淋巴瘤药理药效研究动物模型共112页文档

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:10.41 MB

- 文档页数:112

肿瘤动物模型的建立可以:(1)评价抗肿瘤免疫治疗的疗效;(2)作为抗肿瘤药物筛选模型;(3)为肿瘤转移研究提供更好的研究平台;(4)为研发抗肿瘤转移性药物提供良好的实验工具。

实验方法:诱发性肿瘤动物模型实验方法原理:诱发性肿瘤动物模型是指研究者用化学致癌剂、放射线、致癌病毒诱发动物的肿瘤等。

实验材料:肿瘤细胞小鼠试剂、试剂盒、无血清培养基质、3%中性甲醇石腊仪器、耗材、低温离心机、血球计数器、游标卡尺实验步骤一、肝癌1.二乙基亚硝胺(DEN)诱发大白鼠肝癌(1)取体重250 g左右的封闭群大白鼠,雌雄不拘;(2)按性别分笼饲养。

除给普通食物外,饲以致癌物,即用0.25%DEN水溶液灌胃,剂量为10 mg/kg,每周一次,其余5天用0.025%DEN水溶液放入水瓶中,任其自由饮用;(3)共约4个月可诱发成肝癌;(4)也可以单用0.005%掺入饮水中口吸服8个月诱发肝癌。

2.4-2甲基氨基氮苯(DBA)诱发大鼠肝癌(1)用含0.06%DBA的饲料喂养大鼠,饲料中维生素B2不应超过1.5~2 mg/kg;(2)4~6月就有大量的肝癌诱发成功。

3.2-乙酰氨基酸(2AAF)诱发小鼠、狗、猫、鸡、兔肝癌(1)给成年大鼠含0.03% 2AAF标准饲料;(2)每日每平均2~3 mg 2AAF(也可将2AAF混于油中灌喂),3~4月后有80~90%动物产生肝肿瘤。

4.二乙基亚硝胺诱发大鼠肝癌:(1)用剂量为每日0.3~14 mg/kg体重,混于饲料或饮水中给予;(2)6~9个月后255/300大鼠发生了肝癌。

5.亚胺基偶氮甲苯(OAAT)诱发小鼠肝癌(1)用1%OAAF苯溶液(约0.1 ml含1 mg)涂在动物的两肩胛间皮肤上,隔日一次,每次2~3滴,一般涂100次。

(2)实验后7~8周即而出现第一个肝肿瘤,7个月以上可诱发小鼠肝肿瘤约55%。

(3)或用2.5 mg OAAT溶于葵瓜子油中,给C3H小鼠皮下注射4次,每日间隔10天,也可诱发成肝癌。

研究肿瘤动物实验报告

本报告旨在探讨肿瘤动物实验的研究成果和相关发现。

实验目的是通过对动物模型进行肿瘤实验,从而加深对肿瘤发展机制的理解,挖掘新的治疗方法和疗效评估指标。

实验设计中,我们选用了经典的小鼠肿瘤模型,并通过不同的实验组和对照组进行比较,以确保实验数据的准确性和可靠性。

在实验过程中,我们详细记录了动物模型的建立、肿瘤的发展和治疗干预等关键步骤的信息。

通过对肿瘤动物实验的观察和分析,我们发现了一系列关于肿瘤生长、转移和治疗等方面的重要发现。

首先,我们观察到肿瘤在小鼠体内呈现出逐渐增大的趋势,并表现出不同的生长速率和特点。

此外,我们还注意到肿瘤可通过血液或淋巴系统进行转移扩散,进一步危及生命。

在治疗实验中,我们使用了常见的抗肿瘤药物,观察和记录了肿瘤对药物的反应和治疗效果。

结果显示,不同药物对肿瘤的治疗效果具有一定差异,且肿瘤对药物基因的敏感性也存在差异。

这些发现为肿瘤治疗提供了新的思路和策略。

此外,我们还做了一系列生物学分析,包括组织切片、免疫组织化学染色和基因表达分析等。

通过这些实验,我们深入了解了肿瘤的组织学特征和分子机制,为进一步研究提供了有效的实验数据和依据。

总结而言,肿瘤动物实验为我们提供了关于肿瘤的重要信息和

数据。

通过对动物模型中肿瘤的观察和实验干预,我们深入了解了肿瘤的发展机制、治疗响应和分子特征。

这些发现为肿瘤治疗和研究提供了新的理论基础和临床指导。

在未来的研究中,我们将进一步优化实验设计,加强实验数据的统计和分析,以推动肿瘤研究的进一步发展和转化应用。

文章编号(A r t ic le ID):1009-2137(2009)05-1390-04・综述・淋巴瘤动物模型研究进展刘芳,赵彤1佛山科学技术学院医学院基础医学部生理教研室,广东佛山,528000;1南方医科大学基础医学院病理系,广东广州,510515摘要 淋巴瘤是发生于淋巴造血系统的恶性肿瘤。

建立成熟稳定的动物模型在淋巴瘤病变机理前瞻性研究及进行有效临床治疗的药理研究中占据十分重要的地位。

现对淋巴瘤各类动物模型的建立方法、模型特点及其应用等方面进行综述。

关键词 淋巴瘤;动物模型;裸鼠中图分类号 R733文献标识码 AAdvance of Study on An i m a l M odels of L y m pho ma———ReviewL I U Fang,ZHAO Tong1D epa rt m ent of Physiology,Foshan U niversity M edica l College,Foshan,Guangdong P rovince,528000China;1D epa rt m ent of Pa tholo2 gy,Southern M edica l U niversity B asic M edica l College,Guangzhou510515,G uangdong P rovince,ChinaCorresponding Author:ZHAO Tong,P rofessor.Tel:(020)61648228.E2m a il:zhaotongketizu@A b s t ra c t L ym phom a is a kind of m alignant tum ors that takes p lace in the lym phoid and hem atological system.It is i m portant to establish app rop riate and stable ani m al m odels of lym phom a and they are useful for the experi m ental research of m echanism s and efficient treat m ent of disease.In this article the establishm ent m ethods,characteristics and p ractical use of various ani m al m odels of lym phom a w ere review ed.K e y w o rd s lym phom a;ani m al m odel;nude m ouseJ Exp H em a tol2009;17(5):1390-1393 淋巴瘤是发生于淋巴结及/或淋巴结外淋巴组织的恶性肿瘤。

