北京林业大学研究生学位论文模板

- 格式:docx

- 大小:55.32 KB

- 文档页数:10

2018年北京林业⼤学硕⼠论⽂格式模板分类号UDC密级硕⼠专业学位论⽂基于⼈⼯智能的快论⽂排版系统研究Research on Kuai65 Typesetting SystemBased on Artificial Intelligence快论⽂指导教师***教授***教授申请学位级别⼯学硕⼠研究⽅向⼈⼯智能论⽂提交⽇期2017年4⽉论⽂答辩⽇期2017年6⽉学位授予⽇期2017年6⽉答辩委员会主席:评阅⼈:北京林业⼤学独创性声明本⼈声明所呈交的论⽂是我个⼈在导师指导下进⾏的研究⼯作及取得的研究成果。

尽我所知,除了⽂中特别加以标注和致谢的地⽅外,论⽂中不包含其它⼈已经发表或撰写过的研究成果,也不包含为获得北京林业⼤学或其它教育机构的学位或证书⽽使⽤过的材料。

与我⼀同⼯作的同志对本研究所做的任何贡献均已在论⽂中作了明确的说明并表⽰了谢意。

签名:⽇期:关于论⽂使⽤授权的说明本⼈完全了解北京林业⼤学有关保留、使⽤学位论⽂的规定,即:学校有权保留送交论⽂的复印件,允许论⽂被查阅和借阅;学校可以公布论⽂的全部或部分内容,可以采⽤影印、缩印或其它复制⼿段保存论⽂。

(保密的论⽂在解密后应遵守此规定)签名:导师签名:、⽇期:摘要摘要快论⽂(/doc/4e7206236.html)是⼀款专业的毕业论⽂在线排版系统,上传论⽂草稿,选定学校模板,点击⼀键排版,只需⼏分钟就可完成论⽂排版,免费下载预览,满意后付款。

快论⽂平台现已汇集了全国617所⾼校权威毕业论⽂模板,均源⾃各校官⽅最新发布的毕业论⽂撰写规范,基本涵盖了各类⾼校毕业论⽂格式要求。

据统计,毕业论⽂排版涉及的⼏⼗项格式设置中,80%的操作都属于不常⽤操作,因此绝⼤多数同学以前没⽤过,以后⽤到的概率也很低,但为了达到排版的规范,却需要花费⼤量的时间去解读论⽂撰写规范和学习这些不常⽤的word操作。

⾯对复杂的格式规范,⼤多数同学熬夜反复调整修改却还是存在各种各样的问题。

硕士研究生学位论文题录、摘要的格式规定一、硕士学位论文题录(一)编写格式硕士学位论文中文题目= 硕士学位论文英文题目[硕士学位论文,中]/硕士生姓名(北京林业大学所在学院全称),导师导师姓名(空一个字符)//毕业年//资助项目名称文字要求:中文字体:宋体;外文字体:Times New Roman。

字号:5号段落要求:1.25倍行距。

(二)编写示例中国竹节虫异科四属成虫分类及部分卵的初步研究= A Taxonomic Study on the Adults and Eggs in Four Genera of Heteronemiidae in China[硕士学位论文,中]/徐进(北京林业大学资源与环境学院),导师武三安、陈树椿∥2006林业电子政务系统管理决策分析数据环境建立研究= The Research of Building Data Environment for Decision Analysis in Forestry E-Government[硕士学位论文,中]/张庆文(北京林业大学经济管理学院),导师王武魁//2006//北京林业大学研究生自选课题基金资助项目区域生态系统健康监测研究——以八仙山自然保护区为例= The Research on Ecosystem Health Monitoring in A Region——Take Baxian Mountain Nature Reserve as A Case[硕士学位论文,中]/池建(北京林业大学资源与环境学院),导师邓华锋//2006//国家“十五”科技攻关项目、国防科技工业民用专项项目(三)其他1、在硕士学位论文中文题目以及英文题目中,对于物理量的符号、生物学中的基因缩写词、属以下(含属)的拉丁学名(属名(第一个字母大写)、种名(全小写))等用斜体;此外,凡是硕士英文题目中的实词,第一个字母应大写;2、当硕士指导教师为两个或两个以上时,导师与导师姓名之间应用顿号隔开;3、对于基金项目只注明资助该研究的项目名称,不标项目编号;而且项目名称必须完整、规范(对于北京市和国家级科研项目名称可参照附件);当资助项目为两个或两个以上时,项目与项目之间用顿号隔开。

北林毕业论文北林毕业论文北林是北京林业大学的简称,北林位于北京市海淀区,是一所以林学为主的综合性大学。

北林的发展离不开改革开放的大潮,离不开社会主义现代化事业的热潮,离不开改革开放的正确方向。

本论文将从北林的历史沿革、学科建设、师资队伍和科研成果等方面进行探讨。

首先,北林作为北京市海淀区的一所高等院校,其历史可追溯到1949年。

北林的前身是创办于1949年的中国林业总局干部进修学校,后来经过多次改革和发展,于1985年更名为北京林业大学。

北林在创办初期主要以培养林业干部为主,后来逐渐发展成为一所以林学为主的综合性大学。

北林的发展离不开改革开放的大潮,离不开社会主义现代化事业的热潮,离不开改革开放的正确方向。

北林在过去几十年的发展中,为国家培养了大批优秀的人才,为林业事业的发展做出了重要贡献。

其次,北林的学科建设是北林发展的重要支撑。

北林目前拥有林学、园林学、木材科学与工程、环境科学与工程、生物技术、野生动物与自然保护区管理等多个学科专业。

其中,林学是北林的特色学科。

北林的林学学科在国内处于领先水平,具有较大的影响力和较高的学术地位。

北林在学科建设中注重理论与实践相结合,注重培养学生的动手能力和创新能力,为国家培养了大批合格的林业人才。

再次,北林的师资队伍是北林发展的重要力量。

北林拥有一支素质较高的教师队伍,教师队伍中既有具有较高学术造诣的专家学者,又有具有丰富实践经验的专业技术人员。

教师队伍中有国家级教学团队、国家级教学名师、国家级优秀教师等一批优秀的教师。

教师们不仅具有良好的教学能力,还积极参与科学研究,取得了一系列重要的科研成果。

最后,北林的科研成果是北林发展的重要标志。

北林在科学研究方面非常重视基础研究和应用研究的结合,注重科技成果的转化和产业化。

北林的科研实力在国内处于领先地位,取得了一系列的重要科研成果。

这些科研成果不仅为学校的发展提供了强大的科技支撑,还对国家的林业事业做出了重要贡献。

北京林业大学本科毕业论文(设计)撰写规范(试行)毕业论文(设计)是培养学生综合运用本学科的基本理论、专业知识和基本技能,提高分析和解决实际问题的能力,完成初步培养从事科学研究工作和专业工程技术或实务工作基本训练的重要环节。

