间质性膀胱炎的诊疗策略

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:1.31 MB

- 文档页数:23

间质性膀胱炎治疗间质性膀胱炎/膀胱疼痛综合征(IC / BPS)是一种慢性疼痛综合征,其病因尚不清楚。

因此,没有治愈性治疗,管理的目标是提供症状缓解以达到适当的生活质量。

IC / BPS有许多治疗方法,并且没有一种被证明对所有IC / BPS患者有帮助。

我们采用逐步方法处理IC / BPS。

另一种方法是根据患者的主要症状量身定制的个性化治疗计划。

对于一些患者,连续或同时治疗的组合可能是合适的,但是每个治疗应该单独启动以能够监测症状反应并且停止无效治疗。

如果在一线和二线治疗的几次试验后没有改善,则应重新考虑IC / BPS的诊断。

个体患者特征可能会影响治疗方案的选择,包括:症状特征(严重程度,位置,进展)。

以前有效或无效的治疗方法。

合并症,对于患有慢性病(例如纤维肌痛,肠易激综合征,抑郁症,焦虑症)的IC / BPS患者,需要采用多学科方法进行最佳管理。

患者偏好。

根据症状的严重程度和进展以及患者偏好,在某些患者中,快速进行更积极的治疗可能是合理的。

例如,在症状迅速恶化的患者中,如果对口服药物没有快速反应,可以选择进行膀胱镜检查并进行水分注射和膀胱内治疗。

使用镇痛药,镇痛药可以在IC / BPS患者的任何治疗点使用,目的是尽量减少疼痛和最大化功能。

一般来说,止痛药用于短期缓解膀胱疼痛的发作,而不是作为主要治疗。

它们的使用应以不利影响和依赖性的风险为指导。

在一些IC / BPS 患者中,与其他慢性疼痛病症一样,考虑到副作用和禁忌症,可能需要长期使用口服或透皮镇痛药。

尿液镇痛药,尿液镇痛药可以缓解泌尿系统症状。

可用的尿液镇痛药在可接受的使用时间上差别很大; 非那吡啶是用于短期使用,而乌洛托品可以长期使用。

一线治疗一线疗法目前最小的风险,并应提供给所有患者。

对于轻度间质性膀胱炎/膀胱疼痛综合征(IC / BPS)症状的患者,一线治疗可能单独有效。

自我护理和行为改变,应与所有患者讨论自我护理实践和行为改变,并在可行的情况下实施。

间质性膀胱炎的诊治原则写在课前的话间质性膀胱炎是一种慢性的、严重的膀胱壁炎症,常发生于中年妇女,其特点主要是膀胱壁的纤维化,并伴有膀胱容量的减少,以尿频、尿急、膀胱区胀痛为其主要症状。

对中年妇女出现严重尿频,尿急及夜尿增多伴耻骨上方膀胱区胀痛而尿检查正常者应想到间质性膀胱炎。

一、下尿路感染的定义下尿路感染是指细菌致病菌通过逆行的淋巴或血液进入尿液后引起下尿路的感染。

下尿路一般只是指膀胱炎和尿道炎,膀胱炎指感染主要位于膀胱,尿道炎指感染主要位于尿道。

下尿路感染分成单纯下尿路感染和复杂下尿路感染。

单纯性下尿路感染多指无解剖异常的下尿路一般细菌感染。

复杂性下尿路感染多指伴发上尿路感染或存在感染扩散高危因素。

二、细菌性膀胱炎(一)细菌性膀胱炎的病因下尿路感染最常见的是细菌性膀胱炎,它是人类最常见的一类细菌性感染,要远远高于上呼吸道感染。

多见于女性,女性和男性的比例为30:1,每年全世界约有10%的女性会罹患细菌性膀胱炎,约50%的女性会一生中至少有一次下尿路感染。

细菌性膀胱炎最常见是大肠埃希氏菌,大肠埃希氏菌有很多类型。

为什么女性容易发生细菌性膀胱炎?在门诊时很多女性都会问如何避免细菌性膀胱炎?这涉及到细菌性膀胱炎的诱因。

(二)细菌性膀胱炎的诱因1.引起尿流率下降的因素引起尿流率下降的因素常见的有:(1)膀胱出口梗阻、前列腺增生、前列腺癌、尿道狭窄、膀胱内异物(如膀胱结石);(2)神经源性膀胱;(3)水摄入不足:尿量降低和速率下降会引起膀胱内的细菌排出不足,容易引发细菌性膀胱炎。

2.促进细菌种植的因素促进细菌种植是细菌能在膀胱黏膜大量繁殖的基础,膀胱黏膜有IgG抗体可以抑制细菌黏附在膀胱上,但是有些情况会导致细菌种植的增加。

比如女性性活动、应用杀精药、绝经期女性雌激素水平降低,或长期滥用抗生素导致正常菌群减少。

3.细菌逆行感染增加(1)老年女性的最多见的是粪失禁和尿失禁;(2)排尿困难和功能障碍的病人,留置尿管也会引起细菌黏附在膀胱上;(3)膀胱壁缺血的因素,如膀胱老化,膀胱壁的神经和血管减少,容易纤维化,这时血控降低、黏膜菲薄,细菌更容易黏附在膀胱黏膜上,导致细菌性膀胱炎的发生。

