VIEWS ON EQUIVALENCE

- 格式:dps

- 大小:108.50 KB

- 文档页数:20

等效原理与商标词的翻译【Abstract】Translation of trade mark words is a kind of intercultural communication. The equivalence principle in translation is an important instructive theory for the translation of trade mark words. This paper lists a large quantity of translation examples of trade mark words,aiming at a study and analysis of the translation of trade mark words from the views of equivalence principle and cultural difference,and expecting to improve the translation of trade mark words.【Key words】Equivalence principle;Cultural difference;Translation methods0 IntroductionGenerally speaking,a trade mark word represents the image and reputation of its product. Consumers can distinguish the quality,specification and characteristic of a certain kind of commodity by using a trade mark word. According to the point of views of equivalence principle,the versions should achieve a perfect combination of sound,form and meaning. Meanwhile,cultural obstacles in the receptor-language should be surmounted.1 Definition and Function of Trade Mark WordsA trade mark word is an important part of a trade mark that can be vocalized,including letters,words. Take “BMW”,“Haier” as examples,both of them are so called trade mark words because they can be read out.The functions of trade mark words are identifying products,promoting consumption and acquiring law protection. In addition,there are two other functions:providing information of products and circulating among consumers.2 A Study of Equivalence Principle2.1 Definition of Equivalence Principle“Equivalence” in translation is often defined as to use the equivalent text of the target language and replace the original text of the source language. Nida,an American translator,classified “equivalence” into “for mal correspondence and dynamic equivalence”.In his work Theory and Practice of Translation,Nida made a more detailed explanation about “dynamic equivalence”,which is also regarded as the definition of “equivalence principle”. Dynamic equivalence (equivalence principle)is therefore to be defined as “the degree to which the receptors of the message in the receptorlanguage respond to it in substantially the same manner as the receptors in the source language”.Equivalence principle focuses on the feeling of both the reader of translated text and the original readers toward the same text. However,those feelings should be generally but not absolutely the same. In a word,equivalence principle requests translators to consider the feeling of the reader of the translated text when translating trade mark words.2.2 Application of Equivalence Principle in Translating Trade Mark WordsThe application of equivalence principle in translating trade mark words includes commercial effect and texts’style. Generally speaking,the commercial effect is to promote the sales,and the effect on texts’style is to meet the linguistic custom and aesthetic appreciation of the target customers. And a good translation of trade mark word should be a perfect combination of sound,form and meaning.When “Clean&Clear” enters into Chinese market,it is translated as “可伶可俐”. It is a brand of daily-use cosmetics to nourish skin. Since most of the target consumers are female youth,the translation picks up Chinese word “伶俐” which is used to describe a pretty and beautiful girl. Furthermore,this translation holds the original name,sound and a balance form.Other successful English-Chinese translations are:“Jonson&Jonson”-“强生”;“Coca-Cola” -“可口可乐”. The Chinese-English translations are “星火英语”-“Spark English”;“号码百事通”-“Best Tone” and so on. All these trade mark words are translated by well applying the equivalence principle.3 Methods of Translating Trade Mark Words3.1 Literal TranslationThe method of literal translation means translating a certain trade mark word according to its literal meaning. It demands translators to find a proper and natural equivalent word in the target language to convey accurately the information of the original trade mark word. For example:Forget-me-not-勿忘我(perfume);Evening-in-Paris-夜巴黎(perfume);Pioneer-先锋(appliance). The Chinese trade mark words are:唐朝-Dynasty (wine);蜂花-Bee&flower (shampoo);钻石-Diamond (watch). This method of literal translation keeps the equivalent sense of the trade mark words’indication,association,social culture and aesthetic appreciation and provides the products’information.3.2 Transliteration with Meaning ImplicationThe method of transliteration with meaning implication means translating acertain trade mark word partially according to its pronunciation and partially according to a certain meaning in the target language. For example:Benz-奔驰(car);Canon-佳能(camera);afeguard-舒肤佳(soap);Pampers-帮宝适(diaper). The Chinese trade mark words are 四通-Stone(computer);格力-Gree (air-conditioner);快克-Quiker (medicine). The method of transliteration with implication not only remains the original beauty of the phonology,but also indicates the function and characteristics of the products.3.3 Creative TranslationThe method of creative translation means translating the trade mark words by making some adjustments on the basis of the original one to meet the needs of new customers. For example:Head&Shoulders-海飞丝(shampoo);7-UP-七喜(soft drink);Poison-百爱神(perfume). The Chinese trade mark words are:新飞-FRESTECH(refrigerator);宝龙-Powerlong;苏泊尔-Supor(pressure cooker). After creative translating these trade mark words,the translated ones remain the characteristic of the products and become more attractive and adaptable in the target language.3.4 A Comment on Some VersionsAccording to the analysis of the trade mark words translation,we realize the importance to translate a trade mark word well. And here,this paper elaborates some personal ideas about the re-translations of some trade mark words.“金龙”is a famous trade mark word of vehicles in China. Obviously,the literal translation “Golden Dragon” will not be popular among the English-speaking customers because the cultural differences about “dragon”. It is better to be translated as “Kinglong” which avoids the literal translation of “龙” and contains the connotation of kingship in the field of vehicles.“红豆”is a famous trade mark word in China. Usually,it is translated into “Hongdou” by Pinyin translation. However,this translation can not well convey the real connotation of “红豆” which is regarded as love beans in Chinese. It is better to stick to the Chinese tradition and literally translate it as “Love Beans” or “Red Beans”. Both “Love Beans” and “Red Beans” will attract those foreigners who are in terested in Chinese traditional cultures.4 ConclusionTranslation of trade mark words is an activity which conveys commercial information. So,equivalence principle should be a main principle of translation of trade mark words. No matter what methods are chose,the translator should pay attention to the equivalence principle and ensure that the translation is accepted by both foreign and original consumers.【References】[1]Towards a Science of Translation:Nida,E.A.[M]. Leiden:E.J.Brill,1964:67,159.[2]Theory and Practice of Translation:Nida,E.A. & Taber,C.R.[M]. Leiden:E.J.Brill,1969:25.[3]肖辉,陶玉康.等效原则视角下的商标翻译与文化联想[J].外语与外语教学.2000(3).。

药理学名词解释归纳药理学是研究药物与机体之间相互作用规律及其机制的一门科学。

药物是能改变或查明机体的生理功能及病理状态,用以预防、治疗及诊断疾病的物质。

药动学研究机体对药物的处置过程,即药物在机体的作用下发生的动态变化规律。

药效学研究药物对机体的作用及作用机制,即机体在药物影响下发生的生理、生化变化及机制。

售后调研是在社会人群大范围内继续进行受试药物安全性和有效性评价,在广泛长期使用的条件下考查疗效和不良反应,该期对最终确定新药的临床价值有重要意义。

药效学中,药物作用指药物与组织细胞之间的初始作用,药理效应指继发于药物作用之后的组织细胞原有功能的改变。

兴奋是能使机体原有生理、生化功能加强的作用,抑制是能使机体原有生理、生化功能减弱的作用。

多数药物是通过化学反应而产生药理效应,这种化学反应的专一性使药物具有特异性。

药物只对某些组织器官发生明显作用,而对其他组织作用很小或无作用,称为选择性。

药物作用的结果有利于改变病人的生理生化功能或病理过程,使患病机体恢复正常,称为疗效。

如果用药目的在于消除原发致病因子,彻底治愈疾病称对因治疗,或称治本;如果用药目的在于改善疾病症状,减轻疾病的并发症称对症治疗,或称治标。

不良反应是凡不符合用药目的或给病人带来痛苦与危害的反应,多数不良反应是药物固有效应的延伸。

副反应是药物在治疗剂量时出现的与治疗目的无关的作用,亦称副作用。

副反应是药物本身固有的,是因药物选择性低而引起的,一般不严重,难避免。

药物在剂量过大、用药时间过长或机体敏感性过高时,会对机体产生危害性反应,称为毒性反应。

这种反应一般比较严重,但是可以通过预知和避免来降低风险。

停药后,药物在血液中的浓度已经降至阈浓度以下,但仍会残留药理效应,称为后遗效应。

另外,长期使用某些药物后突然停药,可能会导致原有病情加重,这种现象被称为停药反应或回跃反应。

过敏特质的病人对某些药物可能会引起异常免疫反应,这种反应被称为变态反应或过敏反应。

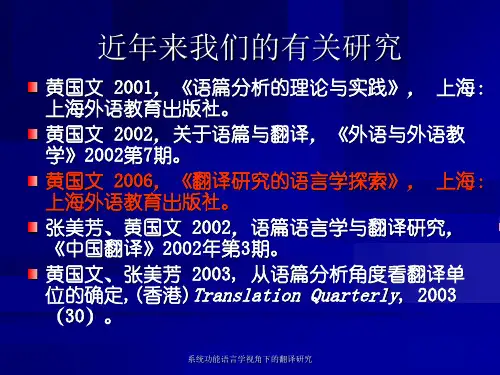

篇章对等的例子【篇一:篇章对等的例子】从篇章对等的角度研究翻译维普资讯第26卷第2期2005年2月湖南科技学院学报JournalofHunanUniversityofScienceandEngineeinrgVO1.26NO.2Felb.2005从篇章对等的角度研究翻译庞慧英(福建师范大学外国语学院,福建福州350007)要:本文主要论述了从篇章的角度去研究翻译的重要性及其策略,即从文体角度,两种语言在篇章组织结构上的异同,以及从源语和目的语的篇章的粘连?  ̄(cohesion)和连贯?  ̄(coherence)等方面去研究翻译,从而可以使目的语和源语在文体,写作风格和主旨等方面取得对等的效果。

