(8)The core features of CSCL_ Social situation, collaborative knowledge processes and their design

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:65.18 KB

- 文档页数:8

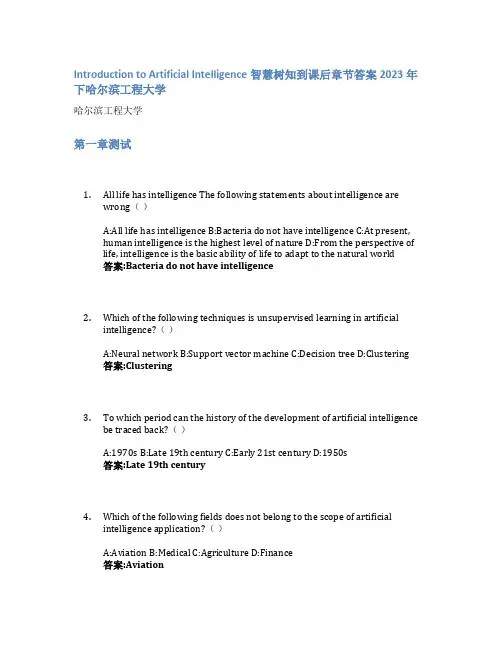

Introduction to Artificial Intelligence智慧树知到课后章节答案2023年下哈尔滨工程大学哈尔滨工程大学第一章测试1.All life has intelligence The following statements about intelligence arewrong()A:All life has intelligence B:Bacteria do not have intelligence C:At present,human intelligence is the highest level of nature D:From the perspective of life, intelligence is the basic ability of life to adapt to the natural world答案:Bacteria do not have intelligence2.Which of the following techniques is unsupervised learning in artificialintelligence?()A:Neural network B:Support vector machine C:Decision tree D:Clustering答案:Clustering3.To which period can the history of the development of artificial intelligencebe traced back?()A:1970s B:Late 19th century C:Early 21st century D:1950s答案:Late 19th century4.Which of the following fields does not belong to the scope of artificialintelligence application?()A:Aviation B:Medical C:Agriculture D:Finance答案:Aviation5.The first artificial neuron model in human history was the MP model,proposed by Hebb.()A:对 B:错答案:错6.Big data will bring considerable value in government public services, medicalservices, retail, manufacturing, and personal location services. ()A:错 B:对答案:对第二章测试1.Which of the following options is not human reason:()A:Value rationality B:Intellectual rationality C:Methodological rationalityD:Cognitive rationality答案:Intellectual rationality2.When did life begin? ()A:Between 10 billion and 4.5 billion years B:Between 13.8 billion years and10 billion years C:Between 4.5 billion and 3.5 billion years D:Before 13.8billion years答案:Between 4.5 billion and 3.5 billion years3.Which of the following statements is true regarding the philosophicalthinking about artificial intelligence?()A:Philosophical thinking has hindered the progress of artificial intelligence.B:Philosophical thinking has contributed to the development of artificialintelligence. C:Philosophical thinking is only concerned with the ethicalimplications of artificial intelligence. D:Philosophical thinking has no impact on the development of artificial intelligence.答案:Philosophical thinking has contributed to the development ofartificial intelligence.4.What is the rational nature of artificial intelligence?()A:The ability to communicate effectively with humans. B:The ability to feel emotions and express creativity. C:The ability to reason and make logicaldeductions. D:The ability to learn from experience and adapt to newsituations.答案:The ability to reason and make logical deductions.5.Which of the following statements is true regarding the rational nature ofartificial intelligence?()A:The rational nature of artificial intelligence includes emotional intelligence.B:The rational nature of artificial intelligence is limited to logical reasoning.C:The rational nature of artificial intelligence is not important for itsdevelopment. D:The rational nature of artificial intelligence is only concerned with mathematical calculations.答案:The rational nature of artificial intelligence is limited to logicalreasoning.6.Connectionism believes that the basic element of human thinking is symbol,not neuron; Human's cognitive process is a self-organization process ofsymbol operation rather than weight. ()A:对 B:错答案:错第三章测试1.The brain of all organisms can be divided into three primitive parts:forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain. Specifically, the human brain is composed of brainstem, cerebellum and brain (forebrain). ()A:错 B:对答案:对2.The neural connections in the brain are chaotic. ()A:对 B:错答案:错3.The following statement about the left and right half of the brain and itsfunction is wrong ().A:When dictating questions, the left brain is responsible for logical thinking,and the right brain is responsible for language description. B:The left brain is like a scientist, good at abstract thinking and complex calculation, but lacking rich emotion. C:The right brain is like an artist, creative in music, art andother artistic activities, and rich in emotion D:The left and right hemispheres of the brain have the same shape, but their functions are quite different. They are generally called the left brain and the right brain respectively.答案:When dictating questions, the left brain is responsible for logicalthinking, and the right brain is responsible for language description.4.What is the basic unit of the nervous system?()A:Neuron B:Gene C:Atom D:Molecule答案:Neuron5.What is the role of the prefrontal cortex in cognitive functions?()A:It is responsible for sensory processing. B:It is involved in emotionalprocessing. C:It is responsible for higher-level cognitive functions. D:It isinvolved in motor control.答案:It is responsible for higher-level cognitive functions.6.What is the definition of intelligence?()A:The ability to communicate effectively. B:The ability to perform physicaltasks. C:The ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills. D:The abilityto regulate emotions.答案:The ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills.第四章测试1.The forward propagation neural network is based on the mathematicalmodel of neurons and is composed of neurons connected together by specific connection methods. Different artificial neural networks generally havedifferent structures, but the basis is still the mathematical model of neurons.()A:对 B:错答案:对2.In the perceptron, the weights are adjusted by learning so that the networkcan get the desired output for any input. ()A:对 B:错答案:对3.Convolution neural network is a feedforward neural network, which hasmany advantages and has excellent performance for large image processing.Among the following options, the advantage of convolution neural network is().A:Implicit learning avoids explicit feature extraction B:Weight sharingC:Translation invariance D:Strong robustness答案:Implicit learning avoids explicit feature extraction;Weightsharing;Strong robustness4.In a feedforward neural network, information travels in which direction?()A:Forward B:Both A and B C:None of the above D:Backward答案:Forward5.What is the main feature of a convolutional neural network?()A:They are used for speech recognition. B:They are used for natural languageprocessing. C:They are used for reinforcement learning. D:They are used forimage recognition.答案:They are used for image recognition.6.Which of the following is a characteristic of deep neural networks?()A:They require less training data than shallow neural networks. B:They havefewer hidden layers than shallow neural networks. C:They have loweraccuracy than shallow neural networks. D:They are more computationallyexpensive than shallow neural networks.答案:They are more computationally expensive than shallow neuralnetworks.第五章测试1.Machine learning refers to how the computer simulates or realizes humanlearning behavior to obtain new knowledge or skills, and reorganizes the existing knowledge structure to continuously improve its own performance.()A:对 B:错答案:对2.The best decision sequence of Markov decision process is solved by Bellmanequation, and the value of each state is determined not only by the current state but also by the later state.()A:对 B:错答案:对3.Alex Net's contributions to this work include: ().A:Use GPUNVIDIAGTX580 to reduce the training time B:Use the modified linear unit (Re LU) as the nonlinear activation function C:Cover the larger pool to avoid the average effect of average pool D:Use the Dropouttechnology to selectively ignore the single neuron during training to avoid over-fitting the model答案:Use GPUNVIDIAGTX580 to reduce the training time;Use themodified linear unit (Re LU) as the nonlinear activation function;Cover the larger pool to avoid the average effect of average pool;Use theDropout technology to selectively ignore the single neuron duringtraining to avoid over-fitting the model4.In supervised learning, what is the role of the labeled data?()A:To evaluate the model B:To train the model C:None of the above D:To test the model答案:To train the model5.In reinforcement learning, what is the goal of the agent?()A:To identify patterns in input data B:To minimize the error between thepredicted and actual output C:To maximize the reward obtained from theenvironment D:To classify input data into different categories答案:To maximize the reward obtained from the environment6.Which of the following is a characteristic of transfer learning?()A:It can only be used for supervised learning tasks B:It requires a largeamount of labeled data C:It involves transferring knowledge from onedomain to another D:It is only applicable to small-scale problems答案:It involves transferring knowledge from one domain to another第六章测试1.Image segmentation is the technology and process of dividing an image intoseveral specific regions with unique properties and proposing objects ofinterest. In the following statement about image segmentation algorithm, the error is ().A:Region growth method is to complete the segmentation by calculating the mean vector of the offset. B:Watershed algorithm, MeanShift segmentation,region growth and Ostu threshold segmentation can complete imagesegmentation. C:Watershed algorithm is often used to segment the objectsconnected in the image. D:Otsu threshold segmentation, also known as themaximum between-class difference method, realizes the automatic selection of global threshold T by counting the histogram characteristics of the entire image答案:Region growth method is to complete the segmentation bycalculating the mean vector of the offset.2.Camera calibration is a key step when using machine vision to measureobjects. Its calibration accuracy will directly affect the measurementaccuracy. Among them, camera calibration generally involves the mutualconversion of object point coordinates in several coordinate systems. So,what coordinate systems do you mean by "several coordinate systems" here?()A:Image coordinate system B:Image plane coordinate system C:Cameracoordinate system D:World coordinate system答案:Image coordinate system;Image plane coordinate system;Camera coordinate system;World coordinate systemmonly used digital image filtering methods:().A:bilateral filtering B:median filter C:mean filtering D:Gaussian filter答案:bilateral filtering;median filter;mean filtering;Gaussian filter4.Application areas of digital image processing include:()A:Industrial inspection B:Biomedical Science C:Scenario simulation D:remote sensing答案:Industrial inspection;Biomedical Science5.Image segmentation is the technology and process of dividing an image intoseveral specific regions with unique properties and proposing objects ofinterest. In the following statement about image segmentation algorithm, the error is ( ).A:Otsu threshold segmentation, also known as the maximum between-class difference method, realizes the automatic selection of global threshold T by counting the histogram characteristics of the entire imageB: Watershed algorithm is often used to segment the objects connected in the image. C:Region growth method is to complete the segmentation bycalculating the mean vector of the offset. D:Watershed algorithm, MeanShift segmentation, region growth and Ostu threshold segmentation can complete image segmentation.答案:Region growth method is to complete the segmentation bycalculating the mean vector of the offset.第七章测试1.Blind search can be applied to many different search problems, but it has notbeen widely used due to its low efficiency.()A:错 B:对答案:对2.Which of the following search methods uses a FIFO queue ().A:width-first search B:random search C:depth-first search D:generation-test method答案:width-first search3.What causes the complexity of the semantic network ().A:There is no recognized formal representation system B:The quantifiernetwork is inadequate C:The means of knowledge representation are diverse D:The relationship between nodes can be linear, nonlinear, or even recursive 答案:The means of knowledge representation are diverse;Therelationship between nodes can be linear, nonlinear, or even recursive4.In the knowledge graph taking Leonardo da Vinci as an example, the entity ofthe character represents a node, and the relationship between the artist and the character represents an edge. Search is the process of finding the actionsequence of an intelligent system.()A:对 B:错答案:对5.Which of the following statements about common methods of path search iswrong()A:When using the artificial potential field method, when there are someobstacles in any distance around the target point, it is easy to cause the path to be unreachable B:The A* algorithm occupies too much memory during the search, the search efficiency is reduced, and the optimal result cannot beguaranteed C:The artificial potential field method can quickly search for acollision-free path with strong flexibility D:A* algorithm can solve theshortest path of state space search答案:When using the artificial potential field method, when there aresome obstacles in any distance around the target point, it is easy tocause the path to be unreachable第八章测试1.The language, spoken language, written language, sign language and Pythonlanguage of human communication are all natural languages.()A:对 B:错答案:错2.The following statement about machine translation is wrong ().A:The analysis stage of machine translation is mainly lexical analysis andpragmatic analysis B:The essence of machine translation is the discovery and application of bilingual translation laws. C:The four stages of machinetranslation are retrieval, analysis, conversion and generation. D:At present,natural language machine translation generally takes sentences as thetranslation unit.答案:The analysis stage of machine translation is mainly lexical analysis and pragmatic analysis3.Which of the following fields does machine translation belong to? ()A:Expert system B:Machine learning C:Human sensory simulation D:Natural language system答案:Natural language system4.The following statements about language are wrong: ()。

