公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用分析开题报告+任务书+文献综述+翻译文章

- 格式:doc

- 大小:81.00 KB

- 文档页数:10

公允价值计量在我国会计核算中的应用研究(外文翻译参考)毕业设计(论文)外文参考资料及译文译文题目:公允价值会计的危机:正确理解最近的辩论学生姓名:葛慧敏学号: 0901208036 专业:会计学所在学院:商学院指导教师:王思武职称:讲师2013年3月10日The Crisis of Fair Value Accounting: Making Sense ofthe Recent Debate*Christian LauxGoethe-University FrankfurtandChristian LeuzThe University of Chicago Booth School ofBusiness & NBERApril 2009(Forthcoming in Accounting, Organizations andSociety)AbstractThe recent financial crisis has led to a vigorous debate about the pros and cons of fair-value accounting (FV A). This debate presents a major challenge for FV A g oing forward and standard setters’ push to extend FV A into other areas. In this article, we highlight four important issues as an attempt to make sense of the debate. First, much of the controversy results from confusion about what is new and different about FV A. Second, while there are legitimate concerns about marking to market (or pure FV A) in times of financial crisis, it is less clear that these problems apply to FV A as stipulated by the accounting standards, be it IFRS or U.S. GAAP. Third, historical cost accounting (HCA) is unlikely to be the remedy. There are a number of concerns about HCA as well and these problemscould be larger than those with FV A. Fourth, although it is difficult to fault the FV A standards per se, implementation issues are a potential concern, especially with respect to litigation. Finally, we identify several avenues for future research.Key Words: Mark-to-market;Fair value accounting;Financial institutions;Liquidity;Financial crisis;Banks;Procyclicality1. IntroductionThe recent financial crisis has turned the spotlight on fair-value accounting (FV A) and led to a major policy debate involving among others the U.S. Congress, the European Commission as well banking and accounting regulators around the world. Critics argue that FV A, often also called mark-to-market accounting (MTM),1has significantly contributed to the financial crisis and exacerbated its severity for financial institutions in the U.S. and around the world.2On the other extreme, proponents of FV A argue that it merely played the role of the proverbial messenger that is now being shot (e.g., Turner, 2008; Veron, 2008).3In our view, there are problems with both positions. FV A is neither responsible for the crisis nor is it merely a measurement system that reports asset values without having economic effects of its own.In this article, we attempt to make sense of the current fair-value debate and discuss whether many of the arguments in this debate hold up to further scrutiny. We come to the following four conclusions. First, much of the controversy about FV A results from confusion about what is new and different about FV A as well as different views about the purpose of FV A. In our view, the debate about FV A takes us back to several old accounting issues, like the tradeoff between relevance and reliability, which have been debated for decades. Except in rare circumstances, standard setters will always face these issues and tradeoffs; FV A is just another example. This insight is helpful to better understand some of the arguments brought forward in the debate.Second, there are legitimate concerns about marking asset values to market prices in times of financial crisis once we recognize that there are ties to contractsand regulation or that managers and investors may care about market reactions over the short term. However, it is not obvious that these problems are best addressed with changes to the accounting system. These problems could also (and perhaps more appropriately) be addressed by adjusting contracts and regulation. Moreover, the concern about the downward spiral is most pronounced for FV A in its pure form but it does not apply in the same way to FV A as stipulated by U.S. GAAP or IFRS. Both standards allow for deviations from market prices under certain circumstances (e.g., prices from fire sales). Thus, it is not clear that the standards themselves are the source of the problem. However, as our third conclusion highlights, there could be implementation problems in practice. It is important to recognize that accounting rules interact with other elements of the institutional framework, which could give rise to unintended consequences. For instance, we point out that managers’ concerns about litigation could make a deviation from market prices less likely even when it would be appropriate. Concerns about SEC enforcement could have similar effects. At the same time, it is important to recognize that giving management more flexibility to deal with potential problems of FV A (e.g., in times of crisis) also opens the door for manipulation. For instance, managers could use deviations from allegedly depressed market values to avoid losses and impairments. Judging from evidence in other areas in accounting (e.g., loans and goodwill) as well as the U.S. savings and loans (S&L) crisis, this concern should not be underestimated. Thus, standard setters and enforcement agencies face a delicate tradeoff (e.g., between contagion effects and timely impairment).Fourth, we emphasize that a return to historical cost accounting (HCA) is unlikely to be a remedy to the problems with FV A. HCA has a set of problems as well and it is possible that for 3certain assets they are as severe, or even worse than the problems with FV A. For instance, HCA likely provides incentives engage in so called “gains trading” or to securitize and sell assets. Moreover, lack of transparency under HCA could make matters worse during crises.We conclude our article with several suggestions for future research. Basedon extant empirical evidence, it is difficult to evaluate the role of FV A in the current crisis. In particular, we need more work on the question of whether market prices significantly deviated from fundamental values during this crisis and more evidence that FV A did have an effect above and beyond the procyclicality of asset values and bank lending.In Section 2, we provide a quick overview over FV A and some of the key arguments for and against FV A. In Section 3, we discuss the concern that FV A contributes to contagion and procyclicality as well as ways to address this concern, including how current accounting practices help to alleviate problems of contagion. We consider potential implementation problems in Section 4 and conclude with suggestions for future research in Section 5.2. Fair-value accounting: What is it and what are the key arguments?FV A is a way to measure assets and liabilities that appear on a company’s balance sheet. FAS 157 defines fair value as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.” When quoted prices in active markets for identical assets or liabilities are available, they have to be used as the measurement for fair value (Level 1 inputs). If not, Level 2 or Level 3 inputs should be used. Level 2 applies to cases for which there are observable inputs, which includes quoted prices for similar assets or liabilities in active markets, quoted prices from identical or similar assets in 4inactive markets, and other relevant