会展业会展经济外文文献翻译2012年译文5300多字

- 格式:doc

- 大小:86.50 KB

- 文档页数:14

会展英语课文翻译会展英语课文翻译会展英语的涵盖面较广,涉及众多的不同领域、不同文体,所以会展英语翻译的标准有其特殊性。

鉴于会展英语这种特性,会展英语的翻译标准可以是“信息的灵活对等”,即原文与译文语义信息的对等,原文与译文风格信息的对等,原文与译文文化信息的对等。

下面是小编整理的相关内容,希望对你有帮助。

会展英语的译者除了掌握英语的语言知识和翻译技巧以外,还需领悟国际会展的先进理念,掌握会展策划、管理及操作的实用知识。

(1)The media coverage of an event should be monitored in houseor by using professional media monitors.会展的媒体报道应该受到室内监控,或使用专业的媒体监控器来监控。

很多英语词汇都有三个不同的词义范畴,即结构词义、涉指词义和情景词义,因此,要确定词汇的准确意义须依托语境或上下文。

coverage的基本意思是覆盖范围,但在这句的media-coverage搭配中,依据上下文意义,是指“媒体报道”。

(2)There are restaurants run by some of the top celebrity chefs,right through to cafes and takeaways where you can get something forless than 5 pounds.There is something to suit every taste and budget.这里有大到顶级名厨经营的饭店,小到用不了5英镑便可买到美食的'咖啡馆和外卖餐馆,尽可满足各种口味、各种消费层次的需要。

suit every budget如直译应为“满足各种预算”,在本句中实在是有些牵强,故改译成“满足各种消费层次”,将budget的词典意义转变为符合语境需要的上下文意义,与前面的名词taste形成对称的风格,语意较为准确。

文献出处:Bernini C. Convention industry and destination clusters: Evidence from Italy[J]. Tourism Management, 2013, 30(6): 878-889.原文Convention industry and destinationclusters: Evidence from ItalyAuthor: Cristina BerniniNationality: ItalyAbstract:The study investigates aspects of the convention industry not well explored in the literature. Using a framework of cluster theory, a quantitative method is used to assess the Italian convention industry and its relationships with local infrastructure and tourism product supply. The development of the different phases of the life cycle of convention destinations in Italy is outlined and locational factors which influence them are investigated. Managerial and political strategies which would enhance the competitiveness of the Italian convention industry in the global market are proposed. Furthermore, the study evaluates the use of the cluster theory in investigating the hospitality industry, contributing to the debate on local tourism development.Keywords: Convention Industry, Cluster Theory, Local Development, Clustern Analysis, Quantile Regression.Interest in geographical networks and their role in economic development has grown over the last few years because economies tend to develop through the emergence of territorial agglomeration and company networks (Enright, 2001). An emerging industry centres on some natural resource, market need or local skill. As theindustry develops, new firms, inputs and service enterprises are created. New economic sectors emerge through spill-overs and transferred knowledge and global competitiveness increases. Territorial development and competitiveness are also very important for the tourism industry. Tourism is mainly constituted by SMEs, so functioning within a network may contribute to overcoming production, managerial and commercial difficulties. In order to increase competition and strategic positioning in the worldwide market, tourism destinations should encourage the emergence of tourism networks and the analysis of their structure. Over the past decade, several attempts have been made using the industrial district and cluster theories to investigate tourism networks and their role in local development.Industrial districts (Marshall,1966) are agglomerations of SMEs specialising in different parts of a given production activity. Although industrial district theory analyses conditions for the development of a local vertically-integrated network of firms operating in manufacturing markets, some authors have tried to adapt industrial district theory to the tourism industry (Gets, 1993; Hjalager, 2000; Pearce, 2001; Lazzeretti, 2003). Despite the use of industrial district theory to investigate tourism networks, some doubts are cast on its applicability. Tourism is a sector with a fragmented structure typically based on SMEs but it is particularly characterised by the presence of a large number of participants in the network who are not necessarily involved in the same economic sectors. For this reason Cluster theory is possibly a better analytic model for the investigation of the tourism industry. Cluster theory has its origins in the studies of Porter (1998), who defines cluster as geographic concentrations of interconnected companies, specialised suppliers, service providers and firms in related industries and associated institutions in particular fields that compete but also cooperate. Although Porter’s work is manly focused on the manufacturing industry, it has also been extended and applied to service industries, such as tourism.Some differences emerge between the two theories. Industrial districts are usually local clusters of single-product industries. In contrast, cluster theory refers to concentrations of interrelated but different industries displaying a sharedunderstanding of the competitive business ethic emanating from competitive theory (Jackson & Murphy, 2002). The theory of industrial districts generally refers to an homogeneous product but this is not the case when dealing with tourism destinations. Porter’s cluster theory is better designed to accommodate a heterogeneous product in which the majority of cluster participants serve different industry segments. These points of difference make the analytical framework of industrial districts less applicable to tourism destinations than the cluster approach. In the last ten years several studies have used cluster theory to investigate the role of tourism in influencing local growth. In this field of research the attention is mainly focused on the generalisation of the industrial model as an analytical framework for measuring the success of tourism destinations and on the role of tourism enterprise clusters for their innovation and contribution to community development (Go & Williams, 1993; Michael, 2003; Van Den Berg, Braum, & Van Widen, 2001; Tinsley & Lynch, 2001; Jackson & Murphy, 2002, 2006; Nordin, 2003; Hall, 2004, 2005a, 2005b; Canina, Enz, & Harrison, 2005; Saxena, 2005; Jackson, 2006; Novelli, Smithz, & Spencer, 2006).Otherwise, as stressed by Michael (2003), the cluster theory is valid in macro-regional analysis but presents some drawbacks when applied to small regional environments. The author suggests expanding the concept of cluster to micro-cluster, the so-called diagonal cluster (diagonal integration in Poon, 1994),‘‘labelled in this way to refer to the concentration of complementary (or symbiotic) firms, which each add value to the activities of other firms, even though their products may be quite distinct. In this sense, diagonal clustering brings together firms that supply separate products and services, effectively creating a bundle that will be consumed as though it was one item. For tourism and other service industries, this is often routine-for example, a tourism destination requires firms to supply the activity, provide transport, hospitality, accommodation, etc. The co-location of many complementary providers adds value to the tourism experience, and the converse may also be true, in that the absence of key services restricts t he development of other firms’’ (Michael, 2003).In essence, a firm producing a complementary product or service is not acompetitor, because its activities add more value to the product than the product alone. Thus, cooperation creates alliances and networks, makes better use of skills and resources and encourages innovative business activities which improve local development.The diagonal cluster theoretical framework can also be useful as an interpretive model for the local development of convention destinations. It is a particularly interesting model to apply in the case of Italy because it supports the main guidelines defined by national tourism legislation. The national legislation reform on tourism defines the Tourism Local System (TLS) as ‘‘homogene ous or integrated destinations, also concerning areas which belong to different regions, characterised by an integrated supply of cultural and environmental goods and tourism entertainments, including typical agricultural products and local arts and crafts, or by a wide presence of single or cooperating tourism enterprises’’ (Law nr. 135,2001). As the TLS definition reflects cluster theoretical paradigm in the cooperation, integration and homogeneity principles of the Italian tourism industry, this might be useful in exploring some interesting questions. Do groups of destinations exist with homogeneous tourism characteristics? In TLSs, do local sub-systems specialised in different hosting segments, such as the convention segment (CLS), co-exist? Are these sub-systems integrated with each other? What are the main local features supporting a convention and tourism network? Which destination factors encourage future CLS growth and support emerging clusters? What exists or should exist in a destination in order for convention networks to develop?In answer to these questions, we can use the theoretical model proposed by Porter (1998).In his diamond model of competition, the Author essentially focuses on four components of competitive advantage: (1) demand conditions in terms of the quality, level and nature of tourist interest; (2) local factor conditions, such as a region’s natural resources and location; (3) tourism-related and supporting industries, including accommodation, food and beverage outlets, tourist attractions, the transport sector and various government agencies; (4) government policy supporting communities with information and infrastructure, facilitating inputs such as aneducated workforce, maintaining an appropriate framework for regulation of standards and ensuring macro-economic and political stability. Such a conceptual model could be usefully applied to tourism and convention destinations. The principles of the diamond model can be combined with cluster theory to provide a more comprehensive and balanced approach to regional economic development and the role of tourism within it.However, the conceptualisation of the sectors involved in tourism networks and the nature of their interrelationships in a cluster is not easily standardized. The complexity of the cluster concept suggests that no single definition or methodology is universally correct but varies depending on the economic sector analyzed and on its strategic practices and policies. Considering the main aims of the paper, we have decided to focus on some of the key aspects of tourism and convention destinations: hospitality, accommodation, convention services, educational institutions, transport, population and local resources (Fig. 1). Our original conceptual model is the basis for designing an empirical methodology.Fig 1. The proposed conceptual model of locational competitive advantage in conventionclustersThe empirical analysis is conducted in two steps. Firstly, we suggest using the statistical technique of Cluster Analysis for identifying the municipalities with similar tourism and convention supply and locational resources. This statistical method enables the identification of the different typologies of CLSs and the evaluation of characteristics of CLSs that are in different stages of their convention production life cycle. Secondly, Quantile regression models are introduced to estimate the impact of local characteristics on the convention industry over the life cycle of a CLS. This approach investigates the different influences that local competitive advantage factors have on the conference industry in relation to the phases of a CLS life cycle. Lastly, model estimates have enabled us to propose managerial and political strategies that should be implemented to increase the competitiveness of the Italian convention system in the global market.译文会展产业:来自意大利的案例分析克里斯蒂娜在过去几十年里,人们对地理网络及其在经济发展中所起的作用越来越感兴趣,这是因为经济趋向于通过领土聚集和企业网络的兴起发展起来的(Enright, 2001).一个新兴的产业集中在一些自然资源、市场需求或当地技能上。

