如何阅读英语原著

- 格式:doc

- 大小:36.00 KB

- 文档页数:5

初中英语拓展阅读

以下是初中英语拓展阅读的一些建议:

1. 读英文原著:选择适合自己水平的英文原著,例如《小王子》、《哈利·波特》等。

通过阅读原著,可以接触到地道的英文表达方式,提高阅读

理解能力和词汇量。

2. 阅读新闻:选择适合自己水平的英文新闻,例如BBC、CNN等媒体的新闻。

通过阅读新闻,可以了解时事、扩大知识面,同时提高阅读速度和词汇量。

3. 读英文杂志:选择适合自己水平的英文杂志,例如《国家地理》、《时代周刊》等。

通过阅读杂志,可以了解各个领域的最新动态,提高阅读理解能力和拓展知识面。

4. 读英文小说:选择适合自己水平的英文小说,例如《简爱》、《了不起的盖茨比》等。

通过阅读小说,可以培养英语语感,提高阅读理解能力和欣赏能力。

5. 做英文练习册:选择适合自己水平的英文练习册,例如《剑桥英语阅读》、《托福阅读突破》等。

通过做练习册,可以巩固阅读基础,提高阅读速度和解题能力。

6. 看英文电影和电视剧:选择适合自己水平的英文电影和电视剧,例如《哈利·波特》、《生活大爆炸》等。

通过观看电影和电视剧,可以提高听力理解能力和口语表达能力。

总之,初中英语拓展阅读需要注重材料的选取和方法的指导。

通过多种形式的阅读活动,可以提高英语阅读能力和拓展知识面。

RIDERS TO THE SEAby J. M. SYNGEINTRODUCTIONIt must have been on Synge's second visit to the Aran Islands that he had the experience out of which was wrought what many believe to be his greatest play. The scene of "Riders to the Sea" is laid in a cottage on Inishmaan, the middle and most interesting island of the Aran group. While Synge was on Inishmaan, the story came to him of a man whose body had been washed up on the far away coast of Donegal, and who, by reason of certain peculiarities of dress, was suspected to be from the island. In due course, he was recognised as a native of Inishmaan, in exactly the manner described in the play, and perhaps one of the most poignantly vivid passages in Synge's book on "The Aran Islands" relates the incident of his burial.The other element in the story which Synge introduces into the play is equally true. Many tales of "second sight" are to be heard among Celtic races. In fact, they are so common as to arouse little or no wonder in the minds of the people. It is just such a tale, which there seems no valid reason for doubting, that Synge heard, and that gave the title, "Riders to the Sea", to his play. It is the dramatist's high distinction that he has simply taken the materials which lay ready to his hand, and by the power of sympathy woven them, with little modification, into a tragedy which, for dramatic irony and noble pity, has no equal among its contemporaries. Great tragedy, it is frequently claimed with some show of justice, has perforce departed with the advance of modern life and its complicated tangle of interests and creature comforts. A highly developed civilisation, with its attendant specialisation of culture, tends ever to lose sight of those elemental forces, those primal emotions, naked to wind and sky, which are the stuff from which great drama is wrought by the artist, but which, as it would seem, are rapidly departing from us. It is only in the far places, where solitary communion may be had with the elements, that this dynamic life is still to be found continuously, and it is accordingly thither that the dramatist, who would deal with spiritual life disengaged from the environment of an intellectual maze, must go for that experience whichwill beget in him inspiration for his art. The Aran Islands from which Synge gained his inspiration are rapidly losing that sense of isolation and self-dependence, which has hitherto been their rare distinction, and which furnished the motivation for Synge's masterpiece. Whether or not Synge finds a successor, it is none the less true that in English dramatic literature "Riders to the Sea" has an historic value which it would be difficult to over-estimate in its accomplishment and its possibilities. A writer in The Manchester Guardian shortly after Synge's death phrased it rightly when he wrote that it is "the tragic masterpiece of our language in our time; wherever it has been played in Europe from Galway to Prague, it has made the word tragedy mean something more profoundly stirring and cleansing to the spirit than it did."The secret of the play's power is its capacity for standing afar off, and mingling, if we may say so, sympathy with relentlessness. There is a wonderful beauty of speech in the words of every character, wherein the latent power of suggestion is almost unlimited. "In the big world the old people do be leaving things after them for their sons and children, but in this place it is the young men do be leaving things behind for them that do be old." In the quavering rhythm of these words, there is poignantly present that quality of strangeness and remoteness in beauty which, as we are coming to realise, is the touchstone of Celtic literary art. However, the very asceticism of the play has begotten a corresponding power which lifts Synge's work far out of the current of the Irish literary revival, and sets it high in a timeless atmosphere of universal action.Its characters live and die. It is their virtue in life to be lonely, and none but the lonely man in tragedy may be great. He dies, and then it is the virtue in life of the women mothers and wives and sisters to be great in their loneliness, great as Maurya, the stricken mother, is great in her final word."Michael has a clean burial in the far north, by the grace of the Almighty God. Bartley will have a fine coffin out of the white boards, and a deep grave surely. What more can we want than that? No man at all can be living for ever, and we must be satisfied." The pity and the terror of it all have brought a great peace, the peace that passethunderstanding, and it is because the play holds this timeless peace after the storm which has bowed down every character, that "Riders to the Sea" may rightly take its place as the greatest modern tragedy in the English tongue.EDWARD J. O'BRIEN.February 23, 1911.PERSONSMAURYA (an old woman) . . . Honor Lavelle BARTLEY (her son) ............. W. G. Fay CATHLEEN (her daughter). .....Sarah Allgood NORA (a younger daughter). . Emma Vernon MEN AND WOMENRIDERS TO THE SEAA PLAY IN ONE ACTFirst performed at the Molesworth Hall, Dublin, February 25th, 1904.SCENE. -- An Island off the West of Ireland. (Cottage kitchen, with nets, oil-skins, spinning wheel, some new boards standing by the wall, etc. Cathleen, a girl of about twenty, finishes kneading cake, and puts it down in the pot-oven by the fire; then wipes her hands, and begins to spin at the wheel. NORA, a young girl, puts her head in at the door.)NORA [In a low voice.]Where is she?CATHLEEN She's lying down, God help her, and may be sleeping, if she's able.[Nora comes in softly, and takes a bundle from under her shawl.]CATHLEEN [Spinning the wheel rapidly.]What is it you have?NORA The young priest is after bringing them. It's a shirt and a plain stocking were got off a drowned man in Donegal.[Cathleen stops her wheel with a sudden movement, and leans out to listen.]NORA We're to find out if it's Michael's they are, some time herself will be down looking by the sea.CATHLEEN How would they be Michael's, Nora. How would he go the length of that way to the far north?NORA The young priest says he's known the like of it. "If it's Michael's they are," says he, "you can tell herself he's got a clean burial by the grace of God, and if they're not his, let no one say a word about them, for she'll be getting her death," says he, "with crying and lamenting."[The door which Nora half closed is blown open by a gust of wind.] CATHLEEN [Looking out anxiously.]Did you ask him would he stop Bartley going this day with the horses to the Galway fair?NORA "I won't stop him," says he, "but let you not be afraid. Herself does be saying prayers half through the night, and the Almighty God won't leave her destitute," says he, "with no son living."CATHLEEN Is the sea bad by the white rocks, Nora?NORA Middling bad, God help us. There's a great roaring in the west, and it's worse it'll be getting when the tide's turned to the wind.[She goes over to the table with the bundle.]Shall I open it now?CATHLEEN Maybe she'd wake up on us, and come in before we'd done.[Coming to the table.]It's a long time we'll be, and the two of us crying.NORA [Goes to the inner door and listens.]She's moving about on the bed. She'll be coming in a minute.CATHLEEN Give me the ladder, and I'll put them up in the turf-loft, the way she won't know of them at all, and maybe when the tide turnsshe'll be going down to see would he be floating from the east.[They put the ladder against the gable of the chimney; Cathleen goes up a few steps and hides the bundle in the turf-loft. Maurya comes from the inner room.]MAURYA [Looking up at Cathleen and speaking querulously.]Isn't it turf enough you have for this day and evening?CATHLEEN There's a cake baking at the fire for a short space. [Throwing down the turf] and Bartley will want it when the tide turns if he goes to Connemara.