为了统一和规范我校本科毕业论文(设计)的写作,保证毕业论文(设计)的质量,根据《中华人民共和国国家标准科学技术报告、学位论文和学术论文的编写格式》(国家标准GB7713-87)的规定,特制定本规范。

1 内容要求1.1 论文题目论文题目应该简短、明确、有概括性。

读者通过题目,能大致了解论文的内容、专业的特点和学科的范畴。

但字数要适当,一般不宜超过24个汉字。

必要时可加副标题。

论文题目应有中文和英文两种形式。

1.2 作者及指导教师包括作者的姓名,所属专业、年级及班级,指导教师的姓名。

应有中文及英文两种形式。

1.3 摘要与关键词1.3.1 论文摘要论文摘要应概括地反映出毕业论文(设计)的目的、内容、方法、成果和结论。

摘要中不宜使用公式、图表,不标注引用文献编号。

摘要以300~500字为宜。

1.3.2 关键词关键词是供检索用的主题词条,应采用能覆盖论文主要内容的通用技术词条(参照相应的技术术语标准)。

关键词一般为3~5个,按词条的外延层次排列(外延大的排在前面)。

1.4 目录目录按章、节、条三级标题编写,要求标题层次清晰。

目录中的标题要与正文中标题一致。

目录中应包括绪论、论文主体、结论、致谢、参考文献、附录等。

1.5 论文正文论文正文是毕业论文(设计)的主体和核心部分,一般应包括绪论、论文主体及结论等部分。

1.5.1 绪论绪论一般作为第一章,是毕业论文(设计)主体的开端。

绪论应包括:毕业设计的背景及目的;国内外研究状况和相关领域中已有的研究成果;课题的研究方法;论文构成及研究内容等。

绪论一般不少于2千字。

1.5.2 论文主体论文主体是毕业论文(设计)的主要部分,应该结构合理,层次清楚,重点突出,文字简练、通顺。

硕士学位论文格式模版范文简洁大气目录一、摘要 (2)1. 研究背景与意义 (2)2. 研究方法与数据来源 (3)3. 研究结果与讨论 (4)4. 结论与创新点 (5)二、内容描述 (5)1. 研究问题阐述 (6)2. 研究目的与意义 (7)3. 文献综述 (7)4. 研究范围与限制 (8)三、理论框架与研究假设 (9)1. 理论框架构建 (10)2. 研究假设提出 (11)3. 研究假设验证 (12)四、研究方法 (13)1. 数据收集方法 (14)2. 数据分析方法 (15)3. 研究的可靠性与有效性 (16)五、实证分析 (17)1. 描述性统计分析 (18)2. 假设检验 (18)3. 因子分析 (19)4. 回归分析 (20)六、结论与政策建议 (20)1. 研究结论概述 (22)2. 政策建议 (22)3. 研究局限与未来展望 (23)一、摘要本硕士学位论文旨在探讨[研究主题或领域],研究内容主要围绕[主要研究方向或重点]展开。

本文首先概述了研究背景、目的、意义以及研究问题,接着详细介绍了研究方法、数据来源以及实验设计。

本研究通过[研究方法或技术]的应用,成功在[特定情境或案例中]取得重要发现。

论文通过实证分析揭示了关于[重要研究成果或发现点]的新见解,这些发现不仅丰富了现有的理论体系,也为后续研究提供了有价值的参考。

本研究还对实践领域产生了积极影响,有助于解决实际问题。

摘要简洁明了地概括了本研究的主要内容和成果,突出了论文的创新点和重要性。

1. 研究背景与意义随着信息技术的迅猛发展,大数据时代已然到来。

海量数据的积累为各行各业带来了前所未有的机遇与挑战,在此背景下,本论文聚焦于[具体研究领域],旨在深入探究[研究主题],以期为[相关领域或行业]的发展提供有力支持。

[相关领域]在国民经济和社会发展中的地位日益凸显。

伴随着数据增长的是数据质量的参差不齐和安全隐患,如何有效地挖掘出有价值的信息,同时确保数据的真实性和可靠性,成为了亟待解决的问题。

分类号 U D C 密 级 编 号

硕士学位论文

动中通天线伺服控制系统研究

Research on the COTM antenna servo control system

2015年4月

学位申请人:

杜换云 指导教师: 丁喆 教授 一级学科:

控制理论与控制工程 二级学科:

控制工程 学位类别:

工学硕士

分类号U D C

密级编号

专业硕士/

中文题目(小二号宋体、一般不超过25字)

独创性声明

本人声明,所呈交的论文是我个人在导师指导下完成的研究工作及取得的研究成果。

据我所知,文中除了特别加以标注和致谢的地方外,不包含其他人已经发表或撰写过的研究成果,也不包含为获得河南科技大学或其它教育机构的其他学位或证书而使用过的材料。

与我一同工作的同志对本研究所做的任何贡献均已在论文中作了明确的说明并表示了谢意。

研究生签名:

日期:

关于论文使用授权的说明

本人完全了解河南科技大学有关保留、使用学位论文的规定,即:学校拥有对所有学位论文的复制权、传播权、汇编权及其它使用权(特殊情况需要保密的论文应提前说明,但在解密后应遵守此规定)。

