Virginia Woolf and E. M. Forster - 副本

- 格式:doc

- 大小:149.50 KB

- 文档页数:31

The Analysis of Virginia Woolf作者:戴寒路来源:《校园英语·中旬》2014年第11期Virginia Woolf is a British writer, one of the representatives criticism at home, stream of consciousness novel.“Mark on the Wall”is her first article typical stream of consciousness works.Virginia Woolf has a complicated family background.The nine homes, two groups of children between age and personality clashes often occur some contradictions and conflicts.Woolf's half-brother and two of her injuries left her permanently traumatized.After his mother died in 1895, it was her first mental breakdown.Later, she tells in his autobiography,“the existence of the moment”in which she and her sister Vanessa · Bell, had been subjected to half-brother George and Jared · Duke Voss VirginiaWoolf · sexual assault.Quentin Bell believes trauma auditory hallucinations Virginia Eugenia's insanity and suicide pre-adolescent and Virginia suffered lead to healing wounds related.In fact,Virginia is very obnoxious adult life, more reluctant to have children, for homosexual attachment and even became the focus of her emotional world.It is true that for the complex emotional relationship Bloomsbury circles, and can not be viewed lightly in the eyes of ordinary people, even so, Virginia's emotional state is still considered outrageous.Her sister Wanai Sa hopelessly count on, or even one of the most unexpected extreme way - and her husband Clive flirting, and its own feelings as a substitute or a puppet.Virginia is always the focus of attention, whether alive or dead,in addition to their artistic talent, as well as their lives privacy.Virginia suffering from severe depression, she had written a letter in 1936 a friend mentioned:“....never trust a letter of mine not to exaggerate that's wri tten after a night lying awake looking at a bottle of chloral and saying, No, no no, you shall not take it.It's odd how sleeplessness, even of a modified kind, has the power to frighten me.It's connected I think with these awful times when I couldn 't cont rol myself.”Virginia Woolf put art above all else.However, she works each completed a trillion disease often occur, changing the character she often face reflects inner pain.The only good news is the onset of her every game, there beside her husband Leonard meticulous care, which will undoubtedly bring great encouragement Virginia and moved,“If it was for his sake, I had shot himself .”When the symptoms of schizophrenia and hearing voices repeat struck madness, ultimately unbearable, she still thought of suicide, in Leonard's last words to her written:“I can not ruin your life I think two people could not be more happy than we have been.”Woolf was the first to put forward the “androgyny” feminists.She abandoned the meaning of biol ogy and psychology played an implication on.She borrowed “androgyny”explores the planing for the question:“In each of us there are two forces dictate everything So it seems.Woolf advocated is actually an ideal literary mind that gender is completely platform for harmonious co-existence of the realm is the gist of her poetic theory.But she thinks because of women's unique experience,experience - pregnancy,childbirth.“Sense”that women are bisexual '; men - everyone knows - is poised to maintain the glory o f men worship a single viewpoint.”Androgyny is not particularly sharp against the city.Does not exclude any one of, Can communicate with each other inspired by the huge enclosed force.But she mystification for the female body.As well as “female writing” over-sharing Chong.Have preached the dangers of female supremacy.Although the long-term resistance meter people writing theory Woolf “androgyny”multi-controversial.But it is undeniable yes.Woolf advocated male writers and female writers must transcend gender identity and writing.Has its forward-thinking and unique significance.From this point of view.Mrs.Wolf is undoubtedly great.Among the many works of Woolf's “Orlando”is undoubtedly different.Its “androgyny” typical creative concept.1925 or so.Prod uced some unusual friendship between Woolf and 薇塔.This is perhaps a kind Woolf “androgyny”personal experience.1928.Woolf to cut the tower because of being female and five suffered ancestral estate law get inheritance rights for the material.Written a humorous light fantasy novel - “Orlando.”Unique address of the novel is that it across time and space and gender barriers.References:[1]Wang Hung stream:“On Woolf's androgyny feminism”,“Journal of theNortheast”September 2010 fifth.。

