2016 美国2型糖尿病综合管理方案图表

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1.77 MB

- 文档页数:11

84 ENDOCRINE PRACTICE Vol 22 No. 1 January 2016AACE/ACE Consensus StatementCONSENSUS STATEMENT BY THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS AND AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY ON THE COMPREHENSIVE TYPE 2 DIABETES MANAGEMENT ALGORITHM – 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARYAlan J. Garber, MD, PhD, FACE 1; Martin J. Abrahamson, MD 2; Joshua I. Barzilay, MD, FACE 3; Lawrence Blonde, MD, FACP , FACE 4; Zachary T. Bloomgarden, MD, MACE 5; Michael A. Bush, MD 6;Samuel Dagogo-Jack, MD, DM, FRCP , FACE 7; Ralph A. DeFronzo, MD, BMS, MS, BS 8;Daniel Einhorn, MD, FACP , FACE 9; Vivian A. Fonseca, MD, FACE 10; Jeffrey R. Garber, MD, FACP , FACE 11; W. Timothy Garvey, MD, FACE 12;George Grunberger, MD, FACP , FACE 13; Yehuda Handelsman, MD, FACP , FNLA, FACE 14;Robert R. Henry, MD, FACE 15; Irl B. Hirsch, MD 16;Paul S. Jellinger, MD, MACE 17; Janet B. McGill, MD, FACE 18; Jeffrey I. Mechanick, MD, FACN, FACP , FACE, ECNU 19;Paul D. Rosenblit, MD, PhD, FNLA, FACE 20; Guillermo E. Umpierrez, MD, FACP , FACE 21From the 1Chair, Professor, Departments of Medicine, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and Molecular and Cellular Biology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 2Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Department of Medicine and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, 3Division of Endocrinology, Kaiser Permanente of Georgia and the Division of Endocrinology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, 4Director, Ochsner Diabetes Clinical Research Unit, Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, 5Clinical Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Editor, Journal of Diabetes , New York, New York, 6Clinical Chief, Division of Endocrinology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine, Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Los Angeles, California, 7A.C. Mullins Professor & Director, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, 8Professor of Medicine, Chief, Diabetes Division, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, 9Immediate Past President, American College of Endocrinology, Past-President, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Medical Director, Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute, Clinical Professor of Medicine, UCSD, Associate Editor, Journal of Diabetes , Diabetes and Endocrine Associates, La Jolla, California, 10Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology, Tullis Tulane Alumni Chair in Diabetes, Chief, Section of Endocrinology, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, 11Endocrine Division, Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, Boston, Massachusetts, Division of Endocrinology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, 12Professor and Chair, Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Director, UABThis document represents the official position of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology. Where there were no randomized controlled trials or specific U.S. FDA labeling for issues in clinical practice, the participating clinical experts utilized their judgment and experience. Every effort was made to achieve consensus among the committee members. Position statements are meant to provide guidance, but they are not to be consid -ered prescriptive for any individual patient and cannot replace the judgment of a clinician.Diabetes Research Center, Mountain Brook, Alabama, 13Grunberger Diabetes Institute, Clinical Professor, Internal Medicine and Molecular Medicine & Genetics, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, 14Medical Director & Principal Investigator, Metabolic Institute of America, President, American College of Endocrinology, Tarzana, California, 15Professor of Medicine, University of California San Diego, Chief, Section of Diabetes, Endocrinology & Metabolism, VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, California, 16Professor of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington, 17Professor of Clinical Medicine, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, The Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care, Hollywood, Florida, 18Professor of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism & Lipid Research, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, 19Clinical Professor of Medicine, Director, Metabolic Support, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Bone Disease, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, 20Clinical Professor, Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, University California Irvine School of Medicine, Irvine, California, Co-Director, Diabetes Out-Patient Clinic, UCI Medical Center, Orange, California, Director & Principal Investigator, Diabetes/Lipid Management & Research Center, Huntington Beach, California, and 21Professor of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Director, Endocrinology Section, Grady Health System, Atlanta, Georgia.Address correspondence to American Association of ClinicalEndocrinologists, 245 Riverside Avenue, Suite 200, Jacksonville, FL 32202. E-mail: publications@. DOI: 10.4158/EP151126.CSTo purchase reprints of this article, please visit: /reprints.Copyright © 2016 AACE.85Abbreviations:A1C= hemoglobin A1C; AACE= American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; ACCORD = Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes; ACCORD BP= Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Blood Pressure; ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AGI = alpha-glucosidase inhibitor; apo B = apolipoprotein B; ARB = angiotensin II receptor blocker; ASCVD= atherosclerotic cardio-vascular disease; BAS = bile acid sequestrant; BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; CHD = coro-nary heart disease; CKD= chronic kidney disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DKA = diabetic ketoac-idosis; DPP-4 = dipeptidyl peptidase 4; EPA = eicosa-pentaenoic acid; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; GLP-1= glucagon-like peptide 1; HDL-C= high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-P = low-density-lipopro-tein particle; Look AHEAD = Look Action for Health in Diabetes; NPH = neutral protamine Hagedorn; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; SFU = sulfonylurea; SGLT-2 = sodium glucose cotransporter-2; SMBG = self-moni-toring of blood glucose; T2D = type 2 diabetes; TZD = thiazolidinedioneEXECUTIVE SUMMARYThis algorithm for the comprehensive management of persons with type 2 diabetes (T2D) was developed to provide clinicians with a practical guide that considers the whole patient, their spectrum of risks and complica-tions, and evidence-based approaches to treatment. It is now clear that the progressive pancreatic beta-cell defect that drives the deterioration of metabolic control over time begins early and may be present before the