Managing the km trade-off Knowledge Centralization versus distribution

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:86.92 KB

- 文档页数:14

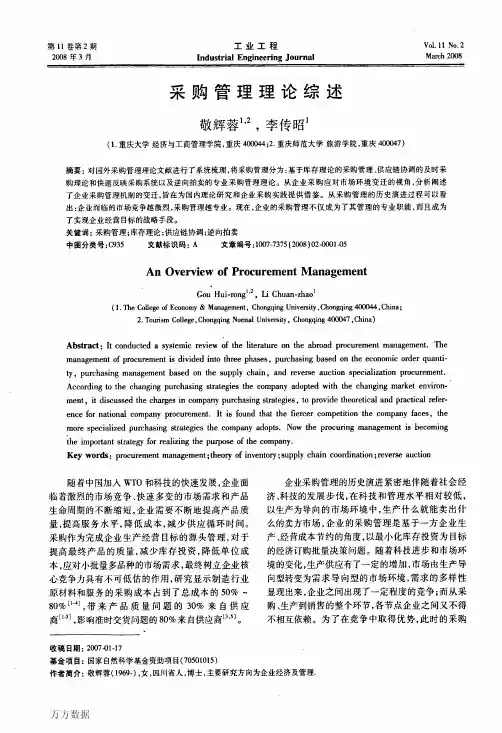

采购管理理论综述作者:敬辉蓉, 李传昭, Gou Hui-rong, Li Chuan-zhao作者单位:敬辉蓉,Gou Hui-rong(重庆大学经济与工商管理学院,重庆400044;重庆师范大学旅游学院,重庆400047), 李传昭,Li Chuan-zhao(重庆大学经济与工商管理学院,重庆,400044)刊名:工业工程英文刊名:INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING JOURNAL年,卷(期):2008,11(2)被引用次数:3次1.Harris F W Operations and Cost-factory management series 19152.Inman R A Quality certification of suppliers by JIT manufacturers 1990(02)3.Jahnukainen J;Lahti M Efficient purchasing in make-to-order supply chains[外文期刊] 1999(59)4.Fiorito Susan S;Giunipero Larry C;He Yan Retail buyers' perceptions of quick response systems 1998(06)5.Wu Min;Low SOi Pheng Economic order quantity (EOQ)versus just-in-time (JIT) purchasing:an ahemative analysis in the ready-mixed concrete industry[外文期刊] 2005(23)6.Niall Waters-Fuller Just-in-time purchasing and supply:a review of the literature 1995(09)7.Ganesh lyer;J Miguel Villas-Boas A bargaining Theory of distribution channels 2003(XI)8.Weng Z Kevin Channel coordination and quantity discounts 1995(09)9.thing-Hua;Chen-Ritzo;Terry P Harrison Better,faster,cheaper:an experimental analysis of a multiattribute reverse auction mechanism with restricted infor mation feedback[外文期刊] 2005(12)10.Leandro Arezamena;Estelle Cantillon Investment ineenfives in procurement auctions 2004(71)11.David C Parkes;Jayant Kalagnanam Model for iterative multi-attribute procurement auctions[外文期刊] 2005(03)12.Yossi Sheffi Combinatorial auctions in the procurement of transportation services[外文期刊] 2004(04)13.Rachel R Chen;Robin O Roundy;Rachel Q Zhang Efficient auction mechanisms for supply chain procurement[外文期刊] 2005(03)14.Hariga M;Haouari M An EOQ lot sizing model with random supplier capacity[外文期刊] 1999(01)15.Silver E A;Pyke D F;Peterson R Inventory management and production planning and scheduling 199816.Khouja M The single period (news-vendor) inventory problem:a literature review and suggestions for future research 1999(27)17.Willis T;Hnston C Vendor requirements and evualation in a JIT environment 1990(04)18.Naumann E;Reck R A buyer's bases of power 1982(04)19.Alan Smart;Alan Harrison Reverse auctions as a support mechanism in flexible supply chain2002(03)20.John G Riley;William F Samuelson Optimal auction 1981(71)21.Roger B Myerson Optimal auction design[外文期刊] 1981(06)22.Vickrey,William Counterspeculation,auctions,and competitive sealed tenders 1961(16)23.Yen Benjamin P-C;Ng Elsie O S The impact of electronic commerce on procurement[外文期刊] 2003(3-4)24.Monaban J P A quantity discount pricing model to increase vendor profits 1984(30)25.Susan A Shaw;Juliette Gibbs Procurement strategies of small retailers faced with uncertainty:an analysis of channel choice and behavior[外文期刊] 1999(01)26.Robert A Novack;Stephen W Simco The industrial procurement process:a supply chain perspective 1991(01)27.Dr David R Rink;Dr Harold W Fox Using the product life cycle concept to formulate actionable purchasing strategies 2003(02)28.Hammer Michael;Champy James Reengineering the corporation,a manifesto for business revolution 199329.Sridhar K Moorthy Managing channel profits:comment 1987(04)30.Jeuland A;Shugan S Managing channel profits 1983(02)31.James M Wilson A simulation analysis of ordering policies under inflationary conditions:a critique 1995(08)32.Wirth Andrew Technical paper:inventory control and inflation:a review 1989(01)33.Chang P L;Lin C T On the effect of centralization of the expected costs in a multi-location newsboy problem 1991(42)u A;Lau H The newsstand problem:a capaeitated multiproduct single period inventory problem 1996(94)35.Gullu R;Onol E;Erkip N Analysis of an inventory system under supply uncertainty 1999(59)36.Burton T T JIT/repetitive sourcing strategies:tying the knot with your suppiers 1988(04)1.周虹基于Web Services的物资采购管理系统的研究与应用[期刊论文]-中国科技信息 2010(21)2.王正武.黄巍物资信息的流转模式浅析[期刊论文]-兵工自动化 2009(2)3.周永宏绿色供应链条件下的企业采购管理[期刊论文]-科技资讯 2008(20)本文链接:/Periodical_gygc200802001.aspx。