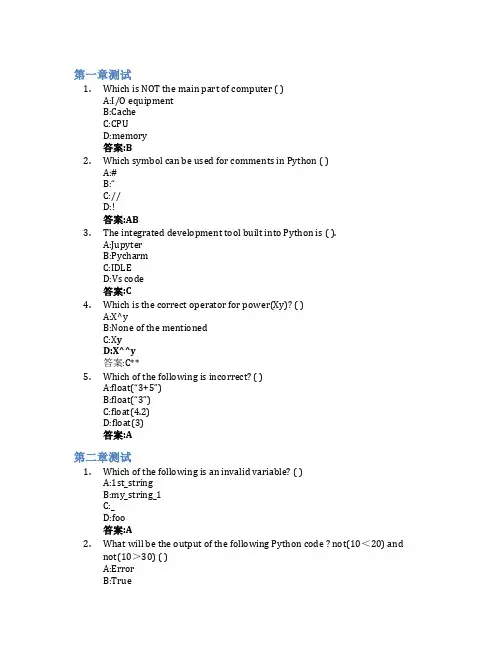

第一章测试1.Which is NOT the main part of computer ( )A:I/O equipmentB:CacheC:CPUD:memory答案:B2.Which symbol can be used for comments in Python ( )A:#B:“C://D:!答案:AB3.The integrated development tool built into Python is ( ).A:JupyterB:PycharmC:IDLED:Vs code答案:C4.Which is the correct operator for power(Xy)? ( )A:X^yB:None of the mentionedC:X yD:X^^y答案:C**5.Which of the following is incorrect? ( )A:float(“3+5”)B:float(“3”)C:float(4.2)D:float(3)答案:A第二章测试1.Which of the following is an invalid variable? ( )A:1st_stringB:my_string_1C:_D:foo答案:A2.What will be the output of the following Python code ? not(10<20) andnot(10>30) ( )A:ErrorB:TrueD:No output答案:C3.Which one will return error when accessing the list ‘l’ with 10 elements. ( )A:l[0]B:l[-10]C:l[10]D:l[-1]答案:C4.What will be the output of the following Python code?lst=[3,4,6,1,2]lst[1:2]=[7,8]print(lst) ( )A:Syntax errorB:[3,4,6,7,8]C:[3, 7, 8, 6, 1, 2]D:[3,[7,8],6,1,2]答案:C5.Which of the following operations will rightly modify the value of theelement? ( )答案:D6.The following program input data: 95, the output result is? ( )A:none of the mentionedB:Please enter your score: 95Your ability exceeds 85% of people!C:Please enter your score: 95Awesome!D:Please enter your score: 95Awesome!Your ability exceeds 85% of people!答案:D第三章测试1.Which one description of condition in the followings is correct? ( )A:The condition 24<=28<25 is legal, and the output is FalseB:The condition 35<=45<75 is legal, and the output is FalseC:The condition 24<=28<25 is illegalD:The condition 24<=28<25 is legal, and the output is True答案:A2.The output of the following program is? ( )A:PythonB:NoneC:pythonD:t答案:B3. for var in ___: ( )A:range(0,10)B:13.5C:[1,2,3]答案:B4.After the following program is executed, the value of s is?( )A:19B:47C:46D:9答案:D5.Which is the output of the following code?a = 30b = 1if a >=10:a = 20elif a>=20:a = 30elif a>=30:b = aelse:b = 0print(“a=”,a,“b=”,b) ()A:a=20, b=20B:a=30, b=30C:a=20, b=1D:a=30, b=1答案:C第四章测试1.Which keyword is used to define a function in Python? ( )A:funB:defineC:defD:function答案:C2.What will be the output of the following Python code? ( )A: x is 50Changed local x to 2x is now 50B:x is 50Changed local x to 2x is now 100C:None of the mentionedD:x is 50Changed local x to 2x is now 2答案:A3.Which are the advantages of functions in Python? ( )A:Improving clarity of the codeB:Reducing duplication of codeC:Easier to manage the codeD:Decomposing complex problems into simpler pieces答案:ABCD4.How does the variable length argument specified in the function heading? ( )A:one star followed by a valid identifierB:two stars followed by a valid identifierC:one underscore followed by a valid identifierD:two underscores followed by a valid identifier答案:A5.What will be the output of the following Python code? list(map((lambdax:x2), filter((lambda x:x%2==0), range(10)))) ( )A:[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]C:[0, 4, 16, 36, 64]D:No output答案:C**第五章测试1.Which of the following statements cannot create a demo.txt file? ( )A:f = open(“demo.txt”, “w”)B:f = open(“demo.txt”, “r”)C:f = open(“demo.txt”, “x”)D:f = open(“demo.txt”, “a”)答案:B2.After executing the following procedure, what content will be saved in thefile?file=open(‘test.txt’, ‘wt+’)file.write(‘helloSCUT’)file.close()file=open(‘test.txt’, ‘at+’)file.write(‘hello world’)file.close() ( )A:hello SCUThello worldB:hello SCUT hello worldC:hello SCUT worldD:hello world答案:A3.Which function is not the way Python reads files. ( )A:readlines()B:readline()C:read()D:readtext()答案:D4.How to rename a file in Python? ( )A:os.rename(fp, new_name)B:os.set_name(existing_name, new_name)C:os.rename(existing_name, new_name)D: = ‘new_name.txt’答案:C5.What is the usage of tell() function in Python? ( )A:tells you the current position within the fileB:tells you the end position within the fileC:none of the mentionedD:tells you the file is opened or not答案:A第六章测试1.What will be the output of the following Python code? ( )A:Reports error as one argument is required while creating the objectB:Runs normally, doesn’t display anythingC:Reports error as display function requires additional argumentD:Displays 0, which is the automatic default value答案:A2.What will be the output of the following Python code? ( )A:ErrorB:‘Old’C:Nothing is printedD:‘New’答案:B3.What will be the output of the following Python code? ( )A:mainB:Exception is thrownC:DemoD:test答案:A4.Which one of the followings is not correct about Class hierarchy? ( )A:Subclass can not add more behavior/methodsB:Subclass can override the methods inherited from superclassC:Subclass can have methods with same name as superclassD:Subclass can inherit all attributes from superclass答案:A5.What will be the output of the following Python code? ( )A:Error because class B inherits A but variable x isn’t inheritedB:0 1C:0 0D:Error, the syntax of the invoking method is wrong答案:B第七章测试1.Numpy is a third party package for ____ in Python? ( )A:Lambda functionB:ArrayC:FunctionD:Type casting答案:B2.How to convert a Numpy array to a list in Python? ( )A:array.listB:list.arrayC:list(array)D:list.append(array)答案:C3.Which keyword is used to access the Numpy package in Python? ( )A:loadB:importC:fromD:fetch答案:B4.Which one is correct syntax for the ‘reshape()’ function in Numpy? ( )A:array.reshape(shape)B:reshape(shape,array)C:reshape(shape)D:reshape(array,shape)答案:D5.What will be the output for the following code? import numpy as np a =np.array([1, 2, 3], dtype = complex) print(a) ( )A:[[ 1.+0.j, 2.+0.j, 3.+0.j]]B:[ 1.+0.j]C:ErrorD:[ 1.+0.j, 2.+0.j, 3.+0.j]答案:D第八章测试1.Which one isn’t the method of Image.transpose? ( )A:TRANSPOSEB:FLIP_LEFT_RIGHTC:ROTATE_90D:STRETCH答案:D2.Which one isn’t the method of ImageFilter? ( )A:ImageFilter.DETAILB:ImageFilter.BLURC:ImageFilter.EDGE_ENHANCED:ImageFilter.SHARP答案:D3.Which one is attribute of image? ( )A:modeB:sizeC:colorD:format答案:ABD4.Which operation can be used to set the picture to a given size? ( )A:resize()B:crop()C:thumbnail()D:transpose()答案:A5.What is the effect of ImageFilter. CONTOUR? ( )A:Blur the pictureB:Sharp the imageC:Smooth the pictureD:Extract lines in the picture 答案:D。

