英语本科段自学考试英汉翻译教程Unit 7 Literature.doc

- 格式:doc

- 大小:39.00 KB

- 文档页数:5

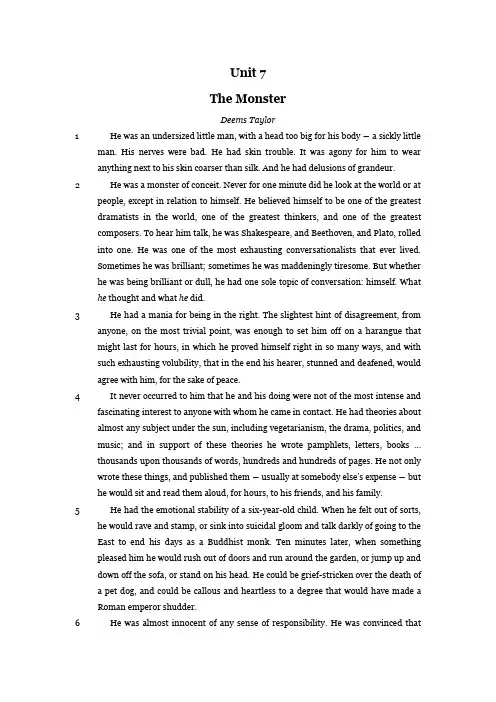

Unit 7The MonsterDeems Taylor1He was an undersized little man, with a head too big for his body ― a sickly little man. His nerves were bad. He had skin trouble. It was agony for him to wear anything next to his skin coarser than silk. And he had delusions of grandeur.2He was a monster of conceit. Never for one minute did he look at the world or at people, except in relation to himself. He believed himself to be one of the greatest dramatists in the world, one of the greatest thinkers, and one of the greatest composers. To hear him talk, he was Shakespeare, and Beethoven, and Plato, rolled into one. He was one of the most exhausting conversationalists that ever lived.Sometimes he was brilliant; sometimes he was maddeningly tiresome. But whether he was being brilliant or dull, he had one sole topic of conversation: himself. What he thought and what he did.3He had a mania for being in the right. The slightest hint of disagreement, from anyone, on the most trivial point, was enough to set him off on a harangue that might last for hours, in which he proved himself right in so many ways, and with such exhausting volubility, that in the end his hearer, stunned and deafened, would agree with him, for the sake of peace.4It never occurred to him that he and his doing were not of the most intense and fascinating interest to anyone with whom he came in contact. He had theories about almost any subject under the sun, including vegetarianism, the drama, politics, and music; and in support of these theories he wrote pamphlets, letters, books ...thousands upon thousands of words, hundreds and hundreds of pages. He not only wrote these things, and published them ― usually at somebody else’s expense ― but he would sit and read them aloud, for hours, to his friends, and his family.5He had the emotional stability of a six-year-old child. When he felt out of sorts, he would rave and stamp, or sink into suicidal gloom and talk darkly of going to the East to end his days as a Buddhist monk. Ten minutes later, when something pleased him he would rush out of doors and run around the garden, or jump up and down off the sofa, or stand on his head. He could be grief-stricken over the death ofa pet dog, and could be callous and heartless to a degree that would have made aRoman emperor shudder.6He was almost innocent of any sense of responsibility. He was convinced thatthe world owed him a living. In support of this belief, he borrowed money from everybody who was good for a loan ― men, women, friends, or strange rs. He wrote begging letters by the score, sometimes groveling without shame, at others loftily offering his intended benefactor the privilege of contributing to his support, and being mortally offended if the recipient declined the honor.7What money he could lay his hand on he spent like an Indian rajah. No one will ever know ― certainly he never knows ― how much money he owed. We do know that his greatest benefactor gave him $6,000 to pay the most pressing of his debts in one city, and a year later had to give him $16,000 to enable him to live in another city without being thrown into jail for debt.8He was equally unscrupulous in other ways. An endless procession of women marched through his life. His first wife spent twenty years enduring and forgiving his infidelities. His second wife had been the wife of his most devoted friend and admirer, from whom he stole her. And even while he was trying to persuade her to leave her first husband he was writing to a friend to inquire whether he could suggest some wealthy woman ― any wealthy woman ― whom he could marry for her money.9He had a genius for making enemies. He would insult a man who disagreed with him about the weather. He would pull endless wires in order to meet some man who admired his work and was able and anxious to be of use to him ― and would proceed to make a mortal enemy of him with some idiotic and wholly uncalled-for exhibition of arrogance and bad manners. A character in one of his operas was a caricature of one of the most powerful music critics of his day. Not content with burlesquing him, he invited the critic to his house and read him the libretto aloud in front of his friends.10The name of this monster was Richard Wagner. Everything I have said about him you can find on record ― in newspapers, in police reports, in the testimony of people who knew him, in his own letters, between the lines of his autobiography.And the curious thing about this record is that it doesn’t matter in the least.11Because this undersized, sickly, disagreeable, fascinating little man was right all the time, the joke was on us. He was one of the world’s greatest dramatists; he was a great thinker; he was one of the most stupendous musical geniuses that, up to now, the world has ever seen. The world did owe him a living. What if he did talk about himself all the time? If he talked about himself for twenty-four hours every day for the span of his life he would not have uttered half the number of words that othermen have spoken and written about him since his death.12When you consider what he wrote ― thirteen operas and music dramas, eleven of them still holding the stage, eight of them unquestionably worth ranking among the world’s great musico-dramatic masterpieces ― when you listen to what he wrote, the debts and heartaches that people had to endure from him don’t seem much of a price.13What if he was faithless to his friends and to his wives? He had one mistress to whom he was faithful to the day of his death: Music. Not for a single moment did he ever compromise with what he believed, with what he dreamed. There is not a line of his music that could have been conceived by a little mind. Even when he is dull, or downright bad, he is dull in the grand manner. Listening to his music, one does not forgive him for what he may or may not have been. It is not a matter of forgiveness. It is a matter of being dumb with wonder that his poor brain and body didn’t burst under the torment of the demon of creative energy that lived inside him, struggling, clawing, scratching to be released; tearing, shrieking at him to write the music that was in him. The miracle is that what he did in the little space of seventy years could have been done at all, even by a great genius. Is it any wonder he had no time to be a man?畸人迪姆斯·泰勒1 他是个大头小身体、病怏怏的矬子;成日神经兮兮,皮肤也有毛病。