第27卷第11期2021年11月计算机集成制造系统Vol.27No.11 Computer Integrated Manufacturing Systems Nov.2021DOI:10.13196/j.cims.2021.11.016基于Kriging模型的自适应多阶段并行代理优化算法乐春宇,马义中+(南京理工大学经济管理学院,江苏南京210094)摘要:为了充分利用计算资源,减少迭代次数,提出一种可以批量加点的代理优化算法。

该算法分别采用期望改进准则和WB2(Watson and Barnes)准则探索存在的最优解并开发已存在最优解的区域,利用可行性概率和多目标优化框架刻画约束边界。

在探索和开发阶段,设计了两种对应的多点填充算法,并根据新样本点和已知样本点的距离关系,设计了两个阶段的自适应切换策略。

通过3个不同类型算例和一个工程实例验证算法性能,结果表明,该算法收敛更快,其结果具有较好的精确性和稳健性。

关键词:Kriging模型;代理优化;加点准则;可行性概率;多点填充中图分类号:O212.6文献标识码:AParallel surrogate-based optimization algorithm based on Kriging model usingadaptive multi-phases strategyYUE Chunyu,MA Yizhong+(School o£Economics and Management,Nanjing University of Science and Technology,Nanjing210094,China) Abstract:To make full use of computing resources and reduce the number of iterations,a surrogate-based optimization algorithm which could add batch points was proposed.To explore the optimum solution and to exploit its area, the expected improvement and the WB2criterion were used correspondingly.The constraint boundary was characterized by using the probability of feasibility and the multi-objective optimization framework.Two corresponding multi-points infilling algorithms were designed in the exploration and exploitation phases and an adaptive switching strategy for this two phases was designed according to the distance between new sample points and known sample points.The performance of the algorithm was verified by three different types of numerical and one engineering benchmarks.The results showed that the proposed algorithm was more efficient in convergence and the solution was more precise and robust.Keywords:Kriging model;surrogate-based optimization;infill sampling criteria;probabil让y of feasibility;multipoints infill0引言现代工程优化设计中,常采用高精度仿真模型获取数据,如有限元分析和流体动力学等E,如何在优化过程中尽可能少地调用高精度仿真模型,以提高优化效率,显得尤为重要。

