本科 毕业设计 城市规划专业 外文翻译 终结版

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:168.63 KB

- 文档页数:11

城市与建筑专业英语期末翻译作业学号:090870244姓名:张奎班级:城规091班老师:杜德静Chapter eight : Urban GovernanceFurther Reading (1)Impact of Globalization on Urban Governance在过去的二十年里,许多领域出现了重组过程。

世界各地的城市已经在经济、技术、政治、文化和空间上有了重大的变化。

经济变化已经形成了一个新的全球化经济,同时粗放生产也向灵活的专业化生产转变。

国际贸易和投资也有大幅度提升。

世界重组经济刺激了向新的全球经济过渡。

因此,金融对生产的优势地位一直在增加的同时,更突出强调知识、创新和经济竞争。

另一方面,信息技术已经在城市地区改变了经济、社会和制度结构。

社会和文化变化的发生,导致社会如隔离和分裂等重大变化。

向全球化经济的过渡导致了国家经济失去对自身金融市场的控制。

制度的转变导致减少了政府在经济和社会中的积极作用。

决策分布在广泛的组织中,而不能仅局限于当地政府。

因此,政府间的关系也进行了重组。

自80年代以来,研究了在全球化政策治理关系上的影响。

虽然没有在治理的定义上达成共识,那确实显示出正式的政府结构和现代机构的角色转变,以及在公共,私人,自愿和家庭群体之间的责仸分配的变化。

增加分散在城市舞台上的责仸,在现有的国家和地方各级机构的政策制定过程中重点已转移到新机构的关系和不同的成分上。

这种分裂的影响也反映在经济和空间规划上。

一个新的政治形式,已成为一个国家重点调整的对象。

以网络的形式,治理跨越了大陆,国家,区域和地方政府之间的关系。

经济和体制因素的相互作用决定着城市和地区的多变性政府结构,而这将通过过政治,文化和其他内容的力量表现出来在这个过程中,城市収展和城市政策之间的关系变得更加复杂。

然而到目前为止,一个满意的城市治理模式,可以充分代表所有案件尚未开収。

有很多不同的方法来定义“治理”。

在很多学术领域这个词有其理论根基,其中包括制度经济学、国际关系、収展研究,政治科学和公共管理。

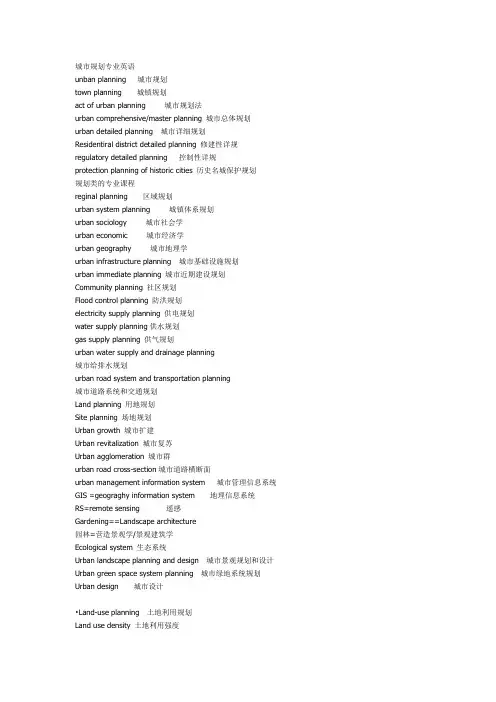

城市规划专业英语unban planning 城市规划town planning 城镇规划act of urban planning 城市规划法urban comprehensive/master planning 城市总体规划urban detailed planning 城市详细规划Residentiral district detailed planning 修建性详规regulatory detailed planning 控制性详规protection planning of historic cities 历史名城保护规划规划类的专业课程reginal planning 区域规划urban system planning 城镇体系规划urban sociology 城市社会学urban economic 城市经济学urban geography 城市地理学urban infrastructure planning 城市基础设施规划urban immediate planning 城市近期建设规划Community planning 社区规划Flood control planning 防洪规划electricity supply planning 供电规划water supply planning供水规划gas supply planning 供气规划urban water supply and drainage planning城市给排水规划urban road system and transportation planning城市道路系统和交通规划Land planning 用地规划Site planning 场地规划Urban growth 城市扩建Urban revitalization 城市复苏Urban agglomeration 城市群urban road cross-section城市道路横断面urban management information system 城市管理信息系统GIS =geograghy information system 地理信息系统RS=remote sensing 遥感Gardening==Landscape architecture园林=营造景观学/景观建筑学Ecological system 生态系统Urban landscape planning and design 城市景观规划和设计Urban green space system planning 城市绿地系统规划Urban design 城市设计•Land-use planning 土地利用规划Land use density 土地利用强度Building interval 建筑间距Urban sub-center 城市副中心The cultural and historic planning 历史文化名城Protection planning 保护规划Urbanization 城市化Urbanization level 城市化水平Suburbanization 郊区化Public participation 公众参与Sustainable development 可持续性发展Urban sustainable development 城市可持续发展Over-all urban layout 城市整体布局Pedestrian crossing 人行横道Human scale 人体尺寸Street furniture 街道小品Street tree 行道树Fountain 喷泉Public park/garden 公园History of gardening 造园史sculpture 雕塑planning design 种植设计plant 乔木shrub 灌木landscape designer 景观设计师mini-park/pocket park 袖珍公园urban landmark 城市地标Nature reserve 自然保护区Landscape characteristic 园林特色tea bar 茶吧Traffic and parking 交通与停车Landscape node 景观节点Landscape core 景观核Landscape bond 景观带•Brief history of urban planning Archaeological 考古学的Habitat 住处Aesthetics 美学Geometrical 几何学的Floor area ratio 容积率Greening rate 绿地率Population density 人口密度Legend 图例Scale 比例尺Traffic flow density 交通流密度Boundary line of roads 道路红线Topography map 地形图Moat/cannel 护城河Green buffer 防护绿地Wetland 湿地Vegetation 植被Indoor plants 室内植物Buffer zone 缓冲区Vehicles 车辆,交通工具mechanization 机械化merchant-trader 商人阶级urban elements 城市要素proposed plaza 拟建广场plazas 广场malls (原意)林荫道•The city and regionAdaptable 适应性强的Organic entity 有机体Department stores 百货商店Opera 歌剧院Symphony 交响乐团Cathedrals 教堂Density 密度Circulation 循环Elimination of water 水处理措施In three dimensional form 三维的Condemn 谴责Rural area 农村地区Regional planning agencies 区域规划机构Service-oriented 以服务为宗旨的Frame of reference 参考标准Distribute 分类Water area 水域Alteration 变更Inhabitants 居民Motorway 高速公路Update 改造论文写作Abstract 摘要Key words 关键词Reference 参考资料•Urban problemDimension 大小Descendant 子孙,后代Luxury 奢侈Dwelling 住所Edifices 建筑群<Athens Charter>雅典宪章Residence 居住Employment 工作Recreation 休憩Transportation交通Swallow 吞咽,燕子Urban fringes 城市边缘Anti- 前缀,反对……的;如:antinuclear反核的anticlockwise逆时针的Pro- 前缀,支持,同意……的;如:pro-American 亲美的pro-education重教育的Grant 助学金,基金Sewage 污水Sewer 污水管Sewage treatment plant 污水处理厂Brain drain 人才流失Drainage area 汇水面积Traffic flow 交通量Traffic concentration 交通密度Traffic control 交通管制Traffic bottleneck 交通瓶颈地段Traffic island 交通岛(转盘)Traffic point city 交通枢纽城市Train-make-up 编组站Urban redevelopment 旧城改造Urban revitalization 城市复苏•Urban FunctionUrban fabric 城市结构Urban form 城市形体Urban function orientation 城市功能定位Urban characteristic 城市特征Designated function of city 城市性质Traffic point city 交通枢纽城市Warehouse 仓库Material processing center 原料加工中心Religious edifices 宗教建筑Correctional institution 教养院Transportation interface 交通分界面CBD=central business district 城市中心商业区Public agencies of parking 停车公共管理机构Energy conservation 节能Individual building 单一建筑Mega-structures 大型建筑Mega- 大,百万,强Megalopolis 特大城市Megaton 百万吨R residence land use 居住用地黄色C commercial land use 商业用地红色M manufacture land use/industrial land use 工业用地紫褐色W warehouse land use 仓储用地紫色T transportation 交通用地蓝灰色Inter-city transportation land use 对外交通用地S roads and squares land use 道路广场用地留白处理U municipal utilities land use 市政公共设施用地接近蓝灰色G green space 绿地绿色P particular/specially-designated land use特殊用地E 水域及其他用地(除E外,其他合为城市建设用地)Corporate 公司的,法人的Corporation 公司企业Accessibility 可达性;易接近Service radius 服务半径Reservation of open space 预留公共空间•Urban landscapeTopography 地形图Well-matched 相匹配Ill-matchedVisual landscape 视觉景观Visual environment 视觉环境Visual landscape capacity 视觉景观容量Tour industry 旅游业Service industry 服务业Relief road 辅助道路Rural population 城镇居民Roofline 屋顶轮廓线风景园林四大要素:landscape plantArchitecture/buildingTopographyWater•Urban designNature reserve 自然保护区Civic enterprise 市政企业Artery 动脉,干道,大道Land developer 土地开发商Broad thorough-fare 主干道•Water supply and drainageA water supply for a town 城市给水系统Storage reservoir 水库,蓄水库Distribution reservoir 水库,配水库Distribution pipes 配水管网Water engineer 给水工程师Distribution system 配水系统Catchment area 汇水面积Open channel 明渠Sewerage system 污水系统,排污体制Separate 分流制Combined 合流制Rainfall 降水Domestic waste 生活污水Industrical waste 工业污水Stream flow 河流流量Runoff 径流Treatment plant 处理厂Sub-main 次干管Branch sewer 支管City water department 城市供水部门•UrbanizationSpatial structure 空间转移Labor force 劳动力Renewable 可再生Biosphere 生物圈Planned citiesBlueprints 蓝图License 执照,许可证Minerals 矿物Hydroelectric power source 水利资源Monuments 纪念物High-rise apartment 高层建筑物Lawn 草坪Soft landscape 软质景观Hard landscape 硬质景观Urban amenity 城市宜人设施Regional park 区域性公园Pavement 铺装Sidewalk 人行道Avenue 林荫道Winding street/wandering road 曲折的路Flower bed 花坛Hedge 树篱Green fencing 绿篱Riverside landscape bond 滨河景观带Palm 棕榈Recreation center 游憩中心Arched corridor 拱廊Multilayer planting 多层植物配置Riverside park 滨河公园Bank line 岸线Athletics park 运动公园Yacht 游艇Landscape bond around the city 环城景观带Central landscape bond 中央景观带Brook 小溪Front yard 前院Small-bounding wall小围墙Liana 藤本植物Plant configuring 植物配置Ever-green 常绿Hardwoods 阔叶林Ground cover 地被植物Oasis 绿洲Sub-space 亚空间Secondary seating 辅助性休息设施Mounds of grass 草丘Step with a view 眺台Seating wall 坐墙Seating capacity 座椅容量Planter 种植池Dramatic grade change 剧烈的坡度变化Eye-catching feature 引人注目的景物Drinking fountain 饮水设备Trash container 垃圾桶Reception/information 询问处Sign system 标志系统•A view of VeniceMetropolis 都市Urban renewal 城市更新Urban redevelopment 城市改造Construction work 市政建设Slums 平民窟Alleys 大街小巷Populate 居住Gothic 哥特式Renaissance 文艺复兴式Baroque 巴洛克式。

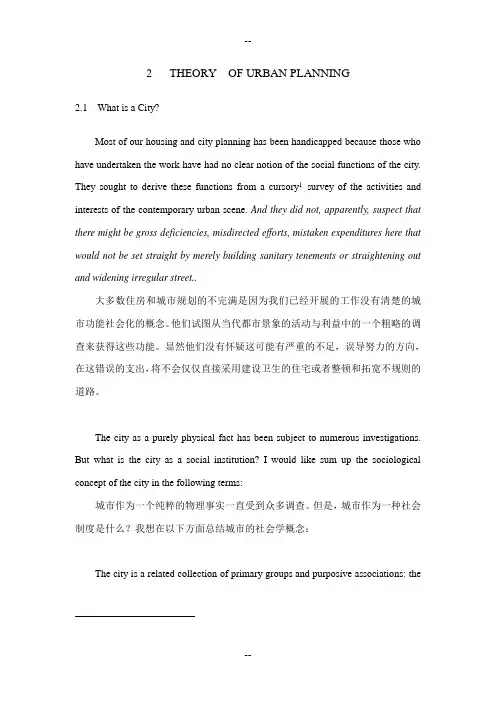

2 THEORY OF URBAN PLANNING2.1 What is a City?Most of our housing and city planning has been handicapped because those who have undertaken the work have had no clear notion of the social functions of the city. They sought to derive these functions from a cursory1survey of the activities and interests of the contemporary urban scene. And they did not, apparently, suspect that there might be gross deficiencies, misdirected efforts, mistaken expenditures here that would not be set straight by merely building sanitary tenements or straightening out and widening irregular street..大多数住房和城市规划的不完满是因为我们已经开展的工作没有清楚的城市功能社会化的概念。

他们试图从当代都市景象的活动与利益中的一个粗略的调查来获得这些功能。

显然他们没有怀疑这可能有严重的不足,误导努力的方向,在这错误的支出,将不会仅仅直接采用建设卫生的住宅或者整顿和拓宽不规则的道路。

The city as a purely physical fact has been subject to numerous investigations. But what is the city as a social institution? I would like sum up the sociological concept of the city in the following terms:城市作为一个纯粹的物理事实一直受到众多调查。