Professions for Women 女人职业_儿童英汉双语故事Born in England, Virginia Woolf was the daughter of Leslie Stephen, a well-known scholar. She was educated primarily at home and attributed her love of reading to the early and complete access she was given to her fathers library. With her husband, Leonard Woolf, she founded the Hogarth Press and became known as member of the Bloomsbury group of intellectuals, which included economist John Maynard Keynes, biographer Lytton Strachey, novelist E. M. Forster, and art historian Clive Bell. Although she was a central figure in London literary life, Woolf often saw herself as isolated from the mains stream because she was a woman. Woolf is best known for her experimental, modernist novels, including Mrs. Dalloway(1925) and To the Lighthouse(1927) which are widely appreciated for her breakthrough into a new mode and technique--the stream of consciousness. In her diary and CRItical essays she has much to say about women and fiction. Her 1929 book A Room of Ones Own documents her desire for women to take their rightful place in literary history and as an essayist she has occupied a high place in 20th century literature. The common Reader (1925 first series; 1932 second series) has acquired classic status. She also wrote short stories and biographies. Professions for Women taken from The collected Essays V ol 2. is originally a paper Woolf read to the Womens ServiceLeague, an organization for professional women in London.When your secretary invited me to come here, she told me that your Society is concerned with the employment of women and she suggested that I might tell you something about my own professional experiences. It is true that I am a woman; it is true I am employed; but what professional experiences have I had? It is difficult to say. My profession is literature; and in that profession there are fewer experiences for women than in any other, with the exception of the stage--fewer, I mean, that are peculiar to women. For the road was cut many years ago---by Fanny Burney, by Aphra Behn, by Harriet Martineau, by Jane Austen, by George Eliot many famous women, and many more unknown and forgotten, have been before me, making the path smooth, and regulating my steps. Thus, when I came to write, there were very few material obstacles in my way. Writing was a reputable and harmless occupation. The family peace was not broken by the scratching of a pen. No demand was made upon the family purse. For ten and sixpence one can buy paper enough to write all the plays of Shakespeare--if one has a mind that way. Pianos and models, Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, masters and mistresses, are not needed by a writer. The cheapness of writing paper is, of course, the reason why women have succeeded as writers before they have succeeded in the other professions.But to tell you my story--it is a simple one. You have only got tofigure to yourselves a girl in a bedroom with a pen in her hand. She had only to move that pen from left to right--from ten oclock to one. Then it occurred to her to do what is simple and cheap enough after all--to slip a few of those pages into an envelope, fix a penny stamp in the corner, and drop the envelope into the red box at the corner. It was thus that I became a journalist; and my effort was rewarded on the first day of the following month--a very glorious day it was for me--by a letter from an editor containing a check for one pound ten shillings and sixpence. But to show you how little I deserve to be called a professional woman, how little I know of the struggles and difficulties of such lives, I have to admit that instead of spending that sum upon bread and butter, rent, shoes and stockings, or butchers bills, I went out and bought a cat--a beautiful cat, a Persian cat, which very soon involved me in bitter disputes with my neighbors.What could be easier than to write articles and to buy Persian cats with the profits? But wait a moment. Articles have to be about something. Mine, I seem to remember, was about a novel by a famous man. And while I was writing this review, I discovered that if I were going to review books I should need to do battle with a certain phantom. And the phantom was a woman, and when I came to know her better I called her after the heroine of a famous poem, The Angel in the House. It was she who used to come between me an my paper when I was writing reviews.It was she who bothered me and wasted my time and so tormented me that at last I killed her. You who come off a younger and happier generation may not have heard of her--you may not know what I mean by The Angel in the House. I will desCRIbe her as shortly as I can. She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She saCRIficed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draft she sat in it--in short she was so constituted that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others. Above all--I need not say it--she was pure. Her purity was supposed to be her chief beauty--her blushes, her great grace. In those days--the last of Queen Victoria--every house had its Angel. And when I came to write I encountered her with the very first words. The shadow of her wings fell on my page; I heard the rustling of her skirts in the room. Directly, that is to say, I took my pen in my hand to review that novel by a famous man, she slipped behind me and whispered:My dear, you are a young woman. You are writing about a book that has been written by a man. Be sympathetic; be tender; flatter; deceive; use all the art and wiles of our sex. Never let anybody guess that you have a mind of our own. Above all, be pure. And she made as if to guide my pen. I now record the one act for which I take some credit to myself, though the credit rightly belongs to some excellent ancestors of mine who left me acertain sum of money--shall we say five hundred pounds a year? --so that it was not necessary for me to depend solely on charm for my living. I turned upon her and caught her by the throat. I did my best to kill her. My excuse, If I were to be had up in a court of law, would be that I acted in self-defense. Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing. For, as I found, directly I put pen to paper, you cannot review even a novel without having a mind of your own, without expressing what you think to be the truth about human relations, morality, sex. And all these questions, according to the Angel of the House, cannot be dealt with freely and openly by women; they must charm, they must conciliate, they mustto put it bluntly-tell lies if they are to succeed. Thus, whenever I felt the shadow of her wing or the radiance of her halo upon my page, I took up the inkpot and flung it at her. She died hard. Her fictitious nature was of great assistance to her. It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality. She was always creeping back when I thought I had dispatched her. Though I flatter myself that I killed her in the end, the struggle was severe; it took much time that had better have been spent upon learning Greek grammar; or in roaming the world in search of adventures. But it was a real experience; It was an experience that was bound befall all women writers at that time. Killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer.But to continue my story. The Angel was dead; what then remained?You may say that what remained was a simple and common object--a young woman in a bedroom with an inkpot. In other words, now that she had rid herself of falsehood, that young woman had only to be herself. Ah, but what is herself? I mean, what is a woman? I assure you, I do not know.I do not believe that you know. I do not believe that anybody can know until she has expressed herself in all the arts and professions open to human skill. That indeed is one of the reasons why I have come here--out of respect for you, who are in process of showing us by your experiments what a woman is, who are in process of providing us, by your failures and succeeded, with that extremely important piece of information.But to continue the story of my professional experiences. I made one pound ten and six by my first review; and I bought a Persian cat with the proceeds. Then I grew ambitious. A Persian cat is all very well, I said; but a Persian cat is not enough. I must have a motorcar. And it was thus that I became a novelist--for it is a very strange thing that people will give you a motorcar if you will tell them a story. It is a still stranger thing that there is nothing so delightful in the world as telling stories. It is far pleasanter than writing reviews of famous novels. And yet, if I am to obey your secretary and tell you my professional experiences as a novelist, I must tell you about a very strange experience that befell me as a novelist. And to understand it you must try first to imagine a novelists state of mind. I hope I am not giving away professional secrets if I say that a novelistschief desire is to be as unconscious as possible. He has to induce in himself a state of perpetual lethargy. He wants life to proceed with the utmost quiet and regularity. He wants to see the same faces, to read the same books, to do the same things day after day, month after month, while he is writing, so that nothing may break the illusion in which he is living--so that nothing may disturb or disquiet the mysterious nosings about, feelings round, darts, dashes, and sudden discoveries of that very shy and illusive spirit, the imagination. I suspect that this state is the same both for men and women. Be that as it may, I want you to imagine me writing a novel in a state of trance. I want you to figure to yourselves a girl sitting with a pen in her hand, which for minutes, and indeed for hours, she never dips into the inkpot. The image that comes to my mind when I think of this girl is the image of a fisherman lying sunk in dreams on the verge of a deep lake with a rod held out over the water. She was letting her imagination sweep unchecked round every rock and cranny of the world that lies submerged in the depths of our unconscious being. Now came the experience that I believe to be far commoner with women writers than with men. The line raced through the girls fingers. Her imagination had rushed away. It had sought the pools, the depths, the dark places where the largest fish slumber. And then there was a smash. There was an explosion. There was foam and confusion. The imagination had dashed itself against something hard. The girl was roused from her dream.She was indeed in a state of the most acute and difficult distress. To speak without figure, she had thought of something, something about the body, about the passions which it was unfitting for her as a woman to say. Men, her reason told her, would be shocked. The consciousness of what men will say of a woman who speaks the truth about her passions had roused her from her artists state of unconsciousness. She could write no more. The trace was over. Her imagination could work no longer. This I believe to be a very common experience with women writers--they are impeded by the extreme conventionality of the other sex. For though men sensibly allow themselves great freedom in these respects, I doubt that they realize or can control the extreme severity with which they condemn such freedom in women.These then were two very genuine experiences of my own. These were two of the adventures of my professional life. The first--killing the Angel in the House--I think I solved. She died. But the second, telling the truth about my own experiences as a body, I do not think I solved. I doubt that any woman has solved it yet. The obstacles against her are still immensely powerful--and yet they are very difficult to define. Outwardly, what is simpler than to write books? Outwardly, what obstacles are there for a woman rather than for a man? Inwardly, I think, the case is very different; she has still many ghosts to fight, many prejudices to overcome. Indeed it will be a long time still, I think, before a woman can sit down towrite a book without finding a phantom to be slain, a rock to be dashed against. And if this is so in literature, the freest of all professions for women, how is it in the new professions which you are now for the first time entering?Virginia Woolf。