Sept 2021Vol. 42 No. 92021年9月 第42卷第9期计算机工程与设计COMPUTER ENGINEERING AND DESIGN考虑动态拥堵的多车型绿色车辆路径问题优化狄卫民,杜慧莉+,张鹏阁(郑州大学管理工程学院,河南郑州450001)摘 要:为降低物流配送成本,促进碳减排,提出一种考虑动态拥堵的多车型绿色车辆路径优化方法。

针对常发性道路拥堵状况,将配送时间划分为若干时段,以道路拥堵系数反映不同时段的拥堵状况,同时考虑到碳排放、多车型和客户时间 窗的影响,建立以系统总成本最小为目标的绿色车辆路径优化模型,设计求解模型的头脑风暴优化算法。

结合算例,对该问题进行仿真,将结果与遗传算法进行对比,验证了模型的可行性和算法的有效性,表明考虑多车型配送和动态拥堵可以有效降低系统成本。

关键词:绿色车辆路径问题;动态拥堵;碳排放;多车型;头脑风暴优化算法中图法分类号:TP391. 9 文献标识号:A 文章编号:1000-7024 (2021) 09-2614-07doi : 10.16208/j. issnl000-7024. 2021. 09. 028Optimization of multi-vehicle green vehicle routing problemconsidering dynamic congestionDI Wei-min, DU Hui-li + , ZHANG Peng-ge(School of Management Engineering, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, China)Abstract : To reduce logistics distribution cost and promote carbon reduction, an optimization method for multi-vehicle green vehicle routing problem considering dynamic congestion was proposed. Aiming at frequent road congestion conditions? thedelivery time was divided into several time periods, and the road congestion coefficient was used to reflect the congestion condi tions at different time periods. Considering the impact of carbon emission, multi-vehicle types and customer time windows simul taneously? a green vehicle routing optimization model with the goal of minimizing the total system cost was established and abrain storm optimization algorithm was designed. This problem was simulated with a calculation example? and the result was compared with genetic algorithm to demonstrate the feasibility of the model and the effectiveness o£ the algorithm. The deductionis obtained simultaneously considering multi-vehicle distribution and dynamic congestion can reduce system cost effectively.Key words : green vehicle routing problem ; dynamic congestion; carbon emission; multi-vehicle; brain storm optimization algo rithm0引言在规划配送车辆路线时,既要追求经济目标,又要注重环境影响E,因此,绿色车辆路径问题(green vehiclerouting problem, GVRP )引起了学者们的关注。

第21卷第4期2023年12月交通运输工程与信息学报Journal of Transportation Engineering and InformationVol.21No.4Dec.2023文章编号:1672-4747(2023)04-0103-12融合多源数据与元胞传输模型的高速公路交通状态估计方法易术*,黄丹阳(四川智能交通系统管理有限责任公司,成都610200)摘要:针对高速公路管控和决策应对交通状态进行准确、可靠和精细化估计的需求,本文提出了一种基于多源数据+元胞传输模型(Multi-Source Data Cell Transmission Model,MD-CTM)的交通状态估计方法。

该方法针对传统CTM模型要求元胞长度必须一致的局限性,提出了一种元胞长度划分的优化方法,能够灵活调整元胞长度和数量。

同时,应用卡尔曼滤波技术,将ETC门架流量、稀疏视频检测器流量和样本车辆平均速度数据融合,并与CTM模型相结合,实现高速公路元胞级交通状态估计。

为了验证本文提出方法的有效性和准确性,我们利用VISSIM软件构建了长度5km的高速公路仿真场景。

仿真案例结果表明,本文提出的MD-CTM模型能够较为准确地反映不同流量需求下交通流状态的时空演化特征,且相较于CTM模型,其元胞密度估计精度提高12.59%~36.26%。