典范英语7全部翻译引言:典范英语7是一本广泛使用的英语教材,为学习者提供了丰富多样的英语学习资源。

本文将为读者提供典范英语7课文的全部翻译,帮助读者更好地理解和掌握每篇课文的内容。

第一篇:《战争的起因》战争从哪里来?人类是否可以避免战争?让我们从历史中寻找答案。

战争的起因可以追溯到不同国家之间的矛盾和冲突。

对于很多人来说,战争通常是因为利益、领土争端或者意识形态的不同而引发的。

然而,是否可以通过谈判、对话或者其他和平手段来解决这些问题,一直是一个备受争议的问题。

第二篇:《文化遗产》每个国家都有自己独特的文化遗产,这些文化遗产反映了一个国家的历史、传统和价值观。

保护和传承文化遗产对于维护一个国家的独立性和多样性至关重要。

然而,由于现代化的发展和全球化的影响,许多国家的文化遗产正面临着被遗忘和失去的风险。

因此,我们需要共同努力,保护并传承我们宝贵而独特的文化遗产。

第三篇:《科技的影响》科技的发展已经对我们的生活产生了深远的影响。

从早期的工业革命到今天的信息技术革命,科技不仅改变了我们的生活方式,还改变了我们与世界的互动方式。

然而,科技发展也带来了许多问题和挑战。

例如,人们越来越依赖科技,失去了与他人面对面交流的机会。

在利用科技的同时,我们也需要注意保持适度和平衡,以避免科技对我们生活的负面影响。

第四篇:《环境保护》环境保护是当今全球关注的焦点之一。

随着人口的增长和工业的发展,环境问题变得越来越严重。

气候变化、土地退化和水污染等问题已经对我们的生活产生了巨大的影响。

因此,保护环境变得至关重要。

我们需要采取一系列的举措,如减少碳排放、节约能源和推动可持续发展,以实现环境的保护和可持续发展。

第五篇:《健康生活》健康是我们生活中最重要的财富之一。

保持健康的生活方式对于我们的身心健康非常重要。

饮食健康、适度运动、充足的睡眠和压力管理都是保持健康的重要方面。

此外,我们还需要关注心理健康,保持积极乐观的心态。

通过保持健康的生活方式,我们可以更好地享受生活,并更好地应对生活中的各种挑战。

Unit 7Text A Families搭配:1.descend from 从什么传下来的/动词词组2.think of…as… 把什么看作是/动词词组3.far away from 远离/副词词组4.feeling of belongings 归属感/名词词组5.with the change 随着变化/介词词组6.care for 照顾/动词词组7.split up 裂变,离婚/动词词组8.talk of 谈及/动词词组语言点:1.Having a family simply means having children. (前一个动词的ing形式放在means这个谓语动词前是动名词作主语;后一个动词ing形式放在means 这个谓语动词后是动名词作宾语)2.No matter+(if, whether, how, what, when, who, where, which等连词)+句子。

表示无论……3.Every family has a sense of what a family is.4.industry(n.工业)-industrial(adj.工业的)-industrialize(v.使工业化)5.increase(增长)这个动词经常用在进行时态中。

6.Most single parents find it very difficult to take care of a family alone,so they soon marry again and form remarried families.(形式宾语句型:主语+谓语+it+n./adj.+to do +其他)Text B The Changing American Family搭配:1.be important to sb. 对某人很重要/动词词组2.provide for 为谁提供什么/动词词组3.be expected to do sth. 应该做某事/动词词组4.take care of 照顾/动词词组5.work for pay 为了赚钱而工作/动词词组6.be (not) considered to be/do sth. 被认为是什么,做什么/动词词组7.make decisions about sth./doing sth. 做什么决定/动词词组8.working wife 工作的妻子/名词词组9.help sb. with sth. 帮助某人什么/动词词组10.in contrast 与此相反/副词词组11.get ready for 为什么做好准备/动词词组12.be busy with sth./be busy (in) doing sth. 忙于做某事/动词词组13.in conclusion 最后/副词词组14.bring changes to sb/sth…… 给某人带来了变化/动词词组语言点:1.similar(adj.相似的)-similarly(adv.相似地)——similarity(n.相似)2.may have done sth. 对过去发生的事情进行推断 e.g. She may have been married. 她有可能已经结婚了。

Unit 1 英国人和美国人的空间概念人们说英国人和美国人是被同一种语言分离开的两个伟大的民族。

英美民族之间的差异使得英语本身受到很多指责,然而,这些差异也许不应该过分归咎于语言,而应该更多的归因于其他层面上的交流:从使很多美国人感到做作的英式语音语调到以自我为中心的处理时间、空间和物品的不同方法。

