Seroprevalence of HIV, HSV-2, and

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:85.08 KB

- 文档页数:7

HSV-2治疗可降低HIV-1病毒载量

曹振环(编译)

【期刊名称】《传染病网络动态》

【年(卷),期】2007(000)004

【摘要】据Medscape.com2月21日报道(原载N Engl J Med2007;356:790—799,854—856),研究发现,双重感染HIV—1和疱疹病毒-2(HSV-2)的女性患者,在应用伐昔洛韦抗HSV治疗后可降低血液和生殖器分泌物中HIV-1的RNA水平。

【总页数】2页(P9-10)

【作者】曹振环(编译)

【作者单位】无

【正文语种】中文

【中图分类】R512.91

【相关文献】

1.某地区2009~2014年抗病毒治疗AIDS患者HIV-1病毒载量分析 [J], 杨恒根;吴文娅;苏文锦;钟敏;杨树蘅;母继林

2.康艾对高活性抗逆转录病毒疗法治疗HIV-1患者病毒载量和CD4+T细胞的影响[J], 杨崎恩;蒋亦明;孙彤;陈仁芳;陆宇红

3.生殖器疱疹患者皮损HSV-2病毒载量与外周血细胞免疫功能的关系 [J], 林路洋;李常兴;武明昌;李嘉彦;颜景兰;梁艳华;何玉清;张锡宝

4.Xpert HIV-1病毒载量检测系统用于HIV-1病毒载量检测的临床价值 [J], 杨坤;

陈耀凯; 王静; 李同心; 李俊刚; 李梅; 罗福龙; 邓仁麑; 刘敏; 聂晓平

5.阿昔洛韦:不能降低HIV-1和HSV-2共感染者HV的传播风险 [J], Celum C Wald A Lingappa JR

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

欧洲HIV感染女性HSV-1和HSV-2抗体阳性率及危险因素

研究

佚名

【期刊名称】《国际皮肤性病学杂志》

【年(卷),期】2002(028)004

【摘要】无

【总页数】1页(P268)

【正文语种】中文

【中图分类】R75

【相关文献】

1.HIV及HSV感染妇女子宫阴道分泌物HIV-1及HSV-1/HSV-2的实时定量PCR分析 [J],

2.合成毒品使用人群中HIV感染状态及危险因素研究进展 [J], 王汝佳;鲍彦平

3.男男性行为人群HIV感染危险因素研究进展 [J], 徐洪吕;陆林;贾曼红;章任重

4.HIV感染者/AIDS患者自杀意念危险因素研究进展 [J], 杨梓杰;张燕;欧利民;李丽萍;赵锦

5.广州地区女性不同人群HSV-2感染调查及危险因素分析 [J], 汤少开;叶兴东;黄雪梅;曹文苓;邓蕙妍;黎小东;谭学英;丘小珊

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

综合医院皮肤性病门诊梅毒 HSV-2及HIV感染流行状况分析黎奇;吴砚;李玉叶;曹应葵【期刊名称】《皮肤病与性病》【年(卷),期】2014(000)003【摘要】Objective To investigate the infection status and related risk factors of Syphilis, HSV-2 and HIV in the dermatology and venerology outpatients in a comprehensive hospital, which will provide basis for prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Methods The patients in dermatology and venerology outpatients from september 2011 to september 2011, were tested with syphilis, HSV-2, HIV as well as given questionnaire. Results Syphilis, HSV-2 and HIV positive rates were 19. 0%, 31. 0% and 3. 7% respectively. The positive rates of syph-ilis and HSV-2 in female were significantly higher than in male. Syphilis, HSV-2 and HIV positive rates were ap-parently higher in attendants with non-use condoms, multiple sexual partners or low educational background. Con-clusion The promotion and popularization of knowledge of preventing Venereal diseases should be strengthened. Safe sex should be promoted, especially in female and low education background crowd.%目的:分析综合医院皮肤性病门诊就诊人群梅毒、HSV-2及HIV感染情况及相关高危因素,为性病综合防治提供依据。

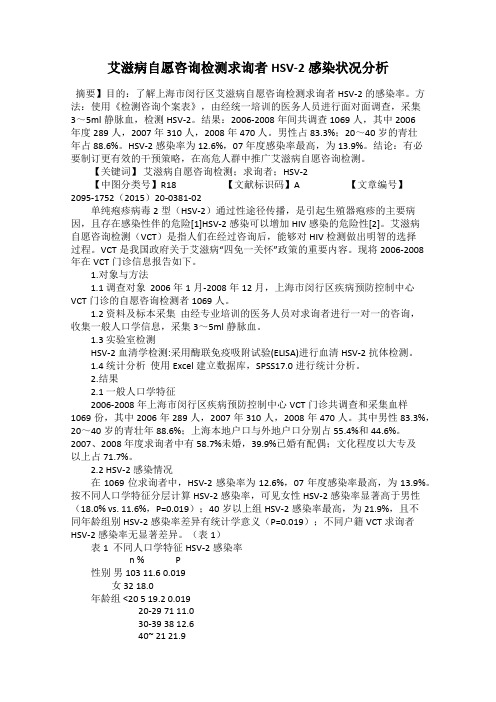

艾滋病自愿咨询检测求询者HSV-2感染状况分析摘要】目的:了解上海市闵行区艾滋病自愿咨询检测求询者HSV-2的感染率。

方法:使用《检测咨询个案表》,由经统一培训的医务人员进行面对面调查,采集3~5ml静脉血,检测HSV-2。

结果:2006-2008年间共调查1069人,其中2006年度289人,2007年310人,2008年470人。

男性占83.3%;20~40岁的青壮年占88.6%。

HSV-2感染率为12.6%,07年度感染率最高,为13.9%。

结论:有必要制订更有效的干预策略,在高危人群中推广艾滋病自愿咨询检测。

【关键词】艾滋病自愿咨询检测;求询者;HSV-2【中图分类号】R18 【文献标识码】A 【文章编号】2095-1752(2015)20-0381-02单纯疱疹病毒2型(HSV-2)通过性途径传播,是引起生殖器疱疹的主要病因,且存在感染性伴的危险[1]HSV-2感染可以增加HIV感染的危险性[2]。

艾滋病自愿咨询检测(VCT)是指人们在经过咨询后,能够对HIV检测做出明智的选择过程。

VCT是我国政府关于艾滋病“四免一关怀”政策的重要内容。

现将2006-2008年在VCT门诊信息报告如下。

1.对象与方法1.1 调查对象 2006年1月-2008年12月,上海市闵行区疾病预防控制中心VCT门诊的自愿咨询检测者1069人。

1.2 资料及标本采集由经专业培训的医务人员对求询者进行一对一的咨询,收集一般人口学信息,采集3~5ml静脉血。

1.3 实验室检测HSV-2血清学检测:采用酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)进行血清HSV-2抗体检测。

1.4 统计分析使用Excel建立数据库,SPSS17.0进行统计分析。

2.结果2.1 一般人口学特征2006-2008年上海市闵行区疾病预防控制中心VCT门诊共调查和采集血样1069份,其中2006年289人,2007年310人,2008年470人。

其中男性83.3%,20~40岁的青壮年88.6%;上海本地户口与外地户口分别占55.4%和44.6%。

单纯疱疹病毒II型LAT基因开放读码框1抗细胞凋亡作用的研究单纯疱疹病毒Ⅱ型(Herpes Simplex Virus Ⅱ,HSV-2)具有易感染,容易传播,难治愈的特点。