关于会展经济学的论文会展经济学是一个快速发展和变化的领域,对于国家和地区的经济发展起着重要作用。

会展经济学研究的是会展产业对经济发展的影响和作用,包括会展活动对城市经济、产业发展、社会影响及环境等方面的影响。

本文将从会展经济学的角度出发,探讨会展产业对经济的影响和促进作用。

首先,会展产业是一个拥有巨大潜力的行业。

会展活动可以为城市带来巨大的经济效益,比如增加就业机会、提高城市知名度、吸引外来游客、促进旅游业发展等。

同时,会展活动也可以给各行业提供一个广泛的交流平台,加强了各领域之间的合作与交流,促进了经济的发展。

其次,会展产业是一个推动相关产业发展的重要引擎。

会展活动的举办可以激发旅游、餐饮、酒店、交通等相关产业的发展,为这些产业提供了巨大的商机。

同时,会展活动也可以促进文化、科技、教育等领域的发展,推动相关产业的进步。

最后,会展产业是一个不断创新和发展的产业。

随着社会发展和科技进步,会展产业也在不断创新,不断提高服务质量和水平,不断拓展市场,为经济发展注入了新的动力。

综上所述,会展经济学是一个重要的研究领域。

会展产业对经济的发展有重要的促进作用,对城市经济、产业发展等方面都有着积极的影响。

因此,我们应该更加重视会展产业的发展,充分发挥其在经济发展中的作用,为经济发展注入新的动力。

同时,会展经济学也需要不断地研究和探索,以适应社会发展的需要。

在全球化、信息化的大背景下,会展经济学需要更加注重跨领域、跨国际的合作,推动会展产业的发展。

同时,会展经济学也需要注重可持续发展,促进会展产业的健康发展,注重环境保护和社会效益,实现经济效益和社会效益的双赢。

在未来,会展经济学还将面临着诸多挑战。

例如,会展产业在发展过程中可能会遇到资源分配不均、环境污染、安全隐患等问题,需要通过政府、企业和社会各界的共同努力来解决。

另外,随着全球化的深入发展,会展经济学也需要更好地融入国际经济体系,加强与国际会展组织的合作,推动全球会展产业的互利共赢发展。

2012年中国会展业发展报告2012年中国会展业发展报告文章来源:商务部服务贸易和商贸服务业司时间:2013-07-12 16:27文章类型:原创内容分类:调研一、会展业发展基本状况2012年,中国会展业保持了持续健康发展的良好势头。

会展业规模不断扩大,经济效益继续攀升,场馆及配套设施建设日趋完善,会展业已从规模化发展逐步转向专业化、品牌化、国际化,并显示出强大的关联效应和经济带动作用,为促进国民经济发展发挥了积极作用。