如果说这世上有两种文化间的空间关系学的具体容迥然不同,那就是在有教养(私立学校)的英国人和中产阶级的美国人之间了。

造成这种巨大差异的一个基本原因是在美国人们借助空间大小来对人或事加以分类,而在英国决定你身分的却是社会等级制度。

在美国,你的住址可以很好的暗示你的身分(这不仅适用于你的家庭住址,也适用于你的商业地址)。

住在纽波特和棕榈滩的人要比布鲁克林和迈阿密的人高贵时髦得多。

格林尼治和科德角与纽华克和迈阿密简直毫无类似之处。

座落在麦迪逊大道和花园大道的公司要比那些座落在第七大道和第八大道的公司更有情调。

街角办公室要比电梯旁或者长廊尽头的办公室更受尊敬。

而英国人是在社会等级制度下出生和成长的。

无论你在哪里看到他,他仍然是贵族,即便是在鱼贩摊位的柜台后面。

除了阶级差异,英国人和我们美国人在如何分配空间上也存在差异。

在美国长大的中产阶级美国人觉得自己有权拥有自己的房间,或者至少房间的一部分。

当我让我的美国研究对象画出自己理想的房间或办公室时,他们毫无例外的只画了自己的空间,而没有画其他人的地方。

当我要求他们画出他们现有的房间或办公室时,他们只画出他们共享房间里自己的那部分,然后在中间画一条分隔线。

无论是男性还是女性研究对象,都把厨房和主卧划归母亲或妻子的名下,而父亲的领地则是书房或休息室,如果有的话;要不然就是工场,地下室,或者有时仅仅是一工作台或者是车库。

美国女性如果想独处,可以走进卧室、关上门。

关闭的门是“不要打扰”或“我很生气”的标志。

如果一个美国人家里或办公室的房门是开着的,则说明他现在有空。

在这样的暗示下,人们不会认为他想把自己关闭起来,而会认为他正处于一种随时响应他人的准备就绪的状态中。

Culture is activity of thought, and receptiveness to beauty and humane feeling. Scraps of information have nothing to do with it. A merely well-informed man is the most useless bore on God’s earth. What we should aim at producing is men who possess both culture and expert knowledge in some special direction. Their expert knowledge will give them the ground to start from, and their culture will lead them as deep as philosophy and as high as art. We have to remember that the valuable intellectual development is self-development, and that it mostly takes place between the ages of sixteen and thirty. As to training, the most important part is given by mothers before the age of twelve. A saying due to Archbishop Temple illustrates my meaning. Surprise was expressed at the success in after-life of a man, who as a boy at Rugby had been somewhat undistin-guished. He answered, “It is not what they are at eighteen, it is what they become afterwards that matters.”In training a child to activity of thought, above all things we must beware of what I will call “inert ideas”—that is to say, ideas that are merely received into the mind without being utilised, or tested, or thrown into fresh combinations.In the history of education, the most striking phenomenon is that schools of learning, which at one epoch are alive with a ferment of genius, in a succeeding generation exhibit merely pedantry and routine. The reason is, that they are overladen with inert ideas. Education with inert ideas is not only useless: it is, above all things, harmful—Corruptio optimi, pessima. Except at rare intervals of intellectual ferment, education in the past has been radically infected with inert ideas. That is the reason why uneducated clever women, who have seen much of the world, are in middle life so much the most cultured part of the community. They have been saved from this horrible burden of inert ideas. Every intellectual revolution which has ever stirred humanity into greatness has been a passionate protest against inert ideas. Then, alas, with pathetic ignorance of human psychology, it has proceeded by some educational scheme to bind humanity afresh with inert ideas of its own fashioning.Let us now ask how in our system of education we are to guard against this mental dry rot. We enuncia te two educational commandments, “Do not teach too many subjects,” and again, “What you teach, teach thoroughly.”The result of teaching small parts of a large number of subjects is the passive reception of disconnected ideas, not illumined with any spark of vitality. Let the main ideas which are introduced into a child’s education be few and important, and let them be thrown into every combination possible. The child should make them his own, and should understand their application here and now in the circumstances of his actual life. From thevery beginning of his education, the child should experience the joy of discovery. The discovery which he has to make, is that general ideas give an understanding of that stream of events which pours through his life, which is his life. By understanding I mean more than a mere logical analysis, though that is included. I mean “understanding’ in the sense in which it is used in the French proverb, “To understand all, is to forgive all.” Pedants sneer at an education which is useful. But if education is not useful, what is it? Is it a talent, to be hidden away in a napkin? Of course, education should be useful, whatever your aim in life. It was useful to Saint Augustine and it was useful to Napoleon. It is useful, because understanding is useful.I pass lightly over that understanding which should be given by the literary side of education. Nor do I wish to be supposed to pronounce on the relative merits of a classical or a modern curriculum. I would only remark that the understanding which we want is an understanding of an insistent present. The only use of a knowledge of the past is to equip us for the present. No more deadly harm can be done to young minds than by depreciation of the present. The present contains all that there is. It is holy ground; for it is the past, and it is the future. At the same time it must be observed that an age is no less past if it existed two hundred years ago than if it existed two thousand years ago. Do not be deceived by the pedantry of dates. The ages of Shakespeare and of Molière are no less past than are the ages of Sophocles and of Virgil. The communion of saints is a great and inspiring assemblage, but it has only one possible hall of meeting, and that is, the present, and the mere lapse of time through which any particular group of saints must travel to reach that meeting-place, makes very little difference.Passing now to the scientific and logical side of education, we remember that here also ideas which are not utilised are positively harmful. By utilising an idea, I mean relating it to that stream, compounded of sense perceptions, feelings, hopes, desires, and of mental activities adjusting thought to thought, which forms our life. I can imagine a set of beings which might fortify their souls by passively reviewing disconnected ideas. Humanity is not built that way except perhaps some editors of newspapers.In scientific training, the first thing to do with an idea is to prove it. But allow me for one moment to extend the meaning of “prove”; I mean—to prove its worth. Now an idea is not worth much unless the propositions in which it is embodied are true. Accordingly an essential part of the proof of an idea is the proof, either by experiment or by logic, of the truth of the propositions. But it is not essential that this proof of the truth should constitute the first introduction to the idea. After all, its assertion by the authority of respectable teachers is sufficient evidence to begin with. Inour first contact with a set of propositions, we commence by appreciating their importance. That is what we all do in after-life. We do not attempt, in the strict sense, to prove or to disprove anything, unless its importance makes it worthy of that honour. These two processes of proof, in the narrow sense, and of appreciation, do not require a rigid separation in time. Both can be proceeded with nearly concurrently. But in so far as either process must have the priority, it should be that of appreciation by use.Furthermore, we should not endeavour to use propositions in isolation. Emphatically I do not mean, a neat little set of experiments to illustrate Proposition I and then the proof of Proposition I, a neat little set of experiments to illustrate Proposition II and then the proof of Proposition II, and so on to the end of the book. Nothing could be more boring. Interrelated truths are utilised en bloc, and the various propositions are employed in any order, and with any reiteration. Choose some important applications of your theoretical subject; and study them concurrently with the systematic theoretical exposition. Keep the theoretical exposition short and simple, but let it be strict and rigid so far as it goes. It should not be too long for it to be easily known with thoroughness and accuracy. The consequences of a plethora of half-digested theoretical knowledge are deplorable. Also the theory should not be muddled up with the practice. The child should have no doubt when it is proving and when it is utilising. My point is that what is proved should be utilised, and that what is utilised should—so far, as is practicable—be proved. I am far from asserting that proof and utilisation are the same thing.。

