英语文体学ppt-Varieties in relation to attitude

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:1.91 MB

- 文档页数:45

A brief summaryStylistics is a newly-born study, it was in the 1960s that stylistic study really began to flourish in Great Britain and the United States. Professor Wang Zuoliang is the first person in China to study it.The stylistics we are discussing here is Modern Stylistics, a discipline that applies concepts and techniques of modern linguistics to the study of styles of language use. It has two subdivisions: General Stylistics and Literary Stylistics, with the latter concentrating solely on unique features of various literary works, and the former on the general features of various types of language use.1.2.1 Speech Acts1.2.2 Speech Events1.2.3 Text / Message / Discourse1. Substantial2. Formal3. SituationalIt is this contextual relationship between the substance and form of a speech event on the one hand and the situation in which it occurs on the other, which gives what is normally called “meaning” to utterance. In other words, context determines meaning of features in situation.e.g.My beloved grandfather has just passed to his heavenly reward.My dear grandfather has just expired.My grandfather has just passed away.My grandfather has died.同是表达“死”这个概念,但场合不同,表达方式也不同。

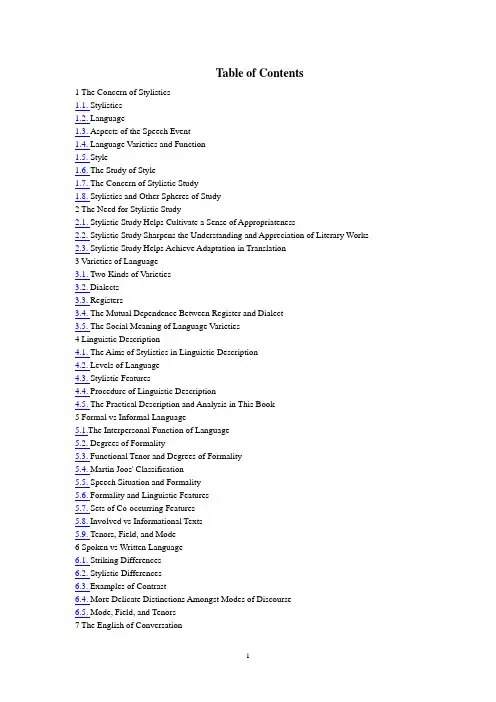

Table of Contents1 The Concern of Stylistics1.1. Stylistics1.2. Language1.3. Aspects of the Speech Event1.4. Language Varieties and Function1.5. Style1.6. The Study of Style1.7. The Concern of Stylistic Study1.8. Stylistics and Other Spheres of Study2 The Need for Stylistic Study2.1. Stylistic Study Helps Cultivate a Sense of Appropriateness2.2. Stylistic Study Sharpens the Understanding and Appreciation of Literary Works2.3. Stylistic Study Helps Achieve Adaptation in Translation3 Varieties of Language3.1. Two Kinds of Varieties3.2. Dialects3.3. Registers3.4. The Mutual Dependence Between Register and Dialect3.5. The Social Meaning of Language Varieties4 Linguistic Description4.1. The Aims of Stylistics in Linguistic Description4.2. Levels of Language4.3. Stylistic Features4.4. Procedure of Linguistic Description4.5. The Practical Description and Analysis in This Book5 Formal vs Informal Language5.1.The Interpersonal Function of Language5.2. Degrees of Formality5.3. Functional Tenor and Degrees of Formality5.4. Martin Joos' Classification5.5. Speech Situation and Formality5.6. Formality and Linguistic Features5.7. Sets of Co-occurring Features5.8. Involved vs Informational Texts5.9. Tenors, Field, and Mode6 Spoken vs Written Language6.1. Striking Differences6.2. Stylistic Differences6.3. Examples of Contrast6.4. More Delicate Distinctions Amongst Modes of Discourse6.5. Mode, Field, and Tenors7 The English of Conversation7.1. Necessity of Studying Speech7.2. Necessity of Studying Conversation7.3. Object of Study7.4. An Adapted Way of Transcription7.5. A Sample Text of Casual Conversation7.6. General Features7.7. Stylist Features in Terms of Levels of Language7.8. Summary7.9. Other Kinds of Conversation8 The English of Pubic Speech8.1. Scope of Public Speech8.2. A Sample of Text for Analysis8.3. General Features of Public Speech8.4. Stylistic Features of Public Speech9 The English of Advertising9.1. Advertising English as a Variety9.2. Newspaper Advertising9.3. Radio Advertising9.4. Television Advertising10 The English of News Reporting10.1. The English of New Reporting as a Variety10.2. Two Samples Texts for Analysis10.3. General Features of Newspaper Reporting10.4. Stylistic Features of Newpaper Reporting10.5. Stylistic Features of Radio and Television News11 The English of Science and Techology11.1. The Scope of the English of Science and Technology 11.2. Sample Texts for Analysis11.3. General Features of EST11.4. Stylistic Features of EST11.5. Features of Spoken EST12 The English of Legal Documents12.1. The English of Legal Documents as a Variety12.2. Sample Texts for Analysis12.3. Stylistic Features of Legal English13 The English of Literature (1) --General Remarks13.1. Literature as Language Art13.2. Literary Language and Ordinary Language13.3. Literary Language as a Variety14 The English of Literature (2) --The Language of Fiction 14.1. Manipulation of Semantic Roles14.2. Creation of Images and Symbols14.3. Preference in Diction14.4. Artistic Manipulation of Sentence Variety and Rhythm14.5. Employment of Various Points of View14.6. The