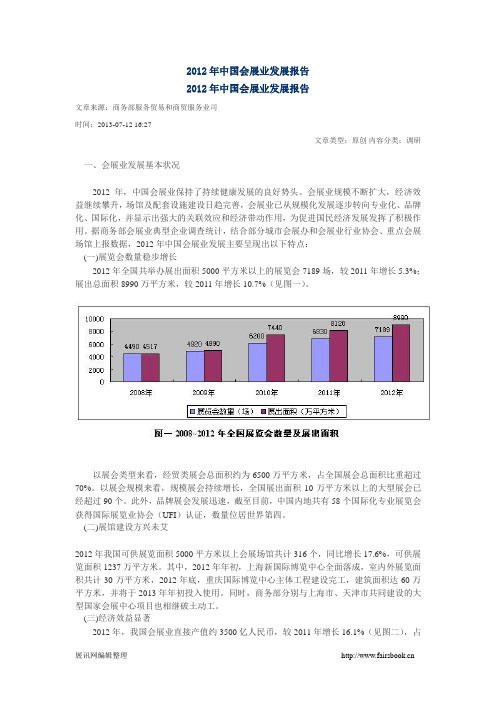

据商务部会展业典型企业调查统计,结合部分城市会展办和会展业行业协会、重点会展场馆上报数据,2012年中国会展业发展主要呈现出以下特点:(一)展览会数量稳步增长2012年全国共举办展出面积5000平方米以上的展览会7189场,较2011年增长5.3%;展出总面积8990万平方米,较2011年增长10.7%(见图一)。

以展会类型来看,经贸类展会总面积约为6500万平方米,占全国展会总面积比重超过70%。

以展会规模来看,规模展会持续增长,全国展出面积10万平方米以上的大型展会已经超过90个。

此外,品牌展会发展迅速,截至目前,中国内地共有58个国际化专业展览会获得国际展览业协会(UFI)认证,数量位居世界第四。

(二)展馆建设方兴未艾2012年我国可供展览面积5000平方米以上会展场馆共计316个,同比增长17.6%,可供展览面积1237万平方米。

其中,2012年年初,上海新国际博览中心全面落成,室内外展览面积共计30万平方米,2012年底,重庆国际博览中心主体工程建设完工,建筑面积达60万平方米,并将于2013年年初投入使用。

同时,商务部分别与上海市、天津市共同建设的大型国家会展中心项目也相继破土动工。

(三)经济效益显著2012年,我国会展业直接产值约3500亿人民币,较2011年增长16.1%(见图二),占全国国内生产总值的0.68%,占全国第三产业产值的1.53%。

(四)社会贡献突出2012年,我国会展业实现社会就业2125万人次,比2011年增长7.3%;拉动相关产业收入3.15万亿人民币,比2011年增长16.7%(见图三)。

