A Brief History of English Language Teaching in China

- 格式:doc

- 大小:46.50 KB

- 文档页数:5

A Brief History of the English LanguageEnglish is a member of the Indo-European family of languages. This broad family includes most of the European languages spoken today. The Indo-European family includes several major branches:Latin and the modern Romance languages (French etc.);the Germanic languages (English, German, Swedish etc.);the Indo-Iranian languages (Hindi, Urdu, Sanskrit etc.);the Slavic languages (Russian, Polish, Czech etc.);the Baltic languages of Latvian and Lithuanian;the Celtic languages (Welsh, Irish Gaelic etc.); Greek. The influence of the original Indo-European language can be seen today, even though no written record of it exists. The word for father, for example, is vater in German, pater in Latin, and pitr in Sanskrit. These words are all cognates, similar words in different languages that share the same root.Of these branches of the Indo-European family, two are, as far as the study of the development of English is concerned, of paramount importance, the Germanic and the Romance (called that because the Romance languages derive from Latin, the language of ancient Rome). English is a member of the Germanic group of languages. It is believed that this group began as a common language in the Elbe river region about 3,000 years ago. By the second century BC, this Common Germanic language had split into three distinct sub-groups:•East Germanic was spoken by peoples who migrated back tosoutheastern Europe. No East Germanic language is spokentoday, and the only written East Germanic language thatsurvives is Gothic.•North Germanic evolved into the modern Scandinavian languages of Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, and Icelandic (butnot Finnish, which is related to Hungarian and Estonian and isnot an Indo-European language).•West Germanic is the ancestor of modern German, Dutch, Flemish, Frisian, and English.Old English (500-1100 AD)CLICK HERE TO SEE A MAP OF ANGLO-SAXON ENGLANDWest Germanic invaders from Jutland and southern Denmark: the Angles (whose name is the source of the words England and English), Saxons, and Jutes, began to settle in the British Isles in the fifth and sixth centuries AD. They spoke a mutually intelligible language, similar to modern Frisian - the language of the northeastern region of the Netherlands - that is called Old English. Four major dialects of Old English emerged, Northumbrian in the north of England, Mercian in the Midlands, West Saxon in the south and west, and Kentish in the Southeast.These invaders pushed the original, Celtic-speaking inhabitants out of what is now England into Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland, leaving behind a few Celtic words. These Celtic languages survive today in the Gaelic languages of Scotland and Ireland and in Welsh. Cornish, unfortunately, is, in linguistic terms, now a dead language. (The last native Cornish speaker died in 1777) Also influencing English at this time were the Vikings. Norse invasions and settlement, beginning around 850, brought many North Germanic words into the language, particularly in the north of England. Some examples are dream, which had meant 'joy' until the Vikings imparted its current meaning on it from the Scandinavian cognate draumr, and skirt, which continues to live alongside its native English cognate shirt. The majority of words in modern English come from foreign, not Old English roots. In fact, only about one sixth of the known Old English words have descendants surviving today. But this is deceptive; Old English is much more important than these statistics would indicate. About half of the most commonly used words in modern English have Old English roots. Words like be, water, and strong, for example, derive from Old English roots.Old English, whose best known surviving example is the poem Beowulf, lasted until about 1100. Shortly after the most important event in the development and history of the English language, the Norman Conquest.The Norman Conquest and Middle English (1100-1500)William the Conqueror, the Duke of Normandy, invaded and conquered England and the Anglo-Saxons in 1066 AD. The new overlords spoke a dialect of Old French known as Anglo-Norman. TheNormans were also of Germanic stock ("Norman" comes from "Norseman") and Anglo-Norman was a French dialect that had considerable Germanic influences in addition to the basic Latin roots. Prior to the Norman Conquest, Latin had been only a minor influence on the English language, mainly through vestiges of the Roman occupation and from the conversion of Britain to Christianity in the seventh century (ecclesiastical terms such as priest, vicar, and mass came into the language this way), but now there was a wholesale infusion of Romance (Anglo-Norman) words.The influence of the Normans can be illustrated by looking at two words, beef and cow. Beef, commonly eaten by the aristocracy, derives from the Anglo-Norman, while the Anglo-Saxon commoners, who tended the cattle, retained the Germanic cow. Many legal terms, such as indict, jury , and verdict have Anglo-Norman roots because the Normans ran the courts. This split, where words commonly used by the aristocracy have Romantic roots and words frequently used by the Anglo-Saxon commoners have Germanic roots, can be seen in many instances.Sometimes French words replaced Old English words; crime replaced firen and uncle replaced eam. Other times, French and Old English components combined to form a new word, as the French gentle and the Germanic man formed gentleman. Other times, two different words with roughly the same meaning survive into modern English. Thus we have the Germanic doom and the French judgment, or wish and desire.It is useful to compare various versions of a familiar text to see the differences between Old, Middle, and Modern English. Take for instance this Old English (c. 1000) sample:Fæder ure þu þe eart on heofonumsi þin nama gehalgod tobecume þin rice gewurþe þin willa on eorðan swa swa on heofonumurne gedæghwamlican hlaf syle us to dægand forgyf us ure gyltas swa swa we forgyfað urum gyltendumand ne gelæd þu us on costnunge ac alys us of yfele soþlice. Rendered in Middle English (Wyclif, 1384), the same text is recognizable to the modern eye:Oure fadir þat art in heuenes halwid be þi name;þi reume or kyngdom come to be. Be þi wille don in herþe as it is doun in heuene.yeue to us today oure eche dayes bred.And foryeue to us oure dettis þat is oure synnys as we foryeuen to oure dettouris þat is to men þat han synned in us.And lede us not into temptacion but delyuere us from euyl.Finally, in Early Modern English (King James Version, 1611) the same text is completely intelligible:Our father which art in heauen, hallowed be thy name.Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth as it is in heauen. Giue us this day our daily bread.And forgiue us our debts as we forgiue our debters.And lead us not into temptation, but deliuer us from euill. Amen.For a lengthier comparison of the three stages in the development of English click here!In 1204 AD, King John lost the province of Normandy to the King of France. This began a process where the Norman nobles of England became increasingly estranged from their French cousins. England became the chief concern of the nobility, rather than their estates in France, and consequently the nobility adopted a modified English as their native tongue. About 150 years later, the Black Death (1349-50) killed about one third of the English population. And as a result of this the labouring and merchant classes grew in economic and social importance, and along with them English increased in importance compared to Anglo-Norman.This mixture of the two languages came to be known as Middle English. The most famous example of Middle English is Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. Unlike Old English, Middle English can be read, albeit with difficulty, by modern English-speaking people.By 1362, the linguistic division between the nobility and the commoners was largely over. In that year, the Statute of Pleading was adopted, which made English the language of the courts and it began to be used in Parliament.The Middle English period came to a close around 1500 AD with the rise of Modern English.Early Modern English (1500-1800)The next wave of innovation in English came with the Renaissance. The revival of classical scholarship brought many classical Latin and Greek words into the Language. These borrowings were deliberate and many bemoaned the adoption of these "inkhorn" terms, but many survive to this day. Shakespeare's character Holofernes in Loves Labor Lost is a satire of an overenthusiastic schoolmaster who is too fond of Latinisms.Many students having difficulty understanding Shakespeare would be surprised to learn that he wrote in modern English. But, as can be seen in the earlier example of the Lord's Prayer, Elizabethan English has much more in common with our language today than it does with the language of Chaucer. Many familiar words and phrases were coined or first recorded by Shakespeare, some 2,000 words and countless idioms are his. Newcomers to Shakespeare are often shocked at the number of cliches contained in his plays, until they realize that he coined them and they became cliches afterwards. "One fell swoop," "vanish into thin air," and "flesh and blood" are all Shakespeare's. Words he bequeathed to the language include "critical," "leapfrog," "majestic," "dwindle," and "pedant."Two other major factors influenced the language and served to separate Middle and Modern English. The first was the Great Vowel Shift. This was a change in pronunciation that began around 1400. While modern English speakers can read Chaucer with some difficulty, Chaucer's pronunciation would have been completely unintelligible to the modern ear. Shakespeare, on the other hand, would be accented, but understandable. Vowel sounds began to