[Nora picks up the turf and puts it round the pot-oven.]MAURYA [Sitting down on a stool at the fire.]He won't go this day with the wind rising from the south and west.He won't go this day, for the young priest will stop him surely.NORA He'll not stop him, mother, and I heard Eamon Simon and Stephen Pheety and Colum Shawn saying he would go.MAURYA Where is he itself?NORA He went down to see would there be another boat sailing in the week, and I'm thinking it won't be long till he's here now, for the tide'sturning at the green head, and the hooker' tacking from the east.CATHLEEN I hear some one passing the big stones.NORA [Looking out.]He's coming now, and he in a hurry.BARTLEY [Comes in and looks round the room. Speaking sadly and quietly.]Where is the bit of new rope, Cathleen, was bought in Connemara?CATHLEEN [Coming down.]Give it to him, Nora; it's on a nail by the white boards. I hung it up this morning, for the pig with the black feet was eating it.NORA [Giving him a rope.]Is that it, Bartley?MAURYA You'd do right to leave that rope, Bartley, hanging by the boards (Bartley takes the rope]). It will be wanting in this place, I'm telling you, if Michael is washed up to-morrow morning, or the next morning, or any morning in the week, for it's a deep grave we'll make him by the grace of God.BARTLEY [Beginning to work with the rope.]I've no halter the way I can ride down on the mare, and I must go now quickly. This is the one boat going for two weeks or beyond it, and the fair will be a good fair for horses I heard them saying below.MAURYA It's a hard thing they'll be saying below if the body is washed up and there's no man in it to make the coffin, and I after giving a big price for the finest white boards you'd find in Connemara.[She looks round at the boards.]BARTLEY How would it be washed up, and we after looking each day for nine days, and a strong wind blowing a while back from the west and south?MAURYA If it wasn't found itself, that wind is raising the sea, and there was a star up against the moon, and it rising in the night. If it was a hundred horses, or a thousand horses you had itself, what is the price of a thousand horses against a son where there is one son only?BARTLEY [Working at the halter, to Cathleen.]Let you go down each day, and see the sheep aren't jumping in on therye, and if the jobber comes you can sell the pig with the black feet if there is a good price going.MAURYA How would the like of her get a good price for a pig?BARTLEY [To Cathleen]If the west wind holds with the last bit of the moon let you and Nora get up weed enough for another cock for the kelp. It's hard set we'll be from this day with no one in it but one man to work.MAURYA It's hard set we'll be surely the day you're drownd'd with the rest. What way will I live and the girls with me, and I an old woman looking for the grave?[Bartley lays down the halter, takes off his old coat, and puts on a newer one of the same flannel.]BARTLEY [To Nora.]Is she coming to the pier?NORA [Looking out.] She's passing the green head and letting fall her sails.BARTLEY [Getting his purse and tobacco.]I'll have half an hour to go down, and you'll see me coming again in two days, or in three days, or maybe in four days if the wind is bad.MAURYA [Turning round to the fire, and putting her shawl over her head.]Isn't it a hard and cruel man won't hear a word from an old woman, and she holding him from the sea?CATHLEEN It's the life of a young man to be going on the sea, and who would listen to an old woman with one thing and she saying it over?BARTLEY [Taking the halter.]I must go now quickly. I'll ride down on the red mare, and the gray pony'll run behind me. . . The blessing of God on you.[He goes out.]MAURYA [Crying out as he is in the door.]He's gone now, God spare us, and we'll not see him again. He's gone now, and when the black night is falling I'll have no son left me in the world.CATHLEEN Why wouldn't you give him your blessing and he lookinground in the door? Isn't it sorrow enough is on every one in this house without your sending him out with an unlucky word behind him, and a hard word in his ear?[Maurya takes up the tongs and begins raking the fire aimlessly without looking round.]NORA [Turning towards her.]You're taking away the turf from the cake.CATHLEEN [Crying out.]The Son of God forgive us, Nora, we're after forgetting his bit of bread.[She comes over to the fire.]NORA And it's destroyed he'll be going till dark night, and he after eating nothing since the sun went up.CATHLEEN [Turning the cake out of the oven.]It's destroyed he'll be, surely. There's no sense left on any person in a house where an old woman will be talking for ever.[Maurya sways herself on her stool.]CATHLEEN [Cutting off some of the bread and rolling it in a cloth; to Maurya.]Let you go down now to the spring well and give him this and he passing. You'll see him then and the dark word will be broken, and you can say "God speed you," the way he'll be easy in his mind.MAURYA [Taking the bread.]Will I be in it as soon as himself?CATHLEEN If you go now quickly.MAURYA [Standing up unsteadily.]It's hard set I am to walk.CATHLEEN [Looking at her anxiously.]Give her the stick, Nora, or maybe she'll slip on the big stones.NORA What stick?CATHLEEN The stick Michael brought from Connemara.MAURYA [Taking a stick Nora gives her.]In the big world the old people do be leaving things after them for their sons and children, but in this place it is the young men do be leavingthings behind for them that do be old.[She goes out slowly. Nora goes over to the ladder.]CATHLEEN Wait, Nora, maybe she'd turn back quickly. She's that sorry, God help her, you wouldn't know the thing she'd do.NORA Is she gone round by the bush?CATHLEEN [Looking out.]She's gone now. Throw it down quickly, for the Lord knows when she'll be out of it again.NORA [Getting the bundle from the loft.]The young priest said he'd be passing to-morrow, and we might go down and speak to him below if it's Michael's they are surely.CATHLEEN [Taking the bundle.]Did he say what way they were found?NORA [Coming down.]"There were two men," says he, "and they rowing round with poteen before the cocks crowed, and the oar of one of them caught the body, and they passing the black cliffs of the north."CATHLEEN [Trying to open the bundle.]Give me a knife, Nora, the string's perished with the salt water, and there's a black knot on it you wouldn't loosen in a week.NORA [Giving her a knife.]I've heard tell it was a long way to Donegal.CATHLEEN [Cutting the string.]It is surely. There was a man in here a while ago -- the man sold us that knife -- and he said if you set off walking from the rocks beyond, it would be seven days you'd be in Donegal.NORA And what time would a man take, and he floating?[Cathleen opens the bundle and takes out a bit of a stocking. They look at them eagerly.]CATHLEEN [In a low voice.]The Lord spare us, Nora! isn't it a queer hard thing to say if it's his they are surely?NORA I'll get his shirt off the hook the way we can put the one flannel on the other [she looks through some clothes hanging in the corner.] It'snot with them, Cathleen, and where will it be?CATHLEEN I'm thinking Bartley put it on him in the morning, for his own shirt was heavy with the salt in it [pointing to the corner]. There's a bit of a sleeve was of the same stuff. Give me that and it will do.[Nora brings it to her and they compare the flannel.]CATHLEEN It's the same stuff, Nora; but if it is itself aren't there great rolls of it in the shops of Galway, and isn't it many another man may have a shirt of it as well as Michael himself?NORA [Who has taken up the stocking and counted the stitches, crying out.]It's Michael, Cathleen, it's Michael; God spare his soul, and what will herself say when she hears this story, and Bartley on the sea?CATHLEEN [Taking the stocking.]It's a plain stocking.NORA It's the second one of the third pair I knitted, and I put up three score stitches, and I dropped four of them.CATHLEEN [Counts the stitches.]It's that number is in it [crying out.] Ah, Nora, isn't it a bitter thing to think of him floating that way to the far north, and no one to keen him but the black hags that do be flying on the sea?NORA [Swinging herself round, and throwing out her arms on the clothes.]And isn't it a pitiful thing when there is nothing left of a man who was a great rower and fisher, but a bit of an old shirt and a plain stocking?CATHLEEN [After an instant.]Tell me is herself coming, Nora? I hear a little sound on the path.NORA [Looking out.]She is, Cathleen. She's coming up to the door.CATHLEEN Put these things away before she'll come in. Maybe it's easier she'll be after giving her blessing to Bartley, and we won't let on we've heard anything the time he's on the sea.NORA [Helping Cathleen to close the bundle.]We'll put them here in the corner.[They put them into a hole in the chimney corner. Cathleen goesback to the spinning-wheel.]NORA Will she see it was crying I was?CATHLEEN Keep your back to the door the way the light'll not be on you.[Nora sits down at the chimney corner, with her back to the door. Maurya comes in very slowly, without looking at the girls, and goes over to her stool at the other side of the fire. The cloth with the bread is still in her hand. The girls look at each other, and Nora points to the bundle of bread.]CATHLEEN [After spinning for a moment.]You didn't give him his bit of bread?