2007-气候变化与人类演化6

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1.20 MB

- 文档页数:14

地球气候演化小史

地球气候演化史可以分为多个时期,每个时期的气候变化都直接影响着该时期的生物环境和生态系统。

下面是地球气候演化史的简要概述:

1. 古生代(4.6亿年前-

2.5亿年前):气候主要为温暖湿润,大气中二氧化碳含量很高,这是由于海洋中的藻类等植物通过光合作用释放的二氧化碳,导致温室效应增加。

2. 中生代(2.5亿年前-6千万年前):气候逐渐从温暖湿润转向较为干燥。

其中,侏罗纪时期气候比较潮湿,而白垩纪时期则普遍干旱。

3. 新生代(6千万年前至今):冰川时期和间冰川时期交替出现。

其中,新近纪时期的气候变化非常剧烈,既有过渡期间的热带气候,也有冰川期中的极地冰川气候。

而近现代则受工业化和人类活动的影响,大气中的二氧化碳含量呈指数级上升,致使气候变化趋势不可逆转。

地球气候的变迁是一个长期的进化历程,同时也是人类需要深入了解和掌握的重要课题之一。

Science &Technology Vision科技视界0引言气象观测表明,近百年来全球气候呈变暖趋势,地球表面平均气温升高了0.8℃(或1.4o F),并产生了一系列严重后果。

这些引起了世界各国的关注,对于如何应对气候变暖,全球进行了广泛的讨论与大力的研究[1-4]。

为了有效地应对全球气候的变化,首先必须弄清楚全球气候变化的原因,然后再找出有效的对策。

气候的变暖已经确定无疑,且许多人认为这主要是由于人类燃烧化石燃料、砍伐森林等活动造成的[1]。

但是,科学界对此结论仍有争议,以非政府间国际气候变化专门委员会(NIPCC)为代表的许多专家认为自然驱动才是全球气候变化的主要因素,但他们并没有找出具有说服力的自然驱动力[5-6]。

针对全球气候变化的原因众说纷纭、莫衷一是,作者根据现有的研究成果,分析了各种可能引起气候变化的因素,发现随着地球本身及其大气层的演进,地球质量逐渐增加,大气层逐渐增厚,来自宇宙空间和人类产生的温室气体难以逃逸,致使温室效应增强,这也是全球气候变化的一个重要原因。

太阳系中火星、木星等行星的质量也在不断增加,气候变暖的原因类似。

1大气层的形成与演化全球气候变化通常与地球大气层的变化和演进紧密相关,所以研究全球气候变化应该从大气层的形成与演进着手。

地球大气层是地球形成和演化的产物,其演化大致经历了原始大气、次生大气和现在大气三个阶段。

1.1原始大气最初,在地球形成的过程中,地球一边绕着太阳旋转,一边吸附着轨道附近的微尘和气体,使地球质量逐渐增大,大气层逐渐增厚,并在星子的撞击或自转不断加速的原太阳的万有引力的拖曳下渐渐地远离原太阳。

随着地球质量和体积的不断增加,地球内部的热能不断积聚,包括地球高速公转引起的气流摩擦产生的热能,地球自身引力收缩过程产生的热能,原始地球内部化学反应产生的热能。

正是由于地球原始热能积聚到一定程度,才使原始地球物质发生了熔融分异,形成了地球的不同圈层:地核、地幔和地壳。

高三地理全球气候变化对人类活动的影响试题答案及解析1.据2014年3月14日中国之声《新闻和报纸摘要》报道: 近些年来,祁连山雪线正以年均2米到6.5米的速度不断上升,随着冰雪资源不断减少,河西走廊地区面临着巨大的水资源危机。

祁连山地区冰川面积大幅缩减的原因有()①温室气体大量排放②酸性气体的大量排放导致酸雨③臭氧减少紫外线增强④农业生产发展大量引水灌溉⑤过度砍伐森林A.①②③B.②③④C.①③⑤D.①④⑤【答案】C【解析】冰川面积缩减,与温室气体大量排放,导致全球变暖有关,①对。

酸性气体的大量排放导致酸雨,与冰川融化关系不大,②错。

臭氧减少紫外线增强,温度升高,③对。

农业生产发展大量引水灌溉,与冰川融化加快无关,④错。

过度砍伐森林,吸收二氧化碳能力下降,全球变暖,⑤对。

所以C对。

【考点】雪线,全球变暖的原因及影响。

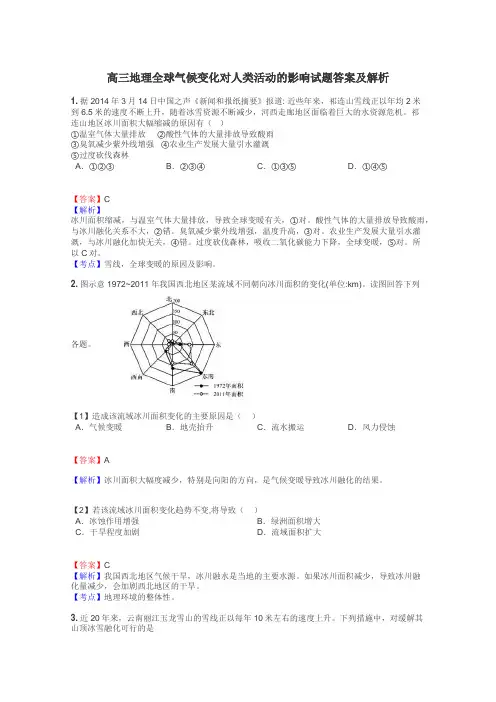

2.图示意1972~2011年我国西北地区某流域不同朝向冰川面积的变化(单位:km)。

读图回答下列各题。

【1】造成该流域冰川面积变化的主要原因是()A.气候变暖B.地壳抬升C.流水搬运D.风力侵蚀【答案】A【解析】冰川面积大幅度减少,特别是向阳的方向,是气候变暖导致冰川融化的结果。

【2】若该流域冰川面积变化趋势不变,将导致()A.冰蚀作用增强B.绿洲面积增大C.干旱程度加剧D.流域面积扩大【答案】C【解析】我国西北地区气候干旱,冰川融水是当地的主要水源。

如果冰川面积减少,导致冰川融化量减少,会加剧西北地区的干旱。

【考点】地理环境的整体性。

3.近20年来,云南丽江玉龙雪山的雪线正以每年10米左右的速度上升。

下列措施中,对缓解其山顶冰雪融化可行的是①禁止游客登山,封山保护冰川;②改善能源结构,利用新能源;③大力植树造林,增加森林面积;④实行人工造雪,增加储冰量;A.①②B.②③C.②④D.③④【答案】B【解析】雪线上升的原因是全球变暖,气温升高,禁止游客登山,封山保护冰川不能缓解气温升高,①错。

