Brain Anatomy in Turner Syndrome Evidence for Impaired Social and Spatial–Numerical Networ

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1.03 MB

- 文档页数:11

大脑的奥秘:神经科学导论答案大脑的奥秘:神经科学导论答案1.1脑与外部世界1【判断题】某些癫痫病人由于外科手术而成为裂脑人,因此他们的大脑可以相互独立工作。

(?)2【判断题】人类的一些高级认知过程都和心脏有关,是心与脑的共同表现形式。

(?)3【判断题】所有具备生命特征的动物都有大脑。

(?)1.2脑科学的应用1【单选题】现代科学技术可以用(C)来控制神经细胞的反应,控制特定的大脑核团。

A、磁波B、信号C、光D、声音2【判断题】别人没有任何方法破解深藏于内心的秘密。

(?) 3【判断题】不同的人脑功能上的显著差别来源于其不同的文化的宗教背景。

(?)4【判断题】大脑的每个半球都包括大脑皮层。

(?)5【判断题】大脑皮层是高级神经活动的物质基础。

(?)1.3打开大脑的“黑盒子”1【单选题】(A)是人脑的最大部分。

A、端脑B、间脑C、中脑D、后脑2【单选题】(C)检测的是血液中含氧量的变化。

A、单电级记录B、功能核磁共振C、内源信号光学成像D、深度脑刺激3【判断题】深度脑刺激可以无损伤地看到大脑的功能活动。

(?) 4【判断题】神经元的细胞体大小为1毫米。

(?)2.1“标准像”与信息传递1【单选题】以下(C)是神经元所不具备的。

A、细胞核B、树突C、细胞壁D、轴突2【单选题】神经元的末端的细小分支叫做(D)。

A、树突B、细胞核C、轴突D、神经末梢3【判断题】每个神经元可以有多个树突。

(?)4【判断题】每个神经元可以有多个轴突。

(?)2.2信息交流的结构单元1【单选题】按照对后继神经元的影响来分类,可分为(A)类。

A、2B、3C、4D、12【单选题】电突触具备(D)特点。

A、突触延迟B、神经递质释放C、前膜与后膜相互独立隔绝D、信号可双向传递3【多选题】神经元按其功能可分为(ABC)。

A、感觉神经元B、联络神经元C、运动神经元D、抑制性神经元4【判断题】神经元具有接受、整合和传递信息的功能。

(?)5【判断题】神经元就是神经细胞。

人工智能与信息社会网课答案如果没找到答案,请关注公众号:搜搜题免费搜题1. 单选题电影()中,机器人最终脱离了人类社会,上演了“出埃及记”一幕。

(1.0分)我,机器人2. 单选题 1977年在斯坦福大学研发的专家系统()是用于地质领域探测矿藏的一个专家系统。

(1.0分)没搜到哦~3. 单选题能够提取出图片边缘特征的网络是()。

(1.0分)卷积层4. 单选题在ε-greedy策略当中,ε的值越大,表示采用随机的一个动作的概率越(),采用当前Q函数值最大的动作的概率越()。

(1.0分)大;小5. 单选题考虑到对称性,井字棋最终局面有()种不相同的可能。

(1.0分)没搜到哦~6. 单选题在语音识别中,按照从微观到宏观的顺序排列正确的是()。

(1.0分)帧-状态-音素-单词7. 单选题没搜到哦~8. 单选题在强化学习过程中,()表示随机地采取某个动作,以便于尝试各种结果;()表示采取当前认为最优的动作,以便于进一步优化评估当前认为最优的动作的值。

(1.0分)9. 单选题一个运用二分查找算法的程序的时间复杂度是()。

(1.0分)没搜到哦~10. 单选题典型的“鸡尾酒会”问题中,提取出不同人说话的声音是属于()。

(1.0分)非监督学习11. 单选题 2016年3月,人工智能程序()在韩国首尔以4:1的比分战胜的人类围棋冠军李世石。

(1.0分)AlphaGo12. 单选题首个在新闻报道的翻译质量和准确率上可以比肩人工翻译的翻译系统是()。

(1.0分)微软13. 单选题被誉为计算机科学与人工智能之父的是()。

(1.0分)图灵14. 单选题没搜到哦~15. 单选题科大讯飞目前的主要业务领域是()。

(1.0分)语音识别16. 单选题如果某个隐藏层中存在以下四层,那么其中最接近输出层的是()。

(1.0分)归一化指数层17. 单选题每一次比较都使搜索范围减少一半的方法是()。

(1.0分)18. 单选题人类对于知识的归纳总是通过()来进行的。

Unit 5 Into the unknown 学案1.There is a profound charm in mystery. —Chatfield神秘事物具有深奥的魅力。

2.Nature is not governed except by obeying her. —Bacon自然不可驾驭,除非顺从她。

3.To be beautiful and to be calm is the ideal of nature. —Richard Jefferies美与宁静是自然的理想。

4.Mix a little mystery with everything,and the very mystery arouses veneration.任何事都掺一点神秘性,唯其神秘才引起崇拜。

5.He had lived long enough to know it is unwise to wish everything explained.长时期的生活经历足以使他懂得要想把一切都解释清楚是不明智的。

6.Man masters nature not by force but by understanding. —Bronwski人征服大自然不是凭力量,而是凭对它的认识。

The “Monster of Lake Tianchi” in the Changbai Mountains in Jilin Province,northeast China,is back in the news after several recent sightings.The director of a local tourist office,Meng Fanying,said the monster,which seemed to be black in color,was ten meters from the edge of the lake during the most recent sighting.“It jumped out of the water like a seal—about 200 people on Changbai's western peak saw it,”he said.“Although no one really got a clear look at the mysterious creature,Xue Junlin,a local photographer,claimed that its head looked like a horse.”In another recent sighting,a group of soldiers claim they saw an animal moving on the surface of the water.“It was greenishblack and had a round head with 10centimeter horns”,one of the soldiers said.Mike Taylor,a university student in the study of prehistoric life forms for his Ph.D.,discovered a brandnew species of dinosaur,while conducting research at the Natural History Museum in the United Kingdom.This new species was identified as part of the sauropod family of dinosaurs.The sauropods were four-legged,vegetarian dinosaurs,with very long necks and tails,and relatively small skulls and brains.One of their most unusual characteristics was their nostrils,which were higher up in their head,almost near the eyes.So far,the sauropod bones have been found in every continent except Antarctica,and they are one of the longest living group of dinosaurs,spanning over 100 million years.This new species,named Xenoposeidon proneneukos,which means forward sloping,lived about 140 million years ago.Mike Taylor,who has spent five years studying sauropod vertebrae,immediately knew that this was the backbone of a sauropod.However,he had never seen one like this before.Further research proved this was indeed a new kind of sauropod.The bone,which had been discovered in the 1890s,had never been examined.[探究发现]1.Find out the main idea of the passage.Mike Taylor discovered a brand-new species of dinosaur.2.Find out the new dinosaur's most obvious characteristic.Nostril.3.Find out the time that the bone was discovered.In the 1890s.Ⅰ.匹配词义A.单词匹配()1.intrigue A.n.气旋;旋风()2.pyramid B.n.金字塔()3.astronomy C.n.衰败()4.tropical D.adj.来自热带的;产于热带的()5.cyclone E.v.(因奇特或神秘而)激起……的兴()6.downfall F.n.天文学()7.megadrought G.n.超级干旱[答案]1-5EBFDA6-7CGB.短语匹配()1.fall into ruin A.相当于()2.make a discovery B.收回()3.correspond to C.做出发现;发现()4.take back D.将……应用于……()5.apply...to... E.(因无人照料而)衰落,败落[答案]1-5ECABDⅡ.默写单词1.civilisation n.文明(社会)2.bury v. 将……埋在下面3.canal n. 运河4.ruin n. 残垣断壁,废墟5.abandon v. 离弃,逃离6.dismiss v. 拒绝考虑,否定7.expansion n. 扩大;增加Ⅰ.语境填词astronomy;dismiss;expansion;abandon;civilisation;was buried;canal;ruin The Victorians regarded the railways as bringing progress and civilisation.2.The truth has been buried in her memory since then.3.Astronomy is the scientific study of the sun,moon,stars,planets,etc. 4.A canal is a passage dug in the ground for boats and ships to travel along. 5.The old mill is now little more than a ruin.6.The cold weather forced us to abandon going out.7.I think we can safely dismiss their objections.8.Despite the difficulties the company is confident of further expansion.Ⅱ.语法填空之派生词1.Hunger and drought led to the collapse of Mayan civilisation(civilise)a millennium ago.2.The child was found abandoned(abandon)but unharmed.3.The buildings were in a ruinous (ruin)condition.4.Expansionism(expansion)was advocated by many British politicians in the late 19th century.5.There are no previous statistics for comparison(compare).6.They questioned the accuracy(accurate)of the information in the file.7.The test can accurately (accurate)predict what a bigger explosion would do.8.Her dismissal(dismiss)of the threats seemed irresponsible.1.Although his theory has been dismissed by scholars,it shows how powerful the secrets of Ancient Maya civilisation are among people.虽然他的理论已经被学者们所否定,但它显示了古代玛雅文明的奥秘在人们心中是多么的有影响力。

1【判断题】思考是有目的的心理活动而且对于这种心理活动,当事人可以进行一些控制。

( )我的答案:√2【判断题】思考的关键是控制。

( )我的答案:√1【判断题】我们遇到形形色色的问题可以分为两类问题,有的问题不需要思考,有的问题需要思考。

()我的答案:√2【判断题】思考就是针对特定问题想出好的解决办法。

()我的答案:√1【单选题】传统教学中,学生主要以哪种方式思考?()窗体顶端A、B、我的答案:B2【单选题】富有挑战性和互动性的是何种思考方式?()窗体顶端A、B、我的答案:A3【单选题】以下哪种思考方式需要有较强的学习主动性?()窗体顶端A、我的答案:B4【单选题】海绵式思考是被动接受作者观点与推理但不能评价,淘金式思考是主动发现最有意义的论点和观念并评价。

()窗体顶端A、B、我的答案:B1【单选题】赫曼的全脑模型中,逻辑型属于()象限?窗体顶端A、B、我的答案:A【单选题】在思考过程中,以图像和心像进行思考的是?()窗体顶端A、B、我的答案:B3【单选题】在思考过程中,比较偏向直觉思考的是?()窗体顶端A、B、我的答案:A1【判断题】创造力并非人人都有。

