Why a classic is a classic (Arnold Bennet)

- 格式:doc

- 大小:36.00 KB

- 文档页数:3

W h y a c l a s s i c i s a c l a s s i c(A r n o l dB e n n e t)Why a Classic Is a Classicby Arnold BennettThe large majority of our fellow-citizens care as much about literature as they care about aeroplanes or the programme of the Legislature. They do not ignore it; they are not quite indifferent to it. But their interest in it is faint and perfunctory; or, if their interest happens to be violent, it is spasmodic. Ask the two hundred thousand persons whose enthusiasm made the vogue of a popular novel ten years ago what they think of that novel now, and you will gather that they have utterly forgotten it, and that they would no more dream of reading it again than of reading Bishop Stubbs’s Select Charters. Probably if they did read it again they would not enjoy it—not because the said novel is a whit worse now than it was ten years ago; not because their taste has improved—but because they have not had sufficient practice to be able to rely on their taste as a means of permanent pleasure. They simply don’t know from on e day to the next what will please them.In the face of this one may ask: Why does the great and universal fame of classical authors continue? The answer is that the fame of classical authors is entirely independent of the majority. Do you suppose that if the fame of Shakespeare depended on the man in the street it would survive a fortnight? The fame of classical authors is originally made, and it is maintained, by a passionate few. Even when a first-class author has enjoyed immense success during his lifetime, the majority have never appreciated him so sincerely as they have appreciated second-rate men. He has always been reinforced by the ardour of the passionate few. And in the case of an author who has emerged into glory after his death the happy sequel has been due solely to the obstinate perseverance of the few. They could not leave him alone; they would not. They kept on savouring him, and talking about him, and buying him, and they generally behaved with such eager zeal, and they were so authoritative and sure of themselves, that at last the majority grew accustomed to the sound of his name and placidly agreed to the proposition that he was a genius; the majority really did not care very much either way.And it is by the passionate few that the renown of genius is kept alive from one generation to another. These few are always at work. They are always rediscovering genius. Their curiosity and enthusiasm are exhaustless, so that there is little chance of genius being ignored. And, moreover, they are always working either for or against the verdicts of the majority. The majority can make a reputation, but it is too careless to maintain it. If, by accident, the passionate few agree with the majority in a particular instance, they will frequently remind the majority that such and such a reputation has been made, and the majority will idly concur: “Ah, yes. By the way, wemust not forget that such and such a reputation exists.” Without that persistent memory-jogging the reputation would quickly fall into the oblivion which is death. The passionate few only have their way by reason of the fact that they are genuinely interested in literature, that literature matters to them. They conquer by their obstinacy alone, by their eternal repetition of the same statements. Do you suppose they could prove to the man in the street that Shakespeare was a great artist? The said man would not even understand the terms they employed. But when he is told ten thousand times, and generation after generation, that Shakespeare was a great artist, the said man believes—not by reason, but by faith. And he too repeats that Shakespeare was a great artist, and he buys the complete works of Shakespeare and puts them on his shelves, and he goes to see the marvellous stage-effects which accompany King Lear or Hamlet, and comes back religiously convinced that Shakespeare was a greatartist. All because the passionate few could not keep their admiration of Shakespeare to themselves. This is not cynicism; but truth. And it is important that those who wish to form their literary taste should grasp it.What causes the passionate few to make such a fuss about literature? There can be only one reply. They find a keen and lasting pleasure in literature. They enjoy literature as some men enjoy beer. The recurrence of this pleasure naturally keeps their interest in literature very much alive. They are for ever making new researches, for ever practising on themselves. They learn to understand themselves. They learn to know what they want. Their taste becomes surer and surer as their experience lengthens. They do not enjoy to-day what will seem tedious to them to-morrow. When they find a book tedious, no amount of popular clatter will persuade them that it is pleasurable; and when they find it pleasurable no chill silence of the street-crowds will affect their conviction that the book is good and permanent. They have faith in themselves. What are the qualities in a book which give keen and lasting pleasure to the passionate few? This is a question so difficult that it has never yet been completely answered. You may talk lightly about truth, insight, knowledge, wisdom, humour, and beauty. But these comfortable words do not really carry you very far, for each of them has to be defined, especially the first and last. It is all very well for Keats in his airy manner to assert that beauty is truth, truth beauty, and that that is all he knows or needs to know. I, for one, need to know a lot more. And I never shall know. Nobody, not even Hazlitt nor Sainte-Beuve, has ever finally explained why he thought a book beautiful. I take the first fine lines that come to hand—The woods of Arcady are dead,And over is their antique joy—and I say that those lines are beautiful, because they give me pleasure. But why? No answer! I only know that the passionate few will, broadly, agree with me in deriving this mysterious pleasure from those lines. I am only convinced that the liveliness of our pleasure in those and many other lines by the same author will ultimately cause the majority to believe, by faith, that W.B. Yeats is a genius. The one reassuringaspect of the literary affair is that the passionate few are passionate about the same things. A continuance of interest does, in actual practice, lead ultimately to the same judgments. There is only the difference in width of interest. Some of the passionate few lack catholicity, or, rather, the whole of their interest is confined to one narrow channel; they have none left over. These men help specially to vitalise the reputations of the narrower geniuses: such as Crashaw. But their active predilections never contradict the general verdict of the passionate few; rather they reinforce it.A classic is a work which gives pleasure to the minority which is intensely and permanently interested in literature. It lives on because the minority, eager to renew the sensation of pleasure, is eternally curious and is therefore engaged in an eternal process of rediscovery. A classic does not survive for any ethical reason. It does not survive because it conforms to certain canons, or because neglect would not kill it. It survives because it is a source of pleasure, and because the passionate few can no more neglect it than a bee can neglect a flower. The passionate few do not read “the right things” because they are right. That is to put the cart before the horse. “The right things” are the right things solely because the passionate few like reading them. Hence—and I now arrive at my point—the one primary essential to literary taste is a hot interest in literature. If you have that, all the rest will come. It matters nothing that at present you fail to find pleasure in certain classics. The driving impulse of your interest will force you to acquire experience, and experience will teach you the use of the means of pleasure. You do not know the secret ways of yourself: that is all. A continuance of interest must inevitably bring you to the keenest joys. But, of course, experience may be acquired judiciously or injudiciously, just as Putney may be reached via Walham Green or via St. Petersburg.。

