Credit Cycles,Credit Risk,and Prudential Regulation

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:397.98 KB

- 文档页数:35

谨慎理财的好处英语作文The Benefits of Prudent Financial Management.In today's fast-paced and often unpredictable economic landscape, the importance of prudent financial management cannot be overstated. Prudent financial management is about making wise decisions with one's money, balancing risks and rewards, and planning for both the short and long term.It's about setting financial goals, creating a budget, and sticking to it, saving and investing responsibly, and protecting oneself from unnecessary financial risks. The benefits of prudent financial management are numerous and far-reaching, affecting every aspect of one's life.Financial Security and Stability.Prudent financial management can provide a sense of security and stability in an increasingly volatile world. By saving and investing responsibly, individuals can build up a nest egg that can act as a cushion during times ofeconomic uncertainty or personal crisis. This financial safety net can provide peace of mind and allow individualsto make decisions based on their long-term goals and values, rather than short-term financial pressures.Increased Financial Options.Having a solid financial foundation opens up a world of possibilities. With prudent financial management,individuals can afford to take advantage of opportunities that come their way, such as investing in their own business, pursuing further education, or taking a dream vacation. They can also more easily weather life's unexpected events, such as a job loss or a medical emergency, without having to compromise their financialwell-being.Improved Credit Rating.Prudent financial management often leads to improved credit ratings. By making timely payments, staying within one's means, and avoiding excessive debt, individuals canestablish a positive credit history that can lead to lower interest rates on loans and credit cards, and even better opportunities for financial products and services. A good credit rating can be a valuable asset in today's economy, opening up doors to better financial deals and opportunities.Greater Financial Literacy.Prudent financial management requires a basic understanding of financial concepts such as budgeting, saving, investing, and risk management. As individuals learn to manage their money responsibly, they also become more financially literate, better able to make informed decisions about their money and future. This financial literacy can lead to better financial outcomes throughout life, including during retirement.Peace of Mind.Finally, prudent financial management can bring peace of mind. Knowing that one's financial affairs are in orderand that one has a plan for the future can provide a sense of calm and confidence in an often chaotic world. This peace of mind allows individuals to focus on what really matters in life, such as their families, their careers, and their hobbies, without the constant worry of financial instability or uncertainty.In conclusion, the benefits of prudent financial management are numerous and far-reaching. From financial security and stability to increased financial options and improved credit ratings, the practice of managing one's money responsibly can lead to a better financial future and a more fulfilling life. In today's economy, it is increasingly important for individuals to take control of their financial destiny and make wise decisions with their money. By doing so, they can enjoy the peace of mind and financial freedom that come from being financially responsible and prudent.。

CFA考试一级章节练习题精选0331-46附详解)1、All else being equal, the floor on a floating-rate security is most likely to benefitthe :【单选题】A.issuer if interest rates fall.B.bondholder if interest rates fall.C.bondholder if interest rates rise.正确答案:B答案解析:对于浮动利率证券的利率底,意味着当利率下跌低于利率底时,该浮动利率证券还是以利率底来支付利息,锁定了债券持有人获得利息回报的最低下限,对于债券持有人是有利的。

1、An index provider has created a new investable index that tracks the hedge fund industry. Any fund that follows a long/short equity strategy can enter the index. The index provider places new constituents in the index at the end of each year and incorporates the new funds’ track record in the database. Which of the following is least likely a bias that might distort the historical performance of the index?【单选题】A.Backfilling.B.Self-selection.C.Tracking error.正确答案:C答案解析:“Alternative Investments,” Bruno Solnik and Dennis McLeavey2011 Modular Level I, Vol. 6, pp. 227-229Study Session 18-74-lDiscuss the performance of hedge funds, the biases present in hedge fund performance measurement, and explain the effect of survivorship bias on the reported return and risk measures for a hedge fund database.C is correct because this is not a bias that is associated with distorting the performance of a hedge fund index. Tracking error is a risk more commonly associated with mutual funds and ETFs when their investments deviate significantly from those in the index it is benchmarked against. Many hedge funds pursue absolute returns and may deviate materially from indices.1、High Plains Capital is a hedge fund with a portfolio valued at $475,000,000 at the beginning of the year. One year later, the value of assets under management is $541,500,000. The hedge fund charges a 1.5% management fee based on the end-of-year portfolio value, and a 10% incentive fee. If the incentive fee and management fee are calculated independently, the effective return for a hedge fund investor is closest to:【单选题】A.10.89%.B.11.06%.C.12.29%.正确答案:A答案解析:“Introduction to Alternative Investments,” Terri Duhon, George Spentzos, CFA, and Scott D. Stewart, CFA2013 Modular Level I, Vol. 6, Reading 66, Section 3.3.1Study Session 18-66-fDescribe, calculate, and interpret management and incentive fees and net-of-fees returns to hedge funds.A is correct. The management fee = $541,500,000 × 0.015 = $8,122,500The incentive fee = ($541,500,000 - $475,000,000) × 0.10 = $6,650,000Total fees = $14,772,500Return = ($541,500,000 - $475,000,000 - $14,772,500)/$475,000,000 = 0.1089 or 10.89%.1、U.S. farmers have become concerned that the future supply of wheat production will exceed demand. Any hedging activity to sell forward would most likely protect against which market condition?【单选题】A.ContangoB.Full carryC.Backwardation正确答案:C答案解析:“Investing in Commodities”, Ronald G. Layard-Liesching2013 Modular Level I, Vol. 6, Reading 67, Section 1Study Session 18-67-aExplain the relationship between spot prices and expected future prices in terms of contango and backwardation.C is correct because when a commodity market is in backwardation, the futures price is below the spot price because market participants believe the spot price will be lower in the future. When futures prices are above spot prices, the market is said to be in contango.1、Venture capital investments used to provide capital for companies initiating commercial manufacturing and sales are most likely to be considered a form of:【单选题】A.first-stage financing.B.mezzanine financing.C.second-stage financing.正确答案:A答案解析:“Alternative Investments,” Bruno Solnik and Dennis McLeavey2010 Modular Level I, Vol. 6, p. 214Study Session 18-73-gExplain the stages in venture capital investing, venture capital investment characteristics, and challenges to venture capital valuation and performance measurementVenture capital investments provided to initiate commercial manufacturing and sales is considered a form of first-stage financing.。

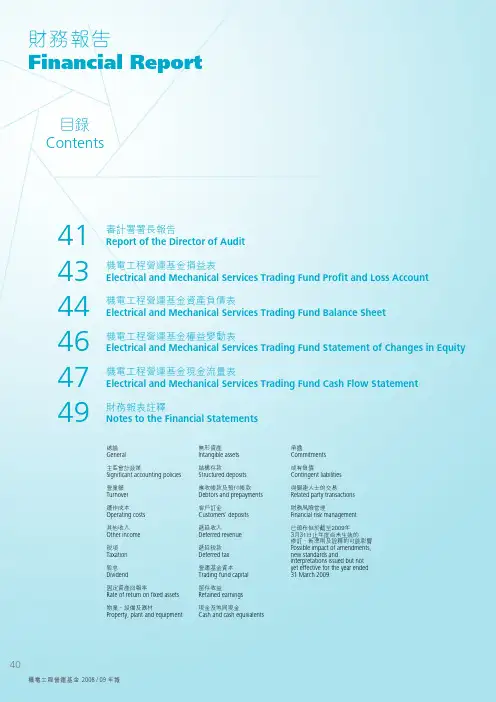

目錄Contents41 43 44 46 47 49審計署署長報告Report of the Director of Audit機電工程營運基金損益表Electrical and Mechanical Services Trading Fund Profit and Loss Account機電工程營運基金資產負債表Electrical and Mechanical Services Trading Fund Balance Sheet機電工程營運基金權益變動表Electrical and Mechanical Services Trading Fund Statement of Changes in Equity 機電工程營運基金現金流量表Electrical and Mechanical Services Trading Fund Cash Flow Statement財務報表註釋Notes to the Financial Statements總論General主要會計政策Significant accounting policies營業額Turnover運作成本Operating costs其他收入Other income稅項Taxation股息Dividend固定資產回報率Rate of return on fixed assets物業、設備及器材Property, plant and equipment無形資產Intangible assets結構存款Structured deposits應收帳款及預付帳款Debtors and prepayments客戶訂金Customers' deposits遞延收入Deferred revenue遞延稅款Deferred tax營運基金資本Trading fund capital留存收益Retained earnings現金及等同現金Cash and cash equivalents承擔Commitments或有負債Contingent liabilities與關連人士的交易Related party transactions財務風險管理Financial risk management已頒布但於截至2009年3月31日止年度尚未生效的修訂、新準則及詮釋的可能影響Possible impact of amendments,new standards andinterpretations issued but notyet effective for the year ended31 March 2009財務報告Financial Report審計署署長報告Report of the Director of Audit獨立審計報告致立法會茲證明我已審核及審計列載於第43至72頁機電工程營運基金的財務報表,該等財務報表包括於2009年3月31日的資產負債表與截至該日止年度的損益表、權益變動表和現金流量表,以及主要會計政策概要及其他附註解釋。

