乔治奥威尔 (1)

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:1.62 MB

- 文档页数:24

乔治奥威尔英国作家与评论家乔治奥威尔(George Orwell)是20世纪英国最重要的作家之一,也是一位著名的评论家。

他以揭示现实社会的丑陋和不公而著称,对人类自由、政治和社会问题进行了深刻的思考和观察。

本文将从他的生平、作品和评论角度来探讨乔治奥威尔的影响。

一、生平乔治奥威尔的原名是埃里克·布莱尔(Eric Blair),1903年生于印度的摩加迪沙(现教义那格尔市)。

他的父亲是英国官员,因此他在印度度过了童年。

后来,他回到英国接受教育,并参加了英国殖民地警察。

在印度生活和殖民地警察工作的经历,为他后来的写作提供了珍贵的素材与触动。

二、作品乔治奥威尔的作品广泛而多样,涵盖了小说、散文、评论和报告等多个领域。

他最著名的作品包括小说《1984》和《动物农场》。

这两部小说都揭示了极权主义和政治操控对人类自由和社会发展所造成的危害。

《1984》被视为奥威尔最伟大的作品之一。

这部小说描绘了一个极权主义的未来世界,以集体崇拜、思想控制和言语操纵为主题。

通过对主人公温斯顿·史密斯的追踪和迫害,以及大胆而恐怖的政府机构“Big Brother”的存在,奥威尔揭示了极权主义对人类自由和个体思想的摧残。

《动物农场》是一部讽刺和寓言作品,以一群动物反抗人类统治的故事为背景。

这部小说暗喻着苏联共产主义运动的失败和领导人的背叛。

通过描述农场动物的斗争和最终的堕落,奥威尔揭示了权力腐败和统治阶级对人民利益的背叛。

除了小说,奥威尔的散文和评论作品同样重要。

他写了大量的社论和报告,对政治、战争、言论自由和社会不公进行批判和观察。

他的散文作品常常以简洁而直接的语言,剖析问题的本质。

他的观点和分析常常冷静而尖锐,深深影响着后世的读者和评论家。

三、评论家作为一位评论家,乔治奥威尔对当时的政治和社会现象持有独到的见解。

他对纳粹主义、共产主义和英国民主制度等都进行了严密的分析。

他的作品展现了他对现实的敏锐观察和对不公正的坚决反对。

20世纪英国文学:乔治·奥威尔和艾米丽·勃朗特的作品探析引言英国文学历史悠久,20世纪是该国文学发展的重要时期。

本文将关注两位伟大的英国作家:乔治·奥威尔和艾米丽·勃朗特。

他们在20世纪均有杰出的作品,对于当代文学及社会议题产生了巨大影响力。

通过分析和探讨他们的作品,我们可以更深入地理解他们对社会、政治以及人性等主题所做出的独特贡献。

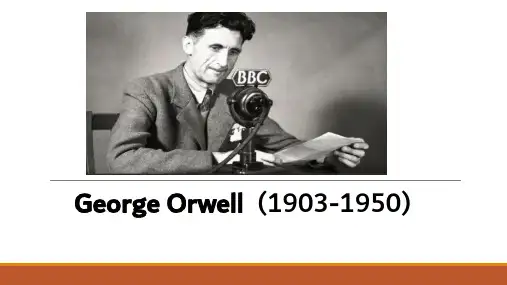

乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell)生平背景乔治·奥威尔(Eric Arthur Blair)是一位生于1903年的英国作家和记者。