语言学教程(第四版)练习-第4章Chapter Four From Word to TextI. Mark the choice that best completes the statement.1.Which of the following term does NOT mean the same as the relation of substitutability ?A. Associative relationB. Paradigmatic relationC. Vertical relationD. Horizontal relation2. Clauses can be used as subordinate constituents and the three basic types of subordinate clauses are complement clauses, adjuncts clauses and _______.A. relative clausesB. adverbial clausesC. coordinate clausesD. subordinate clauses3. Names of the syntactic functions are expressed in all the following terms EXCEPT ______.A. subjects and objectsB. objects and predicatorsC. modifiers and complementsD. endocentric and exocentric4. In English, case is a special form of the noun which frequently corresponds toa combination of perception and noun and it is realized in all the following channels EXCEPT _______.A. inflectionB. following a prepositionC. word orderD. vertical relation5. In English, theme and rheme are often expressed by _____ and ____.A. subject; objectB. subject; predicateC. predicate; objectD. object; predicate6. Phrase structure rules have _____ properties.A. recursiveB. grammaticalC. socialD. functional7. Which of the following is NOT among the three basic ways to classify languages in the world ?A. Word orderB. Genetic classificationC. Areal classificationD. Social classification8. The head of the phrase the city Rome is ______.A. the cityB. RomeC. cityD. the city Rome9. The phrase on the shelf belongs to ______ construction.A. endocentricB. exocentricC. subordinateD. coordinate10. The sentence They were wanted to remain quiet and not to expose themselves isa _____ sentence.A. simpleB. coordinateC. compoundD. complexII. Mark the following statements with “T” if they are true or “F” if they are false.1.The relation of co-occurrence partly belong to syntagmatic relations, partlyto paradigmatic relations.2.One property coordination reveals is that there is a limit on the number ofcoordinated categories that can appear prior to the conjunction.3.According to Standard Theory of Chomsky, deep structure contain all theinformation necessary for the semantic interpretation of sentences.4.In English, the object is recognized by tracing its relation to word order andby inflections of pronouns.5.Classes and functions determine each other, but not in any one-to-onerelation.ually noun phrases, verb phrases and adverbial phrases belong toendocentric types of constriction.7.In English the subject usually precedes the verb and the direct object usuallyfollows the verb.8.In the exocentric construction John kicked the ball, neither constituent standsfor the verb-object sequence.9. A noun phrase must contain a noun, but other elements are optional.10.In a coordinate sentence, two (or more) S constituents occur as daughters andco-heads of a higher S.III. Fill in each of the following blanks with an appropriate word. The first letter of the word is already given.1.The subordinate constituents are words which modify the Heads andconsequently, they can be called m____________.2.John believes (that the airplane was invented by an Irishman). The part in thebracket is a c_________ clause.3.In order to account for the case of the subject in passive voice, we haveanother two terms, p____________ and n__________.4.There is a tendency to make a distinction between phrase and w_______,which is an extension of word of a particular class by way of modification with its main features of the class unchanged.5.Recursiveness, together with o_______, is generally regarded as the core ofcreativity of language.6.Traditionally, p_________ is seen as part of a structural hierarchy, positionedbetween clause and word.7.The case category is used in the analysis of word classes to identity thes______ relationship between words in a sentence.8.Clause can be classifies into FINITE and NON-FINITE clauses, the latterincluding the traditional infinitive phrase, p__________, and gerundial phrase.9.Gender displays such contrasts as masculine: feminine: n_______.10.English gender contrast can only be observed in g__________ and a smallnumber of l__________ and they are mainly of the natural gender type.IV. Explain the following concepts or theories.1.Syntax2.IC analysis3.Relation of co-occurrence4.Category5.RecursivenessVI. Answer the following question.1.What are endocentric construction and exocentric construction?2.What are the basic functional terms in syntax?VII. Essay question.1.Explain an comment on the following sentence a and b.a.John is easy to please.b.John is eager to please.ment on the statement, “Linguistic structure is hiearchical”I. Mark the following statements with “T” if they are true or “F” if they are false.1.The syntactic rules of any language are finite in number, but they are capableof yielding an infinite number of sentences.2.Although, a single word can also be uttered as a sentence, normally asentence consists of at least a subject, its predicate and an object.\3.The sentences are linearly structured, so they are composed of sequence ofwords arranged in a simple linear order.4. a.John his upon an idea.b.An idea hit upon John.In the above sentences, the subject and object constituent by the sentences switch their position. Although sentence b is absurd, it is still grammatical, because John and an idea are of the same phrasal category.5.Though they are of a small number, the combinational rules are powerfulenough to yield all the possible sentences and rule out the impossible ones. 6.In a sentence like Mary likes flowers, both Mary and flowers are not onlyNouns, but also Noun Phrases.7.The recursive property can basically be discussed in a category-basedgrammar, but not in a word-based grammar.8.An XP must contain an X which is called the phrasal head.9.In the phrase this very tall girl, tall girl is an obligatory element and the headof the phrase.10.a. The man beat the child. b. The child was beaten by the man.In the above sentences, the movement of the child from its original place to a new place is a WH- movement.11.Tense and aspect, the two important categories of the verb, nowadays areviewed as separate notions in grammar.12.The structuralists regard linguistic units as isolated bits in a structure (orsystem).13.IC analysis can help us to see the internal structure of a sentence clearly andit can also distinguish the ambiguity of a sentence.14.Structural linguists hold that a sentence does only have a linear structure, butit has a hierarchical structure, made up of layers of word groups.15.In Saussure’s view, the linguist cannot attempt to explain individual signs in apiecemeal fashion. Instead he must try to find the value of a sign from its relation to others, or rather, its position in the system.16.The theme-rheme order is the usual one in unemotional narration, which is asubjective order.17.What is new in Halliday is that he has tried to relate the functions oflanguage to its structure.18.Sentence is a basic unit of structure in functional grammar.19.The interpersonal function of language refers to the idea held by Hallidaythat language serves ot establish and maintain social relations.20.Finite is a function in the clause as a representation, both the representationof outer experience and inner experience.21.The relations of co-occurrence partly belong to syntagmatic relations, partlyto paradigmatic relations.22.According to Chomsky, grammar is a mechanism that should be able togenerate all and only the grammatical sentences of a language.23.In English, the subject of a sentence is said to be the doer of an action, whilethe object is the person or thing acted upon by the doer. Therefore, the subject is always an agent and the patient is always the object.24.In English, the object is recognized by tracing its relation to word order andby inflections of pronouns.25.Classes and functions determine each other, but not in any one-to-onerelation.26.The syntactic rules of a language are finite in number, and there are a limitednumber of sentences which can be produced.27.Structuralism views language as both linearly and hierarchically structured.28.Phrase structure rules provide explanations on how syntactic categories areformed and sentences generated.29.UG is a system of linguistic knowledge and a human species-specific giftwhich exists in the mind of a normal human being.30.Tense and aspect are two important categories of the verb, and they wereseparated in traditional grammar.II. Fill in each of the following blanks with (an) appropriate word(s).1.As is required by the ______, a noun phrase must have case and case isassigned by verb, or preposition to the _________ position or by auxiliary to the ________ position.2.Adjacency condition states that a case _________ and a case _______ shouldstay adjacent to each other.3.The general movement rule accounting for the syntactic behavior of anyconstituent movement is called __________.4.The phrase structure rules, with the insertion of the lexicon, generatesentences at the level of _________.5.The application of syntactic movement rules transforms a sentence from thelevel of ________ to that of ______.6.In English there are two major types of movement, one involving the_____.A.(1)B.(2)C. both (1) and (2)D. neitherC.Imitation accounts for language acquisition.D.Phonological information must form part of syntactic movement.8.The symbol N indicates a/an ________.A.lexical categoryB.phrasal categoryC.intermediate categoryD. lexical insertion rule9.Of the following combination possibilities, ______ can NOT be generated from the following rule: NP→(Det)(Adj)N(PP)(S).A. NP→→→→Det Adj N PPS.10.An advantage of X-bar syntax over phrase structure syntax is that X-bar.A.avoid a ploliferation of redundant intermediate categories.B.allows us to identify indefinitely long embedded sentences.C. allows as to postulate categories other than lexical and phrasal.D. forces us to conclude that the ambiguity of phrases like the English Kingis lexical rather than structural.11. Which set of rules generates the following tree structures?A. S→NP VPB. NP→VPNP→N PP NP→NP NP PPVP→V NP VP→V NP PPPP →P NP PP →P NPNP→N NP →NC.S VP VP D, S NP VPNP→(NP/PP) NP →NP (NP /PP)VP →V NP VP →V NPPP →P NP PP →P NPNP→N NP →N12.a.It seems they are quite fit for the job.b. They seem quite fit for the job.Sentence b is a result of ______ movement.A.NPB.WHC.AUX.D. None13. The head of the phrase underneath the open window is _______.A.underneathB.theC.openD.window14.The following statements are in accordance with Hallliday’s opinion on language EXCEPT _______.he use of language involves a network of systems of choices.B. Language is never used as a mere mirror of reflected thought.nguage is a system of abstract forms and signs.nguage functions as a piece of human behavior.15.Chomsky is more concerned with ____ relations in his approach to syntax.16.______ is a type of control over the form of some words by other words in Certain syntactic constructions and in terms of certain category.A.ConcordernmentC. BindingD. Co-command17. Clauses can be used as subordinate constituents and the three basic types of subordinate clauses are complement clauses, adjunct clauses and _____.A.relative clausesB.adverbial clausesC.coordinate clausesD.subordinate clausess of the syntactic functions are expressed in all the following terms EXCEPT_____.A.subjects and objectsB.objects and predicatorsC.modifiers and complementsD. endocentric and exocentric19.In English, case is a special form of the noun which frequently corresponds toa combination of preposition and noun and it is realized in all the following channels EXCEPT ______.A.inflectionB.following a prepositionC.word orderD.vertical relation20. Clauses can be classified into finite and non-finite clauses, _____ including the traditional infinitive phrases, participial phrase and gerundial phrase.A. the formerB. the latterC.bothD. neither21.It is the _______ on case assignment that states that a case assignor and a case recipient should stay adjacent to each other.A. Case ConditionB.Adjacent ConditionC.Parameter ConditionD.Adjacent Parameter.22.Predication analysis is a way to analyze _______ meaning.A. phonemeB. wordC. phrase…d. sentence23.Which of the following italic parts is NOT an idiom?A. How to you do?B. How did you do ?C. He went to it hammer and tongs.D. They kept tabs on the Russian spy.24.When we say that we can change the second word in the sentence she is singing in the room with another word or phrase, we are talking about ______.A. governmentB. linear relationsC. syntactic relationsD. paradigmatic relations25.IN the phrase structure rule S→NP VP, the arrow can be read as ______.A. hasB. generatesC. consists ofD. is equal toIV. Answer the following questions as comprehensively as possible, giving examples if necessary.1.The following two sentences are ambiguous. Show the two readings of eachby drawing its respective tree diagrams.(1)The ball man and woman left(2) Visiting professor can be interestinge an example to show what a tree diagram is (as it is used inTransformational-Generative Grammar).e an example to show what IC analysis is.4.What are the three general functions of language according to Halliday?5.What distinguishes the structural approach to syntax from the traditionalone?6.Some grammar books say there are three basic tenses in English-the present,the past and the future; others say there are only two basic tenses –the present and the past. Explain what tense is and whether it is justifiable to say there is a future tense in English.。