Chapter Twenty TwoGeographic Diversification: DomesticChapter OutlineIntroductionDomestic ExpansionsRegulatory Factors Impacting Geographic Expansion∙Insurance Companies∙Thrifts∙Commercial BanksCost and Revenue Synergies Impacting Geographic Expansion by Merger or Acquisition ∙Cost Synergies∙Revenue SynergiesOther Market- and Firm-Specific Factors Impacting Geographic Expansion Decisions The Success of Geographic Expansions∙Investor Reaction∙Postmerger PerformanceSummarySolutions for End-of-Chapter Questions and Problems: Chapter Twenty Two1.How do limitations on geographic diversification affect an FI’s profitability?Limitations on geographic diversification increase FI profitability by creating locally uncompetitive markets. FIs in these markets earn monopoly rents that are protected by limitations on geographic expansion by potential competitors. Limitations on geographic diversification reduce FI profitability by preventing the FI from exploiting any economies of scale and/or scope or revenue synergies that may be available.2.How are insurance companies able to offer services in states beyond their state ofincorporation?Insurance companies are state-regulated firms that are not prohibited from establishing subsidiaries and offices in other states. Further, the capital requirements are kept low by state regulators.3.In what way did the Garn-St Germain Act and FIRREA provide incentives for theexpansion of interstate branching?Both legislative acts provided for sound banks and thrifts to acquire failing banks and thrifts across state lines. These acquisitions could be operated either as separate subsidiaries or as branches of the acquiring institution.4.Why were unit and money center banks opposed to bank branching in the early 1900s?Smaller unit banks were afraid of losing retail business to the larger branching banks, and the larger money center banks were afraid of losing correspondent business such as check clearing and other payment services.5.In what ways did the banking industry continuously succeed in maintaining interstatebanking activities during the 50-year period beginning in the early 1930s? What legislative efforts did regulators use to respond to each foray by banks into previously prohibitedbanking and commercial activities?The McFadden Act of 1927 restricted the branching activity of nationally chartered banks to the same extent allowed for state-chartered banks that generally were disallowed from such activity. As a result, the banking industry attempted to circumvent the prohibition of interstate banking by establishing subsidiaries rather than branches under the holding company organizational form. The Douglas Amendment to the Bank Holding Company Act restricted the acquisition of banking units to the state-allowed activities. However, the law did not prohibit one-bank holding companies from acquiring nonbank subsidiaries that sold financial products. Thus the path to geographic expansion continued as banks searched for loopholes to circumvent the legislative restrictions placed on their activities.6. What is the difference between an MBHC and an OBHC?A multibank holding company is a parent organization that owns more than one bank subsidiary, and a one-bank holding company is a parent organization that owns only one bank subsidiary. Each organization may own other subsidiaries that provide services closely related to banking as allowed by regulatory authorities.7. What is an interstate banking pact? How did the three general types of interstate bankingpacts differ in their encouragement of interstate banking?An interstate banking pact is an agreement between states defining the conditions under which out-of-state banks can acquire in-state subsidiaries. A major feature of these pacts normally was the reciprocity conditions awarded each state involved. A nationwide pact allowed out-of-state banks to purchase target banks even if the acquirer’s state did not allow such activity. A nationwide reciprocal pact allowed purchase only if the acquirer’s state allowed the same activity. Third, a regional pact allowed out-of-state acquisitions within a small number of states only under conditions of reciprocity.8. What significant economic events during the 1980s provided the incentive for the Garn-StGermain Act and FIRREA to allow further expansion of interstate banking?The bankruptcy of the FSLIC and the depletion of the FDIC’s insurance reserves provided incentives to allow out-of-state acquisitions to resolve bank failures. The Garn-St Germain Act allowed banks to acquire failing thrifts across state lines. Finally, FIRREA allows for the purchase across state lines of healthy thrifts.9. What is a nonbank bank? What legislation allowed the creation of nonbank banks? Whatrole did nonbank banks play in the further development of interstate banking activities?A nonbank bank is a financial institution that did not meet the requirement of (1) making commercial loans and (2) accepting demand deposits as defined in the 1956 Bank Holding Company Act. By purchasing an out-of-state bank and divesting its commercial loans, a large bank or bank holding company could create a nonbank bank that could be used to provide retailor consumer finance banking activities. This loophole was not closed until the Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987.10. How did the development of the nonbank bank competitive strategy further clarify themeaning of the term activities closely related to banking? In a more general sense, how has this strategy assisted the banking industry in their attempts to provide services and products outside the strictly banking environment?The Bank Holding Company Amendments of 1970 specified that nonbank activities had to be closely related to banking. As the growth rate of nonbank acquisitions increased, so too did the pressure on the Federal Reserve to expand the list of these acceptable activities. The nonbank subsidiaries eventually were allowed to provide more than 60 different types of financial products. Thus banks learned how to replicate full-scale (or nearly) banking institutions without having a legally defined bank.11. How did the provisions of the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching EfficiencyAct of 1994 allow for full interstate banking? What are the expected profit performance effects of interstate banking? What has been the impact on the structure of the banking and financial services industry?The main feature of the Riegle-Neal Act of 1995 is the removal of barriers to interstate banking. In September 1995, bank holding companies were allowed to acquire banks in other states. In 1997, banks were allowed to convert out-of-state subsidiaries into branches of a single interstate bank. The act has resulted in significant consolidations and acquisitions, with the emergence of very large banks with branches all over the country, as currently practiced in the rest of the world. The law, as of now, does not allow the establishment of de novo branches unless allowed by the individual states. As expected, profit performance of the largest banks has been very good over the period 1995 to 1999.12. Bank mergers often produce hard to quantify benefits called X efficiencies and costs calledX inefficiencies. Give an example of each.An X efficiency is a cost saving that is difficult to measure and whose source is difficult to identify. One common example is the reduction in expenses thought to be derived from greater managerial efficiency of an acquiring bank. X inefficiencies occur when a merger results in cost incr eases that are usually attributed to management’s inability to control costs.13. What does the Berger and Humphrey study reveal about the cost savings from bankmergers? What differing results are revealed by the Rhoades study?Berger and Humphrey found that (1) the managerial efficiency of the acquirer is greater than that of the acquiree, (2) the X efficiency gains were small, and (3) the cost savings of mergers with geographic overlap were no greater than those for mergers with no geographic or market share overlap. Rhoades reviewed nine megamergers and found large cost savings. In those cases where cost efficiency gains were not realized, the problems were from integrating data processing and operating systems.14. What are the three revenue synergies that may be obtained by an FI from expandinggeographically?The three revenue synergies that an FI may obtain by expanding geographically are as follows:(a) Opportunities to increase revenue because of growing market share.(b) Different credit risk, interest rate risk and other risks that allow for diversification benefitsand the stabilization of revenues.(c) Expansion into less-than-competitive markets, which provides opportunities to reap someeconomic rents that may not be available in competitive markets.15. What is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index? How is it calculated and interpreted?The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a measure of market concentration whose value can be 0 to 10,000. The index is measured by adding the squares of the percentage market share ofthe individual firms in the market. An index value greater than 1,800 indicates a concentrated market, a value between 1,000 and 1,800 indicates a moderately concentrated market, and an unconcentrated market would have a value less than 1,000.16. City Bank currently has 60 percent market share in banking services, followed byNationsBank with 20 percent and State Bank with 20 percent.a. What is the concentration ratio as measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)?HHI = (60)2 + (20)2 + (20)2 = 4,400b. If City Bank acquires State Bank, what will be the new HHI?HHI = (80)2 + (20)2 = 6,800c. Assume the Justice department will allow mergers as long as the changes in HHI do notexceed 1,400. What is the minimum amount of assets that City Bank will have todivest after it merges with State Bank?This is a little tricky. For City Bank to complete the merger, its maximum HHI should besuch that when it disposes of part of its assets, the HHI will be X 2 + Y 2 + Z 2 = 5,800. Since Z = 20 percent, we need to solve the following: X 2 + Y 2 = 5,400; that is, 5,800 less the share of Z 2 which is 202 or 400.If the merger stands with no adjustment, then X = 80 and Y = 0. But some portion of Xmust be liquidated. Therefore we need to solve the equation (80 – Q)2 + Q 2 = 5,400 where Q is the amount of disinvestment. This requires solving the quadratic equation of the form: Q 2 + (80 - Q)2 = 5,400 which expands and simplifies to 2Q 2 – 160Q + 1,000 = 0.Using the formula: Q = 2a4ac) - b ( b -2 , we get Q = 73.1662 percent, which means City Bank has to dispose of 6.8338 percent of total banking assets. To verify, we can check the total relationship: (73.1662)2 + (6.8338)2 + (20)2 = 5,800.17. The Justice Department has been asked to review a merger request for a market with thefollowing four FI's.Bank AssetsA $12 millionB $25 millionC $102 millionD $3 milliona. What is the HHI for the existing market?Bank Assets Market ShareA $12 m 8.45 %B $25 m 17.61%C $102 m 71.83%D $3 m 2.11%100.00%The HHI = (8.45)2 + (17.61)2 + (71.83)2 + (2.11)2 = 5,545.5b. If Bank A acquires Bank D, what will be the impact on the market's level ofconcentration?Bank Assets Market ShareA $12 m 10.56%B $25 m 17.61%C $102 m 71.83%100.00%The HHI = (10.56)2 + (17.61)2 + (71.83)2 = 5,581c. If Bank C acquires Bank D, what will be the impact on the market's level ofconcentration?Bank Assets Market ShareA $12 m 8.45 %B $25 m 17.61%C $102 m 73.94%100.00%The HHI = (8.45)2 + (17.61)2 + (73.94)2 + (2.11)2 = 5,848.6d. What is likely to be the Justice Department's response to the two merger applications?The Justice Department may challenge Bank C’s application to acquire Bank D since it significantly increases market concentration (HHI = 5,848.6). On the other hand, the Justice Department would most likely approve Bank A's application since the merger causes only a small increase in market concentration (HHI = 5,581).18. The Justice Department measures market concentration using the HHI of market share.What problems does this measure have for (a) multiproduct FIs and (b) FIs with global operations?(a) The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) for multiproduct firms is calculated either on thebasis of total assets or one particular product (say, deposits). Neither solution is entirely appropriate. Use of total assets distorts market share calculations since different FIs have different product mixes. Moreover, an HHI based on total assets will not be accurate if there are different market concentration levels in each product market.(b) Since the calculation of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index specifies a market area, results aredependent upon the assumption of the appropriate geographic market. Global FIs willundoubtedly have activities outside of the specified market area. If these are omitted in the calculation of market shares, the FIs’ market share may be understated. However, if they are included, this may overstat e the global FIs’ market share and make the market appear to be more concentrated than it is in actuality.19. What factors, other than market concentration, does the Justice Department consider indetermining the acceptability of a merger?Other factors considered by the Justice Department include ease of entry, the nature of the product, the terms of sale of the product, market information about specific transactions, buyer market characteristics, conduct of firms in the market, and market performance.20. What are some plausible reasons for the percentage of assets of small banks decreasing andthe percentage of assets of large banks increasing while the percentage of assets ofintermediate banks has stayed constant since 1984?One reason for the decreasing share of small bank assets is the wave of mergers that has taken place over the 13 year time period. If two small banks merge, the merged bank may have assets that move it into the next higher asset category. The changes in the interstate banking laws have encouraged this wave of mergers. Finally, the growth of the national economy has been unprecedented during this time, which has caused the entire banking industry to perform well since the late 1980s.21. According to empirical studies, what factors have the highest impact on merger premiumsas defined by the ratio of a target bank’s purchase price to book value?Premiums appear to be higher in states with the most restrictive regulations and for target banks with high-quality loan portfolios. Interestingly, the growth rate of the target bank seems to have little effect on bid premiums, and profitability and capital adequacy give mixed signals of importance.22. What are the results of studies that have examined the mergers of banks, including post-merger performance? How do they differ from the studies examining mergers of nonbanks? Most studies examining mergers between banks show that both bidding and target banks realize an increase in market value. These results contrast with those of nonbanks studies where only target firms benefit by an increase in stock prices (market value). Bidding firms experience either no gains or in some cases, a decline in market value declines. In addition, studies have also shown that post-merger banks increase their efficiency through reduced operating costs, increased productivity, and enhanced asset growth.23. What are some of the important firm-specific financial factors that influence the acquisitionof an FI?Some of the important factors are the leverage ratio, the amount of loss reserves, the loan to deposit ratio, and the amount of nonperforming loans.24. How has the performance of merged banks compared to that of bank industry averages?Cornett and Tehranian found that merged banks tend to outperform the industry with significant improvements in the ability to attract loans and deposits, increased employee productivity, and enhanced asset growth. Spong and Shoenhair found that acquired banks maintain or increase profits and become more active lenders. Boyd and Graham found that banks formed from the merger of small banks also outperformed the industry.25. What are some of the benefits for banks engaging in geographic expansion?The benefits to geographic diversification are:(a) Economies of scale: If there are efficiency gains to growth, geographic diversification canreduce costs and increase profitability.(b) Risk reduction: Overall risk reduction via diversification.(c) Survival: As nonbank financial firms have increasingly eroded bank s’ market share, banks’campaign to expand geographically can be viewed as a competitive response. That is, as global FIs dominate the financial environment, larger institutions with presence in many regions may better position the FI to compete.(d) Managerial welfare maximization: Empirical evidence suggests that larger institutions offermore lucrative compensation packages with greater amounts of perquisites for managers.Growth via geographic diversification may therefore be in the interests of managers, but not in the interests of stockholders unless the activities increase firm value.。

