帆船爱好者需要深入了解的20个专业术语

- 格式:docx

- 大小:76.93 KB

- 文档页数:4

船员应了解的航运术语1导言作为一名船员,在工作中我们必须掌握大量的航运术语,只有熟悉了这些术语,才能更好的完成自己的工作。

本文将介绍一些船员必须掌握的航运术语。

2船舶2.1船体和船舶部位首先我们来学习一些有关船体和船舶部位的术语:·船头:船体前部。

·船尾:船体后部,也称船艏。

·船体:船舶的主体结构。

·舱口:装货的通道口。

·货舱:船体内储存货物的地方。

·舱盖:封闭货舱的门。

2.2船舶运行和控制了解船舶运行和控制术语对于船员来说也非常重要:·航向:船舶的前进方向。

·航速:船舶的速度。

·船速计:测量船舶速度的仪器。

·舵柄:控制舵的杆状物。

·舵轮:用于控制舵柄的轮形物。

3船员3.1船舶工作人员管理船舶的工作人员也有一些专用的术语:·船长:船舶的管理者,负责船舶的安全和运营。

·轮机长:负责船舶的动力系统和设备的管理者。

·航海士:负责航行、水文学和气象学等方面的工作。

·机务员:负责船舶机械系统的维护和修理。

·水手:执行船上日常工作的船员。

3.2航行和船员安全保障船员安全方面的术语也不容忽视:·无限近海:指距离陆地200海里以外的海域。

·船舶灯光:船舶在夜间航行时使用的灯光,包括船首灯、舷灯、尾灯等。

·海图:用于航行的海洋地图。

·航标:指示航线和航向的标志。

·拯救设备:船上用于拯救人员的设备,比如救生衣、救生艇等。

4结论船员需要理解和掌握的航运术语有很多,以上这些只是其中的一部分。

有了这些专业术语的理解,船员能够更好地进行船舶操作,确保航行安全。

在日常生活中,我们应该积极学习和运用这些术语,提高自身的职业水平。

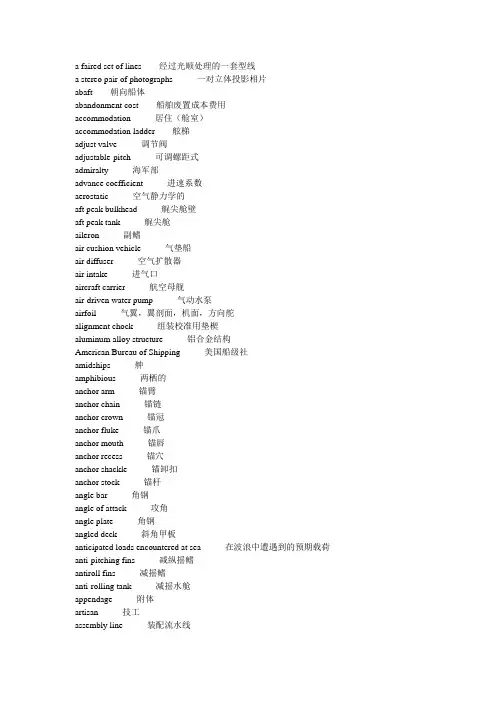

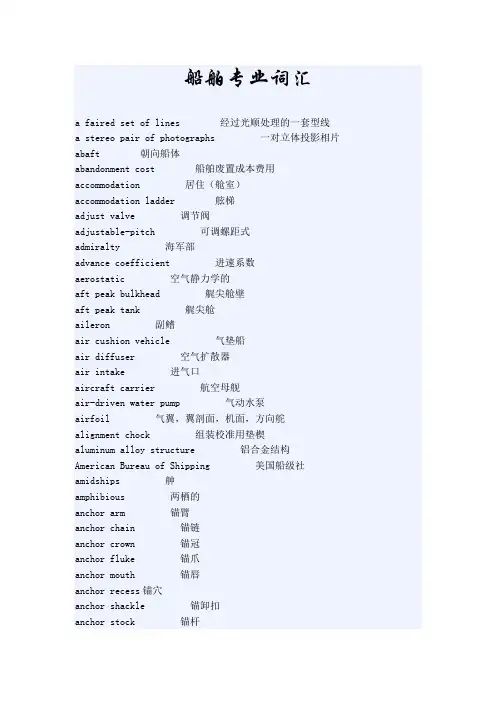

a faired set of lines 经过光顺处理的一套型线a stereo pair of photographs 一对立体投影相片abaft 朝向船体abandonment cost 船舶废置成本费用accommodation 居住(舱室)accommodation ladder 舷梯adjust valve 调节阀adjustable-pitch 可调螺距式admiralty 海军部advance coefficient 进速系数aerostatic 空气静力学的aft peak bulkhead 艉尖舱壁aft peak tank 艉尖舱aileron 副鳍air cushion vehicle 气垫船air diffuser 空气扩散器air intake 进气口aircraft carrier 航空母舰air-driven water pump 气动水泵airfoil 气翼,翼剖面,机面,方向舵alignment chock 组装校准用垫楔aluminum alloy structure 铝合金结构American Bureau of Shipping 美国船级社amidships 舯amphibious 两栖的anchor arm 锚臂anchor chain 锚链anchor crown 锚冠anchor fluke 锚爪anchor mouth 锚唇anchor recess 锚穴anchor shackle 锚卸扣anchor stock 锚杆angle bar 角钢angle of attack 攻角angle plate 角钢angled deck 斜角甲板anticipated loads encountered at sea 在波浪中遭遇到的预期载荷anti-pitching fins 减纵摇鳍antiroll fins 减摇鳍anti-rolling tank 减摇水舱appendage 附体artisan 技工assembly line 装配流水线at-sea replenishment 海上补给augment of resistance 阻力增额auxiliary systems 辅机系统auxiliary tank 调节水舱axial advance 轴向进速backing structure 垫衬结构back-up member 焊接垫板balance weight 平衡锤ball bearing 滚珠轴承ball valve 球阀ballast tank 压载水舱bar 型材bar keel 棒龙骨,方龙骨,矩形龙骨barge 驳船baseline 基线basic design 基本设计batten 压条,板条beam 船宽,梁beam bracket 横梁肘板beam knee 横梁肘板bed-plate girder 基座纵桁bending-moment curves 弯矩曲线Benoulli’s law 伯努利定律berth term 停泊期bevel 折角bidder 投标人bilge 舭,舱底bilge bracket 舭肘板bilge radius 舭半径bilge sounding pipe 舭部边舱水深探管bitt 单柱系缆桩blade root 叶跟blade section 叶元剖面blast 喷丸block coefficient 方形系数blue peter 出航旗boarding deck 登艇甲板boat davit 吊艇架boat fall 吊艇索boat guy 稳艇索bobstay 首斜尾拉索body plan 横剖面图bolt 螺栓,上螺栓固定Bonjean curve 邦戎曲线boom 吊杆boss 螺旋桨轴榖bottom side girder 旁底桁bottom side tank 底边舱bottom transverse 底列板boundary layer 边界层bow line 前体纵剖线bow wave 艏波bowsprit 艏斜桅bow-thruster 艏侧推器box girder 箱桁bracket floor 框架肋板brake 制动装置brake band 制动带brake crank arm 制动曲柄brake drum 刹车卷筒brake hydraulic cylinder 制动液压缸brake hydraulic pipe 刹车液压管breadth extreme 最大宽,计算宽度breadth moulded 型宽breakbulk 件杂货breasthook 艏肘板bridge 桥楼,驾驶台bridge console stand 驾驶室集中操作台BSRA 英国船舶研究协会buckle 屈曲buffer spring 缓冲弹簧built-up plate section 组合型材bulb plate 球头扁钢bulbous bow 球状船艏,球鼻首bulk carrier 散货船bulk oil carrier 散装油轮bulkhead 舱壁bulwark 舷墙bulwark plate 舷墙板bulwark stay 舷墙支撑buoy tender 航标船buoyant 浮力的buoyant box 浮箱Bureau Veritas 法国船级社butt weld 对缝焊接butterfly screw cap 蝶形螺帽buttock 后体纵剖线by convention 按照惯例,按约定cable ship 布缆船cable winch 钢索绞车CAD(computer-aided design) 计算机辅助设计CAE(computer-aided manufacturing) 计算机辅助制造CAM(computer-aided engineering) 计算机辅助工程camber 梁拱cant beam 斜横梁cant frame 斜肋骨cantilever beam 悬臂梁capacity plan 舱容图CAPP(computer –aided process planning) 计算机辅助施工计划制定capsize 倾覆capsizing moment 倾覆力臂captain 船长captured-air-bubble vehicle 束缚气泡减阻船cargo cubic 货舱舱容,载货容积cargo handling 货物装卸carriage 拖车,拖架cast steel stem post 铸钢艏柱catamaran 高速双体船catamaran 双体的cavitation 空泡cavitation number 空泡数cavitation tunnel 空泡水筒center keelson 中内龙骨centerline bulkhead 中纵舱壁centroid 型心,重心,质心,矩心chain cable stopper 制链器chart 海图charterer 租船人chief engineer 轮机长chine 舭,舷,脊chock 导览钳CIM(computer integrated manufacturing) 计算机集成组合制造circulation theory 环流理论classification society 船级社cleat 系缆扣clipper bow 飞剪型船首clutch 离合器coastal cargo 沿海客货轮cofferdam 防撞舱壁combined cast and rolled stem 混合型艏柱commercial ship 营利用船commissary spaces 补给库舱室,粮食库common carrier 通用运输船commuter 交通船compartment 舱室compass 罗经concept design 概念设计connecting tank 连接水柜constant-pitch propeller 定螺距螺旋桨constraint condition 约束条件container 集装箱containerized 集装箱化contract design 合同设计contra-rotating propellers 对转桨controllable-pitch 可控螺距式corrosion 锈蚀,腐蚀couple 力矩,力偶crane 克令吊,起重机crank 曲柄crest (of wave) 波峰crew quarters 船员居住舱criterion 判据,准则Critical Path Method 关键路径法cross-channel automobile ferries 横越海峡车客渡轮cross-sectional area 横剖面面积crow’s nest 桅杆瞭望台cruiser stern 巡洋舰尾crussing range 航程cup and ball joint 球窝关节curvature 曲率curves of form 各船形曲线cushion of air 气垫damage stability 破损稳性damper 缓冲器damping 阻尼davit arm 吊臂deadweight 总载重量de-ballast 卸除压载deck line at side 甲板边线deck longitudinal 甲板纵骨deck stringer 甲板边板deck transverse 强横梁deckhouse 舱面室,甲板室deep v hull 深v型船体delivery 交船depth 船深derrick 起重机,吊杆design margin 设计余量design spiral 设计螺旋循环方式destroyer 驱逐舰detachable shackle 散合式连接卸扣detail design 详细设计diagonal stiffener 斜置加强筋diagram 图,原理图,设计图diesel engine 柴油机dimensionless ratio 无量纲比值displacement 排水量displacement type vessel 排水型船distributed load 分布载荷division 站,划分,分隔do work 做功dock 泊靠double hook 山字钩double iteration procedure 双重迭代法double roller chock 双滚轮式导览钳double-acting steam cylinder 双向作用的蒸汽气缸down halyard 降帆索draft 吃水drag 阻力,拖拽力drainage 排水draught 吃水,草图,设计图,牵引力dredge 挖泥船drift 漂移,偏航drilling rig 钻架drillship 钻井船drive shaft 驱动器轴driving gear box 传动齿轮箱driving shaft system 传动轴系dry dock 干船坞ducted propeller 导管螺旋桨dynamic supported craft 动力支撑型船舶dynamometer 测力计,功率计e.h.p 有效马力eccentric wheel 偏心轮echo-sounder 回声探深仪eddy 漩涡eddy-making resistance 漩涡阻力efficiency 供给能力,供给量electrohydraulic 电动液压的electroplater 电镀工elevations 高度,高程,船型线图的侧面图,立视图,纵剖线图,海拔empirical formula 经验公式enclosed fabrication shop 封闭式装配车间enclosed lifeboat 封闭式救生艇end open link 末端链环end shackle 末端卸扣endurance 续航力endurance 续航力,全功率工作时间engine room frame 机舱肋骨engine room hatch end beam 机舱口端梁ensign staff 船尾旗杆entrance 进流段erection 装配,安装exhaust valve 排气阀expanded bracket 延伸肘板expansion joint 伸缩接头extrapolate 外插fair 光顺faised floor 升高肋板fan 鼓风机fatigue 疲劳feasibility study 可行性研究feathering blade 顺流变距桨叶fender 护舷ferry 渡轮,渡运航线fillet weld connection 贴角焊连接fin angle feedback set 鳍角反馈装置fine fast ship 纤细高速船fine form 瘦长船型finite element 有限元fire tube boiler 水火管锅炉fixed-pitch 固定螺距式flange 突边,法兰盘flanking rudders 侧翼舵flap-type rudder 襟翼舵flare 外飘,外张flat of keel 平板龙骨fleets of vessels 船队flexural 挠曲的floating crane 起重船floodable length curve 可进长度曲线flow of materials 物流flow pattern 流型,流线谱flush deck vessel 平甲板型船flying bridge 游艇驾驶台flying jib 艏三角帆folding batch cover 折叠式舱口盖folding retractable fin stabilizer 折叠收放式减摇鳍following edge 随边following ship 后续船foot brake 脚踏刹车fore peak 艏尖舱forged steel stem 锻钢艏柱forging 锻件,锻造forward draft mark 船首水尺forward/afer perpendicular 艏艉柱forward/after shoulder 前/后肩foundry casting 翻砂铸造frame 船肋骨,框架,桁架freeboard 干舷freeboard deck 干舷甲板freight rate 运费率fresh water loadline 淡水载重线frictional resistance 摩擦阻力Froude number 傅汝德数fuel/water supply vessel 油水供给船full form丰满船型full scale 全尺度fullness 丰满度funnel 烟囱furnishings 内装修gaff 纵帆斜桁gaff foresail 前桅主帆gangway 舷梯gantt chart 甘特图gasketed openings 装以密封垫的开口general arrangement 总布置general cargo ship 杂货船generatrix 母线geometrically similar form 外形相似船型girder 桁梁,桁架girder of foundation 基座纵桁governmental authorities 政府当局,管理机构gradient 梯度graving dock 槽式船坞Green Book 绿皮书,19世纪英国另一船级社的船名录,现合并与劳埃德船级社,用于登录快速远洋船gross ton 长吨(1.016公吨)group technology 成祖建造技术GT 成组建造技术guided-missile cruiser 导弹巡洋舰gunwale 船舷上缘gunwale angle 舷边角钢gunwale rounded thick strake 舷边圆弧厚板guyline 定位索gypsy 链轮gyro-pilot steering indicator 自动操舵操纵台gyroscope 回转仪half breadth plan 半宽图half depth girder 半深纵骨half rounded flat plate 半圆扁钢hard chine 尖舭hatch beam sockets 舱口梁座hatch coaming 舱口围板hatch cover 舱口盖hatch cover 舱口盖板hatch cover rack 舱口盖板隔架hatch side cantilever 舱口悬臂梁hawse pipe 锚链桶hawsehole 锚链孔heave 垂荡heel 横倾heel piece 艉柱根helicoidal 螺旋面的,螺旋状的hinge 铰链hinged stern door 艉部吊门HMS 英国皇家海军舰艇hog 中拱hold 船舱homogeneous cylinder 均质柱状体hopper barge 倾卸驳horizontal stiffener 水平扶强材hub 桨毂,轴毂,套筒hull form 船型,船体外形hull girder stress 船体桁应力HV AC(heating ventilating and cooling) 取暖,通风与冷却hydraulic mechanism 液压机构hydrodynamic 水动力学的hydrofoil 水翼hydrostatic 水静力的IAGG(interactive