第三章 中国翻译史

- 格式:doc

- 大小:38.50 KB

- 文档页数:7

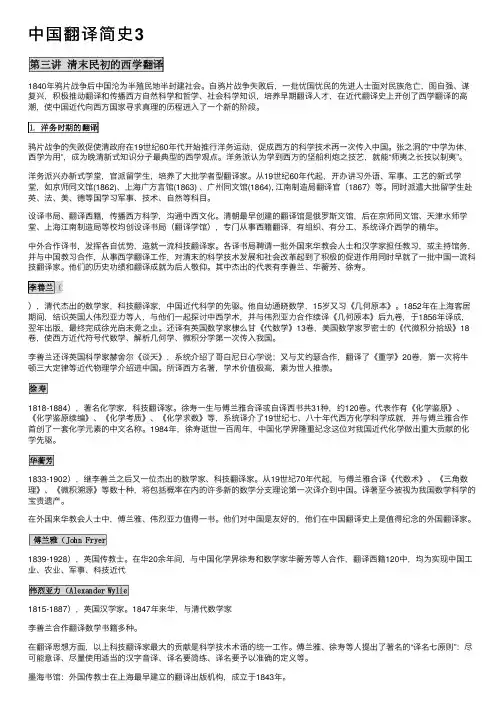

中国翻译简史31840年鸦⽚战争后中国沦为半殖民地半封建社会。

⾃鸦⽚战争失败后,⼀批忧国忧民的先进⼈⼠⾯对民族危亡,图⾃强、谋复兴,积极推动翻译和传播西⽅⾃然科学和哲学、社会科学知识,培养早期翻译⼈才,在近代翻译史上开创了西学翻译的⾼潮,使中国近代向西⽅国家寻求真理的历程进⼊了⼀个新的阶段。

鸦⽚战争的失败促使清政府在19世纪60年代开始推⾏洋务运动,促成西⽅的科学技术再⼀次传⼊中国。

张之洞的“中学为体,西学为⽤”,成为晚清新式知识分⼦最典型的西学观点。

洋务派认为学到西⽅的坚船利炮之技艺,就能“师夷之长技以制夷”。

洋务派兴办新式学堂,官派留学⽣,培养了⼤批学者型翻译家。

从19世纪60年代起,开办讲习外语、军事、⼯艺的新式学堂,如京师同⽂馆(1862)、上海⼴⽅⾔馆(1863) 、⼴州同⽂馆(1864), 江南制造局翻译官(1867)等。

同时派遣⼤批留学⽣赴英、法、美、德等国学习军事、技术、⾃然等科⽬。

设译书局、翻译西籍,传播西⽅科学,沟通中西⽂化。

清朝最早创建的翻译馆是俄罗斯⽂馆,后在京师同⽂馆、天津⽔师学堂、上海江南制造局等校均创设译书局(翻译学馆),专门从事西籍翻译,有组织、有分⼯、系统译介西学的精华。

中外合作译书,发挥各⾃优势,造就⼀流科技翻译家。

各译书局聘请⼀批外国来华教会⼈⼠和汉学家担任教习,或主持馆务,并与中国教习合作,从事西学翻译⼯作,对清末的科学技术发展和社会改⾰起到了积极的促进作⽤同时早就了⼀批中国⼀流科技翻译家。

他们的历史功绩和翻译成就为后⼈敬仰。

其中杰出的代表有李善兰、华蘅芳、徐寿。

),清代杰出的数学家,科技翻译家,中国近代科学的先驱。

他⾃幼通晓数学,15岁⼜习《⼏何原本》。

1852年在上海客居期间,结识英国⼈伟烈亚⼒等⼈,与他们⼀起探讨中西学术,并与伟烈亚⼒合作续译《⼏何原本》后九卷,于1856年译成,翌年出版,最终完成徐光启未竟之业。