diagnosis of diabetes (1). In addition to advocating glycemic control to reduce microvascular complications, this document high-lights obesity and prediabetes as underlying risk factors for the development of T2D and associated macrovascular complications. In addition, the algorithm provides recom-mendations for blood pressure (BP) and lipid control, the two most important risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD).Since originally drafted in 2013, the algorithm has been updated as new therapies, management approach-es, and important clinical data have emerged. The 2016 edition includes a new section on lifestyle therapy as well as discussion of all classes of obesity, antihyperglycemic, lipid-lowering, and antihypertensive medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through December 2015.This algorithm supplements the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and A merican College of Endocrinology (ACE) 2015 Clinical Practice Guidelines for Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan (2) and is organized into discrete sections that address the following topics: the founding principles of the algo-rithm, lifestyle therapy, obesity, prediabetes, glucose control with noninsulin antihyperglycemic agents and insulin, management of hypertension, and management of dyslipidemia. In the accompanying algorithm, a chart summarizing the attributes of each antihyperglycemic class and the principles of the algorithm appear at the end. (Endocr Pract. 2016;22:84-113)PrinciplesThe founding principles of the Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm are as follows (see Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—Principles):1. Lifestyle optimization is essential for all patientswith diabetes. Lifestyle optimization is multifac-eted, ongoing, and should engage the entire diabe-tes team. However, such efforts should not delayneeded pharmacotherapy, which can be initiatedsimultaneously and adjusted based on patientresponse to lifestyle efforts. The need for medicaltherapy should not be interpreted as a failure oflifestyle management, but as an adjunct to it.2. The hemoglobin A1C (A1C) target should beindividualized based on numerous factors, such asage, life expectancy, comorbid conditions, dura-tion of diabetes, risk of hypoglycemia or adverseconsequences from hypoglycemia, patient moti-vation, and adherence. An A1C level of ≤6.5% isconsidered optimal if it can be achieved in a safeand affordable manner, but higher targets maybe appropriate for certain individuals and maychange for a given individual over time.3. Glycemic control targets include fasting and post-prandial glucose as determined by self-monitor-ing of blood glucose (SMBG).4. The choice of diabetes therapies must be individu-alized based on attributes specific to both patientsand the medications themselves. Medication attri-butes that affect this choice include antihyper-glycemic efficacy, mechanism of action, risk ofinducing hypoglycemia, risk of weight gain, otheradverse effects, tolerability, ease of use, likelyadherence, cost, and safety in heart, kidney, orliver disease.5. Minimizing risk of both severe and nonseverehypoglycemia is a priority. It is a matter of safety,adherence, and cost.6. Minimizing risk of weight gain is also a priority.It too is a matter of safety, adherence, and cost.7. The initial acquisition cost of medications is onlya part of the total cost of care, which includesmonitoring requirements and risks of hypoglyce-86mia and weight gain. Safety and efficacy shouldbe given higher priority than medication cost.8. This algorithm stratifies choice of therapies basedon initial A1C level. It provides guidance as towhat therapies to initiate and add but respectsindividual circumstances that could lead to differ-ent choices.9. Combination therapy is usually required andshould involve agents with complementary mech-anisms of action.10. Comprehensive management includes lipid andBP therapies and treatment of related comorbidi-ties.11. Therapy must be evaluated frequently (e.g., every3 months) until stable using multiple criteria,including A1C, SMBG records (fasting and post-prandial), documented and suspected hypoglyce-mia events, lipid and BP values, adverse events(weight gain, fluid retention, hepatic or renalimpairment, or CVD), comorbidities, other rele-vant laboratory data, concomitant drug adminis-tration, diabetic complications, and psychosocialfactors affecting patient care. Less frequent moni-toring is acceptable once targets are achieved.12. The therapeutic regimen should be as simple aspossible to optimize adherence.13. This algorithm includes every FDA-approved classof medications for T2D (as of December 2015).Lifestyle TherapyThe key components of lifestyle therapy include medical nutrition therapy, regular physical activity, suffi-cient amounts of sleep, behavioral support, and smok-ing cessation and avoidance of all tobacco products (see Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—Lifestyle Therapy). In the algorithm, recommendations appearing on the left apply to all patients. Patients with increasing burden of obesity or related comorbidities may also require the additional interventions listed in the middle and right side of the figure.Lifestyle therapy begins with nutrition counseling and education. All patients should strive to attain and maintain an optimal weight through a primarily plant-based diet high in polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, with limited intake of saturated fatty acids and avoidance of trans fats. Patients who are overweight (body mass index [BMI] of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥30 kg/ m2) should also restrict their caloric intake with the goal of reducing body weight by at least 5 to 10%. As shown in the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) and Diabetes Prevention Program studies, lowering caloric intake is the main driver for weight loss (3-6). The clini-cian or a registered dietitian (or nutritionist) should discuss recommendations in plain language at the initial visit and periodically during follow-up office visits. Discussion should focus on foods that promote health versus those that promote metabolic disease or complications and should include information on specific foods, meal plan-ning, grocery shopping, and dining-out strategies. In addi-tion, education on medical nutrition therapy for patients with diabetes should also address the need for consisten-cy in day-to-day carbohydrate intake, limiting sucrose-containing or high-glycemic-index foods, and adjusting insulin doses to match carbohydrate intake (e.g., use of carbohydrate counting with glucose monitoring) (2,7). Structured counseling (e.g., weekly or monthly sessions with a specific weight-loss curriculum) and meal replace-ment programs have been shown to be more effective than standard in-office counseling (3,6,8-15). Additional nutri-tion recommendations can be found in the 2013 Clinical Practice Guidelines for Healthy Eating for