曼昆-经济学原理1章

- 格式:docx

- 大小:41.32 KB

- 文档页数:12

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》第6版课后习题详解第一篇导言第1章经济学十大原理一、概念题1.稀缺性稀缺性是指在给定的时间内,相对于人的需求而言,经济资源的供给总是不足的,也就是资源的有限性与人类的欲望无限性之间的矛盾。

2.经济学经济学是研究如何将稀缺的资源有效地配置给相互竞争的用途,以使人类的欲望得到最大限度满足的科学。

其中微观经济学是以单个经济主体为研究对象,研究单个经济主体面对既定资源约束时如何进行选择的科学;宏观经济学则以整个国民经济为研究对象,主要着眼于经济总量的研究。

3.效率效率是指人们在实践活动中的产出与投入比值或者是效益与成本比值,比值大效率高,比值小效率低。

它与产出或收益大小成正比,与投入或成本成反比。

4.平等平等是指人与人的利益关系及利益关系的原则、制度、做法、行为等都合乎社会发展的需要,即经济成果在社会成员中公平分配的特性。

它是一个历史范畴,按其所产生的社会历史条件和社会性质的不同而不同,不存在永恒的公平;它也是一个客观范畴,尽管在不同的社会形态中内涵不同对其的理解不同,但都是社会存在的反映,具有客观性。

5.机会成本机会成本是指将一种资源用于某种用途,而未用于其他用途所放弃的最大预期收益。

其存在的前提条件是:①资源是稀缺的;②资源具有多种用途;③资源的投向不受限制。

6.理性人理性人是指系统而有目的地尽最大努力去实现其目标的人,是经济研究中所假设的、在一定条件下具有典型理性行为的经济活动主体。

7.边际变动边际变动是指对行动计划的微小增量调整。

8.激励激励是指引起一个人做出某种行为的某种东西。

9.市场经济市场经济是指由家庭和企业在市场上的相互交易决定资源配置的经济,而资源配置实际上就是决定社会生产什么、生产多少、如何生产以及为谁生产的过程。

10.产权产权是指个人拥有并控制稀缺资源的能力,也可以理解为人们对其所交易东西的所有权,即人们在交易活动中使自己或他人在经济利益上受益或受损的权力。

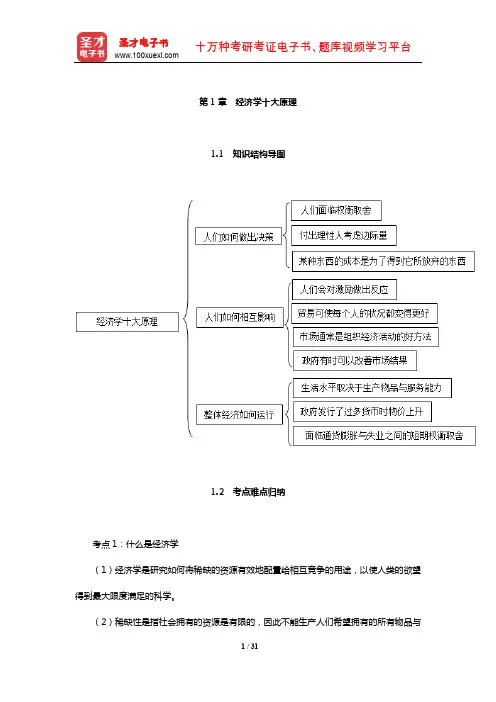

第1章经济学十大原理1.1 知识结构导图1.2 考点难点归纳考点1:什么是经济学(1)经济学是研究如何将稀缺的资源有效地配置给相互竞争的用途,以使人类的欲望得到最大限度满足的科学。

(2)稀缺性是指社会拥有的资源是有限的,因此不能生产人们希望拥有的所有物品与劳务。

现实中存在着资源的有限性和人类欲望的无限性之间的矛盾。

经济学家们从经济学角度来研究使用有限的资源来生产什么、如何生产和为谁生产的问题。

经济学研究的问题和经济物品均以稀缺性为前提。

【名师点读】经济学有两个最基本的假设:①经济个体是理性的,即理性人——系统而有目的地尽最大努力实现其目标的人;②经济资源是相对稀缺的,消费的前提是生产分配及交换,而生产的前提是有资源,资源的稀缺性决定了人必须进行选择。

深刻的理解理性人假设及资源的稀缺性是学好本门课程的关键。

考点2:经济学十大原理【名师点读】经济学的十大原理是对经济学研究的各领域的中心思想的概括,考生应理解并记住。

(1)经济个体在追求最大化目标时,其理性行为受到限制,因此经济学尤其是微观经济学十分强调约束条件下的最大化。

做出决策时,任何一种行为的成本可用其所放弃的机会衡量,理性人通过比较边际成本与边际收益作出决策,人们根据其所面临的激励改变行为。

(2)关于整体经济,考生需理解一些基本概念。

如生产率决定了不同国家和地区的生活水平,是生活水平差异的最终根源,货币量的增长是通货膨胀的最终根源,社会面临通货膨胀与失业的短期权衡取舍等。

具体内容在后续章节有具体讲到,考生需熟练掌握。

1.3 课后习题详解一、概念题1.稀缺性(scarcity)答:经济学研究的问题和经济物品都是以稀缺性为前提的。

稀缺性指在给定的时间内,相对于人的需求而言,经济资源的供给总是不足的,也就是资源的有用性与有限性。

人类消费各种物品的欲望是无限的,满足这种欲望的物品,有的可以不付出任何代价而随意取得,称之为自由物品,如阳光和空气;但绝大多数物品是不能自由取用的,因为世界上的资源(包括物质资源和人力资源)是有限的,这种有限的、为获取它必须付出某种代价的物品,称为“经济物品”。