还译有英国数学家棣么⽢《代数学》13卷,美国数学家罗密⼠的《代微积分拾级》18卷,使西⽅近代符号代数学、解析⼏何学、微积分学第⼀次传⼊我国。

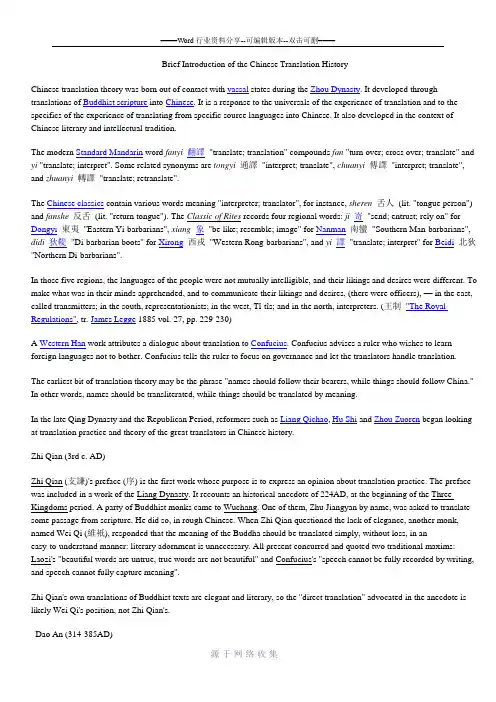

Brief Introduction of the Chinese Translation HistoryChinese translation theory was born out of contact with vassal states during the Zhou Dynasty. It developed through translations of Buddhist scripture into Chinese. It is a response to the universals of the experience of translation and to the specifics of the experience of translating from specific source languages into Chinese. It also developed in the context of Chinese literary and intellectual tradition.The modern Standard Mandarin word fanyi翻譯"translate; translation" compounds fan "turn over; cross over; translate" and yi "translate; interpret". Some related synonyms are tongyi通譯"interpret; translate", chuanyi傳譯"interpret; translate", and zhuanyi轉譯"translate; retranslate".The Chinese classics contain various words meaning "interpreter; translator", for instance, sheren舌人(lit. "tongue person") and fanshe反舌(lit. "return tongue"). The Classic of Rites records four regional words: ji寄"send; entrust; rely on" for Dongyi東夷"Eastern Yi-barbarians", xiang象"be like; resemble; image" for Nanman南蠻"Southern Man-barbarians", didi狄鞮"Di-barbarian boots" for Xirong西戎"Western Rong-barbarians", and yi譯"translate; interpret" for Beidi北狄"Northern Di-barbarians".In those five regions, the languages of the people were not mutually intelligible, and their likings and desires were different. To make what was in their minds apprehended, and to communicate their likings and desires, (there were officers), — in the east, called transmitters; in the south, representationists; in the west, Tî-tîs; and in the north, interpreters. (王制"The Royal Regulations", tr. James Legge 1885 vol. 27, pp. 229-230)A Western Han work attributes a dialogue about translation to Confucius. Confucius advises a ruler who wishes to learn foreign languages not to bother. Confucius tells the ruler to focus on governance and let the translators handle translation.The earliest bit of translation theory may be the phrase "names should follow their bearers, while things should follow China." In other words, names should be transliterated, while things should be translated by meaning.In the late Qing Dynasty and the Republican Period, reformers such as Liang Qichao, Hu Shi and Zhou Zuoren began looking at translation practice and theory of the great translators in Chinese history.Zhi Qian (3rd c. AD)Zhi Qian (支謙)'s preface (序) is the first work whose purpose is to express an opinion about translation practice. The preface was included in a work of the Liang Dynasty. It recounts an historical anecdote of 224AD, at the beginning of the Three Kingdoms period. A party of Buddhist monks came to Wuchang. One of them, Zhu Jiangyan by name, was asked to translate some passage from scripture. He did so, in rough Chinese. When Zhi Qian questioned the lack of elegance, another monk, named Wei Qi (維衹), responded that the meaning of the Buddha should be translated simply, without loss, in aneasy-to-understand manner: literary adornment is unnecessary. All present concurred and quoted two traditional maxims: Laozi's "beautiful words are untrue, true words are not beautiful" and Confucius's "speech cannot be fully recorded by writing, and speech cannot fully capture meaning".Zhi Qian's own translations of Buddhist texts are elegant and literary, so the "direct translation" advocated in the anecdote is likely Wei Qi's position, not Zhi Qian's.Dao An (314-385AD)Dao An focused on loss in translation. His theory is the Five Forms of Loss (五失本):1.Changing the word order. Sanskrit word order is free with a tendency to SOV. Chinese is SVO.2.Adding literary embellishment where the original is in plain style.3.Eliminating repetitiveness in argumentation and panegyric (頌文).4.Cutting the concluding summary section (義說).5.Cutting the recapitulative material in introductory section.Dao An criticized other translators for loss in translation, asking: how they would feel if a translator cut the boring bits out of classics like the Shi Jing or the Classic of History?He also expanded upon the difficulty of translation, with his theory of the Three Difficulties (三不易):municating the Dharma to a different audience from the one the Buddha addressed.2.Translating the words of a saint.3.Translating texts which have been painstakingly composed by generations of disciples.Kumarajiva (344-413AD)Kumarajiva’s translation practice was to translate