Unit 10 SpeechesLesson 28(E—C)Speech by President Nixon of the United States at Welcoming Banquet21 February 1972Mr. Prime Minister and all of your distinguished guests this evening,On behalf of all your American guests, I wish to thank you for the incomparable hospitality for which the Chinese people are justly famous throughout the world. I particularly want to pay tribute,not only to those who prepared the magnificent dinner, but also to those who have provided the splendid music. Never have I heard American music played better in a foreign land.Mr. Prime Minister, I wish to thank you for your very gracious and eloquent remarks. At this vry moment through the wonder of relecommunications, more people are seeing and hearing what we say than on any other such occasion in the whole history of the world. Yet, what we say here will not be long remembered. What we do here can change the world.As you said in your toast, the Chinese people are a great people, the American people are a great people. If our two people are enemies the future of this world we share together is dark indeed. But if we can find common ground to work together, the chance for world peace is immeasurably increased.In the spirit of frankness which I hope will characterize our talks this week, let us recognize at the outset these points: we have at times in the past been enemies. We have great differences today. What brings us together is that we have common interests which transcend those differences. As we discuss our differences, neither of us will compromise our principles. But while we cannot close the gulf between us, we can try to bridge it so that we may be able to tald across it.译文:美国总统尼克松在欢迎宴会上的讲话1972年2月21日总理先生,今天晚上在座的诸位贵宾:我谨代表你们的所有美国客人向你们表示感谢,感谢你们的无可比拟的盛情款待。

Unit One English and American Concepts of Space Edward T. Hall英国人和美国人的空间概念人们说英国人和美国人是被同一种语言分离开的两个伟大的民族。

英美民族之间的差异使得英语本身受到很多指责,然而,这些差异也许不应该过分归咎于语言,而应该更多的归因于其他层面上的交流:从使很多美国人感到做作的英式语音语调到以自我为中心的处理时间、空间和物品的不同方法。

如果说这世上有两种文化间的空间关系学的具体内容迥然不同,那就是在有教养(私立学校)的英国人和中产阶级的美国人之间了。

造成这种巨大差异的一个基本原因是在美国人们借助空间大小来对人或事加以分类,而在英国决定你身分的却是社会等级制度。

在美国,你的住址可以很好的暗示你的身分(这不仅适用于你的家庭住址,也适用于你的商业地址)。

住在纽波特和棕榈滩的人要比布鲁克林和迈阿密的人高贵时髦得多。

格林尼治和科德角与纽华克和迈阿密简直毫无类似之处。

座落在麦迪逊大道和花园大道的公司要比那些座落在第七大道和第八大道的公司更有情调。

街角办公室要比电梯旁或者长廊尽头的办公室更受尊敬。

而英国人是在社会等级制度下出生和成长的。

无论你在哪里看到他,他仍然是贵族,即便是在鱼贩摊位的柜台后面。

除了阶级差异,英国人和我们美国人在如何分配空间上也存在差异。

在美国长大的中产阶级美国人觉得自己有权拥有自己的房间,或者至少房间的一部分。

当我让我的美国研究对象画出自己理想的房间或办公室时,他们毫无例外的只画了自己的空间,而没有画其他人的地方。

当我要求他们画出他们现有的房间或办公室时,他们只画出他们共享房间里自己的那部分,然后在中间画一条分隔线。

无论是男性还是女性研究对象,都把厨房和主卧划归母亲或妻子的名下,而父亲的领地则是书房或休息室,如果有的话;要不然就是工场,地下室,或者有时仅仅是一张工作台或者是车库。

