Trapezoid Fuzzy Linguistic WGA Operator

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:272.26 KB

- 文档页数:8

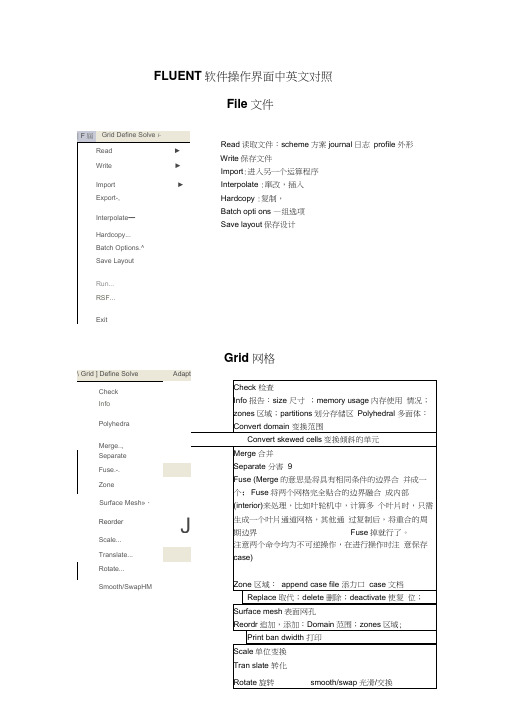

FLUENT 软件操作界面中英文对照File 文件Read 读取文件:scheme 方案journal 日志 profile 外形 Write 保存文件 Import :进入另一个运算程序 Interpolate :窜改,插入Hardcopy :复制,Batch opti ons —组选项Save layout 保存设计 Grid 网格| F 屆 Grid Define Solve i-Read► Write►Import ► Export-, Interpolate —Hardcopy...Batch Options.^Save LayoutRun...RSF...ExitDefine Models模型:solver解算器Pressure based 基于压力Den sity based基于密度末解用丁 pressure based,雀改用Censity based 岀观不苻合秦相36的摄不,请甸pres 羊WE base d Al density based 慎仆则迢.41刊卜 IS 况?北外.血OC ・EHU ^ cotipled >(/^ ptiaw ccupl ed simple 可这孔 & pimple ijEpiso 逞划.--■轟=Sortg 冲-丸布时制* ^jfe-5-6 1844DOden ba&ed 亘工F 吋.压聲血ptessurt ba$«i 适可于那可乐册斤"dens Ply based 把丸“河悴掏t :至殳嗟之一.刑牛可爪門d 的创R 监當歎1一,般如人锻暮叫人丄有用 轴怀,火薩墟迭牛才H5)-0 程:yje8D8-丸布门 1叫;20GS-3-7 10-2ODQ歆;I :谢PrflSsdrfl-Bawd Soker ^Fluflnt 它星英于压力快的束解孤便丹的圮压力修止畀法"求释旳控制片悝足标联式的,擅K 家鮮不町压縮舐Mb 对于町压砂也可旦索麟;Fk«nl 6-3 tl 前的I 板』冷孵臥 B fjS4^r«^at«d &Olvar fli Cfruptod Solvtr,的实也fltje Pr#4iurft-ea5<KJ ScFvAi 约两种虽幵方ib应理拈Fluent 氐J 眇坝犢型小的.它拈垒于曲喪红旳求聲塞,最辑的出H .也桿 艮先■那式的.丰誓■載密式冇Roz AU$hk>谏方法的初和&让Fhwrt 耳有比我甘的求IT 可压胃(说 劫謹力,們耳帕榕式淮冇琴加IF 科限闾辉,倒比还丰A 完荐匚Coupted 的算送t 对子慨站何Hh 地们足便用円匕口讷油皿购 加£未处為 性上世魅端计棒低逢刈趾.擁说的DansJty-Bjiwd Solver F ft St SiMPLEC, P 怡DE 些选以的.闪为進些ffliQl ;力修止鼻袪・不金在这种类崖的我押■中氏现泊I 建址祢匹足整用Fw»ur 护P.sed Solver 堺决昧的利底*implicit 隐式, explicit 显示Space 空间:2D , axisymmetric (转动轴), axisymmetric swirl (漩涡转动轴);Time 时间 :steady 定常,unsteady 非定常 Velocity formulatio n 制定速度: absolute 绝对的;relative 相对的Gradient option 梯度选择:以单元作基础;以节点作基础;以单元作梯度的最小正方形。