微观经济学:第一章经济学导论1.稀缺:①指相对于人们无穷的欲望来讲,物品是希少短缺的②稀缺性:是经济物品的显著特征之一;并不意味着希少,而指不可以免费得到;要得到经济物品必须有其他经济物品交换③稀缺规律:商品普通是稀缺的,只能得到有限供应,必须通过价格或者其他形式进行分配④稀缺原因:一定时期内〔大前提〕,物品本身是有限的;利用物品进行生产的技术条件是有限的;人的生命是有限的2.选择的机会成本:资源投入某一特定用途后,所抛却的其他用途的最大利益注:理论上讲是资源改做他用的各种可能中最优的选择,但由于信息不彻底只能是其它使用中能获得的比较满意的选择3.经济学十大原理:①人们面临选择〔人们为得到一样东西,就不得不抛却另一样东西〕〔效率是社会从稀缺性资源中获得的最多的东西,平等是把这些资源的成果公平的分给社会成员〕②机会成本〔由于稀缺性,人们就要比较可供选择的方案的成本和收益〕③边际量〔人们通过比较边际利益和编辑成本而做出抉择〕④激励〔理性决策者会做出边际利益大于边际成本的决策〕⑤贸易会是每一个人的状况越来越好〔贸易可以使人们做最擅长的事〕⑥市场通常是组织经济活动的好方法〔家庭和企业→合意的市场结果;价格指引个别决策者在大多数情况下实现了整个社会福利最大化的结果〕⑦政府有时可以改善市场结果〔市场失灵时即市场本身不能进行资源配置时,政府干预经济, 可以促进效率和平等;外部性指一个人的行为对旁观者的影响〕⑧一国的生产水平取决于他的生产物品与劳务的能力〔生活水平的不同由于生产率不同〕⑨政府发行过多货币时,物价水平上升⑩社会面临通货膨胀和短期失业之间的权衡〔↓↑〕第二章需求和供给1.需求〔人们愿意购买的商品数量〕①需求表②需求曲线注:当供=需时,有均衡价格③需求定理:需求量与价格呈反向变化④影响需求的因素a 商品本身价格;相关商品价格b 消费者的收入与社会的公平程度;的偏好;的对未来的期望. 的数量与结构c 政府的消费政策⑤需求函数:需求量Qd=a –b P⑥需求的变化:商品本身价格不变,其他变化引起需求曲线的变化〔曲线的位移〕需求量的变化:商品本身价格变化, 引起需求曲线的变化〔点的挪移〕2.供给〔一定时期内,厂商愿意供给的商品量〕①供给曲线②供给定理:供给量与价格同方向变化③影响供给的因素: a 商品本身的价格;相关商品的价格b 厂商的目标;对未来的期望c 生产价格的变化;生产技术的变动 d 政府的政策④供给的变化:商品本身价格不变,其他变化引起供给曲线的变化〔曲线的位移〕〔技术引起〕供给量的变化:商品本身价格变化,引起供给曲线的变化〔点的挪移〕〔价格引起〕3.供求①均衡价格:商品的市场需求和市场供给量相等时的同一价格〔两曲线相交时〕②均衡价格的形成:供求双方在竞争中自发形成,是价格自发决定的过程〔市场机制下,供求不均衡状态会自己消失〕〔量等价不等,价等量不等〕③供求定理:供给与需求的变化引起均衡产量与均衡价格的变化,供大于求,价格下降,供不应求,价格下降4.弹性〔弹性大,即需求量对价格变化的反应程度大,则函数越倾斜,则通过降价增加产量〕①需求价格弹性:需求量对价格变化的反应程度〔涨价和降价产生的需求价格弹性不同〕②需求价格孤弹性:即P 与Q 都取平均值a E>1 富弹性:需求变化比率>价格变化比率,奢靡品,较倾斜直线〔薄利多销〕b E<1 缺乏弹性:< ,生活必需品,较陡直直线〔谷贱伤农〕c E=1 单位弹性:= ,正双曲线d E=0 无弹性垂直x〔Q〕轴的直线〔价格如何变,需求量总不变〕e E = 无穷大平行于X 轴〔价格既定,需求无限〕③影响需求弹性的因素:可替代性;重要程度;用途广泛性;可支出比例;使用时间〔必须程度越大弹性越小;消费决策中,支出比例越大弹性越大〕④互补品:两种商品互相补充共同满足一种欲望〔如:汽车和汽油〕〔价格与需求反向变化〕〔Ec<0〕⑤替代品:两种商品互相替代共同满足一种欲望〔同向变化〕〔Ec>0〕〔替代效应:一种商品的价格上升而是其替代品需求量增多〕⑥需求的收入弹性:需求量的变动对收入变动的反应程度分类:a 收入富弹性Em>1 优等品如:家电,旅游b 收入单位弹性=1 如:衣服c 缺乏弹性< 1 生活必需品d 无弹性=0 即收入变化了需求量彻底没变化如:食盐e 负弹性<1 劣等品5.价格政策:价格政策有其不完善性,短期性和无序性,所以需要政策来调整支持价格〔>均衡价格〕:支持农产品,稳定农业生产,调整农业结构;扩大农业投资. 以保障粮食安全支持价格原理知,供给过剩,措施是:收购多余粮食限制价格〔<均衡价格〕原理知,供给不足,措施是:政府实行配给制限制价格的利与弊:有利于社会平等的实现;有利于社会的安定.不利于刺激生产,产品短缺;不利于抑制需求,资源浪费;社会风尚败坏,黑市交易.宏观经济学第1 章1.①GNP 国民生产总值:指一国国民在一年内所生产的最终产品的市场价格总和〔收入概念〕GDP 国内生产总值:在某一既定时期国内生产的所有最终产品和劳务的市场价值〔生产概念〕②区别:GDP 按国土的原则,是生产概念;GNP 按国民的原则,是收入的概念③GDP 的特点:a 包括有形资产和无形资产——劳务b 按市场价格计算,不包括自产自用〔GDP 的计算受市场价格的影响〕c 仅计算本年产品价格总和,不包括以前产出〔是流量而非存量〕 d 是最终产品而非中间产品〔避免重复计算〕④GDP 的缺陷: a 不少经济活动无法计入 GDP b 反应福利水平变化存在较大局限性 ⑤GDP 的计算方法A 支出法〔产品法〕:把一年内购买所有的产品的支出加总〔住宅是投资的增加而非消费 的增加〕GDP=C 消费〔不包括建造房屋〕 +I 投资+G 政府购买〔不含转移性指出,公债利息等,如:救济金,财政补贴等〕 +X-M 〔X 出口 M 进口,净出口〕B 收入法〔供给法〕:把生产要素所得到的各种收入加起来要素报酬收入,非公司企业主收入,厂商收入 C 生产法〔部门法〕注:投资:今年卖掉去年的存货对 GDP 无影响,但消费增加;出国买香水,消费增加,进口也 增加.GDP 不变 2.总产出核算校正名义 GDP :用当年价格计算的最终产品的市场价值. 〔准确反映经济变化〕实际 GDP :用从前某一年作为基年的价格,计算的当年最终产品的市场价值. 〔假象〕 3.消费物价指数CPI :普通消费者所购买的物品与劳务的总费用的衡量标准.即在普通家庭的 支出中,购买具有代表性的一组商品,现在要比过去多花多少钱. 〔选择基年,通货膨胀率=去- 今/今〕 第 2 章经济增长率:每小时工人能生产的物品和劳务的总和Y 一 Yt 一1 〔y 为总产量,t 为时期〕作用:提高生活水品决定因素:物资资本,人力资本, 自然资源,技术知识公共政策:储蓄,投资,教育, 自由贸易,研究与开辟,产权与政治稳定,人口增长 第 3 章1.总需求曲线〔y 与 p 右下斜〕 总需求=GDP=总供给GD=消费+投资+政府购买+净出口 ① 总需求函数〔1〕a 物价水平与消费:财富效应 b 实际货币:以实物形态衡量亮的货币c 实际货币余额效应: 价格上升,人们变的相对贫困,则财富和实际收入水平降低,则消费水平 和总需求量降低 <2>物价水平与投资:利率效应:价格上升,则利率上升〔同向变化〕 ,则投资和产出〔反向 变化〕降低〔3〕与净出口:外贸效应:价格升高,则出口减少,进口增多,则净出口减少②AD 函数曲线变化: 水平挪移由于除价格以外的其他因素影响; 旋转挪移由于价格,斜率绝 对值越大表示对价格越迟钝2.①古典供给曲线〔价格与总产量之间的关系〕 〔垂直〕:位于充分就业水平上,不受价格影响垂直横轴〔最终会充分就业〕 含义:增加需求,不会增加产出,只会造成物价上升 ② 凯恩斯总供给曲线〔倒 L 型〕 〔时常不能充分就业〕经济增长率 G = t t 一1 t Y假设货币工资和物价水平不能进行调整到达最大国民收入之后,价格再怎么涨, 国名收入也不增加③常规供给曲线〔向右上方倾斜,价格降低,供给减少〕粘性工资理论:工人会对工资的下降进行反抗,因此,工资只能上升不可下降,但由于货币幻觉, 工人会反抗价格水平不变的工资下降,却不会反抗工资水平不变的价格上升④短期宏观经济目标:充分就业,稳定物价第4 章1.