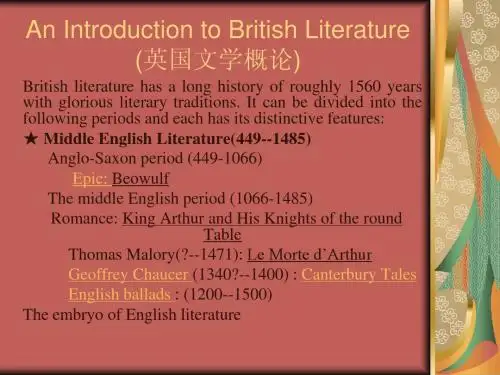

专八英美文学总结英国文学一、古英语时期的英国文学(499-1066)1、贝奥武夫2、阿尔弗雷德大帝:英国散文之父二、中古英语时期的英国文学1、allegory体非常盛行2、Romance开始上升到一定的高度3、高文爵士和绿衣骑士4、Willian Langlaud 《农夫皮尔斯的幻象》5、乔叟坎特伯雷故事集(英雄双韵体)6、托马斯.马洛礼《亚瑟王之死》三、文艺复兴时期的英国文学(伊丽莎白时代)(14-16世纪)1、托马斯.莫尔《乌托邦》2、Thomas Wyatt 和Henry Howard引入sonnet3、Philips Sidney 《The defense of Poesie》《阿卡迪亚》描述田园生活;现代长篇小说的先驱4、斯宾塞《仙后》诗人中的诗人;斯宾塞体诗节;5、莎士比亚:长篇叙事诗:《维纳斯和阿多尼斯》、《露克丝受辱记》四大悲剧:哈姆雷特、李尔王、奥赛罗、麦克白7、本.琼森风俗喜剧(comedy of manners)《人性互异》8、约翰.多恩“玄学派”诗歌创始人9、George Herbert 玄学派诗圣10、弗朗西斯.培根现代科学和唯物主义哲学创始人之一《Essays》英国发展史上的里程碑《学术的推进》和《新工具》四、启蒙时期(18世纪)1、约翰、弥尔顿:《失乐园》、《为英国人民争辩》2、约翰、班扬:《天路历程》religious allegory3、约翰、德莱顿:英国新古典主义的杰出代表、桂冠诗人;《论戏剧诗》4、亚历山大.蒲柏:英国新古典主义诗歌的重要代表;英雄双韵体的使用达到登峰造极的使用;《田园组诗》是其最早田园诗歌代表作5、托马斯、格雷:感伤主义中墓园诗派的代表人物《墓园挽歌》6、威廉、布莱克:天真之歌、经验之歌;7、罗伯特、彭斯:苏格兰最杰出的农民诗人;8、Richard Steel和Joseph Addison合作创办《The tatler》和《the spectator》9、Samuel defoe 英国现实主义小说的奠基人之一;《鲁滨逊漂流记》;《铲除非国教徒的捷径》,仪表达自己的不满;10、Jonathan Swift 《一个小小的建议》;《格列佛游记》;《桶的故事》;11、Samuel Richardson 英国现代小说的创始人;帕米拉;克拉丽莎;查尔斯.格蓝迪森爵士的历史;12、Henry Fielding 英国现实主义小说理论的奠基人;《约瑟夫。

