魔鬼经济学(英文版)

- 格式:docx

- 大小:35.91 KB

- 文档页数:6

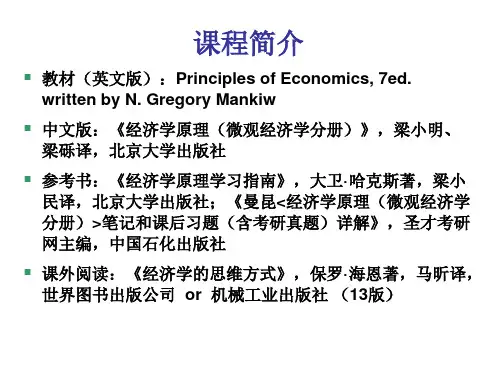

经济学原理英文版Economics is the study of how individuals, businesses, and governments allocate resources to satisfy their needs and wants. It is a social science that examines how people make choices under conditions of scarcity and the consequences of those choices for society. The principles of economics provide a framework for understanding the behavior of individuals, businesses, and governments in the marketplace.One of the fundamental principles of economics is the concept of opportunity cost. Opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative that is foregone when a choice is made. For example, if a student decides to spend an hour studying for an exam rather than going to the movies, the opportunity cost of studying is the enjoyment and entertainment that could have been gained from watching the movie. Understanding opportunity cost is important because it helps individuals and businesses make more informed decisions about how to allocate their resources.Another important principle of economics is the law of supply and demand. This principle states that the price of a good or service is determined by the relationship between the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded. When the supply of a good or service increases, and the demand for it remains constant, the price will decrease. Conversely, when the demand for a good or service increases, and the supply remains constant, the price will increase. Understanding the law of supply and demand is essential for businesses to set prices and for consumers to make purchasing decisions.In addition to opportunity cost and the law of supply and demand, economics also explores the concepts of production, consumption, and distribution. Production refers to the process of creating goods and services, while consumption refers to the use of those goods and services. Distribution involves the allocation of goods and services to individuals and businesses. These concepts are essential for understanding how resources are used and how wealth is created and distributed in society.Economics also examines the role of government in the economy. Governments play a critical role in regulating markets, providing public goods and services, andredistributing income. The study of economics helps us understand how government policies, such as taxes and subsidies, impact the behavior of individuals and businesses, as well as the overall performance of the economy.In conclusion, the principles of economics provide a framework for understanding how individuals, businesses, and governments make choices about how to allocate resources. By studying economics, we can gain insights into how markets work, how wealth is created and distributed, and how government policies impact the economy. Whether you are a student, a business owner, or a policymaker, a solid understanding of economics is essential for making informed decisions in today's complex and interconnected world.。

第一步:正三观在推荐任何经济学书之前,我不推荐你读任何的” 书“ 。

在你读任何的经济学书(无论是理论还是通俗读本之前),我们需要做的是:正三观。

为什么因为经济学是一门很模糊的学科,甚至在每个学校中的分类都不一样,有的学校放在商科,有的学校叫社会科学,有的学校叫科学。

所以,在经济学中是没有绝对的对错,只有不同的派别和有些看起来还不错有一些听起来对但是非常不靠谱。

所以在读任何”书“,甚至是教科书之前,需要端正下三观,了解下真正的世界。

说一句肯定会被抽的,但是我觉得是对的话:经济学本无基础,但是有初,中,高三段。

与基础相比更重要的是三观一定要正,不要被专业名字忽悠到。

很多东西是逻辑问题,不是学术问题。

在此推荐秒杀无数经济学教科书的一篇论文,这个论文可以秒杀掉市面上99%的经济学教科书。

How the Economic machine works - By Ray Dalio From Bridgewater?英文链接:宏观经济运行的框架(英文原版)by Ray中文翻译版本链接:理解宏观经济运行的框架(Ray Dalio)_百度文库首先,我们需要用这个文章好好正下三观。

无数的经济学书和理论都太浮云和浮夸了。

经济和金融,我只相信真正Hands on的人写出来的东西。

Ray Dalio现在卸任了Bridgewater的CEO,和另外2个合伙人转做Advisors,专门专注于投资方向决策。

Bridgewater现在应该仍然是全世界最大的宏观对冲基金。

这个文章用非常好的语言,充分的说明了这个世界到底是怎样的,调整并且融合了相当多的理论并且真正的和现实结合。

不管你是否有经济学功底是否真正懂得经济学,在你读任何数之前,必须读这个。

金融炼金术- 索罗斯豆瓣链接:金融炼金术(豆瓣)不用多说什么。

这个也是一个帮助你更好了解这个世界的经济与哲学构架的书。

索罗斯是少数几个业内的真正的大师级,并且愿意说真话表达真观点的人。

我保证上面两个作者说的都是真话,其他的现在很多书作者说的不是有偏颇就是有炒作或者就是在放屁。

魔鬼经济学读书笔记《魔鬼经济学》是XX年广东经济出版社出版的图书,作者是史蒂芬·列维特、史蒂芬·都伯纳。

以下是小编精心准备的魔鬼经济学读书笔记,大家可以参考以下内容哦!读书笔记:《魔鬼经济学》【1】《魔鬼经济学》是美国经济学家列维特和记者都伯纳合著的一套书。

书中所阐述的不是传统的经济学理论,而是如何站在经济学角度解决日常生活中的谜团。

万事万物皆有隐秘的一面,诱因是现代生活的根基,找到这些原因往往是解决问题的关键。

书中的前言部分就举了几个有意思的例子:20世纪90年代,美国本应飙升的犯罪率为何骤降?是因为管理、经济繁荣和新型治安策略?这些看似主观的因素听起来十分可靠,但却经不起推敲。