它主要引起生殖器疱疹(genital herpes,GH)。

初次感染HSV-2后,病毒会终身潜伏在人体的骶尾神经节中。

当受到体内外各种非特异性刺激时,病毒会被激活,造成复发感染,并出现相应的临床症状。

目前疱疹病毒潜伏及再激活的机制一直未明,是临床上根治生殖器疱疹的难点所在。

潜伏相关转录体是(Latency associated transcript,LAT)HSV-2在潜伏感染期间唯一大量表达的基因组转录产物。

国外大量的研究表明,潜伏相关转录体在单纯疱疹病毒潜伏及再激活过程中起着至关重要的作用。

目前有关LAT的作用假说很多,但具体是哪一种作用机制尚不明确。

HSV-2起主要作用的LAT包含3个开放读码框(Open Reading Frame,ORF)。

有研究表明单纯疱疹病毒LAT可以通过读码框编码蛋白的抗凋亡作用抑制宿主细胞的凋亡,维持病毒的潜伏感染状态。

为此,本研究以HSV-2333基因组为模板PCR扩增HSV-2LAT ORF1,构建重组真核表达载体pEGFP-ORF1。

借助于xfect转染试剂盒,转染重组子,研究其在Vero细胞中的表达及其抗凋亡作用。

首先根据gene bank中的LAT ORFs序列设计引物,以HSV-2333基因组为模板PCR扩增HSV-2LAT ORF1片段。

PCR产物纯化后同pEGFP-C2经EcoRI、KpnI 双酶切后,用T4-ligase连接,转化进E.coli Top10感受态细胞,kan+抗性筛选阳性菌落,通过菌落PCR,双酶切和测序对所筛选的重组质粒进行鉴定。

重组质粒转染入Vero细胞,24h后在荧光显微镜下观察HSV-2潜伏相关转录体LAT开放读码框ORF1融合绿色荧光蛋白的表达情况。

hsv2 igg临界HSV-2 IgG临界HSV-2 IgG(即Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Immunoglobulin G)是指人体对于单纯疱疹病毒2型(HSV-2)抗体的一种特定免疫球蛋白G。

HSV-2是一种性传播的病毒,感染后可引起生殖器疱疹,对患者的生活和心理造成很大困扰。

HSV-2 IgG临界值是指血液中HSV-2 IgG抗体的浓度达到一定水平,从而可以判断患者是否感染了HSV-2病毒。

HSV-2感染是一种常见的性传播疾病,全球范围内有很高的感染率。

根据世界卫生组织的数据,全球约有4.4亿人感染了HSV-2病毒。

HSV-2感染主要通过性接触传播,尤其是性交。

患者在病毒感染后,常常出现生殖器疱疹的症状,如发痒、疼痛、溃疡等。

HSV-2感染还会增加人们患其他性传播疾病(如艾滋病)的风险。

HSV-2 IgG临界值的确定对于HSV-2感染的诊断和治疗非常重要。

HSV-2 IgG抗体的浓度可以通过血液检测来确定,一般采用酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)或荧光免疫法(IFA)等方法。

在检测结果中,通常会给出一个临界值。

如果患者的HSV-2 IgG抗体浓度高于临界值,说明患者已经感染了HSV-2病毒。

反之,如果患者的HSV-2 IgG抗体浓度低于临界值,说明患者没有感染HSV-2病毒。

HSV-2 IgG临界值的确定是通过大量的临床实验和统计学分析得出的。

研究人员通过收集大量感染了HSV-2病毒的患者和未感染的健康人群的血液样本,进行HSV-2 IgG抗体浓度的检测。

通过对比两组人群的HSV-2 IgG抗体浓度,研究人员可以确定一个较为准确的临界值。

一般来说,HSV-2 IgG抗体浓度在1.1以上被认为是阳性,即患者已经感染了HSV-2病毒。

HSV-2 IgG临界值的确定对于患者的治疗和预防非常重要。

一旦患者的HSV-2 IgG抗体浓度高于临界值,医生会给予相应的治疗措施。

常见的治疗方法包括使用抗病毒药物,如阿昔洛韦(Acyclovir)和瓦拉西韦(Valacyclovir),以减少病毒的复制和传播。

男男性行为者与艾滋病传播的研究进展男男性行为者与艾滋病传播的研究进展摘要:对男男性行为者和艾滋病的定义,男男性行为人群与艾滋病传播有关的高危行为研究以及其他影响因素,在该人群中开展艾滋病防治工作进行了阐述。

关键字:男男性行为;艾滋病;高危行为;艾滋病防治自1989年我国发现首例艾滋病(AIDS)病人以来,该病的主要传播途径前后经历了不同的方式:由早期静脉注射吸毒传播为主,逐渐演变为吸毒与性传播并重,进而发展到目前的经性传播为主。

2011年我国估计现存的78万艾滋病病毒感染者和艾滋病病人中,经异性传播的占46.5%,男男同性传播占17.4%。

可见,男男性行为人群已经成为艾滋病危害的主要人群之一。

因此,了解该人群的高危行为特征及艾滋病传播的相关影响因素,以及针对MSM人群如何开展AIDS的防治工作意义重大。

查阅了近年来国内外关于男男性行为与艾滋病之间关系的文献资料,现综述如下。

1.基本概念1.1 对艾滋病的界定艾滋病(即获得性免疫缺陷综合症,acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, AIDS)是由艾滋病病毒(human immunodeficiency virus, HIV)侵入人体后,损伤全身免疫系统而使人体发生一系列不可治愈的感染和肿瘤,最后导致患者死亡的传染性疾病。

HIV主要存在于感染者的血液、精液、阴道分泌物、乳汁等体液中,因此艾滋病传播主要通过性接触传播、血液传播和母婴传播三种传播途径。

由于艾滋病无症状感染期较长,无有效疫苗且尚无根治药物,受累人群主要为最具生产力的中青年,因而对个人、家庭和社会造成的损坏巨大。

目前观察到的AIDS的危害主要表现在:严重缩短人均期望寿命,家庭崩溃并产生大量的艾滋病孤儿,推动社会经济发展的劳动力丧失,加重国家的财政负担,甚至会危机国家的兴衰存亡。

1.2对男男性行为者的界定男男性行为者(men who have sex with men,MSM)主要是一个行为学概念,是指与男性发生过性行为的男性,它分为男同性恋、男双性恋者、有同性性行为的异性恋者和男性变性欲者等四大类亚人群,其主体是男男同性恋(Gay)和男性双性恋者(Bi)[2]。