成功者必看十大励志电影美剧电影成功不是一天能取得的,成功需具备的心理素质。

成功者在奋斗的路上少不了励志的心态,小编整理了一些成功者必看的励志电影,希望你喜欢。

十大成功者必看励志电影成功者必看十大励志电影1:《奔腾年代》(Seabiscuit)感悟:一个不甘寂寞的商人,从自行车配件维修:到销售汽车:再到经营马匹,本身他就是一个创业者奋斗的缩影:一个努力不息的英雄,自身的经历成为他演讲有力的支持与鼓励。

成功者必看十大励志电影2:《阿甘正传》(Forrest Gump)感悟:在踏上这个充满竞争与排挤的社会之前,《阿甘正传》教给你处世方的不是与世无争:息事宁人,而是为目标默默奋斗:乐天知命。

看了《阿甘正传》,创业者内心能多一份平静,少一份浮躁,就已经很宝贵了。

成功者必看十大励志电影3:《百万美元宝贝》(Million Dollar Baby)感悟:正如导演伊斯特伍德所说的,"这不是一个关于拳击的故事,是关于希望:梦想和爱的故事",创业者能从中认识到,金钱不是最重要的,希望+梦想+爱才是我们持之以恒奋斗的原因。

成功者必看十大励志电影4:《毕业生》(The Graduate)感悟:达斯汀.霍夫曼对未知世界的彷徨和向往,以及那个洋溢着激情和冲动的结尾,都一丝不差地契合了毕业生的心情。

从毕业生走上创业之路,正是摆脱彷徨,挥发激情的康庄大道。

成功者必看十大励志电影5:《当幸福来敲门》(The Pursuit of Happyness)感悟:你刚刚拿到大学文凭,雄心勃勃,希望在事业上大展身手,可是找工作的过程渐渐泯灭了你的雄心,四处碰壁后该怎么办?这时候,看这部片子,总能自我安慰一下:再怎么样,我也比主角幸运!至少我在创业,命运掌握在自己手中!成功者必看十大励志电影6:《律政俏佳人》(Legally Blonde)感悟:这不仅是一部给美国年轻一代尤其是年轻女性的励志电影,更象是一部告诉年轻女性们该如何去维护自己的权利的影片。