[Maurya begins to keen softly, without turning round.]CATHLEEN Did you see him riding down?[Maurya goes on keening.]CATHLEEN [A little impatiently.]God forgive you; isn't it a better thing to raise your voice and tell what you seen, than to be making lamentation for a thing that's done? Did you see Bartley, I'm saying to you? MAURYA [With a weak voice.] My heart's broken from this day.CATHLEEN [As before.]Did you see Bartley?MAURYA I seen the fearfulest thing.CATHLEEN [Leaves her wheel and looks out.]God forgive you; he's riding the mare now over the green head, andthe gray pony behind him.MAURYA [Starts, so that her shawl falls back from her head and shows her white tossed hair. With a frightened voice.]The gray pony behind him.CATHLEEN [Coming to the fire.]What is it ails you, at all?MAURYA [Speaking very slowly.]I've seen the fearfulest thing any person has seen, since the day Bride Dara seen the dead man with the child in his arms.CATHLEEN AND NORA Uah.[They crouch down in front of the old woman at the fire.]NORA Tell us what it is you seen.MAURYA I went down to the spring well, and I stood there saying a prayer to myself. Then Bartley came along, and he riding on the red mare with the gray pony behind him [she puts up her hands, as if to hide something from her eyes.] The Son of God spare us, Nora!CATHLEEN What is it you seen.MAURYA I seen Michael himself.CATHLEEN [Speaking softly.]You did not, mother; it wasn't Michael you seen, for his body is after being found in the far north, and he's got a clean burial by the grace of God.MAURYA [A little defiantly.]I'm after seeing him this day, and he riding and galloping. Bartley came first on the red mare; and I tried to say "God speed you," but something choked the words in my throat. He went by quickly; and "the blessing of God on you," says he, and I could say nothing. I looked up then, and I crying, at the gray pony, and there was Michael upon it -- with fine clothes on him, and new shoes on his feet.CATHLEEN [Begins to keen.]It's destroyed we are from this day. It's destroyed, surely.NORA Didn't the young priest say the Almighty God wouldn't leave her destitute with no son living?MAURYA [In a low voice, but clearly.]It's little the like of him knows of the sea. ............... Bartley will be lost now, and let you call in Eamon and make me a good coffin out of the white boards, for I won't live after them. I've had a husband, and a husband's father, and six sons in this house -- six fine men, though it was a hard birth I had with every one of them and they coming to the world -- and some of them were found and some of them were not found, but they're gone now the lot of them .............. There were Stephen, and Shawn, were lost in the great wind, and found after in the Bay of Gregory of the Golden Mouth, and carried up the two of them on the one plank, and in by that door.[She pauses for a moment, the girls start as if they heard something through the door that is half open behind them.]NORA [In a whisper.]Did you hear that, Cathleen? Did you hear a noise in the north-east?CATHLEEN [In a whisper.]There's some one after crying out by the seashore.MAURYA [Continues without hearing anything.]There was Sheamus and his father, and his own father again, were lost in a dark night, and not a stick or sign was seen of them when the sun went up. There was Patch after was drowned out of a curagh that turned over.I was sitting here with Bartley, and he a baby, lying on my two knees, and I seen two women, and three women, and four women coming in, and they crossing themselves, and not saying a word. I looked out then, and there were men coming after them, and they holding a thing in the half of a red sail, and water dripping out of it -- it was a dry day, Nora -- and leaving a track to the door.[She pauses again with her hand stretched out towards the door. It opens softly and old women begin to come in, crossing themselves on the threshold, and kneeling down in front of the stage with red petticoats over their heads.]MAURYA [Half in a dream, to Cathleen.]Is it Patch, or Michael, or what is it at all?CATHLEEN Michael is after being found in the far north, and when he is found there how could he be here in this place?MAURYA There does be a power of young men floating round in the sea, and what way would they know if it was Michael they had, or another man like him, for when a man is nine days in the sea, and the wind blowing, it's hard set his own mother would be to say what man was it.CATHLEEN It's Michael, God spare him, for they're after sending us a bit of his clothes from the far north.[She reaches out and hands Maurya the clothes that belonged to Michael. Maurya stands up slowly, and takes them into her hands. NORA looks out.]NORA They're carrying a thing among them and there's water drippingout of it and leaving a track by the big stones.CATHLEEN [In a whisper to the women who have come in.]Is it Bartley it is?ONE OF THE WOMEN It is surely, God rest his soul.[Two younger women come in and pull out the table. Then men carry in the body of Bartley, laid on a plank, with a bit of a sail over it, and lay it on the table.]CATHLEEN [To the women, as they are doing so.]What way was he drowned?ONE OF THE WOMEN The gray pony knocked him into the sea, and he was washed out where there is a great surf on the white rocks.[Maurya has gone over and knelt down at the head of the table. The women are keening softly and swaying themselves with a slow movement. Cathleen and Nora kneel at the other end of the table. The men kneel near the door.]MAURYA [Raising her head and speaking as if she did not see the people around her.]They're all gone now, and there isn't anything more the sea can do to me. . . . I'll have no call now to be up crying and praying when the wind breaks from the south, and you can hear the surf is in the east, and the surf is in the west, making a great stir with the two noises, and they hitting one on the other. I'll have no call now to be going down and getting Holy Water in the dark nights after Samhain, and I won't care what way the sea is when the other women will be keening. To Nora]. Give me the Holy Water, Nora, there's a small sup still on the dresser.[Nora gives it to her.]MAURYA [Drops Michael's clothes across Bartley's feet, and sprinkles the Holy Water over him.]It isn't that I haven't prayed for you, Bartley, to the Almighty God. It isn't that I haven't said prayers in the dark night till you wouldn't know what I'ld be saying; but it's a great rest I'll have now, and it's time surely. It's a great rest I'll have now, and great sleeping in the long nights after Samhain, if it's only a bit of wet flour we do have to eat, and maybe a fish that would be stinking.[She kneels down again, crossing herself, and saying prayers under her breath.]CATHLEEN [To an old man.]Maybe yourself and Eamon would make a coffin when the sun rises. We have fine white boards herself bought, God help her, thinking Michael would be found, and I have a new cake you can eat while you'll be working.THE OLD MAN [Looking at the boards.]Are there nails with them?CATHLEEN There are not, Colum; we didn't think of the nails.ANOTHER MAN It's a great wonder she wouldn't think of the nails, and all the coffins she's seen made already.CATHLEEN It's getting old she is, and broken.[Maurya stands up again very slowly and spreads out the pieces of Michael's clothes beside the body, sprinkling them with the last of the Holy Water.]NORA [In a whisper to Cathleen.]She's quiet now and easy; but the day Michael was drowned you could hear her crying out from this to the spring well. It's fonder she was of Michael, and would any one have thought that? CATHLEEN [Slowly and clearly.]An old woman will be soon tired with anything she will do, and isn't it nine days herself is after crying and keening, and making great sorrow in the house?MAURYA [Puts the empty cup mouth downwards on the table, and lays her hands together on Bartley's feet.]They're all together this time, and the end is come. May the Almighty God have mercy on Bartley's soul, and on Michael's soul, and on the souls of Sheamus and Patch, and Stephen and Shawn (bending her head]); and may He have mercy on my soul, Nora, and on the soul of every one is left living in the world.[She pauses, and the keen rises a little more loudly from the women, then sinks away.]MAURYA [Continuing.]Michael has a clean burial in the far north, by the grace of the Almighty God. Bartley will have a fine coffin out of the white boards, and a deep grave surely. What more can we want than that? No man at all can be living for ever, and we must be satisfied.[She kneels down again and the curtain falls slowly.]。

