曼昆宏观经济学英语课后题答案

- 格式:doc

- 大小:923.00 KB

- 文档页数:54

Chapter 28Problems and Applications1. The labor force consists of the number of employed (142,076,000) plus the number of unemployed(7,497,000), which equals 149,573,000.To find the labor-force participation rate, we need to know the size of the adult population. Adding the labor force (149,573,000) to the number of people not in the labor force (76,580,000) gives the adult population of 226,153,000. The labor-force participation rate is the labor force (149,573,000) divided by the adult population (226,153,000) times 100%, which equals 66%.The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed (7,497,000) divided by the labor force(149,573,000) times 100%, which equals 5.0%.2. Many answers are possible.3. Men age 55 and over experienced the greatest decline in labor-force participation. This wasbecause of increased Social Security benefits and retirement income, encouraging retirement at an earlier age.4. Younger women experienced a bigger increase in labor-force participation than older womenbecause more of them have entered the labor force (in part because of social changes), so there are more two-career families. In addition, women have delayed having children until later in life and have reduced the number of children they have, so they are in the labor force for a greater proportion of their lives than was the case previously.5. The fact that employment increased 1.5 million while unemployment declined 0.6 million isconsistent with growth in the labor force of 0.9 million workers. The labor force constantlyincreases as the population grows and as labor-force participation increases, so the increase in the number of people employed may always exceed the reduction in the number unemployed.6. a. A construction worker who is laid off because of bad weather is likely to experienceshort-term unemployment, because the worker will be back to work as soon as theweather clears up.b. A manufacturing worker who loses her job at a plant in an isolated area is likely toexperience long-term unemployment, because there are probably few other employmentopportunities in the area. She may need to move somewhere else to find a suitable job,which means she will be out of work for some time.c. A worker in the stagecoach industry who was laid off because of the growth of railroads islikely to be unemployed for a long time. The worker will have a lot of trouble findinganother job because his entire industry is shrinking. He will probably need to gainadditional training or skills to get a job in a different industry.d. A short-order cook who loses his job when a new restaurant opens is likely to find anotherjob fairly quickly, perhaps even at the new restaurant, and thus will probably have only ashort spell of unemployment.e. An expert welder with little education who loses her job when the company installsautomatic welding machinery is likely to be without a job for a long time, because she lacksthe technological skills to keep up with the latest equipment. To remain in the weldingindustry, she may need to go back to school and learn the newest techniques.12 Chapter 28/Unemployment7. Figure 2 shows a diagram of the labor market with a binding minimum wage. At the initial minimumwage (m1), the quantity of labor supplied L1S is greater than the quantity of labor demanded L1D, and unemployment is equal to L1S−L1D. An increase in the minimum wage to m2 leads to anincrease in the quantity of labor supplied to L2S and a decrease in the quantity of labor demanded to L2D. As a result, unemployment increases as the minimum wage rises.Figure 28. a. Figure 3 illustrates the effect of a union being established in the manufacturing labormarket. In the figure on the left, the wage rises from w1U to w2U and the quantity of labordemanded declines from U1 to U2D. Because the wage is higher, the quantity supplied oflabor increases to U2S, so there are U2S−U2D unemployed workers in the unionizedmanufacturing sector.b. When those workers who become unemployed in the manufacturing sector seekemployment in the service labor market, shown in the figure on the right, the supply oflabor shifts to the right from S1 to S2. The result is a decline in the wage in thenonunionized service sector from w1N to w2N and an increase in employment in thenonunionized service sector from N1 to N2.Chapter 28/Unemployment 3Figure 39. a. When the Japanese developed a strong auto industry, U.S. auto demand became moreelastic as a result of increased competition. With more elastic demand for autos, theelasticity of demand for American autoworkers increased.b. Because the rise in auto imports made the demand for autoworkers more elastic, tomaintain a higher-than-competitive wage rate requires a greater reduction in the quantityof labor demanded. So the union had to choose between allowing the union wage todecline or facing the loss of many jobs.c. Given the trade-off faced by the union, the growth of the Japanese auto industry forcedthe union wage to move closer to the competitive wage.10. a. If a firm was not providing such benefits prior to the legislation, the curve showing thedemand for labor would shift down by exactly $4 at each quantity of labor, because thefirm would not be willing to pay as high a wage given the increased cost of the benefits.b. If employees value the benefit by exactly $4 per hour, they would be willing to work thesame amount for a wage that's $4 less per hour, so the supply curve of labor shifts downby exactly $4.Figure 4c. Figure 4 shows the equilibrium in the labor market. Because the demand and supply curvesof labor both shift down by $4, the equilibrium quantity of labor is unchanged and thewage rate declines by $4. Both employees and employers are just as well off as before.d. If the minimum wage prevents the wage from falling, the result will be increasedunemployment, as Figure 5 shows. Initially, the equilibrium quantity of labor is L1 and theequilibrium wage is w1, which is $3 lower than the minimum wage w m. After the law ispassed, demand falls to D2 and supply rises to S2. Because of the minimum wage, thequantity of labor demanded (L2D) will be smaller than the quantity supplied (L2S). Thus,there will be unemployment equal to L2S–L2D.4 Chapter 28/UnemploymentFigure 5Figure 6e. If the workers do not value the mandated benefit at all, the supply curve of labor does notshift down. As a result, the wage rate will decline by less than $4 and the equilibriumquantity of labor will decline, as shown in Figure 6. Employers are worse off, because they now pay a greater total wage plus benefits for fewer workers. Employees are worse off,because they get a lower wage and fewer are employed.。

曼昆微观经济学课后练习英文答案集团标准化办公室:[VV986T-J682P28-JP266L8-68PNN]the link between buyers’ willingness to pay for a good and the demandcurve.how to define and measure consumer surplus.the link between sellers’ costs of producing a good and the supply curve.how to define and measure producer surplus.that the equilibrium of supply and demand maximizes total surplus in amarket.CONTEXT AND PURPOSE:Chapter 7 is the first chapter in a three-chapter sequence on welfare economics and market efficiency. Chapter 7 employs the supply and demand model to develop consumer surplus and producer surplus as a measure of welfare and market efficiency. These concepts are then utilized in Chapters 8 and 9 to determine the winners and losers from taxation and restrictions on international trade.The purpose of Chapter 7 is to develop welfare economics—the study of how the allocation of resources affects economic well-being. Chapters 4 through 6 employed supply and demand in a positive framework, which focused on the question, “What is the equilibrium price and quantity in a market” This chapter now addresses the normative question, “Is the equilibrium price and quantity in a market the best possible solution to the resource allocation problem, or is it simply the price and quantity that balance supply and demand” Students will discover that under most circumstances the equilibrium price and quantity is also the one that maximizes welfare.KEY POINTS:Consumer surplus equals buyers’ willingness to pay for a good minus the amount they actually pay for it, and it measures the benefit buyers get from participating in a market. Consumer surplus can be computed by finding the area below the demand curve and above the price.Producer surplus equals the amount sellers receive for their goods minus their costs of production, and it measures the benefit sellers get from participating in a market. Producer surplus can be computed by finding the area below the price and above the supply curve.An allocation of resources that maximizes the sum of consumer