关键词:文体;篇章结构;粘连性和连贯性中图分类号:H059文献标识码:A文章编号:1671-9697(2005)02-0120—02翻译的过程是个单向性的从源语到目的语转化过程中某个女儿的合法的财产看待。

(以上两例为王佐良译)从以上译文可以看出王佐良的翻译重点是再现了原文(Catford,1965:20)。

翻译的任务就是找出一个与源语语言项目在某一特定语境中篇章对等的目的语项目。

在传统的翻译过程中,我们几乎总是从语音,词汇,语法等方面的对等进行翻译(即up—down的译法)。

按照这种方法进行翻译虽的叙事风格,取得了与原文对等的语言效果。

“ 对于翻译这样经典性的叙述文体小说,翻译应当向原著倾斜,以求得内容和形式的一致” 。

(冯庆华2001:57)而对于政治作品的翻译对译者的要求又有所不同。

下面以罗斯福第一次就任美国总统时发表的演说为例来说明一Yetourdistresscomesfromnofailureofsubstance.Wearestrickenbynoplagueoflocusts...Naturesitllofersherbountyndahumanefortshavemulitplideit.然可以使目的语在词和句子与源语对等,但很容易使目的语和源语在文体,写作风格和主旨等方面发生偏差。

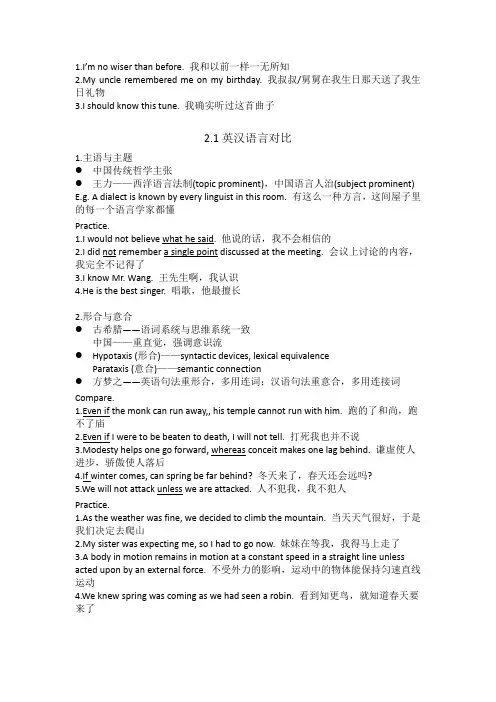

1.I’m no wiser than before. 我和以前一样一无所知2.My uncle remembered me on my birthday. 我叔叔/舅舅在我生日那天送了我生日礼物3.I should know this tune. 我确实听过这首曲子2.1英汉语言对比1.主语与主题●中国传统哲学主张●王力——西洋语言法制(topic prominent),中国语言人治(subject prominent)E.g. A dialect is known by every linguist in this room. 有这么一种方言,这间屋子里的每一个语言学家都懂Practice.1.I would not believe what he said. 他说的话,我不会相信的2.I did not remember a single point discussed at the meeting. 会议上讨论的内容,我完全不记得了3.I know Mr. Wang. 王先生啊,我认识4.He is the best singer. 唱歌,他最擅长2.形合与意合●古希腊——语词系统与思维系统一致中国——重直觉,强调意识流●Hypotaxis (形合)——syntactic devices, lexical equivalenceParataxis (意合)——semantic connection●方梦之——英语句法重形合,多用连词;汉语句法重意合,多用连接词Compare.1.Even if the monk can run away,, his temple cannot run with him. 跑的了和尚,跑不了庙2.Even if I were to be beaten to death, I will not tell. 打死我也并不说3.Modesty helps one go forward, whereas conceit makes one lag behind. 谦虚使人进步,骄傲使人落后4.If winter comes, can spring be far behind? 冬天来了,春天还会远吗?5.We will not attack unless we are attacked. 人不犯我,我不犯人Practice.1.As the weather was fine, we decided to climb the mountain. 当天天气很好,于是我们决定去爬山2.My sister was expecting me, so I had to go now. 妹妹在等我,我得马上走了3.A body in motion remains in motion at a constant speed in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force. 不受外力的影响,运动中的物体能保持匀速直线运动4.We knew spring was coming as we had seen a robin. 看到知更鸟,就知道春天要来了3.树状与竹状E.g. The boy, who was crying as if his heart would break, said, when I spoke to him, that he was very hungry because he had had no days for two days. 男孩哭的心都快碎了,当我问及他时,他说饿极了,有两天没吃了Practice1.The moon is so far from the earth that even if huge trees were growing on the mountains and elephants were walking about, we could not see them through the most powerful telescope which have been invented. 月球离地球十分遥远,哪怕月球上长着参天大树,哪怕大象在上面行走,我们也无法用现有最高倍的望远镜看到他们2.Upon his death in 1826, Jefferson was buried under a stone which described him as he had wished to be remembered as the author of Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom and the father of the University of Virginia. Jefferson逝于1826年,遵照其遗愿,,他的墓碑上写着:《解放宣言》和《弗吉尼亚州信教自由》的作者,弗吉尼亚州大学创始人之墓4.静态与动态英语——静态语言,喜用名词和介宾汉语——动态语言,动词可在句中充当各种成分Practice.1.Admittance Free. 免票/费/券入场2.Out of Bounds. 游客止步3.No Admittance Except on Business. 闲人免进4.Danger of Death——High Voltage! 高压危险5.Party officials worked long hour on meagre food, in old caves, by dim lamps. 党员干部吃的是粗茶淡饭,住的是老旧的窑洞,点的是昏暗的油灯,仍长时间的工作6.What film will be on this evening? 今晚有什么电影上映?7.He walked around the house with a gun. 他持着枪,绕着屋子走8.A study of that letter leaves us in no doubt as to the motives behind it. 仔细研究了那封信,我们明确了它背后的动机9.The very first sight of her made him fall in love with her. 他对她一见钟情2.2英汉文化对比1.文化心理①颜色:a fair-haired girl 红人,受宠的人,金发女郎②动物:Four Asian Tigers 亚洲四小龙a lion in the way 拦路虎;a lion’s den 虎穴2.文化价值“老”:中文表尊敬,E.g.张老;英文有冒犯的意思3.风俗习惯“吃了吗?”——How are you?2.3英汉思维对比1.思维方式①时间:不到6岁(中-前后,英-above,under)②天人合一vs天人对立(中-人作主语,英-物作主语)2.正反与虚实①正反E.g. I have read your article, but I expect to meet an older man. 我读过你的文章,但没想到你这么年轻A seaman knows that sea is all-powerful and can, under certain circumstances, d estroy man and the product of his brain and hand, the ship. 水手们都知道,大海的威力是势不可挡的,在某些情况下,它能把人及人所制造的船只统统摧毁掉"Mine!Mine!"They would shout at the pretty rainbows that are down to the ear th, seeming never very far away. 他们会冲着那从天际弯弯地挂向地面的,看起来好像伸手可及的美丽的彩虹,大声呼喊"彩虹是我的!是我的!"Exception.He was not displeased with her honesty…it took a certain amount of experience in life, and courage, to want to do it quite that way. 他对于她的直率并没有感到不快…有点生活经验,又有点胆量的人才敢这么做Practice.1.Memory, as time goes on, is a selective thing. 随着时间的流逝,记忆会使人忘却一些事情2.The subversion attempts proved predictably futile. 不出所料,颠覆活动证明毫无意义3.The guerrillas would fight to death before they surrendered. 游击队员宁可战死,也不投降4.We believe that the younger generation will prove worthy our trust. 我们相信年轻一代不会辜负我们的信任5.It was beyond his power to sign such a contract. 他无权签订这种合同②虚实E.g. Wisdom prepares for the worst, but folly leaves the worst for the day it comes. 聪明人防患于未然,愚蠢者临渴方掘井Because of the circuitous and directional flow of waterways, railways often have energy advantage over barges. 由于河道迂回曲折且水流具有方向性,铁路运输相对于水运而言,常常具有节能优势Practice.6.The customer-made object, now restricted to the rich, will be within everyone’s reach. 这种定制产品如今仅限于富人享受,而将来人人都能买得起7.In the end things will mend. 车到山前必有路/船到桥头自然直8.He wanted to learn, to know and to teach. 他想要学习,掌握/增长知识,也愿意把知识教给别人9.These problems are too complicated to be explained clearly in a few words. 这些问题实在太复杂/盘根错节,三言两语说不清楚10.Rockets have found application for the exploration of the Universe. 火箭已用于探索宇宙3.褒贬与曲直①褒贬E.g. The irony is that Mrs. Gandhi presides over a nation with a highly promising long-term potential but which is saddled with equally difficult current problems.颇为耐人寻味的是,从长远的观点来看,甘地夫人掌管的国家是大有希望的,但目前却有着难以克服的困难She was vexed by the persistent ringing of the phone. 她被没完没了的电话搞得心烦意乱All the inventors have a restless mind. 所有的发明家都有一个活跃的头脑Practice.1.He was a man of integrity, but unfortunately he had a certain reputation. I believe the reputation was not deserved. 他是一个正直的人,名声却平平。