需要保密的论文请填写:本学位论文在年月至年月期间需要保密,解密后适用本授权书。

(需要保密的学位论文无须向图书馆提供论文的电子文档)

研究生签名:导师签名:

日期:。

论人工克隆灭绝物种张雨生(北京林业大学园林学院园林12-1 120314101)摘要:科技的发展使得灭绝动物复活成为可能。

随着克隆技术进化至今,确立了获取DNA信息的新手法。

只要能从所保存下来的个体或组织中提取较为完整的DNA,制作出具有遗传特性的类似动物并不是什么难事。

“最主要的问题是,已灭绝动物的基因组序列可能现存较少或大多呈‘碎片状’。

关键词:克隆;灭绝动物;复活;技术;伦理Author1 Zhang Yusheng英文题目Cloning extinct species.Journal of Beijing Forestry University [Ch,×30 ref.]1 College of Landscape gardening , Beijing Forestry University, 100083, P.R. China;2 ……英文摘要:The development of science and technology makes possible the extinction of animal life. With the development of cloning technology evolution so far, established a new way to obtain DNA information. As long as the extraction of DNA from individuals or organizations are preserved, produce has the genetic characteristics of similar animal is not difficult. "The main problem is, genome sequence of extinct animal may present less or mostly 'piecemeal'.Key words cloning;extinc species;relive;technology;ethic1 人工克隆1.1概念所谓人工克隆通常是指一种在人工诱导下的无性生殖方式或自然的无性生殖方式。