the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic and Endocrine Diseases in Adults from AACE/ACE and The Obesity Society (16).After nutrition, physical activity is the main compo-nent in weight loss and maintenance programs. Regular physical exercise—both aerobic exercise and strength training—improves glucose control, lipid levels, and BP; decreases the risk of falls and fractures; and improves functional capacity and sense of well-being (17-24). In Look AHEAD, which had a weekly goal of ≥175 minutes per week of moderately intense activity, minutes of physi-cal activity were significantly associated with weight loss, suggesting that those who were more active lost more weight (3). The physical activity regimen should involve at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity exer-cise such as brisk walking (e.g., 15- to 20-minute mile) and strength training; patients should start any new activity slowly and increase intensity and duration gradually as they become accustomed to the exercise. Structured programs can help patients learn proper technique, establish goals, and stay motivated. Patients with diabetes and/or severe obesity or complications should be evaluated for contrain-dications and/or limitations to increased physical activity, and an exercise prescription should be developed for each patient according to both goals and limitations. More detail on the benefits and risks of physical activity and the practi-cal aspects of implementing a training program in people with T2D can be found in a joint position statement from the American College of Sports Medicine and American Diabetes Association (25).Adequate rest is important for maintaining energy levels and well-being, and all patients should be advised to sleep approximately 7 hours per night. Evidence supports an association of 6 to 9 hours of sleep per night with a reduction in cardiometabolic risk factors, whereas sleep deprivation aggravates insulin resistance, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia and increases inflamma-tory cytokines (26-31). Daytime drowsiness—a frequent symptom of sleep disorders such as sleep apnea—is asso-ciated with increased risk of accidents, errors in judgment,87and diminished performance (32). The most common type of sleep apnea, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), is caused by physical obstruction of the airway during sleep. The resulting lack of oxygen causes the patient to awaken and snore, snort, and grunt throughout the night. The awaken-ings may happen hundreds of times per night, often with-out the patient’s awareness. OSA is more common in men, the elderly, and persons with obesity (33,34). Individuals with suspected OSA should be referred to a sleep specialist for evaluation and treatment (2).Behavioral support for lifestyle therapy includes the structured weight loss and physical activity programs mentioned above as well as support from family and friends. Patients should be encouraged to join commu-nity groups dedicated to a healthy lifestyle for emotional support and motivation. In addition, obesity and diabetes are associated with high rates of anxiety and depression, which can adversely affect outcomes (35,36). Healthcare professionals should assess patients’ mood and psycho-logical well-being and refer patients with mood disorders to mental healthcare professionals. Cognitive behavior-al therapy may be beneficial. A recent meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions provides insight into successful approaches (37).Smoking cessation is the final component of lifestyle therapy and involves avoidance of all tobacco products. Structured programs should be recommended for patients unable to stop smoking on their own (2).ObesityObesity is a disease with genetic, environmental, and behavioral determinants that confers increased morbidity and mortality (38,39). An evidence-based approach to the treatment of obesity incorporates lifestyle, medical, and surgical options, balances risks and benefits, and empha-sizes medical outcomes that address the complications of obesity rather than cosmetic goals. Weight loss should be considered in all overweight and obese patients with prediabetes or T2D, given the known therapeutic effects of weight loss to lower glycemia, improve the lipid profile, reduce BP, and decrease mechanical strain on the lower extremities (hips and knees) (2,38).The AACE Obesity Treatment Algorithm emphasizes a complications-centric model as opposed to a BMI-centric approach for the treatment of patients who have obesity or are overweight (see Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—Complications-Centric Model for Care of the Overweight/Obese Patient). The patients who will benefit most from medical and surgical interven-tion have obesity-related comorbidities that can be clas-sified into 2 general categories: insulin resistance/cardio-metabolic disease and biomechanical consequences of excess body weight (40). Clinicians should evaluate and stage patients for each category. The presence and severity of complications, regardless of patient BMI, should guide treatment planning and evaluation (41,42). Once these factors are assessed, clinicians can set therapeutic goals and select appropriate types and intensities of treatment that will help patients achieve their weight-loss goals. Patients should be periodically reassessed (ideally every 3 months) to determine if targets for improvement have been reached; if not, weight loss therapy should be changed or intensi-fied. Lifestyle therapy can be recommended for all patients with overweight or obesity, and more intensive options can be prescribed for patients with comorbidities. For exam-ple, weight-loss medications can be used in combination with lifestyle therapy for all patients with a BMI ≥27 kg/ m2 and comorbidities. As of 2015, the FDA has approved 8 drugs as adjuncts to lifestyle therapy in patients with over-weight or obesity. Diethylproprion, phendimetrazine, and phentermine are approved for short-term (a few weeks) use, whereas orlistat, phentermine/topiramate extended release (ER), lorcaserin, naltrexone/bupropion, and liraglutide 3 mg may be used for long-term weight-reduction therapy. In clinical trials, the 5 drugs approved for long-term use were associated with statistically significant weight loss (placebo-adjusted decreases ranged from 2.9% with orlistat to 9.7% with phentermine/topiramate ER) after 1 year of treatment. These agents improve BP and lipids, prevent progression to diabetes during trial periods, and improve glycemic control and lipids in patients with T2D (43-60). Bariatric surgery should be considered for adult patients with a BMI ≥35 kg/ m2 and comorbidities, especially if therapeutic goals have not been reached using other modalities (2,61).PrediabetesPrediabetes reflects failing pancreatic islet beta-cell compensation for an underlying state of insulin resistance, most commonly caused by excess body weight or obesity. Current criteria for the diagnosis of prediabetes include impaired