computer graphics) 交互式计算机图像技术icebreaker 破冰船icebreaker 破冰船IMCO(Intergovernmental Maritime Consultative Organization) 国际海事质询组织immerse 浸水,浸没impact load 冲击载荷imperial unit 英制单位in strake 内列板inboard profile 纵剖面图incremental plasticity 增量塑性independent tank 独立舱柜initial stability at small angle of inclination 小倾角初稳性inland waterways vessel 内河船inner bottom 内底in-plane load 面内载荷intact stability 完整稳性intercostals 肋间的,加强的International Association of Classification Society (IACS) 国际船级社联合会International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC) 国际船模试验水池会议intersection 交点,交叉,横断(切)inventory control 存货管理iterative process 迭代过程jack 船首旗jack 千斤顶joinery 细木工keel 龙骨keel laying 开始船舶建造kenter shackle 双半式连接链环Kristen-Boeing propeller 正摆线推进器landing craft 登陆艇launch 发射,下水launch 汽艇launching equipmeng (向水中)投放设备LCC 大型原油轮leading edge 导缘,导边ledge 副梁材length overall 总长leveler 调平器,矫平机life saving appliance 救生设备lifebuoy 救生圈lifejacket 救生衣lift fan 升力风扇lift offsets 量取型值light load draft 空载吃水lightening hole 减轻孔light-ship 空船limbers board 舭部污水道顶板liner trade 定期班轮营运业lines 型线lines plan 型线图Linnean hierarchical taxonomy 林式等级式分类学liquefied gas carrier 液化气运输船liquefied natural gas carrier 液化天然气船liquefied petroleum gas carrier 液化石油气船liquid bulk cargo carrier 液体散货船liquid chemical tanker 液体化学品船list 倾斜living and utility spaces 居住与公用舱室Lloyd’s Register of shipping 劳埃德船级社Lloyd’s Rules 劳埃德规范Load Line Convention 载重线公约load line regulations 载重线公约,规范load waterplane 载重水线面loft floor 放样台longitudinal (transverse) 纵(横)稳心高longitudinal bending 纵总弯曲longitudinal prismatic coefficient 纵向菱形系数longitudinal strength 纵总强度longitudinally framed system 纵骨架式结构luffing winch 变幅绞车machinery vendor 机械(主机)卖方magnet gantry 磁力式龙门吊maiden voyage 处女航main impeller 主推叶轮main shafting 主轴系major ship 大型船舶maneuverability 操纵性manhole 人孔margin plate 边板maritime 海事的,海运的,靠海的mark disk of speed adjusting 速度调整标度盘mast 桅杆mast clutch 桅座matrix 矩阵merchant ship 商船Merchant Shipbuilding Return 商船建造统计表metacenter 稳心metacentric height 稳心高metal plate path 金属板电镀槽metal worker 金属工metric unit 公制单位middle line plane 中线面midship section 舯横剖面midship section coefficient 中横剖面系数ML 物资清单,物料表model tank 船模试验水池monitoring desk of main engine operation 主机操作监视台monitoring screen of screw working condition 螺旋桨运转监视屏more shape to the shell 船壳板的形状复杂mould loft 放样间multihull vessel 多体船multi-purpose carrier 多用途船multi-ship program 多种船型建造规划mushroom ventilator 蘑菇形通风桶mutually exclusive attribute 相互排它性的属性N/C 数值控制nautical mile 海里naval architecture 造船学navigation area 航区navigation deck 航海甲板near-universal gear 准万向舵机,准万向齿轮net-load curve 静载荷曲线neutral axis 中性轴,中和轴neutral equilibrium 中性平衡non-retractable fin stabilizer 不可收放式减摇鳍normal 法向的,正交的normal operating condition 常规运作状况nose cone 螺旋桨整流帽notch 开槽,开凹口oar 橹,桨oblique bitts 斜式双柱系缆桩ocean going ship 远洋船off-center loading 偏离中心的装载offsets 型值offshore drilling 离岸钻井offshore structure 离岸工程结构物oil filler 加油点oil skimmer 浮油回收船oil-rig 钻油架on-deck girder 甲板上桁架open water 敞水optimality criterion 最优性准则ore carrier 矿砂船orthogonal 矩形的orthogonal 正交的out strake 外列板outboard motor 舷外机outboard profile 侧视图outer jib 外首帆outfit 舾装outfitter 舾装工outrigger 舷外吊杆叉头overall stability 总体稳性overhang 外悬paddle 桨paddle-wheel-propelled 明轮推进的Panama Canal 巴拿马运河panting arrangement 强胸结构,抗拍击结构panting beam 强胸横梁panting stringer 抗拍击纵材parallel middle body 平行中体partial bulkhead 局部舱壁payload 有效载荷perpendicular 柱,垂直的,正交的photogrammetry 投影照相测量法pile driving barge 打桩船pillar 支柱pin jig 限位胎架pintle 销,枢轴pipe fitter 管装工pipe laying barge 铺管驳船piston 活塞pitch 螺距pitch 纵摇plan views 设计图planning hull 滑行船体Plimsoll line 普林索尔载重线polar-exploration craft 极地考察船poop 尾楼port 左舷port call 沿途到港停靠positive righting moment 正扶正力矩power and lighting system 动力与照明系统precept 技术规则preliminary design 初步设计pressure coaming 阻力式舱口防水挡板principal dimensions 主尺度Program Evaluation and Review Technique 规划评估与复核法progressive flooding 累进进水project 探照灯propeller shaft bracket 尾轴架propeller type log 螺旋桨推进器测程仪PVC foamed plastic PVC泡沫塑料quadrant 舵柄quality assurance 质量保证quarter 居住区quarter pillar 舱内侧梁柱quartering sea 尾斜浪quasi-steady wave 准定长波quay 码头,停泊所quotation 报价单racking 倾斜,变形,船体扭转变形radiography X射线探伤rake 倾斜raked bow 前倾式船首raster 光栅refrigerated cargo ship 冷藏货物运输船Register (船舶)登录簿,船名录Registo Italiano Navade 意大利船级社regulating knob of fuel pressure 燃油压力调节钮reserve buoyancy 储备浮力residuary resistance 剩余阻力resultant 合力reverse frame 内底横骨Reynolds number 雷诺数right-handed propeller 右旋进桨righting arm 扶正力臂,恢复力臂rigid side walls 刚性侧壁rise of floor 底升riverine warfare vessel 内河舰艇rivet 铆接,铆钉roll 横摇roll-on/roll-off (Ro/Ro) 滚装rotary screw propeller 回转式螺旋推进器rounded gunwale 修圆的舷边rounded sheer strake 圆弧舷板rubber tile 橡皮瓦rudder 舵rudder bearing 舵承rudder blade 舵叶rudder control rod 操舵杆rudder gudgeon 舵钮rudder pintle 舵销rudder post 舵柱rudder spindle 舵轴rudder stock 舵杆rudder trunk 舵杆围井run 去流段sag 中垂salvage lifting vessel 救捞船scale 缩尺,尺度schedule coordination 生产规程协调schedule reviews 施工生产进度审核screen bulkhead 轻型舱壁Sea keeping performance 耐波性能sea spectra 海浪谱sea state 海况seakeeping 适航性seasickness 晕船seaworthness 适航性seaworthness 适航性section moulus 剖面模数sectiongs 剖面,横剖面self-induced 自身诱导的self-propulsion 自航semi-balanced rudder 半平衡舵semi-submersible drilling rig 半潜式钻井架shaft bossing 轴榖shaft bracket 轴支架shear 剪切,剪力shear buckling 剪切性屈曲shear curve 剪力曲线sheer 舷弧sheer aft 艉舷弧sheer drawing 剖面图sheer forward 艏舷弧sheer plane 纵剖面sheer profile 总剖线sheer profile 纵剖图shell plating 船壳板ship fitter 船舶装配工ship hydrodynamics 船舶水动力学shipway 船台shipyard 船厂shrouded screw 有套罩螺旋桨,导管螺旋桨side frame 舷边肋骨side keelson 旁内龙骨side plate 舷侧外板side stringer 甲板边板single-cylinder engine 单缸引擎sinkage 升沉six degrees of freedom 六自由度skin friction 表面摩擦力skirt (气垫船)围裙slamming 砰击sleeve 套管,套筒,套环slewing hydraulic motor 回转液压马达slice 一部分,薄片sloping shipway 有坡度船台sloping top plate of bottom side tank 底边舱斜顶板slopint bottom plate of topside tank 定边舱斜底板soft chine 圆舭sonar 声纳spade rudder 悬挂舵spectacle frame 眼睛型骨架speed-to-length ratio 速长比sponson deck 舷伸甲板springing 颤振stability 稳性stable equilibrium 稳定平衡starboard 右舷static equilibrium 静平衡steamer 汽轮船steering gear 操纵装置,舵机stem 船艏stem contour 艏柱型线stern 船艉stern barrel 尾拖网滚筒stern counter 尾突体stern ramp 尾滑道,尾跳板stern transom plate 尾封板stern wave 艉波stiffen 加劲,加强stiffener 扶强材,加劲杆straddle 跨立,外包式叶片strain 应变strake 船体列板streamline 流线streamlined casing 流线型套管strength curves 强度曲线strength deck 强力甲板stress concentration 应力集中structural instability 结构不稳定性strut 支柱,支撑构型subassembly 分部装配subdivision 分舱submerged nozzle 浸没式喷口submersible 潜期suction back of a blade 桨叶片抽吸叶背Suez Canal tonnage 苏伊士运河吨位限制summer load water line 夏季载重水线superintendent 监督管理人,总段长,车间主任superstructure 上层建筑Supervision of the Society’s surveyor 船级社验船师的监造书supper cavitating propeller 超空泡螺旋桨surface nozzle 水面式喷口surface piercing 穿透水面的surface preparation and coating 表面加工处理与喷涂surge 纵荡surmount 顶上覆盖,越过swage plate 压筋板swash bulkhead 止荡舱壁SWATH (Small Waterplane Area Twin Hull) 小水线面双体船sway 横荡tail-stabilizer anchor 尾翼式锚talking paper 讨论文件tangential 切向的,正切的tangential viscous force 切向粘性力tanker 油船tee T型构件,三通管tender 交通小艇tensile stress 拉(张)应力thermal effect 热效应throttle valve 节流阀throughput 物料流量thrust 推力thruster 推力器,助推器timber carrier 木材运输船tip of a blade 桨叶叶梢tip vortex 梢涡toed towards amidships 趾部朝向船舯tonnage 吨位torpedo 鱼雷torque 扭矩trailing edge 随边transom stern 方尾transverse bulkhead plating 横隔舱壁板transverse section 横剖面transverse stability 横稳性trawling 拖网trial 实船试验trim 纵倾trim by the stern/bow 艉艏倾trimaran 三体的tripping bracket 防倾肘板trough 波谷tugboat 拖船tumble home (船侧)内倾tunnel wall effect 水桶壁面效应turnable blade 可转动式桨叶turnable shrouded screw 转动导管螺旋桨tweendeck cargo space 甲板间舱tweendedk frame 甲板间肋骨two nodded frequency 双节点频率ULCC 超级大型原油轮ultrasonic 超声波的underwriter (海运)保险商unsymmetrical 非对称的upright position 正浮位置vapor pocket 气化阱ventilation and air conditioning diagram 通风与空调铺设设计图Venturi section 文丘里试验段vertical prismatic coefficient 横剖面系数vertical-axis(cycloidal)propeller 直叶(摆线)推进器vessel component vender 造船部件销售商viscosity 粘性VLCC 巨型原油轮V oith-Schneider propeller 外摆线直翼式推进器v-section v型剖面wake current 伴流,尾流water jet 喷水(推进)管water plane 水线面watertight integrity 水密完整性wave pattern 波形wave suppressor 消波器,消波板wave-making resistance 兴波阻力weather deck 露天甲板web beam 强横梁web frame 腹肋板weler 焊工wetted surface 湿表面积winch 绞车windlass 起锚机wing shaft 侧轴wing-keel 翅龙骨(游艇)working allowance 有效使用修正量worm gear 蜗轮,蜗杆yacht 快艇yard issue 船厂开工任务发布书yards 帆桁yaw 首摇。