肿瘤动物模型的建立及应用肿瘤动物模型是一种在动物体内模拟人类肿瘤发展过程的实验模型,被广泛用于肿瘤的病理生理学、分子生物学、药理学等研究。

通过建立肿瘤动物模型,可以加深对肿瘤的发生、发展、转移和抑制机制的了解,同时也可以评估新药物及治疗策略的有效性。

下面将探讨肿瘤动物模型的建立及应用。

首先,肿瘤动物模型的建立是一个复杂而具有挑战性的过程。

一般来说,肿瘤动物模型的建立可以分为自发性肿瘤模型和人工诱导肿瘤模型两种类型。

自发性肿瘤模型主要是利用动物自身遗传倾向或环境诱导等因素,在动物体内自发产生肿瘤。

比如在家养动物中,很多小鼠和家兔由于遗传因素或者饮食、环境等长期暴露,会自发产生肿瘤。

这种模型更接近人类肿瘤的发展过程,但是其建立的可控性和可重现性较差,需要耗费大量的时间和经费。

人工诱导肿瘤模型则是通过外界的干预手段,比如化学药物、辐射等方式,直接在动物体内诱导肿瘤的产生。

这类模型具有较好的可控性和可重现性,可以更好地满足科研实验的需要。

常用的人工诱导肿瘤模型包括移植肿瘤模型、化学诱导模型、基因编辑模型等。

其次,肿瘤动物模型的应用范围非常广泛。

一方面,肿瘤动物模型可以用于研究肿瘤的发生机制和发展过程。

比如,利用肿瘤动物模型可以深入探究各种致癌物质或致癌基因对肿瘤发生的影响,分析肿瘤细胞的生物学特性和转移能力等。

通过模拟肿瘤的生长形态,可以更好地了解肿瘤细胞的生理活动和分子机制,为探寻肿瘤治疗策略提供理论依据。

另一方面,肿瘤动物模型还可以用于筛选和评估抗肿瘤药物。

通过向肿瘤动物模型中输入肿瘤细胞或移植肿瘤组织,可以评估新药物对肿瘤生长的抑制效果,了解药物的毒副作用、适应症等。

这种通过体内实验评估药物疗效和安全性的方法,大大提高了新药物研发的效率和成功率。

此外,肿瘤动物模型还被广泛用于研究肿瘤的诊断和预后指标、肿瘤免疫治疗、基因治疗等领域。

通过模拟肿瘤动物模型,可以更好地理解和验证这些新技术和新疗法在肿瘤治疗中的应用。

小鼠白血病和淋巴瘤的研究小鼠白血病和淋巴瘤是常见的实验动物模型,被广泛应用于白血病和淋巴瘤的研究中。

这些模型为科学家们提供了丰富的机会,以深入了解这些疾病的发病机制、寻找新的治疗方法,并为临床研究提供重要的参考。

1. 小鼠白血病研究小鼠白血病是一种造血系统恶性疾病,其中造血干细胞或者造血细胞异常地增生和聚集,导致正常造血功能受阻。

在小鼠白血病的实验模型中,科学家们通过将白血病相关基因或突变体导入小鼠体内,模拟人类白血病的发展过程。

2. 小鼠淋巴瘤研究小鼠淋巴瘤是一种淋巴系统恶性肿瘤,它起源于淋巴细胞,通常表现为淋巴结肿大。

在淋巴瘤的研究中,科学家们通过引入淋巴瘤相关基因突变或突变体,成功构建小鼠淋巴瘤模型,用于探索淋巴瘤的发病机制和治疗方法。

3. 实验动物模型的优势小鼠作为实验动物模型在白血病和淋巴瘤研究中具有诸多优势。

首先,小鼠的基因组与人类基因组的相似性较高,使得其作为模型更有代表性。

其次,小鼠具有较短的繁殖周期和较低的饲养成本,能够满足大规模实验需求。

此外,小鼠模型还能够通过基因转染、基因敲除和基因突变等方法进行个体定制,进一步强化模型的准确性。

4. 白血病和淋巴瘤研究的进展借助小鼠模型,科学家们在白血病和淋巴瘤的研究中取得了许多重要的进展。

例如,通过揭示白血病发生的分子机制,科学家们发现特定基因的突变与白血病的发展相关,为白血病的早期诊断和治疗提供了新的思路。

在淋巴瘤的研究中,科学家们发现某些抗体药物能够靶向淋巴瘤细胞表面的特定蛋白,实现对淋巴瘤的精准治疗。

5. 临床应用前景小鼠白血病和淋巴瘤模型的研究成果为未来的临床应用提供了重要的参考。

这些模型不仅可以帮助研究人员验证治疗药物的安全性和有效性,还可以为个体化医疗提供基础。

通过分析不同患者的基因和白血病或淋巴瘤特征之间的关联,有望开发出针对特定基因突变的靶向疗法,提高患者的治疗效果。

结论小鼠白血病和淋巴瘤模型的研究为白血病和淋巴瘤的发病机制、治疗方法以及个体化医疗提供了重要的理论和实践基础。

Lung Cancer 73 (2011) 211–216Contents lists available at ScienceDirectLungCancerj o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w.e l s e v i e r.c o m /l o c a t e /l u n g c anDuration of prior gefitinib treatment predicts survival potential in patients with lung adenocarcinoma receiving subsequent erlotinibKazuhiro Asami a ,∗,Masaaki Kawahara b ,Shinji Atagi a ,Tomoya Kawaguchi a ,Kyoichi Okishio aa Kinki-chuo Chest Medical Center,1180Nagasone-cho,Kita-ku,Sakai City,Osaka 591-8555,Japan bOtemae Hospital,1-5-34Otemae,Chuo-ku,Osaka,Japana r t i c l ei n f oArticle history:Received 9August 2010Received in revised form 19October 2010Accepted 18December 2010Keywords:Gefitinib ErlotinibEGFR mutationResistance to EGFR-TKIsTime to progression of gefitiniba b s t r a c tPurpose:We investigated survival potential in patients receiving erlotinib after failure of gefitinib,focus-ing on response and time to progression (TTP)with gefitinib.Methods:We retrospectively reviewed lung adenocarcinoma patients who received erlotinib after expe-riencing progression with gefitinib.Our primary objective was to evaluate the prognostic significance of erlotinib therapy.Results:A total 42lung adenocarcinoma patients were included in this study.Overall disease control rate was 59.5%(partial response [PR],2.4%;stable disease [SD],57.1%).Median overall survival was 7.1months,and median progression-free survival was 3.4months.The number of patients who achieved PR and non-PR (SD+progressive disease [PD])with gefitinib were 22(52%)and 20(48%),respectively.Patients with PR for gefitinib showed significantly longer survival times than those with non-PR (9.2vs.4.7months;p =0.014).In particular,among PR patients,those with TTP <12months on gefitinib showed significantly longer survival times than those with TTP ≥12months (10.3vs.6.4months;p =0.04).Conclusions:Erlotinib may exert survival benefit for lung adenocarcinoma patients with less than 12months of TTP of prior gefitinib who achieved PR for gefitinib.© 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.1.IntroductionGefitinib and erlotinib are oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs).Gefitinib has been reported to be effective in limited populations such as never smokers,Asians,and patients with adenocarcinoma,and is particularly effective in patients with EGFR mutations [1–3].Erlotinib,which has a sim-ilar quinazoline frame to gefitinib,is the first EGFR-TKI shown to provide survival benefit in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)[4]:the BR.21trial revealed significantly longer sur-vival times among patients who received erlotinib compared with a placebo group [4].In addition,these two EGFR-TKIs have been found to occasionally induce a particularly significant response in EGFR-mutant patients.However,despite this documented efficacy,most cancer clones acquire resistance to these particular com-pounds over time [5].Previous studies have demonstrated that amplified MET onco-gene and secondary EGFR T790M mutations are most commonly responsible for resistance to gefitinib and erlotinib [6,7].Indeed,several previous studies showed that secondary EGFR T790M muta-tion and MET amplification occurred in nearly half and 20%of lung∗Corresponding author.Tel.:+81722523021;fax:+81722511372.E-mail address:kazu.taizo@ (K.Asami).cancer specimens that had become resistant to EGFR-TKIs,respec-tively [8–11].In addition,the majority of patients who showed secondary resistance had EGFR mutations such as exon 19dele-tion mutations or L858R point mutation,which have been found to be sensitive to EGFR-TKIs [12,13].Several reports have demonstrated clinical benefits when administering erlotinib to NSCLC patients following failure of gefi-tinib [14–18];in contrast,one previous report has suggested that no erlotinib-derived clinical benefit can be expected in patients who failed gefitinib [19].However,reports thus far have all had small sample sizes,and clear findings regarding efficacy of erlotinib in patients who failed gefitinib have yet to be obtained.Consequently,whether or not erlotinib is useful in these patients remains contro-versial.We hypothesize that tumor clones may require exposure to gefi-tinib treatment with a positive