英文翻译2(格式)

- 格式:doc

- 大小:66.50 KB

- 文档页数:8

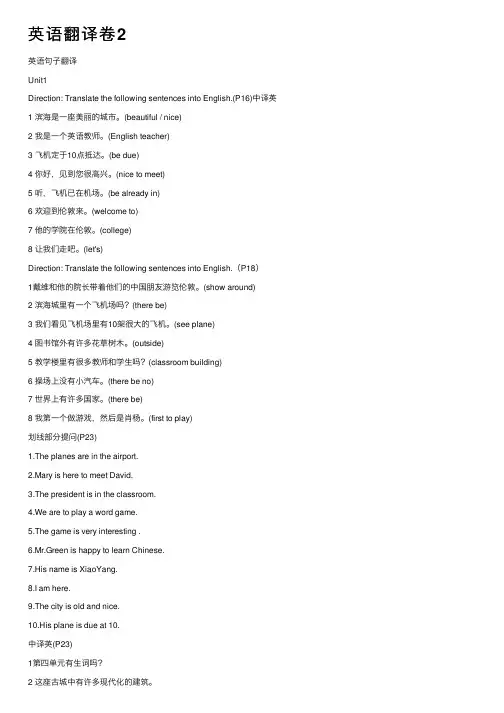

英语翻译卷2英语句⼦翻译Unit1Direction: Translate the following sentences into English.(P16)中译英1 滨海是⼀座美丽的城市。

(beautiful / nice)2 我是⼀个英语教师。

(English teacher)3 飞机定于10点抵达。

(be due)4 你好,见到您很⾼兴。

(nice to meet)5 听,飞机已在机场。

(be already in)6 欢迎到伦敦来。

(welcome to)7 他的学院在伦敦。

(college)8 让我们⾛吧。

(let's)Direction: Translate the following sentences into English.(P18)1戴维和他的院长带着他们的中国朋友游览伦敦。

(show around)2 滨海城⾥有⼀个飞机场吗?(there be)3 我们看见飞机场⾥有10架很⼤的飞机。

(see plane)4 图书馆外有许多花草树⽊。

(outside)5 教学楼⾥有很多教师和学⽣吗?(classroom building)6 操场上没有⼩汽车。

(there be no)7 世界上有许多国家。

(there be)8 我第⼀个做游戏,然后是肖杨。

(first to play)划线部分提问(P23)1.The planes are in the airport.2.Mary is here to meet David.3.The president is in the classroom.4.We are to play a word game.5.The game is very interesting .6.Mr.Green is happy to learn Chinese.7.His name is XiaoYang.8.I am here.9.The city is old and nice.10.His plane is due at 10.中译英(P23)1第四单元有⽣词吗?2 这座古城中有许多现代化的建筑。

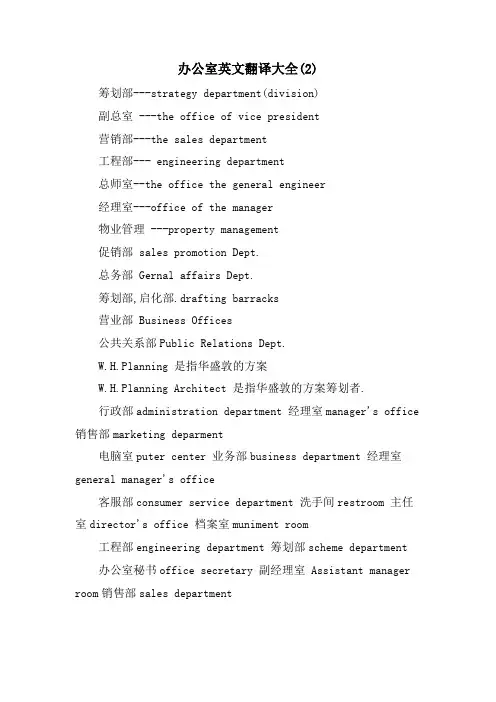

办公室英文翻译大全(2)筹划部---strategy department(division)副总室 ---the office of vice president营销部---the sales department工程部--- engineering department总师室--the office the general engineer经理室---office of the manager物业管理 ---property management促销部 sales promotion Dept.总务部 Gernal affairs Dept.筹划部,启化部.drafting barracks营业部 Business Offices公共关系部Public Relations Dept.W.H.Planning 是指华盛敦的方案W.H.Planning Architect 是指华盛敦的方案筹划者.行政部administration department 经理室manager's office 销售部marketing deparment电脑室puter center 业务部business department 经理室general manager's office客服部consumer service department 洗手间restroom 主任室director's office 档案室muniment room工程部engineering department 筹划部scheme department办公室秘书office secretary 副经理室 Assistant manager room销售部sales department培训部training department 采购部purchases department 茶水间tea room会议室conference rooms 接待区receptions areas 前台onstage弱电箱weak battery cases 员工区 work areas董事长 Board chairman 或者Chairman of the board营销总公司 sales general pany综合办公室主任 Director of Administration Office对外销售部经理 manager of Foreign sales department 或者Foreign sales manager电子商务部经理 manager of electronic merce department 或者electronic merce manager电子商务部副经理 deputy/vice manager of electronic merce department 或者electronic merce deputy/vice manager 市场筹划部副经理 deputy/vice manager of Marketing Department或者Marketing Department-Deputy Manager 客户效劳部经理 manager of customer service department 或者 customer service manager办事处主任 director of office 副总经理室 vice general manager网络市场部 works marketing room 技术质检部 technique and quality checking room会议室 meeting room 多功能厅 multi-usage room国际贸易部 international marketing department国内销售部 domestic sales department 洽谈室 chatting room 贵宾洽谈室 vip chating room生产部 production department 供给部 providing department男女洗手间 woman/man's toilet男浴室 man's washing room女浴室 woman's washing room总经办 General Administrative Office复印室 Copying Room 会议室 Boardroom 机房 Machine Room 信息部 Info. Dept. 人事部 HR Dept.财务结算室 Settlement Room 财务单证部 Document Dept.董事、总裁 President Office董事、副总裁 Director Office Vice-President Office总裁办公室President’s Assistant Office总裁办、党办President’s Assistant Office General Committee Office资产财务部 Finanical Dept.。

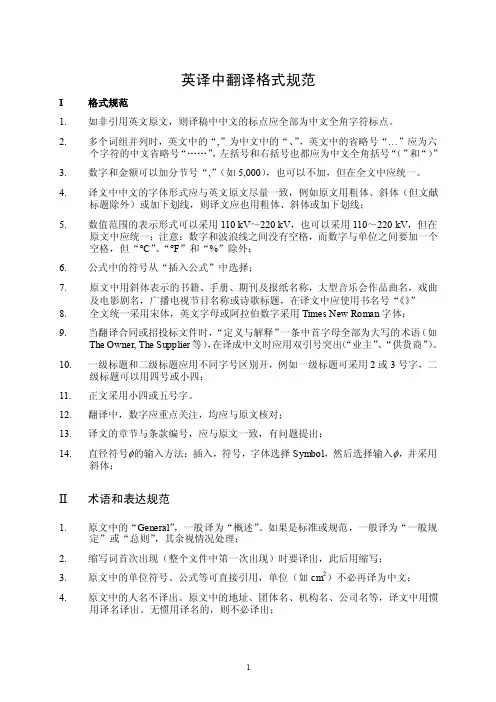

英译中翻译格式规范I 格式规范1. 如非引用英文原文,则译稿中中文的标点应全部为中文全角字符标点。

2. 多个词组并列时,英文中的“,”为中文中的“、”,英文中的省略号“…”应为六个字符的中文省略号“……”,左括号和右括号也都应为中文全角括号“(”和“)”3. 数字和金额可以加分节号“,”(如5,000),也可以不加,但在全文中应统一。

4. 译文中中文的字体形式应与英文原文尽量一致,例如原文用粗体、斜体(但文献标题除外)或加下划线,则译文应也用粗体、斜体或加下划线;5. 数值范围的表示形式可以采用110 kV~220 kV,也可以采用110~220 kV,但在原文中应统一;注意:数字和波浪线之间没有空格,而数字与单位之间要加一个空格,但“°C”、“°F”和“%”除外;6. 公式中的符号从“插入公式”中选择;7. 原文中用斜体表示的书籍、手册、期刊及报纸名称,大型音乐会作品曲名,戏曲及电影剧名,广播电视节目名称或诗歌标题,在译文中应使用书名号“《》”8. 全文统一采用宋体,英文字母或阿拉伯数字采用Times New Roman字体;9. 当翻译合同或招投标文件时,“定义与解释”一条中首字母全部为大写的术语(如The Owner, The Supplier等),在译成中文时应用双引号突出(“业主”、“供货商”)。