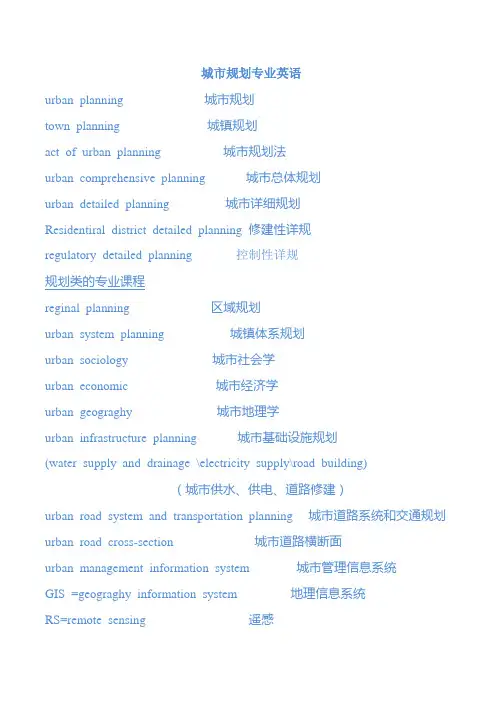

城市规划专业英语urban planning 城市规划town planning 城镇规划act of urban planning 城市规划法urban comprehensive planning 城市总体规划urban detailed planning 城市详细规划Residentiral district detailed planning 修建性详规regulatory detailed planning 控制性详规规划类的专业课程reginal planning 区域规划urban system planning 城镇体系规划urban sociology 城市社会学urban economic 城市经济学urban geograghy 城市地理学urban infrastructure planning 城市基础设施规划(water supply and drainage \electricity supply\road building)(城市供水、供电、道路修建)urban road system and transportation planning 城市道路系统和交通规划urban road cross-section 城市道路横断面urban management information system 城市管理信息系统GIS =geograghy information system 地理信息系统RS=remote sensing 遥感Gardening==Landscape architecture 园林=营造景观学Urban landscape planning and design 城市景观规划和设计Urban green space system planning 城市绿地系统规划Urban design 城市设计Land-use planning 土地利用规划The cultural and historic planning 历史文化名城Protection planning 保护规划Urbanization 城市化Suburbanization 郊区化Public participation 公众参与Sustainable development(sustainability) 可持续性发展(可持续性)Over-all urban layout 城市整体布局Pedestrian crossing 人行横道Human scale 人体尺寸Street furniture 街道小品(sculpture fountain tea bar) (雕塑、喷泉、茶吧)Traffic and parking 交通与停车Landscape node 景观节点Archaeological 考古学的Habitat 住处Aesthetics 美学Geometrical 几何学的Moat 护城河Vehicles 车辆,交通工具,mechanization 机械化merchant-trader 商人阶级urban elements 城市要素plazas 广场malls 林荫道The city and regionAdaptable 适应性强的Organic entity 有机体Department stores 百货商店Opera 歌剧院Symphony 交响乐团Cathedrals 教堂Density 密度Circulation 循环Elimination of water 水处理措施In three dimensional form 三维的Condemn 谴责Rural area 农村地区Regional planning agencies 区域规划机构Service-oriented 以服务为宗旨的Frame of reference 参考标准Distribute 分类Water area 水域Alteration 变更Inhabitants 居民Motorway 高速公路Update 改造论文写作Abstract 摘要Key words 关键词Reference 参考资料Urban problemDimension 大小Descendant 子孙,后代Luxury 奢侈Dwelling 住所Edifices 建筑群<Athens Charter>雅典宪章Residence 居住Employment 工作Recreation 休憩Transportation交通Swallow 吞咽,燕子Urban fringes 城市边缘Anti- 前缀,反对……的;如:antinuclear反核的anticlockwise逆时针的Pro- 前缀,支持,同意……的;如:pro-American 亲美的pro-education 重教育的Grant 助学金,基金Sewage 污水Sewer 污水管Sewage treatment plant 污水处理厂Brain drain 人才流失Drainage area 汇水面积Traffic flow 交通量Traffic concentration 交通密度Traffic control 交通管制Traffic bottleneck 交通瓶颈地段Traffic island 交通岛(转盘)Traffic point city 交通枢纽城市Train-make-up 编组站Urban redevelopment 旧城改造Urban revitalization 城市复苏Urban FunctionUrban fabric 城市结构Urban form 城市形体Warehouse 仓库Material processing center 原料加工中心Religious edifices 宗教建筑Correctional institution 教养院Transportation interface 交通分界面CBD=central business district 城市中心商业区Public agencies of parking 停车公共管理机构Energy conservation 节能Individual building 单一建筑Mega-structures 大型建筑Mega- 大,百万,强Megalopolis 特大城市Megaton 百万吨R residence 居住用地黄色C commercial 商业用地红色M manufacture 工业用地紫褐色W warehouse 仓储用地紫色T transportation 交通用地蓝灰色S square 道路广场用地留白处理U utilities 市政公共设施用地接近蓝灰色G green space 绿地绿色P particular 特殊用地E 水域及其他用地(除E外,其他合为城市建设用地)Corporate 公司的,法人的Corporation 公司企业Accessibility 可达性;易接近Service radius 服务半径Urban landscapeTopography 地形图Well-matched 相匹配Ill-matchedVisual landscape 视觉景观Visual environment 视觉环境Visual landscape capacity 视觉景观容量Tour industry 旅游业Service industry 服务业Relief road 辅助道路Rural population 城镇居民Roofline 屋顶轮廓线风景园林四大要素:landscape plantarchitecture/buildingtopographywaterUrban designNature reserve 自然保护区Civic enterprise 市政企业Artery 动脉,干道,大道Land developer 土地开发商Broad thorough-fare 主干道Water supply and drainageA water supply for a town 城市给水系统Storage reservoir 水库,蓄水库Distribution reservoir 水库,配水库Distribution pipes 配水管网Water engineer 给水工程师Distribution system 配水系统Catchment area 汇水面积Open channel 明渠Sewerage system 污水系统,排污体制Separate 分流制Combined 合流制Rainfall 降水Domestic waste 生活污水Industrical waste 工业污水Stream flow 河流流量Runoff 径流Treatment plant 处理厂Sub-main 次干管Branch sewer 支管City water department 城市供水部门UrbanizationSpatial structure 空间转移Labor force 劳动力Renewable 可再生*Biosphere 生物圈Planned citiesBlueprints 蓝图License 执照,许可证Minerals 矿物Hydroelectric power source 水利资源Monuments 纪念物High-rise apartment 高层建筑物Lawn 草地Pavement 人行道Sidewalk 人行道Winding street 曲折的路A view of Venice Metropolis 都市Construction work 市政建设Slums 平民窟Alleys 大街小巷Populate 居住Gothic 哥特式Renaissance 文艺复兴式Baroque 巴洛克式。

学校代码:学号:本科毕业设计说明书(外文文献翻译)学生姓名:学院:建筑学院系别:城市规划系专业:城市规划专业班级:指导老师:二〇一三年六月外文文献1题目:城市的共同点简要说明:美国是一个幅员辽阔的大陆规模的国家,国土面积大,增加人口或国内生产总值明显。