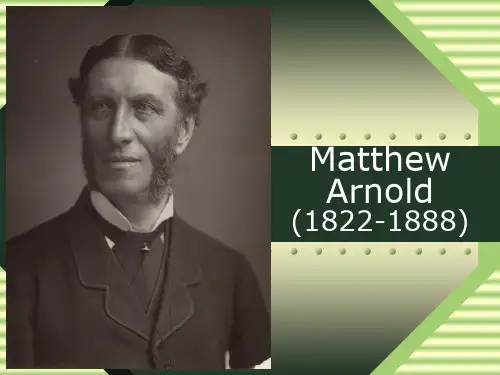

Matthew Arnold (1822-1888)The Heterological Thinkers•an autological word is a word expressing a property which it also possesses itselfe.g. the word "short" is short, "noun" is a noun, "English" is English•a heterological word is a word that does not apply to itselfe.g. "long" is not long, "verb" is not a verbThe Heterological Thinkers main concerns•challenged the very discipline of philosophy and its claims to arrive at truth through reason•emphasize instead of the role of emotion, the body, sexuality, the unconscious, as well as of pragmatic interests•deplore the effect of French RevolutionMatthew Arnold•British poet, cultural critic, educator •one of the founding figures of modern English criticism•appointed Professor of Poetry at Oxford in 1857•Literary Careerpoetry 1850s"Dover Beach"literary and social criticism 1860s "Essays in Critism" "Culture and Anarchy" on religious and esucational matters 1870sThe Function of Criticism •concern to counteract the philistinism of the world as defined by the English bourgeoisie with the imperatives of the immediate present.•redefine the central responsibilities of criticism (original & controversial)•creative power•the work of literary genius —"synthesis and exposition"•aim of literary work•task of criticismMajor Points•"the creation of a modern poet…implies a great critical effort behind it"•French Revolution—"took a political, practical character"—evaluation positivenegative—influenceIt creats an epoch of reaction or opposition against itselfMajor Points Disinterestedness (超然)•How is criticism to be disinterested?—by keeping aloof from the practical view of things —by following the law of its own nature—by steadily refusing to lend itself to any of those ulterior, political, practical considerations about ideals—by attempting to know the best that is known and thought in the world, and by in turn making this known, to creat a current of true and fresh ideas—by being independent of all interestsDisinterestedness•purpose:to lead man towards perfection •Criticism should embrace the Indian virtue of detachment, the Hindu ideal of ascetic (禁欲主义)renunciation(克己)of all worldly concerns.—contrast between the mass of peoplepracticalthe critic•Importance—without such a disinterested perspective truth and the highest culture will not be possible—if a critic can truely porform this, he will move beyond insularity•Every critic should try to master at least one literature in a language other than its own•Culture and Anarchy(1869)—both redefine "culture" and affirms the need for it in a modern industrial society devoted to mechanism and profit.—culture is a study of perfection which has an intellectual and an ethical componentculture•aims of culture and religion (similarities)—aim—the cultivation of inwardness—expands our gifts of thought and feeling, and fosters growth in wisdom and beauty —require the individual to be part of a general movement toward perfectionculture advances beyond natureculture•function of culture—to purge our minds of the effects of material and narrow preoccupations —to stem the common tide of men's thoughts in a wealthy and industrial communityculture shares the same spirt as poetrypoetry will replace the function of religion•Task of both criticism and culture—to place the pragmatic bourgeois vision of life in a broader historical and international text•purpose of criticism—political—an instrument which might lift us beyond an immediate present governed by the narrow principles of utility, material progress, and the dictation of all theory by the exigencies of practice.summary—the bourgeois thought concentrates on the "outward", so Arnold emphasizes more on the human being's "inward" capabilities. —Arnold's key notions of criticism, culture, and poetry are all modes of "inwardness", aimed to counteract the "externality" of the bourgeois worldThe Study of Poetry (1880)•Arnold's world view—deeply humanist—writes in the tradition of a humanism •Arnold's text is the most influential text ofliterary humanism—it insists on the social and culturalfunctions of literature—its ability to civilize and to cultivatemorality—it provides a bulwark against themechanistic excesses of modern civilization•religion —threaten by science andideology of the "fact"•philosophy —powerless•poetry —spiritual and emotional support —interpret life—a criticism of lifePoetry's high function is actually to replace religion and philosophy•notions of the classic and tradition—we need to be sure that our estimate of poetry is "real" rather than historical or personal—an author was important for the development of language or certain literary traditions without having himself composed a classic•How do we arrive at this real estimate of what constitutes a classic?—a theroy or the practice of using touchstones •defects—lack of engagement with formal qualities —lack any sense of engagement in historical。