DOI: 10.1126/science.1094786, 441 (2004);304Science et al.Mitchell S. Abrahamsen,Cryptosporidium parvum Complete Genome Sequence of the Apicomplexan, (this information is current as of October 7, 2009 ):The following resources related to this article are available online at/cgi/content/full/304/5669/441version of this article at:including high-resolution figures, can be found in the online Updated information and services,/cgi/content/full/1094786/DC1 can be found at:Supporting Online Material/cgi/content/full/304/5669/441#otherarticles , 9 of which can be accessed for free: cites 25 articles This article 239 article(s) on the ISI Web of Science. cited by This article has been /cgi/content/full/304/5669/441#otherarticles 53 articles hosted by HighWire Press; see: cited by This article has been/cgi/collection/genetics Genetics: subject collections This article appears in the following/about/permissions.dtl in whole or in part can be found at: this article permission to reproduce of this article or about obtaining reprints Information about obtaining registered trademark of AAAS.is a Science 2004 by the American Association for the Advancement of Science; all rights reserved. The title Copyright American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1200 New York Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20005. (print ISSN 0036-8075; online ISSN 1095-9203) is published weekly, except the last week in December, by the Science o n O c t o b e r 7, 2009w w w .s c i e n c e m a g .o r g D o w n l o a d e d f r o m3.R.Jackendoff,Foundations of Language:Brain,Gram-mar,Evolution(Oxford Univ.Press,Oxford,2003).4.Although for Frege(1),reference was established rela-tive to objects in the world,here we follow Jackendoff’s suggestion(3)that this is done relative to objects and the state of affairs as mentally represented.5.S.Zola-Morgan,L.R.Squire,in The Development andNeural Bases of Higher Cognitive Functions(New York Academy of Sciences,New York,1990),pp.434–456.6.N.Chomsky,Reflections on Language(Pantheon,New York,1975).7.J.Katz,Semantic Theory(Harper&Row,New York,1972).8.D.Sperber,D.Wilson,Relevance(Harvard Univ.Press,Cambridge,MA,1986).9.K.I.Forster,in Sentence Processing,W.E.Cooper,C.T.Walker,Eds.(Erlbaum,Hillsdale,NJ,1989),pp.27–85.10.H.H.Clark,Using Language(Cambridge Univ.Press,Cambridge,1996).11.Often word meanings can only be fully determined byinvokingworld knowledg e.For instance,the meaningof “flat”in a“flat road”implies the absence of holes.However,in the expression“aflat tire,”it indicates the presence of a hole.The meaningof“finish”in the phrase “Billfinished the book”implies that Bill completed readingthe book.However,the phrase“the g oatfin-ished the book”can only be interpreted as the goat eatingor destroyingthe book.The examples illustrate that word meaningis often underdetermined and nec-essarily intertwined with general world knowledge.In such cases,it is hard to see how the integration of lexical meaning and general world knowledge could be strictly separated(3,31).12.W.Marslen-Wilson,C.M.Brown,L.K.Tyler,Lang.Cognit.Process.3,1(1988).13.ERPs for30subjects were averaged time-locked to theonset of the critical words,with40items per condition.Sentences were presented word by word on the centerof a computer screen,with a stimulus onset asynchronyof600ms.While subjects were readingthe sentences,their EEG was recorded and amplified with a high-cut-off frequency of70Hz,a time constant of8s,and asamplingfrequency of200Hz.14.Materials and methods are available as supportingmaterial on Science Online.15.M.Kutas,S.A.Hillyard,Science207,203(1980).16.C.Brown,P.Hagoort,J.Cognit.Neurosci.5,34(1993).17.C.M.Brown,P.Hagoort,in Architectures and Mech-anisms for Language Processing,M.W.Crocker,M.Pickering,C.Clifton Jr.,Eds.(Cambridge Univ.Press,Cambridge,1999),pp.213–237.18.F.Varela et al.,Nature Rev.Neurosci.2,229(2001).19.We obtained TFRs of the single-trial EEG data by con-volvingcomplex Morlet wavelets with the EEG data andcomputingthe squared norm for the result of theconvolution.We used wavelets with a7-cycle width,with frequencies ranging from1to70Hz,in1-Hz steps.Power values thus obtained were expressed as a per-centage change relative to the power in a baselineinterval,which was taken from150to0ms before theonset of the critical word.This was done in order tonormalize for individual differences in EEG power anddifferences in baseline power between different fre-quency bands.Two relevant time-frequency compo-nents were identified:(i)a theta component,rangingfrom4to7Hz and from300to800ms after wordonset,and(ii)a gamma component,ranging from35to45Hz and from400to600ms after word onset.20.C.Tallon-Baudry,O.Bertrand,Trends Cognit.Sci.3,151(1999).tner et al.,Nature397,434(1999).22.M.Bastiaansen,P.Hagoort,Cortex39(2003).23.O.Jensen,C.D.Tesche,Eur.J.Neurosci.15,1395(2002).24.Whole brain T2*-weighted echo planar imaging bloodoxygen level–dependent(EPI-BOLD)fMRI data wereacquired with a Siemens Sonata1.5-T magnetic reso-nance scanner with interleaved slice ordering,a volumerepetition time of2.48s,an echo time of40ms,a90°flip angle,31horizontal slices,a64ϫ64slice matrix,and isotropic voxel size of3.5ϫ3.5ϫ3.5mm.For thestructural magnetic resonance image,we used a high-resolution(isotropic voxels of1mm3)T1-weightedmagnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo pulse se-quence.The fMRI data were preprocessed and analyzedby statistical parametric mappingwith SPM99software(http://www.fi/spm99).25.S.E.Petersen et al.,Nature331,585(1988).26.B.T.Gold,R.L.Buckner,Neuron35,803(2002).27.E.Halgren et al.,J.Psychophysiol.88,1(1994).28.E.Halgren et al.,Neuroimage17,1101(2002).29.M.K.Tanenhaus et al.,Science268,1632(1995).30.J.J.A.van Berkum et al.,J.Cognit.Neurosci.11,657(1999).31.P.A.M.Seuren,Discourse Semantics(Basil Blackwell,Oxford,1985).32.We thank P.Indefrey,P.Fries,P.A.M.Seuren,and M.van Turennout for helpful discussions.Supported bythe Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research,grant no.400-56-384(P.H.).Supporting Online Material/cgi/content/full/1095455/DC1Materials and MethodsFig.S1References and Notes8January2004;accepted9March2004Published online18March2004;10.1126/science.1095455Include this information when citingthis paper.Complete Genome Sequence ofthe Apicomplexan,Cryptosporidium parvumMitchell S.Abrahamsen,1,2*†Thomas J.Templeton,3†Shinichiro Enomoto,1Juan E.Abrahante,1Guan Zhu,4 Cheryl ncto,1Mingqi