A Room of One’s Own V I R G I N I A W O O L FContextVirginia Woolf was born Virginia Stephen in 1882 into a prominent and intellectually well-connected family. Her formal education was limited, but she grew up reading voraciously from the vast library of her father, the critic Leslie Stephen. Her youth was a traumatic one, including the early deaths of her mother and brother, a history of sexual abuse, and the beginnings of a depressive mental illness that plagued her intermittently throughout her life and eventually led to her suicide in 1941. After her father's death in 1904, Virginia and her sister (the painter Vanessa Bell) set up residence in a neighborhood of London called Bloomsbury, where they fell into association with a circle of intellectuals that included such figures as Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Roger Fry, and later E.M. Forster. In 1912, Virginia married Leonard Woolf, with whom she ran a small but influential printing press. The highly experimental character of her novels, and their brilliant formal innovations, established Woolf as a major figure of British modernism. Her novels, which include To the Lighthouse, Mrs. Dalloway, and The Waves, are particularly concerned with the lives and experiences of women.In October 1928, Virginia Woolf was invited to deliver lectures at Newnham College and Girton College, which at that time were the only women's colleges at Cambridge. These talks, on the topic of Women and Fiction, were expanded and revised into A Room of One's Own, which was printed in 1929. The title has become a virtual cliché in our culture, a fact that testifies to the book's importance and its enduring influence. Perhaps the single most important work of feminist literary criticism, A Room of One's Own explores the historical and contextual contingencies of literary achievement.SummaryThe dramatic setting of A Room of One's Own is that Woolf has been invited to lecture on the topic of Women and Fiction. She advances the thesis that "a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction." Her essay is constructed as a partly-fictionalized narrative of the thinking that led her to adopt this thesis. She dramatizes that mental process in the character of an imaginary narrator ("call me Mary Beton, Mary Seton, Mary Carmichael or by any name you please—it is not a matter of any importance") who is in her same position, wrestling with the same topic.The narrator begins her investigation at Oxbridge College, where she reflects on the different educational experiences available to men and women as well as on more material differences in their lives. She then spends a day in the British Library perusing the scholarship on women, all of which has written by men and all of which has been written in anger. Turning to history, she finds so little data about the everyday lives of women that she decides to reconstruct their existence imaginatively. The figure of Judith Shakespeare is generated as an example of the tragic fate a highly intelligent woman would have met with under those circumstances. In light of this background, she considers the achievements of the major women novelists of the nineteenth century and reflects on the importance of tradition to an aspiring writer. A survey of the current state of literature follows, conducted through a reading the first novel of one of the narrator's contemporaries. Woolf closes the essay with an exhortation to her audience of women to take up the tradition that has been so hardly bequeathed to them, and to increase the endowment for their own daughters.Character List"I" - The fictionalized author-surrogate ("call me Mary Beton, Mary Seton, Mary Carmichael or by any name you please—it is not a matter of any importance") whose process of reflection on the topic "women and fiction" forms the substance of the essay.The Narrator (In-Depth Analysis)The Beadle - An Oxbridge security official who reminds the narrator that only "Fellows and Scholars" are permitted on the grass; women must remain on the gravel path.Mary Seton - Student at Fernham College and friend of the narrator.Mary Beton - The narrator's aunt, whose legacy of five hundred pounds a year secures her niece's financial independence. (Mary Beton is also one of the names Woolf assigns to her narrator, whose identity, she says, is irrelevant.)Judith Shakespeare - The imagined sister of William Shakespeare, who suffers greatly and eventually commits suicide because she can find no socially acceptable outlets for her genius.Mary Carmichael - A fictitious novelist, contemporary with the narrator of Woolf's essay. In her first novel, she has "broken the sentence, broken the sequence" and forever changed the course of women's writing.Mr. A - An imagined male author, whose work is overshadowed by a looming self-consciousness and petulant self-assertiveness.Analysis of Major CharacterThe NarratorThe unnamed female narrator is the only major character in A Room of One’s Own. She refers to herself only as “I”; in chapter one of the text, she tells the reader to call her “Mary Beton, Mary Seton, Mary Carmichael or any other name you please . . . ” The narrator assumes each of these names at various points throughout the text. The constantly shifting nature of her identity complicates her narrative even more, since we must consider carefully who she is at any given moment. However, her shifting identity also gives her a more universal voice: by taking on different names and identities, the narrator emphasizes that her words apply to all women, not just herself.The dramatic setting for A Room of One’s Own is Woolf’s thought process in preparation for giving a lecture on the topic “women and fiction.” But the fictionalized narrator is distinct from the author Woolf. The narrator lends a storylike quality to the text, and she often blends fact and fiction to prove her points. Her liberty with factuality suggests that no irrefutable truth exists in the world—all truth is relative and subjective.The narrator is an erudite and engaging storyteller, and she uses the book to explore the multifaceted and rather complicatedhistory