高一艺术与文化探索英语阅读理解25题1<背景文章>Western classical music has a long and rich history. It dates back to the Medieval period when Gregorian chants were popular. These chants were monophonic, meaning they had a single melody line.As time passed, polyphony began to develop. Composers started adding more voices and melodies to create complex musical textures. In the Renaissance period, composers like Palestrina created beautiful choral works.The Baroque period saw the emergence of great composers such as Bach and Handel. Bach's music is known for its complexity and technical brilliance. His works include the Brandenburg Concertos and the Mass in B Minor. Handel is famous for his operas and oratorios, such as Messiah.The Classical period brought composers like Mozart and Haydn. Mozart's music is characterized by its elegance and beauty. Haydn is known for his symphonies and string quartets.The Romantic period was a time of great emotional expression. Composers like Beethoven, Chopin, and Schumann created music that was full of passion and drama. Beethoven's symphonies are some of the most famous works in classical music.In the 20th century, classical music continued to evolve. Composers experimented with new forms and styles.1. Gregorian chants are ________.A. polyphonicB. monophonicC. homophonicD. heterophonic答案:B。

高一艺术与文化探索英语阅读理解25题1<背景文章>Western classical music has a long and rich history. It began in Europe during the Middle Ages and has developed over the centuries. One of the most important periods in the history of Western classical music is the Baroque era. This period was characterized by ornate and elaborate musical compositions. Composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel were prominent figures during this time. Bach's music is known for its complexity and technical brilliance. His works include the Brandenburg Concertos and the Well-Tempered Clavier. Handel's most famous work is probably the Messiah.The Classical period followed the Baroque era. Composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Joseph Haydn were important during this time. Mozart's music is known for its beauty and elegance. His works include symphonies, operas, and chamber music. Haydn is often called the "father of the symphony" because of his contributions to the development of this form.The Romantic period was a time of great emotional expression in music. Composers such as Ludwig van Beethoven, Frédéric Chopin, and Robert Schumann were prominent during this time. Beethoven's music isknown for its power and passion. His works include symphonies, piano sonatas, and string quartets. Chopin's music is known for its lyricism and emotional depth. His works include piano preludes, nocturnes, and waltzes. Schumann's music is known for its romanticism and emotional intensity. His works include symphonies, piano music, and lieder.In the 20th century, Western classical music continued to evolve. Composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, and Sergei Prokofiev were important during this time. Stravinsky's music is known for its innovation and experimentation. His works include The Rite of Spring and The Firebird. Schoenberg is known for his development of atonal music. Prokofiev's music is known for its energy and vitality. His works include symphonies, ballets, and piano music.Western classical music has had a profound influence on the development of music around the world. It has inspired countless composers and musicians and continues to be performed and enjoyed by people of all ages.1. Who is often called the "father of the symphony"?A. Johann Sebastian BachB. Wolfgang Amadeus MozartC. Joseph HaydnD. Ludwig van Beethoven答案:C。

初二英语音乐类型阅读理解30题1<背景文章>Classical music is a genre that has stood the test of time. It is known for its elegance, complexity, and emotional depth. Classical music often features beautiful melodies, rich harmonies, and intricate rhythms.One of the most famous composers of classical music is Ludwig van Beethoven. His works are known for their power and passion. Another great composer is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart's music is characterized by its beauty and grace.Classical music can have a profound impact on people. It can calm the mind, reduce stress, and improve concentration. Listening to classical music can also be a great way to relax and unwind after a long day.Classical music is performed by orchestras, which consist of many different instruments. The symphony orchestra typically includes strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion instruments.Classical music has a long history and has influenced many other genres of music. It continues to be popular today and is enjoyed by people all over the world.1. Classical music is known for its ___, complexity, and emotional depth.A. simplicityB. eleganceC. loudnessD. dullness答案:B。

英语电影经典对话English Movie Classic Dialogues。

English movies have always been popular for their captivating stories, brilliant performances, and memorable dialogues. These dialogues have the power to touch our hearts, make us laugh, or leave us pondering about life. In this article, we will explore some of the most iconic dialogues from English movies.1. "Here's looking at you, kid." Casablanca (1942)。

This timeless dialogue spoken by Humphrey Bogart in the movie Casablanca has become an epitome of romance. It is a declaration of love and longing, capturing the essence of the film's bittersweet love story.2. "I'll be back." The Terminator (1984)。

