外文翻译----微机发展简史

- 格式:docx

- 大小:47.41 KB

- 文档页数:20

附录外文文献及翻译Progress in computersThe first stored program computers began to work around 1950. The one we built in Cambridge, the EDSAC was first used in the summer of 1949.These early experimental computers were built by people like myself with varying backgrounds. We all had extensive experience in electronic engineering and were confident that that experience would standus in good stead. This proved true, although we had some new things to learn. The most important of these was that transients must be treated correctly; what would cause a harmless flash on the screen of a television set could lead to a serious error in a computer.As far as computing circuits were concerned, we found ourselves with an embarrass de riches. For example, we could use vacuum tube diodes for gates as we did in the EDSAC or pentodes with control signals on both grids, a system widely used elsewhere. This sort of choice persisted and the term famillogic came into use. Those who have worked in the computer field will remember TTL, ECL and CMOS. Of these, CMOS has now become dominant.In those early years, the IEE was still dominated by power engineering and we had to fight a number of major battles in order to get radio engineering along with the rapidly developing subject of electronics. dubbed in the IEE light current electrical engineering. properlyrecognized as an activity in its own right. I remember that we had some difficulty in organizing a co nference because the power engineers‟ ways of doing things were not our ways. A minor source of irritation was that all IEE published papers were expected to start with a lengthy statement of earlier practice, something difficult to do when there was no earlier practiceConsolidation in the 1960sBy the late 50s or early 1960s, the heroic pioneering stage was over and the computer field was starting up in real earnest. The number of computers in the world had increased and they were much more reliable than the very early ones . To those years we can ascribe the first steps in high level languages and the first operating systems. Experimental time-sharing was beginning, and ultimately computer graphics was to come along.Above all, transistors began to replace vacuum tubes. This change presented a formidable challenge to the engineers of the day. They had to forget what they knew about circuits and start again. It can only be said that they measured up superbly well to the challenge and that the change could not have gone more smoothly.Soon it was found possible to put more than one transistor on the same bit of silicon, and this was the beginning of integrated circuits. As time went on, a sufficient level of integration was reached for one chip to accommodate enough transistors for a small number of gates or flip flops. This led to a range of chips known as the 7400 series. The gates and flip flops were independent of one another and each had its own pins. They could be connected by off-chip wiring to make a computer or anything else.These chips made a new kind of computer possible. It was called a minicomputer. It was something less that a mainframe, but still very powerful, and much more affordable. Instead of having one expensive mainframe for the whole organization, a business or a university was able to have a minicomputer for each major department.Before long minicomputers began to spread and become more powerful. The world was hungry for computing power and it had been very frustrating for industry not to be able to supply it on the scalerequired and at a reasonable cost. Minicomputers transformed the situation.The fall in the cost of computing did not start with the minicomputer; it had always been that way. This was what I meant when I referred in my abstract to inflation in the computer industry …going the other way‟. As time goes on people get more for their money, not less.Research in Computer Hardware.The time that I am describing was a wonderful one for research in computer hardware. The user of the 7400 series could work at the gate and flip-flop level and yet the overall level of integration was sufficient to give a degree of reliability far above that of discreet transistors. The researcher, in a university orelsewhere, could build any digital device that a fertile imagination could conjure up. In the Computer Laboratory we built the Cambridge CAP, a full-scaleminicomputer with fancy capability logic.The 7400 series was still going strong in the mid 1970s and was used for the Cambridge Ring, a pioneering wide-band local area network. Publication of the design study for the Ring came just before the announcement of the Ethernet. Until these two systems appeared, users had mostly been content with teletype-based local area networks. Rings need high reliability because, as the pulses go repeatedly round the ring, they must be continually amplified and regenerated. It was the high reliability provided by the 7400 series of chips that gave us the courage needed to embark on the project for the Cambridge Ring.The RISC Movement and Its AftermathEarly computers had simple instruction sets. As time went on designers of commercially available machines added additional features which they thought would improve performance. Few comparative measureme nts were done and on the whole the choice of features depended upon the designer‟s intuition.In 1980, the RISC movement that was to change all this broke on the world. The movement opened with a paper by Patterson and ditzy entitled The Case for the Reduced Instructions Set Computer.Apart from leading to a striking acronym, this title conveys little of the insights into instruction set design which went