美国女性如果想独处,可以走进卧室、关上门。

Unit7WhenLightningStruck课文翻译综合教程一Unit 7 When Lightning StruckI was in the tiny bathroom in the back of the plane when I felt the slamming jolt, and then the horrible swerve that threw me against the door. Oh, Lord, I thought, this is it! Somehow I managed to unbolt the door and scramble out. The flight attendants, already strapped in, waved wildly for me to sit down. As I lunged toward my seat, passengers looked up at me with the stricken expressions of creatures who know they are about to die."I think we got hit by lightning," the girl in the seat next to mine said. She was from a small town in east Texas, and this was only her second time on an airplane. She had won a trip to England by competing in a high school geography bee and was supposed to make a connecting flight when we landed in Newark.In the next seat, at the window, sat a young businessman who had been confidently working. Now he looked worried. And that really worries me—when confident-looking businessmen look worried. The laptop was put away. "Something's not right," he said.The pilot's voice came over the speaker. I heard vaguely through my fear, "Engine number two ... emergency landing ... New Orleans." When he was done, the voice of a flight attendant came on, reminding us of the emergency procedures she had reviewed before takeoff. Of course I never paid attention to this drill, always figuring that if we ever got to the point where we needed to use life jackets, I would have already died of terror.Now we began a roller-coaster ride through the thunderclouds. I was ready to faint, but when I saw the face ofthe girl next to me, I pulled myself together, I reached for her hand and reassured her that we were going to make it, "What a story you're going to tell when you get home!" I said. "After this, London's going to seem like small potatoes."I wondered where I was getting my strength. Then I saw that my other hand was tightly held by a ringed hand. Someone was comforting me—a glamorous young woman across the aisle, the female equivalent of the confident businessman. She must have seen how scared I was and reached over."I tell you," she confided, "the problems I brought up on this plane with me sure don't seem real big right now." I loved her Southern drawl, her indiscriminate use of perfume, and her soulful squeezes. I was sure that even if I survived the plane crash, I'd have a couple of broken fingers from all the TLC. "Are you okay?" she kept asking me.Among the many feelings going through my head during those excruciating 20 minutes was pride—pride in how well everybody on board was behaving. No one panicked. No one screamed. As we jolted and screeched our way downward, I could hear small pockets of soothing conversation everywhere.I thought of something I had heard a friend say about the wonderful gift his dying father had given the family: he had died peacefully, as if not to alarm any of them about an experience they would all have to go through someday.And then—yes!—we landed safely. Outside on the ground, attendants and officials were waiting to transfer us to alternative flights. But we passengers clung together. We chatted about the lives we now felt blessed to be living, as difficult or rocky as they might be. The young businessman lamented that he had not achance to buy his two little girls a present. An older woman offered him her box of expensive Lindt chocolates, still untouched, tied with a lovely bow. "I shouldn't be eating them anyhow," she said. My glamorous aisle mate took out her cell phone and passed it around to anyone who wanted to make a call to hear the reassuring voice of a loved one.There was someone I wanted to call. Back in Vermont, my husband, Bill, was anticipating my arrival late that night. He had been complaining that he wasn't getting to see very much of me because of my book tour. I had planned to surprise him by getting in a few hours early. Now I just wanted him to know I was okay and on my way.When my name was finally called to board my new flight, I felt almost tearful to be parting from the people whose lives had so intensely, if briefly, touched mine.Even now, back on terra firma, walking down a Vermont road, I sometimes hear an airplane and look up at that small, glinting piece of metal. I remember the passengers on that fateful, lucky flight and wish I could thank them for the many acts of kindness I witnessed and received. I am indebted to my fellow passengers and wish I could pay them back.But then, remembering my aisle mate's hand clutching mine while I clutched the hand of the high school student, I feel struck by lightning all over again: the point is not to pay back kindness but to pass it on.闪电来袭当我感到猛烈摇晃时我正在飞机尾部的小卫生间。

别再使唤我简介:从文章的标题中我们可以看出Stacey Wilkins的愤怒。

如同许多在美国的学生一样,她在一家餐馆当服务员以此来偿还学生贷款。

在这篇文章中,她将告诉我们,是什么人和什么事件使得她如此气愤。

我刚刚坐了一个半小时等待某乡村网球俱乐部的家伙们吃完他们的披萨。

他们是在餐厅关闭15分钟之后来的,因为他们不想削减他们网球比赛的时间,餐厅所有者同意了他们的请求并把烤箱重新打开给他们做披萨,可是厨师早就回家了。

在我给他们解释餐厅已经关闭后,这些顾客对于要求我服务丝毫没有觉得不妥,他们毫无顾忌地在那里坐着详细讲述他们网球比赛的精彩部分,直到11点(餐厅9点半就关门了),更重要的是,他们毫无顾忌地让我成为了他们网球后的残忍小比赛的受害者。