船舶专业常用词汇a faired set of lines 经过光顺处理的一套型线a stereo pair of photographs 一对立体投影相片abaft 朝向船体abandonment cost 船舶废置成本费用accommodation 居住(舱室)accommodation ladder 舷梯adjust valve 调节阀adjustable-pitch 可调螺距式admiralty 海军部advance coefficient 进速系数aerostatic 空气静力学的aft peak bulkhead 艉尖舱壁aft peak tank 艉尖舱aileron 副鳍air cushion vehicle 气垫船air diffuser 空气扩散器air intake 进气口aircraft carrier 航空母舰air-driven water pump 气动水泵airfoil 气翼,翼剖面,机面,方向舵alignment chock 组装校准用垫楔aluminum alloy structure 铝合金结构American Bureau of Shipping 美国船级社amidships 舯amphibious 两栖的anchor arm 锚臂anchor chain 锚链anchor crown 锚冠anchor fluke 锚爪anchor mouth 锚唇anchor recess 锚穴anchor shackle 锚卸扣anchor stock 锚杆angle bar 角钢angle of attack 攻角angle plate 角钢angled deck 斜角甲板anticipated loads encountered at sea 在波浪中遭遇到的预期载荷anti-pitching fins 减纵摇鳍antiroll fins 减摇鳍anti-rolling tank 减摇水舱appendage 附体artisan 技工assembly line 装配流水线at-sea replenishment 海上补给augment of resistance 阻力增额auxiliary systems 辅机系统auxiliary tank 调节水舱axial advance 轴向进速backing structure 垫衬结构back-up member 焊接垫板balance weight 平衡锤ball bearing 滚珠轴承ball valve 球阀ballast tank 压载水舱bar 型材bar keel 棒龙骨,方龙骨,矩形龙骨barge 驳船baseline 基线basic design 基本设计batten 压条,板条beam 船宽,梁beam bracket 横梁肘板beam knee 横梁肘板bed-plate girder 基座纵桁bending-moment curves 弯矩曲线Benoulli’s law 伯努利定律berth term 停泊期bevel 折角bilge bracket 舭肘板bilge radius 舭半径bilge sounding pipe 舭部边舱水深探管bitt 单柱系缆桩blade root 叶跟blade section 叶元剖面blast 喷丸block coefficient 方形系数blue peter 出航旗boarding deck 登艇甲板boat davit 吊艇架boat fall 吊艇索boat guy 稳艇索bobstay 首斜尾拉索 body plan 横剖面图bolt 螺栓,上螺栓固定Bonjean curve 邦戎曲线boom 吊杆boss 螺旋桨轴榖bottom side girder 旁底桁bottom side tank 底边舱bottom transverse 底列板boundary layer 边界层bow line 前体纵剖线bow wave 艏波bowsprit 艏斜桅bow-thruster 艏侧推器box girder 箱桁bracket floor 框架肋板brake 制动装置brake band 制动带brake crank arm 制动曲柄brake drum 刹车卷筒brake hydraulic cylinder 制动液压缸brake hydraulic pipe 刹车液压管breadth extreme 最大宽,计算宽度breadth moulded 型宽breakbulk 件杂货breasthook 艏肘板bridge 桥楼,驾驶台bridge console stand 驾驶室集中操作台BSRA 英国船舶研究协会buckle 屈曲buffer spring 缓冲弹簧built-up plate section 组合型材bulb plate 球头扁钢bulbous bow 球状船艏,球鼻首bulk carrier 散货船bulk oil carrier 散装油轮bulkhead 舱壁bulwark 舷墙bulwark plate 舷墙板bulwark stay 舷墙支撑buoy tender 航标船buoyant 浮力的buoyant box 浮箱Bureau Veritas 法国船级社butt weld 对缝焊接butterfly screw cap 蝶形螺帽buttock 后体纵剖线by convention 按照惯例,按约定cable ship 布缆船cable winch 钢索绞车CAD(computer-aided design) 计算机辅助设计CAE(computer-aided manufacturing) 计算机辅助制造CAM(computer-aided engineering) 计算机辅助工程camber 梁拱cant beam 斜横梁cant frame 斜肋骨cantilever beam 悬臂梁capacity plan 舱容图CAPP(computer –aided process planning) 计算机辅助施工计划制定capsize 倾覆capsizing moment 倾覆力臂captain 船长captured-air-bubble vehicle 束缚气泡减阻船cargo cubic 货舱舱容,载货容积cargo handling 货物装卸carriage 拖车,拖架cast steel stem post 铸钢艏柱catamaran 高速双体船catamaran 双体的cavitation 空泡cavitation number 空泡数cavitation tunnel 空泡水筒center keelson 中内龙骨centerline bulkhead 中纵舱壁centroid 型心,重心,质心,矩心chain cable stopper 制链器chart 海图charterer 租船人chief engineer 轮机长chine 舭,舷,脊chock 导览钳CIM(computer integrated manufacturing) 计算机集成组合制造circulation theory 环流理论classification society 船级社cleat 系缆扣clipper bow 飞剪型船首clutch 离合器coastal cargo 沿海客货轮cofferdam 防撞舱壁combined cast and rolled stem 混合型艏柱commercial ship 营利用船commissary spaces 补给库舱室,粮食库common carrier 通用运输船commuter 交通船compartment 舱室compass 罗经concept design 概念设计connecting tank 连接水柜constant-pitch propeller 定螺距螺旋桨constraint condition 约束条件container 集装箱containerized 集装箱化contract design 合同设计contra-rotating propellers 对转桨controllable-pitch 可控螺距式corrosion 锈蚀,腐蚀couple 力矩,力偶crane 克令吊,起重机crank 曲柄crest (of wave) 波峰crew quarters 船员居住舱criterion 判据,准则Critical Path Method 关键路径法cross-channel automobile ferries 横越海峡车客渡轮cross-sectional area 横剖面面积crow’s nest桅杆瞭望台cruiser stern 巡洋舰尾crussing range 航程cup and ball joint 球窝关节curvature 曲率curves of form 各船形曲线cushion of air 气垫damage stability 破损稳性damper 缓冲器damping 阻尼davit arm 吊臂deadweight 总载重量de-ballast 卸除压载deck line at side 甲板边线deck longitudinal 甲板纵骨deck stringer 甲板边板deck transverse 强横梁deckhouse 舱面室,甲板室deep v hull 深v型船体delivery 交船depth 船深derrick 起重机,吊杆design margin 设计余量design spiral 设计螺旋循环方式destroyer 驱逐舰detachable shackle 散合式连接卸扣detail design 详细设计diagonal stiffener 斜置加强筋diagram 图,原理图,设计图diesel engine 柴油机dimensionless ratio 无量纲比值displacement 排水量displacement type vessel 排水型船distributed load 分布载荷division 站,划分,分隔do work 做功dock 泊靠double hook 山字钩double iteration procedure 双重迭代法double roller chock 双滚轮式导览钳double-acting steam cylinder 双向作用的蒸汽气缸down halyard 降帆索draft 吃水drag 阻力,拖拽力drainage 排水draught 吃水,草图,设计图,牵引力dredge 挖泥船drift 漂移,偏航drilling rig 钻架drillship 钻井船drive shaft 驱动器轴driving gear box 传动齿轮箱driving shaft system 传动轴系dry dock 干船坞ducted propeller 导管螺旋桨dynamic supported craft 动力支撑型船舶dynamometer 测力计,功率计e.h.p 有效马力eccentric wheel 偏心轮echo-sounder 回声探深仪eddy 漩涡eddy-making resistance 漩涡阻力efficiency 供给能力,供给量electrohydraulic 电动液压的electroplater 电镀工elevations 高度,高程,船型线图的侧面图,立视图,纵剖线图,海拔empirical formula 经验公式enclosed fabrication shop 封闭式装配车间enclosed lifeboat 封闭式救生艇end open link 末端链环end shackle 末端卸扣endurance 续航力endurance 续航力,全功率工作时间engine room frame 机舱肋骨engine room hatch end beam 机舱口端梁ensign staff 船尾旗杆entrance 进流段erection 装配,安装exhaust valve 排气阀expanded bracket 延伸肘板expansion joint 伸缩接头extrapolate 外插fair 光顺faised floor 升高肋板fan 鼓风机fatigue 疲劳feasibility study 可行性研究feathering blade 顺流变距桨叶fender 护舷ferry 渡轮,渡运航线fillet weld connection 贴角焊连接fin angle feedback set 鳍角反馈装置fine fast ship 纤细高速船fine form 瘦长船型finite element 有限元fire tube boiler 水火管锅炉fixed-pitch 固定螺距式flange 突边,法兰盘flanking rudders 侧翼舵flap-type rudder 襟翼舵flare 外飘,外张flat of keel 平板龙骨fleets of vessels 船队flexural 挠曲的floating crane 起重船floodable length curve 可进长度曲线flow of materials 物流flow pattern 流型,流线谱flush deck vessel 平甲板型船flying bridge 游艇驾驶台flying jib 艏三角帆folding batch cover 折叠式舱口盖folding retractable fin stabilizer 折叠收放式减摇鳍following edge 随边following ship 后续船foot brake 脚踏刹车fore peak 艏尖舱forged steel stem 锻钢艏柱forging 锻件,锻造forward draft mark 船首水尺forward/afer perpendicular 艏艉柱forward/after shoulder 前/后肩foundry casting 翻砂铸造frame 船肋骨,框架,桁架freeboard 干舷freeboard deck 干舷甲板freight rate 运费率fresh water loadline 淡水载重线frictional resistance 摩擦阻力Froude number 傅汝德数fuel/water supply vessel 油水供给船full form丰满船型full scale 全尺度fullness 丰满度funnel 烟囱furnishings 内装修gaff 纵帆斜桁gaff foresail 前桅主帆gangway 舷梯gantt chart 甘特图gasketed openings 装以密封垫的开口general arrangement 总布置general cargo ship 杂货船generatrix 母线geometrically similar form 外形相似船型girder 桁梁,桁架girder of foundation 基座纵桁governmental authorities 政府当局,管理机构gradient 梯度graving dock 槽式船坞Green Book 绿皮书,19世纪英国另一船级社的船名录,现合并与劳埃德船级社,用于登录快速远洋船gross ton 长吨(1.016公吨)group technology 成祖建造技术GT 成组建造技术guided-missile cruiser 导弹巡洋舰gunwale 船舷上缘gunwale angle 舷边角钢gunwale rounded thick strake 舷边圆弧厚板guyline 定位索gypsy 链轮gyro-pilot steering indicator 自动操舵操纵台gyroscope 回转仪half breadth plan 半宽图half depth girder 半深纵骨half rounded flat plate 半圆扁钢hard chine 尖舭hatch beam sockets 舱口梁座hatch coaming 舱口围板hatch cover 舱口盖hatch cover 舱口盖板hatch cover rack 舱口盖板隔架hatch side cantilever 舱口悬臂梁hawse pipe 锚链桶hawsehole 锚链孔heave 垂荡heel 横倾heel piece 艉柱根helicoidal 螺旋面的,螺旋状的hinge 铰链hinged stern door 艉部吊门HMS 英国皇家海军舰艇hog 中拱hold 船舱homogeneous cylinder 均质柱状体hopper barge 倾卸驳horizontal stiffener 水平扶强材hub 桨毂,轴毂,套筒hull form 船型,船体外形hull girder stress 船体桁应力HV AC(heating ventilating and cooling) 取暖,通风与冷却hydraulic mechanism 液压机构hydrodynamic 水动力学的hydrofoil 水翼hydrostatic 水静力的IAGG(interactive computer graphics) 交互式计算机图像技术icebreaker 破冰船icebreaker 破冰船IMCO(Intergovernmental Maritime Consultative Organization) 国际海事质询组织immerse 浸水,浸没impact load 冲击载荷imperial unit 英制单位in strake 内列板inboard profile 纵剖面图incremental plasticity 增量塑性independent tank 独立舱柜initial stability at small angle of inclination 小倾角初稳性inland waterways vessel 内河船inner bottom 内底in-plane load 面内载荷intact stability 完整稳性intercostals 肋间的,加强的International Association of Classification Society (IACS) 国际船级社联合会International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC) 国际船模试验水池会议intersection 交点,交叉,横断(切)inventory control 存货管理iterative process 迭代过程jack 船首旗jack 千斤顶joinery 细木工keel 龙骨keel laying 开始船舶建造kenter shackle 双半式连接链环Kristen-Boeing propeller 正摆线推进器landing craft 登陆艇launch 发射,下水launch 汽艇launching equipmeng (向水中)投放设备LCC 大型原油轮leading edge 导缘,导边ledge 副梁材length overall 总长leveler 调平器,矫平机life saving appliance 救生设备lifebuoy 救生圈lifejacket 救生衣lift fan 升力风扇lift offsets 量取型值light load draft 空载吃水lightening hole 减轻孔light-ship 空船limbers board 舭部污水道顶板liner trade 定期班轮营运业lines 型线lines plan 型线图Linnean hierarchical taxonomy 林式等级式分类学liquefied gas carrier 液化气运输船liquefied natural gas carrier 液化天然气船liquefied petroleum gas carrier 液化石油气船liquid bulk cargo carrier 液体散货船liquid chemical tanker 液体化学品船list 倾斜living and utility spaces 居住与公用舱室Lloyd’s Register of shipping劳埃德船级社Lloyd’s Rules劳埃德规范Load Line Convention 载重线公约load line regulations 载重线公约,规范load waterplane 载重水线面loft floor 放样台longitudinal (transverse) 纵(横)稳心高longitudinal bending 纵总弯曲longitudinal prismatic coefficient 纵向菱形系数longitudinal strength 纵总强度longitudinally framed system 纵骨架式结构luffing winch 变幅绞车machinery vendor 机械(主机)卖方magnet gantry 磁力式龙门吊maiden voyage 处女航main impeller 主推叶轮main shafting 主轴系major ship 大型船舶maneuverability 操纵性manhole 人孔margin plate 边板maritime 海事的,海运的,靠海的mark disk of speed adjusting 速度调整标度盘mast 桅杆mast clutch 桅座matrix 矩阵merchant ship 商船Merchant Shipbuilding Return 商船建造统计表metacenter 稳心metacentric height 稳心高metal plate path 金属板电镀槽metal worker 金属工metric unit 公制单位middle line plane 中线面midship section 舯横剖面midship section coefficient 中横剖面系数ML 物资清单,物料表model tank 船模试验水池。