with the RISC movement, in particular the way it facilitated pipelining, a system whereby several instructions may be in different stages of execution within the processor at the same time. Pipelining was not new, but it was new for small computersThe RISC movement benefited greatly from methods which had recently become available for estimating the performance to be expected from a computer design without actually implementing it. I refer to the use of a powerful existing computer to simulate the new design. By the use of simulation, RISC advocates were able to predict with some confidence that a good RISC design would be able to out-perform the best conventional computers using the same circuit technology. This prediction was ultimately born out in practice.Simulation made rapid progress and soon came into universal use by computer designers. In consequence, computer design has become more of a science and less of an art. Today, designers expect to have a roomful of, computers available to do their simulations, not just one. They refer to such a roomful by the attractive name of computer farm.The x86 Instruction SetLittle is now heard of pre-RISC instruction sets with one major exception, namely that of the Intel 8086 and its progeny, collectively referred to as x86. This has become the dominant instruction set and the RISC instruction sets that originally had a considerable measure of success are having to put up a hard fight for survival.This dominance of x86 disappoints people like myself who come from the research wings. both academic and industrial. of the computer field. No doubt, business considerations have a lot to do with the survival of x86, but there are other reasons as well. However much we research oriented people would liketo think otherwise. high level languages have not yet eliminated the use of machine code altogether. We need to keep reminding ourselves that there is much to be said for strict binary compatibility with previous usage when that can be attained. Nevertheless, things might have been different if Intel‟s major attempt to produce a good RISC chip had been more successful. I am referring to the i860 (not the i960, which was something different). In many ways the i860 was an excellent chip, but its software interface did not fit it to be used in aworkstation.There is an interesting sting in the tail of this apparently easy triumph of the x86 instruction set. It proved impossible to match the steadily increasing speed of RISC processors by direct implementation ofthe x86 instruction set as had been done in the past. Instead, designers took a leaf out of the RISC book; although it is not obvious, on the surface, a modern x86 processor chip contains hidden within it a RISC-style processor with its own internal RISC coding. The incoming x86 code is, after suitable massaging, converted into this internal code and handed over to the RISC processor where the critical execution is performed. In this summing up of the RISC movement, I rely heavily on the latest edition of Hennessy and Patterson‟s books on computer design as my supporting authority; see in particular Computer Architecture, third edition, 2003, pp 146, 151-4, 157-8.The IA-64 instruction set.Some time ago, Intel and Hewlett-Packard introduced the IA-64 instruction set. This was primarily intended to meet a generally recognized need for a 64 bit address space. In this, it followed the lead of the designers of the MIPS R4000 and Alpha. However one would have thought that Intel would have stressed compatibility with the x86; the puzzle is that they did the exact opposite.Moreover, built into the design of IA-64 is a feature known as predication which makes it incompatible in a major way with all other instruction sets. In particular, it needs 6 extra bits with each instruction. This upsets the traditional balance between instruction word length and information content, and it changes significantly the brief of the compiler writer.In spite of having an entirely new instruction set, Intel made the puzzling claim that chips based on IA-64 would be compatible with earlier x86 chips. It was hard to see exactly what was meant.Chips for the latest IA-64 processor, namely, the Itanium, appear to have special hardware for compatibility. Even so, x86 code runs very slowly.Because of the above complications, implementation of IA-64 requires a larger chip than is required for more conventional instruction sets. This in turn implies a higher cost. Such at any rate, is the received wisdom, and, as a general principle, it was repeated as such by Gordon Moore when he visited Cambridge recently to open the Betty and Gordon Moore Library. I have, however, heard it said that the matter appears differently from within Intel. This I do not understand. But I am very ready to admit that I am completely out of my depth as regards the economics of the semiconductor industry.Shortage of ElectronsAlthough shortage of electrons has not so far appeared as an obvious limitation, in the long term it may become so. Perhaps this is where the exploitation of non-conventional CMOS will lead us. However, some interesting work has been done. notably by HuronAmend and his team working in the Cavendish Laboratory. on the direct development of structures in which a single electron more or less makes the difference between a zero and a one. However very little progress has been made towards practical devices that could lead to the construction of a computer. Even with exceptionally good luck, many tens of years must inevitably elapse before a working computer based on single electron effects can be contemplated.微机发展简史第一台存储程序的计算开始出现于1950前后,它就是1949年夏天在剑桥大学,我们创造的延迟存储自动电子计算机(EDSAC)。