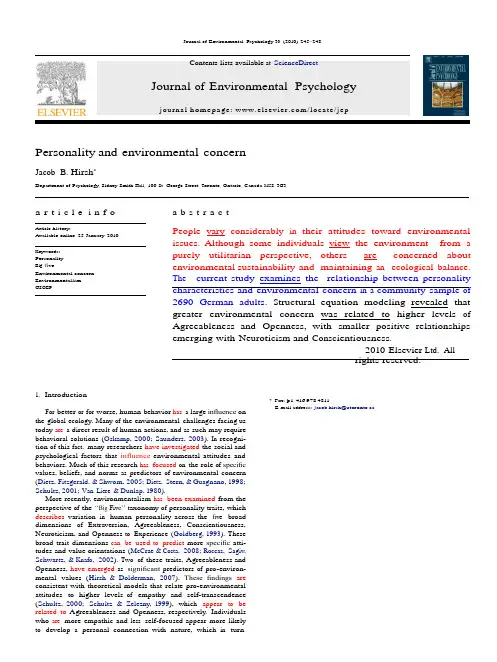

Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2010) 245–248Contents lists available at ScienceDirectJournal of Environmental Psychologyjo urn a l h ome pa g e:w w w.e l sev ier.co m/lo cat e/je pPersonality and environmental concernJacob B. Hirsh*Department of Psychology, Sidney Smith Hall, 100 St. George Street,T oront o,Ontario, Canada M5S 3G3a r t i c l e i n f oArticle history:Available online 25 January 2010K eywords:PersonalityBig fiveEnvironmental concernEnvir onmentalismGSOEPa b s t r a c tPeople vary considerably in their attitudes toward environmentalissues.Although some individuals view the environment from apurely utilitarian perspective, others are concerned aboutenvir onmenta l sustainability and maintaining an ecological balance.The current study examines the relationship between personalitycharacteristics and environmental concern in a community sample of2690 German adults. S tructural equation modeling revealed thatgreater environmental concern was related to hi gher levels ofAgreeableness and Openness, with smaller positive relationshipsemerging with Neuro t icism and Consc ientiousness.2010 Elsevier Ltd. Allrights reserved.1. IntroductionFor better or for worse, human behavior has a large influence onthe global ecology. Many of the environmental challenges facing ustoday are a direct result of human actions, and as such may requirebehavioral solutions (Oskamp, 2000; Saunders, 2003). In recogni-tion of this fact, many researchers have investigated the social andpsychological factors that influence environmental attitudes andbehaviors. Much of this research has focused on the role of specificvalues, beliefs, and norms as predictors of environmental concern(Dietz, Fitzgerald, & Shwom, 2005; Dietz, S tern, & Guagnano, 1998;Schultz, 2001; Van Liere & Dunlap, 1980).More rec ently,environmentalism has been examined from theperspective of the ‘‘Big Fiv e’’taxonomy of personality traits, whichdescribes variation in human personality across the five broaddimensions of Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness,Neuroticism, and Openness to Experience (Goldberg, 1993). Thesebroad trait dimensions can be used to predict more specific atti-tudes and value orientations (McCrae & Costa, 2008; Roccas, Sagi v,Schwartz, & Knafo, 2002). Two of these traits, Agreeableness andOpenness, have emerged as significant predictors of pr o-environ-mental values (Hirsh & Dolderman, 2007). These findings areconsistent with theoretical models that relate pr o-environmentalattitudes to higher levels of empathy and self-transcendence(Schultz, 2000; Schultz & Zelezny, 1999), which appear to berelated to Agreeableness and Openness, r espectiv ely.Indiv idualswho are more empathic and less self-focused appear more likelyto develop a personal connection with nature, which in turn* Fax: þ1 416 978 4811.E-mail address: jacob.hirsh@ut oront o.capredicts their pro-environmental attitudes (Bragg, 1996; Mayer & F r antz, 2004). Indeed, developing such an emotional affinity toward the natural environment can bolster one’s motives for environmental protection (Kals, Schumacher, & Montada, 1999).While both Agreeableness and Openness fit well into theoretical models of pro-environmental attitudes, the initial study demon- strating their predictive utility was limited to a relatively small sample of undergraduate students (N ¼ 106). The initial study w as also limited by the imbalance of male (n ¼ 32) and female (n ¼ 74) participants, making it difficult to examine the importance of gender as a moderating variable. The current study extends this previous research by examining the personality predictors of environmental concern in a much larger community sample of German adults (N ¼ 2690). Addi tionally, structural equation modeling was used to provide error-reduced estimates of the true relationships between the variables of interest. It was h ypo thesized that both Agreeableness and Openness would remain significant predictors of increased environmental concern.2. Methods2.1. ParticipantsData analyses were based on the responses of 2690 participants of the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (GSOEP), a longitudinal research project that polls a large and diverse sample of German households (Haisken-DeNew & Frick, 2005). While the full GSOEP sample is considerably large r, the current analysis could only be conducted on the subset of respondents who completed the available measures of personality and environmental concern, described below. The age of participants in the current sample ranged from 26 to 93 years (M ¼ 54.1, SD ¼ 14.6). A reas onably0272-4944/$ – see front matter 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserv ed. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.004246J.B. Hirsh / Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2010) 245–248balanced proportion of male (47%) and female (53%) responden ts were included.2.2. Materials2.2.1. Per sonalityIn 2005, GSOEP participants completed a 15-item version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI; Gerlitz & Schupp, 2005; John, Donahue, & K entle, 1991), which measures the Big Five personality traits of Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to Experience. This shortened version of the BFI, kno wn as the BFI-S, demonstrates good internal coherence and has been validated against longer inventories assessing the five major factors of personality. Each trait domain is represented by 3 descriptiv e phrases to which respondents must rate their agreement on a scale ranging from 1 (Does not apply) to 7 (Does apply). Sample phra ses include‘‘W orry a lot’’and ‘‘V alue artistic experiences’’.2.2.2. Environmental concernAlthough there is no standard scale measuring environmental concern in the GSOEP dataset, there are a number of specific item s that probe responden ts’ envi ronmental attitudes. In the curr ent analysis, we used3 items administered at multiple time points as indicators of a latent environmental concern factor. In particular, the items of interest were‘‘En vironmentally Conscious’’,‘‘Im p ortance of Environmental Pro tection’’, and ‘‘Worried about En viron ment’’. Each of these items was administered on multiple occasions. To the extent that there is a stable dispositional component to environ- mental concern, it should be captured by the shared variance of these cross-time measures (cf. K enn y & Zautra, 1995).The ‘‘Env ironme ntally conscious’’ item was administered in 1998 and 2003; the ‘‘Importance of envir onment’’item w as administered in 1994, 1998, and 1999; finall y,the ‘‘Worried about environme nt’’ it em was based on data collected in 2005–2007. Examining the shared variance amongst these items allowed for an error-reduced estimate of environmental concern across a large time period.2.3. Analytic techniqueS tructur al equation modeling was used to explicitly model sources of error in the dataset, thereby providing more accura te estimates of the true relationships between the variables of interest. In particular, we employed a measurement model that accounts for acquiescence bias, halo bias, and the observed corre- lations among Big Five personality traits (Anusic, Schimmac k, Pinkus, & Lockwood, 2009). First, each Big Five domain w as modeled as a latent factor reflec ted in the 3 indicator items (e.g.,‘‘V alue artistic experiences’’).Second, a halo bias factor was modeled as the shared variance among each of these latent Big Five domains. Third, an acquiescence factor was modeled as the shared v ariance amongst each of the individual questionnaire items.Fourth, the higher-order Big Five factors (DeYoung, 2006; Digman, 1997; McCrae et al., 2008) were modeled as refle cting the shared v ari- ance among Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Neu ro ticism (Stability or Alpha), and Extraversion and Openness (Plasticity or Beta). In order to ensure the model would be identified, the regression weights were fixed to be equal for the loadings within each of the halo, acquiescence, and higher-order personality factors. Note, how ev er, that while such equality constraints forc e the unstandardized coefficients to be equal, the standardized coefficients(as will be reported below) also depend upon the variance of the indicators and may thus differ from one ano ther.Environmental concern was modeled in a two-step hierar chical process. First, three latent variables were constructed, one for each set of the environmental items described above. For example, the three separate assessments of ‘‘Importance of envi ronmental prot ection’’were used as indicators of a latent factor.Second, an overall environmental concern factor was modeled as the shared variance amongst each of the three item-based envi ronmental factors. Regression lines predicting this overall envi ronmental concern variable were drawn from each of the latent Big Five tra it factors. The resulting model allowed for an error-reduced e xami- nation of the contributions of the Big Five personality traits to environmental concern over time.3. R esults3.1. Model fitR e as on ablefit is provided by a mode l when CFI > .90, RMSEA < .08, and SRMR < .10 (Kline, 2005). The current model demon st r at ed acceptable to good fit, wi th a CFI of .91, RMSEA of .045 (90%co nfide nc e interval of .043–.047),and SRMR of .05. The chi-square value of 1406.46 (df ¼ 218) was significant at p < .001; h o we v er,because t he current sample is relatively large, the chi-square test is not an op t imal indicator of fit.3.2. Personality and environmental concernThe model and estimated parameters are presented in Fig. 1. The latent environmental concern factor was strongly related to each of the three item-based environmental factors, including ‘‘importance of environmental prot ection’’(b ¼ .94), ‘‘worried about envi ron- ment’’ (b ¼ .64), and ‘‘envi ronmentally conscious’’(b ¼ .62). Envi- ronmental concern was in turn significant ly predicted by indivi dual differences in the Big Five personality traits. In particular, great er environmental concern was significant ly associated with higher levels of Agreeableness (b ¼ .22), Openness (b ¼ .20), Neuroticism (b ¼ .16), and Conscientiousness (b ¼ .07). In contrast, no significant relationship was observed with Extraversion (b ¼ .02).3.3. Demographic v ariablesAge, g ender,and household income were added to the model in order to examine the importance of demographic variables in predicting environmental concern. A regression line predicting the latent environmental concern factor was drawn from each of the demographic variables. Including these variables did not chang e the relationships between personality and environmental concern, although it did decrease the overall fit of the model (CFI ¼ .84; RMSEA ¼ .053; SRMR ¼ .06). Non etheless, significant r elationships were observed, with environmental concern being positi vely associated with age (b ¼ .13) and negatively with household income (b ¼ .06). Women also displayed higher levels of envi ronmental concern than men (b ¼ .07), consistent with previous research (Davidson & F reudenb urg,1996).3.4. Examination of possible gender moder ationBecause the sample contained a large number of both males a n d f ema les, it was possible to examine the possible interactions b e t wee n gender and personality in the prediction of environmental concern. The model depicted in Fig. 1 was therefore extended to a multip l e- groups confirmatory factor analysis, with the model being e s t im a t ed simultaneously for males and female s. The model again demons t r at ed acceptable fit when no equality constraints were imposed ac r oss groups (CFI ¼ .91; RMSEA ¼ .031; SRMR ¼ .054). Constraining t h e factor loadings and structural covariances to be equal across t h e g r o ups did not significantly reduce model fit (CFI ¼ .91; RMSEA ¼ .030;J.B. Hirsh / Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2010) 