svc航海术语SVC航海术语一、引言SVC航海术语是指在航海活动中使用的专业术语,它们用于描述船舶、航行、导航、通信等方面的概念和操作。

这些术语对于航海人员来说至关重要,能够确保船舶安全航行和有效的通信。

本文将介绍一些常用的SVC航海术语,以加深对航海知识的理解。

二、航行术语1. 船舶:指一切浮船、船舶、艇船、航行器、浮动装置及其他载人或载货工具。

2. 航行:指船舶在水上移动的行为。

3. 航速:指船舶在单位时间内行驶的距离。

4. 航线:指船舶按照预定的航程规划的航行路径。

5. 航向:指船舶相对于地理方向的运动方向。

6. 航程:指船舶从起点到终点所经过的距离。

7. 船首:指船舶的前部。

8. 船尾:指船舶的后部。

三、导航术语1. 航标:指用于引导船舶航行的标志物,如灯塔、浮标等。

2. GPS导航:指使用全球定位系统进行航行导航。

3. 航道:指船舶通行的水道,通常由浮标或灯塔标示。

4. 航行计划:指船舶在航行前制定的详细航行路线和时间计划。

5. 船位:指船舶在海上的准确位置。

6. 航向角:指船舶相对于航向线的角度。

7. 航行速度:指船舶在航行中的实际速度。

8. 纬度:指地球表面从南到北的线条。

9. 经度:指地球表面从西到东的线条。

四、通信术语1. VHF通信:指使用超高频无线电进行船舶间通信。

2. SOS:国际通用的紧急求救信号。

3. AIS:自动识别系统,用于船舶间的自动识别和位置报告。

4. 天线:用于接收和发送无线电信号的装置。

5. 通话:指通过无线电或其他通信设备进行语音交流。

6. 中继台:用于转发通信信号的设备或站点。

7. 频率:指无线电波的频率。

8. 通信范围:指无线电通信设备的有效覆盖范围。

五、安全术语1. 避碰:指船舶相互避免碰撞的行为。

2. 灭火器:用于灭火的装置。

3. 救生艇:用于紧急情况下船员撤离船舶的小型船只。

4. 救生圈:用于紧急情况下投掷给落水人员的救生装备。

5. 遇险:指船舶遭遇危险或紧急情况。

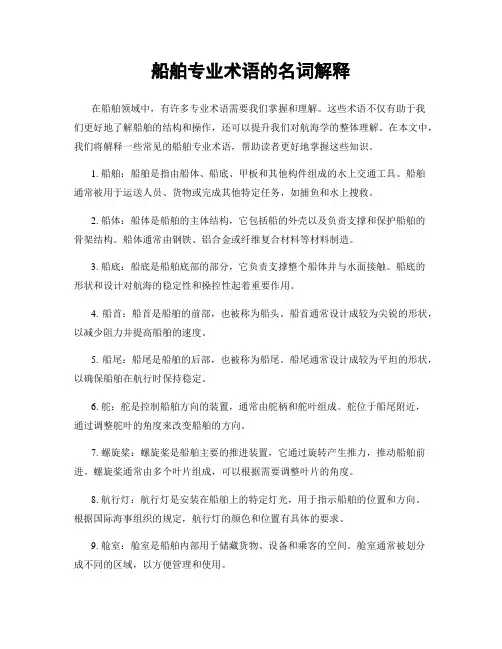

船舶专业术语的名词解释在船舶领域中,有许多专业术语需要我们掌握和理解。

这些术语不仅有助于我们更好地了解船舶的结构和操作,还可以提升我们对航海学的整体理解。

在本文中,我们将解释一些常见的船舶专业术语,帮助读者更好地掌握这些知识。

1. 船舶:船舶是指由船体、船底、甲板和其他构件组成的水上交通工具。

船舶通常被用于运送人员、货物或完成其他特定任务,如捕鱼和水上搜救。

2. 船体:船体是船舶的主体结构,它包括船的外壳以及负责支撑和保护船舶的骨架结构。

船体通常由钢铁、铝合金或纤维复合材料等材料制造。

3. 船底:船底是船舶底部的部分,它负责支撑整个船体并与水面接触。

船底的形状和设计对航海的稳定性和操控性起着重要作用。

4. 船首:船首是船舶的前部,也被称为船头。

船首通常设计成较为尖锐的形状,以减少阻力并提高船舶的速度。

5. 船尾:船尾是船舶的后部,也被称为船尾。

船尾通常设计成较为平坦的形状,以确保船舶在航行时保持稳定。

6. 舵:舵是控制船舶方向的装置,通常由舵柄和舵叶组成。

舵位于船尾附近,通过调整舵叶的角度来改变船舶的方向。

7. 螺旋桨:螺旋桨是船舶主要的推进装置,它通过旋转产生推力,推动船舶前进。

螺旋桨通常由多个叶片组成,可以根据需要调整叶片的角度。

8. 航行灯:航行灯是安装在船舶上的特定灯光,用于指示船舶的位置和方向。

根据国际海事组织的规定,航行灯的颜色和位置有具体的要求。

9. 舱室:舱室是船舶内部用于储藏货物、设备和乘客的空间。

舱室通常被划分成不同的区域,以方便管理和使用。

10. 舱盖:舱盖是船舶上覆盖货物储存区域或机舱的结构。

舱盖可以防止海水进入船舶并保护货物免受恶劣天气的影响。

11. 锚:锚是用于固定船舶位置的重型金属设备。

锚通过抛掷到水底并拉紧锚链来确保船舶在停泊时保持在所需的位置上。

12. 喷气推进器:喷气推进器是一种通过喷射水流产生推力的推进装置。

它适用于需要快速起降或需要在浅水区域进行操作的船舶。

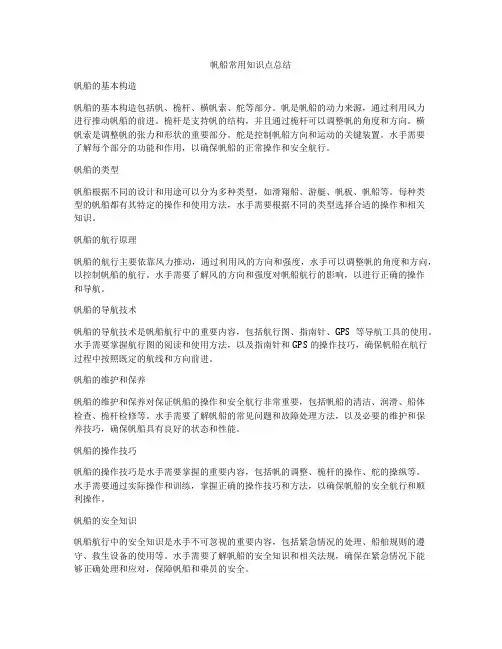

帆船常用知识点总结帆船的基本构造帆船的基本构造包括帆、桅杆、横帆索、舵等部分。

帆是帆船的动力来源,通过利用风力进行推动帆船的前进。

桅杆是支持帆的结构,并且通过桅杆可以调整帆的角度和方向。

横帆索是调整帆的张力和形状的重要部分。

舵是控制帆船方向和运动的关键装置。

水手需要了解每个部分的功能和作用,以确保帆船的正常操作和安全航行。

帆船的类型帆船根据不同的设计和用途可以分为多种类型,如滑翔船、游艇、帆板、帆船等。

每种类型的帆船都有其特定的操作和使用方法,水手需要根据不同的类型选择合适的操作和相关知识。

帆船的航行原理帆船的航行主要依靠风力推动,通过利用风的方向和强度,水手可以调整帆的角度和方向,以控制帆船的航行。

水手需要了解风的方向和强度对帆船航行的影响,以进行正确的操作和导航。

帆船的导航技术帆船的导航技术是帆船航行中的重要内容,包括航行图、指南针、GPS等导航工具的使用。

水手需要掌握航行图的阅读和使用方法,以及指南针和GPS的操作技巧,确保帆船在航行过程中按照既定的航线和方向前进。

帆船的维护和保养帆船的维护和保养对保证帆船的操作和安全航行非常重要,包括帆船的清洁、润滑、船体检查、桅杆检修等。

水手需要了解帆船的常见问题和故障处理方法,以及必要的维护和保养技巧,确保帆船具有良好的状态和性能。

帆船的操作技巧帆船的操作技巧是水手需要掌握的重要内容,包括帆的调整、桅杆的操作、舵的操纵等。

水手需要通过实际操作和训练,掌握正确的操作技巧和方法,以确保帆船的安全航行和顺利操作。

帆船的安全知识帆船航行中的安全知识是水手不可忽视的重要内容,包括紧急情况的处理、船舶规则的遵守、救生设备的使用等。

水手需要了解帆船的安全知识和相关法规,确保在紧急情况下能够正确处理和应对,保障帆船和乘员的安全。

帆船的驾驶技巧帆船的驾驶技巧是水手必须掌握的内容,包括起帆、停帆、调整帆角和方向、控制帆船速度等。

水手需要通过实际操作和训练,掌握正确的驾驶技巧和方法,以确保帆船的安全驾驶和正确操作。

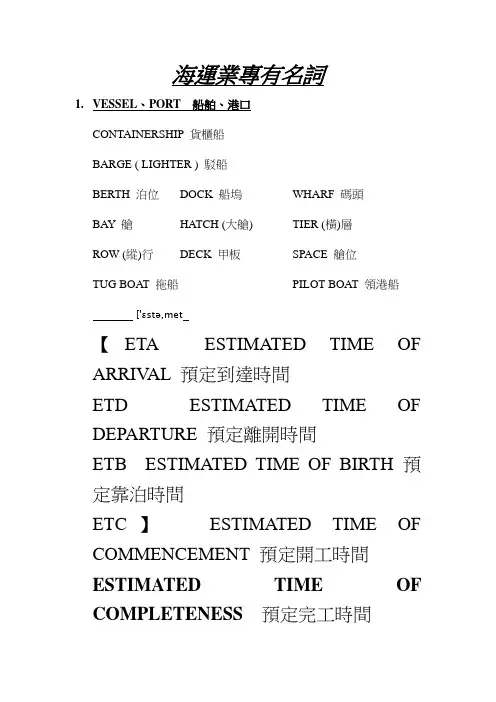

海運業專有名詞1.VESSEL、PORT 船舶、港口CONTAINERSHIP 貨櫃船BARGE ( LIGHTER ) 駁船BERTH 泊位DOCK 船塢WHARF 碼頭BAY 艙HATCH (大艙) TIER (橫)層ROW (縱)行DECK 甲板SPACE 艙位TUG BOAT 拖船PILOT BOAT 領港船['ɛstə,met【ETA ESTIMATED TIME OF ARRIV AL 預定到達時間ETD ESTIMATED TIME OF DEPARTURE 預定離開時間ETB ESTIMATED TIME OF BIRTH 預定靠泊時間ETC】ESTIMATED TIME OF COMMENCEMENT 預定開工時間ESTIMATED TIME OF COMPLETENESS 預定完工時間CAPTAIN. MASTER 船長OFFICER ['ɔfəsɚ]高級船員CREW 船員(水手) LASHING ['læʃɪŋ]绑定SHORING 固定TRIMMING 平艙TEU TWENTY FOOT EQUIV ALENT UNIT 20呎貨櫃單位FEU FORTY FOOT EQUIV ALENT UNIT 40呎貨櫃單位2.OPERATION 作業EQUIPMENT & FACILITIES 設備及機具TERMINAL ['tɝmən!]貨櫃基地1.DEPOT ['dipo]貨櫃場2.INLAND DEPOT 內陸貨櫃場3.ON DOCK CY 岸邊堆場(码头堆场)4.OFF DOCK CY 內陸堆場【-WAREHUOSE】1.GENERAL 普通2.REEFER 冷凍3.DANGEROUS CARGO 危險品4.BULK [bʌlk]散裝5.CUSTOMS(海关、风俗习惯)JOINTLOCK 联锁6.BONDED ['bɑndɪd]保稅的CRAVE(N/V渴望)起重機1.SHIP’S CRANE [krein](SHIP’S GEAR) 船舶(上)起重机2.MOBILE CRANE 移動式起重机3.FLOATING CRANE 水上起重机4.GANTRY CRANE 岸上、橋式起重機FORK LIFT 堆高機TOP LOADER 堆積機R/T RAIL TRANSTAINER 軌道式門式起重機T/T TIER TRANSTAINER 輪胎式門式起重機S/C STRADDLE CARRIER 跨載機SPREADER 伸展架TRAILER 拖車CHASSIS 拖車架TRACTOR 拖車頭CONTAINER 貨櫃FLATFORM 月台TARE WEIGHT 皮重PAY LOAD 可裝貨重PREFIX ['pri,fɪks]CODE 貨櫃識別記號PRE - COOLING 預冷PTI PER- TRIP INSPECTION 預先溫度檢查STUFFING 裝櫃( V ANNING )UNSTUFFING 拆櫃( DEV ANNING )CARGO ACCEPT TERM 收貨條件1.LCL LESS THAN CONTAINERLOAD 併櫃2.CFS CONTAINER FREIGHTSTATION 併櫃3.FCL FULL CONTAINER LOAD整櫃4.CY CONTAINER YARD 整櫃3.TRANSPORTATION 運輸CARRIER 船舶運送業MON CARRIER 公共運送人2.FEEDER CARRIER 支線運送人3.OCEAN GOING CARRIER 長程運送人CHARTER PARTY 租傭船契約1.TIME CHARTER 論時傭船2.VOYAGE CHARTER 論程傭船3.BARE BOAT CHARTER 空(光)船租賃OPERATION (裝卸貨) 作業1.MID-STREAM OPERATION 中流作業2.SHIPSIDE OPERATION 船邊作業3.TERMINAL OPERATION 貨櫃場作業SERVICE 航線1.LINER SERVICE 定期航線2.FIXED DAY SERVICE 固定日航線3.WEEKLY SERVICE 每週定期航線4.TRAMP SERVICE 不定期航線5.DIRECT SEREVICE (NON-TRANSIT) 直航航線6.FEEDER SERVICE 支線航線7.WAY-PORTS SERVICE 順道航線8.DOOR-TO-DOOR SERVICE 戶到戶航線9.INTERPORTS SERVICE 亞洲近海航線10.TRANSPACIFIC SERVICE 美洲越太平洋航線4.SALES 營業FREIGHT 運費1.MEASUREMENT TON/BASIS 材數噸2.WEIGHT TON 重量噸3.BOX RATE 包櫃價4.SLOTTAGE 艙位租金(成本)5.GRI (GENERAL RATE INCREASE)全面運費調升6.ALL IN RATE 總價SURCHARGE 附加費1.BAF BUNKER ADJUSTMENT FACTOR 油料附加費( BUNKER SUR CHARGE )2.CAF CURRENCY ADJUSTMENT FACTOR 匯率附加費( CURRENCY SUR CHARGE)3.THC TERMINAL HANDLING CHARGE 櫃場調櫃費4.CHC CONTAINER HANDLING CHARGE 貨櫃調櫃費5.YAS YEN APPRECIATION SURCHARGE 日圓升值附加費6.DEMURRAGE 延滯費(重櫃在場)7.DETENTION 延還費(空櫃在外)8.HANDLING ( TRANSIT ) 處理(轉運)SALES TERM 銷售條件1.C & F COST & FREIGHT 成本&運費2.C.I.F. COST, INSURANCE, FREIGHT抵岸價格、起岸價格3.F.O.B. FREE ON BOARD 離岸價格SHIPSIDE TERM 船邊條款1.BERTH TERM 裝卸費船東支付2.FREE IN/ FREE OUT ( FIO ) TERM 裝卸費船東免責3.CY TERM 貨櫃場交貨4.TACKLE TERM 船邊交貨AGREEMENT 協定、CONTRACT 契約1.SERVICE AGREEMENT 航線協定2.COOPERATION AGREEMENT 合作協定3.CONSORTIUM 策略聯盟4.GLOBAL ALLIANCE 環球聯盟CONFERENCE 同盟1.JTJCCDA JAPAN TAIWAN JAPANCONTAINERCONFERENCE DISCUSSION ASSOCIATION台日貨櫃同盟協定2.TWRA TRANS PACIFICWESTBOUND RATEAGREEMENT 跨太平洋西向運費協定3.FMC FEDERAL MARTIMECOMMISSION聯邦海事局4.IDIA INTRA ASIA DISCUSSIONAGREEMENT東亞地區(船東)諮商協定5.SARA SOUTH-ASIA RATEAGREEMENT南亞次大陸地區運費協定6.IRA INDEPENDENT RATEAGREEMENT西亞、波斯灣地區運費協定5.DOCUMENT 文件S/O SHIPPING ORDER 艙位簽載單、託運單CLP CONTAINER LOAD PLAN 裝載計劃EIR EQUIPMENT INTERCHANGE RECEIPT 貨櫃設備交接清單M/F MANIFEST 艙單A/N ARRIV AL NOTICE 到貨通知單D/O DELIVERY ORDER 小提單L/G LETTER OF GUARANTEE 切結書L/C LETTER OF CREDIT 信用狀B/L BILL OF LADING 提單1.CLEAN B/L 清潔提單FOUL B/L不潔提單2.ORIGINAL B/L 正本提單COPYB/L 副本提單3.HOUSE B/L 分提單4.MASTER B/L 主提單5.THROUGH B/L 聯運提單6.NEGOTIABLE B/L 可轉讓提單7.NON-NEGOTIABLE B/L 不可轉讓提單8.(SEA) WAYBILL 直交提單(電放提單)6.OTHERSTOPPING 加裝CO-LOAD 混裝OWNER 船東CHARTERER 租傭船人PRINCIPAL 本人(通常為船舶所有人或船東)AGENT 代理行CUSTOMS BROKER 報關行CONSOLIDATOR 貨運併裝業FORW ARDER 海運承攬運送業NOVCC (Non-vessel-Operating Common Carrier) 無船公共運送人。