英语记叙文阅读答题方法与技巧近年来,英语记叙文阅读在高中英语考试中扮演着越来越重要的角色。

掌握好阅读答题方法和技巧,对于学生提高英语成绩至关重要。

下面,我将从阅读答题方法、技巧和个人理解几个方面为大家详细介绍。

一、阅读答题方法对于英语记叙文阅读,首先要明确题目的要求,结合题目中的指示词,有的放矢地进行阅读。

在快速阅读时,要注意把握文章的脉络,明确文章的主题和大意。

抓住关键信息,譬如人物、事件、时间、地点等,这有助于思考后续的问题。

在精读过程中,要注重细节,尤其是对一些名词解释、原因阐述等要格外留意。

要善于利用上下文的理解和判断能力,以便更好地理解作者之意。

当遇到难句或不认识的生词时,不妨通过上下文推测生词的含义,以免耽误速度。

二、阅读答题技巧要做到审题审仔细,确保对问题的理解准确,因为有些问题可能会有陷阱。

要善于总结归纳,要根据文章的内容来进行整合,不可片面理解。

要注意考虑作者的意图和态度,分析文章的写作目的和文体特点,有利于理解作者的用词和表达。

在回答问题时,要简洁明了,重点突出,不要在答案中涉及无关信息。

可以通过引用原文来支持自己的观点,以展现自己对文章的理解。

要检查答案,看是否有语言或逻辑错误,避免疏忽大意,提高答题的准确性。

三、个人观点和理解对于阅读答题方法的个人理解,我认为阅读不只是为了应付考试,更是为了拓展知识面、增加思维广度和深度的过程。

平时多读书、多阅读一些优秀的英语记叙文,可以帮助提高阅读能力和阅读理解水平。

要注意培养自己的归纳总结能力,在总结中发现问题和不足,持续优化自己的阅读方法。

总结回顾在总结方面,我们可以归纳出以下几点:1. 对于英语记叙文阅读,应该做到快速阅读和精读相结合,注重细节,抓住关键信息,善于利用上下文推测生词的含义。

2. 在答题时,要审题审仔细,注意总结归纳,善于分析作者的意图和态度,简洁明了地回答问题,最后检查答案。

3. 在平时的阅读中,要多读书、多阅读优秀英语记叙文,培养归纳总结能力,持续优化阅读方法,不断提高阅读理解水平。

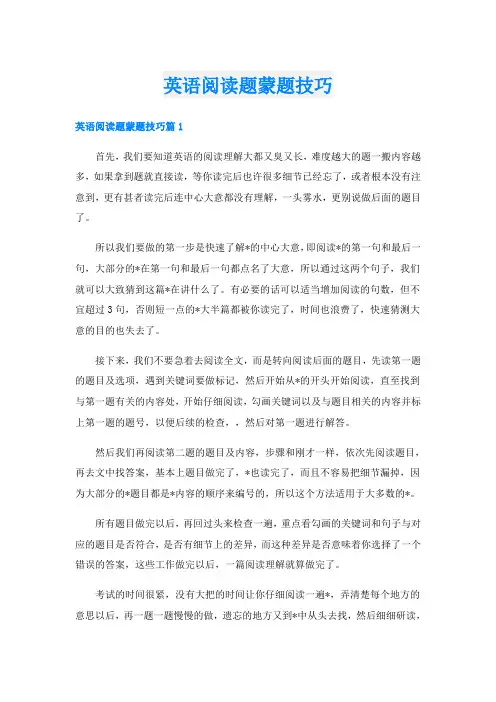

英语阅读题蒙题技巧英语阅读题蒙题技巧篇1首先,我们要知道英语的阅读理解大都又臭又长,难度越大的题一搬内容越多,如果拿到题就直接读,等你读完后也许很多细节已经忘了,或者根本没有注意到,更有甚者读完后连中心大意都没有理解,一头雾水,更别说做后面的题目了。

所以我们要做的第一步是快速了解*的中心大意,即阅读*的第一句和最后一句,大部分的*在第一句和最后一句都点名了大意,所以通过这两个句子,我们就可以大致猜到这篇*在讲什么了。

有必要的话可以适当增加阅读的句数,但不宜超过3句,否则短一点的*大半篇都被你读完了,时间也浪费了,快速猜测大意的目的也失去了。

接下来,我们不要急着去阅读全文,而是转向阅读后面的题目,先读第一题的题目及选项,遇到关键词要做标记,然后开始从*的开头开始阅读,直至找到与第一题有关的内容处,开始仔细阅读,勾画关键词以及与题目相关的内容并标上第一题的题号,以便后续的检查,,然后对第一题进行解答。

然后我们再阅读第二题的题目及内容,步骤和刚才一样,依次先阅读题目,再去文中找答案,基本上题目做完了,*也读完了,而且不容易把细节漏掉,因为大部分的*题目都是*内容的顺序来编号的,所以这个方法适用于大多数的*。

所有题目做完以后,再回过头来检查一遍,重点看勾画的关键词和句子与对应的题目是否符合,是否有细节上的差异,而这种差异是否意味着你选择了一个错误的答案,这些工作做完以后,一篇阅读理解就算做完了。

考试的时间很紧,没有大把的时间让你仔细阅读一遍*,弄清楚每个地方的意思以后,再一题一题慢慢的做,遗忘的地方又到*中从头去找,然后细细研读,最后在细细的重读全文及题目检查答案,所以在上述这种快速定位正确答案的方法才能在考试中节约时间。

当然,光有方法还是不够的,我们更需要的是多加练习和仔细体会其中的规律与技巧,没有什么是可以一蹴而就的,一步一步脚踏实地,认真努力的做好每一次练习,日积月累才能由量变引起质变,勤奋才是成功的秘诀!英语阅读题蒙题技巧篇2先看题目后看*。

Chancefavors the prepared mind、英语原著读写指导教学流程(一) 如设置故事悬念?1、理论基础格式塔心理学派认为, 人们通过感官知觉得到得就是一个个“完形”,当人们在观瞧到一个不规则, 不完满得形状时, 就会产生一种在得紧力。

这种力迫使大脑皮层紧地活动,以填补“缺陷”, 能给人以意觉上得不完满感, 因此,在阅读前巧设悬念,就能激发学生得好奇心与求知欲,使其思维处于一种激动状态,产生一种非弄清不可得探究心理.2、设置故事悬念技巧与电视节目预告一样,教师先把小说得魅力、事情得高潮、结果之中某个突出得片断得故事讲给学生听,让学生不由自主地产生究根究底得愿望,自然地在教师得带领下进入阅读得大门。

(二) 如梳理小说中得人物关系?把握好人物关系, 就是理解小说得关键,可以通过建立人物关系思维导图得式,理清小说中得人物关系。

(三) 如梳理小说得故事情节?ﻫ把握好故事情节,就是读懂小说得关键。

故事情节梳理通常从故事得开始, 发展,高潮与结束四个环节着手。

(四) 如概括故事大意(summary)?ﻫ概括故事大意就是培养学生归纳概括能力得有效途径之一。

概1)依据故事情节.括故事大意可以从以下三个面着手。

ﻫ2)故事大意得五要素:when, where, who, what,how、3 )写故事大意常用关联词语:atfirst,then,after that, later, inthe end/finally /eventually/at last、(五) 如进行主题归纳(阅读启发与思考)小说得主题就是小说得灵魂,就是作者得写作目得所在,也就是作品得价值意义之所在。

主题归纳通常从小说得人物形象与某些细节入手.如《弗兰肯斯坦》归纳主题.ﻫ(六)如进行主题归纳(阅读启发与思考)ﻫ(九)写作指导—提高篇英语原著《弗兰肯斯坦》读写指导课例一.《弗兰肯斯坦》悬念设置One stormy night a horriblescream came from aroom in a hotel suddenly、F rankenstein rushedthere, only tofindhis newly- married wife lying in blood with her heart taken out、Who was the murderer? Why was the murder so brutal?(一个狂风暴雨之夜,突然从一个旅馆得房间里传来一声可怕得尖叫声。