Seminar HIV infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment,and preventionGary Maartens, Connie Celum, Sharon R LewinHIV prevalence is increasing world wid e because people on antiretroviral therapy are living longer, although newinfections d ecreased from 3·3 million in 2002, to 2·3 million in 2012. Global AIDS-related d eaths peaked at2·3 million in 2005, and d ecreased to 1·6 million by 2012. An estimated 9·7 million people in low-income andmid d le-income countries had started antiretroviral therapy by 2012. New insights into the mechanisms of latentinfection and the importance of reservoirs of infection might eventually lead to a cure. The role of immune activationin the pathogenesis of non-AIDS clinical events (major causes of morbidity and mortality in people on antiretroviraltherapy) is receiving increased recognition. Breakthroughs in the prevention of HIV important to public healthinclude male medical circumcision, antiretrovirals to prevent mother-to-child transmission, antiretroviral therapy inpeople with HIV to prevent transmission, and antiretrovirals for pre-exposure prophylaxis. Research into otherprevention interventions, notably vaccines and vaginal microbicides, is in progress.EpidemiologyThe H IV epidemic arose after zoonotic infections with simian immunodeficiency viruses from African primates; bushmeat hunters were probably the fi rst group to be infected with H IV.1 H IV-1 was transmitted from apes and H IV-2 from sooty mangabey monkeys.1 Four groups of HIV-1 exist and represent three separate transmission events from chimpanzees (M, N, and O), and one from gorillas (P). Groups N, O, and P are restricted to west Africa. Group M, which is the cause of the global H IV pandemic, started about 100 years ago and consists of nine subtypes: A–D, F–H, J, and K. Subtype C predominates in Africa and India, and accounted for 48% of cases of HIV-1 in 2007 worldwide.2 Subtype B predominates in western Europe, the Americas, and Australia. Circulating recombinant subtypes are becoming more common.2 The marked genetic diversity of HIV-1 is a consequence of the error-prone function of reverse transcriptase, which results in a high mutation rate. HIV-2 is largely confi ned to west Africa and causes a similar illness to H IV-1, but immunodefi ciency progresses more slowly and HIV-2 is less transmissible.1In 2012 an estimated 35·3 million people were living with H IV.3 Sub-Saharan Africa, especially southern Africa, has the highest global burden of H IV (70·8%; fi gure 1). The global epidemiology of HIV infection has changed markedly as a result of the expanding access to antiretroviral therapy; by 2012, 9·7 million people in low-income and middle-income countries had started antiretroviral therapy.4 The global prevalence of HIV has increased from 31·0 million in 2002, to 35·3 million in 2012, because people on antiretroviral therapy are living longer,5 whereas global incidence has decreased from 3·3 million in 2002, to 2·3 million in 2012.3 The reduction in global HIV incidence is largely due to reductions in heterosexual transmission. Punitive attitudes towards people who inject drugs (especially in eastern Europe) restrict the implementation of opioid substitution treatment and needle and syringe programmes, which are effective prevention strategies that reduce H IVtransmission.6 In regions where the main route oftransmission is men who have sex with men (eg, westernand central Europe and the Americas), incidence is stabledespite high antiretroviral therapy coverage (eg, 75% inLatin America in 2012,3 and 80% in the UK in 2010).7 Thedrivers of the HIV epidemic in men who have sex withmen are complex, and include increasing risk behavioursince the introduction of eff ective antiretroviral therapy(a phenomenon termed therapeutic optimism8), hightransmission risk of receptive anal intercourse, sexualnetworks, and stigma restricting access to care.9The number of new infections in children in the21 priority African countries in the UN Programme onH IV/AIDS (UNAIDS) global plan10 decreased by 38%between 2009 and 2012, because of increased access toantiretrovirals to prevent mother-to-child transmission.However, access to antiretroviral therapy is much lowerin children than adults.3H IV is a major contributor to the global burden ofdisease. In 2010, HIV was the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years worldwide for people aged 30–44 years,and the fi fth leading cause for all ages.11 Global AIDS-related deaths peaked at 2·3 million in 2005, anddecreased to 1·6 million by 2012.3 About 50% of all deathsPublished OnlineJune 5, 2014/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60164-1Division of ClinicalPharmacology, Department ofMedicine, University of CapeTown, Cape Town, South Africa(Prof G Maartens MMed);Departments of Global Health,Medicine and Epidemiology,University of Washington,Seattle, WA, USA(Prof C Celum MD); Departmentof Infectious Diseases, MonashUniversity, Melbourne,Australia (Prof S R Lewin PhD);Infectious Diseases Unit,Alfred Hospital, Melbourne,Australia (Prof S R Lewin); andCentre for Biomedical Research,Burnet Institute, Melbourne,Australia (Prof S R Lewin)Correspondence to:Prof Gary Maartens, Division ofClinical Pharmacology,Department of Medicine,University of Cape Town HealthSciences Faulty, Cape Town 7925,South Africagary.maartens@uct.ac.zaSearch strategy and selection criteriaWe searched PubMed for publications in English from Jan 1,2008, to Oct 31, 2013,but did not exclude commonlyreferenced and highly regarded older publications. We usedthe search terms “HIV” or “AIDS” in combinations with“epidemiology”, “prevention”, “pathogenesis”, “antiretroviraltherapy”, “resistance”, and “latency”. We also searched thereference lists of articles identifi ed by this search strategy andselected those we judged relevant. Review articles are cited toprovide readers with more details and more references thanthis Seminar has room for. Our reference list was modifi ed onthe basis of comments from peer reviewers.Seminarin people on antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries are not due to AIDS.12 In one study, major causes of non-AIDS-related deaths were non-AIDS-defining cancers (23·5%), cardiovascular disease (15·7%), and liver disease (14·1%).12 People with H IV have a 50% increased risk of myocardial infarctions than do people without HIV after adjustment for vascular risk factors.13 Liver disease is common, mainly because of co-infection with hepatitis B and C, which share similar routes of transmission with HIV.14Tuberculosis continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in low-income and middle -income countries, especially in Africa.15 Findings of a study16 done in South Africa in the pre-antiretroviral therapy era showed that tuberculosis doubled within a year after HIV infection, thereafter incidence increased as immunity decreased, and reached a very high incidence of 25·7 per 100 person-years in patients with CD4 T-cell counts lower than 50 cells per μL.17 Worldwide, H IV-related tuberculosis mortality is decreasing,15 but many people with H IV in Africa die of undiagnosed tuberculosis.18HIV-1 transmissionThe most important factor that increases the risk of sexual transmission of HIV-1 is the number of copies per mL of plasma HIV-1 RNA (viral load), with a 2·4 times increased risk of sexual transmission for every 1 log10increase.19 Acute HIV infection, which causes very high plasma viral loads in the fi rst few months, is an important driver of H IV epidemics.20 A reduction in plasma viral load of 0·7 log10is estimated to reduce H IV-1 transmission by 50%.21 Seminal and endocervical viral load independently predict risk of HIV-1 sexual transmission, after adjustment for plasma viral load.22 Other factors associated with increased risk of sexual transmission of H IV include sexually transmitted infections (notably genital ulcers of any cause,23 herpes simplex type-2 infection,24 and bacterial vaginosis25), pregnancy,26 and receptive anal intercourse.27 Male circumcision is associated with a reduced risk of sexual transmission of HIV.28Findings of some observational studies showed an increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition in women who used long-acting injectable progestogens for contraception, but not with combined oral contraceptives.29 A health priority in eastern and southern Africa, where the incidence of HIV-1 in young women is very high,30 is to fi nd out whether long-acting injectable progestogens (the commonest form of contraception used in this region) increase HIV-1 transmission.Behavioural factors that increase H IV-1 sexual transmission include many sexual partners,31 and concurrent partnerships.32 Findings of a study33 of African heterosexual serodiscordant couples showed that self-reported condom use reduced the per-coital act risk of H IV-1 transmission by 78%.33 Sex inequality is an important driver of the HIV epidemic, especially in sub-Saharan Africa where women account for 57% of people living with H IV.3 Injection and non-injection drug use, including alcohol, are associated with increased sexual risk behaviour, whereas injection drug use causes H IV transmission by shared needles.34 Women who reported intimate partner violence had an increased incidence of HIV infection in a South African study.35 UNAIDS have identified stigma against H IV, and discrimination and punitive laws against high-risk groups (eg, men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, and commercial sex workers) as barriers for people to undergo H IV testing, access care, and access prevention measures.3 PathogenesisHIV life cycle and host immune responsesFigure 2 shows the virus life cycle. The main target of H IV