response for a specific duration to acquire secondary common resistance to EGFR-TKIs.Even if a patient experiences tumor progression on gefitinib therapy,sub-sequent erlotinib therapy may nevertheless still be able to inhibit progression,provided the tumor clones did not acquire secondary resistance.As such,in positive-responder patients with confirmed progression within a specific duration of gefitinib treatment,some tumor clones may remain sensitive to erlotinib,and therefore these patients may still experience survival benefit with erlotinib treat-ment.0169-5002/$–see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.12.014212K.Asami et al./Lung Cancer73 (2011) 211–216Here,we conducted a retrospective study primarily aimed at assessing overall survival(OS)of patients who received erlotinib therapy after failure with gefitinib.We also attempted to charac-terize the clinical features of patients who benefited from erlotinib treatment.2.Patients and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed records for patients with histopathologically diagnosed lung adenocarcinoma who received erlotinib after experiencing progression on gefitinib at Kinki-chuo Chest Medical Center between December2008and October2009. Responses were evaluated based on patient records and radio-graphic studies,such as chest roentgenograms and computed tomographic(CT)and magnetic resonance imaging(MRI)scans. We examined EGFR mutation status using the PCR-invader method with paraffin sections of biopsy specimens from patients.Time to progression(TTP)with gefitinib was defined as the period from initiation of gefitinib therapy to the date when dis-ease progression was confirmed.Overall survival was defined as the period from initiation of erlotinib therapy to the date of death or last follow-up.Disease control rate(DCR)was defined as com-plete response(CR)plus partial response(PR)plus stable disease (SD).Evaluation of response to gefitinib and erlotinib therapy by CT scan was performed according to the response evaluation crite-ria in solid tumors(RECIST).Stable disease plus progressive disease (PD)with prior gefitinib treatment was defined as“non-PR.”Categorical outcomes,including DCRs,were compared using the 2test,and survival distribution was estimating using the Kaplan–Meier method.Overall survival and progression-free sur-vival(PFS)were compared with regard to demographic factors such as gender,performance status,EGFR mutation status,response to gefitinib,TTP with gefitinib,and toxicity grade of skin rash,which may be associated with survival,using the log-rank test.Values were considered statistically significant for p<0.05.A multivariate Cox-proportional-hazards model was used to determine the clini-cal variables which influenced OS.Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software ver.11.0for Windows(IBM,Chicago,IL, USA).3.Results3.1.Patient characteristicsForty-two patients with lung adenocarcinoma were reviewed in the present study.All patients became refractory to gefitinib dur-ing the course of treatment and were subsequently switched to erlotinib therapy.Patient characteristics are described in detail in Table1.Thirty patients(71%)had received1or2regimens before Table1Patient characteristics.Number(%)Median age,years(range)65(31–85) SexMale13(31)Female29(69)Smoking historyNever28(67)Former/current14(33)ECOG score0–124(57)2–418(43)Cancer stageIIIB8(19)IV34(81) Number of previous treatments with erlotinib1–230a(71)3≤12(29) EGFR mutationExon19deletion mutation14(33)L858R14(33)Exon18point mutation1(2)Wild13(32)TTP with gefitinib treatment,months(range)8.1(0.9–40.7) <1229(69)≤1213(31)Response to gefitinibCR0(0)PR22(53)SD17(40)PD3(7)EGFR,epidermal growth factor receptor;TTP,time to progression;CR,complete response;PR,partial response;SD,stable disease;PD,progressive disease;ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.a Two patients received gefitinib asfirst-line treatment.initiation of erlotinib and2(7%)had received gefitinib asfirst-line treatment.EGFR mutations were detected in29(69%)patients:14(33%) had exon19deletions,14(33%)had L858R mutations,and1(2%) had an exon18point mutation.The median TTP with gefitinib treatment was8.1months.Thirteen(31%)patients had TTPs of12 months or more,while29(69%)had TTPs of less than12months. Twenty-two(53%)patients receiving gefitinib achieved PR,and17 (40%)achieved SD.None achieved CR while receiving gefitinib ther-apy.The response rate(RR)and DCR for gefitinib were53%(22of 42patients)and93%(39of42patients),respectively.Of the22 patients who achieved PR with gefitinib,19(86%)were found to have EGFR mutations.Of the20patients who had SD or PD(non-PR)Table2Response to erlotinib according to the response to prior gefitinib and EGFR mutation status.EGFR mutation Response to gefitinibPR(n=22)Non-PR a(n=20)SD(n=17)PD(n=3)Positive,n(%)Negative b,n(%)Positive,n(%)Negative,n(%)Positive,n(%)Negative,n(%) Response to erlotinib PR(N=1)1(4.5)0(0)0(0)0(0)0(0)0(0) SD(N=24)14(64)1(4.5)3(18)5(29)0(0)1(33)PD(N=17)4(18)2(9)6(35)3(18)1(33)1(33)EGFR,epidermal growth factor receptor;PR,partial response;SD,stable disease;PD,progressive disease.Overall disease control rate(PR+SD)was73%(EGFR mutation-positive:15/22[68%],EGFR mutation-negative:1/22[5%])among patients who achieved PR with gefitinib and45%(EGFR mutation-positive:3/20[15%],EGFR mutation-negative:6/20[30%])among patients with non-PR(SD+PD for gefitinib)with gefitinib treatment.Overall disease control rate was62%(PR for gefitinib:15/29[52%],non-PR for gefitinib:3/29[10%])in EGFR mutation-positive patients and54%(PR for gefitinib:1/13[8%],non-PR for gefitinib:6/13[46%])in EGFR mutation-negative patients.a Defined as SD plus PD with prior gefitinib therapy.b EGFR wild-type.K.Asami et al./Lung Cancer73 (2011) 211–216213 Table3Response to erlotinib stratified by TTP with prior gefitinib treatment.