Deng,1Chang Liu,1‡Giovanni Widmer,5Saul Tzipori,5GregoryA.Buck,6Ping Xu,6 Alan T.Bankier,7Paul H.Dear,7Bernard A.Konfortov,7 Helen F.Spriggs,7Lakshminarayan Iyer,8Vivek Anantharaman,8L.Aravind,8Vivek Kapur2,9The apicomplexan Cryptosporidium parvum is an intestinal parasite that affects healthy humans and animals,and causes an unrelenting infection in immuno-compromised individuals such as AIDS patients.We report the complete ge-nome sequence of C.parvum,type II isolate.Genome analysis identifies ex-tremely streamlined metabolic pathways and a reliance on the host for nu-trients.In contrast to Plasmodium and Toxoplasma,the parasite lacks an api-coplast and its genome,and possesses a degenerate mitochondrion that has lost its genome.Several novel classes of cell-surface and secreted proteins with a potential role in host interactions and pathogenesis were also detected.Elu-cidation of the core metabolism,including enzymes with high similarities to bacterial and plant counterparts,opens new avenues for drug development.Cryptosporidium parvum is a globally impor-tant intracellular pathogen of humans and animals.The duration of infection and patho-genesis of cryptosporidiosis depends on host immune status,ranging from a severe but self-limiting diarrhea in immunocompetent individuals to a life-threatening,prolonged infection in immunocompromised patients.Asubstantial degree of morbidity and mortalityis associated with infections in AIDS pa-tients.Despite intensive efforts over the past20years,there is currently no effective ther-apy for treating or preventing C.parvuminfection in humans.Cryptosporidium belongs to the phylumApicomplexa,whose members share a com-mon apical secretory apparatus mediating lo-comotion and tissue or cellular invasion.Many apicomplexans are of medical or vet-erinary importance,including Plasmodium,Babesia,Toxoplasma,Neosprora,Sarcocys-tis,Cyclospora,and Eimeria.The life cycle ofC.parvum is similar to that of other cyst-forming apicomplexans(e.g.,Eimeria and Tox-oplasma),resulting in the formation of oocysts1Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science,College of Veterinary Medicine,2Biomedical Genom-ics Center,University of Minnesota,St.Paul,MN55108,USA.3Department of Microbiology and Immu-nology,Weill Medical College and Program in Immu-nology,Weill Graduate School of Medical Sciences ofCornell University,New York,NY10021,USA.4De-partment of Veterinary Pathobiology,College of Vet-erinary Medicine,Texas A&M University,College Sta-tion,TX77843,USA.5Division of Infectious Diseases,Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine,NorthGrafton,MA01536,USA.6Center for the Study ofBiological Complexity and Department of Microbiol-ogy and Immunology,Virginia Commonwealth Uni-versity,Richmond,VA23198,USA.7MRC Laboratoryof Molecular Biology,Hills Road,Cambridge CB22QH,UK.8National Center for Biotechnology Infor-mation,National Library of Medicine,National Insti-tutes of Health,Bethesda,MD20894,USA.9Depart-ment of Microbiology,University of Minnesota,Min-neapolis,MN55455,USA.*To whom correspondence should be addressed.E-mail:abe@†These authors contributed equally to this work.‡Present address:Bioinformatics Division,Genetic Re-search,GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals,5MooreDrive,Research Triangle Park,NC27009,USA.R E P O R T S SCIENCE VOL30416APRIL2004441o n O c t o b e r 7 , 2 0 0 9 w w w . s c i e n c e m a g . o r g D o w n l o a d e d f r o mthat are shed in the feces of infected hosts.C.parvum oocysts are highly resistant to environ-mental stresses,including chlorine treatment of community water supplies;hence,the parasite is an important water-and food-borne pathogen (1).The obligate intracellular nature of the par-asite ’s life cycle and the inability to culture the parasite continuously in vitro greatly impair researchers ’ability to obtain purified samples of the different developmental stages.The par-asite cannot be genetically manipulated,and transformation methodologies are currently un-available.To begin to address these limitations,we have obtained the complete C.parvum ge-nome sequence and its predicted protein com-plement.(This whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the project accession AAEE00000000.The version described in this paper is the first version,AAEE01000000.)The random shotgun approach was used to obtain the complete DNA sequence (2)of the Iowa “type II ”isolate of C.parvum .This isolate readily transmits disease among numerous mammals,including humans.The resulting ge-nome sequence has roughly 13ϫgenome cov-erage containing five gaps and 9.1Mb of totalDNA sequence within eight chromosomes.The C.parvum genome is thus quite compact rela-tive to the 23-Mb,14-chromosome genome of Plasmodium falciparum (3);this size difference is predominantly the result of shorter intergenic regions,fewer introns,and a smaller number of genes (Table 1).Comparison of the assembled sequence of chromosome VI to that of the recently published sequence of chromosome VI (4)revealed that our assembly contains an ad-ditional 160kb of sequence and a single gap versus two,with the common sequences dis-playing a 99.993%sequence identity (2).The relative paucity of introns greatly simplified gene predictions and facilitated an-notation (2)of predicted open reading frames (ORFs).These analyses provided an estimate of 3807protein-encoding genes for the C.parvum genome,far fewer than the estimated 5300genes predicted for the Plasmodium genome (3).This difference is primarily due to the absence of an apicoplast and mitochondrial genome,as well as the pres-ence of fewer genes encoding metabolic functions and variant surface proteins,such as the P.falciparum var and rifin molecules (Table 2).An analysis of the encoded pro-tein sequences with the program SEG (5)shows that these protein-encoding genes are not enriched in low-complexity se-quences (34%)to the extent observed in the proteins from Plasmodium (70%).Our sequence analysis indicates that Cryptosporidium ,unlike Plasmodium and Toxoplasma ,lacks both mitochondrion and apicoplast genomes.The overall complete-ness of the genome sequence,together with the fact that similar DNA extraction proce-dures used to isolate total genomic DNA from C.parvum efficiently yielded mito-chondrion and apicoplast genomes from Ei-meria sp.and Toxoplasma (6,7),indicates that the absence of organellar genomes was unlikely to have been the result of