他在早年经历了种种困苦和社会问题,这些经历深刻地影响了他后来的写作风格与观点。

代表作品《1984》《1984》是乔治·奥威尔最具标志性的作品之一,该小说描绘了一个极权主义统治下的未来社会。

其中包括智能监视、思想控制等主题,展现了奥威尔对于权力滥用和个人自由的忧虑。

《动物庄园》《动物庄园》是一部寓言小说,以农场上发生的斗争为背景,旨在暗喻着苏联共产主义体制下的腐败和剥削。

通过动物们反抗压迫者的故事,奥威尔揭示了权力斗争和革命运动中普遍存在的问题。

影响乔治·奥威尔以其独特的笔触和思想深度影响了后世作家及读者群体。

他对政治和社会问题敏锐的洞察力,塑造出鲜明的文学形象,并引发了对人类本性、个人自由与权力之间关系等议题的深刻思考。

艾米丽·勃朗特(Emily Brontë)生平背景艾米丽·勃朗特(Emily Brontë)是19世纪中期英国文学中最重要并备受赞誉的女作家之一。

她生于1818年,在一个有文化才华的家族中长大,并与姐姐夏洛特·勃朗特和安妮·勃朗特共同创作了众多重要的作品。

代表作品《呼啸山庄》《呼啸山庄》是艾米丽·勃朗特唯一的小说,被誉为英国文学史上最伟大的爱情小说之一。

故事讲述了两个家族之间复杂的关系、矛盾的爱情以及对人性黑暗面的深入探索。

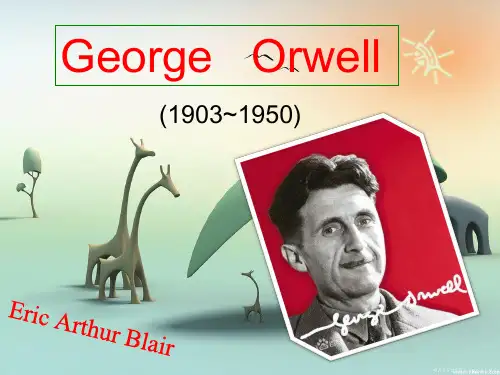

问世乔治奥威尔的预言与警示【问世乔治奥威尔的预言与警示】乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell)是20世纪英国著名作家,他的作品《1984》和《动物农场》对于现实社会有着深刻的预言与警示。