凯恩斯消费函数〔消费倾向〕:随着收入增加,消费也会增加;但是消费的增加不与收入增加的多.消费和收入之间的这种关系 c 消费= c <y> 收入2 线性消费函数〔随收入增加APC,MPA 减少〕:c = a 自发性消费+ b 边际消费倾向y <1 > b > o>①消费倾向:消费与收入的比例〔1〕APC 平均消费倾向= c / y , APC < 1 则消费<收入,产生储蓄〔2〕MPC 边际消费倾向=△c / △y 〔 1 > MPC > 0〕3 储蓄〔随收入的增加APS,MPA 增加〕线性储蓄函数:s 储蓄=y 收入-c 消费=y –< a + by >= -a + <1 –b >y [a >0 , 1> b>0 ](1) APS 平均储蓄倾向(2) MPS 边际储蓄倾向4 消费函数与储蓄函数的关系:互补函数由y=s+c ,同除y,则1=APS+APC , 同理1=MPS+MPC5 投资的决定〔资本的形成〕① 决定投资的经济因素:a 利率〔与投资反向变化〕b 预期利润〔同向〕c 折旧〔同〕d 预期通货膨胀率〔同〕② 投资函数〔减函数〕:投资于利率之间的关系I = I 〔r〕,I= e 自主投资–d 投资系数r 利率6 IS 方程均衡条件时I = SS=-a+<1-b>y , I=e-dr .所以–a +<1-b>y =e –dr 得出y 与r 的表达式注:r =f<y>时斜率1-b/d 表示产出对利率变化的敏感程度,越大越敏感如果某一点位处于IS 曲线右边,表示i<s,即现行的利率水平过高,从而导致投资规模小于储蓄规模.如果某一点位处于IS 曲线的左边,表示i>s,即现行的利率水平过低,从而导致投资规模大于储蓄规模.7 利率的决定利率决定于货币需求和供给,货币供给由国家货币政策控制,是外生变量,与利率无关.垂直.货币需求的三个动机:交易动机;谨慎动机;L1=ky 由收入决定投机动机L2=-rh 由利率决定8 流动性偏好:人们持有货币的偏好当利率极低时,手中无论增加多少货币,都要留在手里,不会去购买证券.此时,流动性偏好趋向于无穷大.增加货币供给,不会促使利率再下降.流动偏好陷阱:利率极低时,人们认为利率不可能再降低,或者证券价格再也不上升,而会跌落, 于是将所有证券全部换成货币.9 货币需求函数① 实际货币需求:L=L1+L2=ky - hr② 名义货币需求L=〔L1+L2〕P=<ky –hr >P加工10 货币供给:是一国在某个时点上,所有不属于政府和银行的狭义货币实际货币m=M/P11 LM 曲线〔货币市场达到均衡,即L = m 时,总产出与利率之间关系的曲线〕①推导货币市场达到均衡时m=L所以m = ky –hr 则y = <hr + m>/k斜率为k/h 的经济意义:总产出对利率变动的敏感程度.斜率越小,总产出对利率变动的反应越敏感;反之,斜率越大,总产出对利率变动的反应越迟钝.③曲线的挪移(1) 水平挪移取决于m/h12.IS,LM 分析IS 是一系列利率和收入的组合,可是产品市场均衡LM 是一系列利率和收入的组合,可是货币市场均衡使两个市场均衡则连立两个方程第5 章1 财政政策:政府变动税收和支出, 以影响总需求,从而影响就业和国民收入的政策① 包括:a 减税:留下更多可支配收入,消费增多,社会总需求增大〔则增加生产和就业〕,对货币的需求增大,利率上升,投资减少b 改变所得税结构〔高收入者增低收入者减〕:刺激总需求c 扩大政府购买多搞经济建设<增加支出>:增加消费,利率上升,投资减少d 给私人企业以津贴:增加投资,刺激需求,增加消费,利率上升②其效应:乘数效应:当扩X 性财政政策增加了收入〔在LM 上〕,从而增加了消费支出时引起的总需求的额外变动.挤出效应:扩X 性财政政策引起利率上升,从而减少了投资支出时所引起的总需求减少.LM 不变,右移IS,均衡点利率上升、国民收入增加。增加的国民收入小于不考虑LM 的收入增量.这两种情况下的国民收入增量之差,就是利率上升而引起的"挤出效应〞〔y3 –y2〕。③财政政策效果a 在LM 不变时IS 陡峭,利率变化大,IS 挪移时收入变化大,财政策效果大.IS 平整,利率变化小,IS 挪移时收入变化小,财政政策效果小. 〔用同一利率做标准〕b 在IS 不变时LM 越平整,收入变动幅度越大,扩X 的财政政策效果越大.LM 越陡峭,收入变动幅度越小,扩X 的财政政策效果越小.此时位于较高收入水平,接近充分就业.C 综上:LM 曲线越平整,IS 越陡峭,则财政政策的效果越大,货币政策效果越小.政府增加支出和减少税收的政策非常有效.如果LM 是水平的,IS 是垂直的,则财政政策完全有效,货币政策彻底无效〔凯恩斯极端〕.当利率较低而投资对利率的反应又不很灵敏时,惟独财政政策才干克服萧条,增加就业和收入,货币政策效果很小④扩 X 性财政政策:萧条时,总需求<总供给,存在失业.政府采取增加支出、减税、降低税率等措施,来刺激需求的政策.紧缩性财政政策:繁荣时,总需求>总供给,存在通货膨胀.政府采取减少开支、增税等措施,以刺激供给、抑制需求的政策2 货币政策: 货币政策通过对货币供给量的调节来调节利率,再通过利率变动来影响总需求和总供给〔〕 ① 货币政策效果:货币政策,如果能够使得利率变化较多,并且利率变化导致的投资较大变化时,货币政策效果就强. a IS 形状不变货币供给增加,LM 平整,货币政策效果小.LM 陡峭,货币政策效果大.〔LM 平整时,货币供给增加,利率下降的少,对投资和国民收入造成的影响小;反之,LM 陡峭时,货币供给增加,利率下降的多,对投资和 国民收入的影响大.〕 b LM 形状不变IS 陡峭,收入变化小,为 y1-y2. IS 平整,收入变化大,为 y1-y3. 3IS, LM 斜率对政策的影响IS 、LM 斜率对财政政策的影响:LM 斜率越大,财政越不明显.LM 斜率越小,财政政策效果越明显; IS斜率越小,财政政策效果越不明显; IS 斜率越大,财政政策效果越明显. IS 、LM 斜率对货币政策的影响IS 斜率越小,货币政策效果越明显;IS 斜率越大,货币政策效果越不明显. LM 斜率越小,货币政策效果越不明显; LM 斜率越大,货币政策效果越明显. 第 6 章1 通货膨胀〔物价全面持续的上涨〕原因: ① 货币供给过度② 需求拉动〔即总需求超过总供给而引起的价格上升〕 ③ 成本推动〔即成本提高而引起的普通价格上升〕财政政策〔IS 挪移〕 货币政策〔LM 挪移〕政策效果垂直< >IS 斜率水平<0>垂直< >LM斜率水平<0> 政策效果彻底彻底彻底彻底0 0彻底彻底大小大小挤出效应 利率2 通膨与失业的关系:失业率与通货膨胀率成反向关系第7 章1 国际贸易①政策:鼓励出口;限制进口②措施:限制进口:进口关税;进口配额;非关税壁垒〔数量限制;价格限制;国内销售限制;技术壁垒;环境壁垒〕鼓励出口:财政措施;信贷措施;倾销措施;特区措施2 汇率:一国货币折算成另一国货币的比率①汇率标价:直接标价法:以一定单位的外币为标准,标出可兑换的若干单位的本币.汇率=本币/外币=7¥/1$=7¥汇率升值=本币贬值②汇率作用a) 汇率上升,本国货币贬值,外国商品相对昂贵,本国出口增加、进口减少.b) 汇率下降,1 单位外国货币能够换取的本国货币减少,本国货币升值、商品相对昂贵,所以出口减少、进口增加.汇率与X 〔进口〕为正向关系,与M 〔出口〕为反向关系.③ 购买力平价理论〔了解〕:购买力平价:一种汇率理论,认为任何一单位通货应该能在所有国家买到等量物品.购买力平价理论是根据单一价格规律的原理得出的.根据单一价格规律,在所有地方同一种物品都应该按同样的价格出售.如果单一价格规律不正确,就可进行套利,并最终导致两个市场上不同的价格必然趋同.所以,一种通货必然在所有国家都有相同的购买力,而且汇率要调整,直到具有相同的购买力.。