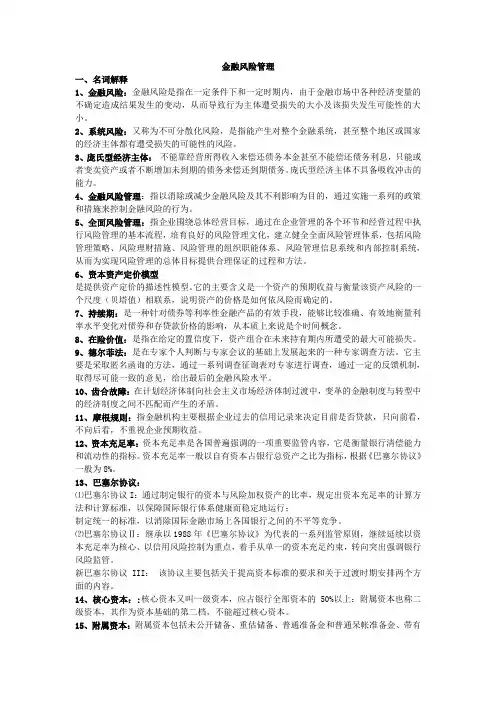

金融风险管理一、名词解释1、金融风险:金融风险是指在一定条件下和一定时期内,由于金融市场中各种经济变量的不确定造成结果发生的变动,从而导致行为主体遭受损失的大小及该损失发生可能性的大小。

2、系统风险:又称为不可分散化风险,是指能产生对整个金融系统,甚至整个地区或国家的经济主体都有遭受损失的可能性的风险。

3、庞氏型经济主体:不能靠经营所得收入来偿还债务本金甚至不能偿还债务利息,只能或者变卖资产或者不断增加未到期的债务来偿还到期债务。

庞氏型经济主体不具备吸收冲击的能力。

4、金融风险管理:指以消除或减少金融风险及其不利影响为目的,通过实施一系列的政策和措施来控制金融风险的行为。

5、全面风险管理:指企业围绕总体经营目标,通过在企业管理的各个环节和经营过程中执行风险管理的基本流程,培育良好的风险管理文化,建立健全全面风险管理体系,包括风险管理策略、风险理财措施、风险管理的组织职能体系、风险管理信息系统和内部控制系统,从而为实现风险管理的总体目标提供合理保证的过程和方法。

6、资本资产定价模型是提供资产定价的描述性模型。

它的主要含义是一个资产的预期收益与衡量该资产风险的一个尺度(贝塔值)相联系,说明资产的价格是如何依风险而确定的。

7、持续期:是一种针对债券等利率性金融产品的有效手段,能够比较准确、有效地衡量利率水平变化对债券和存贷款价格的影响,从本质上来说是个时间概念。

8、在险价值:是指在给定的置信度下,资产组合在未来持有期内所遭受的最大可能损失。

9、德尔菲法:是在专家个人判断与专家会议的基础上发展起来的一种专家调查方法。

它主要是采取匿名函询的方法,通过一系列调查征询表对专家进行调查,通过一定的反馈机制,取得尽可能一致的意见,给出最后的金融风险水平。

10、齿合故障:在计划经济体制向社会主义市场经济体制过渡中,变革的金融制度与转型中的经济制度之间不匹配而产生的矛盾。

11、摩根规则:指金融机构主要根据企业过去的信用记录来决定目前是否贷款,只向前看,不向后看,不重视企业预期收益。

CFA一级考试知识点第八部分固定收益证券债券五类主要发行人超国家组织supranational organizations,收回贷款和成员国股金还款主权(国家)政府sovereign/national governments,税收、印钞还款非主权(地方)政府non-sovereign/local governments(美国各州),地方税收、融资、收费。

准政府机构quasi-governments entities(房利美、房地美)公司(金融机构、非金融机构)经营现金流还款Maturity到期时间、tenor剩余到期时间小于一年是货币市场证券、大于一年是资本市场证券、没有明确到期时间是永续债券。

计算票息需要考虑付息频率,未明确的默认半年一次付息。

双币种债券dual-currency bonds支付票息时用A货币,支付本金时用B货币。

外汇期权债券currency option bongds给予投资人选择权,可以选择本金或利息币种。

本金偿还形式子弹型债券bullet bond,本金在最后支付。

也称为plain vanilla bond(香草计划债券)摊销性债券amortizing bond,分为完全摊销和部分摊销。

偿债基金条款sinking found provision,也是提前收回本金的方式,债券发行方在存续期间定期提前偿还部分本金,例如每年偿还本金初始发行额的6%。

票息支付形式固定票息债券fixed-rate coupon bonds,零息债券会折价发行,面值与发行价之差就是利息,零息债券也称为纯贴现债券pure discount bond。

梯升债券step – up coupon bonds票息上升递延债券deferred coupon bonds/split coupon bonds,期初几年不支付,后期才开始支付票息。