通过大量数据分析,结果出乎意料:堕胎合法化使潜在罪犯减少,从而导致犯罪率的下降。

专家,是指生活中掌握大量信息的人,例如医生、房屋中介、股票经纪人等。

然而现代社会,互联网的普及使专家所占的信息优势日益缩减。

专家所提出的理论有时是错的--他们也会利用信息优势谋取私利,错误的理论似乎顺畅无阻地从专家口中,传到记者耳中,然后进入大众思维,并迅速上升为传统观念。

所以,传统观念常常是错的。

但如果我们知道什么值得测评以及如何测评,就有利于理清这个纷繁复杂的世界。

如果你学会以正确的方式观察数据,某些以其他方式无法解答的谜团就会迎刃而解,因为要击碎混淆视听和自相矛盾的谎言,数据的力量就无可比拟。

“道德代表着人类对世界运转方式的期望,而经济学代表着其实际的运转方式。

”经济学是一门有关测评的学科,它包含一系列行之有效、用途广泛的工具。

但经济学的工具也完全可以用于分析其他话题,而且分析起来更有意思。

撇开道德立场,沉下心来钻研数据,结果常常会得出有悖于传统、出乎意料的发现。

因此,作者虚构了一门学科:魔鬼经济学。

这本书如同寻宝游戏,让人迫不及待地想探究某些有趣案例的客观价值。

那就让我们一起踏上这探索之旅吧!魔鬼经济学读书笔记【2】“如果伦理学给出了这个社会理想的运行模式的话,那么经济学则解释了社会是怎样运行的。

MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITIONWHAT’S NEW IN THE S EVENTH EDITION:There are no major changes to this chapter.LEARNING OBJECTIVES:By the end of this chapter, students should understand:what market structures lie between monopoly and competition.competition among firms that sell differentiated products.how the outcomes under monopolistic competition and under perfect competition compare.the desirability of outcomes in monopolistically competitive markets.the debate over the effects of advertising.the debate over the role of brand names.CONTEXT AND PURPOSE:Chapter 16 is the fourth chapter in a five-chapter sequence dealing with firm behavior and the organization of industry. The previous two chapters developed the two extreme forms of market structure—competition and monopoly. The market structure that lies between competition and monopoly is known as imperfect competition. There are two types of imperfect competition—monopolistic competition and oligopoly. This chapter addresses monopolistic competition while the final chapter in the sequence addresses oligopoly. The analysis in this chapter is again based on the cost curves developed in Chapter 13.The purpose of Chapter 16 is to address monopolistic competition—a market structure in which many firms sell products that are similar but not identical. Monopolistic competition differs from perfect competition because each of the many sellers offers a somewhat different product. As a result, monopolistically competitive firms face a downward-sloping demand curve while competitive firms face a horizontal demand curve at the market price. Monopolistic competition is extremely common.KEY POINTS:A monopolistically competitive market is characterized by three attributes: many firms, differentiatedproducts, and free entry.The long-run equilibrium in a monopolistically competitive market differs from that in a perfectly competitive market in two related ways. First, each firm in a monopolistically competitive market has excess capacity. That is, it chooses a quantity that puts it on the downward-sloping portion of the average-total-cost curve. Second, each firm charges a price above marginal cost.Monopolistic competition does not have all of the desirable properties of perfect competition. There is the standard deadweight loss of monopoly caused by the markup of price over marginal cost. In addition, the number of firms (and thus the variety of products) can be too large or too small. In practice, the ability of policymakers to correct these inefficiencies is limited.The product differentiation inherent in monopolistic competition leads to the use of advertising and brand names. Critics of advertising and brand names argue that firms use them to manipulate consumers’ tastes and to reduce competition. Defenders of advertising and brand names argue that firms use them to informconsumers and to compete more vigorously on price and product quality.CHAPTER OUTLINE:I. Between Monopoly and Perfect CompetitionA. The typical firm has some market power, but its market power is not as great as that described bymonopoly.B. Firms in imperfect competition lie somewhere between the competitive model and the monopoly model.C. Definition of oligopoly: a market structure in which only a few sellers offer similar or identical products.1. Economists measure a market’s domination by a small number of firms with a statistic called aconcentration ratio.2. The concentration ratio is the percentage of total output in the market supplied by the four largestfirms.3. In the . economy, most industries have a four-firm concentration ratio under 50%.D. Definition of monopolistic competition: a market structure in which many firms sell products that aresimilar but not identical.1. Characteristics of Monopolistic Competitiona. Many Sellersb. Product Differentiationc. Free EntryE. Figure 1 summarizes the four types of market structure. Note that it is the number of firms and the typeof product sold that distinguishes one market structure from another.II. Competition with Differentiated ProductsA. The Monopolistically Competitive Firm in the Short Run1. Each firm in monopolistic competition faces a downward-sloping demand curve because its product isdifferent from those offered by other firms.2. The monopolistically competitive firm follows a monopolist's rule for maximizing profit.a. It chooses the output level where marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost.b. It sets the price using the demand curve to ensure that consumers will demand exactly theamount produced.Figure 23. We can determine whether or not the monopolistically competitive firm is earning a profit or loss bycomparing price and average total cost.a. If P > ATC, the firm is earning a profit.b. If P < ATC, the firm is earning a loss.c. If P = ATC, the firm is earning zero economic profit.B. The Long-Run Equilibrium1. When firms in monopolistic competition are making profit, new firms have an incentive to enter themarket.a. This increases the number of products from which consumers can choose.b. Thus, the demand curve faced by each firm shifts to the left.c. As the demand falls, these firms experience declining profit.2. When firms in monopolistic competition are incurring losses, firms in the market will have anincentive to exit.a. Consumers will have fewer products from which to choose.b. Thus, the demand curve for each firm shifts to the right.c. The losses of the remaining firms will fall.3. The process of exit and entry continues until the firms in the market are earning zero profit.a. This means that the demand curve and the average-total-cost curve are tangent to each other.b. At this point, price is equal to average total cost and the firm is earning zero economic profit. Figure 3Remember that students have a hard time understanding why a firm will continue tooperate if it is earning “only” zero economic profit. Remind them that zero economic profitmeans that firms are earning an accounting profit equal to their implicit costs.Point out to students that, just like firms in perfect competition, firms in monopolisticcompetition also earn zero economic profit in the long run. Show them that this result occursbecause firms can freely enter the market when profits occur, driving the level of profits tozero. Any market with no barriers to entry will see zero economic profit in the long run.4. There are two characteristics that describe the long-run equilibrium in a monopolistically competitivemarket.a. Price exceeds marginal cost (due to the fact that each firm faces a downward-sloping demandcurve).b. Price equals average total cost (due to the freedom of entry and exit).C. Monopolistic versus Perfect CompetitionFigure 41. Excess Capacitya. The quantity of output produced by a monopolistically competitive firm is smaller than thequantity that minimizes average total cost (the efficient scale).b. This implies that firms in monopolistic competition have excess capacity, because the firm couldincrease its output and lower its average total cost of production.c. Because firms in perfect competition produce where price is equal to the minimum average totalcost, firms in perfect competition produce at their efficient scale.2. Markup over Marginal Costa. In monopolistic competition, price is greater than marginal cost because the firm has somemarket power.b. In perfect competition, price is equal to marginal cost.D. Monopolistic Competition and the Welfare of Society1. One source of inefficiency is the markup over marginal cost. This implies a deadweight loss (similar tothat caused by monopolies).2. Because there are so many firms in this type of market structure, regulating these firms would bedifficult.3. Also, forcing these firms to set price equal to marginal cost would force them out of business(because they are already earning zero economic profit).4. There are also externalities associated with entry.a. The product-variety externality occurs because as new firms enter, consumers get someconsumer surplus from the introduction of a new product. Note that this is a positive externality.b. The business-stealing externality occurs because as new firms enter, other firms lose customersand profit. Note that this is a negative externality.c. Depending on which externality is larger, a monopolistically competitive market could have toofew or too many products.5. In the News: Insufficient Variety as a Market Failurea. Firms may insufficiently service consumers with unusual preferences in markets with large fixedcostsb. This article from Slate describes how some consumers get left out of the market because of thehigh fixed costs associated with creating additional varieties of a product.III. AdvertisingA. The Debate over Advertising1. The Critique of Advertisinga. Firms advertise to manipulate people's tastes.b. Advertising impedes competition because it increases the perception of product differentiationand fosters brand loyalty. This means that consumers will be less concerned with pricedifferences among similar goods.2. The Defense of Advertisinga. Firms use advertising to provide information to consumers.b. Advertising fosters competition because it allows consumers to be better informed about all ofthe firms in the market.3. Case Study: Advertising and the Price of Eyeglassesa. In the United States during the 1960s, states differed on whether or not they allowed advertisingfor optometrists.b. In the states that prohibited advertising, the average price paid for a pair of eyeglasses in 1963was $33; in states that allowed advertising, the average price was $26 (a difference of more than20%).B. Advertising as a Signal of Quality1. The willingness of a firm to spend a large amount of money on advertising may be a signal toconsumers about the quality of the product being offered.2. Example: Kellogg and Post have each developed a new cereal that would sell for $3 per box. (Assumethat the marginal cost of producing the cereal is zero.) Each company knows that if it spends $10million on advertising, it will get one million new consumers to try the product. If consumers like the product, they will buy it again.a. Post has discovered through market research that its new cereal is not very good. After buying itonce, consumers would not likely buy it again. Thus, it will only earn $3 million in revenue, whichwould not be enough to pay for the advertising. Therefore, it does not advertise.b. Kellogg knows that its cereal is great. Each person that buys it will likely buy one box per monthfor the next year. Therefore, its sales would be $36 million, which is more than enough to justifythe advertisement.c. By its willingness to spend money on advertising, Kellogg signals to consumers the quality of itscereal.3. Note that the content of the advertisement is unimportant; what is important is that consumersknow that the advertisements are expensive.C. Brand Names1. In many markets there are two types of firms; some firms sell products with widely recognized brandnames while others sell generic substitutes.2. Critics of brand names argue that they cause consumers to perceive differences that do not reallyexist.3. Economists have defended brand names as a useful way to ensure that goods are of high quality.a. Brand names provide consumers with information about quality when quality cannot be judgedeasily in advance of