第一篇导言复习题第一章宏观经济学的科学1、解释宏观经济学和微观经济学之间的差距,这两个领域如何相互关联?【答案】微观经济学研究家庭和企业如何作出决策以及这些决策在市场上的相互作用。

微观经济学的中心原理是家庭和企业的最优化——他们在目的和所面临的约束条件下可以让自己的境况更好。

而相对的,宏观经济学研究经济的整体情况,它主要关心总产出、总就业、一般物价水平和国际贸易等问题,以及这些宏观指标的波动趋势与规律。

应该看到,宏观经济学研究的这些宏观经济变量是以经济体系中千千万万个体家庭和企业之间的相互作用所构成的。

因此,微观经济决策总是构成宏观经济模型的基础,宏观经济学必然依靠微观经济基础。

2、为什么经济学家建立模型?【答案】一般来说,模型是对某些具体事物的抽象,经济模型也是如此。

经济模型可以简洁、直接地描述所要研究的经济对象的各种关系。

这样,经济学家可以依赖模型对特定的经济问题进行研究;并且,由于经济实际不可控,而模型是可控的,经济学家可以根据研究需要,合理、科学的调整模型来研究各种经济情况。

另外,经济模型一般是数学模型,而数学是全世界通用的科学语言,使用规范、标准的经济模型也有利于经济学家正确表达自己的研究意图,便于学术交流。

3、什么是市场出清模型?什么时候市场出清的假设是适用的?【答案】市场出清模型就是供给与需求可以在价格机制调整下很快达到均衡的模型。

市场出清模型的前提条件是价格是具有伸缩性的(或弹性)。

但是,我们知道价格具有伸缩性是一个很强的假设,在很多实际情况下,这个假设都是不现实的。

比如:劳动合同会使劳动力价格在一段时期内具有刚性。

因此,我们必须考虑什么情况下价格具有伸缩性是合适的。

现在一般认为,在研究长期问题时,假设价格具有伸缩性是合理的;而在研究短期问题时,最好假设价格具有刚性。

因为,从长期看,价格机制终将发挥作用,使市场供需平衡,即市场出清,而在短期,价格机制因其他因素制约,难以很快使市场出清。

第一篇导言第一章经济学十大原理复习题1�列举三个你在生活中面临的重要权衡取舍的例子。

答�①大学毕业后�面临着是否继续深造的选择�选择继续上学攻读研究生学位�就意味着在今后三年中放弃参加工作、赚工资和积累社会经验的机会�②在学习内容上也面临着很重要的权衡取舍�如果学习《经济学》�就要减少学习英语或其他专业课的时间�③对于不多的生活费的分配同样面临权衡取舍�要多买书�就要减少在吃饭、买衣服等其他方面的开支。

2�看一场电影的机会成本是什么?答�看一场电影的机会成本是在看电影的时间里做其他事情所能获得的最大收益�例如�看书、打零工。

3�水是生活必需的。

一杯水的边际利益是大还是小呢?答�这要看这杯水是在什么样的情况下喝�如果这是一个人五分钟内喝下的第五杯水�那么他的边际利益很小�有可能为负�如果这是一个极度干渴的人喝下的第一杯水�那么他的边际利益将会极大。

4�为什么决策者应该考虑激励?答�因为人们会对激励做出反应。

如果政策改变了激励�它将使人们改变自己的行为�当决策者未能考虑到行为如何由于政策的原因而变化时�他们的政策往往会产生意想不到的效果。

5�为什么各国之间的贸易不像竞赛一样有赢家和输家呢?答�因为贸易使各国可以专门从事自己最擅长的活动�并从中享有更多的各种各样的物品与劳务。

通过贸易使每个国家可供消费的物质财富增加�经济状况变得更好。

因此�各个贸易国之间既是竞争对手�又是经济合作伙伴。

在公平的贸易中是“双赢”或者“多赢”的结果。

6�市场中的那只“看不见的手”在做什么呢?答�市场中那只“看不见的手”就是商品价格�价格反映商品自身的价值和社会成本�市场中的企业和家庭在作出买卖决策时都要关注价格。

因此�他们也会不自觉地考虑自己行为的(社会)收益和成本。

从而�这只“看不见的手”指引着千百万个体决策者在大多数情况下使社会福利趋向最大化。

7�解释市场失灵的两个主要原因�并各举出一个例子。

答�市场失灵的主要原因是外部性和市场势力。

第一章经济学十大原理个人做出决策的四个原理:1) 人们面临权衡取舍(做出决策的时候人们不得不在不同的目标之间做出取舍)2) 某种东西的成本是为了得到它而放弃的东西(比如读大学,要考虑到不能工作带来的工资损失)3) 理性人考虑边际量(比如应该读到什么时候才能拿到最好的工资,博士,硕士呵呵)4) 人们会对激励做出反应(比如去超市买东西很便宜,于是我们去买,结果买了很多的不需要的东西,反倒花了更多的钱)经济相互交易的三个原理:5) 贸易能使每个人的状况更好(想想如果没有贸易,我们还处于自然经济的状况,那么我们需要做所有的事情,需要去做冰箱,彩电……不可能吧。

没有贸易就没有竞争了,那么我们就可能在某一领域被人们垄断,想想封闭的中国,我们可能不能得到很多的先进的科技,但是我们现在和很多的国家贸易,这样我们可以享用更多的先进的技术)6) 市场通常是组织经济活动的一种好方法(这个东西从我学过的邓小平理论当中可以反复地看到,无形的手,价格!)7) 政府有的时候可以改善市场结果(我们需要政府来维持这个社会的治安……,抄一句:促进效率和促进公平〈尽管很多的时候他们是一对矛盾,有的时候政府也不一定能做到这一点〉市场失灵)整体经济如何运行的三个原理:8) 一国的生活水平取决于它生产的物品与劳务的能力(就是劳动生产率,你工作一个小时,那么你能够创造出多少的财富。