这两部小说通过揭示权力滥用和独裁统治的危险性,引起了人们对自由、隐私和真实性的思考与警觉。

本文将从三个方面探讨奥威尔的预言与警示。

第一,奥威尔预言了政府滥用权力的可能性。

在《1984》中,奥威尔描绘了一个极权主义的世界,由党(Party)掌控一切。

党使用监视、恐吓和虚假宣传等手段,彻底控制了人民的思想和行为。

这种权力滥用的情景似乎与现代社会的某些现象相呼应。

很多国家的政府通过监控技术和大数据分析手段收集、掌握人们的个人信息,从而影响和操控人们的思想和行为。

奥威尔的预言提醒我们要警惕政府滥用权力的可能性,保护个人隐私和自由。

第二,奥威尔预言了真实性的崩溃。

在《1984》和《动物农场》中,奥威尔都强调了“宣传”对于建立统治的重要性。

党通过改写历史、制造虚假的信息和控制媒体来操纵人们的思想。

这种情景也与现代社会中出现的“假新闻”和信息泛滥的问题相吻合。

网络时代的到来,使得信息的传播更加便捷和广泛,同时也给了不良势力传播谣言和虚假信息的机会。

奥威尔的预言警示我们要对信息进行深入思考和辨别,追求真相而非受制于虚假的宣传。

第三,奥威尔警示了群众对于独裁统治的被动接受。

在《动物农场》中,奥威尔通过动物反抗人类的描写,揭示了群众对于独裁统治的被动接受与被欺骗的现象。

动物农场最初是由动物们推翻人类统治建立的一个社会主义乌托邦,但最终发展成了一个由猪作为代表的独裁政权。

这个过程反映了社会中对于权力的渴望和个体思维的被腐蚀。

奥威尔的警示告诉我们,不能盲目接受权力的偏差和违背公义的统治,需要保持警觉和积极行动,捍卫自由和民主。

回顾奥威尔的预言与警示,我们发现其中很多情景和现实社会有着紧密的联系。

政府滥用权力、真实性的崩溃和群众对独裁统治的被动接受,这些问题在当代社会依然存在,并且可能变得更加复杂和严峻。

乔治奥威尔英国作家与的作者乔治奥威尔:英国作家与政治观察家乔治奥威尔(George Orwell)是20世纪英国最着名的作家之一,同时也是一位重要的政治观察家。

他以其独特的写作风格和对社会政治的深刻洞察力而著称。

在他的作品中,他关注并揭示了权力、压迫、自由和真相的重要性。

本文将介绍乔治奥威尔的生平背景、主要作品以及对社会和政治的深远影响。

一、生平背景乔治奥威尔(本名埃里克·亚瑟·布莱尔,Eric Arthur Blair)于1903年6月25日出生在英国印度一个中产阶级家庭。

他的父亲是一位英国官员,母亲是在印度教育学校任教的人。

由于父亲的工作关系,乔治在他的早年时光里经历了英属印度和英国的两种文化背景,这对他的成长产生了深远的影响。

二、主要作品1. 《动物庄园》《动物庄园》是乔治奥威尔最著名的作品之一。

这部博览了社会政治和革命的寓言小说,以一群农场动物的故事揭示了权力滥用和暴政的真相。

通过动物庄园这个象征性的社会,奥威尔暗示了社会阶级的分化和领导者腐败的危险性。

这部小说成为了对集权主义和极权主义的强烈批评,深刻地触动了世人的心弦。

2. 《1984》《1984》被认为是奥威尔最伟大的作品之一,也是他最为知名的小说之一。

这部小说以极权主义社会下的恐怖统治为背景,揭示了个人自由和隐私权受到侵犯的危险。

故事中的主人公温斯顿·史密斯在一个叫做“大哥”的独裁者统治下开始质疑现实,并试图反抗。

通过对思想控制和真相扭曲的描述,这本书为后世对政府监控和个人自由的关注提供了书写的基础。

三、对社会和政治的影响乔治奥威尔的作品不仅仅是文学作品,更是对社会和政治的深度观察。

他对于权力的批评和对个人自由的呼喊影响了世界各地的读者和思想家。

尤其是《1984》中描述的极权主义社会,在许多国家和时期仍然有着深刻的现实意义。

奥威尔的笔下,警示了人们对于权力滥用和真相扭曲的警觉。

他提醒人们要保持批判思维,并时刻警惕独裁统治的威胁。

乔治奥威尔的反乌托邦之作乔治奥威尔(George Orwell)是英国作家,在他的作品中经常探讨政治和社会问题。

他的一部作品特别引人注目,那就是《1984》。

这部小说成为了世界文学史上最著名的反乌托邦之作。

《1984》是乔治奥威尔于1949年出版的一部小说。

故事背景设定在一个极权主义的社会,主要讲述了一个由党派控制的虚构国家——大洋国(Oceania)。

在这个国家里,党派通过操控历史和语言掌握了绝对权力,一切都被严密监控和控制,人民的思想和自由被剥夺。

小说的主人公是温斯顿·史密斯(Winston Smith),他是国民党党派的一员,但却逐渐觉醒并开始对党派的统治产生怀疑。

他通过日记和秘密恋情来表达自己的反抗意志,但最终他还是被党派抓获,并经历了心灵和肉体上的残酷折磨。

小说以终极的绝对权力和对个体的完全消灭来揭示了反乌托邦社会的残酷与荒谬。

在《1984》中,乔治奥威尔描绘了一种极其严苛和恐怖的社会现实。

这个世界里,人民被无处不在的监视所包围,言论自由被禁止,历史被篡改,甚至连思想也被控制。

这一切都是为了维持党派的统治,追求权力的最高目标。

通过描绘社会的恶劣环境和人民的绝望处境,乔治奥威尔希望呼吁人们警惕权力的滥用和对个体权利的侵犯。

《1984》不仅仅是一部描绘压迫社会的小说,而且还展现了乔治奥威尔对当时政治现实的思考和对未来社会走向的担忧。

他在小说中将党派描绘为一个凌驾于一切之上的存在,他们利用操纵人们的思想和言论来加强自己的统治。

乔治奥威尔警告人们,当权力变得无可限量时,可能会导致人民的剥夺和代表真理的消失。

《1984》的影响力不仅仅局限于文学领域,它深刻影响了政治、社会和哲学领域。

阅读这本小说可以让人思考权力的本质以及权力对个体和社会的影响。

乔治奥威尔通过他的笔触揭示了一个对自由思想和个人权利进行抗争的悲剧。

这部小说激起了读者对权力滥用和人类尊严的深思,也引发了对当代社会问题的讨论和反思。

乔治·奥威尔与阿尔杜斯·赫胥黎:两位反乌托邦小说家的对比分析简介乔治·奥威尔和阿尔杜斯·赫胥黎是20世纪的两位重要作家,他们以各自的反乌托邦小说《1984》和《美丽新世界》而闻名于世。