10. 一级标题和二级标题应用不同字号区别开,例如一级标题可采用2或3号字,二级标题可以用四号或小四;11. 正文采用小四或五号字。

12. 翻译中,数字应重点关注,均应与原文核对;13. 译文的章节与条款编号,应与原文一致,有问题提出;14. 直径符号φ的输入方法:插入,符号,字体选择Symbol,然后选择输入φ,并采用斜体;II 术语和表达规范1. 原文中的“General”,一般译为“概述”。

如果是标准或规范,一般译为“一般规定”或“总则”,其余视情况处理;2. 缩写词首次出现(整个文件中第一次出现)时要译出,此后用缩写;3. 原文中的单位符号、公式等可直接引用,单位(如cm2)不必再译为中文;4. 原文中的人名不译出。

盐城师范学院毕业论文(设计)外文资料翻译学院:(四号楷体_GB2312下同)专业班级:学生姓名:学号:指导教师:外文出处:(外文)(Times New Roman四号) 附件: 1.外文资料翻译译文; 2.外文原文1.外文资料翻译译文译文文章标题×××××××××正文×××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××………….*注:(本注释不是外文翻译的部分,只是本式样的说明解释)1. 译文文章标题为三号黑体居中,缩放、间距、位置标准,无首行缩进,无左右缩进,且前空(四号)两行,段前、段后各0.5行间距,行间距为1。

25倍多倍行距;2. 正文中标题为小四号,中文用黑体,英文用Times New Roman体,缩放、间距、位置标准,无左右缩进,无首行缩进,无悬挂式缩进,段前、段后0。

5行间距,行间距为1.25倍多倍行距;3。

正文在文章标题下空一行,为小四号,中文用宋体,英文用Times New Roman体,缩放、间距、位置标准,无左右缩进,首行缩进2字符(两个汉字),无悬挂式缩进,段前、段后间距无,行间距为1。

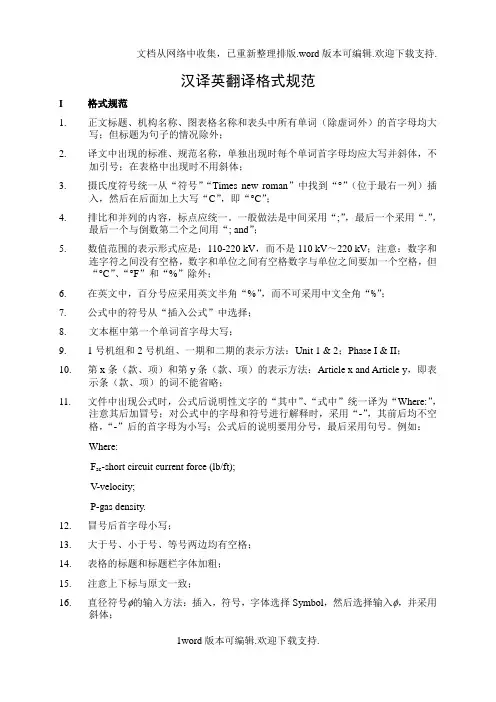

汉译英翻译格式规范I 格式规范1. 正文标题、机构名称、图表格名称和表头中所有单词(除虚词外)的首字母均大写;但标题为句子的情况除外;2. 译文中出现的标准、规范名称,单独出现时每个单词首字母均应大写并斜体,不加引号;在表格中出现时不用斜体;3. 摄氏度符号统一从“符号”“Times new roman”中找到“°”(位于最右一列)插入,然后在后面加上大写“C”,即“°C”;4. 排比和并列的内容,标点应统一。

一般做法是中间采用“;”,最后一个采用“.”,最后一个与倒数第二个之间用“; and”;5. 数值范围的表示形式应是:110-220 kV,而不是110 kV~220 kV;注意:数字和连字符之间没有空格,数字和单位之间有空格数字与单位之间要加一个空格,但“°C”、“°F”和“%”除外;6. 在英文中,百分号应采用英文半角“%”,而不可采用中文全角“%”;7. 公式中的符号从“插入公式”中选择;8. 文本框中第一个单词首字母大写;9. 1号机组和2号机组、一期和二期的表示方法:Unit 1 & 2;Phase I & II;10. 第x条(款、项)和第y条(款、项)的表示方法:Article x and Article y,即表示条(款、项)的词不能省略;11. 文件中出现公式时,公式后说明性文字的“其中”、“式中”统一译为“Where:”,注意其后加冒号;对公式中的字母和符号进行解释时,采用“-”,其前后均不空格,“-”后的首字母为小写;公式后的说明要用分号,最后采用句号。

例如:Where:F sc-short circuit current force (lb/ft);V-velocity;P-gas density.12. 冒号后首字母小写;13. 大于号、小于号、等号两边均有空格;14. 表格的标题和标题栏字体加粗;15. 注意上下标与原文一致;16. 直径符号φ的输入方法:插入,符号,字体选择Symbol,然后选择输入φ,并采用斜体;17. 日期按译文语言,应采用公历,按月、日、年顺序排列,例如,December 1, 2006;18. 译文的章节与条款编号,应与原文一致,有问题提出;19. 翻译中,数字应重点关注,均应与原文核对;20. 标点符号按英文惯例,英文中应全部采用英文半角符号,不得出现全角的顿号(、)逗号(,)句号(。

证书翻译件格式要求:中英文放在一张A4纸上,即:上半页为英文翻译,下半页为证书的复印件。

以下为各类证书的英文翻译模板,大家对应下载后可以修改各自证书中相关的个人信息及获奖情况,字的大小可以调整一下,落款日期一定要与证书上的颁发日期一致。

(温馨提示:各类奖学金证书翻译件办理费用均为8元一份,请按需挑选后办理。

)一、优秀毕业证书1.浙江省优秀毕业证书CERTIFICATE OF HONORMr. 姓名,You have been awarded the title of Graduate with Honor out of the graduates of Zhejiang Provincial Institutions of Higher Learning.The Educational Officeof Zhejiang ProvinceJune 20, 19992.学校优秀毕业证书1CERTIFICATE OF HONORThis is to certify that Mr. 姓名, a graduate of 1992, having studied in Chemical Engineering Department with a speciality of Polymer Chemical Engineering, has been awarded the title of Graduate with Honor in recognition of his outstanding performance during his enrollment in the undergraduate program.Lu YongxiangPresident of Zhejiang UniversityJune 26, 1992 学校优秀毕业证书2CERTIFICATE OF HONORThis is to certify that Mr. 姓名, a graduate of 2003, has been awarded the title of Graduate with Honor in recognition of his outstanding performance during his enrollment in the undergraduate program.Zhejiang UniversityJune 2003二、奖学金证书1. X等优秀学生奖学金(例:一等优秀学生奖学金)CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPMr. 姓名won the First Prize of Excellent Undergraduate Scholarship in the academic year of 1997-1998. This certificate is hereby awarded to him as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityDec. 1998注:原杭大、医大、农大各类奖学金证书翻译要加上四校合并说明,如下:CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPMs. 姓名won the Second Prize of Excellent Undergraduate Scholarship in the academic year of 1989-1990. This certificate is hereby awarded to her as an encouragement.Hangzhou UniversityOct. 1990Remarks: This is to certify that the four universities, Zhejiang University,Hangzhou University, Zhejiang Agricultural University andZhejiang Medical University, were merged into one:Zhejiang University on September 15, 1998.2. X等奖学金(例:三等奖学金)CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPThis is to certify that Mr. 姓名has got the third-grade scholarship in the academic year of 1986-1987. This certificate is hereby awarded to him as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityOctober 19874. 三好学生荣誉证书CERTIFICATE OF COMMENDATIONMr. 姓名won the title of Excellent All-round Student in the academic year of 1993-1994. This certificate of commendation is hereby awarded to him as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityNov. 19945. 优秀学生干部荣誉证书Certificate for the Excellent Cadre of StudentsThis is to certify that Mr. 姓名is admitted the Excellent Cadre of Students in the academic year of 1988-1989. This certificate is hereby awarded to him as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityDec., 19896. 成绩优秀单项奖CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPThis is to certify that Mr. 姓名has got the specialized scholarship of Excellent Achievements for the 1997-1998 academic year. This certificate is hereby awarded to him as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityDec. 19987. 新生优秀单项奖CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPThis is to certify that Ms. 姓名has got the specialized scholarship of Excellent Fresher for the 1988-1989 academic year. This certificate is hereby awarded to her as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityOct. 19888. 社会工作单项奖CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPThis is to certify that Mr. 姓名has got the specialized scholarship of Collective Duties for the 1993-1994 academic year. This certificate is hereby awarded to him as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityNov. 19949. 社会实践单项奖CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPThis is to certify that Ms. 姓名has got the specialized scholarship of Social Practice for the 1994-1995 academic year. This certificate is hereby awarded to her as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityDec. 199510. 教学实践单项奖CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPThis is to certify that Mr. 姓名has got the specialized scholarship of Teaching Practice for the 1990-1991 academic year. This certificate is hereby awarded to him as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityNov. 199111. 光华奖学金(其他专项奖学金将引号内黑体部分改一下即可):CERTIFICATE OF SCHOLARSHIPThis is to certify that Ms. 姓名has got the top-grade “Guanghua Scholarship” in the year of 1996. This certificate is hereby awarded to her as an encouragement.Zhejiang UniversityOct. 16, 1996三、辅修证书MINOR COURSE CERTIFICATEThis is to certify that Ms. Lu Yuehan, a student of the Department of Earth Science in grade 1996, minors in English from September 1997 to February 2000. She has completed and passed all the required courses of the minor program and is hereby awarded the Minor Course Certificate.Zhejiang UniversityApril 18, 2000Certificate No.: 20001011四、英语四、六级和计算机证书:1. 国家英语四、六级证书(以六级为例):CERTIFICATE FOR CET6This is to certify that Mr. 姓名, admitted to the Department of History, Zhejiang University in 1997, had passed the examination of College English Test (Band 6) in accordance with the requirements stipulated in the College English Instruction Programmer in June, 1999. He was awarded this certificate.Higher Educational Department ofThe National Education CommitteeDate: Sept. 1, 1999Registration No.: 99662301180101142. 浙江省计算机证书CERTIFICATEThis is to certify that Mr. 姓名, admitted to the Department of Energy Engineering, Zhejiang University in grade 1997, had passed the Zhejiang Provincial Uniform Examination of Basic Knowledge & Application Ability in C-Language for Non-professional Undergraduates in October, 1998. He was awarded this certificate.Zhejiang ProvincialEducation CommitteeDate: Dec. 1, 1998 Registration No.: 414174211。