()我的答案:× 2【判断题】创造力可以通俗地解释为发现和解决新问题、提出新设想、创造新事物的能力。

()我的答案:√ 3【判断题】人们的创造力可以通过科学的教育和训练而不断被激发出来,转化为显性的创造能力,并不断得到提高。

()我的答案:√ 1【单选题】在思考过程中,创造力的源泉是?()窗体顶端A、B、我的答案:B2【单选题】在思考过程中,偏向理性思考的是?()窗体顶端A、我的答案:A3【判断题】一些所谓的“无创造力”的人,通过科学开发其创造力也可以成为显性的。

()我的答案:√ 1【单选题】神经心理学的研究一般认为思考的心理过程分为两个阶段,哪一阶段与创意思考有着密切的关联?()窗体顶端A、B、我的答案:A2【单选题】演绎是什么样的推理方法?()窗体顶端A、我的答案:B3【单选题】生物学家按界、门、纲、目、科、属、种的顺序,把世界上所有的生物分了类,并揭示了各类生物间的关系和联系,这属于什么过程?()窗体顶端A、B、C、D、我的答案:B4【判断题】在思考方法中,概括是使事物普遍化的思考过程。

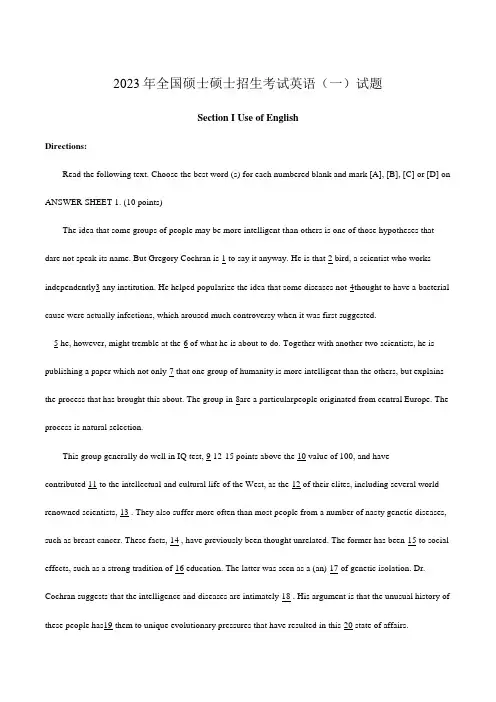

1.[A] selected [B] prepared [C] obliged [D] pleased2.[A] unique [B] particular [C] special [D] rare3.[A] of [B] with [C] in [D] against4.[A] subsequently [B] presently [C] previously [D] lately5.[A] Only [B] So [C] Even [D] Hence6.[A] thought [B] sight [C] cost [D] risk7.[A] advises [B] suggests [C] protests [D] objects8.[A] progress [B] fact [C] need [D] question9.[A] attaining [B] scoring [C] reaching [D] calculating10.[A] normal [B] common [C] mean [D] total11.[A] unconsciously[B] disproportionately[C] indefinitely[D] unaccountably12.[A] missions [B] fortunes [C] interests [D] careers13.[A] affirm [B] witness [C] observe [D] approve14.[A] moreover [B] therefore [C] however [D] meanwhile15.[A] given up [B] got over [C] carried on [D] put down16.[A] assessing [B] supervising [C] administering [D] valuing17.[A] development [B] origin [C] consequence [D] instrument18.[A] linked [B] integrated [C] woven [D] combined19.[A] limited [B] subjected [C] converted [D] directed20.[A] paradoxical [B] incompatible [C] inevitable [D] continuousSection II Reading ComprehensionPart ADirections:Read the following four texts. Answer the questions below each text by choosing [A], [B], [C] or [D]. Mark your answers on ANSWER SHEET 1. (40 points)Text 1While still catching up to men in some spheres of modern life, women appear to be way ahead in at least one undesirable category. “Women are particularly susceptible to developing depression and anxiety disorders in response to stress compared to men,” according to Dr. Yehuda, chief psychiatrist at New York’s Veteran’s Administration Hospital.Studies of both animals and humans have shown that sex hormones somehow affect the stress response, causing females under stress to produce more of the trigger chemicals than do males under the same conditions. In several of the studies, when stressed-out female rats had their ovaries (the female reproductive organs) removed, their chemical responsesbecame equal to those of the males.Adding to a woman’s increased dose of stress chemicals, are her increased “opportunities” for stress. “It’s not necessarily that women don’t cope as well. It’s just that they have so much more to cope with,” says Dr. Yehuda. “Their capacity for tolerating stress may even be greater than men’s,” she observes, “it’s just that they’re dealing with so many more things that they become worn out from it more visibly and sooner.”Dr. Yehuda notes another difference between the sexes. “I think that the kinds of things that women are exposed to tend to be in more of a chronic or repeated nature. Men go to war and are exposed to combat stress.Men are exposed to more acts of random physical violence. The kinds of interpersonal violence that women are exposed to tend to be in domestic situations, by, unfortunately, parents or other family members, and they tend not to be one-shot deals. The wear-and-tear that comes from these longer relationships can be quite devastating.”Adeline Alvarez married at 18 and gave birth to a son, but was determined to finish college. “I struggled a lot to get the college degree. I was living in so much frustration that that was my escape, to go to school, and get ahead and do better.” Later, her marriage ended and she became a single mother. “It’s the hardest thing to take care of a teenager, have a job, pay the rent, pay the car payment, and pay the debt.I lived from paycheck to paycheck.”Not everyone experiences the kinds of severe chronic stresses Alvarez describes. But most women today are coping with a lot of obligations, with few breaks, and feeling the strain. Alvarez’s experienc e demonstrates the importance of finding ways to diffuse stress before it threatens your health and your ability to function.21. Which of the following is true according to the first two paragraphs?[A] Women are biologically more vulnerable to stress.[B] Women are still suffering much stress caused by men.[C] Women are more experienced than men in coping with stress.[D] Men and women show different inclinations when faced with stress.22. Dr. Yehuda’s research suggests that women .[A] need extra doses of chemicals to handle stress[B] have limited capacity for tolerating stress[C] are more capable of avoiding stress[D] are exposed to more stress23. According to Paragraph 4, the stress women confront tends to be .[A] domestic and temporary[B] irregular and violent[C] durable and frequent[D] trivial and random24. The sentence “I lived from paycheck to paycheck.” (Line 5, Para. 5) shows that .[A] Alvarez cared about nothing but making money[B] Alvarez’s salary barely covered her household expense s[C] Alvarez got paychecks from different jobs[D] Alvarez paid practically everything by check25. Which of the following would be the best title for the text?[A] Strain of Stress: No Way Out?[B] Response to Stress: Gender Difference[C] Stress Analysis: What Chemicals Say?[D] Gender Inequality: Women Under StressText 2It used to be so straightforward. A team of researchers working together in the laboratory would submit the results of their research to a journal. A journal editor would then remove t he author’s names and affiliations from the paper and send it to their peers for review. Depending on the comments received, the editor would accept thepaper for publication or decline it. Copyright rested with the journal publisher, and researchers seeking knowledge of the results would have to subscribe to the journal.No longer. The Internet—and pressure from funding agencies, who are questioning why commercial publishers are making money fromgovernment–funded research by restricting access to it—is making access to scientific results a reality. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has just issued a report describing the far-reaching consequences of this. The report, by John Houghton of Victoria University in Australia and Graham Vickery of the OECD, makes heavy reading for publishers who have, so far, made handsome profits. But it goes further than that. It signals a change in what has, until now, been a key element of scientific endeavor.The value of knowledge and the return on the public investment in research depends, in part, upon wide distribution and ready access. It is big business. In America, the core scientific publishing market is estimated at between $7 billion and $11 billion. The International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers says that there are more than 2,000 publishers worldwide specializing in these subjects. They publish more than 1.2 million articles each year in some 16,000 journals.This is now changing. According to the OECD report, some 75% of scholarly journals are now online. Entirely new business models are emerging; three main ones were identified by the report’s authors. There is the so-called big deal, where institutional subscribers pay for access to a collection of online journal titles through site-licensing agreements. There is open-access publishing, typically supported by asking the author (orhis employer) to pay for the paper to be published. Finally, there are open-access archives, where organizations such as universities or international laboratories support institutional repositories. Other models exist that are hybridsof these three, such as delayed open-access, where journals allow only subscribers to read a paper for the first six months, before making it freely available to everyone who wishes to see it. All this could change the traditional form of the peer-review process, at least for the publication of papers.26. In the first paragraph, the author discusses .[A] the background information of journal editing[B] the publication routine of laboratory reports[C] the relations of authors with journal publishers[D] the traditional process of journal publication27. Which of the following is true of the OECD report?[A] It criticizes government-funded research.[B] It introduces an effective means of publication.[C] It upsets profit-making journal publishers.[D] It benefits scientific research considerably.28. According to the text, online publication is significant in that .[A] it provides an easier access to scientific results[B] it brings huge profits to scientific researchers[C] it emphasizes the crucial role of scientific knowledge[D] it facilitates public investment in scientific research29. With the open-access publishing model, the author of a paper is required to .[A] cover the cost of its publication[B] subscribe to the journal publishing it[C] allow other online journals to use it freely[D] complete the peer-review before submission30. Which of the following best summarizes the text?[A] The Internet is posing a threat to publishers.[B] A new mode of publication is emerging.[C] Authors welcome the new channel for publication.[D] Publication is rendered easily by online service.Text 3In the early 1960s Wilt Chamberlain was one of the only three players in the National Basketball Association (NBA) listed at over seven feet. If he had played last season, however, he would have been one of 42. The bodies playing major professional sports have changed dramatically over the years, and managers have been more than willing to adjust team uniforms to fit the growing numbers of bigger, longer frames.The trend in sports, though, may be obscuring an unrecognized reality: Americans have generally stopped growing. Though typically about two inches ta ller now than 140 years ago, today’s people—especially those born to families who have lived in the U.S. for many generations—apparently reached their limit in the early 1960s.And they aren’t likely to get any taller. “In the general population today, at t his genetic, environmental level, we’ve pretty much gone as far as we can go,” says anthropologist WilliamCameron Chumlea of Wright State University. In the case of NBA players, their increase in height appears to result from the increasingly common practice of recruiting players from all over the world.Growth, which rarely continues beyond the age of 20, demands calories and nutrients—notably, protein—to feed expanding tissues. At the start of the 20th century, under-nutrition and childhood infections got in the way. But as diet and health improved, children and adolescents have, on average, increased in height by about an inch and a half every 20 years, a pattern known as the secular trend in height. Yet according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, average height—5'9" for men, 5'4" for women—hasn’t really changed since 1960.Genetically speaking, there are advantages to avoiding substantial height. During childbirth, larger babies have more difficulty passing through the birth canal. Moreover, even though humans have been upright for millions of years, our feet and back continue to struggle with bipedal posture and cannot easily withstand repeated strain imposed by oversize limbs. “There are some real constraints that are set by the genetic architecture of the individual organism,” says anthropologist William Leonard of Northwestern University.Genetic maximums can change, but don’t expect this to happen soon. Claire C. Gordon, senior anthropologist at the Army Research Center in Natick, Mass., ensures that 90 percent of the uniforms and workstations fit recruits without alteration. She says that, unlike those for basketball, the length of military uniforms has not changed for some time. And if you need to predict human height in the near future to design a piece of equipment, Gordon says that by and large, “you could use today's data and feel fairly confident.”31. Wilt Chamberlain is cited as an example to .