此外,本文选取了成都市绕城高速路段实际场景,对模型的运行效果进行了展示。

关键词:智能交通;交通状态估计;卡尔曼滤波;元胞传输模型;多源数据融合中图分类号:U495文献标志码:A DOI:10.19961/ki.1672-4747.2023.08.001Freeway traffic state estimation based on multi-source data andcell transmission modelYI Shu*,HUANG Dan-yang(Sichuan Intelligent Transport System Management Co.,Ltd.,Chengdu610200,China)Abstract:Accurate,reliable,and efficient traffic state estimation is essential for effective freeway management and decision-making.This study presents a traffic state estimation method called MD-CTM,which combines multi-source data and the cell transmission model(CTM).As the traditional CTM has limitations owing to fixed cell lengths,we propose a cell division approach that allows for flexible lengths and numbers.To enhance the accuracy of traffic state estimation,we utilize the Kal-man filtering technique to fuse different types of traffic data,including traffic flow from the electron-ic toll collection system and sparse video detectors,and an average link speed with the CTM to achieve cell-level traffic state estimation on freeways.To evaluate the performance of the proposed approach,we conducted simulations using VISSIM on a freeway section of5km.The simulation re-sults show that the proposed MD-CTM model improves the accuracy of cell density estimation by12.59%~36.26%compared with the CTM model.Furthermore,our model effectively captures thespatio-temporal evolution characteristics of traffic flow states under different traffic demand condi-收稿日期:2023-08-07录用日期:2023-08-25网络首发:2023-09-12审稿日期:2023-08-07~2023-08-09;2023-08-17~2023-08-25基金项目:国家重点研发计划项目(2021YFB1600100)作者简介:黄丹阳(1988—),男,硕士,高级工程师,研究方向为交通智能控制、内模与预测控制,E-mail:****************通信作者:易术(1970—),男,硕士,高级工程师,研究方向为交通工程、智慧交通,E-mail:****************引文格式:易术,黄丹阳.融合多源数据与元胞传输模型的高速公路交通状态估计方法[J].交通运输工程与信息学报,2023,21(4):103-114.YI Shu,HUANG Dan-yang.Freeway traffic state estimation based on multi-source data and cell transmission model[J].Journal of Transportation Engineering and Information,2023,21(4):103-114.104交通运输工程与信息学报第21卷tions.Moreover,a real-world scenario of Chengdu city is used to further demonstrate the effective-ness of our proposed approach.Key words:intelligent transportation;traffic state estimation;Kalman filter;cell transmission model;multi-source data fusion0引言高速公路交通状态估计是交通领域中的一个重要研究方向。

系统分析师考试资料

知识管理(Knowledge Management,KM)就是为企业实现显性知识和隐性知识共享提供新的途径,知识管理是利用集体的智慧提高企业的应变和创新能力。

知识管理包括几个方面工作:建立知识库;促进员工的知识交流;建立尊重知识的内部环境;把知识作为资产来管理。

知识管理在知识资产管理、学习型组织、人力资源管理和信息化四个方面进行深化和突破。

知识管理是企业在面对非连续的变化所致之重大变革之际,所建立的一个包含了将资料、资讯技术与整个组织流程、企业精神等加以整合之过程及成果,其中包含了全体员工的创新力和创造力。