Subtle Workings of Authorial Tones14.7. Various Ways of Presenting Speech and Thought15 The English of Literature (3) --The Language of Drama15.1. Manipulation of the Naturalness of Characters' Speech15.2. Exploitation of Different Speech Act, Turn-taking and Politeness Patterns15.3. Use of Assumptions, Presuppositions and Conversational Implicature16 The English of Literature (4) --The Language of Poetry16.1. Various Devices for Compression16.2. Extreme Care in Word Choice16.3. Free Arrangement of Word Order16.4. Lexical and Syntactical Repetition16.5. Full Manipulation of Sound Effects16.6. The Manipulation of Sight16.7. Analysis of Poems at All LevelsGlossary1. The Concern of Stylistics1.1 StylisticsWhat is stylistics?Simply defined, STYLISTICS is a discipline that studies the ways in which language is used; it is a discipline that studies the styles of language in use.This definition, however, needs elucidation.The stylistics we are discussing here is MODERN STYLISTICS, a discipline that applies concepts and techniques of modern linguistics to the study of styles of language use. It has two subdivisions: GENERAL STYLISTICS and LITERARY STYLISTICS, with the latter concentrating solely on unique features of various literary works, and the former on the general features of various types of language use. 'Stylistics', in this book, is general stylistics: one that studies the stylistic features of the main varieties of language, covering the functional varieties from the dimension of fields of discourse (different social activities), formal vs informal varieties from the dimension of tenors of discourse (different addresser-addressee relationships), and the spoken vs written varieties from the dimension of modes of discourse (different mediums). Meanwhile, general stylistics covers the various genres of literature (fiction, drama, poetry) in its study. But it focuses on the interpretation of the overall characteristics of respective genres, with selected extracts of literary texts as samples.If we say that literary stylistics also discusses the overall linguistic features of the various genres of literature, then the scope of general stylistics and the scope of literary stylistics are only partly overlapping, as is shown in the following figure:ModernStylisticsGe neral StylisticsLite rary StylisticsVar iety FeaturesGenreFeaturesLiterary TextStyleGeneral stylistics, as a discipline, needs to make clear a whole set of related terms and terminology and answer questions like: What is language? What is language variety? What is style? What are stylistic features? etc.1.2 LanguageFirst, we need to clarify our views on language. We must be clear about what language is, or how we should look at language.There are many definitions of language, or many ways of looking at it. Modern linguistics which began with Saussure's lectures on general linguistics in 1906-11 regards language as a system of signs. Meanwhile, American structuralism represented by Bloomfield regards language as a unified structure, a collection of habits. From the late 1950s on, the fact that 'man talks' and the implications of this human capacity have been at the centre of investigation in the linguistic sciences. The transformational-generative (TG) linguists headed by Noam Chomsky have beenconcerned with the innate and infinite capacity of the human mind. This approach sees language as a system of innate rules (Chomsky, 1957). The approach advocated by the systemic-functional linguists headed by M. A. K. Halliday sees language as a 'social semiotic', as an instrument used to perform various functions in social interaction. This approach holds that in many crucial respects, what is more important is not so much that 'man talks' as that 'men talk'; that is, that language is essentially a social activity (Halliday, 1978).The philosophical view of LANGUAGE or A LANGUAGE is related of the actual occurrence of language in society--what are called language activities. People accomplish a great deal not only through physical acts such as cooking, eating, bicycling, running a machine, cleaning, but also by verbal acts of all types: conversation, telephone calls, job application letters, notes scribbled to a roommate, etc. All utterances (whether a word, a sentence, or several sentences) can be thought of as goal-directed actions. (Austin, 1962; Searle, 1969) Such actions as carried out through language are