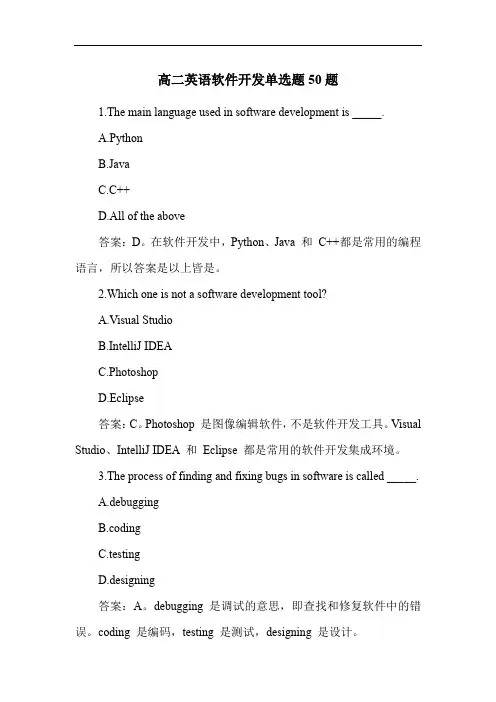

高二英语软件开发单选题50题1.The main language used in software development is _____.A.PythonB.JavaC.C++D.All of the above答案:D。

在软件开发中,Python、Java 和C++都是常用的编程语言,所以答案是以上皆是。

2.Which one is not a software development tool?A.Visual StudioB.IntelliJ IDEAC.PhotoshopD.Eclipse答案:C。

Photoshop 是图像编辑软件,不是软件开发工具。

Visual Studio、IntelliJ IDEA 和Eclipse 都是常用的软件开发集成环境。

3.The process of finding and fixing bugs in software is called _____.A.debuggingB.codingC.testingD.designing答案:A。

debugging 是调试的意思,即查找和修复软件中的错误。

coding 是编码,testing 是测试,designing 是设计。

4.A set of instructions that a computer follows is called a _____.A.programB.algorithmC.data structureD.variable答案:A。

program 是程序,即一组计算机遵循的指令。

algorithm 是算法,data structure 是数据结构,variable 是变量。

5.Which programming paradigm emphasizes on objects and classes?A.Procedural programmingB.Functional programmingC.Object-oriented programmingD.Logic programming答案:C。