be made further to the front of the mouth and the letter "e" at the end of words became silent. Chaucer's Lyf (pronounced "leef") became the modern life. In Middle English name was pronounced "nam-a," five was pronounced "feef," and down was pronounced "doon." In linguistic terms, the shift was rather sudden, the major changes occurring within a century. The shift is still not over, however, vowel sounds are still shortening although the change has become considerably more gradual.The last major factor in the development of Modern English was the advent of the printing press. William Caxton brought the printing press to England in 1476. Books became cheaper and as a result, literacy became more common. Publishing for the masses became a profitable enterprise, and works in English, as opposed to Latin, became more common. Finally, the printing press broughtstandardization to English. The dialect of London, where most publishing houses were located, became the standard. Spelling and grammar became fixed, and the first English dictionary was published in 1604.Late-Modern English (1800-Present)The principal distinction between early- and late-modern English is vocabulary. Pronunciation, grammar, and spelling are largely the same, but Late-Modern English has many more words. These words are the result of two historical factors. The first is the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the technological society. This necessitated new words for things and ideas that had not previously existed. The second was the British Empire. At its height, Britain ruled one quarter of the earth's surface, and English adopted many foreign words and made them its own.The industrial and scientific revolutions created a need for neologisms to describe the new creations and discoveries. For this, English relied heavily on Latin and Greek. Words like oxygen, protein, nuclear, and vaccine did not exist in the classical languages, but they were created from Latin and Greek roots. Such neologisms were not exclusively created from classical roots though, English roots were used for such terms as horsepower, airplane, and typewriter.This burst of neologisms continues today, perhaps most visible in the field of electronics and computers. Byte, cyber-, bios, hard-drive, and microchip are good examples.Also, the rise of the British Empire and the growth of global trade served not only to introduce English to the world, but to introduce words into English. Hindi, and the other languages of the Indian subcontinent, provided many words, such as pundit, shampoo, pajamas, and juggernaut. Virtually every language on Earth has contributed to the development of English, from Finnish (sauna) and Japanese (tycoon) to the vast contributions of French and Latin.The British Empire was a maritime empire, and the influence of nautical terms on the English language has been great. Phrases like three sheets to the wind have their origins onboard ships.Finally, the military influence on the language during the latter half of twentieth century was significant. Before the Great War, militaryservice for English-speaking persons was rare; both Britain and the United States maintained small, volunteer militaries. Military slang existed, but with the exception of nautical terms, rarely influenced standard English. During the mid-20th century, however, a large number of British and American men served in the military. And consequently military slang entered the language like never before. Blockbuster, nose dive, camouflage, radar, roadblock, spearhead, and landing strip are all military terms that made their way into standard English.American English and other varietiesAlso significant beginning around 1600 AD was the English colonization of North America and the subsequent creation of American English. Some pronunciations and usages "froze" when they reached the American shore. In certain respects, some varieties of American English are closer to the English of Shakespeare than modern Standard English ('English English' or as it is often incorrectly termed 'British English') is. Some "Americanisms" are actually originally English English expressions that were preserved in the colonies while lost at home (e.g., fall as a synonym for autumn, trash for rubbish, and loan as a verb instead of lend).The American dialect also served as the route of introduction for many native American words into the English language. Most often, these were place names like Mississippi, Roanoke, and Iowa.Indian-sounding names like Idaho were sometimes created that had no native-American roots. But, names for other things besides places were also common. Raccoon, tomato, canoe, barbecue, savanna, and hickory have native American roots, although in many cases the original Indian words were mangled almost beyond recognition. Spanish has also been great influence on American English. M ustang, canyon, ranch, stampede, and vigilante are all examples of Spanish words that made their way into English through the settlement of the American West.A lesser number of words have entered American English from French and West African languages.Likewise dialects of English have developed in many of the former colonies of the British Empire. There are distinct forms of the Englishlanguage spoken in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India and many other parts of the world.Global EnglishEnglish has now inarguably achieved global status. Whenever we turn on the news to find out what's happening in East Asia, or the Balkans, or Africa, or South America, or practically anywhere, local people are being interviewed and telling us about it in English. To illustrate the point when Pope John Paul II arrived in the Middle East recently to retrace Christ's footsteps and addressed Christians, Muslims and Jews, the pontiff spoke not Latin, not Arabic, not Italian, not Hebrew, not his native Polish. He spoke in English.Indeed, if one looks at some of the facts about the amazing reachof the English language many would be surprised. English is used in over 90 countries as an official or semi-official language. English is the working language of the Asian trade group ASEAN. It is the de facto working language of 98 percent of international research physicists and research chemists. It is the official language of the European Central Bank, even though the bank is in Frankfurt and neither Britain nor any other predominantly English-speaking country is a member of the European Monetary Union. It is the language in which Indian parents and black parents in South Africa overwhelmingly wish their children to be educated. It is believed that over one billion people worldwide are currently learning English.One of the more remarkable aspects of the spread of English around the world has been the extent to which Europeans are adopting it as their internal lingua franca. English is spreading from northern Europe to the south and is now firmly entrenched as a second language in countries such as Sweden, Norway, Netherlands and Denmark. Although not an official language in any of these countries if one visits any of them it would seem that almost everyone there can communicate with ease in English. Indeed, if one switches on a television in Holland one would find as many channels in English (albeit subtitled), as there are in Dutch.As part of the European Year of Languages, a special survey of European attitudes towards and their use of languages has just published. The report confirms that at the beginning of 2001 English is the most widely known foreign or second language, with 43% ofEuropeans claiming they speak it in addition to their mother tongue. Sweden now heads the league table of English speakers, with over 89% of the population saying they can speak the language well or very well. However, in contrast, only 36% of Spanish and Portuguese nationals speak English. What's more, English is the language rated as most useful to know, with over 77% of Europeans who do not speak English as their first language, rating it as useful. French rated 38%, German 23% and Spanish 6%English has without a doubt become the global language.A Chronology of the English Language449Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain begins450-480Earliest Old English inscriptions date from this period597St. Augustine arrives in Britain. Beginning of Christian conversion731The Venerable Bede publishes The Ecclesiastical History of the English People in Latin792Viking raids and settlements begin871Alfred becomes king of Wessex. He has Latin works translated into English and begins practice of English prose. TheAnglo-Saxon Chronicle is begun911Charles II of France grants Normandy to the Viking chief Hrolf the Ganger. The beginning of Norman Frenchc. 1000The oldest surviving manuscript of Beowulf dates from this period1066The Norman conquestc. 1150The oldest surviving manuscripts of Middle English date from this period1171Henry II conquers Ireland1204King John loses the province of Normandy to France1348English replaces Latin as the medium of instruction in schools, other than Oxford and Cambridge which retain Latin1362The Statute of Pleading replaces French with English as the language of law. Records continue to be kept in Latin. English is used in Parliament for the first time1384Wyclif publishes his English translation of the Bible c. 1388Chaucer begins The Canterbury Tales1476William Caxton establishes the first English printing press 1492Columbus discovers the New World1549First version of The Book of Common Prayer1604Robert Cawdrey publishes the first English dictionary, Table Alphabeticall1607Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in the New World, established1611The Authorized, or King James Version, of the Bible is published1702Publication of the first daily, English-language newspaper, The Daily Courant, in London1755Samuel Johnson publishes his dictionary 1770Cook discovers Australia1928The Oxford English Dictionary is published。

