Fool's paradise作者介绍

- 格式:doc

- 大小:105.00 KB

- 文档页数:8

《Criminal Minds犯罪心理》第四季精选名言中英文对照(2010-01-27 02:13:35)标签:criminalminds犯罪心理第四季名言娱乐分类:羙劇天下◎Episode 1: Mayhem(2008.09.24)●Never think that war, no matter how necessary nor how justified is not a crime.——Ernest Hemingway【海明威:任何战争都是罪恶,不管是否所谓必须,也无论是否所谓公正。

】(Hotch)(本集片尾没有出现名言)◎Episode 2: The Angel Maker(2008.10.01)●We all die. The goal isn't to live forever, the goal is to create something that will.——Chuck Palahniuk【恰克·帕拉尼克(美国作家,有俄裔和法裔血统,祖上多人死于谋杀,身世离奇,1962年生人,1996年出版其第一部长篇小说『搏击俱乐部(Fight Club)』):人终有一死。

活着并不是为了不朽,而是为了创造不朽。

】(Hotch)●The past is our definition. We may strive, with good reason, to escape it, or to escape what is bad in it, but we will escape it only by adding something better to it.——Wendell Berry【温德尔·贝瑞(1934年生,美国诗人、随笔作家和小说家,同时也是一位农民):过去是我们给自己下的定义。