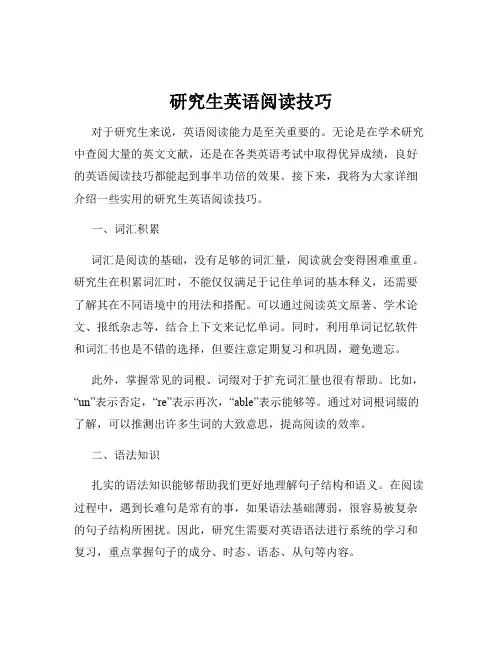

研究生英语阅读技巧对于研究生来说,英语阅读能力是至关重要的。

无论是在学术研究中查阅大量的英文文献,还是在各类英语考试中取得优异成绩,良好的英语阅读技巧都能起到事半功倍的效果。

接下来,我将为大家详细介绍一些实用的研究生英语阅读技巧。

一、词汇积累词汇是阅读的基础,没有足够的词汇量,阅读就会变得困难重重。

研究生在积累词汇时,不能仅仅满足于记住单词的基本释义,还需要了解其在不同语境中的用法和搭配。

可以通过阅读英文原著、学术论文、报纸杂志等,结合上下文来记忆单词。

同时,利用单词记忆软件和词汇书也是不错的选择,但要注意定期复习和巩固,避免遗忘。

此外,掌握常见的词根、词缀对于扩充词汇量也很有帮助。

比如,“un”表示否定,“re”表示再次,“able”表示能够等。

通过对词根词缀的了解,可以推测出许多生词的大致意思,提高阅读的效率。

二、语法知识扎实的语法知识能够帮助我们更好地理解句子结构和语义。

在阅读过程中,遇到长难句是常有的事,如果语法基础薄弱,很容易被复杂的句子结构所困扰。

因此,研究生需要对英语语法进行系统的学习和复习,重点掌握句子的成分、时态、语态、从句等内容。

当遇到长难句时,不要被其长度吓倒,可以先找出句子的主干,即主语、谓语和宾语,然后再分析修饰成分,如定语、状语和补语等。

通过这样的分解和分析,能够更清晰地理解句子的意思。

三、阅读速度提高阅读速度是研究生英语阅读的一个重要目标。

但需要注意的是,提高速度不能以牺牲理解为代价。

在阅读初期,可以先以较慢的速度保证理解的准确性,随着阅读能力的提高,逐渐加快阅读速度。

为了提高阅读速度,可以采用一些方法。

比如,扩大视距,不要一个单词一个单词地读,而是尽量一次看多个单词;避免回读,养成一次性读懂的习惯;根据文章的体裁和内容,有选择性地阅读,对于不重要的细节可以快速浏览。

四、阅读策略1、预读在开始阅读一篇文章之前,先快速浏览标题、副标题、引言、段落首句、图表等,了解文章的大致内容和结构,明确主题和重点,这样在阅读正文时就能更有针对性。

高中生必看的英文原著摘要:1.适合高中生阅读的英文原著推荐2.推荐原因和阅读建议3.如何选择适合自己的英文原著4.阅读英文原著的注意事项正文:高中生必看的英文原著对于高中生来说,阅读英文原著是提高英语水平和开阔眼界的好方法。