method-ological error.These conclusions are con-sistent with the absence of nuclear genes for the DNA replication and translation machinery characteristic of mitochondria and apicoplasts,and with the lack of mito-chondrial or apicoplast targeting signals for tRNA synthetases.A number of putative mitochondrial pro-teins were identified,including components of a mitochondrial protein import apparatus,chaperones,uncoupling proteins,and solute translocators (table S1).However,the ge-nome does not encode any Krebs cycle en-zymes,nor the components constituting the mitochondrial complexes I to IV;this finding indicates that the parasite does not rely on complete oxidation and respiratory chains for synthesizing adenosine triphosphate (ATP).Similar to Plasmodium ,no orthologs for the ␥,␦,or εsubunits or the c subunit of the F 0proton channel were detected (whereas all subunits were found for a V-type ATPase).Cryptosporidium ,like Eimeria (8)and Plas-modium ,possesses a pyridine nucleotide tran-shydrogenase integral membrane protein that may couple reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH)and reduced nico-tinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)redox to proton translocation across the inner mitochondrial membrane.Unlike Plasmodium ,the parasite has two copies of the pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase gene.Also present is a likely mitochondrial membrane –associated,cyanide-resistant alter-native oxidase (AOX )that catalyzes the reduction of molecular oxygen by ubiquinol to produce H 2O,but not superoxide or H 2O 2.Several genes were identified as involved in biogenesis of iron-sulfur [Fe-S]complexes with potential mitochondrial targeting signals (e.g.,nifS,nifU,frataxin,and ferredoxin),supporting the presence of a limited electron flux in the mitochondrial remnant (table S2).Our sequence analysis confirms the absence of a plastid genome (7)and,additionally,the loss of plastid-associated metabolic pathways including the type II fatty acid synthases (FASs)and isoprenoid synthetic enzymes thatTable 1.General features of the C.parvum genome and comparison with other single-celled eukaryotes.Values are derived from respective genome project summaries (3,26–28).ND,not determined.FeatureC.parvum P.falciparum S.pombe S.cerevisiae E.cuniculiSize (Mbp)9.122.912.512.5 2.5(G ϩC)content (%)3019.43638.347No.of genes 38075268492957701997Mean gene length (bp)excluding introns 1795228314261424ND Gene density (bp per gene)23824338252820881256Percent coding75.352.657.570.590Genes with introns (%)553.9435ND Intergenic regions (G ϩC)content %23.913.632.435.145Mean length (bp)5661694952515129RNAsNo.of tRNA genes 454317429944No.of 5S rRNA genes 6330100–2003No.of 5.8S ,18S ,and 28S rRNA units 57200–400100–20022Table parison between predicted C.parvum and P.falciparum proteins.FeatureC.parvum P.falciparum *Common †Total predicted proteins380752681883Mitochondrial targeted/encoded 17(0.45%)246(4.7%)15Apicoplast targeted/encoded 0581(11.0%)0var/rif/stevor ‡0236(4.5%)0Annotated as protease §50(1.3%)31(0.59%)27Annotated as transporter 69(1.8%)34(0.65%)34Assigned EC function ¶167(4.4%)389(7.4%)113Hypothetical proteins925(24.3%)3208(60.9%)126*Values indicated for P.falciparum are as reported (3)with the exception of those for proteins annotated as protease or transporter.†TBLASTN hits (e Ͻ–5)between C.parvum and P.falciparum .‡As reported in (3).§Pre-dicted proteins annotated as “protease or peptidase”for C.parvum (CryptoGenome database,)and P.falciparum (PlasmoDB database,).Predicted proteins annotated as “trans-porter,permease of P-type ATPase”for C.parvum (CryptoGenome)and P.falciparum (PlasmoDB).¶Bidirectional BLAST hit (e Ͻ–15)to orthologs with assigned Enzyme Commission (EC)numbers.Does not include EC assignment numbers for protein kinases or protein phosphatases (due to inconsistent annotation across genomes),or DNA polymerases or RNA polymerases,as a result of issues related to subunit inclusion.(For consistency,46proteins were excluded from the reported P.falciparum values.)R E P O R T S16APRIL 2004VOL 304SCIENCE 442 o n O c t o b e r 7, 2009w w w .s c i e n c e m a g .o r g D o w n l o a d e d f r o mare otherwise localized to the plastid in other apicomplexans.C.parvum fatty acid biosynthe-sis appears to be cytoplasmic,conducted by a large(8252amino acids)modular type I FAS (9)and possibly by another large enzyme that is related to the multidomain bacterial polyketide synthase(10).Comprehensive screening of the C.parvum genome sequence also did not detect orthologs of Plasmodium nuclear-encoded genes that contain apicoplast-targeting and transit sequences(11).C.parvum metabolism is greatly stream-lined relative to that of Plasmodium,and in certain ways it is reminiscent of that of another obligate eukaryotic parasite,the microsporidian Encephalitozoon.The degeneration of the mi-tochondrion and associated metabolic capabili-ties suggests that the parasite largely relies on glycolysis for energy production.The parasite is capable of uptake and catabolism of mono-sugars(e.g.,glucose and fructose)as well as synthesis,storage,and catabolism of polysac-charides such as trehalose and amylopectin. Like many anaerobic organisms,it economizes ATP through the use of pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructokinases.The conver-sion of pyruvate to acetyl–coenzyme A(CoA) is catalyzed by an atypical pyruvate-NADPH oxidoreductase(Cp PNO)that contains an N-terminal pyruvate–ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFO)domain fused with a C-terminal NADPH–cytochrome P450reductase domain (CPR).Such a PFO-CPR fusion has previously been observed only in the euglenozoan protist Euglena gracilis(12).Acetyl-CoA can be con-verted to malonyl-CoA,an important precursor for fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis.Gly-colysis leads to several possible organic end products,including lactate,acetate,and ethanol. The production of acetate from acetyl-CoA may be economically beneficial to the parasite via coupling with ATP production.Ethanol is potentially produced via two in-dependent pathways:(i)from the combination of pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehy-drogenase,or(ii)from acetyl-CoA by means of a bifunctional dehydrogenase(adhE)with ac-etaldehyde and alcohol dehydrogenase activi-ties;adhE first converts acetyl-CoA to acetal-dehyde and then reduces the latter to ethanol. AdhE