那么我们要提高生活水平,我们就需要去得到良好教育,现在我就在这么做,呵呵,拥有生产工具——我现在需要一台电脑,速度要快些,屏幕要液晶的更好,以及获取最好技术的机会——这我需要向导师和图书馆,师兄多多请教了,还要自己去争取机会!)9) 当政府发行了过多的货币时,物价上升(这个好理解,不就是通货膨胀么)10)社会面临通货膨胀与失业之间的短期权衡取舍(菲利普斯曲线——增加货币的供应量,可以至少短期的失业率〈其实我还是不懂为什么?〉,但是会造成通货膨胀)第二章象经济学家一样思考第一节作为科学家的经济学家υ 为什么我们会把经济学家作为一个科学家来看待呢?经济学家同样的需要去观察世界,冷静地建立并且检验有关世界如何运行的各种理论。

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》课后习题详解(第1篇)第1篇导言第1章经济学十大原理一、概念题1.稀缺性(scarcity)答:经济学研究的问题和经济物品都是以稀缺性为前提的。

稀缺性指在给定的时间内,相对于人的需求而言,经济资源的供给总是不足的,也就是资源的有用性与有限性。

人类消费各种物品的欲望是无限的,满足这种欲望的物品,有的可以不付出任何代价而随意取得,称之为自由物品,如阳光和空气;但绝大多数物品是不能自由取用的,因为世界上的资源(包括物质资源和人力资源)是有限的,这种有限的、为获取它必须付出某种代价的物品,称为“经济物品”。

正因为稀缺性的客观存在,地球上就存在着资源的有限性和人类的欲望与需求的无限性之间的矛盾。

经济学的一个重要研究任务就是:“研究人们如何进行抉择,以便使用稀缺的或有限的生产性资源(土地、劳动、资本品如机器、技术知识)来生产各种商品,并把它们分配给不同的社会成员进行消费。

”也就是从经济学角度来研究使用有限的资源来生产什么、如何生产和为谁生产的问题。

2.经济学(economics)答:经济学是研究如何将稀缺的资源有效地配置给相互竞争的用途,以使人类的欲望得到最大限度满足的科学。

时下经常见诸国内报刊文献的“现代西方经济学”一词,大多也都在这个意义上使用。

自从凯恩斯的名著《就业、利息和货币通论》于1936年发表之后,西方经济学界对经济学的研究便分为两个部分:微观经济学与宏观经济学。

微观经济学是以单个经济主体(作为消费者的单个家庭或个人,作为生产者的单个厂商或企业,以及单个产品或生产要素市场)为研究对象,研究单个经济主体面对既定的资源约束时如何进行选择的科学。

宏观经济学则以整个国民经济为研究对象,主要着眼于对经济总量的研究。

3.效率(efficiency)答:效率指人们在实践活动中的产出与投入之比值,或者是效益与成本之比值,如果比值大,效率就高;反之,比值小,效率就低。

效率与产出或者收益的大小成正比,而与成本或投入成反比,也就是说,如果想提高效率,必须降低成本或投入,提高收益或产出。

第一章经济学十大原理一、为每个关键术语选择一个定义关键术语定义--------------稀缺性1、在社会成员中平等地分配利益的特征--------------经济学2、市场不能有效的配置资源的状况--------------效率3、有限的资源和无限的欲望--------------平等4、一个工人一小时所生产的物品与劳务量--------------理性5、市场上只有一个买者的情况--------------机会成本6、利己的市场参与者可以不知不觉的使整体社会福利最大化的原理--------------边际变动7、社会从其稀缺资源中得到最多东西的特性--------------激励8、社会和企业在市场上的相互交易决定资源配置的经济--------------市场经济9、经济活动的波动--------------产权10、当一个人的行为对旁观者有影响时的情况--------------“看不见的手”11、物价总水平的上升--------------市场失灵12、对现行计划的增量调整--------------外部性13、研究社会如何管理其稀缺资源--------------市场势力14、得到某种东西所放弃的东西--------------垄断15、一个人或一群人不适当的影响市场价格的能力--------------生产率16、某种引起人行动的东西--------------通货膨胀17、一个人拥有并使用稀缺资源的能力--------------经济周期18、为了达到目标而尽可能系统性的做到最好二、判断正误--------------1、当政府用税收和福利再分配收入时,经济变得更有效率。

-------------2、当经济学家说“天下没有免费的午餐”时,他们是指所有经济决策都涉及权衡取舍。

-------------3、亚当斯密的“看不见的手”的概念描述了公司经营如何像一只“看不见的手”伸到消费者的钱包中。

第一篇导言复习题第一章宏观经济学的科学1、解释宏观经济学与微观经济学之间的差距,这两个领域如何相互关联?【答案】微观经济学研究家庭与企业如何作出决策以及这些决策在市场上的相互作用。

微观经济学的中心原理就是家庭与企业的最优化——她们在目的与所面临的约束条件下可以让自己的境况更好。

而相对的,宏观经济学研究经济的整体情况,它主要关心总产出、总就业、一般物价水平与国际贸易等问题,以及这些宏观指标的波动趋势与规律。

应该瞧到,宏观经济学研究的这些宏观经济变量就是以经济体系中千千万万个体家庭与企业之间的相互作用所构成的。

因此,微观经济决策总就是构成宏观经济模型的基础,宏观经济学必然依靠微观经济基础。

2、为什么经济学家建立模型?【答案】一般来说,模型就是对某些具体事物的抽象,经济模型也就是如此。

经济模型可以简洁、直接地描述所要研究的经济对象的各种关系。

这样,经济学家可以依赖模型对特定的经济问题进行研究;并且,由于经济实际不可控,而模型就是可控的,经济学家可以根据研究需要,合理、科学的调整模型来研究各种经济情况。

另外,经济模型一般就是数学模型,而数学就是全世界通用的科学语言,使用规范、标准的经济模型也有利于经济学家正确表达自己的研究意图,便于学术交流。

3、什么就是市场出清模型?什么时候市场出清的假设就是适用的?【答案】市场出清模型就就是供给与需求可以在价格机制调整下很快达到均衡的模型。

市场出清模型的前提条件就是价格就是具有伸缩性的(或弹性)。

但就是,我们知道价格具有伸缩性就是一个很强的假设,在很多实际情况下,这个假设都就是不现实的。

比如:劳动合同会使劳动力价格在一段时期内具有刚性。

因此,我们必须考虑什么情况下价格具有伸缩性就是合适的。

现在一般认为,在研究长期问题时,假设价格具有伸缩性就是合理的;而在研究短期问题时, 最好假设价格具有刚性。

因为,从长期瞧,价格机制终将发挥作用,使市场供需平衡,即市场出清,而在短期,价格机制因其她因素制约,难以很快使市场出清。

第一篇导言第一章经济学十大原理复习题1.列举三个你在生活中面临的重要权衡取舍的例子。

答:①大学毕业后,面临着是否继续深造的选择,选择继续上学攻读研究生学位,就意味着在今后三年中放弃参加工作、赚工资和积累社会经验的机会;②在学习内容上也面临着很重要的权衡取舍,如果学习《经济学》,就要减少学习英语或其他专业课的时间;③对于不多的生活费的分配同样面临权衡取舍,要多买书,就要减少在吃饭、买衣服等其他方面的开支。