但是,面对众多英文原著,如何选择适合自己的书籍呢?本文将为您推荐几本适合高中生阅读的英文原著,并提供一些阅读建议和选择方法。

一、适合高中生阅读的英文原著推荐1.《哈利·波特》系列(Harry Potter):这是一部脍炙人口的奇幻小说,讲述了一个神奇世界中的少年成长故事。

词汇量适中,情节引人入胜,适合高中生阅读。

2.《傲慢与偏见》(Pride and Prejudice):简·奥斯汀的代表作,讲述了19 世纪英国家庭生活中的爱情故事。

此书语言优美,适合喜欢文学作品的高中生阅读。

3.《了不起的盖茨比》(The Great Gatsby):美国作家菲茨杰拉德的代表作,讲述了上世纪20 年代美国社会的道德沦丧和财富追逐。

此书语言较为简单,但主题深刻,适合高中生阅读。

二、推荐原因和阅读建议1.语言难度适中:以上推荐的英文原著在词汇和语法上都有较好的控制,不至于让高中生感到无法理解。

2.主题内容丰富:这些书籍涵盖了成长、爱情、社会等多个方面,有助于高中生拓宽视野、提高思考能力。

3.激发阅读兴趣:这些书籍的故事情节引人入胜,让读者在阅读过程中感受到乐趣,从而提高英语学习积极性。

阅读建议:1.选择适合自己的书籍:根据个人兴趣和英语水平,挑选一本适合自己的英文原著进行阅读。

2.逐步提高阅读难度:从简单的英文原著开始,逐渐尝试阅读更复杂的书籍,以提高自己的英语水平。

3.多做笔记、查阅词典:在阅读过程中,遇到不懂的词汇和表达,要及时查阅词典并记录下来,以便日后复习。

三、如何选择适合自己的英文原著1.了解自己的英语水平:选择英文原著时,要清楚自己的英语水平,选择难度适中的书籍。

如何练习提高英语阅读能力提高英语阅读能力是一个循序渐进的过程,它需要耐心、持续的努力和正确的方法。

以下是一些有效的策略,可以帮助你提升英语阅读技能。

1. 阅读多样化的材料- 阅读不同类型的文本,如小说、报纸、杂志、学术论文和在线文章,可以帮助你接触到不同的词汇和语法结构。

2. 定期阅读- 每天安排一定的时间来阅读,哪怕只有15分钟,也能帮助你的阅读技能稳步提高。

3. 学习新词汇- 遇到生词时,查阅字典并尝试在句子中使用它们,这有助于扩大你的词汇量。

4. 理解上下文- 理解单词在不同上下文中的含义,而不仅仅是它们的基本意义,这有助于提高你的理解力。

5. 练习速读- 练习快速阅读并抓住文章的主要观点,这有助于提高阅读效率。

6. 阅读时做笔记- 阅读时做笔记可以帮助你更好地理解和记忆文章的内容。

7. 参与讨论- 加入英语阅读小组或在线论坛,与他人讨论你读过的文章,可以提高你的理解力和表达能力。

8. 阅读英文原著- 阅读未经翻译的英文书籍,可以更深入地了解英语文化和语言。

9. 利用技术辅助- 使用电子阅读器、应用程序和在线资源来辅助你的阅读,这些工具通常提供词汇表和翻译功能。

10. 定期复习- 定期复习你读过的内容,这有助于巩固记忆和理解。

11. 阅读时保持好奇心- 对于你感兴趣的主题,深入阅读,这将激发你的学习热情。

12. 挑战自己- 不断挑战自己阅读更复杂或更长的文章,这有助于提高你的阅读水平。

通过这些方法的持续实践,你的英语阅读能力将得到显著提升。

记住,学习是一个过程,享受阅读的乐趣同样重要。

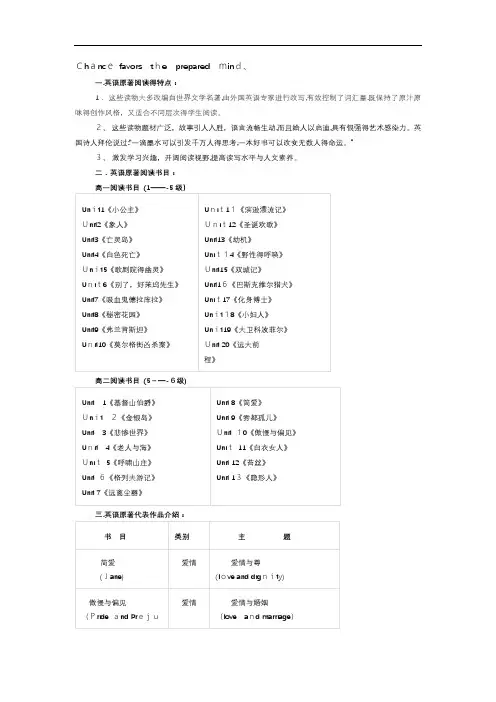

让英文原著阅读活跃在初中生活中摘要:提起英语原著阅读,很多初中学生都望而却步,认为这与自己现有的水平相距甚远,至少这是大学英语专业学生才应该去做的事情。

但是原著阅读在初中真的难以实施吗?针对这一现象,笔者从自己的阅读经历出发,结合多年一线教学的经验,有了以下思考。

关键词:原著阅读;现状;方式《义务教育英语课程标准(2011 年版)》在阅读量方面对学生提出的要求是:三级:除教材外,课外阅读量应累计达4 万词以上;四级:除教材外,课外阅读量应累计达到10 万词以上;五级:除教材外,课外阅读量应累计达到15 万词以上。

《标准(2011 年版)》在情感态度方面,要求中学生能保持学习英语的愿望和兴趣,主动参与有助于提高英语能力的活动,有正确的英语学习动机,明确英语学习的目的是为了沟通和表达,敢于用英语进行交流,在学习中有较强的合作精神,愿意与他人分享各种学习资源。