作为一个新生事物,知识管理虽已经被学术界所接受,但目前尚未形成一个能为人们普遍认可的定义。

卡尔·费拉保罗认为“知识管理就是运用集体的智慧提高应变能力和创新能力,是为企业实现显性知识和隐性知识共享提供的新途径”。

马斯(Masie) 认为,知识管理是一个系统地发现、选择、组织、过滤和表述信息的过程,目的是改善雇员对待特定问题的理解。

UanLeI L·ULeary 认为,“知识管理是将组织可得到各种来源的信息转化为知识,并将知识与人联系起来的过程。

知识管理是对知识进行正式的管理,以便于知识的产生、获取和重新利用”。

在信息时代里,知识已成为最主要的财富来源,而知识工作者就是最有生命力的资产,组织和个人的最重要任务就是对知识进行管理。

知识管理将使组织和个人具有更强的竞争实力,并做出更好地决策。

在2000年的里斯本欧洲理事会上,知识管理更是被上升到战略的层次:“欧洲将用更好的工作和社会凝聚力推

动经济发展,在2010年成为全球最具竞争力和最具活力的知识经济实体。

”。

Chapter 2: Logistics1.Illustrate a common trade-off that occurs between the work areas of logistics.Any illustration that demonstrates an inherent trade-off between information,inventory, transportation, warehousing, material handling or packaging isacceptable. The following are a few examples of such tradeoffs:Information is increasingly being used as a substitute for inventory. For instance,a warehouse manager that is in constant contact with a supplier of his/her stocksneed not hold traditional, high levels of inventory. By being “connected”, thesupplier realizes when the warehouse is in need of product and can makeaccommodations of product processing and shipping accordingly. Improved,faster means of transportation also prevent manufacturers and merchandisers from holding high levels of inventory.Poor packaging can lead to product damage in transit. Management should either improve packaging or seek a transportation mode that is more stable and lessdamage-inducing. Regardless, greater costs will be incurred upfront – though they are likely to be offset with reduced costs of product recollection and rework. 2.Discuss and elaborate the following statement: "The selection of a superiorlocation network can create substantial competitive advantage."The statement “The selection of Superior location network can create substantial competitive advantage” holds true with regard to logistical networks. The network design implies customer service and cost considerations. Added value (andperhaps a competitive advantage) may be derived from the “intimacy” of being located near customers. Networks that strive for the highest levels of effectiveness (superior service performance) often do so at significantly higher expense.Networks may also be designed for efficient product flows in order to lowertransportation and inventory holding costs. Depending upon the competitiveenvironment in which a firm operates, competitive advantage may result from either being located near the customers to provide superior service or through low cost service with the cost-efficient network design.3.Why are customer-accommodation operations typically more erratic thanmanufacturing support and procurement operations?Market or physical distribution operations are typically more erratic because they are initiated by the customer, whose behavior can not be controlled by the firm.Manufacturing and procurement operations, on the other hand, are initiated by the firm and considered to be within the firm’s span of control. Howe ver, bettercommunications between the logistics organization and customers can reduce the uncertainty and erratic nature of market-distribution operations.4. How has transportation cost, as a percentage of total logistics cost, tracked since 1980?The transportation costs as a percentage of total logistics costs in US hasincreased over the last 20 years. In 1980, the percentage was approximately 47 percent and this has increased to over 63 percent in 2004. Therefore transportation represents a significant portion of the overall logistics cost.5. Describe the logistics value proposition. Be specific regarding specificcustomer accommodation and cost.Logistical value proposition is a cost framework that aims to match of operating competency and commitment to meet the individual of selected groups ofcustomers’ expectations and requirements. A well-designed logistical network must have high customer response with low operational variance and minimum inventory commitment. However the combinations will be different for different groups. Well designed and operated logistical system can help firms to achieve competitive advantage.6.Describe the fundamental similarities and differences between procurement,manufacturing support and customer-accommodation performance cycles as they relate to logistical control.Procurement performance cycles consist of the many activities that maintain the flow of materials, parts, or finished goods into a manufacturing or distribution facility. The scope of procurement