美国的趋势,乡村的经济发展的时候,例如考虑如何美国新城市规划的已经席卷英国,特别是在约翰·普雷斯科特满腔热情地通过了。

现在,在欧洲,我们有一个运动自愿自下而上的地方当局联合会,西米德兰兹或大曼彻斯特地区的城市,这意味着当地政府的重新组织。

因此,在大西洋两侧的,这可能是一个虚假的黎明。

这当然是一个看起来不成熟的凌乱与现有的正式的政府想违背的机构。

但是,也许这是一个新的后现代的风格,像我们这样的社会管理自己的事务的征兆。

有趣的是,在法国和德国的类似举措也一起萌生,它们可以代表重大的东西的开端。

出处:选自国外刊物《城市和乡村规划》中的一篇名为《城市的共同点》的文章。

其作者为霍尔·彼得。

原文:That long-rehearsed notion of American exceptionlism tends to recur whenever yo u seriously engage withevents in that country. For one thing, the United States is a vast continental-scale country--far larger in area, although not of course inopulation or GDP, than our European Union, let alone our tiny island or the even tinier strip of denselyrbanised territory that runs from the Sussex Coast to the M62. For another--an associated (but too oftengnored)thing--the United States has a federal system of government, meaning that your life (and even, if youappen to be a murderer, your death) is almost totally dependent on the politics of your own often-obscure Stateapitol, rather than on those of far-distant Washington, DC.And, stemming from those two facts, America is an immensely Iocalised and even islatednation. Particularlyif you happen to live in any of the 30 or so states that form its deep interior heartland, from an Americanvantage point the world--even Washington, let alone Europe or China--really is a very long way away.Although no-one seems exactly to know, it appears that an amazingly small number of Americans have apassport: maybe one in five at most. And since I was reliably told on my recent visit that many Americans thinkthey need one to visit Hawaii, it's a fair bet that even fewer have ever truly ventured abroad.That thought recurred repeatedly on the flight back, when in the airport bookstall I picked up a best-sellingpiece of the higher journalism in which America excels, What's the Matter with Kansas?, by Thomas Frank. Anative of Kansas, Frank poses the question: why in 2000 (and again in 2004) did George W. Bush sweep somuch of his home state--as of most of the 'red America' heartland states--when the people who voted for himwere voting for their own economic annihilation? For Frank convincingly shows that they were denying theirown basic self-interests--sometimes to the degree that they were helping to throw themselves out of work.The strange answer is that in 21st-century America, the neo-conservatives have succeeded in fighting electionson non-economic, so-called moral issues--like abortion, or the teaching of intelligent design in the publicschools. And the people at the bottom of the economic pile are the most likely to vote that way.Well, we're a long way behind that curve--or ahead of it, you might say. But American trends, howeverimplausible at the time, have an alarming way of arriving in the UK one or two decades later (just look at trashTV). Who knows? Maybe by 2016, orearlier, our own home-grown anti-evolutionists will be busily engaged inmass TV burnings of 10 [pounds sterling] notes--assuming of course that by then the portrait of Darwin hasn't been replaced by a Euro-bridge. Meanwhile, vive la difference.Yet, despite such fundamental divides, the interesting fact is that in academic or professional life the intellectualcurrents and waves tend to respect no frontiers. Considerfor instance how the American New Urbanismmovement has swept the UK, particularly after John Prescott so enthusiastically adopted it and made it aLeitmotif of his Urban Summit a year ago. And now, as Mike Teitz shows in his piece in this issue of Town&Country Planning, there's yet another remarkable development: apparently in complete independence, acityregionmovement is spring up over there, uncannily similar in some ways to what's happening here.Just compare some parallels.Here, we had metropolitan counties from 1973, when a Tory government created them, to 1986, when a Torygovernment abolished them. There, they had a movement for regional 'councils of governments'--but they wereweak and unpopular, and effectively faded away.Now, we have a movement for city-regions as voluntary bottom-up federations of local authorities in certainareas, like the West Midlands or Greater Manchester, but without any suggestion that this means localgovernment re-organisation. And there, they have what Mike Teitz calls regionalism by stealth: in California'slarger metropolitan areas, such as Los Angeles or the San Francisco Bay Area, there is a new movement thatmakes no attempt to create new regional agencies, but instead uses any convenient existing agency in order toinvolve local governments closely in updating their land use plans to reflect regional goals.There's one significant feature of the Californian model that maybe has no parallel on this side: it usesincentives, such as the availability of federal transportation improvement funds, to win local collaboration. Butina sense, you could argue that a major new initiative from our Department for Transport—regionalprioritysation, whereby the new regional planning bodies set their own priorities for investment--could work inthe same way: these bodies, all of which are producing new-style regional spatial strategies, are now having torelate these to their planned investments in roads or public transport.Of course, there are huge differences. First, ours is a typical top-down initiative, a kind of downward devolutionby order of Whitehall, and it remains unclear whether Whitehall won't after all second-guess the regionalpriorities, as with the 260 million [pounds sterling] Manchester Metrolink extensions which form a huge chunkof the North West priority list but which have already been rejected by Alistair Darling. And second,theexercise is being performed by regional strategic planning bodies that operate at a much larger spatial scale thanthe city-regions: the North West, for instance, contains no less than three such city-regions as defined in theNorthern Way strategy--or three somewhat different city-regions (plus one other) as defined in a new report forOffice of the Deputy Prime Minister from the Universities of Salford and Manchester, AFramework for CityRegions.Nonetheless, it's precisely since John Prescott's failed attempt to give such bodies democratic legitimacy, in theNorth East referendum, that the city-regionidea hassurfaced--clearly as an alternative to it. It's not entirely outof the question, although it would be exceedingly messy, to conceive of a new city-regional structure carved outof the present regional structure.So, on either side of the Atlantic, this may be a false dawn. It's certainly one that looks inchoate, untidy and atodds with existing formal structures of government. But perhaps that's symptomatic of a new postmodern (orpost-postmodern) style by which societies like ours run their affairs. Interestingly, similarinitiativesareemerging in France and Germany. Together, they could represent the beginnings of something significant.Sir Peter Hall is Professor of Planning and Regeneration in the Bartlett School of Planning, University CollegeLondon, and President of the TCPA. The views expressed here are his own.翻译内容:城市的共同点霍尔·彼得每当认真参与并研究这个国家的大事时长期存在的美国例外论就会反复出现在脑海里。

城市规划专业英语翻译.CHAPTER ONE: EVOLUTION AND TRENDSARTICLE: The Evolution of Modern Urban Planningto definition It's very difficult to give aplanning, modern urban planning isfrom origin to today, modern urbanmore like an evolving and changing process, and it will continue evolving and changing. Originally, modernurban planning was emerged to resolve the problems brought by Industrial Revolution; it was physical andfor land-use. development political and technical Then with the economic, social, technical with focus onone hundred years, today's city is a complex system which contains many elements that are related to overeach other. And urban planning is not only required to concern with the build environment, but also relate从起源到今more to economic, social and political conditions.以现代城市规划,这是非常困难的给予定义,现代城市规划的出现,天,现代城市规划更像是一个不断发展和变化的过程,它会继续发展和变化。