我们有很好的理由去努力摆脱它,或是摆脱它的阴影,但摆脱它的唯一途径是添以更美之景。

foolparadise泛读课文寓意

在现实生活中,人们常常会追求一种理想的、完美的乌托邦境界,但这种所谓的“天堂”却往往是一个幻想的、不切实际的梦境。

这种现象可以被称为“foolparadise”(愚人天堂),它代表着人们对于理想或者幸福的错误理解与追求。

在社交媒体的时代,人们经常通过精心策划的照片和完美的文字来展示自己过上了理想的生活,而实际上他们只是在创造一个“foolparadise”。

这种虚假的幸福感使得人们无法真实地面对自己的困境和问题,进一步加深了对完美生活的追求。

然而,这种追求只会让人们越来越远离现实,陷入一个虚幻的世界。

另一方面,“foolparadise”也可以被理解为对于权力和财富的追逐。

人们往往误以为通过追求权力和财富就能够达到幸福。

然而,当他们真正获得了所追求的权力和财富时,却发现这并不能带来真正的满足感和幸福。

他们陷入了一个幻想的天堂,却忽视了内心真正的需求。

在文学作品中,作者往往通过描述主人公对于“foolparadise”的追求和最终的破灭来传达深刻的寓意。

这种寓意告诉我们,追求完美、追求幸福是人类的本能,但我们必须意识到现实世界并不是理想的,完美的幸福只存在于我们的想象中。

我们应该学会面对现实,接受自己的不完美,并在现实中找到真正的快乐和满足。

因此,我们应该从“foolparadise”中醒悟过来,不要被虚假的幸福欺骗。

我们应该珍惜真实的生活,追求内心真正的满足。

只有在真实面对现实的同时,才能找到真正的快乐和幸福。

约翰·弥尔顿的英文诗约翰·弥尔顿(John Milton,1608~1674)英国诗人、政论家,民主斗士。

弥尔顿是清教徒文学的代表,他的一生都在为资产阶级民主运动而奋斗,代表作《失乐园》是和《荷马史诗》、《神曲》并称为西方三大诗歌。

Paradise Lost译为“失乐园”。

作品介绍《失乐园》(Paradise Lost),全文12卷,以史诗一般的磅礴气势揭示了人的原罪与堕落。

诗中叛逆天使撒旦,因为反抗上帝的权威被打入地狱,却仍不悔改,负隅反抗,为复仇寻至伊甸园。

亚当与夏娃受被撒旦附身的蛇的引诱,偷吃了上帝明令禁吃的分辨善恶的树上的果子。

最终,撒旦及其同伙遭谴全变成了蛇,亚当与夏娃被逐出了伊甸园。

该诗体现了诗人追求自由的崇高精神,是世界文学史、思想史上的一部极重要的作品。

“失乐园”的由来是从《圣经》创世纪中所诉的故事中得来的:亚当和夏娃偷食禁果以后,世界便为此颠倒。

原来温暖如春的天空中盘旋着背离上帝的寒流,凉风一阵紧似一阵地吹过来,世间的一切都开始变得紊乱而不和谐。

道分阴阳,动静相摩,高下相克。

人失去了天真烂漫、无忧无虑的童年,注定要经历酸甜苦辣的洗礼,体验喜怒哀乐的无常。

智慧是人类脱离自然界的标志,也是人类苦闷和不安的根源。

上帝在园中行走,亚当和夏娃听见他的脚步声。

此时他们的心与上帝有了罅隙,出于负罪感,他们开始在树林中躲避上帝。

上帝对人的失落发出了痛切的呼唤:“亚当,你在那里?人哪,你在哪里?”这呼唤中包涵着上帝对人犯罪堕落,失掉了赐给人原初的绝对完美的忧伤与失望,又包涵着对人认罪归来,恢复神性的期待。

然而在上帝一步紧似一步的追问面前,亚当归咎于夏娃,夏娃委罪于蛇。

这就是上帝对人类最初的失望与忧伤,这就是人类背离上帝的最初堕落与痛苦。

亚当对上帝说:“我在园中听见您的声音,就害怕,因为我赤身露体,我便藏了起来。

”“谁告诉你赤身露体的呢?莫非你吃了我吩咐你不可吃的那树上的果子么!”上帝知道他已背离了自己的意志,愤怒地质问。

名人名言感谢你的阅读

托马斯·富勒名言

导语:托马斯·富勒名言

1、对瑕疵眼开眼闭吧,因为你还有大错。

——托马斯·富勒

2、A fool's paradise is a wise man's hell. 愚者的天堂,便是智者的地狱。

——托马斯·富勒《犯罪心理第四季》

3、诚实者既不怕光也不怕黑暗。

——托马斯·富勒

4、良心平静,在雷声中也睡得着。

——托马斯·富勒

5、习惯是智者的祸患、蠢货的偶像。

——托马斯·富勒

6、宁肯与好人一起咽糟糠,不愿与坏人一起吃筵席。

——托马斯·富勒

7、如果你的欲望是无止境的,那么你的操心和恐惧也将会这样。

——托马斯·富勒

8、伟人,和好人,通常不是一个人。

——托马斯·富勒《箴言集》

9、知识是珍宝,但实践是得到它的钥匙。

——托马斯·富勒

10、Care and diligence bring luck.细心和勤奋能带来好运。

——托马斯·富勒。

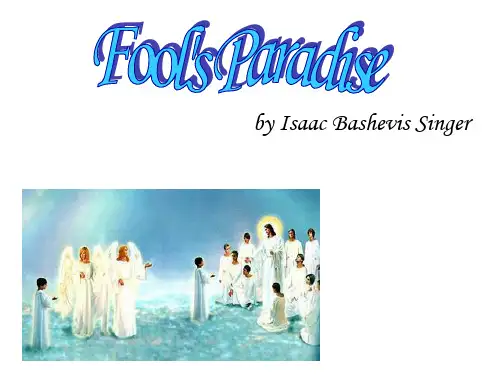

Text OneFool's Paradiseby Isaac Bashevis SingerIntroduction—-What is paradise like?Would people live happily in paradise?Atzel dreams to live in paradise and becomes ill。

To the grief of his parents,he is willing to die. Why does Atzel want to go to paradise so much?Will his illness be cured? Please read the following cautionary tale magically told by the 1978 Nobel Prize winner in literature。

1.Somewhere,sometime,there lived a rich man whose name was Kadish。

He had an only son who was called Atzel。

On the household of Kadish there lived a distant relative,an orphan girl,called Aksah。

Atzel was a tall boy with black hair and black eyes。

Aksah had blue eyes and golden hair。

Both were about the same age。

As children,they ate together,studied together, played together。

It was taken for granted that when they grew up they would marry.2.But when they had grown up,Atzel suddenly became ill。

约翰米尔顿(John Milton) 1608-1674Major works:(1) Paradise Lost.失乐园(2) Paradise Regained. 复乐园(3) Samson Agonistes.力士参孙约翰.弥尔顿,伟大的诗人,革命文豪。