A-Brief-History-of-EnglishA Brief History of EnglishN o understanding of the English language can be very satisfactory without a notion of the history of the language. But we shall have to make do with just a notion. The history of English is long and complicated, and we can only hit the higl1 spots.不了解英语的历史很难真正掌握这门语言,然而对此我们只能做到略有所知。

因为英语的历史既漫长又复杂,我们只能抓住其发展过程中的几个关键时期。

At the time of the Ro1nan Empire, the speakers of what was to become English were scattered along the northern coast of Europe. They spoke a dialect of Low German. More exactly, they spoke several different dialects, since they were several different tribes. The names given to the tribes who got to England are Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, who are referred to collectively as Anglo-Saxons4.在罗马帝国时期,散居在欧洲北部沿海的居民说一种西部德语的方言,这就是英语的前身。

更确切地说,由于隶属于不同的部落,他们说的是几种不同的方言。

A Brief History of the English LanguageEnglish is a member of the Indo-European family of languages. This broad family includes most of the European languages spoken today. The Indo-European family includes several major branches:Latin and the modern Romance languages (French etc.);the Germanic languages (English, German, Swedish etc.);the Indo-Iranian languages (Hindi, Urdu, Sanskrit etc.);the Slavic languages (Russian, Polish, Czech etc.);the Baltic languages of Latvian and Lithuanian;the Celtic languages (Welsh, Irish Gaelic etc.); Greek. The influence of the original Indo-European language can be seen today, even though no written record of it exists. The word for father, for example, is vater in German, pater in Latin, and pitr in Sanskrit. These words are all cognates, similar words in different languages that share the same root.Of these branches of the Indo-European family, two are, as far as the study of the development of English is concerned, of paramount importance, the Germanic and the Romance (called that because the Romance languages derive from Latin, the language of ancient Rome). English is a member of the Germanic group of languages. It is believed that this group began as a common language in the Elbe river region about 3,000 years ago. By the second century BC, this Common Germanic language had split into three distinct sub-groups:∙East Germanic was spoken by peoples who migrated back tosoutheastern Europe. No East Germanic language is spokentoday, and the only written East Germanic language thatsurvives is Gothic.∙North Germanic evolved into the modern Scandinavian languages of Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, and Icelandic (butnot Finnish, which is related to Hungarian and Estonian and isnot an Indo-European language).∙West Germanic is the ancestor of modern German, Dutch, Flemish, Frisian, and English.Old English (500-1100 AD)CLICK HERE TO SEE A MAP OF ANGLO-SAXON ENGLANDWest Germanic invaders from Jutland and southern Denmark: the Angles (whose name is the source of the words England and English), Saxons, and Jutes, began to settle in the British Isles in the fifth and sixth centuries AD. They spoke a mutually intelligible language, similar to modern Frisian - the language of the northeastern region of the Netherlands - that is called Old English. Four major dialects of Old English emerged, Northumbrian in the north of England, Mercian in the Midlands, West Saxon in the south and west, and Kentish in the Southeast.These invaders pushed the original, Celtic-speaking inhabitants out of what is now England into Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland, leaving behind a few Celtic words. These Celtic languages survive today in the Gaelic languages of Scotland and Ireland and in Welsh. Cornish, unfortunately, is, in linguistic terms, now a dead language. (The last native Cornish speaker died in 1777) Also influencing English at this time were the Vikings. Norse invasions and settlement, beginning around 850, brought many North Germanic words into the language, particularly in the north of England. Some examples are dream, which had meant 'joy' until the Vikings imparted its current meaning on it from the Scandinavian cognate draumr, and skirt, which continues to live alongside its native English cognate shirt. The majority of words in modern English come from foreign, not Old English roots. In fact, only about one sixth of the known Old English words have descendants surviving today. But this is deceptive; Old English is much more important than these statistics would indicate. About half of the most commonly used words in modern English have Old English roots. Words like be, water, and strong, for example, derive from Old English roots.Old English, whose best known surviving example is the poem Beowulf, lasted until about 1100. Shortly after the most important event in the development and history of the English language, the Norman Conquest.The Norman Conquest and Middle English (1100-1500)William the Conqueror, the Duke of Normandy, invaded and conquered England and the Anglo-Saxons in 1066 AD. The new overlords spoke a dialect of Old French known as Anglo-Norman. TheNormans were also of Germanic stock ("Norman" comes from "Norseman") and Anglo-Norman was a French dialect that had considerable Germanic influences in addition to the basic Latin roots. Prior to the Norman Conquest, Latin had been only a minor influence on the English language, mainly through vestiges of the Roman occupation and from the conversion of Britain to Christianity in the seventh century (ecclesiastical terms such as priest, vicar, and mass came into the language this way), but now there was a wholesale infusion of Romance (Anglo-Norman) words.The influence of the Normans can be illustrated by looking at two words, beef and cow. Beef, commonly eaten by the aristocracy, derives from the Anglo-Norman, while the Anglo-Saxon commoners, who tended the cattle, retained the Germanic cow. Many legal terms, such as indict, jury , and verdict have Anglo-Norman roots because the Normans ran the courts. This split, where words commonly used by the aristocracy have Romantic roots and words frequently used by the Anglo-Saxon commoners have Germanic roots, can be seen in many instances.Sometimes French words replaced Old English words; crime replaced firen and uncle replaced eam. Other times, French and Old English components combined to form a new word, as the French gentle and the Germanic man formed gentleman. Other times, two different words with roughly the same meaning survive into modern English. Thus we have the Germanic doom and the French judgment, or wish and desire.It is useful to compare various versions of a familiar text to see the differences between Old, Middle, and Modern English. Take for instance this Old English (c. 1000) sample:Fæder ure þu þe eart on heofonumsi þin nama gehalgod tobecume þin rice gewurþe þin willa on eorðan swa swa on heofonumurne gedæghwamlican hlaf syle us to dægand forgyf us ure gyltas swa swa we forgyfað urum gyltendumand ne gelæd þu us on costnunge ac alys us of yfele soþlice. Rendered in Middle English (Wyclif, 1384), the same text is recognizable to the modern eye:Oure fadir þat art in heuenes halwid be þi name;þi reume or kyngdom come to be. Be þi wille don in herþe as it is doun in heuene.yeue to us today oure eche dayes bred.And foryeue to us oure dettis þat is oure synnys as we foryeuen to oure dettouris þat is to men þat han synned in us.And lede us not into temptacion but delyuere us from euyl.Finally, in Early Modern English (King James Version, 1611) the same text is completely intelligible:Our father which art in heauen, hallowed be thy name.Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth as it is in heauen. Giue us this day our daily bread.And forgiue us our debts as we forgiue our debters.And lead us not into temptation, but deliuer us from euill. Amen.For a lengthier comparison of the three stages in the development of English click here!In 1204 AD, King John lost the province of Normandy to the King of France. This began a process where the Norman nobles of England became increasingly estranged from their French cousins. England became the chief concern of the nobility, rather than their estates in France, and consequently the nobility adopted a modified English as their native tongue. About 150 years later, the Black Death (1349-50) killed about one third of the English population. And as a result of this the labouring and merchant classes grew in economic and social importance, and along with them English increased in importance compared to Anglo-Norman.This mixture of the two languages came to be known as Middle English. The most famous example of Middle English is Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. Unlike Old English, Middle English can be read, albeit with difficulty, by modern English-speaking people.By 1362, the linguistic division between the nobility and the commoners was largely over. In that year, the Statute of Pleading was adopted, which made English the language of the courts and it began to be used in Parliament.The Middle English period came to a close around 1500 AD with the rise of Modern English.Early Modern English (1500-1800)The next wave of innovation in English came with the Renaissance. The revival of classical scholarship brought many classical Latin and Greek words into the Language. These borrowings were deliberate and many bemoaned the adoption of these "inkhorn" terms, but many survive to this day. Shakespeare's character Holofernes in Loves Labor Lost is a satire of an overenthusiastic schoolmaster who is too fond of Latinisms.Many students having difficulty understanding Shakespeare would be surprised to learn that he wrote in modern English. But, as can be seen in the earlier example of the Lord's Prayer, Elizabethan English has much more in common with our language today than it does with the language of Chaucer. Many familiar words and phrases were coined or first recorded by Shakespeare, some 2,000 words and countless idioms are his. Newcomers to Shakespeare are often shocked at the number of cliches contained in his plays, until they realize that he coined them and they became cliches afterwards. "One fell swoop," "vanish into thin air," and "flesh and blood" are all Shakespeare's. Words he bequeathed to the language include "critical," "leapfrog," "majestic," "dwindle," and "pedant."Two other major factors influenced the language and