微机发展历史微机,也被称为个人电脑或PC(Personal Computer),是一种小型计算机系统,由中央处理器、内存、硬盘、显示器等组成。

微机的发展历史可以追溯到20世纪70年代,经过数十年的演变和创新,如今的微机已经成为人们生活中不可或缺的一部分。

1970年代初,微机的雏形开始出现。

当时的微机体积庞大,价格昂贵,只有大型企业和研究机构才能购买和使用。

这些早期的微机主要采用了8位或16位的微处理器,内存容量非常有限。

由于技术限制,这些微机的计算能力和图形显示功能都很有限。

随着技术的进步和集成电路的发展,1977年,苹果公司推出了第一台个人电脑Apple II,这是当时市场上第一款真正意义上的微机。

Apple II采用了8位的6502微处理器,拥有16KB的内存,具备了图形显示和音频功能。

它的成功引领了个人电脑的潮流,使得微机逐渐从小众市场走向大众市场。

1981年,IBM推出了第一台IBM PC,这是一款以8088微处理器为核心的个人电脑。

IBM PC的推出标志着微机进入了一个全新的阶段,也奠定了微机的标准化地位。

IBM PC的成功使得微软公司的操作系统MS-DOS成为了主流操作系统,微机市场进一步扩大。

随着技术的不断进步,微机的性能也得到了显著提升。

1985年,Intel推出了第一款x86架构的微处理器386,它的推出使得微机的计算能力大幅提升,同时也推动了图形界面操作系统的发展。

微软公司于是推出了Windows操作系统,使得微机的用户界面更加友好和直观。

1990年代,微机进入了一个高速发展的时期。

随着互联网的兴起,微机开始与网络结合,人们可以通过微机上网冲浪、发送电子邮件等。

同时,微机的硬件技术也不断创新,处理器频率、内存容量、存储空间等都得到了巨大提升。

微机不再局限于个人使用,也广泛应用于商业、教育、娱乐等领域。

进入21世纪,微机的发展进入了一个全新的阶段。

随着移动互联网的兴起,智能手机和平板电脑逐渐取代了传统的个人电脑。

微型计算机的发展历史、现状及前景摘要自1981年美国IBM公司推出了第一代微型计算机IBM-PC/XT以来,以微处理器为核心的微型计算机便以其执行结果精确、处理速度快捷、小型、廉价、可靠性高、灵活性大等特点迅速进入社会各个领域,且技术不断更新、产品不断换代,先后经历了80286、80386、80486乃至当前的80586(Pentium)微处理器芯片阶段,并从单纯的计算工具发展成为能够处理数字、符号、文字、语言、图形、图像、音频和视频等多种信息在内的强大多媒体工具。

如今的微型计算机产品无论从运算速度、多媒体功能、软硬件支持性以及易用性方面都比早期产品有了很大的飞跃,便携式计算机更是以小巧、轻便、无线联网等优势受到了越来越多的移动办公人士的喜爱,一直保持着高速发展的态势。

关键词:微型计算机现状发展一微型计算机的发展历史第一台微型计算机——1974年,罗伯茨用8080微处理器装配了一种专供业余爱好者试验用的计算机“牛郎星”(Altair)。

第一台真正的微型计算机——1976年,乔布斯和沃兹尼克设计成功了他们的第一台微型计算机,装在一个木盒子里,它有一块较大的电路板,8KB的存储器,能发声,且可以显示高分辨率图形。

1977年,沃兹尼克设计了世界上第一台真正的个人计算机——AppleⅡ,并“追认”他们在“家酿计算机俱乐部”展示的那台机器为AppleⅠ。

1978年初,他们又为AppleⅡ增加了磁盘驱动器。

从微型计算机的档次来划分,它的发展阶段又可以分为以下几个阶段:第一代微机——第一代PC机以IBM公司的IBM PC/XT机为代表,CPU是8088,诞生于1981年,如图1-3所示。

后来出现了许多兼容机。

第二代微机——IBM公司于1985年推出的IBM PC/AT标志着第二代PC机的诞生。

它采用80286为CPU,其数据处理和存储管理能力都大大提高。

第三代微机——1987年,Intel公司推出了80386微处理器。

微型计算机发展史微处理器(Microprocessor),简称µP或MP,是由一片或几片大规模集成电路组成的具有运算器和控制器的中央处理机部件,即CPU(Certal Processing Unit)。

微处理器本身并不等于微型计算机,它仅仅是微型计算机中央处理器,有时为了区别大、中、小型中央处理器(CPU)与微处理器,把前者称为CPU,后者称为MPU(Microprocessing Unit)。

微型计算机(Microcomputer),简称µC或MC,是指以微处理器为核心,配上由大规模集成电路制作的存储器、输入/输出接口电路及系统总线所组成的计算机(简称微型机,又称微型电脑)。

有的微型计算机把CPU、存储器和输入/输出接口电路都集成在单片芯片上,称之为单片微型计算机,也叫单片机。

微型计算机系统(Microcomputer System),简称µCS或MCS,是指以微型计算机为中心,以相应的外围设备、电源、辅助电路(统称硬件)以及控制微型计算机工作的系统软件所构成的计算机系统。