and producer surplus is said to be efficient. Policymakers are often concerned with the efficiency, as well as the equality, of economic outcomes.The equilibrium of supply and demand maximizes the sum of consumer andproducer surplus. That is, the invisible hand of the marketplace leadsbuyers and sellers to allocate resources efficiently.Markets do not allocate resources efficiently in the presence of market failures such as market power or externalities.CHAPTER OUTLINE:I. Definition of welfare economics: the study of how the allocation of resources affects economic well-being.A. Willingness to Pay1. Definition of willingness to pay: the maximum amount that a buyer will pay for a good.2. Example: You are auctioning a mint-condition recording of Elvis Presley’s first album. Four buyers show up. Their willingness to pay is as follows:If the bidding goes to slightly higher than $80, all buyersdrop out except for John. Because John is willing to paymore than he has to for the album, he derives some benefitfrom participating in the market.3. Definition of consumer surplus: the amount a buyer is willing to payfor a good minus the amount the buyer actually pays for it.4. Note that if you had more than one copy of the album, the price in the auction would end up being lower (a little over $70 in the case of two albums) and both John and Paul would gain consumer surplus.B. Using the Demand Curve to Measure Consumer Surplus1. We can use the information on willingness to pay to derive a demandmarginal buyer . Because the demand curve shows the buyers’ willingness to pay, we can use the demand curve to measure c onsumer surplus.C. How a Lower Price Raises Consumer Surplussurplus because they are paying less for the product than before (area A on the graph).b. Because the price is now lower, some new buyers will enter the market and receive consumer surplus on these additional units of output purchased (area B on the graph).D. What Does Consumer Surplus Measure?1. Remember that consumer surplus is the difference between the amount that buyers are willing to pay for a good and the price that they actually pay.2. Thus, it measures the benefit that consumers receive from the good as the buyers themselves perceive it.III. Producer SurplusA. Cost and the Willingness to Sell1. Definition of cost: the value of everything a seller must give up to produce a good .2. Example: You want to hire someone to paint your house. You accept bidsfor the work from four sellers. Each painter is willing to work if the priceyou will pay exceeds her opportunity cost. (Note that this opportunity costthus represents willingness to sell.) The costs are:sellers will drop out except for Grandma. Because Grandma receives more than she would require to paint the house, she derives some benefit from producing in the market.4. Definition of producer surplus: the amount a seller is paid for a good minus the seller’s cost of providing it.5. Note that if you had more than one house to paint, the price in the auction would end up being higher (a little under $800 in the case of two houses) and both Grandma and Georgia would gain producer surplus.ALTERNATIVE CLASSROOM EXAMPLE:Review the material on price ceilings from Chapter 6. Redraw themarket for two-bedroom apartments in your town. Draw in a priceceiling below the equilibrium price.Then go through:consumer surplus before the price ceiling is put into place. consumer surplus after the price ceiling is put into place. You will need to take some time to explain the relationship between the producers’ willingness to sell and the cost of producing the good. The relationship between cost and the supply curve is not as apparent as the relationship between the It is important to stress that consumer surplus is measured inmonetary terms. Consumer surplus gives us a way to place amonetary cost on inefficient market outcomes (due to governmentB. Using the Supply Curve to Measure Producer Surplus1. We can use the information on cost (willingness to sell) to derive a2.the cost of the marginal seller. Because the supply curve shows the sellers’ cost (willingness to sell), we can use the supply curve to measure producer surplus.C. How a Higher Price Raises Producer Surplussurplus because they are receiving more for the product than before (area C on the graph).b. Because the price is now higher, some new sellers will enter the market and receive producer surplus on these additional units of output sold (area D on the graph).D. Producer surplus is used to measure the economic well-being of producers,ALTERNATIVE CLASSROOM EXAMPLE:Review the material on price floors from Chapter 6. Redraw the marketfor an agricultural product such as corn. Draw in a price supportabove the equilibrium price.Then go through:producer surplus before the price support is put in place.producer surplus after the price support is put in place.Make sure that you discuss the cost of the price support tomuch like consumer surplus is used to measure the economic well-being of consumers.IV. Market EfficiencyA. The Benevolent Social Planner1. The economic well-being of everyone in society can be measured by total surplus, which is the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus:Total Surplus = Consumer Surplus + Producer SurplusTotal Surplus = (Value to Buyers – Amount Paid byBuyers) +(Amount Received by Sellers – Cost to Sellers)Because the Amount Paid by Buyers = Amount Received bySellers:2. Definition of efficiency: the property of a resource allocation of maximizing the total surplus received by all members of society .3. Definition of equality: the property of distributing economicprosperity uniformly the members of society .a. Buyers who value the product more than the equilibrium price will purchase the product; those who do not, will not purchase the product. Inother words, the free market allocates the supply of a good to the buyers who value it most highly, as measured by their willingness to pay.b. Sellers whose costs are lower than the equilibrium price will produce the product; those whose costs are higher, will not produce the product. Inother words, the free market allocates the demand for goods to the sellers who can produce it at the lowest cost.value of the product to the marginal buyer is greater than the cost to the marginal seller so total surplus would rise if output increases.Pretty Woman, Chapter 6. Vivien (Julia Roberts) and Edward(Richard Gere) negotiate a price. Afterward, Vivien reveals shewould have accepted a lower price, while Edward admits he wouldhave paid more. If you have done a good job of introducingconsumer and producer surplus, you will see the light bulbs gob. At any quantity of output greater than the equilibrium quantity, the value of the product to the marginal buyer is less than the cost to the marginal seller so total surplus would rise if output decreases.3. Note that this is one of the reasons that economists believe Principle #6: Markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity.C. In the News: Ticket Scalping1. Ticket scalping is an example of how markets work to achieve anefficient outcome.2. This article from The Boston Globe describes economist Chip Case’sexperience with ticket scalping.D. Case Study: Should There Be a Market in Organs?1. As a matter of public policy, people are not allowed to sell their organs.a. In essence, this means that there is a price ceiling on organs of $0.b. This has led to a shortage of organs.2. The creation of a market for organs would lead to a more efficientallocation of resources, but critics worry about the equity of a market system for organs.V. Market Efficiency and Market FailureA. To conclude that markets are efficient, we made several assumptions about how markets worked.1. Perfectly competitive markets.2. No externalities.B. When these assumptions do not hold, the market equilibrium may not be efficient.C. When markets fail, public policy can potentially remedy the situation. SOLUTIONS TO TEXT PROBLEMS:Quick Quizzes1. Figure 1 shows the demand curve for turkey. The price of turkey is P 1and the consumer surplus that results from that price is denoted CS. Consumer surplus is the amount a buyer is willing to pay for a good minus the amount the buyer actually pays for it. It measures the benefit to buyers ofparticipating in a market.Figure 1 Figure 22. Figure 2 shows the supply curve for turkey. The price of turkey is P 1and the producer surplus that results from that price is denoted PS. Producer surplus is the amount sellers are paid for a good minus the sellers’ cost of providing it (measured by the supply curve). It measures the benefit to sellers of participating in a market.It would be a good idea to remind students that there are circumstances