is activated CD4 T lymphocytes; entry is via interactions with CD4 and the chemokine coreceptors, CCR5 or CXCR4. Other cells bearing CD4 and chemokineFigure 1: Estimated number of people living with HIV in 2012 and trends in the incidence of new infections from 2001 to 2012 by global region Data from UNAIDS 2013 report.3Seminarreceptors are also infected, including resting CD4 T cells, monocytes and macrophages, and dendritic cells. CD4-independent HIV infection of cells can happen, notably in astrocytes37 and renal epithelial cells,38 and subsequent H IV gene expression has an important role in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (related to astrocytes) and nephropathy (related to epithelial cells). A range of host proteins interact with HIV proteins or HIV DNA to either restrict or promote virus replication in specifi c cell types (table 1). Transmission of H IV across mucosal membranes is usually established by one founder virus, which has unique phenotypic properties including usage of CCR5 rather than CXR4 for entry,46 enhanced interaction with dendritic cells, and resistance to interferon-α.47 Transmission of the founder virus is followed by a rapid increase in HIV replication and then a striking induction of infl ammatory cytokines and chemokines, which is in stark contrast to the minimum initial response to other chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B or hepatitis C.48 Viral load then decreases to a so-called setpoint, the level of which is established largely by innate and adaptive immune responses (fi gure 3). HIV-specifi c CD8 killing of productively infected cells mediated by T cells happens soon after infection, and the potent adaptive immune response to HIV selects for the emergence of mutations in key epitopes, often leading to immune escape.49 In some H LA types, such as individuals with HLA-B27 allele infected with clade B, an eff ective immune response can arise, characterised by H IV-specifi c T cells with high avidity, polyfunctionality, and capacity to proliferate50 against both the immunodominant and escaped peptides.51 However, in nearly all individuals, progressive exhaustion of HIV-specifi c T cells happens, characterised by high expression of programmed death 1 (PD-1) on both total and HIV-specifi c T cells and a loss of eff ector function.52Neutralising antibodies arise roughly 3 months after transmission and select for viral escape mutants.53 Broadly neutralising antibodies, which can neutralise many H IV-1 subtypes, are produced by about 20% of patients.54 These antibodies are characterised by a high frequency of somatic mutations that often take years to develop.55 Broadly neutralising antibodies do not usually provide benefi t to the patient because of the development of viral escape mutants.56 The production of broadly neutralising antibodies by use of new immunogen design strategies is a major focus of vaccine research.57 The innate immune response to H IV is largely mediated by natural killer cells, and is also crucial for virus control. Viral escape mutants also emerge, and restrict the antiviral eff ects of natural killer cells.58Figure 2: HIV life cycle showing the sites of action of different classes of antiretroviral drugs Adapted from Walker and colleagues,36 by permission of Elsevier.SeminarImmune dysfunctionThe hallmark of H IV infection is the progressive depletion of CD4 T cells because of reduced production and increased destruction. CD4 T cells are eliminated by direct infection,59 and bystander effects of syncitia formation, immune activation, proliferation, and senescence. In early infection, a transient reduction in circulating CD4 T cells is followed by recovery to near normal concentrations, which then slowly decrease by about 50–100 cells per μL (fi gure 3).The most important effect on T-cell homoeostasis happens very early in the gastrointestinal tract, which has a massive depletion of activated CD4 T cells with minimum recovery after antiretroviral therapy.60 In addition to loss of total CD4 T cells, profound changes in T-cell subsets happen, including preferential loss of T-helper-17 cells,61 and mucosal-associated invariant T cells, which are crucial for defence against bacteria.62 The profound depletion of lymphoid cells in the gastrointestinal tract, together with enterocyte apoptosis, and enhanced gastrointestinal tract permeability, leads to increased plasma concentration of microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides.63 Finally, destruction of the fibroblastic reticular cell network, collagen deposition, and restricted access to the T-cell survival factor interleukin 7 in the lymphoid tissue further contribute to depletion of both CD4-naive and CD8-naive T cells.64Immune activationHIV infection is also characterised by a marked increase in immune activation, which includes both the adaptive and innate immune systems, and abnormalities in coagulation.65 The drivers for immune activation include the direct effects of H IV as a ligand for the Toll-like receptor (TLR7 and TLR 8) expressed on plasmacytoid dendritic cells, leading to production of interferon-α;66 microbial translocation, with lipopolysaccharide as a potent activator or TLR4 leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 6 and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα);63 co-infection with viruses such as cyto m egalovirus that induce profound expansion of activated cytomegalovirus-specifi c T cells;67and a reduced ratio of T-helper-17 and regulatory T cells, especially in the gastrointestinal tract.61Evidence of residual inflammation or increased immune activation exists, even in patients with H IV with adequate CD4 T-cell restoration on antiretroviral therapy (fi gure 3). Markers of residual infl ammation in patients with H IV on antiretroviral therapy have been significantly associated with mortality,68 cardiovascular disease,69 cancer,70 neurological disease,71 and liver disease.72 Intensification of antiretroviral therapy in participants with virological suppression with the addition of the integrase inhibitor raltegravir reduced T-cell activation in about a third of participants.73 These data suggest that low-level H IV replication might contribute to persistent infl ammation. Treatment of co-infections, such as cytomegalovirus and hepatitis C, reduces T-cell activation too.74,75Although many studies have identifi ed associations between different biomarkers of infl ammation and adverse clinical events, causation in studies in people has been difficult to establish. So far, strategies aimed to reduce residual infl ammation in patients with HIV have consisted of small observational studies with surrogate endpoints.76 Several drugs that are available for other indications (eg, statins, aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and hydroxychloroquine) have the potential to reduce H IV-associated infl am m ation.76 Randomised controlled studies are needed to establish whether targeting of inflammation in people with virological suppression on antiretroviral therapy will have a signifi cant clinical eff ect.Antiretroviral therapyCombination antiretroviral therapy regimens that were able to suppress viral replication were developed in the late 1990s and transformed H IV from a progressive illness with a fatal outcome into a chronic manageable disease. More than 25 licensed drugs that block H IV replication at many steps in the virus lifecycle are available (figure 2). Recommended antiretroviral therapy regimens are less toxic, more eff ective, have a lower pill burden, and are dosed less frequently than the initial protease inhibitor-based regimens. Standard anti r etroviral therapy regimens combine two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (emtricitabine or lamivudine together with one of abacavir, tenofovir, or zidovudine) with a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, protease inhibitor, or integrase inhibitor. Several effective nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-sparing regimens can be used if intolerance or resistance to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors develops.After initiation of antiretroviral therapy, the plasma viral load decreases to concentrations below the lower limit of detection of available commercial assays in most people, usually within 3 months (fi gure 3). By contrast, the recovery of CD4 T cells in individuals on antiretroviralSeminartherapy is variable. In one study77 of responses to antiretroviral therapy at 6 months in low-income countries, 56% of patients had a successful virological and CD4 response, 19% a virological response without a CD4 response, and 15% a CD4 response without a virological response. Individuals with impaired CD4 T-cell recovery despite virological suppression, which is associated with several risk factors (panel),78 are at increased risk of adverse outcomes, including serious non-AIDS events.79 Adjunctive interleukin 2 signifi cantly increases CD4 T-cell counts, but does not result in clinical benefi t.80 Interleukin 7, which enhances proliferation of both naive and memory T cells, also increases CD4 T-cell counts, although whether this results in enhanced clinical benefit is unknown.81 H owever, interleukin 7 might have the undesirable eff ect of expanding the pool of T cells that are latently infected with HIV.82 Guidelines in high-income countries allow clinicians to choose a starting regimen of dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors combined with either a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor, or an integrase inhibitor, because these three regimens have similar effi cacy and tolerability.83 Subsequent antiretroviral therapy regimen switches for virological