served to separate Middle and Modern English. The first was the Great Vowel Shift. This was a change in pronunciation that began around 1400. While modern English speakers can read Chaucer with some difficulty, Chaucer's pronunciation would have been completely unintelligible to the modern ear. Shakespeare, on the other hand, would be accented, but understandable. Vowel sounds began to be made further to the front of the mouth and the letter "e" at the end of words became silent. Chaucer's Lyf (pronounced "leef") became the modern life. In Middle English name was pronounced "nam-a," five was pronounced "feef," and down was pronounced "doon." In linguistic terms, the shift was rather sudden, the major changes occurring within a century. The shift is still not over, however, vowel sounds are still shortening although the change has become considerably more gradual.The last major factor in the development of Modern English was the advent of the printing press. William Caxton brought the printing press to England in 1476. Books became cheaper and as a result, literacy became more common. Publishing for the masses became a profitable enterprise, and works in English, as opposed to Latin, became more common. Finally, the printing press broughtstandardization to English. The dialect of London, where most publishing houses were located, became the standard. Spelling and grammar became fixed, and the first English dictionary was published in 1604.Late-Modern English (1800-Present)The principal distinction between early- and late-modern English is vocabulary. Pronunciation, grammar, and spelling are largely the same, but Late-Modern English has many more words. These words are the result of two historical factors. The first is the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the technological society. This necessitated new words for things and ideas that had not previously existed. The second was the British Empire. At its height, Britain ruled one quarter of the earth's surface, and English adopted many foreign words and made them its own.The industrial and scientific revolutions created a need for neologisms to describe the new creations and discoveries. For this, English relied heavily on Latin and Greek. Words like oxygen, protein, nuclear, and vaccine did not exist in the classical languages, but they were created from Latin and Greek roots. Such neologisms were not exclusively created from classical roots though, English roots were used for such terms as horsepower, airplane, and typewriter.This burst of neologisms continues today, perhaps most visible in the field of electronics and computers. Byte, cyber-, bios, hard-drive, and microchip are good examples.Also, the rise of the British Empire and the growth of global trade served not only to introduce English to the world, but to introduce words into English. Hindi, and the other languages of the Indian subcontinent, provided many words, such as pundit, shampoo, pajamas, and juggernaut. Virtually every language on Earth has contributed to the development of English, from Finnish (sauna) and Japanese (tycoon) to the vast contributions of French and Latin.The British Empire was a maritime empire, and the influence of nautical terms on the English language has been great. Phrases like three sheets to the wind have their origins onboard ships.Finally, the military influence on the language during the latter half of twentieth century was significant. Before the Great War, militaryservice for English-speaking persons was rare; both Britain and the United States maintained small, volunteer militaries. Military slang existed, but with the exception of nautical terms, rarely influenced standard English. During the mid-20th century, however, a large number of British and American men served in the military. And consequently military slang entered the language like never before. Blockbuster, nose dive, camouflage, radar, roadblock, spearhead, and landing strip are all military terms that made their way into standard English.American English and other varietiesAlso significant beginning around 1600 AD was the English colonization of North America and the subsequent creation of American English. Some pronunciations and usages "froze" when they reached the American shore. In certain respects, some varieties of American English are closer to the English of Shakespeare than modern Standard English ('English English' or as it is often incorrectly termed 'British English') is. Some "Americanisms" are actually originally English English expressions that were preserved in the colonies while lost at home (e.g., fall as a synonym for autumn, trash for rubbish, and loan as a verb instead of lend).The American dialect also served as the route of introduction for many native American words into the English language. Most often, these were place names like Mississippi, Roanoke, and Iowa.Indian-sounding names like Idaho were sometimes created that had no native-American roots. But, names for other things besides places were also common. Raccoon, tomato, canoe, barbecue, savanna, and hickory have native American roots, although in many cases the original Indian words were mangled almost beyond recognition. Spanish has also been great influence on American English. M ustang, canyon, ranch, stampede, and vigilante are all examples of Spanish words that made their way into English through the settlement of the American West.A lesser number of words have entered American English from French and West African languages.Likewise dialects of English have developed in many of the former colonies of the British Empire. There are distinct forms of the Englishlanguage spoken in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India and many other parts of the world.Global EnglishEnglish has now inarguably achieved global status. Whenever we turn on the news to find out what's happening in East Asia, or the Balkans, or Africa, or South America, or practically anywhere, local people are being interviewed and telling us about it in English. To illustrate the point when Pope John Paul II arrived in the Middle East recently to retrace Christ's footsteps and addressed Christians, Muslims and Jews, the pontiff spoke not Latin, not Arabic, not Italian, not Hebrew, not his native Polish. He spoke in English.Indeed, if one looks at some of the facts about the amazing reachof the English language many would be surprised. English is used in over 90 countries as an official or semi-official language. English is the working language of the Asian trade group ASEAN. It is the de facto working language of 98 percent of international research physicists and research chemists. It is the official language of the European Central Bank, even though the bank is in Frankfurt and neither Britain nor any other predominantly English-speaking country is a member of the European Monetary Union. It is the language in which Indian parents and black parents in South Africa overwhelmingly wish their children to be educated. It is believed that over one billion people worldwide are currently learning English.One of the more remarkable aspects of the spread of English around the world has been the extent to which Europeans are adopting it as their internal lingua franca. English is spreading from northern Europe to the south and is now firmly entrenched as a second language in countries such as Sweden, Norway, Netherlands and Denmark. Although not an official language in any of these countries if one visits any of them it would seem that almost everyone there can communicate with ease in English. Indeed, if one switches on a television in Holland one would find as many channels in English (albeit subtitled), as there are in Dutch.As part of the European Year of Languages, a special survey of European attitudes towards and their use of languages has just published. The report confirms that at the beginning of 2001 English is the most widely known foreign or second language, with 43% ofEuropeans claiming they speak it in addition to their mother tongue. Sweden now heads the league table of English speakers, with over 89% of the population saying they can speak the language well or very well. However, in contrast, only 36% of Spanish and Portuguese nationals speak English. What's more, English is the language rated as most useful to know, with over 77% of Europeans who do not speak English as their first language, rating it as useful. French rated 38%, German 23% and Spanish 6%English has without a doubt become the global language.A Chronology of the English Language449Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain begins450-480Earliest Old English inscriptions date from this period597St. Augustine arrives in Britain. Beginning of Christian conversion731The Venerable Bede publishes The Ecclesiastical History of the English People in Latin792Viking raids and settlements begin871Alfred becomes king of Wessex. He has Latin works translated into English and begins practice of English prose. TheAnglo-Saxon Chronicle is begun911Charles II of France grants Normandy to the Viking chief Hrolf the Ganger. The beginning of Norman Frenchc. 1000The oldest surviving manuscript of Beowulf dates from this period1066The Norman conquestc. 1150The oldest surviving manuscripts of Middle English date from this period1171Henry II conquers Ireland1204King John loses the province of Normandy to France1348English replaces Latin as the medium of instruction in schools, other than Oxford and Cambridge which retain Latin1362The Statute of Pleading replaces French with English as the language of law. Records continue to be kept in Latin. English is used in Parliament for the first time1384Wyclif publishes his English translation of the Bible c. 1388Chaucer begins The Canterbury Tales1476William Caxton establishes the first English printing press 1492Columbus discovers the New World1549First version of The Book of Common Prayer1604Robert Cawdrey publishes the first English dictionary, Table Alphabeticall1607Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in the New World, established1611The Authorized, or King James Version, of the Bible is published1702Publication of the first daily, English-language newspaper, The Daily Courant, in London1755Samuel Johnson publishes his dictionary 1770Cook discovers Australia1928The Oxford English Dictionary is published。