即使他们描述了不同的未来社会,但都揭示了人类潜在的威胁和社会问题。

这篇文章将对两位作家的思想、文学风格以及他们对现实社会的影响进行对比分析。

1. 思想观点1.1 乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell)乔治·奥威尔的思想主要集中在政治体制、权力滥用和个体自由方面。

他对极权主义和集权制度持批判态度,强调个人隐私和言论自由的重要性。

在《1984》中,奥威尔出色地描绘了一个极权主义政权下没有隐私、无处可逃避监视的恐怖世界。

1.2 阿尔杜斯·赫胥黎(Aldous Huxley)相比之下,阿尔杜斯·赫胥黎更关注科技发展和社会工程的影响。

他的《美丽新世界》揭示了一个以药物、娱乐和消费为主导的幸福虚无主义社会,并暗示科技可能剥夺人们的自由意志。

2. 文学风格2.1 乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell)奥威尔的文学风格坚定而直接,以清晰简明的语言传达出强烈的思想和情感。

他通过生动而具体的描写,使读者深入感受到悲壮和绝望。

奥威尔在《1984》中创造了许多深入人心、耐人寻味的形象和情节。

2.2 阿尔杜斯·赫胥黎(Aldous Huxley)与此相反,赫胥黎以幽默、戏剧性和诙谐为特点。

他善于使用夸张和讽刺手法揭示社会问题,并将科技幻想带入小说中。

他对未来社会进行了独特的构建,充满异国情调的元素进一步增加了小说的吸引力。

3. 对现实社会的影响3.1 乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell)《1984》成为一部具有指导意义的作品,揭示了政治操控、信息控制和权威主义对个人自由和隐私的威胁。