[A] illustrate the change of height of NBA players[B] show the popularity of NBA players in the U.S.[C] compare different generations of NBA players[D] assess the achievements of famous NBA players32. Which of the following plays a key role in body growth according to the text?[A] Genetic modification.[B] Natural environment.[C] Living standards.[D] Daily exercise.33. On which of the following statements would the author most probably agree?[A] Non-Americans add to the average height of the nation.[B] Human height is conditioned by the upright posture.[C] Americans are the tallest on average in the world.[D] Larger babies tend to become taller in adulthood.34. We learn from the last paragraph that in the near future .[A] the garment industry will reconsider the uniform size[B] the design of military uniforms will remain unchanged[C] genetic testing will be employed in selecting sportsmen[D] the existing data of human height will still be applicable35. The text intends to tell us that .[A] the change of human height follows a cyclic pattern[B] human height is becoming even more predictable[C] Americans have reached their genetic growth limit[D] the genetic pattern of Americans has alteredText 4In 1784, five years before he became president of the United States, George Washington, 52, was nearly toothless. So he hired a dentist to transplant nine teeth into his jaw—having extracted them from the mouths of his slaves.That’s a far different image from the cherry-tree-chopping George most people remember from their history books. But recently,many historians have begun to focus on the role slavery played in the lives of the founding generation. They have been spurred in part by DNA evidence made available in 1998, which almost certainly proved Thomas Jefferson had fathered at least one child with his slave Sally Hemings. And only over the past 30 years have scholars examined history from the bottom up. Works of several historians reveal the moral compromises made by the nation’s early leaders and the fragile nature of the country’s infancy. More significant, they argue that many of the Founding Fathers knew slavery was wrong—and yet most did little to fight it.More than anything, the historians say, the founders were hampered by the culture of their time. While Washington and Jefferson privately expressed distaste for slavery, they also understood that it was part of the political and economic bedrock of the country they helped to create.For one thing, the South could not afford to part with its slaves. Owning slaves was “like having a large bank account,” says Wiencek, auth or of An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America. The southern states would not have signed the Constitution without protections for the “peculiar institution,” including a clause that counted a slave as three fifths of a man for purposes of congressional representation.And the statesmen’s political lives depended on slavery. The three-fifths formula handed Jefferson his narrow victory in the presidential election of 1800 by inflating the votes of the southern states in the Electoral College. Once in office, Jefferson extended slavery with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803; the new land was carved into 13 states, including three slave states.Still, Jefferson freed Hemings’s children—though not Hemings herself or his approximately 150 other slaves. Washington, who had begun to believe that all men were created equal after observing the bravary of the black soldiers during the Revolutionary War, overcame the strong opposition of his relatives to grant his slaves their freedom in his will. Only a decade earlier, such an act would have required legislative approval in Virginia.36. George Washington’s dental surgery is mentioned to .[A] show the primitive medical practice in the past.[B] demonstrate the cruelty of slavery in his days.[C] stress the role of slaves in the U.S. history.[D] reveal some unknown aspect of his life.37. We may infer from the second paragraph that .[A] DNA technology has been widely applied to history research.[B] in its early days the U.S. was confronted with delicate situations.[C] historians deliberately made up some stories of Jefferson’s life.[D] political compromises are easily found throughout the U.S. history.38. What do we learn about Thomas Jefferson?[A] His political view changed his attitude towards slavery.[B] His status as a father made him free the child slaves.[C] His attitude towards slavery was complex.[D] His affair with a slave stained his prestige.39. Which of the following is true according to the text?[A] Some Founding Fathers benefit politically from slavery.[B] Slaves in the old days did not have the right to vote.[C] Slave owners usually had large savings accounts.[D] Slavery was regarded as a peculiar institution.40. Washington’s decision to free slaves originated from his .[A] moral considerations.[B] military experience.[C] financial conditions.[D] political stand.Part BDirections:In the following text, some segments have been removed. For Questions 41-45, choose the most suitable one from the list A-G to fit into each ofthe numbered blanks. There are two extra choices, which do not fit in any of the blanks. Mark your answers on ANSWER SHEET 1. (10 points)The time for sharpening pencils, arranging your desk, and doing almost anything else instead of writing has ended. The first draft will appear on the page only if you stop avoiding the inevitable and sit, stand up, or lie down to write. (41)_______________.Be flexible. Your outline should smoothly conduct you from one point to the next, but do not permit it to railroad you. If a relevant and important idea occurs to you now, work it into the draft. (42) _______________. Grammar, punctuation, and spelling can wait until you revise. Concentrate on what you are saying. Good writing most often occurs when you are in hot pursuit of an idea rather than in a nervous search for errors.(43) _______________. Your pages will be easier to keep track of that way, and, if you have to clip a paragraph to place it elsewhere, you will not lose any writing on either side.If you are working on a word processor, you can take advantage of its capacity to make additions and deletions as well as move entire paragraphs by making just a few simple keyboard commands. Some software programs can also check spelling and certain grammatical elements in your writing. (44) _______________. These printouts are also easier to read than the screen when you work on revisions.Once you have a first draft on paper, you can delete material that is unrelated to your thesis and add material necessa ry to illustrate your points and make your paper convincing. The student who wrote “The A&P as a Stateof Mind” wisely dropped a paragraph that questioned whether Sammy displays chauvinistic attitudes toward women. (45) _______________.Remember that your initial draft is only that. You should go through the paper many times—and then again—working to substantiate and clarify your ideas. You may even end up with several entire versions of the paper. Rewrite. The sentences within each paragraph should be related to a single topic. Transitions should connect one paragraph to the next so that there are no abrupt or confusing shifts. Awkward or wordy phrasing or unclear sentences and paragraphs should be mercilessly poked and prodded into shape.[A] To make revising easier, leave wide margins and extra space between lines so that you can easily add words, sentences andcorrections. Write on only one side of the paper.[B] After you have already and adequately developed the body of your paper, pay particular attention to the introductory and concluding paragraphs. It’s probably best to write the introduction last, after you know precisely what you are introducing. Concluding paragraphs demand equal attention because they leave the reader with a final impression.[C] It’s worth remembering, however, that though a clean copy fresh off a printer may look terrible, it will read only as well as the thinking and writing that have gone into it. Many writers prudently store their data on disks and print their pages each time they finish a draft to avoid losing any material because of power failures or other problems.[D] It makes no difference how you write, just so you do. Now that you have developed a topic into a tentative thesis, you can assemble your notes and begin to flesh out whatever outline you have made.[E] Although this is an interesting issue, it has nothing to do with the thesis, which explains how the setting influences Sammy’s decision to quit his job. Instead of including that paragraph, she added one that d escribed Lengel’s crabbed response to the girls so that she could lead up to the A & P “policy” he enforces.[F] In the final paragraph about the significance of the setting in “A&P” the student brings together the reasons Sammy quit his job by referring t o his refusal to accept Lengel’s store policies.[G] By using the first draft as a means of thinking about what you want to say, you will very likely discover more than your notes originally suggested. Plenty of good writers don’t use outlines at all but discover ordering principles as they write. Do not attempt to compose a perfectly correct draft the first time around.Part CDirections:Read the following text carefully and then translate the underlined segments into Chinese. Your translation should be written neatly on ANSWER SHEET 2. (10 points)In his autobiography,Darwin himself speaks of his intellectualpowers with extraordinary modesty. He points out that he always experienced much difficulty in expressing himself clearly and concisely, but (46)he believes that this very difficulty may have had the compensating advantage of forcing him to think long and intently about every sentence, and thus enabling him to detect errors in reasoning and in his ownPart A51. Directions:You have just come back from Canada and found a music CDin your luggage that you forgot to return to Bob, your landlord there. Write him a letter to1) make an apology, and2) suggest a solution.You should write about 100 words on ANSWER SHEET 2.Do not sign your own name at the end of the letter. Use “Li Ming” instead.Do not write the address. (10 points)Part B52. Directions:Write an essay of 160-200 words based on the following drawing. In your essay, you should1) describe the drawing briefly,2) explain its intended meaning, and then3) give your comments.You should write neatly on ANSHWER SHEET 2. (20 points)2023年全国硕士硕士招生考试英语(一)答案详解Section I Use of English一、文章总体分析这是一篇议论文。