气候带知识:气候带变化的历史与趋势气候带是地球表面上一种特殊的自然气候现象,受地球自转和公转的影响,以及地形、土壤、植被和海洋等环境因素的共同作用。

气候带的分布对地球上的生态环境、农业生产和人类生活都有着重要的影响。

气候带的变化历史和趋势反映了地球环境的演化和变迁,也具有重要的科学研究价值。

一、气候带的变化历史气候带的变化历史可以追溯到地球形成后的早期时期。

地球的气候带一直在不断地变化和演化,经历了多次大规模的气候变化事件。

其中最著名的是冰川时期和间冰期的交替周期,这种周期性的气候变化对地球上的生物和自然环境都产生了巨大的影响。

冰川时期是指地球表面上大范围的冰川覆盖,主要发生在高纬度地区和高海拔地区。

冰川时期对气候带的分布产生了显著的影响,使得寒带和温带向赤道方向扩展,热带气候带则受到了一定程度的压缩。

随着冰川时期的结束,气候带的分布也发生了较大的变化,寒带和温带向极地方向收缩,热带气候带则向赤道方向扩展。

间冰期则是冰川时期和冰期之间的温暖时期,气候带的分布也发生了相应的变化。

在间冰期期间,热带气候带向极地方向收缩,而寒带和温带气候带向赤道方向扩展。

这种周期性的气候变化对地球上的生态环境和生物区系都产生了深远的影响,也为人类的迁徙和文明的发展带来了挑战和机遇。

二、气候带的变化趋势当前,地球上的气候带仍然处于不断地变化和演化之中。

受到全球气候变化的影响,地球的气候带正在经历着新一轮的变化和调整。

根据目前的科学研究成果,可以总结出以下几点气候带变化的趋势:1.气候带向极地方向收缩随着全球气候变暖的趋势,寒带和温带气候带向极地方向逐渐收缩。

冰川的融化和冰盖的减少使得寒带和温带气候带的范围逐渐缩小,同时也导致了极地地区的气温上升和气候变暖。

2.热带气候带向赤道方向扩展全球气候变暖导致了热带气候带向赤道方向扩展的趋势。

热带地区的气温升高和降水增加使得热带气候带的范围逐渐扩大,这对于热带地区的生态环境和生物资源都产生了重要的影响。

●第四纪——人类时代1.早期猿人阶段(2百万年-1百75万年前):能人2晚期猿人阶段(1百万年前):直立猿人3早期智人阶段(50万年前):智人4晚期智人(新人)阶段(25万年-3万5千年前):现代人生物大灭绝事件●生物灭绝又叫生物绝种。

它并不总是匀速的,逐渐进行的,经常会有大规模的集群灭绝,即生物大灭绝。

●整科,整目甚至整纲的生物在可以很短的时间内彻底消失或仅有极少数残存下来。

●却总有其它一些类群幸免于难,还有一些类群从此诞生或开始繁盛。

●大规模的集群灭绝有一定的周期性,大约6200万年就会发生一次,但集群灭绝对动物的影响最大。

●陆生植物的集群灭绝不象动物那样显著。

第一次生物大灭绝:●时间:为距今4.4亿年前的奥陶纪末期。

事件:导致大约85%的物种绝灭。

●是地球史上第三大的物种灭绝事件,约85%的物种灭亡。

●古生物学家认为这次物种灭绝是由全球气候变冷造成的。

在大约4.4亿年前,现在的撒哈拉所在的陆地曾经位于南极,当陆地汇集在极点附近时,容易造成厚厚的积冰---奥陶纪正是这种情形。

大片的冰川使洋流和大气环流变冷,整个地球的温度下降了,冰川锁住了水,海平面也降低了,原先丰富的沿海生态系统被破坏了,导致了85%的物种灭绝。

第二次生物大灭绝:又称:第二次物种大灭绝,泥盆纪大灭绝●时间:距今3.65亿年前的泥盆纪后期。

事件:海洋生物遭受了灭顶之灾。

●对古气候的研究显示泥盆纪时期是温暖的。

●第二次物种大灭绝发生在泥盆纪晚期,其原因也是地球气候变冷和海洋退却。

●在距今约3.65万年前的泥盆纪后期,历经两个高峰,中间间隔100万年,是地球史上第四大的物种灭绝事件,海洋生物遭到重创。

第三次生物大灭绝:又称:第三次物种大灭绝、二叠纪大灭绝时间:距今2.5亿年前的二叠纪末期….事件:导致超过95%的地球生物灭绝●这次大灭绝是由气候突变、沙漠范围扩大、火山爆发等一系列原因造成。

●陨石撞击、气候变化、大气成分改变、火山活动、沙漠肆虐第四次生物大灭绝:又称:三叠纪大灭绝,第四次物种大灭绝时间:距今2亿年前的三叠纪晚期。

人类活动对气候变化的影响人与自然的关系,自古至今一直以无穷的魔力吸引众多的科学家、哲学家、政治思想家乃至文学艺术家。

无论是古代“天人合一”观还是现代“回归自然“论,无不倡导人类与自然的协合统一、人与环境密不可分的鱼水之情。

但是,本世纪以来,伴随世界经济迅速发展、人口爆炸性增长、资源过度开发、能源需求量大增,不仅导致全球性的资源匮乏、环境污染、生态失衡,而且使大气二氧化碳、甲烷、一氧化碳等温室气体含量猛增,引发了诸如气候变暖等环境效应,使气候变化问题不得不从学术论坛搬进地球首脑会议的“大雅之堂”。

而从“李崇银院士谈人类活动与气候变化”中有新的较为充足的证据表明:过去50年的气候变暖是由人类活动造成的。

这让我对灾害频发生由天更怨人这一观点有了更深的认识。

也更表明了人类活动对气候变化的影响一直都存在并日益严重。

最初,主要表现在由于人类活动影响了下垫面的面貌,改变了下垫面的粗糙度、反射率和水热平衡等方面,从而引起局部地区气候的变化,随着人类社会的发展,其影响的广度和深度日益增加,人类活动的影响就日益重要。

人类的各种各样的生产和生活活动,增加了全球大气的污染,影响了地球大气对太阳辐射能的反射和散射作用,减弱了入射的太阳辐射数量,从而导致气温的降低。

科学家利用气候模式研究气候变化的成因时,首先模拟了过去100年仅受“自然”影响的气候变化,如太阳辐射的变化和大规模火山爆发,然后再将人类活动引起的温室气体和气溶胶浓度增加因素加进去,对气候进行模拟运算。