这本书深刻地影响了后来的政治研究和社会理论,并对当代社会问题产生了深远的影响。

George OrwellWhy I WriteFrom a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up I should be a writer. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.I was the middle child of three, but there was a gap of five years on either side, and I barely saw my father before I was eight. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays. I had the lonely child's habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life. Nevertheless the volume of serious — i.e. seriously intended — writing which I produced all through my childhood and boyhood would not amount to half a dozen pages.I wrote my first poem at the age of four or five, my mother taking it down to dictation. I cannot remember anything about it except that it was about a tiger and the tiger had ‘chair-like teeth’ — a good enough phrase, but I fancy the poem was a plagiarism of Blake's ‘Tiger, Tiger’. At eleven, when the war or 1914-18 broke out, I wrote a patriotic poem which was printed in the local newspaper, as was another, two years later, on the death of Kitchener. From time to time, when I was a bit older, I wrote bad and usually unfinished ‘nature poems’ in the Georgian style. I also attempted a short story which was a ghastly failure. That was the total of the would-be serious work that I actually set down on paper during all those years.However, throughout this time I did in a sense engage in literary activities. To begin with there was the made-to-order stuff which I produced quickly, easily and without much pleasure to myself. Apart from school work, I wrote vers d'occasion, semi-comic poems which I could turn out at what now seems to me astonishing speed — at fourteen I wrote a whole rhyming play, in imitation of Aristophanes, in about a week — and helped to edit a school magazines, both printed and in manuscript. These magazines were the most pitiful burlesque stuff that you could imagine, and I took far less trouble with them than I now would with the cheapest journalism. But side by side with all this, for fifteen years or more, I was carrying out a literary exercise of a quite different kind: this was the making up of a continuous ‘story’ about myself, a sort of diary existing only in the mind. I believe this is a common habit of children and adolescents. As a very small child I used to imagine that I was, say, Robin Hood, and picture myself as the hero of thrilling adventures, but quite soon my ‘story’ ceased to be narcissistic in a crude way and became more and more a mere description of what I was doing and the things I saw. For minutes at a time this kind of thing would be running through my head: ‘He pushed the door open and entered the room. A yellow beam of sunlight, filtering through the muslin curtains, slanted on to the table, where a match-box, half-open, lay beside the inkpot. With his right hand in his pocket he moved across to the window. Down in the street a tortoiseshell cat was chasing a dead leaf’, etc. etc. This habit continued until Iwas about twenty-five, right through my non-literary years. Although I had to search, and did search, for the right words, I seemed to be making this descriptive effort almost against my will, under a kind of compulsion from outside. The ‘story’ must, I suppose, have reflected th e styles of the various writers I admired at different ages, but so far as I remember it always had the same meticulous descriptive quality.When I was about sixteen I suddenly discovered the joy of mere words, i.e. the sounds and associations of words. The lines from Paradise Lost —So hee with difficulty and labour hardMoved on: with difficulty and labour hee.which do not now seem to me so very wonderful, sent shivers down my backbone; and the spelling ‘hee’ for ‘he’ was an added pleasure. As for the ne ed to describe things, I knew all about it already. So it is clear what kind of books I wanted to write, in so far as I could be said to want to write books at that time. I wanted to write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their own sound. And in fact my first completed novel, Burmese Days, which I wrote when I was thirty but projected much earlier, is rather that kind of book.I give all this background information because I do not think one can assess a writer's motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject matter will be determined by the age he lives in — at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own — but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, in some perverse mood; but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write. Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered afterdeath, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen — in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish.After the age of about thirty they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all — and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble ina lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words andphrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.(iv) Political purpose. —Using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other peoples’ idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time. By nature —taking your ‘nature’ to be the state you have attained when you are first adult — I am a person in whom the first three motives would outweigh the fourth. In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer. First I spent five years in an unsuitable profession (the Indian Imperial Police, in Burma), and then I underwent poverty and the sense of failure. This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism: but these experiences were not enough to give me an accurate political orientation. Then came Hitler, the Spanish Civil War, etc. By the end of 1935 I had still failed to reach a firm decision. I remember a little poem that I wrote at that date, expressing my dilemma: A happy vicar I might have beenTwo hundred years agoTo preach upon eternal doomAnd watch my walnuts grow;But born, alas, in an evil time,I missed that pleasant haven,For the hair has grown on my upper lipAnd the clergy are all clean-shaven.And later still the times were good,We were so easy to please,We rocked our troubled thoughts to sleepOn the bosoms of the trees.All ignorant we dared to ownThe joys we now dissemble;The greenfinch on the apple boughCould make my enemies tremble.But girl's bellies and apricots,Roach in a shaded stream,Horses, ducks in flight at dawn,All these are a dream.It is forbidden to dream again;We maim our joys or hide them:Horses are made of chromium steelAnd little fat men shall ride them.I am the worm who never turned,The eunuch without a harem;Between the priest and the commissarI walk like Eugene Aram;And the commissar is telling my fortuneWhile the radio plays,But the priest has promised an Austin Seven,For Duggie always pays.I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls,And woke to find it true;I wasn't born for an age like this;Was Smith? Was Jones? Were you?The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. Everyone writes of them in one guise or another. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows. And the more one is conscious of one's political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one's aesthetic and intellectual integrity.What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to wr ite a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art’. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article, if it were not also an aesthetic experience. Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.It is not easy. It raises problems of construction and of language, and it raises in a new way the problem of truthfulness. Let me give just one example of the cruder kind of difficulty that arises. My book about the Spanish civil war, Homage to Catalonia, is of course a frankly political book, but in the main it is written with a certain detachment and regard for form. I did try very hard in it to tell the whole truth without violating my literary instincts. But among other things it contains a long chapter, full of newspaper quotations and the like, defending the Trotskyists who were accused of plotting with Franco. Clearly such a chapter, which after a year or two would lose its interest for any ordinary reader, must ruin the book. A critic whom I respect read me a lecture ab out it. ‘Why did you put in all that stuff?’ he said. ‘You've turned what might have been a good book into journalism.’ What he said was true, but I could not have done otherwise. I happened to know, what very few people in England had been allowed to know, that innocent men were being falsely accused. If I had not been angry about that I should never have written the book.In one form or another this problem comes up again. The problem of language is subtler and would take too long to discuss. I will only say that of late years I have tried to write lesspicturesquely and more exactly. In any case I find that by the time you have perfected any style of writing, you have always outgrown it. Animal Farm was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole. I have not written a novel for seven years, but I hope to write another fairly soon. It is bound to be a failure, every book is a failure, but I do know with some clarity what kind of book I want to write. Looking back through the last page or two, I see that I have made it appear as though my motives in writing were wholly public-spirited. I don't want to leave that as the final impression. All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand. For all one knows that demon is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one's own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.1946。