很多文学批评家都认为,英国诗人中除了莎士比亚之外,当首推弥尔顿。

他生于伦敦,在剑桥大学的克莱斯特学院获得学士和硕士学位后,便开始专心于诗歌创作。

1632年至1638年五年间,弥尔顿辞去了政府部门的工作,住到他父亲郊外的别墅中,整日整夜的阅读,他几乎看全了当时所有英语、希腊语、拉丁语和意大利语作品。

在这段时期弥尔顿写作了《酒神之假面舞会》等一些作品。

1632年至1637年期间,弥尔顿几乎读遍了当时所有英语,希腊语,拉丁语和意大利语的作品。

1638年,弥尔顿去欧洲旅行,他在意大利停留了大部分时间。

由于英国动荡的宗教局面弥尔顿提前回国,他所写的一些小册子被歪曲,他本人也被烙上了激进分子的烙印。

1642年,弥尔顿与玛利·普威尔结婚,新娘只有十七岁。

六个星期后,无法处理好新婚生活的玛利回到了她父母家,弥尔顿写信要求离婚。

但最终他们和解了,玛利为弥尔顿生下了四个孩子,其中的一个孩子生下没多久就夭折了。

1651年,弥尔顿原本就衰弱的视力变得更坏,他彻底失明了。

玛利死后,弥尔顿再婚,几个月后,这位新妻子因为难产而死。

弥尔顿的第三任妻子是伊丽莎白·明萨尔,这段婚姻维持的较长也较幸福。

1639年,由于英国动荡的宗教和政治形势,弥尔顿于翌年回国,准备投身于即将爆发的英国革命。

弥尔顿随后写出一系列政论文,支持清教徒的革命。

1649年他担任克伦威尔派的弥尔顿曾在其国务会议中任拉丁文秘书。

他先后写了《为英国人声辩》,《再为英国人声辩》两篇檄文,为”弑君“正名,成功地反击了欧洲的保皇派,自己也因此声望大增。

由于过度疲劳,弥尔顿于1652年双目失明,他随即辞去了公职,但从未停止为革命呐喊,在复辟前两个月还发表了《建立共和国的捷径》一文。

foolparadise泛读课文寓意foolparadise泛读课文寓意'foolparadise'是一个词语的组合,由'fool'(傻瓜)和'paradise'(天堂)组成。

因此,'foolparadise'可以被理解为一个虚幻的天堂,或者是傻瓜们所创造出来的幻境。

在泛读课文中,'foolparadise'的寓意可以被理解为一种幻想的境地,一个不切实际的虚构现实。

这个课文可能描述了一个由傻瓜们创造出来的理想世界,但这个世界的真实性或可行性却是值得质疑的。

这个课文可能通过夸张和幽默的手法来揭示人们在现实生活中逃避现实、追求虚幻幸福的倾向。

它可能探讨了人们沉迷于幻想中的原因,以及这种行为可能带来的后果。

课文中的人物或情节可能展示了人们如何在'foolparadise'中追逐虚幻的欢乐,但最终却发现这个幻境是不可持续的,也无法满足他们真正的需求和欲望。

这个课文还可以通过'foolparadise'的形象来探讨现实与幻想之间的冲突。

它可能呼吁人们要面对现实,不要被虚幻的幸福所迷惑,而是要寻求真实、可持续的快乐和满足。

在扩展这个主题时,可以考虑以下方面:1. 生活中的'foolparadise':探讨现实生活中人们可能创造的虚假世界,例如过度沉迷于社交媒体的人们如何为自己建立一个完美的虚构形象。