英文翻译报告格式字体

格式设置如下:

1、字体为 Times New Roma,大小为12 font(也就是小四);

2、行距为1.5 或 2倍行距,段与段之间需要空一行;

3、对齐方式为左对齐或者两侧对齐(总之,左起必须顶格);

4、Reference(参考文献)必须另起一页,且不计入文章字数。

扩展资料

英语注释具体要求如下:

①在文中要有引用标注,如××× [1];

②如果重复出现同一作者的同一作品时,只注明作者的姓和引文所在页码(姓和页码之间加逗号);格式要求如下:

[1](空两格)作者名(名在前,姓在后,后加英文句号),书名(用斜体,后加英文句号),出版地(后加冒号),出版社或出版商(后加逗号),出版日期(后加逗号),页码(后加英文句号)。

[2](空两格)作者名(名在前,姓在后,后加英文句号),文章题目(文章题目用“”引起来)(空一格)紧接杂志名(用斜体,后加逗号),卷号(期号),出版年,起止页码,英文句号。

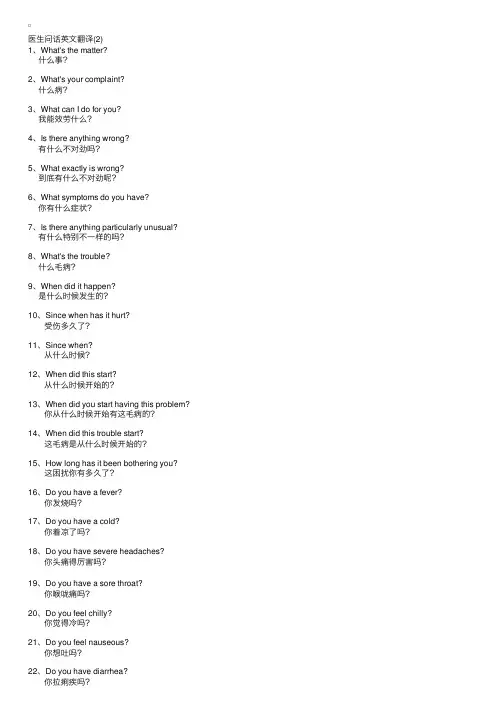

医⽣问话英⽂翻译(2)1、What's the matter? 什么事?2、What's your complaint? 什么病?3、What can I do for you? 我能效劳什么?4、Is there anything wrong? 有什么不对劲吗?5、What exactly is wrong? 到底有什么不对劲呢?6、What symptoms do you have? 你有什么症状?7、Is there anything particularly unusual? 有什么特别不⼀样的吗?8、What's the trouble? 什么⽑病?9、When did it happen? 是什么时候发⽣的?10、Since when has it hurt? 受伤多久了?11、Since when? 从什么时候?12、When did this start? 从什么时候开始的?13、When did you start having this problem? 你从什么时候开始有这⽑病的?14、When did this trouble start? 这⽑病是从什么时候开始的?15、How long has it been bothering you? 这困扰你有多久了?16、Do you have a fever? 你发烧吗?17、Do you have a cold? 你着凉了吗?18、Do you have severe headaches? 你头痛得厉害吗?19、Do you have a sore throat? 你喉咙痛吗?20、Do you feel chilly? 你觉得冷吗?21、Do you feel nauseous? 你想吐吗?22、Do you have diarrhea? 你拉痢疾吗?23、Have you ever coughed up blood or bloody phlegm? 你曾咳出⾎或痰中带⾎吗?24、Have you passed blood in your urine? 你⼩便带⾎吗?25、Are you taking any medicine regularly? 你通常吃什么药吗?26、Do you have any allergies? 你有什么过敏反应吗?27、How is your appetite? 你⾷欲如何?28、Do you often drink alcohol? 你常喝酒吗?29、Can you walk? 你能⾛路吗?。

英文Have you ever wondered what happens when you flip a switch to turn on a light, TV, vacuum cleaner or computer? In all of these cases, you are completing an electric circuit, allowing a current, or flow of electrons, through the wires. Circuits can be huge power systems transmitting megawatts of power over a thousand miles –or tiny microelectronic chips containing millions of transistors.This extraordinary shrinkage of electronic circuits made desktop computers possible. The new frontier promises to be nanoelectronic circuits with device sizes in the nanometers (one-billionth of a meter).There are many types of electrical and electronic power supplies, providing various alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) voltages for equipment operation.DC voltages are needed for most electronic circuits, and generally an electronic power supply is considered as a device that converts AC into DC.The AC voltage from the power lines can be rectified directly or passed through an isolation transformer ( a turn's ratio of 1:1). Depending on the value of DC voltage needed, the transformer may be of either a step-up or step-down type.(小四号字,单倍行距,首行缩进2个字符,不能定义文档网格。