主题英语_中南大学中国大学mooc课后章节答案期末考试题库2023年1.Which one of the following does NOT belong to seven deadly sins?答案:murder2.English thinking tends to be ______________ compared with Chinese thinking.答案:objective3.Which one of the following sentences uses inanimate subject?答案:Reading makes a full man.4.Which date is the World Book Day?答案:April 235.What is “the Commercial Press”?答案:商务印书馆6.What is “presupposition”?答案:预设7.“Privileged” means _______.答案:have advantages8.Translate the following into English: 尽管很多人担心中国传统文化会受到威胁,其他人却认为由于学习了英语,中国传统文化不但不会消亡,反而会在某种程度上被推向全世界。

答案:When Chinese learning English, Chinese traditional culture will not go extinct, but rather, be spread all over the world to some degree.9.Which one is NOT the characteristic of the extreme sport?答案:It is not interesting.10.Effective parallelism will enable you to combine in a single, well-orderedsentence related ideas that you might have expressed in separate sentences, thereby .答案:increasing coherence11.According to Helen Keller, life is either_______ or nothing.答案:a daring adventure12.Your voice, my friend, wanders in my heart, like the muffled sound of the seaamong these pines.答案:listening13. A man in an fishing family scored the same on the researcher'squestionnaire as his twin, whose father by adoption was the head of thepolice force.答案:raised, uneducated14.Learning to listen _________ — not just _________ —doesn’t come easily to him.答案:patiently, passively15.What is “bilingual education”?答案:双语教育16.Which of the following is the definition of “love” according to the video?答案:It is a variety of different feelings, states, and attitudes that ranges from interpersonal affection to pleasure. It can refer to an emotion of a strong attraction and personal attachment.17.Which of the following sentence doesn’t contain a passive voice?答案:There is some advice for the passive voice.18.Which of the following translation is right?答案:affix 词缀19.Which of the following is not the meaning of “budget” ?答案:木桶20.The thesis appears in the _________ paragraph, and the specific support for thethesis appears in the paragraphs that follow.答案:introductory21.Which of the following is correct as a sentence?答案:I drove slowly past the old brick house, the place where I grew up.22.If you knock on the tableware with chopsticks, it is seen as a sign of .答案:begging23.The middle school is ________ to a normal college.答案:attached24.As time___________, my memory seems to get worse.答案:goes by25.There is some _________whether he will come to this activity tomorrow.答案:doubt26.What is the main idea of Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan?答案:We should cherish our earth.27.University is a kind of _________.答案:academic organization28.One of the qualities that most people admire in others is the willingness to_______ one’s mistakes.答案:admit29.What subject can replace "I" when talking about one's own readingexperience?答案:The pictures or data in the bookThe authorThe hero or heroine in the storyThe components of the book30.Why did Cherry suggest you to give some basic information of the book youread?答案:to attract the audience's attentionto help the audience presume what to hear31.Which of the following statements are the benefits of a commonly usedlanguage?答案:Owing to the communication in one commonly used language, traditions and customs of different cultures are transmitted.A bridge language makes it possible to communicate with people fromdifferent cultures.Intercultural communication activities, such as, international business,academic conferences, and political visits, etc. are helpful to spread onecertain culture to other places.32.The sentence patterns introduced to describe the special event in one's lifeinclude ________.答案:Then came the big/great/important ...+n.+定语(从句).When + 分词短语,....NP+of doing sth. +paid off.It is time+定语(从句).33.Which of the following words has the prefix "e-" meaning "out"?答案:evokeemergeeliminate34.Which of the following is true?答案:When “dreaded” is an adjective, it can only be used as a modifier in front of a noun, meaning "terrible, annoying, inconvenient, undesirable".The word "eliminate" sounds more positive.后缀-ful意思是full of。

第29卷第4期2017年8月六盘水师范学院学报Journal of Liupanshui Normal UniversityVol.29NO.4Aug.2017红军长征胜利虽已过去80余年,但长征精神却是我们取之不尽用之不竭的伟大精神力量。

在革命时期,长征不但扭转了党和红军在当时的困境局面,同时也推动着中国革命逐步走向胜利。

现在,长征精神依然是值得我们学习的重要内容,对长征精神的学习有利于人们认识和了解长征精神,使长征精神融入我们的意识形态,主导我们的思想行为;有利于对长征精神的传承,弘扬民族精神和时代精神;将长征精神融入社会主义核心价值观教育,引导人们认同并积极践行社会主义核心价值观具有重要的现实意义。

一、长征精神的基本含义“1934年10月,中共中央和红一方面军被迫撤离中央革命根据地,开始了艰苦的长征和北上抗日的战略转移。

”“英雄的红军在毛泽东等同志的领导和指挥下,以非凡的智慧和勇气,运用机动灵活的战略技术,四渡赤水河,巧渡金沙江,强渡大渡河,……纵横十余省,长驱二万五千里,终于取得了长征的胜利。

”(江泽民,1996)长征是中国共产党在革命时期面临严重危机时,认真分析局势所做出的重要军事战略转移,它不仅是对共产党人的一次严峻考验,也是中国共产党运用马克思主义理论去解决当时的政治问题和军事问题,是共产党不断走向成熟的标志。

胡锦涛同志指出:“长征精神是中国共产党人和人民军队革命风范的生动反映,是中华民族自强不息的民族品格的集中展示,是以爱国主义为核心的民族精神的最高体现。

”(胡锦涛,2006)一个国家有什么样的民族品格,就体现着这个国家的人民有着怎样的品格。

正是由于红军在长征中体现出来的实事求是、统筹兼顾、不畏艰险和英勇乐观等崇高品格,让党和人民更加的团结,不畏艰险地集中一切力量解决当时的主要矛盾,才推动着整个革命的胜利。

伟大的长征精神体现着我们整个民族的先进品格,这样的民族品格不仅赋予了中华民族精神力量,而且培育了中华儿女牢固的爱国情结,始终把中华儿女坚强地团结在一起。

通用学术英语写作_中国政法大学中国大学mooc课后章节答案期末考试题库2023年1. 5.First of all, watching TV has the value of sheer relaxation. Watchingtelevision can be soothing and restful after an eight-hour day of pressure,challenges, or concentration. After working hard all day, people look forward to a new episode of a favorite show or yet another showing of Casablanca or Sleepless in Seattle. 该段的衔接手段主要是_____与______。

参考答案:近义词(话题近义词 TV-television-show-showing; 主题近义词relaxation-soothing-restful)、上下义词(TV--Casablanca or Sleepless in Seattle)2. 2.We hear a lot about the negative effects of television on the viewer.Obviously, television can be harmful if it is watched constantly to theexclusion of other activities. It would be just as harmful to listen to DCs allthe time or to eat constantly. However, when television is watched inmoderation, it is extremely valuable, as it provides relaxation, entertainment, and education. 该段两大内容是________与_________。

第一章测试1.我不需要做研究,所以我不需要学习学术英语写作。

A:错B:对答案:A2.做旅游攻略的过程,就是一个简单的research过程。

A:错B:对答案:B3.et al就是 and others的意思。

A:对B:错答案:A4.下面哪些选项是学术英语写作的原因?A:To discuss a subject of common interest and give the writer’s view;B:To answer a question the writer has been given or chosen;C:To synthesize research done by others on a topic.D:To report on a piece of research the writer has conducted;答案:ABCD5.学术英语写作中的一般文本特征包括:A:sentenceB:headingC:sub-titleD:titleE:phraseF:paragraph答案:ABCDEF第二章测试1.在细化主题时,需要考虑你的写作目的是什么以及预期读者是谁。

A:对B:错答案:A2.My Most Embarrassing Moment是一个可以写的论文题目。

A:对B:错答案:B3.选题不一定是自己感兴趣的和好奇的。

A:错B:对答案:A4. 1. 在本章中,提到的四个写作技巧是:A:BrainstormingB:Work ScheduleC:Research LogD:Mental Inventory答案:ABCD5.计划书包含下面哪些内容?A:your topic and your thesisB:any special aspects of your projectC:the problems you anticipateD:the kinds of sources you plan to consult答案:ABCD第三章测试1.在进行互联网搜索时,需要注意的规则是:A:to remain your curiosity of the research topic.B:to remain focused on the research topic.C:to review the source, point of view, and completeness of all documents rela ted to the research topic.D:to resist the temptation to be distracted by unrelated sites.答案:BCD2.当你进行批判性阅读时,下面哪些是需要考虑的?A:Do I agree with the writer’s views?B:What are the key ideas in this?C:Does the evidence presented seem reliable, in my experience and using common sense?D:Does the author have any bias (leaning to one side or the other)?E:Are the examples given helpful? Would other examples be better?F:Does the argument of the writer develop logically, step by step?答案:ABCDEF3.浏览和搜索的结合可以帮助你认识到你的研究主题是否过于宽泛,需要缩小范围,并且和单独的浏览或者搜索相比,它更能找到更完整的相关资源。

