What We Talk About When We Talk About Time What We Talk About When Mark Steedman We Talk Ab

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:350.91 KB

- 文档页数:86

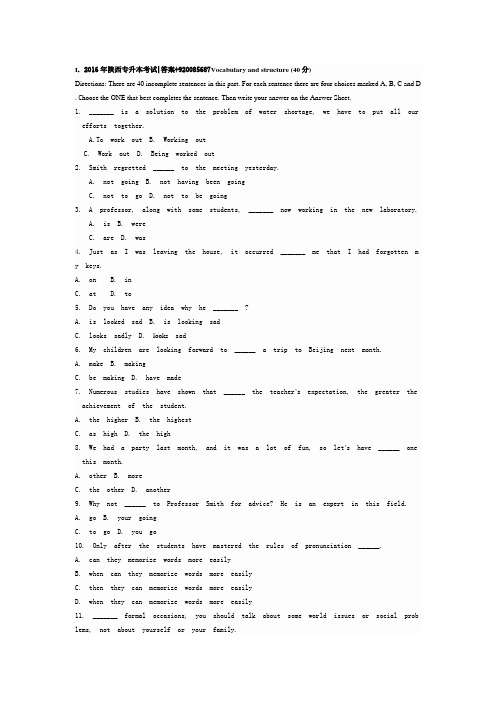

I.2016年陕西专升本考试|答案+920085687Vocabulary and structure (40分)Directions: There are 40 incomplete sentences in this part. For each sentence there are four choices marked A, B, C and D . C hoose the ONE that best completes the sentence. Then write your answer on the Answer Sheet.1. _______ is a solution to the problem of water shortage, we have to put all ourefforts together.A.To work outB. Working outC. Work outD. Being worked out2. Smith regretted ______ to the meeting yesterday.A. not goingB. not having been goingC. not to goD. not to be going3. A professor, along with some students, _______ now working in the new laboratory.A. isB. wereC. areD. was4. Just as I was leaving the house, it occurred _______ me that I had forgotten m y keys.A. onB. inC. atD. to5. Do you have any idea why he _______ ?A. is looked sadB. is looking sadC. looks sadlyD. looks sad6. My children are looking forward to ______ a trip to Beijing next month.A. makeB. makingC. be makingD. have made7. Numerous studies have shown that ______ the teacher’s expectation, the greater theachievement of the student.A. the higherB. the highestC. as highD. the high8. We had a party last month, and it was a lot of fun, so let’s have ______ onethis month.A. otherB. moreC. the otherD. another9. Why not ______ to Professor Smith for advice? He is an expert in this field.A. goB. your goingC. to goD. you go10. Only after the students have mastered the rules of pronunciation ______.A. can they memorize words more easilyB. when can they memorize words more easilyC. then they can memorize words more easilyD. when they can memorize words more easily11. _______ formal occasions, you should talk about some world issues or social prob lems, not about yourself or your family.A. InB. AtC. OnD. By12. _______ troublesome the problem is, he faces it with patience.A. No matterB. AlthoughC. DespiteD. However13. Since you won’t lend us your motor car, you should at ______ tell us where we can borrow one.A. mostB. leastC. largeD. length14. _______ the English evening, I would have gone to the cinema.A. As forB. But forC. In spite ofD. Due to15. The British painter who had been praised very highly _____ to be a great disap pointment.A. turned outB. turned upC. turned inD. turned down16. It is not always right to judge a person on the ______ of the first impressio n.A. basicB. basisC. baseD. basement17. Generally speaking, your success ______ your ability and efforts.A. comes ofB. depends onC. belongs toD. grows up18. Everybody has access ______ the large collection of books on various subjects inour department library.A. ofB. forC. toD. about19. Thirty miles away from the town, the robbers _______ the car and disappeared in to the woods.A. approachedB. groundC. abandonedD. removed20. Though this house is very old and may not be worth much, it is _______ greatemotional value to my father who spent all his childhood days here.A. byB. ofC. withD. for21. Read the book carefully ______ you will find lots of information related to ourresearch.A. ifB. orC. soD. and22. He prefers to rent a car ______ have one of his own.A. other thanB. rather thanC. on condition thatD. would rather23. In the past ten years Jack has been with us. I think he has proved that he ______ respect from every one of us.A. qualifiesB. expectsC. reservesD. deserves24. It was some time ______ the door opened in response to his ring.A. beforeB. whenC. afterD. since25. It is a huge task to ______ all the rooms in the building in such a short t ime.A. go ahead withB. keep upC. clean upD. work out26. What he has done shows that he is not a man ______.A. whom you can believeB. that you can believeC. whom you can believe inD. what you can believe in27. He was ______ to speak the truth.A. too much of a cowardB. so much a cowardC. too much a cowardD. so much of a coward28. If we continue to argue over minor points, we won’t get ______ near a solution.A. somewhereB. elsewhereC. everywhereD. anywhere29. There are some ______ flowers on the table.A. unrealB. falseC. artificialD. unnatural30. When Mr. Jones gets old, he will _______ over his business to his son.A. takeB. handC. thinkD. get31. I can _______ some noise while I’m studying, but I can’t stand loud noise.A. put up withB. keep up withC. catch up withD. come up with32. If we had adequate time to prepare, the results _______ much better.A. would beB. wereC. had beenD. would have been33. I like climbing mountains _______ my wife prefers water sports.A. asB. whenC. forD. while34. Some parents are just too protective. They want to _______ their kids from ever y kind of danger, real or imagined.A. shelterB. locateC. preventD. release35. As a cleaning woman, her ______ duties include cleaning the desks and mopping t he floor.A. continuousB. routineC. initialD. constant36. The kids lay face down to the beach, their backs _______ to the sun.A. whatB. thatC. whateverD. those37. It wasn’t the diner. It was ______ people talked about at the dinner that disgu sted him.A. whatB. thatC. whateverD. those38. For generations the people in these two villages lived in perfect ______.A. conflictB. distinctionC. harmonyD. regulation39. He was seriously injured in the accident and lost his consciousness. When he __ ______ he found himself in a hospital bed.A. came offB. came upC. came inD. came to40. His face _______ when he told a lie.A. gave him offB. gave him awayC. gave him upD. gave him out得分评卷人Ⅱ. Reading Comprehension(50分)Directions: There are 4 passages in this part. Each passage is followed by some questions or unfinished statements. For ea ch of them there are four choices marked A, B, C and D .You should decide on the best choice and write the correspondin g letter on the Answer Sheet.Questions 41 to 45 are based on the following passage:Passage OneWhat do we talk about when we talk about money? We often think about what we c an buy with the money we have, what we can’t buy because we don’t have enough and what we’re planning to buy when we have more. We discuss the careers that bring u s money and the expenses that take it away. We talk about our favourite shops and restaurants, the causes we support, the places we’ve been and seen. We share dreams that only money can make real.In short, we talk about everything but money itself. In daily life, money is sti ll a major conversational taboo. This is a shame, because money is as interesting a s the things it does and buys, and the more you know about it, the more interesti ng it is.(81) As a financial advisor, I’ve seen hundreds of people learn to control theirmoney instead of letting it control them and watched as they increased as they in creased their freedom, power and security by handling money consciously. Wouldn’t you like to know that you’ll always have enough money to live exactly as you want to?You will never be powerful in life until you’re powerful over your own money. Ta lking openly about it is the first step.41. Which of the following is NOT discussed when we talk about money?A. The careers that bring us moneyB. The causes we supportC. The dreams that only money can make realD. Money itself42. What can we know from the second paragraph?A. We should know more about money itself rather than avoid talking about it.B. Money itself can interest us and bring us happiness.C. The more money we earn, the more we should know about it.D. It is a shame that people talk too much about money.43. What does the writer want to say in the third paragraph?A. People should learn how to make money.B. People should know the value of money.C. People should learn to control their money.D. People should know how to use money to increase their power.44. The writer’s advice that _____.A. the more you talk about money, the more you can control it.B. we should learn to be a good master of our money if we want to be powerfulin lifeC. we should not be so worried about money if we want to have a free lifeD. the more money you have, the more powerful you are45. What will the writer probably talk about after the last paragraph?A. The importance of moneyB. Money, power and securityC. The other steps for people to control moneyD. The steps for people to make moneyQuestions 46 to 50 based on the following passage:Passage TwoA question often put to the specialist on fishes is “How long do fishes live?”This puts the specialists in an embarrassing position because he is often unable to give a direct answer to this simple question.But actually this question is not as simple as it seems. There are thousands of different kinds of fishes, and they vary a great deal in size and life span. Mor eover, it is not easy to find out just how long a fish lives in its natural stat e.We can find out how old a fish is by studying its scales, but we cannot say h ow much more time it would live if we had not caught it.We may rear fishes and record their life span but we cannot be sure that this is the length of time they would have lived, had they been left alone.We may make marking to show how fast the fishes grow so that we can calculate the age of the largest on record, but unless this large fish dies of old age we are still not in a position to know its natural life span.(82) unlike human beings, fishes do not stop growing when they reach maturity. They continue to grow as long as they live, although the rate of growth slows down in mature fishes.46. People often ask the specialist on fishes regarding its _______.A. sizeB. life spanC. ageD. variety47. The specialist is embarrassed by the question because _______.A. he does not know the answerB. there is no answer to the questionC. it is a silly and simple question for himD. there is no definite answer to this question48. We can know a fish’s age from its ______.A. weightB. sizeC. scales D . length49. Which of the following statements is NOT true?A. Different kinds of fishes have different life spans.B. It is hard for the specialist to know the length of time a fish lives in its natural stateC. Mature fishes grow more quickly than young ones.。