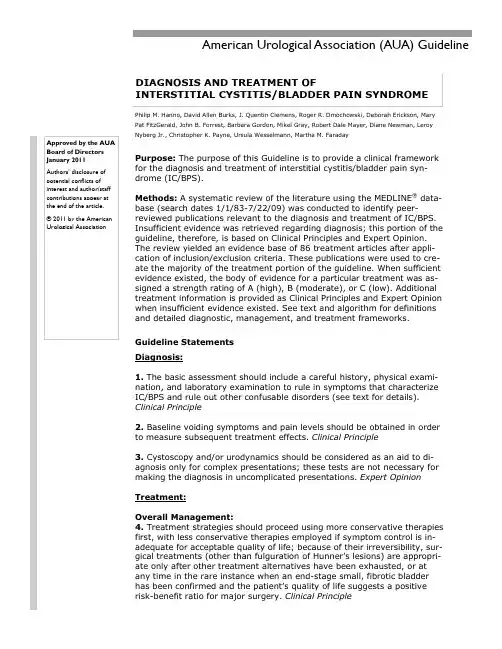

Purpose: The purpose of this Guideline is to provide a clinical framework for the diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syn-drome (IC/BPS).Methods: A systematic review of the literature using the MEDLINE ® data-base (search dates 1/1/83-7/22/09) was conducted to identify peer-reviewed publications relevant to the diagnosis and treatment of IC/BPS. Insufficient evidence was retrieved regarding diagnosis; this portion of the guideline, therefore, is based on Clinical Principles and Expert Opinion. The review yielded an evidence base of 86 treatment articles after appli-cation of inclusion/exclusion criteria. These publications were used to cre-ate the majority of the treatment portion of the guideline. When sufficient evidence existed, the body of evidence for a particular treatment was as-signed a strength rating of A (high), B (moderate), or C (low). Additional treatment information is provided as Clinical Principles and Expert Opinion when insufficient evidence existed. See text and algorithm for definitions and detailed diagnostic, management, and treatment frameworks.Guideline StatementsDiagnosis:1. The basic assessment should include a careful history, physical exami-nation, and laboratory examination to rule in symptoms that characterize IC/BPS and rule out other confusable disorders (see text for details). Clinical Principle2. Baseline voiding symptoms and pain levels should be obtained in order to measure subsequent treatment effects. Clinical Principle3. Cystoscopy and/or urodynamics should be considered as an aid to di-agnosis only for complex presentations; these tests are not necessary for making the diagnosis in uncomplicated presentations. Expert OpinionTreatment:Overall Management:4. Treatment strategies should proceed using more conservative therapies first, with less conservative therapies employed if symptom control is in-adequate for acceptable quality of life; because of their irreversibility, sur-gical treatments (other than fulguration of Hunner‘s lesions) are appropri-ate only after other treatment alternatives have been exhausted, or at any time in the rare instance when an end-stage small, fibrotic bladder has been confirmed and the patient‘s quality of life suggests a positive risk-benefit ratio for major surgery. Clinical PrincipleApproved by the AUA Board of Directors January 2011 Authors’ disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and author/staff contributions appear at the end of the article. © 2011 by the American Urological AssociationAmerican Urological Association (AUA) GuidelineDIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OFINTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS/BLADDER PAIN SYNDROMEPhilip M. Hanno, David Allen Burks, J. Quentin Clemens, Roger R. Dmochowski, Deborah Erickson, Mary Pat FitzGerald, John B. Forrest, Barbara Gordon, Mikel Gray, Robert Dale Mayer, Diane Newman, Leroy Nyberg Jr., Christopher K. Payne, Ursula Wesselmann, Martha M. FaradayAmerican Urological Association Interstitial Cystitis 2 5. Initial treatment type and level should depend on symptom severity, clinician judgment, and patient preferences; appropriate entry points into the treatment portion of the algorithm depend on these fac-tors. Clinical Principle6. Multiple, simultaneous treatments may be considered if it is in the best interests of the patient; base-line symptom assessment and regular symptom level re-assessment are essential to document efficacy of single and combined treatments. Clinical Principle7. Ineffective treatments should be stopped once a clinically meaningful interval has elapsed. Clinical Principle8.Pain management should be continually assessed for effectiveness because of its importance to quality of life. If pain management is inadequate, then consideration should be given to a multidisciplinary ap-proach and the patient referred appropriately. Clinical Principle9. The IC/BPS diagnosis should be reconsidered if no improvement occurs after multiple treatment ap-proaches. Clinical PrincipleTreatments that may be offered: Treatments that may be offered are divided into first-, second-, third-, fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-line groups based on the balance between potential benefits to the pa-tient, potential severity of adverse events and the reversibility of the treatment. See body of guideline for protocols, study details, and rationales.First-Line Treatments: First-line treatments should be performed on all patients.10. Patients should be educated about normal bladder function, what is known and not known about IC/ BPS, the benefits vs. risks/burdens of the available treatment alternatives, the fact that no single treat-ment has been found effective for the majority of patients, and the fact that acceptable symptom control may require trials of multiple therapeutic options (including combination therapy) before it is achieved. Clinical Principle11. Self-care practices and behavioral modifications that can improve symptoms should be discussed and implemented as feasible. Clinical Principle12. Patients should be encouraged to implement stress management practices to improve coping tech-niques and manage stress-induced symptom exacerbations. Clinical PrincipleSecond-line treatments:13. Appropriate manual physical therapy techniques (e.g., maneuvers that resolve pelvic, abdominaland/or hip muscular trigger points, lengthen muscle contractures, and release painful scars and other connective tissue restrictions), if appropriately-trained clinicians are available, should be offered. Pelvic floor strengthening exercises (e.g., Kegel exercises) should be avoided. Clinical Principle14. Multimodal pain management approaches (e.g., pharmacological, stress management, manual ther-apy if available) should be initiated. Expert Opinion15. Amitriptyline, cimetidine, hydroxyzine, or pentosan polysulfate may be administered as second-line oral medications (listed in alphabetical order; no hierarchy is implied). Options (Evidence Strength- Grades B, B, C, and B)16. DMSO, heparin, or lidocaine may be administered as second-line intravesical treatments (listed in alphabetical order; no hierarchy is implied). Option (Evidence Strength- Grades C, C, and B)American Urological Association Interstitial Cystitis 3Third-line treatments:17. Cystoscopy under anesthesia with short-duration, low-pressure hydrodistension may be undertaken if first- and second-line treatments have not provided acceptable symptom control and quality of life or if the patient‘s presenting symptoms suggest a more-invasive approach is appropriate. Option (EvidenceStrength- Grade C)18. If Hunner‘s lesions are present, then fulguration (with laser or electrocautery) and/or injection of tri-amcinolone should be performed. Recommendation (Evidence Strength- Grade C)Fourth-line treatment:19. A trial of neurostimulation may be performed and, if successful, implantation of permanent neu-rostimulation devices may be undertaken if other treatments have not provided adequate symptom con-trol and quality of life or if the clinician and patient agree that symptoms require this approach. Option (Evidence Strength- C)Fifth-line treatments:20. Cyclosporine A may be administered as an oral medication if other treatments have not provided adequate symptom control and quality of life or if the clinician and patient agree that symptoms require this approach. Option (Evidence Strength- C)21. Intradetrusor botulinum toxin A (BTX-A) may be administered if other treatments have not provided