market data. Level 3 inputs are unobservable inputs (e.g.,model assumptions). They should be used to derive a fair value if observable inputs are not available, which is commonly referred to as a mark-to-model approach.Fair value is defined similarly under IFRS as the amount for which an asset could be exchanged, or a liability settled, between knowledgeable, willing parties, in an arm’s length transaction. In determining fair value, IFRS make similardistinctions among inputs as FAS 157: Quoted prices in active markets must be used as fair value when available. In the absence of such prices, an entity should use valuation techniques and all relevant market information that is available so that valuation techniques maximize the use of observable inputs (IAS 39). It is recognized that an entity might have to make significant adjustments to an observed price in order to arrive at the price at which an orderly transaction would have taken place (e.g., IASB Expert Advisory Panel, 2008).3. Fair-value accounting, illiquidity, and financial crisesFV A and its application through the business cycle have been subject to considerable debate (e.g., ECB, 2004; Banque de France, 2008; IMF, 2008). The chief concern is that FV A is procyclical, i.e., it exacerbates swings in the financial system, and that it may even cause a downward spiral in financial markets. U.S. GAAP and, more recently, also IFRS allow for a re-classification of fair-value assets into a category to which HCA and less stringent impairment tests apply. U.S. GAAP and IFRS have mechanisms to avoid negative spillovers in distressed markets and a downward spiral.To address contagion and procyclicality is not to have direct (mechanical) regulatory or contractual ties to FV A. For instance, it would be possible to adjust the accounting numbers for the purpose of determining regulatory capital. Such adjustments already exist. For example, for the purpose of calculating regulatory capital, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Federal Reserve adjust bank’s equity as reported under U.S. GAAP for unrealized losses and gains for available-for-sale (AFS) debt securities to obtain Tier 1 capital (e.g., Schedule HC-R in FR Y-9C). Thus, regulatory capital as calculated by U.S. banking regulators is not affected by changes in the fair value of AFS debt securities, unless they are sold or the impairments are other-than-temporary.13Similarly, Li (2008) documents that debt contracts often exclude fair-value changes in accounting-based debt covenants. These examples demonstrate that it is not clear that contagion and procyclicality are bestaddressed directly in the accounting system. Perhaps these issues are better left to the prudential regulators and contracting parties, who in turn can make adjustments to the numbers reported in the financial statements as they see fit. In our view, this is an interesting issue for future research. In summary, Allen and Carletti (2008) and Plantin et al. (2008a)provide important contributions to the FV A debate by illustrating potential contagion effects. However, they do not show that HCA would bepreferable. In fact, Plantin et al. (2008a) are quite explicit about the problems of HCA. Furthermore, they do not speak directly to the role of FV A in the current crisis because they do not model FV A as implemented in practice. As noted above, FV A as required by U.S. GAAP or IFRS as well as U.S. regulatory capital requirements for banks have mechanisms in place that should alleviate potential contagion effects. Whether these mechanisms work properly in practice is our next question.4. Are there implementation problems with fair-value accounting standards?Given the discussion in the preceding section, it is not obvious that extant accounting standards can be blamed for causing contagion effects. But it is possible that, in practice or in crises, the standards do not work as intended. Ultimately, this is an empirical question and answering it is beyond the scope of this article. But we can at least raise and discuss two important implementation issues.Many have argued that both the emphasis of FAS 157 on observable inputs (i.e., Level 1 and Level 2) and extant SEC guidance make it very difficult for firms to deviate from market prices, even if these prices are below fundamentals or give rise to contagion effects (e.g., Wallison, 2008a, Bigman and Desmond, 2009). Consistent with these claims, the relevant standards in U.S. GAAP and IFRSas well as guidance for these standards are quite restrictive as to when it is appropriate for managers to deviate from observable market prices.However,such restrictions should not be surprising. By allowing deviations from market price in some instances, standard setters face the problem of distinguishing between a situation in which a market price is indeed misleading and a situation in which a manager merely claims that this is soin order to avoid a write-down. Without restrictive guidance, the standards could be easily gamed. There is evidence that managers can be reluctant to take write-downs even when assets are substantially impaired.15Consistent with this concern, current estimates of banks’ loan losses far exceed the write-downs that banks have taken so far and they also exceed the difference between the loans’ carrying valu es and banks’ fair value disclosures for these loans according to FAS 107 (e.g., Citigroup, 2009; Goldman Sachs, 2009; IMF, 2009).16 While this expected feature of second-best standards is one explanation for the criticism of FV A during the crisis, it is clearly also possible that extant rules and guidance are too restrictive (even from a second-best perspective) and that we would have been better off giving managers more flexibility in the crisis.17This is in essence the view that the House Financial Services Committee adopted in a hearing on MTM accounting rules on March 12, 2009. As a result of this political pressure, the FASB relaxed the conditions for moving assets into Level 3 in April 2009. Moreover, the financial statements of U.S. banks for fiscal 2008 show that banks have been able to move assets into the Level 3 Category as the financial crisis unfolded, so it was clearly not impossible to move to models (see also IMF, 2008). But it is of course possible that banks did not move enough assets into the Level 3 category to prevent contagion effects. In the end, we need more research on this issue.18A second implementation problem may arise from litigation risk. Deviations from market prices under existing FV A standards require substantial judgement by the preparers and the auditors. However, managers, directors and auditors face severe litigation risks as well as substantial legal penalties, including prison terms, which recently have been increased by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. In this environment, managers, directors, and auditors are likely to weigh thepersonal costs and risks associated with deviations from market prices differently than investors. For example, it is conceivable that a manager is reluctant to use an appropriate model-based fair value that is higher than an observable price from a very illiquid