I SOTOPIC G EOCHEMISTRY OF THE C ONTINENTAL

C RUST II

I SOTOPIC C OMPOSITION OF THE

L OWER C RUST

Like the mantle, the lower continen-tal crust is not generally available for

sampling. While much can be learned about the lower crust through remote geophysical means (seismic waves,gravity, heat flow, etc.), defining its composition and history depends on be-ing able to obtain samples of it. As with the mantle, three kinds of samples are available: terrains or massifs t h a t

have been tectonicly emplaced in the

upper crust, xenoliths in igneous rocks,and magmas produced by partial melt-ing of the lower crust. All these kinds of samples have been used and each has advantages and dissadvantages similar to mantle samples. We will concentrate here on xenoliths and terrains.

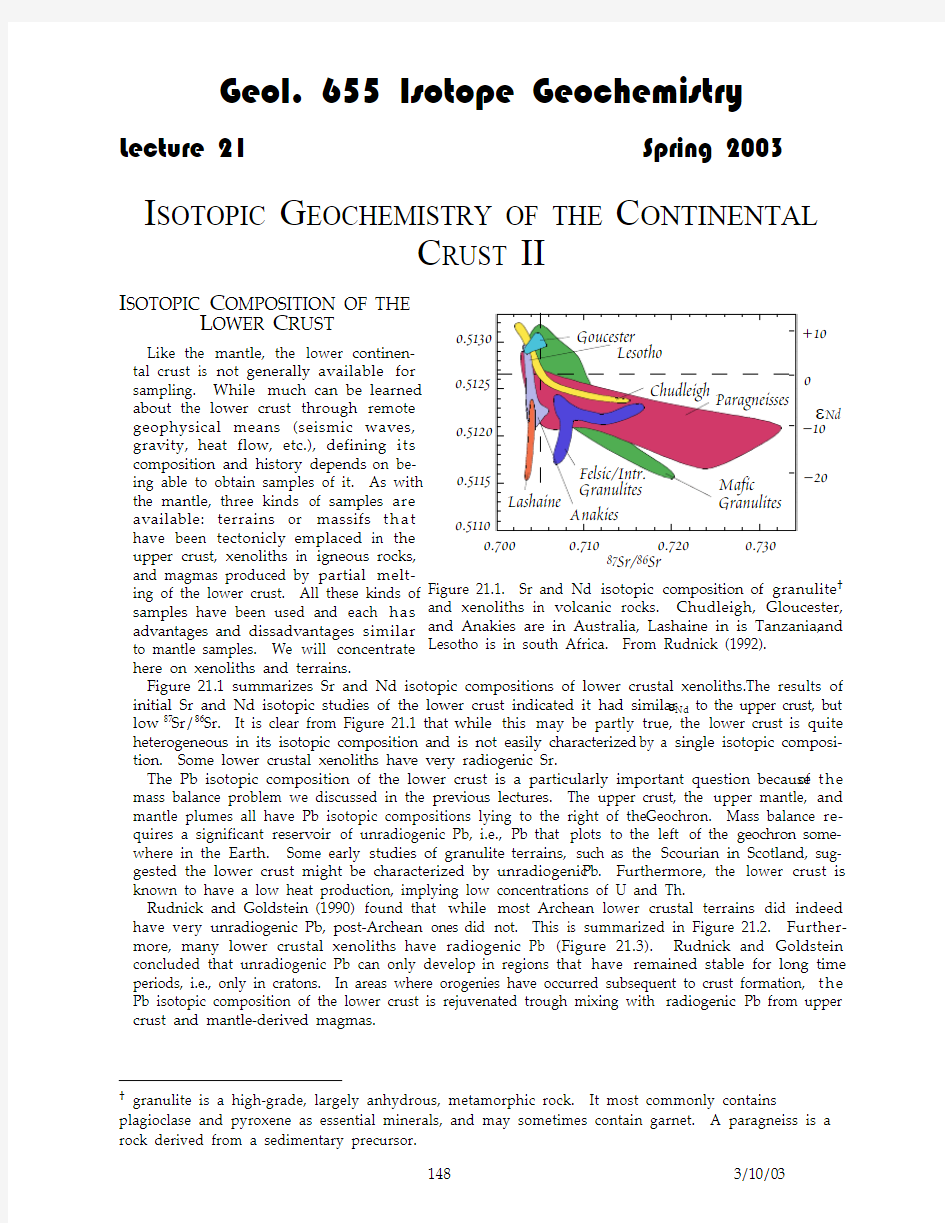

Figure 21.1 summarizes Sr and Nd isotopic compositions of lower crustal xenoliths. The results of initial Sr and Nd isotopic studies of the lower crust indicated it had similar e Nd to the upper crust, but low 87Sr/86Sr. It is clear from Figure 21.1 that while this may be partly true, the lower crust is quite heterogeneous in its isotopic composition and is not easily characterized by a single isotopic composi-tion. Some lower crustal xenoliths have very radiogenic Sr.

The Pb isotopic composition of the lower crust is a particularly important question because of the mass balance problem we discussed in the previous lectures. The upper crust, the upper mantle, and mantle plumes all have Pb isotopic compositions lying to the right of the Geochron. Mass balance re-quires a significant reservoir of unradiogenic Pb, i.e., Pb that plots to the left of the geochron some-where in the Earth. Some early studies of granulite terrains, such as the Scourian in Scotland, sug-gested the lower crust might be characterized by unradiogenic Pb. Furthermore, the lower crust is known to have a low heat production, implying low concentrations of U and Th.