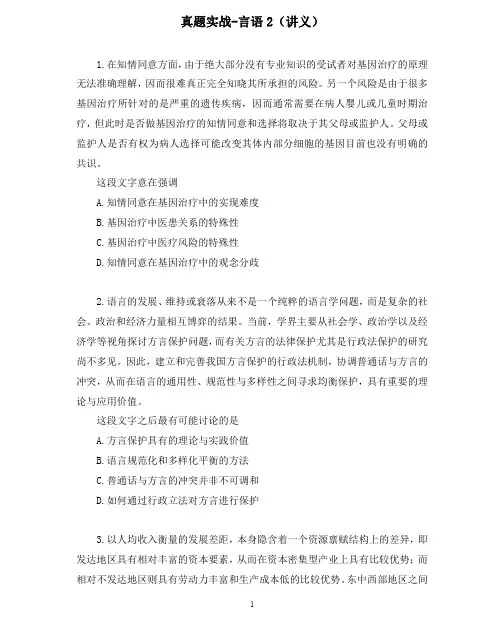

真题实战-言语2(讲义)1.在知情同意方面,由于绝大部分没有专业知识的受试者对基因治疗的原理无法准确理解,因而很难真正完全知晓其所承担的风险。

另一个风险是由于很多基因治疗所针对的是严重的遗传疾病,因而通常需要在病人婴儿或儿童时期治疗,但此时是否做基因治疗的知情同意和选择将取决于其父母或监护人。

父母或监护人是否有权为病人选择可能改变其体内部分细胞的基因目前也没有明确的共识。

这段文字意在强调A.知情同意在基因治疗中的实现难度B.基因治疗中医患关系的特殊性C.基因治疗中医疗风险的特殊性D.知情同意在基因治疗中的观念分歧2.语言的发展、维持或衰落从来不是一个纯粹的语言学问题,而是复杂的社会、政治和经济力量相互博弈的结果。

当前,学界主要从社会学、政治学以及经济学等视角探讨方言保护问题,而有关方言的法律保护尤其是行政法保护的研究尚不多见。

因此,建立和完善我国方言保护的行政法机制,协调普通话与方言的冲突,从而在语言的通用性、规范性与多样性之间寻求均衡保护,具有重要的理论与应用价值。

这段文字之后最有可能讨论的是A.方言保护具有的理论与实践价值B.语言规范化和多样化平衡的方法C.普通话与方言的冲突并非不可调和D.如何通过行政立法对方言进行保护3.以人均收入衡量的发展差距,本身隐含着一个资源禀赋结构上的差异,即发达地区具有相对丰富的资本要素,从而在资本密集型产业上具有比较优势;而相对不发达地区则具有劳动力丰富和生产成本低的比较优势。

东中西部地区之间存在的资源禀赋结构差异,无疑可以成为中西部地区经济发展赶超的机遇。

下列说法与文意不符的是A.不同地区资源禀赋的差异有利有弊B.发达地区相对来说劳动力比较缺乏C.中西部可以利用劳动力丰富的优势D.资本密集型产业多集中在东部地区4.城镇化是一个长期的历史过程。

在这个过程中,既有人口从农村向城镇迁移的正向城镇化,也不可避免地会出现农民工返乡等逆城镇化现象。

通过加快户籍制度改革,促进农业转移人口市民化,可以保证城镇化持续推进;同时,实施乡村振兴战略,不仅可以为农村人才和劳动力创造更广阔的用武之地,也使城镇化的推进更加行稳致远。

![(NEW)[答案]尔雅答案大脑的奥秘](https://uimg.taocdn.com/4720ce5b3968011ca300917e.webp)

1.11 [判断题] 具备生命特征的所有动物都有大脑。

()我的答案: ×2 [判断题] 裂脑人是由于外科手术造成两侧大脑相互独立工作。

()我的答案:√3 [判断题] 人对自我,对他人,对社会的看法是社会学层次的讨论对象,难以用脑这一自然科学研究对象来表现。

()我的答案: ×4 [判断题] 传统的东方人和西方人对家庭和亲人的看法有所不同,它们可以在特定的脑区找到不同的激活方式。

()我的答案:√1.21 [判断题] 现代科学技术可以用光来控制神经细胞的反应,可以控制特定的大脑核团。

()我的答案:√2 [判断题] 隐藏在内心深处的秘密不告诉别人,也没有方法被人破解。

()我的答案: ×3 [判断题] 特定的大脑核团执行特定的任务,它的病变造成功能丧失,表现的症状是相似的。

()我的答案: ×4 [判断题] 脑的生物电信号可以被用来解读,从而控制机器。

()我的答案:√1.31 [单选题] ()可以无损伤地看到大脑的功能活动。

A.单电极记录B.功能核磁共振C.内源信号光学成像D.深度脑刺激我的答案:B2 [单选题] 人脑中有()神经元。

A.1000万B.1亿C.10亿D.100亿我的答案:D3 [单选题] 神经元的细胞体大小为()。

A.1毫米B.1厘米C.10微米D.10纳米我的答案:C4 [判断题] 神经元之间的连接方式一旦建立就不会改变。

()我的答案: ×2.11 [单选题] ()是神经元所不具备的。

A.细胞核B.树突C.细胞壁D.轴突我的答案:C2 [单选题] 髓鞘起到的主要作用是()。

A.传送营养物质B.传送带电离子C.绝缘D.接受电信号我的答案:C3 [单选题] 树突小棘的主要作用是()。

A.传送动作电位B.合成蛋白C.接受其它神经元的输入D.接受外源营养我的答案:C4 [判断题] 神经元的大小形状基本一致。

()我的答案: ×2.21 [单选题] 突触前膜囊泡的释放是由()触发的。

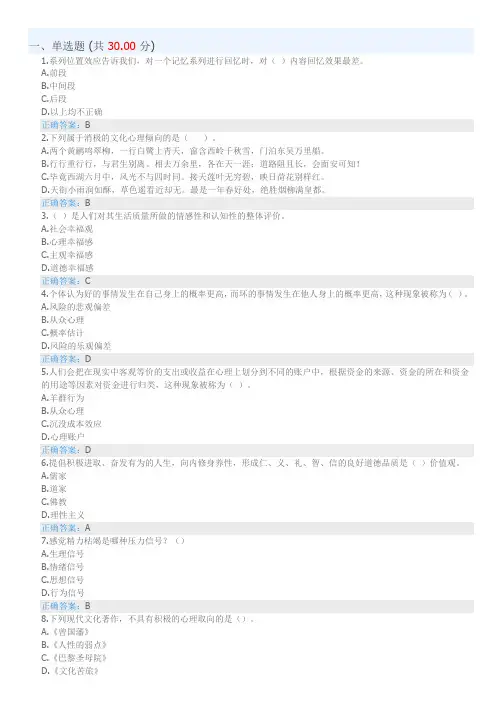

一、单选题 (共30.00分)1.系列位置效应告诉我们,对一个记忆系列进行回忆时,对()内容回忆效果最差。

A.前段B.中间段C.后段D.以上均不正确正确答案:B2.下列属于消极的文化心理倾向的是()。

A.两个黄鹂鸣翠柳,一行白鹭上青天,窗含西岭千秋雪,门泊东吴万里船。

B.行行重行行,与君生别离。

相去万余里,各在天一涯;道路阻且长,会面安可知!C.毕竟西湖六月中,风光不与四时同。

接天莲叶无穷碧,映日荷花别样红。

D.天街小雨润如酥,草色遥看近却无。

最是一年春好处,绝胜烟柳满皇都。

正确答案:B3.()是人们对其生活质量所做的情感性和认知性的整体评价。

A.社会幸福观B.心理幸福感C.主观幸福感D.道德幸福感正确答案:C4.个体认为好的事情发生在自己身上的概率更高,而坏的事情发生在他人身上的概率更高,这种现象被称为()。

A.风险的悲观偏差B.从众心理C.概率估计D.风险的乐观偏差正确答案:D5.人们会把在现实中客观等价的支出或收益在心理上划分到不同的账户中,根据资金的来源、资金的所在和资金的用途等因素对资金进行归类,这种现象被称为()。

A.羊群行为B.从众心理C.沉没成本效应D.心理账户正确答案:D6.提倡积极进取、奋发有为的人生,向内修身养性,形成仁、义、礼、智、信的良好道德品质是()价值观。

A.儒家B.道家C.佛教D.理性主义正确答案:A7.感觉精力枯竭是哪种压力信号?()A.生理信号B.情绪信号C.思想信号D.行为信号正确答案:B8.下列现代文化著作,不具有积极的心理取向的是()。

A.《曾国藩》B.《人性的弱点》C.《巴黎圣母院》D.《文化苦旅》正确答案:C9.根据巴甫洛夫的高级神经活动类型说,与强、平衡、灵活相对应的是下列那种气质类型()。

A.多血质B.胆汁质C.抑郁质D.粘液质正确答案:A10.鲁迅说:不读(),不知中国文化,不知人生真谛,可见其在中国文化中的重要性。

A.《大学》B.《中庸》C.《论语》D.《道德经》正确答案:D11.人格四个特性中,最能反映人格是否健康的特征是()。

翻译作业要求:手工书写,在正文中注明图片文字说明;写好姓名,学号,班级,信息不完整扣5分不能抄袭,抄袭者与被抄袭者均作不及格处理;2010年11月29日交作业,过期不交视为放弃该项成绩。