market, especially when there is substantial down-side risk for the economy or the firm, as there typically is in financial crises.From a litigation risk perspective, guidance as to when deviations are appropriate is likely to play an important role, especially in litigious environments and when enforcement is strong. Thus, it is possible that, once we recognize the litigation aspect, improvements in the standards’ implementation were (and perhaps are still) needed. However, as litigation serves as an important enforcement mechanism, there are tradeoffs as we highlighted earlier in this section for SEC enforcement. This second implementation problem also highlights that it is important to evaluate accounting standards within the context of the institutional environment in which they operate.195、Conclusion and suggestions for future researchThe preceding sections illustrate that the debate about FV A is full of arguments that do not hold up to further scrutiny and need more economic analysis. Moreover, it is important to recognize that standard setters face tradeoffs, and in this regard FV A is no exception. One example is the tradeoff between relevance and reliability, which is at the heart of the debate of when to deviate from market prices in determining fair values. Another example is that FV A recognizes losses early thereby forcing banks to take appropriate measures early and making it more difficult to hide potential problems that only grow larger and would make crises more severe. But this benefit gives rise to another set of tradeoffs. First, FV A introduces volatility in the financial statement in “normal times” (when prompt action is not needed). Second, full FV A can give rise to contagion effects in times of crisis, which need to be addressed – be it in the accounting system or with prudential regulation. In our view, it may bebetter to design prudential regulation that accepts FV A as a starting point but sets explicit counter-cyclical capital requirements than to implicitly address the issue of financial stability in the accounting system by using historical costs. It is an illusion to believe that ignoring market prices or current information provides a foundation for a more solid banking system. But we admit that the tradeoff between transparency and financial stability as well as the interactions between accounting and prudential regulation needs further analysis (see also Landsman, 2006).A related issue is the question of how investors respond to additional disclosures that firms provide in times of crisis. There are a few studies that examine firms’ responses to transparency crises and their economic consequences (e.g., Leuz and Schrand, 2008). The current crisis provides an interesting setting to further explore these issues further. An analysis of European banks’ annual reports by KPMG (2008) suggests that, in 2007, banks increased their disclosures related to financial instruments, in part due to the beginning of the crisis. It would be interesting to study what determines disclosure (or non-disclosure), how investors reacted to these disclosures and whether there are signs that investors overreact to such disclosures.Finally, it is important to recognize that accounting rules and changes in them are shaped by political processes (like any other regulation). The role of the political forces further complicates the analysis. For instance, it is possible that changing the accounting rules in a crisis as a result of political pressures leads to worse outcomes than sticking to a particular regime (e.g., Brunnermeier etal., 2009). In this regard, the intense lobbying and political interference with the standard setting process during the current crisis provide a fertile ground for further study.In sum, the fair-value debate is far from over and much remains to be done. ReferencesAdrian, T., & Shin, H.S. (2008). Liquidity and leverage. Federal Reserve Bank ofNew York Staff Reports, No. 328.Allen, F., & Carletti, E. (2008). Mark-to-market accounting and liquidity pricing. Journal of Accounting and Economics45, 358-378.American Bankers Association (2008). Letter to SEC. September 23, 2008.Ball, R. (2008). Don’t shoot the messenger … or ignore the message, Note.Bank of America (2004). Letter to FASB. September 17. 2004.Banque de France (2008). Financial stability review. Special issue on valuation, No 12, October.Barberis, N., & Thaler, R. (2003). A survey of behavioral finance. In G.M. Constantinides, M. Harris, & R. M. Stulz, Handbook of the Economics of Finance, vol. 1, chapter 18, pages 1053-1128. North Holland, Amsterdam: Elsevier.Barth, M. (2004). Fair Values and Financial Statement Volatility. In: The Market Discipline Across Countries and Industries, Claudio Borio, William Curt Hunter, George G Kaufman, and Kostas Tsatsaronis (eds). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.Barth, M.E., Beaver, W.H., & Landsman, W.R. (2001). The relevance of the value-relevance literature for financial accounting standard setting: another view. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31, 77-104.Beatty, A., Chamberlain, S. & Magliolo, J. (1995). Managing financial reports of commercial banks: The influence of taxes, regulatory capital and earnings. Journal of Accounting Research33, 231-261.Beaver, W.H. (1981). Financial reporting: An accounting revolution. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Benston, G. J. (2008). The shortcomings of fair-value accounting described in SFAS 157. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 27, 101-114.Berger, A.N., Herring, R.J., & Szegö, G.P. (1995). The role of capital in financial institutions. Journal of Banking and Finance19, 393-340.Bernard, V.L., Merton, R.C., & Palepu, K.G. (1995). Mark-to-market accountingfor banks and thrifts: Lessons from the Danish experience. Journal of Accounting Research 33, 1-32.Bigman, D., & Desmond, M. (2009). Mark-to-messy accounting change. , April 02, 2009.Brunnermeier, M.K., & Pedersen, L.H. (forthcoming). Market liquidity and funding liquidity. Review of Financial Studies.Brunnermeier, M.K., Crocket, A., Goodhart, C., Persaud, A. & Shin, H. (2009). The fundamental principles of financial regulation. Geneva Reports on the World Economy 11. International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies. Geneva, Switzerland.Citigroup (2009). Industry focus: U.S. Banks, Research report by Citigroup Global Markets, March 2, 2009.Credit Suisse (2008). Letter to the SEC, File Number 4-573, November 13, 2008. Coval, J.D., Jurek, J.W., & Stafford, E. (2009). The pricing of investment grade credit risk during the financial crisis. Working Paper.DeBondt, W.F.M., & Thaler, R. (1985). Does the stock market overreact? The Journal of Finance40, 793-805.Disclosure Insight (2009). Comment letter on proposed staff position under FASB Statement No. 157, Fair Value Measurements, March 25, 2009.ECB (2004). Fair value accounting and financial stability. By ECB staff team led by A. Enria. Occasional Paper Series, No. 13, April 2004.公允价值会计的危机:正确理解最近的辩论作者:Christian Laux and Christian Leuz出处:Forthcoming in Accounting,Organizations and Society摘要最近的金融危机已经导致了一个关于公允价值会计的优缺点(FVA)的激烈争论。