骚扰可怜的服务生多么好玩啊!“天哪,在这里像这样坐着简直太棒了。

”一个男人说道,在没有得到任何回复后,他继续说道:“服务员,我猜你想让我们离开。

”我已经快要在怒气之中爆发了,“我不准备回答你的评论。

”我说着,然后走开。

他准备开始一场战斗,红旗已经在飘扬。

这个男人走近我,问我要甜点。

作为一个老顾客,他之前从没要过甜点。

你知道的,这是90年代所谓的“低脂”潮流。

但那晚他享受这样的权利,他觉得自己很强大,而我觉得自己被侵犯了。

接受了3美元20美分之后,我回家了。

他们的小费是我为这场精神强奸付出的代价。

开车时,眼泪从我的脸上滑落,我为什么在哭?我之前也被骚扰过,10年的服务员生涯本应该让我对这种情况变得无动于衷,但,这是一个转折点:十年侮辱的最终结果。

我现在处于一个爆发点上,我不能忍受作为一个公众的情绪发泄包,人们似乎认为侮辱服务员是被包含在餐费里的,所有的正派和礼貌都放在了挂在门上的外套里。

他们认为自己的地位远高于我的,他们是国王,而我是农夫。

我宁愿他们成为农夫。

在美国,我是餐厅义务服务的极力倡导者。

连干两班活将是对压迫者的最好的教训,让他们上酒菜,让他们打扫在孩子玩耍后的战场,以及让他们在某个10个人的聚会占了他们的桌子三个小时后只给了一点点小费而变得沮丧。

新标准英语综合教程4unit7课文全文翻译新标准大学英语综合教程4教师用书unit7课文翻译Unit7Translation of the passagesActive reading (1)美好的回忆虽然这个房子已经换了许多户人家了,但直到现在我还记得那些筑墙、盖屋顶的工人。

当时马路对过那座庄园大宅的主人需要建一个小屋给他的园丁住。

他在这片连绵不断的巨大的丘陵果园中找到了一片空地,他派工人到本地的采石场运来金黄色的石头,工人花了三个月时间在园子里建起了这两座农家小屋。

我只从侧面看到过我的旁边的那座房子,我从来没有见过它的正面。

但是我知道,尽管我们在结构和外观上是一摸一样的,我们的朝向正好相反,这真是不可思议。

我的前门朝东,隔壁房子的前门是朝西的。

我的卧室在房子的后部,在隔壁那所房子里,这个位置正好是厨房的上面。

我的厨房在房子的前部,在隔壁的那个房子里,这个位置是在卧室的下方。

我觉得我比它幸运,因为每天早上,我这边的石头会在阳光的照耀下熠熠发光。

园丁精心地照料庄园周围的果园和花园,所以到了秋天,树上总是果实累累,结满了苹果和梨。

当白天越来越短的时候,这四周的土地上是一片忙碌的景象,帮工们采摘水果,把摘下的水果送到庄园去或是沿着那条路运到镇上的市场去卖。

除了秋天,其他时候这里非常安静。

园丁的生活好像很孤独,后来有一天,他带了一个年轻女子回家。

我这个房子里顿时充满了欢声笑语和饭菜的香味。

园丁外出干活的时候,他的妻子会照看我周围的花园,种玫瑰、水仙和郁金香,还有夏季植物和菊花。

从早春的鲜花到深秋的深深的金黄色叶子,花园里真是五彩缤纷。

能照看这样一对夫妇,我感觉很幸福。

没过多久,又有孩子要照看了。

头一个孩子是女孩,她常常高兴得咯咯笑,睡得也很沉。

后来又添了一个男孩,他哭起来嗓门很大,让我们大家都不得安宁。

但是他们都很快乐,也很听话。

他们会静静地在屋里或花园里一起玩耍。

渐渐地,他们长大了,也长高了。

最让我感到愉快的一个记忆是:在一个温暖的夏日,我看到男孩高高地坐在苹果树的枝干上,读着他最喜爱的那本书。

Unit7课文翻译课文ASurviving an economic crisis经济危机中求生存1.许许多多的人正经历的这场经济萧条发端于美国。

对抵押贷款监管不力,致使当时的风险评估远低于现在的最终结果。

由于大量的房产所有人无法偿还贷款,负责监管的公司、放贷的公司(以及其子公司及股份持有者)都损失了大笔的金钱。

这些巨额亏损的后果很快就影响到美国就业市场,造成下岗或解雇。

经济复兴迟迟不来。

许多人几个月来都是苦苦挣扎,正如下面故事中的主人公那样。

2.苏•约翰逊有好几个月都未付房租了,面临着被逐出的境地,她把能塞进她的那辆双门轿车的东西都打包收拾好,离城而去。

3.她最后在一家汽车旅馆落脚,交付了260美元的定金,这还是她设法从朋友那儿以及卖掉家具后凑齐的,是苏在失业救济金被终止后所有的余钱。

她面临流浪生活,这在以前是难以想象的,而她不久以前都还在大都市里一家公司供职,并就读于商学院研究生班。

4.苏明白自己最终很可能以车为家。

她如今已成为倒霉的失业群体中的一份子,他们自称“99周人”,因为他们已经领完至多9周的失业保险救济金。

5.根据劳动统计局的数据,长期失业率已达到创纪录的水平。

些许的失业救济金对那些失去工作的人来说可是救命钱,这使他们不至于形貌落魄,无立锥之地;不至于无钱加油,缴不起电费话费。

6.一旦收不到失业救济支票,哪怕是像苏这样曾经贵为技术公司客服经理的人,也会日益跌入经济窘迫的深渊;原有工薪阶层或中产阶级的最后一抹荣光也已消逝不在,所有人都前途未卜。

7.当苏收到最后一笔失业救济支票时,阵阵悲凉涌上心头。

由于没有收入进账,苏的活期账户余额转为负值。

汽车行将被收回!而且信贷公司不断骚扰,催还车贷,让她成天压力倍增。

每天,苏就像乒乓球一样在信心和绝望之间起落不定。

8.生活境遇真是令人痛心地一落千丈!想想仅在短短的一年半之前,苏在原有工作岗位上可挣到56,00美元的年薪,可在像墨西哥、加勒比那样的地方度假,还就读于名校商学院。