关于会展行业外文资料翻译关于会展行业外文资料翻译1. 引言会展行业是指通过展览、会议、庆典等方式,展示产品和服务、促进交流合作的行业。

随着全球化的发展,会展行业在各国间的合作日益频繁,因此,翻译会展行业的外文资料变得越来越重要。

本文将介绍关于会展行业外文资料翻译的一些注意事项和技巧。

2. 了解会展行业术语在进行会展行业外文资料翻译之前,首先需要了解会展行业的相关术语。

会展行业术语通常具有行业特定的含义和用法,因此,准确理解和翻译这些术语对于保持文档的专业性至关重要。

可以通过参考行业内的词汇表、专业术语数据库等资源,确保正确使用和翻译术语。

3. 理解文档背景和目标受众在翻译外文资料时,了解文档的背景和目标受众是非常重要的。

不同类型的会展文档可能有不同的写作风格和用词习惯。

例如,一份宣传材料可能需要使用更为生动活泼的语言,而一份行业报告可能需要更加严谨和专业的表达。

因此,在进行翻译之前,要对文档的背景和目标受众有一个清晰的理解,以确保翻译结果符合要求。

4. 保持语言流畅和准确在进行会展行业外文资料翻译时,要注意保持语言的流畅性和准确性。

流畅的语言可以提高读者的阅读体验,并且更容易传达所要表达的意思。

同时,准确地表达原文的含义也是至关重要的,以确保翻译结果与原文保持一致。

在翻译过程中,可以使用各种工具,如在线词典、翻译记忆库等,来帮助提高翻译的准确性和效率。

5. 注意文化差异在进行会展行业外文资料翻译时,还需要注意文化差异带来的影响。

会展行业是国际性的,涉及到不同国家和地区之间的交流与合作。

因此,在翻译过程中,要注意避免使用可能引起误解或冒犯的词语和表达方式。

对于一些与会展行业紧密相关的文化习惯和象征意义,也可以适当进行解释和说明,以帮助读者更好地理解文档内容。

6. 校对和审校校对和审校是翻译工作中不可或缺的环节。

在完成翻译后,要认真进行自我校对,检查翻译是否准确、流畅,并且没有拼写和语法错误。

此外,可以请专业人士或具备相关行业背景的人进行审校,以确保翻译结果的质量和准确性。

会展经济与管理概述会展经济与管理是一门研究会展产业发展规律以及有效管理会展活动的学科。

随着全球经济的发展,会展已成为推动经济增长的重要手段之一,对于促进国内外经济交流、推动产业升级、提升城市形象等方面发挥着重要作用。

因此,深入研究会展经济与管理具有重要的理论与实践意义。

会展经济对经济发展的影响会展经济对于经济发展具有积极的影响。

首先,会展经济可以促进商务交流与合作。

通过参加会展,企业可以与潜在的合作伙伴进行沟通与交流,寻找到商机,推动合作项目的达成。

其次,会展经济可以促进区域经济发展。

举办会展活动可以吸引大量的外来参会人员,推动酒店、餐饮、交通等相关产业的发展,同时带动当地旅游业的兴盛。

最后,会展经济可以提升城市形象。

成功举办国际性会展活动可以让外界对该城市产生良好的印象,增强城市的知名度与影响力。

会展经济管理的挑战与策略会展经济管理面临着一系列的挑战。

首先,会展经济的发展需要大量的专业人才,但人才的培养与引进仍存在不足。

其次,会展经济管理需要与各个领域的专业知识相结合,因此跨学科研究的需求较大。

此外,会展经济管理还需要应对市场变化的挑战,比如如何应对新兴科技带来的影响等。

为了应对这些挑战,可以采取一系列策略。

首先,加强人才培养与引进。

培养更多的会展专业人才,提高其专业水平与管理能力。

同时,引进优秀的国际人才,引领会展经济发展的前沿。

其次,重视跨学科研究。

会展经济管理需要与市场营销、人力资源管理等多个学科相结合,通过多学科合作,促进会展经济管理的创新与发展。

最后,积极应对市场变化。

在面对新兴科技的冲击时,会展经济管理需要紧跟时代潮流,积极引入科技创新,提升会展活动的效益与体验。

会展经济发展的前景与建议会展经济在未来具有广阔的发展前景。

首先,随着全球经济的进一步发展与国际交往的加深,国际会展活动将取得更大的成功。

其次,新兴科技的快速发展将为会展经济带来新的机遇与挑战,如虚拟现实、人工智能等技术将被广泛应用于会展领域。

会展经济设计文献会展经济设计是指在会展活动中,运用经济学原理和相关理论进行系统性的设计和计划,以实现经济效益最大化的目标。

这种设计不仅关注会展行业本身的发展,还注重会展活动对目标地区经济发展的促进作用。

本文将结合相关文献,探讨会展经济设计的理论依据和实践经验。

首先,市场供求关系是会展经济设计的核心。

会展活动作为一种供给创造性的经济活动,需求则来自于市场对特定行业或领域的需求。

在设计会展活动时,需对市场需求进行深入研究,确定目标受众、展览内容和形式等因素,以吸引更多的参展商和参观者,促进市场的供求平衡。

其次,经济效益是会展经济设计的核心目标。

会展经济一直被视为一种拉动经济增长的重要手段。

通过会展活动,可以推动和促进各行各业的交流与合作,促进产品、技术和服务的转移与创新。

同时,会展活动还能带动旅游、餐饮和购物等相关产业的发展,提高目标地区的经济收入。

因此,在会展经济设计中,应充分考虑经济效益的最大化,以实现会展活动对地方经济的拉动作用。

此外,会展产业链是会展经济设计的理论基础。

会展产业链包括展览组织和策划、展品和展台设计、参展商服务、会议支持等多个环节。

在设计会展经济时,需将这些环节相互连接起来,实现产业链的有效衔接和协同发展。

各个环节的设计应具备创意性和实用性,以提升会展活动的吸引力和竞争力。

在实践中,会展经济设计的重点在于整合各方资源,实现多方共赢。

会展活动需要协调政府、企业、学术机构和社会公众等多个主体的合作,以确保会展活动的顺利进行。

在设计会展经济时,需考虑到各方的利益和诉求,并充分发挥各方的参与和贡献。

综上所述,会展经济设计在实现经济效益最大化方面起着重要的作用。

通过研究市场供求关系、经济效益和会展产业链等理论,可以为会展经济设计提供理论依据。

同时,在实践中,需注重整合各方资源,实现多方共赢的目标。

希望本文能够对会展经济设计的理论与实践有所启发,并为相关领域的研究提供参考。

文献来源: Rogerson C M. Conference and exhibition tourism in the developing world: the South African experience[C]//Urban Forum. Springer-Verlag, 2012, 16(3): 176-195.原文Conference and Exhibition Tourism in the Developing World: The South African ExperienceAuthor: Christian M. RogersonNationality: South AfricaOver the past quarter-century, strong growth was recorded in flows of business tourism, both domestically and internationally, and tourism scholars have accorded the phenomenon increased research significance(Cooper, 1979; Lawson, 1982; Hughes, 1988; Owen, 1992; Davidson, 1993; Bradley et al., 2002; Witt, 2002). Nevertheless, business travel and tourism is one of most diverse and fragmented themes in tourism scholarship. Indeed, the topic of 'business tourism' has been divided into at least fifteen different categories of travel, including individual general business trips, training courses, productd launches, and corporate hospitality and incentive travel (Swarbrooke and Homer,2001). The most important elements of business tourism are acknowledged to be the hosting of meetings, conferences or exhibitions Oppermann and Chon, 1997). Often these are combined with incentive travel into discussions of the category of MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions)tourism.For destination planners, the benefits of attracting business tourism are several. At international level, these include, inter alia, contributions to employment and income, increased foreign exchange earnings, the generation of investment in tourism infrastructure, the facilitation of opportunities foraccess to new tech- nology and ideas, and the establishment of business contacts (Dwyer and Mistilis,1997). At local level, the attractions of business tourism involve the sheer size and expansion of this market, the relatively higher daily expenditures recorded by business travellers as opposed to leisure or VFR tourists, the tendency of business travel to occur outside peak periods for leisure travel, and the multiple local spin-offs for an array of local small businesses, including photographers, printers and florists (Braun1992; Oppermarm, 1997; Wootton and Stevens, 1995; Bradley et aL, 2002; Solberg et aL, 2002; Suh and McAvoy, 2005).On the whole, the market for meetings tourism has grown substantially and seems destined to continue at a rate of growth above that recorded even for most European national economies (Bradley et aL, 2002).Conferences and exhibitions are usually treated together rather than as two separate activities because "there is an increasing convergence between them" (Law,1987: 86). Traditionally, many conferences include exhibitions and exhibitions often give rise to conferences. None the less, as Law (1987: 87) observes the "apogee" of convergence between conferences and exhibitions is the emergence of the multi-purpose 'convention centre' which consists of several large venues which can be used flexibly either for conference or exhibition purposes. Hiller (1995: 375) argues that conferences and exhibitions are a "special kind of tourism" as theoretically they represent the propelling factor for attendance rather than the characteristics of the destination itself. The meeting, convention or exhibition serves as the primary purpose for travel and the focus is a multi-faceted event of a fixed time duration that involves speakers, seminars, workshops, exhibitions, banquets, association meetings and social events. Accordingly, the conference or exhibition event is, therefore, interpreted as markedly different from other forms of business travel in which the primary purpose is individual or small group encounters (Hiller,1995). In practical terms, a commitment to the purpose of the conference or exhibition is not a guarantee of attendance. Issues relating to accessibility, marketing,investment, infrastructure, human resources and service quality are among a range of variables that can be influential (Weber and Ladkin,2003). The markets for conference and exhibition tourism at both international and domestic scale of analysis have been shown to be "extremely competitive" (Dwyer and Mistilis,1997:230) with more and more countries building conference centers "in order to capitalize