2. 幻想与现实的平衡:讨论人们如何在追求梦想同时保持对现实的认知和应对现实问题。

3. 社会对'foolparadise'的影响:研究社会如何利用虚幻幸福的概念来操纵和欺骗人们,例如广告行业如何利用虚假的承诺来吸引消费者。

4. 'foolparadise'的心理学意义:探索为什么人们倾向于逃避现实,以及如何建立一个更加真实和有意义的生活。

5. 从'foolparadise'中觉醒:讨论人们如何意识到他们生活在虚假幻境中,并寻求更为真实和有意义的生活方式。

Isaac Bashevis Singer Isaac Bashevis SingerBorn November 21, 1902 Leoncin, Congress PolandDied July 24, 1991 (aged 88) Surfside, Florida, USAOccupation Novelist, short story writer Language YiddishEthnicity Polish JewCitizenship United StatesGenres Fictional proseNotable work(s)The Magician of Lublin A Day of PleasureNotable award(s)Nobel Prize in Literature 1978Isaac Bashevis Singer (Yiddish: רעגניז סיװעשאַב קחצי; November 21, 1902 (see notes below) – July 24, 1991) was a Polish-born, Jewish-American author. He was a leading figure in the Yiddish literary movement and won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978.[1] He won two U.S. National Book Awards, one in Children's Literature for his memoir A Day Of Pleasure: Stories of a Boy Growing Up in Warsaw[2] and one in Fiction for his collection A Crown of Feathers and Other Stories.[3] BiographyEarly lifeIsaac Bashevis Singer was born in 1902 in Leoncin village near Warsaw, Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. A few years later, the family moved to a nearby Polish town of Radzymin, which is often and erroneously given as his birthplace. The exact date of his birth is uncertain, but most probably it was November 21, 1902, a date that Singer gave both to his official biographer Paul Kresh,[4]and his secretary Dvorah Telushkin.[5] It is also consistent with the historical events he and his brother refer toin their childhood memoirs. The often-quoted birth date, July 14, 1904 was made up by the author in his youth, most probably to make himself younger to avoid the draft.His elder siblings—brother Israel Joshua Singer(1893–1944) and sister Esther Kreitman (1891–1954)--were also writers. Esther was the first in the family to write stories.The family moved to the court of the Rabbi of Radzymin in 1907, where his father became head of the Yeshiva. After the Yeshiva building burned down in 1908, the family moved to Krochmalna Street in the Yiddish-speaking poor Jewish quarter of Warsaw, where Singer grew up. There his father acted as a rabbi —i.e., judge, arbitrator仲裁人, religious authority and spiritual leader.[8]World War IIn 1917, because of the hardships of World War I, the family split up. Singer moved with his mother and younger brother Moshe to his mother's hometown of Biłgoraj, a traditional Jewish town or shtetl,where his mother's brothers had followed his grandfather as rabbis. When his father became a village rabbi again in 1921, Singer went back to Warsaw, where he entered the Tachkemoni Rabbinical Seminary and soon decided that neither the school nor the profession suited him. He returned to Biłgoraj, where he tried to support himself by giving Hebrew lessons, but soon gave up and joined his parents, considering himself a failure. In 1923 his older brother Israel Joshua arranged for him to move to Warsaw to work as a proofreader for the Literarische Bleter, of which he was an editor.United StatesIn 1935, four years before the German invasion and the Holocaust, Singer emigrated from Poland to the United States due to the growing Nazi threat in neighboring Germany.The move separated the author from his common-law first wife Runia Pontsch and son Israel Zamir (b.1929), who instead went to Moscow and then Palestine (they would meet in 1955). Singer settled in New York, where he took up work as a journalist and columnist for The Forward (), a Yiddish-language newspaper. After a promising start, he became despondent and felt for some years "Lost in America" (title of a Singer novel, in Yiddish from 1974 onward, in English 1981). In 1938, he met Alma Wassermann (born Haimann) {b.1907-d.1996}, a German-Jewish refugee from Munich whom he married in 1940. After the marriage he returned to prolific writing and to contributing to the Forward,using, besides "Bashevis," the pen names "Varshavsky" and "D. Segal."[11]They lived for many years in the Belnord on Manhattan's Upper West Side. In 1981, Singer delivered a commencement address at the University at Albany, and was presented with an honorary doctorate.Singer died on July 24, 1991 in Surfside, Florida, after suffering a series of strokes. He was buried in Cedar Park Cemetery, Emerson.