(前期资金紧张或研发型项目)实物支持债券payment-in-kind/PIK coupon bonds票息不是现金,而是实物。

Quantitative1010365/:D 360360:==360:1360A :(1)1Continuously compounded rate of re BD BD MM BD t P P CF Holding Period Yield HPY P FV P Bank Discount Yield r F t FV tr Money Market Yield r HPY t t r Effective nnual Yield EAY HPY -+ =- ⨯⨯ =⨯=-⨯ =+-()12turn: r ln ln 1cc s HPR s ⎛⎫==+ ⎪⎝⎭23653651111(1)(1)21;;);1t tTime weighted Money weighted nini Arithmetic Weighted i i Geometric Geometric Arithmetic Harmonic ni i iy BEY HPY EAY R R IRR Xn X X W X X X X X n X L ⨯--===+=+=+=====<==∑∑∑(1)100y n +⨯2222111[()]2Excess kurtosis = Sample kurtosis - 3()();:;:;111nnniiii i i x X ks Range MaxValue MinValue XXXX MAD PopulationVariance SampleVariance s MAD n nn P k Coefficient of Variat μμσσ===-≤= ----===<-≥- ∑∑∑切比雪夫不等式::;xp fpsion CV XR R Sharp Ratio σ=- =越大越好Excess Kurtosis=Sample Kurtosis 3()1()Odds of event=;Odds against of event=1()()()(|)()(|)();()()()()()=0()()()()(|)()P E P E P E P E P AB P A B P B P B A P A P AorB P A P B P AB P AB P AorB P A P B P AB P B A P A ---=⨯=⨯=+-=+=一般条件:互斥事件:;贝叶斯公式:(|)()()(1)()x x n xn P A B P B P x C P P P A -⨯=⋅⋅-=;贝努力实验:2221,2121,21111222212221122121,21;()[()()][()()]()[()()][()()]()();290% Confidence interval for X is 1.65 ; 95% for 1.96A B A B n p p i i i Cov Cov P A B P A E r P B E r P A B P A E r P B E r E R w E R w w w w Cov X s X s ρσσσσσ===⋅-⋅-+⋅-⋅-=⋅=++±±∑2) ; 95% for 2.58~(,),;()1()(Roy's Safety-first Ratio=;Minimum Acceptable Returnp LL pX sx X N Z F z F z E R R R μμσσσ±-=-=--=/2/20000000000Confidence interval: point Estimate;One tail:,;,;Two tail:,Reject :;F X Z X Z X Z H H H H H H H test statistic critical value αααααμμμμμμ=±≥<≤>== >中心极限定理:0ail to reject ::~(0,1);:~(1)H test statistic critical value X X Z test Z N t test t t n < -=-=-22221121222212121/222212121(1) :~(1);:(S S )~(1,1)Test for equality of means: t-statistic=(Sample Variances assumed unequal);t-statistic=PPs n s chi Square test x x n F test F F n n s x x x x s s s s n n n σ--=--=>----⎛⎫++ ⎪⎝⎭条件:1/222(equal)n ⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭Portfolio Management22221,21212221122121,2,,2()()():()[()]pM f p f pM i mkti i i mkt mktmkti f i M f p fpCov w w w w Cov E R R CML E R R Total Risk systematic Risk unsystematic RiskCov SML CAPM E R R E R R R R Sharpe Ratio ρσσσσσσσσβρσσβσ==++-⎡⎤:=+⎢⎥⎣⎦= + ==⨯=+-- =;()();'()()Mp f M f pp fp p f p M f pM Squared R R R R R R Treynor Measure Jensen s R CAPM R R R R σσαββ-=---- ==-=---Economics%;1,;1,%Pr %;0,normal good(0<<1,necessity good;>1,Luxury);e 0,inferior good%%%Price of related g p p i i i i QOwn price elasticity e elastic e inelasticice QIncome elasticity e e e IncomeQCross elasticity ∆- =><∆∆ =><∆∆ =∆;0,;0,oodbreakeven point if AR=ATC(Perfect competition);TR=TC(imperfect competition)shutdown point if AR<AVC(Perfect competition);TR<TVC(imperfect competition)TR=P Q;AR=TR/Q;c c e substitute e complement><⨯MR=TR/QTC=TFC+TVC;MC=TC/QAccounting profit = total revenue - total accounting costsEconomic profit = Accounting profit-implicit opportunity costs=total revenue-explicit costs-implicit costs Normal p ∆∆∆1110rofit = accounting profit - economic profit=;x y x nyNominal GDPGDP deflator=Real GDP ()()()();Fiscal budget deficit=Excess over dome xy yMRS n xQ P Base BaseQ P GDP C I G X M C S TG T S I X M ∆=-∆⨯⨯=⨯⨯=+++-=++-=---用替代,用1替代currentBase PeriodRe [stic investment+trade balance Price CPI=100Price 1Money multiplier =Reserve MV=PY;Real money supply Velocity of money=Price level Real GDP :Nom al Inflati requirementFisher Effect R R E ⨯ ⨯⨯ =+]1Fiscal multiplier =;Marginal propensity to consume1(1)Real Exchange Rate(d/f)=nominal forex rate 1domestic interst (d/f):(d/f)on MPC MPC t foreign CPIdomestic CPIForward No Arbitrage Forex Rate Spot =-- ⨯+- =rate 3601foreign interest rate 360tt ⨯+⨯Equity001111Trigger Price();Trigger ()11Pr ice Weighted Index=number of stocksPrice-changeEqual Weighted Index =(1+) Equal Weighted In ni i nii Arithmetic IM IMLong P price Short P MM MMPinitial index valuen==-+=⨯=⨯-+⨯∑∑1110dex current total market valueMarket capitalization-weighted index=base year index valuebase year total market valueOne-year DDM:;Multiple-y 11Geometric n ps pss s X initial index valueD P k D P P k k ⨯⨯==+++12020ear DDM:...1(1)(1)(1)FCFE=CFO-FCInv+net borrowing;FCFF=CFO-FCInv+Int(1-t)CFO=NI+Dep-Increase in working capital;net borrowing -debt principal+new debt issues P (1n n n ns s s s ns D P D D P k k k k FCFE k =++++++++==+0110100000111) :;(1);(1);:[()](1)///;/nni s s f i M f D DGordon Growth Model P D D g g RR ROE payout ratio ROE payout ratio k g EPSCAPM k R E R R P P D g E D E Payout Ratio Payout Leading P E Trailing P E E k g k g E k g β===⨯+=⨯=- ⨯ =-=+-+ === ===---∑(1)Enterprise Value=MV of common stock+MV of Pre-stock+MV of Debt-Cash and Investment Market Value of equity/;Common equity=total asset-total liabilities-pref Book Value of equityRatio g k g P B Ratio MV ⨯+- ==erred stockAlternativeNAV Per Share Assets - Per Share LiabilitiesProb (1)Appraisal price NOI /Market cap rate;NOI=Income-Operating Expense Market cap rate Benchmark NOI /Benchmark trans nSuccess nCF Venture Capital NPV CF i = =⨯-+==()()()()action price After Tax Net Income NOI D INT *1t After Tax Cash Flow ATNI D PRN principal repayment NOI TAX PRN INT =---=+-=--+Derivative()()floating rate at settlement forward rate 360notional principal 39361+floating rate at settlement 360 rincipal ( )360Option v days FRA FRA days daysNet Fixed Rate Payment P Fixed rate LIBOR ⎡⎤-⨯⎢⎥=⨯=⎢⎥⎢⎥⨯⎣⎦=⨯-⨯;期前,期后()0000alue intrinsic value time value /1covered call S ;Breakeven=S c;Maximum Gain= X (S c)protective put S ;Breakeven=S ;Maximum Loss= X (S )Tfc X R S pp p p =+++=+=---=++-+-cFixed Income112n tt=1t 0Full Price Clean PriceAccrued Interest Accrued interestt PVCF Macaulay duration=PVCF ()Macaulay duration Modified duration=1+periodic market yield Effective Duration=T CouponT T P P P P y+0/2Δy 21absolute yield spread Absolute yield spread =high yield-low yield;Relative yield spread=benchmark bond yieldsubject Yield ratioOptionbondoptionfree bondPut Call OptionP V V V STRIPS Maturity 10111(1)1 bond yield benchmark bond yieldTax Free YieldTax equivalent yield1tax rateOAS Z-spread - Option cost(Z-spread > Nominal Spread, if spot Yield is upward sloping)(1)(1)(1)(1);TT T S f f ff 00n 2N MRT 2Face valueZero coupon bond value=(interest rate risk )(1+)2Reinvestment Income=PV (1+r )-FV-Coupon Total percentage price change=duration effect + convexity effect [MD ()][Conv ()S i Py y P最大]Dollar duration duration bond price 1%(100)PVBPduration bond price 0.01%(1) [Duration PV ]bp bp 不求,算出两个相减也可计算FSAA=L+E; E=CC+R/E; R/E R/E +NI-Div; A=L+CC+R/E +Revenue-Expense-Div current assets Current ratio =current liabilitiescash + marketable securities + A/RQuick ratio =current liabilitiescash Cash ratio =E B B =+ marketable securitiescurrent liabilitiescash + marketable securities + A/RDefensive interval=Average daily expend annual salesReceivables turnover =A/R Inventory turnover =Payables turn COGSInventory over =A/P365Average receivables collection period =receivable turnover365Average inventory processing period =inventory turnover 365Average payment period =payable Cash conversion c turn yc overPurchasePretax margin =total debt total debtD/E ratio=;D/A le = collection period + inve ratio=Equtiy AssetRevenueWorking Capital turno ntory period - payme ver=;Working Ca Average Working Capital nt period EBT Sales pital=Current Asset-Current LiabilityInterest Coverage EBIT+Lease PaymentFixed Charge Coverage=Interest+Leasr Payment Return on assets (ROA) =Return on equity(ROE) Net =ROE=EBITInterestNIAsset NIEquity=Profit Margin Asset Turnover Financial Leverage Tax burden Interest burden EBIT Margin Asset Turnover Financial Leverage =ROE=EBT NI Sales AssetSales Asset EquityNI EBIT Sales Asset EBT EBIT Sales Asset Equit ⨯⨯⨯⨯⨯⨯⨯⨯=⨯⨯⨯⨯LIFO Reserve COGS LIFO Reserve taxable income tax rate=tax payableIncome tax expense=tax payable+DTL-DTAReported effec END BGN FIFO LIFO FIFO LIFO yInventory Inventory Purchase COGS Inventory Inventory COGS =+-=+=-∆⨯∆∆income tax expensetive tax rate=pretax incometax payableeffective tax rate=pretax incomeCorporate Finance120120101100...(1)(1)(1)(1)1(1):();;(1);nnniii d d ps ps c spsps s f m f s s Asse CF CF CF NPV CF k k k CF CF IRR NPVPI CF WACC W k t W k W k D k PCAPM k R R R D D D k g P g RR ROE payout ratio ROE payout ratio P k g EPSββ==+++++++=+=+=⨯-+⨯+⨯==+-=+==⨯=- ⨯ =-∑Pr ;[1(1)]1(1)cost of capital change :Break Point=weight of capital structure()();()()(Equityt oject Asset D t EDt EMCC Q P V S TVC EBIT Q P V FDOL DFL Q P V F S TVC F EBIT Interest Q P V F IQ P DTL DOL DFL βββ==⨯+-⋅+-⋅----====--------=⨯=)();365365365;//Net working capital=Current Asset-Current Liabilitie Breakeven OperatingBE V S TVCQ P V F I S TVC F IF I FQ Q P V P VCash Conversion Cycle Purchase Inv COGSCOGS Sales Purchase Inventory A R A PC --=------+==-- =+-=∆+365/()(1)11tdiscount ost of trade credit EAR discount=+--史上最全的CFA复习笔记,爱不释手T-bill rates是nominal risk-free ratesnominal risk-free rate= real risk-free rate + expected inflation ra te风险种类:default risk违约风险liquidity risk 流动性风险maturity risk 久期风险(利率风险)EAR=e^t-1贴现率=opportunity cost,required rate of return,cost of capital ordinary annuity在期末产生现金流annuity due在期初产生现金流永续年金perpetuity PV=PMT/(I/Y)对于同一个项目IRR和NPV结论相同:IRR大于必要收益率则NPV为正,否则NPV为负如果公司目标是权益所有人财富最大化,那么始终选择NPV(通常都是这样)HPR(持有期回报)=(期末值-期初值)/期末值或者(期末值-期初值+现金)/期末值Time-weighted rate of return时间的加权平均值,(1+HPR1)(1+HPR2)…即几何平均数如果组合处于高上涨期,时间加权平均会比金钱加权平均小,反之则大。