谈论的英语短语谈论,是指以谈话的方法表示对人对事的看法。

下面就由店铺为大家带来关于谈论的英语短语集锦,希望大家能有所收获。

关于谈论的相关短语谈论 talk about谈论学习 Talking about Study谈论往事 Talking about Past Events谈论未来 Talking about the future谈论中的 In questions谈论产品 Talking about products谈论礼节 Talking about Etiquette谈论穿着 Talking about Things to Wear谈论歌剧 Talking About Opera谈论婚姻 ChaMing about Marriage ; T alk About Marriage关于谈论的相关短句discuss state affairs;谈论国家大事He never speaks unadvisedly about anything.他从来不轻率地谈论任何事情。

关于谈论的相关例句1. He cracked jokes and talked about beer and girls.他爱说笑话,喜欢谈论啤酒和姑娘。

2. He was disinclined to talk about himself, especially to his students.他不喜欢谈论他自己,尤其是当着他学生的面。

3. We can now talk openly about AIDS which we couldn't before.现在我们能公开谈论以前讳言不提的艾滋病问题。

4. There's something about the way he talks of her thatdoesn't fit.他谈论她的样子有点不对劲。

5. I've always found him clued-up on whatever he was talking about.我一直都觉得他对自己谈论的任何事情都了如指掌。

英语口语知到章节测试答案智慧树2023年最新西安工业大学第一章测试1.It is the first time you meet your English teacher, Miss Taylor, at her office.What would you say to greet her?参考答案:null2.You come across your senior high school classmate David at a shoppingcenter and you haven't seen each other after graduatition. What would say to greet him?参考答案:null3.What would you generally say to respond the question "How are you?"informal settings?参考答案:null4.There is a foreign traveller who is asking people the way to a touristattraction in English in the street. However, the passers-by can't speakEnglish. You want to give him a helping hand. What would you say to startthe conversation?参考答案:null5.What are the ways of talking about your interests?参考答案:null6.which of the following words are the synonyms of hobby?参考答案:leisure pursuit;pastime;interest7.If you try to make your emotion stronger to express your favorite leisureactivities, which of the following words can be used?参考答案:very much;really;absolutely8.What details can you say when you try to develop to talk about your hobbies?参考答案:Reasons why you like it;Friends whom you usually do the activitieswith.;the places and regular time you do the activities;Your feelings and experiences you take up the activities.9.which of the following activities belong to typicalourdoor activities?参考答案:hiking;scuba diving;camping10.In British English, in words written with a vowel plus R, the R is not normallypronounced.参考答案:对第二章测试1.I’m capable_______ handling the complaints of the client.参考答案:of2.You will _______ into the team.参考答案:fit3.His calmness enables him _______ such an emergent problem.参考答案:to solve4.He is _______ at communication and cooperation.参考答案:good5.Which word belongs to a different category?参考答案:cooker6.What is the most important thing when someone is doing an interview?参考答案:Self-confidence.7.What kind of questions are you going to answer in an interview?参考答案:Experience and education;Reasons you apply for the job;Weak andstrong points8.What do you need to do in order to make a better impression?参考答案:To make a full preparation.;To arrive ahead of time;To behaveconfidently and politely;To dress appropriately for a job9.white, grey and black are the colors which can always help you if you arehesitant which color is more suitable.参考答案:对10.It's ok to say I hate my current job or my current boss when answering thequestion "why do you come to work here in this company".参考答案:错第三章测试1.Where can we get access to some professional and extracurricular books inschool?参考答案:Library2.Where can we do some physical and chemical experiments which arenecessary and required during the school days?参考答案:Laboratory3.Which places in the following items are mentioned in today’s video lessontalking about the campus life?参考答案:Laboratory building;Dining hall;Gymnasium;Library;Dorm4.Where can we buy the household goods including the daily necessities andluxury goods?参考答案:Shopping mall5.When people feel unwell, they can go to hospital or just get some medicinesin a pharmacy.参考答案:对6.When you are lost in an unfamiliar environment, you can ask the passerbyfor directions by saying that “Hi, you know where the City Center is, don’t you?”参考答案:错7.When you are asked by strangers for how to get to the destination, you’dbetter use some place prepositions, i.e., (at) the corner of, next to and across etc.参考答案:对8.“Somebody sets off sooner” refers that he/she arrives at the destination early.参考答案:错9.Find out the public and private vehicles among the following items.参考答案:Sports car;Ambulance;Ferry;Limousine;Underground;Carriage10.We can hold a discussion about the situations between cities and towns insome ways such as job opportunities, crime rate, living environment,pollution and so forth.参考答案:对第四章测试1.If you try to describe your friend who is neither tall nor short to others, whatwould you say?参考答案:He is of medium height.2.How can we state precise height?参考答案:He is 1.78 meters tall.;He is 1.78 meters high.;He is 1.78 meters inheight.3.Which of the following words are used to describe a woman who is thin in anattractive way?参考答案:slim;slender4.Which of the following words is to describe a person who is tall and thin withlong limbs?参考答案:lanky5.which of the following is the proper description of one's hair style?参考答案:Miranda is ginger. She has bobbed hair with fringes over theforehead.;Miranda is black haired. Her hair is straight and long , to her shoulder.6.What are you wearing today?null7.which of the following items don't belong to accessories?参考答案:flip flops8.How do you describe the color, pattern and material of a cloth?参考答案:a black and white checked cotton shirt;a denim jacket with foral print9.When we talk about fit of clothes, we could usually say the followingsentences except_________.参考答案:null10.What can we say when we compliment one's clothes?参考答案:I like the fit.;You look very smart.;It looks good on you.;It makes youlook slimmer.第五章测试1.Is there anything _____ sale?on2.How to translate "Could you do it for 500? "参考答案:500元行吗3.What's the eaning of "buy one get one 50 % off"?参考答案:买一件,第二件半价4.I’d like to have a ____ (退款)on this pair of shoes.参考答案:refund5.Do you have the coat _____ white?参考答案:in6.Which word has similar meaning with the word "bargain"?参考答案:haggle7.When our friends try on new clothes which fit them well, how can we canalso praise them?参考答案:You look charmingin this dress.;You look nice in this color.;You lookfashionable in this style.8.How to ask for price when you buy an item?参考答案:How much do I have to pay for it?;What’s the price for this suit?;How much does it cost?9.Falling tone is used in _________?参考答案:Statements;Commands;Exclamations;Wh-questions10.买家的话"My best price for it is 600."应翻译成“我最少出600元”。