大学生城市规划英语作文As a college student majoring in urban planning, I am fascinated by the dynamic and ever-changing nature of cities. The built environment, transportation systems, and public spaces all play a crucial role in shaping the identity and functionality of a city.Urban planning is not just about designing physical spaces, but also about creating communities and fostering social interactions. It involves understanding the needs and desires of diverse populations and finding ways to accommodate them within the urban fabric.One of the biggest challenges in urban planning is achieving sustainable development. This requires balancing economic growth with environmental conservation and social equity. It involves promoting green spaces, reducing carbon emissions, and ensuring access to basic amenities for all residents.Technology is revolutionizing the field of urban planning. From geographic information systems to smart city solutions, digital tools are helping planners analyze data, visualize scenarios, and engage with stakeholders in more effective ways.Public participation is essential in the urban planning process. Engaging with local residents, businesses, and community organizations can help ensure that planning decisions reflect the needs and aspirations of the people who will be directly impacted by them.In conclusion, urban planning is a complex and multifaceted discipline that requires a deep understanding of social, economic, and environmental dynamics. As a college student, I am excited to be part of a profession that has the potential to shape the future of our citiesfor the better.。

单词:Urban form 城市形态Individual buildings 单体建筑Open spaces 开敞空间Sense of belonging 归属感Cityscape 城市景观developing landscape policies 发展景观规划green space system 绿色空间系统landscape framework 景观框架Climate change and the greenhouse effect (气候变化和温室效应)Wastewater treatment (废水处理)Low-carbon economy 低碳经济段落:1.From a a visual visual and aesthetic aesthetic perspective, perspective, perspective, Lynch, Lynch, in his book The Image Image of of of the the the City City (1960), identified five types of elements. They are: (1) Paths, which may be streets, walkways, transit lines, canals, railroads ¼(2) Edges, which include shores, railroad cuts, edges of development, walls ¼(3) Districts, which are recognizable with same common character. (4) Nodes, which may be centers of activities, like a shopping center, major junctions[a1] , places of break in transportation ¼(5) Landmarks, which are usually a rather defined physical object such as building, sign, mountain or monument. 翻译:从视觉和美学的角度来看,凯文林奇在他的著作《城市意象》中,定义了5种元素,它们是:(1)通道:是道路、人行道、车行道、水道,铁路等等;(2)边缘:包括河岸、铁路交叉口、开发区边缘、墙等;(3)区域,是具有相同性质的地区;4)节点:它也许是活动中心,像是商业中心、主要的交叉口、交通集散点等;(5)地标:它通常是一个明显的物质性的建筑物,像是大厦、标志物、山体或者纪念碑等。