purchase.b. Brand names give firms an incentive to maintain high quality, because firms have a financialstake in maintaining the reputation of their brand names.SOLUTIONS TO TEXT PROBLEMS:Quick Quizzes1. Oligopoly is a market structure in which only a few sellers offer similar or identical products.Examples include the market for breakfast cereals and the world market for crude oil. Monopolisticcompetition is a market structure in which many firms sell products that are similar but not identical.Examples include the markets for novels, movies, restaurant meals, and computer games.2. The three key attributes of monopolistic competition are: (1) there are many sellers; (2) each firmproduces a slightly different product; and (3) firms can enter or exit the market freely.Figure 1 shows the long-run equilibrium in a monopolistically competitive market. This equilibriumdiffers from that in a perfectly competitive market because price exceeds marginal cost and the firmdoes not produce at the minimum point of average total cost but instead produces at less than theefficient scale.Figure 13. Advertising may make markets les s competitive if it manipulates people’s tastes rather than beinginformative. Advertising may give consumers the perception that there is a greater differencebetween two products than really exists. That makes the demand curve for a product more inelastic,so the firms can then charge greater markups over marginal cost. However, some advertising couldmake markets more competitive because it sometimes provides useful information to consumers,allowing them to take advantage of price differences more easily. Advertising also facilitates entrybecause it can be used to inform consumers about a new product. In addition, expensive advertisingcan be a signal of quality.Brand names may be beneficial because they provide information to consumers about the quality ofgoods. They also give firms an incentive to maintain high quality, since their reputations areimportant. But brand names may be criticized because they may simply differentiate products thatare not really different, as in the case of drugs that are identical with the brand-name drug selling at amuch higher price than the generic drug.Questions for Review1. The three attributes of monopolistic competition are: (1) there are many sellers; (2) each sellerproduces a slightly different product; and (3) firms can enter or exit the market without restriction.Monopolistic competition is like monopoly because firms face a downward-sloping demand curve, soprice exceeds marginal cost. Monopolistic competition is like perfect competition because, in the longrun, price equals average total cost, as free entry and exit drive economic profit to zero.2. In Figure 2, a firm has demand curve D1 and marginal-revenue curve MR1. The firm is making profitsbecause at quantity Q1, price (P1) is above average total cost (ATC). Those profits induce other firmsto enter the industry, causing the demand curve to shift to D2 and the marginal-revenue curve to shiftto MR2. The result is a decline in quantity to Q2, at which point the price (P2) equals average total cost (ATC), so profits are now zero.Figure 23. Figure 3 shows the long-run equilibrium in a monopolistically competitive market. Price equalsaverage total cost. Price is above marginal cost.Figure 34. Because, in equilibrium, price is above marginal cost, a monopolistic competitor produces too littleoutput. But this is a hard problem to solve because: (1) the administrative burden of regulating the large number of monopolistically competitive firms would be high; and (2) the firms are earning zero economic profits, so forcing them to price at marginal cost means that firms would lose money unless the government subsidized them.5. Advertising might reduce economic well-being because it manipulates people's tastes and impedescompetition by making products appear more different than they really are. But advertising might increase economic well-being by providing useful information to consumers and fosteringcompetition.6. Advertising with no apparent informational content might convey information to consumers if itprovides a signal of quality. A firm will not be willing to spend much money advertising a low-qualitygood, but may be willing to spend significantly more to advertise a high-quality good.7. The two benefits that might arise from the existence of brand names are: (1) brand names provideconsumers information about quality when quality cannot be easily judged in advance; and (2) brandnames give firms an incentive to maintain high quality to maintain the reputation of their brandnames.Quick Check Multiple Choice1. b2. d3. a4. d5. a6. cProblems and Applications1. a. Tap water is a monopoly because there is a single seller of tap water to a household .b. Bottled water is a monopolistically competitive market. There are many sellers of bottled water,but each firm tries to differentiate its own brand from the rest.c. The cola market is an oligopoly. There are only a few firms that control a large portion of themarket.d. The beer market is an oligopoly. There are only a few firms that control a large portion of themarket.2. a. The market for wooden #2 pencils is perfectly competitive because pencils by any manufacturerare identical and there are a large number of manufacturers.b. The market for copper is perfectly competitive, because all copper is identical and there are alarge number of producers.c. The market for local electricity service is monopolistic because it is a natural monopoly—it ischeaper for one firm to supply all the output.d. The market for peanut butter is monopolistically competitive because different brand namesexist with different quality characteristics.e. The market for lipstick is monopolistically competitive because lipstick from different firmsdiffers slightly, but there are a large number of firms that can enter or exit without restriction.3. a. A firm in monopolistic competition sells a differentiated product from its competitors.b. A firm in monopolistic competition has marginal revenue less than price.c. Neither a firm in monopolistic competition nor in perfect competition earns economic profit inthe long run.d. A firm in perfect competition produces at the minimum average total cost in the long run.e. Both a firm in monopolistic competition and a firm in perfect competition equate marginalrevenue and marginal cost.f. A firm in monopolistic competition charges a price above marginal cost.4. a. Both a firm in monopolistic competition and a monopoly firm face a downward-sloping demandcurve.b. Both a firm in monopolistic competition and a monopoly firm have marginal revenue that is lessthan price.c. A firm in monopolistic competition faces the entry of new firms selling similar products.d. A monopoly firm earns economic profit in the long run.e. Both a firm in monopolistic competition and a monopoly firm equate marginal revenue andmarginal cost.f. Neither a firm in monopolistic competition nor a monopoly firm produces the socially efficientquantity of output.5. a. The firm is not maximizing profit. For a firm in monopolistic competition, price is greater thanmarginal revenue. If price is below marginal cost, marginal revenue must be less than marginalcost. Thus, the firm should reduce its output to increase its profit.b. The firm may be maximizing profit if marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. However, thefirm is not in long-run equilibrium because price is less than average total cost. In this case, firms will exit the industry and the demand facing the remaining firms will rise until economic profit is zero.c. The firm is not maximizing profit. For a firm in monopolistic competition, price is greater thanmarginal revenue. If price is equal to marginal cost, marginal revenue must be less than marginal cost. Thus, the firm should reduce its output to increase its profit.d. The firm could be maximizing profit if marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. The firm is inlong-run equilibrium because price is equal to average total cost. Therefore, the firm is earningzero economic profit.6. a. Figure 4 illustrates the market for Sparkle toothpaste in long-run equilibrium. The profit-maximizing level of output is Q M and the price is P M.Figure 4b. Sparkle's profit is zero, because at quantity Q M, price equals average total cost.c. The consumer surplus from the purchase of Sparkle toothpaste is areas A + B. The efficient levelof output occurs where the demand curve intersects the marginal-cost curve, at Q C. Thedeadweight loss is area C, the area above marginal cost and below demand, from Q M to Q C.d. If the government forced Sparkle to produce the efficient level of output, the firm would losemoney because average total cost would exceed price, so the firm would shut down. If thathappened, Sparkle's customers would earn no consumer surplus.7. a. As N rises, the demand for each firm’s product falls. As a result, each firm’s demand curve willshift left.b. The firm will produce where MR = MC:100/N– 2Q = 2QQ = 25/Nc. 25/N = 100/N–PP = 75/Nd. Total revenue = P Q = 75/N 25/N = 1875/N2Total cost = 50 + Q2 = 50 + (25/N)2 = 50 + 625/N2Profit = 1875/N2– 625/N2– 50 = 1250/N2– 50e. In the long run, profit will be zero. Thus:1250/N2– 50 = 01250/N2 = 50N = 58. Figure 5 shows the cost, marginal revenue and demand curves for the firm under both conditions.Figure 5a. The price will fall from P MC to the minimum average total cost (P C) when the market becomesperfectly competitive.b. The quantity produced by a typical firm will rise to Q C, which is at the efficient scale of output.c. Average total cost will fall as the firm increases its output to the efficient scale.d. Marginal cost will rise as output rises. Marginal cost is now equal to price.e. Profit will not change. In either case, the market will move to long-run equilibrium where allfirms will earn zero economic profit.9. a. A family-owned restaurant would be more likely to advertise than a family-owned farm becausethe output of the farm is sold in a perfectly competitive market, in which there is no reason toadvertise, while the output of the restaurant is sold in a monopolistically competitive market.b. A manufacturer of cars is more likely to advertise than a manufacturer of forklifts because thereis little difference between different brands of industrial products like forklifts, while there aregreater perceived differences between consumer products like cars. The possible return toadvertising is greater in the case of cars than in the case of forklifts.c. A company that invented a very comfortable razor is likely to advertise more than a companythat invented a less comfortable razor that costs the same amount to make because thecompany with the very comfortable razor will get many repeat sales over time to cover the cost of the advertising, while the company with the less comfortable razor will not.10. a. Figure 6 shows Sleek’s demand, marginal-revenue, marginal-cost, and average-total-cost curves.The firm will maximize profit at an output level of Q * and a price of P *. The shaded are shows the firm’s profits.Figure 6b. In the long run, firms will enter, shifting the demand for Sleek’s product to the left. Its price andoutput will fall. Firms will enter until profits are equal to zero (as shown in Figure 7).Figure 7c. As consumers become more focused on the stylistic differences in brands, they will be lessfocused on price. This will make the demand for each firm’s products more price inelastic. The demand curves may become relatively steeper, allowing Sleek to charge a higher price. If these stylistic features cannot be copied, they may serve as a barrier to entry and allow Sleek to earn profit in the long run.d. A firm in monopolistic competition produces where marginal revenue is greater than zero. Thismeans that firm must be operating on the elastic portion of its demand curve.。