20世纪70年代,微处理器和微型计算机的生产和发展,一方面是由于军事工业、空间技术、电子技术和工业自动化技术的迅速发展,日益要求生产体积小、可靠性高和功耗低的计算机,这种社会的直接需要是促进微处理器和微型计算机产生和发展的强大动力;另一方面是由于大规模集成电路技术和计算机技术的飞速发展,1970年已经可以生产1KB的存储器和通用异步收发器(UART)等大规模集成电路产品并且计算机的设计日益完善,总线结构、模块结构、堆栈结构、微处理器结构、有效的中断系统及灵活的寻址方式等功能越来越强,这为研制微处理器和微型计算机打下了坚实的物质基础和技术基础。

因而,自从1971年微处理器和微型计算机问世以来,它就得到了异乎寻常的发展,大约每隔2~4年就更新换代一次。

至今,经历了三代演变,并进入第四代。

微型计算机的换代,通常是按其CPU字长和功能来划分的。

自1981年美国IBM 公司推出第一代微型计算机IBM—PC/XT以来,微型机以其执行结果精确、处理速度怏捷、性价比高、轻便小巧等特点迅速进入社会各个领域,且技术不断更新、产品快速换代,从单纯的计算工具发展成为能够处理数字、符号、文字、语言、图形、图像、音频、视频等多种信息的强大多媒体工具。

如今的微型机产品无论从运算速度、多媒体功能、软硬件支持还是易用性等方面都比早期产品有了很大飞跃。

便携机更是以使用便捷、无线联网等优势越来

3微型计算机技术现状及发展趋势

微型计算机是当今发展速度最快、应用最为普及的计算机类型。

它可以细分为PC服务器、NT工作站、台式(也称桌上型)电脑、膝上型电脑、笔记本型电脑、掌上型电脑、可穿戴式计算机以及问世不久的平板电脑等多种类型。

习惯上将尺。

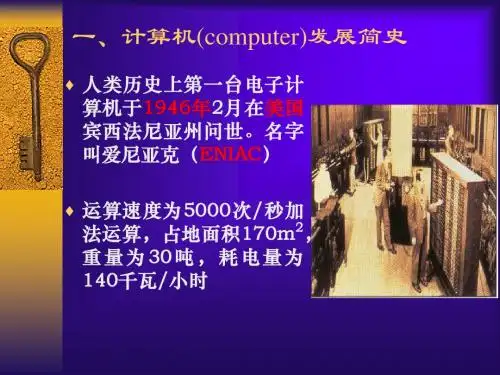

计算机的发展历史求图片和文字介绍计算机发展史(一)1945年,由美国生产了第一台全自动电子数字计算机“埃尼阿克”(英文缩写词是ENIAC,即Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator,中文意思是电子数字积分器和计算器)。

它是美国奥伯丁武器试验场为了满足计算弹道需要而研制成的。

主要发明人是电气工程师普雷斯波·埃克特(J. Prespen Eckert)和物理学家约翰·莫奇勒博士(John W. Mauchly)。

这台计算机1946年2月交付使用,共服役9年。

它采用电子管作为计算机的基本元件,每秒可进行5000次加减运算。

它使用了18000只电子管,10000只电容,7000只电阻,体积3000立方英尺,占地170平方米,重量30吨,耗电140~150千瓦,是一个名副其实的“庞然大物”。

ENIAC机的问世具有划时代的意义,表明计算机时代的到来,在以后的40多年里,计算机技术发展异常迅速,在人类科技史上还没有一种学科可以与电子计算机的发展速度相提并论。

下面介绍各代计算机的硬件结构及系统的特点:一、第一代(1946~1958):电子管数字计算机计算机的逻辑元件采用电子管,主存储器采用汞延迟线、磁鼓、磁芯;外存储器采用磁带;软主要采用机器语言、汇编语言;应用以科学计算为主。

其特点是体积大、耗电大、可靠性差、价格昂贵、维修复杂,但它奠定了以后计算机技术的基础。

二、第二代(1958~1964):晶体管数字计算机晶体管的发明推动了计算机的发展,逻辑元件采用了晶体管以后,计算机的体积大大缩小,耗电减少,可靠性提高,性能比第一代计算机有很大的提高。

主存储器采用磁芯,外存储器已开始使用更先进的磁盘;软件有了很大发展,出现了各种各样的高级语言及其编译程序,还出现了以批处理为主的操作系统,应用以科学计算和各种事务处理为主,并开始用于工业控制。

三、第三代(1964~1971):集成电路数字计算机20世纪60年代,计算机的逻辑元件采用小、中规模集成电路(SSI、MSI),计算机的体积更小型化、耗电量更少、可靠性更高,性能比第十代计算机又有了很大的提高,这时,小型机也蓬勃发展起来,应用领域日益扩大。