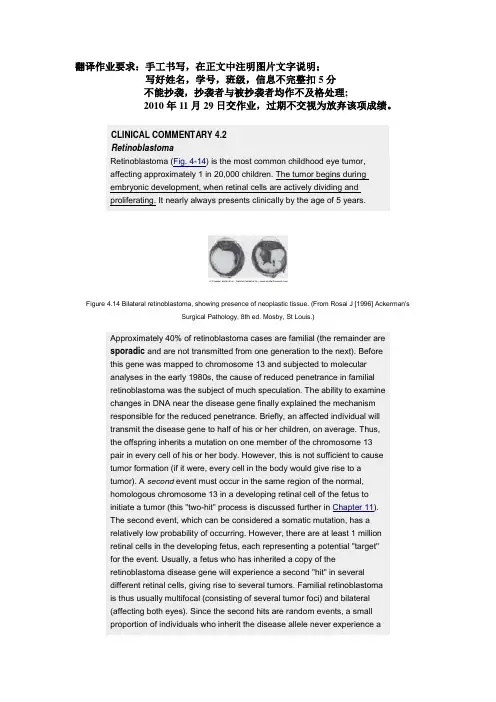

CLINICAL COMMENTARY 4.2RetinoblastomaRetinoblastoma (Fig. 4-14) is the most common childhood eye tumor,affecting approximately 1 in 20,000 children. The tumor begins duringembryonic development, when retinal cells are actively dividing andproliferating. It nearly always presents clinically by the age of 5 years.Figure 4.14 Bilateral retinoblastoma, showing presence of neoplastic tissue. (From Rosai J [1996] Ackerman'sSurgical Pathology, 8th ed. Mosby, St Louis.)Approximately 40% of retinoblastoma cases are familial (the remainder aresporadic and are not transmitted from one generation to the next). Beforethis gene was mapped to chromosome 13 and subjected to molecularanalyses in the early 1980s, the cause of reduced penetrance in familialretinoblastoma was the subject of much speculation. The ability to examinechanges in DNA near the disease gene finally explained the mechanismresponsible for the reduced penetrance. Briefly, an affected individual willtransmit the disease gene to half of his or her children, on average. Thus,the offspring inherits a mutation on one member of the chromosome 13pair in every cell of his or her body. However, this is not sufficient to causetumor formation (if it were, every cell in the body would give rise to atumor). A second event must occur in the same region of the normal,homologous chromosome 13 in a developing retinal cell of the fetus toinitiate a tumor (this "two-hit" process is discussed further in Chapter 11).The second event, which can be considered a somatic mutation, has arelatively low probability of occurring. However, there are at least 1 millionretinal cells in the developing fetus, each representing a potential "target"for the event. Usually, a fetus who has inherited a copy of theretinoblastoma disease gene will experience a second "hit" in severaldifferent retinal cells, giving rise to several tumors. Familial retinoblastomais thus usually multifocal (consisting of several tumor foci) and bilateral(affecting both eyes). Since the second hits are random events, a smallproportion of individuals who inherit the disease allele never experience asecond hit in any retinal cell. They do not develop a retinoblastoma. Therequirement for a second hit thus explains the reduced penetrance seen inthis disorder.The retinoblastoma gene has been cloned and sequenced, and thefunction of its gene product, pRb, has been studied extensively. A majorfunction of pRb, when hypophosphorylated, is to bind and inactivate E2F, anuclear transcription factor. The cell requires active E2F to proceed fromthe G1 to the S phase of mitosis. By inactivating E2F, pRb applies a"brake" to the cell cycle. When cell division is required, pRb isphosphorylated by cyclin-dependent kinases (see Chapter 2).Consequently, E2F is released by pRb and thus activated. A mutation inpRb can cause permanent loss of the E2F-binding capacity, and the cell,having lost its brake, will undergo uncontrolled proliferation leading to atumor. Because of its controlling effect on the cell cycle, the Rb genebelongs to a class of genes known as tumor suppressors (see Chapter11).If untreated, retinoblastomas can grow to considerable size. Fortunately,these tumors are now usually detected and treated before they becomelarge. If found early enough through ophthalmological examination, thetumor may be treated successfully with radiation, cryotherapy (freezing), orlaser photocoagulation. In more advanced cases, enucleation (removal) ofthe eye is necessary. Because individuals with familial retinoblastoma haveinherited a chromosome 13 mutation in all cells of their body, they are alsosusceptible to other types of cancers later in life. In particular, about 15% ofthose who inherit the mutation later develop osteosarcomas (malignantbone tumors). Careful monitoring for subsequent tumors and avoidance ofagents that could produce a second hit (e.g., radiation) are thus importantaspects of management for the patient with familial retinoblastoma.CLINICAL COMMENTARY 4.3Huntington DiseaseHuntington disease (HD) affects approximately 1 in 20,000 persons ofEuropean descent. It is substantially less common among Japanese andAfricans. The disorder usually presents between the ages of 30 and 50years, although it has been observed as early as 2 years of age and as lateas 80 years of age.HD is characterized by a progressive loss of motor control and bypsychiatric problems, including dementia and affective disorder. There is asubstantial loss of neurons in the brain, detectable by imaging techniquessuch as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Decreased glucose uptake inthe brain, an early sign of the disorder, can be demonstrated bypositron-emission tomography (PET). Although many parts of the brain areaffected, the area most noticeably damaged is the corpus striatum. In some patients the disease leads to a loss of 25% or more of total brain weight (Fig. 4-16).The clinical course of HD is protracted. Typically, the interval from initial diagnosis to death is approximately 15 years. As in many neurological disorders, patients with HD experience difficulties in swallowing; aspiration pneumonia is the most common cause of death. Cardiorespiratory failure and subdural hematoma (due to head trauma) are other frequent causes of death. The suicide rate among HD patients is several times higher than that in the general population. Treatment includes the use of drugs such as benzodiazepines to help control the choreic movements. Affective disturbances, which are seen in nearly half of the patients, are sometimes controlled with antipsychotic drugs and tricyclic antidepressants. Although these drugs help to control some of the symptoms of HD, there is currently no way to alter the outcome of the disease.HD is notable in that affected homozygotes appear to display exactly the same clinical course as heterozygotes (in contrast to most dominant disorders, in which homozygotes are more severely affected). This attribute, and the fact that mouse models in which one copy of the gene is inactivated are perfectly normal, support the hypothesis that the mutation causes a gain of function (see Chapter 3). In more than 95% of cases, the mutation is inherited from an affected parent. HD has the distinction of being the first genetic disease mapped to a specific chromosome using an RFLP marker. James Gusella and colleagues mapped the disease gene to a region on the distal short arm of chromosome 4 in 1983.After 10 years of work by a large number of investigators, the disease gene was cloned. DNA sequence analysis showed that the mutation is a CAG expanded repeat (see Chapter 3) located within the coding portion of the gene. The normal repeat number ranges from 10 to 26. Individuals with 27 to 35 repeats are unaffected but are more likely to transmit a still larger number of repeats to their offspring. The inheritance of 36 or more copies of the repeat can produce disease, although incomplete penetrance of the disease phenotype is seen in those who have 36 to 41 repeats. As in many disorders caused by trinucleotide repeat expansion, a larger number of repeats is correlated with earlier age of onset of the disorder. Also, there is a tendency for greater repeat expansion when the father, rather than the mother, transmits the disease gene. This helps to explain the difference in ages of onset for maternally and paternally transmitted disease seen in Fig. 4-15. In particular, 80% of cases with onset before 20 years of age (termed "juvenile Huntington disease") are paternally transmitted, and these cases are accompanied by especially large repeat expansions. It remains to be seen why the degree of repeat instability in the HD gene is greater in paternal transmission than in maternal transmission.Cloning of the HD gene led quickly to the identification of the gene product,huntingtin. This protein is involved in the transport of vesicles in cellularsecretory pathways. In addition, there is evidence that huntingtin isnecessary for the normal production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor.The CAG repeat expansion produces a lengthened series of glutamineresidues near huntingtin's amino terminal. Although the precise role of theexpanded glutamine tract in disease causation is unclear, recent studiesshow that it leads to a buildup of toxic protein aggregates within and nearneuronal nuclei. This buildup is associated with the early neuronal deaththat is characteristic of HD.Figure 4.16 Cross section of the brain of an adult with Huntington disease, illustrating marked striatal atrophy.(Courtesy Dr. Jeanette Townsend, University of Utah Health Sciences Center.)page 72CLINICAL COMMENTARY 4.5Marfan Syndrome: An Example of PleiotropyFigure 4.18 A, A young man with Marfan syndrome, showing characteristically long limbs and narrow face. B,Arachnodactyly in an 8-year-old girl with Marfan syndrome.page 75page 76 ▪ Marfan syndrome (Fig. 4-18) is an autosomal dominant condition seen inapproximately 1 of every 10,000 North Americans. It is characterized bydefects in three major systems: ocular, skeletal, and cardiovascular. Theocular defects include myopia, which is present in most patients withMarfan syndrome, and displaced lens (ectopia lentis), which is observed inabout half of the patients. The skeletal defects include dolichostenomelia(unusually long and slender limbs), pectus excavatum ("hollow chest"),pectus carinatum ("pigeon chest"), scoliosis, and arachnodactyly (literally"spider fingers," denoting the characteristically long, slender fingers).Marfan patients also typically exhibit joint hypermobility. The mostlife-threatening defects are those of the cardiovascular system. Mostpatients with Marfan syndrome develop prolapse of the mitral valve, acondition in which the cusps of the mitral valve protrude upward into the leftatrium during systole. This can result in mitral regurgitation (leakage ofblood back into the left atrium from the left ventricle). Mitral valve prolapse, however, is seen in 1% to 3% of the general population and is often of little consequence. Much more serious is dilatation (widening) of the ascendingaorta, which is seen in 90% of Marfan patients. As dilatation increases, theaorta becomes susceptible to dissection or rupture, particularly whencardiac output is high (as in heavy exercise or pregnancy). As the aortawidens, the left ventricle enlarges, and cardiomyopathy (damage to theheart muscle) ensues. The end result is congestive heart failure, a frequentcause of death among Marfan syndrome patients.All of these defects involve excessively "stretchy" connective tissue. Therole of connective tissue is apparent for defects such as aortic dilatationand detached lens. Its role in skeletal defects is mediated by theperiosteum, the connective tissue that covers bone and provides anoppositional force in normal bone growth. When the periosteum is moreelastic than it should be, overgrowth of bone occurs, resulting in skeletaldefects.Body_ID: PB04044 What is the basis of the connective tissue disorder? Answers are beingprovided by the discovery that patients with Marfan syndrome havemutations of the chromosome 15 gene that encodes fibrillin, a connectivetissue protein. Fibrillin, a major component of microfibrils, is found in theaorta, the suspensory ligament of the lens, and the periosteum. Thelocation of the gene product and its role as a component of connectivetissue nicely explain the pleiotropic effects that cause disturbances in theeye, the skeleton, and the cardiovascular system.Body_ID: PB04045 Several hundred different fibrillin mutations have been identified in Marfan syndrome patients. Most of these are missense mutations, but frameshiftsand nonsense mutations producing a truncated fibrillin protein are alsoseen. In many cases, the missense mutations produce a more severedisease phenotype because of a dominant negative effect (i.e., theabnormal fibrillin proteins bind to and disable many of the normal fibrillinproteins produced by the normal allele in a heterozygote). A severeneonatal form of the disease is produced by mutations in exons 24 to 32. Atleast one Marfan syndrome compound heterozygote has been reported. This infant, who inherited a disease-causing allele from each of its affected heterozygous parents, had severe congestive heart failure and died from cardiac arrest at the age of 4 months.Specific mutations in the fibrillin gene can cause familial arachnodactyly (with no other symptoms of Marfan syndrome), while others can cause familial ectopia lentis. Mutations in a second fibrillin gene, located on chromosome 5, cause a disease called "congenital contractural arachnodactyly." This condition shares many of the skeletal features of Marfan syndrome but does not involve cardiac or ocular defects. Treatment for Marfan syndrome includes regular ophthalmological examinations and, for individuals with aortic dilatation, the avoidance of heavy exercise and contact sports. In addition, β-adrenergic blockers (e.g., propranolol) can be administered to decrease the strength and abruptness of heart contractions. This reduces stress on the aorta. In some cases, the aorta and aortic valve are surgically replaced with a synthetic tube and artificial valve. With such treatment, individuals with Marfan syndrome can now look forward to nearly normal life spans.A number of historical figures are thought to have possibly had Marfan syndrome, including Niccolo Paganini, the violinist, and Sergei Rachmaninoff, the composer and pianist. Most controversial is the proposal that Abraham Lincoln may have had Marfan syndrome. He had skeletal features consistent with the disorder, and examination of his medical records has shown that he may well have had aortic dilatation. Some have suggested that he was in congestive heart failure at the time of his death and that, had he not been assassinated, he still would not have survived his second term of office. Lincoln has no living descendants who could be evaluated for Marfan syndrome. However, samples of his blood, bone, and hair have been preserved. Once the specific mutations for Marfan syndrome are better characterized, it may be possible, using the polymerase chain reaction, to amplify DNA from these specimens. DNA sequencing could then be used to determine whether Lincoln had Marfan syndrome.While this may seem like a silly exercise to some, it should be pointed out that genetic diseases such as Marfan syndrome are frequently viewed as serious impediments to success. To find that one of the greatest Presidents in United States history had this disorder would be an eloquent reply.。