(A)TTP with gefitinib<12monthsResponse to gefitinib TTP with gefitinib(months)<12(n=29)PR(n=11)n(%)Non-PR(n=18)SD(n=15)n(%)PD(n=3)n(%) Response to erlotinib PR(n=1)1b(9)0(0)0(0)SD(n=17)8a,b(73)8a(44)1(6)PD(n=11)2(18)7(39)2(11)B.TTP with gefitinib≥12monthsResponse to gefitinib TTP with gefitinib(months)≥12(n=13)PR(n=11)n(%)Non-PR(n=2)SD(N=2)n(%)PD(N=0)n(%) Response to erlotinib PR(n=0)0(0)0(0)0(0)SD(n=7)7(64)0(0)0(0)PD(n=6)4(36)2(100)0(0)EGFR,epidermal growth factor receptor;PR,partial response;SD,stable disease;PD,progressive disease;TTP,time to progression.Overall disease control rate was62%(PR for gefitinib:9/29[31%],non-PR for gefitinib:9/29[31%])in patients with TTP of gefitinib<12months.Overall disease control rate was54%(PR for gefitinib:7/13[54%], non-PR for gefitinib:0/13[0%])in patients with TTP of gefitinib≥12months.a Ten patients showed improvement of target lesions,but not to PR standards.Seven and three patients achieved PR and SD,respectively,with gefitinib treatment.b A second biopsy from progression lesions was performed in three patients(one had PR and2had SD with erlotinib)who achieved PR with gefitinib.Exon19deletion mutations which were the same pattern as detected infirst biopsy specimen for primary diagnosis of NSCLC were identified,whereas EGFR T790M mutation,which endowed secondary common resistance to EGFR-TKIs,was not identified in those biopsy specimens.with gefitinib,EGFR mutations were detected in10(50%).Among patients with EGFR mutations,only one showed PD with gefitinib therapy,and RR and DCR in this group were66%(19of29)and97% (28of29),respectively.3.2.ResponseOn erlotinib therapy,1of42patients achieved PR,and24had SD.No patients achieved CR with erlotinib.Overall RR and DCR for erlotinib were2.4%(one of42)and59.5%(25of42),respectively.Response to erlotinib categorized by response to prior gefi-tinib duration and EGFR mutation status is described in Table2. Among patients who achieved PR with gefitinib,one achieved PR and15patients achieved SD with erlotinib therapy.Patients who achieved PR with gefitinib showed higher DCRs with erlotinib than patients who had non-PR with gefitinib(16[73%]of22vs.9[45%] of20),albeit without statistical significance(p=0.07).In addi-tion,EGFR mutation status was not found to be associated with response to erlotinib;in terms of DCR,no significant difference was noted between EGFR-mutant patients(18/29)and EGFR non-mutant patients group(7/13)(62%vs.54%,p=0.616).Time to progression with prior administration of gefitinib was not found to be associated with achieving a response with subse-quent erlotinib.Details regarding response to erlotinib categorized by TTP with gefitinib are shown in Table3.DCR among patients experiencing progression after less than12months of gefitinib therapy was18/29(62%).In contrast,DCR among patients with TTPs of12months or more was7/13(54%).No statistical significant difference in DCR was noted between these two groups accord-ing to TTP with prior administration of gefitinib(p=0.62).Of the 24patients who achieved SD with erlotinib therapy,10showed improvement in target lesions which had been exacerbated during gefitinib treatment;all10were EGFR-mutant patients(4L858R, 5exon19deletion mutations,and1exon18point mutation),and TTPs with gefitinib were all less than12months.Of the two patients who received gefitinib asfirst-line treatment,one had an EGFR L858R mutation and showed responses to gefitinib and subsequent erlotinib of PR and SD,respectively.While this particular patient showed a relatively long TTP(39.5months)with gefitinib,disease progression was confirmed4months after initiation of erlotinib therapy,and OS was58.6months.The other patient who received gefitinib asfirst-line treatment had EGFR-wild type,and responses to both gefitinib and subsequent erlotinib treatment were PD.TTP and OS in this patient were3and7.4months,respectively.A second biopsy of the progressed lesions was performed in three patients after gefitinib therapy failed.While exon19deletion mutations of the same pattern as noted in thefirst biopsy specimen for primary diagnosis were also detected on this second biopsy, we noted no EGFR T790M mutations.Of note,however,was the fact that imagingfindings for lesions after erlotinib therapy were improved on the second biopsy(Table3).3.3.SurvivalMedian OS and median progression-free survival(PFS)were 7.1months(95%confidence interval[CI]:4.4–9.8months)and3.4 months(95%CI:1.1–5.7months),respectively(Fig.1).Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors was performed using a Cox propor-tional hazards model to determine which clinical variables were most strongly associated with OS(Table4).Response to gefitinibTable4Multivariate analysis of prognostic variables for OS by use of a Cox proportional-hazards model.Multivariate analysisp a Hazard ratio95%CISex0.51 1.350.55–3.31 ECOG score0.190.580.25–1.31 EGFR mutation0.78 1.130.48–2.70 Response to gefitinib0.0050.230.80–0.64 TTP of gefitinib0.050.340.12–1.01 Grade of skin rash0.290.640.27–1.47EGFR,epidermal growth factor receptor;TTP,time to progression;CI,confidence interval;ECOG,Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group;PR,partial response.Response to gefitinib was the only independent prognostic factor.TTP with gefitinib showed borderline significance.Variables were compared as paired categories:sex(female vs.male),ECOG score(0–1vs.2–4),response to gefitinib(PR vs.non-PR),TTP of gefitinib(<12months vs.≥12months),grade of skin rash(3vs.1–2).a p<0.05was considered significant.214K.Asami et al./Lung Cancer73 (2011) 211–216Fig.1.Kaplan–Meier plot of survival time with erlotinib.