SKOPOSTHEORIE: A REVOLUTION CELEBRATEDby Sergio ViaggioI was asked to write this collaboration as I was retiring from the UN after thirty-one years, in the middle of moving a few pieces of furniture to my new tiny pied-à-terre in Vienna and with everything else - including my books - on its way to Buenos Aires.I cannot, therefore, hope to come up with anything resembling a scholarly piece, but I simply could not refrain from taking part in this homage - oh so well deserved! - to one of the most influential translation theorists of our time. I do beg, then, your indulgence, dear reader. I hope I will be able to make it worth your while anyhow.As a young student, I was thoroughly immersed in Russian translation theory (Fedorov, Barkhoudarov, Retzker, Schweizer, Komissarov, Etkind and the rest), which, pioneering as it was at the time (1970), had not quite hit the functionalist nail on its head. Yes, it was acknowledged that different types of texts required - or rather allowed for - different approaches; but this was an ugly necessity of reality which theory was not altogether capable of accounting for.My eye-opener was Nida (1964), with his demolishing question: a good translation… for whom? Here was a liberating view: The Lord had written his word for his people, but had his people been not the Jews back then, he would have written it differently. The translator's task became, thus writing it for a new readership - or, more often than not, illiterate audience, as were, indeed, its original addressees! - in a way that they will be able to understand it the way He meant it and be moved by it the way He meant his creatures to be moved. A mighty task, rewriting God's word for people who could not read, and, to boot, had never seen a camel, and not just "translating" it. An onerous responsibility, second guessing the Creator and an even more onerous one re-inventing His word. With all his new liberty, however, Nida's translator was simply an empowered scribe: His mission was to make God's word understood as intended. The myriad manipulations (the "handshake all around" substituting for the "kiss on the cheek" so derided by Meschonic) were due to the new flock's specific "hermeneutic package1." Nevertheless, two things were said - at least to me - for the first time: it is not enough for the translator to re-say, and it is not enough for the new interlocutor merely to have understood. What really matters is what happens as a consequence of the new interlocutor's having understood - the effect that comprehension has upon him. The Bible scholar and the theologian "listen" to the word of God with different ears and expectations to those of the rank and file members of the flock or, more importantly, those of the stray sheep whose salvation depends on their being touched by His word. The translator's task is, thus, to re-speak the Word (that Word, and not any other - all of it, and not simply selected utterances), and, by speaking it, to touch the new interlocutors as God himself is supposed to have touched his. One Word - as many valid translations as potential subjects of evangelisation insofar as the Word remains the same.But if the "handshake" and the "kiss" are both possible renditions of the same Word, what is the Word? What is it that a translator must leave intact? Nida never calls it by what I think is its name: not a representation, based on the immediate1 This is how that other great one, Mariano García Landa (1990, 1995 and 1998), aptly calls the baggage of linguistic and encyclopaedic knowledge, social and individual experience, mores and habits that the subjects bring to bear when understanding each other.comprehension of propositional content and referential meaning, but a metarepresentation. The kiss and the handshake are meant to produce different representations that, once processed and/or filtered through the subject's hermeneutic package and ability, would presumably produce the same metarepresentation. The Lord, after all, speaks through parables2.Indeed. With Nida, the relationship between formal - including semantic -features of texts ceases to be the yardstick of equivalence, and, therefore, of fidelity3. Again, Nida never makes it explicit, but the relationship is not between original and translated texts, but between intended and achieved metarepresentations - i.e. between mental "states4." From then on, looking for "textual" equivalence as an inherent attribute of original/translation pairs, an attribute, moreover, independent from the intention that has motivated the speaker to produce his text and the comprehension that his text and/or its translation eventually produce, becomes moot - which explains that so many theoreticians end throwing up their arms in the air and the concept down the drain. What Nida realises without actually realising is that "equivalence" however defined is not an attribute of a translated text but a consequence of translating. I do not say Y because the original says X, but rather, I say Y because this is what I think I better say in order for my interlocutor to understand - i.e. to metarepresent - something relevantly similar or analogous to what the original author intended his interlocutor to understand by X, or, alternatively (it all depends on my skopos, except that nobody had put it black on white), because this is what the original interlocutor ended up understanding by processing X5. There is, therefore, no necessary a priori formal (semantic or other) correspondence between X and Y, between the original "kiss" and my translation's "handshake".In 1975 I became an interpreter and soon thereafter became acquainted with the views of Danica Seleskovitch (1964, etc.), who started looking at what happens to an original in consecutive interpretation. Again, lots of things, none of them kosher from the standpoint of traditional concepts of equivalence. The thing to trans-late was sense, meaning meant, so that it would be understood by the new interlocutor. The author's word became as detached from its original manifestation as the Lord's. Whether deverbalised sense is actually possible is moot: the sheer fact that it can remain (more or less, and presumably) intact despite the fact that not a morpheme of the original may remain ought to be enough empirical proof that sense is not verbalisation-dependent. Again, no necessary correspondence between X and Y.2 I have called these two superimposed layers of meaning meant direct and indirect intended sense; the latter to be distinguished from deep sense, which is no meant, but nevertheless understood despite the very fact that it was not meant. In the case of a parable - as in every other case of figurative speech - indirect intended sense is understood via a metarepresentation based on the understanding of sense directly intended. Understanding direct sense in no way guarantees a grasp of indirect intended sense: some people simply don't get it: not everybody understands every single allegory (Viaggio 1999 an d, especially, 2004).3 A text's semantics is not part of its content, but that content's form. Semantic form and propositional content are not to be confused.4 Or, as Osimo (2001) would eventually put it, between mental - as opposed to written or spoken - texts of which written or oral texts are but intermediary Peircean interpretants.5 Which is normally the intention (skopos!) behind malicious quotation: whatever the original speaker meant to say, this is what he actually said. As I put it, objective sense(sense as would normally be interpreted by a typical interlocutor in a typical situation) is made to prevail over intended sense (i.e. sense as the speaker meant to convey). In normal intercourse it is intended sense that counts, in adversarial argument, objective sense carried the day: Fie the accused who misspeaks!At the end of the 80s, two splendid books came simultaneously into my hands that made me cast a completely new glance on equivalence: Zina Lvovskaya's The Theoretical Problems of Translation and Albrecht Neubert's Text and Translation. For the first time, I became aware of the overriding importance of the communicative situation and the consequent hurdle that displaced situationality posed for the translator. Lvovskaya explained that the basic problem lies in the distinction between meaning (linguistic, objective) and sense (extralinguistic, subjective). Sense is the end result of the motivation and purposes of the subject’s communicative activity in a specific situation. Two subjects will hardly react identically in the same situation, but neither the absence of bi-univocal correspondence between meaning and sense nor the latter’s subjective nature will stand in the way of communication if both interlocutors share the necessary extralinguistic knowledge. The best assurance of sense comprehension is a communicative situation shared by both interlocutors and their belonging to the same culture. However, since there are no two subjects who share the same knowledge, experience or values, sense as intended by a speaker will be more or less different to sense as comprehended by each of his interlocutors, which is a general feature of verbal communication. No message is understood, then, perfectly and in its entirety. A key door was opened before me: communication begins and ends in sense - i.e. in the minds of the interlocutors: what counts in the end is not what the translator -or, for that matter, the author- have said, but what the new interlocutor understands, and such comprehension is always situation-specific. The fundamental problem of translation lies, therefore, not so much in the mismatches between languages, but between the experience and knowledge that the new interlocutors activate when trying to understand in their new situation.Later on, in the early 90s, I chanced upon Spe rber and Wilson’s Relevance Theory (Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995) and, more specifically, its adoption by Gutt (1990 and 1991), who held that it is sufficient to explain translation, which thus no longer requires a theory of its own. According to Sperber and Wilson, utterances can be used as representations in two basically different ways: 1) an utterance may propositionally resemble a state of affairs in the world - in which case language is used descriptively, and 2) an utterance may propositionally resemble another utterance - in which case language is used interpretively. In the first instance, the utterance describes a (real or imaginary) state of affairs in the world, in the second - it reproduces, as it were, the propositional content of a previous utterance, or, if you wish, of a previous description of a (real or imaginary) state of affairs in the world. In other words, the “truth” - and, eventually, relevance - of a descriptive utterance is, basically, a function of the state of affairs it describes and the way it describes it, whilst that of an interpretive utterance lies in the way it propositionally resembles another utterance. This leads Gutt to define translation as second-degree interpretive use: A translator says, by means of an utterance in the target language, what the original speaker communicated by means of an utterance in the source language - the translated utterance is thus supposed interpretively to resemble the original one. It is assumed, therefore, that a translated utterance interpretivley resembles its original. Parallel texts - viz., the different language versions of an owner’s manual, in which language is used descriptively to “describe” the device and the correct way to use it - would not be translations (regardless of the fact that they may have been arrived at by translators basing their own descriptions on the description verbalised in the sourcelanguage)6. The definition was theoretically tight, but it posed a practical problem: According to it, most translators do not translate at all, and most translated texts are not really translations.All these scholars empowered translators and interpreters in a new, refreshing and fearsome way: Gone was the safe haven of the original as the last and ultimate alibi for all manner of infelicities. Semantic equivalence was demolished as the last refuge of translating scoundrels. From now on, translators and interpreters were responsible not only for having understood, but for what really counts in the end: making themselves understood. Still, both Nida's, Lvovskaya's, Neubert's and Gutt's translator and Seleskovitch's interpreter were beholden to the original's intent and meaning. If there was no longer a necessary correspondence between forms, there still had to be strict correspondence between meaning meant and meaning newly understood. The mediator's freedom and prowess were strictly bounded by it. The translator's addressees were, for all practical purposes, seen as passive subjects, whose sole purpose was to understand and be affected by meaning as meant - and then to manage on their own. Their interests, motivations and, generally speaking, stakes in understanding were of no concern to the mediator: His was not to help communication, but simply to make it possible.And then I came across skopostheorie. It took the 1996 Spanish translation for me to be able to read Reiss and Vermeer's classic, but by that time I was familiar enough with the concept to embrace it wholeheartedly. Regardless of the intention behind it, an original was now a sheer "information offer", a smorgasbord of meaning meant from which an interlocutor would necessarily eat as much or as little as he pleased. I do not mean the comparison to be facetious: What else is a newspaper? Who reads absolutely every word in it? Only intelligence agents - and not precisely out of a keen interest in the price of real estate coupled with an addiction to football and a morbid curiosity for gossip, gore and mayhem: Their skopos is anything but reading the news! Has anybody other than a few unquenchable bibliophiles read the Book of Numbers, for that matter? Skopos theorists are the first ones to realise - and boldly state - that an interlocutor's interest may not coincide with that of the speaker's, much less the interests of someone reading a translation or, more crucially, a third party commissioning it, and that a professional translator must take this into account. It is, in other words, not enough for a translation interpretively to resemble an original for it to be useful to its reader - its comprehension had to product relevant contextual effects7, the production of which is not necessarily linked to interpretive resemblance. Unlike previous theoreticians, Reiss and Vermeer do not ask themselves, then, how a translator can convey to different intended readers all of, and nothing but, the propositional (i.e. "informative") content of an original or, even, its larger intended meaning, but why understanding a translation or having it understood by others actually serves the commissioner's purpose - what is worth his while to process (if he is the intended interlocutor) or have someone else process (if he is the author or a third party) and towards what end. Although not brought in explicitly, Relevance Theory loomed large behind the approach, except that now emphasis was made decisively on relevance for the users (mind you, not necessarily the readers) of 6On the other hand, a text whose “truth” lies exclusively on its propositional resemblance to the original instructions - say, in order to prove their aptness or ineptness before a court of law - would, indeed, be a translation.7 Reiss and Vermeer, of course, do not put it in these relevance-theoretical terms, but this is exactly what I take them to mean.translations, as opposed to the producers of originals - with which the translator's orientation became forward- rather than backward-looking: Do not think only and so much what you can do for the author, but what you can do for your client; do not think only and so much what the original author meant to say, but what the new reader will end up understanding; do not think only and so much what was the author's purpose in saying, but the new interlocutor's in understanding; in short, think first of all why someone has bothered to request this text to be translated and is ready to pay you for it.Still, it behoved the commissioner to present the translator with his brief. The translator was, in principle, beholden to it as he has previously been beholden to original meaning. In its initial concept, in other words, Skopostheorie empowered not so much the translator as the commissioner: the author dethroned, it was he who picked up the sceptre - after all, he paid the piper. Yet, oftentimes, commissioners are not even aware that their translator needs such briefs in order to produce a translation as closely tailored to their needs. Also, blissfully unaware of the workings of communication, many commissioners produce the wrong briefing: they do not really know what is good for them - as is very often the case with lay users of any service. As with any other professional service provider, it is then up to the translator to advise his clients, or simply to second-guess them: A professional service provider knows when to bother his client with questions (some of which he will not be in a position to answer, anyhow), and when just go ahead and do what, in his professional judgement, is best for him. Here, the translator is finally fully empowered. In this new light, then, Skopostheorie empowers the professional translator as a true professional: someone who must know best - and act accordingly. His competence is thus expected to go well beyond understanding texts in the original and being able to reproduce their prepositional content, and imitate or manipulate their form in the target language. Indeed, a translator's linguistic competence must be such as to be able to produce all manner of re-writings, in different styles and registers, catering to different tastes and dispositions and abilities to understand, serving al manner of different purposes. And indeed, his bi-cultural competence must be such as to foresee and overcome, or at least palliate, cultural obstacles to comprehension. But this dual competence is itself at the service of an overriding metacompetence: that of determining and taking stock of the metacommunicative purposes8 of the different parties to communication and to choose from his performing arsenal the best tools and the best way to serve those of the commissioner who has hired him. His is still a service, but a comprehensively expert one. If the client's brief is inept, it behoves the truly professional translator to help him see the light. If the client insists, of course, the translator has the same choices as a physician whose patient refuses to heed his advice: "cheat", throw up his arms in despair and make the best of it, or send him packing.It sounds dauntingly mercenary and, up to a point, it is: All services are provided for money and the motto is always very close to "the client is always right" or "we are there to please". Now, that a lawyer - and a damn good one, to boot - put all his expertise at the service of defending a serial killer is a fact that does not scare many people or puts legal and judicial systems into question. As a matter of fact, it is a necessary feature of fairness and justice that even a serial killer should be able to benefit from the best defence possible. Why should the public be aghast, then, at the possibility of translators "manipulating" an original to further the ends of his author or, heaven forbid!, someone else? The misplaced joke that is omitted or changed in 8 For a full development, see Viaggio (2004).interpretation so as to make a speaker more effective (the speaker's skopos), the advertisement whose translation is not meant to convey the same meaning but to sell in the new medium (the commissioner's skopos), the sinister nazis turned marihuana smugglers in the first German dubbing of Hitler's Notorious so as not to ruffle the public's pragmatic feathers the wrong way (the commissioner's skopos as a vehicle for the larger skopos of the political powers-that-be, intent on glossing over an uncomfortable past), the adaptation of Gulliver's Travels or Robinson Crusoe (the translator's or the commissioner's skopos based on the intended addressees' interest and ability and their parents' and society's notion of what they may or may not, a nd should or should not read), the Contrat social emasculated of "those parts in which the author becomes delirious in matters religious" so as to get past Spanish censorship in pre-Revolutionary Argentina (the translators own political skpos), or the so-called Liberation Bible(again the translators' ideological and political skopos) are but haphazard examples of a practice as old as translation itself - except that nobody had dared speak its name! Something as evident as Columbus's or Brunelleschi's egg - that nobody had seen or said. This dealt the final kick to the dead horse of textual equivalence: a (good) translation was not required to be equivalent to its original, but coherent with it, and that coherence was not in and of itself but skopos-dependent: both the "kiss" and the "handshake" could make a translation coherent or incoherent with the Bible - it all depended on the kind of comprehension and effects sought. Did this mean that, in the end, anything goes?Peter Newmark (1982 and 1988) saw the dangers of Ivan Karamazov taking over: If there is no God author, how can translating humans tell right from wrong? Human free will is not to be trusted - let alone that of translators! Translation is about "truth", and there is no truth outside the word of the Author, even if His word is the user's manual for a toaster. Again, the simile is not facetious. Indeed, if anything the client wants, or if anything the translator thinks is good for him, goes, if every translator can claim that what others perceive as arbitrary manipulations, omissions, additions, infidelities, infelicities or outright mistakes are simply a matter of his skopos, then what is left for us to practice, teach and judge as translation? Left at that, Skopos risked becoming the new last refuge of translating scoundrels - including, now, those who cannot translate.Peter Newmark's ethical alarm was, then, well founded. Except that it was not a return to the Author that would save the day (authors can be pretty nasty specimens in their own right), but an ethical framework: a broad ring separating the dos from the don'ts - a framework to assess not only the accomplishment of specific skopoi, but those skopoi themselves. This Christiane Nord (1991) came up with: Loyalty. As any other professional service provider, a translator should do everything in his power to serve his client loyally. A translator is, in other words, first, loyal to his client, and next, and only in so far as required by his skopos, faithful to the original text.But, insisted Newmark, what ought a lawyer do if he knows his client to be guilty of a heinous crime? Do everything in his power to get him Scot free so that he can go on killing? What ethical compass is there to guide a translator across the Valley of Conflicting Loyalties? I submit that, as with every other profession worthy of its name and social status, it should be the profession itself. As an individual's ultimate loyalty as a social being ought to be to society, so does a professional (any professional) owe loyalty to his profession over and above any specific client or group of clients, a Hieronymic oath of sorts, as advocated by Chesterman (2001) - although I do not subscribe his concept of it. A profession - and this is, precisely, what distinguishes one from a sheer métier - to my mind, is the embodiment of society aspertains to a specific field of activity. Deontology is, after all, but the ethics of a profession - the ethical dos and don'ts of human beings qua physicians, lawyers - or translators. Which, incidentally, explains the main ethical and social difference between professional and non-professional practitioners. You may not like, or even deride, the Zukovski's phonetic acrobatics with Catullus, but you cannot question their right to try their hand at them: They did exactly what they set out to do - and brilliantly at that. Ditto Nabokov's stupendous semantic disembowelling of Pushkin's Eugene Oneguin. Or Sartre's bold modernising of Euripides. The non-professional translator decides the kind of service he wishes to render to whom. He is not and cannot be subject to professional retaliation (he can, of course, be burnt at the stake, as Tyndale and Diolet, except that not by fellow translators, but by the Grand Inquisitor, who can also burn astronomers like Giordano Bruno - and for that, he needs not know an iota about translation or astronomy). A translator who translates because he well damn pleases, in other words, is objectively free to translate as he well damn pleases: He is free to chose his own skopos, and all that translation scholars can do is assesses how well he has managed - or, more safely, simply describe it and write it down - and off - as historical fact. After all, as so many descriptivists have discovered, everything that goes… goes!The theoretical Pandora's box that this unexpected encounter of theory and practice made possible by Skopostheorie is momentous. If, rather than dodge the issue by defining translation as anything that is thought to be one (even if it is an original posing as a translation!) and thereby refusing to judge it on any relevant translatological grounds, we adopt Nida's, Lvovskaya's, Gutt's and Seleskovitch's approach and conceive of translation broadly as re-saying in a different language that which was said in the original one (regardless of how we further define "that which was said"), then Gutt is right: Skopostheorie, being undoubtedly a theory of what (good) translators actually do, paradoxically, is not a theory of translation. And if translation is not re-saying in the new language that which was said in the original one… then what on Earth is it? Vermeer and Reiss never actually say so, that I know, but they do show that (good) translators often - all too often for comfort - do not "translate," or, rather, do something more, something less and something other than "translating." Theirs, in other words, is not a theory of translation but of what people who produce "translations" do and of the texts thus produced, whatever one may call them9. Theirs is, at long last, a comprehensive theory of translation practice - the only kind of theory, I submit, that practising translations need.To sum up, then, if, within Gutt's definition of translation, Nida's dynamic equivalence and Seleskovitch's théorie du sens are empowering, by transcending a concept of translation as simply "re-saying" Skopostheorie is both empowering and emboldening: The (needless to say, good) professional translator - including, of course, the (good) professional interpreter - is the social agent with the knowledge, expertise and prowess to determine what counts as the best possible recreation or rendition (no longer a translation stricto sensu) of a given original in the specific social situation, for the specific metacommunicative purposes of a specific user or group of users, whether the author, the commissioner, or the intended or, even, unintended interlocutors. The translator (or interpreter) makes a series of socially transcendental professional decisions that go far beyond finding textual equivalents. To wit: a) The translator decides whether he accepts the originator's commission, b) 9 A daunting paradox that I think I have been able to solve in Viaggio (2004) - which I hope will finally find an English publisher.。