船舶专业词汇a faired set of lines 经过光顺处理的一套型线a stereo pair of photographs 一对立体投影相片abaft 朝向船体abandonment cost 船舶废置成本费用accommodation 居住(舱室)accommodation ladder 舷梯adjust valve 调节阀adjustable-pitch 可调螺距式admiralty 海军部advance coefficient 进速系数aerostatic 空气静力学的aft peak bulkhead 艉尖舱壁aft peak tank 艉尖舱aileron 副鳍air cushion vehicle 气垫船air diffuser 空气扩散器air intake 进气口aircraft carrier 航空母舰air-driven water pump 气动水泵airfoil 气翼,翼剖面,机面,方向舵alignment chock 组装校准用垫楔aluminum alloy structure 铝合金结构American Bureau of Shipping 美国船级社amidships 舯amphibious 两栖的anchor arm 锚臂anchor chain 锚链anchor crown 锚冠anchor fluke 锚爪anchor mouth 锚唇anchor recess锚穴anchor shackle 锚卸扣anchor stock 锚杆angle bar 角钢angle of attack 攻角angle plate 角钢angled deck 斜角甲板anticipated loads encountered at sea 在波浪中遭遇到的预期载荷anti-pitching fins 减纵摇鳍antiroll fins 减摇鳍anti-rolling tank 减摇水舱appendage 附体artisan 技工assembly line 装配流水线at-sea replenishment 海上补给augment of resistance 阻力增额auxiliary systems 辅机系统auxiliary tank 调节水舱axial advance 轴向进速backing structure 垫衬结构back-up member 焊接垫板balance weight 平衡锤ball bearing 滚珠轴承ball valve 球阀ballast tank 压载水舱bar 型材bar keel 棒龙骨,方龙骨,矩形龙骨barge 驳船baseline 基线basic design 基本设计batten 压条,板条beam 船宽,梁beam bracket 横梁肘板beam knee 横梁肘板bed-plate girder 基座纵桁bending-moment curves 弯矩曲线Benoulli's law 伯努利定律berth term 停泊期bevel 折角bidder 投标人bilge 舭,舱底bilge bracket 舭肘板bilge radius 舭半径bilge sounding pipe 舭部边舱水深探管bitt 单柱系缆桩blade root 叶跟blade section 叶元剖面blast 喷丸block coefficient 方形系数blue peter 出航旗boarding deck 登艇甲板boat davit 吊艇架boat fall 吊艇索boat guy 稳艇索bobstay 首斜尾拉索body plan 横剖面图bolt 螺栓,上螺栓固定Bonjean curve 邦戎曲线boom 吊杆boss 螺旋桨轴榖bottom side girder 旁底桁bottom side tank 底边舱bottom transverse 底列板boundary layer 边界层bow line 前体纵剖线bow wave 艏波bowsprit 艏斜桅bow-thruster 艏侧推器box girder 箱桁bracket floor 框架肋板brake 制动装置brake band 制动带brake crank arm 制动曲柄brake drum 刹车卷筒brake hydraulic cylinder 制动液压缸brake hydraulic pipe 刹车液压管breadth extreme 最大宽,计算宽度breadth moulded 型宽breakbulk 件杂货breasthook 艏肘板bridge 桥楼,驾驶台bridge console stand 驾驶室集中操作台BSRA 英国船舶研究协会buckle 屈曲buffer spring 缓冲弹簧built-up plate section 组合型材bulb plate 球头扁钢bulbous bow 球状船艏,球鼻首bulk carrier 散货船bulk oil carrier 散装油轮bulkhead 舱壁bulwark 舷墙bulwark plate 舷墙板bulwark stay 舷墙支撑buoy tender 航标船buoyant 浮力的buoyant box 浮箱Bureau Veritas 法国船级社butt weld 对缝焊接butterfly screw cap 蝶形螺帽buttock 后体纵剖线by convention 按照惯例,按约定cable ship 布缆船cable winch 钢索绞车CAD(computer-aided design) 计算机辅助设计CAE(computer-aided manufacturing) 计算机辅助制造CAM(computer-aided engineering) 计算机辅助工程camber 梁拱cant beam 斜横梁cant frame 斜肋骨cantilever beam 悬臂梁capacity plan 舱容图CAPP(computer -aided process planning) 计算机辅助施工计划制定capsize 倾覆capsizing moment 倾覆力臂captain 船长captured-air-bubble vehicle 束缚气泡减阻船cargo cubic 货舱舱容,载货容积cargo handling 货物装卸carriage 拖车,拖架cast steel stem post 铸钢艏柱catamaran 高速双体船catamaran 双体的cavitation 空泡}cavitation number 空泡数cavitation tunnel 空泡水筒center keelson 中内龙骨centerline bulkhead 中纵舱壁centroid 型心,重心,质心,矩心chain cable stopper 制链器chart 海图charterer 租船人chief engineer 轮机长chine 舭,舷,脊chock 导览钳CIM(computer integrated manufacturing) 计算机集成组合制造circulation theory 环流理论classification society 船级社cleat 系缆扣clipper bow 飞剪型船首clutch 离合器coastal cargo 沿海客货轮cofferdam 防撞舱壁combined cast and rolled stem 混合型艏柱commercial ship 营利用船commissary spaces 补给库舱室,粮食库common carrier 通用运输船commuter 交通船compartment 舱室compass 罗经concept design 概念设计connecting tank 连接水柜constant-pitch propeller 定螺距螺旋桨constraint condition 约束条件container 集装箱containerized 集装箱化contract design 合同设计contra-rotating propellers 对转桨controllable-pitch 可控螺距式corrosion 锈蚀,腐蚀couple 力矩,力偶crane 克令吊,起重机crank 曲柄crest (of wave) 波峰crew quarters 船员居住舱criterion 判据,准则Critical Path Method 关键路径法cross-channel automobile ferries 横越海峡车客渡轮cross-sectional area 横剖面面积crow's nest 桅杆瞭望台cruiser stern 巡洋舰尾crussing range 航程cup and ball joint 球窝关节curvature 曲率curves of form 各船形曲线cushion of air 气垫damage stability 破损稳性damper 缓冲器damping 阻尼davit arm 吊臂deadweight 总载重量de-ballast 卸除压载deck line at side 甲板边线deck longitudinal 甲板纵骨deck stringer 甲板边板deck transverse 强横梁deckhouse 舱面室,甲板室deep v hull 深v型船体delivery 交船depth 船深derrick 起重机,吊杆design margin 设计余量design spiral 设计螺旋循环方式destroyer 驱逐舰detachable shackle 散合式连接卸扣detail design 详细设计diagonal stiffener 斜置加强筋diagram 图,原理图,设计图diesel engine 柴油机dimensionless ratio 无量纲比值displacement 排水量displacement type vessel 排水型船distributed load 分布载荷division 站,划分,分隔do work 做功dock 泊靠double hook 山字钩double iteration procedure 双重迭代法double roller chock 双滚轮式导览钳double-acting steam cylinder 双向作用的蒸汽气缸down halyard 降帆索draft 吃水drag 阻力,拖拽力drainage 排水draught 吃水,草图,设计图,牵引力dredge 挖泥船drift 漂移,偏航drilling rig 钻架drillship 钻井船drive shaft 驱动器轴driving gear box 传动齿轮箱driving shaft system 传动轴系dry dock 干船坞ducted propeller 导管螺旋桨dynamic supported craft 动力支撑型船舶dynamometer 测力计,功率计e.h.p 有效马力eccentric wheel 偏心轮echo-sounder 回声探深仪eddy 漩涡eddy-making resistance 漩涡阻力efficiency 供给能力,供给量electrohydraulic 电动液压的electroplater 电镀工elevations 高度,高程,船型线图的侧面图,立视图,纵剖线图,海拔empirical formula 经验公式enclosed fabrication shop 封闭式装配车间enclosed lifeboat 封闭式救生艇end open link 末端链环end shackle 末端卸扣endurance 续航力endurance 续航力,全功率工作时间engine room frame 机舱肋骨engine room hatch end beam 机舱口端梁wensign staff 船尾旗杆entrance 进流段erection 装配,安装exhaust valve 排气阀expanded bracket 延伸肘板expansion joint 伸缩接头extrapolate 外插fair 光顺faised floor 升高肋板fan 鼓风机fatigue 疲劳|feasibility study 可行性研究feathering blade 顺流变距桨叶fender 护舷ferry 渡轮,渡运航线fillet weld connection 贴角焊连接fin angle feedback set 鳍角反馈装置fine fast ship 纤细高速船fine form 瘦长船型finite element 有限元fire tube boiler 水火管锅炉fixed-pitch 固定螺距式flange 突边,法兰盘flanking rudders 侧翼舵flap-type rudder 襟翼舵flare 外飘,外张flat of keel 平板龙骨fleets of vessels 船队flexural 挠曲的floating crane 起重船floodable length curve 可进长度曲线flow of materials 物流flow pattern 流型,流线谱flush deck vessel 平甲板型船flying bridge 游艇驾驶台flying jib 艏三角帆folding batch cover 折叠式舱口盖folding retractable fin stabilizer 折叠收放式减摇鳍following edge 随边following ship 后续船foot brake 脚踏刹车fore peak 艏尖舱forged steel stem 锻钢艏柱forging 锻件,锻造forward draft mark 船首水尺forward/after perpendicular 艏艉柱forward/after shoulder 前/后肩foundry casting 翻砂铸造frame 船肋骨,框架,桁架freeboard 干舷freeboard deck 干舷甲板freight rate 运费率fresh water loadline 淡水载重线frictional resistance 摩擦阻力Froude number 傅汝德数fuel/water supply vessel 油水供给船full form 丰满船型full scale 全尺度fullness 丰满度funnel 烟囱furnishings 内装修gaff 纵帆斜桁gaff foresail 前桅主帆gangway 舷梯gantt chart 甘特图gasketed openings 装以密封垫的开口general arrangement 总布置general cargo ship 杂货船generatrix 母线geometrically similar form 外形相似船型girder 桁梁,桁架girder of foundation 基座纵桁governmental authorities 政府当局,管理机构gradient 梯度graving dock 槽式船坞Green Book 绿皮书,19世纪英国另一船级社的船名录,现合并与劳埃德船级社,用于登录快速远洋船gross ton 长吨(1.016公吨)group technology 成祖建造技术GT 成组建造技术guided-missile cruiser 导弹巡洋舰gunwale 船舷上缘gunwale angle 舷边角钢gunwale rounded thick strake 舷边圆弧厚板guyline 定位索gypsy 链轮gyro-pilot steering indicator 自动操舵操纵台gyroscope 回转仪half breadth plan 半宽图half depth girder 半深纵骨half rounded flat plate 半圆扁钢hard chine 尖舭hatch beam sockets 舱口梁座hatch coaming 舱口围板hatch cover 舱口盖hatch cover 舱口盖板hatch cover rack 舱口盖板隔架hatch side cantilever 舱口悬臂梁hawse pipe 锚链桶hawsehole 锚链孔heave 垂荡heel 横倾heel piece 艉柱根helicoidal 螺旋面的,螺旋状的hinge 铰链hinged stern door 艉部吊门HMS 英国皇家海军舰艇hog 中拱hold 船舱homogeneous cylinder 均质柱状体vhopper barge 倾卸驳horizontal stiffener 水平扶强材hub 桨毂,轴毂,套筒hull form 船型,船体外形hull girder stress 船体桁应力HVAC(heating ventilating and cooling) 取暖,通风与冷却hydraulic mechanism 液压机构hydrodynamic 水动力学的hydrofoil 水翼hydrostatic 水静力的IAGG(interactive computer graphics) 交互式计算机图像技术icebreaker 破冰船icebreaker 破冰船IMCO(Intergovernmental Maritime Consultative Organization)国际海事质询组织immerse 浸水,浸没impact load 冲击载荷imperial unit 英制单位in strake 内列板inboard profile 纵剖面图incremental plasticity 增量塑性independent tank 独立舱柜initial stability at small angle of inclination 小倾角初稳性inland waterways vessel 内河船inner bottom 内底in-plane load 面内载荷intact stability 完整稳性爱intercostals 肋间的,加强的International Association of Classification Society (IACS)国际船级社联合会International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC) 国际船模试验水池会议intersection 交点,交叉,横断(切)inventory control 存货管理iterative process 