A B r i e f H i s t o r yo f E n g l i s hA Brief History of EnglishN o understanding of the English language can be very satisfactory without a notion of the history of the language. But we shall have to make do with just a notion. The history of English is long and complicated, and we can only hit the higl1 spots.不了解英语的历史很难真正掌握这门语言,然而对此我们只能做到略有所知。

因为英语的历史既漫长又复杂,我们只能抓住其发展过程中的几个关键时期。

At the time of the Ro1nan Empire, the speakers of what was to become English were scattered along the northern coast of Europe. They spoke a dialect of Low German. More exactly, they spoke several different dialects, since they were several different tribes. The names given to the tribes who got to England are Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, who are referred to collectively as Anglo-Saxons4.在罗马帝国时期,散居在欧洲北部沿海的居民说一种西部德语的方言,这就是英语的前身。

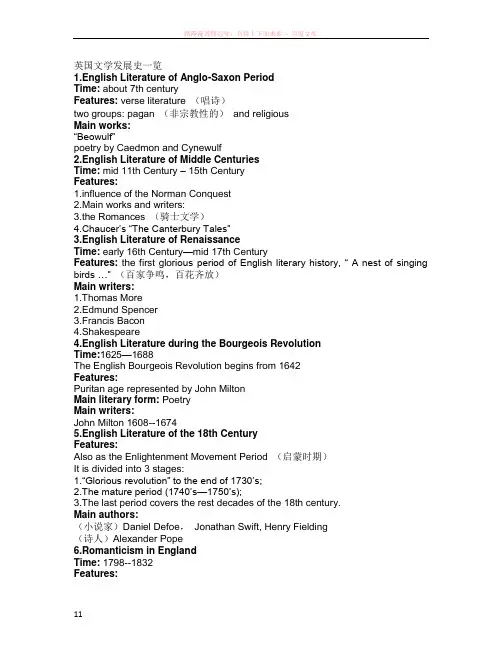

英国文学发展史一览1.English Literature of Anglo-Saxon PeriodTime: about 7th centuryFeatures: verse literature (唱诗)two groups: pagan (非宗教性的)and religiousMain works:“Beowulf”poetry by Caedmon and Cynewulf2.English Literature of Middle CenturiesTime: mid 11th Century – 15th CenturyFeatures:1.influence of the Norman Conquest2.Main works and writers:3.the Romances (骑士文学)4.Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales”3.English Literature of RenaissanceTime: early 16th Century—mid 17th CenturyFeatures: the first glori ous period of English literary history, “ A nest of singing birds …” (百家争鸣,百花齐放)Main writers:1.Thomas More2.Edmund Spencer3.Francis Bacon4.Shakespeare4.English Literature during the Bourgeois RevolutionTime:1625—1688The English Bourgeois Revolution begins from 1642Features:Puritan age represented by John MiltonMain literary form: PoetryMain writers:John Milton 1608--16745.English Literature of the 18th CenturyFeatures:Also as the Enlightenment Movement Period (启蒙时期)It is divided into 3 stages:1.“Glorious revolution” to the end of 1730’s;2.The mature period (1740’s—1750’s);3.The last period covers the rest decades of the 18th century.Main authors:(小说家)Daniel Defoe,Jonathan Swift, Henry Fielding(诗人)Alexander Pope6.Romanticism in EnglandTime: 1798--1832Features:1.是英国文学史上诗歌最为繁盛的时期;2.分为消极和积极两组。

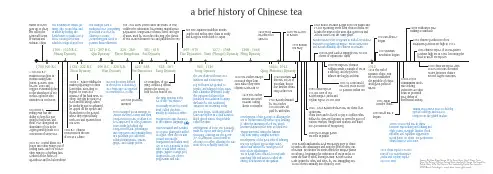

leaves into Shen Nong's vat of boiling water, and tea is born. Shen Nong is a chieftain later credited as the father of agriculture and herbal medicine.dry.It is very popular at thistime to add sweet onions,ginger, jujube, orange peel,dogwood berries, cloves,peppermint and salt.taste of tea to finally come out.to seek trade advantages and stop the flow of silver outof Britain. He obtains tea seeds which the Empire plantsin Calcutta, beginning the cultivation of tea in India. Tostem the flow of silver leaving Britain, British traderstrade opium for silver and silver for tea, smuggling over40,000 chests annually into China by 1838.added and infused for small period oftime (three exhalations).Tea is drunk from a flared rim cup withmatching lids and saucers called thezhong, now known as the gaiwan.1924 China exports 34,000tons of tea, British Empire(India and Ceylon) export240,000 tonsa brief history of Chinese teaSources: Kit Chow & Ione Kramer. All the Tea in China; John C. Evans. Tea inChina, The History of China’s National Drink; Jonathan D. Spence. The Search forModern China; Lu Yu. The Classic of Tea, translated by Francis Ross Carpenter.©2003 Biscuit Technologies - except where source rights prevail.。