when the market process does not lead to the most efficient outcome. Examples include situations such as when a firm (or buyer) has market power over price or when there areFigure 33. Figure 3 shows the supply and demand for turkey. The price of turkey is P, consumer surplus is CS, and producer surplus is PS. Producing more turkeys 1than the equilibrium quantity would lower total surplus because the value to the marginal buyer would be lower than the cost to the marginal seller on those additional units.Questions for Review1. The price a buyer is willing to pay, consumer surplus, and the demand curve are all closely related. The height of the demand curve represents the willingness to pay of the buyers. Consumer surplus is the area below the demand curve and above the price, which equals the price that each buyer is willing to pay minus the price actually paid.2. Sellers' costs, producer surplus, and the supply curve are all closely related. The height of the supply curve represents the costs of the sellers. Producer surplus is the area below the price and above the supply curve, which equals the price received minus each seller's costs of producing the good.Figure 43. Figure 4 shows producer and consumer surplus in a supply-and-demand diagram.4. An allocation of resources is efficient if it maximizes total surplus, the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus. But efficiency may not be the only goal of economic policymakers; they may also be concerned about equitythe fairness of the distribution of well-being.5. The invisible hand of the marketplace guides the self-interest of buyers and sellers into promoting general economic well-being. Despite decentralized decision making and self-interested decision makers, free markets often lead to an efficient outcome.6. Two types of market failure are market power and externalities. Market power may cause market outcomes to be inefficient because firms may cause price and quantity to differ from the levels they would be under perfect competition, which keeps total surplus from being maximized. Externalities are side effects that are not taken into account by buyers and sellers. As a result, the free market does not maximize total surplus.Problems and Applications1. a. Consumer surplus is equal to willingness to pay minus the price paid. Therefore, Melissa’s willingness to pay must be $200 ($120 + $80).b. Her consumer surplus at a price of $90 would be $200 $90 = $110.c. If the price of an iPod was $250, Melissa would not have purchased one because the price is greater than her willingness to pay. Therefore, she would receive no consumer surplus.2. If an early freeze in California sours the lemon crop, the supply curve for lemons shifts to the left, as shown in Figure 5. The result is a rise in the price of lemons and a decline in consumer surplus from A + B + C to just A. So consumer surplus declines by the amount B + C.Figure 5 Figure 6In the market for lemonade, the higher cost of lemons reduces the supply of lemonade, as shown in Figure 6. The result is a rise in the price of lemonade and a decline in consumer surplus from D + E + F to just D, a loss of E + F. Note that an event that affects consumer surplus in one market oftenhas effects on consumer surplus in other markets.3. A rise in the demand for French bread leads to an increase in producer surplus in the market for French bread, as shown in Figure 7. The shift of the demand curve leads to an increased price, which increases producer surplusfrom area A to area A + B + C.Figure 7The increased quantity of French bread being sold increases the demandfor flour, as shown in Figure 8. As a result, the price of flour rises, increasing producer surplus from area D to D + E + F. Note that an event that affects producer surplus in one market leads to effects on producer surplus in related markets.Figure 84. a.Figure 9b. When the price of a bottle of water is $4, Bert buys two bottles of water. His consumer surplus is shown as area A in the figure. He values hisfirst bottle of water at $7, but pays only $4 for it, so has consumer surplus of $3. He values his second bottle of water at $5, but pays only $4 for it, so has consumer surplus of $1. Thus Bert’s total consumer surplus is $3 + $1 = $4, which is the area of A in the figure.c. When the price of a bottle of water falls from $4 to $2, Bert buys three bottles of water, an increase of one. His consumer surplus consists of both areas A and B in the figure, an increase in the amount of area B. He gets consumer surplus of $5 from the first bottle ($7 value minus $2 price), $3from the second bottle ($5 value minus $2 price), and $1 from the third bottle ($3 value minus $2 price), for a total consumer surplus of $9. Thus consumer surplus rises by $5 (which is the size of area B) when the price of a bottle of water falls from $4 to $2.5. a.Figure 10b. When the price of a bottle of water is $4, Ernie sells two bottles of water. His producer surplus is shown as area A in the figure. He receives $4 for his first bottle of water, but it costs only $1 to produce, so Ernie has producer surplus of $3. He also receives $4 for his second bottle of water, which costs $3 to produce, so he has producer surplus of $1. Thus Ernie’s total producer surplus is $3 + $1 = $4, which is the area of A in the figure.c. When the price of a bottle of water rises from $4 to $6, Ernie sells three bottles of water, an increase of one. His producer surplus consists of both areas A and B in the figure, an increase by the amount of area B. He gets producer surplus of $5 from the first bottle ($6 price minus $1 cost), $3 from the second bottle ($6 price minus $3 cost), and $1 from the third bottle ($6 price minus $5 price), for a total producer surplus of $9. Thus producer surplus rises by $5 (which is the size of area B) when the price of a bottle of water rises from $4 to $6.6. a. From Ernie’s supply schedule and Bert’s demand schedule, thean equilibrium quantity of two.b. At a price of $4, consumer surplus is $4 and producer surplus is $4, as shown in Problems 3 and 4 above. Total surplus is $4 + $4 = $8.c. If Ernie produced one less bottle, his producer surplus would decline to $3, as shown in Problem 4 above. If Bert consumed one less bottle, hisconsumer surplus would decline to $3, as shown in Problem 3 above. So total surplus would decline to $3 + $3 = $6.d. If Ernie produced one additional bottle of water, his cost would be $5, but the price is only $4, so his producer surplus would decline by $1. If Bert consumed one additional bottle of water, his value would be $3, but the price is $4, so his consumer surplus would decline by $1. So total surplus declines by $1 + $1 = $2.7. a. The effect of falling production costs in the market for stereos results in a shift to the right in the supply curve, as shown in Figure 11. As a result, the equilibrium price of stereos declines and the equilibriumquantity increases.Figure 11b. The decline in the price of stereos increases consumer surplus from area A to A + B + C + D, an increase in the amount B + C + D. Prior to the shift in supply, producer surplus was areas B + E (the area above the supply curve and below the price). After the shift in supply, producer surplus is areas E + F + G. So producer surplus changes by the amount F + G – B, which may be positive or negative. The increase in quantity increases producer surplus, while the decline in the price reduces producer surplus. Because consumer surplus rises by B + C + D and producer surplus rises by F + G – B, total surplus rises by C + D + F + G.c. If the supply of stereos is very elastic, then the shift of the supply curve benefits consumers most. To take the most dramatic case, suppose the supply curve were horizontal, as shown in Figure 12. Then there is no producer surplus at all. Consumers capture all the benefits of falling production costs, with consumer surplus rising from area A to area A + B.Figure 128. Figure 13 shows supply and demand curves for haircuts. Supply equals demand at a quantity of three haircuts and a price between $4 and $5. Firms A, C, and D should cut the hair of Ellen, Jerry, and Phil. Oprah’s willingnessto pay is too low and firm B’s costs are too high, so they do not participate. The maximum total surplus is the area between the demand and supply curves, which totals $11 ($8 value minus $2 cost for the first haircut, plus $7 value minus $3 cost for the second, plus $5 value minus $4 cost for the third).Figure 139. a. The effect of falling production costs in the market for computers results in a shift to the right in the supply curve, as shown in Figure 14. As a result, the equilibrium price of computers declines and the equilibrium quantity increases. The