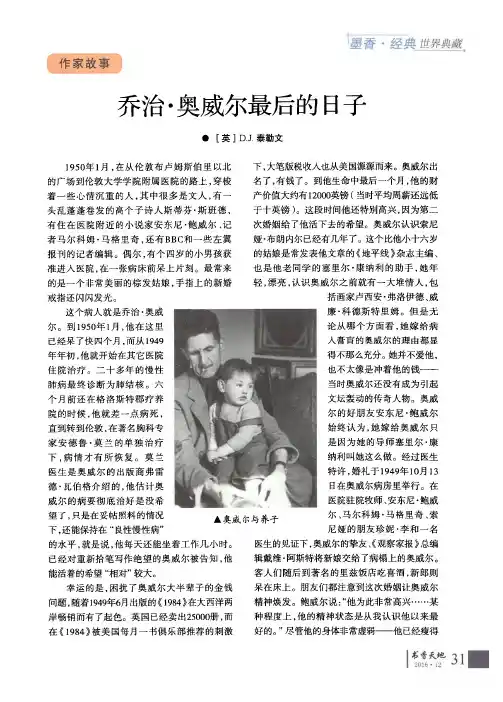

作者简介乔治·奥威尔《动物庄园》作者乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell)是英国人,本名埃里克·亚瑟·布莱尔(Eric Arthur Blair)。

1903年生于印度,当时,他的父亲在当地的殖民地政府供职,用他自己的话说,他家属于“中产阶级的下层,或没有钱财的中产家庭”。

1904年,由母亲带他先回到了英国。

1907年他举家迁回到英格兰。

他自幼天资聪颖,11岁时就在报纸上发表了一篇诗作《醒来吧,英格兰的小伙子们》。

14岁又考入著名的伊顿(Eton)公学,并获取了奖学金。

但早在小学时期,他就饱尝了被富家子弟歧视的苦涩,从他后来的回顾中可以看出,凭他那天生就很敏感的心灵,这时已经对不平等有了初步的体验。

1921年,布莱尔从伊顿毕业后考取了公职,到缅甸当了一名帝国警察,在那里,被奴役的殖民地人民的悲惨生活无时不在刺激着他的良知。

看着他们在饥寒交迫中、在任人宰割的被奴役中挣扎,他深深感到“帝国主义是一种暴虐”。

身为一名帝国警察,他为此在良心上备受煎熬,遂于1927年辞了职,并在后来写下了《绞刑》(A Hangin g,1931年),《缅甸岁月》(Burmes e Days,1934年)和《猎象记》(Shooti ng an Elepha nt,1936年),这些纪实性作品,对帝国主义的罪恶作了无情的揭露。

但是,这一段生活经历仍使布莱尔内疚不已。

为了用行动来表示忏悔,也为了自我教育,他从1928年1月回国时起,就深入到社会最底层,四处漂泊流落。

尽管他自幼就体弱多病,但在巴黎、伦敦两地,他当过洗盘子的杂工,住过贫民窟,并常常混迹在流浪汉和乞丐之中。

次年,布莱尔写下了关于这段经历的纪实and London,1933年),性作品《巴黎伦敦落魄记》(Down and Out in Paris真切地描述了生活在社会底层的人民的苦难。