(A)Overall survival rates and(B)progression-free survival rates of42patients.MST:median survival time; mPFS:median progression-free survival.was found to be the only independent prognostic factor(hazard ratio=0.23;95%CI:0.08–0.64,p=0.005),and time to progression with gefitinib showed borderline significance(hazard ratio=0.34; 95%CI:0.12–1.01,p=0.05).Kaplan–Meier curves of survival time according to response to prior gefitinib therapy are shown in Fig.2.Patients who achieved PR while receiving gefitinib therapy showed significantly longer OS(p=0.014).However,no significant difference was noted in PFS between patients with PR for gefitinib and those with non-PR(4.7 months[95%CI:2.9–6.5months]vs.1.8months[95%CI:1.4–2.2 months];p=0.122).Time to progression with gefitinib showed a borderline significant impact on survival with erlotinib therapy. However,among patients who achieved PR with gefitinib,TTP with gefitinib therapy was strongly correlated with survival time. Kaplan–Meier curves of survival time for patients who achieved PR with gefitinib stratified according to TTP are shown in Fig.3. Patients with TTPs of less than12months with gefitinib ther-apy were found to have significantly longer OS(10.3months[95% CI:7.0–13.6months]vs.6.4months[95%CI:2.6–10.2months]; p=0.04)and longer PFS(6.4months[95%CI:3.6–9.2months]vs.3.4 months[95%CI:1.2–5.6months];p=0.19)than patients with TTPs of12months or more.However,no statistically significant differ-ence was noted between the two groups in terms of PFS(p=0.19).Fig.2.Kaplan–Meier plot of survival time with erlotinib.(A)Overall survival rates and(B)progression-free survival rates stratified by response to prior gefitinib.Non-PR is defined as SD plus PD with gefitinib therapy.In addition,we found that skin rash was not predictive of sur-vival with erlotinib therapy.All patients in the present study were affected by rash of some grade while receiving erlotinib.The degree of skin rash toxicity due to erlotinib exceeded the grade noted dur-ing gefitinib treatment in32patients.Seven patients required dose reduction of erlotinib due to grade3skin ing a Cox propor-tional hazard model,we determined that skin rash grade had no impact on survival(hazard ratio=0.64[95%CI:0.27–1.47];p=0.29).4.DiscussionHere,we investigated survival potential in patients receiv-ing erlotinib after failure of gefitinib,focusing on response and TTP with gefitinib.Ourfindings suggest that administration of erlotinib subsequent to gefitinib may exert survival benefit in for-mer gefitinib-positive responders.Further,among those former responders,most with TTP<12months may not yet have sec-ondary resistance to EGFR-TKIs.Ourfindings suggest little chance for patients to achieve a high response with erlotinib therapy after experiencing progression with gefitinib therapy.This observation may be due to these two EGFR TKIs sharing the same mechanism of EGFR blockade or to cross resistance[5].Our retrospective study showed that response achieved with prior administration of gefitinib was the only prognostic factor for subsequent erlotinib therapy after experiencing progression on gefitinib therapy.In particular,among patients who achieved PR with gefitinib,patients with TTPs of less than12months with gefitinib therapy were found to have significantly longer OS thanK.Asami et al./Lung Cancer73 (2011) 211–216215Fig.3.Kaplan–Meier plot of survival time for patients who achieve PR with gefitinib.(A)Overall survival rates and(B)progression-free survival rates stratified by TTP with gefitinib.patients with TTPs of12months or more.In addition,most of these patients showed some degree of improvement in imagefind-ings after subsequent erlotinib therapy.We noted no EGFR T790M mutations in any of three patients who underwent a second biopsy of their progressed lesions after failure with gefitinib therapy.We therefore supposed that most patients with TTP<12months may have not yet acquired the EGFR T790M mutation.However,we only investigated the presence of a secondary EGFR T790M mutation in three patients in the present study.Validation of this hypothesis will require collection of more molecular information from patients who are no longer responsive to gefitinib in the future.Shepherd et al.demonstrated that TTP was2.6months in NSCLC patients who had previously been treated with docetaxel therapy [20].We observed that PFS was3.4months in patients with TTP≥12 months who achieved PR in our study,a duration which appears improved over that demonstrated by Shepherd et al.Given these findings,we posited that,regardless of duration of gefitinib ther-apy,subsequent erlotinib may be able to prolong PFS compared to chemotherapy with cytotoxic agent provided the patients demon-strated a positive response with gefitinib.However,given that our results were obtained in a retrospective study with an extremely small sample population,a prospective study is warranted to clar-ify whether or not erlotinib administered subsequent to gefitinib can elicit greater survival benefit in gefitinib-positive responders than chemotherapy with cytotoxic agents.We noted here that treatment with erlotinib following gefitinib resulted in more toxic grades of skin rash in patients,findings which suggest that erlotinib may have greater biological activity than gefitinib.Several other investigators have also suggested based on their ownfindings that erlotinib may have higher biological activity than gefitinib.Costa et al.showed that differing efficacy between gefitinib and erlotinib was due to differences in commonly admin-istered dosages between the two drugs[21].Gefitinib(250mg per day)is typically administered at one third of its maximum-tolerated dose,whereas erlotinib(150mg per day)is administered at its maximum tolerated dose.In vitro data showed that the mean concentration of gefitinib was0.24g/ml at the300-mg daily dose and1.1g/ml at1000mg/day.In contrast,median concentration of erlotinib at150mg/day was1.26g/ml.These previousfindings suggest that erlotinib(150mg/day)has a higher biological dose of EGFR inhibition than gefitinib(250mg/day).Recent studies have demonstrated that the increased biological activity of EGFR-TKIs is associated with control of tumor clones. Yoshimasu et al.reported observing a dose-response relationship between inhibition rates and gefitinib concentration[22].Clarke et al.reported that high-dose