这些试验结果让人震惊:只包括自然作用的模式无法解释20世纪中期以来观测到的全球变暖现象,只有加入了人为因素,才可以很好地解释观测事实。

至于温度的长期变化模式,也只有考虑了所有的效应之后,模拟结果才与观测事实最为一致。

有两种气候变化类型提供了人类影响的证据。

第一个是陆地比海洋升温明显,海洋表层比深层升温明显。

这与温室气体弥漫在大气中引起的升温形式一致:因为海洋的热惯量(thermal inertia)大、增温慢。

化石新知考古探谜8化 石2019年第1期9化 石2019年 第1期然是人类进化过程中的“自我”表现,但也是环境变化的产物。

相关研究显示,在气候适宜时期(间冰期),伴随着人口的增长,古人类会扩大自己的生存范围,并重新占据以往由于气候恶劣而被他们舍弃的生存空间。

当寒冷气候(冰期)来临,他们的生存范围会随着冰盖的扩大而向南退缩,并伴随着对部分生存空间的舍弃和部分人群的灭绝。

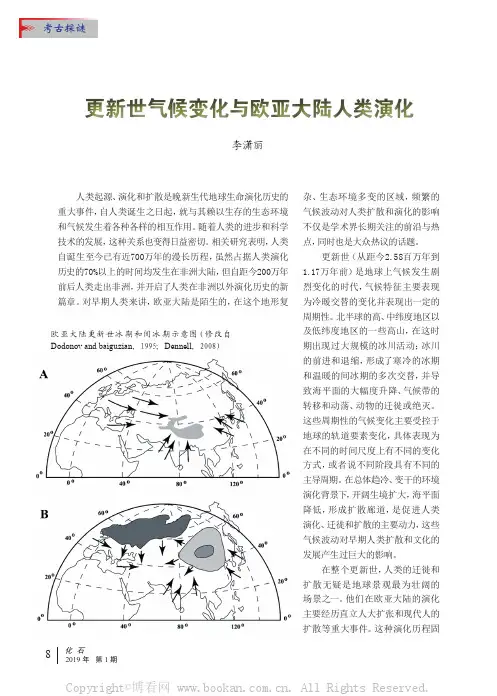

有证据表明,在更新世,至少有六个关键的气候演化阶段与欧亚大陆早期人类的扩散和行为发展存在密切联系。

1. 1.8~1.6百万年前的气候转型期:进入更新世后,北半球陆冰加速积累,非洲大陆朝干旱化方向发展,欧亚大陆中东部典型黄土开始堆积。

在距今1.8至1.6百万年前,气候发生转型,大区域甚至全球性气候和环境也发生了重要的转变,气候特征从以前的较复杂多周期转变为以4.1万年较为稳定的周期为主。

在非洲,粉尘堆积显著增加,指示非洲大陆干旱程度进一步增加;欧洲陆冰聚集,气候干冷;在中国,黄土地层的风化程度指示了气候进一步趋于干旱。

作为人类起源地的非洲地区降水量总体上趋于减少,草原扩张。

在该阶段直立人或匠人(Homo erectus /Homo ergaster )出现,与早期的人科成员-南方古猿(Australopithecus )和能人(H. hablis )相比,直立人除脑量增加外,还拥有较大的体型和较为进步的生存技能;因此,直立人的出现可能为这次迁徙提供了生理基础。

在该阶段人类开始首次走出非洲扩散至亚洲的中低纬度热带-亚热带地区,比如在欧亚大陆交界地带的高加索地区(格鲁吉亚的Dmanisi )、东南亚(印度尼西亚的Java )、中国的元谋、蓝田以及泥河湾盆地均发现了直立人化石或文化遗物。

在该时期,由于高纬更新世气候变化与欧亚大陆人类演化关系(修改自Head et al ., 2008)度和寒冷气候的影响,欧洲大陆尚未发现人类生存的证据。

虽然此阶段在非洲出现了进步的以手斧、薄刃斧等为标志的模式2(Acheulean)工业,但早期人类扩散至亚洲大陆,仍然选择相对简单的模式1(Oldowan)工业的简单石核-石片类型,以此权益的策略来应对多变而陌生的生态环境。

地理环境变迁:气候变化与地球演变引言大自然是一个变幻莫测的奇妙世界,我们生活的地球也在不断的变迁中。

地理环境的变迁是地球演变的重要体现,其中气候变化是最为重要的因素之一。

气候变化不仅影响着人类的生活和发展,而且对地球的演变也产生了深远的影响。

本文将探讨气候变化与地球演变之间的关系,并着重讨论气候变化对地球的影响。

气候变化与地球演变的联系气候变化是地球演变的重要表现之一。

地球上的气候是在长期演化过程中形成的,受到多种因素的综合影响。

其中,气候系统的变化对地球的演变具有重要影响。

1.气候变化的原因气候变化是由多种因素引起的,包括自然因素和人为因素。

自然因素主要包括太阳辐射的变化、地球自转和倾斜角度的改变等;而人为因素主要是由于人类活动导致的温室气体排放增加和森林砍伐等。

2.气候变化对地球的影响气候变化对地球的影响是十分复杂和深远的。

首先,气候变化对生态环境产生重要影响,如气候变暖导致的冰川融化和海平面上升等。

其次,气候变化还会影响陆地的水文循环和水资源分布,导致干旱和洪涝等问题。

此外,气候变化还会导致生物多样性减少和物种灭绝等生物灾害。

气候变化对地球的具体影响气候变化对地球的具体影响主要表现在以下几个方面:1.冰川融化与海平面上升气候变暖导致冰川融化加剧,进而导致海平面上升。

冰川融化不仅会带来供水紧张的问题,还会导致海岸线退缩和海洋生态系统的改变。

海平面上升则对沿海城市和岛屿造成了重要威胁。

2.气候变化与动植物分布气候的变化会改变地球上动植物的分布格局。

一些物种可能会因为气候的变暖而向北或向高山迁移,而另一些物种则由于环境变化而灭绝。

这会对生态平衡产生重要影响。

3.气候变化与自然灾害气候变化也会增加自然灾害的频率和强度。

例如,气候变暖会导致干旱和森林火灾的加剧,而极端天气事件如飓风和暴雨也会变得更加频繁和剧烈。

这些自然灾害给人类的生命财产安全带来了巨大威胁。

4.气候变化与生物多样性气候变化也对地球上的生物多样性造成了影响。

全球气候变化原因及对人类生存带来的影响(东北师范大学城市与环境科学学院,吉林长春)摘要:气候环境是人类生存的重要环境。

气候变化已成为近年来人们最关注的环境问题之一。

本文分析了全球气候变化的原因,阐述了气候变化的表现,以及给人类生存带来的影响。

关键词:全球气候变化;变化;原因;影响国际 1765-2100年间的气候变化。

图表引用IPCC的第三次评估报告,展示过去及预测未来的气温变化。

本图来自绿色和平网根据近100多年全球气温资料分析,全球平均地面温度已升高0.3—0.6℃,其中11个最暖的年份发生在80年代中期以后,全球变暖现象已成为科学界和整个人类面临的一个事实。