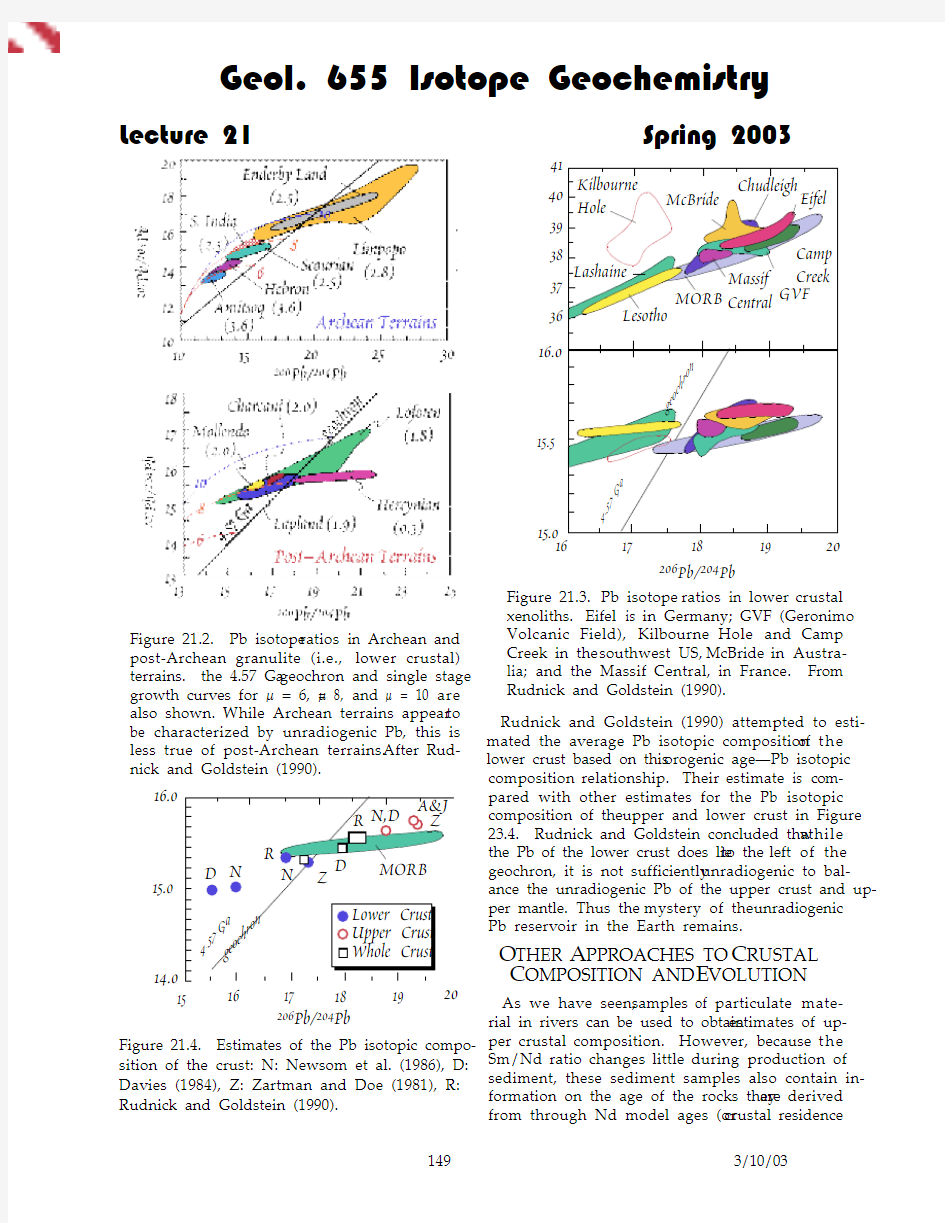

Rudnick and Goldstein (1990) found that while most Archean lower crustal terrains did indeed have very unradiogenic Pb, post-Archean ones did not. This is summarized in Figure 21.2. Further-more, many lower crustal xenoliths have radiogenic Pb (Figure 21.3). Rudnick and Goldstein concluded that unradiogenic Pb can only develop in regions that have remained stable for long time periods, i.e., only in cratons. In areas where orogenies have occurred subsequent to crust formation, the Pb isotopic composition of the lower crust is rejuvenated trough mixing with radiogenic Pb from upper crust and mantle-derived magmas.

? granulite is a high-grade, largely anhydrous, metamorphic rock. It most commonly contains

plagioclase and pyroxene as essential minerals, and may sometimes contain garnet. A paragneiss is a rock derived from a sedimentary precursor.

+10

–10–200.5130

0.5125

0.51150.511087Sr/86Sr

e Nd 143N d /144N d

Figure 21.1. Sr and Nd isotopic composition of granulite ?

and xenoliths in volcanic rocks. Chudleigh, Gloucester,and Anakies are in Australia, Lashaine in is Tanzania, and Lesotho is in south Africa. From Rudnick (1992).

Rudnick and Goldstein (1990) attempted to esti-mated the average Pb isotopic composition of the lower crust based on this orogenic age—Pb isotopic composition relationship. Their estimate is com-pared with other estimates for the Pb isotopic composition of the upper and lower crust in Figure 23.4. Rudnick and Goldstein concluded that while the Pb of the lower crust does lie to the left of the geochron, it is not sufficiently unradiogenic to bal-ance the unradiogenic Pb of the upper crust and up-per mantle. Thus the mystery of the unradiogenic Pb reservoir in the Earth remains.

O THER A PPROACHES TO C RUSTAL C OMPOSITION AND E VOLUTION

As we have seen, samples of particulate mate-rial in rivers can be used to obtain estimates of up-per crustal composition. However, because the Sm/Nd ratio changes little during production of sediment, these sediment samples also contain in-formation on the age of the rocks they are derived from through Nd model ages (or crustal

residence

Figure 21.2. Pb isotope ratios in Archean and post-Archean granulite (i.e., lower crustal)terrains. the 4.57 Ga geochron and single stage growth curves for μ = 6, μ = 8, and μ = 10 are also shown. While Archean terrains appear to be characterized by unradiogenic Pb, this is less true of post-Archean terrains. After Rud-nick and Goldstein (1990).

15.5

15.0206Pb/204Pb

207P b /204P b

208P b /204P b

Figure 21.3. Pb isotope ratios in lower crustal xenoliths. Eifel is in Germany; GVF (Geronimo Volcanic Field), Kilbourne Hole and Camp Creek in the southwest US, McBride in Austra-lia; and the Massif Central, in France. From Rudnick and Goldstein (1990).

206Pb/204Pb

15

16.0

15.0

14.0207P b /204P b

Figure 21.4. Estimates of the Pb isotopic compo-sition of the crust: N: Newsom et al. (1986), D:Davies (1984), Z: Zartman and Doe (1981), R:Rudnick and Goldstein (1990).

time). Sm/Nd and 143Nd/144Nd ratios in major rivers draining about 25% of the exposed continental crust (excluding Antarctica and Australia) as well as sam-ples of loess and aeolian dusts were analyzed by Gold-stein and O’Nions (a different Steve Goldstein than the Steve Goldstein of the Goldstein and Jacobsen pa-pers) are shown in Figure 21.5. The Nd isotope ratios

are fairly homogeneous. Sm/Nd ratios are quite uni-form, illustrating a point which was already well

known, namely that rare earth patterns of continental

crustal material show relatively little variation. A

further illustration of this point is shown in Figure

21.6. Virtually all crustal rocks have 147Sm/144Nd ra-tios at the extreme end of the range observed in mantle-derived rocks, and the range of 147Sm/144Nd ratios in crustal material is small compared to the range ob-served in mantle-derived rocks. Figure 21.6 suggests there is a major fractionation of the Sm/Nd when crust is formed from the mantle, but thereafter processes within the crust tend to have only second-order effects on the Sm/Nd ratio. This is the main reason why crus-tal residence time calculated from 147Sm/144Nd and 143Nd/144Nd is such a robust parameter.

By studying sediments of various ages, we should be

able to draw some inferences about the rates of conti-nental growth. Goldstein and O'Nions (1984) found that the mean crustal residence time (t DM , calculated f r o m 147Sm/144N d and 143Nd/144

Nd) of the river particulates they studied was 1.7 Ga, which they in-terpreted as the mean age of the crust being eroded. However, they estimated the mean crustal residence t i m e o f t h e e n t i r e sedimentary mass to be about 1.9 Ga. Figure 21.7 compares the stratigraphic age * of sediments with their crustal residence ages. Note that in general we expect the crustal residence age will be somewhat older than the stratigraphic age. Only when a rock is eroded into

* The stratigraphic age is the age of deposition of the sediment determined by conventional

geochronological or geological means.