SPEECH ACTs. Social activities in which language (either spoken or written) plays an important role such as conversation, discussion, lecture, etc are SPEECH EVENTs.Most of these events are sequential and transitory (that is, they occur in sequence and can not last for a long time). It is difficult to examine them at the time of their occurrence. So we have to record the events. Any such record, whether recalled through memory, or committed to a tape, or written down on paper, or printed in a book, of a speech event, is known as a TEXT.Language is often compared to a CODE, a system of signals or symbols used for sending a MESSAGE, a piece of information. In any act of verbal communication (both spoken and written, primarily spoken), language has been regarded as a system for translating meanings in the ADDRESSER's (the speaker's/writer's) mind into sounds/letters, ie ENCODING (meaning-to-sound/letter), or conversely, for translating sounds/letters into meanings in the ADDRESSEE's (the hearer's/ reader's) mind, ie DECODING (sound/letter-to-meaning), with lexis and grammar as the formal code mediating between meaning and sound/letter.But we must keep in mind that, unlike other signalling codes, language code does not operate in a fixed way- it is open-ended in that it permits generation of new meanings and new forms (such as metaphorical meanings, and neologisms); ie it is in a way creatively extendible.Text, then, is verbal communication (either spoken or written) seen as a message coded in a linear pattern of sound waves, or in a linear sequence of visible marks on paper.1.3 Aspects of the Speech EventLanguage is transmitted, patterned, and embedded in the human social experience. So it is both possible and useful to discern three crucial aspects of a speech event--the substantial, the formal, and the situational. (see Gregory and Carroll, 1978) Language is transmitted by means of audible sound waves in the air or visible marks on a surface. These sounds or marks are the SUBSTANCE of the speech events. The audible sounds or visible marks are not jumbled together--rather, they are arranged in a conventionally orderly way, displaying meaningful patterns in their internal relations. These meaningful internal patterns are the FORM of the speech event. Language activities do not occur in isolation from other human activities. They take place in relevant extratextual circumstances, linguistic and non-linguistic. These relevant extratextual circumstances are the SITUATION * of the speech event. Any speech event is part of a situation, and so has a relationship with that situation. Indeed, it is this contextual relationship between thesubstance and form of a speech event on the one hand and the situation in which it occurs on the other, which gives what is normally called 'meaning' to utterances. In other words, context determines meaning of features in situations.*Situation, as the non-linguistic setting or environment surrounding language use, can clearly influence linguistic behaviour. It is frequently synonymous with context, a conceptual abstraction from all possible situations, and its collocates -- context of situation, especially, context of utterance. The abstracted context, composed partly of the probable co-text, partly of the probable situation of each item, establishes the meaningfulness of the formal items in the language.1.4 Language Varieties and FunctionAs mentioned just now, when language is used, it is always used in a context. What is said and how it is said is often subject to a variety of circumstances. In other words, speech events differ in different situations, ie between different persons, at different times, in different places, for different purposes, through different media, and amidst different social environments. We often adjust our language according to the nature of the context of situation. Some situations seem to depend generally and fairly consistently on a regular set of linguistic features; as a result, there have appeared different types of a language which are called V ARIETIES OF LANGUAGE. So far as the English language is concerned, there are different 'Englishes' to fit different situations: for instance, Old/Modern English, British/American English, Black English, legal English, scientific English, liturgical English, advertising English, formal/ informal English, spoken/written English, etc. There is actually no such thing