微型计算机的发展历史、现状及前景摘要自1981年美国IBM公司推出了第一代微型计算机IBM—PC/XT以来,以微处理器为核心的微型计算机便以其执行结果精确、处理速度快捷、小型、廉价、可靠性高、灵活性大等特点迅速进入社会各个领域,且技术不断更新、产品不断换代,先后经历了80286、80386、80486乃至当前的80586 (Pentium)微处理器芯片阶段,并从单纯的计算工具发展成为能够处理数字、符号、文字、语言、图形、图像、音频和视频等多种信息在内的强大多媒体工具。

如今的微型计算机产品无论从运算速度、多媒体功能、软硬件支持性以及易用性方面都比早期产品有了很大的飞跃,便携式计算机更是以小巧、轻便、无线联网等优势受到了越来越多的移动办公人士的喜爱,一直保持着高速发展的态势.关键词:微型计算机现状发展一微型计算机的发展历史第一台微型计算机-—1974年,罗伯茨用8080微处理器装配了一种专供业余爱好者试验用的计算机“牛郎星”(Altair)。

第一台真正的微型计算机——1976年,乔布斯和沃兹尼克设计成功了他们的第一台微型计算机,装在一个木盒子里,它有一块较大的电路板,8KB的存储器,能发声,且可以显示高分辨率图形。

1977年,沃兹尼克设计了世界上第一台真正的个人计算机—-AppleⅡ,并“追认”他们在“家酿计算机俱乐部”展示的那台机器为AppleⅠ。

1978年初,他们又为AppleⅡ增加了磁盘驱动器。

从微型计算机的档次来划分,它的发展阶段又可以分为以下几个阶段:第一代微机-—第一代PC机以IBM公司的IBM PC/XT机为代表,CPU是8088,诞生于1981年,如图1—3所示.后来出现了许多兼容机。