N o . o f A n a l y s e s

147Sm/144

Nd 2684N o . o f A n a l y s e s

10143Nd/144Nd Figure 21.5. 147Sm/144Nd and 143Nd/144Nd

ratios in major rivers, aeolian dusts, and

loess (from Goldstein and O'Nions, 1984).

0.5110

0.5130

147Sm/144Nd

144143Nd Figure 21.6. 147Sm/144Nd and 143Nd/144Nd in various crustal and mantle-derived rocks (from Goldstein and O'Nions, 1984).

the sedimentary mass immediately after its deri-vation from the mantle will its stratigraphic (t ST )and crustal residence age (t CR ) be equal.

The top diagram illustrates the relationships be-tween t ST and t CR that we would expect to see for various crustal growth scenarios, assuming there is a relationship between the amount of new material added to the continents and the amount of new ma-terial added to the sedimentary mass. If the conti-nents had been created 4.0 Ga ago and if there had been no new additions to continental crust since t h a t time, then the crustal residence time of all sedi-ments should be 4.0 Ga regardless of stratigraphic age, which is illustrated by the line labeled 'No New Input'. If, on the other hand, the rate of conti-nent growth through time has been uniform since 4.0Ga, then t ST and t CR of the sedimentary mass should lie along a line with slope of 1/2, which is the line labeled 'Uniform Rate'. The reason for this is as follows. If the sedimentary mass at any given time samples the crust in a representative fashion, then t CR of the sedimentary mass at the time of its depo-sition (at t ST ) should be (4.0-t ST )/2?, i.e., the mean time between the start of crustal growth (which we arbitrarily assume to be 4.0 Ga) and t ST . A scenario where the rate of crustal growth decreases with time is essentially intermediate between the one-time crust creation at 4.0 and the uniform growth

rate case. Therefore, we would expect the decreas-ing rate scenario to follow a trend intermediate be-tween these two, for example, the line labeled 'Decreasing Rate'. On the other hand, if the rate

has increased with time, the t CR of the sedimentary

mass would be younger than in the case of uniform growth rate, but still must be older than t ST , so this scenario should follow a path between the uniform growth rate case and the line t ST = t CR , for exam-ple, the line labeled 'Increasing Rate'.

Line A in Figure 21.7b is the uniform growth rate line with a slope of 1/2. Thus the data seem to be compatible with a uniform rate of growth of the continental crust. However, the situation is compli-cated by various forms of recycling, including sediment-to-sediment and sediment-to-crystalline rock,and crust-to-mantle. Goldstein and O'Nions noted sedimentary mass is cannibalistic: sediments are

? One way to rationalized this equation is to think of newly deposited sediment at t

ST as a 50-50

mixture of material derived from the mantle at 4.0 Ga and t ST . The equation for the T CR of this mixture would be:

t CR =

4.0+t ST

2

.At time of deposition, its crustal residence age would have been: t CR =

4.0+t ST 2– t ST = 4.0t ST

2

.You could satisfy yourself that a mixture of material having t CR of all ages between 4.0 Ga and

t ST

would have the same t CR as given by this equation.

Figure 21.7. Relationship between strati-graphic age of sediments and the crustal resi-dence age of material in sediments. See text for discussion (from Goldstein and O'Nions,1984).

eroded and redeposited. In general, the sedimentary mass follows an exponential decay function with a half-mass age of about 500 Ma. This means, for example, that half the sedimentary mass was de-posited within the last 500 Ma, the other half of the sedimentary mass has a depositional age of over 500 Ma. Only 25% of sediments would have a depositional ('stratigraphic') age older than 1000 Ma, and only 12.5% would have a stratigraphic age older than 1500 Ma, etc. Line B represents the evolution of the source of sediments for the conditions that the half-mass stratigraphic age is always 500 Ma and this age distribution is the result of erosion and re-deposition of old sediments. The line curves upward because in younger sediments consist partly of redeposited older sediments. In this pro-cess, t ST of this cannibalized sediment changes, but t CR does not. Goldstein and O'Nions noted their data could also be compatible with models, such as that of Armstrong, which have a near constancy of continental mass since the Archean if there was a fast but constantly decreasing rate of continent-to-mantle recycling.

We should emphasize that the t CR of sediments is likely to be younger than the mean age of the crust. This is so because sediments preferentially sample material from topographically high areas and topographically high areas tend to be younger than older areas of the crust (e.g. the shields or cratons) because young areas tend to be still relatively hot and therefore high (due to thermal expan-sion of the lithosphere).

R EFERENCES AND S UGGESTIONS FOR F URTHER R EADING

Davies, G. F., Geophysical and isotopic constraints on mantle convection: An interim synthesis., J. Geophys. Res.,89, 6017-6040, 1984.

Goldstein, S. L., R. K. O,Nions, and P. J. Hamilton, A Sm-Nd study of atmospheric dusts and particu-lates from major river systems, Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett., 70, 221-236, 1986.

Newsom, H. E., W. M. White, K. P. Jochum, and A. W. Hofmann, Siderophile and chalcophile ele-ment abundances in oceanic basalts, Pb isotope evolution and growth of the Earth's core., Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.,80, 299-313, 1986.

Rudnick, R. L., and S. L. Goldstein, The Pb isotopic compositions of lower crustal xenoliths and the evolution of lower crustal Pb, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.,98, 192-207, 1990.

Rudnick, R. L., Xenoliths — samples of the lower crust, in Continental Lower Crust, vol. edited by D. M. Fountain, R. Arculus, and R. W. Kay, 269-316 pp., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1992.

Zartman, R. E., and B. R. Doe, Plumbotectonics: The Model, Tectonophysics,75, 135-162, 1981.

同位素地球化学论文 近年来,随着同位素样片制备技术的改进和高精度质谱的问世,大大地提高了同位素测试结果的精度和准确性,使同位素地球化学的理论和方法进一步成熟和完善,研究领域不断拓宽。 同位素地球化学研究内容 同位素地球化学是根据自然界的核衰变、裂变及其他核反应过程所引起的同位素变异,以及物理、化学和生物过程引起的同位素分馏,研究天体、地球以及各种地质体的形成时间、物质来源与演化历史。 同位素地质年代学已建立了一整套同位素年龄测定方法,为地球与天体的演化提供了重要的时间座标。比如已经测得太阳系各行星形成的年龄为45~46亿年,太阳系元素的年龄为50~58亿年等等。 另外在矿产资源研究中,同位素地球化学可以提供成岩、成矿作用的多方面信息,为探索某些地质体和矿床的形成机制和物质来源提供依据。 ①自然界同位素的起源、演化和衰亡历史。 ②同位素在宇宙体、地球及其各圈层中的分布分配、不同地质体中的丰度及其在地质过程中活化与迁移、富集与亏损、衰变与增长的规律;同位素组成变异的原因;并据此探讨地质作用的演化历史和物质来源。 ③利用放射性同位素的衰变定律建立一套有效的同位素计时方法,测定不同天体事件的年龄,并作出合理的解释,为地球和太阳系的演化确定时间坐标。 根据同位素的性质,同位素地球化学研究领域主要分稳定同位素地球化学和同位素年代学两个方面。稳定同位素地球化学主要研究自然界中稳定同位素的丰度及其变化。同位素年代学随研究领域的深入,又分为同位素地质年代学和宇宙年代学。同位素地质年代学主要研究地球及其地质体的年龄和演化历史。宇宙年代学则主要研究天体的年龄和演化历史。 自然界同位素成分变化