1.犯罪率的下降可能是因为经济增长,治安变好,但史蒂芬·列维特却说是因为出生率下降,因为堕胎合法化了,那些早孕早育的叛逆女孩儿不再生孩子了。

(X和Y有正相关关系,并不能说明X是Y的起因,或X和Y有因果关系。

)2.出售房屋时候的房产经纪人会获取佣金,但可能不会把你的房子以最高价卖出,因为他佣金的百分比(除去佣金中给公司的部分),只有1.5%左右,你房子比合理价格高的部分带来的收益,不会过度增加他的佣金。

而他却要为此付出很多时间和精力等等。

这个由他代理的房子卖价和自己房子卖价的差别可以看出。

3.选举中,候选人投入金钱数量几乎不会发生任何作用。

事实上,即使一位候选人将自己的竞选预算消减一半,他所损失的选票数量也只有1%,而那些很可能会输掉的候选人,即使增加一倍的投资,他们也只能多赢得1%的选票。

4.和《怪诞行为学》一样,如果把单纯的社会道德动机与市场挂钩,往往会很terrible。

例如,育儿园里面家长晚接孩子,都会有歉意,如果你把它变成罚款,家长就会肆无忌惮的迟到。

再变回来,社会规范也就不起作用了,没有当初的直接的社会规范作用好。

5.史蒂芬·列维特居然能用方程式分析考试答案,分析出哪些老师在考试中作弊了,修改了答案。

6.甜饼的故事:每天早上,在楼层放上甜饼和收钱的盒子,下午定时过来取走未卖完的甜饼和盒子。

发现:天气好>天气差;小公司>大公司;公司士气好>士气差;低等级职工>中高级职工;国庆节,劳动节,哥伦布日>其他节日(前者让员工多享受一天休假,后者员工内心多会充满焦虑)7.信息不对称:信息拥有者往往利用自己的优势获取利益。

如房地产经纪人,往往会告诉你,你的房子有多难卖出(市场经验),或者你出的价格多难买到好房子,从而获得操纵的权利。

8.对付贩毒团伙的最直接方式:告诉群众,贩毒团伙靠此赚了大量的钱。

9.贩毒团伙的内部运行机构和大公司或者麦当劳没什么区别,通过特许加盟的方式进入大组织,向该组织的“董事会”负责,并交纳20%的收入给“董事会”,“店长”手下有3个副手:执行官(保护帮派成员的人生安全),财务官(管理帮派的资产),运营官(跟供应商沟通,实现毒品和货物的转移和支付)。