显然,要达到新课程标准的要求,只靠教科书是远远不能保证足够的语言输入量的。

因此,教师必须设法丰富学生的阅读材料就变得至关重要。

这就要求老师拓展课程资源,拓展英语学习的渠道。

根据一线教学的经验和自己阅读的经历,笔者将中学生面对名著阅读望而却步的原因总结如下:1.单词很难。

名著中的单词有很多是专有名词或者有很强文化色彩的词。

有一些作者喜欢用各种明喻、暗语等写作手法,增强文章的艺术性。

而学生最常见的单词是与生活相关的常用词汇,刚接触名著,会面临强烈的词汇冲击。

2.句式比较复杂。

在名著里,经常会有一个句子就是一个长段落。

句式复杂,各种从句夹杂在一起,找不到主语谓语成份。

有时也会遇到语言口语化,文章中充斥着大量的省略、倒装等。

由于英语和汉语语言思维习惯的差异,学生阅读纯正的英语文章,会有思维的不适感。

3.不了解相关背景知识。

例如在著作里,学生不知道作者提到的那首歌、那个牌子的西烟有什么象征意义。

4.阅读习惯不到位。

遇到不懂的生词,有些学生就会跳过去或者停下来查字典。

ONE BASKET THIRTY-ONE SHORT STORIESEDNA FERBERThe Woman Who Tried to Be Good[1913]Before she tried to be a good woman she had been a very bad woman--so bad that she could trail her wonderful apparel up and down Main Street, from the Elm Tree Bakery to the railroad tracks, without once having a man doff his hat to her or a woman bow. You passed her on the street with a surreptitious glance, though she was well worth looking at-- in her furs and laces and plumes. She had the only full-length mink coat in our town, and Ganz's shoe store sent to Chicago for her shoes. Hers were the miraculously small feet you frequently see in stout women.Usually she walked alone; but on rare occasions, especially round Christmastime, she might have been seen accompanied by some silent, dull-eyed, stupid-looking girl, who would follow her dumbly in and out of stores, stopping now and then to admire a cheap comb or a chain set with flashy imitation stones--or, queerly enough, a doll with yellow hair and blue eyes and very pink cheeks. But, alone or in company, her appearance in the stores of our town was the signal for a sudden jump in the cost of living. The storekeepers mulcted her; and she knew it and paid in silence, for she was of the class that has no redress. She owned the House with the Closed Shutters, near the freight depot--did Blanche Devine.In a larger town than ours she would have passed unnoticed. She did not look like a bad woman. Of course she used too much make-up, and as she passed you caught the oversweet breath of a certain heavy scent. Then, too, her diamond eardrops would have made any woman's features look hard; but her plump face, in spite of its heaviness, wore an expression of good-humored intelligence, and her eyeglasses gave her somehow a look of respectability. We do not associate vice with eyeglasses. So in a large city she would have passed for a well-dressed, prosperous, comfortable wife and mother who was in danger of losing her figure from an overabundance of good living; but with us she was a town character, like Old Man Givins, the drunkard, or the weak-minded Binns girl.When she passed the drug- store corner there would be a sniggering among the vacant-eyed loafers idling there, and they would leer at each other and jest in undertones.So, knowing Blanche Devine as we did, there was something resembling a riot in one of our most respectable neighborhoods when it was learned that she had given up her interest in the house near the freight depot and was going to settle down in the white cottage on the corner and be good. All the husbands in the block, urged on by righteously indignant wives, dropped in on Alderman Mooney after supper to see if the thing could not be stopped. The fourth of the protesting husbands to arrive was the Very Young Husband who lived next door to the corner cottage that Blanche Devine had bought. The Very Young Husband had a Very Young Wife, and they were the joint owners of Snooky. Snooky was three-going- on-four, and looked something like an angel--only healthier and with grimier hands. The whole neighborhood borrowed her and tried to spoil her; but Snooky would not spoil.Alderman Mooney was down in the cellar, fooling with the furnace.He was in his furnace overalls; a short black pipe in his mouth.Three protesting husbands had just left. As the Very Young Husband, following Mrs. Mooney's directions, descended the cellar stairs, Alderman Mooney looked up from his tinkering. He peered through a haze of pipe smoke."Hello!" he called, and waved the haze away with his open palm."Come on down! Been tinkering with this blamed furnace since supper. She don't draw like she ought. 'Long toward spring a furnace always gets balky. How many tons you used this winter?""Oh-five," said the Very Young Husband shortly. Alderman Mooney considered it thoughtfully. The Young Husband leaned up against the side of the water tank, his hands in his pockets. "Say, Mooney, is that right about Blanche Devine's having bought the house on the corner?""You're the fourth man that's been in to ask me that this evening. I'm expecting the rest of the block before bedtime. She bought it all right."The Young Husband flushed and kicked at a piece of coal with the toe of his boot."Well, it's a darned shame!" he began hotly. "Jen was ready to cry at supper. This'll be a fine neighborhood for Snooky to grow up in! What's a woman like that want to come into a respectable street for, anyway? I own my home and pay my taxes--"Alderman Mooney looked up."So does she," he interrupted. "She's going to improve the place-- paint it, and put in a cellar and a furnace, and build a porch, and lay a cement walk all round."The Young Husband took his hands out of his pockets in order to emphasize his remarks with gestures."Whati's that got to do with it? I don't care if she puts in diamonds for windows and sets out Italian gardens and a terrace with peacocks on it. You're the alderman of this ward, aren't you? Well, it was up to you to keep her out of this block! You could have fixed it with an injunction or somethng. I'm going to get up a petition--that's what I'm going "Alderman Mooney closed the furnace door with a bang that drowned the rest of the threat. He turned the draft in a pipe overhead and brushed his sooty palms briskly together like one who would put an end to a profitless conversation."She's bought the house," he said mildly, "and paid for it. And it's hers. She's got a right to live in this neighborhood as long as she acts respectable."The Very Young Husband laughed."She won't last! They never do."Alderman Mooney had taken his pipe out of his mouth and was rubbing his thumb over the smooth bowl, looking down at it with unseeing eyes. On his face was a queer look--the look of one who is embarrassed