for meaning. The story goes that one day Kumarajiva criticized his disciple Sengrui for translating “heaven sees man, and man sees heaven” (天見人,人見天). Kumarajiva felt that “man and heaven connect, the two able to see each other” (人天交接,兩得相見) would be more idiomatic, though heaven sees man, man sees heaven is perfectly idiomatic.In another tale, Kumarajiva discusses the problem of translating incantations at the end of sutras. In the original there is attention to aesthetics, but the sense of beauty and the literary form (dependent on the particularities of Sanskrit) are lost in translation. It is like chewing up rice and feeding it to people (嚼飯與人).Huiyuan (334-416AD)Huiyuan's theory of translation is middling, in a positive sense. It is a synthesis that avoids extremes of elegant (文雅) and plain (質樸). With elegant translation, "the language goes beyond the meaning" (文過其意) of the original. With plain translation, "the thought surpasses the wording" (理勝其辭). For Huiyuan, "the words should not harm the meaning" (文不害意). A good translator should “strive to preserve the original” (務存其本).Sengrui (371-438AD)Sengrui investigated problems in translating the names of things. This is of course an important traditional concern whose locus classicus is the Confucian exhortation to “rectify names” (正名). This is not merely of academic concern to Sengrui, for poor translation imperils Buddhism. Sengrui was critical of his teacher Kumarajiva's casual approach to translating names, attributing it to Kumarajiva's lack of familiarity with the Chinese tradition of linking names to essences (名實).Sengyou (445-518AD)Much of the early material of earlier translators was gathered by Sengyou and would have been lost but for him. Sengyou’s approach to translation resembles Huiyuan's, in that both saw good translation as the middle way between elegance and plainness. However, unlike Huiyuan Sengyou expressed admiration for Kumarajiva’s elegant translations.Xuanzang (600-664AD)Xuanzang’s theory is the Five Untranslatables (五種不翻), or five instances where one should transliterate:1.Secrets: Dharani 陀羅尼, Sanskrit ritual speech or incantations, which includes mantras.2.Polysemy: bhaga (as in the Bhagavad Gita) 薄伽, which means comfortable, flourishing, dignity, name, lucky,esteemed.3.None in China: jambu tree 閻浮樹, which does not grow in China.4.Deference to the past: the translation for anuttara-samyak-sambodhi is already established as Anouputi 阿耨菩提.5.To inspire respect and righteousness: Prajna 般若instead of “wisdom” (智慧).Daoxuan (596-667AD)Yan Fu (1898)Yan Fu is famous for his theory of fidelity, clarity and elegance (信達雅), which some believe originated with Tytler. Yan Fu wrote that fidelity is difficult to begin with. Only once the translator has achieved fidelity and clarity should he attend to elegance. The obvious criticism of this theory is that it implies that inelegant originals should be translated elegantly. Clearly, if the style of the original is not elegant or refined, the style of the translation should not be elegant either.Liang Qichao (1920)Liang Qichao put these three qualities of a translation in the same order, fidelity first, then clarity, and only then elegance.Lin Yutang (1933)Lin Yutang stressed the responsibility of the translator to the original, to the reader, and to art. To fulfill this responsibility, the translator needs to meet standards of fidelity (忠實), smoothness (通順) and beauty.Lu Xun (1935)Lu Xun's most famous dictim relating to translation is "I'd rather be faithful than smooth" (寧信而不順).Ai Siqi (1937)Ai Siqi described the relationships between fidelity, clarity and elegance in terms of Western ontology, where clarity and elegance are to fidelity as qualities are to being.Zhou Zuoren (1944)Zhou Zuoren assigned weightings, 50% of translation is fidelity, 30% is clarity, and 20% elegance.Zhu Guangqian (1944)Zhu Guangqian wrote that fidelity in translation is the root which you can strive to approach but never reach. This formulation perhaps invokes the traditional idea of returning to the root in Daoist philosophy.Fu Lei (1951)Fu Lei held that translation is like painting: what is essential is not formal resemblance but rather spiritual resemblance (神似).Qian Zhongshu (1964)Qian Zhongshu wrote that the highest standard of translation is transformation (化, the power of transformation in nature): bodies are sloughed off, but the spirit (精神), appearance and manner (姿致) are the same as before (故我, the old me or the ol。