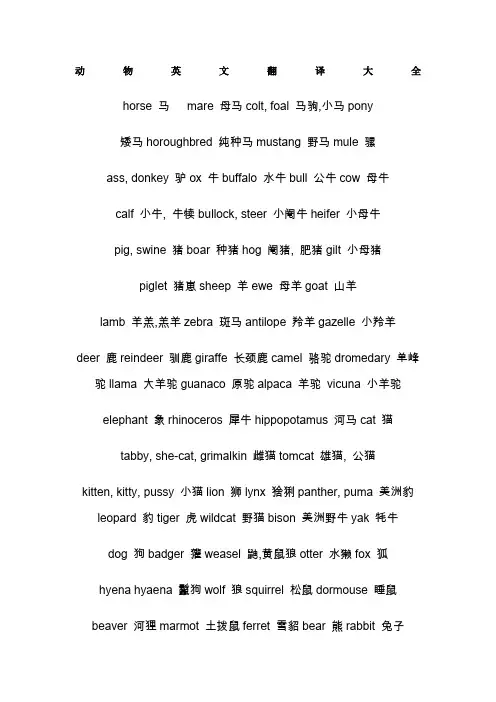

动物英文翻译大全horse 马mare 母马colt, foal 马驹,小马pony矮马horoughbred 纯种马mustang 野马mule 骡ass, donkey 驴ox 牛buffalo 水牛bull 公牛cow 母牛calf 小牛, 牛犊bullock, steer 小阉牛heifer 小母牛pig, swine 猪boar 种猪hog 阉猪, 肥猪gilt 小母猪piglet 猪崽sheep 羊ewe 母羊goat 山羊lamb 羊羔,羔羊zebra 斑马antilope 羚羊gazelle 小羚羊deer 鹿reindeer 驯鹿giraffe 长颈鹿camel 骆驼dromedary 单峰驼llama 大羊驼guanaco 原驼alpaca 羊驼vicuna 小羊驼elephant 象rhinoceros 犀牛hippopotamus 河马cat 猫tabby, she-cat, grimalkin 雌猫tomcat 雄猫, 公猫kitten, kitty, pussy 小猫lion 狮lynx 猞猁panther, puma 美洲豹leopard 豹tiger 虎wildcat 野猫bison 美洲野牛yak 牦牛dog 狗badger 獾weasel 鼬,黄鼠狼otter 水獭fox 狐hyena hyaena 鬣狗wolf 狼squirrel 松鼠dormouse 睡鼠beaver 河狸marmot 土拨鼠ferret 雪貂bear 熊rabbit 兔子hare 野兔rat 鼠chinchilla 南美栗鼠gopher 囊地鼠Guinea pig 豚鼠marmot 土拨鼠mole 鼹鼠mouse 家鼠vole 田鼠monkey 猴子chimpanzee 黑猩猩gorilla 大猩猩orangutan 猩猩gibbon 长臂猿sloth 獭猴anteater 食蚁兽duckbill, platypus 鸭嘴兽kangaroo 袋鼠koala 考拉, 树袋熊hedgehog 刺猬porcupine 箭猪, 豪猪bat 蝙蝠armadillo 犰狳whale 鲸dolphin 河豚porpoise 大西洋鼠海豚seal 海豹walrus 海象eagle 鹰bald eagle 白头鹰condor 秃鹰hawk, falcon 隼heron 苍鹰golden eagle 鹫kite 鹞vulture 秃鹫cock 公鸡hen 母鸡chicken 鸡, 雏鸡guinea, fowl 珍珠鸡turkey 火鸡peacock 孔雀duck 鸭mallard 野鸭, 凫teal 小野鸭gannet 塘鹅goose 鹅pelican 鹈鹕cormorant 鸬鹚swan 天鹅cob 雄天鹅cygnet 小天鹅gander, wild goose 雁dove 鸽pigeon 野鸽turtle dove 斑鸠pheasant 雉, 野鸡grouse 松鸡partridge 石鸡, 鹧鸪ptarmigan 雷鸟quail 鹌鹑ostrich 鸵鸟stork 鹳woodcock 山鹬snipe 鹬gull, seagull 海鸥albatross 信天翁kingfisher 翠鸟bird of paradise 极乐鸟, 天堂鸟woodpecker 啄木鸟parrot 鹦鹉cockatoo 大葵花鹦鹉macaw 金刚鹦鹉parakeet 长尾鹦鹉cuckoo 杜鹃,布谷鸟crow 乌鸦blackbird 乌鸫magpie 喜鹊swallow 燕子sparrow 麻雀nightingale 夜莺canary 金丝雀starling 八哥thrush 画眉oldfinch 金翅雀chaffinch 苍头燕雀robin 知更鸟plover 千鸟lark 百鸟,云雀swift 褐雨燕whitethroat 白喉雀hummingbird 蜂雀penguin 企鹅owl 枭,猫头鹰scops owl 角枭,耳鸟snake 蛇adder, viper 蝰蛇boa 王蛇cobra 眼镜蛇copperhead 美洲腹蛇coral snake 银环蛇grass snake 草蛇moccasin 嗜鱼蛇python 蟒蛇rattlesnake 响尾蛇lizard 蜥蜴tuatara 古蜥蜴chameleon 变色龙,避役iguana 鬣蜥wall lizard 壁虎salamander, triton, newt 蝾螈giant salamander 娃娃鱼, 鲵crocodile 鳄鱼, 非洲鳄alligator 短吻鳄, 美洲鳄caiman, cayman 凯门鳄gavial 印度鳄turtle 龟tortoise 玳瑁sea turtle 海龟frog 青蛙bullfrog 牛蛙toad 蟾蜍。

经贸英语翻译第2讲:规范格式1. 机构名称的翻译⏹机构名称在英语中属于专有名词范畴,其语用特征要求专词专用,所以一个机构只能使用一种译名(词语排列及组合、缩写形式都应该统一不变)。

例中国银行英译:the Bank of China缩写:B.O.C.而不能作任何更改,比如按字面译成:the Chinese Bank 或the China Bank,都是不妥当的。

How to translate工商局Commerce and Industry Bureau [CIB] 工商局◆Administration of Industry and Commerce ?◆Administration for Industry and Commerce?◆Bureau of Industry and Commerce?◆Industrial and Commercial Bureau?国家机关英译由于国家机关本身内涵的确定性及严肃性,所以在英译时更要注重法定依据或权威依据。

教材内容:中国历史博物馆(已改名:中国国家博物馆)The National Museum of China中华人民共和国商务部Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republi c of China国家外汇管理局State Administration of Foreign ExchangeSETC 国家经贸委State Economic and Trade CommissionCAAC 国家民航总局General Administration of Civil Aviation of China(Civil Aviation Administration of China )CNOOC 中国海洋石油总公司China National Offshore Oil Corp.CSRC 中国证券监督委员会(证监会)China Securities Regulatory Commission2. 公司名称、企业名称⏹有限责任公司Limited Liability Company (Co., Ltd.)⏹股份有限公司Company Limited by SharesWhat’s the difference between the two names?参阅:《中华人民共和国公司法》(Company Law of the P eople’s Republic of China)企业名称(CORPORATE NAME)构成:A + B + C + DA、B: 专有名称C、D:通名A:企业注册地址;B:企业专名;C:企业生产对象或经营范围;D:企业的性质(通常有总公司、公司、分公司、集团、股份有限公司、有限责任公司等)例:北京金洪恩电脑有限公司Beijing Golden Human Computer Co., Ltd.北京金洪恩电脑有限公司A B C D(专有名称)(通名)翻译方法:◆企业注册地址:(地名翻译原则处理)◆企业专名:(音译/意译,拼音/英语拼写方式)◆企业生产对象或经营范围:(意译)◆企业的性质:(意译:总/分公司、集团、股份有限公司、有限责任公司)例1 东方塑料工业公司B C DDongfang Plastics Industries例2 中国科学器材公司A C DChina Scientific Instruments & Materials Corporation不宜在同一个名称里使用两个―&‖符号,如:例3 中国工艺品进出口公司China National Arts and Crafts Import & Export Corporation例4中国石油天然气勘探开发公司China National Oil & Gas Exploration and Development Corporation(简称CNODC)例5 机械设备进出口公司Machinery & Equipment Import and Export Corporation ―公司‖ 的英译•firm•house•business•concern•combine•partnership•group•Consortium•establishment•venture•multinational•transnational•lines•agency•store•associates•system•officestore(s)百货公司Great Universal Store大世界百货公司(英)Tesco Stores (Holdings)坦斯科百货公司(英)联合公司中国农业机械进出口联合公司China Agricultural Machinery Import and Export Joint Company United Aircraft Corporation联合飞机公司(美)office公司(多与head,home branch等连用)例:3M中国有限公司广州分公司3M China Limited Guangzhou Branch Office―office‖不一定是―支公司‖head office:总公司home office:国内总公司branch office:分公司insurance office:保险公司例:中国图书进出口总公司China Books Import and Export Corporation (Head Office)Hong Kong Main Office香港總公司保险公司⏹Federal Insurance Corporation联邦保险公司(美)⏹Development Underwriting Ltd.开发保险公司(澳)⏹American International Assurance Co., Ltd.美国友邦保险公司⏹American International Underwriters Corporation美国国际保险公司实业公司1. 维世达实业公司WINSTAR INDUSTRIAL COMPANY2. 上海隆欣实业公司Shanghai Longxin Manufacturing Company3. 美国美联实业有限公司上海代表处Medline Industries, Inc. Shanghai Office―总公司‖之―总‖⏹General Transport Company运输总公司(英)⏹General American Transportation Corp.美国运输总公司⏹General Oil Company石油总公司(美)⏹Dollar General Corporation达乐公司(美)总公司不用general:珠海供水总公司Zhuhai Water Supply Company上海汽车工业(集团)总公司Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation (Group)原文:深圳市和盛达进出口贸易有限公司参考答案:Shenzhen Heshengda Import & Export Co., Ltd.Ex –公司、企业名称的翻译(1)⏹江门市大长江集团有限公司⏹三菱重工金羚空调器有限公司⏹广州市永信药业有限公司⏹江门市新会区康美制品有限公司⏹无锡明达电器有限公司Reference answers:1. Jiangmen Dachangjiang Group Co., Ltd.2. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. - Jinling Air Conditioners Co., Ltd.3. Guangzhou Winsun Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.4. Hommy Enterprise (Xinhui) Co., Ltd.5. Wuxi Mind Electric Co., Ltd.Ex –公司、企业名称的翻译(2)1. 中国有色金属建设股份有限公司China Nonferrous Metal Industry’s Foreign Engineering & Construction Co., Ltd.2. 中国成套设备进出口(集团)总公司CHINA NATIONAL COMPLETE PLANT IMPORT & EXPORT CORPORA TION (GROUP)3. 中国供销合作对外贸易公司CHINA SUPPLY AND MARKETING COOPERATIVE FOREIGN TRADE CORPORATION 3. 职务职称机构、职务职称英译通则―总‖ 、―副‖字的翻译•总会计师Chief Accountant•总建筑师Chief Architect•总设计师Chief Designer•总工程师Chief Engineer;Engineer-in-Chief2)用general 或-general•总会计师General Accountant•总代理商General Agent•总领事General Consul / Consul-General•总设计师General Designer•总稽查Auditor-General3)用专门的词来表示总裁Chairman;President总监;总管 Controller―副‖字的翻译1) “副”宜译为deputy,例如:副区长deputy district mayor,副主任deputy director,副处长deputy division director副秘书长deputy secretary-general副主任deputy director副处长deputy division chief副科长deputy section chief2) 用vice来翻译部分―副‖职按照惯例可译为vice。