水文地球化学研究现状、基本模型与进展 摘要:1938 年, “水文地球化学”术语提出, 至今水文地球化学作为一门 独立的学科得到长足的发展, 其服务领域不断扩大。当今水文地球化学研究的理论已经广泛地应用在油田水、海洋水、地热水、地下水质与地方病以及地下水微生物等诸多领域的研究。其研究方法也日臻完善。随着化学热力学和化学动力学方法及同位素方法的深入研究, 以及人类开发资源和保护生态的需要, 水文地球化学必将在多学科的交叉和渗透中拓展研究领域, 并在基础理论及定量化研究方面取得新的进展。 早期的水文地球化学工作主要围绕查明区域水文地质条件而展开, 在地下水的勘探开发利用方面取得了可喜的成果( 沈照理, 1985) 。水文地球化学在利用地下水化学成分资料, 特别是在查明地下水 的补给、迳流与排泄条件及阐明地下水成因与资源的性质上卓有成效。20 世纪60 年代后, 水文地球化学向更深更广的领域延伸, 更多地是注重地下水在地壳层中所起的地球化学作用( 任福弘, 1993) 。 1981 年, Stumm W 等出版了5水化学) ) ) 天然水化学平衡导论6 专著, 较系统地提供了定量处理天然水环境中各种化学过程的方法。1992 年, C P 克拉依诺夫等著5水文地球化学6分为理论水文地球化学及应用水文地球化学两部分, 全面论述了地下水地球化学成分的形成、迁移及化学热力学引入水文地球化学研究的理论问题, 以及水文地球化学在饮用水、矿水、地下热水、工业原料水、找矿、地震预报、防止地下水污染、水文地球化学预测及模拟中的应用等, 概括了20 世纪80 年代末期水文地球化学的研究水平。特别是近二十年来计算机科学的飞速发展使得水文地球化学研究中的一些非线性问题得到解答( 谭凯旋, 1998) , 逐渐构架起更为严密的科学体系。 1 应用水文地球化学学科的研究现状 1. 1 油田水研究 水文地球化学的研究在对油气资源的勘查和预测以及提高勘探成效和采收率等方面作出了重要的贡献。早期油田水地球化学的研究只是对单个盆地或单个坳陷, 甚至单个凹陷进行研究, 并且对于找油标志存在不同见解。此时油田水化学成分分类主要沿用B A 苏林于1946 年形成的分类。1965 年, E C加费里连科在其所著5根据地下水化学组分和同位素成分确定含油气性的水文地球化学指标6中系统论述了油气田水文地球化学特征及寻找油气田的水文地球化学方法。1975 年, A G Collins 在其5油田水地球化学6中论述了油田水中有机及无机组分形成的地球化学作用( 汪蕴璞, 1987) 。1994 年, 汪蕴璞等对中国典型盆地油田水进行了系统和完整的研究, 总结了中国油田水化学成分的形成分布和成藏规律性, 特别是总结了陆相油田水地球化学理论, 对油田水中宏量组分、微量组分、同位素等开展了研究, 并对油田水成分进行种类计算, 从水化学的整体上研究其聚散、共生规律和综合评价找油标志和形成机理。同时还开展了模拟实验、化学动力学和热力学计算, 从定量上探索油田水化学组分的地球化学行为和形成机理。 1. 2 洋底矿藏研究

第十讲 地质常用主要稳定同位素简介 18O Full atmospheric General Circulation Model (GCM) with water isotope fractionation included.

内容提要 ●基本特征●氢同位素●碳同位素●氧同位素●硫同位素

10.1. 传统稳定同位素基本特征 ?只有在自然过程中其同位素分馏变化为可测量范围的元素,才能应用于地质研究用途,这些元素的质量范围多<40; ?多为能形成固、气、液多相态物质的元素,其稳定同位素组成可发生较大程度变化。总体上,重同位素趋于在结合紧密的固相物质中富集;重同位素趋于在氧化价态最高的物相中富集; ?生物系统中的同位素变化常用动力效应来解释。在生物作用过程中(如光合作用、细菌反应及其它微生物过程),相对于反应初始组成,轻同位素趋于在反应生成物中富集。

10.2. 氢(hydrogen) ?直到1930年代,人们才发现H不是由1 个同位素,而是由两个同位素组成: 1H:99.9844% 2H(D):0.0156% ?在SMOW中D/H=155.8 10-6 ?氢还有一个同位素氚(3H),但为放射性核素,半衰期仅为~12.5y。

10.2.1 氢同位素基本特征 ?与多数重元素的同位素组成不同,太阳系物质具有高度不均一的氢(氧)同位素组成,尤其是内地行星与彗星之间; ?1H与D同位素间质量相对差最大,在地球样品中表现出最大的稳定同位素变化(分馏)范围; ?从大气圈、水圈直至地球深部,氢总是以H O、OH-, 2 H2、CH4等形式存在,即在各种地质过程中起着重要作用; ?氢同位素以 D表示,其同位素测量精度通常为0.5‰至2‰(相对其它稳定同位素偏低)。

《水文地球化学》教学大纲 Hydrogeochemistry-Course Outline 第一部分大纲说明 一、课程的性质、目的与任务 《水文地球化学》是水文与水资源工程专业本科生必修的一门主要专业基础课。通过本课程的学习,使学生掌握水文地球化学的基本原理和学会初步运用化学原理解决天然水的地球化学问题和人类对天然水的影响问题的方法与手段,为学习后续课程和专业技术工作打下基础。 二、与其它课程的联系 学习本课程应具备普通地质学、综合地质学、工程化学和水文地质学的基础。后续课程为水质分析实验、铀水文地球化学、环境水文地质学和水文地质勘察。 三、课程的特点 1.对基本概念、基本规律与常见的应用方法的理解并重。 2.对基本理论与常见水文地球化学问题的定量计算方法的掌握并重。 3. 采用英文教材,中、英语混合授课。 四、教学总体要求 1.掌握水文地球化学的基本概念、基本规律与研究方法。 2.掌握控制地下水与地表水化学成分的主要作用:酸碱反应与碳酸盐系统;矿物风化与矿物表面过程;氧化-还原反应;有机水文地球化学作用等。 3.通过理论讲述、研究实例分析与习题课,使学生理解天然水中常见的化学组份与同位素组成,掌握最基本的地球化学模拟方法与整理水化学数据的能力。 五、本课程的学时分配表 编 号教学内容课堂讲 课学时 习题课 学时 实验课 学时 自学 学时 1 引言及化学背景 (Introduction and Chemical Background) 6 2 酸碱反应与碳酸盐系统 (Acid-Base Reactions and the Carbonate System) 4 2 3 矿物风化与矿物表面过程 Mineral weathering and mineral surface processes 6