⼈⼯智能,语⾔与伦理-⽹课答案中间神经元⽹络的层次很多2. 单选题从儒家的⽴场来看,德性是靠( )的。

熏养3. 单选题实际的翻译中有时要破坏句⼦原有的句法结构,根据( )重新组织句⼦。

意义4. 单选题⾦⾕武洋认为⽇本⼈是( )看待世界的。

⾍⼦的视⾓5. 单选题把归纳逻辑抬到⽐较⾼的位置的哲学家是( )。

⼤卫·休谟6. 单选题在⼈⼯智能的所有⼦课题中,所牵涉范围最⼴的是( )⾃然语⾔处理7. 单选题机械主义的说明⽅式不能囊括⼈类的( )。

感觉8. 单选题SHRDLU系统实际上是⼀个( )。

积⽊系统9. 单选题( )⽆法得知,因为他⼈的⾏为和表现有伪装性。

“他⼼”10. 单选题弱⼈⼯智能是指仅仅模拟⼈类⼤脑的( );强⼈⼯智能是指其本⾝就是⼀个( )。

智能;⼼智11. 单选题深度学习的实质是( )。

映射机制12. 单选题框架与框架之间的粘接剂叫做( )。

框间关系13. 单选题影响基于中间语的机器翻译思路的哲学家是( )。

莱布尼茨14. 单选题深度学习的数据材料来源于( )。

互联⽹15. 单选题语⾔不仅仅是句法问题,更是()的问题。

⾳韵16. 单选题提出强⼈⼯智能与弱⼈⼯智能的⼈是( )。

约翰·塞尔17. 单选题塞尔论证的合法性前提是,他的中⽂屋系统和⼀般的计算机系统之间是( )。

同构的18. 单选题计算机之⽗是( )。

艾伦·图灵19. 单选题⼈⼯智能作为⼀门学科的建⽴时间是( )。

1956年20. 单选题德性论者关⼼的是( )。

道德主体21. 单选题击靶德性论致⼒于将“德性”兑换成平时我们所经常⽤到的( )。

德性名⽬映射机制23. 单选题提出强⼈⼯智能与弱⼈⼯智能的⼈是( )。

约翰·塞尔24. 单选题下列属于基于统计的⾃然语⾔处理进路的是( )。

基于贝叶斯公式25. 单选题( )的思想激发了基于中间语的机器翻译思路。

莱布尼茨26. 单选题( )是⾮常接近欧陆现象学运动的语⾔学流派。

全国自然科学名词审定委员会公布的《医学名词》,按英文字母顺序排列Aabsence seizure:失神发作acalculia:失算[症]acute disseminated encephalomyelitis:急性播散性脑脊髓炎adiadochokinesia:轮替动作不能Adie syndrome: 埃迪综合征adrenoleukodystrophy:肾上腺脑白质营养不良adversive seizure:旋转性发作ageusia:味觉缺失agnosia:失认[症]agraphia:失写[症]akinesia:运动不能akinetic mutism:运动不能性缄默[症]akinetic seizure:无动性发作Alexander disease:亚历山大病alexia:失读[症]allochesthesia:感觉定位不能allochiria:感觉定侧不能Alpers disease:阿尔珀斯病Alstrom-Hallgren syndrome: 阿尔斯特伦-海尔格伦综合征alternate hemiplegia:交替性瘫痪Alzheimer disease:阿尔茨海默病amnesia: 遗忘[症]amusia:失乐感[症]amyotonia:肌张力缺失amyotrophic lateral sclerosis:肌萎缩侧索硬化amyotrophy:肌萎缩analgesia:痛觉缺失anarthria:构音不全anesthesia:感觉缺失anesthesia dolorosa:痛性感觉缺失ankle clonus:踝阵挛anosognosia:病感失认[症]anterior cross bulbar syndrome:延髓前交叉综合征anterograde amnesia: 顺行性遗忘Anton syndrome: 安东综合征apathetic dementia:淡漠性痴呆Apert syndrome: 阿佩尔综合征aphasia: 失语[症]apraxia:失用[症]aprosody:失语韵[症]arachnoiditis:蛛网膜炎areflexia:反射消失Arnold-Chiari malformation: 阿诺德-基亚里畸形arrhigosis:冷觉缺失ascending myelitis:上升性脊髓炎associated movement:联合运动astasia abasia:站立行走不能astatic seizure:起立不能发作asterixis:扑翼样震颤asynergia:协同动作不能ataxia:共济失调ataxic gait:共济失调步态athetosis:手足徐动症atonia:张力缺失atonic seizure:失张力发作atopognosia:位置失认[症]atypical absence seizure:非典型失神发作auditory agnosia:听觉失认[症]auditory evoked potential, AEP:听觉诱发电位aura:先兆auriculo-temporal syndrome:耳颞综合征automatism:自动症autotopagnosia:自身部位失认[症]Avellis syndrome: 阿韦利斯综合征BBabinski sign: 巴宾斯基征Babinski-Nageotte syndrome: 巴宾斯基-纳若特综合征background activity:背景活动Bailey-Cushing syndrome:贝利-库欣综合征Balint syndrome:巴林特综合征ballism:投掷症Balo disease:巴洛病,又称“同心圆性硬化”(concentric sclerosis) baragnosis:重量失认[症]Barré pyramidal sign: 巴雷锥体束征Bechterew sign: 别赫捷列夫征Becker muscular dystrophy:贝克肌营养不良Beevor sign:比弗征Benedikt syndrome: 贝内迪克特综合征Bielschowsky-Jansky disease:比-扬病Binswanger disease:宾斯旺格病,又称“进行性白质脑病” Bornholm disease: 博恩霍尔姆病bradykinesia:运动徐缓bradylalia:言语徐缓brain death: 脑死亡brainstem auditory evoked potential, BAEP:脑干听觉诱发电位Brown-Séquard syndrome:布朗-塞卡尔综合征Brudzinski sign:布鲁津斯基征Bruns syndrome:布伦斯综合征bulbar paralysis, bulbar palsy:延髓性麻痹burst suppression:爆发抑制DDandy-Walker syndrome:丹迪-沃克综合征decorticate rigidity:去皮质强直decrement response:递减反应Dejerine-Klumpke syndrome: 德热里纳-克隆普克综合征Dejerine-Roussy syndrome:德热里纳-鲁西综合征Dejerine-Sottas disease:德热里纳-索塔斯dementia:痴呆dementia agitata:激越性痴呆demyelination:脱髓鞘denervation potential:去神经电位depth electroencephalogram:深部脑电图depth electroencephalography:深部脑电图学diencephalosis:间脑病diplegia:双侧瘫痪distal latency:远端潜伏期dizziness:头晕drop attack:跌倒发作drunken gait:酒醉步态Duchenne muscular dystrophy: 迪谢内肌营养不良Duchenne-Erb syndrome:迪谢内-埃尔布综合征dysarthria:构音困难dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome:构音困难手笨拙综合征dysdiadochokinesia:轮替运动困难dysesthesia:感觉迟钝dysgeusia:味觉障碍dysgraphia:书写困难dyskinesia:运动障碍dyslalia: 言语困难dyslexia:诵读困难dysmetria:辨距困难dysmyotonia:肌张力障碍dyspraxia:运用障碍dyssynergia:协同动作障碍dystonia:张力失常dystonia musculorum deformans:畸形性肌张力障碍Eelectrocorticogram:脑皮层电图electrocorticography:脑皮层电图学electroencephalogram:脑电图electroencephalography:脑电图学electromyelography:脊髓电图学electromyogram:肌电图electromyography, EMG:肌电图学electroneurography:神经电图学electrothalamogram:丘脑电图encephalitis:脑炎encephalomyelitis:脑脊髓炎encephalopathy:脑病end plate noise:终板噪声end plate potential:终板电位ependymitis:室管膜炎epilepsy:癫痫epileptic seizure:癫痫发作epileptiform pattern:癫痫样波型essential tremor:特发性震颤event related potential, ERP:事件相关电位Ffacial tic:面肌抽搐,又称“面肌痉挛” fasciculation:肌束震颤Fazio-Londe syndrome:法齐奥-隆德综合征fecal incontinence:大便失禁festination:慌张步态fibrillation:肌纤维震颤flaccid hemiplegia:松弛性偏瘫flaccid paralysis:松弛性瘫痪flash visual evoked potential:闪光视觉诱发电位focal epilepsy:局限型癫痫Foville syndrome:福维尔综合征Friedreich ataxia:弗里德赖希共济失调F-wave:F波GGarcin syndrome:加桑综合征Gaze paralysis:凝视瘫痪generalized epilepsy:全身型癫痫generalized seizure:全身发作Gerstmann syndrome:格斯特曼综合征giant cell arteritis:巨细胞动脉炎giant motor unit action potential:巨大运动单位动作电位global amnesia, total amnesia: 完全性遗忘Gordon sign:戈登征grand mal:大发作graphanesthesia:皮肤书写觉缺失Guillain-Barré syndrome:吉兰-巴雷综合征HH reflex:H反射Hallervorden-Spatz disease: 哈勒沃登-施帕茨病headache:头痛hemianesthesia:偏侧感觉缺失hemiatrophy:偏侧萎缩hemiballismus:偏侧投掷症hemichorea:偏侧舞蹈症hemifacial spasm:偏侧面肌痉挛hemihypertrophy:偏侧肥大hemiparesis:轻偏瘫hemiplegia:偏瘫hemiplegic gait:偏瘫步态hereditary cerebellar ataxia:遗传性小脑共济失调Hoffmann sign:霍夫曼征Horner syndrome:霍纳综合征Hunt disease: 亨特病Huntington disease:亨廷顿病hypalgesia:痛觉减退hyperalgesia:痛觉过敏hyperhidrosis:多汗hyperkinesia:运动过度hyperostosis frontalis interna:额骨内板增生症hyperpathia:痛觉过度hyperreflexia:反射亢进hypersexuality:性欲亢进hypertonia:张力过高hypesthesia:感觉减退hypogeusia:味觉减退hypohidrosis:少汗hypokinesia:运动减少hyporeflexia:反射减弱hypothalamic syndrome:下丘脑综合征hypotonia:张力过低Iideational apraxia:观念性失用[症]ideokinetic apraxia:观念运动性失用[症]idiopathic epilepsy:特发性癫痫imitative synkinesia:模仿性联带运动incontinence:失禁incoordination:动作失调injury potential:损伤hypersomnia:睡眠过度电位intentional tremor:意向性震颤internuclear ophthalmoplegia:核间性眼肌瘫痪intracranial venous thrombosis:颅内静脉血栓形成Isaac syndrome:艾萨克综合征JJackson epilepsy:杰克逊癫痫Jackson syndrome:杰克逊综合征jargon aphasia:杂乱性失语[症]jitter:颤抖Joseph disease:约瑟夫病jugular foramen syndrome:颈静脉孔综合征Khypsarrhythmia:高度节律失调Kearns-Sayre syndrome:卡恩斯-塞尔综合征Kernig sign:凯尔尼格征Kinetic tremor:动作性震颤Klippel-Feil disease:克利佩尔-费尔病Kocher-Debr-Semelaign syndrome:科克-德布雷-塞梅莱涅综合征Krabbe disease:克拉伯病Kufs disease:库夫斯病Kugelberg-Welander