as a homogeneous English language.In all these varieties, language performs various communicative roles, ie FUNCTIONs. For example, language is used (functions) to communicate ideas, to express attitudes, and so on. The roles that language plays are ever changing and the number of the roles can be numerous. There have been many attempts to categorize these roles into a few major functions. The IDEATIONAL or REFERENTIAL function serves for expressing the speaker's/writer's experience of the real world, including the inner world of his/her own consciousness. The INTERPERSONAL or EXPRESSIVE/SOCIAL function serves to establish and maintain social relations, for the expression of social roles, and also for getting things done by means of interaction between one person and another. The TEXTUAL function provides means for making links within the text itself and with features of its immediate situation. (For detailed discussion see Buhler, 1934; Halliday, 1971.)The three functions represent three coexisting ways in which language has to be adapted to its users' communicative needs. First, it has to convey a message about' reality', about the world of experience, from speaker/writer to hearer/reader. Secondly, it must fit appropriately into a speech situation, fulfilling the particular social designs that speaker/writer has upon hearer/reader. Thirdly, it must be well constructed as an utterance or text, so as to serve the decoding needs of hearer/reader.These functions and the needs they serve are interrelated: success in interpersonal or expressive/social communication depends in part on success in transmitting a message, which in turn depends in part on success in terms of text production.Different types of language have relations with predominant functions, eg advertising with persuasion, TV commentary with information, address terms with social roles. Literary texts can be regarded as a type of language which performs a distinct social function -- an aesthetic orpoetic function.The functions are not mutually exclusive: an utterance may well have more than one function.1.5 StyleNow we come to the question of style.The word STYLE has been used in many ways:Style may refer to a person's distinctive language habits, or the set of individual characteristics of language use, as 'Shakespeare's style', 'Miltonic style', 'Johnsonese', or 'the style of James Joyce'. Buffon's ' Le style, c'est l'homme même', has contributed to the vogue of this definition. Often, it concentrates on a person's particularly singular or original features of speaking or writing. Hence at the extreme end style may refer to a writer's deviations from a relatively normal use of language.Style may refer to a set of collective characteristics of language use, ie language habits shared by a group of people at a given time, as 'Elizabethan style', in a given place, as 'Yankee humour', amidst a given occasion, as 'the style of public speaking', for a literary genre, as ‘ballad style', etc. Here the concentration is not on the individuality of the speaker or writer, but on their similarities in a given situation.Style may refer to the effectiveness of a mode of expression, which is implied in the definition of style as 'saying the right thing in the most effective way' or 'good manners', as a 'clear' or 'refined' style advocated in most books of composition.Style may refer solely to a characteristic of 'good' or 'beautiful' literary writings. This is the wide-spread use of style among literary critics, as 'grand style', 'ornate style', 'lucid style', 'plain style', etc, given to literary works.Of the above four senses of style, the first two (especially the second) come nearest to our definition of style. To be exact, we shall regard STYLE as the language habits of a person or group of persons in a given situation. As different situations tend to yield different varieties of a language which, in turn, display different linguistic features, so STYLE may be seen as the various characteristic uses of language that a person or group of persons make in various social contexts.Here we can use Ferdinand de Saussure's distinction between langue and parole. Langue is the system of rules common to speakers of a particular language (such as English), ie the general mass of linguistic features common to a language as used on every conceivable occasion. Parole is the particular uses of this system, or selections from