2.看一场电影的机会成本是什么?答:看一场电影的机会成本是在看电影的时间里做其他事情所能获得的最大收益,例如:看书、打零工。

8.为什么生产率是重要的?答:因为一国的生活水平取决于它生产物品与劳务的能力,而对这种能力的最重要的衡量度就是生产率。

生产率越高,一国生产的物品与劳务量就越多。

9.什么是通货膨胀,什么引起了通货膨胀?答:通货膨胀是流通中货币量的增加而造成的货币贬值,由此产生经济生活中价格总水平上升。

货币量增长引起了通货膨胀。

10.短期中通货膨胀与失业如何相关?答:短期中通货膨胀与失业之间存在着权衡取舍,这是由于某些价格调整缓慢造成的。

政府为了抑制通货膨胀会减少流通中的货币量,人们可用于支出的货币数量减少了,但是商品价格在短期内是粘性的,仍居高不下,于是社会消费的商品和劳务量减少,消费量减少又引起企业解雇工人。

在短期内,对通货膨胀的抑制增加了失业量。

问题与应用3.你正计划用星期六去从事业余工作,但一个朋友请你去滑雪。

去滑雪的真实成本是什么?现在假设你已计划这天在图书馆学习,这种情况下去滑雪的成本是什么?并解释之。

答:去滑雪的真实成本是周六打工所能赚到的工资,我本可以利用这段时间去工作。

如果我本计划这天在图书馆学习,那么去滑雪的成本是在这段时间里我可以获得的知识。

5.你管理的公司在开发一种新产品过程中已经投资500万美元,但开发工作还远远没有完成。

在最近的一次会议上,你的销售人员报告说,竞争性产品的进入使你们新产品的预期销售额减少为300万美元。

1 - Ten Principles of EconomicsThe word economy comes from the Greek word for “one who manages a household.”At first, this origin might seem peculiar. But, in fact, households and economies have much in common.A household faces many decisions. It must decide which members of the household do which tasks and what each member gets in return: Who cooks dinner?Who does the laundry? Who gets the extra dessert at dinner? Who gets to choose what TV show to watch? In short, the household must allocate its scarce resources among its various members, taking into account each member’s abilities, efforts, and desires.Like a household, a society faces many decisions. A society must decide what jobs will be done and who will do them. It needs some people to grow food, other people to make clothing, and still others to design computer software. Once society has allocated people (as well as land, buildings, and machines) to various jobs, it must also allocate the output of goods and services that they produce. It must decide who will eat caviar and who will eat potatoes. It must decide who will drive a Porsche and who will take the bus.The management of society’s resources is important because resources are scarce. Scarcity means that society has limited resources and therefore cannot produce all the goods and services people wish to have. Just as a household cannot give every member everything he or she wants, a society cannot give every individual the highest standard of living to which he or she might aspire.Economics is the study of how society manages its scarce resources. In most societies, resources are allocated not by a single central planner but through the combined actions of millions of households and firms. Economists therefore study how people make decisions: how much they work, what they buy, how much they save, and how they invest their savings. Economists also study how people interact with one another. For instance, they examine how the multitude of buyers and sellers of a good together determine the price at which the good is sold and the quantity that is sold. Finally, economists analyze forces and trends that affect the economy as a whole, including the growth in average income, the fraction of the population that cannot find work, and the rate at which prices are rising. Although the study of economics has many facets, the field is unified by several central ideas.In the rest of this chapter, we look at Ten Principles of Economics. These principles recur throughout this book and are introduced here to give you an overview of what economics is all about. You can think of this chapter as a “preview of coming attractions.”HOW PEOPLE MAKE DECISIONSThere is no mystery to what an “economy” is. Whether we are talking about the economyof Los Angeles, of the United States, or of the whole world, an economy is just a group of people interacting with one another as they go about their lives.Because the behavior of an economy reflects the behavior of the individuals who make up the economy, we start our study of economics with four principles of individual decisionmaking.PRINCIPLE #1: PEOPLE FACE TRADEOFFSThe first lesson about making decisions is summarized in the adage: “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” To get one thing that we like, we usually have to give up another thing that we like. Making decisions requires trading off one goal against another.Consider a student who must decide how to allocate her most valuable resource— her time. She can spend all of her time studying economics; she can spend all of her time studying psychology; or she can divide her time between the two fields. For every hour she studies one subject, she gives up an hour she could have used studying the other. And for every hour she spends studying, she gives up an hour that she could have spent napping, bike riding, watching TV, or working at her part-time job for some extra spending money.Or consider parents deciding how to spend their family income. They can buy food, clothing, or a family vacation. Or they can save some of the family income for retirement or the children’s college education. When they choose to spend an extra dollar on one of these goods, they have one less dollar to spend on some other good.When people are grouped into societies, they face different kinds of tradeoffs. The classic tradeoff is between “guns and butter.” The more we spend on national defense to protect our shores from foreign aggressors (guns), the less we can spend on consumer goods to raise our standard of living at home (butter). Also important in modern society is the tradeoff between a clean environment and a high level of income. Laws that require firms to reduce pollution raise the cost of producing goods and services. Because of the higher costs, these firms end up earning smaller profits, paying lower wages, charging higher prices, or some combination of these three. Thus, while pollution regulations give us the benefit of a cleaner environment and the improved health that comes with it, they have the cost of reducing the incomes of the firms’ owners, workers, and customers.Another tradeoff society faces is between efficiency and equity. Efficiency means that society is getting the most it can from its scarce resources. Equity means that the benefits of those resources are distributed fairly among society’s members. In other words, efficiency refers to the size of the economic pie, and equity refers to how the pie is divided. Often, when government policies are being designed, these two goals conflict.Consider, for instance, policies aimed at achieving a more equal distribution of economic well-being. Some of these policies, such as the welfare system or unemployment insurance, try to help those members of society who are most in need. Others, such as the individual income tax, ask the financially successful to contribute more than others to support the government. Although these policies have the benefit of achieving greater equity, they have a cost in terms of reduced efficiency.When the government redistributes income from the rich to the poor, it reduces the reward for working hard; as a result,people work less and produce fewer goods and services. In other words, when the government tries to cut the economic pie into more equal slices, the pie gets smaller.Recognizing that people face tradeoffs does not by itself tell us what decisions they will or should make. A student should not abandon the study of psychology just because doing so would increase the time available for the study of economics. Society should not stop protecting the environment just because environmental regulations reduce our material standard of living. The poor should not be ignored just because helping them distorts work incentives. Nonetheless, acknowledging life’s tradeoffs is important because people are likely to make good decisions only if they understand the options that they have available.PRINCIPLE #2: THE COST OF SOMETHING ISWHAT YOU GIVE UP TO GET ITBecause people face tradeoffs, making decisions requires comparing the costs and benefits of alternative courses of action. In many cases, however, the cost of some action is not as obvious as it might first appear.Consider, for example, the decision whether to go to college. The benefit is intellectual enrichment and a lifetime of better job opportunities. But what is the cost? To answer this question, you might be tempted to add up the money you spend on tuition, books, room, and board. Yet this total does not truly represent what you give up to spend a year in college.The first problem with this answer is that it includes some things that are not really costs of going to college. Even if you quit school, you would need a place to sleep and food to eat. Room and board are costs of going to college only to the extent that they are more expensive at college than elsewhere. Indeed, the cost of room and board at your school might be less than the rent and food expenses that you would pay living on your own. In this case, the savings on room and board are a benefit of going to college.The second problem with this calculation of costs is that it ignores the largest cost of going to college—your time. When you spend a year listening to lectures,reading textbooks, and writing papers, you cannot spend that time working at a job. For most students, the wages given up to attend school are the largest single cost of their education.The opportunity cost of an item is what you give up to get that item. When making any decision, such as whether to attend college, decisionmakers should be aware of the opportunity costs that accompany each possible action. In fact, they usually are. College-age athletes who can earn millions if they drop out of school and play professional sports are well aware that their opportunity cost of college is very high. It is not surprising that they often decide that the benefit is not worth the cost.PRINCIPLE #3: RATIONAL PEOPLE THINK AT THE MARGINDecisions in life are rarely black and white but usually involve shades of gray. When it’s time for dinner, the decision you face is not between fasting or eating like a pig, but