同位素地球化学复习题 1.1同位素地球化学的基本任务 1)研究自然界同位素的起源、演化和衰亡历史; 2)研究同位素在宇宙体、地球和各地质体中的分布分配、不同地质体中的丰度及典型地质过程中活化与迁移、富集与亏损、衰变与增长的规律;阐明同位素组成变异的原因。据此来探讨地质作用的演化历史及物质来源; 3)利用放射性同位素的衰变定律建立一套行之有效的同位素计时方法,测定不同天体事件和地质事件的年龄,并作出合理的解释,为地球和太阳系的演化确定时标。 4 )研究同位素分馏与温度的关系,建立同位素温度计,为地质体的形成与演化研究提供温标。 1.2 同位素地球化学的一些基本概念 核素同位素同量异位素稳定同位素放射性同位素重稳定同位素轻稳定同位素 2.1 质谱仪的基本结构 四个部分:进样系统离子源质量分析器离子接收器 2.2 衡量质谱仪的技术标准有哪些 质量数范围分辨率灵敏度精密度与准确度 2.3 固体质谱分析为什么要进行化学分离 具相同质量的原子和分子离子的干扰; 主要元素基体中微量元素的稀释; 低的离子化效率; 不稳定发射。 2.5 同位素稀释法是用于元素含量分析还是用于同位素比值分析?元素含量分析 2.6 氢气的制取方法?(有哪些还原剂) U-还原法Zn -还原法Mg -还原法Cr -还原法 2.7 氧同位素的制样方法有哪些? 1. 大量水样氧同位素制样方法? 2. 硅酸盐氧同位素的BrF5法制样原理? 3. 碳酸盐样品的磷酸盐制样法(McCrea法) 2.8 水中溶解碳的提取与制样McCrea法 2.9 硫化物硫同位素直接制样法 2.10硫酸盐的硫同位素制样法(直接还原法) 把硫酸盐、氧化铜、石英粉按一定比例混合(置于石英管中)在真空条件下加热到1120 ℃左右时,硫酸盐被还原而转变成二氧化硫。 2.11 了解下列质谱仪

矿物岩石地球化学通报 ·综 述· Bulletin of Mineralogy,Petrology and GeochemistryVol.32No.1,Jan.,2013 收稿日期:2011-12-01收到,2012-03- 05改回基金项目:中国科学院知识创新工程重要方向项目(KZCX2-EW- 102);中国科学院地球化学研究所领域前沿项目第一作者简介:范百龄(1986-),男,博士研究生,主要从事同位素地球化学方面的研究.E-mai:fbl860726@126.com.通讯作者:赵志琦(1971-),博士,研究员,研究方向:水岩作用过程的硼、锂同位素地球化学研究.E-mail:zhaozhiqi@vip.skleg .cn.地表及海洋环境的镁同位素地球化学研究进展 范百龄1, 2 ,陶发祥1,赵志琦11.中国科学院地球化学研究所环境地球化学国家重点实验室,贵阳550002;2.中国科学院大学,北京100039摘 要:镁(Mg)是主要造岩元素,其地球丰度仅次于铁和氧。Mg几乎参与了地表所有圈层间的物理、化学和生物作用。随着多接收器等离子质谱等分析方法的改进和完善,Mg同位素显示出更加广阔的应用前景。同时,Mg独特的地球化学特征,使其在地表及海洋地球化学领域的应用日益广泛。本文主要就近几十年来Mg同位素在地表及海洋地球化学领域的研究现状、存在的问题以及发展趋势进行系统的总结与探讨。虽然,目前对Mg同位素的研究还处于早期阶段,但许多研究成果显示,Mg同位素具有很大潜力成为环境变化的新的指示工具。关 键 词:进展;Mg同位素; 地球化学;海洋和地表过程中图分类号:P595 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1007-2802(2013)01-0114- 07Advance of Geochemical Applications of Magnesium Isotop e in Marineand Earth Surface EnvironmentsFAN Bai-ling1, 2,TAO Fa-xiang1, ZHAO Zhi-qi 1 1.State key laboratory of Environmental Geochemistry,Institute of Geochemistry,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Guiyang550002,China;2.Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing100039,ChinaAbstract:Magnesium,whose Earth abundance is in the third place only after oxygen and iron,is one of the majorrock-forming elements.Magnesium takes a part in,almost,all geochemical,physical and biological processes ofdifferent spheres.Given rapid improving of analytical method of the multiple collector-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry(MC-ICPMS),Mg isotope will be used in a broad range of geochemical applications in the nearfuture.Due to its distinct geochemical characteristics,Mg has been successfully demonstrating wider applicationperspectives in Marine and Earth Surface Environments.This paper reviews the recent progress of Mg stable iso-tope studies.In addition,existing problems and development tendency are also discussed.Regardless of its earlystage,the most recent researches have shown that Mg isotopes are potential indicators of environmental changes.Key words:advances;Magnesium isotopes;geochemistry;Marine and Earth Surface processes 作为生物营养元素的镁(Mg ),是地球上的常量元素,其地球丰度(1.6×105 mg/kg )仅次于铁和氧,Mg的克拉克值在2.4×104 mg/kg(陆壳)~4.3×104 mg/kg(洋壳)之间[1]。自然界Mg主要以硅酸 盐形式存在,主要矿物有橄榄石、辉石、角闪石,云母等,也是白云岩的主要组成元素,并广泛参与生命活 动。Mg有三种稳定同位素:24 Mg、25 Mg、26 Mg ,相对丰度分别为78.99%、10.00%、11.01% [2,3] ,三者 的质量差达4%~8%,是相对质量差仅次于Li的 第二大非传统稳定同位素,低温地球化学过程会产 生明显的同位素分馏[ 4,5] 。目前报道的地球样品Mg同位素组成的变化范围约6. 5‰(图1),天然样品的Mg同位素组成与其所经历的地球化学过程密切相关,受不同分馏机理的控制。Mg同位素作为 新的化学示踪剂, 已被用来探索宇宙事件[6~8] ,示踪古海洋环境[9,10],研究风化作用[11~13] 、石笋的形

水文地球化学习题 第一章 第二章水溶液的物理化学基础 1.常规水质分析给出的某个水样的分析结果如下(浓度单位:mg/L): Ca2+=93.9;Mg2+=22.9;Na+=19.1;HCO3-=334;SO42-=85.0;Cl-=9.0;pH=7.2。求: (1)各离子的体积摩尔浓度(M)、质量摩尔浓度(m)和毫克当量浓度(meq/L)。 (2)该水样的离子强度是多少? (3)利用扩展的Debye-Huckel方程计算Ca2+和HCO3-的活度系数。 2.假定CO32-的活度为a CO32- =0.34?10-5,碳酸钙离解的平衡常数为4.27?10-9,第1题中的水样25℃时CaCO3饱和指数是多少?CaCO3在该水样中的饱和状态如何? 3.假定某个水样的离子活度等于浓度,其NO3-,HS-,SO42-和NH4+都等于10-4M。反应式如下: H+ + NO3- + HS- = SO42- + NH4+ 问:25℃和pH为8时,该水样中硝酸盐能否氧化硫化物? 4.A、B两个水样实测值如下(mg/L): 组分Ca2+Mg2+Cl-SO42-HCO3-NO3- A水样706 51 881 310 204 4 5.请判断下列分析结果(mg/L)的可靠性,并说明原因。 组分Na+K+Ca2+Mg2+Cl-SO42-HCO3-CO32-pH A水样50 6 60 18 71 96 183 6 6.5 B水样10 20 70 13 36 48 214 4 8.8 6.某水样分析结果如下: 离子Na+Ca2+Mg2+SO42-Cl-CO32-HCO3-含量(mg/l) 8748 156 228 928 6720 336 1.320 试计算Ca2+的活度(25℃)。 4344 含量(mg/l)117 7 109 24 171 238 183 48 试问: (1)离子强度是多少? (2)根据扩展的Debye-Huckel方程计算,Ca2+和SO42-的活度系数? (3)石膏的饱和指数与饱和率是多少? (4)使该水样淡化或浓集多少倍才能使之与石膏处于平衡状态? 8.已知温度为298.15K(25℃),压力为105Pa(1atm)时,∑S=10-1mol/l。试作硫体系的Eh-pH图(或pE-pH图)。 9.简述水分子的结构。 10.试用水分子结构理论解释水的物理化学性质。 11.温、压条件对水的物理、化学性质的影响及其地球化学意义。 12.分别简述气、固、液体的溶解特点。