this system, that a person or group of persons will make on this or that occasion. Style, then, belongs to parole. It consists in choices from the total linguistic repertoire of a particular language.All linguistic choices are meaningful, and all linguistic choices are stylistic. Even choices which are dearly dictated by subject matter are part of style. In our discussion, however, stylistic choice is limited to those aspects of linguistic choice which concern alternative ways of rendering the same subject matter, or those forms of language which can be seen as equivalent in terms of 'referential reality' they describe, or, in other words, the 'synonymous expressions' in transmitting the same 'message'.We are interested in the way in which choices of codes are adapted to communicative functions for advertising, news reporting, science thesis, ere including the aesthetic function forliterature. Hence the occurrence of different functional styles and of the various styles of literature.When we look at style in a text, we are not likely to be struck by local or individual choices in isolation, but rather at a pattern of choices. If, for instance, a text shows a repeated preference for passive structures over active structures, we are likely to consider this preference a feature of style. But local or specific features may also be noteworthy features of style if they form a significant relationship with other features in a coherent (consistent) pattern of choice. Consistency in preference is naturally reduced to 'frequency': To find out what is distinctive about the style of a text, we just measure the frequency of the features it contains. The more we wish to substantiate what we say about style, the more we will need to point to the linguistic evidence of texts; and linguistic evidence has to be couched in terms of numerical frequency.Yet it is worth our note that a feature which occurs more rarely than usual is just as much a part of the statistical pattern as one which occurs more often than usual; and it is also a significant aspect of our sense of style. (see 4.4)1.6 The Study of StyleSome scholars call the object of stylistics simply style, without further qualifications. Indeed, the study of style in western countries has been undertaken for more than two thousand years. The doctrine of 'decorum' or fittingness of style has passed down from the rhetoricians of Ancient Greece and Rome , who applied it first to oratory and then to written language. Up till the late 19th century, style studies had always been closely integrated with the art of writing and the evaluation of literary works. In fact, traditional approaches to language laid such heavy store by the quality of written language that 'good style' or sometimes simply 'style' was used as a description of writing that was praiseworthy, skilful or elegant.At the turn of the century, Ferdinand de Saussure, in his Geneva lectures of 1906-11, Cours de linguistique generale (1916), attacked the 19th century philologists for their 'diachronic' or historical study of language (ie looking at language as it changes through time), and for their interest in prescribing normal or 'correct' usage modelled on 'classic' literary writings. His influence was so strong that, after him, the professional study of language soon veered away from the historical concern of philology towards linguistics, which claimed to be heavily descriptive and to describe a given language 'synchronically' (ie synchronic study: looking at language as it exists at a given time). Saussure, with his insistence on the primacy of everyday speech, was little interested in the written language and even less in the literary. He viewed literary language as special uses of language which were comparatively unimportant in the study of language as a whole. His pupil, Charles Bally, who began the systematic study of what we now call 'stylistics', again gave scant attention to literature. American linguist Leonard Bloomfield held much the similar view. This is only too natural, for, at the turn of the century, new linguistics was yet fighting for its autonomy and needed to emphasize its difference from traditional language studies. It was not until the fifties that there appeared a sway from this position.Noam Chomsky's Syntactic Structures (1957) revived interest in what had once looked a discredited concern with 'correctness' in speech and with an inherited