whether to take that extra spoonful of mashed potatoes. When exams roll around, your decision is not between blowing them off or studying 24 hours a day, but whether to spend an extra hour reviewing your notes instead of watching TV. Economists use the term marginal changes to describe small incremental adjustments to an existing planof action. Keep in mind that “margin” means “edge,” so marginal changes are adjustments around the edges of what you are doing.In many situations, people make the best decisions by thinking at the margin.Suppose, for instance, that you asked a friend for advice about how many years to stay in school. If he were to compare for you the lifestyle of a person with a Ph.D. to that of a grade school dropout, you might complain that this comparison is not helpful for your decision. You have some education already and most likely are deciding whether to spend an extra year or two in school. To make this decision, you need to know the additional benefits that an extra year in school would offer (higher wages throughout life and the sheer joy of learning) and the additional costs that you would incur (tuition and the forgone wages while you’re in school).By comparing these marginal benefits and marginal costs, you can evaluate whether the extra year is worthwhile. As another example, consider an airline deciding how much to charge passengers who fly standby. Suppose that flying a 200-seat plane across the country costs the airline $100,000. In this case, the average cost of each seat is $100,000/200, which is $500. One might be tempted to conclude that the airline should never sell a ticket for less than $500. In fact, however, the airline can raise its profits by thinking at the margin. Imagine that a plane is about to take off with ten empty seats, and a standby passenger is waiting at the gate willing to pay $300 for a seat.Should the airline sell it to him? Of course it should. If the plane has empty seats, the cost of adding one more passenger is minuscule. Although the average cost of flying a passenger is $500, the marginal cost is merely the cost of the bag of peanuts and can of soda that the extra passenger will consume. As long as the standby passenger pays more than the marginal cost, selling him a ticket is profitable.As these examples show, individuals and firms can make better decisions by thinking at the margin. A rational decisionmaker takes an action if and only if the marginal benefit of the action exceeds the marginal cost.PRINCIPLE #4: PEOPLE RESPOND TO INCENTIVESBecause people make decisions by comparing costs and benefits, their behavior may change when the costs or benefits change. That is, people respond to incentives.When the price of an apple rises, for instance, people decide to eat more pears and fewer apples, because the cost of buying an apple is higher. At the same time, apple orchards decide to hire more workers and harvest more apples, because the benefit of selling an apple is also higher. As we will see, the effect of price on the behavior of buyers and sellers in a market—in this case, the market for apples—is crucial for understanding how the economy works.Public policymakers should never forget about incentives, for many policies change the costs or benefits that people face and, therefore, alter behavior. Atax on gasoline, for instance, encourages people to drive smaller, more fuel-efficient cars.It also encourages people to take public transportation rather than drive and to live closer to where they work. If the tax were large enough, people would start driving electric cars.When policymakers fail to consider how their policies affect incentives, theycan end up with results that they did not intend. For example, consider public policyregarding auto safety. Today all cars have seat belts, but that was not true 40 years ago. In the late 1960s, Ralph Nader’s book Unsafe at Any Speed generated much public concern over auto safety. Congress responded with laws requiring car companies to make various safety features, including seat belts, standard equipment on all new cars.How does a seat belt law affect auto safety? The direct effect is obvious. With seat belts in all cars, more people wear seat belts, and the probability of surviving a major auto accident rises. In this sense, seat belts save lives. But that’s not the end of the story. To fully understand the effects of this law, we must recognize that people change their behavior in response to the incentives they face. The relevant behavior here is the speed and care with which drivers operate their cars. Driving slowly and carefully is costly because it uses the driver’s time and energy. When deciding how safely to drive, rational people compare the marginal benefit from safer driving to the marginal cost. They drive more slowly and carefully when the benefit of increased safety is high. This explains why people drive more slowly and carefully when roads are icy than when roads are clear.Now consider how a seat belt law alters the cost–benefit calculation of a rational driver. Seat belts make accidents less costly for a driver because they reduce the probability of injury or death. Thus, a seat belt law reduces the benefits to slow and careful driving. People respond to seat belts as they would to an improvement in road conditions—by faster and less careful driving. The end result of a seat belt law, therefore, is a larger number of accidents.How does the law affect the number of deaths from driving? Drivers who wear their seat belts are more likely to survive any given accident, but they are also more likely to find themselves in an accident. The net effect is ambiguous. Moreover, the reduction in safe driving has an adverse impact on pedestrians (and on drivers who do not wear their seat belts). They are put in jeopardy by the law because they are more likely to find themselves in an accident but are not protected by a seat belt. Thus, a seat belt law tends to increase the number of pedestrian deaths.At first, this discussion of incentives and seat belts might seem like idle speculation.Yet, in a 1975 study, economist Sam Peltzman showed that the auto-safety laws have, in fact, had many of these effects. According to Peltzman’s evidence, these laws produce both fewer deaths per accident and more accidents. The net result is little change in the number of driver deaths and an increase in the number of pedestrian deaths.Peltzman’s analysis of auto safety is an example of the general principle that people respond to incentives. Many incentives that economists study are more straightforward than those of the auto-safety laws. No one is surprised that people drive smaller cars in Europe, where gasoline taxes are high, than in the United States, where gasoline taxes are low. Yet, as the seat belt example shows, policies can have effects that are not obvious in advance. When analyzing any policy, we must consider not only the direct effects but also the indirect effects that work through incentives. If the policy changes incentives, it will cause people to alter their behavior.QUICK QUIZ: List and briefly explain the four principles of individualdecisionmaking.HOW PEOPLE INTERACTThe first four principles discussed how individuals make decisions. As we go about our lives, many of our decisions affect not only ourselves but other people as well. The next three principles concern how people interact with one another.PRINCIPLE #5: TRADE CAN MAKE EVERYONE BETTER OFFYou have probably heard on the news that the Japanese are our competitors in the world economy. In some ways, this is true, for American and Japanese firms do produce many of the same goods. Ford and Toyota compete for the same customers in the market for automobiles. Compaq and Toshiba compete for the same customers in the market for personal computers.Yet it is easy to be misled when thinking about competition among countries.Trade between the United States and Japan is not like a sports contest, where one side wins and the other side loses. In fact, the opposite is true: Trade between two countries can make each country better off.To see why, consider how trade affects your family. When a member of your family looks for a job, he or she competes against members of other families who are looking for jobs. Families also compete against one another when they go shopping, because each family wants to buy the best goods at the lowest prices. So, in a sense, each family in the economy is competing with all other families.Despite this competition, your family would not be better off isolating itself from all other families. If it did, your family would need to grow its own food, make its own clothes, and build its own home. Clearly, your family gains much from its ability to trade with others. Trade allows each person to specialize in the activities he or she does best, whether it is farming, sewing, or home building. By trading with others, people can buy a greater variety of goods and services at lower cost.Countries as well as families benefit from the ability to trade with one another.Trade allows countries to specialize in what they do best and to enjoy a greater variety of goods and services. The Japanese, as well as the French and the Egyptians and the Brazilians, are as much our partners in the world economy as they are our competitors.PRINCIPLE #6: MARKETS ARE USUALLY A GOOD WAYTO ORGANIZE ECONOMIC ACTIVITYThe collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe may be the most important change in the world during the past half century. Communist countries worked on the premise that central planners in the government were in the best position to guide economic activity. These planners decided what goods and services were produced, how much was produced, and who produced and consumed these goods and services. The theory behind central