目的决定方法——功能翻译理论对翻译实践的启示Research on Idiom Translation from the Perspective of Functional EquivalenceI. IntroductionAn idiom is an expression which may be a word or a phrase that has figurative meaning―its implication, and idioms are heavily cultural-loaded. With their unique and strong linguistic and cultural features, they have long been considered as one of the most difficult parts in translation. An idiom consists of at least two words, of which the structure is usually stable and the meaning is unpredictable from its formation, that is, its true meaning is different from its literal meaning. Idioms reflect the environment, life, history, and culture of the native speakers, and are closely associated with their innermost spirit and feeling. So the translation of idioms is not easy. Before the idioms are translated, it is important to understand the profound culture connotation of them,that is,they are closely related to their culture origins.Its translation requires not only to convey the meaning,but also to win the acceptance of the target readers. There are many strategies employed in idioms translation, such as literal translation, literal translation plus annotations, communicative translation, free translation, combination of literal translation and free translation and so on. Idiom translation is the process of information conversion, this process reflects equivalent principle―equal content, equal form, equal style. But there are many differences between English and Chinese when idiom being translated. So it is hard to reach absolute equality.II. An Overview of Functional Equivalence2.1 The Origin of Functional EquivalenceThe concept of functional adequacy in translating has been described in a number of books and articles as “dynamic equivalence.” In Toward a Science of Translating (Nida 1964) dynamic equivalence has been treated in terms of the“closest natural equivalent,”but the term“dynamic”has been misunderstood by some people as referring only to something which has impact. Accordingly, many individuals have been led to think that if a translation has considerable impact then it must be a correct example of dynamic equivalence. Because of this misunderstanding and in order to emphasize the concept of function,it has seemed much more satisfactory to use the expression“functional equivalence” in describing the degrees of adequacy of a translation.Functional Equivalence Theory is advanced by Eugene A.Nida, the main founder of modern translation theorist. Concentrating on what a translation does or performs, the introduction of the idea of “functional equivalence”provides a sound basis for talking about translation as a form of intercultural communication. In comparison with many other theories, Nida’s Functional Equivalence Theory has been widely accepted in translation.2.2 The Development of Functional EquivalenceFunctional Equivalence was initiatively developed from “Dynamic Equivalence”, which has been widely and successfully adopted in Bible translation since the 1950s. In 1970, Nida was appointed Translators Research Coordinator in the United Bible Society(UBS).Most of new versions of Bible all follow principles of “dynamic equivalence” put forward by Nida. With the successful organization of several versions of the Bible translation, many scholars agree that “Dynamic Equivalence can be applied to guide general translation practice as well. Undoubtedly, the value of “Dynamic Equivalence” is not limited in Bible translation only. In Nida’s study of translation theory, the essential idea of “dynamic equivalence”,together with“formal equivalence”,is distinguished in his book Toward a science of Translation. But, he didn’t give a clear definition of “dynamic equivalence” until 1969.In From one Language to Another (1986), the expression “dynamic equivalence” is superseded by “functional equivalence”. But essentially there is not much difference between the two concepts. The substitution of“functional equivalence”is just to stress the concept of function and to avoid the confusion about the term “dynamic”, which is mistaken by some people as impact. What’s more, as Nida classifies the functions of the language into nine types, that is, expressive function, cognitive function, interpersonal function, informative function, imperative function, performative function, emotive function, aesthetic function and metalingual function, he hopes to emphasize the “communicative function” of translation by adopting “functional equivalence”.2.3 The Nucleus of Functional EquivalenceIn the Functional Equivalence Theory, Nida puts the “Receptor’s Response” as the nucleus of the Functional Equivalence. It is easy to find that Nida pays great attention to the receptor’s response, which has been ignored by earlier theorists. This is certainly a vital contribution in the translation history for it is helpful to settle the dispute between literal translation and free translation.According to Nida’s theory, the concept of translating shift from “the form of the message” to “the response of the receptor”. As a matter of fact, “the receptor’s response” serves as a vital measurement for the success in translating. An adequate translation should make sure that audience in the target language community respond in the similar way as those in the source language community. That is to say, the critic should judge a translation not by the verbal correspondence between the two texts, but by the way that source language and target language receptors’ responce.2.4 The Significant Role of Functional Equivalence in Cross-Cultural TranslationA word in one language is successfully translated into another word in another culture and language, then the response of target language readers may be the same as that of source language readers. The study of translation theory has gone through a long journey. Many scholars believe that a qualified translator should be not only bilingual, but also bi-cultural, and only in this way, can produce a good translation.Nida,a most authoritative translation theorist and practitioner,also attaches much importance to cultural effect on translation.Since language is a part of culture,translating from one language into another cannot be done satisfactorily without adequate knowledge of the two cultures involved. In the research of translation, Nida has become aware of the great importance of cultural factorial translating. He holds that the cultural factors in translating are more significant than the pure linguistic differences. In his view, the most serious mistakes in translating are usually made not because of verbal inadequacy, but of wrong cultural assumptions. It can be illustrated in the idiom translation. SL idioms are often found to be lively in the SL culture,but hardly understandable,if translated literally,because TL readers’cultural background, which differs by varying degrees from that of SL readers, often becomes a misleading factor.Therefore, “for truly successful translating, biculturalism is even more important than bilingually, since words only have meaning in terms of the cultures in which they function.” That is, “Only by being in the countries in which a foreign language is spoken can one acquire the necessary sensitivity to the many special words and phrases.” Cultural differences have brought many difficulties to translation, and only by cultural adjustments and modifications,can we successfully reach the goal of“functional equivalence”,or go near to its requirements.That is also the close connection between the two important aspects—functional equivalence and cultural factors in Nida’s views on translation.Ⅲ. An Introduction of English and Chinese Idioms3.1 The Definition and Classification of Idioms“An idiom is a set phrase of two or more words that means something different from the literal meaning of the individual words.” Generally speaking, idioms cover set phrases and short sentences, which are peculiar to the language in question and loaded with the native culture and ideas. In most cases, the meaning of idiomatic expressions cannot be deduced from the literal definitions and the arrangement of its parts, but refer to a figurative meaning that is known only through conventional use. Strictly speaking, idioms are expressions that are not readily understandable from their literal meanings of individual elements.In a broad sense,idioms may include colloquialisms,catchphrases,slang expressions, proverbs, etc.Idioms can be classified into five kinds according to their grammatical functions.1. Idioms nominal in nature: they have a noun as the key word and function as nouns in a sentence. For example, “White elephant” refers to something useless and unwanted but big and costly.2. Idioms adjectival in nature: they function as adjectives in a sentence but the constituents are not necessarily adjectives. For example, “Sick as a dog” means seriously ill; “Cut and dried” means already set and unlikely to be changed.3.Idioms verbal in nature:they function as verbs in a sentence. And they are the largest group, including: (a) the phrasal verbs that are idioms composed of a verb plus a preposition and /or a particle. For example, “To look into”: investigate. (b) Verb phrases-the phrases that serve as verb. For example,“To make it” means “To arrive in time or succeed”.4. Idioms adverbial in nature: they function as adverbials in a sentence. For example, “With flying colors”means to fulfill something successfully.5. Sentence idioms: such idioms are mainly in complete sentential form. They are usually proverbs or sayings including colloquialisms and catchphrases.The difficulty in using idiom lies first in the difficulty of grasping the elusive and figurative meaning, of determining the grammatical functions of idioms. So it’s necessary to learn about the different types of idioms and their grammatical functions.3.2 The Origin of IdiomsAccording to the research,cultural differences that can be reflected by the idioms usually include geographical conditions, historical events, religious belief, etc. Culture has a large field and it is an important system. As a component of culture, idiom reflects colorful cultural phenomenon of a nation. 3.2.1 Geographical ConditionsEvery nation has its specific geographical environment, which differs from one nation to the other. The factor of geographical conditions plays an important role in the production of the idioms, for many idioms are born to it.As far as we know, Britain is a sea sailing country, which as a matter of fact has a lot of idioms containing words concerning the sea. For example, “rest on one’s oars”(暂时歇一歇), “keep one’s head above water”(奋力图存), “sink or swim”(不知好歹), “go with the stream” (随波逐流), etc. Obviously, we can hardly find any equivalent figurative idioms in Chinese for those idioms.It is because of the distinctive geographical condition between these two nations. Different from Britain, China has long been a large agricultural country, and an overwhelming majority of the people lives in the rural area. In the translation of English figurative idioms, geographical conditions should be taken into consideration. For example, we translate “spend money like water” into “挥金如土”, “spring up like mushroom” into “雨后春笋”.“To drink like a fish”, frankly speaking, this idiom is illogical. The purpose for the fish to open its mouth inthe water is to take in air rather than to drink water. Apparently,this idiom is the result of the misunderstanding by English ancestors of the surrounding. So, when the idiom comes to be translated, it isn’t suitable for us to translate it into “像鱼一样喝水”. In Chinese, there are certain words to indicate someone that is good at drinking, that is “牛饮”. Owing to the geographical condition, Chinese people have a close contact with the cattle for this animal helps the Chinese to work in the field through history. Many Chinese words are associated with the cattle. While English people say “work like a horse” as they use horse to plow in the early time, Chinese say “像老黄牛一样干活”.3.2.2 Historical EventsBeing the precious treasure of the nation, historical events certainly take on the national and traditional characteristics, in the mean time, are a reflection of the profound cultural specialties. A large number of English idioms originate from the legends and myths, historical events or literary works, which have simple structures but rich meanings.There are a lot of English idioms coming from certain legends and myths. Idioms like “to cry wolf” (狼来了--发假警报), “sour grapes” (酸葡萄--得不到而佯称不好, “cat’s paw” (猫爪子--被人利用做冒险或厌恶事情的人), “to pull the chestnuts out of the fire” (火中取栗--替人冒险) all come from Aesop’ Fables. Idiom “rain cats and dogs” stems from the San Dinavia myths. It is said that the wizards taking charge of the rain and wind. Thus, it is not difficult to understand why the Chinese translation for “rain cats and dogs”is “倾盆大雨”.Some idioms, such as, “to meet one’s waterloo” (遭遇滑铁卢--毁灭性打击), “to eat the crow” (吃下乌鸦--忍辱负重), “Columbus’ egg” (哥伦布竖鸡蛋--万事开头难), “Dunkrik evacuation” (敦刻尔克大撤退--溃退) come from the true historical events. Thus, an awareness of the history is of significance in translating these idioms. Let’s take “Hobson’s choice” as an example. Hobson was a famous boss of a post for renting horses in 16th century of England. He rented his horse in fixed order, so people could not choose the horses they liked but accepted the one offered, even it was an inferior one, otherwise they could get on horses at all. Thus, this idiom is now used to express the meaning of the choice between taking what one is offered and getting nothing at all. After the understanding of the allusion of this English idiom,we may translate it as“别无选择”.“To cross the Rubicon”is another example. As “Rubicon” is the name of a river in middle Italy, most Chinese people cannot understand the idiom. Caesar and Pompey were leaders of two military groups, which were separated by the river “Rubicon”. As only by crossing the river, could Caesar fight with Pompey, so whether cross the river or not was a decision that had to be made by Caesar and now people use “to cross the Rubicon” to express the meaning of making up one’s mind. Thus, this idiom should be translated as “断然处置” according to its allusion.Many English idioms come from famous literary works. For example, “to mind one’s eyes” comes from Dicken’s Barnaby Rudge, meaning “to be careful”; “catch 22” from American author Joseph Heller’s novel entitled Catch 22, meaning “in a dilemma”, “one’s pound of flesh” comes from the famous drama The Merchant of Venice by Shakespeare, meaning “the exact amount of anything that is owned to a person, esp. when this will cause the person who has to pay it back a great deal of trouble or pain”. 