1. 额外报酬(Additional Compensation):客户会提供的额外报酬,注意披露。

2. 旁观者效应(Bystander Effect):情景影响的一种,当周围有旁人时,人的行为会受到影响。

3. 考生保证书(Candidate Pledge):考试时考生签署的保证遵守考试纪律的承诺书。

4. 警告信(Cautionary Letter):警告信是非公开的,一般适用于相对不太严重的违反行为。

5. 民事非暴力反抗(Civil Disobedience):民众举行的抗议活动,属于个人行为。

6. 客户指定经纪费(Client Directed Brokerage):客户指定经纪费如何使用的一种费用。

7. 共同投资(Co-Investment):与客户共同进行投资,目的是共担风险。

8. 合规部门(Compliance Department):保持公司治理、风险控制及遵守法律法规的部门。

9. 机密(Confidentiality):遵守保密性,不可随意的泄露客户的信息。

10. 对价(Consideration):一方为换取另一方做某事的承诺而向另一方支付的金钱代价或得到该种承诺的代价。

11. 信用评级机构(Credit-rating Agencies):对证券发行人和证券信用进行等级评定的组织,给出的债券评级会影响债券发行人的融资成本。

12. 下行风险(Downside Risk):是指未来股价走势有可能低于分析师或投资者预期的目标价位的风险。

13. 尽职调查(Due Diligence):投资人在与目标企业达成初步合作意向后,投资人对目标企业一切与本次投资有关的事项进行现场调查、资料分析的活动。

14. 公平交易(Fair Dealing):在提供投资分析,做投资建议,采取投资决策等活动时,公平公正对待所有的客户。

15. 信托(Fiduciary):委托人基于对受托人的信任,将其财产权委托给受托人,由受托人按委托人的意愿以自己的名义,为受益人的利益或特定目的,进行管理和处分的行为。

Absorption 吸收,一国对最终商品和劳务的总支出,包括一国的实际消费支出、实际投资支出、实际政府支出和对进口商品和劳务的实际支出。

Absorption Approach 吸收论,一种关于国际收支和汇率决定的理论,强调一国的支出(或者称为“吸收”)及收入的作用。

根据吸收论,如果一国的实际收入超过它所吸收的商品和劳务数量,那么该国的经常账户将出现盈余;如果一国的实际收入小于它所吸收的商品和劳务数量,那么该国的经常账户将出现赤字。

Absorption Instrument 吸收工具,一国政府通过改变对国内产出的购买或通过影响消费和投资支出来提高或降低该国吸收水平的能力。

Adverse Selection 逆向选择,发行融资工具的公司将借来的资金用于低价值、高风险的投资项目的倾向。

Aggregate Demand Schedule 总需求曲线,实际收入和价格水平的各种组合,这些组合使得IS -LM 模型达到均衡,从而保证了实际收入等于总计划支出并且实际货币余额市场也实现均衡。

Aggregate Expenditures Schedule 总支出曲线,描述了在各种实际国民收入水平下相应的家庭部门、公司部门和政府部门计划支出的总和。

Aggregate Net Autonomous Expenditures 总净自主性支出,可以看作与国民收入水平无关的自主性消费、自主性投资、自主性政府支出和自主性出口支出的总量。

Aggregate Supply Schedule 总供给曲线,描述在各种可能的价格水平下相应的所有工人和公司的实际产出的曲线。

American Option 美式期权,在合同到期之前(包括到期日在内),持有者可以随时买入或者卖出某种证券的期权合约。

Announcement Effect 公告效应,中央银行的政策措施信号引起人们对近期市场条件变化的预期,从而导致私营市场利率或者汇率的变化。

Assignment Problem 政策指派问题,关于中央银行和财政部究竟谁应当对达到一国国内或者国际政策目标负责的问题。

“三大模块”题库(英语简答题)1. The function of bank capital regulation mainly reflected in which aspects?a. Enhance the ability of absorb the unpredictable lossb.Improve the public’ confidence to the banking systemc.Intensify bank’s corporation governance2. What does CAMELS Rating System mean?Ans: An international bank-rating system where bank supervisory authorities rate institutions according to six factors. The six factors are represented by the acronym "CAMELS." The six factors examined are as follows: Capital adequacy, Asset quality, Management quality, Earnings, Liquidity, Sensitivity to Market Risk.3. Please list the main risks related to the liability of a commercial bank? Answer: market risk, operational risk, liquidity risk, legal risk and solvency risk.《商业银行主要业务》P108问答题第一题4. Please explain the regulatory objectives of the CBRC briefly.a. Protect the interests of depositors and consumers through prudential and effective supervision;b. Maintain market confidence through prudential and effective supervision;c. Enhance public knowledge of modern finance though customer education and information disclosured. Combat financial crimes出处:《银行业监管理念监管文化》5. Briefly introduce the principals of risk-based supervision.Answer: The prudential supervision; the sustainable supervision; the banking corporation supervision; the slandered6. Can you explain the supervisory and regulatory criteria of the CBRC briefly?a. Promote the financial stability and facilitate innovation at the same time;b. Enhance the international competitiveness of the Chinese banking sector;c. Set appropriate supervisory and regulatory boundaries and refrain from unnecessary controls;d. Encourage fair and orderly competition;e. Clearly define the accountability of both the supervisor and the supervised institutions;f. Employ supervisory resources in an efficient and cost-effective manner.出处:《银行业监管理念监管文化》7. What are the three pillars of Basel II?Answer: Pillar 1: minimum capital requirement;Pillar 2: supervisory review process;Pillar 3: market discipline.8. What is the definition and characteristics of VaR (value at risk)? Answer: For a given portfolio, probability and time horizon, VaR is defined as a threshold value such that the probability that the market to market loss on the portfolio over the given time horizon exceeds this value is the given probability level.The most important characteristics of VaR are as follows:(1) VaR is a summary measure.(2) VaR requires that it is possible to express future profits and losses on a portfolio in stochastic terms.(3) VaR depends on the time horizon chosen.(4) VaR depends on the probability level chosen.9. What are the supervisory and regulatory criteria?Answer: (1) Promote the financial stability and facilitate financial innovation at the same time.(2) Enhance the international competitiveness of the Chinese banking sector.(3) Set appropriate supervisory and regulatory boundaries and refrain from unnecessary controls.(4) Encourage fair and orderly competition.(5) Clearly define the accountability of both the supervisory and supervised institutions.(6) Employ supervisory resources in an efficient and cost-effective manner.10. How can we conduct stage-by-stage regulation on banks according to their specific conditions in the field of financial derivative products? Answer: (1) To examine whether the banks have the qualification to operate financial derivative products;(2) To pay much attention to the banks which operate the financial derivative products with standard contracts such as future, forward and swap;(3) For the banks operating option, we should analyze the specific conditions to adopt regulation measures. For the banks which operate call option, we just pay much attention, as the risk level of it is relatively low.But, for the banks which operate put-option, the real content of trading should be understood. If the bank operates put option just for the earning purpose, more attention should be paid to its internal control, talent, suitable quota, etc;(4) For the banks which operate sophisticated derivative products, regulators should understand the type of the products at first and analyze whether the products can be divided to different derivative products with standard contracts. If not, special attention should be paid to them and special examination should also be organized.11. What are the seven major aspects about banking regulation referred in <<Core Principles>>?Answer: premises for effective banking regulation; regulatory requirements of licensing( authorization ) ;prudent regulatory criteria and requirements;steady regulatory approaches; regulatory information disclosure ; measures to deal with weak banks; cross-border regulatory requirements.(出处:《银行监管理念监管文化》)12.What is the “three pillars” of the Basel Ⅱ Accord?答案:A. minimum capital requirementsB. supervisory reviewC. market discipline based on risk disclosure出处: 《银行监管实务》P 38613. According to the Basel Committee, what is the three main risks concerning to the banking system?答案:market risk, credit risk and operational risk出处:《银行监管实务》14. What does SPV stand for?答案:Special Purpose Vehicle出处:《商业银行主要业务》P 36115. What’s the risk-focused supervision?Answer: The risk-focused supervision means the supervision can identify the inherent risks of the commercial banks, and then evaluate the risk involved in the operation and management of the banks, in order to evaluate the running and management of the banks systematically, continuously. Risk-focused supervision was Safety and Soundness Supervision or Examination in 1979, it was based on CAMEL Rating System. Now, risk-focused supervision makes the supervision departments keep in touch with the banks, evaluate the risk by off-site supervision, plan the examination, than get the result of CAMELS byon-site examination.16. According to the guaranty law ,what right may be pledged? Answer: The following rights may be pledged:(1)bills of exchange, checks, promissory notes, bonds, certificates of deposit, warehouse receipts, bills of lading;(2)shares of stocks or certificates of stocks which are transferable according to law;(3)the rights to exclusive use of trademarks, the property right among patent rights and copyrights which are transferable according to law; (4)other rights which may be pledged according to law.17. the main reasons for internal control failure of the commercial banks:Answer:(1)Weak control culture(2)Inadequate risk identification and assessment(3)Chaos control structure(4)Distortion of information, communication void(5)The continued lack of internal control procedures18. What are the five factors of the CAMELS rating system?Answer:Capital adequacy、the asset quality 、management、earning ability and the liquidity.19. Banks must operate under a perfect criterion for credit. What have been included in a perfect criterion for credit?Answer:(1)A well-defined criterion for credit must be established.(2)banks must have enough information to evaluate synthetically the real risk to the borrower and bargainer.(3)Evaluate the risks and earnings of syndicated loan in the way of independent credit.20. Can you tell the differences between the corporate governance and internal control?Answer:Corporate governance is a bank’s basic structure and institutional arrangement , when the ownership and management are separated, protecting the rights of shareholders and stakeholders. Generally speaking, corporate governance include structure and mechanism, while internal control , as it come to operating process , is the segregation of duties and institutional arrangement. Although they similar in institutional arrangement , belong to different levels. Corporate governance relates tothe overall organization and operation of banks, and internal control is the level of banking system and its implementation.21. What is the concept of Financial Derivatives?Answer:A derivative is a security which “derives” its value from another underlying financial instrument, index, or other investment. Derivatives are available based on the performance of stocks, interest rates, currency exchange rates, as well as commodities contracts and various indexes. Derivatives give the buyer greater leverage for a lower cost than purchasing the actual underlying instrument to achieve the same position. For this reason, when used properly, they can serve to “hedge” a portfolio of securities against losses. However, because derivatives have a date of expiration, the level of risk is greatly increased in relation to their term. One of the simplest forms of a derivative is a stock option. A stock option gives the holder the right to buy or sell the underlying stock at a fixed price for a specified period of time.22. What is the concept of check? And what does the check contain? Answer:Check is issued by the drawer. And the entrusted bank must pay amount of money to the recipient or to the check holder unconditional when thebank see the check.The type of check: Cash Check\ Transfer check\ open check23. What is the primary objective of the CBRC?Protect the interests of depositors and consumers by prudential and effective supervision.24. Briefly introduce the relation and difference among accounting capital, regulatory capital and economic capital.Answer: Accounting capital defined by accounting standards generally indicates the permanent investment by banking shareholders, includes ordinary shares, undistributed profits and capital reserves ect. The book value difference of total asset and liability is banking net value. Regulatory capital or called legal capital can be divided into core capital and subsidiary capital, which is the minimum capital requirement by regulatory authority; Economic capital which is the banking capital –owned from the perspective of risk measurement. Indicates the capital than can resist unexpected loss .there is close relationship between the banking rate and risk.25. What are the forms of operational risk?The staff violations, financial crime, inefficient operations and otherrisks.26. How to calculate the operational risk by the Basic Indicator Approach on the Basel II?Based on 15% of the average annual income of last three years.27. According to the risk degree, how many kinds of loans can be divided ? What are they ?Answer: According to the risk degree, loans can be divided into five kinds :Pass, Special attention, Substandard, Doubtful and Loss, and the last three kinds are called Not Performing Loans (NPLs)。