Unit 7 Letter to a B StudentYour final grade for the course is B. A respectable grade. Far superior to the "Gentleman's C" that served as the norm a couple of generations ago. But in those days A's were rare: only two out of twenty-five, as I recall. Whatever our norm is, it has shifted upward, with the result that you are probably disappointed at not doing better. I'm certain that nothing I can say will remove that feeling of disappointment, particularly in a climate where grades determine eligibility for graduate school and special programs.Disappointment. It's the stuff bad dreams are made of: dreams of failure, inadequacy, loss of position and good repute. The essence of success is that there's never enough of it to go round in a zero-sum game where one person's winning must be offset by another's losing, one person's joy offset by another's disappointment. You've grown up in a society where winning is not the most important thing—it's the only thing. To lose, to fail, to go under, to go broke—these are deadly sins in a world where prosperity in the present is seen as a sure sign of salvation in the future. In a different society, your disappointment might be something you could shrug away. But not in ours.My purpose in writing you is to put your disappointment in perspective by considering exactly what your grade means and doesn't mean. I do not propose to argue here that grades are unimportant. Rather, I hope to show you that your grade, taken at face value, is apt to be dangerously misleading, both to you and to others. As a symbol on your college transcript, your grade simply means that you have successfully completed a specific course of study, doing so at a certain level of proficiency. The level of your proficiency has been determined by your performance of rather conventional tasks: taking tests, writing papers and reports, and so forth. Your performance is generally assumed to correspond to the knowledge you have acquired and will retain. But this assumption, as we both know, is questionable; it may well be that you've actually gotten much more out of the course than your grade indicates—or less. Lacking more precise measurement tools, we must interpret your B as a rather fuzzy symbol at best, representing a questionable judgment of your mastery of the subject.Your grade does not represent a judgment of your basic ability or of your character. Courage, kindness, wisdom, good humor—these are the important characteristics of our species. Unfortunately they are not part of our curriculum. But they are important: crucially so, because they are always in short supply. Ifyou value these characteristics in yourself, you will be valued—and far more so than those whose identities are measured only by little marks on a piece of paper. Your B is a price tag on a garment that is quite separate from the living, breathing human being underneath.The student as performer; the student as human being. The distinction is one we should always keep in mind. I first learned it years ago when I got out of the service and went back to college. There were a lot of us then: older than the norm, in a hurry to get our degrees and move on, impatient with the tests and rituals of academic life. Not an easy group to handle.One instructor handled us very wisely, it seems to me. On Sunday evenings in particular, he would make a point of stopping in at a local bar frequented by many of the GI-Bill students. There he would sit and drink, joke, and swap stories with men in his class, men who had but recently put away their uniforms and identities: former platoon sergeants, bomber pilots, corporals, captains, lieutenants, commanders, majors—even a lieutenant colonel, as I recall. They enjoyed his company greatly, as he theirs. The next morning he would walk into class and give these same men a test. A hard test. A test on which he usually flunked about half of them. Oddly enough, the men whom he flunked did not resent it. Nor did they resent him for shifting suddenly from a friendly gear to a coercive one. Rather, they loved him, worked harder and harder at his course as the semester moved along, and ended up with a good grasp of his subject—economics. The technique is still rather difficult for me to explain; but I believe it can be described as one in which a clear distinction was made between the student as classroom performer and the student as human being. A good distinction to make. A distinction that should put your B in perspective—and your disappointment.Perspective. It is important to recognize that human beings, despite differences in class and educational labeling, are fundamentally hewn from the same material and knit together by common bonds of fear and joy, suffering and achievement. Warfare, sickness, disasters, public and private—these are the larger coordinates of life. To recognize them is to recognize that social labels are basically irrelevant and misleading. It is true that these labels are necessary in the functioning of a complex society as a way of letting us know who should be trusted to do what, with the result that we need to make distinctions on the basis of grades, degrees, rank, and responsibility. But these distinctions should never be taken seriously in human terms, either in the way we look at others or in the way we look at ourselves.Even in achievement terms, your B label does not mean that you are permanently defined as a B achievement person. I'm well aware that B students tend to get B's in the courses they take later on, just as A students tend to get A's. But academic work is a narrow, neatly defined highway compared to the unmapped rolling country you will encounter after you leave school. What you have learned may help you find your way about at first; later on you will have to shift to yourself, locating goals and opportunities in the same fog that hampers us all as we move toward the future.写给中等生的一封信你的期末成绩是一个B,一个过得去的等级。