decline in the price of computers increases consumer surplus from area A to A + B + C + D, an increase in the amount B + C + D.Figure 14 Figure 15Prior to the shift in supply, producer surplus was areas B + E(the area above the supply curve and below the price). After theshift in supply, producer surplus is areas E + F + G. So producersurplus changes by the amount F + G – B, which may be positive ornegative. The increase in quantity increases producer surplus,while the decline in the price reduces producer surplus. Becauseconsumer surplus rises by B + C + D and producer surplus rises byF +G – B, total surplus rises by C + D + F + G.b. Because typewriters are substitutes for computers, the decline in the price of computers means that people substitute computers for typewriters, shifting the demand for typewriters to the left, as shown in Figure 15. The result is a decline in both the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity of typewriters. Consumer surplus in the typewriter market changes from area A + B to A + C, a net change of C – B. Producer surplus changes from area C + D + E to area E, a net loss of C + D. Typewriter producers are sad about technological advances in computers because their producer surplus declines.c. Because software and computers are complements, the decline in the price and increase in the quantity of computers means that the demand for software increases, shifting the demand for software to the right, as shown in Figure 16. The result is an increase in both the price and quantity of software. Consumer surplus in the software market changes from B + C to A + B, a net change of A – C. Producer surplus changes from E to C + D + E, an increase of C + D, so software producers should be happy about the technological progress in computers.Figure 16d. Yes, this analysis helps explain why Bill Gates is one the world’s richest people, because his company produces a lot of software that is a complement with computers and there has been tremendous technological advance in computers.10. a. With Provider A, the cost of an extra minute is $0. WithProvider B, the cost of an extra minute is $1.b. With Provider A, my friend will purchase 150 minutes [= 150 –(50)(0)]. With Provider B, my friend would purchase 100 minutes [=150 – (50)(1)].c. With Provider A, he would pay $120. The cost would be $100 with Provider B.Figure 17d. Figure 17 shows the friend’s demand. With Provider A, he buys 150minutes and his consumer surplus is equal to (1/2)(3)(150) – 120= 105. With Provider B, his consumer surplus is equal to(1/2)(2)(100) = 100.e. I would recommend Provider A because he receives greater consumer surplus.11. a. Figure 18 illustrates the demand for medical care. If each procedure has a price of $100, quantity demanded will be Q1 procedures.Figure 18b. If consumers pay only $20 per procedure, the quantity demanded will be Qprocedures. Because the cost to society is $100, the number of procedures 2performed is too large to maximize total surplus. The quantity that maximizes total surplus is Q1 procedures, which is less than Q2.c. The use of medical care is excessive in the sense that consumers get procedures whose value is less than the cost of producing them. As a result, the economy’s total surplus is reduced.d. To prevent this excessive use, the consumer must bear the marginal cost of the procedure. But this would require eliminating insurance. Another possibility would be that the insurance company, which pays most of the marginal cost of the procedure ($80, in this case) could decide whether the procedure should be performed. But the insurance company does not get the benefits of the procedure, so its decisions may not reflect the value to the consumer.。

Answers to Textbook Questions and ProblemsCHAPTER 3 National Income: Where It Comes From and Where It GoesQuestions for Review1. The factors of production and the production technologydetermine the amount of output an economy can produce. The factors of production are the inputs used to produce goods and services: the most important factors are capital and labor. The production technology determines how much output can be produced from any given amounts of these inputs. An increase in one of the factors of production or an improvement in technology leads to an increase in the economy’s output.2. When a firm decides how much of a factor of production tohire or demand, it considers how this decision affects profits. For example, hiring an extra unit of labor increases output and therefore increases revenue; the firm compares this additional revenue to the additional cost from the higher wage bill. The additional revenue the firm receives depends on the marginal product of labor (MPL) and the price of the good produced (P). An additional unit of labor produces MPL units of additional output, which sells for P dollars per unit. Therefore, the additional revenue to the firm is P MPL. The cost of hiring the additional unit of labor is the wage W. Thus, this hiring decision hasthe following effect on profits:ΔProfit= ΔRevenue –ΔCost= (P MPL) –W.If the additional revenue, P MPL, exceeds the cost (W) of hiring the additional unit of labor, then profit increases. The firm will hire labor until it is no longer profitable to do so—that is, until the MPL falls to the point where the change in profit is zero. In the equation abov e, the firm hires labor until ΔP rofit = 0, which is when (P MPL) = W.This condition can be rewritten as:MPL = W/P.Therefore, a competitive profit-maximizing firm hires labor until the marginal product of labor equals the real wage.The same logic applies to the firm’s decision regarding how much capital to hire: the firm will hire capital until the marginal product of capital equals the real rental price.3. A production function has constant returns to scale if anequal percentage increase in all factors of production causes an increase in output of the same percentage. For example, if a firm increases its use of capital and labor by 50 percent, and output increases by 50 percent, then the production function has constant returns to scale.If the production function has constant returns to scale,then total income (or equivalently, total output) in an economy of competitive profit-maximizing firms is divided between the return to labor, MPL L, and the return to capital, MPK K. That is, under constant returns to scale, economic profit is zero.4. A Cobb–Douglas production function has the form F(K,L) =AKαL1–α. The text showed that the parameter αgives capital’s share of income. So if capital earns one-fourth of total income, then = . Hence, F(K,L) = Consumption depends positively on disposable income—.the amount of income after all taxes have been paid. Higher disposable income means higher consumption.The quantity of investment goods demanded depends negatively on the real interest rate. For an investment to be profitable, its return must be greater than its cost.Because the real interest rate measures the cost of funds,a higher real interest rate makes it more costly to invest,so the demand for investment goods falls.6. Government purchases are a measure of the value of goodsand services purchased directly by the government. For example, the government buys missiles and tanks, builds roads, and provides services such as air traffic control.All of these activities are part of GDP. Transfer payments are government payments to individuals that are not in exchange for goods or services. They are the opposite of taxes: taxes reduce household disposable income, whereas transfer payments increase it. Examples of transfer payments include Social Security payments to the elderly, unemployment insurance, and veterans’ benefits.7. Consumption, investment, and government purchases determinedemand for the economy’s output, whereas the factors of production and the production function determine the supply of output. The real interest rate adjusts to ensure that the demand for the economy’s goods equals th e supply. At the equilibrium interest rate, the demand for goods and services equals the supply.8. When the government increases taxes, disposable incomefalls, and therefore consumption falls as well. The decrease in consumption equals the amount that taxes increase multiplied by the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). The higher the MPC is, the greater is the negative effect of the tax increase on consumption. Because output is fixed by the factors of production and the production technology, and government purchases have not changed, the decrease in consumption must be offset by an increase in investment. For investment to rise, the real interest rate must fall. Therefore, a tax increase leads to a decrease in consumption, an