公允价值中英文对照外文翻译文献(文档含英文原文和中文翻译)原文:Fair Value is here to stayThe fair value guidance in SFAS 157 Fair Value Measurements, does not represent, as many perceive, a radical departure from previous accounting rules. SFAS 157 is the result of a natural evolution that has been taking place for more than 30 years. SFAS 157 is the result of anatural evolution that has been taking place for more than 30 years.Many who oppose SFAS 157 do so because of the current economic environment. This current economy, during which many hedge funds and other institutional investors face significant other-than-temporary write-downs on illiquid assets, is, however, an anomaly. Any valuation method that does not require significant write-downs in the current environment would fail to provide a reasonable representation of fair value for those illiquid assets.When it was introduced in 2007, SFAS 157 amended, deleted, or otherwise affected more than 40 areas of accounting guidance, including SFAS 13, Accounting for Leases. SFAS 13, issued in 1976, introduced the fair value concept when it described an asset being sold in an "arm's length transaction between unrelated parties." Since then, the accounting framework has continued to move away from a historical cost model and toward a fair value model.Throughout this transition, accounting standards were issued that discussed fair value in different contexts. SFAS 157 was designed primarily to provide a uniform definition of fair value and a universal measurement framework. Contrary to popular perception, SFAS 157 does not require any new items to be measured at fair value; it specifies the framework to be used wherever other standards require that items be measured at fair value.Along the WayMany accountants were educated during an era when colleges taught the tenets of historical cost as part of the fundamental framework of accounting. To those watching the fair value model slowly supplant the cost model during the past 30 years, it may seem like a dramatic change in thinking has recently occurred, but much of this shift is attributable to the ongoing development of accounting standards and rules, rather than a change in approach.To those watching the fair value model slowly supplant the cost model during the past 30 years, it may seem like a dramatic change in thinking has recently occurred, but much of this shift is attributable to the ongoing development of accounting standards and rules, rather than a change in approach. Prior to SFAS 87,Accounting for Pensions, and SFAS 106, Employers' Accounting for Postretirement Benefits Other Than Pensions, many companies paid for these benefits on a pay-as-you go cash basis, with little attention given to the fair value of the plan assets that were needed to be set aside to cover the cost of such benefits or how to account for them on an accrual basis. SASs 87 and 106 required companies for the first time to factor in the fair value of plan assets when determining their benefit obligations.The next sweeping implementation of fair value took place when companies began to adopt SFAS 133, Accounting for Derivatives and HedgingActivities, in 1999. Prior to SFAS 133, companies were not required to put all derivatives on their balance sheet at fair value; derivatives were not even defined in the literature. For the first time, complex financial instruments, many of which were involved in hedging relationships, were subject to fair valuation. Soon after, SFAS 140, Transfers of Financial Assets, gave rise to difficult-to-value seductive financial assets, such as residential and commercial mortgage-hacked securities RMBS and CMBS, which in turn gave rise to collateralized debt obligationsCDO and other financial instruments. A barrage of valuation techniques based on higher math designed to account for securitization followed.SFAS 157 had a significant impact on fair value accounting for illiquid securities, which are typically among the most difficult assets to value. Prior to SFAS 157, companies often cherry-picked information to support valuations for illiquid positions, regardless of accuracy. Now, they are required to consider all "reasonably available" information and use the best data available to support their market assumptions and parameters.Even though SFAS 157 has been in effect for more than a year, many illiquid assets are still being valued based on previous methodologies that are clearly inaccurate.Today's EnvironmentIn the current economic environment, air value accounting facesintensified scrutiny, challenging situations, and significant opposition. Attention is especially focused on three areas:? Other-than-temporary write-downs,? Fresh-start accounting, and? Illiquid securities.Other-than-temporary write-downs.With Level 1 securities, determining when to record an other-than-temporary impairment can he as straightforward as deciding how much time has passed since an impairment began. When the tech bubble burst, for example, companies often realized after six to nine months that asset values weren't going to recover any time soon, if at all.But what about Level 2 or Level 3 assets that are valued using sophisticated modeling techniques? Prior to SFAS 157, companies and their auditors might have agreed to hold off or postpone making an adjustment, due to a lack of relevant and reliable information. SFAS 157 has