adequate symptom control and quality of life or if the clinician and patient agree that symptoms require this approach. Patients must be willing to accept the possibility that post-treatment intermittent self-catheterization may be necessary. Option (Evidence Strength- C)Sixth-line treatment:22. Major surgery (e.g., substitution cystoplasty, urinary diversion with or without cystectomy) may be undertaken in carefully selected patients for whom all other therapies have failed to provide adequate symptom control and quality of life (see caveat above in guideline statement #4). Option (Evidence Strength- C)Treatments that should not be offered: The treatments below appear to lack efficacy and/or appear to be accompanied by unacceptable adverse event profiles. See body of guideline for study details and rationales.23. Long-term oral antibiotic administration should not be offered. Standard (Evidence Strength- B)24. Intravesical instillation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) should not be offered outside of investiga-tional study settings. Standard (Evidence Strength- B)25. Intravesical instillation of resiniferatoxin should not be offered. Standard (Evidence Strength- A)26. High-pressure, long-duration hydrodistension should not be offered. Recommendation (Evidence Strength- C)27. Systemic (oral) long-term glucocorticoid administration should not be offered. Recommendation (Evidence Strength- C)INTRODUCTIONPurposePurposeThis guideline‘s purpose is to provide direction to clinicians and patients regarding how to: recognize interstitial cystitis (IC)/bladder pain syndrome (BPS); conduct a valid diagnostic process; and, approach treatment with the goals of maximizing symptom control and pa-tient quality of life (QoL) while minimizing ad-verse events and patient burden. The strate-gies and approaches recommended in this document were derived from evidence-based and consensus-based processes. IC/BPS no-menclature is a controversial issue; for the purpose of clarity the Panel decided to refer to the syndrome as IC/BPS and to consider these terms synonymous. There is a continually ex-panding literature on IC/BPS; the Panel notes that this document constitutes a clinical strat-egy and is not intended to be interpreted rig-idly. The most effective approach for a particu-lar patient is best determined by the individual clinician and patient. As the science relevant to IC/BPS evolves and improves, the strategies presented here will require amendment to re-main consistent with the highest standards of clinical care. MethodologyA systematic review was conducted to iden-tify published articles relevant to the diagno-sis and treatment of IC/BPS. Literature searches were performed on English-language publications using the MEDLINE da-tabase from January 1, 1983 to July 22, 2009 using the terms ―interstitial cystitis,‖ ―painful bladder syndrome,‖ ―bladder pain syndrome,‖ and ―pelvic pain‖ as well as key words cap-turing the various diagnostic procedures and treatments known to be used for these syn-dromes. Studies published after July 22, 2009 were not included as part of the evi-dence base considered by the Panel from which evidence-based guideline statements (Standards, Recommendations, Options) were derived. A few studies published after this cut-off date provided relevant informa-tion and are cited in the text as background material. Data from studies published after the literature search cut-off will be incorpo-rated into the next version of this guideline. Preclinical studies (e.g., animal models), pe-diatric studies, commentary, and editorials were eliminated. Review article references were checked to ensure inclusion of all possi-bly relevant studies. Studies using treat-ments not available in the U.S., herbal or supplement treatments, or studies that re-ported outcomes information collapsed across multiple interventions also were excluded. Studies on mixed patient groups (i.e., some patients did not have IC/BPS) were retained as long as more than 50% of patients were IC/BPS patients. Multiple reports on the same patient group were carefully examined to en-sure inclusion of only nonredundant informa-tion. In a few cases, individual studies consti-tuted the only report on a particular treatment. Because sample sizes in individual studies were small, single studies were not considered a suf-ficient and reliable evidence base from whichto construct an evidence-based statement (i.e., a Standard, Recommendation, or Option). These studies were used to support Clinical Principles as appropriate.IC/BPS Diagnosis and Overall Manage-ment. The review revealed insufficient publi-cations to address IC/BPS diagnosis and overall management from an evidence basis; the diag-nosis and management portions of the algo-rithm (see Figure 1), therefore, are provided as Clinical Principles or as Expert Opinion with consensus achieved using a modified Delphi technique if differences of opinion emerged.1 A Clinical Principle is a statement about a compo-nent of clinical care that is widely agreed upon by urologists or other clinicians for which there may or may not be evidence in the medical lit-erature. Expert Opinion refers to a statement, achieved by consensus of the Panel, that is based on members' clinical training, experi-ence, knowledge, and judgment for which there is no evidence.IC/BPS Treatment. With regard to treat-ment, a total of 86 articles met the inclusion criteria; the Panel judged that these were a sufficient evidence base from which to con-struct the majority of the treatment portion of the algorithm. Data on study type (e.g., ran-domized controlled trial, randomized crossover trial, observational study), treatment parame-ters (e.g., dose, administration protocols, fol-low-up durations), patient characteristics (i.e., age, gender, symptom duration), ad-verse events, and primary outcomes (as de-fined by study authors) were extracted. The primary outcome measure for most studies was some form of patient-rated improvement scale. For studies that did not use this type of measure, other outcomes were extracted (e.g., ICPS, ICSS, VAS scales).Quality of Individual Studies and Deter-mination of Evidence Strength. Quality of individual studies that were randomized con-trolled trials (RCTs) or crossover trials was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.2 Because placebo effects are common in controlled trials conducted with IC/BPS pa-tients, any apparent procedural deviations that could compromise the integrity of ran-domization or blinding resulted in a rating of increased risk of bias for that particular trial. Because there is no widely-agreed upon qual-ity assessment tool for observational studies, the quality of individual observational studies was not assessed.The categorization of evidence strength is conceptually distinct from the quality of individual studies. Evidence strength refers to the body of evidence avail-able for a particular question and includes consideration of study design, individual study quality, the consistency of findings across studies, the adequacy of sample sizes, and the generalizability of samples, settings, and treatments for the purposes of the guide-line. AUA categorizes body of evidence strength as Grade A (well-conducted RCTs orexceptionally strong observational studies), Grade B (RCTs with some weaknesses of pro-cedure or generalizability or generally strong observational studies), or Grade C (observational studies that are inconsistent, have small sample sizes, or have other prob-lems that potentially confound interpretation of