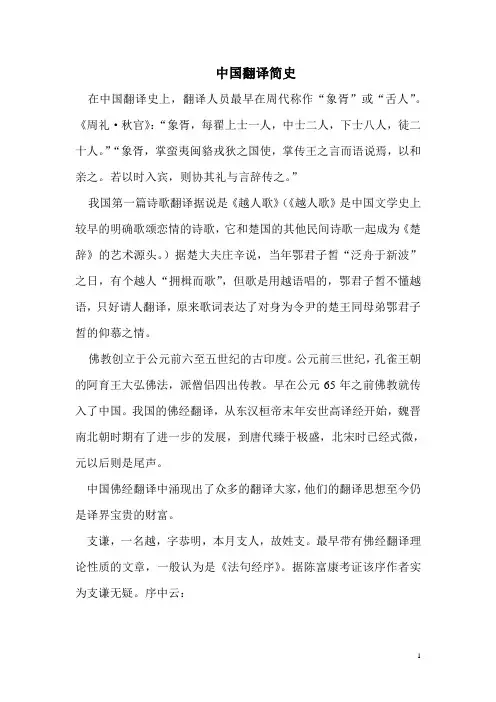

中国翻译简史在中国翻译史上,翻译人员最早在周代称作“象胥”或“舌人”。

《周礼·秋官》:“象胥,每翟上士一人,中士二人,下士八人,徒二十人。

”“象胥,掌蛮夷闽貉戎狄之国使,掌传王之言而语说焉,以和亲之。

若以时入宾,则协其礼与言辞传之。

”我国第一篇诗歌翻译据说是《越人歌》(《越人歌》是中国文学史上较早的明确歌颂恋情的诗歌,它和楚国的其他民间诗歌一起成为《楚辞》的艺术源头。

)据楚大夫庄辛说,当年鄂君子皙“泛舟于新波”之日,有个越人“拥楫而歌”,但歌是用越语唱的,鄂君子皙不懂越语,只好请人翻译,原来歌词表达了对身为令尹的楚王同母弟鄂君子皙的仰慕之情。

佛教创立于公元前六至五世纪的古印度。

公元前三世纪,孔雀王朝的阿育王大弘佛法,派僧侣四出传教。

早在公元65年之前佛教就传入了中国。

我国的佛经翻译,从东汉桓帝末年安世高译经开始,魏晋南北朝时期有了进一步的发展,到唐代臻于极盛,北宋时已经式微,元以后则是尾声。

中国佛经翻译中涌现出了众多的翻译大家,他们的翻译思想至今仍是译界宝贵的财富。

支谦,一名越,字恭明,本月支人,故姓支。

最早带有佛经翻译理论性质的文章,一般认为是《法句经序》。

据陈富康考证该序作者实为支谦无疑。

序中云:诸佛典皆在天竺,天主言语,与汉异音。

云其书为天书,语为天语。

名物不同,传实不易。

唯昔蓝调、安侯、世高、都尉、佛调,译胡为汉,审得其体,斯以难继。

后之传者,虽不能密,犹尚贵其实,粗得大趣。

始者维祗难出自天竺,以黄武三年来适武昌。

仆从受此五百偈本,请其同道竺将炎为译。

将炎虽善天竺语,未备晓汉。

其所传言,或得胡语,或以意出音,近于质直。

仆初嫌其辞不雅。

维祗难曰:“佛言,依其义不用饰取其法不以严。

其传经者,当令易晓,勿失厥义,是则为善。

”座中咸曰:“老氏称‘美言不信,信言不美’。

仲尼亦云:‘书不尽言,言不尽意。

’明圣人意,深邃无极。

今传胡义,实宜径达。

”是以自偈受译人口,因循本旨,不加文饰。

译所不解,则阙不传,故有脱失,多不出者。

《英汉翻译教程》第一章:我国翻译史简介我国的翻译事业有约两千多年的光辉历史。

早在公元前六年西汉哀帝时代,伊存到中国口传一些佛教经句,但还谈不上佛教的翻译。

佛经的翻译是在东汉桓帝建和两年(公元148年)开始的,译者是安世高,他是安息人(即波斯),他译了《安般守意经》等三十多部佛经。

过些时候,娄迦谶来中国,因为他是月支人,所以又称支娄迦谶。

他也译了十多部佛经,但文笔生硬,不易看懂,所以从那时起,大概就有直译和意译这个问题了。

他有个学生叫支亮,支亮又有个弟子叫支谦,他们三人号称“三支”,都是当时翻译佛经很有名的人。

就在那时,月支派里出现了一个叫竺法护的大翻译家,他译了175部佛经,对于佛法的流传贡献很大。

但这些翻译活动还只是民间私人事业。

到了符秦时代,释道安设置了“译场”,成了有组织的活动,他本人不懂梵文,惟恐失真,主张严格的直译,在这期间他请来了天竺人(即印度)鸠摩罗什,他全改以前群家的直古风格,主张“意译”,他的译著为我国翻译文学奠定了基础。