[14][15] A street in Surfside, Florida is named Isaac Singer Boulevard in his honor. The full academic scholarship for undergraduate students at the University of Miami is named in his honor.WritingSinger's first published story won the literary competition of the "literarishe bletter" and garnered him a reputation as a promising talent. A reflection of his formative years in "the kitchen of literature"[5]can be found in many of his later works. I. B. Singer published his first novel Satan in Goray in installments in the literary magazine Globus, which he cofounded with his life-long friend, the Yiddish poet Aaron Zeitlin in 1935. It tells the story of events in 1648 in the village of Goraj (close to Biłgoraj), where the Jews of Poland lost a third of their population in a cruel uprising by Cossacks, and details the effects of the seventeenth-century faraway false messiah Shabbatai Zvi on the local population. Its last chapter imitates the style of medieval Yiddish chronicle. With a stark depiction of innocence crushed by circumstance, the novel appears to foreshadow coming danger. In his later work The Slave (1962), Singer returns to the aftermath of 1648, in a love story between a Jewish man and a Gentile woman, where he depicts the traumatized and desperate survivors of the historic catastrophe with even deeper understanding.The Family MoskatSinger became an actual literary contributor to the Forward only following his older brother's death in 1945, when he published The Family Moskat in his honor. But his own style showed in the daring turns of his action and characters, with (and this in the Jewish family-newspaper in 1945) double adultery in the holiest of nights of Judaism, the evening of Yom Kippur. He was almost forced to stop writing the novel by his legendary editor-in-chief, Abraham Cahan, but was saved by readers who wanted the story to go on. After this, his stories—which he had published in Yiddish literary newspapers before—were printed in the Forward as well. Throughout the 1940s, Singer's reputation grew. After World War II and the near destruction of the Yiddish-speaking peoples, Yiddish seemed to be a dead language. Though Singer had moved to the United States, he believed in the power of his native language and maintained that there was still a large audience that longed to read in Yiddish. In an interview in Encounter (Feb. 1979), he claimed that although the Jews of Poland had died, "something—call it spirit or whatever—is still somewhere in the universe. This is a mystical kind of feeling, but I feel there is truth in it."Some of his colleagues and readers were shocked by this all-encompassing view of human nature. He wrote about female homosexuality ("Zeitl and Rickel" [16]("Tseytl un Rikl") in "The Seance and Other Stories"[17]), transvestitism ("Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" in "Short Friday"), and of rabbis corrupted by demons ("Zeidlus the Pope" in"Short Friday"). In those novels and stories which seem to recount his own life, he portrays himself unflatteringly (with some degree of accuracy) as an artist who is self-centered yet has a keen eye for the sufferings and tribulations of others.Literary influencesSinger had many literary influences; besides the religious texts he studied there were the folktales he grew up with and worldly Yiddish detective-stories about "Max Spitzkopf" and his assistant "Fuchs";[6]there was Dostoyevsky, whose Crime and Punishment he read when he was fourteen;[18] and he writes about the importance of the Yiddish translations donated in book-crates from America, which he studied as a teenager in Bilgoraj: "I read everything: Stories, novels, plays, essays...I read Rajsen, Strindberg, Don Kaplanowitsch, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Maupassant and Chekhov."[18] He studied many philosophers, among them Spinoza,[18]Arthur Schopenhauer,[7] and Otto Weininger.[6] Among his Yiddish contemporaries Singer himself considered his older brother to be his greatest artistic example; he was a life-long friend and admirer of the author and poet Aaron Zeitlin. Of his non-Yiddish-contemporaries he was strongly influenced by the writings of Knut Hamsun, many of whose works he later translated, while he had a more critical attitude towards Thomas Mann, whose approach to writing he considered opposed to his own.[19] Contrary to Hamsun's approach, Singer shaped his world not only with the egos of his characters, but also using the moral commitments of the Jewish tradition that he grew up with and that his father embodies in the stories about his youth. This led to the dichotomy between the life his heroes lead and the life they feel they should lead - which gives his art a modernity his predecessors do not evince. His themes of witchcraft, mystery and legend draw on traditional sources, but they are contrasted with a modern and ironic consciousness. They are also concerned with the bizarre and the grotesque.Another important strand of his art is intra-familial strife - which he experienced firsthand when taking refuge with his mother and younger brother at his uncles home in Biłgoraj. This is the central theme in Singer's big family chronicles - like The Family Moskat (1950), The Manor (1967), and The Estate (1969). Some are reminded by them of Thomas Mann's novel Buddenbrooks; Singer had translated