system of rules. Chomsky believes that the human mind must be constituted at birth to receive certain patterns of language; otherwise it would be very hard to explain how infants learn their mother tongue so quickly and with little effort. So it may not have been absurd of the European Renaissance to have interested itself in the prospect of a universal grammar underlying all human languages. Chomsky destroyedthe dominance of structuralism and encouraged a new tolerance of historical grammar. And in doing this he initiated a new interest in literature among professional linguists and the prospect of co-operation between criticism and the professional study of language.By the 1950s most of the early anxieties on the part of linguists had become unnecessary. The tools of linguistics could be used in related disciplines without the danger of reducing linguistics itself to a mere technology or a service station. On the contrary, by the time they came back to literary language, linguists had been armed to the teeth – with fresh insights and new theories as well as a formidable technical vocabulary. This time they would study style in a much more detailed and systematic way. They would not study literature to the exclusion of other varieties of language. Rather they would approach literature as a complex of varieties of language in use and point to the aesthetic function of literary language.The 1960s saw the flourishing of modern stylistics: Two landmark volumes of papers presented respectively to the Indiana Style Conference in 1958 ( Style in language , MIT Press) and to the Bellagio Style Conference in 1969 ( Literary Style: a Symposium , OUP) came into being. Monographs such as Linguistics and Style (Enkvist et al, 1964) and Investigating English Style (Crystal and Davy, 1969), A Linguistic Guide to English Poetry (Leech, 1969) appeared. New courses on style were offered in colleges and universities. Textbooks concerning spoken varieties of English (some with accompanying records or tapes) such as Varieties of Spoken Englis h (Dickinson and Mackin, 1969), Scientifically Speaking (Brookes, 1971) were published. Grammars, as A Grammar of Contemporary English (Quirk et al, 1972) widened their scope to include in their study 'sentence connection', 'focus', 'theme', 'emphasis', and 'varieties of English and classes of English'. Dictionaries began to give labels (eg. fml, colloquial, slang, etc) to words and phrases of stylistic colouring.From the 1960s onward, application of various linguistic models such as transformational-generative linguistics, systemic-functional linguistics, speech-act theory, discourse analysis etc in stylistic analysis has been gaining momentum in the past decades of years.1.7 The Concern of Stylistic StudyHaving discussed what language is and the sense of style, we are now in a position to come to a more refined definition of stylistics: It is a discipline that studies the sum of stylistic features characteristic of the different varieties of language.Stylistic study concerns itself with the situational features that influence variations in language use, the criterion for the classification of language variety, and the description and interpretation of the linguistic features and functions of the main varieties (both literary and non-literary) of a language-- in this book, of the Modern English language.As an independent discipline, stylistics offers a comparatively more complete theoretical framework and a more rigorous procedure of linguistic description, so that learners will have a systematic knowledge of the features of different varieties of language, make appropriate use of language in their communication, familiarize themselves with the stylistic features of the different genres of literature, and deepen their understanding and appreciation of literary works. Besides, stylistics offers useful ideas on translation and language teaching.1.8 Stylistics and Other Spheres of StudyA formerly very much borderline discipline, stylistics takes roots in the soil of modern linguistics, using models and methods of linguistic description in the stylistic analysis of texts. Stylistics also absorbs nourishment from literary theories, and so is closely related to them.Similar to modern linguistics, stylistics lays stress on the study of language functions and the different structures dictated by these functions. But linguistics stresses the description