到南北朝时,一个叫真谛的印度佛教学者应梁武帝之聘来到中国,他译了49部经论,对中国佛教思想有较大影响。

从隋代(公元590年)起到唐代,是我国翻译事业高度发达的时期,隋代有个释彦琮,梵文造诣很深。

在他以后出现了古代翻译界的巨星玄奘(与上述鸠摩罗什、真谛一起号称我国佛经三大翻译家),他成为第一个把汉文著作向国外介绍的中国人,他自创了“新译”。

从明代万历年间到清代“清学”时期,佛经翻译呈现一片衰落现象,但却出现了以徐光启、林纾(琴南)、严复(又陵)等为代表的介绍西欧各国科学、文学、哲学的翻译家。

徐光启和意大利人利玛窦合作,翻译了欧几里得的《几何原本》、《测量法义》等书。

林纾和他的合伙人以口述笔记的方式译了160多部文学作品,其中最著名的有《巴黎茶花女遗事》、《黑奴吁天录》、《块肉余生记》、《王子复仇记》等。

严复是我国清末新兴资产阶级启蒙思想家(曾担任过北大校长),等到八国联军战役以后,他避居上海,搞翻译工作,他“曾查过汉晋六朝翻译佛经的方法”,破天荒第一次在《天演论·译例言》里正面提出了信达雅作为译事楷模。

第三个时期“五四”运动是中国革命运动的一个新起点,也是我国近代翻泽史的分水岭。

这一时期的翻译工作不论在内容上,还是在形式上,都发生了根本的变化。

就所翻译的内容们言,马克思列宁主义的著作刀:始翻译介绍到中国来。

原苏联等同的文学作抓也逐渐有了汉译本.一些世界名著也有了较多的汉译本:就泽作的语言而言.白话义在译作中己出了统治地位。

这一时期的翻译,对当时中同社会的政治、经济、文化等各方面,以及唤起民众,推进新民主主义革命的进程都产生丁深远的影响。

这一—i付期的主要译作有:1.社会政治著作。

除“万四”前夕出版的《共产党宣言》汉译本又有多次再版外,还翻译了《资本论入门》、《丁钱劳动与资本》、《俄国共产党党纲》、《左派幼稚病》、《帝国主义论》、《资本论》、《马克思恩格斯沦巾国》等马列主义著作。

2文学作品方面。

随着“五四”以后文学革命运动的发展,世界进步文学和俄罗斯苏维埃文学逐渐被介绍到我国束、其中尤以俄罗斯文学和法国文学介绍得最多,影响也最大。

俄罗斯著名作家普希金及其作品《叶甫盖尼‘奥涅金》、托尔斯泰及其作品《战争与和平》、果戈里及其作品《钦差大厦》、居格涅夫及其作品《父勺子》,以及前苏联作家高尔基、法捷耶夫的作品也在这个时期翻译介绍过来,法国著名作家英里哀及其作品《伪君子》、巴尔扎克及其作员《高老头》、大仲马及其作品《基度山伯爵》、雨果及其作品《悲惨世界》。

东方各国的优秀作品,如《天方夜谭》、印度泰戈尔的《新月集》等泽本也在这—‘时期与广大小国读者见面了。

深圳翻译公司在介绍翻译上述作品中,我同很多作家、翻译家为此做出丁卓越的页献。

这—时期的主要翻译家有:鲁迅先半不仅是‘依伟大的革命家、思想家、文学家.而且是一位伟大的翻译家。

鲁迅一牛翻译丁十四个国家的近一百名作家的二百多部作品,包括小说、故事、诗歌、戏剧、童话、科幻、文学理论等。

鲁迅先午对翻译工作的态度是十分谨慎和严肃的。

他把翻译外国作佩比作普岁米修斯,咨来大火,传播人间。

第一章当代研究视角下的翻译史1. 翻译产生是出于不同语言的民族之间的交际需求2. 宗教典籍的翻译持续了上千年,而在这个漫长的历史过程中,译者们确立了对翻译的基本认识,这包括翻译的性质,基本的方法,质量标准等等。