increase in investment, and a fall in the real interest rate.Problems and Applications1. a. According to the neoclassical theory of distribution,the real wage equals the marginal product of labor.Because of diminishing returns to labor, an increase in the labor force causes the marginal product of labor to fall. Hence, the real wage falls.Given a Cobb–Douglas production function, theincrease in the labor force will increase the marginal product of capital and will increase the real rental price of capital. With more workers, the capital will be used more intensively and will be more productive.b. The real rental price equals the marginal product ofcapital. If an earthquake destroys some of the capital stock (yet miraculously does not kill anyone and lower the labor force), the marginal product of capital rises and, hence, the real rental price rises.Given a Cobb–Douglas production function, the decrease in the capital stock will decrease the marginal product of labor and will decrease the real wage. With less capital, each worker becomes less productive.c. If a technological advance improves the productionfunction, this is likely to increase the marginal products of both capital and labor. Hence, the real wage and the real rental price both increase.d. High inflation that doubles the nominal wage and theprice level will have no impact on the real wage.Similarly, high inflation that doubles the nominal rental price of capital and the price level will have no impact on the real rental price of capital.2. a. To find the amount of output produced, substitute thegiven values for labor and land into the production function:Y = = 100.b. According to the text, the formulas for the marginalproduct of labor and the marginal product of capital (land) are:MPL = (1 –α)AKαL–α.MPK = αAKα–1L1–α.In this problem, αis and A is 1. Substitute in the given values for labor and land to find the marginal product of labor is and marginal product of capital (land) is . We know that the real wage equals the marginal product of labor and the real rental price of land equals the marginal product of capital (land).c. Labor’s share of the output is given by the marginalproduct of labor times the quantity of labor, or 50.d. The new level of output is .e. The new wage is . The new rental price of land is .f. Labor now receives .3. A production function has decreasing returns to scale if anequal percentage increase in all factors of production leads to a smaller percentage increase in output. For example, if we double the amounts of capital and labor output increases by less than double, then the production function has decreasing returns to scale. This may happen if there is a fixed factor such as land in the production function, and this fixed factor becomes scarce as the economy grows larger.A production function has increasing returns to scale ifan equal percentage increase in all factors of production leads to a larger percentage increase in output. For example, if doubling the amount of capital and labor increases the output by more than double, then the production function has increasing returns to scale. This may happen if specialization of labor becomes greater as the population grows. For example, if only one worker builds a car, then it takes him a long time because he has to learn many different skills, and he must constantly change tasks and tools. But if many workers build a car, then each one can specialize in a particular task and become more productive.4. a. A Cobb–Douglas production function has the form Y =AKαL1–α. The text showed that the marginal products for the Cobb–Douglas production function are:MPL = (1 –α)Y/L.MPK = αY/K.Competitive profit-maximizing firms hire labor until its marginal product equals the real wage, and hire capital until its marginal product equals the real rental rate. Using these facts and the above marginal products for the Cobb–Douglas production function, we find:W/P = MPL = (1 –α)Y/L.R/P = MPK = αY/K.Rewriting this:(W/P)L = MPL L = (1 –α)Y.(R/P)K = MPK K = αY.Note that the terms (W/P)L and (R/P)K are the wage bill and total return to capital, respectively. Given that the value of α= , then the above formulas indicate that labor receives 70 percent of total output (or income) and capital receives 30 percent of total output (or income).b. To determine what happens to total output when the laborforce increases by 10 percent, consider the formula for the Cobb–Douglas production function:Y = AKαL1–α.Let Y1equal the initial value of output and Y2equal final output. We know that α = . We also know that labor L increases by 10 percent:Y1 = Y2 = .Note that we multiplied L by to reflect the 10-percent increase in the labor force.To calculate the percentage change in output, divide Y2 by Y1:Y 2 Y 1=AK0.31.1L()0.7AK0.3L0.7 =1.1()0.7=1.069.That is, output increases by percent.To determine how the increase in the labor force affects the rental price of capital, consider the formula for the real rental price of capital R/P:R/P = MPK = αAKα–1L1–α.We know that α= . We also know that labor (L) increases by 10 percent. Let (R/P)1equal the initial value of the rental price of capital, and let (R/P)2 equal the final rental price of capital after the laborforce increases by 10 percent. To find (R/P )2, multiply Lby to reflect the 10-percent increase in the labor force:(R/P )1 = – (R/P )2 = –.The rental price increases by the ratioR /P ()2R /P ()1=0.3AK -0.71.1L ()0.70.3AK -0.7L 0.7=1.1()0.7=1.069So the rental price increases by percent. To determine how the increase in the labor forceaffects the real wage, consider the formula for the real wage W/P :W/P = MPL = (1 – α)AK αL –α.We know that α = . We also know that labor (L )increases by 10 percent. Let (W/P )1 equal the initialvalue of the real wage, and let (W/P )2 equal the finalvalue of the real wage. To find (W/P )2, multiply L by toreflect the 10-percent increase in the labor force:(W/P )1 = (1 – –.(W/P )2 = (1 – –.To calculate the percentage change in the real wage, divide (W/P )2 by (W/P )1:W /P ()2W /P ()1=1-0.3()AK 0.31.1L ()-0.31-0.3()AK 0.3L -0.3=1.1()-0.3=0.972That is, the real wage falls by percent.c. We can use the same logic as in part (b) to setY 1 = Y 2 = A Therefore, we have:Y 2Y 1=A 1.1K ()0.3L 0.7AK 0.3L 0.7=1.1()0.3=1.029This equation shows that output increases by about 3percent. Notice that α < means that proportional increases to capital will increase output by less than the same proportional increase to labor.Again using the same logic as in part (b) for thechange in the real rental price of capital:R /P ()2R /P ()1=0.3A 1.1K ()-0.7L 0.70.3AK -0.7L 0.7=1.1()-0.7=0.935The real rental price of capital falls by percentbecause there are diminishing returns to capital; that is, when capital increases, its marginal product falls. Finally, the change in the real wage is:W /P ()2W /P ()1=0.7A 1.1K ()0.3L -0.30.7AK 0.3L -0.3=1.1()0.3=1.029Hence, real wages increase by percent because the addedcapital increases the marginal productivity of the existing workers. (Notice that the wage and output have both increased by the same amount, leaving the labor share unchanged —a feature of Cobb –Douglas technologies.)d. Using the same formula, we find that the change in output is:Y 2Y 1= 1.1A ()K 0.3L 0.7AK 0.3L 0.7=1.1This equation shows that output increases by 10 percent.Similarly, the rental price of capital and the real wage also increase by 10 percent:R /P ()2R /P ()1=0.31.1A ()K -0.7L 0.70.3AK -0.7L 0.7=1.1W /P ()2W /P ()1=0.71.1A ()K 0.3L -0.30.7AK 0.3L -0.3=1.15. Labor income is defined asW P ´L =WL P Labor’s share of income is defined asWL P æèççöø÷÷/Y =WL PY For example, if this ratio is about constant at a value of ,then the value of W /P = *Y /L . This means that the real wage is roughly proportional to labor productivity. Hence, any trend in labor productivity must be matched by an equal trend in real wages. O therwise, labor’s share would deviate from . Thus, the first fact (a constant labor share) implies the second fact (the trend in real wages closely tracks the trend in labor productivity).6. a. Nominal wages are measured as dollars per hour worked.Prices are measured as dollars per unit produced (either a haircut or a unit of farm output). Marginal productivity is measured as units of output produced per hour worked.b. According to the neoclassical theory, technicalprogress that increases the marginal product of farmers causes their real wage to rise. The real wage for farmers is measured as units of farm output per hour worked. The real wage is W/P F, and this is equal to ($/hour worked)/($/unit of farm output).c. If the marginal productivity of barbers is unchanged,then their real wage is unchanged. The real wage for barbers is measured as