predominantly occurs in bacteria but has recently been identified in several protozoans, including vertebrate gut parasites such as Enta-moeba and Giardia(13,14).Adjacent to the adhE gene resides a second gene encoding only the AdhE C-terminal Fe-dependent alcohol de-hydrogenase domain.This gene product may form a multisubunit complex with AdhE,or it may function as an alternative alcohol dehydro-genase that is specific to certain growth condi-tions.C.parvum has a glycerol3-phosphate dehydrogenase similar to those of plants,fungi, and the kinetoplastid Trypanosoma,but(unlike trypanosomes)the parasite lacks an ortholog of glycerol kinase and thus this pathway does not yield glycerol production.In addition to themodular fatty acid synthase(Cp FAS1)andpolyketide synthase homolog(Cp PKS1), C.parvum possesses several fatty acyl–CoA syn-thases and a fatty acyl elongase that may partici-pate in fatty acid metabolism.Further,enzymesfor the metabolism of complex lipids(e.g.,glyc-erolipid and inositol phosphate)were identified inthe genome.Fatty acids are apparently not anenergy source,because enzymes of the fatty acidoxidative pathway are absent,with the exceptionof a3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase.C.parvum purine metabolism is greatlysimplified,retaining only an adenosine ki-nase and enzymes catalyzing conversionsof adenosine5Ј-monophosphate(AMP)toinosine,xanthosine,and guanosine5Ј-monophosphates(IMP,XMP,and GMP).Among these enzymes,IMP dehydrogenase(IMPDH)is phylogenetically related toε-proteobacterial IMPDH and is strikinglydifferent from its counterparts in both thehost and other apicomplexans(15).In con-trast to other apicomplexans such as Toxo-plasma gondii and P.falciparum,no geneencoding hypoxanthine-xanthineguaninephosphoribosyltransferase(HXGPRT)is de-tected,in contrast to a previous report on theactivity of this enzyme in C.parvum sporo-zoites(16).The absence of HXGPRT sug-gests that the parasite may rely solely on asingle enzyme system including IMPDH toproduce GMP from AMP.In contrast to otherapicomplexans,the parasite appears to relyon adenosine for purine salvage,a modelsupported by the identification of an adeno-sine transporter.Unlike other apicomplexansand many parasitic protists that can synthe-size pyrimidines de novo,C.parvum relies onpyrimidine salvage and retains the ability forinterconversions among uridine and cytidine5Ј-monophosphates(UMP and CMP),theirdeoxy forms(dUMP and dCMP),and dAMP,as well as their corresponding di-and triphos-phonucleotides.The parasite has also largelyshed the ability to synthesize amino acids denovo,although it retains the ability to convertselect amino acids,and instead appears torely on amino acid uptake from the host bymeans of a set of at least11amino acidtransporters(table S2).Most of the Cryptosporidium core pro-cesses involved in DNA replication,repair,transcription,and translation conform to thebasic eukaryotic blueprint(2).The transcrip-tional apparatus resembles Plasmodium interms of basal transcription machinery.How-ever,a striking numerical difference is seenin the complements of two RNA bindingdomains,Sm and RRM,between P.falcipa-rum(17and71domains,respectively)and C.parvum(9and51domains).This reductionresults in part from the loss of conservedproteins belonging to the spliceosomal ma-chinery,including all genes encoding Smdomain proteins belonging to the U6spliceo-somal particle,which suggests that this par-ticle activity is degenerate or entirely lost.This reduction in spliceosomal machinery isconsistent with the reduced number of pre-dicted introns in Cryptosporidium(5%)rela-tive to Plasmodium(Ͼ50%).In addition,keycomponents of the small RNA–mediatedposttranscriptional gene silencing system aremissing,such as the RNA-dependent RNApolymerase,Argonaute,and Dicer orthologs;hence,RNA interference–related technolo-gies are unlikely to be of much value intargeted disruption of genes in C.parvum.Cryptosporidium invasion of columnarbrush border epithelial cells has been de-scribed as“intracellular,but extracytoplas-mic,”as the parasite resides on the surface ofthe intestinal epithelium but lies underneaththe host cell membrane.This niche may al-low the parasite to evade immune surveil-lance but take advantage of solute transportacross the host microvillus membrane or theextensively convoluted parasitophorous vac-uole.Indeed,Cryptosporidium has numerousgenes(table S2)encoding families of putativesugar transporters(up to9genes)and aminoacid transporters(11genes).This is in starkcontrast to Plasmodium,which has fewersugar transporters and only one putative ami-no acid transporter(GenBank identificationnumber23612372).As a first step toward identification ofmulti–drug-resistant pumps,the genome se-quence was analyzed for all occurrences ofgenes encoding multitransmembrane proteins.Notable are a set of four paralogous proteinsthat belong to the sbmA family(table S2)thatare involved in the transport of peptide antibi-otics in bacteria.A putative ortholog of thePlasmodium chloroquine resistance–linkedgene Pf CRT(17)was also identified,althoughthe parasite does not possess a food vacuole likethe one seen in Plasmodium.Unlike Plasmodium,C.parvum does notpossess extensive subtelomeric clusters of anti-genically variant proteins(exemplified by thelarge families of var and rif/stevor genes)thatare involved in immune evasion.In contrast,more than20genes were identified that encodemucin-like proteins(18,19)having hallmarksof extensive Thr or Ser stretches suggestive ofglycosylation and signal peptide sequences sug-gesting secretion(table S2).One notable exam-ple is an11,700–amino acid protein with anuninterrupted stretch of308Thr residues(cgd3_720).Although large families of secretedproteins analogous to the Plasmodium multi-gene families were not found,several smallermultigene clusters were observed that encodepredicted secreted proteins,with no detectablesimilarity to proteins from other organisms(Fig.1,A and B).Within this group,at leastfour distinct families appear to have emergedthrough gene expansions specific to the Cryp-R E P O R T S SCIENCE VOL30416APRIL2004443o n O c t o b e r 7 , 2 0 0 9 w w w . s c i e n c e m a g . o r g D o w n l o a d e d f r o mtosporidium clade.These families —SKSR,MEDLE,WYLE,FGLN,and GGC —were named after well-conserved sequence motifs (table S2).Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)expression analysis (20)of one cluster,a locus of seven adjacent CpLSP genes (Fig.1B),shows coexpression during the course of in vitro development (Fig.1C).An additional eight genes were identified that encode proteins having a periodic cysteine structure similar to the Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein;these eight genes are similarly expressed during the onset of oocyst formation and likely participate in the formation of the coccidian rigid oocyst wall in both Cryptospo-ridium and Toxoplasma (21).Whereas the extracellular proteins described above are of apparent apicomplexan or lineage-specific in-vention,Cryptosporidium possesses many genesencodingsecretedproteinshavinglineage-specific multidomain architectures composed of animal-and bacterial-like extracellular adhe-sive domains (fig.S1).Lineage-specific expansions were ob-served for several proteases (table S2),in-cluding an aspartyl protease (six genes),a subtilisin-like protease,a cryptopain-like cys-teine protease (five genes),and a Plas-modium falcilysin-like (insulin degrading enzyme –like)protease (19genes).Nine of the Cryptosporidium falcilysin genes lack the Zn-chelating “HXXEH ”active site motif and are likely to be catalytically inactive copies that may have been reused for specific protein-protein interactions on the cell sur-face.In contrast to the Plasmodium falcilysin,the Cryptosporidium genes possess signal peptide sequences and are likely trafficked to a secretory pathway.The expansion of this family suggests either that the proteins have distinct cleavage specificities or that their diversity may be related to evasion of a host immune response.Completion of the C.parvum genome se-quence has highlighted the lack of conven-tional drug targets currently pursued for the control and treatment of other parasitic protists.On the basis of molecular and bio-chemical studies and drug screening of other apicomplexans,several putative Cryptospo-ridium metabolic pathways or enzymes have been erroneously proposed to be potential drug targets (22),including the apicoplast and its associated metabolic pathways,the shikimate pathway,the mannitol cycle,the electron transport chain,and HXGPRT.Nonetheless,complete genome sequence analysis identifies a number of classic and novel molecular candidates for drug explora-tion,including numerous plant-like and bacterial-like enzymes (tables S3and S4).Although the C.parvum genome lacks HXGPRT,a potent drug target in other api-complexans,it has only the single pathway dependent on IMPDH to convert AMP to GMP.The bacterial-type IMPDH may be a promising target because it differs substan-tially from that of eukaryotic enzymes (15).Because of the lack of de novo biosynthetic capacity for purines,pyrimidines,and amino acids,C.parvum relies solely on scavenge from the host via a series of transporters,which may be exploited for chemotherapy.C.parvum possesses a bacterial-type thymidine kinase,and the role of this enzyme in pyrim-idine metabolism and its drug target candida-cy should be pursued.The presence of an alternative oxidase,likely targeted to the remnant mitochondrion,gives promise to the study of salicylhydroxamic acid (SHAM),as-cofuranone,and their analogs as inhibitors of energy metabolism in the parasite (23).Cryptosporidium possesses at least 15“plant-like ”enzymes that are either absent in or highly divergent from those typically found in mammals (table S3).Within the glycolytic pathway,the plant-like PPi-PFK has been shown to be a potential target in other parasites including T.gondii ,and PEPCL and PGI ap-pear to be plant-type enzymes in C.parvum .Another example is a trehalose-6-phosphate synthase/phosphatase catalyzing trehalose bio-synthesis from glucose-6-phosphate and uridine diphosphate –glucose.Trehalose may serve as a sugar storage source or may function as an antidesiccant,antioxidant,or protein stability agent in oocysts,playing a role similar to that of mannitol in Eimeria oocysts (24).Orthologs of putative Eimeria mannitol synthesis enzymes were not found.However,two oxidoreductases (table S2)were identified in C.parvum ,one of which belongs to the same families as the plant mannose dehydrogenases (25)and the other to the plant cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases.In principle,these enzymes could synthesize protective polyol compounds,and the former enzyme could use host-derived mannose to syn-thesize mannitol.References and Notes1.D.G.Korich et al .,Appl.Environ.Microbiol.56,1423(1990).2.See supportingdata on Science Online.3.M.J.Gardner et al .,Nature 419,498(2002).4.A.T.Bankier et al .,Genome Res.13,1787(2003).5.J.C.Wootton,Comput.Chem.18,269(1994).Fig.1.(A )Schematic showing the chromosomal locations of clusters of potentially secreted proteins.Numbers of adjacent genes are indicated in paren-theses.Arrows indicate direc-tion of clusters containinguni-directional genes (encoded on the same strand);squares indi-cate clusters containingg enes encoded on both strands.Non-paralogous genes are indicated by solid gray squares or direc-tional triangles;SKSR (green triangles),FGLN (red trian-gles),and MEDLE (blue trian-gles)indicate three C.parvum –specific families of paralogous genes predominantly located at telomeres.Insl (yellow tri-angles)indicates an insulinase/falcilysin-like paralogous gene family.Cp LSP (white square)indicates the location of a clus-ter of adjacent large secreted proteins (table S2)that are cotranscriptionally regulated.Identified anchored telomeric repeat sequences are indicated by circles.(B )Schematic show-inga select locus containinga cluster of coexpressed large secreted proteins (Cp LSP).Genes and intergenic regions (regions between identified genes)are drawn to scale at the nucleotide level.The length of the intergenic re-gions is indicated above or be-low the locus.(C )Relative ex-pression levels of CpLSP (red lines)and,as a control,C.parvum Hedgehog-type HINT domain gene (blue line)duringin vitro development,as determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR usingg ene-specific primers correspondingto the seven adjacent g enes within the CpLSP locus as shown in (B).Expression levels from three independent time-course experiments are represented as the ratio of the expression of each gene to that of C.parvum 18S rRNA present in each of the infected samples (20).R E P O R T S16APRIL 2004VOL 304SCIENCE 444 o n O c t o b e r 7, 2009w w w .s c i e n c e m a g .o r g D o w n l o a d e d f r o m。