driven companies to consider new types and sources of information, and to work harder to support valuations for Level 2 and Level 3 assets. Companies are now expected to support their Level 2 and Level 3 assets almost as if they were Level I assets.In evaluating goodwill for other-than temporary impairment, SFAS 157 suggests that a publicly traded stock price, if available, is the best indicator of fair value. But even when a stock price is available, other,more traditional methods of fair value, such as discounted cash flow, must also be considered. The challenge lies in supporting these other methods in the current environment of declining prices.With the release of FASB Staff Position FSP FAS 1 15-2 and FAS 124-2,Recognition and Presentation of Other-Than-Temporary Impairments, in April 2009, companies are able to bifurcate certain losses on debt securities classified as held-to-maturity or available-for-sale between the portion related to credit conditions and the portion related to noncredit conditions. The noncredit portion will be recognized on the balance sheet until the debt security matures or is sold. In many situations, the amount reclassified to the balance sheet will include losses previously recognized in other periods. This new rule has caused controversy among practitioners and standards setters, primarily because it delays the inevitable recognition of those losses in earnings when the debt security is sold or matures.Fresh-start accounting Companies petitioning for Chapter 11 bankruptcy need to know whether they will qualify for fresh start accounting based on their reorganization value according to the provisions of AICPA Statement of Position SOP 90-7, Financial Reporting by Entities in Reorganization Under the Bankruptcy Code.SOP 90-7 provides a two-step test. The first step requires a comparison of reorganization value with the value of postposition claimsand obligations immediately prior to court confirmation. This balance sheet solvency test is a moving target throughout a bankruptcy proceeding, because there may be large fluctuations in reorganization value and claims until the plan is implemented. The second step requires that holders of existing common shares immediately before court confirmation have, as a group, less than 50% of the new company's shares upon emergence from bankruptcy. The challenge here involves the negotiations that take place between debtor and creditor committees and the company, which are then subject to final court approval.Illiquid securities. When determining fair value, companies must consider the frequency with which securities are traded. Fair value is more readily supportable for a frequently traded security than for one that is thinly traded because SFAS 157 emphasizes the importance of observable prices.Today, a company's desire to hold a position, together with its requirement to value that position, is causing a unique anomaly in the valuation world, as securities that would otherwise trade normally are increasingly subject to write-downs. A good valuation model must take into account all facts and circumstances. For example, when the market is dry for a specific illiquid security, the valuation methodology must consider any widening credit spreads, liquidity premiums from the time of the last active trading activity to the then-current indications, and discountrates implicit in nonbinding broker quotes.With the finalization in April 2009 of FSP FAS 157-4, Determining Fair Value When the Volume and Level of Activity for the Asset or Liability Have Significantly Decreased and Identifying Transactions that Are Not Orderly, companies are now subject to additional disclosure requirements and must carefully support how observable prices from inactive markets areused in valuations. Companies may also need to explain significant differences between different inputs to value.FSP FAS 157-4 did not come about without opposition; it generated nearly 400 comment letters within a short period. The author is not aware of any other proposed accounting rule that generated so many comment letters within such a short time and that underwent such a drastic turn around before being finalized.Tomorrow's EnvironmentU.S. companies are facing a seemingly inevitable changeover to International Financial Reporting Standards IFRS. Fair value guidance under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles GAAP is primarily rules-based, while fair value guidance under IFRS is based on principles. Principles often evolve into rules, but, in this case, rules appear to be reverting back to their origin as principles.Fair value guidance under SFAS 157 and íFRS are different inseveral respects. For example, IFRS does not define the term "market participants," does not include the concepts of principal market or "highest and best use," and does not generally permit imaret pricing. While there will be convergence to eliminate many differences, companies will need to embrace and understand the principles based approach behind IFRS.Fair value will continue to generate challenges for accountants, especially if and when IFRS is adopted. The sooner companies come to grips with the impact of fair value accounting, the better, because fair value is here to stay.翻译:公允价值仍留在此处在美国财务会计准则委员会《财务会计准则公告第157号公允价值计量》(SFAS 157)的指导下,公允价值计量,并不代表尽可能多的感知,与以前的会计准则大相径庭。