planning was that only the government could organize economic activity in a way that promoted economic well-being for the country as a whole.Today, most countries that once had centrally planned economies have abandoned this system and are trying to develop market economies. In a market economy, the decisions of a central planner are replaced by the decisions of millions of firms and households. Firms decide whom to hire and what to make. Households decide which firms to work forand what to buy with their incomes. These firms and households interact in the marketplace, where prices and self-interest guide their decisions.At first glance, the success of market economies is puzzling. After all, in a market economy, no one is looking out for the economic well-being of society as a whole. Free markets contain many buyers and sellers of numerous goods and services, and all of them are interested primarily in their own well-being. Yet, despite decentralized decisionmaking and self-interested decisionmakers, market economies have proven remarkably successful in organizing economic activity in a way that promotes overall economic well-being.In his 1776 book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, economist Adam Smith made the most famous observation in all of economics: Households and firms interacting in markets act as if they are guided by an “invisible hand” that leads them to desirable market outcomes. One of our goals in<The collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe may be the most important change in the world during the past half century. Communist countries worked on the premise that central planners in the government were in the best position to guide economic activity. These planners decided what goods and services were produced, how much was produced, and who produced and consumed these goods and services. The theory behind central planning was that only the government could organize economic activity in a way that promoted economic well-being for the country as a whole.Today, most countries that once had centrally planned economies have abandoned this system and are trying to develop market economies. In a market economy, the decisions of a central planner are replaced by the decisions of millions of firms and households. Firms decide whom to hire and what to make. Households decide which firms to work for and what to buy with their incomes. These firms and households interact in the marketplace, where prices and self-interest guide their decisions.At first glance, the success of market economies is puzzling. After all, in a market economy, no one is looking out for the economic well-being of society as a whole. Free markets contain many buyers and sellers of numerous goods and services, and all of them are interested primarily in their own well-being. Yet, despite decentralized decisionmaking and self-interested decisionmakers, market economies have proven remarkably successful in organizing economic activity in a way that promotes overall economic well-being.In his 1776 book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, economist Adam Smith made the most famous observation in all of economics: Households and firms interacting in markets act as if they are guided by an “invisible hand” that leads them to desirable market outcomes. One of our goals in the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. . . .Every individual . . . neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. . . . He intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectuallythan when he really intends to promote it.Smith is saying that participants in the economy are motivated by self-interest and that the “invisible hand” of the marketplace guides this self-interest into promoting general economic well-being.Many of Smith’s insights remain at the center of modern economics. Our analysis in the coming chapters will allow us to express Smith’s conclusions more precisely and to analyze fully the strengths and weaknesses of the market’s invisible hand.>this book is to understand how this invisible hand works its magic. As you study economics, you will learn that prices are the instrument with which the invisible hand directs economic activity. Prices reflect both the value of a good to society and the cost to society of making the good. Because households and firms look at prices when deciding what to buy and sell, they unknowingly take into account the social benefits and costs of their actions. As a result, prices guide these individual decisionmakers to reach outcomes that, in many cases, maximize the welfare of society as a whole.There is an important corollary to the skill of the invisible hand in guiding economic activity: When the government prevents prices from adjusting naturally to supply and demand, it impedes the invisible hand’s ability to coordinate the millions of households and firms that make up the economy. This corollary explains why taxes adversely affect the allocation of resources: Taxes distort prices and thus the decisions of households and firms. It also explains the even greater harm caused by policies that directly control prices, such as rent control. And it explains the failure of communism. In communist countries, prices were not determined in the marketplace but were dictated by central planners. These planners lacked the information that gets reflected in prices when prices are free to respond to market forces. Central planners failed because they tried to run the economy with one hand tied behind their backs—the invisible hand of the marketplace.PRINCIPLE #7: GOVERNMENTS CAN SOMETIMESIMPROVE MARKET OUTCOMESAlthough markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity, this rule has some important exceptions. There are two broad reasons for a government to intervene in the economy: to promote efficiency and to promote equity. That is, most policies aim either to enlarge the economic pie or to change how the pie is divided.The invisible hand usually leads markets to allocate resources efficiently. Nonetheless, for various reasons, the invisible hand sometimes does not work.Economists use the term market failure to refer to a situation in which the market on its own fails to allocate resources efficiently.One possible cause of market failure is an externality. An externality is the impact of one person’s actions on the well-being of a bystander. The classic example of an external cost is pollution. If a chemical factory does not bear the entire cost of the smoke it emits, it will likely emit too much. Here, the government can raise economic well-being through environmental regulation. The classic example of an external benefit is the creation of knowledge. When a scientist makes an important discovery, he produces a valuable resource that other people can use. In this case, the government can raiseeconomic well-being by subsidizing basic research, as in fact it does. Another possible cause of market failure is market power. Market power refers to the ability of a single person (or small group of people) to unduly influence market prices. For example, suppose that everyone in town needs water but there is only one well. The owner of the well has market power—in this case a monopoly—over the sale of water. The well owner is not subject to the rigorous competition with which the invisible hand normally keeps self-interest in check.You will learn that, in this case, regulating the price that the monopolist charges can potentially enhance economic efficiency.The invisible hand is even less able to ensure that economic prosperity is distributedfairly. Amarket economy rewards people according to their ability to produce things that other people are willing to pay for. The world’s best basketball player earns more than the world’s best chess player simply because people are willing to pay more to watch basketball than chess. The invisible hand does not ensure that everyone has sufficient food, decent clothing, and adequate health care. A goal of many public policies, such as the income tax and the welfare system, is to achieve a more equitable distribution of economic well-being.To say that the government can improve on markets outcomes at times does not mean that it always will. Public policy is made not by angels but by a political process that is far from perfect. Sometimes policies are designed simply to reward the politically powerful. Sometimes they are made by well-intentioned leaders who are not fully informed. One goal of the study of economics is to help you judge when a government policy is justifiable to promote efficiency or equity and when it is not.QUICK QUIZ: List and briefly explain the three principles concerningeconomic interactions.HOW THE ECONOMY AS A WHOLE WORKSWe started by discussing how individuals make decisions and then looked at how people interact with one another. All these decisions and interactions together make up “the economy.” The last three principles concern the workings of the economy as a whole.PRINCIPLE #8: A COUNTRY’S STANDARD OFLIVING DEPENDS ON ITS ABILITY TOPRODUCE GOODS AND SERVICESThe differences in living standards around the world are staggering. In 1997 the average American had an income of about $29,000. In the same year, the average Mexican earned $8,000, and the average Nigerian earned $900. Not surprisingly, this large variation in average income is reflected in various measures of the quality of life. Citizens of high-income countries have more TV sets, more cars, better nutrition, better health care, and longer life expectancy than citizens of low-income countries.Changes in living standards over time are also large. In the United States, incomes have historically grown about 2 percent per year (after adjusting for changes in the cost of living). At this rate, average income doubles every 35 years.。