第二代微机——IBM公司于1985年推出的IBM PC/AT标志着第二代PC机的诞生.它采用80286为CPU,其数据处理和存储管理能力都大大提高。

第三代微机——1987年,Intel公司推出了80386微处理器。

Progress in ComputersPrestige Lecture delivered to IEE, Cambridge, on 5 February 2004Maurice WilkesComputer LaboratoryUniversity of CambridgeThe first stored program computers began to work around 1950. The one we built in Cambridge, the EDSAC was first used in the summer of 1949.These early experimental computers were built by people like myself with varying backgrounds. We all had extensive experience in electronic engineering and were confident that that experience would stand us in good stead. This proved true, although we had some new things to learn. The most important of these was that transients must be treated correctly; what would cause a harmless flash on the screen of a television set could lead to a serious error in a computer.As far as computing circuits were concerned, we found ourselves with an embarass de richess. For example, we could use vacuum tube diodes for gates as we did in the EDSAC or pentodes with control signals on both grids, a system widely used elsewhere. This sort of choice persisted and the term families of logic came into use. Those who have worked in the computer field will remember TTL, ECL and CMOS. Of these, CMOS has now become dominant.In those early years, the IEE was still dominated by power engineering and we had to fight a number of major battles in order to get radio engineering along with the rapidly developing subject of electronics.dubbed in the IEE light current electrical engineering.properlyrecognised as an activity in its own right. I remember that we had some difficulty in organising a conference because the power engineers’ ways of doing things were not our ways. A minor source of irritation was that all IEE published papers were expected tostart with a lengthy statement of earlier practice, something difficult to do when there was no earlier practiceConsolidation in the 1960sBy the late 50s or early 1960s, the heroic pioneering stage was over and the computer field was starting up in real earnest. The number of computers in the world had increased and they were much more reliable than the very early ones . To those years we can ascribe the first steps in high level languages and the first operating systems. Experimental time-sharing was beginning, and ultimately computer graphics was to come along.Above all, transistors began to replace vacuum tubes. This change presented a formidable challenge to the engineers of the day. They had to forget what they knew about circuits and start again. It can only be said that they measured up superbly well to the challenge and that the change could not have gone more smoothly.Soon it was found possible to put more than one transistor on the same bit of silicon, and this was the beginning of integrated circuits. As time went on, a sufficient level of integration was reached for one chip to accommodate enough transistors for a small number of gates or flip flops. This led to a range of chips known as the 7400 series. The gates and flip flops were independent of one another and each had its own pins. They could be connected by off-chip wiring to make a computer or anything else.These chips made a new kind of computer possible. It was called a minicomputer. It was something less that a mainframe, but still very powerful, and much more affordable. Instead of having one expensive mainframe for the whole organisation, a business or a university was able to have a minicomputer for each major department.Before long minicomputers began to spread and become more powerful. The world was hungry for computing power and it had been very frustrating for industry not to be able to supply it on the scale required and at a reasonable cost. Minicomputers transformed the situation.The fall in the cost of computing did not start with the minicomputer; it had always been that way. This was what I meant when I referred in my abstract to inflation in the computer industry ‘going the other way’. As time goes on people get more for their money, not less.Research in Computer Hardware.The time that I am describing was a wonderful one for research in computer hardware. The user of the 7400 series could work at the gate and flip-flop level and yet the overall level of integration was sufficient to give a degree of reliability far above that of discreet transistors. The researcher, in a university or elsewhere, could build any digital device that a fertile imagination could conjure up. In the Computer Laboratory we built the Cambridge CAP, a full-scale minicomputer with fancy capability logic.The 7400 series was still going strong in the mid 1970s and was used for the Cambridge Ring, a pioneering wide-band local area network. Publication of the design study for the Ring came just before the announcement of the Ethernet. Until these two systems appeared, users had mostly been content with teletype-based local area networks.Rings need high reliability because, as the pulses go repeatedly round the ring, they must be continually amplified and regenerated. It was the high reliability provided by the 7400 series of chips that gave us the courage needed to embark on the project for the Cambridge Ring.The RISC Movement and Its AftermathEarly computers had simple instruction sets. As time went on designers of commercially available machines added additional features which they thought would improve performance. Few comparative measurements were done and on the whole the choice of features depended upon the designer’s intuition.In 1980, the RISC movement that was to change all this broke on the world. The movement opened with a paper by Patterson and Ditzel entitled The Case for the Reduced Instructions Set Computer.Apart from leading to a striking acronym, this title conveys little of the insights into instruction set design which went with the RISC movement, in particular the way it facilitated pipelining, a system whereby several instructions may be in different stages of execution within the processor at the same time. Pipelining was not new, but it was new for small computersThe RISC movement benefited greatly from methods which had recently become available for estimating the performance to be expected from a computer design withoutactually implementing it. I refer to the use of a powerful existing computer to simulate the new design. By the use of simulation, RISC advocates were able to predict with some confidence that a good RISC design would be able to out-perform the best conventional computers using the same circuit technology. This prediction was ultimately born out in practice.Simulation made rapid progress and soon came into universal use by computer designers. In consequence, computer design has become more of a science and less of an art. Today, designers expect to have a roomful of, computers available to do their simulations, not just one. They refer to such a roomful by the attractive name of computer farm.The x86 Instruction SetLittle is now heard of pre-RISC instruction sets with one major exception, namely that of the Intel 8086 and its progeny, collectively referred to as x86. This has become the dominant instruction set and the RISC instruction sets that originally had a considerable measure of success are having to put up a hard fight for survival.This dominance of x86 