on this newly emerging tourism sector" (Oppermann,1997:245). Considerable care is taken by meetings or conference organizers in terms of the selection of locations for the hosting of conferences or exhibitions. Accordingly, a critical research focus in business tourism scholarship is understanding the decision-making processes and destination images as held both by association meeting planners and potential attendees (Zelinsky,1994;Oppermann,1996a,1996b; Oppermann and Chon, 1997; Crouch and Ritchie, 1998; Getz et al., 1998; Oppermann,1998; Weber, 2001).The results of such research, including the application of choice modeling exercises, are used to improve the competitive positioning and branding of individual destinations for the attraction of business tourism (Var et al., 1985; Oppermann, 1996a; Crouch and Louviere, 2003; Weber and Ladkin, 2003; Hankinson, 2005). Illustratively, much recent attention has been given to the primacy of Singapore over the competition offered from Hong Kong for international conferences in Southeast Asia and more broadly, the Pacific Rim region.The significance of factors such as capacity of facilities, quality of service, accessibility, as well as cost considerations have been put forward to explain the regional competitive dominance of Singapore and correspondingly, to suggest areas for improvement for enhancing the position of Hong Kong (Go and Govers, 1999; Lew and Chang, 1999; Qu et al., 2000).At national level, the importance of this segment of business tourism is underscored by the fact that certain countries have prepared national policies or strategies that are designed specifically to ensure long-term growth and to maximize the local economic and social impacts of conference and exhibitiontourism. In terms of policy development, one of the most pro-active countries is Australia. During the 1990s the national government encouraged the development of a marketing strategy which is geared, inter alia, to enhance international awareness of the country as a premier conference and exhibition destination; to promote coordinated and cooperative marketing of the industry; to encourage national associations to attract overseas delegates to meetings and exhibitions in Australia, particularly from the Asia-Pacific region; and, to boost the number of delegates attending conferences in Australia at local, national and international level(Dwyer and Mistilis, 1997).For destinations, the economic impacts of capturing the market of business tourism are potentially considerable. Figure 1 shows the economic impacts of business tourism on localities. It discloses that whilst there are both potential positive and negative impacts, "it is generally accepted that the economic benefits of business tourism are positive in most places" (Swarbrooke and Homer,2001: 77). In the USA, the hosting of conventions and meetings is viewed as highly beneficial in that they can complement the seasonal fluctuations experienced in leisure tourism activities (Braun and Rungeling, 1992). Success in business tourism has been shown to bring also an array of non-financial rewards to localities, the most significant associated with image and profile enhancement, the physical upgrading and regeneration of decaying areas, and the generation of civic pride among residents (Law, 1987; Zelinsky, 1994; Bradley et al., 2002). Taken together, given the several potential economic and non-economic impacts of business tourism, it is not surprising that many different kinds of localities have been encouraged to see a slice of this lucrative market by attracting conferences and exhibitions.Fig. 1 The Economic Impacts of Business Tourism at Local Level(Adapted after Swarbrooke, Horner,2002:76)Historically, in Western Europe, resort towns recognized earliest the potential benefits of conference and exhibition tourism and started to develop specialist conference facilities during the inter-war period (1919-39). Indeed, a long-established feature of seaside resorts in the United Kingdom, such as Blackpool, Brighton or Scarborough, is the hosting of the annual conferences of political parties, trade unions and associations in order to attract visitors and extend the length of the tourism season (Douglas, 1979). The market for meeting tourism became more competitive from the early 1980s with the entry of several provincial centers, such as Birmingham, Cardiff, Glasgow, Manchester, Nottingham and Newcastle. In the majority of these centers, multi-purpose facilities were developed (Law, 1987; Bradley et al., 2002). The major exception was Birmingham, which followed the United States model, developing a planned large downtown convention centre to complement its National Exhibition Centre. The meeting tourism market has been aggressively sought after by a large number of former industrial cities in the UK, continental Europe, the USA and Australia, within their strategies of post-industrial regeneration (Law, 1987, 1992, 1993; Bradley et al., 2002). The capital city function also offers opportunities for the development of business tourism as a whole, including for meetings and conferences(Hall, 2002).The factors affecting the competitiveness of individual localities in the USA or Western Europe offer parallels with the Asian experience. The general consensus is that meetings organizers take account of four key attributeswhen selecting meetings venues (Bradley et al., 2002). In order of importance these relate to the quality of meetings facilities, cost, accessibility and image of potential locations (Law, 1993). The relative importance of these four factors will vary, however, according to the nature of particular conferences or exhibitions. Considerable debate surrounds the role of 'image' in meetings tourism with Zelinsky (1994) arguing that in the experience of USA, image is a prime pull-factor. In more recent work, the role of image has been re-evaluated; image is viewed as important for meetings organizers, albeit not as important as other factors (Bradley et a/., 2002). Overall, Law (1987: 93) asserts that for international conferences, meetings organizers "are attracted to places with good air links, a high standard of facilities and an attractive image" whereas the role of image and the attractiveness of locations is of lesser significance for exhibition venues.译文发展中国家的会议和会展业:南非的案例分析克里斯蒂安在过去的25年里,根据相关统计资料,流动的商业旅游消费记录正强劲地增长着,国内外的从事旅游研究的学者们也都给予了此现象以高度的关注,都对此课题进行了相关研究,觉得意义重大(库珀,1979;劳森,1979;休斯,1988;欧文,1992;戴维森1993;布拉德利et al .,2002;威特,2002)。

展会经济发展设计参考文献随着经济全球化的深入,展览会作为一种经济活动方式,在促进经济发展、推动贸易合作以及促进国际交流等方面发挥着越来越重要的作用。

为了更好地发展展会经济,提高展会的效益和影响力,需要进行合理的设计和规划。

本文将参考相关文献,就展会经济发展的设计要点进行探讨。

一、展会经济的概念和特点展会经济是指通过举办展览会来促进经济发展和贸易合作的一种经济模式。

展会经济具有以下特点:首先,展会经济是一种集中展示、交流和合作的平台,能够吸引来自不同地区和行业的参展商和参观者;其次,展会经济具有较高的专业性和针对性,能够满足参展商和参观者的需求;再次,展会经济能够促进产业链的融合和升级,推动经济结构的优化和转型升级。