《魔鬼经济学(套装4本)》读后感_1300字《魔鬼经济学(套装4本)》读后感1300字第一本:惊艳。

把堕胎合法化和犯罪率联系到一起,这个脑洞真的绝了。

也对我启发了一个关于研究大数据的思路——寻找同一时间区间内有趋势性变化的数据,定性上提出相关性假设,然后再用回归做定量上的显著性分析——以此来作证假设。

虽然看了很多后续文献证明其实堕胎和犯罪率的相关性并没有那么(统计意义上)的显著,不过这个分析,相较于枪支管理啊什么的我认为才更有长期的影响意义。

但是人口统计数据庞大且复杂,还要对多种因素做控制变量处理也很难取得精确的模型,所以只要有一定显著性其实就很能说明问题了。

然后关于作弊机读卡的序列分析也好惊艳——对不同选项进行赋值,然后组合成系列串,在丛中分析查找规律——不得不说能开这种脑洞作者肯定是学识相当渊博了。

毒贩和可卡因分析这一部分也有很好的启示——任何社会问题或是显示数据分析,脱离了真是环境的话就毫无意义——所以做调查一定要身体力行,深入研究地区,深入研究对象才行。

简言之,作者在很多普通人日常经常听说的事情里发现了最基本的经济学原理,并通俗的解释给大家,这样的经济学读物来10本!(感觉本书的目的不是纯教学性的,所以做这并没有给出回归模型,或是数据表或是正态分布查指标之类的,而只是对数据分析的逻辑给予讲解,我认为这样足够了,有兴趣深入了解的可以去搜作者的论文,不过港真,那些模型十分复杂。

一般人不想看的)第二本:个人对环保毫无兴趣(对,就是这么诚实)所以前面看的有点昏昏欲睡,不过当话题开始和经济学扯上关系时,我又被惊艳到了。

是啊,成本控制才是王道啊,不过政客当然不这么认为。

最喜欢的还是妓女经济学——其实就是把经济学十大原理(的大部分)放到了大家一般不放上台面讲的市场里——嗯,无论什么市场,果然原理都是可证的呢。

恐怖分子章节和第四本呼应了一下,个中脑洞也是让人佩服。

虽然因话题敏感性作者也无法给出具体的寻找恐怖分子的参数,不过启发还是有的——寻找数据相似。

《魔鬼经济学》书评杨帅龙药学院33920152204030 《魔鬼经济学》的作者之一是芝加哥大学经济学院终身教授史蒂芬·列维特,是2003年美国克拉克奖获得者,被誉为“当今美国40岁以下最负盛名的经济学家”,他的声誉得到了整个经济学界的公认,另一作者史蒂芬·都伯纳也为著名的经济学家及作家。

该书一经上市就风靡全球。

在本书中,史蒂芬·列维特和史蒂芬·都伯纳取材日常生活,以经济学的方式来探索日常事物背后的世界:念书给婴儿听会不会使他日后成为一个好学生?游泳池比枪支还危险?贩毒集团的结构其实和麦当劳的组织很像,而且基层员工和小弟都没赚头,钱都进了总裁和大哥的口袋;父母教养方式的差异对孩子影响不大等。

《魔鬼经济学》中确立了一个有悖于传统智慧的观点:如果说伦理道德代表了我们心目中理想的社会运行模式的话,那么经济学就是在向我们描述这个社会到底是如何运行的。

同时,作者也用千方百计搜集来的各种数据告诉读者真实的世界是怎样的。

著名的书评人兰兹·伯格把《魔鬼经济学》比喻成一部侦探小说,说自己在阅读此书的过程中一直都“屏住呼吸”,生怕一呼一吸之间,吹跑书中的那股灵气。

在他看来,《魔鬼经济学》的每一个章节都包含了一本一流侦探小说的所有元素。

只不过列维特所要侦破的最终目标不是“找到凶手”,而是“揭开真实世界的伪装”。

《魔鬼经济学》书中的几乎每一个字都是对传统智慧的颠覆,他的许多发现被认为是惊世骇俗的,有些甚至会为他引来杀身之祸。

因此,不论从哪个角度来说,这都是一本会让人眼界一新的书。

全书总共分为六章。

第一章:学校老师跟相扑运动员之间有何共同之处?讲述了由于不同动机(经济动机、道德动机、社会动机),很多人都会撒谎,只是如果不去深处分析的话,你是很难去抓到的。

书中列出学校老师为了学生能有更好的联考成绩,会在改卷上做手脚;相扑运动员为了能有更好的名次,私下会有交易等,突出了激励的作用。

另辟蹊径--《魔鬼经济学4》序一连4本,一鼓作气,这套书全看完了,有意思的事情一本比一本少,前三本还有东西可以写一写,而今天合上书的时候,心想天啊总算看完了。

这本书是列维特和都博纳的blog文章的精选,所以算是杂文集,由于翻译让人有时候读起来感觉费劲以及很多的内容我是不感兴趣的,但是又生怕错过些什么有意思的事情,于是才会出现以上一幕。

一半一半由于前三本书读起来很流畅,但是这一本读起来很费劲,我想这应该是翻译的问题了。

作者选择了用经济学来解释犯罪行为,来解释很多现象的成因,由于角度不同,所以很容易招致争议。

想想因为很多经济学家的研究都是商业与人的事情,背后会有很多企业资助,如果研究结果不利于企业的利益的时候,我相信他的作品的是无法公之于众的,即便美国有一个民主与自由的环境,但是如果这个事情会损害大财阀的商业利益,事情就一样了。

虽然都是解释事情发生的机理,但是未必是要追求事实的真相,真相太残酷,于是只要解释得过去就好了。

犯罪经济学不是,无论真相残酷与否,有无损害财阀利益,列维特都可以发表,毕竟他在这行是专家,且列维特明确的说:不服来辩。

甚至连卡梅伦都看列维特不顺眼,不得不说,列维特对英国医改开出的药方倒是被我们国家给吸取了,就是每月发一定额度的医保金,一年超过一定额度后才能申请统筹报销。

只要是这个福利是要花钱的,浪费钱的人以及监督的发生的费用就会大大降低。

在《魔鬼经济学2》中提到了一个原本做兼职的应召女郎,后来发现专业做应召女郎收入比做程序员多多了,但是和其他人不一样的是,她学过经济学,清楚的认识到与人吃饭是个机会成本,约会前获得完全的信息降低风险,甚至找了第三方的核实公司并录入数据库,查看约会人的诚信度,由于专业度强(指的是她锁定都是想得到几小时解脱的人)获得了良好的信誉可以发生重复博弈。