haircuts per hour worked. The real wage is W/P B, and this is equal to ($/hour worked)/($/haircut).d. If workers can move freely between being farmers andbeing barbers, then they must be paid the same wage W in each sector.e. If the nominal wage W is the same in both sectors, butthe real wage in terms of farm goods is greater than the real wage in terms of haircuts, then the price of haircuts must have risen relative to the price of farm goods. We know that W/P = MPL so that W = P MPL. This means that P F MPL F= P H MPL B, given that the nominal wages are the same. Since the marginal product of labor for barbers has not changed and the marginal product of labor for farmers has risen, the price of a haircut must have risen relative to the price of the farm output. If we express this in growth rate terms, then the growth of the farm price + the growth of the marginal product of the farm labor = the growth of the haircut price.f. The farmers and the barbers are equally well off after the technological progress in farming, giventhe assumption that labor is freely mobile between the two sectors and both types of people consume the same basket of goods. Given that the nominal wage ends up equal for each type of worker and that they pay the same prices for final goods, they are equally well off in terms of what they can buy with their nominal income.The real wage is a measure of how many units of output are produced per worker. Technological progress in farming increased the units of farm output produced per hour worked. Movement of labor between sectors then equalized the nominal wage.7. a. The marginal product of labor (MPL)is found bydifferentiating the production function with respect to labor:MPL=dY dL=11/3H1/3L-2/3An increase in human capital will increase the marginal product of labor because more human capital makes all the existing labor more productive.b. The marginal product of human capital (MPH)is found bydifferentiating the production function with respect to human capital:MPH=dY dH=13K1/3L1/3H-2/3An increase in human capital will decrease the marginal product of human capital because there are diminishing returns.c. The labor share of output is the proportion of outputthat goes to labor. The total amount of output that goes to labor is the real wage (which, under perfect competition, equals the marginal product of labor) times the quantity of labor. This quantity is divided by the total amount of output to compute the labor share:Labor Share=(13K1/3H1/3L-2/3)LK1/3H1/3L1/3=1 3We can use the same logic to find the human capital share:Human Capital Share=(13K1/3L1/3H-2/3)HK1/3H1/3L1/3=1 3so labor gets one-third of the output, and human capital gets one-third of the output. Since workers own their human capital (we hope!), it will appear that labor gets two-thirds of output.d. The ratio of the skilled wage to the unskilled wage is:Wskilled Wunskilled =MPL+MPHMPL=13K1/3L-2/3H1/3+13K1/3L1/3H-2/313K1/3L-2/3H1/3=1+LHNotice that the ratio is always greater than 1 because skilled workers get paid more than unskilled workers.Also, when H increases this ratio falls because the diminishing returns to human capital lower its return, while at the same time increasing the marginal product of unskilled workers.e. If more colleges provide scholarships, it will increaseH, and it does lead to a more egalitarian society. The policy lowers the returns to education, decreasing the gap between the wages of more and less educated workers.More importantly, the policy even raises the absolute wage of unskilled workers because their marginal product rises when the number of skilled workers rises.8. The effect of a government tax increase of $100 billion on(a) public saving, (b) private saving, and (c) nationalsaving can be analyzed by using the following relationships:National Saving = [Private Saving] + [Public Saving]= [Y –T –C(Y –T)] + [T –G]= Y –C(Y –T) –G.a. Public Saving—The tax increase causes a 1-for-1increase in public saving. T increases by $100 billion and, therefore, public saving increases by $100 billion.b. Private Saving—The increase in taxes decreasesdisposable income, Y –T, by $100 billion. Since the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is , consumption falls by $100 billion, or $60 billion. Hence,ΔPrivate Saving = –$100b – (–$100b) = –$40b.Private saving falls $40 billion.c. National Saving—Because national saving is the sum ofprivate and public saving, we can conclude that the $100 billion tax increase leads to a $60 billion increase in national saving.Another way to see this is by using the third equation for national saving expressed above, that national saving equals Y –C(Y –T) –G. The $100 billion tax increase reduces disposable income and causes consumption to fall by $60 billion. Since neither G nor Y changes, national saving thus rises by $60 billion.d. Investment—To determine the effect of the tax increaseon investment, recall the national accounts identity:Y = C(Y –T) + I(r) + G.Rearranging, we findY –C(Y –T) –G = I(r).The left side of this equation is national saving, so the equation just says that national saving equals investment. Since national saving increases by $60 billion, investment must also increase by $60 billion.How does this increase in investment take place We know that investment depends on the real interest rate.For investment to rise, the real interest rate must fall.Figure 3-1 illustrates saving and investment as a function of the real interest rate.The tax increase causes national saving to rise, so the supply curve for loanable funds shifts to the right.The equilibrium real interest rate falls, and investment rises.9. If consumers increase the amount that they consume today,then private saving and, therefore, national saving will fall. We know this from the definition of national saving:National Saving = [Private Saving] + [Public Saving]= [Y –T –C(Y –T)] + [T –G].An increase in consumption decreases private saving, so national saving falls.Figure 3-2 illustrates saving and investment as a function of the real interest rate. If national saving decreases, the supply curve for loanable funds shifts tothe left, thereby raising the real interest rate and reducing investment.10. a. Private saving is the amount of disposable income, Y – T, that is not consumed:S private= Y – T – C= 8,000 –2,000 –[1,000 + (2/3)(8,000 – 2,000)]= 1,000.Public saving is the amount of taxes the government has left over after it makes its purchases:S public = T – G= 2,000 – 2,500= –500.National saving is the sum of private saving and public saving:S national=S private+ S public= 1,000 + (500)= 500.b. The equilibrium interest rate is the value of r thatclears the market for loanable funds. We already know that national saving is 500, so we just need to set it equal to investment:S national=I500 = 1,200 – 100rSolving this equation for r, we find:r = or 7%.c. When the government increases its spending, privatesaving remains the same as before (notice that G does not appear in the S private equation above) while government saving decreases. Putting the new G into the equations above:S private= 1,000S public = T – G= 2,000 – 2,000= 0.Thus,S national=S private+ S public= 1,000 + (0)= 1,000.d. Once again the equilibrium interest rate clears the market for loanable funds:S national=I1,000 = 1,200 – 100rSolving this equation for r, we find:r = or 2%.11. To determine the effect on investment of an equalincrease in both taxes and government spending, consider the national income accounts identity for national saving:National Saving = [Private Saving] + [Public Saving]= [Y –T –C(Y –T)] + [T –G].We know that Y is fixed by the factors of production. We also know that the change in consumption equals the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) times the change in disposable income. This tells us thatΔNational Saving= {–ΔT –[MPC (–ΔT)]} + [ΔT –ΔG]= [–ΔT + (MPC ΔT)] + 0= (MPC –1) ΔT.The above expression tells us that the impact on national saving of an equal increase in T and G depends on the size of the marginal propensity to consume. The closer the MPC is to 1, the smaller is the fall in saving. For example, if the MPC equals 1, then the fall in consumption equals the rise in government purchases, so national saving [Y –C(Y –T) –G] is unchanged. The closer the MPC is to 0 (and therefore the larger is the amount saved rather than spent for a one-dollar change in disposable income), the greater is the impact on saving. Because we assume that the MPC is less than 1, we expect that national savingfalls in response to an equal increase in taxes and government spending.The reduction in saving means that the supply of loanable funds curve will shift to the left in Figure 3-3.The real interest rate rises, and