glucose tolerance, impaired fasting glucose, or metabolic syndrome (see Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—Prediabetes Algorithm). Any one of these factors is associated with a 5-fold increase in future T2D risk (62).The primary goal of prediabetes management is weight loss. Whether achieved through lifestyle therapy, pharma-cotherapy, surgery, or some combination thereof, weight loss reduces insulin resistance and can effectively prevent progression to diabetes as well as improve plasma lipid profile and BP (44,48,49,51,53,60,63). However, weight loss may not directly address the pathogenesis of declining beta-cell function. When indicated, bariatric surgery can be highly effective in preventing progression from prediabe-tes to T2D (62).No medications (either weight loss drugs or antihy-perglycemic agents) are approved by the FDA solely for the management of prediabetes and/or the prevention of T2D. However, antihyperglycemic medications such as metformin and acarbose reduce the risk of future diabetes88in prediabetic patients by 25 to 30%. Both medications are relatively well-tolerated and safe, and they may confer a cardiovascular risk benefit (63-66). In clinical trials, thia-zolidinediones (TZDs) prevented future development of diabetes in 60 to 75% of subjects with prediabetes, but this class of drugs has been associated with a number of adverse outcomes (67-69). Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists may be equally effective, as demon-strated by the profound effect of liraglutide 3 mg in safely preventing diabetes and restoring normoglycemia in the vast majority of subjects with prediabetes (59,60,70,71). However, owing to the lack of long-term safety data on the GLP-1 receptor agonists and the known adverse effects of the TZDs, these agents should be considered only for patients at the greatest risk of developing future diabetes and those failing more conventional therapies.As with diabetes, prediabetes increases the risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Patients with prediabetes should be offered lifestyle therapy and pharmacotherapy to achieve lipid and BP targets that will reduce ASCVD risk.T2D PharmacotherapyIn patients with T2D, achieving the glucose target and A1C goal requires a nuanced approach that balances age, comorbidities, and hypoglycemia risk (2). The AACE supports an A1C goal of ≤6.5% for most patients and a goal of >6.5% (up to 8%; see below) if the lower target cannot be achieved without adverse outcomes (see Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—Goals for Glycemic Control). Significant reductions in the risk or progression of nephropathy were seen in the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation (ADV ANCE) study, which targeted an A1C <6.5% in the intensive therapy group versus standard approaches (72). In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial, inten-sive glycemic control significantly reduced the risk and/ or progression of retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy (73,74). However, in ACCORD, which involved older and middle-aged patients with longstanding T2D who were at high risk for or had established CVD and a baseline A1C >8.5%, patients randomized to intensive glucose-lowering therapy (A1C target of <6.0%) had increased mortality (75). The excess mortality occurred only in patients whose A1C remained >7% despite intensive therapy, whereas in the standard therapy group (A1C target 7 to 8%), mortality followed a U-shaped curve with increasing death rates at both low (<7%) and high (>8%) A1C levels (76). In contrast, in the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial (V ADT), which had a higher A1C target for intensively treated patients (1.5% lower than the standard treatment group), there were no between-group differences in CVD endpoints, cardiovas-cular death, or overall death during the 5.6-year study period (75,77). After approximately 10 years, however, V ADT patients participating in an observational follow-up study were 17% less likely to have a major cardiovascu-lar event if they received intensive therapy during the trial (P<.04; 8.6 fewer cardiovascular events per 1,000 person-years), whereas mortality risk remained the same between treatment groups (78). Severe hypoglycemia occurs more frequently with intensive glycemic control (72,75,77,79). In ACCORD, severe hypoglycemia may have account-ed for a substantial portion of excess mortality among patients receiving intensive therapy, although the hazard ratio for hypoglycemia-associated deaths was higher in the standard treatment group (80). Cardiovascular auto-nomic neuropathy may be another useful predictor of cardiovascular risk, and a combination of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (81) and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy increase the odds ratio to 4.55 for CVD and mortality (82).Taken together, this evidence supports individualization of glycemic goals (2). In adults with recent onset of T2D and no clinically significant CVD, an A1C between 6.0 and 6.5%, if achieved without substantial hypoglycemia or other unacceptable consequences, may reduce lifetime risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications. A broader A1C range may be suitable for older patients and those at risk for hypoglycemia. A less stringent A1C of 7.0 to 8.0% is appropriate for patients with history of severe hypoglycemia, limited life expectancy, advanced renal disease or macro-vascular complications, extensive comorbid conditions, or long-standing T2D in which the A1C goal has been diffi-cult to attain despite intensive efforts, so long as the patient remains free of polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, or other hyperglycemia-associated symptoms. Therefore, selection of glucose-lowering agents should consider a patient’s ther-apeutic goal, age, and other factors that impose limitations on treatment, as well as the attributes and adverse effects of each regimen. Regardless of the treatment selected, patients must be followed regularly and closely to ensure that glyce-mic goals are met and maintained.The order of agents in each column of the Glucose Control Algorithm suggests a hierarchy of recommended usage, and the length of each line reflects the strength of the expert consensus recommendation (see Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—Glycemic Control Algorithm). Each medication’s properties should be considered when selecting a therapy for individual patients (see Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—Profiles of Antidiabetic Medications), and healthcare professionals should consult the FDA prescrib-ing information for each agent.• Metformin has a low risk of hypoglycemia, can promote modest weight loss, and has good antihyper-glycemic efficacy at doses of 2,000 to 2,500 mg/day.Its effects are quite durable compared to sulfonylureas (SFUs), and it also has robust cardiovascular safety relative to SFUs (83-85). Owing to risk of lactic acido-。