Unit 7 Literature (2)Lesson 19(E—C)East of Eden(1)By John SteinbeckThe Salinas Valley is in Northern California. It is a long narrow swale betwwen two ranges of mountains, and the Salinas River winds and twists up the center until it falls at last into Monterey Bay.I remember my childhood names for grasses and secret flowers. I remember where a toad may live and what time the irds awaken in the summer—and what trees and seasons smelled like—how people looked and walked and smelled even. The memory of odors is very rich.I remember that the Gabilan Mountains to the east of the valley were light gay mountains full of sun and loveliness and a kind of invitation, so that you wanted to climb into their warm foothills almost as you want to climb into the lap of a beloved mother. They were beckoning mountains with a brown grass love. The Santa Lucias stood up against the sky to the west and kept the valley from the open sea, and they were dark and brooding—unfriendly and dangerous. I always found in myself a dread of west and a love of east. Where I ever got such an idea I cannot say, unless it could be that the morning came over the peaks of the Gabilans and the night drifted back from the ridges of the Santa Lucias. It may be that the birth and death of the day had some part in my feeling about the two ranges of mountains.From both sides of the valley little streams slpipped out of the hill canyons and fell into the bed of the Salinas River. In the winte of wet years the streams ran full-freshet, and they swelled the river until sometimes it raged and boiled, bank full, and then it was a destroyer. The river tore the edges of the farm lands and washed whole acres down; it toppled barns and houses into itself, to go floating and bobbing away. It trapped cows and pigs and sheep and drowned them in its muddy brown water and carried them to the sea. Then when the late spring came, the river drew in from its edges and the sand banks appeared. And in the summer the river didn’t run at all above ground. Some pools would be left in the deep swirl places under a high bank. The tules and grasses grew back, and willows straightened up with the flood debris in their upper branches. The Salinas was only a part-time river. The summer sun drove it underground. It was not a fine river at all, but it was the only one we had and so we boasted about it—how dangerous it was in a wet winter and how dry it was in a dry summer. You can boast about anything if it’s all you have. Maybe the less you have, the more you are required to boast.(from John Steinbeck, East of Eden, Chapter1)译文:萨利内斯河谷位于加利福民亚州北部。

那是两条山脉之间的一片狭长的洼地,萨利内斯河蜿蜒曲折从中间流过,最后注入蒙特雷海湾。

我记得儿时给各种小草和隐蔽的小花取的名字。

我记得蛤蟆喜欢在什么地方栖身,鸟雀夏天早晨什么时候醒来——我还记得树木和不同季节特有的气息——记得人们的容貌、走路的姿势、甚至身上的气味。

关于气味的记忆实在太多啦。

我记得河谷东面的加毕仑山脉总是阳光璀璨、明媚可爱,仿佛向你殷勤邀请,你不禁想爬上暖洋洋的山麓小丘,正像爬到亲爱的母亲怀里那样。

棕色的草坡给你爱抚,向你召唤。

西面的圣卢西亚斯山脉高耸入云,黑压压地挡在河谷和大海之间,显得不友好而危险。

我发现自己一直对西方怀有畏惧,而对东方怀有喜爱。

我说不出这种想法的根子在什么地方,也许是因为黎明从加比仑山顶升起,夜晚从圣卢西亚斯山脊压下来。

每一天的诞生和消亡也许使我对两条山脉产生了不同的感情。

洼地两面的小峡谷都有涧水流出,汇入萨利纳斯河床。

在多雨的年份,冬天水流充沛,引起河面暴涨,有时候汹涌翻腾,泛滥两岸,就成了祸害。

河水冲坏农田边级,毁掉大片大片的土地,使牲口棚和房屋坍塌,卷入洪流,漂浮而去。

牛、猪、羊走投无路,在黄褐色的泥水里眼睁睁地淹死,给带到海里。

春末时分,河面变窄,露出了沙岸。

到了夏天,地上河水完全断流。

只有原先岸高漩涡深的地方才留下几个水塘。

芦苇和茅草重新生长,柳树直起躯干,上部的枝桠还挂着洪水留下的枯枝败草。

它根本不是条了不起的河流,但是我们只有这么一条,因此便为它吹嘘。

如果你别无他有,你可以为任何东西吹嘘。

也许你有的东西越少,你就越要吹吹牛皮。

(选自王仲年译《伊甸之东》)Lesson 20 (E—C)The Sund of Music(Ecerpt 1)By Maria Augusta TrappSuddenly I heard quick footsteps behind me, and a full, resonant voice exchaimed: “I see you are looking at my flag.”There he was—the Captain!The tall, well-dressed gentleman standing before me was certainly a far cay from the old sea wolf of my imagination. His air of complete self-assurance and somewhat lordly bearing would have frightened me, had it not been for his warm and hearty hadndshake.“I am so glad you have come, Fraulein…”I filled in, “maria.”He took me in from topp to toe with a quick glance. All of a sudden I became very conscious of my funny dress, and sure enough, there I was diving under my helmet again. But the Captain’s eyes rested on my shoes.We were still standing in the hall when he said: “I want you to meet the children first of all.”Out of his pocket he took an odd-shaped, ornamented brass whistle, on which he piped a series of complicated trills.I must have looked highly amazed, because he said, a little apologeticall: “You see it taks so long to call so many children by name, that I’ve given them each a different whistle.”Of course, I now expected to hear a loud banging of doors and a chorus of giggles and shouts, the scampering feet of youngsters jumping down the steps and sliding down the banister. In stead, led by a sober-faced young girl in her arly teens, an almost solemn little procession descended step by step in well-mannered silence—four girls and two boys, all dressed in sailor suits. For and instant we stared at each other in utter amazement. I had never seen such perfect little ladies and gentlemen, and they had never seen such a helmet.“Here is our new teacher, Fraulein Maria.”“Gruss Gott, Fraulein Maria,” six voices echoed in unison. Six perfect bows followed.That wasn’t real. That couldn’t be true. I had to shove back that ridiculosu hat again. This push, bowerer, was the last. Down came the ugly brown thing, rolled on the shiny parquet floor,and landed at the tiny feet of a very pretty, plump little girl of about five. A delingted giggle cut through the severe silence. The ice was broken. We all laughed.(from Maria Augusta Trapp, The Sound of Music)参考译文:音乐之声(摘录1)玛丽亚·奥古斯塔·特拉普我突然听见身后有急促的脚步声,接着就听见一个非常宏亮的声音说道:“看来您是在看我的旗子哪!”这个人,就是舰长。