erlotinib was effective in controlling leptomeningeal metastases progression while receiving standard erlotinib therapy in EGFR-mutant patients[23].These authors demonstrated that a weekly1200-mg dose of erlotinib controlled leptomeningeal metastases in a patient who was no longer respon-sive to a standard daily dose of erlotinib(150mg).Ourfindings here suggest that a treatment duration of12 months of gefitinib therapy may be the borderline period for tumor clones to attain resistance to EGFR-TKIs.However,speculation as to whether or not previously EGFR-TKI-sensitive clones gradually grow resistant to EGFR-TKIs has not been resolved.Further studies are necessary to validate ourfindings.In conclusion,gefitinib responders may achieve survival ben-efits from erlotinib therapy after experiencing progression with gefitinib.Among patients who have been receiving gefitinib ther-apy for less than12months,tumor clones may not yet have acquired a secondary mutation.However,further studies are needed to clarify precisely how tumor clones attain such secondary resistance to EGFR-TKIs.Conflicts of interest statementNone declared.AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to the staff of Kinki-Chuo Chest Medical Cen-ter for their helpful comments.We are especially indebted to Dr. Masahiko Ando of Kyoto University for support on statistical anal-yses.References[1]Moscatello DK,Holgado-Madruga M,et al.Frequent expression of a mutantepidermal growth factor receptor in multiple human tumors.Cancer Res 1995;55(23):5536–9.[2]Janne PA,Engelman JA,et al.Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations innon-small-cell lung cancer:implications for treatment and tumor biology.J Clin Oncol2005;23(14):3227–34.[3]Baselga J,Arteaga CL.Critical update and emerging trends in epidermal growthfactor receptor targeting in cancer.J Clin Oncol2005;23(11):2445–59.[4]Pao W,Miller V,Zakowski M,et al.EGF receptor gene mutations are commonin lung cancers from“never smokers”and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib.Proc Natl Acad Sci2004;101:13306–11. [5]Mitsudomi T,Kosaka T,Endoh H,et al.Mutations of the epidermal growth factorreceptor gene predict prolonged survival after gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with postoperative recurrence.J Clin Oncol 2005;23(11):2513–20.[6]Mok TS,Wu Y-L,et al.Gefitinib or carboplatin–paclitaxel in pulmonary adeno-carcinoma.N Engl J Med2009;361(September(10)):947–57.[7]Shepherd FA,Rodrigues Pereira J,et al.Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer.N Engl J Med2005;353(2):123–32.216K.Asami et al./Lung Cancer73 (2011) 211–216[8]Johnson JR,Cohen M,et al.Approval summary for erlotinib for treatmentof patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimen.Clin Cancer Res 2005;11(18):6414–21.[9]Allan S,et al.Efficacy of erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small celllung cancer(NSCLC)relative to clinical characteristics:subset analysis from the TRUST study.In:Poster presented at ASCO.2008.[10]Baselga J,Rischin D,et al.Phase I safety,pharmacokinetic,and pharmaco-dynamic trial of ZD1839,a selective oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor,in patients withfive selected solid tumor types.J Clin Oncol2002;20(November(21)):4292–302.[11]Hidalgo M,Siu LL,Nemunaitis J,Rizzo J,et al.Phase I and pharmacologic studyof OSI-774,an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid malignancies.J Clin Oncol2001;19(July(13)):3267–79.[12]Riely GJ,Pao W,et al.Clinical course of patients with non-small cell lung cancerand epidermal growth factor receptor exon19and exon21mutations treated with gefitinib or erlotinib.Clin Cancer Res2006;12(3(Pt1)):839–44.[13]Choong NW,Dietrich S,Seiwert TY,Tretiakova MS.Gefitinib response oferlotinib-refractory lung cancer involving meninges-role of EGFR mutation.Nat Clin Pract Oncol2006;3(January(1)):50–7[quiz1p following57].[14]Mitsudomi T,Kosaka T,Endoh H,Yoshida K.Mutational analysis of theEGFR gene in lung cancer with acquired resistance to gefitinib.J Clin Oncol 2006;24(18S):7074.[15]Pao W,Balak MN,Riely GJ,Li AR.Molecular analysis of NSCLC patients withacquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib.J Clin Oncol2006;24(18S):7078.[16]Bean J,Brennan C,Shih JY,Riely G,Viale A.MET amplification occurs with orwithout T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resis-tance to gefitinib or erlotinib.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA2007;104(December(52)):20932–27.[17]Engelman JA,Zejnullahu K,Mitsudomi T.MET amplification leads to gefitinibresistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3signaling.Science2007;316(May (5827)):1039–43.[18]Engelman JA,Zejnullahu K,Mitsudomi T,et al.MET amplification leads togefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3signaling.Science 2007;316(May(5827)):1039–43[Epub2007April26].[19]Balak MN,Gong Y,Riely GJ,et al.Novel D761Y and common secondary T790Mmutations in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung adenocarcinomas with acquired resistance to kinase inhibitors.Clin Cancer Res2006;12(Nov(21)):6494–501.[20]Shepherd FA,Dancey J,Ramlau R,et al.Prospective randomized trial ofdocetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.J Clin Oncol 2000;18(10):2095–103.[21]Costa DB,Schumer ST,Tenen DG,et al.Differenctial responses to erlotinib inepidermal growth factor receptor(EGFR)-mutated lung cancers with acquired resistance to gefitinib carrying the L747S or T790M secondary mutations.J Clin Oncol2008;26(7):1182–4.[22]Yoshimasu T,Ohta F,Oura S,et al.Histoculture drug response assay for gefi-tinib in non-small-cell lung cancer.Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg2009;57(March(3)):138–43[Epub2009March12].[23]Clarke JL,Pao W,Wu N,et al.High dose weekly erlotinib achieves thera-peutic concentrations in CSF and is effective in leptomeningeal metastases from epidermal growth factor receptor mutant lung cancer.J Neurooncol 2010;February.。