公允价值计量的应用研究文献综述作者:蔡军莫海玲来源:《价值工程》2019年第34期摘要:随着市场经济的发展,公允价值的应用深受广泛关注,由于我国市场条件不够成熟,采用公允价值计量相关资产时会存在很多争议,投资性房地产采用公允价值后续计量是其中一个争议问题。

文章以公允价值和投资性房地产的概念框架为基础,梳理了国内外对公允价值计量的研究及投资性房地产采用公允价值计量模式研究文献,分析了我国投资性房地产采用公允价值计量的现状,最后提出了完善我国投资性房地产采用公允价值计量的建议。

Abstract: With the development of market economy, the application of fair value has been widely concerned. As China's market conditions are not mature enough, there will be many controversies when using fair value to measure related assets. The subsequent measurement of investment properties using fair value is one of the controversial issues. Based on the conceptual framework of fair value and investment real estate, this paper sorts out the research on fair value measurement at home and abroad and the research literature on fair value measurement model of investment real estate, and analyzes the current situation of fair value measurement of investment real estate in China. Finally it makes suggestions to improve the adoption of fair value measurement in China's investment real estate.关键词:公允价值计量;投资性房地产;文献综述Key words: fair value measurement;investment real estate;literature review中图分类号:F233;F293.3; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ;文献标识码:A; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; 文章编号:1006-4311(2019)34-0287-030; 引言随着经济全球化的发展,近年来,我国房地产的市场价格迅猛增长,尤其是发达地区,使用最广泛的成本计量模式遇到很大的挑战,很多弊端突显出来,因为成本模式计量投资性房地产不符合现在的市场条件,脱离实际。

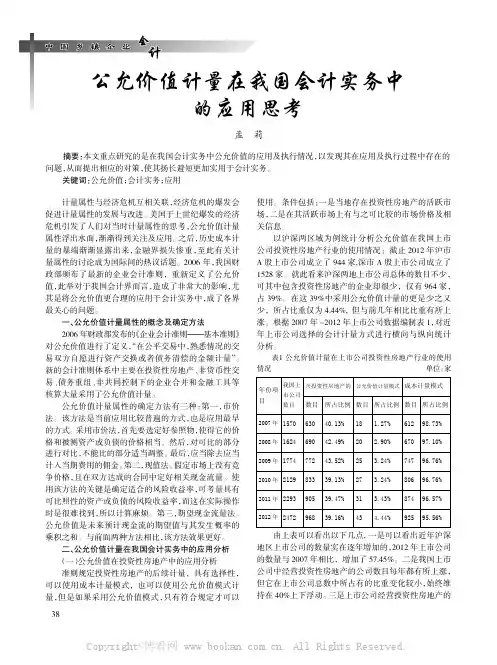

年份项目我国上市公司数目含投资性房地产的公允价值计量模式成本计量模式数目所占比例数目所占比例数目所占比例2007年157063040.13%18 1.27%61298.73%2008年162469042.49%20 2.90%67097.10%2009年177477243.52%25 3.24%74796.76%2010年212983339.13%27 3.24%80696.76%2011年229390539.47%31 3.43%87496.57%2012年247296839.16%434.44%92595.56%公允价值计量在我国会计实务中的应用思考孟莉摘要:本文重点研究的是在我国会计实务中公允价值的应用及执行情况,以发现其在应用及执行过程中存在的问题,从而提出相应的对策,使其扬长避短更加实用于会计实务。

关键词:公允价值;会计实务;应用计量属性与经济危机互相关联,经济危机的爆发会促进计量属性的发展与改进。

美国于上世纪爆发的经济危机引发了人们对当时计量属性的思考,公允价值计量属性浮出水面,渐渐得到关注及应用。

之后,历史成本计量的暴端渐渐显露出来,金融界损失惨重,至此有关计量属性的讨论成为国际间的热议话题。

2006年,我国财政部颁布了最新的企业会计准则,重新定义了公允价值,此举对于我国会计界而言,造成了非常大的影响,尤其是将公允价值更合理的应用于会计实务中,成了各界最关心的问题。

一、公允价值计量属性的概念及确定方法2006年财政部发布的《企业会计准则———基本准则》对公允价值进行了定义,“在公平交易中,熟悉情况的交易双方自愿进行资产交换或者债务清偿的金额计量”。

新的会计准则体系中主要在投资性房地产、非货币性交易、债务重组、非共同控制下的企业合并和金融工具等核算大量采用了公允价值计量。

公允价值计量属性的确定方法有三种:第一,市价法。

该方法是当前应用比较普遍的方式,也是应用最早的方式。

采用市价法,首先要选定好参照物,使得它的价格和被测资产或负债的价格相当。

本科毕业设计(论文)开题报告题目公允价值在我国应用的探讨学院商学院专业会计学班级会计071学号学生姓名指导教师完成日期 2010-01-08一、论文选题的背景、意义(一) 选题背景随着市场经济和知识经济的发展,历史成本遭到越来越多的批评。

在这个过程中,能及时全面地反映未来经济环境变化的公允价值应运而生。

20世纪70年代以来,公允价值一直是国际会计界的一个热点问题,至今已取得了许多显著的研究成果,并逐渐成为国际会计准则的重要组成部分。

而在我国,自1998年公允价值首次出现在具体会计准则中,便也成为了倍受瞩目的一个会计问题。

国内学者通过对发达国家公允价值会计理论的借鉴及我国在有限范围内应用经验的总结,发表了一些文献,加深了我国财会人员对公允价值计量属性的认识并促进了公允价值在我国应用的进度。