2016 AACEACE 共识声明:糖尿病综合管理方案2016 年1 月,美国临床内分泌医师协会(AACE )和美国内分泌学会(ACE )共同更新了2 型糖尿病综合管理方案,指南内容涵盖生活方式干预、总体指导原则及相关药物组合。

指南发表于《Endocrine Practice 》。

指南要点概括如下。

基本原则1、生活方式治疗,包括药物辅助减重,是治疗 2 型糖尿病的关键。

2、应根据个体化制定A1C 目标。

3、血糖控制目标包括空腹血糖和餐后血糖。

4、根据患者个体特征、医疗费用对患者的影响、处方限制以及患者的个人喜好选择个体化治疗方式。

5、优先选择低血糖风险最小化的治疗方案。

6、优先选择体重增加风险最小化的治疗方案。

7、初始药物费用只是总医疗费用的一部分,后者还包括必要的监测费用、控制低血糖风险以及体重增加风险的费用、保证治疗安全性的费用等。

8、本方案的分层治疗基于初始A1C 水平。

9、联合用药治疗时应选择具有互补作用机制的药物。

10、综合治疗包括血脂、血压以及相关并发症的治疗。

11、治疗期间需要经常评估治疗效果(如每 3 个月一次)直至病情稳定,之后可降低评估频率。

12、治疗方案应尽可能简单以提高依从性。

13、本方案包含的糖尿病治疗药物均经过FDA 批准。

血糖控制根据个体化制定A1C目标• A1C三6.5% :针对无严重疾病并存及低血糖发生风险较低的患者。

• A1C > 6.5% :针对合并严重疾病以及有低血糖发生风险的患者。

生活方式治疗生活方式治疗从营养咨询和教育开始。

所有患者应保持以植物类为基础的饮食习惯;增加多不饱和脂肪酸和单不饱和脂肪酸的摄入,避免反式脂肪酸和饱和脂肪酸摄入,以努力达到并保持最佳体重。

超重/肥胖患者应限制热量摄入以达到减重5%-10% 的目标。

结构化咨询(每周或每月一次的特定减肥课程)以及替代饮食已被证明比标准的办公室咨询更有效。

体力活动是减肥和维持计划的主要组成部分。

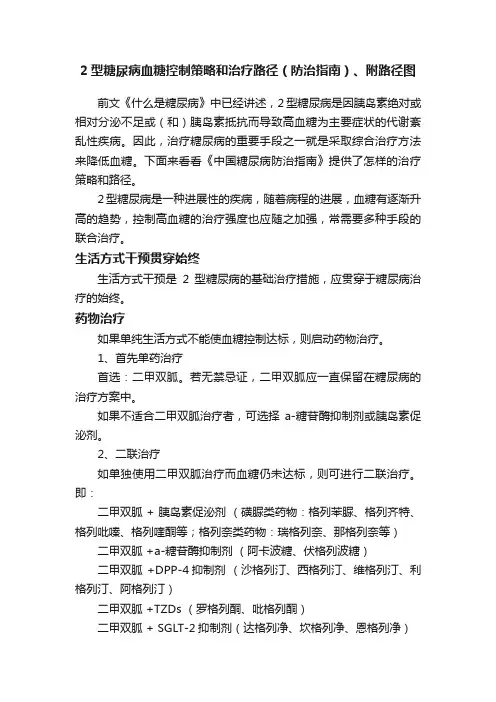

2型糖尿病血糖控制策略和治疗路径(防治指南)、附路径图前文《什么是糖尿病》中已经讲述,2型糖尿病是因胰岛素绝对或相对分泌不足或(和)胰岛素抵抗而导致高血糖为主要症状的代谢紊乱性疾病。