汉译英翻译格式规范I 格式规范1. 正文标题、机构名称、图表格名称和表头中所有单词(除虚词外)的首字母均大写;但标题为句子的情况除外;2. 译文中出现的标准、规范名称,单独出现时每个单词首字母均应大写并斜体,不加引号;在表格中出现时不用斜体;3. 摄氏度符号统一从“符号”“Times new roman”中找到“°”(位于最右一列)插入,然后在后面加上大写“C”,即“°C”;4. 排比和并列的内容,标点应统一。

一般做法是中间采用“;”,最后一个采用“.”,最后一个与倒数第二个之间用“; and”;5. 数值范围的表示形式应是:110-220 kV,而不是110 kV~220 kV;注意:数字和连字符之间没有空格,数字和单位之间有空格数字与单位之间要加一个空格,但“°C”、“°F”和“%”除外;6. 在英文中,百分号应采用英文半角“%”,而不可采用中文全角“%”;7. 公式中的符号从“插入公式”中选择;8. 文本框中第一个单词首字母大写;9. 1号机组和2号机组、一期和二期的表示方法:Unit 1 & 2;Phase I & II;10. 第x条(款、项)和第y条(款、项)的表示方法:Article x and Article y,即表示条(款、项)的词不能省略;11. 文件中出现公式时,公式后说明性文字的“其中”、“式中”统一译为“Where:”,注意其后加冒号;对公式中的字母和符号进行解释时,采用“-”,其前后均不空格,“-”后的首字母为小写;公式后的说明要用分号,最后采用句号。

例如:Where:F sc-short circuit current force (lb/ft);V-velocity;P-gas density.12. 冒号后首字母小写;13. 大于号、小于号、等号两边均有空格;14. 表格的标题和标题栏字体加粗;15. 注意上下标与原文一致;16. 直径符号φ的输入方法:插入,符号,字体选择Symbol,然后选择输入φ,并采用斜体;17. 日期按译文语言,应采用公历,按月、日、年顺序排列,例如,December 1, 2006;18. 译文的章节与条款编号,应与原文一致,有问题提出;19. 翻译中,数字应重点关注,均应与原文核对;20. 标点符号按英文惯例,英文中应全部采用英文半角符号,不得出现全角的顿号(、)逗号(,)句号(。

英文The intelligence lives at home, or called the intelligent housing, take the housing as a platform, has both the construction, the network correspondence, the information electrical appliances, the equipment automation, the collection system, the structure, the service, the management is a body highly effective, comfortable, safe, convenient, the environmental protection environment, reveals family's in each kind of equipment (for example sound video equipment, lighting system, window blind control, air conditioning control, peacefully guards against conveniently system, digital theater system, network electrical appliances and so on) connects through the family network together.With lives at home ordinary compares, not only the intelligence lives at home has the traditional housing function, provides the comfortable security, the high grade also the pleasant family life space; Also for has by the original passive static structural transformation can move the wisdom the tool, provides the omni-directional information interactive function, helps the family to be unimpeded with exterior maintenance communication, optimizes people's life style, helps the people to arrange the time, the enhancement to live at home effectively the life security, even saves the fund for each kind of energy expense.A lot of people in the smart-home may be the concern of all come from wealthy families abroad, smart homes, the owner of the car door just entering homes, sensors have been to send information to the control center, and the lighting in the room, air-conditioning, sound system, corresponding to the State. As long as at the door a little pause, and the fingerprint scanner, and dilated pupils identify monitoring devices such as servers have been identified as the door, and should be chosen either for owner of the cell phone visited on strangers sending the message ... all of this is not a science fiction scenario, the existing technology can achieve. It is now all the intelligent home appliances are becoming more and more, before leaving for work to rice cooker can be timed, and when you come back to Rice before, and it is better for the air-conditioned, with a time out before you, in the indoor temperature regulation of the cool, pleasant ...Before the smart home made a similar concepts such as intelligent home, network, home, and with the advances in technology and people to improve the quality of our living environment, smart home has now started to gradually integrate the alarm system, electric automatic control, and security features such as network access, the purpose of which is to enable users to be more involved with safe and comfortable.Around with common of target, some traditional of IT manufacturers made has to computer for core to established intelligent home of programme, it of advantage is can with computer powerful of processing ability to completed more complex of task, but exists with various electric Zhijian of connection standard does not unified, computer how and refrigerator, and air conditioning established contact which? course cannot with we habits of USB mouth to connection, and currently in domestic also no formed industry Union to specification and developed related of standard, different manufacturers launched of overall solution programme all does not same, Lack of interchangeability.But by traditional electricities and the labor and so on some such as wonderful the victory electric appliance controls the plan which the enterprise promotes to take the electrical automation extremely the realization, to the control which lives at home mainly by the inductor and the power supply control center completes, has the maturer stable movement quality, but insufficiently is intelligent for human's feeling, for instance mostly is closes and opens two ways to a lamp control, but is unable to realize does not come together according to the natural light and the daily schedule the true intelligent adjustment.The intelligence lives at home the prospect forecast Along with people living standard unceasing enhancement, the people unceasing to the environment proposed a higher request, more and more pays great attention to in the family life each member comfortable, is safe andis convenient, therefore looked from the market demand angle, the intelligence lives at home is inevitably the prospect is broad.Statistics have indicated, in recent years electrician profession year sales volume 40--6,000,000,000 Y uan, in which upscale product sales volume near 2,000,000,000 Yuan.Looked from the market development angle that, take the intelligent network switch as representative's new electrician product market share can year by year the fast enlargement, and finally substitutes traditional the electrician product, here is breeding the huge opportunity.At present, national real estate industry thriving, intelligent community has become a fundamental requirement, coupled with smart home, "smart" concept will inevitably bring new selling points and vitality to the real estate industry, so "smart" is the theme of the 21st century real estate developers push. From the viewpoint of environment for the growth of the market, now annual proportion of construction of digital home in China has accounted for about 30% of the total amount of new housing, according to the country's "2010 Chinese cities of 60% House to achieve intelligent" digital home of the development goals, we believe that the development and construction of China digital home to increasing at an annual rate of 6%.According to the survey, more than 1.3 billion people, China now has more than 100 million home automation home customers, this group is equivalent to half of Europe, form a huge, fashion market. In this market, average family spends $ 1000 per year, there is a $ 100 billion market. In fact, market research data show that belongs to the perceptual and secondary consumers annually spend much more than $ 1000 per person in the home. Therefore, how to stand up in this market position, favorable terrain, on whether to hold a long-term, once and for all opportunities.The intelligence lives at home is the people pursues the high quality life manifesting, is the comfortable life, simple life speaking on another's behalf, its existence will raise people habits and customs inevitably.As people people economic ability of increasingly upgrade, people also began on material living increasingly concern has, in life products of select Shang has has is large of improve, plus city construction pace of increasingly speed up and, intelligent curtains has entered has we of life, such as some Office, and hotel which curtains as decoration not missing of part, increasingly hot up, intelligent curtains has is good of market prospects.The 21st century are the technical time, the intelligent window blind has the very good market prospect, but our commonly used window blind track all is the steel wire pulls the type or the rail track type, only then a station part high income family uses is the electric remote control track, these tracks mainly are by places such as Taiwan and Guangdong produce, the price is quite expensive.If but new intelligent window blind maneuver box function also approximately same, but the price is low, installs the use safely convenient, becomes the family to spin the window blind market a big luminescent spot.The intelligent window blind has the very good market prospect, along with the technical development, the lives of the people and the working condition progressive improvement, the electrically operated window blind more and more manner accepts, in Europe and America and so on the developed country, the electrically operated window blind has widely applied.Not only the electrically operated window blind product has realized electrically operated, but also can through infrared, the radio telecontrol or the timed control realization automation, moreover may utilize electronic inductors and so on the sunlight, temperature, wind, the realization product intellectualized operation, reduced people's labor intensity, lengthened the window blind product service life.Now, the electrically operated window blind has become the modern upscale housing, the guesthouse, the intelligent building, multimedia central, the private villa and so on the first choice automation window decorations!More and more receives the application along with the network media which the people consummate, causes present this society to start to march into the intelligent time, future verywill be many with the life related industry, all will be take the technical intelligence as the development foundation, will take in the life the important composition intelligent window blind although in price not biggest superiority, but the future intelligence time demand had decided this road will be best walksThis design plans the electrically operated window blind intelligent function through the analysis electrically operated window blind development and the present situation, thus carries on the design to the electrically operated window blind es step-by-steps the electrical machinery to take the functional element, examines the part by the photoresistance as the sensing part sensor achievement, the 89C51 monolithic integrated circuit took the control chip, the supplementary key-board and the demonstration, has finally realized the electrically operated window blind controller many intelligent project.The main chapter divides into:(1) introduction: Introduction design goal domestic and foreign development present situation and research significance goal, design basic content and this article chapter arrangement. (2) overall project design: Has given the electrically operated window blind controller ideas for overall concepts, the intelligent project, with design structure plan.(3) hardware design: Selects the 89C51 monolithic integrated circuit for the core each kind of circuit design, including repositions the electric circuit, the power circuit, the clock electric circuit, step-by-steps the electrical machinery control circuit, the keyboard/Display circuit and so on a series of related electric circuits.(4) software design: Mainly introduced each function design flow.(5) summary and forecastThe electrically operated window blind controller overall concept design is the determination can satisfy the design request the overall concept link.This chapter embarked from the system function demand, plans and had determined the system overall structure, and has considered the system extendibility and the realizability in this foundation.Along with lives of the people level unceasing enhancement, the people are more and more intense to the family life comfortable demand, the window blind took in each family life most must lives at home one of things, also needs to meet a people's more comfortable naturally need.The window blind most basic function nothing but is protects owner's individual privacy as well as the visor keeps off functions and so on dust, but the traditional window blind you must manual go to the switch, every day early opens the late pass also is very troublesome, specially villa or multiple room big window blind, quite long, moreover heavy, with when needs the very big strength to be able the switch window blind, is not specially convenient; Therefore the electrically operated window blind arises at the historic moment.The existing electrically operated window blind all may start automatically closes the window blind, but to the time automatic control window blind switch, has been possible to act according to the light their also some shortcomings.How does the window blind controller autoswitch let the window blind be able the switch freely, whether the engine off time does arrive.Below the electrically operated window blind mainly has several big functions: (1) hand control: This function enable the electrically operated window blind to have the manual main story, the manual reverse and the manual stop function.Moreover increased the active status to instruct, electrical machinery work in main story, reverse and stopped state time, the nixietube had the different active status instruction.(2) semiautomatic hand control: The semiautomatic hand control is in needs to close or to turn on the window blind time, after only needs artificially to press “the clockwise” or “the reverse” the pressed key, window blind arriving automatic stop.(3) environment beam control: The window blind closure and opening completes the window blind automatically through the environment brightness opening or the button-up operations control, “darkness closure, dawn opens” has the intelligent managem ent, does not have the misoperation.(4) time automatic control: According to establishment inputopening or the closing hour, control the window blind the closure and open.The window blind clockwise, the reverse and the stop function may control by the mo nolithic integrated circuit power output step-by-step the electrical machinery revolution to realize.The environment brightness control and transports through the photoresistance puts the composition the electric circuit to control the monolithic integrated circuit power output subsequently to control the electrical machinery the clockwise and the reverse.The time automatic control may control by the timerThroughout the entire design system, SCM uses the familiar 89C51 single-chip, all well known so that the entire chip. Familiar with the control chip design is also handy. Chip used by simple, practical, reduce development and hardware cost. Sensor parts using photosensitive resistance, continuous detection of ambient light intensity changes, after passing the bridge circuit signals into the comparator, it can be concluded that a signal, this signal is amplified, a/d converted into single-chip, pulsed signal which in turn by single-chip microcomputer control stepping motor running. Design of stepping motor is a good implementation of SCM command. For a digital servo stepping motor actuators, simple structure, reliable operation, easy to control, control as well as good performance. Curtain switch of more accurate, stable. Clock circuit design combined with single chip timing function, coupled with optic sensors detecting light intensity very good solution to control this feature.In the design of this system, the face of a variety of test objects and a large number of control units, using a variety of interface standards and the mcu to connect, after mcu data processing, real-time monitoring and control. At a time using single-chip implementation of a smart home control system not only has a convenient, simple, and flexible acquisition and control, and can significantly increase the recovery of the coordination of each module and chip, which greatly improve system availability. The system design system is the use of the advantages of at89c51 microcontroller successfully completed the requirements of this design. And learning timing and automatic control functions provide a good foundation for the control of household equipment.Telephone remote control as a relatively new subject to conventional means of a remote control than a show of superiority, and do not require special wiring, do not use radio frequency resources, avoid the electromagnetic pollution. Also, because the phone line over the Internet, you can take full advantage of existing telephone network, so remote distance can be cross-province, and even across country. Another telephone is a duplex means of communication. Therefore, this can greatly reflects the use of the phone for remote control of greater superiority. Operator can be provided in a variety of prompts an immediate understanding of the controlled object related information to further action. Some topics Phone remote control has been involved in, but there is also limited to laboratory, and from the actual applications, especially for everyday life there are some gaps, and do not fully reflect the phone remotely duplex traffic characteristics. This design it is in this context has been a major improvement, take one piece and make use of different tones for different actions to achieve prompt and status to the prosecution of feedback, thus allowing the operator to be able to follow the information the prosecution, to get the product to interactive and intelligent. But the design of the debugging is on-line debugging, and has been in the telecommunications, rail links to be able to successfully switch labs and the use of mobile phones.中文智能家居,或称智能住宅,以住宅为平台,兼备建筑、网络通信、信息家电、设备自动化,集系统、结构、服务、管理为一体的高效、舒适、安全、便利、环保的居住环境,尽显便捷将家中的各种设备(如音视频设备、照明系统、窗帘控制、空调控制、安防系统、数字影院系统、网络家电等)通过家庭网络连接到一起。