3.2.3 Habits and CustomsSocial customs is a habit of living style in one nation, involving all fields of the life. It is the distinctive social customs between China and Britain that result in the differing points in some of the idioms.Food and drinks are one common social customs that go into everyday life. Known to all, British prefer bread, butter, jam and cheese, so there are many English idioms concerning these daily food, for example, “earn one’s bread” (养家糊口), “butter up” (讨好), “big cheese” (大人物), “hard cheese” (倒霉),“have jam on it” (好上加好), etc. Although Chinese are food of rice, much different with British customs, and Chinese idiom “小菜一碟” has the same indication with the English idiom “a piece of cakes”, both of which describe an easy task. Thus, English idiom “bread and cheese” should be translated into “粗茶淡饭” rather than “面包和奶酪” in Chinese, and the correct translation for “take the bread out if someone’s mouth” is “抢走别人饭碗”.Figurative idioms “above the salt” and “below the salt” come from the old customs at feasts when salt was expensive and a symbol of high social status. Traditionally, seats above the salt were reserved for those important and powerful guests or relatives whereas seat below the salt are for those ordinary ones.Idiom translation is simplified after the understanding of the social customs.The correct translation for “above the salt” is “尊为上宾”, and for “below the salt” is “当陪客,无足轻重”.3.2.4 Religious BeliefReligious belief, as an ideological idea, all along penetrates into every aspect of the human society and nation life. It contributes to the development of language, as well.Religion being an essential part of peoples’ spiritual life, its influence on language is far and profound. In the language of both Chinese and English, there are plenty of idioms concerning the religious beliefs.In terms of religious belief, the Chinese people adore the Buddha while the westerners show their great respect to the God. Greatly influenced by Buddhism, Chinese have many relative idioms, such as, “借花献佛”, “临时抱佛脚”, “僧多粥少”, etc. At the same time, Christianity also has reflection in the English, which is one of the western languages, such as,God bless you. 愿上帝保佑你God forbids. 苍天不容God helps those who help themselves. 自助者天助Man proposes, god disposes. 谋事在人,成事在天Many of the idioms can find origins in the Bible, the most classical work in the Christianity. As a missionary of religious thought, the Bible has been the absolute authority governing people’s value and thought. It is not the doctrine of Christianity, but also a book of great literary merit, rich in the source of culture and language. Idioms like “apple of one’s eyes” (掌上明珠), “feet of clay” (致命的弱点), “a Judas Kiss” (背叛行为), “apples of Sodom” (徒有虚表), “as poor as Job” (一贫如洗) all come from Bible.3.2.5 Mythological TalesFables, like religions, are also an outcome of the primitive society. The Primitive people invented the stories about mythical or supernatural beings and events, often employing as characters animals that speak and act like humans,to explain the natural phenomenon beyond their understanding.The ancients were fond of finding a hidden meaning in their mythological tales.Fables of a particular people are a mirror to reflect the trueborn ethical features. And they are more of the essence and embodiment of the way of thinking and moral values of an ethical group. They were mostly brought into being and spread in the spoken language. In modern English some ancient fables were later contracted into the idioms, some of whose sources include Greek and Roman mythology, Aesop’s fables.For example, “like an Apollo—美男子”, if you think a man is very handsome, you may say he is like an Apollo, to describe a young man of great physical beauty; “Pandora’s box—潘多拉的盒子”, this idiom stands for a source of unforeseen trouble, it is a box that Zeus gave to Pandora with instructions that she can’t open it, she gave in to her curiosity and opened it, all the miseries and evils flew out to afflict mankind.3.3 Cultural Flavor of IdiomsIdioms are the expressions in a language gradually developed in the populace’s physical life and widely accepted and used among a community of people. They are , in essence, the outcome of cultural growth and ethnical evolution. Idioms are, often colloquial metaphors—terms which require of users some foundational knowledge, information, or experience, to use only within a culture where parties must have common reference. As a specialized form of language, idiom will naturally reflect its culture even more profoundly and intensely than all other kinds of words. As idioms are typically localized in a culture, learning idioms well in a language will undoubtedly involve knowledge of its culture.IV. The Application of Functional Equivalence in the Translation of Idioms4.1 Corresponding IdiomsSome idioms in both Chinese and English have the same images and meanings, they can reflect the similarity of Chinese and Western countries. So we can translate these idioms equivalently, and realize functional equivalence of meaning. This is the most ideal state, and realizes the unity of contradiction. 4.1.1 Literal TranslationFirstly, let’s see some examples:to strike while the iron is hot: 趁热打铁go through fire and water: 赴汤蹈火to pour oil upon the flame: 火上浇油easy come, easy go: 来的容易,去的快All roads lead to Rome: 条条大路通罗马This kind of idioms are the best examples to convert cultures of different country, and it can easily been accepted by the target language readers. And they are the best state of idiom translation. We always try to find the best way to translate idiom, but we cannot really achieve the ideal state of idiom translation, because of the difference between different cultures. As it is said that, the best translation is not only to let readers know the meaning of source language, but also the culture that the language bears. So entire equivalence can both make readers know meaning of the idiom, and cultural knowledge that idiom converts.In brief, by adopting the method of literal translation, we can establish the equivalence of the four aspects:forms,meanings,styles,and images,thus achieving the highest degree of functional equivalence. To some degree, literal translation is a good and effective strategy to establish equivalent translation.4.1.2 BorrowingIdiom translation contains different metaphors, the literal method should be used to preserve the original flavors. But things are not always like this. Sometimes some English idioms happen to coincide with some Chinese Idioms in forms, contents, associations and meanings. In this case, we can adopt this method of borrowing. For example, the Chinese idiom “隔墙有耳” can be translated as the English idiom “walls have ears. Sometimes the metaphors in the Chinese idiom and the target English idiom are different but they share the same meaning, at this time borrowing can also be adopted. Sometimes, some Chinese idioms have no metaphors themselves, but the English ones that have similar meaning with them have. In this case, if the metaphors in the English idioms are simple and the national coloring is not so strong, we can also use the method of borrowing. For example, the Chinese idiom “少年老成”has no metaphor itself and it can be translated by borrowing “to have an old head on young shoulders”. Here, the intended meaning of the English idiom is “young but experienced” which coincides with the meaning of the Chinese idiom. The only difference is that the Chinese one doesn’t have the images“head” and “shoulder”. More examples of this type are listed below:惹是生非: to wake a sleep dog旁敲侧击: to beat about the bush摇摇欲坠: to hang by a thread不伦不类: to be neither fish nor flesh先下手为强: The early bird gets the wormWith the help of this technique, readers of the translated idioms can share the cultural information and psychological feelings equally or similarly to that of the readers of the original idiom.4.2 Semi-Corresponding IdiomsThere are some idioms that we can infer their meaning easily according to their literal meaning, and make people of source and target language, which have the same feeling towards these idioms.4.2.1 Literal Translation and AnnotationGood literal translation can help Chinese readers to acquire the cultural information of English idioms, but direct literal translation without any notes will make readers feel puzzled. As a result, cultural gaps will be produced. Literal translation with notes may supply further explanation to English idioms, such as backgrounds, figurative meanings, contexts and sources, which may strengthen the acceptability of English idioms and retain the original flavor of English idioms. For example:the Big Apple--if it is translated into 大苹果城, most readers still don’t know what it is. But if a note is added: 大苹果城(美国纽约市的绰号),readers will understand it thoroughly.What’s more,they may acquire some new knowledge about this English idiom. English Allusion is a part of idiom, which has many splendid stories and origins. Literal translation with notes to translate allusion can make Chinese readers, especially children, widen their knowledge, such as recognize the legends in reading the version. For example:“play Cupid” (扮演丘比特, Note:当媒人); “Aladdin’s cave” (阿拉丁的宝洞, Note:财富的源泉); “skeleton in the cupboard” (衣橱里的骷髅, Note:家丑); “widow’s cruse” (寡妇的坛子, Note:取之不尽的源泉).4.2.2 LoaningTo some idioms, on the one hand, the image of the source language is difficult for the readers of target language to understand. On the other hand, the image of the source language or culture doesn’t have a particular impact on the readers’ reaction.Then, translator may seek an idiom which may contain different image but could express the same meaning in target culture, and reach the same function. That is, the readers of translated article can have the same feeling with the readers of original article after reading. For example:teach your grandmother to suck eggs: 班门弄斧between you, me and the gatepost: 天知、地知、你知、我知a drop in the ocean: 沧海一粟have one foot in the grave: 风烛残年If “between you, me and gatepost” translated into“在你、我和门柱”, nobody can guess the meaning of this idiom. Most readers don’t know the cultural background of source language, since it is from foreign environment. So it is hard for Chinese readers to understand the real meaning of this idiom, and its function cannot be realized in our language. Loaning will be employed to translate this kind of idioms. This strategy mainly uses Chinese idioms to replace English idioms.4.3 Non-Corresponding IdiomsThere are still some English and Chinese idioms, they don’t share the same form and image. At this time, the meaning and cultural information of this kind idioms can not be conveyed from one language to another correctly,so some other methods,such as Free Translation and Combination of FreeTranslation & Literal Translation should be considered.4.3.1 Free TranslationFree translation does not adhere strictly to the form or word order of the original. When there exists dissimilarities or great differences between English and Chinese in the sequence of vocabulary, in grammatical structure and art device, the literal translation method cannot be employed, and no Chinese substitute is suitable, free translation has to be used. Free translation can be defined as a translation method which mainly conveys the meaning and the style of the original text without transferring strictly its sentence patterns or figures of speech. Just as some people said that free translation is one method that the target text is faithful to the original content, not to the form of the source text. Since free translation does delete or add content to the original at random, translators must consider the original text carefully, try to express the information of source language in the target language as good as possible. For example:on pins and needles: 如坐针毡catch one’s second wind: 恢复精力come straight to the point: 开门见山let the cat out of the bag: 泄露秘密By translating idioms in this way, the picturesqueness, flavor and sound-effect of the original would, unfortunately, be lost, though the sense of the idioms has successfully been communicated. The sense of the idioms is translated at the expense of the images.4.3.2 Combination of Free Translation & Literal TranslationAnother effective method to render Chinese idioms into English is a combination of both Literal translation and free translation.Both of two methods have their own merits and demerits.Literal translation can help in retaining the original flavor by keeping the original forms, styles and images, thus represent the new culture to the target readers. But in some cases the mere literal translation will lead to the possible misunderstanding. At this time it is necessary to take the advantage of free translation since free translation can erase the misunderstanding and make the translated version easily understood. But on the other hand, the vivid images and the exotic flavor in the original text are lost, let alone enriching the target language. So in such a case we can combine the merits of these two methods to convey the meaning and maintain the cultural peculiarity of the original as well.The idiom “吃着碗里的惦着锅里的” is used to depict a greedy person. In the rending “keep one eye on the bowl and the other on the pan”, “keep one eye on” is the free translation of “吃着” & “惦着” and the rest is literally translated. At the same time “greedy-guts" is used to reveal the connotation of this idiom. This rendering employs the combination of literal translation and free translation. Through this we can still keep the original images and cultural characteristics. It is also a flexible and efficient way to achieve functional equivalence.V. ConclusionThe responsibility of translators’ is to let readers understand what they translate, and let readers have the same feeling with that of the source language readers.Functional equivalence takes the equivalence of readers’ reaction as the most important issue.Using functional equivalence theory in idiom translation has many advantages: 1) It can make target language have the same function as source language does. 2) It can make target language readers have the same feeling with that of source language readers. 3) It also can convert cultural knowledge. Nowadays, functional equivalence theory is widely used in different aspects of translation, not only in。