迭代过程jack 船首旗jack 千斤顶joinery 细木工keel 龙骨keel laying 开始船舶建造kenter shackle 双半式连接链环Kristen-Boeing propeller 正摆线推进器landing craft 登陆艇launch 发射,下水launch 汽艇launching equipmeng (向水中)投放设备LCC 大型原油轮leading edge 导缘,导边ledge 副梁材length overall 总长leveler 调平器,矫平机life saving appliance 救生设备lifebuoy 救生圈lifejacket 救生衣lift fan 升力风扇lift offsets 量取型值light load draft 空载吃水lightening hole 减轻孔light-ship 空船limbers board 舭部污水道顶板liner trade 定期班轮营运业lines 型线lines plan 型线图Linnean hierarchical taxonomy 林式等级式分类学liquefied gas carrier 液化气运输船liquefied natural gas carrier 液化天然气船liquefied petroleum gas carrier 液化石油气船liquid bulk cargo carrier 液体散货船liquid chemical tanker 液体化学品船list 倾斜living and utility spaces 居住与公用舱室Lloyd's Register of shipping 劳埃德船级社Lloyd's Rules 劳埃德规范Load Line Convention 载重线公约load line regulations 载重线公约,规范load waterplane 载重水线面loft floor 放样台longitudinal (transverse) 纵(横)稳心高longitudinal bending 纵总弯曲longitudinal prismatic coefficient 纵向菱形系数longitudinal strength 纵总强度longitudinally framed system 纵骨架式结构luffing winch 变幅绞车machinery vendor 机械(主机)卖方magnet gantry 磁力式龙门吊maiden voyage 处女航main impeller 主推叶轮main shafting 主轴系major ship 大型船舶maneuverability 操纵性manhole 人孔margin plate 边板maritime 海事的,海运的,靠海的mark disk of speed adjusting 速度调整标度盘mast 桅杆mast clutch 桅座matrix 矩阵merchant ship 商船Merchant Shipbuilding Return 商船建造统计表metacenter 稳心metacentric height 稳心高metal plate path 金属板电镀槽metal worker 金属工metric unit 公制单位middle line plane 中线面midship section 舯横剖面midship section coefficient 中横剖面系数ML 物资清单,物料表model tank 船模试验水池monitoring desk of main engine operation 主机操作监视台monitoring screen of screw working condition 螺旋桨运转监视屏more shape to the shell 船壳板的形状复杂mould loft 放样间multihull vessel 多体船multi-purpose carrier 多用途船multi-ship program 多种船型建造规划mushroom ventilator 蘑菇形通风桶mutually exclusive attribute 相互排它性的属性N/C 数值控制nautical mile 海里naval architecture 造船学navigation area 航区navigation deck 航海甲板near-universal gear 准万向舵机,准万向齿轮net-load curve 静载荷曲线neutral axis 中性轴,中和轴neutral equilibrium 中性平衡non-retractable fin stabilizer 不可收放式减摇鳍normal 法向的,正交的normal operating condition 常规运作状况nose cone 螺旋桨整流帽notch 开槽,开凹口oar 橹,桨oblique bitts 斜式双柱系缆桩ocean going ship 远洋船off-center loading 偏离中心的装载offsets 型值offshore drilling 离岸钻井offshore structure 离岸工程结构物oil filler 加油点oil skimmer 浮油回收船oil-rig 钻油架on-deck girder 甲板上桁架open water 敞水optimality criterion 最优性准则ore carrier 矿砂船orthogonal 矩形的orthogonal 正交的out strake 外列板outboard motor 舷外机outboard profile 侧视图outer jib 外首帆outfit 舾装outfitter 舾装工outrigger 舷外吊杆叉头overall stability 总体稳性overhang 外悬paddle 桨paddle-wheel-propelled 明轮推进的Panama Canal 巴拿马运河panting arrangement 强胸结构,抗拍击结构panting beam 强胸横梁panting stringer 抗拍击纵材parallel middle body 平行中体partial bulkhead 局部舱壁payload 有效载荷perpendicular 柱,垂直的,正交的photogrammetry 投影照相测量法pile driving barge 打桩船pillar 支柱pin jig 限位胎架pintle 销,枢轴pipe fitter 管装工pipe laying barge 铺管驳船piston 活塞pitch 螺距pitch 纵摇plan views 设计图planning hull 滑行船体Plimsoll line 普林索尔载重线polar-exploration craft 极地考察船poop 尾楼port 左舷port call 沿途到港停靠positive righting moment 正扶正力矩power and lighting system 动力与照明系统precept 技术规则preliminary design 初步设计pressure coaming 阻力式舱口防水挡板principal dimensions 主尺度Program Evaluation and Review Technique 规划评估与复核法progressive flooding 累进进水project 探照灯propeller shaft bracket 尾轴架propeller type log 螺旋桨推进器测程仪PVC foamed plastic PVC泡沫塑料quadrant 舵柄quality assurance 质量保证quarter 居住区quarter pillar 舱内侧梁柱quartering sea 尾斜浪quasi-steady wave 准定长波quay 码头,停泊所quotation 报价单racking 倾斜,变形,船体扭转变形radiography X射线探伤rake 倾斜raked bow 前倾式船首raster 光栅refrigerated cargo ship 冷藏货物运输船Register (船舶)登录簿,船名录Registo Italiano Navade 意大利船级社regulating knob of fuel pressure 燃油压力调节钮reserve buoyancy 储备浮力residuary resistance 剩余阻力resultant 合力reverse frame 内底横骨Reynolds number 雷诺数right-handed propeller 右旋进桨righting arm 扶正力臂,恢复力臂rigid side walls 刚性侧壁rise of floor 底升riverine warfare vessel 内河舰艇rivet 铆接,铆钉roll 横摇roll-on/roll-off (Ro/Ro) 滚装rotary screw propeller 回转式螺旋推进器rounded gunwale 修圆的舷边rounded sheer strake 圆弧舷板rubber tile 橡皮瓦rudder 舵rudder bearing 舵承rudder blade 舵叶rudder control rod 操舵杆rudder gudgeon 舵钮rudder pintle 舵销rudder post 舵柱rudder spindle 舵轴rudder stock 舵杆rudder trunk 舵杆围井run 去流段sag 中垂salvage lifting vessel 救捞船scale 缩尺,尺度schedule coordination 生产规程协调schedule reviews 施工生产进度审核screen bulkhead 轻型舱壁Sea keeping performance 耐波性能sea spectra 海浪谱sea state 海况seakeeping 适航性seasickness 晕船seaworthness 适航性seaworthness 适航性section moulus 剖面模数sectiongs 剖面,横剖面self-induced 自身诱导的self-propulsion 自航semi-balanced rudder 半平衡舵semi-submersible drilling rig 半潜式钻井架shaft bossing 轴榖shaft bracket 轴支架shear 剪切,剪力shear buckling 剪切性屈曲shear curve 剪力曲线sheer 舷弧sheer aft 艉舷弧sheer drawing 剖面图sheer forward 艏舷弧sheer plane 纵剖面sheer profile 总剖线sheer profile 纵剖图shell plating 船壳板ship fitter 船舶装配工ship hydrodynamics 船舶水动力学shipway 船台shipyard 船厂shrouded screw 有套罩螺旋桨,导管螺旋桨side frame 舷边肋骨side keelson 旁内龙骨side plate 舷侧外板side stringer 甲板边板single-cylinder engine 单缸引擎sinkage 升沉six degrees of freedom 六自由度skin friction 表面摩擦力skirt (气垫船)围裙slamming 砰击sleeve 套管,套筒,套环slewing hydraulic motor 回转液压马达slice 一部分,薄片sloping shipway 有坡度船台sloping top plate of bottom side tank 底边舱斜顶板slopint bottom plate of topside tank 定边舱斜底板soft chine 圆舭sonar 声纳spade rudder 悬挂舵spectacle frame 眼睛型骨架speed-to-length ratio 速长比sponson deck 舷伸甲板springing 颤振stability 稳性stable equilibrium 稳定平衡starboard 右舷static equilibrium 静平衡steamer 汽轮船steering gear 操纵装置,舵机stem 船艏stem contour 艏柱型线stern 船艉stern barrel 尾拖网滚筒stern counter 尾突体stern ramp 尾滑道,尾跳板stern transom plate 尾封板stern wave 艉波stiffen 加劲,加强stiffener 扶强材,加劲杆straddle 跨立,外包式叶片strain 应变strake 船体列板streamline 流线streamlined casing 流线型套管strength curves 强度曲线strength deck 强力甲板stress concentration 应力集中structural instability 结构不稳定性strut 支柱,支撑构型subassembly 分部装配subdivision 分舱submerged nozzle 浸没式喷口submersible 潜期suction back of a blade 桨叶片抽吸叶背Suez Canal tonnage 苏伊士运河吨位限制summer load water line 夏季载重水线superintendent 监督管理人,总段长,车间主任superstructure 上层建筑Supervision of the Society's surveyor 船级社验船师的监造书supper cavitating propeller 超空泡螺旋桨wsurface nozzle 水面式喷口surface piercing 穿透水面的surface preparation and coating 表面加工处理与喷涂surge 纵荡surmount 顶上覆盖,越过swage plate 压筋板swash bulkhead 止荡舱壁SWATH (Small Waterplane Area Twin Hull) 小水线面双体船sway 横荡tail-stabilizer anchor 尾翼式锚talking paper 讨论文件tangential 切向的,正切的tangential viscous force 切向粘性力tanker 油船tee T型构件,三通管tender 交通小艇tensile stress 拉(张)应力thermal effect 热效应throttle valve 节流阀throughput 物料流量thrust 推力thruster 推力器,助推器timber carrier 木材运输船tip of a blade 桨叶叶梢tip vortex 梢涡toed towards amidships 趾部朝向船舯tonnage 吨位torpedo 鱼雷torque 扭矩torque 扭矩trailing edge 随边transom stern 方尾transverse bulkhead plating 横隔舱壁板transverse section 横剖面transverse stability 横稳性trawling 拖网trial 实船试验trim 纵倾trim by the stern/bow 艉艏倾trimaran 三体的tripping bracket 防倾肘板trough 波谷tugboat 拖船tumble home (船侧)内倾tunnel wall effect 水桶壁面效应turnable blade 可转动式桨叶turnable shrouded screw 转动导管螺旋桨tweendeck cargo space 甲板间舱tweendedk frame 甲板间肋骨two nodded frequency 双节点频率ULCC 超级大型原油轮ultrasonic 超声波的underwriter (海运)保险商unsymmetrical 非对称的upright position 正浮位置vapor pocket 气化阱ventilation and air conditioning diagram 通风与空调铺设设计图Venturi section 文丘里试验段vertical prismatic coefficient 横剖面系数vertical-axis(cycloidal)propeller 直叶(摆线)推进器vessel component vender 造船部件销售商viscosity 粘性VLCC 巨型原油轮Voith-Schneider propeller 外摆线直翼式推进器v-section v型剖面wake current 伴流,尾流water jet 喷水(推进)管water plane 水线面watertight integrity 水密完整性wave pattern 波形wave suppressor 消波器,消波板wave-making resistance 兴波阻力weather deck 露天甲板web 腹板web beam 强横梁web frame 腹肋板weler 焊工wetted surface 湿表面积winch 绞车windlass 起锚机wing shaft 侧轴wing-keel 翅龙骨(游艇)working allowance 有效使用修正量worm gear 蜗轮,蜗杆yacht 快艇yard issue 船厂开工任务发布书yards 帆桁yaw 首摇船用主机缩略语AK(Akasako) 赤阪AP(Alpha) 阿尔法BW(B&W) 伯迈斯特-韦恩CA(Callesco) 卡莱森CL(Cegelec Motors) 西盖列克发动机CP(Caterpillar) 卡特皮拉CU(Cummins) 康明斯DH(Daihatsu) 大发DZ(Deutz) 多伊茨GE(G.E.C) 通用电气HA(Hamshin) 阪神KM(Liebknecht) 李克内希特MA(Makita) 牧田MI(Mitsubishi) 三菱MK(Mak) 马克MN(MAN) 曼恩MR(Mirrlees) 米尔列斯MT(Matsui) 三井MW(MWM) 曼海姆NG(Nnrmo) 诺而布NI(Niigata) 新泻PL(Semt-Pielstick) 皮尔斯蒂克SK(Skoda) 斯柯达SZ(Sulzer) 苏尔寿YM(Yaomar) 洋马。