245–248 247Fig. 1. Structural regression model with the Big Five traits predicting environmental concern. Halo represents an evaluative bias factor.Acquiescence represents acquiescence bias in scale usage. Stability and Plasticity represent the two higher-order Big Five traits. EC1 ¼ ‘‘Importance of Environmental Pro tection’’ items; EC2 ¼ ‘‘Worried about Envir onment’’ items; EC3 ¼ ‘‘Envi ronmentally Con scious’’ items. S tructu ral error terms are presented for all endogenous variables, with the critical ratios in parentheses. Measurement error t erms were omitted from the figure to improve readability.SRMR ¼ .056;Dc2 ¼ 31.67,D df ¼ 26, p ¼ .20). Co n v e r s e l y,w i th this fu ll y constrained model in pl ac e,allowing the regression weights of the Bi g Five domains on the E n v i r o n me n t a l C o n ce r n variable to vary freely d id not improve model fit (CFI ¼ .91; RMSEA ¼ .031; SRMR ¼ .056;Dc2 ¼2.73, D df ¼ 5, p ¼ .74). The relationship between the Big Five and environmental concern thus did not appear to be moderated b y ge n d er.4. DiscussionAs in previous r esearch, greater environmental concern w as related to higher levels of the Big Five personality traits of Agree- ableness and Openness (Hirsh & Dolderman, 2007). These rela- tionships appear to be relatively robust, given that they wer e replicated using different measures, obtained from an adult rather than student population, and in a German rather than Canadian sample. Ad ditionally, these effects were observed despite the removal of error variance through structural equation modeling. The current study thus provides additional support for the impor- tance of these two personality traits in predicting environmental attitudes, while further demonstrating that their importance does not appear to be moderated by gender.Bo th Agreeableness and Openness have be en related to the h ig he r- order personal value of se lf-t r an sc e nd e nc e, reflecting an e xp a nd ed sense of self and a greater concern for others (Olver & Mo orad ian,2003; Roccas et al., 2002). Agreeableness, for in st an ce, is related t o higher levels of empathy (Ashton, Paunonen, Helmes, & J ac kso n, 1998), which is thought to support pro-environmental mo t i v e s (Sc h ul tz,2000).I nd ivi du als who are lower in Agreeableness tend t o be more selfish generally spe ak in g,and are less concerned about t he welfare of others. Op e nn e ss,meanwhile,is associated with in cr eased cognitive ability and flexibility in thought (De Y ou n g, Peterson, & Higgins, 2005), potentially affording a broader perspective on h umanit y’s place in the larger ecology and a greater aes th eti c appreciation of natural beauty. Less open individuals, in co n tr as t,are likely to have a narrower and more conservative perspective on na tur e’s v a l ue.An unexpected finding was the effect of Neuroticism,with more neurotic individuals demonstrating significant ly higher levels of environmental concern. Although this relationship was not found in the preliminary study that employed the Big Five (Hirsh & Dolderman, 2007), it was previously found to predict support for environmental preservation (Wiseman & Bogner, 2003) when measured with the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975). One explanation for this finding is that neuro tic individuals tend to be more worried about negative outcomes in general, and so concern about the environment may reflect anxiety about the consequences of environmental degradation (whereas emotionally stable individuals would potentially experience less affective disturbance when thinking about this topic). It is thus248J.B. Hirsh / Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2010) 245–248possible that neurotic individuals would demonstrate a more egoistic form of environmental concern, rather than an altruistic one (Schultz, 2001).A second finding that was unpredicted from previous research on this topic is the fact that Conscientiousness had a small but signifi- cant positive association with environmental concern. Given the relatively small magnitude of this relationship, it is perhaps unsur- prising that the previous study employing a smaller sample size did not uncover this result. The importance of Conscientiousness for environmental concern is consistent with studies that link this tra it to higher levels of social investment and prudent rule-adherence in general (Lodi-Smith & Roberts, 2007). Highly conscientious indi- viduals might be expected to carefully follow social guidelines and norms for appropriate environmental action, whereas less consci- entious individuals might be more willing to ‘‘cut corners’’ when it comes to environmentally responsible beha vior.The current analysis has a number of strengths over previous inquiries into the relationship between personality and environ- mental concern. First, the large sample provided by the longitudinal GSOEP study allowed for a more detailed structural analysis of the relevant variables. Second, the sample was more representative of the larger population in terms of age and gender distribution. While previous research has mostly employed undergraduate students, the current sample had a much broader age range that stret ched further into the lifespan. Third, the inclusion of multiple time-lagg ed measures allowed for an examination of the personality pr edictor s of environmental concern across long periods of time.Despite the strengths of the study,there are also some note- worthy limitations. These limitations are primarily related to the measures that were administered as part of the GSOEP project. In particular,while the 15-item BFI-S provides a good measure of the broad Big Five factors, it does not allow for an assessment of low er- order personality traits. It is possible that certain aspects of each Big Five domain would be more strongly related to environmental concern than others, but this could not be examined in the curr ent data. Similarly,the measures of environmental concern we re derived from the available items,but they did not refle ct a compre- hensive coverage of the entire domain of environmental attitudes. It is certainly possible that personality traits may be differ entiall y related to the various aspects of environmental concern (Milfont & Duckitt, 2004; Schultz, 2001; Wiseman & Bogner, 2003). Futu re research could explore these possibilities by employing more detailed measures of personality and environmental concern. Nonetheless, the current study provides support for the importance of personality traits in relation to environmental attitudes, and thereby provides a useful framework for more targeted inv estiga- tions into the processes underlying these relatio nships.R eferencesAnusic, I., Schimmack, U., Pinkus, R., & Lockwood, P. (2009). The nature and structure of correlations among big five ratings: the halo-alpha-beta model.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1142–1156.Ashton, M., Paunonen, S., Helmes, E., & Jackson, D. (1998). Kin altruism, recipr ocal altruism, and the big five personality factors. Evolution and Human Behavior, 19(4), 243–255.Bragg, E. A. (1996). T owards ecological self: deep ecology meets constructionist self- theory. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 16(2), 93–108.Davidson, D., & F reudenburg,W. (1996). Gender and environmental risk concerns:a review and analysis of available research. Environment and Behavior, 28(3),302–339.DeYoung, C. G. (2006). Higher-order factors of the big five in a multi-informant sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(6), 1138–1151. DeYoung, C. G., Peterson, J. B., & Higgins, D. M. (2005). Sources of openness/int el- lect: cognitive and neuropsychological correlates of the fifth factor of person- ality. Journal of Personality,73(4), 825–858.Dietz, T., Fitzgerald, A., & Shwom, R. (2005). Environmental values. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 30, 335–372.Dietz, T., Stern, P., & Guagnano, G. (1998). Social structural and social psychological bases of environmental concern. Environment and Behavior, 30(4), 450–471. Digman, J. M. (1997). Higher-order factors of the big five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(6), 1246–1256.Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck personality ques- tionnaire. London: Hodder & S tought on.Gerlitz, J., & Schupp, J. (2005). Zur erhebung der big-five-basierten pers o¨n-lichkeitsmerkmale im SOEP. [The collection of big-five-based personality char ac- teristics in the SOEP]. DIW Research Note, 4.Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 48(1), 26–34.Haisken-DeN ew, J., & Frick, J. (2005). Desktop companion to the German socio- economic panel study. Berlin: German Institute for Economic R esearch(DIW). Hirsh, J. B., & Dolderman, D. (2007). Personality predictors of consumerism and environmentalism: a preliminary study. Personality and Individual Dif f erences, 43, 1583–1593.John, O., Donahue, E., & K entle, R. (1991). The big five inventory: V ersions4a and 54.Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.Kals, E., Schumacher, D., & Montada, L. (1999). Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Environment and Behavior, 31(2), 178–202.K enn y, D., & Zautra, A. (1995). The trait-state-error model for multiwave data.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(1), 52–59.Kline, R. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New Y ork: The Guilford Press.Lodi-Smith, J., & Roberts, B. (2007). Social investment and personality: a meta-analysis of the relationship of personality traits to investment in wor k, family, religion, and volunteerism. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(1), 68–86.Mayer, F., & F rantz, C. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: a measure of individuals’feeling in community with nature. Journal of En vironmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515.McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2008). The five-factor theory of personality. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality theory and research (3rd ed.). (pp. 159–181) New York, USA: Guilford Press.McCrae, R. R., Jang, K. L., Ando, J., Ono, Y., Y amagata, S., Riemann, R., et al. (2008).Substance and artifact in the higher-order factors of the big five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(2), 442–455.Milfont, T., & Duckitt, J. (2004). The structure of environmental attitudes: a first-and second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Environmental Psyc hology, 24(3), 289–303.Olver, J., & Mooradian, T. (2003). Personality traits and personal values: a conceptual and empirical integration. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(1), 109–125. Oskamp, S. (2000). A sustainable future for humanity? How can psychology help?American Psychologist, 55(5), 496–508.Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S., & Knafo, A. (2002). The big five personality factors and personal values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 789–801. Saunders, C. (2003). The emerging field of conservation psychology. Human Ecology Review, 10(2), 137–149.Schultz, P. W. (2000). Empathizing with nature: the effects of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 391–406. Schultz, P. W. (2001). The structure of environmental concern: concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(4), 327–339.Schultz, P. W., & Zelezny, L. (1999). Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: evidence for consistency across 14 countries. Journal of En vironmental Psychology, 19(3), 255–265.Van Liere, K., & Dunlap, R. (1980). The social bases of environmental concern:a review of hypotheses, explanations and empirical evidence. Public OpinionQuarterly,44(2), 181–197.Wiseman, M., & Bogner, F. (2003). A higher-order model of ecological values and its relationship to personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(5), 783–794.。