二、展会经济发展设计的要点1. 定位策略的设计:展会的定位是指明展会的目标、定位和特色,以吸引目标参展商和参观者。

在设计展会的定位策略时,需要充分考虑市场需求、行业特点和竞争对手情况,确定展会的定位,确定展会的主题和特色,以提高展会的吸引力和竞争力。

2. 参展商和参观者的筛选与邀请:展会的成功与否很大程度上取决于参展商和参观者的质量和数量。

因此,在展会经济发展设计中,需要制定参展商和参观者的筛选与邀请策略。

通过对参展商和参观者的需求进行分析,确定合适的参展商和参观者类型,并通过各种渠道进行邀请和推广。

3. 展会场馆和布局设计:展会场馆和布局的设计直接影响展会的效果和体验。

在展会经济发展设计中,需要考虑场馆的大小、设施和交通便利性等因素,确保参展商和参观者的需求得到满足。

同时,还需要合理设计展位的布局和风格,以提高展会的观赏性和参与度。

4. 展会活动和配套服务设计:展会活动和配套服务是展会经济发展的核心内容。

在设计展会活动时,需要充分考虑参展商和参观者的需求和兴趣,确定合适的活动形式和内容,以提高展会的吸引力和参与度。

同时,还需要提供完善的配套服务,如会议场地、餐饮服务、交通接送等,以提升参展商和参观者的体验和满意度。

会展经济与管理毕业论文文献综述摘要:会展经济与管理作为一门新兴的学科,已经在全球范围内得到广泛关注和研究。

本文通过对相关文献的综述,旨在分析会展经济与管理领域的研究现状、趋势和发展方向,并探讨其对经济发展和社会影响的重要性。

1. 研究背景会展经济与管理作为一种重要的经济活动,能够促进产业结构升级和经济增长。

近年来,随着会展行业的快速发展,越来越多的研究者开始关注会展经济与管理领域,并对其进行深入研究。

2. 会展经济与管理研究的方法在会展经济与管理研究中,常用的方法包括实证研究、案例分析、统计分析等。

这些方法能够帮助研究者深入分析会展经济与管理领域的现状和问题,并提出相应的解决方案。

3. 会展经济与管理的发展趋势随着社会经济的不断发展,会展经济与管理也面临着新的机遇和挑战。

未来,会展经济与管理领域的发展趋势可能包括数字化、国际化、创新与可持续发展等方面。

4. 会展经济与管理对经济发展的重要影响会展经济与管理在促进经济发展方面发挥着重要作用。

通过举办展览会、会议等活动,可以促进经济交流与合作,提升城市形象,推动相关产业的发展,为当地经济带来巨大的效益。

5. 会展经济与管理对社会影响的重要性会展经济与管理不仅对经济发展具有重要影响,还对社会产生着广泛的影响。

会展活动能够促进文化交流、人才培养、城市建设等方面的发展,为社会进步和文化繁荣做出贡献。

6. 会展经济与管理研究的局限性和展望尽管会展经济与管理研究取得了一定的成果,但仍存在一些局限性和挑战。

未来的研究可以进一步深入探讨会展经济与管理的内在机制、营销策略、创新模式等方面,为会展行业的持续发展提供理论支持和实践指导。

结论:综上所述,会展经济与管理作为一门新兴的学科,不仅在经济发展方面具有重要作用,还对社会产生着广泛影响。

通过深入研究和探讨会展经济与管理领域的研究现状和发展趋势,可以为学术界和业界提供更多有益的见解和决策参考,推动会展经济与管理领域的进一步发展。

文献出处:Hiller H H. Conventions as mega-events: A new model for convention-host city relationships[J]. Tourism Management, 2012, 16(5):41-53原文Conventions as mega-events A new modelfor convention-host city relationshipsAuthor: Harry H. HillerAbstract: Conventions represent a special form of tourism with a high degree of ecological differentiation from the host society. The encapsulation of conventioneers in highly planned convention activity creates an intrusion-reaction response from the host city - particularly when the convention reaches a size threshold that makes it a mega-event. Conventions can be analytically distinguished from conferences and the characteristics of conventions as mega-events can be identified. In place of the intrusion-reaction model, an interactive-opportunity model is proposed through the use of case studies. A sociological perspective demonstrates how interaction benefits (rather than merely economic benefits) can transform the convention-host city relationship.Conventions represent a special kind of tourism. People leave their home community as individuals or in small groups to join hundreds or thousands of others at a destination for a common purpose. In many ways, the destination is less important than the purpose for the group gathering, and the 'tourism product' is the facilities to host the event at the destination. Theoretically, then, the convention in itself is the attraction rather than the characteristics of the destination as the propelling factor in attendance. All things being equal, the convention could be held in Singapore or Sioux Falls, and delegates would still attend because of their commitment to the purpose of the convention. In practical terms, factors such as distance, cost, accessibility, safety, climate or downturns in the economy may affect the size of the convention or conference, but since conference organizers generally seek to maximize their attendance and/or serve their constituency, considerable care is taken in site selection. One study found that accessibility to the destination site was more important than the attractiveness of the site for convention tourists. (See also Fortin and Ritchie.)Conferences, congresses and conventions involve a form of travel in which the meeting serves as the primary purpose for the travel. These meetings are distinct from corporate travel in that the primary purpose is not individual or small-group encounters, but a multifaceted event of a fixed time collectivity involving speakers, seminars, and workshops, exhibitions, banquets, social events and association meetings. While corporate meetings are more likely to be more frequent and smaller, association meetings of trade, union, fraternal, educational, service and charitable groups are larger and follow a more regular cycle (E.g. annual meetings). Expenditures for conferences, congresses and conventions also tend to be larger because of the package format of events.Convention attendance as voluntaristic behaviorA central characteristic of an association meeting is that attendance is voluntary. Attendance is dependent on the level of interest in the purpose of the meeting and the priority which potential delegates give to the event to clear their calendars to attend. Persons may become regular attendees because of their commitment to the sponsoring organization (e.g. an organization of worker specialists) or their interest in the theme of the meeting. Whether the form of the meeting is work related or a leisure activity, the farther the meeting is from home, the greater the likelihood that the conference organizers will package the event around the destination to enhance attendance. Packaging may involve everything from an official airline, car rental companies and select hotels, to theme events based on the special characteristics of the host region, and pre- and post-conference tours. In other words, as a vehicle to optimize attendance, the destination may be marketed to potential delegates in order to enhance the success of the meetings. Note that in contrast with usual conceptions of a tourist, the destination is an 'add-on' to the essential purpose of he meeting itself.The voluntaristic nature of meeting-based tourism means that attendance may vary and that organizers may explicitly develop a marketing strategy to encourage positive responses by individuals. However, once the individual has decided to attend the meeting, she/he becomes part of a social group at the destination that is distinct and separate from the host community. One of the primary functions of the meeting organizer is to organize social events that will foster interaction among delegates. These may vary from large assemblies and thematic workshops to receptions and excursions. In sum, the conference or convention becomes a self-contained entity at which a full program of activity keeps attendees busy from morning to night frequently including even meals and coffee breaks.The differentiation of touristsCohen has noted that mass tourism means that tourists are ecologically differentiated from theirhost society. They are surrounded by, but not integrated into their destination community because their dealings are almost exclusively with tourism agents such as taxi drivers, desk clerks or tour guides. A package tour accentuates even further the degree of differentiation, but the end result is the creation of an illusion that the tourist has 'been there'. The tourist may have 'seen the sights' but there certainly has been no meaningful interaction with local residents.The meeting-oriented tourist is another variant of packaged tourism. There is a full schedule of activity that keeps the visitor busy and socially and psychologically differentiated from the host community. It is not unusual for delegates to move from the airport to hotel to meeting place and back to the airport with only brief forays into other selected locations such as a store or a restaurant. While there may be an economic impact to such tourism, the visitor has hardly experienced the local culture. In that sense, the location of the meeting is indeed of marginal importance and the host community is only understood in terms of its meeting-related facilities and service personnel.The impact of tourism on the host communityThe relationship between tourist and host community is