3. 文学翻译在传播文化、丰富本国文化的同时,更进一步地探讨翻译的作用、方法。

4. 非文学翻译随着时代的发展而日益增多,使翻译的规模不断扩大,成为一一个专门的职业领域。

第二章中国翻译史的分期1. 西方翻译理论研究的两大转向与三个根本性的突破指的是什么?两大转向:语言学转向与文化转向;三个根本性突破:从一般层面上的语言间的对等研究深入到对翻译行为本身的深层研究;不再局限于翻译文本本身的研究,而是关注译作的生产和消费过程;不再把翻译看成是语言转换时的孤立片段,而是将它放在文化语境中去研究;(Page 32)2. 为什么说1898年正式拉开了20世纪中国翻译文学史的帷幕?梁启超《译印政治小说序》催热政治小说翻译;严复提出”信、达、雅“;林纾版《巴黎茶花女遗事》(Page 36)第三章中国的佛经翻译1. 东汉末年的佛经翻译特与著名译者这一时期的佛经翻译无原本,凭外来僧人的口授;译者多是外来僧人,因此译经往往合作完成,即”集体翻译“,总体的翻译水平不高。

由于没有政府的支持,译作零星。

译本中有详细的注释。

由于缺乏经验,一般采用直译。

(Page 47-48)译经的始创者安世高2. 两晋和南北朝时期的佛经翻译特点与著名译者这一时期的佛经翻译脱离了私人小规模翻译,变为大规模的译场;译场有了较细的分工;传译与讲习相结合,因此使翻译带有研究性质;原本往往不止一种;理论与技巧加强:五失本、三不易、八备说、依实出华等。

第一个中国译者道安,鳩摩罗什3. 唐宋时期的佛经翻译特点与著名译者译者不再进行讲习研究,单独进行翻译,译场规模较前一阶段小了;译场分工完善,对于译者能力极为挑剔。

佛经翻译之巨星玄奘4. 中国古代佛经翻译的翻译方法对佛教的中国化有什么影响?为什么会有这样的影响?中国古代佛经翻译借用道家概念来类比佛经概念,很容易为中土人所接受,这使印度佛教找到了与中国本土文化结合的结合点,也进一步推动了佛教在中国的传播。