经济管理学院毕业论文环节文献综述要求本科毕业论文(设计)文献综述题目学生姓名学号专业班级指导教师国内土地发展权研究综述土地发展权(Land Development Rights)是从20世纪50年代初开始,在英、美、法等国相继设置的一项重要土地产权制度。

尽管中国事实上存在着大量的土地发展权问题,但是目前还没有相关的制度设置。

20世纪90年代末期以来,中国国内不少学者分别从法学、经济学等角度,在理论上做了大量的研究和探讨。

笔者通过对这些文献的梳理和分析,发现国内对土地发展权的研究主要集中在其概念、归属、流转、可行性与必要性等问题上。

一土地发展权的概念关于土地发展权的概念,国内学术界大致有狭义和广义两种理解。

(一)狭义的土地发展权狭义的土地发展权,主张它是土地所有权人将自己拥有的土地变更用途或在土地上兴建建筑改良物(包括建筑物与工事)而获利的权利。

沈守愚(1998)[1]较早从法学的角度将农地发展权界定为“将农地变更为非农用地的变更利用权”。

王小映(2003)[2]则认为,土地发展权是一种农地可转为建设用地进行开发利用的权利;黄祖辉等(2002)[3]深入分析了农村集体土地转为城市国有土地对农村土地发展权的侵害及其补偿问题;杨明洪等(2002,2003)[4,5]分析了中国农民集体所有土地发展权从法律和事实上受到压抑以及农民进行抗争的情况。