disappoints people like myself who come from the research wings.both academic and industrial.of the computer field. No doubt, business considerations have a lot to do with the survival of x86, but there are other reasons as well. However much we research oriented people would like to think otherwise. high level languages have not yet eliminated the use of machine code altogether. We need to keep reminding ourselves that there is much to be said for strict binary compatibility with previous usage when that can be attained. Nevertheless, things might have been different if Intel’s major attempt to produ ce a good RISC chip had been more successful. I am referring to the i860 (not the i960, which was something different). In many ways the i860 was an excellent chip, but its software interface did not fit it to be used in a workstation.There is an interesting sting in the tail of this apparently easy triumph of the x86 instruction set. It proved impossible to match the steadily increasing speed of RISC processors by direct implementation of the x86 instruction set as had been done in the past. Instead, designers took a leaf out of the RISC book; although it is not obvious, on the surface, a modern x86 processor chip contains hidden within it a RISC-style processor with its own internal RISC coding. The incoming x86 code is, after suitable massaging, converted into thisinternal code and handed over to the RISC processor where the critical execution is performed.In this summing up of the RISC movement, I rely heavily on the latest edition of Hennessy and Patterson’s books on computer design as my supporting authority; see in particular Computer Architecture, third edition, 2003, pp 146, 151-4, 157-8.The IA-64 instruction set.Some time ago, Intel and Hewlett-Packard introduced the IA-64 instruction set. This was primarily intended to meet a generally recognised need for a 64 bit address space. In this, it followed the lead of the designers of the MIPS R4000 and Alpha. However one would have thought that Intel would have stressed compatibility with the x86; the puzzle is that they did the exact opposite.Moreover, built into the design of IA-64 is a feature known as predication which makes it incompatible in a major way with all other instruction sets. In particular, it needs 6 extra bits with each instruction. This upsets the traditional balance between instruction word length and information content, and it changes significantly the brief of the compiler writer.In spite of having an entirely new instruction set, Intel made the puzzling claim that chips based on IA-64 would be compatible with earlier x86 chips. It was hard to see exactly what was meant.Chips for the latest IA-64 processor, namely, the Itanium, appear to have special hardware for compatibility. Even so, x86 code runs very slowly.Because of the above complications, implementation of IA-64 requires a larger chip than is required for more conventional instruction sets. This in turn implies a higher cost. Such at any rate, is the received wisdom, and, as a general principle, it was repeated as such by Gordon Moore when he visited Cambridge recently to open the Betty and Gordon Moore Library. I have, however, heard it said that the matter appears differently from within Intel. This I do not understand. But I am very ready to admit that I am completely out of my depth as regards the economics of the semiconductor industry.AMD have defined a 64 bit instruction set that is more compatible with x86 and they appear to be making headway with it. The chip is not a particularly large one. Some people think that this is what Intel should have done. [Since the lecture was delivered, Intel haveannounced that they will market a range of chips essentially compatible with those offered by AMD.]The Relentless Drive towards Smaller TransistorsThe scale of integration continued to increase. This was achieved by shrinking the original transistors so that more could be put on a chip. Moreover, the laws of physics were on the side of the manufacturers. The transistors also got faster, simply by getting smaller. It was therefore possible to have, at the same time, both high density and high speed.There was a further advantage. Chips are made on discs of silicon, known as wafers. Each wafer has on it a large number of individual chips, which are processed together and later separated. Since shrinkage makes it possible to get more chips on a wafer, the cost per chip goes down.Falling unit cost was important to the industry because, if the latest chips are cheaper to make as well as faster, there is no reason to go on offering the old ones, at least not indefinitely. There can thus be one product for the entire market.However, detailed cost calculations showed that, in order to maintain this advantage as shrinkage proceeded beyond a certain point, it would be necessary to move to larger wafers. The increase in the size of wafers was no small matter. Originally, wafers were one or two inches in diameter, and by 2000 they were as much as twelve inches. At first, it puzzled me that, when shrinkage presented so many other problems, the industry should make things harder for itself by going to larger wafers. I now see that reducing unit cost was just as important to the industry as increasing the number of transistors on a chip, and that this justified the additional investment in foundries and the increased risk.The degree of integration is measured by the feature size, which, for a given technology, is best defined as the half the distance between wires in the densest chips made in that technology. At the present time, production of 90 nm chips is still building up Suspension of LawIn March 1997, Gordon Moore was a guest speaker at the celebrations of the centenary of the discovery of the electron held at the Cavendish Laboratory. It was during the course of his lecture that I first heard the fact that you can have silicon chips that are both fast and low in cost described as a violation of Murphy’s law.or Sod’s law as it is usually called in the UK.Moore said that experience in other fields would lead you to expect to have to choose between speed and cost, or to compromise between them. In fact, in the case of silicon chips, it is possible to have both.In a reference book available on the web, Murphy is identified as an engineer working on human acceleration tests for the US Air Force in 1949. However, we were perfectly familiar with the law in my student days, when we called it by a much more prosaic name than either of those mentioned above, namely, the Law of General Cussedness. We even had a mock examination question in which the law featured. It was the type of question in which the first part asks for a definition of some law or principle and the second part contains a problem to be solved with the aid of it. In our case the first part was to define the Law of General Cussedness and the second was the problem;A cyclist sets out on a circular cycling tour. Derive an equation giving the direction of the wind at any time.The single-chip computerAt each shrinkage the number of chips was reduced and there were fewer wires going from one chip to another. This led to an additional increment in overall speed, since the transmission of signals from one chip to another takes a long time.Eventually, shrinkage proceeded to the