activities is limited. Although similar to the customer order processing cycle, shipments are generally larger and cycles often require much more time. Maintaining raw materials inventory is sometimes less expensive relative to finished goods, since time of delivery and material security is often less sensitive into facility than out to the customer. Another difference is that the number of suppliers of a firm is generally less than the number ofcustomers, making the procurement cycle more direct.Manufacturing support performance cycles serve as the logistics of production.These functions maintain orderly and economic flow of materials and work-in-process inventory to support production schedules. The goal is to supportmanufacturing requirements in the most efficient manner. These are internalcycles to the firm, thus they are rarely affected by behavioral uncertainty.Customer-accommodation performance cycles are those associated withprocessing and delivering customer orders. They link the customers throughtimely and economical product availability. Physical distribution integratesmarketing and manufacturing efforts. To improve the effectiveness of thedistribution system, forecast accuracy must improve to reduce uncertainty. Inaddition to the value of sound forecasting methods, the firm must emphasizeflexibility and responsiveness to deal with the uncertainty of customers in thephysical distribution cycle.pare and contrast a performance cycle node and a link. Give anexample of each.Nodes are facility locations. Forms of communications and transportationrepresent links between the nodes. Most logistical work takes place at nodeswhereas links represent the interface among locations. Nodes represent network facilities where materials are processed and base inventories and safety stocks are maintained. Inventory that is in between nodes is called “in transit”.8.Discuss uncertainty as it relates to the overall logistical performance cycle.Discuss and illustrate how performance cycle variance can be controlled.One of the major objectives of logistical management is to reduce the uncertainty in performance cycles. Since the performance cycles are made up of manyactivities, each with its own volatility or variance, variance over the entire cycle can significantly impede the logistics organization’s efficiency and effectiveness.To control variance, the firm must conform expected cycle time to actual cycle time. If cycle time is less than expected, the delivered product becomes inventory to be stored. If the cycle time is longer than expected, then the firm must rely on safety stocks to satisfy customer demand. In either case there are costs associated with variance. The ides is to eliminate variance by equating actual cycle time to the expected cycle time. This may require adjustments in product flows into or out of the organization.9. What is the logic of designing echeloned logistical structures? Can echeloned and direct structures be combined?The echeloned logistical structure is built on the logic of stocking some level of inventory or performing specific activities at consecutive levels of supply chain.This structure utilizes warehouses to create inventory assortments and achieve consolidation economies associated with large volume transportation shipments.The inventory is position to meet the customers’ requirements faster. Typicalechelon systems use either break bulk or consolidation warehouses. However the service commitment and order size economies determine the most desirable andeconomical structure to service the specific customer. So many supply chains usea combination of echeloned and direct structures to meet their logistical needs.10. Discuss and illustrate the statement “logistics and supply chain are not one in the same concepts.”Supply chain is a strategy that integrates all aspects of satisfying customer requirements, whereas logistics is the process of positioning and managinginventory throughout the supply chain. While logistical performance is a critical aspect of supply chain management, including the requirements of having the right inventory at the right time and place as required by customers, supply chain operations require managerial processes that span functional boundaries within individual firms and link suppliers, trading partners, and customers across organizational boundaries. In essence supply chain strategy establishes the operating framework within which logistics is performed.。