data). Because treatment data for this condi-tion are difficult to interpret in the absence of a placebo control, bodies of evidence comprised entirely of studies that lacked placebo control groups (i.e., observational studies) were as-signed a strength rating of Grade C.AUA Nomenclature: Linking Statement Type to Evidence Strength. The AUA no-menclature system explicitly links statement type to body of evidence strength and the Panel‘s judgment regarding the balance be-tween benefits and risks/burdens.3Standards are directive statements that an action should (benefits outweigh risks/burdens) or should not (risks/burdens outweigh benefits) be un-dertaken based on Grade A or Grade B evi-dence. Recommendations are directive state-ments that an action should (benefits outweigh risks/burdens) or should not (risks/burdens outweigh benefits) be undertaken based on Grade C evidence. Options are non-directive statements that leave the decision to take an action up to the individual clinician and patient because the balance between benefits and risks/burdens appears relatively equal or ap-pears unclear; Options may be supported by Grade A, B, or C evidence. In the treatment portion of this guideline, most statements are Options because most treatments demonstrate limited efficacy in a subset of patients that is not readily identifiable a priori. The Panel in-terpreted these data to indicate that for a particular patient, the balance between bene-fits and risks/burdens is uncertain or rela-tively equal and whether to use a particular treatment is a decision best made by the cli-nician who knows the patient with full consid-eration of the patient‘s prior treatment his-tory, current quality of life, preferences and values.Limitations of the Literature. The Panel proceeded with full awareness of the limita-tions of the IC/BPS literature. These limita-tions include: poorly-defined patient groups or heterogeneous groups; small sample sizes; lack of placebo controls for many stud-ies, resulting in a likely over-estimation of efficacy; short follow-up durations; and, use of a variety of outcome measures. With re-gard to measures, even though the most consistently used measure was some form of patient-rated improvement scale, the scales differed across studies in anchor points, num-ber of gradations, and descriptors. Overall, these difficulties resulted in limited utility for meta-analytic procedures. The single meta-analysis reported here was used to calculate an overall effect size for data from random-ized trials that evaluated pentosan polysul-fate (PPS). No comparative procedures were undertaken.BackgroundDefinition. The bladder disease complex in-cludes a large group of patients with bladder and/or urethral and/or pelvic pain, lower uri-nary tract symptoms, and sterile urine cul-tures, many with specific identifiable causes. IC/BPS comprises a part of this complex. The Panel used the IC/BPS definition agreed upon by the Society for Urodynamics and Female Urology (SUFU): ―An unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes‖.4 This definition was selected because it allows treatment to begin after a relatively short symptomatic period, preventing treatment withholding that could occur with definitions that require longer symptom durations (i.e., six months). Defini-tions used in research or clinical trials should be avoided in clinical practice; many patients may be misdiagnosed or have delays in diag-nosis and treatment if these criteria are em-ployed.5Epidemiology. Since there is no objective marker to establish the presence of IC/BPS, studies to define its prevalence are difficult to conduct. Population-based prevalence studies of IC/BPS have used three methods: surveys that ask participants if they have ever been di-agnosed with the condition (self-report stud-ies); questionnaires administered to identify the presence of symptoms that are suggestive of IC/BPS (symptom assessments); and, ad-ministrative billing data used to identify the number of individuals in a population who have been diagnosed with IC/BPS (clinician diagnosis). Not surprisingly, the use of differ-ent methods yields widely disparate preva-lence estimates.Self-Report Studies. Two large-scale stud-ies in the United States have utilized self-report to estimate the prevalence of IC/BPS. The first was conducted as part of the 1989 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), and the second was part of the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES III), which was conducted between 1988 and 1994. The same definition of IC/ BPS was used in both studies. Participants were asked, ―Have you ever had symptoms of a bladder infection (such as pain in your bladder and frequent urination) that lasted more than 3 months?‖ Those who gave a positive response were then asked, ―When you had this condition, were you told that you had interstitial cystitis or painful bladder syndrome?‖ An affirmative answer to both questions was considered to define the pres-ence of IC/BPS. The prevalence estimates ob-tained from these two studies were virtually identical. In the NHIS, the overall prevalence was 500 per 100,000 population, and the prevalence in women was 865 per 100,000.6 In NHANES III, the prevalence was 470 per 100,000 population, including 60 per 100,000 men and 850 per 100,000 women.6 This equals approximately 83,000 men and 1.2 million women across the U.S.IC/BPS Symptoms. Multiple studies have estimated the prevalence of IC/BPS symp-toms, using a variety of different case defini-tions. A mailed questionnaire study to 1,331 Finnish women aged 17-71 identified probable IC/BPS symptoms in 0.45%.7 Another ques-tionnaire mailing study to enrollees aged 25-80 in a managed care population in the U.S. Pa-cific Northwest identified IC/BPS symptoms in 6-11% of women and 2–5% of men, depend-ing on the definition used.8 Investigators in the Boston Area Community Health study con-ducted door-to-door interviews about urologic symptoms in a sample of Black, Hispanic and White individuals aged 30-79.9 They identified IC/BPS symptoms using six different defini-tions, which yielded prevalence estimates ranging from 0.6% to 2.0%. Across these defi-nitions, symptoms were typically two to three times as common in women as men, but no clear variations were observed by race/ ethnicity. Questions about IC/BPS symptoms were included in the 2004 version of the U.S. Nurses Health Study (NHS), which was admin-istered to women aged 58 to 83 years.10 In this cohort of women, the prevalence of IC/BPS symptoms was 2.3%. The prevalence in-creased with age, from 1.7% of those younger than 65 years up to 4.0% in women aged 80 years or older. In a study of 981 Austrian women aged 19-89 at a voluntary health screening project in Vienna, the prevalence of IC/BPS symptoms was determined to be 0.3% (306 per 100,000).11 Finally, the RAND Inter-stitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) investiga-tors conducted telephone interviews from a random sample of over 100,000 households across the United States.12 Using validated case definitions to identify IC/BPS, the esti-mated prevalence in adult women aged >18 ranged from 2.7% (high specificity case defi-nition) to 6.5% (high sensitivity case defini-tion).Clinician Diagnosis. Female participants in the NHS were asked by mailed questionnaires in 1994 and 1995 whether they had ever been diagnosed with ‗interstitial cystitis (not urinary tract infection)‘. In participants with a positive response, medical record reviews were performed to confirm a physician diag-nosis, including