AHistoryoftheEnglishLanguage第一篇:A History of the English LanguageA History of the English Language(2011-10-11 23:17:57)转载标签:分类:英语语言概论杂谈A History of the English LanguageThe history of English is a complex and dynamic history.It is often, albeit perhaps too neatly, divided into four periods: Old English, Middle English, Early-Modern English, and Late-Modern English.English is classified genetically as a Low West Germanic language of the Indo-European family of languages.Currently, nearly two billion people around the globe understand it.It is the language of aviation, science, computing, international trade, and diplomacy.It holds a crucial place in the cultural, political, and economic affairs in countries all over the world.From its early beginnings as a series of Germanic dialects, English has been remarkable in both its colonizing power and its ability to adopt and amass vocabulary from all over the world.Yet it was nearly wiped out in its early years(Bragg 2003).Old English(500-1100AD) It is nearly impossible to identify the birth of a language, but in the case of English, it is safe to say that it did not exist before the West Germanic tribes settled Britain.During the fifth and sixth centuries A.D., West Germanic tribes from Jutland and southern Denmark(Norseland)invaded the British Isles.These tribes--which included the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes--spoke a Germanic language now termed Old English, a language which is similar to modern Frisian.Out of these tribes, four major dialects of Old English emerged, Northumbrian in the north of England, Merican in the Midlands, West Saxon in the south and west, and Kentishin the Southeast.These tribes, along with the English language, may well have been wiped out altogether by Viking raiders if not for a Wessex king named Alfred the Great.After defeating the Vikings, who threatened both the English way of life and its language, Alfred the Great encouraged English literacy throughout his kingdom(McCrum, et al 1986).Before the Germanic tribes arrived, the Celts were the original inhabitants of Britain.When the Germanic tribes invaded England, they pushed the Celt-speaking inhabitants out of England into what is now Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland.The Celtic language survives today in the Gaelic languages, and some scholars speculate that the Celtic tongue might have influenced the grammatical development of English, though the influence would have been minimal(Bryson 1990).Around A.D.850, Vikings or Norsemen made a significant impact on the English language by importing many North Germanic words into the language.From the middle of the ninth century, large numbers of Norse invaders settled in Britain, especially in the northern and eastern areas and, in the eleventh century, a Danish(Norse)King, Canute, ruled England.The North Germanic speech of the Norsemen had a fundamental influence on English.They added basic words such as “that,” “they,” and “them,” and also may have been responsible for some of the morphological simplification of Old English, including the loss of grammatical gender and cases(Bragg 2003).The majority of words that constitute Modern English do not come from Old English roots(only about one sixth of known Old English words have descendants surviving today), but almost all of the 100 most commonly used words in modern English do have Old English roots.Words like “water,” “strong,” “the,” “of,” “a,” “he”“no” and many other basic modern English words derive from Old English(Bragg 2003).Still, the English language we know today is a far cry from its Old English ancestor.This is evidenced in the epic poem Beowulf, which is the best known surviving example of Old English(McCrum, et al 1986), but which must be read in translation to modern English by all but those relative few who have studied the work in the original.The Old English period ended with the Norman Conquest, when the language was influenced to an even greater extent by the French-speaking Normans.The Norman Conquest and Middle English(1100-1500)In 1066, William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, invaded and conquered England and the Anglo-Saxons.After the invasion, the Norman kings and the nobility spoke a dialect of Old French known as Anglo-Norman, while English continued to be the language of the common people.This class distinction can still be seen in the English language today in words such as “beef” vs.“cow” and “pork” vs.“pig.” The aristocracy commonly ate beef and pork, which are derivatives of Anglo-Norma, while the Anglo-Saxon commoners, who tended the cattle and hogs, retained the Germanic and ate cow and pig.Many legal terms, such as “indict,” “jury,” and “verdict” also have Anglo-Norman roots because the Normans ruled the courts.It was not uncommon for French words to replace Old English words;for example, “uncle” replaced “eam” and “crime” replaced “firen.” French and English also combined to form new words, such as the French “gentle” and the Germanic “man” forming “gentleman”(Bryson1990).To this day, French-based words hold a more official connotation than do Germanic-based ones.When the English King John lost the province of Normandy to the King of France in 1204, the Normannobles of England began to lose interest in their properties in France and began to adopt a modified English as their native tongue.When the bubonic plague devastated Europe, the dwindling population served to consolidate wealth.The old feudal system crumbled as the new middle class grew in economic and social importance as did their language in relation to Anglo-Norman.The highly inflected system of Old English gave way to, broadly speaking, the same system of English found today which, unlike Old English, does not use distinctive word endings.Unlike Old English, Middle English can be read(albeit with some difficulty)by modern English speakers.By 1362, the linguistic division between the nobility was largely over and the Statue of Pleading was adopted, making English the language of the courts and Parliament.Edward the III became the first king to address Parliament in English in 1362, and the first English government document to be published in English since the Norman Conquest was the Provisions of Oxford.And the most famous literary example of Middle English is Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.The Middle English period came to a close around 1500 with the rise of Modern English(McCrum, et al 1986).Early Modern English(1500-1800)The Renaissance brought with it widespread innovation in the English language.The rediscovery of classical scholarship created an influx of classical Latin and Greek words into the language.While Latin and Greek borrowings diversified the language, some scholars adopted Latin terms awkwardly and excessively, leading to the derogatory term “inkhorn.” An important item for scholars, an inkhorn was simply a horn pot that held ink for quills...but later it became a deprecatory term for pedantic writers who borrowed obscure and opulent termssuch as “revoluting” and “ingent affability”(Bragg 2003).The invention of the printing press also marked the division from Old English to Modern English as books became more widespread and literacy increased.Soon publishing became a marketable occupation and books written in English were often more popular than books in Latin.The printing press also served to standardize English.The written and spoken language of London already influenced the entire country, and with the influence of the printing press, London English soon began to dominate.Indeed, London standard became widely accepted, especially in more formal context.Soon English spelling and grammar were fixed and the first English dictionary was published in 1604(Bryson 1990).In the fifteenth century, the Great Vowel Shift--a series of changes in English pronunciation--further changed the English language.These purely linguistic sound changes moved the spoken language away from the so-called “pure” vowel sounds which still characterize many Continental languages today.Consequently, the phonetic pairings of most long and short vowel sounds were lost, resulting in the oddities of English pronunciation and obscuring the relationship of many English words and their foreign roots.The Great Vowel Shift was rather sudden and the major changes occurred within a century, though the shift is still in process and vowel sounds are still shortening, albeit much more gradually.The causes of the shift are highly debated.Some scholars argue that such a shift occurred due to the “massive intake of Romance loanwords so that English vowels started to sound more like French loanwords.Other scholars suggest it was the loss of inflectional morphology that started the shift”(Bragg 2003).Late-Modern English(1800-Present)The pronunciation, grammar, and spelling of Late-Modern English are essentially the same as Early-Modern English, but Late-Modern English has significantly more words due to several factors.First, discoveries during the scientific and industrial revolutions created a need for a new vocabulary.Scholars drew on Latin and Greek words to creat e new words such as “oxygen,” “nuclear,” and “protein.” Scientific and technological discoveries are still ongoing and neologisms continue to this day, especially in the field of electronics and computers.Just as the printing press revolutionized both spoken and written English, the new language of technology and the Internet places English in a transition period between Modern and Postmodern.Second, the English language has always been a colonizing force.During the medieval and early modern periods, the influence of English quickly spread throughout Britain, and from the beginning of the seventeenth century on, English began to spread throughout the world.Britain’s maritime empire and military influence on language(especially after WWII)has consequently been significant.Britain’s complex colonization, exploration, and overseas trade both imported loanwords from all over the world(such as “shampoo,” “pajamas,” and “yogurt”)and also led to the development of new varieties of English, each with its own nuances of vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation.Significantly, one of England’s colonies, America, created what is known as American English and, in some respects, American English is closer to the English of Shakespeare than the modern Standard British English(or the modern Queen’s English)because many Americanisms are originally British expressions that were preserved in the colonies while lost at home(e.g., “trash” for “rubbish”).Native American andSpanish vocabulary have also been a great influence on American English, importing or adopting such words as “raccoon,” “canoe,” “mustang,” “ranch,” and “vigilante”(Bragg 2003).Global EnglishRecently, English has become a lingua franca, a global language that is regularly used and understood by many countries where English is not the first/native language.In fact, when Pope John Paul II went to the Middle East to retrace Christ’s footsteps and addressed Christians, Muslims, and Jews, the Pope didn’t speak Arabic, Italian, Hebrew, or his native Polish;instead, he spoke in English.In fact, English is used in over 90 countries, and it is the working language of the Asian trade group ASEAN and of 98 percent of international research physicists and chemists.It is also the language of computing, international communication, diplomacy, and navigation.Over one billion people worldwide are currently learning English, making it unarguably a global language.--Posted January 27, 2008ReferencesBragg, Melvyn.2003.The Adventure of English: The Biography of a Language.New York: Arcade Publishing.Bryson, Bill.1990.Mother T ongue: English and How it Got That Way.New York: Perennial.McCrum, Robert, William Cran, and Robert MacNeil.1986.The Story of English.New York: Viking.。