信用风险英语术语下面店铺为大家带来金融英语信用风险英语术语,欢迎大家学习!信用风险英语术语:巴塞尔协议(Basle Agreement)——由各国中央银行、国际清算银行成员签订的国际协议,主要是关于银行最小资本充足的要求。

它也被称为BIS规则(BIS rules)。

保兑信用证(Confi rmed Letter of Credit)——开出信用证的银行和第二家承兑的银行都承诺有条件地担保支付的信用证。

保留所有权的条款(Retention of Title Clause)——销售合同中注明,供应商在法律上拥有货物的所有权,直到顾客支付了货款的条款。

保证契约(Covenant)——借款人承诺遵循借款条约的书面文件,一旦借款人违背了契约书的规定,银行有权惩罚借款人。

本票(Promissory Note)——承诺在指定的日期支付约定金额的票据。

边际贷款(Marginal Lending)——新增贷款。

可以指对现有客户增加的贷款,也可指对新客户的贷款。

边际客户(Marginal Customer)——指额外的客户。

寻求成长机会的企业会尽力将产品销售给新客户,而且通常是不同种类的客户。

这些新增客户的信用风险可能比企业现有的客户要高。

财产转换贷款(Asset Conversion Loan)——用于短期融资的短期贷款,例如,季节性的筹集营运资金。

财务报告/财务报表(Financial reports/statements)——财务报告或财务报表是分析企业信用风险时的重要信息来源。

财务报告和财务报表提供了和收入、成本、利润、现金流量、资产和负债相关的信息。

财务信息的最重要来源是企业的年报。

财务比率(Financial ratios)——财务比率一般用于分析企业的信誉。

每一个比率都有特定的分析目的和分析对象。

财务比率是企业一个会计科目与另一个会计科目数值的比值。

在财务分析中,财务比率能体现数量本身无法体现的含义。

MP R AMunich Personal RePEc ArchiveCredit Cycles,Credit Risk,and Prudential RegulationJesus,Saurina and Gabriel,JimenezUNSPECIFIED20March2006Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/718/ MPRA Paper No.718,posted07.November2007/01:13Credit Cycles,Credit Risk,andPrudential Regulation∗Gabriel Jim´e nez and Jes´u s SaurinaBanco de Espa˜n aThis paperfinds strong empirical support of a positive, although quite lagged,relationship between rapid credit growthand loan losses.Moreover,it contains empirical evidence ofmore lenient credit standards during boom periods,both interms of screening of borrowers and in collateral requirements.Wefind robust evidence that during upturns,riskier borrowersget bank loans,while collateralized loans decrease.We developa regulatory prudential tool,based on a countercyclical,orforward-looking,loan loss provision that takes into accountthe credit risk profile of banks’loan portfolios along the busi-ness cycle.Such a provision might contribute to reinforce thesoundness and the stability of banking systems.JEL Codes:E32,G18,G21.∗This paper is the sole responsibility of its authors,and the views represented here do not necessarily reflect those of the Banco de Espa˜n a.We thank R.Repullo and J.M.Rold´a n for very fruitful and lively discussions about prudential banking supervisory devices.We are also grateful for the detailed comments provided by V.Salas;H.Shin,the editor;J.Segura;an anonymous referee;and participants at the BCBS/Oesterreichische Nationalbank Workshop;the Bank of England work-shop on the relationship betweenfinancial and monetary stability;X Reuni´o n de la Red de Investigadores de Bancos Centrales Iberoamericanos in Per´u;XX Jornadas Anuales de Econom´ıa in Uruguay;Foro de Finanzas in Madrid;and FUNCAS Workshop Basilea II y cajas de ahorros in Alicante.In particular,we would like to express our gratitude for the comments of S.Carb´o,X.Freixas, M.Gordy,A.Haldane,P.Hartman,N.Kiyotaki,M.Kwast,rra´ın,J.A. Licandro,I.van Lelyveld,P.Lowe,L.A.Medrano,J.Moore,C.Tsatsaronis, and B.Vale.Any errors that remain are entirely the authors’own.Correspond-ing author:Saurina:C/Alcal´a48,28014Madrid,Spain;Tel+34-91-338-5080; e-mail:jsaurina@bde.es.6566International Journal of Central Banking June2006 1.IntroductionBanking supervisors,after many painful experiences,are quite con-vinced that banks’lending mistakes are more prevalent during upturns than in the midst of a recession.1In good times both bor-rowers and lenders are overconfident about investment projects and their ability to repay and to recoup their loans and the corresponding fees and interest rates.Banks’overoptimism about borrowers’future prospects,coupled with strong balance sheets(i.e.,capital well above minimum requirements)and increasing competition,brings about more liberal credit policies with lower credit standards.2Thus,banks sometimesfinance negative net present value(NPV)projects only to find later that the loan becomes impaired or the borrower defaults. On the other hand,during recessions—when banks areflooded with nonperforming loans,high specific provisions,and tighter capital buffers—banks suddenly turn very conservative and tighten credit standards well beyond positive net present values.Only their best borrowers get new funds;thus,lending during downturns is safer and credit policy mistakes much lower.Across many jurisdictions and at different points in time,bank managers seem to overweight concerns regarding type1lending policy errors(i.e.,good borrowers not getting a loan)during economic booms and underweight type2 errors(i.e.,bad borrowers gettingfinanced).The opposite happens during recessions.Several explanations have appeared in the literature to rational-izefluctuations in credit policies.First of all,the classic principal-agency problem between bank shareholders and managers can feed excessive volatility into loan growth rates.Once managers obtain a reasonable return on equity for their shareholders,they may engage in other activities that depart from thefirm’s value maximization and focus more on their own rewards.One of these activities might be excessive credit growth in order to increase the social presence of the bank(and its managers)or the power of managers in a con-tinuously enlarging organization(Williamson1963).If managers are 1See,for instance,Caruana(2002),Ferguson(2004),and the numerous joint announcements by U.S.bank regulators in the late nineties warning U.S.banks to tighten credit standards.2A loose monetary policy can also contribute to overoptimism through excess liquidity provision.Vol.2No.2Credit Cycles,Credit Risk,and Prudential Regulation67 rewarded more in terms of growth objectives instead of profitability targets,incentives to rapid growth may result.This has been doc-umented previously by the expense preference literature and,more recently,by the literature that relates risk and managers’incentives.3 Strong competition among banks or between banks and other financial intermediaries erodes margins as both loan and deposit interest rates get closer to the interbank rate.To compensate for the fall in profitability,bank managers might increase loan growth at the expense of the(future)quality of their loan portfolios.Excess capacity in the banking industry is being built up.Nevertheless,that will not impact immediately on problem loans,so it might encourage further loan growth.In a more formalized framework,Van den Heuvel(2002)shows that the combination of risk-based capital requirements,an imper-fect market for bank equity,and a maturity mismatch in banks’balance sheets gives rise to a bank capital channel of monetary pol-icy.In boom periods,when banks show strong balance sheets and capital buffers,they overlend.However,as the expansion heads to its end,the surge in loan portfolios has eroded much of the capital buffer;at that point,a monetary shock may trigger a decline in bank profits,stringent capital ratios,and a tightening of lending standards and,subsequently,of loans available tofirms and households.4 Herd behavior(Rajan1994)might also help to explain why bank managersfinance negative NPV projects during expansions.Credit mistakes are judged more leniently if they are common to the whole industry.Moreover,a manager whose bank systematically loses mar-ket share and underperforms its competitors in terms of earnings growth increases his or her probability of beingfired.Thus,managers have a strong incentive to behave as their peers,which,at an aggre-gate level,enhances lending booms and recessions.Short-term objec-tives are prevalent and might explain why banksfinance projects during expansions that,later on,will become nonperforming loans.Berger and Udell(2004)have developed the so-called institu-tional memory hypothesis in order to explain the markedly cyclical 3For the former,see(among others)Edwards(1977),Hannan and Mavinga (1980),Akella and Greenbaum(1988),and Mester(1989).For the latter,see Saunders,Strock,and Travlos(1990),Gorton and Rosen(1995),and Esty(1997).4Ayuso,P´e rez,and Saurina(2004)find evidence of this cyclical behavior of capital buffers.68International Journal of Central Banking June2006 profile of loans and nonperforming loan losses.It states that as time passes since the last loan bust,loan officers become less and less skilled to grant loans to high-risk borrowers.That might be the result of two complementary forces.First,the proportion of loan officers that experienced the last bust decreases as the bank hires new,younger employees and the former ones retire.Thus,there is a loss of learning experience.Second,some of the experienced officers may forget the lessons of the past,especially as more years go by and the former recession becomes a more distant memory.5 Finally,collateral might also play a role in fueling credit cycles. Usually,loan booms are intertwined with asset booms.6Rapid increases in land,house,or share prices increase the availability of funds for those who can pledge such assets as collateral.At the same time,the bank is more willing to lend since it has an(increasingly worthier)asset to back the loan in case of trouble.On the other hand, it could be possible that the widespread confidence among bankers results in a decline in credit standards,including the need to pledge collateral.Collateral,as risk premium,can be thought to be a signal of the degree of tightening of individual bank loan policies.7 Despite the theoretical developments and the banking supervi-sors’experiences,the empirical literature providing evidence of the link between rapid credit growth and loan losses is scant.8In this paper we produce clear evidence of a direct,although lagged,rela-tionship between credit cycle and credit risk.9A rapid increase in loan portfolios is positively associated with an increase in nonper-forming loan ratios later on.Moreover,those loans granted during 5Kindleberger(1978)contains the idea of fading bad experiences among eco-nomic agents.6See Borio and Lowe(2002),Davis and Zhu(2004),and Goodhart,Hofmann, and Segoviano(2005).7The