cystoscopy performed by a urologist. Using these methods, the preva-lence of IC/BPS was found to be 52/100,000 in the NHS I cohort, and 67/100,000 in the NHS II cohort.13 A subsequent study was per-formed using administrative billing data from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest managed care population in the Portland, Oregon met-ropolitan area.8 Patients with IC/BPS were identified by the presence of ICD-9 code 595.1 (‗interstitial cystitis‘) in the electronic medical record, and the prevalence of the di-agnosis was found to be 197 per 100,000 women and 41 per 100,000 men.Typical Course and Comorbidities. IC/BPS is most commonly diagnosed in the fourth decade or after, although the diagnosis may be delayed depending upon the index of sus-picion for the disease, and the criteria usedto diagnose it.14 For instance, in European studies, where more strict criteria are typi-cally used to make the diagnosis, the mean age is older than is typical for the US. A his-tory of a recent culture-proven UTI can be identified on presentation in 18-36% of women, although subsequent cultures arenegative.15, 16 Initially it is not uncommon for patients to report a single symptom such as dysuria, frequency, or pain, with subsequent progression to multiple symptoms.17, 18 Symp-tom flares, during which symptoms suddenly intensify for several hours, days, or weeks, are not uncommon. There is a high rate of prior pelvic surgery (especially hysterectomy) and levator ani pain in women with IC/BPS, sug-gesting that trauma or other local factors may contribute to symptoms.19 It is important to note, however, that the high incidence of other procedures such as hysterectomy or laparo-scopy may be the result of a missed diagnosis and does not necessarily indicate that the sur-gical procedure itself is a contributing factor to symptoms. It is also common for IC/BPS to co-exist with other unexplained medical conditions such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, Sjogren‘s syndrome, chronic headaches, and vulvodynia.20, 21 These associations suggest that there may be a sys-temic dysregulation in some patients. Finally, patients with IC/BPS frequently exhibit mental health disorders such as depression and anxi-ety. While these symptoms may be reactive in some IC/BPS patients, there is also some evi-dence that there may be a common biologic mechanism involved. For instance, a link be-tween IC/BPS and panic disorder has been suggested from genetic linkage studies.22, 23Conceptualizing IC/BPS. It is not known whether IC/BPS is a primary bladder disorder or whether the bladder symptoms of IC/BPS are a secondary phenomena resulting from an-other cause. Converging data from several sources suggest, however, that IC/BPS can be conceptualized as a bladder pain disorder that is often associated with voiding sympto-matology and other systemic chronic pain disorders. Specifically, IC/BPS may be a bladder disorder that is part of a more gener-alized systemic disorder, at least in a subset of patients.Initial observations suggesting this conceptualization were made by Clauw and colleagues (1997). He noted among chronic pelvic pain patients that other chronic pain disorders such as interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia tended to co-occur.24 He suggested that there might be a common central pathogenesis and pathophysiology for these disorders. Self-report data collected by the Interstitial Cystitis Association corrobo-rated Clauw‘s findings and showed an asso-ciation between IC/BPS and other chronic pain disorders.25 Aaron and Buchwald (2001) analyzed a co-twin control study and sup-ported the findings previously reported by Clauw and colleagues (1997).26 Additional epidemiologic studies support these data and suggest that if the IC patient is properly as-sessed during the diagnostic evaluation, many of these somatic symptoms are also present.Considering these data, it has been suggested that IC/BPS is a member of a fam-ily of hypersensitivity disorders which affects the bladder and other somatic/visceral or-gans, and has many overlapping symptoms and pathophysiology.27, 28 An additional hy-pothesis is that IC/BPS might be just a part of the continuum of painful vs. non-painful overactive bladder syndrome (OAB).29, 30Challenge to Patient and Clinician: Impact on Psychosocial Functioning and Qualityof Life (QoL). The effects of IC/BPS on psy-chosocial functioning and QoL are pervasive and insidious, damaging work life, psychologi-cal well-being, personal relationships and gen-eral health.9 QoL is poorer in IC/BPS patients than in controls.9, 31, 32 Rates of depression are also higher.31-33 In addition, IC/BPS patients have significantly more pain, sleep dysfunction, catastrophizing, depression, anxiety, stress, social functioning difficulties and sexual dys-function than do non-IC/BPS age-matched women.34, 35 The impact of IC/BPS on QoL is as severe as that of rheumatoid arthritis and end-stage renal disease.9, 36 Health-related QoL in women with IC/BPS is worse than that of women with endometriosis, vulvodynia or overactive bladder.37 Given that IC/BPS causes considerable morbidity over the course of a pa-tient‘s life and loss of work during the most productive years of work and family life signifi-cant negative psychological and QoL impacts are not surprising.9Sexual dysfunction has an especially im-portant impact on the QoL of IC/BPS patients. In IC/BPS patients, sexual dysfunction is mod-erate to severe38 and occurs at high rates com-pared with controls.39, 40 In women with treat-ment-refractory IC/BPS, poor sexual function is a primary predictor of poor mental QoL.41 Pain appears to mediate sexual dysfunction and its associated effects on QoL. Adult women with IC/BPS report rates of intercourse, desire, and orgasm frequency in their adolescence that are similar to those reported by controls, but rates diverge in adulthood, when IC/BPS patients re-port significantly more pain and fear of pain with intercourse and more sexual distress.39 The strong link between IC/BPS symp-toms and psychosocial functioning and QoL make clear the critical importance of optimiz-ing treatment of IC/BPS symptoms. Success-ful treatment of the medical condition clearly brings improvement in functioning and QoL. Response to therapy is associated with im-proved overall QoL.42 In addition, response to therapy is associated with improved sexual function and sleep, with concomitant im-provements in QoL.34, 38Cost. Quantifying the economic burden ofIC/BPS on the American health care system is difficult because of the lack of an objective marker for diagnosis, resulting in uncertainty regarding its true prevalence. Direct costs as-sociated with IC/BPS are incurred through physician visits, prescription medications, outpatient procedures, and hospitalization. These costs are greater than the mean an-nual per-person direct costs of diabetes melli-tus, depression, hypertension, and asthma.43 They are also more consistent across geo-graphic regions of the United States than other urologic conditions.44 Because of the chronicity of the condition, these costs typi-cally persist over years. The indirect costs of IC/BPS, including time away from work and lost productivity while working, are particu-larly significant since the condition primarily affects working age adults, and especially women aged 25-50 years. The psychosocial costs such as social, educational and career related activities not pursued, as well as the emotional distress, depression, social isola-tion, and diminished QoL have not been。