因此,治疗糖尿病的重要手段之一就是采取综合治疗方法来降低血糖。

下面来看看《中国糖尿病防治指南》提供了怎样的治疗策略和路径。

2型糖尿病是一种进展性的疾病,随着病程的进展,血糖有逐渐升高的趋势,控制高血糖的治疗强度也应随之加强,常需要多种手段的联合治疗。

生活方式干预贯穿始终生活方式干预是2型糖尿病的基础治疗措施,应贯穿于糖尿病治疗的始终。

药物治疗如果单纯生活方式不能使血糖控制达标,则启动药物治疗。

1、首先单药治疗首选:二甲双胍。

若无禁忌证,二甲双胍应一直保留在糖尿病的治疗方案中。

如果不适合二甲双胍治疗者,可选择a-糖苷酶抑制剂或胰岛素促泌剂。

2、二联治疗如单独使用二甲双胍治疗而血糖仍未达标,则可进行二联治疗。

即:二甲双胍 + 胰岛素促泌剂(磺脲类药物:格列苯脲、格列齐特、格列吡嗪、格列喹酮等;格列奈类药物:瑞格列奈、那格列奈等)二甲双胍 +a-糖苷酶抑制剂(阿卡波糖、伏格列波糖)二甲双胍 +DPP-4抑制剂(沙格列汀、西格列汀、维格列汀、利格列汀、阿格列汀)二甲双胍 +TZDs (罗格列酮、吡格列酮)二甲双胍 + SGLT-2抑制剂(达格列净、坎格列净、恩格列净)二甲双胍 + 胰岛素二甲双胍 +GLP-l受体激动剂(艾塞那肽、贝那鲁肽、利拉鲁肽、度拉糖肽)3、三联治疗上述不同机制的降糖药物可以三种药物联合使用。

二甲双胍 + 其他两种4、多次胰岛素治疗如三联治疗控制血糖仍不达标,则应将治疗方案调整为多次胰岛素治疗(基础胰岛素加餐时胰岛素或每日多次预混胰岛素)。

特别提示:采用多次胰岛素治疗时应停用胰岛素促分泌剂。

2 型糖尿病高血糖治疗路径图糖尿病治疗常用药物介绍目前糖尿病治疗药物包括口服药和注射制剂两大类。

口服降糖药主要有促胰岛素分泌剂、非促胰岛素分泌剂、二肽基肽酶-4抑制剂(DPP-4抑制剂)和钠-葡萄糖共转运蛋白2抑制剂(SGLT-2抑制剂)。

-905.[12]Qi DJ ,Zhang LH ,Wang S ,et al.Evaluation of case -centered ,problem -based and community -oriented curriculum teaching model in general practice [J ].Chinese General Practice ,2012,15(2):418-420,424.(in Chinese )齐殿君,张联红,王爽,等.“以病例为中心、问题为基础、社区为导向”全科医学教学模式的效果评价研究[J ].中国全科医学,2012,15(2):418-420,424.[13]Li XY ,Tian ZB ,Wang XM ,et al.Undergraduates assumingresponsibility in clinical placement [J ].China Higher Medical Education ,2015,29(2):16-17.(in Chinese )李晓宇,田字彬,王雪梅,等.“责任制实习法”对本科临床实习教学效果探讨[J ].中国高等医学教育,2015,29(2):16-17.[14]Zhu WH ,Fang LZ ,Dai HL ,et al.Utility of tutorial system instandardized training management of general practitioners [J ].Chinese Journal of General Practice ,2014,12(3):333-335.(in Chinese )朱文华,方力争,戴红蕾,等.导师跟踪模式在全科住院医师规范化培训管理中的运用[J ].中华全科医学,2014,12(3):333-335.[15]姚永祥,王宏智,刘建迪.实行实习医生导师制提高临床实习教学效果[J ].现代医药卫生,2003,19(12):1650.[16]高力军,吴群红,郝艳华,等.发达国家全科医生培养模式对我国的启示[J ].继续教育,2014,28(1):58-59.[17]吕慈仙,李学兰.国外全科医生培养方式及其对我国高等院校的启示[J ].中国农村卫生事业管理,2012,32(8):779-782.[18]Yu XY.Exploration on the curriculum system reform of generalmedical clinical teaching [J ].The Science Education Article Cultures ,2015,12(8):79-80.(in Chinese )郁晓燕.全科医学临床教学课程体系的改革探索[J ].科教文汇,2015,12(8):79-80.[19]全国教育科学规划领导小组办公室.“我国全科医生培养模式创新研究”成果报告[J ].大学:学术版,2012,7(4):84-89.[20]He KR.Discussing the medical humanities education in generalpractitioners system [J ].Chinese Health Service Management ,2014,31(4):291-293.(in Chinese )何昆蓉.论全科医生制度下的医学人文教育[J ].中国卫生事业管理,2014,31(4):291-293.(收稿日期:2015-12-10;修回日期:2016-03-15)(本文编辑:闫行敏)·全科医生知识窗·美国糖尿病学会(ADA )2016指南:糖尿病血糖控制诊疗标准近日美国糖尿病学会(ADA )更新了2016年糖尿病诊疗标准,于2015-12-22在线发表于Diabetes Care 2016年1月份增刊。