A Brief History of the English Language (英语语言简史)Old English, until 1066Immigrants from Denmark and NW Germany arrived in Britain in the 5th and 6th Centuries A.D., speaking in related dialects belonging to the Germanic and Teutonic branches of theIndo-European language family. Today, English is most closely related to Flemish, Dutch, and German, and is somewhat related to Icelandic, Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish. Icelandic, unchanged for 1,000 years, is very close to Old English. Viking invasions, begun in the 8th Century, gave English a Norwegian and Danish influence which lasted until the Norman Conquest of 1066.Old English WordsThe Angles came from an angle-shaped land area in contemporary Germany. Their name "Angli" from the Latin and commonly-spoken, pre-5th Century German mutated into the Old English "Engle". Later, "Engle" changed to "Angel-cyn" meaning "Angle-race" by A.D. 1000, changing to "Engla-land". Some Old English words which have survived intact include: feet, geese, teeth, men, women, lice, and mice. The modern word "like" can be a noun, adjective, verb, and preposition. In Old English, though, the word was different for each type: gelica as a noun, geic as an adjective, lician as a verb, and gelice as a preposition.Middle English, from 1066 until the 15th CenturyThe Norman Invasion and Conquest of Britain in 1066 and the resulting French Court of William the Conqueror gave the Norwegian-Dutch influenced English a Norman-Parisian-French effect. From 1066 until about 1400, Latin, French, and English were spoken. English almost disappeared entirely into obscurity during this period by the French and Latin dominated court and government. However, in 1362, the Parliament opened with English as the language of choice, and the language was saved from extinction. Present-day English is approximately 50% Germanic (English and Scandinavian) and 50% Romance (French and Latin).Middle English WordsMany new words added to Middle English during this period came from Norman French, Parisian French, and Scandinavian. Norman French words imported into Middle English include: catch, wage, warden, reward, and warrant. Parisian French gave Middle English: chase, guarantee, regard, guardian, and gage. Scandinavian gave to Middle English the important word of law. English nobility had titles which were derived from both Middle English and French. French provided: prince, duke, peer, marquis, viscount, and baron. Middle English independently developed king, queen, lord, lady, and earl. Governmental administrative divisions from French include county, city, village, justice, palace, mansion, and residence. Middle English words include town, home, house, and hall.Early Modern English, from the 15th Century to the 17th CenturyDuring this period, English became more organized and began to resemble the modern version of English. Although the word order and sentence construction was still slightly different, Early Modern English was at least recognizable to the Early Modern English speaker. For example, the Old English "To us pleases sailing" became "We like sailing." Classical elements, from Greek and Latin, profoundly influenced work creation and origin. From Greek, Early Modern English received grammar, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. Also, the "tele-" prefix meaning "far" later used to develop telephone and television was taken.Modern English, from the 17th Century to Modern TimesModern English developed through the efforts of literary and political writings, where literacy was uniformly found. Modern English was heavily influenced by classical usage, the emergence of the university-educated class, Shakespeare, the common language found in the East Midlands section of present-day England, and an organized effort to document and standardize English. Current inflections have remained almost unchanged for 400 years, but sounds of vowels and consonants have changed greatly. As a result, spelling has also changed considerably. For example, from Early English to Modern English, lyf became life, deel became deal, hoom became home, mone became moon, and hous became house.Advantages and Disadvantages of Modern EnglishModern English is composed of several languages, with grammar rules, spelling, and word usage both complimenting and competing for clarity. The disadvantages of Modern English include: an alphabet which is unable to adequately represent all needed sounds without using repeated or combined letters, a limit of 23 letters of the 26 in the alphabet which can effectively express twice the number of sounds actually needed, and a system of spelling which is not based upon pronunciation but foreign language word origin and countless changes throughout history. The advantages of Modern English include: single consonants which are clearly understood and usually represent the same sounds in the same positions, the lack of accent marks found in other languages which permits quicker writing, and the present spelling displays European language origins and connections which allows European language speakers to become immediately aware of thousands of words.Modern English WordsBritish English, known as Standard English or Oxford English, underwent changes as the colonization of North American and the creation of the United States occurred. British English words changed into American English words, such as centre to center, metre to meter, theatre to theater, favour to favor, honour to honor, labour to labor, neighbour to neighbor, cheque to check, connexion to connection, gaol to jail, the storey of a house to story, and tyre for tire. Since 1900, words with consistent spelling but different meanings from British English to American English include: to let for to rent, dual carriageway for divided highway, lift for elevator, amber for yellow, to ring for to telephone, zebra crossing for pedestrian crossing,and pavement for sidewalk.American English, from the 18th Century until Modern TimesUntil the 18th Century, British and American English were remarkably similar with almost no variance. Immigration to America by other English peoples changed the language by 1700. Noah Webster, author of the first authoritative American English dictionary, created many changes. The "-re" endings became "-er" and the "-our" endings became "-or". Spelling by pronunciation and personal choice from Webster were influences.Cough, Sought, Thorough, Thought, and ThroughWhy do these "ough" words have the same central spelling but are so different? This is a characteristic of English, which imported similarly spelled or defined words from different languages over the past 1,000 years.CoughFrom the Middle High German kuchen meaning to breathe heavily, to the French-Old English cohhian, to the Middle English coughen is derived the current word cough.SoughtFrom the Greek hegeisthai meaning to lead, to the Latin sagire meaning to perceive keenly, to the Old High German suohhen meaning to seek, to the French-Old English secan, to the Middle English sekken, is derived the past tense sought of the present tense of the verb to seek. ThoroughFrom the French-Old English thurh and thuruh to the Middle English thorow is derived the current word thorough.ThoughtFrom the Old English thencan, which is related to the French-Old English word hoht, which remained the same in Middle English, is derived the current word thought.ThroughFrom the Sanskrit word tarati, meaning he crossed over, came the Latin word, trans meaning across or beyond. Beginning with Old High German durh, to the French-Old English thurh, to the Middle English thurh, thruh, or through, is derived the current word through.(。

abriefhistoryofenglish读后感(原创版)目录一、引言二、英语的起源和发展三、英语在全球范围内的影响力四、英语学习的重要性五、结论正文【引言】英语作为全球使用最广泛的语言之一,其历史和发展引起了广泛的关注。