of literary achievement. Her provocative inquiries into the status quo of literature force readers to question the widely held assumption that women are inferior writers, compared to men, and this is why there is a dearth of memorable literary works by women. This literary journey is highlighted by numerous actual journeys, such as the journey around Oxbridge College and her tour of the British library. She interweaves her journeys with her own theories about the world—including the principle of “incandescence.” Woolf defines incandescence as the state in which everything is personal burns away and what is left is the “nugget of pure truth” in the art. This is the ideal state in which everything is consumed in the in tensity and truth of one’s art. The narrator skillfully leads the reader through one of the most important works of feminist literary history to d ate. Themes, Motifs & SymbolsThemesThe Importance of MoneyFor the narrator of A Room of One’s Own, money is the primary element that prevents women from having a room of their own, and thus, having money is of the utmost importance. Because women do not have power, their creativity has been systematically stifled throughout the ages. The narrator writes, “Int ellectual freedom depends upon material things. Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And women have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time . . .” She uses this quotation to explain why so few women have writ ten successful poetry. She believes that the writing of novels lends itself more easily to frequent starts and stops, so women are more likely to write novels than poetry: women must contend with frequent interruptions because they are so often deprived of a room of their own in which to write. Without money, the narrator implies, women will remain in second place to their creative male counterparts. The financial discrepancy between men and women at the time of Woolf’s writing perpetuated the myth that wom en were less successful writers.The Subjectivity of TruthIn A Room of One’s Own, the narrator argues that even history is subjective. What she seeks is nothing less than “the essenti al oil of truth,” but this eludes her, and she eventually concludes that no such thing exists. The narrator later writes, “When a subject is highly controversial, one cannot hope to tell the truth. One can only show how one came to hold whatever opinion one does hold.” To demonstrate the idea that opinion is the only thing that a person can actually “prove,” she fictionalizes her lecture, claiming, “Fiction is likely to contain more truth than fact.” Reality is not objective: rather, it is contingent up on the circumstances of one’s world. This argument complicates her narrativ e: Woolf forces her reader to question the veracity of everything she has presented as truth so far, and yet she also tells them that the fictional parts of any story contain more essential truth than the factual parts. With this observation she recasts the accepted truths and opinions of countless literary works.MotifsInterruptionsWhen the narrator is interrupted in A Room of One’s Own, she generally fails to regain her original concentration, suggesting that women without private spaces of their own, free of interruptions, are doomed to difficulty and even failure in their work. While the narrator is describing Oxbridge University in chapter one, her attention is drawn to a cat without a tail. The narrator finds this cat to be out of place, and she uses the sight of this cat to take her text in a different direction. The oddly jarring and incongruous sight of a cat without a tail—which causes the narrator to completely lose her train of thought—is an exercise in allowing the reader to experience what it might feel like to be a woman writer. Although the narrator goes on to make an interesting and valuable point about the atmosphere at her luncheon, she has lost her original point. This shift underscores her claim that women, who so often lack a room of their own and the time to write, cannot compete against the men who are not forced to struggle for such basic necessities.Gender InequalityThroughout A Room of One’s Own, the narrator emphasizes the fact that women are treated unequally in her society and that this is why they have produced less impressive works of writing than men. To illustrate her point, the narrator creates a woman named Judith Shakespeare, the imaginary twin sister of William Shakespeare. The narrator uses Judith to show how society systematically discriminates against women. Judith is just as talented as her brother William, but while his talents are recognized and encouraged by their family and the rest of their society, Judith’s are underestimated and explicitly deemphasi zed. Judith writes, but she is secretive and ashamed of it. She is engaged at a fairly young age; when she begs not to have to marry, her beloved father beats her. She eventually commits suicide. The narrator invents the tragic figure of Judith to prove that a woman as talented as Shakespeare could never have achieved such success. Talent is an essential component of Shakespeare’s success, but because women are treated so differently, a female Shakespeare would have fared quite differently even if she’d had as much talent as Shakespeare did.SymbolsA Room of One’s OwnThe central point of A Room of One’s Own is that every woman needs a room of her own—something men are able to enjoy without question. A room of her own would provide a woman with the time and the space to engage in uninterrupted writing time. During Woolf’s time, women rarely enjoyed these luxuries. They remained elusive to women, and, as a result, their art suffered. But Woolf is concerned with more than just the room itself. She uses the room as a symbol for many larger issues, such as privacy, leisure time, and financial independence, each of which is an essential component of the countless inequalities between men and women. Woolf predicts that until these inequalities are rectified, women will remain second-class citizens and their literary achievements will also be branded as such.。