Nida is an influential linguist and translator in the West.Owing to his own research,Nida comes to the conclusion that anything that Can be said in one language Can be said in another with reasonable accuracy by establishing equivalent points of reference in the receptor’S culture and matching his cognitive framework by restructuring the constitutive elements of the message(Qiu Maoru,2000:340).It is a case that each language has their own distinctive features which prevent absolute communication across different languages.However,a high degree of effective communication is possible among all peoples because of the similarity of mental processes,somatic responses,range of cultural experience,and capacity for adjustment to the behavior patterns of others(Nida,1 964:53·55).It is universally accepted that there are no two exact things in the world,SO all the translators should bear in mind the fact that they can never produce a version exactly equivalent to the original,thus,in translating,what a translator seeks for should be the closest possible equivalent rather than absolute or complete equivalent. As to equivalence in translation, Nida basically divides it into two types:formal equivalence and functional equivalence.Literally,formal equivalence is in the aspect of language form while functional pays much more attention to the language function.During the past years,translation circles have shifted much more concern from formal equivalence to functional equivalence.“A recent summary of opinion on translating by literary artists,publishers,educators,and professional translators indicates clearly that the present direction is toward increasing emphasis on dynamic equivalence”(Qiu Maoru 2000:38).

广西师范大学硕士学位论文奈达功能对等视角下的商业广告翻译姓名:汤玉洁申请学位级别:硕士专业:英语语言文学指导教师:袁斌业20080401奈达功能对等视角下的商业广告翻译研究生:汤玉洁年级:2005级学科专业:英语语言文学指导老师:袁斌业教授研究方向:翻译理论与实践中文摘要广告是一种具有很高商业价值和实用性的文体,一则广告必须具有说服力和记忆价值。