近期,我阅读了一篇名为“A Brief History of English”的文章,对英语的起源、发展以及其在全球范围内的影响力有了更深入的了解。

这篇文章让我深感英语学习的重要性,下面我将结合文章内容,谈谈我的读后感。

【英语的起源和发展】英语属于印欧语系日耳曼语族,起源于公元 5 世纪的英格兰。

最初,英语是由盎格鲁 - 撒克逊人使用的一种日耳曼语。

在随后的几个世纪里,英语受到了许多其他语言的影响,如拉丁语、法语和希腊语等,这些语言的词汇和语法规则对英语产生了深远的影响。

16 世纪,英国文艺复兴时期,英语开始逐渐摆脱其他语言的影响,逐渐发展成为现代英语。

【英语在全球范围内的影响力】随着大英帝国的扩张,英语逐渐传播到世界各地。

如今,英语已经成为全球最通用的语言,许多国家和地区都将其作为官方或第二语言。

英语的广泛使用不仅促进了国际间的交流与合作,而且也使各国人民更容易接触到世界先进的科技、文化和思想。

【英语学习的重要性】在当前全球化的背景下,英语学习显得尤为重要。

对于我们国家来说,掌握英语不仅有助于提高国民素质,还可以促进经济、科技、文化等领域的发展。

此外,学好英语还可以为个人拓展更广阔的发展空间,提高国际竞争力。

【结论】总之,阅读“A Brief History of English”这篇文章让我深刻认识到英语在全球范围内的影响力以及学习英语的重要性。

A Brief History of English Language Teaching in ChinaJoseph BoyleAmong the many different aspects of China which have fascinated the West are the sheer size of its population, its remote and mysterious culture, and the intricate difficulty of its language. Equally, the West has always intrigued China, with its technological advancement despite its "barbarity", its cultural diversity within a small space, and the way in which one of its languages - English - has managed to become the lingua franca of the world.China originally felt no need of the West, in fact deliberately avoided all contact, for fear of cultural contamination. The bombing of the Chinese embassy during the Kosovo war was a terrible setback in relations which had been steadily improving. However, despite this, partly because of its desire to join the World Trade Organisation (WTO), China has welcomed and listened politely to leaders of Western countries as they gave their views on democracy and human rights. The language in which President Clinton spoke, during his visit to China, was of course English. President Jiang Zemin made his replies in Chinese. But each was backed up by a team of first-class interpreters, who made smooth communication possible.Formal training in interpretation is comparatively recent in China. It was only in 1978 that the first programme for Translators and Interpreters started at the Beijing Foreign Language Institute. The programme subsequently developed into the prestigious school of translation in the Beijing Foreign Studies University.The learning of English in China, however, has a longer history and now occupies the attention of millions of its people. How many million is hard to say, since much depends on the level of proficiency one takes as the norm (Crystal, 1985). But there are probably in the region of three hundred million actively engaged in the job of learning English.China's reasons for learning English were well summed up twenty years ago by a team from the U.S. International Communication Agency after visiting five cities and many educational institutions in China: "The Chinese view English primarily as a necessary tool which can facilitate access to modem scientific and technological advances, and secondarily as a vehicle to promote commerce and understanding between the People's Republic of China and countries where English is a major language" (Cowan et al., 1979).This basic motivation has not changed, as can be seen from the Report of the English 2000 Conference in Beijing, sponsored jointly by the British Council and the State Education Commis-sion of the People's Republic of China, in which reasons for the learning of English by Chinese were summarised: "They learn English because it is the language of science, specifically perhaps of the majority of research journals. They learn it because it is the neutral language of commerce, the standard currency of international travel and communication. They learn it because you find more software in English than in all other languages put together" (Bowers, 1996:3). The story of English language learning is not uniform throughout China. Maley (1995:7) warns anyone embarking on astudy of contemporary China about the difficulty of "making sensible generalisations about it, since China is not one place geographically, but many". The learning of English in the mountainous provinces near Tibet is very different from the way it is studied in the cities of Nanjing, Shanghai or Beijing. Nevertheless, there are sufficient general characteristics about the history of the learning of English in different parts of China to justify a brief review, if only to remind us of the pendulum swings of China's history this century. Those who wish to find the story more fully told may consult Dzau (1990) and Cortazzi and Jin (1996). Although there is mention of English language teaching (ELT) in China in the mid nineteenth century during the Ching Dynasty, it first figured in the syllabus of schools in 1902 in "His Majesty's Teaching Standards for Primary and Secondary Institutions". In those early days the model for education in China was that of Japan. The method of ELT was traditional, with emphasis on reading and translation. There was much grammar and vocabulary learning, with pronunciation learned by imitation and repetition. This was the norm for about the first twenty years of the century.In 1922 there was a change of direction, with a swing away from the Japanese system of education, and towards more Western models. Schools were obliged to follow the "Outlines for School Syllabuses of the New Teaching System". These put more emphasis on listening and speaking skills. There was more use of the target language and of the new teaching resources offered by the mass media. The best schools tended to be Christian missionary schools, which gave more class-hours to English than other schools.1949 was a crucial date in the history of China - the founding of the People's Republic of China. Education had now to serve the proletarian purpose. All textbooks became vehicles for government propaganda, loaded with messages of service to the people and the motherland. The Ministry of Education issued a new "Scheme for English Instruction in Secondary Schools" in which the goal of English language learning was clearly stated as being to serve the New Republic. All capitalist thinking, especially educational ideas from the United States and Britain, were condemned as unpatriotic. The place of English was taken in school syllabuses by Russian and by 1954 Russian had become the only foreign language taught in Chinese schools.This phase did not last long, however, since China was already trying to extend her markets throughout the world and immediately felt its lack of English. Accordingly, in 1955 the Ministry of Education announced that-English teaching should be restarted in secondary schools. In big cities, like Shanghai, it was also reintroduced at primary level. Initially the textbooks were based on the former Russian models, which, like their Japanese predecessors, were very traditional. Methodology too was backward:the teacher was seen as the provider of knowledge and the students dutifully assimilated the teacher's words of wisdom, working their way ploddingly through the textbook.However, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a minor revolution in education took place in China, as the need to open up to the international scene became more urgent. The importance of English was accepted and a significant step was taken in 1962 when English became part of the entrance examination for colleges and universities. New teaching materials appeared, with listening and speaking again given prominence. The Ministry of Education issued guidelines for textbook writers,recommending that English textbooks should include material on the culture of the English speaking countries. It began to look as though better days had come for ELT in China (Price, 1971).But it was not to be. With distressing inevitability. The Chinese pendulum swung, and the progress made in the early 1960s was swept aside by the Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966 and lasted for ten dreadful years. English was .again banned from schools. Foreign language teachers were branded as spies. Some universities were closed, others were subjected to re-education visits. Dow (1975:254) describes the situation thus: "During the Cultural Revolution, when workers' propaganda teams for the spreading of Mao Tse-Tung's thoughts came to China's colleges, classes were stopped altogether, and the students travelled instead all over the country in order to take part in criticism and debate and to exchange revolutionary experiences".By 1977 the Cultural Revolution had exhausted itself and the country with it. There is an old Yorkshire saying: "There's nowt like religion when it's bent". Those who lived through the Cultural Revolution in China would challenge that saying, maintaining that distorted political ideology can be much worse than bent religion.However, happier times were ahead for China and for ELT in China.In 1978 the Ministry of Education held an important conference on foreign language teaching. English was given prominence again in schools, on a par with Chinese and Maths. By the early 1980s it had been restored as a compulsory subject in the college entrance exam. It has not looked back since then (Kang, 1999) and the fervour for learning English has been fanned by Teach Yourself English programmes on television, watched by hundreds of millions of people.As China opened up more and Chinese scholars were allowed abroad, the need for both social and academic English became apparent. As markets also opened up and more foreigners were allowed into the country to do business, the appetite for Business English among all levels of Chinese people has become insatiable. The Chinese are a diligent and intelligent race and are surely destined to make a significant mark on the history of the twenty-first century.On a personal note, one of my first ELT jobs, in 1979, was teaching a small group of excellent Chinese students on an intensive summer course in England. They were the pick of the Chinese crop - scholars who had suffered under the Cultural Revolution, but who were now being given the chance of graduate studies in British universities. I have never had keener, more hard-working students, and teaching them was one of the most memorable experiences of my life (Boyle, 1980). We have seen, then, in this brief review how English has twice come and gone in China in the course of the twentieth century. To us now it seems unlikely that such swings will happen again and on present evidence the continued popularity of English seems assured. However, history is full of examples of the unpredictable.For one thing, China's own language is liable to become of more global importance in the future. As Graddol (1997:3) advises:"We may find the hegemony of English replaced by an oligarchy of languages, including Spanish and Chinese". Machine translation will also undoubtedly increase in sophistication and perhaps make the learning of English' less essential. English may not be as inevitably the lingua franca of the world as some may like to think.Nevertheless, at this stage in the last few years of the millennium, it does looks as if China will continue to want English, and want it badly. As Maley (1995:47) says: "China is in a phase of industrial, scientific and commercial expansion which will make it the world's largest economy by the early years of the next century. In order to function efficiently in this role, it needs to bring large numbers of its people to high levels of proficiency in the use of English for a wide variety of functions". English looks set to flourish in China - at least for the next ten or twenty years. But anyone who knows anything about the history of China would be slow to predict much beyond that. ReferencesBowers, R. 1996. English in the world. In, English in China. The British Council.Boyle, J. 1980. Teaching English as communication to Mainland Chinese. English Language Teaching Journal 24, 4, 298-301.Cortazzi, M. and Jin, L. 1996. English teaching and learning in China. Language Teaching 29, 61-80.Cowan, J., Light, R., Mathews, B. and Tucker, G. 1979. English teaching in China: a recent survey. TESOL Quarterly 12,4,465-482.Crystal, D. 1985. How many millions? The statistics of English today. English Today 1, 7-9.Dow, M. 1975. The influence of the cultural revolution on the teaching of English in the People's Republic of China. English Language Teaching Journal 29, 3, 253-263.Dzau, Y. 1990. English in China. Hong Kong: API Press. Graddol, D. 1997. The Future of English. The British Council.Kang, Jianxiu. 1999. English everywhere in China. English Today 58, 2, 46-48.Maley, A. 1995. Landmark Review of English in China. The British Council.Price, R. 1971. English teaching in China: changes in teaching methods from 1960-66. English Language Teaching Journal 26, 1,71-83.Joe Boyle teaches at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He can be reached at jpboyle@.hkIATEFL Issues 155, June - July 2000。