Knowledge -> Intelligence -> Wisdom: Essential Value Chain of the New Economy an updated and expanded version of keynote speechby George PórFounder of Community Intelligence Labsdelivered at"Consultation Meeting on the Future of Organisations and Knowledge Management"of the European Commission'sDirectorate-General “Information Society Technologies”Brussels, May 23-24, 2000“What’s so new about the new economy?”“Through conversation, knowledge workers create the re lationships that define the organization. Conversations--not rank, title, or the trappings of power--determine who is literally and figuratively "in the loop" and who is not.Conversations inside and outside the company are the chief mechanism for making change and renewal an ongoing part of the company's culture. One of the many paradoxes of the new economy is that conversation--traditionally regarded as a waste of time--is in fact the key resource for competing on time.” (Excerpt from “What’s so new ab out the new economy?” a seminal essay by Alan Webber, published in HBR , Jan-Feb 1993)The essential value chain--in an economy in which productive conversations are the source of wealth-creation--is a chain of intangibles: knowledge, intelligence and wisdom.Please join me in an exploration of their inter-relatedness and how value can be augmented at each stage.The wisdom of enterpriseIt’s easier to understand “knowledge” through the lens of intelligence. It’s easier to understand “intelligence” through the lens of wisdom. So, let me start at the end of the value chain -- the wisdom of enterprise: What is it and why is it in demand? Why now?How did wisdom become a key factor of organizational evolution, of successful adaptation to the new economy? There are two essential frameworks that illuminate the nature of the new economy, which answer the question. They are known as “attention economy” and “experience economy.”We’re living in an attention economy when there is an overabundance of information and knowledge, and time -- or attention -- is the scarcest resource. The competition for available is heating up; spending it wisely became a competence of increasing value.How well we use our attention depends on balancing the patterns of spending it between our current and long-view priorities.Wisdom has to do with not only intuiting the long view, understanding systems in the context of their larger whole, but also acting in resonance with what is known as true and lasting. Only wisdom can guide effective decisions on how we spend our attention, both individual and organizational, in the conditions of galloping “complexity multiplied by urgency.” (Doug Engelbart)It’s not only the attention economy that drives the demand for wisdom. Se en through the “experience economy” lens, today’s customers are looking for more than good/ services; they want to have a memorable experience of buying and using them for achieving their aspirations. One of the largest buying power in the US, "cultural creatives" value transformation higher than other type market offers.“No matter how acute an experience, one’s memory of it fades over time. Transformations, on the other hand, guide the individual [and the organizations] towards realizing some aspiration and then help to sustain that change over time. There is no earthly value more concrete, more palpable, or more worthwhile than achieving an aspiration. Nothing is more important, more abiding, or more wealth-creating than the wisdom required to transform customers. An nothing will commend as high a price.” (The Experience Economy, by B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore)Where does the wisdom of enterprise reside and how it can be noticed? We used to think of wisdom as a quality of old, white-hair men or women. Thought of as an emergent quality of the intelligent enterprise, "systemic wisdom" refers to the ability of the organization as a whole to see and to know the pattern that connects. The broader access members get to the meaning-making activities of the organization, the better are its chances to increase its systemic wisdom.The intelligence of enterpriseOrganizations are living social systems. What makes them able to adapt and evolve is that they have a nervous system and intelligence, just like biological systems do.The nervous system of an organization is embedded not in computers and hardware networks, but in the network of conversations that the organization is made of, which lets it learn from its experience.Intelligence, the faculty that makes biological and cultural evolution possible, implies and guides the use of knowledge or “knowing,” the capacity to respond to specific opportunities and challenges as they emerge. As wisdom refers to our effective use of intelligence, intelligence refers to our effective use of knowledge.Intelligence is needed to guide the transformation of organizations into work systems that support all members in reaching their full potential. Only then will the organization manifest the strategic advantage of being capable to learn as fast as the changes in its environment require.“Today's environment is beginning to threaten today's organizations, finding them seriously deficient in their nervous system design. The degree of coordination, perception, rational adaptation, etc., which will appear in the next generation of human organizations will drive our present organizational forms, with their clumsy nervous systems, into extinction.” (Doug Engelbart, 1970)Intelligence is a product of the nervous system, and its evolution defines how well the organism/organization can perform the following functions:• Facilitate the exchange and flow of information among the subsystems of the organism and with its environment.• Coordinate effectively t he actions of the subsystems and the whole• Store, organize, and recall information as needed by the organism• Guide and support the development of new competences and effective behaviorsThe framework presenting these functions can be found in my "Quest for Collective" chapter of "Community Building: Renewing Spirit and Learning in Business" at /cbw/Quest.html .The knowledge of enterprise“Knowledge is informati on that changes something or somebody –either by becoming grounds for actions, or by making an individual (or an institution) capable of different or more effective action” – Peter DruckerKnowledge is an emergent quality of productive conversations, that cannot be “managed” but inspired by work systems that reward learning and innovation. The main incentive for that is companies providing such an environment may attract better talents and more customers, and benefit from the positive feedback loop of market attention.The main threat to the continuous expansion of our creative faculties, both individual and collective, is the deepening gap between the human condition and our capacity to understand it.The same is true at the level of organizations and communities. Have you heard the frequently quoted statement of Lewis Platt, the ex-CEO of Hewlett-Packard: “If HP knew what HP knows, we’d be three times more profitable.”When an organization reaches the self-awareness of its own knowledge, it does so by cultivating its knowledge ecosystem in which information, insights, and inspirations cross-fertilize and feed one another, free from the constraints of geography and schedule.The study, design, and improvement of individual and organizational knowledge ecosystems are the focus of Knowledge Ecology (KE).Along with "organizational intelligence" and the strategy of "knowledge communities," KE is an essential framework and one of the key enablers of the "wisdom-driven enterprise."Situated at the top of the value chain, wisdom-driven businesses will easily provide the highest quality work life experience to their members, and set the context for societal evolution in the next economy.For more information on knowledge ecology, see "The Ecology of Knowledge: a Field of Theory and Practice Key to Research & Technology Development."RecommendationsIf you want to maximize your organization’s potential to continually augment its wisdom, intelligence, and knowledge, and integrate that essenti al value chain, here’s what you can do about it.• Optimize the design of your knowledge ecosystem for diversity and connectivity• Stamp out fear and dominance from work relationships; transform them into trust and partnering• Review your business models and strategies through the lenses of “attention economy” and “experience economy” update them frequently in response to fast-changing conditions.• Re-design your social, knowledge and business architectures and methods, for making them available to get the full benefits of emerging and mature web technologies.Closing commentLet me close my remarks with a voice from the 60’s that sounds particularly timely today:"One of the great liabilities of history is that all too many people fail to remain awake through great periods of social change. Every society has its protectors of the status quo and its fraternities of the indifferent who are notorious for sleeping through revolutions. But today our very survival depends on our ability to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant and to face the challenge of change." (Martin Luther King; emphasis added by GP)。