随着商品经济的发展和各国经贸交往的增加,广告翻译日益重要。

美国翻译理论家奈达的功能对等理论自问世以来,在国内外翻译界都产生了深远的影响。

奈达是美国著名的翻译理论家、语言学家,在世界翻译领域占有重要的地位,被人称为“现代翻译理论之父”。

他的理论核心内容就是“动态对等”(Dynamic equivalence),后来为了强调“功能”的概念并避免有些人对“动态”的误解后将其改称“功能对等”( Functional equivalence)。

这一理论曾给中国翻译界带来了新鲜空气,也给译论注入新的血液。

许多翻译理论家如金堤,谭载喜曾大力赞赏功能对等理论。

这一理论是奈达在《圣经》的翻译中总结和提炼出来的,《圣经》从根本上讲,是以说服别人相信基督教义并希望别人采取某种行为为目的的一部作品,同样地,广告作为一种实用文体,其最大的特点也是其说服功能——说服消费者采取行动实施购买行为。

因此从这个意义上说,功能对等理论对于广告英汉互译都有极其重要的指导意义。

本文主要从广告文体的功能入手,分别讨论在功能对等理论指导下怎样实现广告翻译中出现的文化和美学效果对等。

同时考察功能对等理论在广告翻译中的实际操作效果。

通过分析,作者注意到国内广告翻译的实践中,英语广告汉译有许多优秀的成功典范,而汉语广告英译的错误百出,因此本文侧重于汉语广告英译研究,并通过引入奈达功能对等理论给出了具体的汉语广告英译的方法。