膀胱炎的怎么治疗方法

膀胱炎的治疗方法主要包括以下几个方面:

1. 利尿和排空膀胱:多喝水,经常排尿可以帮助清洗膀胱,排除细菌和毒素。

2. 使用药物治疗:医生可以根据病情给予抗生素来杀灭感染膀胱的细菌,常用的抗生素有氟喹诺酮类、β-内酰胺类等。

3. 缓解症状:可以使用止痛药(如扑热息痛)或非处方的尿道麻醉剂(如利多卡因凝胶)来缓解膀胱炎引起的疼痛和不适。

4. 避免刺激性食物和饮料:避免摄入刺激性食物和饮料,如咖啡、茶、辣椒、酒精等,以防止刺激膀胱加重炎症。

5. 保持个人卫生:保持外阴干燥清洁,勤换内衣内裤,不憋尿,注意避免患上感冒等感染。

6. 中医中药治疗:有些中药可以具有消炎、杀菌和抗病毒作用。

请咨询中医师或配药师的意见。

需要注意的是,如果膀胱炎症状严重或反复发作,建议及时就医,接受专业医生的医学指导和治疗。

间质性膀胱炎的诊治作者:罗耀辉刘乔保肖民辉杨晓华【关键词】膀胱炎【摘要】目的探讨间质性膀胱炎的诊断及治疗。

方法对16例根据犯仙0〖诊断标准确诊的间质性膀胱炎的临床资料进行分析,总结该病特点及治疗效果。

结果16例间质性膀胱炎中仅2例膀胱镜检查发现典型此而^溃疡。

无溃疡型14例(87.5%),膀胱平均容量285^1;组织病理学报告4例(25%)无炎性表现;12例膀胱呈非特异性炎性表现,其中有3例(25%)是粘膜下层组织肥大细胞明显增多。

治疗用膀胱药物灌注,膀胱水压扩张及口服药物。

12例(75%)有明显效果。

结论间质性膀胱炎诊断及治疗困难,易误诊而延误治疗,诊断主要依靠典型临床症状,膀胱镜检及病理学改变。

大多数病人采取综合治疗可获得明显疗效。

关键词膀胱炎间质炎症诊断及治疗.【Abstract】 Objective To investigate the clinical diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis. Methods We retrospectively analyzed the diagnostic and treatment data ofl6cases withinterstitial cystitis, as well as summa ~ rized the characteristics and curative effects of this disease. Results Cystoscopic examination revealed2patients with classic Hunner' s ulcers andl4 (87. 5%) patients non-ulcer. Subtypes. Average bladder capacitywas285ml. Histopathological examination revealed no inflammationin4patients (6. 3%) and chronic inflammation inl2. Of them3patients(25%) were with an increase in mast cells in thesubmucosa. 12patients (75%) showed the evident effects by treatment of intravesical administration, hydrodistention and takingmedicines. Conclusion The diagnosis and treatment of interstitialcystitis is relatively difficult and apt to misdiagnosis. Diagnosis ismainly relied on specific symptoms, cystoscopy andhistopathololgy. The majority of patients may obtain the good effectsby compound therapies.Key words cyctitis interstitial inflammation diagnosis andtherapeutics间质膀胱炎(IC)是一种特殊类型的慢性膀胱炎。

间质性膀胱炎的治疗进展

*导读:IC是一个综合征而不是一个具有单一发病机制的疾病,因此不可能使用单一的治疗形式。

……

尽管文献中报告的治疗方法有183种之多,但迄今被美国食品与药物管理局(FDA)批准用于IC治疗的只有口服戊糖多硫酸和膀

胱内灌注二甲亚砜(DMSO)。

两者发挥作用的具体机制不明。

多数研究观察到口服戊糖多硫酸可以改善病情,但增加剂量并无益处,而延长治疗时间似乎有效。

近来报道使用环孢素可能比戊糖多硫酸更有效,但不良反应增加。

有研究认为使用三环类抗抑郁药阿米曲替林和局部麻醉药利多卡因进行神经调节对治疗IC有效,但是使用更特异的辣椒辣

素和树脂毒却未能获得一致结果,因此对这类药物的疗效尚需要进一步评估。

骶神经根调节是治疗尿频最成功的方法之一,但在IC治疗中的

地位仍需评估。

许多症状严重的IC患者可通过麻醉剂缓解症状,但目前对于在本病患者中长期使用麻醉剂存在争议。

其他的辅助治疗包括骨盆底部物理治疗以及对抑郁和疼痛的治疗未被充分

使用。

IC是一个综合征而不是一个具有单一发病机制的疾病,因此不可能使用单一的治疗形式。

目前常用戊糖多硫酸结合抗组胺药和三环类神经调节剂联合治疗。

尽管目前本病的治疗并不理想,但对

APF的研究有希望为本病的诊断和干预带来新的进展。

一些新的治疗,比如基因治疗、肉毒杆菌毒素和新的膀胱上皮涂层策略,

尚在进行动物实验或前瞻性研究中。

但即使采用现有的治疗方法,早期发现和治疗本病也可以改善预后并减轻患者的负担。

间质性膀胱炎,间质性膀胱炎的症状,间质性膀胱炎治疗【专业知识】疾病简介间质性膀胱炎(intetitial cystitis,IC)又称Hunner’s溃疡,是一种少见的自身免疫性特殊类型的慢性膀胱炎,常发生于中年妇女,其特点主要是膀胱壁的纤维化,并伴有膀胱容量的减少,以尿频、尿急、膀胱区胀痛为其主要症状。

表现为痛性膀胱疾病,症状多持续1年以上。

病变累及膀胱全层,黏膜肿胀、充血并可发生裂隙或溃疡,溃疡常位于膀胱前壁和顶部。

病期多在3~5年,典型表现为疾病开始快速发展,以后很快稳定下来,既使没有进行治疗,也无明显恶化的表现。

疾病病因一、发病原因本病病因迄今仍不十分清楚,有以下假说:①血管、淋巴管阻塞,曾设想膀胱纤维化是由于盆腔手术或感染引起膀胱壁内淋巴管阻塞和引起栓塞性脉管炎或由于血管炎所致持久性小动脉痉挛所致,但缺乏足够的证据。

