Maturation of spatial-frequency and orientation selectivity of primary visual cortex

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:457.10 KB

- 文档页数:4

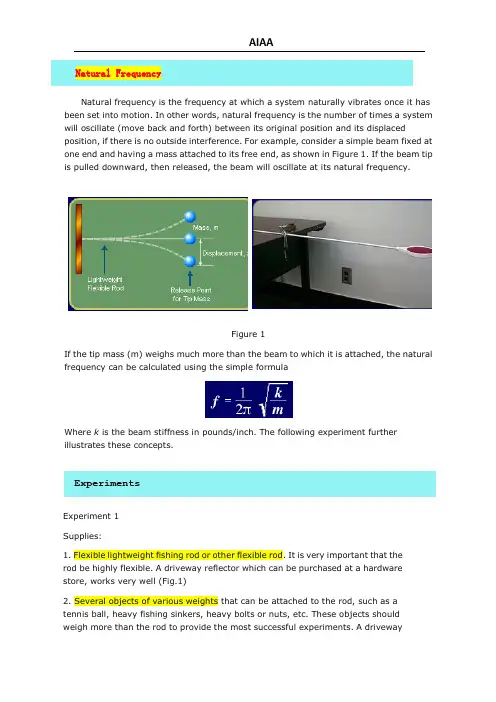

Natural frequency is the frequency at which a system naturally vibrates once it has been set into motion. In other words, natural frequency is the number of times a system will oscillate (move back and forth) between its original position and its displaced position, if there is no outside interference. For example, consider a simple beam fixed at one end and having a mass attached to its free end, as shown in Figure 1. If the beam tip is pulled downward, then released, the beam will oscillate at its natural frequency.Figure 1If the tip mass (m) weighs much more than the beam to which it is attached, the natural frequency can be calculated using the simple formulaWhere k is the beam stiffness in pounds/inch. The following experiment further illustrates these concepts.ExperimentsExperiment 1Supplies:1. Flexible lightweight fishing rod or other flexible rod. It is very important thatthe rod be highly flexible. A driveway reflector which can be purchased at a hardware store, works very well (Fig.1)2. Several objects of various weights that can be attached to the rod, such as a tennis ball, heavy fishing sinkers, heavy bolts or nuts, etc. These objects should weigh more than the rod to provide the most successful experiments. A drivewayreflector as shown in Figures 1 and 2 provides a convenient location for attaching weights3. Table to which the rod can be attached.4. C-clamp for fastening the rod to the edge of the table.5. Stopwatch or clock with capability to indicate seconds.Procedure:1. Clamp one end of the flexible rod to the table. Start without any tip weights. If a driveway reflector rod is used, the reflector should be removed initially.2. Pull the end of the rod downward, and then release it. If the rod moves slowly enough, count the number of oscillations (rod moving through complete cycle and back to release point) that occur in 30 seconds. The frequency is the number of oscillations divided by seconds.3. Now attach one of the weights to the free end of the rod, (such as the reflector tip mass in figure 1) and again pull it downward then release it. Count the number of oscillations and divide by the time to get frequency.4. Repeat step 3 for different tip weights. Plot frequency vs. tip weight. How does frequency change with the weight?5. Calculate the natural frequency and compare to the experiment described in steps 3 and 4 using the following procedure:(a). Place a yardstick near the free end of the flexible rod, with one end of the yardstick resting on the floor. Note the location of the end of the rod and mark it on the yardstick.(b). Attach several different weights to the end of the rod and measure the distance (x) that the end of the rod moves downward (see Figure 2) for each weight. Graph weight versus displacement. The stiffness K is the slope of this graph (rise/run), units (lb/in).Figure 2(c). Calculate the natural frequency using the formulawhere stiffness k is measured in step (b) and m equals the tip weight divided by 386.1. How does this frequency compare to the measured natural frequency?(d). Repeat steps (c) for different tip weights. Plot frequency vs. tip weight. How does this graph compare to the experiment results from step 4? More advanced students should overlay the two graphs.ResonanceResonance is the buildup of large vibration amplitude that occurs when a structure or an object is excited at its natural frequency. Resonance can be either desirable or undesirable. Acoustic resonance, a desirable resonance, occurs in many different musical instruments. It also occurs in auditoriums. Undesirable mechanical resonance can cause bridges to collapse, aircraft wings to break, and machinery to break or malfunction. For example, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge experienced large vibration amplitudes and catastrophic structural failure due to wind gusts.Experiment 2: Resonance and Resonating Chambers (Tuning Fork withSoda Can)Supplies:1.Clean, empty soda can2 Tuning forkDirections:Tap the fork and listen. Hold it over the opening of the can as shown in Figure 3 and listen.Notice that the sound gets louder when it is held over the opening.Figure 3Explanation:The can is a hollow container with an opening and is called a resonator. Its shape acts like a resonating chamber, like a drum or the bell of a tuba. The vibrating tuning fork held near the opening causes the can and the air in the can to vibrate. This is called resonance. The sound becomes intensified and amplified.References:Holiday and Resnick “Physics”。

1.BackgroundHoward Earl Gardener’s work has been marked by a desire not to just describe the world but to help to create the condition to change it. The scale of his contribution can be gauged from following comments in his introduction to the tenth anniversary edition of Howard Gardener’s classic work Frames Of Mind. The theory of multiple intelligences :霍华德厄尔加德纳的研究不只是描述这个世界,而是造条件去改变它。

他的贡献在十周年纪念版的《霍华德加德纳的经典智力结构》这本书中有所介绍。

多元智能的理论:In the heyday of the psychometric and behaviorist eras, it was generally believed that intelligence was a single entity that was inherited; and that human beings – initially a blank slate – could be trained to learn anything, provided that it was presented in an appropriate way. Nowadays an intelligences, quite independent of each other; that each intelligence has its own strengths and constraints; that the mind is far from unencumbered at birth; and that it is unexpectedly difficult to teach things that go against early’naïve’ theories of that challenge the natural lines of force within an intelligence and its matching domains.全盛时期的心理和行为主义时代,人们普遍认为,智力是一个单一的实体,是可以继承的;而人类——最初就像一张白纸可以通过训练学习任何东西,只需要有一个适当的方式。

IEEE Std 1159-1995 IEEE Recommended Practice for Monitoring Electric Power QualitySponsorIEEE Standards Coordinating Committee 22 onPower QualityApproved June 14, 1995IEEE Standards BoardAbstract: The monitoring of electric power quality of ac power systems, definitions of power quality terminology, impact of poor power quality on utility and customer equipment, and the measurement of electromagnetic phenomena are covered.Keywords: data interpretation, electric power quality, electromagnetic phenomena, monitoring, power quality definitionsIEEE Standards documents are developed within the Technical Committees of the IEEE Societies and the Standards Coordinating Committees of the IEEE Standards Board. Members of the committees serve voluntarily and without compensation. They are not necessarily members of the Institute. The standards developed within IEEE represent a consensus of the broad expertise on the subject within the Institute as well as those activities outside of IEEE that have expressed an interest in partici-pating in the development of the standard.Use of an IEEE Standard is wholly voluntary. The existence of an IEEE Standard does not imply that there are no other ways to produce, test, measure, purchase, mar-ket, or provide other goods and services related to the scope of the IEEE Standard. Furthermore, the viewpoint expressed at the time a standard is approved and issued is subject to change brought about through developments in the state of the art and com-ments received from users of the standard. Every IEEE Standard is subjected to review at least every Þve years for revision or reafÞrmation. When a document is more than Þve years old and has not been reafÞrmed, it is reasonable to conclude that its contents, although still of some value, do not wholly reßect the present state of the art. Users are cautioned to check to determine that they have the latest edition of any IEEE Standard.Comments for revision of IEEE Standards are welcome from any interested party, regardless of membership afÞliation with IEEE. Suggestions for changes in docu-ments should be in the form of a proposed change of text, together with appropriate supporting comments.Interpretations: Occasionally questions may arise regarding the meaning of portions of standards as they relate to speciÞc applications. When the need for interpretations is brought to the attention of IEEE, the Institute will initiate action to