is complex, each step in the process may require consultation with different corporate departments, technical experts, and attorneys. In either event, where this interaction is successful, there comes a time when the parties reach agreement and bind themselves to the relationship—a contract comes into being. Sometimes, this point can be clearly identified, but if there has been a lengthy negotiation or several communications back and forth, it may be hard to tell if a final and binding contract actually emerged from this process, and if so, at what point it came into being.Sometimes the creation of a contract is marked by the signing of a written memorial of the agreement. When this happens, it is relatively easy to fix the time of formation and the exact terms of the contract. However, this helpful indicator of formation is not always present because the parties may have formed a contract without recording it in a formal comprehensive writing. A contract could be contained in a series of correspondence or in some other collection of interrelated documents; it could have been made orally with the intention of later drafting and signing a written memorial or it may be partly written and partly oral or entirely oral. Such circumstances may create uncertainty and disputes over the question of whether a contract was formedat all, and is so, whether certain terms became part of it. The rules of offer and acceptance provide a framework for resolving these questions.I.The Basic ModelThe rules of offer and acceptance are based on a particular conception of howcontracts are formed. In the simple terms, they envisage that one person (called the offeror) makes an offer to another person (the offeree) to enterinto a contract on specified terms. The offer creates a power of acceptance in the offeree so that she can bring the contract into existence by signifying acceptance of the transaction on the proposed terms. If the offeree rejects the offer either expressly or simply by not accepting it within a particular time, the offer lapsed and no contract arises. If the offeree is interested in forming a contract, but not on the exact terms proposed, the offeree may respond by making a counteroffer, which has the effect of terminating the original offer and reversing the process: the original offeror now becomes the offeree with the power of acceptance. This are some variation and complications that could arise, as the following sections will show.II.Manifestation of Assent to be Bound1.An offer is a communication that creates in the offeree thepower to form a contract by accepting in an authorized manner.In the words of the Restatement, Second, Contractes, (herein referred to as Restatement) section 24, it must be a “manifestation of willingness to entry into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it.” Thus, the first element of an offer is a manifestation of an intention to be presently bound subject only to an appropriate acceptance.2.An offer maybe found where words arouse an expectation in themind of a reasonable person in the position of the offeree.An offer may be found where words arouse an expectation in the mind of a reasonable person in the position of the offeree that if he makes a promise or performs an act as requested, nothing further need be done by either party in order to form a contract. Words which arouse such an expectation create a power of acceptance in the offeree. On the other hand, words which arouse alesser expectation, merely inviting further discussion or soliciting an offer from the other party may be considered preliminary negotiations. Restatement section 26 provides:”A manifestation of willingness to enter intoa bargain is not an offer if the person to whom it is addressed knows or has reason to know that the person making it does not intend to conclude a bargain until he has made a further manifestation of assent.”Whether a communication is an offer or is simply preliminary negotiations is a question of fact. If the recipient is aware that the proposal is also addressed to other parties, it is less likely to be an offer as such conduct tends to negate an intention to be presently bound. Where intention to be bound is not clear, the more definite a proposal the more likely it is that a trier of fact will conclude that the party making it is willing to be presently bound.II. The Basic Elements of an Offer1.An offer must be manifested. It must necessarily be communicated tothe person to whom it is addressed. An offer cannot take effect until it becomes known to the offeree.2.An offer must indicate a desire to enter into a contract. To do thisit has to specify the performance to be exchanged and the terms that will govern the relationship. It is important to remember that as the creator of the offer, the offeror has control over what its terms will be.3.An offer must be directed at some person or group of persons.Although an offer is usually addressed to a specific person, it is legally possible to make an offer to a defined or undefined group. Where this happens, it is a question of interpretation if it contemplates multiple acceptances or may be accepted only by the first person to reply.4.An offer must invite acceptance. It may or may not indicate how andby what time this acceptance is to be communicated. If a mode and time for acceptance are prescribed, they must be followed. If these are not set out in the offer, the court must decide whether the acceptance was reasonable and timely.5.An offer must create the reasonable understanding that upon acceptance.A contract will arise without any further approval being required from theofferor.III. Difference between an Offer and a Preliminary Proposal1.The words used in the communication are different. Even wherethe language of the communication does not make its import absolutely clear, clues to reasonable meaning may be found in what was said. The use of terms of art, such as “offer,”“quote,” or “proposal” may be helpful but are not conclusive if the context indicates that they were not used in their legal sense.2. A communication that omits significant terms is not likely to bean offer. Because an offer is intended to form a contract upon acceptance,a communication that omits significant terms is not likely to be an offer.Therefore, the comprehensiveness and specificity of the terms in the communication are an important clue to its intent.3.An offer is directed to a particular person. The usual expectation isthat a person merely invites offers by the type of general dissemination, especially if recipients must meet certain qualifications or there id limited。