现在的她已经重新申请了一家大学念书,考取了房地产业的执照,也过上了财务自由的自由职业者的生活。

结语到底什么是经济学?它是数学,还是社会学,抑或是心理学?反正心理学家是拿到过诺贝尔经济学奖,数学家也拿过。

微观经济学原理曼昆名词解释稀缺性(scarcity):社会资源的有限性。

经济学(economics):研究社会如何管理自己的稀缺资源。

效率(efficiency):社会能从其稀缺资源中得到最多东西的特性。

平等(equality):经济成果在社会成员中公平分配的特性。

机会成本(opportunity cost):为了得到某种东西所必须放弃的东西。

理性人(rational people):系统而有目的地尽最大努力实现起目标的人。

边际变动(marginal change):对行动计划微小的增量调整。

激励(incentive):引起一个人做出某种行为的某种东西。

市场经济(market economy):当许多企业和家庭在物品与劳务市场上相互交易时,通过他们的分散决策配置资源的经济。

产权(property rights):个人拥有并控制稀缺资源的能力。

市场失灵(market failure):市场本身不能有效配置资源的情况。

外部性(externality):一个人的行为对旁观者福利的影响。

市场势力(market power):一个经济活动者(或经济活动者的一个小集团)对市场价格有显著影响的能力。

生产率(productivity):一个工人一小时所生产的物品与劳务量。

通货膨胀(inflation):经济中物价总水平的上升。

经济周期(business cycle):就业和生产等经济活动的波动(就是生产这类经济活动的波动。

)循环流向图(circular-flow diagram):一个说明货币如何通过市场在家庭与企业之间流动的直观经济模型。

生产可能性边界(production possibilities frontier):表示一个经济在可得到的生产要素与生产技术既定时所能生产的产量的各种组合的图形。