Arnold Schwarzenegger's iconic line from The Terminator has become a pop culture phenomenon. This simple yet powerful dialogue has become synonymous with the character and the movie itself.3. "You can't handle the truth!" A Few Good Men (1992)。

英语台词超酷带翻译Title: Super Cool English Dialogue with Translation。

As language learners, we all know the importance of practicing our listening and speaking skills. One way to do this is by watching movies and TV shows in English. Not only can we improve our comprehension, but we can also learn new vocabulary and phrases. In this article, we will provide you with some super cool English dialogues from popular movies and TV shows, along with their translations.1. "I'm gonna make him an offer he can't refuse." The Godfather (1972)。

Translation: 我会给他一个他无法拒绝的提议。

This iconic line from The Godfather is spoken by Marlon Brando's character, Vito Corleone. It means that he is going to offer someone something so irresistible that they won't be able to say no.2. "May the Force be with you." Star Wars (1977)。

有关阅读的英语名言(经典中英文对照50句)1.知识是心灵的眼睛。

——德雷克斯Knowledge is the eye of the mind -- Drakes2.知识是心灵的活动。

——本·琼森Knowledge is the activity of the mind -- Ben Jonsson3.不读书的人,思想就会停止。

——狄德罗Without reading, the mind will stop -- Diderot4.不怕读得少,只怕记不牢。

——徐特立Not afraid of reading less, I remember -- Xu Teli5.读书使人心明眼亮。

——伏尔泰reading makes people see and think clearly -- Voltaire6.知识越多越令人陶醉。

——威·柯珀The more knowledge the moreintoxicated -- Viv Cope7.吾生也有涯,而知也无涯。

——庄子I have a career, and I know it -- Chuang-tzu8.常识很少会把我们引入歧途。

一爱·扬格common sense rarely lead usastray -- Ai Young9.非淡泊无以明志,非宁静无以致远。

——诸葛亮Non indifferent to Ming, quiet Zhi yuan -- Zhu Geliang10.知识是为老年准备的最好的食粮。

——亚里士多德Knowledge is the best food for the elderly -- Aristotle11.读书而不思考,等于吃饭而不消化。

一—波尔克Reading without thinking, is to eat and do not digest -- Polk12.天赋如同自然花木,要用学习来修剪。