关于如何对待国家文化差异的英语小作文全文共10篇示例,供读者参考篇1When we talk about how to deal with cultural differences between countries, we should remember that each country has its own unique customs and traditions. It's important to respect and learn about these differences in order to understand and appreciate other cultures.First of all, we should be open-minded and curious about different cultures. We can watch movies, read books, or even talk to people from other countries to learn about their traditions and customs. By being open to new experiences, we can broaden our horizons and develop a greater understanding of the world around us.Secondly, it's important to be respectful towards other cultures. We should avoid making assumptions or generalizations about people from different countries. Instead, we should approach them with an open mind and be willing to learn from them. By showing respect and understanding towardsother cultures, we can create a more peaceful and harmonious world.Lastly, we should remember that cultural differences are nothing to fear. In fact, they can be an enriching and rewarding experience. By embracing diversity and learning from each other, we can create a more inclusive and tolerant society.In conclusion, dealing with cultural differences between countries is all about respect, curiosity, and open-mindedness. By being willing to learn from others and appreciate their customs and traditions, we can create a more interconnected and harmonious world. Let's celebrate our differences and learn from each other to create a more united global community.篇2How to Deal with Cultural DifferencesHey guys! Today let's talk about how to deal with cultural differences. Have you ever met someone from a different country and felt a bit confused about their customs or traditions? It's okay, we're all learning and growing. Here are some tips on how to handle cultural differences with respect and understanding.First of all, it's important to keep an open mind. Just because someone does things differently than you, doesn't mean it's wrong. Different countries have different histories, beliefs, and traditions that shape the way people behave. So, instead of judging others, try to learn more about their culture and ask questions if you're curious.Secondly, be respectful towards others' customs. If you're visiting or living in a different country, it's a good idea to learn about their etiquette and traditions. For example, bowing is a sign of respect in some Asian countries, while in Western countries, a firm handshake is more common. By respecting and following their customs, you show that you care about their culture.Next, be patient and understanding. Cultural differences can sometimes lead to misunderstandings or miscommunications. Instead of getting frustrated, try to see things from the other person's perspective. Remember that we all come from different backgrounds, and it's important to be patient and empathetic towards one another.Lastly, embrace diversity and celebrate differences. The world is a big, beautiful place full of different languages, foods, and traditions. Instead of being afraid of cultural differences,embrace them and see them as an opportunity to learn and grow. By celebrating diversity, we can create a more inclusive and harmonious world for everyone.In conclusion, dealing with cultural differences can be a learning experience for all of us. By keeping an open mind, being respectful, patient, and embracing diversity, we can build strong relationships with people from all walks of life. So, let's continue to learn from each other and appreciate the rich tapestry of cultures that make our world so unique and beautiful.篇3Title: How to Handle Cultural Differences in Different CountriesHey guys! Today let's talk about how to deal with cultural differences in different countries. It's really important to be respectful and open-minded when we interact with people from different cultures. Here are some tips to help us navigate cultural diversity:First of all, we should try to learn about the customs and traditions of the country we are visiting or the people we are interacting with. This will help us understand their way of life and avoid unintentionally offending them. For example, in Japan, it'spolite to bow when greeting someone, so we should remember to do that.Secondly, we should always be open to new experiences and willing to try new things. For example, if we are in a country where people eat with their hands, we should not be afraid to try it out. It's all part of the adventure of experiencing different cultures.Thirdly, we should be respectful of cultural norms and values. This means avoiding behaviors that might be considered rude or disrespectful in a particular culture. For example, in some cultures, it's rude to point at someone with your finger, so we should always use our whole hand instead.Lastly, we should always remember that diversity is a beautiful thing. Instead of judging others based on their cultural differences, we should celebrate the uniqueness of each culture and learn from each other. By embracing cultural diversity, we can build stronger relationships and create a more peaceful world.So, let's remember to be respectful, open-minded, and willing to learn about different cultures. By doing so, we can all live in harmony and appreciate the richness of our world's cultural tapestry. Thank you for listening!篇4How to Treat Differences in National CulturesHey guys! Today I want to talk about how to treat differences in national cultures. It's super important to be respectful and understanding of other people's cultures, even if they're different from ours. Here are a few tips on how to do that.First of all, we should be curious about other cultures. It's really cool to learn about how people in other countries live, what they eat, how they dress, and what traditions they have. We can read books, watch documentaries, or talk to people from other countries to learn more about them.Secondly, we should never judge or make fun of someone because of their culture. Just because something is different from what we're used to, doesn't mean it's wrong. We should always keep an open mind and be willing to accept and respect different ways of doing things.Another important thing is to be polite and respectful when interacting with people from different cultures. We should listen carefully to what they have to say, ask questions if we're not sure about something, and try to learn from them.Finally, we should celebrate diversity and embrace the differences in national cultures. It's what makes the world such an interesting and colorful place. By being open-minded and accepting of different cultures, we can learn so much and make new friends from all over the world.So, guys, let's always remember to treat differences in national cultures with kindness and respect. It's what makes us better human beings and helps us to create a more peaceful and harmonious world.篇5Hey guys! Today I want to talk to you about how to deal with cultural differences. It's really cool to learn about different cultures, but sometimes we might not understand everything right away. Here are some tips on how to handle it:First, don't judge. Just because something is different from what you're used to doesn't mean it's wrong. Try to keep an open mind and be respectful of other people's traditions and customs.Second, ask questions. If you don't understand something, don't be afraid to ask. People will usually be happy to explain their culture to you and it's a great way to learn new things.Third, be patient. It can take time to get used to new cultural practices, so don't worry if you don't understand everything right away. Just keep an open mind and be willing to learn.Lastly, remember that everyone is different. Just because someone is from a different culture doesn't mean they are all the same. Treat each person as an individual and try to learn about their unique background.So there you have it guys, some tips on how to deal with cultural differences. Remember, it's all about beingopen-minded, respectful, and willing to learn. Have fun exploring new cultures!篇6Hello everyone, I'm going to talk about how to deal with cultural differences between countries. It's important to respect and understand other cultures, even if they are different from our own.First of all, we should be open-minded and willing to learn about different customs, traditions, and beliefs. We can read books, watch movies, and talk to people from other cultures to get a better understanding of them. It's okay to ask questions and be curious, as long as we do it in a respectful way.Secondly, we should be tolerant and accepting of cultural differences. Just because something is different doesn't mean it's wrong. We should try to see things from a different perspective and appreciate the diversity of our world.Thirdly, we should be willing to adapt and adjust our behavior when interacting with people from different cultures. This means being aware of cultural norms, such as greetings, gestures, and body language. It's important to show respect and avoid making assumptions about others based on their culture.In conclusion, embracing cultural differences can lead to a greater appreciation and understanding of the world around us. By being open-minded, tolerant, and willing to adapt, we can build stronger connections with people from diverse backgrounds. Let's celebrate our differences and learn from each other to create a more harmonious and inclusive society. Thank you for listening to my speech!篇7Hey guys, today let's talk about how to deal with different cultures in the world.First of all, we need to understand that different countries have different customs and traditions. It's important to respectother people's beliefs and practices even if they are different from ours. We should not judge or criticize others just because they do things differently.Secondly, we should try to learn about other cultures. This can help us appreciate the diversity in the world and also help us understand why people do things in a certain way. We can read books, watch movies, and talk to people from different countries to learn more about their culture.Thirdly, we should be open-minded and willing to try new things. We might find that we actually enjoy some aspects of a different culture once we give it a chance. Whether it's trying new foods, learning a new dance, or participating in a cultural festival, being open-minded can help us appreciate and respect other cultures.In conclusion, respecting, learning about, and beingopen-minded towards different cultures are important ways to deal with cultural differences. By doing so, we can create a more harmonious and understanding world where people of all cultures can live in peace and harmony. Let's embrace the diversity in the world and celebrate the beauty of different cultures!篇8Title: How to Handle Cultural DifferencesHey guys! Today, I'm going to talk about how we can treat national cultural differences in a nice way. It's super important to be respectful of other people's cultures, even if they are different from our own. So let's dive into it!First of all, we should try to understand and appreciate the differences. Every country has its own unique traditions, customs, and beliefs. Instead of judging or making fun of them, we should try to learn about them. It's like a cool adventure where we get to explore new cultures!Secondly, we should be open-minded and curious. If we have friends or classmates from different countries, we can ask them questions about their culture. They would love to share about their traditions and teach us new things. We can also try new foods, listen to different music, or even learn a few words in their language. It's so much fun to discover new things!Moreover, we should always be respectful and tolerant. Even if we don't agree with or understand a certain cultural practice, we should never mock or criticize it. Everyone has the right totheir own beliefs and ways of life. We should treat others the way we want to be treated, with kindness and respect.In conclusion, embracing cultural differences is awesome! It makes the world more colorful and exciting. So let's keep an open heart and mind, and show love and respect to all cultures around us. Let's be cultural ambassadors and spread positivity and harmony wherever we go. Together, we can make the world a better place for everyone! Let's do this, guys!篇9How to Treat Cultural Differences in Different CountriesHey guys, do you know that people in different countries have different cultures? It's super cool, right? But sometimes it can be a little bit confusing when we don't know how to treat these cultural differences. So, here are some tips on how to do it!First of all, we should always be respectful of other people's cultures. That means we should never make fun of or judge someone just because their culture is different from ours. We should try to understand and appreciate their traditions, customs, and beliefs.Secondly, we should always be open-minded and willing to learn about other cultures. We can do this by reading books, watching documentaries, or talking to people from different countries. It's so much fun to learn about how other people live and celebrate their traditions!Next, we should try to be sensitive to cultural differences and avoid making assumptions. For example, it's important to remember that gestures or words that are okay in our culture may be offensive in another culture. So, let's always think before we speak or act.Lastly, let's celebrate diversity and embrace the beauty of cultural differences. Instead of thinking that one culture is better than another, let's appreciate the uniqueness and richness of each culture. By doing this, we can create a more harmonious and peaceful world.So, guys, let's remember to treat cultural differences with respect, curiosity, sensitivity, and acceptance. Let's celebrate diversity and make the world a better place for everyone!篇10Title: How to deal with cultural differences between countriesHey guys! Today I want to talk about how we should treat cultural differences between different countries. It can be really cool to learn about other cultures, but sometimes it can also be a little confusing. Here are some tips on how to handle it:First of all, we should always be respectful of other people's cultures. Just because something is different from what we are used to, doesn't mean it's bad or wrong. We should try to keep an open mind and understand that people from different places may have different ways of doing things.Secondly, we can try to learn more about the culture of the country we are interacting with. This can help us understand why people do things a certain way and can also help us avoid accidentally offending someone. We can read books, watch movies, or even talk to people from that culture to get a better understanding.It's also important to remember that cultural differences can be a good thing! They can teach us new ways of thinking and doing things, and can make the world a more interesting place. So instead of being afraid of differences, we should embrace them and see them as an opportunity to learn and grow.In conclusion, cultural differences between countries are a normal part of life and we should treat them with respect andcuriosity. By keeping an open mind and trying to learn more about other cultures, we can create a more harmonious world where everyone can feel accepted and understood. Let's celebrate our differences and learn from each other!That's all for now, guys! Hope you found this helpful. Bye-bye!。