A KNOWLEDGE-BASED CONCEPTUAL VISION OF THE SMART CITYElsa NEGRE Camille ROSENTHAL-SABROUX Mila GASCóLAMSADE LAMSADE Center for Innovation in CitiesParis-Dauphine University Paris-Dauphine University Institute for Innovation SIGECAD Team SIGECAD Team and Knowledge ManagementFrance France ESADE-Ramon Llull Universityelsa.negre@dauphine.frcamille.rosenthal-sabroux@dauphine.frmila.gasco@AbstractThe term smart city is a fuzzy concept, not well defined in theoretical researches nor in empirical projects. Several definitions, different from each other, have been proposed. However, all agree on the fact that a Smart City is an urban space that tends to improve the daily life (work, school,...) of its citizens(broadly defined). This is an improvement fromdifferent points of view: social, political, economic, governmental. This paper goes beyond this definition and proposes a knowledge-based conceptual vision of the smart city, centered on people’s information and knowledge of people, in order to improve decision-making processes and enhance the value-added of business processes of the modern city.1. IntroductionOver the past few decades, the challenges faced by municipal ,such as urban growth or migration, have become increasingly complex and interrelated. In addition to the traditional land-use regulation, urban maintenance, production, and management of services, governments are required to meet new demands from different actors regarding water supply, natural resources sustainability, education, safety, or transportation (Gascóet al,2014). Innovation, and technological innovation in particular, can help city governments to meet the challenges of urban governance, to improve urban environments, to become more competitive and to address sustainability concerns. Since the early 90s, the development of Internet and communication technologies has facilitated the generation of initiatives to create opportunities for communication and information sharing by local authorities. This phenomenon appeared in the United States then moved to Europe and Asia. Indeed, in oureveryday life, we are more and more invaded by data and information. This flow of data and information is often the result of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). Moreover, potentialities of ICT, that have almost exponentially increased have given rise to a huge mass of data to treat (Batty, 2013). The world is becoming increasingly digital and people are affected by these changes. Also, the digital infrastructure infers an information environment that is “as imperceptible to us as water is to a fish”(McLuhan & Gordon, 2011).There exists a kind of parallelism between technologies and humans. On one hand, people use technologies more and more and are hyperconnected, and, on the other hand, (numeric) systems are more and more user-centered (Viitanen &Kingston, 2014). Thus, within cities, systems have to adaptto hyper-connected citizens, in a very particular environment, the one of cities in constant evolution where systems and humans are nested. The advent of new technologies also confronts the city to a large influx of data (Big Data) from heterogeneous sources, including social networks. Itis also important to note that much information and /or knowledge flow between different people (with different uses and backgrounds) and between different stakeholders (Kennedy, 2012). In this respect, the city sees that numerous data circulate via the internet, wireless communication, mobile phones,…Finally, smart cities are exposed to technological issues tied to the huge mass of data which pass within them. These data can carry knowledge and, by the way, the smart city, and de facto, the smart city,aware of the existence and of the potential of this knowledge, can exploit and use them.Note that, for a city, all citizens become knowledgecitizens, especially those whose knowledge is the crucial factor enabling them to improve theirdecision-making processes. In this respect,knowledge is fundamentally valuable to make better decisions and to act accordingly.Given this context, this paper focuses on knowledge in the smart city. The paper discusses both explicit knowledge (knowledge extracted from data which flows within the city) and tacit knowledge(that is, citizen’s knowledge). Our argument is twofold:on one hand, we believe that, due to the importance for the city management of tacit knowledge, the city should be closer to its citizens(Bettencourt, 2013). On the other, a city can become smarter by improving its decision-making process and, therefore, by making better decisions. ICT can help in this respect: more data and better-managed data result in, not only more information, but also more knowledge. More knowledge gives rise to better decisions (Grundstein et al, 2003; Simon,1969).The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Next, we present some literature on smart cities and knowledge. Subsequently, we describe the opportunities and challenges smart cities offer for cities development and growth. The City’s Information and Knowledge System is then introduced. Finally, we bring to a close, drawing some conclusions on what a knowledge-based smart city is.2. Related Work2.1. On smart citiesThe origins of the smart city concept are related to the European Union’s energetic efficiency programs that aimed at making cities sustainable(AMETIC, 2013). However, important conceptual trends have also contributed to the emergence of this term. In particular, the influence of openinnovation has been key. Chesbrough (2006 & 2003) defines open innovation as a strategy by which firms commercialize external (as well as internal) ideas by deploying outside (as well as in-house) pathways to the market. In addition, “ideas can also originate outside the firm’s own labs and be brought inside for commercialization. In other words, the boundary between a firm and its surrounding environment is more porous, enabling innovation to move easily between the two”(Chesbrough, 2003: 37).Despite open innovation was born in relation to the industry and the business world, several authors think this theory can be easily implemented in different fields. In this respect, while historically the public sector has lagged on the innovation curve,today information technology is opening up new opportunities to transform governance and redefine government-citizen interactions, particularly within cities (Chan, 2013; Pyrozhenko, 2011; Almirall &Wareham, 2008). In this context, a smart city can be understood as an environment of open and userdriven innovation for experimenting and validating ICT-enabled services (Schaffers et al., 2011).A second relevant stream of theory that has contributed to the development of smart cities is urban planning and urban development (Trivellato etal., 2013). Ferro et al. (2013) state that the term smart city probably finds its roots in the late nineties with the smart growth movement calling for smart policies in urban planning. According to Anthopoulos & Vakali (2011), urban planning controls the development and the organization of a city by determining, among other, the urbanization zones and the land uses, the location of various public networks and communal spaces, the anticipation of the residential areas, and the rules for buildings constructions. Traditionally, urban planners have been concerned with designing the physical infrastructure of communities, such as transportation systems, business districts, parks and, housing development (Fernback, 2010). Currently, in doing so, urban planners find in technology an enormous opportunity to shape the future of a city (Townsend,2013), particularly for urban planning is a complextask requiring multidimensional urbaninformation, which needs to be shared and integrated(Wangetal.2007).Regardless of its origins, various attempts have been made to academically define and conceptually describe a smart city. AlAwadhi & Scholl (2013) state that, actually, these definitions depend on different types and groups of practitioners think about what a smart city is. In this respect, although no generally accepted academic definition has emerged so far, several works have identified certain urban attributes that maycharacterize what a smart city is.To start with, Giffinger et al. (2007) rank 70 European cities using six dimensions: smart economy (competitiveness), smart people (human and social capital), smart governance (participation), smart mobility (transport and ICT), smart environment(natural resources), and smart living (quality of life).As a result, they define a smart city as “a city well performing in a forward-looking way in these six characteristics, built on the ‘smart combination of endowments and activities of self-decisive,independent and aware citizens”(p. 11). Moreover, Nam & Pardo (2011) suggest three conceptual dimensions of a smart city: technology, people, and community. For them, technology is key because of the use of ICT to transform life and work within a city in significant and fundamental ways.However, a smart city cannot be built simp ly through the use of technology. That is why the role of human infrastructure, human capital and education, on one hand, and the support of government and policy, on the other, also become important factors. These