Why a Classic Is a Classicby Arnold BennettThe large majority of our fellow-citizens care as much about literature as they care about aeroplanes or the programme of the Legislature. They do not ignore it; they are not quite indifferent to it. But their interest in it is faint and perfunctory; or, if their interest happens to be violent, it is spasmodic. Ask the two hundred thousand persons whose enthusiasm made the vogue of a popular novel ten years ago what they think of that novel now, and you will gather that they have utterly forgotten it, and that they would no more dream of reading it again than of reading Bishop Stubbs’s Select Charters. Probably if they did read it again they would not enjoy it—not because the said novel is a whit worse now than it was ten years ago; not because their taste has improved—but because they have not had sufficient practice to be able to rely on their taste as a means of permanent pleasure. They simply don’t know from one day to the next what will please them.In the face of this one may ask: Why does the great and universal fame of classical authors continue? The answer is that the fame of classical authors is entirely independent of the majority. Do you suppose that if the fame of Shakespeare depended on the man in the street it would survive a fortnight? The fame of classical authors is originally made, and it is maintained, by a passionate few. Even when a first-class author has enjoyed immense success during his lifetime, the majority have never appreciated him so sincerely as they have appreciated second-rate men. He has always been reinforced by the ardour of the passionate few. And in the case of an author who has emerged into glory after his death the happy sequel has been due solely to the obstinate perseverance of the few. They could not leave him alone; they would not. They kept on savouring him, and talking about him, and buying him, and they generally behaved with such eager zeal, and they were so authoritative and sure of themselves, that at last the majority grew accustomed to the sound of his name and placidly agreed to the proposition that he was a genius; the majority really did not care very much either way.And it is by the passionate few that the renown of genius is kept alive from one generation to another. These few are always at work. They are always rediscovering genius. Their curiosity and enthusiasm are exhaustless, so that there is little chance of genius being ignored. And, moreover, they are always working either for or against the verdicts of the majority. The majority can make a reputation, but it is too careless to maintain it. If, by accident, the passionate few agree with the majority in a particular instance, they will frequently remind the majority that such and such a reputation has be en made, and the majority will idly concur: “Ah, yes. By the way, we must not forget that such and such a reputation exists.” Without that persistent memory-jogging the reputation would quickly fall into the oblivion which is death. The passionate few only have their way by reason of the fact that they are genuinely interested in literature, that literature matters to them. They conquer by their obstinacy alone, by their eternal repetition of the same statements. Do you suppose they could prove to the man in the street that Shakespeare was a great artist? The said man would not even understand the terms they employed. But when he is told ten thousand times,and generation after generation, that Shakespeare was a great artist, the said man believes—not by reason, but by faith. And he too repeats that Shakespeare was a great artist, and he buys the complete works of Shakespeare and puts them on his shelves, and he goes to see the marvellous stage-effects which accompany King Lear or Hamlet, and comes back religiously convinced that Shakespeare was a great artist. All because the passionate few could not keep their admiration of Shakespeare to themselves. This is not cynicism; but truth. And it is important that those who wish to form their literary taste should grasp it.What causes the passionate few to make such a fuss about literature? There can be only one reply. They find a keen and lasting pleasure in literature. They enjoy literature as some men enjoy beer. The recurrence of this pleasure naturally keeps their interest in literature very much alive. They are for ever making new researches, for ever practising on themselves. They learn to understand themselves. They learn to know what they want. Their taste becomes surer and surer as their experience lengthens. They do not enjoy to-day what will seem tedious to them to-morrow. When they find a book tedious, no amount of popular clatter will persuade them that it is pleasurable; and when they find it pleasurable no chill silence of the street-crowds will affect their conviction that the book is good and permanent. They have faith in themselves. What are the qualities in a book which give keen and lasting pleasure to the passionate few? This is a question so difficult that it has never yet been completely answered. You may talk lightly about truth, insight, knowledge, wisdom, humour, and beauty. But these comfortable words do not really carry you very far, for each of them has to be defined, especially the first and last. It is all very well for Keats in his airy manner to assert that beauty is truth, truth beauty, and that that is all he knows or needs to know. I, for one, need to know a lot more. And I never shall know. Nobody, not even Hazlitt nor Sainte-Beuve, has ever finally explained why he thought a book beautiful. I take the first fine lines that come to hand—The woods of Arcady are dead,And over is their antique joy—and I say that those lines are beautiful, because they give me pleasure. But why? No answer! I only know that the passionate few will, broadly, agree with me in deriving this mysterious pleasure from those lines. I am only convinced that the liveliness of our pleasure in those and many other lines by the same author will ultimately cause the majority to believe, by faith, that W.B. Yeats is a genius. The one reassuring aspect of the literary affair is that the passionate few are passionate about the same things. A continuance of interest does, in actual practice, lead ultimately to the same judgments. There is only the difference in width of interest. Some of the passionate few lack catholicity, or, rather, the whole of their interest is confined to one narrow channel; they have none left over. These men help specially to vitalise the reputations of the narrower geniuses: such as Crashaw. But their active predilections never contradict the general verdict of the passionate few; rather they reinforce it.A classic is a work which gives pleasure to the minority which is intensely and permanently interested in literature. It lives on because the minority, eager to renew the sensation of pleasure, is eternally curious and is therefore engaged in an eternal process of rediscovery. A classic does not survive for any ethical reason. It does not survive because it conforms to certain canons, orbecause neglect would not kill it. It survives because it is a source of pleasure, and because the passionate few can no more neglect it than a bee can neglect a flower. The passionate few do not read “the right things” because they are right. That is to put the cart before the horse. “The right things” are the right things solely because the passionate few like reading them. Hence—and I now arrive at my point—the one primary essential to literary taste is a hot interest in literature. If you have that, all the rest will come. It matters nothing that at present you fail to find pleasure in certain classics. The driving impulse of your interest will force you to acquire experience, and experience will teach you the use of the means of pleasure. You do not know the secret ways of yourself: that is all. A continuance of interest must inevitably bring you to the keenest joys. But, of course, experience may be acquired judiciously or injudiciously, just as Putney may be reached via Walham Green or via St. Petersburg.。