What do we talk about when we talk about innovationHere we go again! Veteran - three months, the United States silicon valley startups, "the secret history of silicon valley", the author Steve blanco (Steve Blank) on his blog, this song by Lady Gaga announced his clear judgment - once again came to the Internet bubble.The bubble is expanding faster and bigger than a decade ago. Over the past three years, with the wave of the magic wand, apple's market value has risen to $300 billion. Facebook except for an Oscar for best adapted screenplay award winner "the social network" provides an excellent material, its pre-ipo valuations is already from more than $100 shot up to billions of dollars. Behind them, MOTOROLA, HTC devices such as business has been overlooking its second spring of life, like LinkedIn, Twitter, its value is newly rich, the company and will have been corrected in multiplication.But if this is a bubble, why is the huge amount of capital still rushing in? Mr. Blanco noted that in 2011, the rules of the game for entrepreneurs and innovators were different from 2008 or 1998."Is different from the previous the industry bubble, the bubble in the first wave of winners (such as the realization of IPO) need to let everybody see the 'real' super size amount of revenue, profits and customers." "This is not a marketing'vision' or concept," blanke said.The first entrepreneurs to stand up in this bubble are amazing on many innovative data. Because of the huge user base on PCInternet and mobile Internet, they began a business model has been given the scale of hundreds of millions of users market effectively, these users in the future will continue to buy their equipment update/application. Accordingly, the number of users, or the size of the data, and the scale of the income, are no longer linearly dependent, but exponentially related. Still, Facebook, for example, now has nearly 600 million users. Accordingly, its data traffic has more than Google to become the world's first, constantly updating its advertising business model, the size of its revenue although has not been announced but conservative estimate should has amounted to $1 billion.More importantly, the barriers to innovation and entrepreneurship have been slowly melting away.The development of open source software let entrepreneurs no longer need to spend millions of dollars to buy expensive dedicated computers and software license, because the development tools, marketing channels have become more readily available, now need money already from the original innovative undertaking with millions of dollars to thousands of dollars; The past entrepreneurs often take months when an innovative products, and now, they in the development of these products in bytes of the Internet, may be more willing to spend a week to launch a short version or beta; The government and big business to accept the speed of the innovative applications have also been greatly accelerated, in the past when they face new things the vice smelly face knee-jerk is already out of sight.Blanco argues that these changes are more profound than mere technological change and call this trend "the democratisation of entrepreneurship". Obviously,This is a golden age for entrepreneurs and a great window for innovation.The question now is whether Chinese companies, in this context, are as innovative as weeds.The pacesetter set out againWe were sorry to pick up a conversation from silicon valley about China's innovation problem. This is a helpless, though China's GDP has jumped to the world's second, but when it comes to Chinese enterprises in the global industry innovation ability to lead, is still a lack of confidence.The Thomson Reuters intellectual property solutions division publishes an innovation report annually based on the world's top five patent databases. Between 2003 and 2009, China's total annual growth rate was 26.1 percent, well ahead of the United States, which grew at an annual rate of 5.5 percent. But China's patent filings are mostly pragmatic, not patented.In 2009 ~ 2009, the patent increase fastest (25%), the field of aerospace engineering of aircraft and satellite technology fields are in the top three sharp of Japan, South Korea's LG and samsung. Total in the patent of the top two computers and peripherals, automotive and other major areas in which all by Europe and the United States, Japan, South Korea and other developed countries occupy prominent position. China will be able to in the 12 critical areas into the "top ten patentholder/organization" list is limited to the agriculture, food, petrochemical, telecommunications, several areas, and the finalists for the academic research institutions, enterprises, only China petrochemical (chemical engineering), zte (mobile phone) and so on of a few in alone. And, as schumpeter points out, if the technology is still in the academic achievement stage and is not used by the enterprise, then "economically it will not work". From this point of view, the absence of Chinese companies in key innovation activities is obvious.Behind the data, it is also true that Chinese companies' performance in global competition is hard to say.Huawei and lenovo, two of the biggest benchmarks for Chinese companies, are now mainstream in the global landscape of their respective industries. Driven by strong marketing wolves, the company has been steadily rising over the past decade, and has now leapfrog the likes of nortel and MOTOROLA. In 2010, its global revenues were more than $28 billion, leaving only Ericsson ($30.8 billion) in front of him. After lenovo bought IBM's PC business, the integration has already been shown. Revenue was $16.6 billion in 2010, according to market share, which is now the world's third-largest PC vendor. In early 2011, lenovo consolidated its position with NEC's computer business. In the field of mobile phone manufacturing, although the "shanzhai" mixed at home, but sales of up to 600 million units in the international market, mediatek's international influence also nots allow to ignore.But, unfortunately, when these few benchmarking enterprise, after a long chase finally grow into big companies, industrycommanding heights trance in close proximity, another more precipitous target heights and spans in sight, they have to send set again.Since 2010,Huawei, lenovo, mediatek are launching intelligent terminal for transformation of the business, previously, respectively in the PC, communications network equipment, built is strong in GSM mobile phone industry leading ability. But like LCD revolution traditional domestic color TV enterprises in the field of CRT industry built from dream by Japan and South Korea enterprise break as easily, as tablets, smart phones and app store mobile Internet high tide of revolution, they built the barriers to competition in the field of the original is rapidly losing meaning. From low power consumption chip technology to the development of the mobile operating system to the product application experience the details of the polishing and software stores throughout the construction of ecological environment, the domestic enterprise to see, has fallen into the trap of imitate, follow and cannot extricate oneself.To be fair, the rise of huawei and lenovo, on the other hand, depends on the maturity and transfer of global industrial technology. On this point, huawei has admitted that suffered by excessive emphasis on "indigenous innovation", once ignored "the inheritance of mature technology is the key to improve product stability and reduce the cost", later on the independent development, while the "standing on the shoulders giants" the road of gradual innovation profit. But this is the moment when the mobile Internet is still in the ascendant, unlike communications devices, PCS and GSM phones. In thecontext of this industry, can the innovation strategies of domestic companies such as huawei be updated in time?About the future of huawei, ren zhengfei, once said: "how to adapt to the new world in the future, huawei is facing big challenges, I think that huawei is not adapt to, because a majority of huawei is repair the Great Wall, but with a way to repair the Great Wall in the past, when such as missiles, there is the Great Wall." And Mr Liu in the near future also said publicly, in the face of the present situation of consumer customers interested in tablets, lenovo if clung to existing products, not timely adjust strategy, there is also the danger of extinction. As the leader of the copycat innovation, mediatek into hard transition since 2010, the original flagship product, share and profit margins are declining, needs to be an opening for 3 g intelligent products.Clayton christensen in the innovator's dilemma: how do new technologies make great companies fall book, mainstream companies in the industry, especially those based on the existing mainstream technology of leading companies, because is difficult to get rid of the old the ecological value of "network" (including suppliers, integrators, distributors and end users) are complicated, in the face of disruptive innovation, tend to deal with.At this point, in fact, whether it be with incremental innovation catching up huawei, lenovo, or caused by the construction of innovation shanzhai agitation of mediatek, or is it like Google, wal-mart had a subversive type innovation by a "revolution" to the success of European and Americancompanies, they are no different. When they are in order to consolidate the ground and strategy, with a team, team building, set ", but its business model, organizational structure, once curing, was coined in the face of new market a hedge. Fortunately, these big companies are no longer strangers to the "innovator's dilemma".For companies that can't keep up with the pace of market and innovation, they can do so by buying more innovative small companies.The bigger pain for domestic companies, relative to foreign peers, is that they are late for success, but the time for new challenges is early. In recent years has been successful transformation of capitalist lei jun in the reflection of the jinshan rough history says more than twenty years, China's enterprises want to not as tired as in the past, "the key is at the right time to do the right thing", but in the actual business operations, how many people will spend money like lei jun investment of others, and how much worth the investment?Join the partyLike silicon valley peers, a new generation of domestic entrepreneurs are currently enjoying a global entrepreneurship "bubble bath", but not the same, they and the generation of already famous barons relations are not harmonious.At the government level, China's central government has unveiled a large and complex indigenous innovation program aimed at turning China into a technological powerhouse by 2020. By 2050, it will be the world's leading technology leader. This policy contains many incentives even make some European andAmerican countries believe that this represents China's political and economic relations with the United States and other developed countries have shifted from "defense" to "attack". Local governments, too, are trying to get more innovative companies through flexible allocation of resources.Among the people, and after the second world war the United States family wealth successor became involved in risk investment, such as the rockefellers, "rich second generation" group has become a domestic vc powerhouse. Most of them do not want to repeat the growth trajectory of their parents, but instead choose to invest in foreign innovation projects from agriculture to the Internet.However, when these different levels of venture capital, funds, and incubators are hunting for the sharks, true native innovation remains a scarce commodity.In the IT Internet, their success story is being replicated as the early Google imitators baidu and ICQ copycat QQ have achieved domestic hegemony. As Facebook, the company will, Kik innovative enterprises in silicon valley, a similar pattern, from Twitter to sina weibo, thousands of sites, from the company to the domestic from site to zhihu, from Kik to KiKi, also with an almost the speed of the difference of "zero" to the ground in the country. These "entrepreneurs" with innovation rings are passionate and fast-paced. They are familiar with all skills of communicating with the VC, know more with "I" is one of China's to mark their position, and to suggest the potential huge user base and revenue forecast.The domestic industry appears to have completed a process of "wholesale duplication without any business ethics barrier".According to schumpeter's point of view, the project is not "build a new production function", namely "the recombination of factors of production", natural hard to known as innovation, borrow the apple guru Steve jobs, they are only "copycat";" But the workarounds think that the more accurate version of the imitative activity should be fast follower,And the history of the computer industry has proved that these quick follow up with "innovation" as well as a better model, positioning and luck, completely can do it from behind.No matter how you characterize this "copy" activity, it will continue for a long time under the current institutional environment and the dual constraints of existing resources.The question is, what happens when two or more generations of companies develop this way?First, it will lead to a deterioration in the industrial environment. In Europe and America market, innovative small companies can be big business by IPO or acquisition and harvest success, large enterprises can through the internal innovation or acquisition of small business and stay ahead. At a critical stage of development, companies of different sizes have a benign interaction choice. But at home, the second generation of "copy" may be difficult to obtain a generation enterprise, because for the same item of innovation practice abroad, the domestic large and small enterprises on the cognition, learning, there is no absolute time lag. So we see the repetition of theimitation, the vicious competition, and the result is that the big companies will win, and the small businesses will be killed in the road. More critically, the proliferation of imitations will undoubtedly hurt real indigenous innovation in the country. Behind the "dog day", it reflects the voices of small businesses. Ultimately, this approach is useful for boosting GDP, but not for the ability to improve industrial innovation.Second, it would eliminate domestic companies' efforts to master the core technology of the industry. It's also hard to copy, especially in the short term, who doesn't want to pick one that's easier? With the "exit strategy" of the capital markets, how many people really care about the long-term vision of the company? Therefore, this business model can quickly from regiment campaign to thousand mess, but chips, mobile operating systems such as the key link of the participants has been very limited. Many of the ideas are simple: we can do incremental innovation without disruptive innovation; If we don't have the technology, we can do capacity; If no good application is developed, we still have enough users to fill in. But this expedient expediency is far from the real entrepreneurial spirit, nor the construction of the next generation of new business civilisations.So far, in the eyes of western mainstream manufacturers, China is still a "emerging markets", just a place of selling products, profit contribution, rather than the emergence of new technology and new model base. The European wind, which has been blowing since the last century, is still unrested. However, Chinese enterprises can not content to pick up multinational company missed business opportunities, but need to go one stepa footprint to gradually build industry innovation ability of lead.In a mature industry, domestic companies may be able to spend money to buy technology global patent pool, standing on the shoulders of giants, but when the mobile Internet that the turning point of arrival, from chip design, mobile operating system, the battery power consumption, and then to store huge amounts of industry applications, and even the Internet of things, cloud computing solutions in the industry, and so on, the market blank is right there, the rise of the opportunity is there, too.It should be encouraging and hopeful that some companies in the country will make their own operating systems or browsers in the near future.Innovation is the destiny of every entrepreneur. In this world have to attend a party, in fact, like Lady Gaga song sung, when "my friends all went to the carnival", the idea of a right is not "maybe I should stay in bed", but to think about "when at the end of the party, I will be the last one" the dance floor.。