of linguistic structures while stylistics on the stylistic effects of different language structures.Stylistics is the continuation and development of rhetoric. However, discarding the traditional practices of rhetoric to establish norms for people to model on, stylistics turns to the presentation of the functional features of language, --- it is descriptive, not prescriptive. It does not aim at a so-called 'refined' style of writing, but at a manner 'appropriate' to the situation.Stylistics supplies literary criticism with a brand-new approach. Since the beginning of the 20th century the linguistic turn in literary criticism has enabled the scientific school of literary theorists such as Russian formalism, New Criticism, Structuralism, etc to place language in the central position of their theories. With a whole set of meta-language renewed by modern linguistics and modern literary theory-- deviation, prominence, function, situational factors, narrative points of view, modes of presenting speech, etc, and with the multi-level structural approach, stylistics has pushed the linguistic turn to its extreme. Making literary research still more scientific and more accurate, it broadens the vision of literary criticism.Study Questions1) Consult at least five books on stylistics, note down the definitions of stylistics that they give, and discuss the similarities and differences among the definitions.2) Compare the definitions of language put forward by different schools of linguistics. Tell what view or views of language is or are suited to stylistics, and why.3) What aspects are there in a speech event?4) Different scholars classify the function of language into different major types. Compare them, and comment on the saying: The functions of language are mutually exclusive.5) Comment on the different senses of style.6) The goal of most stylistic study is simply to describe the formal features of texts for their own sake. What do you think of this statement?7) Discuss the relationship between stylistics and rhetoric, and tell how stylistics broadens the vision of literary criticism.。

A brief summaryStylistics is a newly-born study, it was in the 1960s that stylistic study really began to flourish in Great Britain and the United States. Professor Wang Zuoliang is the first person in China to study it.The stylistics we are discussing here is Modern Stylistics, a discipline that applies concepts and techniques of modern linguistics to the study of styles of language use. It has two subdivisions: General Stylistics and Literary Stylistics, with the latter concentrating solely on unique features of various literary works, and the former on the general features of various types of language use.1.2.1 Speech Acts1.2.2 Speech Events1.2.3 Text / Message / Discourse1. Substantial2. Formal3. SituationalIt is this contextual relationship between the substance and form of a speech event on the one hand and the situation in which it occurs on the other, which gives what is normally called ―meaning‖ to utterance. In other words, context determines meaning of features in situation.e.g.My beloved grandfather has just passed to his heavenly reward.My dear grandfather has just expired.My grandfather has just passed away.My grandfather has died.同是表达―死‖这个概念,但场合不同,表达方式也不同。

英语文体学3,4Chapter 3 Varieties of Language语言变体(varieties of language)可分为两类:一类是方言变体(dialectal varieties), 俗称方言;另一类是话语类变体(diatypic varieties), 亦称语域(register)。

方言是以语言的使用者(users)为基准而区分的语言变体;语域则是按照语言使用者对语言的使用(uses)而区分的语言变体。

因此,方言多与交际者的社会阶层、社会地位、地域、年龄、性别及所处的时代等因素有关,比较稳定;语域则多与交际者所从事的社会活动密切相关。

方言(Dialect):1) 语言使用者的个人特征(individuality)--Idiolect(语言的流利度、清晰度、表达能力大小等。

例:Mr X’s English, Mr Y’s English。

)2) 时代特征(temporal features)--Temporal Dialect3) 地域特征(geographical feature)--Regional Dialect4) 社会特征(social features)--Social DialectSocioeconomic status varieties 社会经济变体Ethnic varieties 种族变体Gender varieties 性别变体Age varieties 年龄变体5) 可理解的程度和范围—Standard Dialect方言(Dialects)具有社会指示功能,方言不仅能体现人物的地域特征,而且能反映出人物的社会地位、文化程度乃至个人性格,这一点在文学作品中最为明显语域(Register)1) Field of Discourse(话语范围/语场)Non-technical fields of discourseTechnical fields of discourse2) Mode of Discourse(话语方式/语式)Speech: conversing, monologuingWriting: texts written to be spoken as if not written/ written to be read3) Tenor of Discourse(话语基调/语基)Personal Tenor(个人基调)Functional Tenor(功能基调)1) Field of Discourse(话语范围/语场)话语范围指的是言语交际过程中发生的事情,进行的活动,论及的事情或表达的经验等,它能体现语言使用者在特定情境语境中所要实现的交际目的和作用。