disease:库格尔贝格-韦兰德病Kuru disease:库鲁病LLafora disease:拉福拉病Lambert-Eaton syndrome:兰伯特-伊顿综合征Landry paralysis:兰德里瘫痪laryngeal crisis:喉危象Lasgue sign:拉塞格征late response:迟发反应Leber disease:莱伯病Leigh disease:利氏病Leri sign:莱里征lethargy:嗜睡leukoencephalitis:白质脑炎Lhermitte sign:莱尔米特征locked-in syndrome:闭锁综合征Luft disease:勒夫特病luxury perfusion syndrome:过度灌注综合征MMacEwen sign:麦克尤恩征Marinesco-Sjgren syndrome:马里内斯科-舍格伦综合征Mayer sign: 迈耶征McArdle disease:麦卡德尔病megaconial myopathy:大锥状颗粒肌病meningism:假性脑[脊]膜炎meningitis:脑[脊]膜炎meningoencephalitis:脑膜脑炎meningomyelitis:脊膜脊髓炎Menkes disease:门克斯病又称“钢发综合征(steely hair syndrome)” metachromatic leukodystrophy:异染性脑白质营养不良micturition syncope:排尿晕厥migraine:偏头痛Millard-Gubler syndrome: 米亚尔-居布勒综合征mirror writing:镜像书写mitochondrial myopathy:线粒体肌病Mollaret meningitis:莫拉雷脑[脊]膜炎monoballismus:单肢投掷症mononeuritis:单神经炎monoplegia:单瘫Moro reflex:莫罗反射motor aphasia:运动性失语[症]motor apraxia:运动性失用[症]motor nerve conduction velocity:运动神经传导速度motor unit action potential:运动单位动作电位motor unit potential:运动单位电位multilead electrode:多导电极multiple sclerosis:多发性硬化multiple spike and slow wave complex:多棘慢复合波muscular hypertrophy:肌肥大myalgia:肌痛myasthenia:肌无力myasthenia gravis:重症肌无力myelitis:脊髓炎myelopathy:脊髓病myoclonic epilepsy:肌阵挛型癫痫myoclonic seizure:肌阵挛发作myoclonus:肌阵挛myokymia:肌纤维颤搐myopathy:肌病myositis:肌炎myositis ossificans:骨化性肌炎myotonia:肌强直myotonia atrophica:萎缩性肌强直myotonic potential:肌强直电位myotubular myopathy:肌管性肌病M-wave:M波Nnarcolepsy:发作性睡病nascent motor unit action potential:新生运动单位动作电位nasopharyngeal electrode:鼻咽电极necrotic myelitis:坏死性脊髓炎needle electrode:针电极nemaline myopathy, rod myopathy:线状体肌病,又称“棒状体肌病” neuralgia:神经痛neuritis:神经炎neurology:神经病学neuromyositis:神经肌炎neuromyotonia:神经性肌强直neuropathy:神经病nodding spasm, spasmus nutans:点头痉挛nominal aphasia:命名性失语[症]Nothnagel sign:诺特纳格尔征Nothnagel syndrome:诺特纳格尔综合征nuclear ophthalmoplegia:核性眼肌瘫痪nystagmus:眼震Oocular bobbing:眼球浮动oculocephalogyric reflex:头眼反射oculogyric crisis:眼动危象oculogyric spasm:旋眼痉挛olivopontocerebellar atrophy:橄榄体脑桥小脑萎缩Oppenheim sign:奥本海姆征optical neuromyelitis:视神经脊髓炎orbicularis sign:眼轮匝肌征Ppalatal myoclonus:软腭阵挛pallanesthesia:振动觉缺失palmomental reflex:掌颏反射palsy, paralysis:麻痹,瘫痪paraesthesia:感觉异常parageusia:味觉倒错paralexia:错读[症]paramyotonia:副肌强直paraparesis:轻截瘫paraphasia:错语[症]paraplegia:截瘫parasomnia:深眠状态paresis:轻瘫Parinaud syndrome:帕里诺综合征Parkinson disease:帕金森病,又称“震颤麻痹”partial seizure:部分发作patellar clonus:髌阵挛Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease:佩利措伊斯-梅茨巴赫病,简称“佩-梅病” pendular reflex:钟摆样反射periodic paralysis:周期性瘫痪petit mal:小发作phantom limb:幻肢phantom sensation:幻感觉phantom spike and slow wave complex:幻影棘慢复合波photo convulsive response:光惊厥反应photo myoclonic response:光肌阵挛反应photo paroxysm response:光阵发反应Pick disease:皮克病pill rolling tremor:捻丸样震颤planotopokinesia:空间定位障碍polymyoclonus:多肌阵挛polymyositis:多肌炎polyneuritis:多神经炎polyneuropathy:多神经病polyradiculitis:多神经根炎positive sharp wave:正尖波postinfectious encephalomyelitis:感染后脑脊髓炎postvaccinal encephalomyelitis:疫苗接种后脑脊髓炎primary lateral sclerosis:原发性侧索硬化progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy:进行性多灶性白质脑病progressive muscular dystrophy:进行性肌营养不良progressive spinal muscular atrophy:进行性脊髓性肌萎缩progressive stroke:进行性[脑]卒中pronation sign:旋前征prosopagnosia:面容失认[症]pseudoataxia:假[性]共济失调pseudoathetosis:假[性]手足徐动症pseudobulbar paralysis, pseudobulbar palsy:假[性]延髓性麻痹pseudohypertrophy:假[性]肥大pseudomyotonia:假性肌强直psychogenic headache:心因性头痛psychomotor epilepsy:精神运动型癫痫pyramidal sign:锥体束征Qquadriplegia:四肢瘫痪Queckenstedt test:奎肯施泰特试验(简称奎氏试验)Rradiculitis:神经根炎Raymond Cestan syndrome:蕾蒙*塞斯唐综合征reflex epilepsy:反射性癫痫Refsum disease:雷夫叙姆病restless leg syndrome:下肢不宁综合征retrograde amnesia:逆行性遗忘reverse steal phenomenon:反盗血现象reversible ischemic attack:可逆性脑缺血发作rhythm:节律μ-rhythm:μ节律rigidity:强直Riley-Day syndrome:赖利-戴综合征Romberg sign:龙贝格征Rossolimo sign:罗索利莫征SSantavuori disease:桑塔沃里病Schilder disease:希尔德病,又称“弥漫性硬化(diffuse sclerosis)” Schmidt syndrome:施密特综合征sciatica, ischialgia:坐骨神经痛Seitelberger disease:赛特贝格病sensory aphasia:感觉性失语[症]sensory nerve conduction velocity:感觉神经传导速度sharp and slow wave complex, sharp and wave complex:尖慢复合波sharp wave:尖波Shy-Drger syndrome:夏伊-德雷格综合征simple partial seizure:简单部分发作single fiber electromyography:单纤维肌电图学skew deviation:反向偏斜somatosensory evoked potential, SEP:躯体感觉诱发电位spasm:痉挛spasmodic torticollis:痉挛性斜颈spastic ataxic gait:痉挛性共济失调步态spastic gait:痉挛步态spastic hemiplegia:痉挛性偏瘫spasticity:痉挛状态spastic paralysis:痉挛性瘫痪spastic synkinesia:痉挛性联带运动sphenoidal electrode:蝶骨电极spike and slow wave complex, spike and wave complex:棘慢复合波spike wave:棘波spinal evoked potential:脊髓诱发电位static tremor:静止性震颤status epilepticus:癫痫持续状态steal phenomenon:盗血现象steppage gait:跨阈步态stereoanesthesia:立体觉缺失stiff man syndrome:僵人综合征stroke, apoplexy:[脑]卒中Sturge-Weber syndrome:斯特奇-韦伯综合征subacute combined sclerosis:亚急性联合硬化subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, SSPE:亚急性硬化性全脑炎subclavian steal syndrome:锁骨下动脉盗血综合征supranuclear ophthalmoplegia:核上性眼肌瘫痪synkinesia:联带运动syringobulbia:延髓空洞症syringomyelia:脊髓空洞症Ttactile agnosia:触觉失认[症]Tangier disease:丹吉尔病Tapia syndrome:塔皮亚综合征tarsal tunnel syndrome:跗管综合征temporal epilepsy:颞叶癫痫tension headache:紧张性头痛thalamic syndrome:丘脑综合征thermanesthesia:温度觉缺失thermohyperesthesia:温度觉过敏thermohypesthesia:温度觉减退thigmanesthesia:触觉缺失thoracic outlet syndrome:胸出口综合征tic:抽搐Todd paralysis:托德瘫痪Tolosa Hunt syndrome:托洛萨-亨特综合征,又称“痛性眼肌麻痹” tonic clonic seizure:强直阵挛发作tonic reflex:强直反射tonic seizure:强直发作topoanesthesia:定位觉缺失torsion dysmyotonia:扭转性肌张力障碍transcortical motor aphasia:经皮质运动性失语[症]transcortical sensory aphasia:经皮质感觉性失语[症]transient ischemic attack:短暂性脑缺血发作transient wave:一过性波transverse myelitis:横贯性脊髓炎tremor:震颤triphasic wave:三相波trismus:牙关紧闭Uurinary incontinence:尿失禁Vvegetative state:植物状态vertebro-basilar artery insufficiency:椎基底动脉供血不足vestibulo-ocular reflex:前庭眼反射visual evoked potential, VEP:视觉诱发电位visual-spatial agnosia:视空间觉失认[症]Vogt syndrome:福格特综合征WWallenberg syndrome:瓦伦贝格综合征α-wave:α波β-wave:β波δ-wave:δ波θ-wave:θ波Weber syndrome:韦伯综合征Werdnig-Hoffmann disease:韦德尼希-霍夫曼病,又称“婴儿型脊髓性肌萎缩” Wernicke disease:韦尼克病Wernicke encephalopathy:韦尼克脑病Wernicke syndrome:韦尼克综合征Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome:韦尼克-科尔萨科夫综合征。