Managing the KM Trade-Off: Knowledge Centralization versus Distribution1

Matteo Bonifacio (Department of Information Technology, University of Trento, Italy bonifacio@dit.unitn.it)

Pierfranco Camussone (Department of Economics, University of Trento, Italy pierfranco.camussone@economia.unitn.it)

Chiara Zini (Department of Economics, University of Trento, Italy czini@economia.unitn.it)

Abstract: KM is more an archipelago of theories and practices rather than a monolithic approach. We propose a conceptual map that organizes some major approaches to KM according to their assumptions on the nature of knowledge. The paper introduces the two major views on knowledge –objectivist, subjectivist - and explodes each of them into two major approaches to KM: knowledge as a market, and knowledge as intellectual capital (the objectivistic perspective); knowledge as mental models, and knowledge as practice (the subjectivist perspective). We argue that the dichotomy between objective and subjective approaches is intrinsic to KM within complex organizations, as each side of the dichotomy responds to different, and often conflicting, needs: on the one hand, the need to maximize the value of knowledge through its replication; on the other hand, the need to keep knowledge appropriate to an increasingly complex and changing environment. Moreover, as a proposal for a deeper discussion, such trade-off will be suggested as the origin of other relevant KM related trade-offs that will be listed. Managing these trade-offs will be proposed as a main challenge of KM.

Keywords: Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Markets, Mental Models, Communities of Practice, Retrospective Rationality, Bounded Rationality, Constructivism, Organizational Trade-offs. Categories: A.0, A.1, H.1.0, H.1.1

1 Introduction It is quite evident that Knowledge Management (KM) today is more an archipelago of loosely connected and often contradictory theories and practices, rather than a coherent framework to support organizations in managing their knowledge. Moreover, it is clear that every approach is rooted within often implicit (but recognizable) epistemological assumptions about the very nature of knowledge. Such

1 A short version of this article was presented at the I’KNOW '03 (Graz, Austria, July

2-4, 2003).

Journal of Universal Computer Science, vol. 10, no. 3 (2004), 162-175submitted: 30/1/04, accepted: 27/2/04, appeared: 28/3/04 © J.UCSan epistemological reading of the different KM approaches, although well rooted in the KM literature (see for example [Nonaka 95] and [Drucker 94]), is obviously a major one, if we consider that KM aims at managing a resource whose nature has being debated for long and that is still, perhaps more than ever, object of a strong philosophical, cultural, and social debate. As we will suggest, such debate has implications that go far beyond a mere philosophical reading. In fact, different epistemological assumptions lead to very different answers on how knowledge and learning must be organized, and on what is the role of management and technology. Moreover the exploration of the relationship between the very nature of knowledge and its organization, can provide not just a lens in order to explain the coexistence of heterogeneous approaches to KM. It also represents a chance to discover a type of issue which is particularly relevant to managers that have to make decisions; it hides a trade-off between two very valuable opportunities that implicate very undesired consequences. In particular, we claim that each epistemological view and KM approach can be considered as an “archetype” that responds to different, and often conflicting, needs. On the one hand, the need to maximize the value of knowledge through its replication leads to objectification-codification, whereas, on the other hand, the need to keep knowledge appropriate to an increasingly complex and changing environment leads to subjectification-contextualization. From a managerial stand point, this phenomenon should be red as a “good new”: KM is more likely to be considered as a challenging managerial discipline since it deals with the capacity to choose, balance, compromise, and find an equilibrium between conflicting but valuable issues.

2 Objectivist Approach: knowledge as content A first macro-approach to KM, which we call the rational objectivistic approach, has its organizational roots in the theory of rational decision making. In its “classic” version, this theory sees knowledge as an objective, non-problematic resource, whose availability and transparency is taken for granted. Later versions of the theory, inspired by Simon’s work on bounded [Simon 72] and procedural [Simon 76] rationality, made clear that human beings have a limited capacity of elaborating information, that acquiring information costs money, and thus the information available when making a decisions is necessarily limited. In both versions, however, knowledge is viewed as an “object” or content that can be stored and used in a non problematic way, independently from subjectivity of producers and consumers. Two are the major KM views that can derive from the objectivist-rationalistic perspective: the “knowledge as a market” approach, and the “knowledge as intellectual capital” approach.