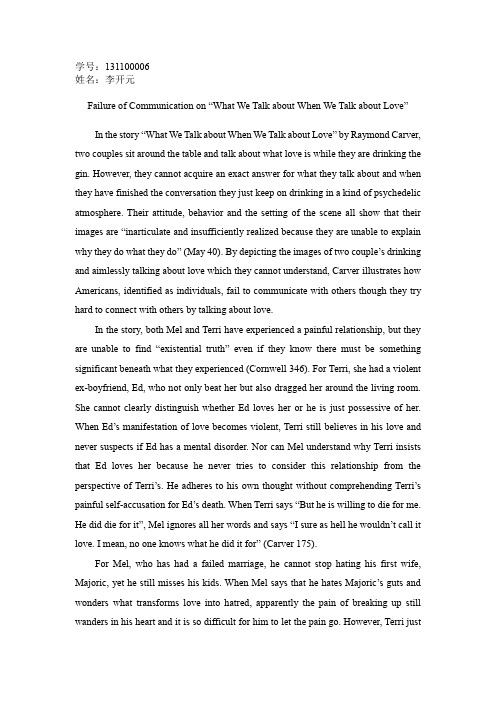

学号:131100006姓名:李开元Failure of Communication on “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love”In the story “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love” by Raymond Carver, two couples sit around the table and talk about what love is while they are drinking the gin. However, they cannot acquire an exact answer for what they talk about and when they have finished the conversation they just keep on drinking in a kind of psychedelic atmosphere. Their attitude, behavior and the setting of the scene all show that their images are “inarticulate and insufficiently realized because they are unable to explain why they do what they do” (May 40). By depicting the images of two couple’s drinking and aimlessly talking about love which they cannot understand, Carver illustrates how Americans, identified as individuals, fail to communicate with othersthough they try hard to connect with others by talking about love.In the story, both Mel and Terri have experienced a painful relationship, but they are unable to find “existential truth” even if they know there must be something significant beneath what they experienced (Cornwell 346). For Terri, she had a violent ex-boyfriend, Ed, who not only beat her but also dragged her around the living room. She cannot clearly distinguish whether Ed loves her or he is just possessive of her. When Ed’s manifestation of love becomes violent, Terri still believes in his love and never suspects if Ed has a mental disorder. Nor can Mel understand why Terri insists that Ed loves her because he never tries to consider this relationship from the perspective of Terri’s. He adheres to his own thought without comprehending Terri’s painful self-accusationfor Ed’s death. When Terri says “But he is willing to die for me. He did die for it”, Mel ignores all her words and says “I sure as hell he wouldn’t call it love. I mean, no one knows what he did it for” (Carver 175).For Mel, who has had a failed marriage, he cannot stop hating his first wife, Majoric, yet he still misses his kids. When Mel says that he hates Majoric’s guts and wonders what transforms love into hatred, apparently the pain of breaking up still wanders in his heart and it is so difficult for him to let the pain go. However, Terri justfocuses on their love in present and the alimony Mel pays without realizing Mel’s mean attitude to his ex-wife and the fact that he used to love Majoric as much as he loves herself. That is the reason why they cannot understan d what the “existential truth” brought by their life crises is (Cornwell 346).What is worse is that the characters in the story desperately appeal to talking as a valuable way to solve their doubts and relieve their pain. However, no matter how hard they try to communicate, their efforts do not take effect at all. Mel’s words prove it well: “Am I wrong? Am I way off base? Because I want you to set me straight if you think I’m wrong. I want to know. I mean, I don’t know anything, and I’m the first one to ad mit it” (Carver 177). Mel’s persistence in communicating with others on the subject of love brings no cure of his feelings of desolation and despair he experienced in his former relationship. Moreover, the characters are perplexed about what they want to illustrate, which makes it harder for them to communicate with others. When talking about an old couple who survive from a car accident, Mel mentions that miserable feeling was killing the old fart just because he couldn’t look at his wife with his blind eyes. However, nobody can understand his meaning so they all look at him silently. After failing to illuminate his thought clearly, Mel also fails to receive a satisfying response with which he could build connections with other people. When it comes to Terr i, she says “Oh now, wait awhile. I’m only kidding” while one second ago she was going to argue that Nick and Laura do not know what love is (Carver 175). Seeing the intimate couple Nick and Laura who are still at the stage of honey moon, Terri doubts her original thought, questioning herself if she is qualified to be skeptical of their love.At last,the listeners cannot realize the pain or the feelings the speakers want to express although they may have tried to understand the speeches. This failure not only causes their confusion about what love is, but also leads to the disappointment of the speaker. When Mel states his fantasy about coming back in a different life as a knight, Terri only points out a vocabulary mistake—“vassels” instead of “vessels” in his speech. As for Mel, a knight is “pretty safe wearing all that armor. It was all right being a knight until gunpowder and muskets and pistols came along” (Carver 180).The image of armor suggests that Mel lacks sense of safety in a relationship. However, Terri does not pay attention to that but focuses on the little vocabulary mistake. No wonder that Mel say “where the fuck’s the difference?” (Carver 181). Another example lies at the end of the story. The narrator states: “I could hea r my heart beating.I could hear everyone’s heart. I could hear the human noise we sat there making, not one of us moving, not one of us moving, no t even when the room went dark”( Carver 185). They have all been touched by Mel’s speech but they are unable to understand his point clearly. Therefore, they just keep sitting around the table and thinking about what Mel said and how his speech is related to their thoughts about love. They tend to remain incomprehensive rather than express their personal opinions or make a deeper level of discussion.In “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love”, the characters try to build connection with others by talking. However, their failure to communicate magnifies the fact that in the 1970s and 1980s, Americans from middle or lower class were disconnected from themselves and from those people with whom they are intimate. It isolates one as an individual in society and broadens the gap between people.Works CitedBrown, Arthur A. “Raymond Carver and Postmodern Humanism.” Critique (32): 127. Carver, Raymond. “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love” What We Talk about When We Talk about Love. New York: Vintage,1981.Cornwell, Gareth. “Mediated Desire and American Dissapointment in the Stories of Raymond Carver.”Critique (46): 346.May, Charles E. “Do You See What I’m Saying?.”North American Short Stories and Short Fictions200140.。