failure are guided by the results of resistance testing. For low-income and middle-income countries, WHO recommends a public health approach to use of antiretroviral therapy with standardised fi rst-line (non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor plus dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors) andFigure 3: Natural history of untreated HIV infection and changes after antiretroviral therapy(A) In untreated HIV infection, CD4 T cells are progressively lost in blood but CD4 T cells in the gastrointestinal tract are rapidly depleted early on. (B) The acute response to HIV infection includes a dramatic increase in markers of immune activation and production of non-neutralising antibodies and HIV-specifi c CD4 and CD8 T cells that are associated temporally with a decrease in HIV RNA in blood. (C) After antiretroviral therapy, HIV RNA signifi cantly decreases followed by recovery of CD4 T cells, which varies between individuals (panel). By contrast, recovery of CD4 T cells in the gastrointestinal tract is reduced. (D) With reduction of HIV RNA and viral antigen, HIV-specifi c T cells decrease after antiretroviral therapy, whereas antibody persists in all patients. Immune activation decreases after antiretroviral therapy but in most patients remains signifi cantly increased compared with healthy controls. GIT=gastrointestinal tract. LPS=lipopolysaccharide.Seminarsecond-line (ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor plus dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors) regimens, and restricted monitoring for both effi cacy and toxic eff ects.84 Resistance testing is seldom available. Clinical and CD4 count monitoring is used in many low-income countries where viral load monitoring is unavailable, but this monitoring strategy85 results in both unnecessary switches to second-line therapy and continuation of failing first-line antiretroviral therapy regimens, which will increase the number of resistance mutations. Viral load monitoring would be cost eff ective in resource-limited settings if low-cost tests, which are available, were used.86Investigators of a study87 that compared a public health approach with individualised approaches to antiretroviral therapy in people starting treatment in South Africa and Switzerland, reported similar virological outcomes, but the switching rate for toxic effects in Switzerland was higher than in South Africa. Early mortality rates after initiation of antiretroviral therapy are much higher in resource-limited settings than in high-income countries after adjustment for baseline CD4 count, but the diff erence attenuates after 6 months.88 Near-normal life expectancy is estimated for patients (other than people who inject drugs) who achieve a normal CD4 count and a suppressed viral load on antiretroviral therapy.89 Increasing data suggest that short-course antiretroviral therapy started in early HIV infection might slow disease progression, but further studies of patients presenting with acute infection need to be done.90 Most international guidelines, including those for low-income and middle-income countries,84 have increased the CD4 criterion for initiation of antiretroviral therapy to 500 cells per μL or higher, despite no good evidence that antiretroviral therapy initiation at CD4 counts higher than 350 cells per μL provides individual benefi t.91 Increased access to antiretroviral therapy is expected to reduce HIV transmission, but the durability of this eff ect is unknown, and starting antiretroviral therapy early exposes patientsto toxic effects of drugs and the development of resistance before they derive clinical benefi t.92 Retention of patientsin care in low-income and middle income countries will be a major challenge because the number of people eligible for antiretroviral therapy will increase from 16·7 million to 25·9 million in 2013, if the WHO 2013 guidelines are introduced.4 In sub-Saharan Africa, 57% of people are expected to complete eligibility assessment for antiretroviral therapy, and only 65% of people who start treatment remain in care after 3 years.93 Loss to follow-up increased with increasing population size in a large antiretroviral therapy programme in South Africa.94 Low rates of retention care are not restricted to low-income and middle-income countries, as shown by a US report95 that noted that only 51% of patients who were diagnosed with HIV were retained in care in 2010.Antiretroviral therapy taken in the presence of continuing viral replication will result in the selection of sub-populations of H IV with mutations conferring resistance to antiretroviral drugs. Sub-optimum adherenceis the major factor associated with the development of resistance.96 Antiretroviral drugs diff er in their ability to select for resistant mutations. Some drugs (eg, emtricitabine, lamivudine, efavirenz, nevirapine, and raltegravir) rapidly select for one mutation conferring high-level resistance, whereas most other antiretrovirals select for resistance mutations slowly and need several resistant mutations before loss of drug effi cacy. Patients who develop antiretroviral resistance can transmit resistant virus to others. The prevalence of antiretroviral resistancein antiretroviral therapy-naive people in high-income countries has reached a plateau of 10–17% with resistanceto one or more antiretroviral drugs, whereas the prevalenceis steadily increasing in low-income and middle-income countries, reaching 6·6% in 2009.97 Guidelines for high-income countries recommend a resistance test before initiation of antiretroviral therapy, but this strategy is too expensive to implement in resource-limited settings. Immune reconstitution diseaseImmune reconstitution disease, also called immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, is an immunopathological response resulting from the rapid restoration of pathogen-specific immune responses to pre-existing antigens combined with immune dysregulation, which happens shortly after initiation of antiretroviral therapy.98 Most commonly, the antigens triggering immune reconstitution disease are from opportunistic infections, notably tuberculosis, cryptococcal meningitis, and cytomegalovirus retinitis.99 ImmunePanel: Factors associated with poor CD4 T-cell recovery after antiretroviral therapyHost factors• Older age, low CD4 nadir, high baseline HIV RNA• HLA type• Genetic polymorphisms in:• Chemokine/chemokine receptors—eg, CCR5D32,• Cytokine/cytokine receptors—eg, interleukin 7 receptor • Fas/Fas ligandViral factors• CXCR4 using virus• Co-infection with cytomegalovirus, hepatitis C virus, or GB virus CImmunological factors• Low thymic output• Poor bone marrow function• Increased immune activation• Proliferation• Senescence• Increased PD-1 expression• Increased apoptosisSeminarCD4 T cells in the presence of specifi c chemokines,104 orafter reversion of an activated infected T cell to a restingstate (fi gure 4).105 Latency has been shown in vivo incentral and transitional memory T cells,101,106 and in naiveT cells.107 Latency can also be established in monocyte-macrophages108 and astrocytes,109 but the importance ofthese cells to virus persistence in patients on antiretroviraltherapy is unclear.Many factors restrict effi cient HIV transcription from the integrated provirus in latently infected resting CD4 T cells including the sub-nuclear localisation of the provirus, the absence of transcription factors such as NF-kB and nuclear factor of activated T cells, the presence of transcriptional repressors, the epigenetic control of the H IV promoter (including histone modifi cation by acetylation and methylation, and DNA modifi cation), and sub-optimum concentrations of the virus protein tat.110 Additionally, post-transcriptional blocks including microRNAs restrict viral translation in resting T cells.111 Finally, latently infected T cells can undergo homoeostatic proliferation106 via stimulation from homoeostatic cytokines such as interleukin 7,82 which further contribute to their long half-life and persistence.Much interest surrounds the discovery of either a functional cure (long-term control of H IV without antiretroviral therapy) or a sterilising cure (complete elimination of all H IV-infected cells). Hopes that a cure might be possible have been raised by a case report of a man who underwent stem cell transplants for leukaemia,112 and an infant who started antiretroviral therapy soon after delivery.113 The best documented report of cure is the Berlin patient,112 a man with HIV on antiretroviral therapy who had acute myeloid leukaemia and received two bone marrow transplants from a donor with a homozygous defect in CCR5, a key coreceptor needed by HIV for cell entry. Shortly after transplantation, the patient ceased antiretroviral therapy and minimum or no virus has been detected in plasma or tissue for more than 6 years.114 This case has inspired the development of gene therapy to eliminate CCR5 in patient-derived T cells and stem cells with new technologies such as zinc fi nger nucleases that can eff ectively eliminate CCR5 expression.115Figure 4: Latency and activation of cellular HIV infection(A) Latency can be established via survival of an activated infected T cell, which reverts to a memory state, or after direct infection of a resting CD4 T cell in the presence of appropriate signalling mediated by either chemokines or cell-to-cell signalling. (B) Activating transcription from latency will induce HIV transcription (with an increase in cell associated unspliced RNA), HIV protein, and virion production with the aim of cell death induction by either virus-induced cytolysis or stimulation of HIV-specifi c cytotoxic T cells. Additional interventions that kill the cell might also be needed。