prepare appro-priate responses. Since IEEE Standards represent a consensus of all concerned inter-ests, it is important to ensure that any interpretation has also received the concurrence of a balance of interests. For this reason IEEE and the members of its technical com-mittees are not able to provide an instant response to interpretation requests except in those cases where the matter has previously received formal consideration.Comments on standards and requests for interpretations should be addressed to:Secretary, IEEE Standards Board445 Hoes LaneP.O. Box 1331Piscataway, NJ 08855-1331USAIntroduction(This introduction is not part of IEEE Std 1159-1995, IEEE Recommended Practice for Monitoring Electric Power Quality.)This recommended practice was developed out of an increasing awareness of the difÞculty in comparing results obtained by researchers using different instruments when seeking to characterize the quality of low-voltage power systems. One of the initial goals was to promote more uniformity in the basic algorithms and data reduction methods applied by different instrument manufacturers. This proved difÞcult and was not achieved, given the free market principles under which manufacturers design and market their products. However, consensus was achieved on the contents of this recommended practice, which provides guidance to users of monitoring instruments so that some degree of comparisons might be possible.An important Þrst step was to compile a list of power quality related deÞnitions to ensure that contributing parties would at least speak the same language, and to provide instrument manufacturers with a common base for identifying power quality phenomena. From that starting point, a review of the objectives of moni-toring provides the necessary perspective, leading to a better understanding of the means of monitoringÑthe instruments. The operating principles and the application techniques of the monitoring instruments are described, together with the concerns about interpretation of the monitoring results. Supporting information is provided in a bibliography, and informative annexes address calibration issues.The Working Group on Monitoring Electric Power Quality, which undertook the development of this recom-mended practice, had the following membership:J. Charles Smith, Chair Gil Hensley, SecretaryLarry Ray, Technical EditorMark Andresen Thomas Key John RobertsVladi Basch Jack King Anthony St. JohnRoger Bergeron David Kreiss Marek SamotyjJohn Burnett Fran•ois Martzloff Ron SmithJohn Dalton Alex McEachern Bill StuntzAndrew Dettloff Bill Moncrief John SullivanDave GrifÞth Allen Morinec David VannoyThomas Gruzs Ram Mukherji Marek WaclawlakErich Gunther Richard Nailen Daniel WardMark Kempker David Pileggi Steve WhisenantHarry RauworthIn addition to the working group members, the following people contributed their knowledge and experience to this document:Ed Cantwell Christy Herig Tejindar SinghJohn Curlett Allan Ludbrook Maurice TetreaultHarshad MehtaiiiThe following persons were on the balloting committee:James J. Burke David Kreiss Jacob A. RoizDavid A. Dini Michael Z. Lowenstein Marek SamotyjW. Mack Grady Fran•ois D. Martzloff Ralph M. ShowersDavid P. Hartmann Stephen McCluer J. C. SmithMichael Higgins A. McEachern Robert L. SmithThomas S. Key W. A. Moncrief Daniel J. WardJoseph L. KoepÞnger P. Richman Charles H. WilliamsJohn M. RobertsWhen the IEEE Standards Board approved this standard on June 14, 1995, it had the following membership:E. G. ÒAlÓ Kiener, Chair Donald C. Loughry,Vice ChairAndrew G. Salem,SecretaryGilles A. Baril Richard J. Holleman Marco W. MigliaroClyde R. Camp Jim Isaak Mary Lou PadgettJoseph A. Cannatelli Ben C. Johnson John W. PopeStephen L. Diamond Sonny Kasturi Arthur K. ReillyHarold E. Epstein Lorraine C. Kevra Gary S. RobinsonDonald C. Fleckenstein Ivor N. Knight Ingo RuschJay Forster*Joseph L. KoepÞnger*Chee Kiow TanDonald N. Heirman D. N. ÒJimÓ Logothetis Leonard L. TrippL. Bruce McClung*Member EmeritusAlso included are the following nonvoting IEEE Standards Board liaisons:Satish K. AggarwalRichard B. EngelmanRobert E. HebnerChester C. TaylorRochelle L. SternIEEE Standards Project EditorivContentsCLAUSE PAGE 1.Overview (1)1.1Scope (1)1.2Purpose (2)2.References (2)3.Definitions (2)3.1Terms used in this recommended practice (2)3.2Avoided terms (7)3.3Abbreviations and acronyms (8)4.Power quality phenomena (9)4.1Introduction (9)4.2Electromagnetic compatibility (9)4.3General classification of phenomena (9)4.4Detailed descriptions of phenomena (11)5.Monitoring objectives (24)5.1Introduction (24)5.2Need for monitoring power quality (25)5.3Equipment tolerances and effects of disturbances on equipment (25)5.4Equipment types (25)5.5Effect on equipment by phenomena type (26)6.Measurement instruments (29)6.1Introduction (29)6.2AC voltage measurements (29)6.3AC current measurements (30)6.4Voltage and current considerations (30)6.5Monitoring instruments (31)6.6Instrument power (34)7.Application techniques (35)7.1Safety (35)7.2Monitoring location (38)7.3Equipment connection (41)7.4Monitoring thresholds (43)7.5Monitoring period (46)8.Interpreting power monitoring results (47)8.1Introduction (47)8.2Interpreting data summaries (48)8.3Critical data extraction (49)8.4Interpreting critical events (51)8.5Verifying data interpretation (59)vANNEXES PAGE Annex A Calibration and self testing (informative) (60)A.1Introduction (60)A.2Calibration issues (61)Annex B Bibliography (informative) (63)B.1Definitions and general (63)B.2Susceptibility and symptomsÑvoltage disturbances and harmonics (65)B.3Solutions (65)B.4Existing power quality standards (67)viIEEE Recommended Practice for Monitoring Electric Power Quality1. Overview1.1 ScopeThis recommended practice encompasses the monitoring of electric power quality of single-phase and polyphase ac power systems. As such, it includes consistent descriptions of electromagnetic phenomena occurring on power systems. The document also presents deÞnitions of nominal conditions and of deviations from these nominal conditions, which may originate within the source of supply or load equipment, or from interactions between the source and the load.Brief, generic descriptions of load susceptibility to deviations from nominal conditions are presented to identify which deviations may be of interest. Also, this document presents recommendations for measure-ment techniques, application techniques, and interpretation of monitoring results so that comparable results from monitoring surveys performed with different instruments can be correlated.While there is no implied limitation on the voltage rating of the power system being monitored, signal inputs to the instruments are limited to 1000 Vac rms or less. The frequency ratings of the ac power systems being monitored are in the range of 45Ð450 Hz.Although it is recognized that the instruments may also be used for monitoring dc supply systems or data transmission systems, details of application to these special cases are under consideration and are not included in the scope. It is also recognized that the instruments may perform monitoring functions for envi-ronmental conditions (temperature, humidity, high frequency electromagnetic radiation); however, the scope of this document is limited to conducted electrical parameters derived from voltage or current measure-ments, or both.Finally, the deÞnitions are solely intended to characterize common electromagnetic phenomena to facilitate communication between various sectors of the power quality community. The deÞnitions of electromagnetic phenomena summarized in table 2 are not intended to represent performance standards or equipment toler-ances. Suppliers of electricity may utilize different thresholds for voltage supply, for example, than the ±10% that deÞnes conditions of overvoltage or undervoltage in table 2. Further, sensitive equipment may mal-function due to electromagnetic phenomena not outside the thresholds of the table 2 criteria.1IEEEStd 1159-1995IEEE RECOMMENDED PRACTICE FOR 1.2 PurposeThe purpose of this recommended practice is to direct users in the proper monitoring and data interpretation of electromagnetic phenomena that cause power quality problems. It deÞnes power quality phenomena in order to facilitate communication