中国人如何开始寒暄及寒暄时的内容英语作文全文共6篇示例,供读者参考篇1How Chinese People Start Small Talk and What They Talk AboutHi there! Have you ever wondered how people in China start a conversation with someone they don't know very well? It's called small talk, and it's a way to break the ice and get to know someone better. In China, small talk is an important part of daily life篇2How Chinese People Do Small TalkHi there! My name is Xiaoming and I'm going to tell you all about how we Chinese people do small talk. Small talk is when you chat with someone about casual, everyday topics before getting into a bigger conversation. It's a way to be friendly and get to know each other a little bit.In China, we have some common ways to start a small talk conversation. One of the most popular is commenting on theweather. You could say something like "Wow, it's so hot today!" or "The sky is so blue and clear this morning." Weather is a safe topic that everyone can relate to.Another typical small talk opener is asking how someone is doing. Simple greetings like "How are you today?" or "How's it going?" show you are interested in the other person. Then they can respond with "I'm well, thanks for asking" or give a longer answer about their day so far.We might also make small talk by commenting on our surroundings if we're out somewhere. Like if you're at a restaurant, you could say "This place has such a nice atmosphere." Or at a park, you could remark "What a beautiful garden they have here."Sometimes to get a conversation going, Chinese people will ask casual questions like "What did you do this weekend?" or "Do you have any fun plans coming up?" It's a way to find common interests and learn a bit more about each other.Once small talk is flowing, we tend to chat about very common, everyday topics. A lot of times it's things like:Our jobs or work situationsFamily life and kidsHobbies, sports, or entertainment we enjoyRecent news, pop culture, or current eventsShared experiences like commuting, errands, appointmentsPlans or responsibilities coming up soonThe key is to keep things very light and relatable when doing small talk. We don't go too deep into heavy topics right away. It's just friendly chit-chat to get acquainted.For example, if someone mentions their job, you could follow up by asking "How long have you been doing that kind of work?" or "What does a typical day look like for you?" Keep the questions casual and easy to answer.When talking hobbies, you might say "I'm really into hiking. Have you ever gone on any good local trails?" Or for family chat, "I have two kids - a boy and a girl. Do you have any children?"See, it's just finding those little conversational paths you can meander down together for a bit before a bigger discussion. We're not solving world peace here! Just making friendly connections about the normal parts of life.Small talk lets you get a sense of what kinds of interests, experiences, or situations you might have in common withsomeone. From there, you can move into a longer chat about shared topics you mutually care about.I'd say in general, the goals of Chinese small talk are:To be polite, friendly, and make people feel comfortableTo find relatability and areas of common ground between youTo segue into more meaningful conversation if you wantBut you don't always need to go deep! Sometimes small talk is just for a casual, lighthearted moment while waiting in line, riding an elevator, or meeting someone new.Basically in China, small talk helps smooth over any awkwardness between people who don't know each other well yet. It's like the warm-up stretches before the real workout of a deeper discussion.Those are the basics I know so far about how us Chinese folks approach small talk. It's all about keeping things breezy, relatable, and putting people at ease through friendly chit-chat. Simple as that!Let me know if you have any other questions. I'd be happy to keep chatting more about the rituals of making casual conversation here.篇3How Chinese People Start Small Talk and What They Chat AboutHi there! My name is Xiaoming and I'm going to tell you all about how us Chinese people start little chit-chats and the kinds of things we talk about when we're just making small talk. It's really interesting!First off, starting a small talk conversation in China is a bit different than in some other countries. We don't usually just walk up to a stranger and say "Hi, how's it going?" That would be considered pretty rude here. Instead, there are a few common ways we start chatting with someone new.One really common way is to make a comment or compliment about something around you. Like if you see someone with a cute baby, you could say "Your baby is so adorable!" Or if it's raining, you could say "The rain is really coming down hard today, isn't it?" Making a lightheartedobservation is a nice way to start a little chat without seeming too forward.Another great way to start talking is to ask for small favors or give little bits of help. So if someone looks lost, you could ask "Excuse me, do you need help finding something?" Or if someone drops something, you can pick it up and hand it to them. Little acts of kindness are the perfect icebreaker!Once the small talk gets going, we tend to stick to some common, simple topics at first. The weather is always a great thing to discuss - you can never go wrong talking about if it's hot, cold, rainy, etc. Commenting on your surroundings is another easy option, like "This park is so beautiful!" or "The traffic is terrible today."We also often ask the basic getting-to-know-you questions like where someone is from, what they do for work, if they have family nearby, etc. But we don't go too deep at first, we keep it pretty light and friendly.After warming up with some easy chitchat, the conversation can go lots of different directions depending on the situation and the people involved. Sometimes it stays pretty surface level, especially if it's just a short interaction like waiting in line together.But if it's a more extended conversation, like with a neighbor or someone at a party, we'll often start discussing more substantive topics like:FamilyThis is a huge topic in Chinese culture! We love talking about our parents, grandparents, cousins, children, etc. Telling fun family stories or catching up on relatives' lives is very common. Family is everything to us.FoodShocker, right? Food is a major part of Chinese culture, so it's definitely a big conversation topic. We love talking about our favorite dishes, restaurants we've been to, crazy food experiences, family recipes, you name it. It's guaranteed to be a lively discussion!TravelWhether it's talking about places we've been or hearing about where others have traveled to, Chinese people are very interested in discussing different cities, countries, cultures, and travel adventures. It's a way for us to learn about the world.Current EventsNews, politics, the economy - these kinds of current event topics often come up, especially among older folks or those who are really into staying up-to-date on what's happening in the world and country. We examine things from all angles.EducationParents, grandparents, you name it - Chinese families place a huge emphasis on education. So you'll frequently hear people talking about schools, study routines, exam prep, tutors, and anything involving academics. It's a really big deal.Work & BusinessOf course jobs, companies, entrepreneurship, moneymaking opportunities, the economy - these kinds of career and business topics are widely discussed too. After family and food, work is probably the next biggest thing we like to chat about!Those are some of the major themes that tend to come up a lot in Chinese small talk and casual conversation. We cover a pretty wide range of topics once we get going! I probably missed some, but those are some of the biggest ones I've noticed.I love hearing snippets of conversation wherever I go - at the park, in restaurants, on the bus. There's always some lively discussion happening! Eavesdropping is my favorite way to pickup on the latest slang and hear about what's going on in people's lives.Well, that's pretty much all I can tell you about how we start chatting and the kinds of things we discuss. Hopefully this gives you a little peek into Chinese small talk culture. We're a pretty chatty, social bunch once you get us started! Let me know if you have any other questions.篇4How Chinese People Start Small Talk and What They Talk AboutHi there! My name is Xiao Ming, and I'm a 5th grader at a school in Beijing. Today, I'm going to tell you about how people in China start small talk and the kinds of things they talk about when making small talk.In China, it's really important to be polite and friendly when you meet someone new or see someone you know. We call this kind of friendly chit-chat "shuo peng hua" which means "to chat casually." It's a way to break the ice and make the other person feel comfortable.There are a few common ways that Chinese people start a conversation when they meet someone new or see an acquaintance. One way is to greet the person and ask how they are doing. For example, you might say "Ni hao, ni hao ma?" which means "Hello, how are you?" The other person will usually respond with "Wo hen hao, xie xie" meaning "I'm very well, thank you."Another way to start a casual conversation is to make a comment about the weather. In China, the weather is a super popular small talk topic! We might say something like "Jinr tian qi zhen bukan" which means "The weather is really nice today" or "Jinr zhen re" meaning "It's really hot today."If you're meeting someone new, it's also common to ask where they are from. You could say "Ni shi na-li ren?" which means "Where are you from?" Then the person would tell you what city or province they are from. This helps you get to know them a little bit.Once the conversation has started, there are lots of other topics that come up in Chinese small talk. Here are some examples:FamilyWe often ask about each other's families. Like "Ni you ji-ge xiong di jie mei?" means "How many brothers and sisters do you have?" Families are really important in Chinese culture.Work or SchoolIt's also normal to ask what someone does for work or what grade they are in at school. "Ni zuo shen-me gong-zuo?" means "What kind of work do you do?" And for students, you might ask "Ni xue-xi de zen-me-yang?" which means "How are your studies going?"Hobbies and InterestsChinese people are also curious to learn about each other's hobbies and interests during small talk. You could ask "Ni you shen-me ai-xing ma?" meaning "What are your hobbies?" Common hobbies people mention are reading, hiking, playing sports, etc.FoodOh man, Chinese people LOVE talking about food! It's like a national pastime. You'll often hear people chatting about their favorite dishes or restaurants. Like "Wo xiang chi Peking kaoya" which means "I feel like eating Peking duck."TravelTalking about places you've been or want to travel to is another fun small talk topic. Someone might say "Wo qu-nian qu-le Xianggang, hen piaoliangr" meaning "I went to Hong Kong last year, it's very beautiful."Those are some of the most common small talk topics and ways to start a casual conversation in China. The main goals are to be friendly, make the other person feel comfortable, and get to know a little bit about them.Sometimes, the small talk can go on for a long time, with people asking lots of follow-up questions about each other's lives and interests. Other times, it might just be a brief greeting and exchange before going your separate ways.Either way, making small talk and being warm and welcoming is just part of the culture here. It's how we start to build relationships and connections with both new people and those we already know a little.So the next time you're in China and someone starts chatting with you about the weather or where you're from, don't be shy! That's just the Chinese way of saying hello and getting to know you. Join in the friendly banter, and you'll fit right in.Well, that's all I have to share about Chinese small talk for now. Let me know if you have any other questions! I'll leave you with one more classic small talk phrase: "Zai jian, xiawu hao!" Which means "Goodbye, have a good afternoon!"篇5How Chinese People Do Small TalkHi there! My name is Xiaoming and I'm 10 years old. Today I want to tell you all about how we Chinese people do small talk. Small talk is when you chat with someone about casual, everyday topics - not anything too deep or serious. It's a way to be friendly and get to know someone a little bit.In China, we have certain ways of starting and doing small talk that might be a little different from other places. I'll explain it all to you based on what I've learned from my parents, teachers, and my own experiences. Let's get started!Starting a ConversationOne of the first things we tend to do when starting a casual conversation is greet the other person properly. We'll usually say "Nǐ hǎo" which just means "Hello" in English. But the way we sayit is important. It should be said sincerely with a slight nod of the head as a sign of respect.After the greeting, it's common to ask "Nǐ hǎo ma?" which means "How are you?" This shows you are interested in the other person's well-being and want to hear how they are doing. The polite response is to say "Hěn hǎo, xiè xie" which means "I'm very good, thank you."Then you can move into making some small talk. A typical way to start is with the weather. We might say something like "Jīntiān tiàqì hěn lěng" meaning "The weather is very cold today." Or if it's hot out, you could say "Jīntiān tiàqì zhēn re" which is "The weather is really hot today."Talking About Common TopicsOnce you've gotten the conversation going with a greeting and comment about the weather, you can move into other common small talk topics. Here are some examples of what Chinese people might chat about:Work/School"Nǐ jīntiān dàogàn le ma?" - "Did you go to work/school today?""Jīntiān gōngzuò/xuéxí màngmàng ma?" - "Waswork/studying busy today?"You could ask about their job, classes, teachers, etc.Family"Nǐ de jiārén dōu hěnhǎo ma?" - "Is your family all doing well?""Nǐyǒu jǐ gè xiǎopéngyǒu?" - "How many little friends (children) do you have?"Talking about spouses, parents, kids is very common.Food"Nǐ xǐhuān chī shénme zhǒngde cài?" - "What kind of dishes do you like to eat?""Zhèlǐ yǒu hěnduō hǎochī de fàndiàn" - "There are many good restaurants around here."Chinese people love talking about tasty foods and restaurants!Travel"Nǐ zuìjìn yǒu méiyǒu qù nǎlǐ lǚxíng?" - "Have you gone anywhere to travel recently?""Chūnjiē shí huì qù nǎlǐ lè?" - "Where will you go for the Spring Festival holiday?"With so many great destinations in China, travel is a big small talk topic.Hobbies"Nǐ zěnmebān xīuxi shíjiān?" - "How do you spend your free time?""Nǐ xǐhuān kàn diànying ma?" - "Do you like watching movies?"People often chat about fun hobbies like hiking, reading, movies, music, etc.Those are just some examples, but you get the idea! The key things are to keep it light, positive, and avoid anything too personal or controversial when doing small talk. It's just casual chatting to be friendly.Ending the ConversationWhen you're ready to end a small talk conversation, there are polite ways to do that too. You could say:"Duìbuqǐ, wǒ hāishì bànkuài jiàqǐle" - "Sorry, but I still have some things to take care of.""Xiànzài yǐjīng hěnwǎn le, xiàyícì zàijiàn" - "It's gotten quite late already, see you next time."The other person would likely say "Duìbuqǐ, săoráng nǐ" meaning "Sorry to have disturbed you" or just say "Zàijiàn" which is "Goodbye." You can also add "Xīngfúzāicí" which means "Have a nice day!"And that's pretty much how Chinese people handle small talk! We follow certain etiquette for greetings, stick to casual topics like those I mentioned, and know the polite ways to start and end the conversation. It's all about being friendly while still showing respect.I really hope this explanation has helped you understand Chinese small talk better. It's just one part of the rich traditions and culture here in China. Let me know if you have any other questions! Zàijiàn!篇6How Chinese People Start Small Talk and What They Talk AboutHi there! My name is Xiaoming and I'm 10 years old. Today I want to tell you about how us Chinese people start small talkconversations and the kinds of things we talk about when making small talk. Small talk is really important in Chinese culture to build relationships and friendships.When Chinese people first meet someone new, we usually start by introducing ourselves and asking the other person's name. Then we might ask where they are from or what they do for work. For example, I might say "Nice to meet you, my name is Xiaoming. What's your name? Where are you from?" The other person would then introduce themselves too.After the introductions, Chinese people often comment on the weather as a way to start some small talk. We might say something like "It's a beautiful sunny day today, isn't it?" or "The rain has been quite heavy recently." Talking about the weather is a really common small talk topic all over China.Another popular small talk topic is asking about someone's family. We believe family is very important in Chinese culture. So we might ask "Do you have any siblings?" or "Are you married? Do you have children?" It's considered polite to ask about someone's family when first meeting them.Food is also a subject that comes up a lot in Chinese small talk! We really love our food here. You might hear someone say "Have you tried any good restaurants around here lately?" or"What's your favorite Chinese dish?" Sometimes people will invite new friends over for a home-cooked meal.If you meet a Chinese person and they ask about your job or studies, don't be surprised! We see work and education as very important topics to discuss. An auntie might ask a student "What are you studying in school? What are your favorite subjects?" Or a uncle might ask someone "What company do you work for? How do you like your job?"For students like me, we often get asked about our hobbies and extracurricular activities during small talk. Adults are very interested in what kids do outside of school. I might get asked "What sports or instruments do you play? Do you have any fun hobbies?" Then I would talk about my hobby of playing badminton.You'll also find that Chinese people frequently comment on your appearance when first meeting you. Don't be offended - it is not considered rude here. You might hear someone say "You have such lovely long hair!" or "You've grown so tall!" We see these kinds of comments as compliments.Small talk doesn't have to be all questions though. Sometimes Chinese people will talk about major events happening in the world or in their city. Like I might say "Did yousee the news about the big soccer game last night? Our local team won!" Or if I met someone while traveling I might mention "There sure are a lot of tourists here this weekend for the holiday."When ending a small talk conversation, Chinese people don't usually say "It was nice talking to you" or anything like that. We're more likely to just smile, wave, and say "Bye, take care!" And we probably won't make direct eye contact the whole time - that can be seen as rude. But making small talk is considered very important for relationship building.Well, those are some of the most common small talk topics and ways that Chinese people start chatting when we first meet someone new. We cover things like the weather, family, food, jobs, hobbies, appearances, and major events. It's all about getting to know the other person a little better.I hope you found this overview interesting! Starting small talk conversations can seem a bit strange for people from other cultures at first. But once you get used to the common topics, you'll see that Chinese people are just trying to be friendly and make connections through casual chitchat. Let me know if you have any other questions!。