Mann's Der Zauberberg (The Magic Mountain) into Yiddish as a young writer.LanguageSinger always wrote and published in Yiddish – almost all of it in newspapers – and then edited his novels and stories for their American versions, which became the basis for all other translations; he referred to the English version as his "second original". This has led to an ongoing controversy whether the "real Singer" can be found in the Yiddish original, with its finely tuned language and sometimes rambling construction, or in the more tightly edited American version, where the language is usually simpler and more direct. Many of Singer's stories and novels have not yet been translated.In the short story form, in which many critics feel he made his most lasting contributions, his greatest influences were Chekhov and Maupassant. From Maupassant, Singer developed a finely grained sense of drama. Like the French master, Singer's stories can pack enormous visceral excitement in the space of a few pages. From Chekhov, Singer developed his ability to draw characters of enormous complexity and dignity in the briefest of spaces. In the foreword to his personally selected volume of his finest short stories he describes the two aforementioned writers as the greatest masters of the short story form.IllustratorsSeveral respected artists have illustrated Singer’s novels,short stories, and children’s books including Raphael Soyer, Maurice Sendak, Larry Rivers, and Irene Lieblich. Singer personally selected Lieblich to illustrate some of his books for children, including A Tale of Three Wishes and The Power of Light: Eight Stories for Hanukkah after seeing her work in an exhibition at an Artists Equity exhibit in New York. A Holocaust survivor, Lieblich was from Zamosc, Poland, a town adjacent to the area where Singer grew up. As their memories of shtetl life were so similar, Singer found Lieblich’s images ideally suited to illustrate his texts. Of her style, Singer wrote that “her works are rooted in Jewish folklore and are faithful to Jewish life and the Jewish spir it.”SummarySinger published at least 18 novels, 14 children's books, a number of memoirs, essays and articles, but is best known as a writer of short stories, which have appeared in over a dozen collections. The first collection of Singer's short stories in English, Gimpel the Fool, was published in 1957. The title story was translated by Saul Bellow and published in May 1953 in the Partisan Review. Selections from Singer's "Varshavsky-stories" in the Daily Forward were later published in anthologies such as My Father's Court (1966). Later collections include A Crown of Feathers (1973), with notable masterpieces in between, such as The Spinoza of Market Street (1961) and A Friend of Kafka(1970). His stories and novels reflect the world of the East European Jewry he grew up in. And, after his many years in America, his stories concerned the world of the immigrants and how their American dream proves elusive, sometimes even after they seemed to obtain it.Prior to winning the Nobel Prize, translations of dozens of his stories were frequently published in popular magazines such as Playboy and Esquire, which attempted to raise their literary reputation by publishing Singer, and he in turn found them to be appropriate outlets for his work.Throughout the 1960s, Singer continued to write on questions of personal morality, and was the target of scathing criticism from many quarters, some of it for not being "moral" enough, some for writing stories that no one wanted to hear. To his critics hereplied, "Literature must spring from the past, from the love of the uniform force that wrote it, and not from the uncertainty of the future."[citation needed]Singer was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1978.[1]One of his most famous novels, due to a popular movie adaptation, was Enemies, a Love Story, in which a Holocaust survivor deals with his own desires, complex family relationships, and a loss of faith. Singer's feminist story "Yentl" has had a wide impact on culture since its conversion into popular movie starring Barbra Streisand. Perhaps the most fascinating[20] Singer-inspired film is 1974's Mr. Singer's Nightmare or Mrs. Pupkos Beard by Bruce Davidson, a renowned photographer who became Singer's neighbor. This unique film is a half-hour mixture of documentary and fantasy for which Singer not only wrote the script but played the leading role.The 2007 film Love Comes Lately, starring Otto Tausig, was adapted from Singer's stories.BeliefsJudaismSinger's relationship to Judaism was complex and unconventional. He regarded himself as a skeptic and a loner, though he felt a connection to his orthodox roots. Ultimately, he developed a view of religion and philosophy, which he called "private mysticism: Since God was completely unknown and eternally silent, He could be endowed with whatever traits one elected to hang upon Him."