一、全球气候问题的内涵全球气候问题主要指全球气候变暖问题。

从定义上来看,全球气候变化是指在全球范围内,气候平均状态统计学意义上的巨大改变或者持续较长一段时间(典型的为10年或更长)的气候变动。

气候变化的原因可能是自然的内部进程,或是外部强迫,或者是人为地持续对大气组成成分和土地利用的改变[1]。

科学研究表明,地球的温度和气候是行星能量平衡的副产品。

温室气体吸收了一部分发散的红外线,防止它直接进入太空,改变了地球表面的热量平衡并导致气候变暖。

这个过程被称为“温室效应”(Greenhouse effect)。

庞大的天然的温室效应的存在,对于地球上的生命而言是至关重要的。

水蒸气、二氧化碳和其他温室气体在大气中自然地发生作用,使地球表面的平均气温保持在34℃左右。

全球变暖现象是指由于人为的温室气体排放量强化了这种天然的温室效应,使地球不再像以前那样适宜于人类和自然界的生存[2]。

工业革命以来,人类焚烧了大量的化石燃料充当能源,这些燃料以碳为主要构成,燃烧时氧化生成二氧化碳。

据统计,目前有超过3/4的净二氧化碳排放量来自化石燃料的燃烧。

因此,解决全球变暖问题从本质上等同于减少世界能源体系中的碳。

除去大气中人为的二氧化碳排放量,需要一个漫长的过程,而与此同时,二氧化碳的整体排放量有增无减,这使得大气中的二氧化碳浓度稳步升高。

气候变化与人类生活:探究气候变化对我们的影响引言气候变化已经成为当今世界面临的最大挑战之一。

随着全球变暖的加剧,人类生活也受到了越来越多的影响。

气候变化不仅对我们的自然环境产生了巨大的影响,也对我们的日常生活带来了许多变化。

本文将探讨气候变化对我们的影响,并讨论如何应对这些挑战。

1. 新的气候模式气候变化已经改变了全球的气候模式。

过去的几十年中,我们经历了更频繁的极端天气事件,如干旱、洪水和飓风。

这些极端天气事件对我们的生活产生了直接影响。

例如,干旱导致农作物歉收,引发粮食危机;洪水造成房屋损坏和人员伤亡;飓风带来巨大的破坏力,损失了许多城市的基础设施。

因此,我们必须适应这种新的气候模式,并制定适应性策略,以减轻灾害造成的影响。

2. 自然资源的稳定性气候变化对自然资源的稳定性产生了负面影响。

全球变暖导致冰川消融和海平面上升,这威胁到了世界各地的淡水资源。

在许多地区,干旱已经成为常态,导致水资源短缺。

此外,气候变化还导致了生物多样性的减少,这对人类的生活和生计产生了直接影响。

例如,某些物种的灭绝可能导致食物链的破坏,影响人类的粮食供应。

因此,我们必须保护自然资源,并采取措施来适应气候变化所带来的挑战。

3. 农业与粮食安全气候变化对农业和粮食安全造成了威胁。

全球变暖导致农作物的生长受到不利影响,如降雨不足和温度变化。

这导致了农作物歉收和粮食供应不足的问题。

农民们必须寻找新的农业方法和适应策略来保证粮食的生产和供应。

此外,气候变化还增加了农作物病虫害的传播风险,这对农业生产造成了更大的威胁。

因此,我们需要投资并支持可持续的农业实践,以确保粮食的安全供应。

4. 城市化与城市规划气候变化对城市化和城市规划带来了新的挑战。

全球城市化的不断加速导致了更多的碳排放和能源消耗。

为了应对气候变化,我们需要改变城市规划的方式,使城市能够更加可持续和环保。

例如,我们可以在城市中建设更多的绿色空间和公共交通系统,以降低碳排放和能源消耗。

高一地理全球气候变化对人类活动的影响试题的增长示意图”并回答下列问题。

1.分析“近年来大气中CO2增长的曲线是 _______________。

(1)图中代表近年来CO2平均每年增加_____________(ppm)。

(2)计算一下1958~1968年十年间CO2(3)为什么大气中CO的含量与日俱增?2的增多对气候有何影响?(4)大气中CO2(5)列举一、二项事例说明由于CO的增多,使气候发生变化所带来的后果。

2【答案】(1)C(2)0.7,加上森林大量(3)由于工厂、交通工具、家庭炉灶大量燃烧煤、石油和天然气,排放大量CO2被砍伐所致。

(4)全球气候有变暖趋势。

(5)两极冰川融化,引起海平面上升。

引起各地降水和干湿状况发生变化。

如现在温带由于气温升高,耕作业发达的地区将会退化成草原;干旱的地区将变得更加干旱;亚寒带某些地区则因气温升高,将会适应温带作物的生长。

(任答2点)【解析】第(1)题,近150年来大气中二氧化碳含量的变化趋势不断上升,尤其是1950年以来,上升更为明显,由图可以看出,C曲线符合。

第(2)题,由图可知:1958~1968年十年间CO2平均每年增加(318-311)/10=0.7pmm。

第(3)题,大气中二氧化碳升高的原因有:一是人类大量燃烧煤、石油、天然气等矿物燃料,排放出大量二氧化碳气体。

二是毁林,尤其是热带雨林的破坏。

第(4)题,据图分析:近150年来,全球气温变化趋势波动上升。

与空气中二氧化碳含量的关系是:人类活动排放到大气中的二氧化碳气体强烈吸收地面红外线长波辐射而升温。

大气中CO2的增多会加剧全球气候变暖趋势。

第(5)题,全球气候变暖带来的影响主要体现在导致生态系统的调整;导致海平面上升;可能导致干旱、洪涝、暴雨等灾害事件的增加;对人类健康的威胁会增加等方面。

2.阅读下面一段材料,分析回答(13分):喜马拉雅地区总共有1.5万条冰川,除两极地区的冰冠外,这些冰川是世界上冰体最大的组成部分。

中学地理教学优秀教案——气候变化与人类活动的关系解析与思考气候变化与人类活动的关系解析与思考地理教学中的气候变化与人类活动的关系是一个重要的教学内容,它直接关系到学生对于环境问题的认知和对未来可持续发展的思考。