论文结构如下:导言部分包括引言,阐述了选题的缘由、研究目的、论文的结构和所运用的研究材料和方法。

探析《最蓝的眼睛》中女主人公的悲剧根源从《华伦夫人的职业》分析萧伯纳女性主义的进步性和局限性On C-E Translation of Neologisms from the Perspective of Nida’s Functional Equivalence Theory 英汉习语中价值观的差异《呼啸山庄》爱情悲剧根源分析《厄舍屋之倒塌》中的哥特元素分析The Influence of the Current American Marital Status on the Christian Views of Marriage英语反语的语用分析英语多义词习得的实证研究从《弗洛斯河上的磨坊》看维多利亚时期的新女性主义观《丧钟为谁而鸣》中罗伯特.乔丹性格的多视角分析文化视野下的中美家庭教育方法的比较简析文化意识在高中英语学习中的重要性从目的论角度看企业推介材料的中译英技巧-以家具产品介绍为例宋词英译中的归化和异化论亨利•詹姆斯《贵妇画像》中伊莎贝尔的婚姻悲剧Bertha Is Jane:A Psychological Analysis of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre任务型教学在高中英语阅读课堂中的实施浅析网络字幕组运作下的美剧翻译特点英汉“走类”动词短语概念隐喻的对比研究从《都柏林人》看乔伊斯的美学思想《身着狮皮》中的话语、移民与身份《麦田里的守望者》中反叛精神分析中式菜肴名称英译的功能观《榆树下的欲望》之农场意象--基于生态女性主义的分析《追风筝的人》中阿米尔的性格分析论商务英语信函写作的语篇衔接与连贯从动态对等角度分析中国旅游景点名称英译——以中国庐山网为例从语用学视角初步分析英语骂詈语试比较中美中学历史教育中历史思维的培养浅析MSN交谈中的话语标记语[税务管理]我国开征遗产税国际借鉴和政策选择研究女性意识的苏醒--对《愤怒的葡萄》中的约德妈妈形象的分析中西方跨文化商务活动中礼貌的语义差别浅析《藻海无边》中安托瓦内特的悲剧言语行为理论下的英语广告双关从社会习俗角度分析中西方文化差异从传统节日庆祝方式的角度比较中英文化差异乔伊斯的生活经历对其作品的影响--他是怎样刻画人物的论礼貌策略在商务信函写作中的运用观春潮:浅析“戏仿”背后海明威性格阴暗面论《德伯维尔家的苔丝》中的环境描写----从视觉和听学的角度Pragmatic Study on the Humor Effect in The Big Bang Theory从翻译美学角度评析白朗宁夫人“How do I Love Thee?”四种汉译本的得失论《苏菲的选择》中的悲剧性冲突《外婆的日常家当》中女性形象象征意义从《达罗卫夫人》看弗吉妮娅伍尔夫的个性中学英语教育中的情感教育浅析朱利安•巴恩斯《终结的感觉》中人物的异化丹尼尔•笛福《鲁滨逊漂流记》中的殖民研究从中国戏曲《梁祝》和美国音乐剧《妈妈咪呀》的比较看中美文化差异论《天路历程》的批判精神关于高中生英语听力理解中非语言因素的研究商务英语的词汇特征及翻译策略从认知语境的角度解读《一个干净明亮的地方》的隐含意义从功能理论角度分析电影《点球成金》字幕翻译Social Causes for Tess’s TragedyA Comparative Study of Courtesy Language between English and Chinese论《等待戈多》中的荒诞与象征商务英语信函文体分析爱与正义:《杀死一只知更鸟》主人公阿提克斯•芬奇形象解读英语歧义现象及其在广告中的应用中式思维模式对初中生英语写作的影响从作者夏洛蒂·勃朗特看《简·爱》《药》的两个英译本中翻译技巧比较《还乡》中游苔莎的悲剧命运分析《雨中的猫》中女性主体意识的觉醒目的论下的修辞手法翻译:以《爱丽丝漫游奇境记》两个汉语译本为例英汉称呼语的对比研究An Ecofeministic Approach to Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants”(开题报告+论文+文献综述)《傲慢与偏见》中简·奥斯汀的婚姻观及其现实意义论“看,易,写”方法在旅游翻译中的应用技术性贸易壁垒对中国外贸行业的影响—以CR法案为例论《小伙子古德曼布朗》中象征主义的使用《哈利波特》的原型——亚瑟王传奇试论《围城》中四字成语的英译骑士精神与时代精神:论《苹果树》中浪漫主义与现实主义的对峙与对话A Comparative Study of Oedipus Complex in Sons and Lovers and Thunderstorm从《献给艾米丽的玫瑰》看福克纳小说中贵族的没落旅游英语翻译的研究叶芝诗歌中的象征主义手法论应变能力在同声传译中的应用中英数字词语文化内涵对比研究浅析礼貌原则在跨文化交际中的体现A Comparison of the English Color Terms英语语义歧义分析及其语用价值浅析拉尔夫·埃里森《看不见的人》的象征艺术《麦田里的守望者》中霍尔顿的性格分析英语“名词+ ly”类形容词的词化分析、语义特征及句法功能王尔德童话《快乐王子》中的对比艺术试比较中美中学历史教育中历史思维的培养对比分析《喜福会》中母女美国梦和母女冲突的原因及表现中英爱情谚语的隐喻研究及其翻译近年来汉语中英语借词的简析网络流行语翻译评析——“神马都是浮云”个案分析汉语无主句英译方法探析对《雾季的末日》主题的解读中美价值观的比较--以《老友记》为例英语混成新词建构新解:多元理论视域接受美学指导下的电影字幕翻译——以《冰河世纪II》为例从意象理解艾米莉狄金森其人其诗从《夜莺与玫瑰》看王尔德唯美主义的道德观中英动物习语的跨文化分析论汉语成语中数字英译的语用等效性《红楼梦》杨译本与霍译本文化意象的翻译对比杰克的悲剧与海明威的世界观析《道林格雷》中王尔德用来揭示生活与艺术冲突的方法浅析我国中小企业电子商务现状与对策广告英语的语言特征A Glimpse of Intercultural Marriage between China and Western Countries 论《了不起的盖茨比》中的象征及其作用《绯闻少女》中的话语标记词研究《名利场》中女性命运对比汉译英语足球新闻中修辞手法的策略An Analysis of the Cultural Identity in Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Cl ub网络英语对汉语词汇的影响研究The Developments of Marriage View over Three Periods in the West英语写作中干扰因素的分析浅析《宠儿》中塞丝背上的树的形象浅论《儿子与情人》中劳伦斯的心里分析技巧浅析虚词在英语写作中的重要性《了不起的盖茨比》—美国梦的破灭中西方文化差异对国际商务谈判的影响及对策分析广告语篇中的预设分析浅析非言语交际在小学英语教学中的运用浅议中西跨文化交际中的禁忌语从电影功夫字幕翻译谈文化负载词的翻译现代叙事艺术与海明威的《永别了武器》浅析儿童自然英语教学法的心理学优势英语名的取名艺术嘉莉妹妹失去自我的悲剧性命运对中国女性自我价值体现的启迪试从大卫•科波菲尔分析狄更斯的人道主义精神浅论《黑天鹅》电影的象征手法运用通过电视广告看中美思维模式差异《动物农场》中隐喻的应用及其政治讽刺作用中西方生死观之比较英汉新词对比研究从文本类型角度看企业外宣材料的翻译旅游英语中的跨文化交际语用失误分析分析双城记中的讽刺用法论《瓦尔登湖》的超验主义思想初中英语词汇教学法研究综述宗教枷锁下的人性挣扎——《红字》中丁梅斯代尔形象解读浅谈企业形象广告设计浅析《麦田里的守望者》中的部分重要象征物On Allan Poe’s Application of Gothic Elements and His Breakthroughs — Through The Fall of the House Of Usher外国商标的中文翻译策略及其产品营销效应研究从《红字》看霍桑对清教主义的批判与妥协中英谚语的文化差异与翻译从伊登和盖茨比之死探析美国梦破灭的必然性从合作原则看《白象似的群山》中的对话中国跨文化交际学研究存在的不足与建议早期吸血鬼与现代影视作品中吸血鬼形象的对比On the Translation of Advertisement Slogans from the Perspective of Functional Equivalence《红字》中海斯特性格分析浅析英语颜色词的语义特征顺应理论视角下《红楼梦》中社交指示语的英译研究英汉语中恐惧隐喻的认知分析《看不见的人》中的“暗与明”意象探究极致现实主义与现代自然主义──分析杰克伦敦小说《野性的呼唤》从《了不起的盖茨比》看美国梦幻灭的必然性《鲁滨逊漂流记》中鲁滨逊的资产阶级特征探析《红字》中齐灵渥斯的恶中之善从跨文化交际角度看中西方商务谈判An Analysis of Female Characters in Uncle Tom’s Cabin从文化角度谈商标的中英互译A Survey on Self-regulated Learning of English Major从玛氏公司看英美文化对广告的影响爱伦•坡的《乌鸦》中的浪漫主义分析国际贸易中商务英语的翻译策略论《简爱》中话语的人际意义对《红字》中罗杰齐灵沃斯的新认识英文电影名称汉译原则和方法的研究女性主义翻译理论在文学作品中的体现——以《傲慢与偏见》两个中译本为例中英诗歌及时行乐主题比较论《黑夜中的旅人》中主人公的信仰冲突与融合从原型批评理论来看<<哈利波特>>系列小说中的人物原型学生英译汉翻译中的英式汉语及其改进方式托尼莫里森《宠儿》的哥特式重读隐转喻名名复合词的语义分析中西方文化差异在初中英语词汇教学中的体现浅析“冰山理论”调动读者参与的作用企业网络营销策略分析福克纳《我弥留之际》中达尔形象解析中西礼貌用语的语用对比研究论《格列佛游记》中的讽刺《鲁滨逊漂流记》的后殖民主义解读中美饮食文化实体行为与非实体行为的民族差异When Chinese Tradition Meets Western Culture: Comparison between Qi Xi and V alentine’s Day Demystification of Model Minority Theory《德伯家的苔丝》中苔丝人物性格分析The Analysis of Narrative Techniques in William Faul kner’s “A Rose for Emily”中美高校校园文化对比论《纯真年代》的女性意识从奈达的动态对等理论比较研究《德伯家的苔丝》的两个中文译本基于SWOT的星巴克发展战略研究On the Symbolic Meaning of the Marlin in The Old Man and the Sea伯莎梅森形象分析。

最新英语专业全英原创毕业论文,都是近期写作1 浅析唐诗翻译的难点和策略2 On Women’s Status in the Early th Century Seen in The Sound and the Fury3 顺句驱动原则下英汉同声传译中英语非动词转换为汉语动词的研究4 《那个读伏尔泰的人》英译汉中定语从句的翻译策略5 唯美主义理论与实践的矛盾——解析王尔德的矛盾性6 从毛姆《刀锋》看两次世界大战期间的知识分子形象7 文档所公布各专业原创毕业论文。