然而随之而来的许多利用公允价值操纵利润的造假案使得我国不得不对公允价值的应用采取认真和谨慎的态度,在有些准则中甚至明确回避了公允价值计量。

进入21世纪,随着经济全球一体化和国际资本市场的发展,以及会计准则国际趋同步伐的加快。

在国际上对公允价值会计的研究己由是否需要采用转向了如何运用方面,此时再选择回避公允价值的做法已明显不合时宜。

2006年2月,财政部在新颁布的《企业会计准则——基本准则》中增加了公允价值这一计量属性,在具体准则中,公允价值也得到了全面的体现。

目前我国对公允价值的研究主要在:公允价值计量属性和计量方法的研究;公允价值在我国应用的研究。

对于公允价值计量属性和计量方法的研究我国已经有了不错的研究成果,但是对于公允价值在我国应用的问题还是存在较大争议:公允价值是否该取代历史成本以及如何合理地取得、应用公允价值一直是争议的焦点。

2008年全球金融危机的爆发,促进了全球会计准则的国际化进程,我国也在积极响应这一号召,学者们对于公允价值计量属性在我国应用的问题已经进行了广泛的研究,但这一课题的研究随着经济形势的变化,需要不断补充和完善。

会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题探析【摘要】本文主要探讨了会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题。

在介绍了研究背景、研究目的和研究意义。

在首先解释了公允价值计量的基本概念,然后讨论了公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用以及带来的挑战。

接着探讨了会计实务中公允价值计量的问题,并展望了公允价值计量的未来发展。

在总结了研究的重要发现,并对未来的研究方向进行了展望。

本文旨在提高对公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用问题的认识,为相关研究提供参考依据。

【关键词】公允价值计量、会计实务、问题探析、挑战、发展、未来、总结、展望、研究结论、研究不足、研究背景、研究目的、研究意义。

1. 引言1.1 研究背景公允价值计量的引入,旨在提高会计信息的质量和透明度,从而更好地反映企业的真实财务状况。

公允价值计量在实践中也带来了一系列的问题和挑战,包括公允价值计量的主观性、难以确定的市场价格以及会计师对公允价值的理解和应用等方面。

对会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题进行深入的探讨,不仅有助于揭示公允价值计量的实质和特点,促进财务报告的透明度和真实性,更有利于指导企业在具体的会计处理中更加准确和合理地运用公允价值计量方法。

本文旨在对公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用问题进行更深入的分析和探讨,为相关研究和实践提供有益的参考和建议。

1.2 研究目的研究目的是通过对公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用问题进行深入分析和探讨,旨在揭示公允价值计量对会计信息质量、透明度和可比性所带来的影响,以及在实际操作中可能存在的挑战和问题。

通过对公允价值计量的基本概念和会计实务中的具体应用进行研究,探讨其中可能存在的不足和改进方向,为相关政策制定和会计实践提供参考。

本研究旨在为会计领域学术界和从业者提供对公允价值计量的更深入了解和思考,为其在实践中正确应用公允价值计量提供理论基础和指导。

通过研究公允价值计量的未来发展趋势,希望能够为会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题提出建设性的建议和展望,促进会计理论和实践的进步和发展。

公允价值计量在会计实务的运用一、前言从我国不断发展的会计信息化程度来看,会计实务中公允价值计量也越来越重要,逐步成为会计工作中的重要组成部分,公允价值应用在会计实务中,能够有效的提高会计实务的水平,逐渐提高会计信息的应用型,促进企业经济效益的快速增长,并能够为企业降低财务风险。

因此,在会计实务中有效合理的运用公允价值计量对于整个会计工作来说是具有重要意义的。

但是目前在我国会计核算中,会计准则尚不完善,公允价值计量在会计实务操作中的运用效果并不明显,其中就存在着一些公允价值计量的问题,这对会计实务效果也产生一定的影响。

因此,必须提高会计实务中公允价值计量的应用型,高质量的完成会计实务操作,为企业提供良好的发展。

二、会计实务中公允价值计量的应用价值分析(一)强化会计信息的及时性和相关性所谓的公允价值主要是指在市场交易的过程之中,以公平、自愿的原则对商品以及资产实施价格交换。

在会计实务之中,应用公允价值计量可以真实的反映企业的资产、负债、现金流等方面的会计信息,从而向企业提供全面的、及时的会计信息,为企业做出正确的战略决策提供条件。

这表明,在会计实务之中将公允价值计量有效的应用其中能够大大的强化会计信息的及时性、相关性。

(二)客观确认会计收益促进企业良好发展,需要企业客观的、真实的、合理的掌握企业资产情况和负债情况,如此企业才能制定合理的经营决策,降低财务风险,有效落实经营活动,促进企业良好发展。

公允价值计量的实施,可以对企业资产和负债情况进行计量,促使企业财务状况清晰化、真实化,为企业经济效益分析提供依据。

所以,会计实务中公允价值计量的实施,可以客观确认会计收益。

三、公允价值应用必要性(一)适应金融创新的需要随着金融业的不断发展和创新,金融市场上的金融工具及其衍生品大多数都是以合约的形态存在的,这些虚拟金融产品和工具并不具有实物形态,也不具有货币形态,就使得历史成本法在计算这些产品的价值时遇到了困难,在这种情况下就可以采用公允价值法进行处理,即当交易双方共同确定一个价格或价值,就完成了价值确定的过程,而且对于没有真实发生的金融业务也是适用的,以此来反映金融衍生工具产生的权利和义务,向信息使用者提供信息。

会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题探析【摘要】本文旨在探讨会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题。