第二编:中西翻译简史第三章中国翻译简史我国的翻译有着数千年的历史。

打开这一翻译史册,我们可以看到翻译高潮迭起,翻译家难以计数,翻译理论博大精深。

了解这一历史不仅有助于我们继承我们的先人的优秀文化遗产,而且也有助于我们今天更加深入认识和发展我们的翻译事业。

简单说来,中国的翻译史大致可以分为以下几个阶段:一、汉代-符秦时期;二、隋-唐-宋时期;三、明清时期;四、五四时期;五、新中国成立至今。

一、汉代-秦符时期中国的翻译活动可以追溯到春秋战国时代。

当时的诸侯国家相互之间交往就出现了翻译,如楚国王子去越国时就求助过翻译。

当然这种翻译还谈不上是语际翻译。

中国真正称得上语际翻译的活动应该说是始于西汉的哀帝时期的佛经翻译。

那时有个名叫伊存的人到中国来口传一些简单的佛经经句。

到了东汉桓帝建和二年(公元一八四年),佛经翻译就正式开始了。

译者安世高是安息(即波斯)人,他翻译了《安般守意经》等三十多部佛经。

后来月支人支娄迦谶(又叫娄迦谶)来到了中国,他翻译了十多部佛经。

支娄迦谶译笔生硬,基本上是字对字、句对句地翻译,中国读者不易看懂。

中国翻译界现在的直译和意译之争大概就是从这个时候开始的。

支娄迦谶有个学生叫支亮,之亮有个弟子叫支谦。

他们三人号称"三支",是当时翻译佛经非常有名的译者。

与"三支"同时从事佛经翻译的还有竺法护。

他也是月支人,是当时的佛经翻译名家,总共译了一百七十五部佛经,对佛经在中国的流传贡献不小。

竺法护和"三支"一道被人称作月之派。

不过,这一时期的佛经翻译活动还只是民间私人事业。

到了符秦时代,佛经翻译活动就组织有序了。

当时主要的组织者是释道安。

在他的主持下设置了译场,开始了大规模的佛经翻译。

由于释道安本人不懂梵文,惟恐译文失真,因此他主张严格的词对词、句对句(word for word, line for line)的直译。

当时的佛经《鞞婆沙》就是按此方法从梵文译成汉语的。

为了把握好译文的质量,释道安在此期间请来了著名的翻译家天竺(即印度)人鸠摩罗什。

鸠氏考证了以前的佛经翻译,批评了翻译的风格,检讨了翻译的方法。

他主张意译,纠正了过去音译的弱点,提倡译者署名,以示负责。

他翻译了三百多卷佛经文献,如《金刚经》、《法华经》、《十二门论》、《中观论》、《维摩经》等。

其译文神情并茂、妙趣盎然,堪称当时的上乘之译作,至今仍被视为我国文学翻译的奠基石。

到了南北朝时期,梁武帝特聘印度佛教学者真谛(Paramartha,499-569)到中国来翻译佛经。

真谛在华期间共翻译了四十九部经书,其中尤以《摄大乘论》的翻译响誉华夏,对中国佛教思想影响较大。

二、隋-唐-宋时代从隋代(公元五九0年)到唐代,这段时间是我国翻译事业高度发达时期。

隋代历史较短,译者和译作都很少。

比较有名的翻译家有释彦琮(俗姓李,赵郡柏人)。

他是译经史上第一位中国僧人。

一生翻译了佛经23部100余卷。

彦琮在他撰写的《辨证论》中总结翻译经验,提出了作好佛经翻译的八项条件:1)诚心受法,志愿益人,不惮久时(诚心热爱佛法,立志帮助别人,不怕费时长久);2)将践觉场,先牢戒足,不染讥恶(品行端正,忠实可信,不惹旁人讥疑);3)荃晓三藏,义贯两乘,不苦闇滞(博览经典,通达义旨。

不存在暗昧疑难的问题);4)旁涉坟史,工缀典词,不过鲁拙(涉猎中国经史,兼擅文学,不要过于疏拙);5)襟抱平恕。

器量虚融,不好专执(度量宽和,虚心求益,不可武断固执);6)耽于道术,淡于名利,不欲高炫(深爱道术,淡于名利,不想出风头);7)要识梵言,乃闲正译,不坠彼学(精通梵文,熟悉正确的翻译方法,不失梵文所载的义理);8)薄阅苍雅,粗谙篆隶。

不昧此文(兼通中训诂之学,不使译本文字欠准确)。

彦琮还说,"八者备矣,方是得人"。

这八条说的是译者的修养问题,至今仍有参考价值。

在彦琮以后,出现了我国古代翻译界的巨星玄奘(俗称三藏法师)。

他和上述鸠摩罗什、真谛一起号称华夏三大翻译家。

玄奘在唐太宗贞观二年(公元六二八年)从长安出发去印度取经,十七年后才回国。

他带回佛经六百五十七部,主持了中国古代史上规模最大、组织最为健全的译场,在十九年间译出了七十五部佛经,共一三三五卷。

玄奘不仅将梵文译成汉语,而且还将老子著作的一部分译成梵文,是第一个将汉语著作向外国人介绍的中国人。

玄奘所主持的译场在组织方面更为健全。

据《宋高僧传》记载,唐代的翻译职司多至11种:1)译主,为全场主脑,精通梵文,深广佛理。

遇有疑难,能判断解决;2)证义,为译主的助手,凡已译的意义与梵文有和差殊,均由他和译主商讨;3)证文,或称证梵本,译主诵梵文时,由他注意原文有无讹误;4)度语,根据梵文文字音改记成汉字,又称书字;5)笔受,把录下来的梵文字音译成汉文;6)缀文,整理译文,使之符合汉语习惯;7)参译,既校勘原文是否有误,又用译文回证原文有无歧异;8)刊定,因中外文体不同,故每行每节须去其芜冗重复;9)润文,从修辞上对译文加以润饰;10)梵呗,译文完成后,用梵文读音的法子来念唱,看音调是否协调,便于僧侣诵读;11)监护大使,钦命大臣监阅译经。

玄奘在翻译理论方面作出了自己的贡献。

他根据自己的理解和翻译实践提出了"既须求真,又须喻俗"的翻译标准,意即"忠实""通顺",直到今天仍有指导意义。

他还在翻译实践中创造性地运用了多种翻译技巧。

据印度学者柏乐天和我国学者张建木的研究结果显示,玄奘运用了下列翻译技巧:1)补充法(就是现在我们常说的增词法);2)省略法(即我们现在常说的减词法);3)变位法(即根据需要调整句序或词序);4)分合法(大致与现在所说分译法和合译法相同);5)译名假借法(即用另一种译名来改译常用的专门术语);6)代词还原法(即把原来的代名词译成代名词所代的名词)。