one of considerable debate. While the economic benefits of tourism are substantial, it is also recognized that there may be both economic and social costs. Inflation, demonstration effects, traffic congestion and increased crime are some of the potential negative impacts. Research has demonstrated that not all local residents are affected in the same way by tourism and that there may indeed be a wide range of responses to tourism. AP and Crompton have suggested that there are four basic strategies by which residents respond to tourism: embracement, tolerance, adjustment and withdrawal. Davis et al identified five clusters of resident responses: haters, lovers, cautious romantics, 'in-between-ears’ and 'love-'am for a reason'. Pizza, not surprisingly, found that the more a community resident was economically dependent on tourism, the more favorable they were towards tourism. It could also be assumed that the more differentiated tourism is from the host community in all respects, the less likely it is that local residents will perceive harmful effects.One of the key factors in resident/visitor relationships may be volume. Pizza suggests that heavy tourist concentrations in a destination may be more likely to affect local residents. Dopey points out that, as volume increases, host communities may reach a saturation point where irritation increases. His 'Irises' along the saturation continuum moves from euphoria to apathy to annoyance to antagonism. On the other hand, the work of Butler implies that factors such as cultural distance, economic disparities, or the spatial distribution of tourist activities in the host community may bemore important than sheer volume, and that these factors marc again provoke a considerable range of responses.Tourism is an industry and it is not surprising that there would be as wide a range of responses to it as there would be to any industry. It is for that reason that concepts like 'sustainable tourism', 'resident responsive tourism' and 'community based tourism' have become important. Most of the literature in this approach focuses on the local community having input into the nature, scope and pace of tourist development. The emphasis also seems to be on tourist delivery systems such as facilities, attractions and lab-our needs. There is little emphasis, however, on the visitor/resident relationship once tourism is well established and part of the fabric of the community.When the cultural gap between the visitor and the local resident is significant, there is a greater sensitivity to the cultural impact of tourism. Tourism between developed and less developed societies has brought into sharper relief the negative effects of tourism (compare Witt and Smith). When tourism occurs within developed societies and particularly urban-to-urban tourism, the cultural conflict is minimal and the delegate/resident relationship may even be forgotten. Mega cities such as New York, Chicago and London are capable of handling large numbers of tourists without much observable consequence. However, in smaller cities, large- scale tourism can have a very different impact on local residents and provides some unique opportunities which are usually overlooked. The primary purpose of this article is to show how mega event conventions can provide the occasion to transform the visitor/resident relationship in medium-sized cities.The convention as a mega eventFor the sake of this analysis, it is important to distinguish conceptually between a conference and a convention in relation to mega-events. Conferences, seminars and workshops drawing people from some distance are an ongoing recurring activity in just about every community regardless of size. There are some locations that draw more such events and perhaps larger ones than others but, in general, conferences are everywhere. What is more unique, however, is the large conference which I will call a convention. Setting a size threshold may be totally arbitrary, but the emphasis here is an increase of scale that requires the following:• The use of numero us lodging establishments rather than just one or two;• A major planning organization with considerable lead time for planning;• A complex program including spousal programs, pre- and post-programs;• The need for many meeting rooms including at least one large assembly hall;• The tendency towards national/international representations.When all of these conditions apply, the impact of the event becomes much more significant for the host community. Meetings drawing 1000 or more delegates, then, could serve as an arbitrary baseline for being a convention.When conventions become very large, they can take on the character of a mega-event for a host city of medium size (approximately 500 000 to 1 million residents).• When mega-cities such as Toronto or New York host a large convention for which they are routinely prepared, the convention does not become a mega-event. However, when medium-size cities that do not routinely attract larger gatherings on a regular basis host a substantial convention, it can become a mega-event.• When there is a 'bid' process and a sense of being 'selected' as the site of the event, and a facilities and logistics assessment to ascertain carefully the suitability of the site, the host community develops a sense of the excitement and expectancy of the challenge as a mega-event.• When the convention has national/international status with considerable prestige, the host community anticipates it as a mega-event.• When the impact of the convention is in some sense dispersed t hroughout the city and not just restricted to hotels and restaurants surrounding the convention center, the convention becomes a mega-event.In sum, conventions of over 5000 people with the above characteristics in mid-size cities are most likely to be viewed as mega-events.While delegates may have the sense of coming to a big convention, it is primarily the host community of medium size that transforms the convention into a mega-event.• The local media carry the details and progress of the bid process which stimulates public interest and conveys a sense of a positive outcome as a 'prize' or achievement.• The local media also carries news of the logistical concerns of organizers and the sheer size of a big convention intensifies public interest and the need for cooperative public input for a successful event. • At least some members of the community and the corporate community are persuaded to participate on the grounds that this is a unique opportunity to show local hospitality through volunteer- ism and financial support for hospitality events. The sense of people coming from ‘all over the world' is especially attractive to young cities and their 61ites seeking to enlarge their global impact. (Compare with the Olympic experience.)