第四章同位素水文地球化学 环境同位素水文地球化学是一门具有良好的前景、发展迅速的新兴学科,也是水文地球化学的一个重要分支。目前,地下水资源可持续利用中的重要问题是地下水补给的更新能力及地下水污染程度的评价。用环境同位素技术研究地下水补给和可更新性,追踪地下水的污染是当前国内外较为新颖的方法之一。目前世界上许多国家已将同位素方法列为地下水资源调查中的常规方法。近年来,国内外环境同位素的研究从理论到实践都有较快的发展。除了应用氢氧稳定同位素确定地下水的起源与形成条件,应用氚、14C测定地下水年龄,追踪地下水运动,确定含水层参数等常规方法外;在应用3H-3He、CFCs示踪干旱、半干旱地区浅层地下水的补给,应用14C、36Cl确定深层地下水的年龄,追溯地下水的入渗史,应用34S研究地下水中硫酸盐的来源,分析地下水的迁移过程,应用11B/10B研究卤水成因等方面都有重要进展。 4.1 同位素基本理论 4.1.1 地下水中的同位素及分类 我们知道,原子是由原子核与其周围的电子组成的,通常用A Z X N来表示某一原子。这里,X为原子符号,Z为原子核中的质子数目,N为原子核中的中子数目,A为原子核的质量数,它等于原子核中的质子数与中子数之和,即: A=Z+N( 4-1-1 ) 为简便起见,也常用A X表示某一原子。 元素是原子核中质子数相同的一类原子的总称。同一元素由于其原子核中中子数不同可存在几种原子质量不同的原子,其中每一种原子称为一种核素,如C原子有12C、13C、14C等核素,氧原子有16O、17O、18O等核素。某元素的不同几种核素称为该元素的同位素(蔡炳新等,2002),或者说同位素指的是在门捷列耶夫周期表中占有同一位置,其原子核中的质子数相同而中子数不同的某一元素的不同原子。同位素可分为稳定同位素和放射性同位素两类,稳定同位素是指迄今为止尚未发现有放射性衰变(即自发地放出粒子或射线)的同位素;反之,则称为放射性同位素。 地下水中的同位素一方面包括水自身的氢、氧同位素,另一方面还包括水中溶质的同位素。

同位素地球化学研究进展

1 概述 同位素研究是地质学的重要研究手段之一,可以视之为科学研究史上的革命,它的发展极大地加速了许多科学研究进程。同位素地质应用是同位素地球化学的重要组成部分。随着放射性现象的发现,同位素的分析逐渐被建立为独立的研究领域。作为独特的示踪剂和形成环境与条件的指标,同位素组成已广泛的应用到陨石、月岩、火成岩、沉积岩、变质岩、大气、生物以及各种矿床等领域的研究。通过研究同位素在地质体的分布及在各种地质条件下的运动规律来研究矿物、岩石和矿床等各个领域,成为解决众多地质地球化学问题的强有力手段。 地球的历史是一个由大量地质事件构成的漫长的时间序列,它具有灾变和渐变相间的特点。我们在认识这一复杂的过程时,主要依据能保留事件踪迹的证据。同位素的迁移活动寓于地质作用之中,地质事件对地球的影响有可能跨越后期作用而被保存下来,因此同位素组成上的变异常常能提供最接近事实的证据,并且相关研究也用一系列显著成绩证实了这点。 1.1 同位素地球化学的发展现状 同位素的丰度和分布的研究正经历着飞跃性的发展。在不到一百年的时间里,已经取得了非凡的成果,解决了一系列重要的问题,如南非南德斯金矿的成因问题。此外,随着大量的数据和文章的面世,理论基础的不断完善,实验技术的不断发展,同位素地球化学迄今为止仍在快速的发展着,并不断与其他学科相互渗透形成新的学科分支,如宇宙同位素地球化学、环境同位素地球化学等。因此,同位素地球化学已非局限于研究地球及其地质现象,而是扩展到了太阳系的其他星体和其他科学领域。显然,地质学已到了一个新的时期,即同位素地质学时期。 1.2 同位素概念 1913年,Soddy提出了同位素概念,即原子内质子数相同而中子数不同的一类原子即为同位素。一个原子可以有一种或多种同位素。有的元素仅有稳定同位素(如O、S),稳定同位素的原子核是稳定的,目前还未发现他们能自发衰变形成其他的同位素。有的仅有放射性同位素(如U、Th)。放射性同位素原子核是不稳定的,他们能自发的衰变形成其他的同位素,最终转变为稳定的放射成因同