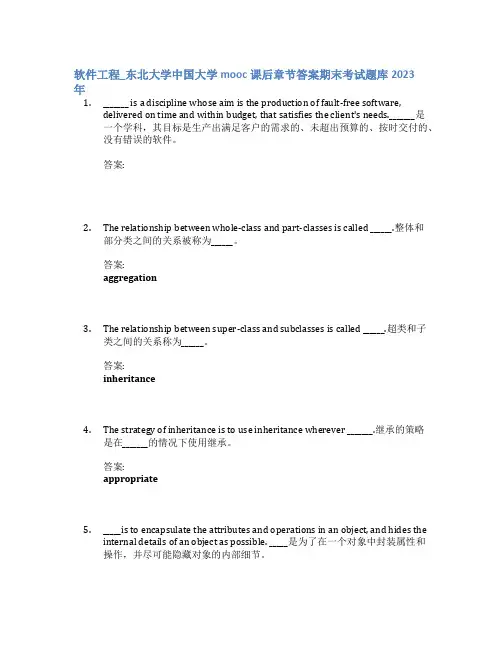

软件工程_东北大学中国大学mooc课后章节答案期末考试题库2023年1._______ is a discipline whose aim is the production of fault-free software,delivered on time and within budget, that satisfies the client's needs._______是一个学科,其目标是生产出满足客户的需求的、未超出预算的、按时交付的、没有错误的软件。

答案:2.The relationship between whole-class and part-classes is called ______.整体和部分类之间的关系被称为______。

答案:aggregation3.The relationship between super-class and subclasses is called ______.超类和子类之间的关系称为______。

答案:inheritance4.The strategy of inheritance is to use inheritance wherever _______.继承的策略是在_______的情况下使用继承。

答案:appropriate5._____is to encapsulate the attributes and operations in an object, and hides theinternal details of an object as possible. _____是为了在一个对象中封装属性和操作,并尽可能隐藏对象的内部细节。

Data encapsulation6.Two modules are ________ coupled if they have write access to global data.如果两个模块对全局数据具有写访问权限,则是________耦合。

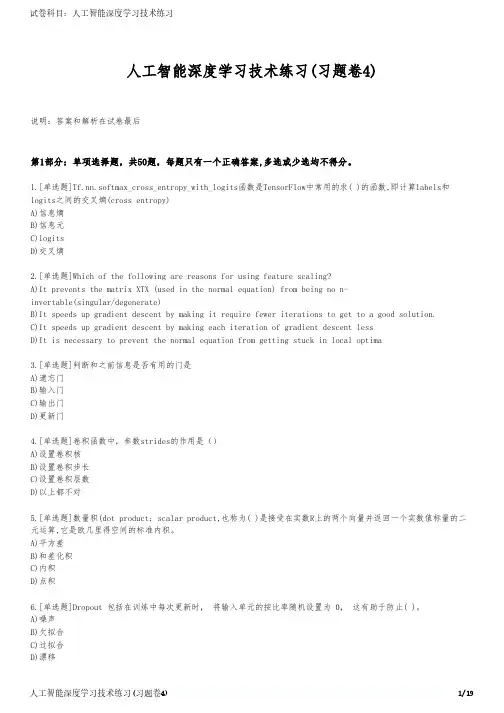

人工智能深度学习技术练习(习题卷4)说明:答案和解析在试卷最后第1部分:单项选择题,共50题,每题只有一个正确答案,多选或少选均不得分。

1.[单选题]Tf.nn.softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits函数是TensorFlow中常用的求( )的函数,即计算labels和logits之间的交叉熵(cross entropy)A)信息熵B)信息元C)logitsD)交叉熵2.[单选题]Which of the following are reasons for using feature scaling?A)It prevents the matrix XTX (used in the normal equation) from being no n-invertable(singular/degenerate)B)It speeds up gradient descent by making it require fewer iterations to get to a good solution.C)It speeds up gradient descent by making each iteration of gradient descent lessD)It is necessary to prevent the normal equation from getting stuck in local optima3.[单选题]判断和之前信息是否有用的门是A)遗忘门B)输入门C)输出门D)更新门4.[单选题]卷积函数中,参数strides的作用是()A)设置卷积核B)设置卷积步长C)设置卷积层数D)以上都不对5.[单选题]数量积(dot product; scalar product,也称为( )是接受在实数R上的两个向量并返回一个实数值标量的二元运算,它是欧几里得空间的标准内积。

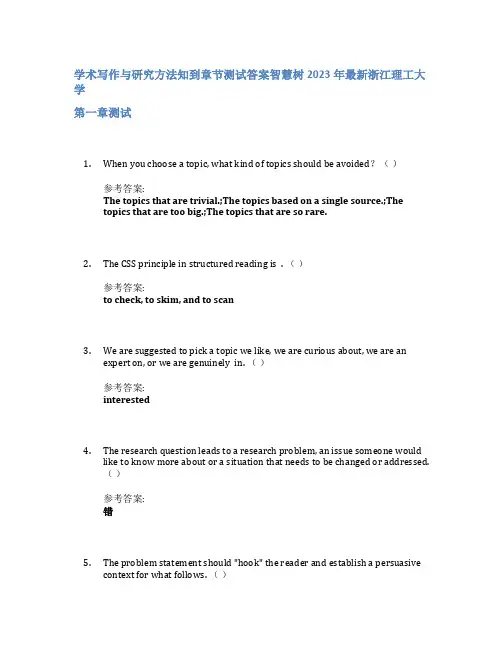

学术写作与研究方法知到章节测试答案智慧树2023年最新浙江理工大学第一章测试1.When you choose a topic, what kind of topics should be avoided?()参考答案:The topics that are trivial.;The topics based on a single source.;Thetopics that are too big.;The topics that are so rare.2.The CSS principle in structured reading is . ()参考答案:to check, to skim, and to scan3.We are suggested to pick a topic we like, we are curious about, we are anexpert on, or we are genuinely in. ()参考答案:interested4.The research question leads to a research problem, an issue someone wouldlike to know more about or a situation that needs to be changed or addressed.()参考答案:错5.The problem statement should "hook" the reader and establish a persuasivecontext for what follows. ()参考答案:对第二章测试1.Which of the following are useful tips to help us in paraphrasing? ()参考答案:Change the sentence structure.;Break the information into separatesentences.;Use synonyms.;Start your first sentence at a different point from that of the original source.2.Which of the following is not a typical feature of an effective topic sentence?()参考答案:A topic sentence can be a question.3.Which of the following is not correct about a concluding sentence? ()参考答案:The concluding sentence may introduce a new idea to this paragraph.4.We can paraphrase other authors’ ideas without citing the sources. ()参考答案:错5. A topic sentence may be the second sentence or a sentence in the middle of aparagraph. ()参考答案:对第三章测试1.The CARS model for Introduction in an academic paper includes thefollowing moves ____. ()参考答案:Establishing a niche;Occupying the niche;Establishing a researchterritory2.In in-text citations, for a work with three or more authors, we should includethe name of only the first author plus ______. ()参考答案:et al.3.Which of the following is an optional step in writing the Introduction of anacademic paper? ()参考答案:Showing that the general research area is important, central,interesting, problematic, or relevant in some way.4.An Abstract should summarize the most important findings of the study. ()参考答案:对5.Plagiarism is the act of presenting the words, ideas, or images of another asyour own. ()参考答案:对第四章测试1.What are the commonly used ways to fix run-on sentences? ()参考答案:Use a subordinating conjunction to turn one of the independent clauses into a dependent clause.;Use a coordinating conjunction with orwithout a comma.;Use a semicolon and an adverbial conjunction (e.g.therefore, however meanwhile, besides, in addition).;Use a full stop (.) to split the run-on sentence into two or more smaller sentences.;Use asemicolon (;) to separate the independent clauses in a run-on sentence.2.Which of the following sentences is concise? ()参考答案:He nodded sympathetically in response to her complaint.3.In which of the following sentences is the article used incorrectly? ()参考答案:Idea can transform the world.4.Though repetition could be a commonly used literary device in prose andpoetry, it should be avoided in academic writing. ()参考答案:对5.“This essay is good.” This sentence is not effective because it is not specificenough. ()参考答案:对。