within the power quality community. This document also forms the con-sensus opinion about safe and acceptable methods for monitoring electric power systems and interpreting the results. It further offers a tutorial on power system disturbances and their common causes.2. ReferencesThis recommended practice shall be used in conjunction with the following publications. When the follow-ing standards are superseded by an approved revision, the revision shall apply.IEC 1000-2-1 (1990), Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)ÑPart 2 Environment. Section 1: Description of the environmentÑelectromagnetic environment for low-frequency conducted disturbances and signaling in public power supply systems.1IEC 50(161)(1990), International Electrotechnical V ocabularyÑChapter 161: Electromagnetic Compatibility. IEEE Std 100-1992, IEEE Standard Dictionary of Electrical and Electronic Terms (ANSI).2IEEE Std 1100-1992, IEEE Recommended Practice for Powering and Grounding Sensitive Electronic Equipment (Emerald Book) (ANSI).3. DeÞnitionsThe purpose of this clause is to present concise deÞnitions of words that convey the basic concepts of power quality monitoring. These terms are listed below and are expanded in clause 4. The power quality commu-nity is also pervaded by terms that have no scientiÞc deÞnition. A partial listing of these words is included in 3.2; use of these terms in the power quality community is discouraged. Abbreviations and acronyms that are employed throughout this recommended practice are listed in 3.3.3.1 Terms used in this recommended practiceThe primary sources for terms used are IEEE Std 100-19923 indicated by (a), and IEC 50 (161)(1990) indi-cated by (b). Secondary sources are IEEE Std 1100-1992 indicated by (c), IEC-1000-2-1 (1990) indicated by (d) and UIE -DWG-3-92-G [B16]4. Some referenced deÞnitions have been adapted and modiÞed in order to apply to the context of this recommended practice.3.1.1 accuracy: The freedom from error of a measurement. Generally expressed (perhaps erroneously) as percent inaccuracy. Instrument accuracy is expressed in terms of its uncertaintyÑthe degree of deviation from a known value. An instrument with an uncertainty of 0.1% is 99.9% accurate. At higher accuracy lev-els, uncertainty is typically expressed in parts per million (ppm) rather than as a percentage.1IEC publications are available from IEC Sales Department, Case Postale 131, 3, rue de VarembŽ, CH-1211, Gen•ve 20, Switzerland/ Suisse. IEC publications are also available in the United States from the Sales Department, American National Standards Institute, 11 West 42nd Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10036, USA.2IEEE publications are available from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 445 Hoes Lane, P.O. Box 1331, Piscataway, NJ 08855-1331, USA.3Information on references can be found in clause 2.4The numbers in brackets correspond to those bibliographical items listed in annex B.2IEEE MONITORING ELECTRIC POWER QUALITY Std 1159-1995 3.1.2 accuracy ratio: The ratio of an instrumentÕs tolerable error to the uncertainty of the standard used to calibrate it.3.1.3 calibration: Any process used to verify the integrity of a measurement. The process involves compar-ing a measuring instrument to a well defined standard of greater accuracy (a calibrator) to detect any varia-tions from specified performance parameters, and making any needed compensations. The results are then recorded and filed to establish the integrity of the calibrated instrument.3.1.4 common mode voltage: A voltage that appears between current-carrying conductors and ground.b The noise voltage that appears equally and in phase from each current-carrying conductor to ground.c3.1.5 commercial power: Electrical power furnished by the electric power utility company.c3.1.6 coupling: Circuit element or elements, or network, that may be considered common to the input mesh and the output mesh and through which energy may be transferred from one to the other.a3.1.7 current transformer (CT): An instrument transformer intended to have its primary winding con-nected in series with the conductor carrying the current to be measured or controlled.a3.1.8 dip: See: sag.3.1.9 dropout: A loss of equipment operation (discrete data signals) due to noise, sag, or interruption.c3.1.10 dropout voltage: The voltage at which a device fails to operate.c3.1.11 electromagnetic compatibility: The ability of a device, equipment, or system to function satisfacto-rily in its electromagnetic environment without introducing intolerable electromagnetic disturbances to any-thing in that environment.b3.1.12 electromagnetic disturbance: Any electromagnetic phenomena that may degrade the performance of a device, equipment, or system, or adversely affect living or inert matter.b3.1.13 electromagnetic environment: The totality of electromagnetic phenomena existing at a given location.b3.1.14 electromagnetic susceptibility: The inability of a device, equipment, or system to perform without degradation in the presence of an electromagnetic disturbance.NOTEÑSusceptibility is a lack of immunity.b3.1.15 equipment grounding conductor: The conductor used to connect the noncurrent-carrying parts of conduits, raceways, and equipment enclosures to the grounded conductor (neutral) and the grounding elec-trode at the service equipment (main panel) or secondary of a separately derived system (e.g., isolation transformer). See Section 100 in ANSI/NFPA 70-1993 [B2].3.1.16 failure mode: The effect by which failure is observed.a3.1.17 ßicker: Impression of unsteadiness of visual sensation induced by a light stimulus whose luminance or spectral distribution fluctuates with time.b3.1.18 frequency deviation: An increase or decrease in the power frequency. The duration of a frequency deviation can be from several cycles to several hours.c Syn.: power frequency variation.3.1.19 fundamental (component): The component of an order 1 (50 or 60 Hz) of the Fourier series of a periodic quantity.b3IEEEStd 1159-1995IEEE RECOMMENDED PRACTICE FOR 3.1.20 ground: A conducting connection, whether intentional or accidental, by which an electric circuit or piece of equipment is connected to the earth, or to some conducting body of relatively large extent that serves in place of the earth.NOTEÑ It is used for establishing and maintaining the potential of the earth (or of the conducting body) or approxi-mately that potential, on conductors connected to it, and for conducting ground currents to and from earth (or the con-ducting body).a3.1.21 ground loop: In a radial grounding system, an undesired conducting path between two conductive bodies that are already connected to a common (single-point) ground.3.1.22 harmonic (component): A component of order greater than one of the Fourier series of a periodic quantity.b3.1.23 harmonic content: The quantity obtained by subtracting the fundamental component from an alter-nating quantity.a3.1.24 immunity (to a disturbance): The ability of a device, equipment, or system to perform without deg-radation in the presence of an electromagnetic disturbance.b3.1.25 impulse: A pulse that, for a given application, approximates a unit pulse.b When used in relation to the monitoring of power quality, it is preferred to use the term impulsive transient in place of impulse.3.1.26 impulsive transient: A sudden nonpower frequency change in the steady-state condition of voltage or current that is unidirectional in polarity (primarily either positive or negative).3.1.27 instantaneous: A time range from 0.5Ð30 cycles of the power frequency when used to quantify the duration of a short duration variation as a modifier.3.1.28 interharmonic (component): A frequency component of a periodic quantity that is not an integer multiple of the frequency at which the supply system is designed to operate operating (e.g., 50 Hz or 60 Hz).3.1.29 interruption, momentary (power quality monitoring): A type of short duration variation. The complete loss of voltage (< 0.1 pu) on one or more phase conductors for a time period between 0.5 cycles and 3 s.3.1.30 interruption, sustained (electric power systems): Any interruption not classified as a momentary interruption.3.1.31 interruption, temporary (power quality monitoring):A type of short duration