本文由老高咯贡献pdf文档可能在WAP端浏览体验不佳。

建议您优先选择TXT,或下载源文件到本机查看。

沈阳工业大学硕士学位论文焊接温度场和应力场的数值模拟姓名:王长利申请学位级别:硕士专业:材料加工工程指导教师:董晓强 20050310沈阳工业大学硕士学位论文摘要焊接是一个涉及电弧物理、传热、冶金和力学的复杂过程。

焊接现象包括焊接时的电磁、传热过程、金属的熔化和凝固、冷却时的相变、焊接应力和变形等。

一旦能够实现对各种焊接现象的计算机模拟,我们就可以通过计算机系统来确定焊接各种结构和材料的最佳设计、最佳工艺方法和焊接参数。

本文在总结前人的工作基础上系统地论述了焊接过程的有限元分析理论,并结合数值计算的方法,对焊接过程产生的温度场、应力场进行了实时动态模拟研究,提出了基于ANSYS软件为平台的焊接温度场和应力场的模拟分析方法,并针对平板堆焊问题进行了实例计算,而且计算结果与传统结果和理论值相吻合。

本文研究的主要内容包括:在计算过程中材料性能随温度变化而变化,属于材料非线性问题;选用高斯函数分布的热源模型,利用函数功能实现热源的移动。

建立了焊接瞬态温度分布数学模型,解决了焊接热源移动的数学模拟问题;通过改变单元属性的方法,解决材料的熔化、凝固问题;对焊缝金属的熔化和凝固进行了有效模拟,解决了进行热应力计算收敛困难或不收敛的问题;对焊接过程产生的应力进行了实时动态模拟,利用本文模拟分析方法,可以对焊接过程的热应力及残余应力进行预测。

本文建立了可行的三维焊接温度场、应力场的动态模拟分析方法,为优化焊接结构工艺和焊接规范参数,提供了理论依据和指导。

关键词:焊接,数值模拟,有限元,温度场,应力场沈阳工业大学硕士学位论文SimulationofweldingtemperaturefieldandstressfieldAbstractWeldingisacomplicatedphysicochemica/processwlfiehinvolvesinelectromagnetism,Mattransferring,metalmeltingandfreezing,phase?changeweldingSOstressanddeformationandon,Inordertogethighquafityweldingstmcttlre,thesefactorshavetobecontrolled.Ifcanweldingprocessbesimulatedwithcomputer,thebestdesign,pmceduremethodandoptimumweldingparametercanbeobtained.BasedOilsummingupother’Sexperience,employingnumericalcalculationmethod,thispaperresearchersystemicallydiscussesthefiniteelementanal删systemoftheweldingprocessbyrealizingthe3Ddynamicsimulationofweldingtemperaturefieldandstressfield,thenusestheresearchresulttosimulatetheweldingprocessofboardsurfacingbyFEMsoftANSYS.Atthetheoryresult.sametime.thecalculationresultaccordswithtraditionalanalysisresultandThemaincontentsofthepaperareasfollowing:thecalculationinweldingprocessisamaterialnonlinearprocedurethatthematerialpropertieschangethefunctionofGaussaswiththetemperature;chooseheatsourcemodel.usethefunctioncommandtoapplyloadofmovingheatS012Ie-2.AmathematicmodeloftransientthermalprocessinweldingisestablishedtosimulatethemovingoftheheatsoBrce.Theeffectsofmeshsize,weldingspeed,weldingcurrentandeffectiveradiuselectricarcontemperaturefielda比discussed.Theproblemofthefusionandsolidificationofmaterialhasbeensolvedbythemethodofchangingtheelementmaterial.Theproblemoftheconvergencedifficultyortheun—convergenceduringthecalculatingofthethermalslTessissolved;throughreal-timedynamicsimulationofthestressproducedinweldingprocess,thethermalstressandresidualSll℃SSinweldingcanbepredictedbyusingthesimulativeanalysismethodinthispaper.Inthispaper,afeasibleslIessdyn黜fiesimulationmethodon3Dweldingtemperaturefield,onfieldhadbeenestablished,whichprovidestheoryfoundationandinstructionoptimizingtheweldingtechnologyandparameters.KEYWORD:Welding,NumericalSimulation,Finiteelement,Temperaturefield,Stressfield.2.独创性说明本人郑重声明:所呈交的论文是我个人在导师指导下进行的研究工作及取得的研究成果。

I SSN1673—9418C O D E N JK Y T A8Jour nal of C o m p ut er S c i e nce a nd Fr ont i er s 1673—9418/2007/01(03)-340-07E-m ai l:f cst@publi c2.bta.net.cahtt p:I lw w w.ceaj.orgT e l:+86—10—51616056基于蕴涵算子族L一人一尺。

的反向三I约束算法水王庆平+,张兴芳W A N G Q i ngpi ng+,Z H A N G X i ngf a ng聊城大学数学科学学院。

山东聊城252059School of M at hem at i cs Sci ence,Li aocheng U ni ver s i t y,L i aocheng,Shandon g252059,C hi na+Cor r esp on di n g aut hor:E-m a i l:w angqi ngpi ng@l cu.edu.c aW A N G Q i ngpi ng,Z H A N G X i ngf ang.Fuzz y r eas o ni ng r e ver s e t r i pl e I con s t r ai nt m et hod unde r f am i l y of i m pl i cat i on oper at or L—A—R p Jour nal of C om p ut er Sci ence a nd Fr ont i er s,2007,1(3):340—346.A bs t r ac t:The t hought s of f uzz y r eas oni ng under f am i l y of i m pl i ca t i on op e ra t o r L-A-R0ar e i nt r oduced,w hi ch can cont ri but e t o r ai se t he cr edi bi l i t y of r ea s oni ng r es ul t.R e ve r se t r i pl e I cons t r a i nt m et h od w i t h r es pe ct t o F M P and F M T m odel s ar e di scusse d.K ey w or ds:f uzzy r eas oni ng;f am i l y of i m pl i ca t i on oper a t or L-A—-R o;r e ve r se t r i pl e I const r a i nt m et hod摘要:提出基于蕴涵算子族L—A坷。