②感染,曾提出过细菌、病毒或真菌感染可能是IC的病因,但还没有在IC患者中检出上述3种病原体的报道。

③神经体液因素,肥大细胞在IC病人膀胱固有膜和逼尿肌中增多,寒冷、神经肽、药物、创伤、毒素等可活化肥大细胞,释放血管活性物质可致敏感觉神经元,后者进一步通过释放神经递质或神经肽活化肥大细胞;肥大细胞也可直接引起血管扩张或膀胱黏膜损害引起炎症。

④免疫因素,该病对皮质醇治疗反应良好,部分病人血中可检测到抗膀胱黏膜抗体,不少学者还发现对血管抗原产生的自身免疫性抗体或免疫复合物沉积在血管壁激活补体系统参与了IC发病。

⑤黏膜通透性,推测IC是由膀胱上皮的功能不良引起,其通透性增加并使尿液通过移行上皮漏入到膀胱壁,引起膀胱炎症。

有人证实IC病人膀胱表层上皮内TH蛋白增多,提示黏膜的通透性增加。

二、发病机制间质性膀胱炎为慢性非特异性膀胱全层炎症。

病变早期膀胱扩张时黏膜只见斑点状出血,后期膀胱黏膜变薄或坏死脱落可有典型溃疡,多见于膀胱顶部或前壁。

溃疡底部肉芽组织形成。

周围黏膜水肿、血管扩张。

膀胱内多种药物联合灌注治疗间质性膀胱炎摘要】目的探讨0.2‰呋南西林、地塞米松、利多卡因膀胱灌注治疗间质性膀胱炎(IC)的疗效,安全性及副作用。

方法 12例IC患者采用0.2‰呋南西林200ml、地塞米松5mg、2%利多卡因20ml膀胱灌注,变换体位,保留2h后排空,1次/d,疗程14d,观察患者治疗前症状改善、膀胱容量改变、膀胱镜检变化情况及副作用。

结果症状明显缓解。

膀胱镜检粘膜下点状出血及溃疡消失或改善明显。

膀胱容量明显增加共11例。

随访0.5-2年内复发4例,再次用药均有效改善症状。

结论0.2‰呋南西林、地塞米松、利多卡因膀胱灌注能有效治疗间质性膀胱炎【关键词】间质性膀胱炎呋南西林地塞米松利多卡因膀胱灌注[中图分类号]R694.3 [文献标识码]A [文章编号]1810-5734(2010)6-0058-02间质性膀胱炎(IC)是一种以尿急、尿频、膀胱充盈后耻骨上区或盆腔疼痛,排尿后减轻为表现的临床综合征,其发病机制到目前尚未完全清楚,临床表现缺乏特异性,诊断比较困难和复杂,目前各种治疗方法均无满意效果。

2004年1月至2009年10月,我们共收治间质性膀胱炎12例,以治疗疗效满意,报告如下:1 临床资料12例IC患者,女11例,男1例,年龄31岁至67岁,平均年龄48.4岁,病程5个月至2年,8例主要表现为尿急、尿频等膀胱刺激症状,6例有明显的下腹腹痛或不适,4例出现程度不同的间歇性肉眼血尿,3例以排尿困难为主要表现。

入院前所有患者均运用多种抗生素、黄酮哌酯类、中药等治疗无效。

入院后所有患者均行逆行膀胱造影,显示膀胱容量减小、无输尿管返流。

10例行膀胱镜检查并取活检,其中溃疡型3例,术后病理检查均为IC,另2例因不能耐受而未做检查,9例行尿动力学检查,膀胱容量80-250ml。

2 治疗方法患者采用0.2‰呋南西林200ml、地塞米松5mg、2%利多卡因20ml膀胱灌注,变换体位,采用仰卧、俯卧、左侧卧、右侧卧各30分钟,保留2小时后排空,1次/d,疗程14d。

间质性膀胱炎的治疗方法*导读:间质性膀胱炎是一种比较常见的疾病,尤其是中年妇女,她们是间质性膀胱炎的主要发病群体。

间质性膀胱炎会给患者的生活带来很多影响,所以间质性膀胱炎的治疗方法一直也是广大患者非常关心的一个话题,那么接下来,小编为了让大家更好的了解间质性膀胱炎的相关知识,特意整理了以下信息。

……间质性膀胱炎是一种比较常见的疾病,尤其是中年妇女,她们是间质性膀胱炎的主要发病群体。

间质性膀胱炎会给患者的生活带来很多影响,所以间质性膀胱炎的治疗方法一直也是广大患者非常关心的一个话题,那么接下来,小编为了让大家更好的了解间质性膀胱炎的相关知识,特意整理了以下信息。

间质性膀胱炎会使患者的膀胱壁纤维化,膀胱容量变小,会使患者出现尿频、尿急、夜尿增多的情况。

膀胱充盈的时候耻骨区会有明显的疼痛感,有时也会出现在尿道和会阴部,在排尿之后疼痛感会得到缓解。

所以,间质性膀胱炎给患者的生活带来了很多困扰,那么究竟间质性膀胱炎怎么治疗才好呢?一般采用保守疗法,保守疗法以药物治疗为主,患者可以口服消炎止痛类药物进行缓解症状,或者进行膀胱药物灌注,这些方法都可以患者的症状,明显改善患者的生活质量。

针灸也是治疗间质性膀胱炎的一种主要治疗方法,患者可以去正规的中医医院让专家进行针灸治疗,也能达到一个比较好的效果。

对于间质性膀胱炎症状比较严重的患者,如果保守疗法没有明显的作用,可以考虑采取手术治疗方法,手术治疗是采用经尿道电切术来治疗炎症,可以在很大程度上缓解患者的炎症,但是缺点是比较容易复发。

具体的治疗方法,医生要根据每位病患的具体情况作出分析,才能给出有针对性的治疗方案,所以大家如果对间质性膀胱炎的治疗方法还有更多的疑问,希望大家能够去正规的医院咨询专家,专家会给出有针对性的回答。