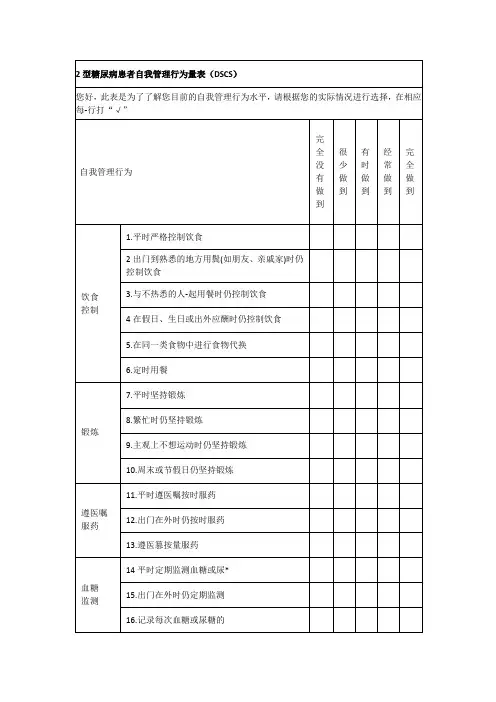

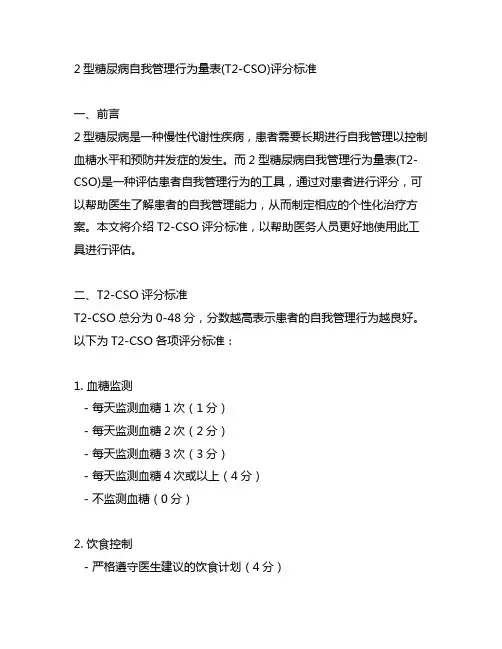

2型糖尿病自我管理行为量表(T2-CSO)评分标准一、前言2型糖尿病是一种慢性代谢性疾病,患者需要长期进行自我管理以控制血糖水平和预防并发症的发生。

而2型糖尿病自我管理行为量表(T2-CSO)是一种评估患者自我管理行为的工具,通过对患者进行评分,可以帮助医生了解患者的自我管理能力,从而制定相应的个性化治疗方案。

本文将介绍T2-CSO评分标准,以帮助医务人员更好地使用此工具进行评估。

二、T2-CSO评分标准T2-CSO总分为0-48分,分数越高表示患者的自我管理行为越良好。

以下为T2-CSO各项评分标准:1. 血糖监测- 每天监测血糖1次(1分)- 每天监测血糖2次(2分)- 每天监测血糖3次(3分)- 每天监测血糖4次或以上(4分)- 不监测血糖(0分)2. 饮食控制- 严格遵守医生建议的饮食计划(4分)- 基本按照医生建议饮食,但偶尔有不合理的摄入(3分)- 不太遵守医生建议饮食,有时食用高糖高脂食物(2分)- 完全不遵守医生建议饮食,食用大量高糖高脂食物(1分)- 不清楚医生的饮食建议(0分)3. 运动- 每天坚持进行适当的运动(4分)- 大部分时间会参加一些运动活动(3分)- 偶尔参加一些运动活动(2分)- 很少参加运动活动(1分)- 完全不参加任何运动活动(0分)4. 用药- 严格按医生开具的药物处方使用药物(4分)- 基本按医生开具的药物处方使用药物,但偶尔会漏服或过量服药(3分)- 不太按医生开具的药物处方使用药物,漏服或过量服药较多(2分) - 完全不按医生开具的药物处方使用药物(1分)- 不清楚医生的药物处方(0分)5. 医疗指导- 定期接受医生的随访和沟通,积极配合医生的治疗方案(4分)- 大部分时间能够接受医生的随访和沟通,配合医生治疗方案(3分)- 偶尔接受医生的随访和沟通,配合医生治疗方案(2分)- 很少接受医生的随访和沟通,不太配合医生治疗方案(1分)- 完全不接受医生的随访和沟通,不配合医生治疗方案(0分)6. 心理调适- 良好的心态,能够积极面对疾病,主动寻求心理支持(4分)- 一般的心态,偶尔有消极情绪,但能够通过自我调整缓解(3分) - 较差的心态,经常有消极情绪,但能够通过他人帮助缓解(2分) - 非常消极的心态,无法通过自我或他人帮助缓解(1分)- 完全不关注心理调适,心态极其消极(0分)三、T2-CSO评分结果解读根据T2-CSO评分,可以将患者的自我管理行为划分为良好、一般、不良三个等级:- 良好:34-48分表明患者在血糖监测、饮食控制、运动、用药、医疗指导和心理调适等方面表现良好,对疾病有较好的认识和应对能力。

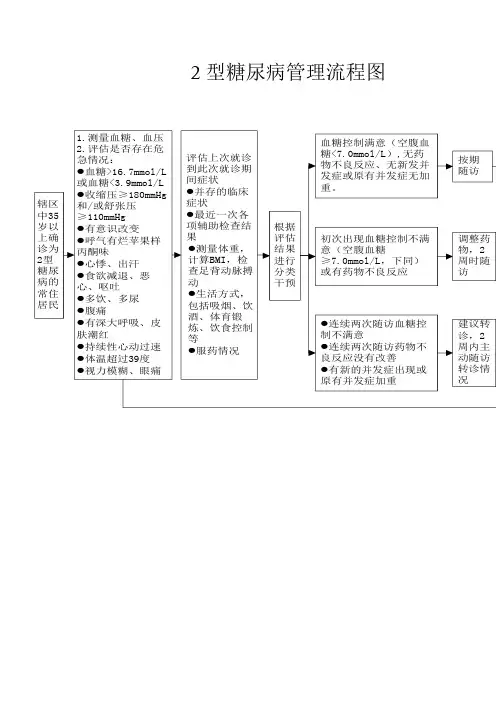

带您看懂那些糖尿病管理流程图(上)作者:徐赫男来源:《糖尿病天地》2017年第03期在推行分级诊疗后,小编走访了北京的几家社区医院,看到诊室墙上都贴着《中国2型糖尿病防治指南(2013版)》里面的高血糖治疗路径图。