variation. The com-plete loss of voltage (< 0.1 pu) on one or more phase conductors for a time period between 3 s and 1 min.3.1.32 isolated ground: An insulated equipment grounding conductor run in the same conduit or raceway as the supply conductors. This conductor may be insulated from the metallic raceway and all ground points throughout its length. It originates at an isolated ground-type receptacle or equipment input terminal block and terminates at the point where neutral and ground are bonded at the power source. See Section 250-74, Exception #4 and Exception in Section 250-75 in ANSI/NFPA 70-1993 [B2].3.1.33 isolation: Separation of one section of a system from undesired influences of other sections.c3.1.34 long duration voltage variation:See: voltage variation, long duration.3.1.35 momentary (power quality monitoring): A time range at the power frequency from 30 cycles to 3 s when used to quantify the duration of a short duration variation as a modifier.4IEEE MONITORING ELECTRIC POWER QUALITY Std 1159-1995 3.1.36 momentary interruption:See: interruption, momentary.3.1.37 noise: Unwanted electrical signals which produce undesirable effects in the circuits of the control systems in which they occur.a (For this document, control systems is intended to include sensitive electronic equipment in total or in part.)3.1.38 nominal voltage (Vn): A nominal value assigned to a circuit or system for the purpose of conve-niently designating its voltage class (as 120/208208/120, 480/277, 600).d3.1.39 nonlinear load: Steady-state electrical load that draws current discontinuously or whose impedance varies throughout the cycle of the input ac voltage waveform.c3.1.40 normal mode voltage: A voltage that appears between or among active circuit conductors, but not between the grounding conductor and the active circuit conductors.3.1.41 notch: A switching (or other) disturbance of the normal power voltage waveform, lasting less than 0.5 cycles, which is initially of opposite polarity than the waveform and is thus subtracted from the normal waveform in terms of the peak value of the disturbance voltage. This includes complete loss of voltage for up to 0.5 cycles [B13].3.1.42 oscillatory transient: A sudden, nonpower frequency change in the steady-state condition of voltage or current that includes both positive or negative polarity value.3.1.43 overvoltage: When used to describe a specific type of long duration variation, refers to a measured voltage having a value greater than the nominal voltage for a period of time greater than 1 min. Typical val-ues are 1.1Ð1.2 pu.3.1.44 phase shift: The displacement in time of one waveform relative to another of the same frequency and harmonic content.c3.1.45 potential transformer (PT): An instrument transformer intended to have its primary winding con-nected in shunt with a power-supply circuit, the voltage of which is to be measured or controlled. Syn.: volt-age transformer.a3.1.46 power disturbance: Any deviation from the nominal value (or from some selected thresholds based on load tolerance) of the input ac power characteristics.c3.1.47 power quality: The concept of powering and grounding sensitive equipment in a manner that is suit-able to the operation of that equipment.cNOTEÑWithin the industry, alternate definitions or interpretations of power quality have been used, reflecting different points of view. Therefore, this definition might not be exclusive, pending development of a broader consensus.3.1.48 precision: Freedom from random error.3.1.49 pulse: An abrupt variation of short duration of a physical an electrical quantity followed by a rapid return to the initial value.3.1.50 random error: Error that is not repeatable, i.e., noise or sensitivity to changing environmental factors. NOTEÑFor most measurements, the random error is small compared to the instrument tolerance.3.1.51 sag: A decrease to between 0.1 and 0.9 pu in rms voltage or current at the power frequency for dura-tions of 0.5 cycle to 1 min. Typical values are 0.1 to 0.9 pu.b See: dip.IEEEStd 1159-1995IEEE RECOMMENDED PRACTICE FOR NOTEÑTo give a numerical value to a sag, the recommended usage is Òa sag to 20%,Ó which means that the line volt-age is reduced down to 20% of the normal value, not reduced by 20%. Using the preposition ÒofÓ (as in Òa sag of 20%,Óor implied by Òa 20% sagÓ) is deprecated.3.1.52 shield: A conductive sheath (usually metallic) normally applied to instrumentation cables, over the insulation of a conductor or conductors, for the purpose of providing means to reduce coupling between the conductors so shielded and other conductors that may be susceptible to, or that may be generating unwanted electrostatic or electromagnetic fields (noise).c3.1.53 shielding: The use of a conducting and/or ferromagnetic barrier between a potentially disturbing noise source and sensitive circuitry. Shields are used to protect cables (data and power) and electronic cir-cuits. They may be in the form of metal barriers, enclosures, or wrappings around source circuits and receiv-ing circuits.c3.1.54 short duration voltage variation:See: voltage variation, short duration.3.1.55 slew rate: Rate of change of ac voltage, expressed in volts per second a quantity such as volts, fre-quency, or temperature.a3.1.56 sustained: When used to quantify the duration of a voltage interruption, refers to the time frame asso-ciated with a long duration variation (i.e., greater than 1 min).3.1.57 swell: An increase in rms voltage or current at the power frequency for durations from 0.5 cycles to 1 min. Typical values are 1.1Ð1.8 pu.3.1.58 systematic error: The portion of error that is repeatable, i.e., zero error, gain or scale error, and lin-earity error.3.1.59 temporary interruption:See: interruption, temporary.3.1.60 tolerance: The allowable variation from a nominal value.3.1.61 total harmonic distortion disturbance level: The level of a given electromagnetic disturbance caused by the superposition of the emission of all pieces of equipment in a given system.b The ratio of the rms of the harmonic content to the rms value of the fundamental quantity, expressed as a percent of the fun-damental [B13].a Syn.: distortion factor.3.1.62 traceability: Ability to compare a calibration device to a standard of even higher accuracy. That stan-dard is compared to another, until eventually a comparison is made to a national standards laboratory. This process is referred to as a chain of traceability.3.1.63 transient: Pertaining to or designating a phenomenon or a quantity that varies between two consecu-tive steady states during a time interval that is short compared to the time scale of interest. A transient can be a unidirectional impulse of either polarity or a damped oscillatory wave with the first peak occurring in either polarity.b3.1.64 undervoltage: A measured voltage having a value less than the nominal voltage for a period of time greater than 1 min when used to describe a specific type of long duration variation, refers to. Typical values are 0.8Ð0.9 pu.3.1.65 voltage change: A variation of the rms or peak value of a voltage between two consecutive levels sustained for definite but unspecified durations.d3.1.66 voltage dip:See: sag.IEEE MONITORING ELECTRIC POWER QUALITY Std 1159-1995 3.1.67 voltage distortion: Any deviation from the nominal sine wave form of the ac line voltage.3.1.68 voltage ßuctuation: A series of voltage changes or a cyclical variation of the voltage envelope.d3.1.69 voltage imbalance (unbalance), polyphase systems: The maximum deviation among the three phases from the average three-phase voltage divided by the average three-phase voltage. The ratio of the neg-ative or zero sequence component to the positive sequence component, usually expressed as a percentage.a3.1.70 voltage interruption: Disappearance of the supply voltage on one or more phases. Usually qualified by an additional term indicating the duration of the interruption (e.g., momentary, temporary, or sustained).3.1.71 voltage regulation: The degree of control or stability of the rms voltage at the load. Often specified in relation to other parameters, such as input-voltage changes, load changes, or temperature changes.c3.1.72 voltage variation, long duration: A variation of the rms value of the voltage from nominal voltage