ORIGINAL ARTICLESeroprevalence of HIV ,HSV-2,and Treponema pallidum in the Kosovarian populationBARBARA SULIGOI 1,GIANLUCA QUAGLIO 2,VINCENZA REGINE 1,NASER RAMADANI 3,LUIGI BERTINATO 2,ARBEN CAMI 4,PIETRO DENTICO 5,ANNA VOLPE 5,MARIO FIGLIOMENI 1,LAURA CAMONI 1,GIOVANNI PUTOTO 2&GIOVANNI REZZA 1From the 1Epidemiology Unit,Department of Infectious Diseases,Istituto Superiore di Sanita `,Rome,2V eneto Region,Italian Cooperation,Peja Hospital Training Project T eam,V enice,Italy,3National Institute of Public Health,Pristina,4Ministry of Health,Pristina,Kosovo,and 5Institute of Internal Medicine,Immunology and Infectious Diseases,University of Bari,Bari,ItalyAbstractThe objective of this study was to evaluate the seroprevalence of infection with HIV,herpes simplex virus type 2(HSV-2),and Treponema pallidum (TP)in a Kosovarian population.A cross-sectional study was performed in Peja,Kosovo,from January to March 2005,among 1285persons recruited at the Peja Hospital.The seroprevalence of HIV,HSV-2,and TP was evaluated,and the viral correlates for each infection were analysed.No HIV-positive cases were found.The seroprevalence of HSV-2was 20.2%.The factors significantly associated with HSV-2infection at the multivariate analysis were:female gender (adjusted OR,1.73;95%CI 1.24Á2.41)and being married (adjusted OR,1.46;95%CI 1.06Á2.01).Three persons (0.2%)had a positive serology for TP .The only risk factor associated with TP infection was age ]50y.Our results show a low seroprevalence of HIV infection and TP,and a high seroprevalence of HSV-2in Kosovo.These findings suggest the need for appropriate surveillance systems,prevention programmes,and information aimed at controlling the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in this area.Moreover,the circulation of infections acquired through sexual contact may facilitate an increase in the sexually transmitted HIV epidemic in the near future.IntroductionKosovo is a province in southern Serbia that has beenunder United Nations administration since 1999andwhich has recently become an independent nation;the province has a population of 2million inhabitants,of whom more than 95%are ethnic Albanians.According to aggregated data from Serbia andMontenegro,which include data that cover Kosovo,the HIV/AIDS epidemic remains at a low level.In2005,56AIDS cases (rate:6.9per million)and 112new HIV diagnoses (13.8per million)were reported[1],with the highest rate in the urban area ofBelgrade.However,under-reporting of HIV casesmay exist and could be due to inadequate diagnosticfacilities,poor social and economic conditions,and the stigmatization or discrimination of high-risk groups [2].With regard to other sexually transmitted dis-eases,data are scarce,although a relatively high rate of infection with the herpes simplex virus type 2(HSV-2)has been observed among pregnant women and women of reproductive age in Serbia [3].Although condom use offers significant protec-tion against HSV-2infection in susceptible women [4],HSV-2infection deserves specific attention,given the availability of recent type-specific serolo-gical tests that allow for an accurate diagnosis and antiviral treatment that can reduce the spread of the virus through asymptomatic shedding and vertical transmission [5].Correspondence:V .Regine,Department of Infectious,Parasitic and Immunomediated Diseases,Istituto Superiore di Sanita `,Viale Regina Elena 299,00161Rome,Italy.(T el:'390649902273.Fax:'390649902755.E-mail:vincenza.regine@iss.it)Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases ,2009;41:608Á613(Received 24February 2009;accepted 12May 2009)ISSN 0036-5548print/ISSN 1651-1980online #2009Informa UK Ltd.(Informa Healthcare,Taylor &Francis As)DOI:10.1080/00365540903036204We conducted a cross-sectional study to evaluate the prevalence of infection with HIV,HSV-2,and Treponema pallidum(TP)in different population groups in the Peja region of Kosovo.The study was carried out in the framework of a training project for health workers at Peja Hospital(Peja Hospital Training Project-PHTP),which was performed between2004and2007with the technical support of the Veneto Regional Health Authority and the Italian GovernmentÁItalian Cooperation Agency[6]. Methods and materialsThe cross-sectional study was performed from1 January to30March2005,in Peja Hospital.The Peja region has an estimated population of357,000 inhabitants.Peja is the largest city in the region and has a population of approximately90,000inhabi-tants.Peja Hospital has460beds,82physicians,170 nurses/technicians,and23administrative personnel; in2005there were2584deliveries.The study population consisted of the following persons present at the hospital during the study period:1)all pregnant women admitted for delivery to Peja Hospital;2)all candidate blood donors being screened for donation suitability;3)a sample of children attending the Paediatric Department on an outpatient basis;4)a sample of adults attending the Outpatient Department(persons undergoing rou-tine laboratory testing on Monday,Wednesday and Friday;and5)all of the hospital’s healthcare workers (physicians,nurses/technicians and administrative personnel).The study was approved by the Institute of Public Health of Kosovo,and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.Demographic and clinical data were collected using a structured questionnaire,administered during an interview. The data included:age,gender,marital status, education,occupation,work activities abroad,area of residence(urban or rural area),previous surgical procedures,history of hospitalization,transfusion of blood/blood products,and other medical treatment (intramuscular injection,dental care).From each person,a sample of blood was drawn for testing for antibodies against HIV,HSV-2,and TP.The blood samples were divided into3serum aliquots:2aliquots of2ml each were sent to Italy, and1aliquot of0.5ml was stored at(208C in the Peja Hospital laboratory.A line immunoassay(INNO-LIA HIV I/II Score, Innogenetics N.V.,Ghent,Belgium)was used for detecting antibodies to HIV types1and2,and samples that were reactive were confirmed with Western blot.For detecting anti-HSV-2antibo-dies,a commercial HSV-2specific IgG enzyme immunoassay(HSV2IgG EIA WELL,Radim, Pomezia,Italy)was used.IgG and IgM antibodies to TP were detected by a TP recombinant enzyme immunoassay(Syphilis Screening Recombinant EIA WELL,Radim,Pomezia,Italy).The prevalence of HIV,HSV-2and TP was evaluated for the5different population groups involved in the study(i.e.pregnant women,blood donors,paediatric and adult outpatients,and health-care workers).The viral correlates of each infection were evaluated by estimating crude odds ratios(OR) for each demographic and clinical variable.T o assess the statistical significance of the differences,95% confidence intervals(CI)of the ORs were calcu-lated.T o assess independent associations between the study variables and the presence of each virus,a multivariate analysis was conducted including those variables that were significantly associated(p B0.10) at the univariate analysis,and the adjusted ORs were calculated.ResultsThe study population consisted of1285persons, specifically:334pregnant women(26%),301can-didate blood donors(23%),181children(5Á18y of age)attending the Paediatric Department on an outpatient basis(14%),218adults attending the adult Outpatient Department(17%),and251 healthcare workers(20%);74persons refused to participate.The mean