英语句子翻译(2)英语句子翻译(2)1.Man-made and natural disasters have disrupted the Government's economic plans.天灾人祸打乱了政府的经济计划。

2.She told the court she would give a full explanation of the prosecution's decision on Monday.她告诉法庭她会在星期一对原告方的决定作出全面解释。

3.Patriotic songs have long been a feature of Kuwaiti life.爱国歌曲长期以来一直是科威特生活的一个特色。

4.He seemed a dynamic and energetic leader.他似乎是一个富有干劲、精力充沛的领导。

5.Free enterprise, he argued, was compatible with Russian values and traditions.他认为自由企业制并不违背俄罗斯的价值观和传统。

6. A seconds-based timeout is also used in this loop to reset the knock sequences after sufficient delay.在这个循环中还使用了一个基于秒的超时,在足够的延时之后重置敲打序列。

7.He was executed by lethal injection earlier today.他于今天早些时候被注射处死。

8.New ways to treat arthritis may provide an alternative to painkillers.关节炎的新疗法可能是止痛药之外的另一种选择。

9.The credit card business is down, and more borrowers are defaulting on loans.信用卡业务出现了下滑,而且越来越多的借款者都不按期还款。

英文翻译B《Mode choice of university students commuting to school and the role of active travel》Author:Kate E. Whalen, Antonio Páez, Juan A. Carrasco School of Geography and Earth Sciences, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4K1, CanadaDept. of Civil Engineering, Universidad de Concepción, P.O. Box 160-C,Concepción, ChileAvailable online 9 July 2013大学生去学校和旅游活动模式选择的作用突出点学生选择活动出行的比一般人群更普遍。

多项logit离散选择模型是用来识别影响模态选择的因素。

街道密集增加了电动模式的选择率。

更高的人行道密度减少了机动模式的概率。

我们找到一个由汽车和自行车旅游时间的积极效用。

摘要近年来,有旅游兴趣的学生越来越多。

已经指出,学生倾向于使用各种运输方式,包括积极的旅行,比其他人群更频繁。

调查大学生的模态的选择提供了一个独特的机会来了解人口的大部分活跃的在一个主要trip-generating位置的通勤者。

反过来,这可以对影响活跃旅游的因素提供宝贵的见解。

在本文中,我们报告一个在大学生中模式选择分析的结果,使用在加拿大汉密尔顿的麦克马斯特大学为例。

这项研究的结果表明,成本的结合,个人态度,环境因素如街道和人行道密度是影响模态的选择的因素。

一个关键发现是,由汽车和自行车旅行时间积极影响这些模式的工具,尽管旅行时间以递减的速率增加。

而旅行时间的积极效用的汽车已经被堵在哪里,我们的分析证明骑自行车的人随处可去。

交通政策措施的例子需要进行考虑。

背景为了有效地定位我们的研究在现有文献中,它是有用的考虑两个维度的分析:方法和变量。

第一个维度,先前的论文模态选择的学生使用描述性统计和多变量分析。

变量的分析而言,周(2012)确定了6类变量用于研究的模式选择:(1)细化因素(如社会经济和人口);(2)心理因素(例如态度);(3)使用模式特定因素(如旅行、舒适);(4)特征(特定的模式,如成本);(5)建筑环境和城市形态变量(如密度、十字路口);(6)TDM的措施(如停车成本)。