for a time greater than 1 min. Usually further described using a modifier indicating the magnitude of a volt-age variation (e.g., undervoltage, overvoltage, or voltage interruption).3.1.73 voltage variation, short duration: A variation of the rms value of the voltage from nominal voltage for a time greater than 0.5 cycles of the power frequency but less than or equal to 1 minute. Usually further described using a modifier indicating the magnitude of a voltage variation (e.g. sag, swell, or interruption) and possibly a modifier indicating the duration of the variation (e.g., instantaneous, momentary, or temporary).3.1.74 waveform distortion: A steady-state deviation from an ideal sine wave of power frequency princi-pally characterized by the spectral content of the deviation [B13].3.2 Avoided termsThe following terms have a varied history of usage, and some may have speciÞc deÞnitions for other appli-cations. It is an objective of this recommended practice that the following ambiguous words not be used in relation to the measurement of power quality phenomena:blackout frequency shiftblink glitchbrownout (see 4.4.3.2)interruption (when not further qualiÞed)bump outage (see 4.4.3.3)clean ground power surgeclean power raw powercomputer grade ground raw utility powercounterpoise ground shared grounddedicated ground spikedirty ground subcycle outagesdirty power surge (see 4.4.1)wink。

Moisturization and skin barrier functionABSTRACT:Over the past decade,great progress has been made toward elucidating the structure and function of the stratum corneum (SC),the outermost layer of the epidermis. SC cells (corneocytes)protect against desiccation and environmental by the SC is largely dependent on several factors。

First, intercellular lamellar lipids, organized predominantly in an orthorhombic gel phase, provide an effective barrier to the passage of water through the tissue。

Secondly,the diffusion path length also retards water loss,since water must traverse the tortuous path created by the SC layers and corneocyte envelopes. Thirdly,and equally important, is natural moisturizing factor (NMF), a complex mixture of low-molecular—weight,water-soluble compounds first formed within thee corneocytes by degradation of the histidine—rich protein known as filaggrin. Each maturation step leading to the formation of an effective moisture barrier-including corneocyte strengthening, lipid processing,and NMF generation-is influenced by the level of SC hydration. These processes,as well as the final step of corneodesmolysis that mediates exfoliations, are often disturbed upon environmental challenge, resulting in dry, flaky skin conditions. The present paper reviews our current understanding of the biology of the SC, particularly its homeostatic mechanisms of hydration。

904N.E.Huang and others10.Discussion98711.Conclusions991References993 A new method for analysing has been devel-oped.The key part of the methodany complicated data set can be decomposed intoof‘intrinsic mode functions’Hilbert trans-This decomposition method is adaptive,and,highly efficient.Sinceapplicable to nonlinear and non-stationary processes.With the Hilbert transform,Examplesthe classical nonlinear equation systems and dataare given to demonstrate the power new method.data are especially interesting,for serve to illustrate the roles thenonlinear and non-stationary effects in the energy–frequency–time distribution.Keywords:non-stationary time series;nonlinear differential equations;frequency–time spectrum;Hilbert spectral analysis;intrinsic time scale;empirical mode decomposition1.Introductionsensed by us;data analysis serves two purposes:determine the parameters needed to construct the necessary model,and to confirm the model we constructed to represent the phe-nomenon.Unfortunately,the data,whether from physical measurements or numerical modelling,most likely will have one or more of the following problems:(a)the total data span is too short;(b)the data are non-stationary;and(c)the data represent nonlinear processes.Although each of the above problems can be real by itself,the first two are related,for a data section shorter than the longest time scale of a sta-tionary process can appear to be non-stationary.Facing such data,we have limited options to use in the analysis.Historically,Fourier spectral analysis has provided a general method for examin-the data analysis has been applied to all kinds of data.Although the Fourier transform is valid under extremely general conditions(see,for example,Titchmarsh1948),there are some crucial restrictions of Proc.R.Soc.Lond.A(1998)Nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis905the Fourier spectral analysis:the system must be linear;and the data must be strict-ly periodic or stationary;otherwise,the resulting spectrum will make little physicalsense.to the Fourier spectral analysis methods.Therefore,behoves us review the definitions of stationarity here.According to the traditional definition,a time series,X (t ),is stationary in the wide sense,if,for all t ,E (|X (t )2|)<∞,E (X (t))=m,C (X (t 1),X (t 2))=C (X (t 1+τ),X (t 2+τ))=C (t 1−t 2),(1.1)in whichE (·)is the expected value defined as the ensemble average of the quantity,and C (·)is the covariance function.Stationarity in the wide sense is also known as weak stationarity,covariance stationarity or second-order stationarity (see,forexample,Brockwell &Davis 1991).A time series,X (t ),is strictly stationary,if the joint distribution of [X (t 1),X (t 2),...,X (t n )]and [X (t 1+τ),X (t 2+τ),...,X (t n +τ)](1.2)are the same for all t i and τ.Thus,a strictly stationaryprocess with finite second moments is alsoweakly stationary,but the inverse is not true.Both definitions arerigorous but idealized.Other less rigorous definitions have also beenused;for example,that is stationary within a limited timespan,asymptotically stationary is for any random variableis stationary when τin equations (1.1)or (1.2)approaches infinity.In practice,we can only have data for finite time spans;these defini-tions,we haveto makeapproximations.Few of the data sets,from either natural phenomena or artificial sources,can satisfy these definitions.It may be argued thatthe difficulty of invoking stationarity as well as ergodicity is not on principlebut on practicality:we just cannot have enough data to cover all possible points in thephase plane;therefore,most of the cases facing us are transient in nature.This is the reality;we are forced to face it.Fourier spectral analysis also requires linearity.can be approximated by linear systems,the tendency tobe nonlinear whenever their variations become finite Compounding these complications is the imperfection of or numerical schemes;theinteractionsof the imperfect probes even with a perfect linear systemcan make the final data nonlinear.For the above the available data are ally of finite duration,non-stationary and from systems that are frequently nonlinear,either intrinsicallyor through interactions with the imperfect probes or numerical schemes.Under these conditions,Fourier spectral analysis is of limited use.For lack of alternatives,however,Fourier spectral analysis is still used to process such data.The uncritical use of Fourier spectral analysis the insouciant adoption of the stationary and linear assumptions may give cy range.a delta function will giveProc.R.Soc.Lond.A (1998)906N.E.Huang and othersa phase-locked wide white Fourier spectrum.Here,added to the data in the time domain,Constrained bythese spurious harmonics the wide frequency spectrum cannot faithfully represent the true energy density in the frequency space.More seri-ously,the Fourier representation also requires the existence of negative light intensity so that the components can cancel out one another to give thefinal delta function. Thus,the Fourier components might make mathematical sense,but do not really make physical sense at all.Although no physical process can be represented exactly by a delta function,some data such as the near-field strong earthquake records areFourier spectra.Second,tions;wave-profiles.Such deformations,later,are the direct consequence of nonlinear effects.Whenever the form of the data deviates from a pure sine or cosine function,the Fourier spectrum will contain harmonics.As explained above, both non-stationarity