three variables considered, the authors conclude that “a city is smart when investments in human/social capital and IT infrastructure fuel sustainable growth and enhance a quality of life, through participatory governance”(p. 286).In turn, Leydesdorff & Deakin (2011) introduce a triple helix model of smart cities. They argue that can be considered as densities in networks among three relevant dynamics: the intellectual capital of universities, the wealth creation of industries, and the democratic government of civil society. Lombardi et al. (2011) build on this model and refer to the involvement of the civil society as one of the key actors, alongside the university, theindustry and the government. In Lombardi’s words(2011)“this advanced model presupposes that the four helices operate in a complex urban environment, where civic involvement, along with cultural and social capital endowments, shape the relationships between the traditional helices of university, industry and government. The interplay between these actors and forces determines the success of a city in moving on a smart development path”(p. 8).Yet, so far, one of the most comprehensive and integrative framework for analyzing smart city projects has been presented by Chourabi et al. (2012).The authors present a set of eight dimensions, both internal and external, that affect the design,implementation, and use of smart cities initiatives:1) Management and organization: Organizational and managerial factors such as project size, leadership or change management.2)Technology: Technological challenges such as lack of IT skills.3) Governance: Factors related to the implementation of processes with constituents who exchange information according to rules and standards in order to achieve goals and objectives.4) Policy context: Political and institutional components that represent various political elements and external pressures.5) People and communities: Factors related to the individuals and communities, which are part of the so-called smart city, such as the digital divide or the level of education.6) Economy: Factors around economic variables such as competitiveness,innovation,entrepreneurship, productivity or flexibility.7)Built infrastructure: Availability and quality of the ICT infrastructure.8) Natural environment: Factors related to sustainability and better management of natural resources. Finally, according to Dameri (2013), within the European Union, the concept of smart city is based on four basic elements that composed the city:1) Land: The territorial dimension is not limited to the administrative boundaries of the city but may extend to the region. Sometimes, cities group together and form a network to share knowledge and best practices to tackle urban problems. The city is subjected to influences and regulations of the nation, which itself is affected by more global prerogatives.2)Infrastructures: Buildings, streets, traffic and public transports impact the quality of urban life and urban environment.3) People: All the stakeholders who are linked to the city (students, workers, neighbors, friends, tourists, …).4) Government: Urban policies are defined at the local level, and also at the central level, or even at a more global level, such as the European level, depending on the topic, the action, the project, However, a definition of a smart city is indispensable to define its perimeter and to understand which initiatives can be considered smart and which cannot. Moreover, a standard definition is also the first step for each city to specify its own vision of a smart city strategy. The definition and the comprehensive smart city framework(threats,opportunities,…) are the necessary basis on which to build the smart city goals system. That is why, in this paper, we agree with the Chourabi, et al’s framework(2012) and the Caragliu, etal.’s definition (2009) and consider that cities are smart when investments inhuman and social capital and traditional (transport) and modern (ICT) communication infrastructure fuelsustainable economic growth and a high quality oflife, with a wise management of natural resources,through participatory governance.2.2. On knowledgeAs mentioned in the introduction, the smart city must be able to exploit knowledge that result from data management. This knowledge will result in better decisions in order for the 21st century city to address its main challenges (Negre & Rosenthal-Sabroux, 2014).We suggest an approach to digital information systems centered on people’s information and knowledge of people, in order to improve decisionmaking processes and enhance the value-added of business processes of the city.ICT allow people located outside a city to communicate with other people and to exchange knowledge. These observations concerning knowledge in the city context highlight the importance of tacit knowledge. It points out the interest of creating a favorable climate for both the exchange and sharing of tacit knowledge and its transformation into explicit knowledge and therefore extending the field of knowledge which will come under the rules and regulations governing industrial property (Negre & Rosenthal-Sabroux, 2014).Moreover, we should emphasize the fact that capitalizing on city’s knowledge is an ongoing issue, omnipresent in everyone’s activities, which specifically should have an increasing impact on management functions of the city. Polanyi (1967) classifies the human knowledge into two categories: tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. He says: “tacit knowledge is personal,context-specific, and therefore hard to formalize andcommunicate. Explicit or 'codified' knowledge, on the other hand, refers to knowledge that is transmittable in formal, systematic language" (p.301). Our point of view can be found in the work of Nonaka & Takeuchi (1995), with reference to Polanyi (1967), considering that “tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge are not totally separated but mutually complementary entities”(Nonaka &Takeuchi, 1995: 61). For Nonaka & Takeuchi (1995), explicit knowledge can be easily expressed in written documents but is less likely to result in major decisions than tacit knowledge, which is to say that the decision process stems from knowledge acquired through experience, albeit difficult to express in words.Tangible elements are “explicit knowledge”. Heterogeneous, incomplete or redundant, they are often marked by the circumstances under which knowledge was created. They do not express the unwritten rules of those who formalized knowledge, the “unspoken words”. They arestored and disseminated in archives, cabinets, and databases, ...(Polanyi, 1967).Intangible elements are “tacit knowledge”.Acquired through practice, they are adaptable to the situations. Explicitly or non-explicitly, they are often transmitted by implicit collective apprenticeship or by a master-apprentice relationship. They are located in people's minds (Polanyi, 1967).By analogy with the works of Polanyi (1967),Nelson and Winter (1982), Davenport & Prusak(1998) and Grundstein et al. (2003), the city’s knowledge consists of tangible elements (databases, procedures, drawings, models, documents used for analyzing and synthesizing data, …) and intangible elements (people's needs, unwritten rules of individual and collective behavior patterns, knowledge of the city’s history and decision-making contexts, knowledge of the city environment(citizens, tourists, companies, technologies,influential socio-economic factors, …). All these elements characterize the city’s capability to innovate, produce, sell, and support its services. They are representative of the city’s experience and culture. They constitute and produce the added-valueof the city.These observations concerning knowledge in the city context highlight the importance of tacit knowledge. They point out the interest in taking into account tacit knowledge in decision processes. As a reminder, we believe that the decision in the context of smart cities, where data and knowledge flow, is permanent and important.3. Opportunities and challenges of the smart citiesCities are confronted to a continuous improvement process and have to become smarter and smarter (Negre & Rosenthal-Sabroux, 2014). In doing so, they are confronted with threats and opportunities.Opportunities in cities are given by innovation,education, culture, companies, public organizations and public spaces where people can exchange, make sport, share experiences, meet each other, …On the other side, difficulties related to urbanization, environment protection, pollution,inefficient public transports, traffic, lack of green spaces, social differences, …are threats to city.To deal with these threats and opportunities,questions regarding knowledge in the city arise: How should we link knowledge management to the smart city strategy? What activities should be developed and promoted? What organizational structures should be put in place? How should we go about creating them? How can we implement enabling conditions for knowledge management initiatives?What impact and benefit evaluation methods should be installed?How can we go about provoking cultural change towards a more knowledge-sharing attitude? Within this perspective, we must keep in mind that