age of the1285study participants was 31y(Standard Deviation,12.5);36.0%of the participants were males.More than half of the participants(55.5%)lived in a rural area,66.6% were married,12.1%worked abroad,and30.1% had a relative abroad.The sociodemographic char-acteristics for each study group are shown in T able I. None of the study participants had HIV infection. Positivity to anti-HSV-2was found in260persons (20.2%)(T able II);the highest HSV-2seropreva-lence was found among pregnant women(35.0%) and the lowest among candidate blood donors (8.6%).The risk factors associated with HSV-2infection are shown in T able III;medical treatment(surgical procedures,hospitalization,transfusion and others) were not included in the analysis because they are not correlated with HSV-2transmission.The socio-demographic risk factors independently associated with HSV-2infection at the multivariate analysis were female gender and being married.Overall,3(0.2%)persons had a positive serology for TP(T able II).Two of them were males and2 were older than50y of age.All cases were married, lived in an urban area,and were employed.The only HIV,HSV-2,and syphilis in Kosovo609risk factor significantly associated with TP infection was age]50y(OR,21.3;95%CI1.9Á237.0). DiscussionThis is the first large-scale survey of selected sexually transmitted infections among the general population in Kosovo.Although the data are restricted to the population living in and around Peja,the socio-economic and living conditions are substantially uniform in Kosovo;thus the data can be considered as indicative for Kosovo as a whole.Kosovo has many of the ingredients for the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic,such as a highly mobile population,sexually active youth,a large and rapidly changing international presence, increasing injecting drug use,a thriving commercial sex trade,and low condom acceptance and use[7,8]. However,as found in other central European countries,the HIV epidemic appears to have re-mained at a low level,as confirmed by our results. Conversely,HSV-2,which is an important cofactor for HIV infection[9],shows a high prevalence in this area.With specific regard to HSV-2infection,the prevalence in our study is higher than that reported among the general population in any other European country,except Bulgaria,where the reported pre-valence is24%[10Á12];it is also higher than the prevalence reported in the USA[13].The preva-lence of HSV-2antibodies among pregnant women (35.0%)is higher than that reported in a similar population in Serbia(12.5%)and in some indus-trialized countries[12,14,15],yet it is similar to that reported in some economically developing countries [16,17].We also found a very high HSV-2preva-lence among children aged5Á18y,although the reason for this is not clear.Although early sexual intercourse or sexual abuse could be responsible [18],anecdotal reports from Italian healthcare work-ers of the PHTP indicate that this is probably not the case.Considering the high prevalence among preg-nant women,we cannot exclude the possibility that at least a proportion of infants has maternal anti-bodies.It can also be hypothesized that a proportion of these cases may be attributed to false positive HSV-2tests or to cross-reactivity of anti-HSV-2 antibodies with antibodies to other herpetic infec-tions that are common in childhood[19,20].The HSV-2prevalence found among blood do-nors(8.6%)is consistent with that reported in similar studies conducted in other European coun-tries[10,21].Unlike most international studies, which have found that HSV-2prevalence increases with increasing age[11,13],in our study the prevalence decreased with age.This can be ex-plained by a late spread of this infection in Kosovo, probably because of increased sexual exposure to individuals at higher risk of sexually transmitted infections(e.g.foreigners,soldiers)in recent y[22]. In agreement with a previous study,we found that females had a significantly higher risk of HSV-2 infection compared to males.This can be explained by the differential role of gender on clinical pre-sentation,with men being more likely to have asymptomatic HSV-2infection,which may have a differential impact on sexual behaviour and could result in higher rates of male-to-female transmission [12].Because it has been demonstrated that condom use offers significant protection against HSV-2 infection in susceptible women[4],condom use must be encouraged.Unlike previous studies[13], we found a higher risk of HSV-2infection among married persons compared to unmarried persons, which could be explained by the high number ofT able I.Sociodemographic characteristics of the different study groups(column percentages),Peja,Kosovo,2005.Pregnantwomen (n0334)Blood donors(n0301)Paediatricoutpatients(n0181)Adultoutpatients(n0218)Healthcareworkers(n0251)T otal(n01285)Male0.0%86.4%37.0%33.0%24.3%35.8% Mean age in y(SD)29.1(5.8)34.0(9.9)12.5(3.2)36.7(13.6)39.2(10.6)32.3(13.6) Living in rural area72.3%70.9%48.3%51.4%23.3%55.5% Married99.4%66.8% 2.2%64.5%70.7%66.6% Unemployed57.7%27.0%0.0%23.6%0.0%25.4% Work abroad9.6%28.2%0.6% 6.5%9.6%12.1% Relatives abroad26.6%33.6%14.4%31.7%40.6%30.1% Surgical procedure10.5% 4.0% 2.8% 6.9%7.2% 6.6% Hospitalization0.3% 1.0%7.2%7.8%7.6% 4.1% Transfusion0.6%0.7% 1.7% 4.1%8.4% 2.9% Dental care15.9%15.6%51.9%50.0%41.4%31.7% Intramuscular injection11.1% 4.3%67.8%58.3%52.2%33.5% 610 B.Suligoi et al.pregnant women in our study who had high rates of infection.In interpreting the results for HSV-2infection,the limits of the test used in our study must be considered,in that the test may have produced an overestimate of the prevalence of HSV-2,especially in the paediatric population.The first limit is the cross-reactivity with HSV-1infection;the HSV-2 antibody assay does not easily distinguish between HSV-1and HSV-2.Thus,we cannot exclude that the prevalence of cold sores and HSV-1seropreva-lence might be high in Kosovo,as in some other East European countries[11].Another limit could be due to the lower specificity of the test and a larger number of false positives when used for the general population,as opposed to persons attending clinics for sexually transmitted infections[19].With regard to syphilis,the seroprevalence of TP antibodies among candidate blood donors was at least10times higher than that reported in Western European countries[23],yet lower than that re-ported in some Eastern European countries and developing countries[24,25].The finding of a higher prevalence among older persons is consistent with the increase of syphilis seroprevalence with age, due to the persistence of antibodies elicited byT able II.Seroprevalence of HSV-2and Treponema pallidum among different groups,Peja,Kosovo,2005.HSV-2 No.positive/totalHSV-2prevalence%(95%CI)Treponema pallidum serologyNo.positive/T otalTreponema pallidumseroprevalence%(95%CI)Population groupPregnant women117/33435.0(29.9Á40.4)0/3340.0Blood donors26/3018.6(5.7Á12.4)1/3010.3(0.0Á1.8) Paediatric outpatients35/18119.3(13.9Á25.9)0/1810.0Adult outpatients23/21810.6(6.8Á15.4)0/2180.0Healthcare workers59/25123.5(18.4Á29.2)2/2510.8(0.1Á2.8)T able III.Risk factors for HSV-2infection,Peja,Kosovo,2005.HSV-2-negative HSV-2-positive HSV-2-prevalence Unadjusted OR Adjusted ORNo.No.