本文将从解析气候变化与人类活动的关系以及相关的案例分析,进而引发学生的思考和讨论。

一、气候变化与人类活动的关系解析1. 气候变化的原因气候变化是地球自然变化的一部分,但目前的气候变化速度明显加快,主要是因为人类活动的影响。

人类活动引起的主要气候变化包括温室气体排放、土地利用变化和化学物质的排放等。

2. 温室效应与温室气体温室效应是指地球表面受到太阳辐射后,一部分被大气层吸收并重新辐射回地表,导致地球表面温度升高的过程。

温室气体主要包括二氧化碳、甲烷和氧化亚氮等。

人类活动通过燃烧化石燃料、森林砍伐等方式增加了温室气体的排放,进一步加强了温室效应。

3. 气候变化的影响气候变化对地球生态系统、社会经济和人类健康产生了广泛的影响。

例如,全球气温上升导致冰川消融,引起海平面上升、洪灾和干旱等极端天气事件的增加;海洋酸化威胁珊瑚礁和海洋生物的生存;农作物受灾、食物安全问题等。

这些影响将对人类社会造成巨大的挑战, 同时也需要我们采取行动应对气候变化。

二、案例分析1. 案例一:极地冰川融化近几十年来,南极洲和格陵兰的冰川消融速度加快,给全球海平面上升带来巨大压力。

这主要是因为全球温度上升导致冰架融化和冰川退缩。

冰川融化会导致海洋酸化、海岸线退缩等问题,进一步影响生态系统和人类社会的可持续发展。

2. 案例二:碳排放与气候变化过去几十年来,世界各国的碳排放量迅速增加,导致全球温室气体浓度升高。

温室气体的增加引发了全球变暖和极端天气事件的频繁发生,如干旱、洪灾、飓风等。

这些事件不仅造成了巨大的经济损失,还威胁到人们的生活和安全。

三、思考与讨论1. 行动起来面对气候变化,我们不能袖手旁观,而是应该采取积极的行动。

Paleogeographic variations of pedogenic carbonate d 13C values from Koobi Fora,Kenya:implications for floral compositionsof Plio-Pleistocene hominin environmentsRhonda L.Quinn a ,b ,*,Christopher J.Lepre a ,James D.Wright b ,Craig S.Feibel a ,ba Department of Anthropology,Rutgers University,131George Street,New Brunswick,NJ 08901,USA bDepartment of Geological Sciences,Rutgers University,610Taylor Road,Piscataway,NJ 08854,USAReceived 4November 2005;accepted 22January 2007AbstractPlio-Pleistocene East African grassland expansion and faunal macroevolution,including that of our own lineage,are attributed to global climate change.To further understand environmental factors of early hominin evolution,we reconstruct the paleogeographic distribution of veg-etation (C 3-C 4pathways)by stable carbon isotope (d 13C)analysis of pedogenic carbonates from the Plio-Pleistocene Koobi Fora region,north-east Lake Turkana Basin,Kenya.We analyzed 202nodules (530measurements)from ten paleontological/archaeological collecting areas spanning environments over a 50-km 2area.We compared results across subregions in evolving fluviolacustrine depositional environments in the Koobi Fora Formation from 2.0e 1.5Ma,a stratigraphic interval that temporally brackets grassland ascendancy in East Africa.Significant differences in d 13C values between subregions are explained by paleogeographic controls on floral composition and distribution.Our results indicate grassland expansion between 2.0and 1.75Ma,coincident with major shifts in basin-wide sedimentation and hydrology.Hypotheses may be correct in linking Plio-Pleistocene hominin evolution to environmental changes from global climate;however,based on our results,we interpret complexity from proximate forces that mitigated basin evolution.An w 2.5Ma tectonic event in southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya exerted strong effects on paleography in the Turkana Basin from 2.0e 1.5Ma,contributing to the shift from a closed,lacustrine basin to one dominated by open,fluvial conditions.We propose basin transformation decreased residence time for Omo River water and ex-panded subaerial floodplain landscapes,ultimately leading to reduced proportions of wooded floras and the establishment of habitats suitable for grassland communities.Ó2007Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.Keywords:Paleogeography;Savannas;East Africa;Carbon isotopesIntroductionGlobal climate is often elected as a catalyst for environmen-tal changes acting as selective pressures on Plio-Pleistocene African hominins (Stanley,1992;Vrba,1995,1999;deMeno-cal,2004).Habitat theory of Vrba (1992)and variability selec-tion hypothesis of Potts (1998)credit mammalian evolutionary pattern and process to climate change.Feibel (1999:276)argues the need for a middle ground,tethering the ‘‘global-scale climatic phenomena’’to ‘‘environmental change,habitat shift,and biotic evolution’’,and offers the sedimentary basin as a scale for analysis.Environments within individual basins re-spond to climate with different sensitivities and thresholds influenced by basin size,topography,depositional and tectonic regime,and water availability (Carroll and Bohacs,1999;Withjack et al.,2002).Stable carbon isotope (d 13C)records from pedogenic car-bonates are interpreted as reflecting the spread of C 4grasses in East Africa beginning as early as the Miocene (Cerling,1992).From these data,environmental change and increased*Corresponding author.E-mail address:rlquinn@ (R.L.Quinn).0047-2484/$-see front matter Ó2007Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.01.013Journal of Human Evolution 53(2007)560e573aridity associated with global climate are temporally corre-lated with faunal macroevolution including the branching pat-tern of the hominin lineage and the origins of genus Homo(see review in deMenocal,2004).Unlike proxies of global climate from the marine realm,pedogenic carbonate isotopes offer di-rect and local environmental information from the habitats of hominins and other members of the mammalian community. Isotopic studies of pedogenic carbonates in the Turkana Basin have interpreted terrestrial East Africa as responsive to global climate over approximately the last four million years(Cerling et al.,1988;Wynn,2004).Here we employ stable isotopic values of paleosol carbonates from hominin-bearing sediment in the Koobi Fora region of the basin to examine paleoenvir-onmental change.We focus on the interval2.0e1.5Ma,which brackets a marked shift in aridity(Wynn,2004)and the ap-pearance of early African Homo erectus in the area(Anto´n and Swisher,2004;Wood and Strait,2004).We enlarge the current database to place our isotopic measures offloral com-munity structure into a paleogeographic framework and inte-grate climatic and tectonic influences on a basin-wide scale. Study regionGeographic settingThe Turkana Basin of northern Kenya and southern Ethio-pia lies within the eastern branch(or Gregory Rift)of the East African Rift System between the Kenyan and Ethiopian domes (Ebinger et al.,2000).The basin presently contains one of the largest rift lakes,Lake Turkana,with an area of7,500km2 (Frostick,1997).Today,the lake is a saline-alkaline and closed-basin lake that receives over90%of its water from rainfall over the Ethiopian Highlands,via the Omo River (Fig.1),with minor inputs from the Turkwell and Kerio River systems(Yuretich,1979).The general climate within this rift bottom setting is arid to semi-arid and receives250e 500mm of rainfall annually(Nicholson,1996).Bushland grasslands dominate the landscape,with gallery forests clus-tered along perennial and ephemeral river channels(Lind and Morrison,1974).The Koobi Fora region,situated within the northeast Tur-kana Basin of Kenya(Fig.1),is one of the richest fossil and archaeological localities in East Africa(Leakey and Leakey, 1978;Isaac and Isaac,1997).Plio-Pleistocene sediments ex-posed in the region are attributed to the Koobi Fora Formation (Brown and Feibel,1986),which preserves a record of homi-nin evolution and environmental change for the period w4.0e 1.0Ma(Feibel et al.,1989,1991;Brown and Feibel,1991). Lake Turkana constrains the western margin of the Koobi Fora Formation,while Miocene-Pliocene volcanics to the west define the eastern border(Watkins,1986).The formation is exposed in geographic subregions of the Koobi Fora region, including Ileret,Il Dura,Karari Ridge,and Koobi Fora Ridge (Fig.2A),which are segregated into numbered paleontological and archaeological collecting areas(Fig.1).The extensive geographic exposure of the Koobi Fora Formation,and its well-documented stratigraphy and geochronology,affords reconstruction of a range of habitats across paleolandscapes at discrete temporal intervals.Stratigraphy and paleogeographyAlthough outcrops of the Koobi Fora Formation are discon-tinuous,stratigraphic control has been determined by radiomet-rically dated and