乔治奥威尔英国作家和社会评论家乔治奥威尔(George Orwell)是20世纪英国最具影响力的作家和社会评论家之一。

他的作品以深刻的思想和对社会现象的批判而闻名,他的文字经过精心的组织和表达,一直吸引着读者的关注。

本文将介绍乔治奥威尔的生平和主要作品,探讨他对社会的观察和评论,以及他对言论自由和政治权力的思考。

乔治奥威尔于1903年出生在英国印度,他的原名是埃里克·亚瑟·布莱尔(Eric Arthur Blair)。

他在英国上学并加入了印度帝国警察,但他很快感到对殖民主义和不公平的愤怒,于是辞去警察工作,成为一名作家。

乔治奥威尔以笔名乔治奥威尔活动,以避免与他的家庭联系,并且这个名字后来也成为他在文坛的代表作。

在乔治奥威尔的作品中,最著名的是他的两部小说,《1984》和《动物庄园》。

《1984》描述了一个极权主义的社会,在这个社会中,政府通过监控和控制来剥夺人们的自由。

这本小说影响了后来的许多作品,并且引发了对政府权力的思考和对个人自由的捍卫。

《动物庄园》则以动物的立场揭示了社会等级和统治阶级的不公平,是对苏联共产主义政权的讽刺和批评。

乔治奥威尔的作品常常以幽默和讽刺的方式揭示社会问题,并且他的文字流畅清晰,言简意赅。

他对政治和社会现象的观察敏锐,他的作品准确地捕捉到了当时英国社会的缺陷和腐败。

他的写作风格简洁明了,富有洞察力,这使得他的作品不仅在当时引起了广泛的关注和辩论,而且至今仍然有很大的影响力。

除了小说以外,乔治奥威尔还写了一些政治和社会评论的文章和散文。

他的文章经常涉及一些热门问题,如言论自由、媒体操控和政府腐败等。

他对这些问题的讨论深入透彻,他的观点引起了读者的共鸣和讨论。

他的文章具有启发性和批判性,激励着人们思考社会问题,并寻求解决的途径。

言论自由是乔治奥威尔一直关注的话题。

他认为,言论自由是民主社会的基石,人们应该有权利自由地表达意见和批评政府。

他对政府操控媒体和审查言论的做法表示强烈反对,认为这种做法是对人权的侵犯。

乔治·奥威尔

乔治·奥威尔

姓名:乔治·奥威尔

原名:埃里克阿瑟布莱尔

性别:男

出生年月:1903年

国籍:印度

乔治·奥威尔原名埃里克阿瑟布莱尔(eric arthur blair),1903年生于印度。

1907年他举家迁回到英格兰。

1917年,他进入伊顿公学。

1921年后来到缅甸加入indian imperial police,1928年辞职。

随后的日子里他贫病交加,此间他当过、书店店员,直到1940年,他成为new english weekly的小说评论员,他才有了稳定的收入养家糊口。

1936年间,他访问了兰开夏郡和约克郡,1936年底,他来到西班牙参加西班牙内战,其间他受伤。

二战期间(1940-1943),他为bbs eastern service工作,并在此间写了大量政治和文学评论。

1945年起他成为observer的战地记者和machester evening news的固定撰稿人。

1945年,他出版了《动物农场》,1949年出版了《1984》。

奥威尔患有肺结核,于1950年死去。

乔治·奥威尔

乔治·奥威尔

姓名:乔治·奥威尔

原名:埃里克阿瑟布莱尔

性别:男

出生年月:1903年

国籍:印度

乔治·奥威尔原名埃里克阿瑟布莱尔(eric arthur blair),1903年生于印度。

1907年他举家迁回到英格兰。

1917年,他进入伊顿公学。

1921年后来到缅甸加入indian imperial police,1928年辞职。

随后的日子里他贫病交加,此间他当过、书店店员,直到1940年,他成为new english weekly的小说评论员,他才有了稳定的收入养家糊口。

1936年间,他访问了兰开夏郡和约克郡,1936年底,他来到西班牙参加西班牙内战,其间他受伤。

二战期间(1940-1943),他为bbs eastern service工作,并在此间写了大量政治和文学评论。

1945年起他成为observer的战地记者和machester evening news的固定撰稿人。

1945年,他出版了《动物农场》,1949年出版了《1984》。

奥威尔患有肺结核,于1950年死去。