杜业明(2004)[6]认为,土地发展权是指某组织或个人变更土地用途而获得额外收益的权利。

而农村土地发展权是特指农用地转为建设用地和农村存量建设用地直接进入土地一级市场而获取收益的权利。

周建春(2007)[7]认为,农地发展权又称土地发展权或土地开发权,是指将农地改为最佳利用方向的权利,也可狭义地定义为农(耕)地改为建设用地的权利。

(二)广义的土地发展权广义的土地发展权涉及土地利用和再开发的用途转变和利用强度的提高而获利的权利。

胡兰玲(2002)[8]认为,土地发展权是指对土地在利用上进行再发展的权利,即在空间上向纵深方向发展、在使用时变更土地用途之权,可将其分为两类:空间(高空,地下)建筑权(Space,Underground Building Tenancy)和土地开发权(Land-ExploitingRight)。

关于2007届毕业研究生上传研究生学位论文、摘要与题录的规定和有关通知为加强博士和硕士生的学位论文工作,提高学位论文质量,进一步加强国内外学术交流和科技合作,扩大我校影响,从今年起,北京林业大学研究生院决定毕业研究生应通过研究生院主页的“研究生信息管理系统”上传研究生学位论文、摘要与题录。

现对有关事项做如下规定:一、博士学位论文题录(一)编写格式博士学位论文中文题目(字号:小五;字体:黑体) = 博士学位论文英文题目(字号:小五;字体:Times New Roman)/博士生姓名(字号:小五;字体:宋体);导师(空一个字符;字号:小五;字体:宋体)导师姓名(空一个字符;字号:小五;字体:宋体)(空一个字符)(省部级资助项目名称)(字号:小五;字体:宋体)段落要求:1.5倍行距。

(二)编写示例金沙江流域(滇东北段)退耕还林模式及其配套技术研究= Study on Models and Associated Techniques of the Conversion of Farmland to Forest in Jinsha River Watershed Northeast of Yunnan Province /方向京;导师张洪江小兴安岭北部沼泽湿地植被特征与营养元素动态研究= Study on Vegetation Character and Nutrient Elements Dynamics of Marsh Wetland in North of Xiaoxing’an Mountain /满秀玲;导师王建中(黑龙江省科技攻关项目)人工林无线电传输特性及立木整枝机控制系统研究= Studies on Radio Wave Propagation Mechanisms Through Plantation Forest and Control System of Pruning Machine /张俊梅;导师李文彬,撒潮(国家林业局“948”引进项目)基于GIS和ANN的时空相关单木生长模型研究= Study on Individual Tree Growth Modeling Based GIS and ANN/任谊群;导师冯仲科,鞠洪波(国家“863”高新技术项目、国家自然科学基金项目、北京市自然科学基金项目)(三)其他属以下(含属)的拉丁学名(属名(第一个字母大写)、种名(全小写))等用斜体;此外,凡是博士英文题目中的实词,第一个字母应大写;2、当博士指导教师为两个或两个以上时,导师与导师姓名之间应用逗号隔开;3、对于基金项目只注明资助该研究的项目名称,不标项目编号;而且项目名称必须完整、规范(对于北京市和国家级科研项目名称可参照附件);当资助项目为两个或两个以上时,项目与项目之间用顿号隔开;当资助项目为北京市或省部级项目以外时,不填写其资助项目。

北京林业大学研究生学位论文格式的统一要求学位论文是表明作者具有开创性研究成果,或在研究工作中具有新的见解,并据此为内容撰写而成,作为提出相应评审用的学术论文。

为进一步提高学位论文的质量,规范学位论文的撰写、打印及装订格式,并便于储存、检索、利用及交流等,特制定如下要求:一、一般内容和格式学位论文用纸规格为A4,页面上边距和左边距分别为3cm,下边距和右边距分别为2.5cm。

页眉:5号宋体字,页边距为2cm,偶数页为学位论文题目,奇数页为所在章节的题目。

页脚:页码从正文第一页开始编写,用阿拉伯数字编排,正文以前包括摘要的页码用罗马数字,一律居中。

1、题目:题目应概括整个论文最主要的内容,恰当、简明、引人注目,力求简短,严格控制在20字以内。

2、独创性声明:论文第一页为《独创性声明》和《关于论文使用和授权的声明》,具体格式和内容可在学校研究生院网页上下载。

要求每本论文必不可缺,并有亲笔手写体签名。

3、摘要:①论文第二页为中文摘要,硕士论文摘要的字数一般为300字,博士论文摘要约800~1000字,应说明工作的目的、研究方法、结果和最终结论。

要突出本论文的创造性成果或新的见解,语言力求精炼。

为便于文献检索,应在本页下方另起一行注明本文的关键词(3~5个);②论文第三页为英文摘要,内容与中文同,不超过250个实词,上方应有英文题目。

第二行写研究生姓名;并将专业名用括弧括起置于姓名之后,第三行写导师姓名,格式为Directed by …,最下方一行为关键词,应与中文对应,便于国际交流。

中文摘要:(1)标题3号黑体,单倍行距,段前0.5行,段后1行;(2)主体部分用小4号宋体,1.5倍行距;(3)关键词:小4号宋体。

英文摘要:(1)题目用小3号Times New Roman,单倍行距,段前0.5行,段后1行;(2)主体部分用5号Times New Roman,1.5倍行距;(3)关键词:小4号Times New Roman。