Python程序设计(英语)智慧树知到课后章节答案2023年下中央财经大学中央财经大学第一章测试1.What is the fundamental question of computer science? ()A:How much money can a programmer make? B:What can be computed?C:What is the most effective programming language? D:How fast can acomputer compute?答案:What can be computed?2. A statement is ()A:a precise description of a problem B:a complete computer command C:a section of an algorithm D:a translation of machine language答案:a complete computer command3.The items listed in the parentheses of a function definition are called ()A:parentheticals B:both B and C are correct C:parameters D:arguments答案:both B and C are correct4.All information that a computer is currently working on is stored in mainmemory. ()A:对 B:错答案:对5. A loop is used to skip over a section of a program. ()A:错 B:对答案:错第二章测试1.Which of the following is not a legal identifier?()A:spAm B:2spam C:spam D:spam4U答案:spam2.In Python, getting user input is done with a special expression called ()A:simultaneous assignment B:input C:for D:read答案:input3.The process of describing exactly what a computer program will do to solve aproblem is called ()A:specification B:programming C:Design D:implementation答案:specification4.In Python, x = x + 1 is a legal statement. ()A:错 B:对答案:对5.The best way to write a program is to immediately type in some code andthen debug it until it works. ()A:对 B:错答案:错第三章测试1.Which of the following is not a built-in Python data type? ()A:int B:rational C:string D:float答案:rational2.The most appropriate data type for storing the value of pi is ()A:string B:int C:float D:irrational答案:float3.The pattern used to compute factorials is ()A:input, process, output B:accumulator C:counted loop D:plaid答案:accumulator4.In Python, 4+5 produces the same result type as 4.0+5.0. ()A:对 B:错答案:错5.Definite loops are loops that execute a known number of times. ()答案:对第四章测试1. A method that changes the state of an object is called a(n) ()A:function B:constructor C:mutator D:accessor答案:mutator2.Which of the following computes the horizontal distance between points p1and p2? ()A:abs(p1.getX( ) - p2.getX( )) B:abs (p1-p2) C:p2.getX( ) - p1.getX( )D:abs(p1.getY( ) - p2.getY( ))答案:abs(p1.getX( ) - p2.getX( ))3.What color is color_rgb (0,255,255)? ()A:Cyan B:Yellow C:Magenta D:Orange答案:Cyan4.The situation where two variables refer to the same object is called aliasing.()A:错 B:对答案:对5. A single point on a graphics screen is called a pixel. ()答案:对第五章测试1.Which of the following is the same as s [0:-1]? ()A:s[:] B:s[:len(s)-1] C:s[-1] D:s[0:len(s)]答案:s[:len(s)-1]2.Which of the following cannot be used to convert a string of digits into anumber? ()A:int B:eval C:str D:float答案:str3.Which string method converts all the characters of a string to upper case? ()A:capwords B:upper C:capitalize D:uppercase答案:upper4.In Python “4”+“5”is “45”. ()A:错 B:对答案:对5.The last character of a strings is at position len(s)-1. ()答案:对第六章测试1. A Python function definition begins with ()A:def B:define C:defun D:function答案:def2.Which of the following is not a reason to use functions? ()A:to demonstrate intellectual superiority B:to reduce code duplication C:tomake a program more self-documenting D:to make a program more modular 答案:to demonstrate intellectual superiority3. A function with no return statement returns ()A:its parameters B:nothing C:its variables D:None答案:None4.The scope of a variable is the area of the program where it may be referenced.()A:对 B:错答案:对5.In Python, a function can return only one value. ()答案:错第七章测试1.In Python, the body of a decision is indicated by ()A:indentation B:curly braces C:parentheses D:a colon答案:indentation2.Placing a decision inside of another decision is an example of ()A:procrastination B:spooning C:cloning D:nesting答案:nesting3.Find a correct algorithm to solve a problem and then strive for ()A:clarity B:efficiency C:scalability D:simplicity答案:clarity;efficiency;scalability;simplicity4.Some modules, which are made to be imported and used by other programs,are referred to as stand-alone programs. ()A:对 B:错答案:错5.If there was no bare except at the end of a try statement and none of theexcept clauses match, the program would still crash. ()答案:对第八章测试1. A loop pattern that asks the user whether to continue on each iteration iscalled a(n) ()A:end-of-file loop B:sentinel loop C:interactive loop D:infinite loop答案:interactive loop2. A loop that never terminates is called ()A:indefinite B:busy C:infinite D:tight答案:infinite3.Which of the following is not a valid rule of Boolean algebra? ()A:a and (b or c) == (a and b) or (a and c) B:(True or False) == True C:not(a and b)== not(a) and not(b) D:(True or x) == True答案:not(a and b)== not(a) and not(b)4.The counted loop pattern uses a definite loop. ()A:错 B:对答案:对5. A sentinel loop should not actually process the sentinel value. ()答案:对第九章测试1.()A:random() >= 66 B:random() < 0.66 C:random() < 66 D:random() >= 0.66答案:random() < 0.662.The arrows in a module hierarchy chart depict ()A:control flow B:one-way streets C:logistic flow D:information flow答案:information flow3.In the racquetball simulation, what data type is returned by the gameOverfunction? ()A:bool B:string C:float D:int答案:bool4. A pseudorandom number generator works by starting with a seed value. ()A:错 B:对答案:对5.Spiral development is an alternative to top-down design. ()A:错 B:对答案:错第十章测试1. A method definition is similar to a(n) ()A:module B:import statement C:function definition D:loop答案:function definition2.Which of the following methods is NOT part of the Button class in thischapter? ()A:activate B:clicked C:setLabel D:deactivate答案:setLabel3.Which of the following methods is part of the DieView class in this chapter?()A:setColor B:clicked C:setValue D:activate答案:setValue4.New objects are created by invoking a constructor. ()A:对 B:错答案:对5.A:错 B:对答案:错第十一章测试1.The method that adds a single item to the end of a list is ()A:plus B:add C:append D:extend答案:append2.Which of the following expressions correctly tests if x is even? ()A:not odd (x) B:x % 2 == 0 C:x % 2 == x D:even (x)答案:x % 2 == 03.Items can be removed from a list with the del operator. ()A:错 B:对答案:对4.Unlike strings, Python lists are not mutable. ()A:对 B:错答案:错5.()A:对 B:错答案:错第十二章测试1.Which of the following was NOT a class in the racquetball simulation? ()A:SimStats B:Player C:RBallGame D:Score答案:Score2.What is the data type of server in an RBallGame? ()A:SimStats B:bool C:int D:Player答案:Player3.The setValue method redefined in ColorDieView class is an example of ()A:polymorphism B:generality C:encapsulation D:inheritance答案:polymorphism;inheritance4.Hiding the details of an object in a class definition is called instantiation. ()A:对 B:错答案:错5.Typically, the design process involves considerable trial and error. ()A:错 B:对答案:对。

学术英语(下)智慧树知到课后章节答案2023年下华南理工大学华南理工大学模块一测试1.How can we begin an academic text? ( )答案:Briefly describe the primary setting of the text;Open with a riddle, joke or story;State the thesis briefly and directly;Pose a question related to the subject2.When a researcher is first introduced, which kind of information should beincluded? ( )答案:Full name and contact information;Current position and general interest;Awards received3.The abstract usually displays the text’s purpose, the main problem orquestion it answers, research methods, research subjects, and the mainfindings. ( )答案:对nguage patterns, such as “however”, “whereas” and “despite”, are the onlydevices to show the contradictory or contrast relationship between the two ideas. ( )答案:错5. A good opening often has the functions of ( ).答案:providing information to orient readers;showing the focus of the text;introducing the topic of the text6.What should be avoided when you first introduce a researcher? ( )答案:Make the introduction redundant and casual模块二测试1.Which of the following components is Not necessary for an argumentativeessay? ( )答案:counterargument2.Which of the following statements is Not true about the Toulmin model? ( )答案:It is useful for making simple arguments.3.What does “compare” mean in a compare and contrast essay? ()答案:to identify the similarities between the subjects4.To write a good compare and contrast essay, what should the author do first?( )答案:Choose the subjects.5.How many types are there for the Block structure of a cause and effect essay?( )答案:two6.Which step is Not necessary for writing a cause and effect essay? ( )答案:Collect opposing opinions7.What is a problem-solution essay used for? ( )答案:Discussing possible methods to solve the problem.模块三测试1.Which of the following verbs can be used to introduce a citation in a seminar?( )答案:reveal2.When mentioning the author/authors of the resources, we should alwaysmention the full name. ( )答案:错3.Which of the following should not be mentioned in your evaluation of a textwhen you are attending a seminar? ( )答案:The detailed information of the author or the research team.4.After presenting your view, hypothetical examples are not allowed to be usedto support your idea. ( )答案:错5.Which of the following is not a clarifying question? ( )答案:Is there evidence to your claim?模块四测试1.When we identify the pros in an academic material, we should pay attentionto the key words like ( ).答案:advantage;positive2.In our daily life, choosing what food to eat for lunch is a kind of comparison.( )答案:对3.While following a lecture, you can try key words, symbols and abbreviationsin your notes to save time and catch up with the speaker. ()答案:对4. A linear system usually has headings at different levels.()答案:对5.The Cornell method of taking notes was developed by Dr. Walter Pauk ofHarvard University. ()答案:错6.In a charting system, you need to draw a chart and then fill in the facts in theappropriate blanks.()答案:对7. A fact is a statement that is true and can be proven.()答案:对模块五测试1.When a researcher is first introduced in a text, which of the followinginformation is not provided? ( )答案:age2.What is the thesis of the text “Working with Robots: Human and MachineCoexistence in the Workforce” (Book 2, Unit 5)? ()答案:Human and machine will work together.3.Which of the following should be included in the introduction? ()答案:A thesis statement.4.With regard to children’s health, the author’s attitude towards social media is( ).答案:negative5.The outbreak of intense anger might cause a heart attack. ( )答案:对6.The author uses a Dove commercial to attract readers. The short video tellsthe audience through an experiment that you are more beautiful in the eyes of others than you are in your own.()答案:对7.Quotations can be classified into direct and indirect quotations. ()答案:对。