探索性数据分析使用描述性统计是一个宝贵的锻炼,帮助分析师识别值得注意的特征数据,编码错误或异常值(海宁et al .,1998)。

探索性数据分析本身在发展中工作假设可能导致重要的见解。

例如,Delmelle和Delmelle(2012,第4页)提供方式比例的样本使用七socio-demographic类(男/女,和五个学生类别从大一到毕业/法律系学生)。

因此,可以断言,“车”和“走”是最普遍的模式,由socio-demographic类变化。

这样,男性驾车出行的比例是0.332,而女性是0.376。

研究生或法律学生乘汽车旅行的比例是0.272。

虽然这表明性别差异,也报告了模态分离特性的示例使用两个维度:状态(人员/学生)大学校园和基于距离的三个地区。

单独的一个限制使用描述性统计是统计学意义的因素被认为影响模式选择的不能确定,同时控制了潜在的混杂因素。

相比之下,其他研究已经使用多元技术分析模式的选择。

Klockner和Friedrichsmeier(2011)使用一个多层次结构方程模型,而周(2012)估计的多项物流模型有五个不同的模式。

Klockner Friedrichsmeier(2011)显示,多变量模型可以量化变量组合预测的变化模式,或计算边际影响使用多项logit模型的系数(无论Ben-Akiva和勒曼,1985)来评估一个变量的变化如何影响的概率选择模式。

在所有需要考虑的变量中,首先由一个结果变量。

例如,Klockner和Friedrichsmeier(2011)在倒塌的选择设置为一个二进制的情况,即汽车/其他模式(如自行车、散步,和交通)。

这时请注意,这简化了分析(见266页),这也让人无法评估影响因素单独的每个替代模式。

相比之下, 周(2012)估计五个不同的多项物流模型模式,包括,有趣的是,远程办公。

已知个人因素(社会经济、人口统计和心理)影响旅游行为。

一般文献表明,有男性和女性的旅游行为的差异。

金姆和Ulfarsson(2008)发现,女性比男性有更高比例的短汽车旅行。

运输方式差异也明显。

Gatersleben和阿普尔顿(2007)发现,自行车是常见的男性比女性多。

这一发现被证实男人更喜欢骑自行车,而女性更喜欢走路,在一项研究中评估了性别之间的联系当地基础设施和交通步行和骑自行车。

还表明,这可能是由于女性从家里由于家庭和家庭责任的情感感知安全和访问设施选择较短的距离。

复制了这些关注学生发现的一些研究。

Delmelle 和Delmelle(2012)也报告在他们的研究中对女性相对于男性比例较低的步行和骑自行车。

同样,周(2012)发现,男性更有可能步行或骑自行车相对于女性,但没有发现性别差异对任何其他的模式的影响。

家庭结构也是影响旅游行为。

曹 (2009)发现,数百个有一岁以下儿童家庭的数量会减少汽车旅行的频率,这可能是由于时间限制和孩子的不便,而金正日和Ulfarsson(2008)报告说,孩子的存在比没有孩子的家庭更大的延误走路。

接近这个主题,Delmelle和Delmelle(2012)报告说,儿童的数量与学生驾驶的概率呈正相关,但与步行和骑自行车的概率负相关。

在Klockner Friedrichsmeier或周的报告中,家庭变量不被认作是学生模态选择的影响因素。

心理因素被认为影响旅游模式一般(Van Acker et al .,2010和Van Acker et al .,2011)。

事实上, Klockner和Friedrichsmeier(2011)专注于汽车使用的心理因素,并包括一组丰富的态度,社会规范,有意的变量。

鉴于本文的重点,作者明确放弃任何考虑成本变量(p。

264)。

这是不幸的,因为成本变量已知影响使用的各种模式,并由于相关变量遗漏偏差有可能混淆的结果。

相反,周(2012)认为成本变量,但不是态度或其他心理因素。

Delmelle(2012)包括语句引起态度的反应,这对行为变化进行探讨,以确定潜在的激励因素。

各种模式的成本是模态选择的一个重要组成部分。

一般来说,文学提供了证据表明,人们希望限制他们花的时间旅行和访问他们的运输方式。

根据Mackett(2003),时间约束和旅行时间高居榜首的原因是旅行者使用汽车。

通常距离是被认为是模式选择的因素。

例如,Shannon (2006) 在他们的研究中考虑三个距离区域(< 1公里,> 1公里,< 8公里,> 8公里),而Delmelle和Delmelle(2012) 根据距离校园的远近使用一个累积分布阴谋探索模态的选择。

这两项研究发现,驾车旅行者比例的增加迅速增加距离。

虽然直观,使用距离有点简单。

在一个探索性的设置,它留下了一个疑惑:为什么游客在相同的距离可能会选择不同的模式(例如:见图 3 Delmelle Delmelle,2012)。

在建模环境中,使用距离(对于所有模式都是一样的)成为细化变量而不是一个模式——或者trip-specific变量,因此不能代表旅行准确的特点,即相对成本的模式。

在周(2012)的情况下,距离作为“成本”(在现实中,一个细化)多项logit模型变量,结果很难解释:骑自行车/步行距离系数并不显著,这意味着距离相对于距离没有影响(或者,换句话说,相当于独自驾车和拼车)。

在模态选择的分析,我们认为,这段时间或许货币成本概念和实践方面优于距离评估旅行的费用。

下一组变量与建筑环境和城市形态。

早期证据模式选择和城市环境之间的关系表明,建立行人活动的密度与更高的股票影响选择(Cervero Gorham,1995)。

某些形式的网络设计(即基于网格)也被证明增加行走模式的选择(Cervero Kockelman,1997)。

这些结果从最近其他交通研究中得到了证实。

例如,曹et al .(2009)报告说,居民在城市环境中更容易步行或骑自行车,一定程度上是由于混合土地使用支持步行和骑自行车旅行和阻止汽车旅行。

与此一致的是,金正日和Ulfarsson(2008)提供的证据表明,短的汽车旅行经常在城市化地区观察到,相比短巴士旅行和散步旅行更频繁的城市化地区。

马歇尔和灰吕(2010)发现,活动方式的分享旅行在加州的城市正受到街和交叉口密度的影响,但是如果涉及的街道主要道路会减少。

在学生中模态的选择,Delmelle和Delmelle(2012)发现,女性更有可能根据地形作为活跃的屏障模式,相对于男性。

唉,其他student-related研究综述(即Klockner Friedrichsmeier,2011年,Shannon et al .,2006,,2012)不考虑建筑环境变量。

最后,对TDM措施,Shannon et al(2006) 于停车,改变校园/淋浴设施,停车设施探讨应对态度声明关。

Delmelle和Delmelle(2012)报告说,学生在应对国家增加停车价格愿意转变模式;然而,从他们的探索性分析目前尚不清楚这是否响应将同时考虑其他潜在因素影响模式选择。