and nonlinearity can induce spurious harmonic components that cause energy spreading.The consequence is the misleading energy–frequency distribution forIn this paper,modemode functions The decomposition is based on the direct extraction of theevent on the time the frequency The decomposition be viewed as an expansion of the data in terms of the IMFs.Then,based on and derived from the data,can serve as the basis of that expansion linear or nonlinear as dictated by the data,Most important of all,it is adaptive.As will locality and adaptivity are the necessary conditions for the basis for expanding nonlinear and non-stationary time orthogonality is not a necessary criterionselection for a nonlinearon the physical time scaleslocal energy and the instantaneous frequencyHilbert transform can give us a full energy–frequency–time distribution of the data. Such a representation is designated as the Hilbert spectrum;it would be ideal for nonlinear and non-stationary data analysis.We have obtained good results and new insights by applying the combination of the EMD and Hilbert spectral analysis methods to various data:from the numerical results of the classical nonlinear equation systems to data representing natural phe-nomena.The classical nonlinear systems serve to illustrate the roles played by the nonlinear effects in the energy–frequency–time distribution.With the low degrees of freedom,they can train our eyes for more complicated cases.Some limitations of this method will also be discussed and the conclusions presented.Before introducing the new method,we willfirst review the present available data analysis methods for non-stationary processes.Proc.R.Soc.Lond.A(1998)Nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis9072.Review of non-stationary data processing methodsWe willfirstgivea brief survey of themethodsstationary data.are limited to linear systems any method is almost strictly determined according to the special field in which the application is made.The available methods are reviewed as follows.(a )The spectrogramnothing but a limited time window-width Fourier spectral analysis.the a distribution.Since it relies on the tradition-al Fourier spectral analysis,one has to assume the data to be piecewise stationary.This assumption is not always justified in non-stationary data.Even if the data are piecewise stationary how can we guarantee that the window size adopted always coincides with the stationary time scales?What can we learn about the variations longer than the local stationary time scale?Will the collection of the locally station-ary pieces constitute some longer period phenomena?Furthermore,there are also practical difficulties in applying the method:in order to localize an event in time,the window width must be narrow,but,on the other hand,the frequency resolu-tion requires longer time series.These conflicting requirements render this method of limited usage.It is,however,extremely easy to implement with the fast Fourier transform;thus,ithas attracted a wide following.Most applications of this methodare for qualitative display of speech pattern analysis (see,for example,Oppenheim &Schafer 1989).(b )The wavelet analysisThe wavelet approach is essentially an adjustable window Fourier spectral analysiswith the following general definition:W (a,b ;X,ψ)=|a |−1/2∞−∞X (t )ψ∗ t −b ad t,(2.1)in whichψ∗(·)is the basic wavelet function that satisfies certain very general condi-tions,a is the dilation factor and b is the translationof theorigin.Although time andfrequency do not appear explicitly in the transformed result,the variable 1/a givesthe frequency scale and b ,the temporal location of an event.An intuitive physical explanation of equation (2.1)is very simple:W (a,b ;X,ψ)is the ‘energy’of X ofscale a at t =b .Because of this basic form of at +b involvedin thetransformation,it is also knownas affinewavelet analysis.For specific applications,the basic wavelet function,ψ∗(·),can be modified according to special needs,but the form has to be given before the analysis.In most common applications,however,the Morlet wavelet is defined as Gaussian enveloped sine and cosine wave groups with 5.5waves (see,for example,Chan 1995).Generally,ψ∗(·)is not orthogonalfordifferent a for continuous wavelets.Although one can make the wavelet orthogonal by selecting a discrete set of a ,thisdiscrete wavelet analysis will miss physical signals having scale different from theselected discrete set of a .Continuous or discrete,the wavelet analysis is basically a linear analysis.A very appealing feature of the wavelet analysis is that it provides aProc.R.Soc.Lond.A (1998)908N.E.Huang and othersuniform resolution for all the scales.Limited by the size of thebasic wavelet function,the downside of the uniform resolution is uniformly poor resolution.Although wavelet analysis has been available only in the last ten years or so,it hasbecome extremelypopular.Indeed,it is very useful in analysing data with gradualfrequency changes.Since it has an analytic form for the result,it has attracted extensive attention of the applied mathematicians.Most of its applications have been in edge detection and image compression.Limited applications have also been made to the time–frequency distribution in time series (see,for example,Farge 1992;Long et al .1993)andtwo-dimensionalimages (Spedding et al .1993).Versatile as the wavelet analysis is,the problem with the most commonly usedMorlet wavelet is its leakage generated by the limited length of the basic wavelet function,whichmakesthe quantitativedefinitionof the energy–frequency–time dis-tribution difficult.Sometimes,the interpretation of the wavelet can also be counter-intuitive.For example,to define a change occurring locally,one must look for theresult in the high-frequencyrange,for the higher the frequency the more localized thebasic wavelet will be.If a local event occurs only in the low-frequency range,one willstill be forced to look for its effects inthe high-frequencyrange.Such interpretationwill be difficultif it is possible at all (see,for example,Huang et al .1996).Another difficulty of the wavelet analysis is its non-adaptive nature.Once the basic waveletis selected,one will have to use it to analyse all the data.Since the most commonlyused Morlet wavelet is Fourier based,it also suffers the many shortcomings of Fouri-er spectral analysis:it can only give a physically meaningful interpretation to linear phenomena;it can resolve the interwave frequency modulation provided the frequen-cy variationis gradual,but it cannot resolve the intrawave frequency modulation because the basic wavelet has a length of 5.5waves.Inspite of all these problems,wavelet analysisisstillthe bestavailable non-stationary data analysis method so far;therefore,we will use it in this paper as a reference to establish the validity and thecalibration of the Hilbert spectrum.(c )The Wigner–Ville distributionThe Wigner–Ville distribution is sometimes alsoreferred toas the Heisenberg wavelet.By definition,it is the Fourier transform of the central covariance function.For any time series,X (t ),we can define the central variance as C c (τ,t )=X (t −12τ)X ∗(t +12τ).(2.2)Then the Wigner–Ville distribution is V (ω,t )=∞−∞C c (τ,t )e −i ωτd τ.(2.3)This transform has been treated extensively by Claasen &Mecklenbr¨a uker (1980a ,b,c )and by Cohen (1995).It has been extremely popular with the electrical engi-neering community.The difficulty with this method is the severe cross terms as indicated by the exis-tence of negativepowerfor some frequency ranges.Although this shortcoming canbe eliminated by using the Kernel method (see,for example,Cohen 1995),the resultis,then,basically that of a windowed Fourier analysis;therefore,itsuffers all thelim-itations of the Fourier analysis.An extension of this method has been made by Yen(1994),who used the Wigner–Ville distribution to define wave packets that reduce Proc.R.Soc.Lond.A (1998)Nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis909 a complicated data set to afinite number of simple components.This extension is very powerful and can be applied to a variety of problems.The applications to complicated data,however,require a great amount of judgement.