correlated tuffs,aerially extensive bioclastic lacustrine marker beds,and an established geomagnetic polar-ity stratigraphy(McDougall,1985;Brown and Feibel,1986, 1991;Hillhouse et al.,1986;Feibel et al.,1989;McDougall et al.,1992;Brown et al.,2006;McDougall and Brown, 2006;Fig.3).Here we focus on the upper Burgi,KBS,and lower Okote Members of the formation,approximately repre-senting the period between 2.0and 1.5Ma(McDougall, 1985;Brown and Feibel,1986,1991:*Age of Lorenyang Tuff is approximated by sedimentation rate(scaledage). Fig.1.Location map of Lake Turkana and the Koobi Fora Formation(stippled area).Inset map shows shaded collecting areas used in this study(after Brown and Feibel,1991;Feibel et al.,1991;Feibel,1999).561R.L.Quinn et al./Journal of Human Evolution53(2007)560e573Fig.2.Paleogeographic reconstructions of the Koobi Fora Formation between 2.0and 1.5Ma (after Feibel,1988;Feibel et al.,1991;Rogers et al.,1994).A)Modern paleogeography,basemap area equals approximately 50km 2(after Isaac and Behrensmeyer,1997).B)Paleogeography at 1.7e 1.5Ma.C)Paleogeography at 1.8e 1.7Ma.D)Paleogeography at 1.9e 1.8Ma.E)Paleogeography at 2.0e 1.9Ma.562R.L.Quinn et al./Journal of Human Evolution 53(2007)560e 573Sedimentation of these members is inferred to be largely con-tinuous,except for an unconformity (w 500,000-year deposi-tional pause)in the upper portion of the Burgi Member (Fig.4)and the background hiatuses inherent to the sedimenta-tion of the fluviolacustrine environments (Brown and Feibel,1986;Feibel et al.,1989,1991).A large lake formed in the Turkana Basin at about 2.0Ma,as indicated by the widespread occurrence of lacustrine and asso-ciated facies just above the upper Burgi Member unconformity (Brown and Feibel,1991).This precursor of Lake Turkana,Lake Lorenyang (Fig.2E),occupied an area of approximately 9,000km 2,mainly fed by an ancestor of the modern Omo River (Feibel et al.,1991;Feibel,1997).The deposition of the Lorenyang and KBS Tuffs in a deltaic facies (Feibel,1988)suggests that the ancestral Omo River delta began prograding into the Koobi Fora region by about 1.9Ma (Brown and Feibel,1991;Fig.2D).The river coursed through the region as indicated by fluvial channel and flood-plain facies just above the stratigraphic level of the KBS Tuff (White et al.,1981).Channel and floodplain deposits are more widespread within the upper part of the Olduvai Subchron,suggesting an increase in the prevalence of ancestral Omo River environments at Koobi Fora near 1.8e 1.7Ma (Feibel et al.,1989;Brown and Feibel,1991;McDougall et al.,1992).Additional channel systems em-anated from the highlands along the northeastern basin margin at this time (Feibel et al.,1991).The Omo River and basin margin channels emptied into a shallow lake margin/series of lake margins,over which there were frequent transgressions and regressions (Feibel et al.,1991;Feibel,1994;Fig.2C).After about 1.7Ma,lake-related depositional environments were virtually absent from the region,except for a few shal-low,aerially restricted,and transient examples (Brown and Feibel,1991;Fig.2B).For the majority of the period between 1.7and 1.4Ma,the main (axial)channels of the ancestral Omo were not readily active in the study area,rather the landscape was occupied by smaller distributaries that either derived from the main channel or from the northeastern margin of the basin (Feibel et al.,1991;Fig.2B).These distributaries were respon-sible for the deposition of a series of correlative marker tuffs,referred to as the Okote Tuff Complex,Koobi Fora Tuff Com-plex,and Ileret Tuff,which have an age near 1.6e 1.5Ma (Brown and Feibel,1985,1986;Brown et al.,2006;McDou-gall and Brown,2006).Large river channels,attributed to the ancestral Omo,reclaimed the Koobi Fora region near early Chari Member times,w 1.4Ma (Brown and Feibel,1991).East African and Turkana Basin paleoenvironmentsMany studies attribute a marked increase in East African aridity and grassland expansion between 2.0and 1.5Ma to causes derived from global climate change (reviewed in deMe-nocal,2004).Increased terrigenous sediment inputs,ca.1.7Ma,from the northern low-latitude areas of continental Africa (deMenocal and Bloemendal,1995)have been linked with an intensification of Northern Hemisphere Glaciation at w 1.8Ma (e.g.,Shackleton et al.,1990;Shackleton,1995).posite stratigraphic sections of Koobi Fora Formation by subre-gions with radiometric ages of tuffs (after Brown and Feibel,1991;McDougall and Brown,2006).563R.L.Quinn et al./Journal of Human Evolution 53(2007)560e 573Indications of a response to high-latitude glacial conditions are found in marine pollen records from off the coast of northwest Africa,which show wooded savanna to desert vegetation zones appearing around 2.6e 2.4Ma and dominating by 1.8Ma (Le-roy and Dupont,1994).East African palynological evidence suggests drier conditions in rift valley lowlands at 2.35Ma and an intensification of aridity at around 1.8Ma (Bonnefille,1995).East and South African mammalian species abundances show a shift to more arid-adapted fauna culminating at 1.8Ma (e.g.,Vrba,1995;Reed,1997).Pedogenic carbonate isotope re-cords amassed from several Plio-Pleistocene East African lo-calities also display aridification with increased proportions of C 4grasses and heightened evaporation of soil water or change in isotopic composition of rainfall (Cerling,1992;Levin et al.,2004;Wynn,2004).Other researchers,however,have found ambiguous or con-trasting records of East African paleoenvironments.Kingston and others (1994)found no significant change in vegetation from the Baringo Basin,but a persistent mosaic environment over the last 15Ma.Plio-Pleistocene vegetation at Olduvai Gorge had a significant amount of wooded vegetation (Sikes,1994).Trauth et al.(2005,2007)have suggested the presence of a humid period within the general pattern of East African aridification indicated by the formation of large lakes circa 1.9e 1.7Ma.Suids found in South and East African hominin localities maintain postcranial morphologies for closed and in-termediate habitats (Bishop,1999).Within the Turkana Basin,contrasting and complex proxy records also confound environmental interpretations.Mamma-lian species abundances show a gradual shift to more arid-adapted fauna from 2.5to 1.8Ma rather than a ‘‘turnover pulse’’coinciding with glacial intensification (Behrensmeyer et al.,1997).Additional studies on the same dataset proposed a series of pulses occurring at periods of 100,000years (Bobe and Behrensmeyer,2004).Palynological evidence indicatesthat grass species dominated from lake and delta environments at 2.0Ma (Bonnefille and Vincens,1985);however,cooler and more humid conditions have been interpreted in areas of the basin by the presence of highland and riverine pollen species (Bonnefille,1976).Cerling and others (1988)and Wynn (2000)demonstrated tropical grass expansion in the Turkana Basin over the last 4.3Ma,with marked aridity events during the intervals between 3.58e 3.35, 2.52e 2.00,and 1.81e 1.58Ma.However,Wynn’s (2004:his figure 2B)compilation illustrated a mean value trending toward wooded vegetation between 1.8e 1.5Ma.Wynn (2004)also reported a general ari-dification trend with increasingly shallower calcic horizon depths in Turkana Basin paleosols,although he found an ex-cursion to a humid period between 1.9and 1.8Ma with depth to calcic horizon estimates.Materials and methodsStable carbon isotopes (d 13C)of pedogenic carbonates The C 3(Calvin-Benson)and C 4(Hatch-Slack)photosyn-thetic pathways have distinct differences in the fractionation of carbon isotopes (see Ehleringer,1989).Woodland vegeta-tion (trees,shrubs,temperate grasses)utilizing the C 3pathway discriminate against the heavier and kinetically slower isotope of carbon,13C;whereas tropical grasses using the C 4pathway also discriminate but allow the inclusion of more 13C into tis-sues than do C 3flora.Since most low-latitude grasses use the C 4pathway,East African vegetation shows a clear separation in d 13C values (C 3:À31.4to À24.6&,C 4:À14.1to À11.5&;Cerling et al.,2003).Following soil gas diffusion models of Cerling (1984)and Cerling and Quade (1993)and the conditions of respiration rates developed by Quade et al.