微观经济学(microeconomics):研究家庭和企业如何做出决策,以及它们在市场上的相互交易。

宏观经济学(macroeconomics):研究整体经济现象,包括通货膨胀、失业和经济增长。

Freakonomicsby Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. DubnerINTRODUCTION: The Hidden Side of Everything5Anyone living in the United States in the early 1990s and paying even a whisper of attention to the nightly news or a daily paper could be forgiven for having been scaredout of his skin.The culprit was crime. It had been rising relentlessly—a graph plotting the crime rate in any American city over recent decades looked like a ski slope in profile—and it seemed10now to herald the end of the world as we knew it. Death by gunfire, intentional andotherwise, had become commonplace. So too had carjacking and crack dealing, robberyand rape. Violent crime was a gruesome, constant companion. And things were about toget even worse. Much worse. All the experts were saying so.15The cause was the so-called superpredator. For a time, he was everywhere. Glowering from the cover of newsweeklies. Swaggering his way through foot-thick governmentreports. He was a scrawny, big-city teenager with a cheap gun in his hand and nothing inhis heart but ruthlessness. There were thousands out there just like him, we were told, ageneration of killers about to hurl the country into deepest chaos.20In 1995 the criminologist James Alan Fox wrote a report for the U.S. attorney general that grimly detailed the coming spike in murders by teenagers. Fox proposed optimisticand pessimistic scenarios. In the optimistic scenario, he believed, the rate of teenhomicides would rise another 15 percent over the next decade; in the pessimisticscenario, it would more than double. “The next crime wave will get so bad,” he said,“that it will make 1995 look like the good old days.”25Other criminologists, political scientists, and similarly learned forecasters laid out the same horrible future, as did President Clinton. “We know we’ve got about six years toturn this juvenile crime thing around,” Clinton said, “or our country is going to be livingwith chaos. And my successors will not be giving speeches about the wonderful30opportunities of the global economy; they’ll be trying to keep body and soul together forpeople on the streets of these cities.” The smart money was plainly on the criminals.And then, instead of going up and up and up, crime began to fall. And fall and fall and fall some more. The crime drop was startling in several respects. It was ubiquitous, withevery category of crime falling in every part of the country. It was persistent, withincremental decreases year after year. And it was entirely unanticipated—especially by35the very experts who had been predicting the opposite.The magnitude of the reversal was astounding. The teenage murder rate, instead of rising 100 percent or even 15 percent as James Alan Fox had warned, fell more than 50 percentwithin five years. By 2000 the overall murder rate in the United States had dropped to its40lowest level in thirty-five years. So had the rate of just about every other sort of crime,from assault to car theft.Even though the experts had failed to anticipate the crime drop—which was in fact well under way even as they made their horrifying predictions—they now hurried to explain it.Most of their theories sounded perfectly logical. It was the roaring 1990s economy, they45said, that helped turn back crime. It was the proliferation of gun control laws, they said. Itwas the sort of innovative policing strategies put into place in New York City, wheremurders would fall from 2,245 in 1990 to 596 in 2003.These theories were not only logical; they were also encouraging, for they attributed the crime drop to specific and recent human initiatives. If it was gun control and clever police50strategies and better-paying jobs that quelled crime—well then, the power to stopcriminals had been within our reach all along. As it would be the next time, God forbid,that crime got so bad.These theories made their way, seemingly without question, from the experts’ mouths to journalists’ ears to the public’s mind. In short course, they became conventional wisdom.55There was only one problem: they weren’t true.There was another factor, meanwhile, that had greatly contributed to the massive crime drop of the 1990s. It had taken shape more than twenty years earlier and concerned ayoung woman in Dallas named Norma McCorvey.Like the proverbial butterfly that flaps its wings on one continent and eventually causes a hurricane on another, Norma McCorvey dramatically altered the course of events without60intending to. All she had wanted was an abortion. She was a poor, uneducated, unskilled,alcoholic, drug-using twenty-one-year-old woman who had already given up two childrenfor adoption and now, in 1970, found herself pregnant again. But in Texas, as in all but afew states at that time, abo rtion was illegal. McCorvey’s cause came to be adopted by65people far more powerful than she. They made her the lead plaintiff in a class-actionlawsuit seeking to legalize abortion. The defendant was Henry Wade, the Dallas Countydistrict attorney. The case ultimately made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, by which timeMcCorvey’s name had been disguised as Jane Roe. On January 22, 1973, the court ruledin favor of Ms. Roe, allowing legalized abortion throughout the country. By this time, of70course, it was far too late for Ms. McCorvey/Roe to have her abortion. She had givenbirth and put the child up for adoption. (Years later she would renounce her allegiance tolegalized abortion and become a pro-life activist.)So how did Roe v. Wade help trigger, a generation later, the greatest crime drop in recorded history?75As far as crime is concerned, it turns out that not all children are born equal. Not even close. Decades of studies have shown that a child born into an adverse familyenvironment is far more likely than other children to become a criminal. And the millionsof women most likely to have an abortion in the wake of Roe v. Wade—poor, unmarried,and teenage mothers for whom illegal abortions had been too expensive or too hard to80get—were often models of adversity. They were the very women whose children, if born,would have been much more likely than average to become criminals. But because ofRoe v. Wade, these children weren’t being born. This powerful cause would have adrastic, distant effect: years later, just as these unborn children would have entered theircriminal primes, the rate of crime began to plummet.85It wasn’t gun control or a strong economy or new police strategies that finally blunted the American crime wave. It was, among other factors, the reality that the pool of potentialcriminals had dramatically shrunk.Now, as the crime-drop experts (the former crime doomsayers) spun their theories to the media, how many times did they cite legalized abortion as a cause?90Zero.It is the quintessential blend of commerce and camaraderie: you hire a real-estate agent to sell your home.95She sizes up its charms, snaps some pictures, sets the price, writes a seductive ad, shows the house aggressively, negotiates the offers, and sees the deal through to its end. Sure,it’s a lot of work, but she’s getting a nice cut. On the sale of a $300,000 house, a typical 6percent agent fee yields $18,000. Eighteen thousand dollars, you say to yourself: that’s alot of money. But you also tell yourself that you never could have sold the house for100$300,000 on your own. The agent knew how to—what’s that phrase she used?—“maximize the house’s value.” She got you top dollar, right?Right?A real-estate agent is a different breed of expert than a criminolo-gist, but she is every bitthe expert. That is, she knows her field far better than the layman on whose behalf she is105acting. She is better informed about the house’s value, the state of the housing market,even the buyer’s frame of mind. You depend on her for this information. That, in fact, iswhy you hired an expert.As the world has grown more specialized, countless such experts have made themselves similarly indispensable. Doctors, lawyers, contractors, stockbrokers, auto mechanics,mortgage brokers, financial planners: they all enjoy a gigantic informational advantage.110And they use that advantage to help you, the person who hired them, get exactly whatyou want for the best price.Right?It would be lovely to think so. But experts are human, and humans respond to incentives. 115How any given expert treats you, therefore, will depend on how that expert’s incentivesare set up. Sometimes his incentives may work in your favor. For instance: a study ofCalifornia auto mechanics found they often passed up a small repair bill by letting failingcars pass emissions inspections—the reason being that lenient mechanics are rewardedwith repeat business. But in a different case, an expert’s incentives may work against120you. In a medical study, it turned out that obstetricians in areas with declining birth ratesare much more likely to perform cesarean-section deliveries than obstetricians in growingareas—suggesting that, when business is tough, doctors try to ring up more expensiveprocedures.It is one thing to muse about experts’ abusing their position and another to prove it. The 125best way to do so would be to measure how an expert treats you versus how he performsthe same service for himself. Unfortunately a surgeon doesn’t operate on himself. Nor ishis medical file a matter of public record; neither is an auto mechanic’s repair log for hisown car.Real-estate sales, however, are a matter of public record. And real-estate agents often do 130sell their own homes. A recent set of data covering the sale of nearly 100,000 houses insuburban Chicago shows that more than 3,000 of those houses were owned by the agentsthemselves.Before plunging into the data, it helps to ask a question: what is the real-estate agent’s incentive when she is selling her own home? Simple: to make the best deal possible.135Presumably this is also your incentive when you are selling your home. And so yourincentive and the real-estate agent’s incentive would seem to be nicely aligned. Hercommission, after all, is based on the sale price.But as incentives go, commissions are tricky. First of all, a 6 percent real-estate commission is typically split between the seller’s agent and the buyer’s. Each agent then140kicks back half of her take to the agency. Which means that only 1.5 percent of thepurchase price goes directly into your agent’s pocket.So on the sale of your $300,000 house, her personal take of the $18,000 commission is $4,500. Still not bad, you say. But what if the house was actually worth more than$300,000? What if, with a little more effort and patience and a few more newspaper ads,145she could have sold it for $310,000? After the commission, that puts an additional $9,400in your pocket. But the agent’s additional share—her personal 1.5 percent of the extra$10,000—is a mere $150. If you earn $9,400 while she earns only $150, maybe yourincentives aren’t aligned after all. (Especially when she’s the one paying for the ads anddoing all the work.) Is the agent willing to put out all that extra time, money, and energy150for just $150?There’s one way to find out: measure the difference between the sales data for houses that belong to real-estate agents themselves and the houses they sold on behalf of clients.Using the data from the sales of those 100,000 Chicago homes, and controlling for anynumber of variables—location, age and quality of the house, aesthetics, and so on—it155turns out that a real-estate agent keeps her own home on the market an average of tendays longer and sells it for an extra 3-plus percent, or $10,000 on a $300,000 house.When she sells her own house, an agent holds out for the best offer; when she sells yours,she pushes you to take the first decent offer that comes along. Like a stockbrokerchurning commissions, she wants to make deals and make them fast. Why not? Her share 160of a better offer—$150—is too puny an incentive to encourage her to do otherwise.Of all the truisms about politics, one is held to be truer than the rest: money buys elections. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Michael Bloomberg, Jon Corzine—these are but a165few recent, dramatic examples of the truism at work. (Disregard for a moment thecontrary examples of Howard Dean, Steve Forbes, Michael Huffington, and especiallyThomas Golisano, who over the course of three gubernatorial elections in New Yorkspent $93 million of his own money and won 4 percent, 8 percent, and 14 percent,respectively, of the vote.) Most people would agree that money has an undue influence on 170elections and that far too much money is spent on political campaigns.Indeed, election data show it is true that the candidate who spends more money in a campaign usually wins. But is money the cause of the victory?It might seem logical to think so, much as it might have seemed logical that a booming 1990s economy helped reduce crime. But just because two things are correlated does not 175mean that one causes the other. A correlation simply means that a relationship existsbetween two factors—let’s call them X and Y—but it tells you nothing about thedirection of that relationship. It’s possible that X causes Y; it’s also possible that Ycauses X; and it may be that X and Y are both being caused by some other factor, Z.Think about this correlation: cities with a lot of murders also tend to have a lot of police 180officers. Consider now the police/murder correlation in a pair of real cities. Denver andWashington, D.C., have about the same population—but Washington has nearly threetimes as many police as Denver, and it also has eight times the number of murders.Unless you have more information, however, it’s hard to say what’s causing what.Someone who didn’t know better might contemplate these figures and conclude that it is185all those extra police in Washington who are causing the extra murders. Such waywardthinking, which has a long history, generally provokes a wayward response. Consider thefolktale of the czar who learned that the most disease-ridden province in his empire wasalso the province with the most doctors. His solution? He promptly ordered all thedoctors shot dead.190Now, returning to the issue of campaign spending: in order to figure out the relationship between money and elections, it helps to consider the incentives at play in campaignfinance. Let’s say you are the kind of person who might contribute $1,000 to a candidate.Chances are you’ll give the money in one of two situations: a close race, in which youthink the money will influence the outcome; or a campaign in which one candidate is a195sure winner and you would like to bask in reflected glory or receive some future in-kindconsideration. The one candidate you won’t contribute to is a sure loser. (Just ask anypresidential hopeful who bombs in Iowa and New Hampshire.) So front-runners andincumbents raise a lot more money than long shots. And what about spending thatmoney? Incumbents and front-runners obviously have more cash, but they only spend a200lot of it when they stand a legitimate chance of losing; otherwise, why dip into a warchest that might be more useful later on, when a more formidable opponent appears?Now picture two candidates, one intrinsically appealing and the other not so. The appealing candidate raises much more money and wins easily. But was it the money thatwon him the votes, or was it his appeal that won the votes and the money?205That’s a crucial question but a very hard one to answer. Voter appeal, after all, isn’t easy to quantify. How can it be measured?It can’t, really—except in one special case. The key is to measure a candidate against…himself. That is, Candidate A today is likely to be similar to Candidate A two orfour years hence. The same could be said for Candidate B. If only Candidate A ranagainst Candidate B in two consecutive elections but in each case spent different amounts 210of money. Then, with the candidates’ appeal more or less constant, we could measure themoney’s impact.As it turns out, the same two candidates run against each other in consecutive elections all the time—indeed, in nearly a thousand U.S. congressional races since 1972. What dothe numbers have to say about such cases?215Here’s the surprise: the amount of money spent by the candidates hardly matters at all. A winning candidate can cut his spending in half and lose only 1 percent of the vote.Meanwhile, a losing candidate who doubles his spending can expect to shift the vote in his favor by only that same 1 percent. What really matters for a political candidate is not220how much you spend; what matters is who you are. (The same could be said—and will besaid, in chapter 5—about parents.) Some politicians are inherently attractive to voters andothers simply aren’t, and no amount of money can do much about it. (Messrs. Dean,Forbes, Huffington, and Golisano already know this, of course.)And what about the other half of the election truism—that the amount of money spent on campaign finance is obscenely huge? In a typical election period that includes campaigns225for the presidency, the Senate, and the House of Representatives, about $1 billion is spentper year—which sounds like a lot of money, unless you care to measure it againstsomething seemingly less important than democratic elections.It is the same amount, for instance, that Americans spend every year on chewing gum. 230This isn’t a book about the cost of chewing gum versus campaign spending per se, or about disingenuous real-estate agents, or the impact of legalized abortion on crime. It willcertainly address these scenarios and dozens more, from the art of parenting to the235mechanics of cheating, from the inner workings of the Ku Klux Klan to racialdiscrimination on The Weakest Link. What this book is about is stripping a layer or twofrom the surface of modern life and seeing what is happening underneath. We will ask alot of questions, some frivolous and some about life-and-death issues. The answers mayoften seem odd but, after the fact, also rather obvious. We will seek out these answers inthe data—whether those data come in the form of schoolchildren’s test scores or New240York City’s crime statistics or a crack dealer’s financial records. (Often we will takeadvantage of patterns in the data that were incidentally left behind, like an a irplane’ssharp contrail in a high sky.) It is well and good to opine or theorize about a subject, ashumankind is wont to do, but when moral posturing is replaced by an honest assessment245of the data, the result is often a new, surprising insight.Morality, it could be argued, represents the way that people would like the world to work—whereas economics represents how it actually does work. Economics is above alla science of measurement. It comprises an extraordinarily powerful and flexible set oftools that can reliably assess a thicket of information to determine the effect of any one250factor, or even the whole effect. That’s what “the economy” is, after all: a thicket ofinformation about jobs and real estate and banking and investment. But the tools ofeconomics can be just as easily applied to subjects that are more—well, more interesting.This book, then, has been written from a very specific worldview, based on a few fundamental ideas:255Incentives are the cornerstone of modern life. And understanding them—or, often, ferreting them out—is the key to solving just about any riddle, from violent crime tosports cheating to online dating.The conventional wisdom is often wrong.Crime didn’t keep soaring in the 1990s, money alone doesn’t win elections, and—surprise—drinking eight glasses of water a day has260never actually been shown to do a thing for your health. Conventional wisdom is oftenshoddily formed and devilishly difficult to see through, but it can be done.Dramatic effects often have distant, even subtle, causes. The answer to a given riddle is not always right in front of you. Norma McCorvey had a far greater impact on crime thandid the combined forces of gun control, a strong economy, and innovative police265strategies. So did, as we shall see, a man named Oscar Danilo Blandon, aka the JohnnyAppleseed of Crack.“Experts”—from criminologists to real-estate agents—use their informational advantage to serve their own agenda. However, they can be beat at their own game. And in the faceof the Internet, their informational advantage is shrinking every day—as evidenced by,270among other things, the falling price of coffins and life-insurance premiums.Knowing what to measure and how to measure it makes a complicated world much less so. If you learn how to look at data in the right way, you can explain riddles thatotherwise might have seemed impossible. Because there is nothing like the sheer powerof numbers to scrub away layers of confusion and contradiction.275So the aim of thi s book is to explore the hidden side of…everything. This may occasionally be a frustrating exercise. It may sometimes feel as if we are peering at theworld through a straw or even staring into a funhouse mirror; but the idea is to look atmany different scenarios and examine them in a way they have rarely been examined. Insome regards, this is a strange concept for a book. Most books put forth a single theme,280crisply expressed in a sentence or two, and then tell the entire story of that theme: thehistory of salt; the fragility of democracy; the use and misuse of punctuation. This bookboasts no such unifying theme. We did consider, for about six minutes, writing a bookthat would revolve around a single theme—the theory and practice of appliedmicroeconomics, anyone?—but opted instead for a sort of treasure-hunt approach. Yes,285this approach employs the best analytical tools that economics can offer, but it alsoallows us to follow whatever freakish curiosities may occur to us. Thus our invented fieldof study: Freakonomics. The sort of stories told in this book are not often covered inEcon. 101, but that may change. Since the science of economics is primarily a set oftools, as opposed to a subject matter, then no subject, however offbeat, need be beyond290its reach.It is worth remembering that Adam Smith, the founder of classical economics, was first and foremost a philosopher. He strove to be a moralist and, in doing so, became aneconomist. When he published The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759, moderncapitalism was just getting under way. Smith was entranced by the sweeping changes295wrought by this new force, but it wasn’t only the numbers that interested him. It was thehuman effect, the fact that economic forces were vastly changing the way a personthought and behaved in a given situation. What might lead one person to cheat or stealwhile another didn’t? How would one person’s seemingly innocuous choice, good or bad,affect a great number of people down the line? In Smith’s era, cause and effect had begun 300to wildly accelerate; incentives were magnified tenfold. The gravity and shock of thesechanges were as overwhelming to the citizens of his time as the gravity and shock ofmodern life seem to us today.Smith’s true subject was the friction between i ndividual desire and societal norms. The economic historian Robert Heilbroner, writing in The Worldly Philosophers, wondered305how Smith was able to separate the doings of man, a creature of self-interest, from thegreater moral plane in which man operated. “Smith held that the answer lay in our abilityto put ourselves in the position of a third person, an impartial observer,” Heilbronerwrote, “and in this way to form a notion of the objective…merits of a case.”Consider yourself, then, in the company of a third person—or, if you will, a pair of third 310people—eager to explore the objective merits of interesting cases. These explorationsgenerally begin with the asking of a simple unasked question. Such as: what doschoolteachers and sumo wrestlers have in common?。