从这几年国内外发布的糖尿病相关指南或专家共识中会发现一个特点,就是都喜欢给出路径图或是流程图。

这些图简单直观,非常方便临床医生使用,对患者也有很大帮助。

前不久在杂志公众号上登出国外2型糖尿病管理流程图的中文译版时,有读者反馈说东西是好东西,可只是给专业人员看的,我们患者看不懂。

下面就让我们一起去弄懂这些流程图。

国内外专业组织发布的指南或共识通常都是可以免费查阅的,进入互联网时代,大家可以很容易地获取。

大家可能会发现,近几年的指南或共识里喜欢给出各种流程图,如果能够看懂,对糖尿病管理会有很大帮助。

本期我们首先介绍各大组织发布的最新版的指南或共识中有关高血糖管理的流程图。

尽管近几年一直在强调糖尿病综合管理,但血糖管理是首先需要关注的问题,也是大多数糖友最关心的问题。

下面让我们去看看各大专业组织最新版的高血糖管理流程图,当然这其中有些已经是几年前发布的内容了,总体来说,对于高血糖的管理,总体思路并没有太大变化,国外组织只是增添了一些新的药物,估计随着钠一葡萄糖共转运蛋白2(SGLT-2)抑制剂进入我国,中华医学会糖尿病学分会(CDS)很快会对该流程图进行更新。

CDs-2型糖尿病高血糖治疗路径CDS发布的《中国2型糖尿病防治指南(2013年版)》中对2010年版指南的高血糖治疗路径做了一些修改(见图1),主要是将二线药物选择中的DPP-4抑制剂和噻唑烷二酮类由备选路径升为主要路径,将三线药物选择中的GLP-1受体激动剂由备选路径升为主要路径。

CDS 确定主要路径是基于费用、疗效和安全性等方面的临床证据以及国情等因素。

2013年版做出这种“升级”主要原因可能包括以下几方面:(1)近几年DPP-4抑制剂和GLP-1受体激动剂的国内外研究证据不断增多,证实了其在降糖等多方面的治疗益处,同时这些新药在国内临床应用越来越多,也积累了更多的使用经验,同时部分药物被纳入医保,这就降低了患者的药费负担;(2)前些年的罗格列酮风波使得临床上对噻唑烷二酮类药物的使用更加谨慎,而随着研究数据的增加,此类药物的治疗获益得到进一步的证实,同时随着专利保护过期,仿制药可以大大降低治疗费用,所以只要把握好适应证和禁忌证并做好监测,这类药物可以被作为主要选择。

美国糖尿病协会制定(海南医学院附属医院内分泌科王新军王转锁译)美国糖尿病协会(ADA)制定了2016年糖尿病诊疗标准,诊疗标准更加强调个性化治疗,海南医学院附属医院内分泌科王新军、王转锁对相关内容进行了翻译,详情如下:改进治疗的策略●应该运用结合病人意愿、评估文化和计算力、处理文化障碍的以病人为中心的沟通方式。

B●治疗决策应及时并且应以循证指南为基础,并根据患者意愿、预后和伴发病调整。

B●治疗应与慢病管理模式的内容一致,以确保有准备的积极的医疗小组和受教育的主动的患者之间的有效互动。

A●如果可能,治疗体系应支持团队管理、社区参与、患者登记和决策支持工具,以满足患者需求。

B食品不安全供应商应评估食品高血糖和低血糖的风险并提出相应的解决方案。

A供应商应该认识到无家可归、识字能力差和计算能力低的糖尿病患者经常发生不安全问题,并为糖尿病患者提供合适的资源。

A认知功能障碍●不建议对认知功能较差的2型糖尿病患者进行强化血糖控制。

B●认知能力较差或有严重低血糖的患者,血糖治疗应该个体化,避免严重低血糖。

C●在心血管高危的糖尿病患者,他汀治疗的心血管获益超过认知功能障碍的风险。

A●如果处方第二代抗精神病药物,应该严密监测体重、血糖控制和胆固醇水平的变化,并应重新评估治疗方案。

CHIV糖尿病患者的诊治HIV患者在开始抗病毒治疗之前和治疗开始后3个月或治疗方案变化时应该用空腹血糖水平筛查糖尿病和糖尿病前期。

如果初始筛查结果正常,建议每年复查空腹血糖。

如果筛查结果是糖尿病前期,每3~6个月复查血糖水平,监测是否进展为糖尿病。

E糖尿病风险增加(糖尿病前期)的分类●超重或肥胖(BMI≥25kg/m2或亚裔美国人≥23kg/m2)且有一个或以上其他糖尿病危险因素的无症状的成人,不论年龄,进行检查以评估未来糖尿病的风险。

B●对所有病人,应从45岁开始应进行检查。

B●如果检查结果正常,至少每3年复查是合理的。

C●使用空腹血糖、75g OGTT 2h血糖或A1C筛查糖尿病前期都是合适的。