investment falls.12. a. The demand curve for business investment shifts outto the right because the subsidy increases the number of profitable investment opportunities for any given interest rate. The demand curve for residential investment remains unchanged.b. The total demand curve for investment in the economyshifts out to the right since it represents the sum of business investment, which shifts out to the right, and residential investment, which is unchanged. As a result the real interest rate rises as in Figure 3-4.c. The total quantity of investment does not change becauseit is constrained by the inelastic supply of savings. The investment tax credit leads to a rise in business investment, but an offsetting fall in residential investment. That is, the higher interest rate means that residential investment falls (a movement along the curve), whereas the rightward shift of the business investment curve leads business investment to rise by an equal amount. Figure 3-5 shows this change. Note thatI 1B +I 1R +I 2B +I 2R =S .13. In this chapter, we concluded that an increase ingovernment expenditures reduces national saving and raises the interest rate. The increase in government expenditure therefore crowds out investment by the full amount of the increase. Similarly, a tax cut increases disposable income and hence consumption. This increase in consumptiontranslates into a fall in national saving, and the increase in consumption crowds out investment by the full amount of the increase.If consumption depends on the interest rate, then saving will also depend on it. The higher the interest rate, the greater the return to saving. Hence, it seems reasonable to think that an increase in the interest rate might increase saving and reduce consumption. Figure 3-6 shows saving as an increasing function of the interest rate.Consider what happens when government purchases increase. At any given level of the interest rate, national saving falls by the change in government purchases, as shown in Figure 3-7. The figure shows that if the saving function slopes upward, investment falls by less than the amount that government purchases rises by. This happens because consumption falls and saving increases in response to the higher interest rate. Hence, the more responsive consumption is to the interest rate, the less investment is crowded out by government purchases.14. a. Figure 3-8 shows the case where the demand forloanable funds is stable but the supply of funds (the saving schedule) fluctuates perhaps reflecting temporary shocks to income, changes in government spending, or changes in consumer confidence. In this case, when interest rates fall, investment rises; when interest rates rise, investment falls. We would expect a negative correlation between investment and interest rates.b. Figure 3-9 shows the case where the supply of loanablefunds (saving) is stable, whereas the demand for loanable funds fluctuates, perhaps reflecting changes in firms’ expectations about the marginal product of capital. We would now find a positive correlation between investment and the interest rate—when demand for funds rises, it pushes up the interest rate, so weobserve that investment and the real interest rate increase at the same time.c. If both curves shift, we might generate a scatter plotas in Figure 3-10, where the economy fluctuates among points A, B, C, and D. Depending on how often the economy is at each of these points, we might find little clear relationship between investment and interest rates.d. Situation (c) seems fairly reasonable—as both thesupply of and demand for loanable funds fluctuate over time in response to changes in the economy.。

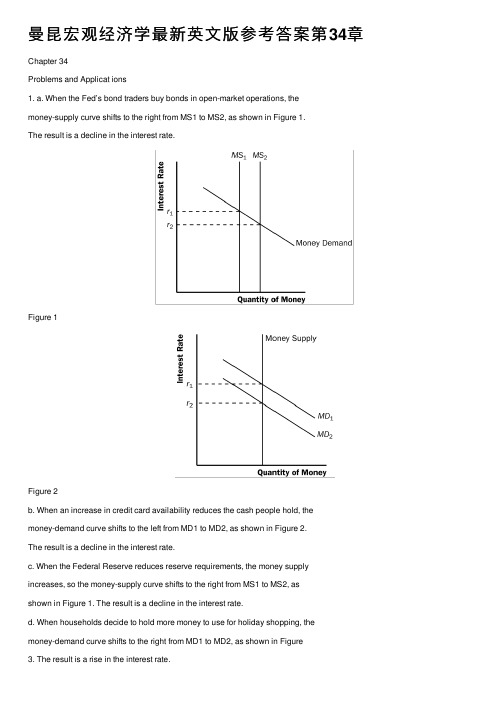

A n s w e r s t o T e x t b o o k Q u e s t i o n s a n d P r o b l e m s CHAPTER 7?Unemployment and the Labor MarketQuestions for Review1. The rates of job separation and job finding determine the natural rate of unemployment. The rate of jobseparation is the fraction of people who lose their job each month. The higher the rate of job separation, the higher the natural rate of unemployment. The rate of job finding is the fraction of unemployed people who find a job each month. The higher the rate of job finding, the lower the natural rate ofunemployment.2. Frictional unemployment is the unemployment caused by the time it takes to match workers and jobs.Finding an appropriate job takes time because the flow of information about job candidates and job vacancies is not instantaneous. Because different jobs require different skills and pay different wages, unemployed workers may not accept the first job offer they receive.In contrast, structural unemployment is the unemployment resulting from wage rigidity and job rationing. These workers are unemployed not because they are actively searching for a job that best suits their skills (as in the case of frictional unemployment), but because at the prevailing real wage the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity of labor demanded. If the wage does not adjust to clear the labor market, then these workers must wait for jobs to become available. Structural unemployment thus arises because firms fail to reduce wages despite an excess supply of labor.3. The real wage may remain above the level that equilibrates labor supply and labor demand because ofminimum wage laws, the monopoly power of unions, and efficiency wages.Minimum-wage laws cause wage rigidity when they prevent wages from falling to equilibrium levels. Although most workers are paid a wage above the minimum level, for some workers, especially the unskilled and inexperienced, the minimum wage raises their wage above the equilibrium level. It therefore reduces the quantity of their labor that firms demand, and creates an excess supply ofworkers, which increases unemployment.The monopoly power of unions causes wage rigidity because the wages of unionized workers are determined not by the equilibrium of supply and demand but by collective bargaining between union leaders and firm management. The wage agreement often raises the wage above the equilibrium level and allows the firm to decide how many workers to employ. These high wages cause firms to hire fewer workers than at the market-clearing wage, so structural unemployment increases.Efficiency-wage theories suggest that high wages make workers more productive. The influence of wages on worker efficiency may explain why firms do not cut wages despite an excess supply of labor. Even though a wage reduction decreases th e firm’s wage bill, it may also lower workerproductivity and therefore the firm’s profits.4. Depending on how one looks at the data, most unemployment can appear to be either short term orlong term. Most spells of unemployment are short; that is, most of those who became unemployed find jobs quickly. On the other hand, most weeks of unemployment are attributable to the small number of long-term unemployed. By definition, the long-term unemployed do not find jobs quickly, so they appear on unemployment rolls for many weeks or months.5. Europeans work fewer hours than Americans. One explanation is that the higher income tax rates inEurope reduce the incentive to work. A second explanation is a larger underground economy in Europe as a result of more people attempting to evade the high tax rates. A third explanation is the greater importance of unions in Europe and their ability to bargain for reduced work hours. A final explanation is based on preferences, whereby Europeans value leisure more than Americans do, and therefore elect to work fewer hours.Problems and Applications1. a. In the example that follows, we assume that during the school year you look for a part-time job,and that, on average, it takes 2 weeks to find one. We also assume that the typical job lasts 1semester, or 12 weeks.b. If it takes 2 weeks to find a job, then the rate of job finding in weeks isf = (1 job/2 weeks) = 0.5 jobs/week.If the job lasts for 12 weeks, then the rate of job separation in weeks iss = (1 job/12 weeks) = 0.083 jobs/week.c. From the text, we know that the formula for the natural rate of unemployment is(U/L) = [s/(s + f )],where U is the number of people unemployed, and L is the number of people in the labor force.Plugging in the values for f and s that were calculated in part (b), we find(U/L) = [0.083/(0.083 + 0.5)] = 0.14.Thus, if on average it takes 2 weeks to find a job that lasts 12 weeks, the natural rate ofunemployment for this population of college students seeking part-time employment is 14 percent.2. Call the number of residents of the dorm who are involved I, the number who are uninvolved U, and thetotal number of students T = I + U. In steady state the total number of