肿瘤动物模型的构建——淋巴瘤篇导语淋巴瘤(Lymphoma)是一种原发于淋巴结和淋巴组织的恶性肿瘤。

近年来其发病率正以每年4%的速度上升。

初期往往仅因表现为持续发烧或淋巴结肿大,而被大家忽视。

加上淋巴瘤亚型(>80种)众多,治疗困难重重。

因此迫切需要建立正确的动物模型,这对于研究淋巴瘤的发病机制和治疗手段十分重要。

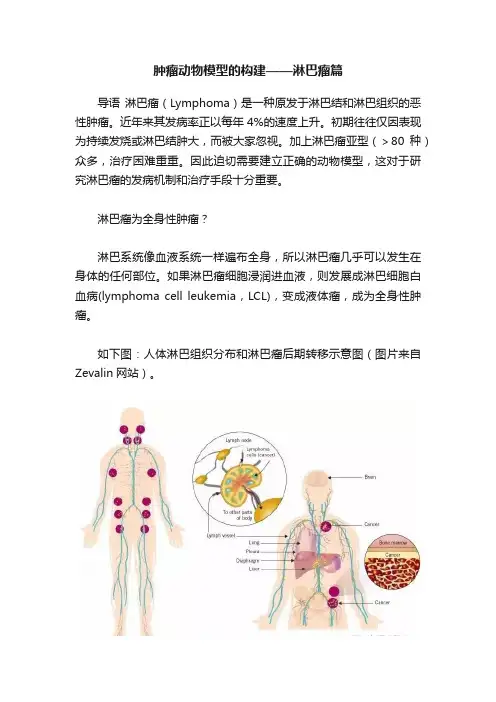

淋巴瘤为全身性肿瘤?淋巴系统像血液系统一样遍布全身,所以淋巴瘤几乎可以发生在身体的任何部位。

如果淋巴瘤细胞浸润进血液,则发展成淋巴细胞白血病(lymphoma cell leukemia,LCL),变成液体瘤,成为全身性肿瘤。

如下图:人体淋巴组织分布和淋巴瘤后期转移示意图(图片来自Zevalin网站)。

淋巴瘤分类众多淋巴瘤种类繁多,发病机制复杂,分为霍奇金淋巴瘤(Hodgkin lymphoma,HL)和非霍奇金淋巴瘤(non-Hodgkin lymphoma,NHL)两类,其中以生发中心(Germinal center)来源的淋巴瘤占到NHL的80%,包括伯基特淋巴瘤,滤泡性淋巴瘤和弥漫大B淋巴瘤。

其发病机制是B细胞经历生发中心不同阶段时,基因发生突变易位等。

生发中心来源淋巴瘤发病机制示意图[1]临床上根据淋巴瘤分类分为多种细胞株,下面列举一些常用淋巴瘤细胞株:下面说说常见的淋巴瘤动物模型有哪些一、异种移植型淋巴瘤模型淋巴瘤细胞株或病人淋巴瘤组织种植于免疫缺陷动物体内,建立移植性淋巴瘤模型,是目前研究最多的肿瘤模型。