本文由国土资源部地质调查项目“全国水资源评价”和“鄂尔多斯自留盆地地下水赋存运移规律的研究”项目资助。改回日期:2001212217;责任编辑:宫月萱。 第一作者:叶思源,女,1963年生,在读博士生,副研究员,从事矿水、地热水及水文地球化学研究。 水文地球化学研究现状与进展 叶思源1) 孙继朝2) 姜春永3) (1)中国矿业大学,北京,100083;2)中国地质科学院水文地质环境地质研究所,河北正定,050803; 3)山东地质工程勘查院,山东济南,250014) 摘 要 1938年,“水文地球化学”术语提出,至今水文地球化学作为一门独立的学科得到长足的发展,其服务领域不断扩大。当今水文地球化学研究的理论已经广泛地应用在油田水、海洋水、地热水、地下水质与地方病以及地下水微生物等诸多领域的研究。其研究方法也日臻完善。随着化学热力学和化学动力学方法及同位素方法的深入研究,以及人类开发资源和保护生态的需要,水文地球化学必将在多学科的交叉和渗透中拓展研究领域,并在基础理论及定量化研究方面取得新的进展。关键词 水文地球化学 研究现状 进展 Current Situ ation and Advances in H ydrogeochemical R esearches YE Siyuan 1) SUN Jichao 2) J IAN G Chunyong 3 ) (1)Chi na U niversity of Mi ni ng and Technology ,Beiji ng ,100083;2)Instit ute of Hydrogeology and Envi ronmental Geology ,CA GS , Zhengdi ng ,Hebei ,050803;3)S handong Instit ute of Geological Engi neeri ng S urvey ,Ji nan ,S handong ,240014) Abstract Hydrogeochemistry ,as an independent discipline ,has made substantial development since the term “hydrogeochemistry ”was created in 1938.At present hydrogeochemical theories have been applied to various fields such as oil field water ,ocean water ,geothermal water ,groundwater quality ,endemic diseases and groundwater microorganism ,and related research methods have also become mature.With the further development of chemical thermodynamics ,kinetics method and isotope method ,hydrogeochemistry will surely extend its research fields in the course of multi 2discipline interaction and make new progress in basic theory and quantifica 2tion research ,so as to meet the demand of human exploration and exploitation as well as ecological protection.K ey w ords hydrogeochemistry current state of research advance 早期的水文地球化学工作主要围绕查明区域水文地质条件而展开,在地下水的勘探开发利用方面取得了可喜的成果(沈照理,1985)。水文地球化学在利用地下水化学成分资料,特别是在查明地下水的补给、迳流与排泄条件及阐明地下水成因与资源的性质上卓有成效。20世纪60年代后,水文地球化学向更深更广的领域延伸,更多地是注重地下水在地壳层中所起的地球化学作用(任福弘,1993)。1981年,Stumm W 等出版了《水化学———天然水化 学平衡导论》专著,较系统地提供了定量处理天然水环境中各种化学过程的方法。1992年,C P 克拉 依诺夫等著《水文地球化学》分为理论水文地球化学及应用水文地球化学两部分,全面论述了地下水地球化学成分的形成、迁移及化学热力学引入水文地球化学研究的理论问题,以及水文地球化学在饮用水、矿水、地下热水、工业原料水、找矿、地震预报、防止地下水污染、水文地球化学预测及模拟中的应用等,概括了20世纪80年代末期水文地球化学的研究水平。特别是近二十年来计算机科学的飞速发展使得水文地球化学研究中的一些非线性问题得到解 答(谭凯旋,1998),逐渐构架起更为严密的科学体系。 第23卷 第5期2002210/4772482 地 球 学 报ACTA GEOSCIEN TIA SIN ICA Vol.23 No.5 Oct.2002/4772482

同位素地球化学

目录 一、碳的同位素组成及其特征 (1) 1.碳同位素组成 (1) Ⅰ、碳的同位素丰度 (1) Ⅱ、碳的同位素比值(R) (1) Ⅲ、δ值 (2) 2.碳同位素组成的特征 (2) Ⅰ.交换平衡分馏 (2) Ⅱ.动力分馏 (3) Ⅲ.地质体中碳同位素组成特征 (3) 二、碳同位素在地质科学研究中的应用 (8) 1. 碳同位素地温计 (8) 2.有机矿产的分类对比及其性质的确定 (9) Ⅰ.煤 (9) Ⅱ.石油 (9) Ⅲ. 天然气 (11)

碳同位素组成特征及其在地质科研中的应用 一、碳的同位素组成及其特征 1.碳同位素组成 碳在地球上是作为一种微量元素出现的,但分布广泛,在地质历史中有着重要作用。碳的原子序数为6 ,原子量为12.011,属元素周期表第二周期ⅣA族。碳在地壳中的丰度为2000×10-6,是一个比较次要的微量元素。在地球表面的大气圈、生物圈和水圈中,碳是最常见的元素之一,是地球上各种生命物质的基本成分馏。碳既可以呈固态形式存在,又能以液态和气态形式出现。它既广泛分馏布于地球表面的各层圈中,也能在地壳甚至地幔中存在。总之,碳可呈多种形式存在于自然界中。在有机物质和煤、石油中,以还原碳的形式存在,在二氧化碳气体和水溶液中,以氧化碳形式出现。碳还可呈自然元素形式出现在某些岩石中(如金刚石和石墨)。一般用同位素丰度、同位素比值和δ值来表示同位素的组成。 Ⅰ、碳的同位素丰度 同位素丰度指同位素原子在元素总原子数中所占的百分比,自然界中的碳有2个稳定同位素:12C和13C。习惯采用的平均丰度值分别为98.90%和1.10%。由此可见,在自然界中碳原子主要主要是以12C的形式存在。另外碳还有一个放射性同位素14C,半衰期为5730a。放射性14C的研究,目前已发展成为一种独立的同位素地质年代学测定方法,主要应用于考古学和近代沉积物的年龄测定。适合用于作碳稳定同位素分馏析的样品包括:石墨、金刚石等自然碳矿物,方解石、文石、白云石、菱铁矿、菱锰矿等碳酸盐矿物;石灰岩、白云岩、大理岩等全岩样品;各种矿物包裹体中的C O2和CH4气体以及石油、天然气及有机物质中的含碳组分馏等。 Ⅱ、碳的同位素比值(R) 同位素比值R=一种同位素丰度/另一种同位素丰度 对于非放射性成因稳定同位素比值: R=重同位素丰度/轻同位素丰度 由此可见,碳的同位素比值R=1.1%/98.9%=0.011

S TABLE I SOTOPES IN P ALEONTOLOGY AND A RCHEOLOGY I NTRODUCTION The isotopic composition of a given element in living tissue depends on: (1) the source of that ele-ment (e.g., atmospheric CO2 versus dissolved CO2; seawater O2 vs. meteoric water O2), (2) the proc-esses involved in initially fixing the element in organic matter (e.g., C3vs. C4photosynthesis), (3) subsequent fractionations as the organic matter passes up the food web. Besides these factors, the iso-topic composition of fossil material will depend on any isotopic changes associated with diagenesis, including microbial decomposition. In this lecture, we will see how this may be inverted to provide insights into the food sources of fossil organisms, including man. This, in turn, provides evidence about the environment in which these organisms lived. I SOTOPES AND D IET: Y OU ARE WHAT YOU EAT In Lecture 28 we saw that isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen are fractionated during primary pro-duction of organic matter. Terrestrial C3 plants have d13C values between -23 and -34‰, with an av-erage of about -27‰. The C4 pathway involves a much smaller fractionation, so that C4 plants have d13C between -9 and -17‰, with an average of about -13‰. Marine plants, which are all C3, can util-ize dissolved bicarbonate as well as dissolved CO2. Seawater bicarbonate is about 8.5‰ heavier than atmospheric CO2; as a result, marine plants average about 7.5‰ heavier than terrestrial C3 plants. In contrast to the relatively (but not perfectly) uniform isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2, the carbon isotopic composition of seawater carbonate varies due to biological processes. Because the source of the carbon they fix is more variable, the isotopic composition of marine plants is also more variable. Finally, marine cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) tend to fractionate carbon isotopes less during photosynthesis than do true marine plants, so they tend to average 2 to 3 ‰ higher in d13C. Nitrogen isotopes are, as we saw, also fractionated during primary uptake. Based on their source of nitrogen, plants may also be divided into two types: those that can utilized N2directly, and those utilize only “fixed” nitrogen as ammonia and nitrate. The former include the legumes (e.g., beans, peas, etc.) and marine cyanobac-teria. The legumes, which are exclusively C3 plants, utilize both N2 and fixed nitrogen (though symbiotic bacteria), and have an average d15N of +1‰, whereas modern non-leguminous plants average about +3‰. However, it seems likely that prehistoric nonleguminous plants were more positive, averaging perhaps +9‰, because the iso-topic composition of present soil nitrogen has been affected by the use of chemical fer-tilizers. For both groups, there was proba-bly a range in d15N of ±4 or 5‰, because the isotopic composition of soil nitrogen varies and there is some fractionation involved in uptake. Marine plants have d15N of +7±5‰, whereas marine cyanobacteria have d15N of –1±3‰. Figure 34.1 summarizes the 15 10 5 --5 d13C PDB ‰ d15N ATM ‰ Figure 34.1. Relationship between d13C and d15N among the principal classes of autotrophs.