(d)Evolutionary spectrumThe evolutionary spectrum wasfirst proposed by Priestley(1965).The basic idea is to extend the classic Fourier spectral analysis to a more generalized basis:from sine or cosine to a family of orthogonal functions{φ(ω,t)}indexed by time,t,and defined for all realω,the frequency.Then,any real random variable,X(t),can beexpressed asX(t)= ∞−∞φ(ω,t)d A(ω,t),(2.4)in which d A(ω,t),the Stieltjes function for the amplitude,is related to the spectrum asE(|d A(ω,t)|2)=dµ(ω,t)=S(ω,t)dω,(2.5) whereµ(ω,t)is the spectrum,and S(ω,t)is the spectral density at a specific time t,also designated as the evolutionary spectrum.If for eachfixedω,φ(ω,t)has a Fourier transformφ(ω,t)=a(ω,t)e iΩ(ω)t,(2.6) then the function of a(ω,t)is the envelope ofφ(ω,t),andΩ(ω)is the frequency.If, further,we can treatΩ(ω)as a single valued function ofω,thenφ(ω,t)=α(ω,t)e iωt.(2.7) Thus,the original data can be expanded in a family of amplitude modulated trigono-metric functions.The evolutionary spectral analysis is very popular in the earthquake communi-ty(see,for example,Liu1970,1971,1973;Lin&Cai1995).The difficulty of its application is tofind a method to define the basis,{φ(ω,t)}.In principle,for this method to work,the basis has to be defined a posteriori.So far,no systematic way has been offered;therefore,constructing an evolutionary spectrum from the given data is impossible.As a result,in the earthquake community,the applications of this method have changed the problem from data analysis to data simulation:an evo-lutionary spectrum will be assumed,then the signal will be reconstituted based on the assumed spectrum.Although there is some general resemblance to the simulated earthquake signal with the real data,it is not the data that generated the spectrum. Consequently,evolutionary spectrum analysis has never been very useful.As will be shown,the EMD can replace the evolutionary spectrum with a truly adaptive representation for the non-stationary processes.(e)The empirical orthogonal function expansion(EOF)The empirical orthogonal function expansion(EOF)is also known as the principal component analysis,or singular value decomposition method.The essence of EOF is briefly summarized as follows:for any real z(x,t),the EOF will reduce it toz(x,t)=n1a k(t)f k(x),(2.8)Proc.R.Soc.Lond.A(1998)910N.E.Huang and othersin whichf j·f k=δjk.(2.9)The orthonormal basis,{f k},is the collection of the empirical eigenfunctions defined byC·f k=λk f k,(2.10)where C is the sum of the inner products of the variable.EOF represents a radical departure from all the above methods,for the expansion basis is derived from the data;therefore,it is a posteriori,and highly efficient.The criticalflaw of EOF is that it only gives a distribution of the variance in the modes defined by{f k},but this distribution by itself does not suggest scales or frequency content of the signal.Although it is tempting to interpret each mode as indepen-dent variations,this interpretation should be viewed with great care,for the EOF decomposition is not unique.A single component out of a non-unique decomposition, even if the basis is orthogonal,does not usually contain physical meaning.Recently, Vautard&Ghil(1989)proposed the singular spectral analysis method,which is the Fourier transform of the EOF.Here again,we have to be sure that each EOF com-ponent is stationary,otherwise the Fourier spectral analysis will make little sense on the EOF components.Unfortunately,there is no guarantee that EOF compo-nents from a nonlinear and non-stationary data set will all be linear and stationary. Consequently,singular spectral analysis is not a real improvement.Because of its adaptive nature,however,the EOF method has been very popular,especially in the oceanography and meteorology communities(see,for example,Simpson1991).(f)Other miscellaneous methodsOther than the above methods,there are also some miscellaneous methods such as least square estimation of the trend,smoothing by moving averaging,and differencing to generate stationary data.Methods like these,though useful,are too specialized to be of general use.They will not be discussed any further here.Additional details can be found in many standard data processing books(see,for example,Brockwell &Davis1991).All the above methods are designed to modify the global representation of the Fourier analysis,but they all failed in one way or the other.Having reviewed the methods,we can summarize the necessary conditions for the basis to represent a nonlinear and non-stationary time series:(a)complete;(b)orthogonal;(c)local;and (d)adaptive.Thefirst condition guarantees the degree of precision of the expansion;the second condition guarantees positivity of energy and avoids leakage.They are the standard requirements for all the linear expansion methods.For nonlinear expansions,the orthogonality condition needs to be modified.The details will be discussed later.But even these basic conditions are not satisfied by some of the above mentioned meth-ods.The additional conditions are particular to the nonlinear and non-stationary data.The requirement for locality is the most crucial for non-stationarity,for in such data there is no time scale;therefore,all events have to be identified by the time of their occurences.Consequently,we require both the amplitude(or energy) and the frequency to be functions of time.The requirement for adaptivity is also crucial for both nonlinear and non-stationary data,for only by adapting to the local variations of the data can the decomposition fully account for the underlying physics Proc.R.Soc.Lond.A(1998)Nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis911of the processes and not just to fulfil the mathematical requirements for fitting the data.This is especially important for the nonlinear phenomena,for a manifestation of nonlinearity is the ‘harmonic distortion’in the Fourier analysis.The degree of distortion depends on the severity of nonlinearity;therefore,one cannot expect a predetermined basis to fit all the phenomena.An easy way to generate the necessary adaptive basis is to derive the basis from the data.In this paper,we will introduce a general method which requires two steps in analysing the data as follows.The first step is to preprocess the data by the empirical mode decomposition method,with which the data are decomposed into a number of intrinsic mode function components.Thus,we will expand the data in a basis derived from the data.The second step is to apply the Hilbert transform to the decomposed IMFs and construct the energy–frequency–time distribution,designated as the Hilbert spectrum,from which the time localities of events will be preserved.In other words,weneed the instantaneous frequency and energy rather than the global frequency and energy defined by the Fourier spectral analysis.Therefore,before goingany further,we have to clarify the definition of the instantaneous frequency.3.Instantaneous frequencyis to accepting it only for special ‘monocomponent’signals 1992;Cohen 1995).Thereare two basicdifficulties with accepting the idea of an instantaneous fre-quency as follows.The first one arises from the influence of theFourier spectral analysis.In the traditional Fourier analysis,the frequency is defined for thesineor cosine function spanning the whole data length with constant ampli-tude.As an extension of this definition,the instantaneous frequencies also have torelate to either a sine or a cosine function.Thus,we need at least one full oscillationof a sineor a cosine wave to define the local frequency value.According to this logic,nothing full wave will do.Such a definition would not make sense forThe secondarises from the non-unique way in defining the instantaneousfrequency.Nevertheless,this difficulty is no longer serious since the introduction ofthe meanstomakethedata analyticalthrough the Hilbert transform.Difficulties,however,still exist as ‘paradoxes’discussed by Cohen (1995).For an arbitrary timeseries,X (t ),we can always have its Hilbert Transform,Y (t ),as Y (t )=1πP∞−∞X (t )t −t d t,(3.1)where P indicates the Cauchy principal value.This transformexists forallfunctionsof class L p(see,for example,Titchmarsh 1948).With this definition,X (t )and Y (t )form the complex conjugate pair,so we can have an analytic signal,Z (t ),as Z (t )=X (t )+i Y (t )=a (t )e i θ(t ),(3.2)in which a (t )=[X 2(t )+Y 2(t )]1/2,θ(t )=arctanY (t )X (t ).