(1989),pedogenic carbonates at depths greater than 30cm in soils with relativelyhighFig.4.Sedimentation rates and depositional hiatuses for the Koobi Fora Formation throughout its depositional history (after Feibel,1988).564R.L.Quinn et al./Journal of Human Evolution 53(2007)560e 573respiration rates incorporate CO2of decaying organic matter derived from surface vegetation during soil development. d13C values of pedogenic carbonates from the savanna biome are intermediate between the C3-C4end members and reflect the percentage of grasses versus woody vegetation present on the land surface with an isotopic fractionation between13.5e 16.6&(Cerling and Quade,1993).Pedogenic carbonates form under a negative water budget in regions with rainfall be-low100cm/yr during periods averaging hundreds to thousands of years(Jenny,1941,1980;Birkeland,1984;Srivastava, 2001).Fossil soils preserved in the Plio-Pleistocene Koobi Fora Formation are dominated by paleovertisols,formed under a dry season of four or more months and250e1,000mm of annual moisture(Feibel,1988;Wynn,2000,2004).Soil carbonate sampling strategy and analysisWe examined pedogenic carbonate isotope(d13C)values from paleosols to reconstruct geographic distribution of vege-tation(C3-C4pathways)through time to assess the nature, timing,and controls on paleoenvironmental change in homi-nin-associated habitats of Koobi Fora.We compared lake-margin,riverfloodplain,and distributary channelfloodplain depositional landscapes for the period of w2.0e1.5Ma that temporally brackets grassland ascendancy in East Africa as documented in Wynn’s(2004)third C4expansion event.We enhanced the previous isotopic studies of pedogenic carbon-ates from the Turkana Basin(Cerling et al.,1988;Wynn, 2004)for the2.0e1.5Ma time interval by:1)increasing the sample size(nodules,n¼202;analyses,n¼530),and2)con-ducting widespread sampling of synchronous lateral horizons in the Koobi Fora Formation.This lateral sampling approach has been suggested for attaining ecotonal variability and hab-itat gradient(e.g.,Kingston et al.,1994;Levin et al.,2004; Wynn,2004).With attention to paleohydrology(after Levin et al.,2004),we partitioned the northeast Turkana Basin as subregions by proximity to precursors of Lake Turkana and to the ancestral Omo River system,which was the main con-trol of basin-wide hydrology and deposition during the Plio-Pleistocene(e.g.,Feibel et al.,1991).Our study interval begins with the upper Burgi Member (2.0to1.9Ma),spans the entire KBS Member(1.9to1.6e 1.5Ma),and ends with the lower portion of the Okote Member [1.6e1.5Ma(e.g.,Brown and Feibel,1986,1991;McDougall and Brown,2006)].We sampled exposures from collecting area1a in the Ileret subregion,area41in the Il Dura subre-gion,areas101,102,103,and104along the Koobi Fora Ridge,and areas105,130,131,and133on the Karari Ridge (Fig.1).Our study covers approximately50km2in total area of exposure and examines evolving paleolandscapes along lake-margin areas andfloodplain areas.The Koobi Fora Ridge and Karari Ridge span three and four of the environments through time,respectively,whereas the Il Dura and Ileret sub-regions only record one depositional regime(Fig.2B e E).Age control of pedogenic carbonate samples was deter-mined with the established chronostratigraphic framework and scaled with sedimentation rates for each subregion.For example,with the KBS Tuff dated to1.87Ma(McDougall and Brown,2006)and an average sedimentation rate of the Karari Escarpment determined as6.2cm/kyr(Feibel,1988), we calculated a fossil soil locatedfive meters above the KBS Tuff in collecting Area105to be approximately 1.79Ma.All ages are expected to have an error of0.03e 0.05Ma(e.g.,Feibel et al.,1989).In addition to the sedimentological indicators of paleogeog-raphy,we used paleopedology to interpret environmental con-text of the isotopic results.At the outcrop,we identified pedogenic carbonate and paleosols by criteria set forth in Re-tallack(2001)and refined for the Turkana Basin by Wynn (2000,2001,2004).We sampled pedogenic carbonates in the preserved calcic horizon of the paleosol at a minimum of30cm below the contact with the overlying stratum,as sug-gested by Quade and others(1989),and excavated back from the vertically exposed surface by approximately50cm(e.g., Sikes,1994).Calcite nodules were extracted from within indi-vidual peds.Since most Turkana fossil soils are paleovertisols, they show vertic features and slickensided surfaces;we chose calcite nodules that exhibited slickensides and/or were adjacent to slickenslided surfaces.Although abundant in the formation deposits,we did not include calcareous rhizoliths in this study due to isotopic alteration by shallow cementation(Driese and Mora,1993)and groundwater(Liutkus et al.,2005).In the laboratory,we sectioned pedogenic nodules and sam-pled micritic portions with a0.5mm carbide drill bit(Foredom Series),avoiding surface and sparry calcite.We subsampled nodules2e6times depending on size in order to test for internal nodular variability and averaged the subsample values.Approx-imately5%of the samples were analyzed by cathodolumines-cence(CL)to test for groundwater contribution(Marshall, 1988;Wynn,2004).All isotopic analyses were conducted at the Stable Isotope Laboratory at Rutgers University on a Micro-mass Optima Mass Spectrometer with an attached Multi-Prep device.Samples were reacted in100%phosphoric acid at 90 C for13minutes.d13C values are reported versus the Pee Dee Belemnite reference standard(V-PDB)through analysis of the laboratory standard(NBS-19)with values of1.95&for d13C(Coplen et al.,1983).We used Wynn’s(2000,2001)savanna environment cate-gories to interpret the d13C values as they reflectfloral com-munity structure and composition.We acknowledge the fluidity of ecotonal boundaries,but attempt to explainfloral community change with statistically significant shifts in d13C values.As widespread sampling of fossil soils at one interval potentially yields a wide range of isotopic ratios spanning the values of C3-C4communities,we approached the question of significant change in vegetation across space and through time in the following ways.In order to gauge change in veg-etation across space,we compared results by subregion,due to position within the basin(e.g.,proximal to the basin margin, proximal to the lake shore).For change in vegetation through time,we delineated brackets of time that witnessed major changes in paleogeography.Paleogeographic interpretations are based on sedimentary evidence and provide the context for our isotopic results.We present our results in100-kyr565R.L.Quinn et al./Journal of Human Evolution53(2007)560e573intervals that confine major changes of paleogeography and deposition: 2.0e1.9Ma, 1.9e1.8Ma, 1.8e1.7Ma, 1.7e 1.6Ma,and1.6e1.5Ma.The last two intervals record the same depositional environment.We also examined the results by subregion and by subregion within100-kyr intervals.In all approaches,we treated our groups as populations and com-pared means and variances between groups with one-way AN-OV A,Tukey’s all pairs comparison,and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests.We also interpolated change through time amongst all datapoints with a10%weighted smooth curvefit after Sti-neman(1980).All summary statistics and statistical analyses were conducted with KaleidagraphÒSoftware.Results and interpretationd13C values of pedogenic carbonatesd13C values of all pedogenic carbonates from Koobi Fora yielded a mean ofÀ5.5&and standard deviation of1.6(Table 1).Summary statistics are shown by formation and subregions (Table1)and by100-kyr intervals(Table2).Estimated with a10%weighted smooth curvefit,the formation shows a3& depletion in13C from2.0to1.75Ma.After1.75Ma,the curve fluctuates within1&(Fig.5).Results from100-kyr intervals representing different depositional environments show that all are not likely drawn from one population(p<0.001). One-way ANOV A and Tukey’s all pairs comparison results are shown in Tables3and5.Four of ten paired comparisons show significant differences between groups(p<0.001);the first two100-kyr intervals(2.0e1.9Ma,1.9e1.8Ma)vary sig-nificantly from the next two100-kyr intervals(1.8e1.7Ma, 1.7e1.6Ma)(Table2;Fig.6).Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test corroborates the results of the one-way ANOV A(Table3).Results by subregion for all time intervals also show mean-ingful differences between groups.One-way ANOV A and Tu-key’s all pairs comparison results are shown in Tables4and6. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test yielded similar results(Table4). The data from the Karari Ridge and Il Dura are significantly different from those of the Koobi Fora Ridge and Ileret (p<0.001;Fig.7).Furthermore,comparing the subregions within individual100-kyr intervals yields significant differ-ences between groups(Fig.8).In the1.9e1.8Ma interval, data from the Karari Ridge,Il Dura,and Koobi Fora Ridge do not vary significantly from one another.Results from the one-way ANOV A and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test indicate that the samples are likely from the same distribution.However, results from the following three100-kyr intervals show that the subregions reflect different populations(Fig.8);results from the one-way ANOV A and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test corrob-orate the smooth curvefits(p<0.001).In each of the 1.8e1.7Ma, 1.7e1.6Ma,and 1.6e1.5Ma intervals,data from the Karari subregion significantly vary from those of the Koobi Fora Ridge and Ileret subregions(p<0.001).Table1Summary statistics by subregionsAll subregions KoobiFora RidgeKarariRidgeIleret Il DuraSample size2027185397 Mean d13C valueÀ5.47À4.73À6.27À4.76À7.05 Median d13C valueÀ5.46À4.69À6.35À4.60À6.31 Minimum d13C valueÀ10.43À10.43À9.07À6.74À9.53 Maximum d13C value0.430.43À3.30À3.38À5.79 Standard deviation 1.63 1.85 1.190.87 1.59 Standard error0.110.220.130.140.60 Variance 2.65 3.40 1.420.77 2.52 SkewnessÀ0.04À0.470.06À0.52À0.89 Kurtosis 1.31 2.31À0.18À0.63À1.08Table2Summary statistics by100-kyr intervals2.0e1.9Ma1.9e1.8Ma1.8e1.7Ma1.7e1.6Ma1.6e1.5Ma Sample size1154436232 Mean d13C valueÀ7.10À6.22À4.98À4.85À5.48 Median d13C valueÀ7.16À5.94À4.90À4.66À5.51 Minimum d13C valueÀ8.54À10.43À9.37À7.22À9.07 Maximum d13C valueÀ5.37À3.760.43À0.44À3.67 Standard deviation0.96 1.49 1.83 1.42 1.24 Standard error0.290.200.280.180.22 Variance0.92 2.21 3.36 2.02 1.53 Skewness0.16À1.010.100.52À0.81 KurtosisÀ0.68 1.010.870.850.65Fig.5.d13C(&)vs.age(Ma).Pedogenic carbonate d13C values from paleo-sols in the Koobi Fora Formation between2.0and1.5Ma.Black line repre-sents10%weighted smooth curvefit of all data points(B).Savanna categories are taken from Wynn(2000,2001).566R.L.Quinn et al./Journal of Human Evolution53(2007)560e573Interpretation offloral compositionsThe Koobi Fora Formation preserves a range of habitats from forest(minimum d13C:À10.4&)to savanna grassland (maximum d13C:0.4&)with the majority of environments falling in the mosaic compositions including savanna wood-land,thicket and scrub,and low-tree shrub savanna(mean d13C:À5.5&;interpreted after Wynn,2000,2001).Based on Cerling’s(1984)model of C4contribution to soil CO2,trop-ical grasses comprised46%of the average landscape and ranged from11e89%.Floral compositions by subregion are presented below(Table1;Figs.7and8).Il Dura.Sampled paleosols are moderately to well-developed clay vertisols,based on thickness,ped structure,and large dish-shaped slickensides(e.g.,Aberegaiya variant after Wynn, 2000),with a soil moisture estimate of>1000mm/yr by calcic horizon at depth of approximately600e800cm(Wynn,2000, 2004).We observe low d13C values prior to1.8Ma,with grasses comprising35%(range:18e44%)of theflora.We interpret woodland savanna and/or thicket and scrub environments in this subregion.Ileret.The sampled Ileret soils are thin(40e60cm),imma-ture vertisols similar to Dite paleosols(Wynn,2000)based on their crumb ped structures,shallow calcic horizons,and their stratigraphic positions between channelized tuffs.Samples are from one depositional environment andfluctuate in d13C values betweenÀ6andÀ4&(Fig.8),constituting approxi-mately40e60%of grassy vegetation.We interpret the savanna category based on isotopic results primarily as low-tree shrub, with few woodland,and thicket and scrub environments.Koobi Fora Ridge.Paleosols from the Koobi Fora Ridge vary markedly in morphology but generally show a high clas-tic content likely due to proximity to afluctuating lake margin (Feibel,1988).One soil in particular,the Lorenyang pedotype (after Wynn,2004),is present at and after1.8Ma,and shows distinct sand-filled surface cracks and a thick calcic horizon. This fossil soil has been interpreted to support seasonally sparse savanna grassland with little time for development due to quick burial(Wynn,2004).d13C results from this sub-region corroborate the previous interpretations of expansion of C4grasses after1.8Ma(Cerling et al.,1988;Wynn,2004). The weighted smooth curve of d13C values at1.9e1.8Ma in-creases fromÀ6toÀ4&(40e60%grasses),placing the area within the low-tree shrub category.After1.8Ma,the curve shifts to more open savanna grassland environments and then returns to the low-tree shrub category at1.65Ma(Fig.8).Karari Ridge.The Karari paleosols show morphological di-versity.Below the KBS Tuff,the Karari shares the Aberegaiya paleosol with the Il Dura subregion.Directly underlying the Okote Tuff Complex(w1.6e1.5Ma),the Kimere pedotypeTable3Results of one-way ANOV A and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test of100-ky inter-val groupsOne-way ANOV A DF SS MS F P Total201531.91 2.6510.51<0.0001 A493.5523.39Error197438.35 2.23Kruskal-Wallisrank sum testK-W statistic P37.02<0.0001Table4Results of one-way ANOV A and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test of subregion groupsOne-way ANOV A DF SS MS F P Total201532.00 2.6521.47<0.0001 A3130.5843.53Error198401.42 2.03Kruskal-Wallisrank sum testK-W statistic P63.20<0.0001Table5Results of Tukey’s all pairs comparison by100-kyr interval groups Comparison Meandifferencej q j P95%CL(1.7-1.6)vs.(2.0-1.9) 2.25 6.52<0.00010.91e3.59 (1.7-1.6)vs.(1.9-1.8) 1.37 6.97<0.00010.60e2.13 (1.7-1.6)vs.(1.6-1.5)0.63 2.740.2998À0.26e1.52 (1.7-1.6)vs.(1.8-1.7)0.130.630.9916À0.68e0.95 (1.8-1.7)vs.(2.0-1.9) 2.12 5.940.00040.73e3.50 (1.8-1.7)vs.(1.9-1.8) 1.24 5.740.00070.40e2.08 (1.8-1.7)vs.(1.6-1.5)0.50 2.020.6105À0.46e1.46 (1.6-1.5)vs.(2.0-1.9) 1.62 4.390.01830.18e3.06 (1.6-1.5)vs.(1.9-1.8)0.74 3.140.1762À0.18e1.66 (1.9-1.8)vs.(2.0-1.9)0.88 2.520.3856À0.48e2.24Fig.6.Nonparametric box and whisker plots of d13C values(&)by100-kyr interval groups.567R.L.Quinn et al./Journal of Human Evolution53(2007)560e573。