这些技巧对今天的翻译实践同样仍然具有十分重要的指导意义。

与玄奘同时的还有失义难陀、义净、一行、不空等译者,也都译了许多佛经。

唐末无人赴印度求经,佛经翻译事业逐渐衰微。

到了宋代,佛经翻译已远不如唐初的极盛时期。

在北宋的乾德开宝年间,宋太祖曾派人西去求经,印度也派名僧东来华夏传法。

宋太祖也曾在开封的太平兴国寺内兴修了译经院,专事佛经翻译。

虽译场组织极其完备,译经种数几乎接近唐代,但质量却不如唐代。

当时有名的僧侣译者主要有天息、法护等人。

在翻译理论方面颇有贡献的要数赞宁(俗姓高,今浙江德清人)。

他曾归纳了以往译经的各种情况,提出了解决翻译过程中各类矛盾的六种办法。

这是对我国唐代翻译理论的继续和发展,是我国翻译论库中的宝贵财富。

到了南宋,由于社会动荡等原因,佛经翻译已是寥寥无几,史书的记载中无一例翻译。

在其后的元代,统治者曾下昭拔合恩巴、管主八等人翻译佛经,但译作只有十几部,翻译理论方面的探讨更是无从谈起。

翻译事业基本处于停滞状态。

三、明清时代在明代的二百多年历史中,佛经翻译呈现一片衰落的局面。

佛经译者只有智光等一、二人,译了几部经书。

但到了明代万历年间直至清朝"新学"时期,我国出现了以徐光启、林纾(琴南)、严复(又陵)等为代表的介绍西欧各国科学、文学、哲学的翻译家。

明代徐光启和意大利人利马窦合作,翻译了欧几里得的《几何原理》、《测量法义》等书。

清代的林纾(1852.11.8-1924.10.9)和他的合作者以口述笔记的方式翻译了一百八十四种西方文学作品,达一千万字以上。

所译小说中最著名的有《巴黎茶花女遗事》(La Dame aux Camelias)、《黑奴呼天录》(Uncle Tom's Cabin)、《块肉余生述》(David Copperfield)、《王子复仇记》(Hamlet)等。

林纾本人不懂外文,因而他的译作删减、遗漏、随意添加之处甚多。

但是林纾的翻译对于中国读者了解西方文学作品起到了很大的作用。

严复(1954.1.18-1921.10.27)是我国清末新兴资产阶级的启蒙思想家。

他从光绪二十四年到宣统三年(公元1898-1911)这三十年间翻译了不少西方政治经济学说,如赫胥黎(T。

H。

Huxley)的《天演论》(Evolution and Ethics and Other Essays)、亚当﹒斯密(A。

Smith)的《原富》(An Inquiry into the Nature and Cause of the Wealth of Nations)﹑孟德斯鸠(C.L.S. Montesquieu)的《法意》(L'esprit des Lois)、斯宾塞尔(H。

Spencer)的《群学肆言》(On Liberty)、甄克思(E。

Jenks)的《社会通诠》(A History of Politics)等。

严复每译一书,都有一定的目的和意义,常借西方著名资产阶级思想家的著作表达自己的思想。

他译书往往加上许多按语,发挥自己的见解。

严复"曾经查过汉晋六朝翻译佛经的方法"(鲁迅《二心集》),在参照古代佛经翻译经验的基础上,结合自己的翻译实践,在《天演论》(公元一八九八年出版)卷首的《译例言》中提出著名的"信、达、雅"翻译标准。

他说:"译事三难:信、达、雅。

求其信,已大难矣!顾信矣,不达,虽译,犹不译也,则达尚焉。

"有人因此认为严复偏重于"达",把"信"、"达"相互对立起来。

事实上,严复曾紧接着解释道:"至原文词理本深,难于共喻,则当前后引衬,以显其意,凡此经营,皆所以为达,为达即所以为信也。

"这说明严复并没有把"信"、"达"割裂开来,他主张的"信"是"意义不倍(背)本文","达"是不拘泥于原文形式,尽译文语言的能事以求原意明显,为"达"也是为"信",两者是统一的。

但严复对"雅"的解释今天看来是不足取的。

他的"雅"是指脱离原文而片面追求译文本身的古雅。

他认为只有译文本身采用"汉以前字法句法"--实际上即所谓上等的文言文,才算登大雅之堂。

严复自己在翻译实践中所遵循的也是"与其伤雅,毋宁失真",因而译文不但艰深难懂,又不忠实于原文,类似改编。

有人说严复用一个"雅"字打消了"信"和"达",这个批评不是没有根据的。

不过从积极的一面来看,严复重视译文文字润饰这一点却是值得我们注意的。