帆船 (sailer ; sailing boat )————利用风帆,靠风力推进的船。

帆船起源于居住在海河区域的古代人的水上交通运输工具。

15世纪初期,中国明代郑和率领庞大船队7次出海,到达亚洲和非洲三十多个国家。

现代帆船始于荷兰。

起源帆船分稳向板帆艇和龙骨帆艇两类。

稳向板帆艇轻快灵活,可在浅水中行驶,奥运会项目中的飞行荷兰人型、荷兰人型、470型、星型、托纳多型等均属此类,是世界最普及的帆船。

龙骨帆艇也称稳向舵艇,体大不灵活,稳定性好,帆力强,只能在深水中行驶。

帆船航行的原理帆船的动力来源﹕帆船的最大动力来源是“白努利效应”,也就是说当空气流经一类似机翼的弧面时,会产生一个向前向上的吸引力。

因此,帆船才有可能朝某角度的逆风方向前进。

而正顺风航行时,“白努利效应”消失,船只反而不能达到最高速。

帆船的航向限制与效益但帆船的航向也不是完全没有限制,在正逆风左右各约45度角内,是无法产生有效益的前进力的。

但是太顺风也不是很好的,这时“白努利效应”消失,船速会再度慢下来,同时也进入不稳定状态。

而有逆风航行能力的船,若要往逆风方向前进,必须采取Z 字形的路线才能到达目的地。

所以,不能张成有效弧形的帆,是没有逆风航行能力的。

这些船只航行于大海上,往往要靠依照季节改变方向的贸易风,才能有去有回。

像现代的帆船,都拥有良好的逆风航行能力。

帆船运动的重要赛事(一) 奥运会运动帆船最重要的赛事,四年一届。

参赛船数受到严格限制,每个国家在每个级别中不论有多少船获得参赛资格,也只允许一条船参赛。

(二)美洲杯帆船赛始创于1857年,每4年举办一届,至今已持续了近150年,是世界上最负盛名的大帆船赛事。

该赛事是名副其实的贵族运动,仅制造参赛船只便需花费上千万乃至数千万美元。

(三)悉尼-霍巴特帆船赛创建于1945年的世界著名远洋帆船赛事。

每年在澳大利亚举行一次,吸引着来自世界各地的航海爱好者。

起点为悉尼湾,终点为澳洲第二古城霍巴特,全程640海里,最快3天就可以到达,最长需要7至8天可以到达。

标准航海用语1. 航向 (heading):船舶或航空器前进的方向角度。

2. 航速 (speed):船舶或航空器前进的速度。

3. 航行 (navigation):船舶或航空器的运行过程。

4. 航线 (route):被船舶或航空器遵循的路径或路线。

5. 航道 (channel):被船舶或航空器用来导航的定义区域。

6. 转弯 (turn):船舶或航空器改变航向或方向的动作。

7. 驶离 (departure):船舶或航空器离开港口或起飞点的行为。

8. 驶入 (arrival):船舶或航空器到达目的地的行为。

9. 航标 (navigational aid):用于引导船舶或航空器航行的地标或标志物。

10. 航行灯 (navigation light):在夜间或低能见度条件下,用于指示船舶或航空器位置和运行方向的灯光设备。

11. 船艏 (bow):船的前部。

12. 船艉 (stern):船的尾部。

13. 打捞 (salvage):从水中搜救、拯救或回收遗失的船舶、物品或人员的行为。

14. 碰擦 (collision):两艘船舶或船舶与物体之间的接触或冲撞。

15. 潮汐(tidal):由月球和太阳引起的海洋水位的周期性变化。

16. 经度 (longitude):表征地球表面上某一点相对于本初子午线的东西距离的度量。

17. 纬度 (latitude):表征地球表面上某一点相对于赤道的北南距离的度量。

18. 航海图 (nautical chart):用于航海者导航的地图,上面标示了水深、海岸线、航标等信息。

19. 海况 (seas condition):描述海洋状况,包括风浪、浪高、浪向等信息。

20. 码头 (dock):供船舶停泊、装卸货物或进行维修的设施。

VOCABULARY3-roller bending machine 三弯机abandon v. 弃船abolish v. 消除ABS 美国船级社acceleration n. 加速度accelerometer n. 加速度表accommodate v. 容纳accommodation deck起居(住舱)甲板accuracy n. 精度accurate synchro device准同步装置acetylene cutter 气割机acid-pickling n. 酸洗acoustics n. 音响效果adhesiveness n. 粘附力adjacent a.相邻的adjust v. 调节administration n. 行政管理admit v. 接纳adopt v. 采纳,采用affiliated factory 分厂,附属工厂aforementioned a.前述aft a. adv. n. (在)船艉aft peak 艉尖舱after service 售后服务ahead n. 正车air bottle 空气瓶air compressor 空压机air reservoir 气瓶air siren 汽笛air-tight test 气密实验alarm bell 警铃alignment n. 找中all waves 全波allowance n. 允值all position 全方位alternating current ( A.C.) 交流电ammonia n. 氨amplify v. 放大an automatic production line自动生产线analogous output 模拟输出analogue computer 模拟计算机anchor n. 锚anchor chain (cable chain)锚链anchor handling 锚操纵anchor windlass (chain windlass) 起锚机anchorage buoy 系泊浮筒angular n. 角度antenna n. 天线anticorrosion precaution 防腐措施apparatus n. (pl. apparatus or apparatuses)仪器,器械,装置appearance n. 外观approval n. 批准,认可approve vt. 认可arbitrate v. 仲裁arc n. 弧度arduous a.艰难的arrange v. 布置,安排asbestos n. 石棉assemble v. 装配Assemble Language 汇编语言assembly n. 装配astern n. 倒车atmospheric survey 大气环流调查atomic power 原子能atomize v. 雾化authority n. 当局automatic control device自动控制装置automatic production line自动生产线automatic steering 自动操舵automatic submerged arc welding自动埋弧焊automatic telephone 自动电话aux. boiler 副锅炉aux. engine 辅机aux. engine room 辅机舱aux. machinery 辅机auxiliary means 辅助手段auxiliary system 辅助系统axial push 轴向推力backing n. 衬垫ballast piping 压载水管系ballast pump 压载泵ballast system 压载系统ballast water 压载水base n. 基准base point n. 基准点basic design 基本(方案)设计basic metal 母材battery unit 蓄电池组beam n. 波束beam n. 横梁bearing n. 轴承bearing hole n. 轴承孔bedplate n. 机座bell set 铃组bending machine 冷弯机berth n. (水平)船台,(船上)床铺berth or slipway fabrication船台装配bilge n. 舱底水bilge keel 舭龙骨bilge plate 舭板bilge pump 舱底水泵bilge system 舱底水系统binary system 二进位制blank n. 毛胚block n. 分段block or section fabrication分段或总段装配blood vessel 血管blower 风机blue collar worker 蓝领,工人boat deck 艇甲板bollard n. 带缆桩bolt n. 螺栓bolthead n. 螺栓头bottom n. 船底bottom plate 底板bottom structure 底板结构bow n. 船艏bow &stern structure 艏艉结构bow section 艏段branch company 分公司,子公司branch system 分系统bridge n. 桥楼bridge control 桥楼控制broadcast n. v. 广播broadcast station 广播站bronze sleeve 青铜套筒bulbous bow 球鼻艏bulk cargo 散装货物bulk-cargo carrier 散装货船bulkhead n. 隔舱壁bulkhead structure 隔舱壁结构bushing n. 衬垫butt joint 对接接头cabin n. 舱室cable fixture 电缆夹具calculation n. 计算calculator n. 计算器calibrate v. 校正calibration n. 校正cam n. 凸轮cam follower 凸轮附件camber n. 梁拱camshaft n. 凸轮轴capstan windlass(anchor winch)锚绞盘cargo n. 船货cargo oil 货油cargo –hold n. 货舱cargo-lifting n. 起货casing n. 罩壳cast iron piece 铸铁件casting n. 铸造cathode-ray type 阴极射线式CCS 中国船级社central control 集控centreline n. 中心线centrifugal a.离心的certificate n. 证书chain drive 链传动chain locker 锚链舱chain pipe 锚链管chain reaction 连锁反应chain stopper 制链器challenge n. v. 挑战chamfer v. 在边缘切斜面changeover switch 转换开关characteristics n.性能,特性,特征charge v. 充(电,气)check n. v. 检验chemical medium 化学介质China Classification Society(CCS)中国船级社China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) 中国远洋公司chip n. 芯片circle n. 圈子,团体class n. 船级classification n. 船级classification society 船级社cleanness n. 清洁度closed circulation 闭式循环clutch n. 离合器CO2 shielded arc welding 二氧化碳气体保护焊Coating n. 图层code n. 法典code display circuit 编码显示电路coefficients of ship form 船型系数cold processing 冷加工collision n. (船只)碰撞combustibility n. 可燃性combustion n. 燃烧combustion chamber 燃烧室combustion gas 燃气commanding telephone 指挥电话communication n. 通讯compartment n. 分隔舱compartment stuffing box隔舱填料函compass n. 罗经compass deck 罗经甲板compensate vt. 补偿competition n. 竞争completion drawing 完工图component n. 组成部分composition n. 成分组成compound excitation 复励comprehensive productivity综合生产能力compressed air 压缩空气compression (power)stroke n.压缩冲程computer control console计算机控制台conceptual a. 概念的condensation n. 冷凝conductor n. 导体connecting rod 连杆connection n. 接头constant voltage 恒压constitute v. 构成consumables n. 消耗品consumption n. 消耗contact v. 触发container n. 集装箱continuous deck 连续甲板contract n. 合同contradiction n. 矛盾control component 控制元件control console 控制台control unit 控制装置converse method 反装法convertor n. 转换器conveyor n. 传送带coolant n. 致冷剂coolant(cooling agent)n. 制冷剂cooler n. 冷却器cooling system 冷却系统cooperation n. 合作coordinate n. 坐标core enterprise 核心企业corrosion n. 腐蚀corrugated a. 波纹状的course n. 航向cover n. 药皮CPP drive 可调浆传动crank cheek 曲柄夹板crankcase n. 曲柄箱crankpin n. 曲柄臂crankshaft n. 曲轴crankweb n. 曲柄臂crew n. (全体)船员cross section 截面crosshead n. 十字头cultivate v. 培养,培育current n. 电流current n. 洋流,水流current-impulse frequency convertor 电流-脉冲频率变换器curve n. 曲线cutting n. 切割cylinder n. 气缸cylinder block 气缸体cylinder cover (cylinder head) 缸盖cylinder liner 气缸衬套cylinder oil 气缸油cylinder wall 缸壁data impulse 数据脉冲davit n. 吊艇架deadweight ton(DWT) n.载重量,吨载量Decca receiver 台卡定位仪deck n. 甲板deck girder 甲板材deck longitudinal 甲板纵骨deck machinery 甲板机deck plate 甲板板deck structure 甲板结构deckhouse 甲板室deform v. 形变deliver v. 交货,交船delivery n. 交船,交货delivery ceremony 交船典礼derrick n. 吊杆design stage 设计阶段designation n. 名称,牌号designation n. 目的地detail design 详细(施工)设计detect v. 探测detect v. 侦察detection n. 探测deviation n. 位移dial n. 刻度盘diameter n. 直径differentia n. 差异digital computer 数字计算机digital output 数字输出direct current(D.C.)直流电direct drive 直接传动direct telephone对讲电话,直线电话directional finder 测向仪directional instrument 指向仪器directional stability 航向稳定性disc n. 圆盘discharge n. v. 排水dispensable a. 非必要的dispute n. v. 争端,争执distribute v. 分布distribute v. 分配,配电distribution n. 配电distribution box 分电箱distribution panel 区配电板distribution switch 配电开关distribution system n. 配电系统division n. 划分DNV 挪威船级社Dock n. 船坞dock trial 码头试验docking winch 带缆绞车Doppler effect 多普勒效应Doppler frequency offset多普勒频移Doppler sonar log多普勒声纳计程仪double bottom 双层底double-action a.双作用down-vertical welding 下行焊draft(draught)n. 吃水drainage n. 疏水,泄水drawing n. 图纸drawing instrument 绘图仪drift v. 漂移drinking water 饮用水drip-proof type 防滴式drive n. 传动drive mechanism 传动机构drive mechanism 传动装置drive unit 传动装置driven shaft 从动轴dry v. 烘干drydock n. 干船坞dynamic –pressure type 水压式echo signal 返回信号echo sounder 回声测深仪economic effect 经济效益edge preparation 边缘加工edge processing 边缘加工edger n. 刨边机eject v. 喷射elapse v. (时光)消逝electric brain 电脑electric load 负荷electrical arc 电弧electrical compass 电罗经electrical drive 电力托动electrical energy 电能electrical impulse 电脉冲electrical power 电力electrical shedding 放电electrical signal 电器信号electrical slag welding 电焊渣electrical unit 电器装置electrical user 电器设备electrical-driven a. 电动的electrician n. 电工electricity outfitting 电舾electrode n. 焊条electromagnetic contactor电磁接触器electromagnetic induction 电磁感应electromagnetic log 电磁计程仪electromagnetic sensor 电磁传感器electronic computer 电子计算机electronics n. 电子(学)element n. 机械零件element n. 要素emerge v. 崛起,兴起emergency control 应急控制emergency network 应急电网emergency power station 应急电站emergency radio transmitter应急无线电发信机emergency steering 应急操舵emergency switchboard 应急配电板emergency telegraph 应急传令钟emergent discharge 应急排放emergent service 应急使用enclose v. 封闭encounter v. 遭遇energy convertor 换能器engine foundation (engine seat )机座engine frame 机架engine oil 机油engine outfitting 机舾engine space 机舱engineer n. 轮机员engineer n. 工程师engineering and technical team工程技术队伍engineer vessel 工程船engine-room 机舱ensure v. 确保enterprise n. 企业EO 无人机舱equipment n. 设备error n. 误差essence n. 实质,本质evolve v. 渐进,进化,演变excessive a. 过量的,极度的excitation n. 励磁excite v. 激励exhaust port 排气口exhaust stroke 排气冲程exhaust valve 排气阀expand v. 扩张,扩建expansion n. 展开图expansion stroke 膨胀(作工)冲程expansion tank 膨胀箱experiment n. 实验exterior force 外力extinguish v. 灭火F.O.meter 燃油流量计F.O.tank 燃油舱Fabricate v. 装配,制作fabrication n. 装配facile adaptability 灵活的适应性facsimile transmission(fax)传真fairing n. 光顺体,流线体fair-lead n. 导缆孔fashioned steel 型钢fast speed (rapidity)快速性fathometer n. 侧深仪feed v. 馈给feed circuit 馈电线路fillet seam 角焊缝fillet welding 角焊filter n. 过滤器. 过滤fine a. 纤细的finished product 成品fire alarm 火警fire hazard 火灾fire pump 消防泵fire-fighting system 消防系统fire-resistant a.耐火的fixed part 固定件flash signal light 闪光信号灯flat fillet seam 平角焊缝flexibility n. 挠性flexible coupling 挠性联轴节float launching 漂浮下水floatability n. 漂浮性floating positively 正浮floating production storage unit(FPSU)浮式生产储油轮flood v. 进水floodability n. 不沉性floor plate 肋板fluctuate v. 波动fluctuation n. 波动flush v. 清洗flushing agent 清洗剂flux n. 焊剂flywheel n 飞轮foam n. 泡沫folding machine 折边机for home use 国内用forced lubrication 强制润滑forced ventilation 机械通风fore perpendicular 艏垂线forecastle n. 艏楼foreign trade 外贸forging n. 锻造formation n. 构成,结构frame n. 肋骨framework n. 框架framing block 肋骨框架分段free end 自由端freeboard n. 干舷freighter n. 货船Freon n. 氟利昂frequency n. 频率frequency difference latching频率锁定frequency regulation 调频fresh water (F.W.)淡水fresh water production plant造水装置friction resistance 摩擦阻力fuel n. 燃料fuel nozzle 喷油嘴fuel oil 燃油fuel oil (F.O.)燃油fuel pipeline 燃油管系full-load a. 满载的full-load displacement 满载排水量funnel n. 烟囱galley n. 厨房gantry n. 龙门架gas cutting 气割gas tight seal 气密密封gas turbine engine 燃气轮机gas welding 气焊gear n. 齿轮gear drive 齿轮转动geo-physical propecting vessel地球物理探测船GL 西德劳氏船级社grant v. 给予……的权利gravity centre 重心gravity welding 重力焊groove v. 开坡口ground v. 接地group n. (企业)集团growth n. 生长,发育guarantee n. v. 保证general description 概述general-purpose a.通用的generating set 发电机组geometrical characteristics 几何特征geometrical principle 几何原理gravity launching 重力下水guided-missile frigate 导弹护卫舰gyro n. 陀螺仪gyro compass 陀螺罗经,回转罗经H.D.Heavy Machinery Co. Ltd. H.D. 重机股份有限公司Halogen n. 卤素hand control 手控hand level 手柄hand steering 手动操作hand wheel 手轮handle v. 操纵harbour n. 港口,停泊harbour generator 停泊发电机hardware n. 硬件hatch trunk 舱口围壁hawsepipe n. 锚链筒he water pressure system 水压系统headquarters n. 总部,厂部headroom n. 甲板间高度heat exchanger 热交换器heating n. 供暖heavy current n. 强电heavy oil 重油heel n. 横倾hereinbelow adv. 在下文high frequency 高频high-speed boat 高速艇horizontal a.水平的,卧式的horsepower(hp) n. 马力hose n. 软管hot processing 热加工hot work 火工hull n. 船体hull cleanness 船体光顺性hull construction 船体结构hull form 船型hull line 船体线型hull structure 船体结构human brain 人脑humidify v. 增湿hydraulic a. 液压的hydraulic fluid 液压流体hydraulic machine 液压机hyperbolic curve receive双曲线定位仪identify vt.识别ignite v. 点火ignition n. 点火illumination n. 照明illustration n. 生动的说image display system 图象显示系统IMCO 政府间海事协商组织impact n. 冲击implication n. 含义impulsator n. 推动器,脉冲发生器impulse-type a.脉冲式的impurity n. 杂质inclination n. 倾斜inclination test 倾斜试验incline v. 倾斜index n. 索引indication n. 显示indicator n. 显示仪indicator n. 指示器indicator light 指示灯indicator valve示功阀inert gas 惰性气体inertia n. 惯性inertia platform 惯性平台inevitable a.不可避免的initial metacentric height 初稳心高inject n. 喷射injecting system 喷油系统injector n. 喷油器inner bottom longitudinal 内底纵骨inner bottom plate 内底板inner ring 内环input n. v. 输入inspector n. 质检员installation n. (船上)安装installation error 安装误差instancy speed 瞬时速度instrument n. 仪表,仪器insulating material 绝缘材料insulation n. 绝缘intake n. 吸入intake port 汲气口intake valve 进气阀integral casting 整体浇铸intention n. 意向intercommunication (intercom)n.内通,内部通讯interfering moment 干扰力矩intermediate bearing 中间轴承intermediate shaft 中间轴internal combustion engine 内燃机international authorities 国际当局Internet 因特网(国际互连网)introduce v. 引进,引入,介绍iron powder electrode 铁粉焊条jig n. 胎架joint design 联合设计journal n. 轴颈keel n. 龙骨keel plate 龙骨板keep station 定位kerosene test 煤油实验key enterprise 骨干企业kilohertz 千赫kinetic energy 动能knot n. 节labyrinth n. 迷宫,曲径land-based a. 路基的landing-place n. 码头lap joint 搭接接头large-computer(mainframe computer) n. 大型(计算)机,主机lay v. 敷设length n. (一)节,(一)段level n. 液位level gauge 液位计level relay 液位继电器license n. 许可证life line 生命线life-belt n. 救生圈life-boat n. 救生艇life-jacket n. 救生衣life-or-death a.生死攸关的life-raft n. 救生筏life-saving n. 救生lifting capacity 起重能力light current 弱电lighting n. 照明light-ship displacement (light-load displacement)轻载排水量lines lofting 线型放样lines offsets 型值lines plan 线型图lining n. 衬垫load distribution 负荷分配load line mark 载重线标志load transfer 负荷转移local strengthening 局部加强locate v. 定位lock washer 锁紧垫片lofting n. 放样log n. 计程仪logical a.逻辑的long bridge 长桥楼longitudinal a.纵向的longitudinal (uniflow)scavenge直流扫气longitudinal bulkhead 纵隔舱壁longitudinal framing 纵向构架loop n. 回路loop antenna 环状天线Loran receiver 劳兰定位仪Loudspeaker n. 