周(2012)调查停车许可证持有的影响,并发现选择人车辆以外的所有模式减少的概率。

Klockner和Friedrichsmeier(2011),另一方面,不考虑任何TDM措施分析。

在下面,我们调查学生使用的模态选择多项logit离散选择模型,考虑两个机动(汽车和交通)和两个活动模式(步行和骑自行车)。

解释变量被认为是个体社会经济、人口和态度。

我们还包括模式——和trip-specific因素、变量相关的建筑环境,和TDM的措施。

因此,我们分析了每一类周(2012)所做的报告。

原文BMode choice of university students commuting to school and the role of active travelKate E. Whalen, Antonio Páez, Juan A. CarrascoHighlightsActive modes of travel are more prevalent among students than in the general population.A multinomial logit discrete choice model is used to identify the factors that influence modal choices.Higher street network density increases the probability of using motorized modes. Higher sidewalk density decreases the probability of using motorized modes.We find a positive utility of travel time by car and bicycle.AbstractIn recent years, interest in the travel behavior of students in institutions of higher education has grown. It has been noted that students tend to use a variety of transportation modes, including active travel, more frequently than other population segments. Investigating the modal choice of university students provides a unique opportunity to understand a population that has a large proportion of active commuters at a major trip-generating location. In turn, this can provide valuable insights into the factors that influence active travel. In this paper, we report the results of a mode choice analysis among university students, using as a case study McMaster University, in Hamilton, Canada. The results from this research indicate that modal choices are influenced by a combination of cost, individual attitudes, and environmental factors such as street and sidewalk density. A key finding is that travel time by car and bicycle positively affect the utilities of these modes, although at a decreasing rate as travel time increases. While the positive utility of time spent traveling by car has been documented in other settings, our analysis provides evidence of the intrinsic value that cyclists place on their trip experience. Examples of transportation policy measures suggested by the analysis are discussed.KeywordsMode choice; University students; Active travel; Positive utility of time; Discrete choice modelBackgroundIn order to position our study effectively within the context of the existing literature, it is useful to consider two dimensions of the analysis: the methods used and the variables considered. Along the first dimension, previous papers on modal choices of students have used descriptive statistics and/or multivariate analysis. In terms of thevariables for the analysis,Zhou (2012) identifies six classes of variables used in the study of mode choices: (1) individual-specific factors (e.g. socio-economic and demographic); (2) psychological factors (e.g. attitudes); (3) mode-specific factors (e.g., comfort); (4) trip characteristics (specific to a mode, such as cost); (5) built environment and urban form variables (e.g., density, intersections); and (6) presence of TDM measures (e.g., parking cost).Exploratory data analysis using descriptive statistics is a valuable exercise that helps analysts identify noteworthy characteristics of the data, coding errors, or outliers (Haining et al., 1998). By itself, exploratory data analysis can lead to important insights in developing working hypotheses. For example, Delmelle and Delmelle (2012, p.4) provide mode-choice proportions for their sample using seven socio-demographic classes (male/female, and five student categories from freshman to graduate/law student). Thus, it is possible to assert that “car” and “walk” are the most prevalent modes, with variations by socio-demographic class. In this way, the proportion of males traveling by car is 0.332 whereas for females it is 0.376. The proportion of graduate or law students traveling by car is 0.272. While this suggests gender differences, it is not possible to assess the probability of walking for a female who is also a graduate student relative to a male who is a freshman. Shannon et al. (2006) also report the modal split characteristics of their sample using two dimensions: status at the university (staff/student) and three zones based on distance to campus. A limitation of the use of descriptive statistics alone is that the statistical significance of the factors thought to influence the choice of mode cannot be determined while controlling for potential confounders. Other studies, in contrast, have used multivariate techniques to analyze mode choices. Klockner and Friedrichsmeier (2011) used a multilevel structural equation model, whereas Zhou (2012) estimated a multinomial logistic model for five different modes. With multivariate models, as Klockner and Friedrichsmeier (2011) show, it is possible to quantify how variables combine to predict variations in mode use, or to calculate marginal effects using the coefficients of a multinomial logit model (q.v. Ben-Akiva and Lerman, 1985) to evaluate how changes in one variable influence the probability of selecting a mode.In terms of the variables considered, there is first the outcome variable. Klockner and Friedrichsmeier (2011), for instance, collapsed the choice set to a binary situation, namely car/other modes (i.e. cycling, walking, and transit). While they note that this simplifies the analysis (see p. 266), it also makes it impossible to assess the factors that affect each of the alternative modes individually. Zhou (2012), in contrast, estimated a multinomial logistic model for five different modes, including, interestingly, telecommuting.Individual factors (socio-economic, demographic, and psychological) are known to influence travel behavior. The literature in general shows that there are differences in the travel behavior of men and women. Kim and Ulfarsson (2008) found that females have a higher proportion of short automobile trips than males. Differences are also apparent with respect to active modes of transportation. Gatersleben and Appleton (2007) find that cycling is more common among men than women. This finding is corroborated by Stronegger et al. (2010), who find that men preferred cycling, whilewomen preferred walking, in a study that assessed gender-specific links between local infrastructure and amount of walking and cycling for transportation. Stronegger et al. (2010) also suggest that this is perhaps due to women’s feelings of perceived safety and choosing to access amenities at shorter distances from home due to household and family responsibilities. Some of these findings are replicated in studies that focused on students. Delmelle and Delmelle (2012) also report in their study lower walking and cycling proportions for females relative to males. Likewise,Zhou (2012) finds that males are more likely to walk or cycle relative to females, but finds no gender differences for any of the other modes.Household structure is also known to impact travel behavior. Cao et al. (2009) find that the number of children under the age of five in a household tends to reduce the auto trip frequency, which may be due to time constraints and the inconveniences of taking children out, whereas Kim and Ulfarsson (2008) report that the presence of children is linked to a greater aversion to walking compared to families without children. Closer to the subject at hand, Delmelle and Delmelle (2012) report that the number of children is positively correlated with the probability of students driving, but negatively correlated with the probability of walking and cycling. Household variables are not considered by Shannon et al., 2006 and Klockner and Friedrichsmeier, 2011, or Zhou (2012) in their investigations of modal choices by students.Psychological factors are increasingly recognized in the travel behavior literature in general (Van Acker et al., 2010 and V an Acker et al., 2011). Indeed, the study by Klockner and Friedrichsmeier (2011) concentrates on the psychological factors of car use, and includes a rich set of attitudinal, social norms, and intentional variables. Given the focus of the paper, the authors explicitly forego any consideration of cost variables (p. 264). This is unfortunate, because cost variables are known to influence the use of various modes, and potentially confound the results due to omitted relevant variable bias. Contrariwise, Zhou (2012)considers cost variables, but not attitudinal or other psychometric factors. Both Shannon et al. (2006) and Delmelle and Delmelle (2012) include statements that elicited attitudinal responses, which are explored to identify potential motivators for behavioral change. The effect of attitudinal factors has otherwise been observed in smaller scale, qualitative research on cycling, which shows that those who have adopted cycling as a mode choice have positive perceptions of cyclists and cycling in general, compared with those who have not adopted cycling as a form of transportation (Gatersleben and Appleton, 2007 and Gatersleben and Haddad, 2010). The effect has not, to our knowledge, been observed before in larger statistical samples.The cost of the various modes is an important component of modal choice. In general, the literature provides evidence that people wish to limit the amount of time they spend traveling and accessing their mode of transportation. According to Mackett (2003), time constraints and travel time rank high on the list of reasons for travelers to use a car. Typically, time or monetary costs are used, although in some cases distance has been considered instead. For instance, Shannon et al. (2006) consider three distance zones in their study (<1 km, >1 km and <8 km, and >8 km), whereas Delmelle and Delmelle (2012) use a cumulative distribution plot to explore modal choices accordingto distance to campus. Both studies find that the proportion of travelers moving by car increases rapidly with increasing distance. Although intuitive, the use of distance is somewhat simplistic. In an exploratory setting, it leaves open the question of why travelers at the same distance might choose different modes (e.g. see Fig. 3 in Delmelle and Delmelle, 2012). In a modeling setting, the use of distance (which is identical for all modes) becomes an individual-specific variable instead of a mode- or trip-specific variable, and thus fails to represent the characteristics of the trip accurately, namely the relative cost by mode. In the case of Zhou (2012), where distance is used as a “cost” (in reality, an individual-specific) variable in a multinomial logit model, the results are difficult to interpret: the coefficient for cycling/walking distance is not significant, which means that distance has no effect relative to (or, in other words, is equivalent to) distance by car (driving-alone and carpool). It is our view, in modal choice analysis, that time or monetary costs are conceptually and practically superior to distance in terms of evaluating the cost of travel.The next set of variables relates to the built environment and urban form. Early evidence about the relationship between mode choice and the urban environment suggests that built density is associated with higher shares of pedestrian activity (Cervero and Gorham, 1995). Certain forms of network design (i.e. grid-based) have also been shown to increase walking (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997). These results find confirmation in other recent transportation research. For instance, Cao et al. (2009) report that residents in urban environments are more likely to walk or cycle, partly due to mixed land uses that support walking and biking trips and discourage auto trips. Consistent with this, Kim and Ulfarsson (2008) provide evidence that short automobile trips are observed more often in less urbanized areas, compared to short bus trips and walking trips that are more frequent in urbanized areas. Marshall and Garrick (2010) find that the share of active modes of travel in a selection of cities in California is positively affected by street and intersection density, but tends to decrease if the streets involved are major roads. In the case of student modal choice, Delmelle and Delmelle (2012) find that females are more likely to report topography as a barrier for active modes, relative to males. Alas, other student-related studies reviewed here (i.e. Klockner and Friedrichsmeier, 2011, Shannon et al., 2006 and Zhou, 2012) do not consider built environment variables.Finally, with respect to TDM measures, Shannon et al. (2006) explore the responses to attitudinal statements regarding access to parking, changing/shower facilities on campus, and parking facilities. Delmelle and Delmelle (2012) report that students state a willingness to shift modes in response to increases in parking prices; however, it is not clear from their exploratory analysis whether this response would hold while considering other potential factors that influence mode choice. Zhou (2012) investigates the effect of parking permit possession, and finds that it decreases the probability of selecting all modes other than single-occupant vehicle. Klockner and Friedrichsmeier (2011), on the other hand, do not consider any TDM measures in their analysis.In what follows, we investigate the modal choice of students using a multinomial logit discrete choice model, considering two motorized (car and transit) and two active modes (walking and cycling). The explanatory variables considered are individualsocio-economic, demographic, and attitudinal. We also include mode- and trip-specific factors, variables related to the built environment, and the presence of TDM measures. Thus, our analysis covers every category of those identified by Zhou (2012).。