基于ET-WG和ET-OWG算子的二元语义群决策法

基于ET-WG和ET-OWG算子的二元语义群决策法

针对一类属性值和权重值均为语言评价信息的多属性群决策问题,提出了一种群决策分析方法.首先,为了便于语言评价信息的集结运算,提出了一些新的集结算子:扩展的二元语义加权几何(ET-WG)算子和扩展的二元语义有序加权几何(ET-OWG)算子,并分析了这些算子的性质.然后提出了一种基于ET-WG算子和ET-OWG算子的群决策方法,其核心是通过语言信息的集结运算,得到各方案的群体综合评价信息,从而根据二元语义信息的比较原则,得到所有方案的排序结果.最后给出了一个实例分析,说明了本文提出方法的可行性和实用性.

作者:卫贵武黄登仕魏宇 WEI Gui-wu HUANG Deng-shi WEI Yu 作者单位:卫贵武,WEI Gui-wu(重庆文理学院经济与管理学院,重庆,永川,402160;西南交通大学经济管理学院,四川,成都,610031) 黄登仕,魏宇,HUANG Deng-shi,WEI Yu(西南交通大学经济管理学院,四川,成都,610031)

刊名:系统工程学报ISTIC PKU英文刊名:JOURNAL OF SYSTEMS ENGINEERING 年,卷(期):2009 24(6) 分类号:C934 关键词:群决策 ET-WG算子 ET-OWG算子二元语义集结 group decision making ET-WG operator ET-OWG operator 2-tuple linguistic aggregation。

http://www.paper.edu.cn Trapezoid Fuzzy Linguistic WGA Operator Guiwu Wei School of Economics and Management, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, Sichuan 610031, P.R. China Department of Mathematics, North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, Sichuan 637007, P.R. China E-mail:weiguiwu@163.com

Abstract With respect to multiple attribute decision making (MADM) problems, in which attribute values take the form of trapezoid fuzzy linguistic variables, by utilizing some operational laws of trapezoid fuzzy linguistic variables, a new aggregation operator called trapezoid fuzzy linguistic weighted geometric averaging (TFLWGA) operator is proposed. The TFLWGA operator is a more general type of aggregation operator, which is based on the trapezoid fuzzy linguistic weighted geometric averaging (TFLWGA). Moreover, based on TFLWGA operator, a practical method for MAGDM is proposed under fuzzy linguistic environment. The method is straightforward and has no loss of information. Finally, an illustrative example is given to verify the developed approach and to demonstrate its practicality and effectiveness. Keywords: Multiple attribute decision making; trapezoid fuzzy linguistic variables; some operational laws; trapezoid fuzzy linguistic weighted geometric averaging (TFLWGA) operator; similarity measure

1 Introduction In the real world, human beings are constantly making decisions under linguistic environment [1-41]. For example, when evaluating the “comfort” or “design” of a car, linguistic terms like “good”, “fair”, “poor” are usually be used [12]. Up to now, several methods have been proposed for dealing with lin-guistic information. These methods are mainly as follows: (1) The method based on extension principle, which makes operations on the fuzzy numbers that sup-port the semantics of the linguistic terms [19]. (2) The method based on symbols, which makes computations on the indexes of the linguistic terms [20]. (3) The method based on fuzzy linguistic representation model, which represents the linguistic infor-mation with a pair of values called 2-tuple, composed by a linguistic term and a number [21-23]. (4) The method, which computes with words directly [24-41]. In this paper, we shall investigate the multiple attribute decision making (MADM) problems under fuzzy linguistic environment, in which the decision makers are willing or able to provide only their preferences (attribute values) in the form of trapezoid fuzzy linguistic variables because of time pres-sure, lack of knowledge, or data, and their limited expertise related to the problem domain. Up to now, there is no approach developed for dealing with decision making with trapezoid fuzzy linguistic vari-ables based on the weighted geometric averaging (WGA) operator [42]. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to this issue. The aim of this paper is to develop an approach to decision making with trapezoid fuzzy linguistic variables. In order to do so, this paper is set out as follows. Section 2 we introduce the concept of trapezoid fuzzy linguistic variable and some operational laws of trapezoid fuzzy linguistic variables, and then develop a similarity measure between two trapezoid fuzzy linguis-tic variables. Section 3 develops a new aggregation operator such as trapezoid fuzzy linguistic weighted geometric averaging (TFLWGA) operator. Section 4 we develop an approach to ranking the decision alternatives based on the similarity measure and the ideal point of attribute values, which is straightforward and has no loss of information. Section 5 we give an illustrative example to verify the developed approach and to demonstrate its feasibility and practicality. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Trapezoid Fuzzy Linguistic Variables

Let {}1,2,,iSsit==L be a linguistic term set with odd cardinality. Any label, represents a possible value for a linguistic variable, and it should satisfy the following characteristics: ①The set is ordered:,if ; ② There is the reciprocal operator: isijss>ij>()irecssj= such that ;1itj=+−

-1- http://www.paper.edu.cn ③Max operator:()max,ijisss=, if ; ④ Min operator: iss≥j()min,ijisss=, if . For example, S can be defined as [39] iss≤j

,1234567{,,,,,}Ssextremelypoorsverypoorspoorsmediumsgoodsverygoodsextremelygood======== To preserve all the given information, we extend the discrete term set S to a continuous term set {}

1,[1,]aaqSssssaq=≤≤∈, where q is a sufficiently large positive integer. If , then we call the original linguistic term, otherwise, we call the virtual linguistic term. In general, the deci-sion maker uses the original linguistic term to evaluate attributes and alternatives, and the virtual lin-guistic terms can only appear in calculation [39]. asS∈