扬声器low speed 低速lower deck 下甲板LR 英国劳氏船级社lube oil 润滑油lube oil(L.O.)滑油lube oil pump 滑油泵lubricant n. 润滑剂lubricant film 润滑油膜lubricating oil 滑油lubrication system 滑油系统M.E.engine room 主机舱Machine v. 机加工machinery n. 机械machinery set 机组machinery workshop 机电车间machining n. 机加工machining workshop 机加工车间magnetic compass 磁罗经magnetic field 磁场magnetic needle 磁针magnetic object 磁性物体magnifier n. 放大器magnify v. 放大magnitude n. 大小main bearing 主轴承main engine (ME) 主机main generating set 主发电机组Main Group 1 第一大部分main hull 主船体main network 主电网main power station 主电站main switchboard 主配电板maintenance n. v. 维护,保养marker n. 厂商man power resource 人力资源management n. 生产管理maneuver v. n. 操纵maneuverability n. 操纵性maneuvering console 操纵台maneuvering system 操纵系统manual work 手工劳动manufacture n. &v. 生产,制造marine crane 船用起重机marine diesel engine 船用柴油机marine engineer 机电工程师marine engineering research institute造机研究所marine geological research vessel海洋地质调查船mark v. 标出mast lightmaster controller 主令控制器Master degree 硕士学位material n. 材料material marking 下料mathematical a.数学的mathematical lofting skill数学放样技术maximum(max.)n. 最大means n. 手段,工具measurement laboratory 计量实验室measuring meter 测量仪表measuring point 测量点mechanical energy 机械能mechanical launching 机械下水mechanical processing 机加工mechanical unit 机械装置medium speed 中速medium wave 中波medium-computer n.中型(计算)机member n. 构件memory n. 储存器,内存memory and storage system储存系统merchant ship 民用船mercury n,水银meridian n. 子午线metacentre n. 稳心metal recovery 金属回收率metallic equipment 冶金设备microclimate n. 小气候microcomputer n. 微机microprocessor n. 微处理器midship n. a. adv. 舯部military ship 军用船miller n. 铣床minicomputer n. 小型(计算)机minimize v. 降至最低minus push 负推力minus value 负值miscellaneous a. 杂项的mobilize v. 动员model case 样箱model plate 样板model rod 样棒moderate a. 中型的modern enterprise system现代企业制度modus n. 操纵法(pl. modi)monitor v. 监视monitoring device 监控装置moor v. 系泊motive power 原动力motor n. 电动机mould loft 放样台mouth n. 河口moving part 运动件multi-purpose a.多用途的,综合的multi-stage n. 多级mutual benefit 互惠互利nautical mile 海里naval architect 造船设计师navigating instrument 导航仪器navigating zone 航区navigation computer 导航计算机navigation equipment 导航设备navigational light 航行灯navy n. 海军navy underway replenishment ship海军航行补给船NC cutting machine 数控切割机nerve cell 神经细胞nesting n. 套料network n. 电网nil n. 零,无NK 日本海事协会non –ferrous metal 有色金属non-restrictive a.自由的,不受限制的non-standard product 非标产品non-transparent a. 不透明的normal displacement 正常排水量normal shipping 正常营运nozzle n. 喷嚏numbering system 计算系统numeral n. 数字numerical control (NC)数控numerical control cutter 数控切割机nut n. 螺母observation n. 观察occasion n. 盛事,盛举ocean-going vessel 远洋船oceanographic research vessel海洋调查船offshore service 近海作业oil charging piping 注油管系oil consumption 油耗oil filling port 注油口oil mist 油雾oil refinery 炼油厂oil tanker 油船oil-resistant a.耐油的oil-tight n. 油密Omega/satellite integrated navigation instrument 奥米加/卫星导航系统one-side welding单面焊接,双面成形one-way a.单向的open chamber 开放式燃烧室open circulation 开放循环opening n. 开口operating cycle 工作周期operation n. 施工operation n. 运行,运转operation surroundings 作业环境operator n. 操纵员opportunity n. 机遇optical projector 光学仪器optics n. 光学orbit n. 轨道order n. v. 订单,定购oscillation n. 振荡oscillation current 振荡电流outboard adv. 向舷外outer appearance 外观outer ring 外环outfitting n. 舾装output n. 输出overload v. 过载owner n. 船东owner’s representative船东代表oxide n. 氧化皮paint n. 油漆pain-taking a.艰巨的painting n. 涂装painting n. 涂装,油漆工艺palletizing management 托盘管理parallel n. 并联v. 并车parallel of generators 发电机并车parameter n. 参数part n. 部件,机械部件part fabrication 部装particle n. 颗粒party n. (谈判或合同之)一方passage n. 通道passageway n. 通道passenger-cargo vessel 客货船performance n. 性能permanently adv. 永久的perpendicular n. 垂线personnel n. 全体人员personnel n. 人员,人事phase angle 相角phase sequence 相序phase –sensitive rectifier相敏整流器physical quantity 物理量physical-chemical experiment理化实验physical-chemical experimental center理化中心实验室pillar n. 支柱pilot n. 驾驶员,领航员,舵轮pipe connection 管子接头pipe flange 管子法兰piping system 管系piston pin 活塞环piston pin 活塞梢piston stroke 活塞冲程pitch n. 纵摇plan n. 图纸plane n. 平面plane v. 整平planing machine 校平机plant n. (成套机电)设备platform n. 平台pneumatic tool 气动工具pointing of direction 指向poisonous gas 有毒气体pollution n. 污染poop n. 艉楼port n. 左舷portable light 手提灯postdoctoral centre 博士后工作站potable water 饮用水pour v. 涌入,源源不断power amplifier 功率放大器power plant 动力装置,(火力)电厂power station 电站power supply 电源,供电power system 电力系统,动力系统practice n. 习惯做法preamplifier n. 前置放大器pre-combustion chamber预燃燃烧室pre-heat v. 预热pressure container 压力容器pressure relay 压力继电器pressure sensor 压力传感器pressure tank 压力柜pretreat v. 预处理primary radio transmitter主无线电发信机prime mover 原动机primer n. 底漆primer painting 涂底漆principle dimensions 主尺度process n. 工艺,流程v. 加工,处理production efficiency 生产效率production line 生产线production procedure 生产程序program n. 程序projection plane 投影面prolong v. 延长promote v. 促进,晋升propeller n. 螺旋桨proportion n. 比例propulsion efficiency 推进效力propulsion plant 推进装置protection type 保护式provision n. 食品pump n. 汞purity v. 净化push rod 顶杆push-pull magnetic amplifier推挽磁放大器pyramid method 正装法quality assurance 质量保证quality control 质量控制quality management 质量管理quality policy 质量方针quay n. (顺岸式)码头quiescent a.安静的radar n. 雷达radio beacon station 导航台radio communication equipment无线电通讯设备radio directional finder 无线电测向仪radio message 无线电报radio receive 无线电接收机radio room 报房radio station 电台radio transmitter 无线电发信机radio wave 无线电波range n. 航程range v. 测距range display 航程显示器range unit 航程装置rated power 额定功率rated value 额定值reaction n. 反作用力reading n. 读数receiver n. 接收器reciprocating movement 往复运动rectification n. 矫正,整顿rectify v. 整流,滤波reduction gear 减速齿轮reduction gearbox 减速齿轮箱reduction unit 减速装置reduction with an astern clutch带到车离合器的减速reefer n. (俗)冷藏船,冰箱reflect v. 反射refrigerating plant 制冷装置register n. (机)验船师register vt. 登记,注册regulation n. 登记regulator n. 调整器relative humidity 相对湿度relative motion 相对运动relay contactor 继电器remains n. 残余remote control 遥控remote control station 遥控站rescue v. n. 救援rescue frequency 救援频率rescue transmitter 救援发信机resemble v. 相似reserve buoyancy 储备浮力reservoir n. 容器resistance n. 阻力resistance heat 电热阻rest v. 靠左retaining washer 保护垫片retake v. 回收,取回reversal n. 换向reverse v. 反向逆转reverse power 逆功率reversing system 换向机构revolution n. 旋转rigid a. 刚性的ring seam 环缝rock arm 摇臂roll n. 横摇roller machine 滚床room n. 余地rope n. 缆索rotary movement 旋转运动rotate v. 旋转rotating direction 旋转方向rotation n. 旋转度rotor n. 转子rough sea 波涛汹涌roughness n. 粗糙度routine n. 例行公事rpm 转速rudder n. 舵rudder angle indicator 舵角指示器rudder carrier 舵承,舵托rudder stock 舵轴,舵杆rudder stopper 舵角限制器rules n. 规范,规则running n. 经营管理rust preventative 防锈剂rust prevention 防锈rust removal 除锈rust-proof a.防锈的safeguard v. 捍卫safety valve 安全阀salt content 含盐量sanitary water 卫生水saturated steam 饱和蒸汽scavenge v. n. 扫气scavenge box 扫气箱scavenge flow 扫气气流scavenge pattern 扫气型式screen n. 荧光屏screw shaft 螺旋桨轴sea damage 海损sea trial 试航sea water (SW)海水sea-chart room 海图室seakeeping performances航海性能,试航性seal n. v. 密封sealing agent 密封剂sealing gasket 密封垫片sealing ring 密封圈search light 探照灯seasick a.晕船seat n. 座seating n. 基座section n. 总段self excitation 自励self-designed a.自行设计的self-regulated device 自我调节机构semi-conductor n. 半导体SEMT of France 法国热机协会senior engineer 高级工程师sensibility n. 灵敏度separation n. 分离separator n. 分离器serialize vt.使……成系列service n. 公共基础设施service engineer 服务工程师service life 使用寿命service tank 日用柜servo motor 伺服电动机settle v. 沉淀settling tank 沉淀柜shaft bracket 艉轴架,人字架shaft system 轴系shape processing 成形加工shear machine 剪切机shed v. 放射,散发sheer n. 脊弧sheet plate 薄板shell n. 壳板shell plating 外壳列板shell structure 外板结构ship equipment 船舶结构ship general 总体ship outfitting 船舾ship system 船舶系统shipbuilding n. 造船shipbuilding industry 造船工业shipbuilding technology research institute造船工艺研究所shipping n. 航运shipyard(yard)n. 船厂shop trial 车间实验shore electricity box 岸电箱short circuit 短路short wave 短波short-range a.短途的shot-blast v. 喷丸shot-blasting 喷丸处理side n. 船侧side girderside light 舷灯side plate 弦侧板side structure 船侧结构signal n. 信号signal light 信号灯signal processor 信号处理器silicon n. 硅silicon control rectifier(SCR)可控硅single bottom 单底single-action a.单作用single-rudder n. 单舵single-stage n. 单级single-screw n. 单桨site architect 现场造船师site supervisor 现场监控师sketch n. 草图slide-block n. 滑板,导块sliding distance 滑行距离slipway n. (倾斜)船台slipway taper 船台斜面small metacentric angle 小倾角socialist market economy社会主义市场经济software n. 软件soil n. 土壤SOLAS 国际海上人命安全公约SOS 遇难信号sound energy 声能sound insulation 隔音sound power telephone 声力电话sound speed 声速sound wave 声波sounder n. 测深仪sources of power supply 能源space n. 舱室space n. 空间spare gears 备品spare parts(spares)备件special power supply 特种电源speed indicator 航速指示器speed reduction 减速speed servo system 速度随动系统spring n. 弹簧squeeze n. v. 挤压stability n. 稳性stabilizer n. 减摇鳍stabilizing unit 减摇装置staff member 职员stage n. 级stainless steel 不锈钢stand v. 经受standard n. 标准standard displacement 标准排水量stand-by n. 备用stand-by generating set 备用发电机starboard n. 右舷start v. 动身,出发starting system 起动系统starting valve 启动阀state v. 说明state-specified a.部颁的station v. 驻扎steadiness n. 稳定性steam &aux. boiler system蒸汽与副锅炉系统steel plate pretreatment 钢板预处理steel structure 钢结构steel wire 钢丝steering gear 操舵装置steering gear 舵机steering gear room 舵机房steering mechanism 操舵机构steering wheel 舵轮stem n. 艏柱stern n. 船艉,艉柱stern tube 艉轴管stiffener n. 扶强,加强筋storage tank 贮存柜store-room n. 储藏室straight line 直线straight seam 直焊缝strength test 强度试验stringer n. 纵通材structural material 结构材料structure n. 结构,构件stud n. 螺柱stuffing box 填料函subway shield 地铁盾构suck v. 吸入suction (induction) stroke 汲气冲程suction port 吸入口sufficient a.足够的,充足的sum n. (数)二树之和supercomputer n. 巨型(计算)机superstructure n. 上层建筑supervision n. 监督,监造supply vessel 补给,工作船support n. 支撑物surface treatment 表面处理surveyor n. (船)验船师survive v. 幸存,死里逃生sustain v. 支撑,支持swirl chamber 涡流式燃烧室swirl resistance 涡流式阻力switch n. 开关symbol n. 符号symmetrical a.对称的synchro (selsyn)n. 自整角机synchro signal transmitter 自整角机讯号发送器synchronous device 同步装置synchronous follower 同步随动件talent n. 人才,有才能的technical staff 全体技术人员technical force 技术力量technical service 技术服务technical specification (spec)技术规格书technical term 技术术语telegraph n. 传令钟teleprinter n. 电传打字机teleperature relay 温度继电器temporarily adv. 临时地temporary emergency power supply临时应急电源terminal n. 终端testing n. 调试testing facilities 测试设备testing instrument 测试仪器test & trials 试验与试航TEU reefer container ship 冷风集装箱船the ambient air 大气the application software 应用软件the block coefficient 方型系数the brake horse power (BHP)轴马力,制动马力the breath moulded 型宽the central processing unit (CPU)中央处理单元the centralized control room (the controlroom)集控室the controllable pitch propeller (CPP)可调螺距桨the critical path method (CPM) 各种计划节点配合the data base management system (DBMS)数据库管理系统the depth moulded 型深the design water plane 设计水线面the design water plane coefficient设计水面线系数the displacement coefficient 排水量系数the earth magnetic field 地球磁场the effective horsepower 有效马力the fire main 消防总管the fixed pitch propeller 固定螺距桨the future type 未来型the graphic processing software图像处理软件the intertia navigation system惯性导航系统the integral stud anchor chain 整体锚链the language system 语言系统the length B.P.两柱间长the length overall 全长the length W.L.水线长the living quarters 生活区the longitudinal prismatic coefficient纵向菱形系数the metacentre of transversal inclination 横倾稳心the middle longitudinal cross section舯横剖面the midship transversal cross section coefficient 舯横截面系数the net registered tonnage 净登记吨位the North Pole 北极the office automation (OA)办公自动化the operating system (OS)操作系统the painting outfitting 涂装the parties concerned 有关方面the propulsion plant 推进装置the rated frequency 额定功率the rated horsepower 额定马力the roll period 横摇周期the satellite navigation system卫星导航系统the system software 系统软件the total longitudinal bend 总纵弯曲the total longitudinal strength 总纵强度the total tonnage 总吨位thermal mechanism 热力机械thermal stress 热应力thermometer n. 温度计thread v. 攻螺纹thrust bearing 推力轴承thrust end 推力端thrust ring 推力环thrust shaft 推力轴thyristor n. 硅可控整流器,可控硅tier n. (船)层TIG钨极惰性气体焊tightness test 密性试验time vt. 确定……的时间timing gear 准时机构title n. 职称,头衔tonnage n. 吨位top people 上层人物top side plate 弦侧顶板torsional vibration 扭振torsional moment 扭距TQC全面质量管理transceiver n. 收发报机transfer pump 输送泵transistor amplifier 晶体管放大器transistor controller 晶体控制器transistor loop 晶体管回路transmitter n. 发射机,发送器transportation n. 输送transversal a. 横向的transversal bulkhead 横隔舱壁transversal scavenge 横流扫气transversal stability 横稳性treatment plant 处理装置trend n. 趋势trial-and-error a.反复的通过试验找出错误的trim n. 纵倾trunk-piston n. 筒形活塞T-type joint T型接头tuition n. 学费turbine oil 透平油turbocharger n. 涡轮废气增压器turning ability 回转性turning circle 回转半径turning gear 盘车机构turning motion 回转twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU)20英尺国际标准集装箱twin-engine incoporation 双机并车twinkle v. 闪烁twin-rudder n. 双舵twin-screw n. 双桨two-way a. 双向的ultra short wave 超短波UMS 无人机舱under voltage 欠电压uneven a. 不均匀uniform a. 均匀的unload v. 卸载upper deck 上甲板upset v. (船只)倾覆vacuum n. 真空validate vt. (使)生效valve mechanism 阀机构vaporize v. 汽化velocity n. 速度ventilating pipe 通风管ventilation &air-conditioning system通风与空调系统ventilator n. 通风机vertical a. 垂直的,直立式的vertical seam 垂直焊缝vertical welding 立焊vibration n. 振动viscosity n. 粘度visible range 视距visual telegraph 灯光传令钟visual-acoustical signal 灯光音响信号voltage n. 电压voltage latching 电压锁定voyage n. 航行waste heat 余热water head 压头water inlet pipe 进水管water jacket 水套water pressure test 水压试验water supply 水源,自来水water supply system 供水系统water vapour 水蒸气waterline 水线watertight a. 水密的water-tight test 水密试验wave impact 波浪冲击力wave-forming (wave-making) resistance兴波阻力wear n. v. 磨损weather post 露天部位weight calculation 重量计算welder n. 焊工,焊机welding n. 焊接welding laboratory(lab)焊接试验室welding machine 焊机welding procedure 焊接方法(工艺)welding seam 焊缝welding wire 焊丝well adv. 完全有理由wheel steering 随从操舵,舵轮操舵wheel house n. 驾驶室whereby adv. 靠那个wing buoyant tank 减摇水舱wire cable 钢索work n. 功working condition 工况working principle 工作原理working schedule 生产进度working site 现场workmanship n. 工艺,流程X-ray photo X光照片yaw n. 偏航角。