%(95%CI)(95%CI) GenderMale3976313.711Female62819723.9 1.98(1.45Á2.70) 1.73(1.24Á2.41) Age group5Á181533619.01Á19Á293419321.4 1.16(0.75Á1.78)30Á392587422.3 1.22(0.78Á1.90)40Á491713717.80.92(0.55Á1.53)]50951614.40.72(0.38Á1.36)Marital statusNot married3606715.711Married65819322.7 1.58(1.16Á2.14) 1.46(1.06Á2.01) Area of residenceUrban46010819.01ÁRural55715121.3 1.15(0.88Á1.52)Number of years of education58years40610720.91Á 8years61115219.90.94(0.71Á1.25)Employment statusUnemployed57116622.5 1.38(1.04Á1.83) 1.22(0.90Á1.64) Employed4419317.411Work abroadNo89722420.01ÁY es1193623.2 1.21(0.81Á1.81)Partner abroadNo99824619.811Y es271434.1 2.10(1.08Á4.07) 1.50(0.77Á2.94)HIV,HSV-2,and syphilis in Kosovo611previous syphilitic infections[25].However,because these very individuals were positive to TP antibodies in our study,the results must be considered with caution.In summary,the results of our study show that the profile of HSV-2prevalence in Kosovo lies some-where between the profiles in Western Europe and those in developing countries,suggesting an urgent need for:1)information campaigns aimed at de-creasing the spread of HSV-2in the general popula-tion by increasing condom use in all non-permanent sexual relations and changes in sexual behaviour;2) training courses for family doctors and microbiolo-gists,so as to improve the correct and timely diagnosis of the disease(including the use of type-specific serological tests);and3)epidemiological studies to evaluate HSV-2incidence among preg-nant women and neonates,in consideration of the potential introduction of HSV-2screening for preg-nant women.Moreover,our results show a low prevalence of HIV infection and TP,yet a high prevalence of HSV-2,especially in certain sub-groups,suggesting that the prevalence of HIV infection and TP could increase in the near future. Our findings stress the need for appropriate surveil-lance systems,prevention programmes,and infor-mation targeted at controlling the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in this area. AcknowledgementsWe thank Mark Kanieff for his assistance in revising the manuscript.For their help and suggestions,we are also indebted to:Nicola Schinaia,Istituto Super-iore di Sanita`,Rome,Italy;Vincenzo Racalbuto, Italian Cooperation Agency,Rome,Italy;Ali Ber-isha,Ministry of Health,Kosovo;Adnora Nurboja, Institute of Public Health,Peja,Kosovo;Nergize Gjuka,Blood Transfusion Unit,Regional Hospital of Peja,Kosovo.This study was funded by the‘VI Programma Nazionale di Ricerca sull’AIDS2006,area Epide-miologia’,Istituto Superiore di Sanita`,Ministry of Health,Italy.Declaration of interest:The authors report no conflicts of interest.The authors alone are respon-sible for the content and writing of the paper. References[1]EuroHIV.HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe.End-yearreport2005.Saint-Maurice:Institut de veille sanitaire, 2006No.73.Available from:/re ports/report_73/pdf/report_eurohiv_73.pdf[accessed11 Mar2008].[2]UNAIDS.Serbia and Montenegro.Country situation ana-lysis.Available from:/en/Regions_Coun tries/Countries/serbia_and_montenegro.asp[accessed11 Mar2008].[3]Dordevic´H.Serological response to herpes simplex virustype1and2infection among women of reproductive age.Med Pregl2006;59:591Á7.[4]Wald A,Langenberg AGM,Link K,Izu AE,Ashley R,Warren T,et al.Effect of condoms on reducing the transmission of herpes simplex virus type2from men to women.JAMA2001;24:3100Á6.[5]Hollier L,Wendel G.Third trimester antiviral prophylaxisfor preventing maternal genital herpes simplex virus(HSV) recurrences and neonatal infection.Cochrane Database Syst Rev2008;(1):CD004946.[6]Quaglio G,Ramadani N,Pattaro C,Cami A,Dentico P,Volpe A,et al.Prevalence and risk factors for viral hepatitis in the Kosovarian population:implications for health policy.J Med Virol2008;80:833Á40.[7]UNMIK.Social Affairs-HIV/AIDS.Time to face the truth.Available from:/pub/focuskos/ dec02/focusksocaffair1.htm[accessed11Mar2008].[8]World Bank2005.Kosovo Poverty Assessment.Promotingopportunity,security,and participation for all.Poverty reduction and economic management unit.Europe and Central Asia Region.Report n.32378-XK.Available from: /external/default/WDSConte ntServer/WDSP/IB/2005/07/13/000012009_20050713091826/Rendered/PDF/323780rev.pdf[accessed11Mar2008].[9]Fleming DT,Wasserheit JN.From epidemiological synergyto public health policy and practice:the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection.Sex Transm Infect1999;75:3Á17.[10]Suligoi B,Cusan M,Santopadre P,Palu`G,Catania S,Girelli G,et al.HSV-2specific seroprevalence among various populations in Rome,Italy.The Italian Herpes Management Forum.Sex Transm Infect2000;76:213Á4. [11]Pebody RG,Andrews N,Brown D,Gopal R,De Melker H,Franc¸ois G,et al.The seroepidemiology of herpes simplex virus type1and2in Europe.Sex Transm Infect2004;80: 185Á91.[12]Dordevic´H.Serological response to herpes simplex virustype1and2infection among women of reproductive age.Med Pregl2006;59:591Á7.[13]Xu F,Sternberg MR,Kottiri BJ,McQuillan GM,Lee FK,Nahmias AJ,et al.Trends in herpes simplex virus type1and type2seroprevalence in the United States.JAMA2006;296: 964Á73.[14]Wutzler P,Doerr HW,Fa¨rber I,Eichhorn U,Helbig B,Sauerbrei A,et al.Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type1and type2in selected German populations:relevance for the incidence of genital herpes.J Med Virol2000;61: 201Á7.[15]Gaytant MA,Steegers EA,van Laere M,Semmekrot BA,Groen J,Weel JF,et al.Seroprevalences of herpes simplex virus type1and type2among pregnant women in the Netherlands.Sex Transm Dis2002;29:710Á4.[16]Kamali A,Nunn AJ,Mulder DW,van Dyck E,Dobbins JG,Whitworth JA.Seroprevalence and incidence of genital ulcer infections in a rural Ugandan population.Sex Transm Infect 1999;75:98Á102.[17]Mbizvo EM,Msuya Sia E,Stray-Pedersen B,Chirenje MZ,Munjoma M,Hussain A.Association of herpes simplex virus type2with the human immunodeficiency virus among urban women in Zimbabwe.Int J STD AIDS2002;13: 343Á8.612 B.Suligoi et al.[18]Kasubi MJ,Nilsen A,Marsden HS,Bergstro¨m T,LangelandN,Haarr L.Prevalence of antibodies against herpes simplex virus types1and2in children and young people in an urban region in T anzania.J Clin Microbiol2006;44:2801Á7. [19]van Dyck E,Buve´A,Weiss HA,Glynn JR,Brown DW,deDeken B,et al.Performance of commercially available enzyme immunoassays for detection of antibodies against herpes simplex virus type2in African populations.J Clin Microbiol2004;42:2961Á5.[20]Ramos S,Lukefahr JL,Morrow RA,Stanberry LR,Ro-senthal SL.Prevalence of herpes simplex virus types1and2 among children and adolescents attending a sexual abuse clinic.Pediatr Infect Dis J2006;25:902Á5.[21]Uusku¨la A,Nygard-Kibur M,Cowan FM,Mayaud P,French RS,Robinson JN,et al.The burden of infection with herpes simplex virus type1and type2:seroprevalence study in Estonia.Scand J Infect Dis2004;36:727Á32.[22]Brisson AE.HIV/AIDS.Time to face the truth.Availablefrom:/pub/focuskos/dec02/fo cuskoscaffair1.htm[accessed11Mar2008].[23]Council of Europe.Report on the collection,testing and useof blood and blood products in Europe in2003.Available from:http://www.coe.int/t/dg3/health/Source/2003reportf inal_en.pdf[accessed11Mar2008].[24]Matee MI,Magesa PM,Lyamuya EF.Seroprevalence ofhuman immunodeficiency virus,hepatitis B and C viruses and syphilis infections among blood donors at the Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam,T anzania.BMC Public Health2006;6:21.[25]Nakashima AK,Rolfs RT,Flock ML,Kilmarx P,Greenspan JR.Epidemiology of syphilis in the United States, 1941Á1993.Sex Transm Dis1996;23:16Á23.HIV,HSV-2,and syphilis in Kosovo613。