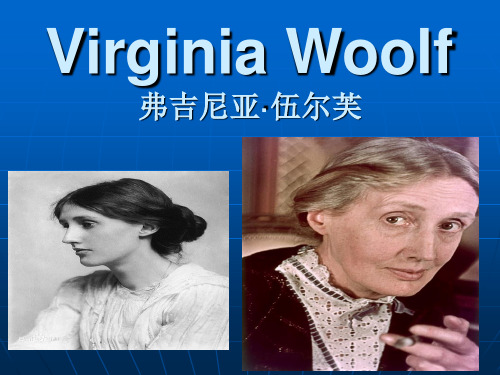

Virginia Woolf 1882 - 1941Virginia Woolf was born Adeline Virginia Stephen in London and educated at home by her father, the biographer Sir Leslie Stephen. She suffered a number of early shocks, including sexual abuse by her half-brother and the death of her mother when she was in her teens. Throughout her life she was subject to mental breakdowns of varying intensity.In 1905, after her father's death, Woolf and her artist sister, Vanessa, lived with their 2 brothers in a house in Bloomsbury which became the headquarters of the so-called Bloomsbury Group. This collection of artists, writers and intellectuals, generally modernist in outlook, were chiefly united by a strong reaction against the preceding Victorian Age. The group included, amongst others, writer E M Forster, biographer Lytton Strachey andpainters Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant.In 1912, Woolf married a member of the group, the political theorist Leonard Woolf, with whom she founded the Hogarth Press in 1917. After publishing 2 realistic novels, she developed a more experimental approach with her third book, Jacob's Room(1922), based on the life of her brother Toby, who had died tragically in 1906.Her next novel, Mrs Dalloway(1925), presenting the thoughts and inner lives of several groups of people in the course of a single day, broke new ground with the stream of consciousness technique pioneered by James Joyce in Ulysses (1922). To the Lighthouse(1927) showed great technical mastery, with a form tightly organized through the use of recurrent images and a restricted time frame. In The Waves (1931), she again recorded the stream of consciousness of her creations, invitingthe reader to inhabit the minds of her 6 characters from childhood to old age.In 1928, Woolf published a historical fantasy, Orlando, an imaginative analysis of gender, identity and creativity. "In every human being," she later wrote, "a vacillation from one sex to the other takes place". Covering a huge time span, Orlando also made use of elements taken from the life and family history of her friend and lover Vita Sackville-West.In her long essay A Room of One's Own (1929), Woolf turned her attention to the cause of women's rights, especially the obstacles that have hindered women writers. Most literature, she claimed, had been "made by men out of their own needs for their own uses".Woolf wrote some fine criticism, notably The Common Reader(1925), and her posthumously published diaries and correspondence shed much light on her lifeand work. Dogged throughout her life by a form of hypomania or manic depression, she committed suicide by drowning in 1941.KEY WORKS INCLUDE:Jacob's Room (1922)Mrs Dalloway (1925)The Common Reader (1925)To the Lighthouse (1927)Orlando (1928)A Room of One's Own (1929)The Waves (1931)Between the Acts (1941)弗吉尼亚·伍尔芙(Virginia Woolf,或译弗吉尼亚·伍尔夫,1882年1月25日-1941年3月28日)。