首先介绍了公允价值计量的基本概念,然后分析了会计准则对公允价值计量的规定。

接下来重点探讨了公允价值计量在会计实务中可能存在的问题和挑战,以及可能的改进方法。

指出对公允价值计量的应用进行深入研究的必要性,并展望了未来的研究方向。

通过本文的研究,有助于提高对公允价值计量的理解,及时解决相关问题,促进会计实务的规范和完善。

【关键词】公允价值计量、会计准则、会计实务、应用问题、挑战、改进方法、研究、结论、深入研究、未来研究方向、总结。

1. 引言1.1 研究背景公允价值计量在会计准则中得到了重要的规定和指导,而在实际应用中也存在着一些问题和挑战。

公允价值计量在不同市场环境下可能会产生不确定性,同时也可能受到市场操纵和信息不对称的影响。

这些问题不仅影响了会计信息的准确性和可靠性,也对企业的财务管理和决策产生了重要影响。

对公允价值计量的应用问题进行深入研究,探索其中存在的挑战和改进方法,具有重要的理论和实践意义。

为了更好地应对未来不确定的经营环境和挑战,有必要对公允价值计量的应用进行进一步的研究和探讨。

1.2 研究意义会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题探析研究公允价值计量的应用问题还有助于揭示会计准则在实践中的应用情况,可以为相关立法和监管提供重要参考依据,推动会计理论和实务的不断完善与发展。

对公允价值计量进行深入研究,有助于探讨其在不同行业和情况下的适用性和局限性,进一步完善会计信息披露的透明度和准确性,从而提高会计信息的质量和可靠性,为投资者、债权人等利益相关方提供更好的决策依据。

对公允价值计量的应用问题进行探讨与研究具有重要的现实意义和学术价值,对于推动我国会计理论与实践的发展具有重要意义。

2. 正文2.1 公允价值计量的基本概念在会计实务中,公允价值是指基于市场上能够达成的充分理性的协商,以知识、情报和经验作为前提,表达的交易当事人之间的资产、负债或权益的价格。

会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题探析【摘要】本文探讨了会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题。

首先从研究背景和研究意义入手,分析了公允价值计量与会计实务的关系。

接着探讨了公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用,以及其优势和局限性。

进一步讨论了公允价值计量在各个领域的具体应用情况,并指出了其存在的问题及解决对策。

最后通过总结对会计实务中公允价值计量的应用,展望了未来的发展方向。

通过本文的研究,可以更深入地了解公允价值计量在会计实务中的重要性和应用问题,为相关领域的从业人员提供参考和启示。

【关键词】公允价值计量、会计实务、应用问题、优势、局限性、具体应用、问题解决、总结、发展方向、研究背景、研究意义、关系、结论。

1. 引言1.1 研究背景公允价值计量在会计领域中扮演着重要的角色,随着国际会计准则的不断完善和国内会计实务的日益规范,公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用也逐渐受到关注。

在实际操作中,公允价值计量也面临着许多挑战和争议。

为了更好地理解和探索公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用问题,本文将深入分析公允价值计量与会计实务的关系,探讨公允价值计量在会计实务中的具体应用,评述公允价值计量的优势和局限性,阐述公允价值计量在各个领域的应用情况,并对公允价值计量存在的问题提出解决对策。

通过对会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题进行探索和研究,可以帮助企业更好地理解和把握公允价值计量的相关规定,提高财务报表的透明度和可比性,为投资者和利益相关方提供更加准确和全面的财务信息,促进企业健康可持续发展。

对会计实务中公允价值计量的应用问题进行深入探究具有重要的理论和实践意义。

1.2 研究意义公允价值计量在会计实务中的应用问题一直备受关注,其研究意义主要体现在以下几个方面:1. 对企业决策的指导作用:公允价值计量能够提供更为准确和及时的财务信息,帮助企业管理层做出更明智的经营决策。

通过对资产和负债的公允价值进行计量,可以更好地反映资产和负债的真实价值,减少信息误差,提高决策的准确性和效率。

南京审计学院金审学院本科生学年论文题目:关于公允价值应用探讨的文献综述姓名:张三学号:********* 专业:财务管理指导教师:孙国岩职称:讲师二0一一年十月关于公允价值基本问题的文献综述06020714 06中澳1班解清莲【摘要】公允价值问题是近年来会计前沿中的热点和难点问题。

当前,在会计准则制定上,无论是美国的财务会计准则委员会(FASB),还是国际会计准则理事会(IASB),都正在由传统的历史成本会计向公允价值会计转变。

我国的新会计准则大量地引入了公允价值计量属性,在与国际准则趋同的过程中迈出了实质性的一步。

本文从公允价值的理论基础、定义、计量属性、应用研究四方面对相关文献进行了综述,并提出了一些自己的观点。

【关键词】公允价值计量属性可靠性相关性Abstract:Fair value has been one of the hot issues and tough questions in accounting research in recent years. At present, both the United States Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) support the change from traditional historical cost accounting to fair value accounting . China's new accounting standards also accept the fair value as a measurement attribute, and it is a substantial step to the trend of international accounting standards. This article sums up people’s views about the theoretical basis of fair value ,the definition of fair value, the measurement attributes of the fair value as well as the application and research of fair value, and also includes my own opinion.Keyword: fair value measurement attributes reliability relevance公允价值会计于20世纪80年代在美国产生。