[21][22]Singer was raised Orthodox and learned all the Jewish prayers, studied Hebrew, and learned Torah and Talmud. As he recounted in the autobiographical "In My Father's Court", he broke away from his parents in his early twenties and, influenced by his older brother, who had done the same, began spending time with non-religious Bohemian artists in Warsaw. Although he clearly believed in a monotheistic God, as in traditional Judaism, he stopped attending Jewish religious services of any kind, even on the High Holy Days. He struggled throughout his life with the feeling that a kind and compassionate God would never support the great suffering he saw around him, especially the Holocaust deaths of the Polish Jews he grew up with. In one interview with the photographer Richard Kaplan, he said, "I am angry at God because of what happened to my brother": Singer's older brother died suddenly in February 1944, in New York, of a thrombosis, his younger brother perished in Soviet Russia around 1945, after being deported with his mother and wife to Southern Kazakhstan. But his anger did not appear to become atheism. In one story his narrator tells a woman, "If you believe in God, then he exists."Despite all the complexities of his religious outlook, Singer lived in the midst of the Jewish community throughout his life. He did not seem to be comfortable unless he was surrounded by Jews; particularly Jews born in Europe. Although he spoke English, Hebrew, and Polish quite fluently, he always considered Yiddish his natural tongue, he always wrote in Yiddish and he was the last famous American author writing in this language. After he had achieved success as a writer in New York, Singer and his wife began spending time during the winters with the Jewish community in Miami. Eventually, as senior citizens, they moved to Miami and identified closely with the European Jewish community: a street was named after him long before he died. Singer was buried in a traditional Jewish ceremony in a Jewish cemetery.Especially in his short fiction, he often wrote about various Jews having religious struggles; sometimes these struggles became violent, bringing death or mental illness. In one story he meets a young woman in New York whom he knew from an Orthodox family in Poland. She has become a kind of hippie, sings American folk music with a guitar, and rejects Judaism, although the narrator comments that in many ways she seems typically Jewish. The narrator says that he often meets Jews who think they are anything but Jewish, and yet still are.In the end, Singer remains an unquestionably Jewish writer, yet his precise views about Jews, Judaism, and the Jewish God are open to interpretation. Whatever they were, they lay at the center of his literary art.VegetarianismSinger was a prominent vegetarian[23]for the last 35 years of his life and often included vegetarian themes in his works. In his short story, The Slaughterer, he described the anguish of an appointed slaughterer trying to reconcile his compassion for animals with his job of killing them. He felt that the ingestion of meat was a denial of all ideals and all religions: "How can we speak of right and justice if we take an innocent creature and shed its blood?" When asked if he had become a vegetarian for health reasons, he replied: "I did it for the health of the chickens."In The Letter Writer, he wrote "In relation to [animals], all people are Nazis; for the animals, it is an eternal Treblinka."[24]which became a classical reference in the discussions about the legitimacy of the comparison of animal exploitation with the holocaust.In the preface to Steven Rosen's "Food for Spirit: Vegetarianism and the World Religions" (1986), Singer wrote, "When a human kills an animal for food, he is neglecting his own hunger for justice. Man prays for mercy, but is unwilling to extend it to others. Why should man then expect mercy from God? It's unfair to expect something that you are not willing to give. It is inconsistent. I can never accept inconsistency or injustice. Even if it comes from God. If there would come a voicefrom God saying, "I'm against vegetarianism!" I would say, "Well, I am for it!" This is how strongly I feel in this regard."PoliticsSinger described himself as "conservative," adding that "I don't believe by flattering the masses all the time we really achieve much."[25] His conservative side was most apparent in his Yiddish writing and journalism, where he was openly hostile to Marxist sociopolitical agendas. In Forverts he once wrote, "It may seem like terrible apikorses [heresy], but conservative governments in America, England, France, have handled Jews no worse than liberal governments...The Jew's worst enemies were always those elements that the modern Jew convinced himself (really hypnotized himself) were his friends."。