• When the mega-event is defined as a 'one-time' special opportunity to host this convention, there is a greater rationalization to treat the event much differently from other types of conferences.The intrusion-reaction modelWhen a convention as mega-event occurs in a host city, it is best described through an intrusion reaction model. Acquiring the large convention is usually considered a prize to which all energies in preparation must be mobilized. The sudden influx of delegates requires detailed attention to logistics and delegate services concerning which the host city does not want to be embarrassed. If one description of this process is 'planning to cope’, the other descriptor is the anticipation of economic benefits as measured by bed nights and per capita multipliers of delegate spending. In any case, the intrusion- reaction model makes the host city a rather passive community that braces itself for the influx and merely provides services as required or requested. Delegates are viewed as temporary though welcome interlopers on home territory, and the convention itself takes on a cocoon-like character with its own schedule of activities and events. The host community maintains a distance from the convention as a private event from which they are shut out, and theCommunity is only represented by the friendliness and competence of service personnel in the hospitality industry.While this relationship may be preferred by many as the least disruptive to the host community, there are two things it does not do. First, it does not personalize the welcome to the community. Visitors and service personnel are anonymous objects in a client relationship. Visitors can leave with no sense of local life and interaction with local people.Second, as a mega-event with significant local publicity, local people do not participate and cannotPersonally benefit from the event itself beyond economic spin-offs.The interactive-opportunity modelIn place of the intrusion-reaction models an interactive-opportunity model is proposed. This model visualizes the convention as a unique opportunity for host city/delegate interaction.From the host city's point of view, the visitor/delegate must be transformed from a client or temporary interloper to a 'guest' with all of the warmer meanings of hospitality attached to that term. Once a convention is defined as a mega-event, citizens with civic pride are reasonably easy to recruit as volunteers in the demonstration of local hospitality. Visitors are usually very impressed with the warmth exhibited by proactive volunteers and local staff.From the convention organizers' and delegates' point of view, the convention must not just colonize temporary space in a foreign territory but must view the community as a partner in the total convention experience. The convention should contain specified elements that are accessible to interested members of the community either at a reduced registration rate or for free, and these events should be publicized. Program organizers should also incorporate local distinctive (e.g. history, traditions, economic strengths) into their activities in creative ways that sustain positive feelings towards the local community.The objective of this approach is to move the convention-host city into a closer relationship which moves beyond merely the provision of facilities and services. When economic benefits are supplemented by interaction benefits, both the convention and the host community are strengthened in significant ways.Case studiesThree conventions were held in the city of Calgary, Alberta (750 000 population) in recent years that demonstrated the success of this approach. A North American denominational church convention drew 7000 delegates in 1988, a barbershop quartet convention drew 12 000 in 1993, and a convention of academic scholars drew 8000 in 1994. Each convention utilized the interactive-community model in a different way, but all three set new standards for their own groups and received especially positive reviews from delegates and convention sponsors.The denominational convention advertised select evening sessions with special speakers as open with- out charge. A pre-conference Music Festival was held at a downtown music hall using guest artists attending the convention but targeted primarily to local people. Host supporters put on a Chuck-wagon Breakfast theme for guests at no charge and in return delegates contributed to a convention legacy to the city for a shelter for abused persons. Dele- gates could indicate on their registration form whether they wanted to participate in a hospitality night in local homes. V olunteers in uniform provided a 'wall of friendship' around the meeting site to answer questions and explicitly to welcome dele- gates or thank them for coming,The barbershop quartet convention really strained the city's facilities, including the convention facilities, as the uniqueness of this event and caliber of the contesting musical groups also had a niche of interested city residents. Tickets were available to the public and hundreds of volunteers were mobilized to demonstrate hospitality. Guests were met at the airport by local volunteers with a proactive western welcome. A special rodeo event demonstrated the unique local tradition to alldelegates. Delegates also received free transit passes which facilitated access to all parts of the city rather than the usual mobility limitation to the downtown.The academic conference at the University of Calgary drew the community into its program through a special 'Community Participant' registration category purchased on site for C$10 and for which a list of sessions open to the public was exchanged. To commemorate the mega-event, a city-wide 'Celebration of Learning' was mounted which involved posters in every classroom, encouragement to every school to celebrate learning in some way during the event, special activities for the general public and high school students on campus, and special events in the community (especially downtown) to which the public was invited such as a Music Festival and Downtown Noon Hour Symposiums. V olunteers were used, primarily at hospitality functions, and chuck-wagon breakfasts and mountain ranch barbeques were thematic highlights with supper attendance as optional events.ConclusionConventions provide a unique opportunity to bring visitor and resident together because they are highly planned activities and of limited duration. In place of the passive hospitality preferred by visitor centers or the home-stay programs oriented to the individual traveler, the interactive-community model of conventions as mega-events opens up new possibilities for successful tourism.The interactive-opportunity model has the following benefits. From the convention sponsor's point of view, it allows the group to spread goodwill in the host community about its organization and its objectives. In other words, the convention organization reaps significant public relations benefits that lie dormant in the encapsulation model. Second, the host community has the opportunity for the event to enrich their lives through personal participation as desired and as specified, It is also able to demonstrate its friendly spirit and local culture in a highly personal way. From the tourist's perspective, Prentice et al refer to this as 'endearment behavior' to the destination location. 22 Third, the local organizers create a greater sense of a more successful convention to both visitors and residents, and the legacy of a successful event enhances the civic reputation and encourages return visits.Much of the literature on mega-events or hallmark events implies that these events have as their primary goal the enhancement of the site as a tourism destination, 2324 or that they are effective mechanisms in re-imaging a city for both residents and outsiders in a positive and dynamic manner.25 Certainly these outcomes may be a by-product of conventions, but the convention as a collective meeting has a rationale and objective all its own. On the other hand, the convention represents a special type of hallmark event that, from the point of view of a medium-size city, is a one-time event of limited duration (cf. Getz).When a convention becomes a mega-event to this type of host community, there are new possibilities for local organizers to create special benefits for local citizens that enrich the community beyond economic impacts. When viewed from this perspective, conventions are no longer intruders but guests and partners in a civic experience.会展业:会展与举办城市间的关系模式哈里摘要会展是从东道国社会的生态学高度分化出来的,代表一种特殊形式的旅游。