英国女作家,被誉为二十世纪现代主义与女性主义的先锋。

两次世界大战期间,她是伦敦文学界的核心人物,同时也是布卢姆茨伯里派(Bloomsbury Group)的成员之一。

最知名的小说包括《戴洛维夫人》(Mrs. Dalloway)、《灯塔行》(Tothe Lighthouse)、《雅各的房间》(Jakob's Room)。

弗吉尼亚·伍尔芙(Virginia Woolf?1882年1月25日—1941年3月28日)。

英国女作家,批判家,意识流小说的代表人物之一。

《墙上的斑点》是她第一篇典型的意识流作品。

(被认为是二十世纪现代主义与女性主义的先锋之一。

在两次世界大战期间,伍尔芙是伦敦文学界的核心人物,她同时也是布卢姆茨伯里派(Bloomsbury Group)的成员之一。

其最知名的小说包括《戴洛维夫人》(Mrs. Dalloway)、《灯塔行》(To the Lighthouse)、《雅各的房间》(Jakob's Room)。

复杂的家庭背景,这个9口之家、两群年龄与性格不合的子女经常发生一些矛盾与冲突。

而伍尔芙同母异父的两位兄长对她的伤害给她留下了永久的精神创伤。

1895年母亲去世之后,她第一次精神崩溃。

后来她在自传《存在的瞬间》(Moments of Being)中道出她和姐姐瓦内萨·贝尔(Vanessa Bell)曾遭受同母异父的哥哥乔治和杰瑞德·杜克沃斯(Gerald Duckworth)的性侵犯。

昆汀贝尔认为,弗吉尼娅的神经错乱和自杀前的幻听,和弗吉尼亚少女时期遭受的精神创伤导致无法愈合的伤口有关。

事实上,弗吉尼亚成人后非常厌恶性生活,更不愿生儿育女,对于同性的依恋甚至一度成为她感情世界里的重心。

诚然对于布鲁姆斯伯里文化圈里复杂多变的情感关系,并不能以常人的眼光等闲看待,即便如此,弗吉尼亚的情感状态依然被认为是出格的。

她不可救药地依恋着姐姐瓦奈萨,甚至采用一种最为出人意料的极端方式——和姐夫克莱夫调情,并以其作为自己的感情替身或者说傀儡。

弗吉尼亚和瓦奈萨,在布鲁姆斯伯里文化圈,始终是被关注的焦点,不论生前还是死后,除了她们的艺术才华,还有她们的生活隐私。

1904年她父亲莱斯利·斯蒂芬爵士(Sir Leslie Stephen,著名的编辑和文学批评家)去世之后,她和瓦内萨迁居到了布卢姆斯伯里(Bloomsbury)。

后来以她们和几位朋友为中心创立了布卢姆茨伯里派文人团体。

她在1905年开始职业写作生涯,刚开始是为《泰晤士报文学增刊》撰稿。

在某种程度上说,弗吉尼亚是上帝的弃儿,母亲、父亲相继病逝,是她难以承受的打击。

她的小说《达洛威夫人》中即充满了对病态幻觉的真实生动的描绘,可以说是她的精神写照。

弗吉尼亚不幸的生活经历,使她如含羞草一般敏感,又如玻璃般的易碎,她是优雅的,又是神经质的,一生都在优雅和疯癫之间游走。

有人这样描述弗吉尼亚,准确地把握住她的精神气质:“她的记忆有着隐秘的两面——一面澄明,一面黑暗;一面寒冷,一面温热;一面是创造,一面是毁灭;一面铺洒着天堂之光,一面燃烧着地狱之火。

”1915年,她的第一部小说《远航》出版,其后的作品都深受评论界和读者喜爱。

大部分作品都是由自己成立的“贺加斯岀版”推岀。

伍尔夫夫妇搬到Hogarth House. 1917 伍尔夫夫妇买下一架二手的印刷机,在家中的地下室建立了霍加斯(Hogarth)出版社。

(该出版社后来出版了包括艾略特、凯瑟琳·曼斯菲尔德、弗洛依德在内的作家作品,并且出版了伍尔夫的所有作品。