一般选择免疫缺陷小鼠:SCID小鼠或NOD/SCID小鼠淋巴瘤动物模型常选用SCID小鼠,它是一种先天性T/B淋巴细胞联合免疫缺陷动物,移植成功率比较高。

但SCID小鼠仍残留某些免疫功能,而NOD/SCID小鼠较SCID小鼠出现更多的免疫缺陷,它又降低了NK细胞的活性,成为淋巴瘤实验研究的有效工具。

异种移植进一步又分为细胞移植(CDTX)和组织块移植(PDTX)操作步骤如下图所示[2]:A(CDTX)和B(PDTX)注意:(1)细胞移植法:常用皮下荷瘤,也用腹腔注射,静脉注射和原位荷瘤。

动物模型在抗肿瘤药物研发中的应用随着人们生活水平的提高,人们的寿命也得到了较大的延长,但这也引发了人体中许多病症和疾病的发生。

其中,肿瘤病是一种比较严重的病症。

目前,为了控制和治疗人体内的肿瘤病,医学领域中涌现出了很多种类型的抗肿瘤药物。

但是,为了验证和检测这些药物的安全性和疗效,需要进行严格的检测和实验。

这就需要动物模型在抗肿瘤药物研发中的应用。

一、动物模型在抗肿瘤药物研发中的应用介绍动物模型指的是利用动物的实验结果,来预测人类疾病的发生和发展的一种科学方法。

它是一种科学实验方法,也是现代生命科学的重要部分之一。

动物模型被广泛应用于肿瘤药物研发中,其作用和价值不容忽视。

具体来说:1. 肿瘤病发生机制的研究动物模型可以利用普通的动物疾病模型,比如小鼠或大鼠,在人体内模拟出肿瘤病变过程。

这一稳定的模型,能够在人体肿瘤病细胞中复制人体内的肿瘤病症,从而掌握肿瘤病发生的一系列机理和机制。

这对于新型抗癌药物的研制,寻找分子信号通路和药物致瘤等方面都有一定的意义。

2. 抗肿瘤药物的筛选和策略动物模型能更好地预测药物在人体中的药性和疗效。

在研发过程中,通过建立不同的肿瘤动物模型,在体内对药物的毒性、代谢、疗效等进行实验验证,这是抗肿瘤药物研发中的重要环节。

并随着药物的研制和改善,新的疗效标准也提出,动物模型将一直作为生命科学领域中的重要实验模式,对药物研发及临床服用起到促进作用。

3. 剂量和效应关系的研究药物剂量和效应关系是药物研发的重要环节之一,动物模型能够利用药物的用途、药物在体内的代谢和药效等方面,为药物及剂量的研究及制定提供有效数据和参考。

二、动物模型在抗肿瘤药物研发中的意义动物模型在抗肿瘤药物研发中的应用被广泛认可。

通过在动物身上预测肿瘤病的发展机理,以及通过药物的剂量和疗效关系,我们能够更好地解决以下问题。

1. 提供药物研发的安全性指标动物模型在药物研发中提供了一种重要的安全性指标,在药物的前期研究和前期实验中,可以通过动物模型来预测药物的毒性、药物换算、药物代谢和药效等。

动物模型部分实验方法总结1、研究肿瘤细胞增殖 (1)2、研究肿瘤细胞转移 (2)2.1. 体外(浸润模型) (2)2.2. 体内(转移模型) (2)3、研究肿瘤细胞耐药 (4)3.1. 耐药细胞株的建立 (4)3.2. 裸鼠移植瘤耐药模型的建立 (5)从肿瘤起源分,肿瘤动物模型的分类如下:从研究目的来分,可以从增殖、转移、耐药三个角度来分析:1、研究肿瘤细胞增殖细胞准备:GeneA 敲减慢病毒感染细胞扩增至需要的细胞量。

分为:空白对照组、阴性对照组、实验组。

取Balb/c 裸鼠,雄性,6周龄,每组10只,适应一周后进行肿瘤细胞注射。

实验动物肿瘤模型自发性肿瘤模型 诱发性肿瘤模型移植性肿瘤模型 人体肿癌的异种移植性原位诱发 异位诱发 同种可移植性肿瘤 异种可移植性肿瘤 原位移植 异位移植XXX细胞消化离心后制成单细胞悬液,计数后取适量的细胞用PBS悬浮,在Balb/c裸鼠侧腹部皮下接种。

每只接种2×106个细胞,注射体积为100 μL。

此后,每隔5天测量注射部位肿瘤的体积。

30天后裸鼠小鼠腹腔注射80 mg/kg 戊巴比妥钠,小鼠麻醉后置蓝色背景布上拍照(侧卧位,接种部位朝上),小鼠颈椎脱臼处死,取出肿瘤称重,将肿瘤置蓝色背景布上拍照,肿瘤一分为二,一份4%多聚甲醛固定,待后续病理分析,一份-80℃冻存。

2、研究肿瘤细胞转移肿瘤转移的模型包括两大类:体外(浸润模型)和体内(转移模型)。

体外(浸润模型):了解肿瘤细胞对周围相连组织的侵润性。

体内模型主要研究肿瘤细胞的转移性即肿瘤细胞在远端组织形成病灶的能力。

2.1. 体外(浸润模型)例:浸润型脑胶质瘤动物模型的建立方法:取若干只Balb/c免疫缺陷裸鼠,将分离和鉴定并转染携带绿色荧光蛋白的脑胶质瘤干细胞立体定向法行小鼠颅内接种,每组10只。

小鼠麻醉后头部正中切口,剥离骨膜后钻孔(坐标是冠状缝后0.5 cm,矢状缝右侧2.5 cm) 。

取2 μL胶质瘤干细胞以1×104 cells /只小鼠的剂量,经微量注射器缓慢注射入鼠脑纹状体内(深度是2.5 ~3 mm) 。