What do we talk about when we talk about happiness?You may feel sorry about a beggar sitting in the corner, but you will be surprised to be told that he has earned 20 odd yuan this day. And you may feel terrible about a white-collar who has been robbed of his little spare time, but you may not imagine he’s going to tell you that his dear wife has already cooked the chicken soup waiting for him at home. Moreover, a divorced housewife told you proudly that her son had won the first prize of his grade again. It seems that they are talking about the totally different things, but in fact, they are all sharing their happiness.People from all classes talk about happiness, though their happiness are seemingly different. Is it really so? Then what is the real happiness?I phoned my mom yesterday, and I asked her whether she’s living in happiness? She replied quickly, “of course I am”, so I went on to ask what the real happiness is. She scrupled a little, and said, “I don’t know, but I always felt happy maybe because of a sweet dream, nice weather, yummy food, or even just a phone call from you.” That’s a pretty typical expression made by an ordinary woman who is always grateful and satisfied with her life. At that moment, I thought I suddenly understood that real happiness is in our simplest satisfaction with life, and it probably is something ordinary existing in our life such as the beggar's contentment, the husband's reliance, and the son's achievement.In this hustle and bustle of the world, some may believe that gaining happiness must require preconditions such as money, fame or even beautiful appearance. But they all ignore, the small but heartwarming details all around us already include the real happiness, like 20 yuan from contented people, chicken soup thickly boiled with a wife's love, or transcript handed by a brilliant kid.So, happiness is just like the air, which is everywhere, though sometimes it is too common to be noticed. Now, at the end of my speech, shall we "take a deep breath" and feel what kind of happiness we are living in?封慧。

What do we talk about money阅读判断What do we talk about when we talk about money?We often think about what we can buy with the money we have,what we can’t buy because we don’t have enough and what we’re planning to buy when we have more.We discuss the careers that bring us money and the expenses that take it away.We talk about our favorite shops and restaurants,the causes we support,the places we’ve been and seen.We share dreams that only money can make real. In short,we talk about everything but money itself.In daily life,money is still a major conversational taboo.This is a shame,because money is at least as interesting as the things it does and buys,and the more you know about it,the more interesting it is.As a financial advisor,Iˊve seen hundreds of people learn to control their money instead of letting it control them watched as they increased their freedom,power and security by handling money consciously.Wouldn’t you like to know that you’ll always have enough money to live exactly as you want to?You’ll never be powerful in life until you’re powerful over your own money.Talking openly about it is the first step.1.People don’t think about what they can buy with money when they talk about money.A) TB) FC)D)2.Many people believe that only money can make our dreams come into being.A) TB) FC)D)3.In daily life,people often talk about money openly.A) TB) FC)D)4.Many people learn to handle money because they like money.A) TB) FC)D)5.Talking openly about money is the first step to control it.A) TB) FC)D)答案:(1)F(2)F(3)F(4)F(5)T。

英语信息科学英语30题1. In the world of information science, we often use a "computer" to process data. What does "process" mean?A. 生产B. 处理C. 进步D. 程序答案:B。

“process”常见释义为“处理”,A 选项“生产”通常用“produce”;C 选项“进步”常用“progress”;D 选项“程序”一般是“program”。

在信息科学中,用“computer”处理数据,“process”在此语境中表示“处理”。