第2章心理的神经生理机制一、选择题1.突触小泡(synaptic vesicle)的功能主要是()。

A.控制神经冲动传递的速度B.修复髓鞘C.存贮神经递质D.为神经元活动提供能量【答案】C2.剑刺穿某人头部并造成立即死亡。

在这种情况下剑很有可能刺中了()部位。

A.小脑(cerebellum)B.大脑基底部(basal ganglia)C.延髓(medulla)D.脑桥(pons)【答案】C3.损伤大脑颞叶(temporal lobe)最有可能是使伤者不能从事()职业。

A.音乐家B.演员C.建筑师D.画家【答案】A4.大脑调节内分泌系统主要是通过下述哪两条通路?()A.交感与副交感神经系统B.循环系统和排泄系统C.脑垂体和自主神经系统D.自主神经系统和骨骼神经系统【答案】C5.根据J.LeDoux(1986,1993,1996)的研究表明,以下哪个脑区是情绪过程的重要区?()A.海马回B.杏仁核C.丘脑D.扣带回【答案】B6.位于大脑左半球的布洛卡区受到损伤会发生()。

A.运动性失语症B.接受性失语症C.不能书写D.失读症【答案】A【解析】威尔尼克区受损伤会发生接受性失语症;言语视觉中枢受损伤会发生视觉失语症或失读症。

7.视觉中枢位于()。

A.额叶B.枕叶C.顶叶D.颞叶【答案】B【解析】听觉中枢位于颞叶;视觉中枢位于枕叶;言语运动区位于额叶。

8.有过啃骨头经验的小狗.再看到骨头时,唾液分泌量增加,这属于()。

A.经典条件反射B.操作条件反射C.第一信号系统的反射D.第二信号系统的反射【答案】C【解析】第一信号系统反射是指用具体事物作为条件刺激所建立的各种各样的条件反射;第二信号系统是指用语词作为条件刺激物所建立的各种各样的条件反射。

9.神经冲动在神经元之间的传递是借助()实现的。

A.突触B.轴突C.髓鞘D.树突【答案】A【解析】突触是指在神经元结构中,一个神经元与另一个神经元彼此接触的部位。

突触包括突触前成分、突触间隙和突触后成分。

© Oxford University Press 2004; all rights reservedCerebral Cortex DOI: 10.1093/cercor/bhh042Brain Anatomy in Turner Syndrome: Evidence for Impaired Social and Spatial–Numerical Networks

N. Molko1, A. Cachia2,3, D. Riviere1,2, J.F. Mangin2, M.Bruandet1, D. LeBihan2, L. Cohen1,4 and S. Dehaene1

1INSERM U 562, Service Hospitalier Frédéric Joliot, CEA/DSV,

IFR 49, Orsay, France, 2Unité de Neuro-Activation Fonctionnelle, Service Hospitalier Frédéric Joliot, CEA/DSV, IFR 49, Orsay, France, 3INSERM ERM 0205, IFR 49, Service

Hospitalier Frédéric Joliot, CEA/DSV, IFR 49, Orsay, France and 4Service de Neurologie 1, Hôpital Pitié-Salpétrière, Paris,

France

Analysis of brain structure in Turner syndrome (TS) provides theopportunity to identify the consequences of the loss of one X chromo-some on brain anatomy and to characterize the neural bases under-lying the specific cognitive profile of TS subjects which includesdeficits in spatial–numerical processing and social cognition. Four-teen subjects with TS and fourteen controls were investigated usingvoxel-based analysis of high resolution anatomical and diffusiontensor images and using sulcal morphometry. The analysis ofanatomical images provided evidence for macroscopical changes incortical regions involved in social cognition such as the left superiortemporal sulcus and orbito-frontal cortex and in a region involved inspatial and numerical cognition such as the right intraparietal sulcus.Diffusion tensor images showed a displacement of the grey–whitematter interface of the left and right superior temporal sulcus andrevealed bilateral microstuctural anomalies in the temporal whitematter. The analysis of fiber orientation suggests specific alterationsof fiber tracts connecting posterior to anterior temporal regions. Last,sulcal morphometry confirmed the anomalies of the left and rightsuperior temporal sulci and of the right intraparietal sulcus. Ourresults thus provide converging evidence of regionally specific struc-tural changes in TS that are highly consistent with the hallmarksymptoms associated with TS.

Keywords: developmental dyscalculia, diffusion tensor imaging, MRI, social cognition, sulcal morphometry, Turner syndrome, voxel-based morphometry

IntroductionTurner syndrome (TS) is a genetic condition resulting from apartial or complete absence of one of the two X chromosomesin a phenotypic female (Turner, 1938). TS occurs in approxi-mately one in 2000 liveborn females and affects an estimated3% of all females conceived (Saenger, 1996; Ranke andSaenger, 2001). TS is associated with a well-documented phys-ical phenotype including a short stature, ovarian failure andabnormal pubertal development and a variety of other features(webbed neck, renal dysgenesis, cardiac malformation) (Rankeand Saenger, 2001; Saenger, 1996). In contrast to this well-documented physical phenotype, the consequences of the lossof one X chromosome on brain development and brain func-tion are far less understood. Behavioral studies suggest that thecognitive profile of TS is characterized by a discrepancybetween poor non-verbal abilities and normal to strong verbalability, in the absence of general mental retardation (Templeand Carney, 1996; Ross et al., 2000; Temple and Sherwood,2002). While the severity of the cognitive profile in TS varieswidely, some hallmark symptoms include deficits in visuo-spatial and number processing, working memory and execu-tive function, and social cognition (Ross et al., 2000). Whetherthe psychosocial problems associated with TS result from the

numerous daily life difficulties or reflect a specific impairmentis still unclear. Recent studies showed impairment of affectrecognition and gaze direction monitoring in TS, suggestingthat these social difficulties may originate from a genuinecognitive deficit in reading socially relevant information fromsubtle visual cues (Elgar et al., 2002; Lawrence et al., 2003).All these converging data tentatively evoke the possibleimpairment of multiple neural systems distributed acrossdistinct cerebral regions. However, no brain abnormalities areobvious on visual inspection as expected in such develop-mental disorders where cognitive dysfunctions are more likelyrelated to subtle neuronal and myelination changes. Neverthe-less, previous volumetric MRI studies in TS showed a bilateraldecrease of grey matter volumes in the parietal lobes and inparieto-occipital regions associated with a decreased volume ofthe subcortical gray matter and the hippocampus on both sides(Murphy et al., 1993; Reiss et al., 1993, 1995; Brown et al.,2002). More recently, an increased volume of amygdala and oforbito-frontal cortex have been found in TS using voxel-basedmorphometry (Good et al., 2003). Functional neuroimagingstudies using positron emission tomography (PET) in TS havefound a decrease of glucose metabolism in parietal and occip-ital regions and in the temporal cortex and insula (Clark et al.,1990; Murphy et al., 1997). A putative loss of occipito-parietalconnections has been advanced to explain the parietalhypometabolism (Clark et al., 1990; Murphy et al., 1997).In the present paper, we used high resolution anatomicaland diffusion tensor images, two different MRI techniquesproviding complementary multi-scale information on tissuedensity, microstructural organization and sulcal geometry. Wefirst performed a whole brain analysis using statistical para-metric mapping (SPM) to characterize local tissue changes(Ashburner and Friston, 2000; Good et al., 2001). Sulcalmorphometry in regions found abnormal in the voxel-basedanalysis was then investigated in two candidate regions thatmay underlie the cognitive impairments of TS, the intraparietalsulcus (IPS) and superior temporal sulcus (STS) (Dehaene et al.,1998, 1999; Allison et al., 2000). Using voxel-based morphom-etry, high resolution T1-weighted images have been shown to