involved students is constant.For this to happen we need the number of newly uninvolved students, (0.10)I, to be equal to thenumber of students who just became involved, (0.05)U. Following a few substitutions:(0.05)U = (0.10)I= (0.10)(T – U),soWe find that two-thirds of the students are uninvolved.3. To show that the unemployment rate evolves over time to the steady-state rate, let’s begin by defininghow the number of people unemployed changes over time. The change in the number of unemployed equals the number of people losing jobs (sE) minus the number finding jobs (fU). In equation form, we can express this as:U t + 1–U t= ΔU t + 1 = sE t–fU t.Recall from the text that L = E t + U t, or E t = L –U t, where L is the total labor force (we will assume that L is constant). Substituting for E t in the above equation, we findΔU t + 1 = s(L –U t) –fU t.Dividing by L, we get an expression for the change in the unemployment rate from t to t + 1:ΔU t + 1/L = (U t + 1/L) – (U t/L) = Δ[U/L]t + 1 = s(1 –U t/L) –fU t/L.Rearranging terms on the right side of the equation above, we end up with line 1 below. Now take line1 below, multiply the right side by (s + f)/(s + f) and rearrange terms to end up with line2 below:Δ[U/L]t + 1= s – (s + f)U t/L= (s + f)[s/(s + f) – U t/L].The first point to note about this equation is that in steady state, when the unemployment rate equals its natural rate, the left-hand side of this expression equals zero. This tells us that, as we found in the text, the natural rate of unemployment (U/L)n equals s/(s + f). We can now rewrite the above expression, substituting (U/L)n for s/(s + f), to get an equation that is easier to interpret:Δ[U/L]t + 1 = (s + f)[(U/L)n–U t/L].This expression shows the following:? If U t/L > (U/L)n (that is, the unemployment rate is above its natural rate), then Δ[U/L]t + 1 is negative: the unemployment rate falls.? If U t/L < (U/L)n (that is, the unemployment rate is below its natural rate), then Δ[U/L]t + 1 is positive: the unemployment rate rises.This process continues until the unemployment rate U/L reaches the steady-state rate (U/L)n.4. Consider the formula for the natural rate of unemployment,If the new law lowers the chance of separation s, but has no effect on the rate of job finding f, then the natural rate of unemployment falls.For several reasons, however, the new law might tend to reduce f. First, raising the cost of firing might make firms more careful about hiring workers, since firms have a harder time firing workers who turn out to be a poor match. Second, if job searchers think that the new legislation will lead them to spend a longer period of time on a particular job, then they might weigh more carefully whether or not to take that job. If the reduction in f is large enough, then the new policy may even increase the natural rate of unemployment.5. a. The demand for labor is determined by the amount of labor that a profit-maximizing firm wants tohire at a given real wage. The profit-maximizing condition is that the firm hire labor until themarginal product of labor equals the real wage,The marginal product of labor is found by differentiating the production function with respect tolabor (see Chapter 3 for more discussion),In order to solve for labor demand, we set the MPL equal to the real wage and solve for L:Notice that this expression has the intuitively desirable feature that increases in the real wagereduce the demand for labor.b. We assume that the 27,000 units of capital and the 1,000 units of labor are supplied inelastically (i.e., they will work at any price). In this case we know that all 1,000 units of labor and 27,000 units of capital will be used in equilibrium, so we can substitute these values into the above labor demand function and solve for W P .In equilibrium, employment will be 1,000, and multiplying this by 10 we find that the workers earn 10,000 units of output. The total output is given by the production function: Y =5K 13L 23Y =5(27,00013)(1,00023)Y =15,000.Notice that workers get two-thirds of output, which is consistent with what we know about theCobb –Douglas production function from Chapter 3.c. The real wage is now equal to 11 (10% above the equilibrium level of 10).Firms will use their labor demand function to decide how many workers to hire at the given realwage of 11 and capital stock of 27,000:So 751 workers will be hired for a total compensation of 8,261 units of output. To find the newlevel of output, plug the new value for labor and the value for capital into the production function and you will find Y = 12,393.d. The policy redistributes output from the 249 workers who become involuntarily unemployed tothe 751 workers who get paid more than before. The lucky workers benefit less than the losers lose as the total compensation to the working class falls from 10,000 to 8,261 units of output.e. This problem does focus on the analysis of two effects of the minimum-wage laws: they raise thewage for some workers while downward-sloping labor demand reduces the total number of jobs. Note, however, that if labor demand is less elastic than in this example, then the loss ofemployment may be smaller, and the change in worker income might be positive.6. a. The labor demand curve is given by the marginal product of labor schedule faced by firms. If acountry experiences a reduction in productivity, then the labor demand curve shifts to the left as in Figure 7-1. If labor becomes less productive, then at any given real wage, firms demand less labor. b. If the labor market is always in equilibrium, then, assuming a fixed labor supply, an adverseproductivity shock causes a decrease in the real wage but has no effect on employment orunemployment, as in Figure 7-2.c. If unions constrain real wages to remain unaltered, then as illustrated in Figure 7-3, employment falls to L 1 and unemployment equals L – L 1.This example shows that the effect of a productivity shock on an economy depends on the role ofunions and the response of collective bargaining to such a change.7. a. If workers are free to move between sectors, then the wage in each sector will be equal. If the wages were not equal then workers would have an incentive to move to the sector with the higher wage and this would cause the higher wage to fall, and the lower wage to rise until they were equal.b. Since there are 100 workers in total, L S = 100 – L M . We can substitute this expression into thelabor demand for services equation, and call the wage w since it is the same in both sectors:L S = 100 – L M = 100 – 4wL M = 4w.Now set this equal to the labor demand for manufacturing equation and solve for w:4w = 200 – 6ww = $20.Substitute the wage into the two labor demand equations to find L M is 80 and L S is 20.c. If the wage in manufacturing is equal to $25 then L M is equal to 50.d. There are now 50 workers employed in the service sector and the wage w S is equal to $12.50.e. The wage in manufacturing will remain at $25 and employment will remain at 50. If thereservation wage for the service sector is $15 then employment in the service sector will be 40. Therefore, 10 people are unemployed and the unemployment rate is 10 percent.8. Real wages have risen over time in both the United States and Europe, increasing the reward forworking (the substitution effect) but also making people richer, so they want to “buy” more leisure (the income effect). If the income effect dominates, then people want to work less as real wages go up. This could explain the European experience, in which hours worked per employed person have fallen over time. If the income and substitution effects approximately cancel, then this could explain the U.S.experience, in which hours worked per person have stayed about constant. Economists do not have good theories for why tastes might differ, so they disagree on whether it is reasonable to think that Europeans have a larger income effect than do Americans.9. The vacant office space problem is similar to the unemployment problem; we can apply the sameconcepts we used in analyzing unemployed labor to analyze why vacant office space exists. There is a rate of office separation: firms that occupy offices leave, either to move to different offices or because they go out of business. There is a rate of office finding: firms that need office space (either to start up or expand) find empty offices. It takes time to match firms with available space. Different types of firms require spaces with different attributes depending on what their specific needs are. Also, because demand for different goods fluctuates, there are “sectoral shifts”—changes in the composition ofdemand among industries and regions that affect the profitability and office needs of different firms.。