地幔流体的稳定同位素地球化学综述 王先彬 吴茂炳张铭杰 (中国科学院兰州地质研究所,兰州,730000) 摘 要 总结了20年来国内外学者对地幔流体研究的成果和认识。主要包括地幔流体的性质和组成; 地幔 流体中同位素的含量、组成和赋存形式;同位素分馏和地幔脱气等作用对地幔组分的影响等。在不同地区和不同构造环境条件的地幔流体中,各种组分含量和同位素组成变化可以很大,从一个侧面指示地幔组分的不均一性,反映了不同地幔物质的形成历程不同或来自不同的地幔源区。此外,还讨论了目前存在的几个疑点。 关键词 地幔流体 稳定同位素地球化学 同位素分馏 地幔脱气作用 地幔源 第一作者简介 王先彬 男 1941年出生 研究员 主要从事稀有气体地球化学、非生物成因天然气及同位素地球化学等领域的研究工作 随着高精度探测技术的出现和地球科学知识的积累,人们对地球的认识进入到更深的层次。从传统的地壳到壳-幔作用,近几年来又深入到核-幔边界以至对地核的认识[1],使得对地球深部物质的研究与深部地球物理和地球化学进一步结合成为可能,并为提出全面统一的地球演化动力理论和模式准备了条件。地幔流体的研究是了解地球深部的重要手段之一。本文就地幔流体中稳定同位素方面的近期研究进展作一综述。 1 地幔流体的性质 作为地球内部的一种重要介质流体,是研究地球深部地质作用、了解深部物质的物理化学环境乃至地球发展演化的重要组分,其重要性愈来愈被更多的人所认识,是近20年来地学研究的热点。 流体,在地球科学研究中,常常是挥发组分的液相、气相及其超临界相以及硅酸盐熔体的统称,但在许多情况下不包括硅酸盐熔体。因此,地幔流体是指在地幔条件下(物相、温度、压力和氧逸度等)处于平衡并稳定共存的挥发组分[2],其形成温度大约在900℃至1400℃之间,其化学组成不均一,受多种因素控制,一般地以C、H、O、N和S(CHONS)为主要化学组分并以含较高的氢为特征,且含微量的稀有气体、F、P、Cl等。地幔挥发 1999年11月2日收稿,12月8日改回。份具有与地幔高p-t条件相适应的物理化学特性(如高的气体密度等),其地球化学性质以易溶于硅酸盐熔体(特别是富碱硅酸盐熔体)为特征,促进低熔点并且饱和挥发份的高钾原始岩浆和地幔交代熔体的形成,同时对于微量元素有高的溶解度(如大离子半径亲石元素、高价阳离子和稀土元素等),并且具有使溶质及各种微量元素产生再沉淀作用(如地幔交代作用导致地幔富集事件)。地幔流体的性质决定了它是地球内部能量和质量传输最活跃的组分,它控制着地幔岩浆作用、交代作用以及地幔变质变形等地质、地球化学作用的发生和发展,是对地球形成、发展和演化起重要作用的组分,具有重要的研究意义。 2 地幔流体的稳定同位素地球化学研究进展 自R oedder(1965)观察到全球碱性玄武岩的超镁铁质捕虏体中均找到CO2包裹体以来,地幔流体的研究工作陆续展开。许多学者采用各种测试方法(如电子探针、离子探针、激光拉曼探针、质谱计等)对认为是来自地幔的岩石矿物样品(如金刚石、金伯利岩、碳酸岩、大洋玄武岩、地幔包体等)进行了包裹体挥发组分及熔体主要元素的测定,发现不同地区、不同环境条件的地幔流体中各组分的含量变化很大,从一个侧面指示了地幔组分的不均一性。 96 2000年第28卷第3期Vol.28,No.3,2000 地 质 地 球 化 学 GEOLO GY2GEOCHEMISTR Y

复习题与思考题 1. 名词解释 (1)阳离子交换容量; (2)弥散通量; (3)水文地球化学; (4)水动力弥散; (5)弥散问题数学模型;(6)大陆效应;地下水污染;(7)碱度; (8)酸度; (9)硬度; (10)永久硬度; (11)暂时硬度; (12)碳酸盐硬度; (13)非碳酸盐硬度; (14)生化耗氧量(BOD);(15)化学耗氧量(COD)(16)物理吸附; (17)化学吸附; (18)离子交替吸附作用;(19)阳离子交换容量; (20)同位素效应; (21)同位素分馏; (22)同位素交换反应;(23)射性同位素的半衰期;(24) TDS; (25)全等溶解; (26)非全等溶解;

2.思考并回答下列问题 绪论 (1)试说明水文地球化学的含义。 (2)试说明水文地球化学作为一个独立学科的发展历史。 (3)说明水文地球化学的研究意义。 第一章地下水的化学成分 (1)试说明水的结构特征。 (2)水有那些特异性质,试分别对其予以说明。 (3)地下水的化学成分有那几类,分别予以简要说明。 (4)通常有哪些方法可用来对水质分析结果进行检验? (5)地下水化学成分的图示方法有哪些?试分别予以简要说明。 第二章地下水化学成分的形成作用 (1)怎样根据化学反应的自由能资料计算反应的平衡常数? (2)水溶液中组分活度系数的计算方法主要有哪些?试说明其适用条件。 (3)试说明影响矿物在水中溶解度的因素。 (4)试分别说明纯水中石膏、萤石、石英、三水铝石溶解度的计算方法。 (5)试说明矿物稳定场图的绘制方法。 (6)试定性地说明为什么在CO2-H2O系统中水溶液显酸性,而在CaCO3-H2O系统中水溶液显碱性。 (7)已知H2CO3的一、二级电离常数分别为K a1和K a2,试导出CO2──H2O系统中:溶解碳总量为C T、氢离子浓度为[H+]时,H2CO3、HCO3-和CO32-含量的计算公式。若25℃时,K a1=10-6.35、K a2=10-10.33,试分析说明上述组分中那一种组分在什么样的pH区间内含量最大? (8)在CO2分压(p)已知的CO2—H2O系统中,已知下述反应的平衡常数分别为CO2分压为10-3.5(atm),水的离子积为10-14,且上述反应均已达到平衡状态。试计算系统中各组分存在形式的含量及水溶液的pH值。 (9)对于下述的电极反应: OX+n e = RED 已知其电极电位可由下式计算: 式中:F为法拉第常数;R为气体常数;n为得失电子地数目;E0为标准电极电位,E0的计算