cities need to evolve through their own efforts, by intensifying diversity and creating new foundations for thought and behavior.A knowledge-based city requires that each citizen takes responsibility for objectives, contributions to the city and, indeed, for behavior as well. This implies that all citizens are stakeholders of the city.This vision places strong emphasis on the ultimate goal of the digital information system which is providing knowledge-citizens, engaged in a daily related decision process, with all the information needed to understand situations they will encounter to make choices - which is to say, to make decisions –to carry out their activities, capitalizing the knowledge produced in the course of performing these tasks.The use of high technology help to improve a better way of life in the city because citizens are more informed, connected and linked. Moreover,using Information and Communication Technology(ICT) is essential to create social inclusion, social communication, civil participation, higher education and information quality.Finally, it is important to note that if smart cities are too connected/linked, they can become ICTaddicts(Viitanen & Kingston, 2014). In that case, it is possible that, one day, some smart cities will be confronted to problems of cyber-security and/or resilience, such as in the new video game “Watch Dogs”(Ubisoft) in which the player is at the heart of a smart and hyper-connected city in which his smartphone gives him/her control of all infrastructures of the CTOs (Central Operating System - high performance system that connects infrastructures and facilities of public security of the city to a centralized exchange pole). The player can handle the traffic lights to create a huge pile or stop a train to board and escape the forces ... Everything that is connected to the network can become a weapon.Opportunities and challenges should be more related to knowledge in the smart city. Therefore, in the next section, we propose to adapt the concept of Enterprise’s Information and Knowledge System(EIKS) introduced by Grundstein & Rosenthal- Sabroux (2009) to smart cities to address challenges related to knowledge in the smart city.4. The Smart City’s Information and Knowledge SystemIn general, an information system “is a set ofelements interconnected which collect (orrecover),process, store and disseminate information in order tosupport decision and process control” (Laudon &Laudon 2006). Grundstein & Rosenthal-Sabroux(2009) introduced the notion of knowledge into the information system and proposed the concept of Enterprise’s Information and Knowledge System(EIKS). In this section, by analogy, we propose our Smart City’s Information and Knowledge System(CIKS) where data and knowledge flow within.Under the influence of globalization and the impact of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) that modify radically our relationship with space and time, the city increasingly develops its activities in a planetary space with three dimensions:•A global space covering the set of cities (the nation).• A local space corresponding to the city located in a given geographic area.•An area of influence that covers the field of interaction of the city with the other cities.The city locked up on its local borders is transformed into an extended city, without borders,opened and adaptable. The land is the territorial dimension of a city, with different levels. These levels range from the local dimension, to regional, network, national and finally the global dimension.Furthermore, this city is placed under the ascendancy of the unforeseeable environment that leads towards uncertainty and doubt.The city meets fundamental problems of information exchange and knowledge sharing among,on the one hand, its formal entities distributed in the world and on the other hand, the city's people(nomadic or sedentary), bearers of diversified values and cultures according to the origin. Two networks of information overlap:• A formal information network between the internal or external entities, in which data and explicit knowledge circulate. This network is implemented by means of intranet and extranet technologies.•An informal information network between nomadic or sedentary peoples. This network favors information exchange and tacit knowledge sharing. It is implemented through converging Information and Communication Technologies (for example the new IPOD with Web 2.0).The problems occur when nomadic people(tourists or students for example) placed in new,unknown or unexpected situations, need to get“active information”, that is, informationand knowledge they need immediately to understand the situation, solve a problem, take a decision, and act.That means that ICT provide the information needed by people who are the heart of the city. By extension, our reflection is: ICT bear potentialities,they bring new uses, they induce a new organization,and they induce a new vision of city, what we call a “smart city”. And, ICT are the heart of the smart city.Building on this, a city can be seen as an information system and because of its hyperconnected nature, smart city can be seen as more than an information system: an information and knowledge system. In fact, the City’s Information and Knowledge System (CIKS) consists mainly in a set of individuals (people) and digital information systems. CIKS rests on a socio technical context,which consists of individuals (people) in interaction among them, with machines, and with the very CIKS. It includes:•Digital Information Systems (DIS), which are artificial systems, the artefacts designed by ICT.•An information system constituted by individuals who, in a given context, are processors of data to which they give a sense under the shape of information. This information, depending of the case, is passed on, remembered, treated, and diffused by them or by the DIS.• A knowledge system, consisting of tacit knowledge embodied by the individuals, and of explicit knowledge formalized and codified on any shape of supports(documents, video, photo, digitized or not).Under certain conditions, digitized knowledge is susceptible to be memorized, processed and spread with the DIS.We must identify information and knowledge to a city’s activities and for individual and collective decision-making processes. The objective could be to design a Digital Information System (DIS) which would allow the city’s stakeholders to receive, to gain access to, and to share the greatest variety of information and knowledge they deem necessary, as rapidly as possible, in order to accelerate decisionmaking processes and to make them as reliable as possible.5. ConclusionThe city has evolved over time: it started with scattered houses, then these houses were grouped into cities, which were industrialized and mechanically connected to other cities and, now, we have hyper connected cities (with citizens who are connected,who need access to different information, and with cities that are connected to the rest of the world)(Kennedy, 2012).In this paper, we propose a conceptual vision of the smart city, based on knowledge. Knowledge can be: explicit knowledge (knowledge extracted from data which flows within the city) and/or tacit knowledge (that is, citizen’s knowledge). According to the previous works on the area of smart cities and knowledge management and the study of threats and opportunities of cities, one specific challenge appears(among some): knowledge must be integrated into the city. Thus, we introduce our Smart City’s Information and Knowledge System (CIKS) where data and knowledge flow within.The smart city is more than Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), and more thanpeople. It also has to do with knowledge (Kennedy,2012; Negre & Rosenthal-Sabroux, 2014).Our vision is an approach that takes into account people, information, knowledge and ICT. From our point of view, knowledge is a factor of competence in order to improve the “smartness”of the city and to handle the complexity of the cities (du, in part, to ICT).6. ReferencesAlAwadhi, S. & Scholl, H. J. (2013). “Aspirations and realizations: the smart city of Seattle”. Paper presented at the 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Maui, HI, January 7-10. Almirall, E. & Wareham, J. (2008). “Living labs and openinnovation: Roles and applicability”. The ElectronicJournal for Virtual Organizations and Networks, 10(special issue): 21-46.AMETIC (2013). Smart cities. Barcelona: AMETIC.Anthopoulos, L. & Vakali, A. (2012). “Urban planning andsmart cities: Interrelations and reciprocities”. In F. Alvarezet al. (eds.). Future Internet Assembly 2012. From promisesto reality. New York: Springer (pp. 178-189). Batty, M. (2013). “Big data, smart cities and city planning”.Dialogues in Human Geography, November 2013 vol. 3no. 3 274-279Bettencourt, L. (2013). “Four simple principles to plan thebest city possible”. New Scientist, 18 (December):30-31.Caragliu, A., Del Bo, C. & Nijkamp, P. (2009). Smart citiesin Europe. Technical report.Chan, C. (2013): “From open data to open innovationstrategies: Creating e-services using open governmentdata”. Paper presented at the 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Big Island (HI), January7-10.Chesbrough, H. (2006).。