最后,小编希望以上内容能够给大家带来一定的帮助,也祝大家早日远离间质性膀胱炎。

得了间质性膀胱炎怎么办

膀胱炎是常见男女泌尿系统疾病,随着现代生活的影响,在近年它的发病率也在逐渐升高。

对于膀胱炎相信大家都很熟悉,但是对于其中一种特殊的慢性膀胱炎,间质性膀胱炎,就不一定熟悉了。

间质性膀胱炎多发于女性,属于一种慢性盆腔疼痛的疾病,会导致患者常常能感到在膀胱和盆腔周围感到疼痛。

间质性膀胱炎的症状,多表现为尿频、尿急、尿痛、夜尿增多,或血尿、耻骨上区疼痛,或有压痛,会阴坠胀,在女性患者阴道前壁触诊时可有膀胱区压痛,会阴疼痛。

或合并肾盂积水。

发病后患者非常痛苦,常常晚上不能睡觉,白天也由于频上卫生间而影响工作。

时间长了,还会导致神经系统等多种疾病的并发症。

对于治疗间质性膀胱炎,应该选择正确的方法,如利尿消炎丸,辩证施治。

1)根据腺性膀胱炎膀胱壁的深层纤维化,可采用活血化瘀,软坚

散结,抗纤维化药物,消除患者的压痛,及坠胀疼痛;

2)根据患者尿频,尿急,尿痛,夜尿多,可采用利尿通淋药物,使小便通畅,如患者伴有肾积水,可以同时消除肾积水;

3)根据膀胱底部或三角区有粘膜下出血,患者有尿血等症状,可以祛淤止血,软坚散结,利尿通淋,治疗血尿。

间质性膀胱炎患者除了要选择正确的方法之外,在平时生活中也应该注意禁忌饮食,有一个良好的心情,并保持积极乐观的心态和良好的生活习惯,这样才更有利于身体健康。

2023中西医结合诊疗间质性膀胱炎专家共识-药物篇推荐的治疗药物阿米替林最佳给药量为每天50mg。

大于100mg 的剂量会增加猝死的相对风险。

近期有心肌梗死(6个月内)后出现长QT综合征、不稳定性心绞痛、充血性心力衰竭、频繁的室性早搏或持续性室性心律失常者应谨慎使用。

证据等级:中,推荐强度:中。

抗组胺药1)羟嗪是组胺H1受体拮抗剂,也具有抗胆碱能特性。

患者每晚睡前口服羟嗪25mg,后可增加到50mg 耐受剂量。

最常见的不良反应是镇静和疲乏;2)西咪替丁是一种H2受体拮抗剂,每天2次,400mg/次。

接受此治疗的患者耻骨上疼痛和夜尿次数明显改善,其作用机制与羟嗪相似。

证据等级:低,推荐强度:弱。

戊聚糖多硫酸钠可修复间质性膀胱炎GAG层的丢失与缺损。

口服治疗剂量为300~600mg。

不良反应轻微,偶有恶心或腹泻。

证据等级:中,推荐强度:中。

可选择的治疗药物槲皮素给予口服槲皮素500mg,2次/d,共4周。

所有患者症状均有改善,且无严重不良反应。

证据等级:中,推荐强度:中。

西地那非每天给予低剂量西地那非25mg,文献证实了西地那非治疗IC/BPS患者的有效性,但尚需进一步实践研究。

证据等级:低,推荐强度:弱。

甲磺司特甲磺司特是治疗IC/BPS患者的常用处方药,每天口服300mg,疗程1年。

患者膀胱容量显著增加,排尿次数减少,疼痛症状减轻。

证据等级:低, 推荐强度:弱。

孟鲁司特每日服用孟鲁司特10mg,3个月为一疗程,治疗1个月显效,24h排尿频率下降,夜尿减少,疼痛减轻,无不良反应。

证据等级:低,推荐强度:弱。

抗生素1)对于从未应用过抗生素治疗的患者,建议可使用抗生素治疗,包括强力霉素、红霉素、甲硝唑、克林霉素、阿莫西林、环丙沙星,疗程为3周;2)对有尿急、尿频和慢性尿道、盆腔疼痛史的妇女,71%的患者应用抗生素治疗后症状有所改善。

因此,经验推荐试用一个疗程的抗生素与其他药物结合治疗IC,也并非不合理。

2022间质性膀胱炎/膀胱疼痛综合征诊治(全文)以非感染性膀胱区疼痛来泌尿就诊的患者是临床工作中遇到最为棘手的问题之一,此类患者多以痛苦不堪的膀胱区疼痛为主诉,多年多次反复多种药物治疗无果,使其生活质量低下,甚至痛不欲生。

如何诊治也让接诊的泌尿外科医师头疼不已,现将目前的诊治进展做一介绍。

一、定义排除炎症、肿瘤、结石等病因引起的慢性膀胱痛,可诊为间质性膀胱炎(interstitial cystitis, IC)/膀胱疼痛综合征(bladder pain syndrome, BPS),伴有肌痛、肠易激惹也是特征之一。

二、流行病学及发病机制因统计学方法不同发病率不统一,真实发病率可能不低,女性高于男性,年龄多在30岁及以上。

发病机制目前仍不明确。

研究发现尿路上皮异常是最为重要的其机制之一,包括:●尿路上皮糖胺聚糖(glycosaminoglycan, GAG)层的完整性改变●膀胱上皮HLA Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型抗原表达改变●尿路上皮特异蛋白(uroplakin)和硫酸软骨素的表达减少●细胞角蛋白表达特点改变(向更符合鳞状细胞特点的方向转变)糖胺聚糖(glycosaminoglycan, GAG)位于尿路上皮层表面,保护尿路上皮层不被尿液溶质渗透,当完整性发生改变导致尿液中的刺激成分渗透膀胱上皮,刺激上皮下神经肌肉组织引起疼痛。

中枢神经敏感化、充盈期膀胱感觉神经元敏感性上调也可能是造成膀胱痛的原因。

三、症状和体征膀胱充盈时持续不适、排尿后缓解是特征性主诉,不适包括疼痛、膀胱区压迫感、痉挛等。

疼痛严重程度不一,症状时好时差,为减轻疼痛需频繁排尿,有时可在进食某类食物或饮料后诱发或加重。

常伴肠易激综合征、外阴痛及肌痛等慢性疼痛症状,男女性患者可出现性功能障碍,此类患者也存在社会心理性问题。

体检发现腹壁、骨盆带、盆底、膀胱底和尿道压痛,男性可有阴囊和阴茎压痛,有时在触碰以上部位时可触发或加重疼痛。

尿液分析无明显异常,尿培养阴性,偶尔会有尿培养阳性。