point at which the whole processor except for the caches could be put on one chip. This enabled a workstation to be built that out-performed the fastest minicomputer of the day, and the result was to kill the minicomputer stone dead. As we all know, this had severe consequences for the computer industry and for the people working in it.From the above time the high density CMOS silicon chip was Cock of the Roost. Shrinkage went on until millions of transistors could be put on a single chip and the speed went up in proportion.Processor designers began to experiment with new architectural features designed to give extra speed. One very successful experiment concerned methods for predicting the way program branches would go. It was a surprise to me how successful this was. It led to a significant speeding up of program execution and other forms of prediction followed Equally surprising is what it has been found possible to put on a single chip computer by way of advanced features. For example, features that had been developed for the IBM Model91.the giant computer at the top of the System 360 range.are now to be found on microcomputersMurphy’s Law remained in a state of suspension. No longer did it make sense to build experimental computers out of chips with a small scale of integration, such as that provided by the 7400 series. People who wanted to do hardware research at the circuit level had no option but to design chips and seek for ways to get them made. For a time, this was possible, if not easyUnfortunately, there has since been a dramatic increase in the cost of making chips, mainly because of the increased cost of making masks for lithography, a photographic process used in the manufacture of chips. It has, in consequence, again become very difficult to finance the making of research chips, and this is a currently cause for some concern.The Semiconductor Road MapThe extensive research and development work underlying the above advances has been made possible by a remarkable cooperative effort on the part of the international semiconductor industry.At one time US monopoly laws would probably have made it illegal for US companies to participate in such an effort. However about 1980 significant and far reaching changes took place in the laws. The concept of pre-competitive research was introduced. Companies can now collaborate at the pre-competitive stage and later go on to develop products of their own in the regular competitive manner.The agent by which the pre-competitive research in the semi-conductor industry is managed is known as the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA). This has been active as a US organisation since 1992 and it became international in 1998. Membership is open to any organisation that can contribute to the research effort.Every two years SIA produces a new version of a document known as the International Technological Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS), with an update in the intermediate years. The first volume bearing the title ‘Roadmap’ was issued in 1994 but two reports, written in 1992 and distributed in 1993, are regarded as the true beginning of the series.Successive roadmaps aim at providing the best available industrial consensus on the way that the industry should move forward. They set out in great detail.over a 15 year horizon. thetargets that must be achieved if the number of components on a chip is to be doubled every eighteen months.that is, if Moore’s law is to be maintained.-and if the cost per chip is to fall.In the case of some items, the way ahead is clear. In others, manufacturing problems are foreseen and solutions to them are known, although not yet fully worked out; these areas are coloured yellow in the tables. Areas for which problems are foreseen, but for which no manufacturable solutions are known, are coloured red. Red areas are referred to as Red Brick Walls.The targets set out in the Roadmaps have proved realistic as well as challenging, and the progress of the industry as a whole has followed the Roadmaps closely. This is a remarkable achievement and it may be said that the merits of cooperation and competition have been combined in an admirable manner.It is to be noted that the major strategic decisions affecting the progress of the industry have been taken at the pre-competitive level in relative openness, rather than behind closed doors. These include the progression to larger wafers.By 1995, I had begun to wonder exactly what would happen when the inevitable point was reached at which it became impossible to make transistors any smaller. My enquiries led me to visit ARPA headquarters in Washington DC, where I was given a copy of the recently produced Roadmap for 1994. This made it plain that serious problems would arise when a feature size of 100 nm was reached, an event projected to happen in 2007, with 70 nm following in 2010. The year for which the coming of 100 nm (or rather 90 nm) was projected was in later Roadmaps moved forward to 2004 and in the event the industry got there a little sooner.I presented the above information from the 1994 Roadmap, along with such other information that I could obtain, in a lecture to the IEE in London, entitled The CMOS end-point and related topics in Computing and delivered on 8 February 1996.The idea that I then had was that the end would be a direct consequence of the number of electrons available to represent a one being reduced from thousands to a few hundred. At this point statistical fluctuations would become troublesome, and thereafter the circuits would either fail to work, or if they did work would not be any faster. In fact the physical limitations that are now beginning to make themselves felt do not arise through shortage of electrons, butbecause the insulating layers on the chip have become so thin that leakage due to quantum mechanical tunnelling has become troublesome.There are many problems facing the chip manufacturer other than those that arise from fundamental physics, especially problems with lithography. In an update to the 2001 Roadmap published in 2002, it was stated that the continuation of progress at present rate will be at risk as we approach 2005 when the roadmap projects that progress will stall without research break-throughs in most technical areas “. This was the most specifi c statement about the Red Brick Wall, that had so far come from the SIA and it was a strong one. The 2003 Roadmap reinforces this statement by showing many areas marked red, indicating the existence of problems for which no manufacturable solutions are known.It is satisfactory to report that, so far, timely solutions have been found to all the problems encountered. The Roadmap is a remarkable document and, for all its frankness about the problems looming above, it radiates immense confidence. Prevailing opinion reflects that confidence and there is a general expectation that, by one means or another, shrinkage will continue, perhaps down to 45 nm or even less.However, costs will rise steeply and at an increasing rate. It is cost that will ultimately be seen as the reason for calling a halt. The exact point at which an industrial consensus is reached that the escalating costs can no longer be met will depend on the general economic climate as well as on the financial strength of the semiconductor industry itself.。