附件4:北京林业大学硕士研究生培养的公共要求一、培养目标1. 思想品德要求:学习和掌握马列主义、毛泽东思想、邓小平理论和"三个代表"重要思想;热爱祖国拥护党的基本路线、方针和政策;树立科学发展观有高尚的科学道德素质;具有团结协作、和蔼共事的精神;诚信守法品行端正实事求是;艰苦奋斗能积极为社会主义现代化建设事业服务2. 专业能力要求(详见各学科专业培养方案要求)3. 体质要求:具有在艰苦条件下开展工作的健康体魄和心理素质二、学习年限学习年限一般为3年在职研究生可延长1年课程学习与论文工作并重课程学习应在入学后一年内完成其余两年时间主要用于论文工作研究生学位论文(设计)答辩合格经院学位评定分委员会审议通过校学位评定委员会审批后即可授予学位如研究生提前完成学业或有其他原因经本人申请导师同意所在学院主管院长批准可适当缩短学制或延长学习年限提前毕业时间不能超过1年三、学分与课程学习要求硕士研究生实行学分制管理总学分基本要求为28学分包括课程学习23学分(自然科学和工学类不超过25学分人文社科类不超过27学分)、开题报告2学分、专业外语1学分、Seminar课程2学分课程设置分学位课和选修课两类:学位课(含外语、自然辩证法和科学社会主义理论与实践三门公共课)学分基本要求为16学分(自然科学和工学类不超过18学分人文社科类不超过20学分);各学科所列选修课数量限定在3~6门其余课程可从其他学科所开设的课程中共享课程学习原则上应在1学年内完成(一) 学位课(16~20学分)1、公共学位课(公共课)(10学分)第一外国语 6学分自然辩证法 2学分科学社会主义理论与实践 2学分2、专业学位课(专业基础及专业课)(6~10学分)主要学习本学科和相邻学科或学科群的前沿、交叉性知识(二) 选修课:其他非学位课程研究生在读期间如有不及格的课程则不能正常毕业和参加学位论文答辩跨学科门类考取的研究生以及在本学科欠缺本科层次数学基础课、专业基础课和专业课的研究生在硕士阶段应在导师指导下补修3~5门与硕士学科专业对应的本科专业或门类的本科层次的必修课程补修课程只记成绩不计学分(三) 必修环节(5学分)1、开题报告 2学分2、专业外语 1学分3、Seminar课程 2学分四、培养环节1. 培养计划导师应根据研究生不同特点指导研究生做好个人培养计划根据专业培养方向的要求和研究生的特长爱好选择不同的培养方式铸造不同类型的人才关注创新型人才的培养和成长个人培养计划要在研究生入学后1个月内由导师、导师组成员和研究生共同制定培养计划应确定学位课和选修课应对参加教学、生产实践活动、科学研究及论文撰写等做出具体安排培养计划由学科负责审定经学院主管研究生工作的负责人批准后执行并在学院研究生管理部门备案各学院、学科应认真贯彻党的教育方针建立健全研究生管理制度实行导师全面负责、导师组成员积极参与指导的制度加强思想政治教育合理安排教学计划和其它各项活动培养研究生理论联系实际的精神和严谨的治学态度2. 文献综述与开题报告硕士生应在导师指导下通过查阅文献资料调查研究写出文献综述并进行开题报告文献综述要对相关研究领域的发展趋势、国内外的最新科研成果及研究方法进行论述并提出自己的看法要求:①字数至少5000字;要求文字精练通顺条理清晰;②中外文参考文献应分开文献一般不少于50篇且外文文献至少占1/4;③在开题报告前完成由导师负责评分并写出评语开题报告应包括开题的意义、国内外发展动态、研究趋势、技术路线、研究方法的可行性、经费概算可能出现的机遇与风险等开题报告必须在有3人以上的专家小组会上进行论证论证通过者记2学分文献综述和开题报告均在研究生入学后的第一学年内完成在此基础上硕士生应在导师的指导下尽快拟定论文的具体工作计划并实施3. 中期考核为了加强研究生管理提高研究生培养质量在研究生学习期间实施中期考核制度中期考核时间安排在第4学期初由学科负责人、辅导员、导师及专家组成中期考核小组对研究生思想品德、文献综述、开题报告、学习成绩、科研能力及健康状况进行全面考核根据考核结果进行分流成绩合格者继续攻读成绩优秀者给予奖励并可申请提前攻读博士学位;不合格者按照学籍管理条例处理4. 论文发表研究生在读期间必须以第一作者身份、以北京林业大学为第一作者单位公开发表(或已被录用)至少有一篇是属于本学科研究领域的学术论文5. 教学实践实践环节是培养研究生实际动手能力的重要手段是研究生学习过程中必不可少的重要环节在第二、三学年学科应安排研究生参加部分教学工作如协助指导本科生论文、试验以及课后辅导、批改作业等工作量应不少于20个工作日学科负责人和导师要共同对研究生实践环节的完成情况进行考核和评定对未参加实践环节或考核不合格者不予毕业6. 学术活动学科和导师应尽可能为研究生到外单位或外地进行试验、实习、调查研究、参加学术会议提供并创造条件使研究生从多渠道了解学科发展的动向开阔视野增强开拓创新精神和团队意识此项活动要纳入教学计划研究生在学期间至少应在Seminar课程之外参加6次以上校级以上学术活动每次参加学术活动后研究生要写出500字的书面小结内容包括活动的时间、地点、报告人(主持人)及学术报告的题目(活动的主题)阐明自己对相关问题的学术观点或看法经导师考核和签字每年由学科审核一次并与奖学金评定挂钩申请答辩前提交学院研究生秘书审核7. 公益劳动为加强研究生的劳动观念和社会责任感研究生在整个学习期间要参加学校和学科组织的适量公益劳动有考核的公益劳动累计2~3周考核不合格者不予毕业五、培养方式与方法硕士生培养采取指导教师负责制提倡导师个别指导与集体指导相结合的培养方式六、论文工作与要求研究生的论文工作是对研究生进行科学研究能力的综合训练学位论文的基本要求是:论文的选题应有较强的理论意义和实践意义研究结果应有新的见解、创新或能解决某方面的社会实际问题能表明作者具有从事科学研究或独立承担技术工作的能力研究生应以严谨求实的态度对待论文工作尊重学科切忌弄虚作假研究生的论文应在导师指导下独立完成论文篇幅一般在3万字左右摘要在1000字左右要求立论准确概念清楚分析严谨计算无误数据可靠文字简练图表清晰七、论文答辩与学位授予硕士生必须完成上述各个教学和培养环节并达到规定的学分完成论文的撰写由导师推荐方可申请硕士论文答辩申请答辩与学位授予按教育部和我校有关规定进行你如果认识从前的我,也许会原谅现在的我。