小学上册英语第3单元寒假试卷(含答案)英语试题一、综合题(本题有50小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1 A non-metal typically has a ______ melting point.2 What do you call the event where you celebrate someone's birthday?A. PartyB. FestivalC. GatheringD. Ceremony答案: A3 In conclusion, I believe that life is full of __________. Each day brings new opportunities to __________ and learn something new. I hope to continue exploring and experiencing all the wonderful things the world has to offer.4 Which animal lives in a den?A. FoxB. BirdC. FishD. Cow答案:A5 Where do fish live?A. TreesB. SkyC. WaterD. Land6 The ________ has sharp edges.7 Chemical reactions can be spontaneous or ______.8 The ______ (老虎) has powerful muscles for hunting.9 A solid has a ______ shape and volume.10 Which of these is a fruit?A. CarrotB. PotatoC. AppleD. Broccoli答案: C11 The ice cream is melting ___ (quickly/slowly).12 The Earth's crust is constantly undergoing changes due to ______ and erosion.13 The Earth's structure can be understood through the study of ______ waves.14 They are ___ to music. (dancing)15 What is the name of the famous festival celebrated in India?A. DiwaliB. EidC. ThanksgivingD. Christmas答案:A16 I like to listen to ________ (广播) in the car.17 __________ are substances that absorb heat in a reaction.18 Learning about _____ (传统) plants is interesting.19 What do you wear on your feet?A. HatB. GlovesC. ShoesD. Scarf答案:C20 What is the primary ingredient in a traditional curry?A. RiceB. MeatC. SpicesD. Vegetables21 What is the name of the famous landmark in Paris?A. Eiffel TowerB. Louvre MuseumC. Arc de TriompheD. All of the above答案: D. All of the above22 Astronomy requires careful observation and ______.23 The chemical symbol for antimony is _______.24 The clock shows ___ o’clock. (five)25 What do you call a tree that loses its leaves in winter?A. EvergreenB. DeciduousC. PalmD. Fruit答案: B26 What do we call the part of the plant that grows above ground?A. RootB. StemC. LeafD. Flower答案:B27 The _____ (生长速度) of plants varies widely.28 What do you call a person who repairs shoes?A. CobblerB. TailorC. MechanicD. Barber答案: A29 A __________ (压强) can affect the behavior of gases.30 I found a ___ (coin) on the ground.31 When a substance dissolves, it forms a ______.32 What do we call the person who teaches students?A. DoctorB. TeacherC. ChefD. Engineer答案: B33 The sun is ___ in the sky. (bright)34 I enjoy cooking with my family. We often make __________ together.35 Which planet is closest to the sun?A. EarthB. MercuryC. VenusD. Mars答案:B36 All living things are made of ______.37 Christopher Columbus discovered America in the year ________.38 What is the common term for a hurricane in the western Pacific?A. TyphoonB. CycloneC. TornadoD. Monsoon答案:A39 __________ (水分子) are polar, allowing for hydrogen bonding.40 What do you call the layer of air surrounding the Earth?A. AtmosphereB. HydrosphereC. LithosphereD. Biosphere41 We should _______ (help/ignore) each other.42 What do you call a person who plays music?A. SingerB. MusicianC. PerformerD. All of the above43 The _____ (cabbage) is a leafy vegetable.44 The frog's broad mouth helps it catch ______ (昆虫).45 A ____ is a small mammal that loves to dig in the ground.46 The bird is ______ (flying) in the sky.47 They are _____ (cooking/eating) dinner together.48 My dad is a great __________ (鼓励者) who inspires me.49 The first man to fly solo across the Atlantic was ________ (林白).50 My cousin is a __________ athlete. (出色的)51 __________ are used to indicate pH levels in solutions.52 What is the color of a typical sunflower?A. YellowB. GreenC. BlueD. Red答案:A53 What is the name of the famous ancient city in Ethiopia?A. AxumB. LalibelaC. GondarD. All of the above54 What do we call the place where we keep books?A. LibraryB. BookstoreC. ArchiveD. Museum答案:A55 I like to help my mom ________ (种花) in the garden.56 What is the name of the device used to measure temperature?A. BarometerB. ThermometerC. AnemometerD. Hygrometer答案:B. Thermometer57 Did you see the _____ (小兔) hopping away?58 Spectroscopy helps scientists determine the composition of _______.59 The chemical symbol for gallium is _______.60 The ________ (生态恢复行动) is ongoing.61 My favorite thing to do is ________ (参观博物馆).62 What do we call the place where we go to learn about art?A. MuseumB. SchoolC. GalleryD. Studio63 I have a _____ (小汽车) that I can race with my friends. 我有一辆可以和朋友们比赛的小汽车。

高二英语询问研究单选题50题1. In a research about the eating habits of high school students, the first step is to clearly define _____.A. what the research aims to achieveB. how to collect dataC. who will participate in the researchD. where to conduct the research答案:C。

解析:这道题考查研究的相关要素。

选项A是研究目的,虽然在研究中很重要,但第一步是确定研究对象,所以A错误。

选项B是关于数据收集的方式,这不是研究开始的第一步,B错误。

选项C,在研究高中生饮食习惯时,首先要确定谁来参与研究,也就是研究对象,C正确。

选项D是研究地点,这也不是研究开始首先要确定的内容,D错误。

2. A research on the influence of mobile phones on teenagers' study, we need to consider _____ as a key factor in the early stage.A. the types of mobile phonesB. the age range of teenagersC. the cost of mobile phonesD. the brand of mobile phones答案:B。

解析:对于研究手机对青少年学习的影响,在早期阶段关键因素是确定青少年的年龄范围,因为不同年龄段可能受影响的程度不同。

选项A手机类型不是早期关键因素,A错误。

选项C手机成本与对学习的影响关联不大,C错误。

选项D手机品牌也不是研究早期要考虑的关键,D错误。

3. When conducting a research on the effectiveness of a new teaching method, the researchers should first focus on _____.A. the popularity of the old teaching methodB. the characteristics of the students who will be taughtC. the cost of implementing the new teaching methodD. the time needed to complete the research答案:B。

高中二年级英语学术论文摘要理解单选题40题1.The research focuses on the impact of different factors on learning outcomes. Here, "outcomes" refers to _____.A.resultsB.processesC.methodsD.theories答案:A。

“outcomes”在这个句子中的意思是结果,A 选项“results”也是结果的意思,符合语境。

B 选项“processes”是过程;C 选项“methods”是方法;D 选项“theories”是理论。

在这个句子中,研究聚焦在不同因素对学习结果的影响,所以“outcomes”应该是结果,而不是过程、方法或理论。

2.The study examines the role of various elements in educational systems. "elements" here mean _____.ponentsB.problemsC.solutionsD.examples答案:A。

“elements”在这个句子中表示组成部分、要素,A 选项“components”也是组成部分的意思,符合语境。

B 选项“problems”是问题;C 选项“solutions”是解决方案;D 选项“examples”是例子。

在这个句子中,研究检查各种要素在教育系统中的作用,所以“elements”应该是组成部分,而不是问题、解决方案或例子。

3.The paper discusses the significance of new technologies in modern society. "significance" is closest in meaning to _____.A.importanceB.difficultyC.quantityD.speed答案:A。