Federal Reserve Board’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices shows the cyclical nature of bank lending standards,loan demand,and loan spreads.Asea and Blomberg(1998)find,with bank-level vari-ables,that the probability of collateralization increases during contractions and decreases during expansions in the United States.8Clair(1992),Keeton(1999),and Salas and Saurina(2002)are a few excep-tions.9Goodhart,Hofmann,and Segoviano(2005)document that credit over GDP is a good predictor of future defaults.Dell’Ariccia and Marquez(forthcoming) predict that episodes offinancial distress are more likely in the aftermath of periods of strong credit expansion.Vol.2No.2Credit Cycles,Credit Risk,and Prudential Regulation69 boom periods have a higher probability of default than those granted during periods of slow credit growth.To our knowledge,this is the first time that such an empirical study,based on loan-by-loan infor-mation,relating credit-cycle phase and future problem loans is being carried out.Finally,we show that in boom periods collateral require-ments are relaxed,while the opposite happens in recessions,which we take as evidence of looser credit standards during expansions.The three empirical avenues provide similar results:In boom periods,when lending accelerates,the seeds for problem loans are being sown.During recession periods,when banks curtail credit growth,they become much more cautious,both in terms of the quality of the borrowers and the loan conditions.Therefore,bank-ing supervisors’concerns are well rooted both in theoretical and empirical grounds and deserve careful scrutiny and a proper answer by regulators.We call the formerfindings procyclicality of ex ante credit risk,as opposed to the behavior of ex post credit risk(i.e., nonperforming loans),which increases during recessions and declines in good periods.10The issue here is to realize that lending policy mistakes occur in good times;thus,a prudential response from the supervisor might be needed at those times.We develop a new regulatory devise specifically designed to cope with procyclicality of ex ante credit risk.It is a countercycli-cal,or forward-looking,loan loss provision that takes into account the former empirical results.Spain already had a dynamic provi-sion(the so-called statistical provision)with a clear prudential bias (Fern´a ndez de Lis,Mart´ınez Pag´e s,and Saurina2000).The main criticism to that provision(coming from accountants,not from bank-ing supervisors)was that resulting total loan loss provisions were excessively“flat”through an entire economic cycle.Although it shares the prudential concern of the statistical provision,the new proposal does not achieve,by construction,aflat loan loss provision through the cycle.Instead,total loan loss provisions are still higher in recessions,but they are also significant when credit policies are the most lax and therefore credit risk(according to supervisors’expe-riences and our empiricalfindings)is entering at a high speed on bank loan portfolios.By making a concrete proposal,we would like 10A thorough discussion of banking regulatory tools to cope with procyclicality of thefinancial system is in Borio,Furfine,and Lowe(2001).70International Journal of Central Banking June2006 to open a debate on banking regulatory tools that can contribute to dampen business-cyclefluctuations and,thus,to enhancefinancial stability.The rest of the paper is organized as follows.Section2provides the empirical evidence on credit cycles and credit risk.Section3 explains the rationale and workings of the new regulatory tool through a simulation exercise.Section4contains a policy discussion, and section5concludes.2.Empirical Evidence on Lending Cycles andCredit Risk2.1Problem Loan Ratios and Credit GrowthSalas and Saurina(2002)model problem loan ratios as a function of both macro-and microvariables(i.e.,bank balance sheet variables). Theyfind that lagged credit growth has a positive and significant impact on ex post credit risk measures.Here,we follow that paper in order to disentangle the relationship between past credit growth and current problem loans.Although in spirit the methodology is simi-lar,there are some important differences worth pointing out.First of all,we use a longer period,which allows us to consider two lend-ing cycles of the Spanish economy.Secondly,we focus more on loan portfolio characteristics(industry and regional concentration and importance of collateralized loans)of the bank rather than on bal-ance sheet variables,which are much more general and difficult to interpret.For that,we take advantage of the information contained in the Central Credit Register(CCR)database run by Banco de Espa˜n a.11The equation we estimate is the following:NPL it=αNPL it−1+β1GDPG t+β2GDPG t−1+β3RIR t+β4RIR t−1+δ1LOANG it−2+δ2LOANG it−3+δ4LOANG it−4+χ1HERFR it+χ2HERFI it+φ1COLIND it+φ2COLFIR it+ωSIZE it+ηi+εit,(1) 11Any loan above e6,000granted by any bank operating in Spain must be reported to the CCR.A detailed description of the CCR content can be found in Jim´e nez and Saurina(2004)and Jim´e nez,Salas,and Saurina(forthcoming).Vol.2No.2Credit Cycles,Credit Risk,and Prudential Regulation71 where NPL it is the ratio of nonperforming loans over total loans for bank i in year t.In fact,we estimate the logarithmic transfor-mation of that ratio(i.e.,ln(NPL it/(100−NPL it)))in order to not curtail the range of variation of the endogenous variable.Since prob-lem loans present a lot of persistence,we include the left-hand-side variable in the right-hand side lagged one year.We control for the macroeconomic determinants of credit risk(i.e.,common shocks to all banks)through the real rate of growth of the gross domestic product(GDPG)and the real interest rate(RIR),proxied as the interbank interest rate less the inflation of the period.Both vari-ables are included contemporaneously as well as lagged one year since some of the impacts might take some time to appear.Our variable of interest is the loan growth rate,lagged two,three, and four years.A positive and significant parameter for those vari-ables will be empirical evidence supporting the prudential concerns of banking regulators since the swifter the loan growth,the higher the problem loans in the future.Moreover,we control for risk-diversification strategies of each bank through the inclusion of two Herfindahl indexes(one for region, HERFR,and the other for industry,HERFI).We also include as a control variable the size of the bank(SIZE)—that is,the market share of the bank in each period of time.Equation(1)also takes into account the specialization of the bank in collateralized loans,distin-guishing between those offirms(COLFIR)and those of households (COLIND).Finally,ηi is a bankfixed effect to control for idiosyncratic char-acteristics of each bank,constant along time.It might reflect the risk profile of the bank,the way of doing business,etc.εit is a ran-dom error.We estimate model1infirst differences in order to pre-vent from biasing the results due to a possible correlation between unobservable bank characteristics and some of the right-hand-side variables.Given that some of the explanatory variables might be determined at the same time as the left-hand-side variable,we use a GMM estimator(Arellano and Bond1991).All the information from each individual bank comes from the CCR.Table1contains the descriptive statistics of the variables. The period analyzed covers two credit cycles of the Spanish bank-ing sector(from1984to2002),with an aggregate maximum for NPL around1985and,again,in1993.We focus on commercial72International Journal of Central Banking June2006Table1.Descriptive StatisticsVariable Mean St.Dev.Min.Max. NPL it3.945.700.0099.90 GDPG t2.901.51−1.034.83RIR t4.142.90−0.678.12 LOANG i,t−217.3614.37−17.2971.97 LOANG i,t−317.3713.93−13.8067.82 LOANG i,t−417.5414.09−11.1064.68 HERFR it52.6824.8611.2698.87 HERFI it18.479.827.4570.26 COLIND it19.2516.280.0069.91 COLFIR it20.4712.890.0070.35 SIZE it0.591.050.008.79 Note:NPL it is the nonperforming loan ratio—that is,the quotient between nonperforming loans and total loans.GDPG t is the real rate of growth of gross domestic product.RIR t is the real interest rate,calculated as the interbank interest rate less the inflation of the period.LOANG it is the rate of the growth of loans for bank i.HERFR it is the Herfindahl index of bank i in terms of the amount lent to each region.HERFI it is the Herfindahl index of bank i in terms of the amount lent to each industry.COLIND it is the percentage of fully collateralized loans to households over total loans for bank i.COLFIR it is the percentage of fully collateralized loans tofirms over total loans for bank i. SIZE it is the market share of bank i.All variables are shown in percentage points.i denotes the bank and t denotes the year.and savings banks,which represent more than95percent of total assets among credit institutions(only small credit cooperatives and specializedfinancialfirms are left aside).Some outliers have been eliminated in order to avoid the possibility that a small number of observations,with a very low relative weight over the total sample, could bias the results.Thus,we have eliminated those extreme loan growth rates(i.e.,banks with a loan growth rate lower or higher than the5th and95th percentile,respectively).Results appear in thefirst column of table2(labeled“Model1”). As expected,since we takefirst differences of equation(1)and εit is white noise,there isfirst-order residual autocorrelation andVol.2No.2Credit Cycles,Credit Risk,and Prudential Regulation73T a b l e 2.G M M E s t i m a t i o n R e s u l t s o f E q u a t i o n (1)U s i n g D P D (A r e l l a n o a n d B o n d 1991)M o d e l 1M o d e l 2M o d e l 3M o d e l 4V a r i a b l e sC o e ffic i e n tS E C o e ffic i e n t S E C o e ffic i e n t S E C o e ffic i e n tS EN P L i ,t −10.55240.0887***0.55200.0889***0.54990.0841***0.54470.0833***M a c r o e c o n o m i c C h a r a c t e r i s t i c s G D P D t−0.06310.0135***−0.06540.0137***−0.07090.0131***−0.07160.0134***G D P G t −1−0.07710.0217***−0.07700.0220***−0.07500.0212***−0.07770.0209***R I R t0.07100.0194***0.07030.0193***0.07040.0195***0.07110.0192***R I R t −10.02950.0103***0.02920.0103***0.02620.0098***0.02630.0101***B a n kC h a r a c t e r i s t i c s L O A N G i ,t −2−0.00080.0013−0.00080.0013L O A N G i ,t −30.00180.00120.00180.0012L O A N G i ,t −4(α)0.00340.0012***0.00290.0012**|L O A N G i ,t −2−A V E R A G E L O A N G i |0.00040.0017|L O A N G i ,t −3−A V E R A G E L O A N G i |−0.00050.0016|L O A N G i ,t −4−A V E R A G E L O A N G i |(β)0.00250.0019L O A N G i ,t −2−A V E R A G E L O A N G t0.00070.00120.00110.0013L O A N G i ,t −3−A V E R A G E L O A N G t0.00150.00130.00140.0014L O A N G i ,t −4−A V E R A G E L O A N G t (α)0.00250.0013**0.00200.0013(c o n t i n u e d )T a b l e 2(c o n t i n u e d ).G M M E s t i m a t i o n R e s u l t s o f E q u a t i o n (1)U s i n g D P D (A r e l l a n o a n d B o n d 1991)M o d e l 1M o d e l 2M o d e l 3M o d e l 4V a r i a b l e sC o e ffic i e n t S E C o e ffic i e n t S E C o e ffic i e n t S E C o e ffic i e n t S EB a n kC h a r a c t e r i s t i c s (c o n t i n u e d )|L O A N G i ,t −2−A V E R A G E L O A N G t |−0.00260.0018|L O A N G i ,t −3−A V E R A G E L O A N G t |0.00170.0017|L O A N G i ,t −4−A V E R A G E L O A N G t |(β)0.00290.0018H E R F R i t0.02120.0096**0.02090.0097**0.02070.0098**0.02180.0099**H E R F I i t−0.00320.0094−0.00250.0095−0.00380.0098−0.00260.0097C O L F I R i t0.00340.00630.00340.00630.00340.00650.00460.0065C O L I N D i t−0.01250.0072*−0.01250.0072*−0.01410.0073*−0.01410.0074*S I Z E i t0.01990.04820.01530.04860.02130.04750.02610.0484T i m e D u m m i e s N o N o N o N o N o .O b s e r v a t i o n s 868868868868T i m e P e r i o d 1984–20021984–20021984–20021984–2002S a r g a n T e s t [χ(2)138]/p -v a l u e 124.760.78125.560.77123.850.80122.860.82F i r s t -O r d e r A u t o c o r r e l a t i o n (m 1)−5.43−5.37−5.36−5.28S e c o n d -O r d e r A u t o c o r r e l a t i o n (m 2)−1.27−1.4−1.34−1.24T e s t A s y m m e t r i c I m p a c t (p -v a l u e )α+β=0—0.01—0.01α−β=0—0.84—0.73N o t e :S e e n o t e i n t a b l e 1f o r a d e s c r i p t i o n o f t h e v a r i a b l e s .N P L i t ,H E R F R i t ,H E R F I i t ,C O L F I R i t ,a n d C O L I N D i t a r e t r e a t e d a s e n d o g e n o u s u s i n g t h r e e l a g s f o r N P L i t a n d t w o f o r t h e o t h e r s .R o b u s t S E r e p o r t e d .*,**,a n d ***a r e s i g n i fic a n t a t t h e 10p e r c e n t ,5p e r c e n t ,a n d 1p e r c e n t l e v e l s ,r e s p e c t i v e l y .not second order.A Sargan test of validity of instruments is also fully satisfactory.The results of the estimation are robust to heteroskedasticity.Regarding the explanatory variables,there is persistence in the NPL variable.The macroeconomic control variables are both signif-icant and have the expected signs.Thus,the acceleration of GDP, as well as a decline in real interest rates,brings about a decline in problem loans.The impact of interest rates is much more rapid than that of economic activity.The more concentrated the credit port-folio in a region,the higher the problem loan ratio,while industry concentration is not significant.Collateralized loans to households are less risky(10percent level of significance),mainly because these are mortgages that,in Spain,have the lowest credit risk.The para-meter of the collateralized loans tofirms,although positive,is not significant.The size of the bank does not have a significant impact on the problem loan ratio.Finally,regarding the variables that are the focus of our paper, the rate of loan growth lagged four years is positive and significant (at the1percent level).The loan growth rate lagged three years is also positive,although not significant.Therefore,rapid credit growth today results in lower credit standards that,eventually,bring about higher problem loans.The economic impact of the explanatory variables is significant. The long-run elasticity of GDP growth rate,evaluated at the mean of the variables,is−1.19;that is,an increase of1percentage point in the rate of GDP growth(i.e.,GDP grows at3percent instead of at 2percent)decreases the NPL ratio by30.1percent(i.e.,it declines from3.94percent to2.75percent).For interest rates,a100-basis-point increase brings about a rise in the NPL ratio of21.6percent. Regarding loan growth rates,an acceleration of1percent in the growth rate has a long-term impact of a0.7percent higher problem loan ratio.We have performed numerous robustness tests.Model2(the second column of table2)tests for the asymmetric impact of loan expansions and contractions.We augment model1with the absolute value of the difference between the loan credit growth of bank i in year t and its average over time.All model1results hold,but it can be seen that there is some asymmetry:rapid credit growth of a bank (i.e.,above its own average loan growth)increases nonperformingloans,while slow growth(i.e.,below average)has no significant impact on problem loans.12If instead of focusing on credit growth of bank i(either alone or compared to its average growth rate over time),we look at the relative position of bank i in respect to the rest of the banks at a point in time(i.e.,at each year t),wefind that the relative loan growth rate lagged four years still has a positive and significant impact on bank i’s NPL ratio(model3,third column of table2).The parameter of relative credit growth lagged three years is positive but not significant.The rest of the variables keep their sign and significance.Model4(the last column of table2)shows that there is asymmetry in the response of nonperforming loans to credit growth.When banks expand their loan portfolios at a speed above the average of the banking sector,future nonperforming loans increase,while there is no significant effect if the loan growth is below the average.13Finally,the former results are robust to changes in the macroeconomic control variables(not shown).If we substitute time dummies for the change in the GDP growth rate and for the real interest rate,the loan growth rate is still positive and signifi-cant in lag4(although at the10percent level)and,again,positive (although not significant)in lag3.All in all,wefind a robust statistical relationship between rapid credit growth at each bank portfolio and problem loans later on. The lag is around four years,so bank managers and short-term investors(including shareholders)might have incentives to foster credit growth today in order to reap short-term benefits to the expense of long-term bank stakeholders,including depositors,the deposit guarantee fund,and banking supervisors.2.2Probability of Default and Credit GrowthInstead of focusing on bank-aggregated-level credit risk measures,in this section we analyze the probability of default at an individual 12Note that in model1,regression results are the same for the variable rate of growth of loans in bank i at year t as they are for the difference between the for-mer variable and the average rate of growth of loans of bank i along time.That is because the latter term is constant over time for each bank and disappears when we takefirst differences in equation(1).13Note that the relevant test here is to test ifα+β(andα−β)is significant, not each of them alone.loan level and its relation to the cyclical position of the bank credit policy.The hypothesis is that,for the reasons explained in section 1above,those loans granted during credit booms are riskier than those granted when the bank is reining in loan growth.That would pro-vide a rigorous empirical microfoundation for prudential regulatory devises aimed at covering the losses embedded in policies regarding rapid credit growth.In order to test the former hypothesis,we use individual loan data from the CCR.We focus on new loans granted to nonfinancial firms with a maturity larger than one year and keep track of them the following years.We study only financial loans (i.e.,excluding receivables,leasing,etc.),which are 60percent of the total loans to nonfinancial firms in the CCR,granted by commercial and savings banks.The equation estimated isPr(DEFAULT ijt +k =1)=F (θ+α(LOANG it −averageLOANG i )+β LOANG it −averageLOANG i χLOANCHAR iit+δ1DREG i +δ2DIND i +δ3BANKCHAR it +ϕt +ηi ),(2)where we model the probability of default of loan j ,in bank i ,some k years after being granted (i.e.,at t +2,t +3,and t +4)14as a logis-tic function [F (x )=1/(1+exp (−x ))]of the characteristics of that loan (LOANCHAR ),such as its size,maturity (i.e.,between one and three years and more than three years),and collateral (fully collateralized or no collateral);a set of control variables (i.e.,the region where the firm operates,DREG ,and the industry to which the borrower pertains,DIND );and the characteristics of the bank that grants the loan (BANKCHAR ),such as its size and type (i.e.,commercial or savings bank).We also control for macroeconomic characteristics,including time dummies (ϕt ).We do not consider default immediately after the loan is granted (i.e.,in t +1)because it takes time for a bad borrower to reveal as14We consider that a loan is in default when its doubtful part is larger than the 5percent of its total amount.Thus,we exclude from default small arrears,mainly technical,that are sorted out by borrowers in a few days and that,usually,never reach the following month.The level and the evolution of the probability of default (PD)across time and firm size in Spain can be seen in Saurina and Trucharte (2004).On average,large firms (i.e.,those with annual sales above e 50million)have a PD between four and five times lower than that of small and medium-sized enterprises (i.e.,firms with annual turnover below e 50million).。