城市规划专业英语词汇翻译unban planning 城市规划town planning 城镇规划act of urban planning 城市规划法urban comprehensive planning 城市总体规划urban detailed planning 城市详细规划Residentiral district detailed planning 修建性详规regulatory detailed planning 控制性详规规划类的专业课程reginal planning 区域规划urban system planning 城镇体系规划urban sociology 城市社会学urban economic 城市经济学urban geograghy 城市地理学urban infrastructure planning 城市基础设施规划(water supply and drainage electricity supplyroad building)(城市供水、供电、道路修建)urban road system and transportation planning 城市道路系统和交通规划urban road cross-section 城市道路横断面urban management information system 城市管理信息系统GIS =geograghy information system 地理信息系统RS=remote sensing 遥感Gardening==Landscape architecture 园林=营造景观学Urban landscape planning and design 城市景观规划和设计Urban green space system planning 城市绿地系统规划Urban design 城市设计·Land-use planning 土地利用规划The cultural and historic planning 历史文化名城Protection planning 保护规划Urbanization 城市化Suburbanization 郊区化Public participation 公众参与Sustainable development(sustainability) 可持续性发展(可持续性)Over-all urban layout 城市整体布局Pedestrian crossing 人行横道Human scale 人体尺寸(sculpture fountain teabar) (雕塑、喷泉、茶吧)Traffic and parking 交通与停车Landscape node 景观节点·Brief history of urban planning Archaeological 考古学的Habitat 住处Aesthetics 美学Geometrical 几何学的Moat 护城河Vehicles 车辆,交通工具,mechanization 机械化merchant-trader 商人阶级urban elements 城市要素plazas 广场malls 林荫道·The city and region Adaptable 适应性强的Organic entity 有机体Department stores 百货商店Opera 歌剧院Symphony 交响乐团Cathedrals 教堂Density 密度Circulation 循环Elimination of water 水处理措施In three dimensional form 三维的Condemn 谴责Rural area 农村地区Regional planning agencies 区域规划机构Service-oriented 以服务为宗旨的Frame of reference 参考标准Distribute 分类Water area 水域Alteration 变更Inhabitants 居民Motorway 高速公路Update 改造论文写作Abstract 摘要Key words 关键词Reference 参考资料·Urban problemDimension 大小Descendant 子孙,后代Luxury 奢侈Dwelling 住所Edifices 建筑群<Athens Charter>雅典宪章Residence 居住Employment 工作Recreation 休憩Transportation交通Swallow 吞咽,燕子Urban fringes 城市边缘Anti- 前缀,反对……的;如:antinuclear反核的anticlockwise逆时针的Pro- 前缀,支持,同意……的;如:pro-American 亲美的pro-education重教育的Grant 助学金,基金Sewage 污水Sewer 污水管Sewage treatment plant 污水处理厂Brain drain 人才流失Drainage area 汇水面积Traffic flow 交通量Traffic concentration 交通密度Traffic control 交通管制Traffic bottleneck 交通瓶颈地段Traffic island 交通岛(转盘)Traffic point city 交通枢纽城市Train-make-up 编组站Urban redevelopment 旧城改造Urban revitalization 城市复苏·Urban FunctionUrban fabric 城市结构Urban form 城市形体Warehouse 仓库Material processing center 原料加工中心Religious edifices 宗教建筑Correctional institution 教养院Transportation interface 交通分界面CBD=central business district 城市中心商业区Public agencies of parking 停车公共管理机构Energy conservation 节能Individual building 单一建筑Mega-structures 大型建筑Mega- 大,百万,强Megalopolis 特大城市Megaton 百万吨R residence 居住用地黄色C commercial 商业用地红色M manufacture 工业用地紫褐色W warehouse 仓储用地紫色T transportation 交通用地蓝灰色S square 道路广场用地留白处理U utilities 市政公共设施用地接近蓝灰色G green space 绿地绿色P particular 特殊用地E 水域及其他用地(除E外,其他合为城市建设用地)Corporate 公司的,法人的Corporation 公司企业Accessibility 可达性;易接近Service radius 服务半径。