(3.3)Proc.R.Soc.Lond.A (1998)912N.E.Huang andothers Theoretically,there are infinitely many ways of defining the imaginary part,but the Hilbert transform provides a unique way of defining the imaginary part so that the result is ananalyticfunction.A brief tutorial on the Hilbert transform with theemphasis on its physical interpretation can be found in Bendat &Piersol is the bestlocal fitan amplitude and phase varying trigonometric function to X (t ).Even with the Hilbert transform,there is still controversy in defining the instantaneous frequency as ω=d θ(t )d t .(3.4)This leads Cohen (1995)to introduce the term,‘monocomponent function’.In prin-ciple,some limitations on the data are necessary,forthe instantaneous frequencygiven in equation (3.4)is a single value function of time.At any given time,thereis only one frequency value;therefore,it can only represent one component,hence ‘monocomponent’.Unfortunately,no cleardefinition of the ‘monocomponent’signalwas given to judge whether a function is or is not ‘monocomponent’.For lack ofa precise definition,‘narrow band’was adopted a on the data for the instantaneous frequency to make sense (Schwartz et al .1966).There are two definitions for bandwidth.The first one is used in the study of the probability properties of the signalsand waves,wherethe processes are assumed tobe stationary and Gaussian.Then,the bandwidth can be defined in spectral moments The expected number of zero crossings per unit time is given byN 0=1π m 2m 0 1/2,(3.5)while the expected number of extrema per unit time is given byN 1=1π m 4m 2 1/2,(3.6)in which m i is the i th moment of the spectrum.Therefore,the parameter,ν,definedas N 21−N 20=1π2m 4m 0−m 22m 2m 0=1π2ν2,(3.7)offers a standard bandwidth measure (see,for example,Rice 1944a,b ,1945a,b ;Longuet-Higgins 1957).For a narrow band signal ν=0,the expected numbers extrema and zero crossings have to equal.the spectrum,but in a different way.coordinates as z (t )=a (t )e i θ(t ),(3.8)with both a (t )and θ(t )being functions of time.If this function has a spectrum,S (ω),then the mean frequency is given byω = ω|S (ω)|2d ω,(3.9)Proc.R.Soc.Lond.A (1998)Nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis913which can be expressed in another way asω =z ∗(t )1i dd tz (t )d t=˙θ(t )−i ˙a (t )a (t )a 2(t )d t =˙θ(t )a 2(t )d t.(3.10)Based on this expression,Cohen (1995)suggested that ˙θbe treated as the instanta-neous frequency.With these notations,the bandwidth can be defined asν2=(ω− ω )2 ω 2=1 ω 2(ω− ω )2|S (ω)|2d ω=1 ω 2z ∗(t ) 1i d d t− ω 2z (t )d t =1 ω 2 ˙a 2(t )d t +(˙θ(t )− ω )2a 2(t )d t .(3.11)For a narrow band signal,this value has to be small,then both a and θhave to begradually varying functions.Unfortunately,both equations (3.7)and (3.11)defined the bandwidth in the global sense;they are both overly restrictive and lack preci-sion at the same time.Consequently,the bandwidth limitation on the Hilbert trans-form to give a meaningful instantaneous frequency has never been firmly established.For example,Melville (1983)had faithfully filtered the data within the bandwidth requirement,but he still obtained many non-physical negative frequency values.It should be mentioned here that using filtering to obtain a narrow band signal is unsat-isfactory for another reason:the filtered data have already been contaminated by the spurious harmonics caused by the nonlinearity and non-stationarity as discussed in the introduction.In order to obtain meaningful instantaneous frequency,restrictive conditions have to be imposed on the data as discussed by Gabor (1946),Bedrosian (1963)and,more recently,Boashash (1992):for any function to have a meaningful instantaneous frequency,the real part of its Fourier transform has to have only positive frequency.This restriction can be proven mathematically as shown in Titchmarsh (1948)but it is still global.For data analysis,we have to translate this requirement into physically implementable steps to develop a simple method for applications.For this purpose,we have to modify the restriction condition from a global one to a local one,and the basis has to satisfy the necessary conditions listed in the last section.Let us consider some simple examples to illustrate these restrictions physically,by examining the function,x (t )=sin t.(3.12)Its Hilbert transform is simply cos t .The phase plot of x –y is a simple circle of unit radius as in figure 1a .The phase function is a straight line as shown in figure 1b and the instantaneous frequency,shown in figure 1c ,is a constant as expected.If we move the mean offby an amount α,say,then,x (t )=α+sin t.(3.13)Proc.R.Soc.Lond.A (1998)。

海州湾方氏云鳚体长与体重分布特征及其关系栾静;徐宾铎;薛莹;任一平;张崇良【摘要】体长、体重是鱼类种群的基本生物学特征,能够反映鱼类个体生理状态以及所处环境条件的变化,但在实际研究中其时空变化往往被忽略.本文根据2011—2016年春、秋季海州湾8个航次的渔业资源底拖网调查数据,研究了方氏云鳚(Pholis fangi)的体长组成、体重组成,体长–体重关系和肥满度特征,并分析了上述指标的时空异质性.结果表明,海州湾方氏云鳚的群体有多个年龄组,体长、体重和体长–体重关系参数a、b及肥满度在时空上均有较大波动,且在年间差异显著.秋季各航次平均体长、体重呈现逐年增大趋势;肥满度的季节差异要大于年间差异,春季肥满度小于秋季;体长和肥满度在海州湾分布均是西南部大于东北部,但秋季肥满度分布则与此相反.调查的方氏云鳚群体基本符合正异速生长类型.体长体重特征的时空异质性可能与气候、摄食强度、性成熟比例与捕捞压力等有关,并在一定程度上反映了渔业生态系统和栖息地特征.相关研究应充分考虑体长、体重关系参数的时空变化,以为渔业资源评估提供精确参数.%Body size is a basic biological characteristic in fish populations and can reflect individual physiology as well as changing environment conditions. Slight variabilities in some biological parameters may result in complex ecological effects, and affect food web link intensity in trophic cascades. However, the spatial and temporal het-erogeneity of size composition within populations have often been ignored in many studies of fish biology. We use Fang's gunnel (Pholis fangi) in Haizhou Bay as an example for studying the variability of body size on an annual scale. P. fangi is a low trophic fish and plays an important role in the food web and ecosystem of the Yellow Sea, withincreasing dominance in Haizhou Bay. We collected annual bottom trawl surveys in Haizhou Bay in the spring and fall from 2011 to 2016. We used a range of statistical methods, included variable coefficient, covariance analysis, two-sample t-test, and Pearson correlation analysis to study the population size composition, length-weight relationship, and relative fatness of P. fangi in this area. We analyzed the annual and seasonal vari-ability as well as the spatial distribution of body length and relative body mass. The results showed that P. fangi had multiple age structure in Haizhou Bay. Their length frequency distributions were multi-modal and skewed, with the majority of captured individuals aged 2-3 years. Statistical analysis indicated that there were remarkable temporal and spatial variations in the average size and the parameters of body length-weight relationship of P. fangi, with significant differences across years (P<0.05). The average body length and relative fatness tended to be higher during autumn surveys than spring surveys. Variation in relative fatness was greater between seasons than among years. In spring, the spatial distribution of body length and relative fatness was larger in the southwest area than the northeast area of the bay. A t-test on the body length-weight relationship showed that the allometric growth patterns of P. fangi were generally positive. Correlation analyses between benthic water temperature and the length-weight relationship showed that temperature had a substantial influence on the relative fatness, body length-weight relationship, and mean body length. The spatiotemporal variability of fish size and other parameters may be attributed to their feeding intensity,maturation, fishing pressure, and environmental and habit variation, and is also likely to reflect changes in the fishery ecosystem. We suggest that the spatiotemporal variability of population size composition should be fully considered in fisheries resource management, as these basic parame-ters can contribute significantly to fishery ecosystem modelling and management strategy evaluation.【期刊名称】《中国水产科学》【年(卷),期】2017(024)006【总页数】9页(P1323-1331)【关键词】方氏云鳚;体长分布;体重分布;体长–体重关系;肥满度;时空异质性【作者】栾静;徐宾铎;薛莹;任一平;张崇良【作者单位】中国海洋大学水产学院, 山东青岛 266003;中国海洋大学水产学院, 山东青岛 266003;中国海洋大学水产学院, 山东青岛 266003;中国海洋大学水产学院, 山东青岛 266003;青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室海洋渔业科学与食物产出过程功能实验室, 山东青岛 266003;中国海洋大学水产学院, 山东青岛 266003【正文语种】中文【中图分类】S93海州湾是位于黄海中部的沿岸开放型海湾,海域初级生产力较高, 是很多鱼类和无脊椎动物的产卵场和索饵场[1–2]。