because he is about to say something honest."Look here! I want to tell you something: I happened to be up in the mayor's office the day Blanche signed for the place. She had to go through a lot of red tape before she got it--had quite a time of it, she did! And say, kid, that woman ain't so--bad."The Very Young Husband exclaimed impatiently:"Oh, don't give me any of that, Mooney! Blanche Devine's a towncharacter. Even the kids know what she is. If she's got religion or something, and wants to quit and be decent, why doesn't she go to another town-- Chicago or someplace--where nobody knows her?"That motion of Alderman Mooney's thumb against the smooth pipe bowl stopped. He looked up slowly."That's what I said--the mayor too. But Blanche Devine said she wanted to try it here. She said this was home to her. Funny--ain't it? Said she wouldn't be fooling anybody here. They know her. And if she moved away, she said, it'd leak out some way sooner or later. It does, she said. Always! Seems she wants to live like--well, like other women. She put it like this: she says she hasn't got religion, or any of that. She says she's no different than she was when she was twenty. She says that for the last ten years the ambition of her life has been to be able to go into a grocery store and ask the price of, say, celery; and, if the clerk charged her ten when it ought to be seven, to be able to sass him with a regular piece of her mind-- and then sail out and trade somewhere else until he saw that she didn't have to stand anything from storekeepers, any more than any other woman that did her own marketing. She's a smart woman, Blanche is! God knows I ain't taking her part--exactly; but she talked a little, and the mayor and me got a little of her history."A sneer appeared on the face of the Very Young Husband. He had been known before he met Jen as a rather industrious sower of wild oats. He knew a thing or two, did the Very Young Husband, in spite of his youth! He always fussed when Jen wore even a V-necked summer gown on the street."Oh, she wasn't playing for sympathy," went on Alderman Mooney in answer to the sneer. "She said she'd always paid her way and always expected to. Seems her husband left her without a cent when she was eighteen--with a baby. She worked for four dollars a week in a cheap eating house. The two of 'em couldn't live on that. Then the baby ""Good night!" said the Very Young Husband. "I suppose Mrs. Mooney's going to call?""Minnie! It was her scolding all through supper that drove me down to monkey with the furnace. She's wild--Minnie is." He peeled off hisoveralls and hung them on a nail. The Young Husband started to ascend the cellar stairs. Alderman Mooney laid a detaining finger on his sleeve. "Don't say anything in front of Minnie! She's boiling! Minnie and the kids are going to visit her folks out West this summer; so I wouldn't so much as dare to say `Good morning!' to the Devine woman. Anyway, a person wouldn't talk to her, I suppose. But I kind of thought I'd tell you about her."Thanks!" said the Very Young Husband dryly.In the early spring, before Blanche Devine moved in, there came stone- masons, who began to build something. It was a great stone fireplace that rose in massive incongruity at the side of the little white cottage. Blanche Devine was trying to make a home for herself.Blanche Devine used to come and watch them now and then as the work progressed. She had a way of walking round and round the house, looking up at it and poking at plaster and paint with her umbrella or finger tip. One day she brought with her a man with a spade. He spaded up a neat square of ground at the side of the cottage and a long ridge near the fence that separated her yard from that of the Very Young Couple next door. The ridge spelled sweet peas and nasturtiums to our small-town eyes.On the day that Blanche Devine moved in there was wild agitation among the white-ruffed bedroom curtains of the neighborhood. Later on certain odors, as of burning dinners, pervaded the atmosphere. Blanche Devine, flushed and excited, her hair slightly askew, her diamond eardrops flashing, directed the moving, wrapped in her great fur coat; but on the third morning we gasped when she appeared out-of-doors, carrying a little household ladder, a pail of steaming water, and sundry voluminous white cloths. She reared the little ladder against the side of the house, mounted it cautiously, and began to wash windows with housewifely thoroughness. Her stout figure was swathed in a gray sweater and on her head was a battered felt hat--the sort of window--washing costume that has been worn by women from time immemorial. We noticed that she used plenty of hot water and clean rags, and that she rubbed the glass until it sparkled, leaning perilously sideways on the ladder to detect elusive streaks. Ourkeenest housekeeping eye could find no fault with the way Blanche Devine washed windows.By May, Blanche Devine had left off her diamond eardrops--perhaps it was their absence that gave her face a new expression. When she went downtown we noticed that her hats were more like the hats the other women in our town wore; but she still affected extravagant footgear, as is right and proper for a stout woman who has cause to be vain of her feet. We noticed that her trips downtown were rare that spring and summer. She used to come home laden with little bundles; and before supper she would change her street clothes for a neat, washable housedress, as is our thrifty custom. Through her bright windows we could see her moving briskly about from kitchen to sitting room; and from the smells that floated out from her kitchen door, she seemed to be preparing for her solitary supper the same homely viands that were frying or stewing or baking in our kitchens. Sometimes you could detect the delectable scent of browning, hot tea biscuit. It takes a determined woman to make tea biscuit for no one but herself.Blanche Devine joined the church. On the first Sunday morning she came to the service there was a little flurry among the ushers at the vestibule door. They seated her well in the rear. The second Sunday morning a dreadful thing happened. The woman next to whom they seated her turned, regarded her stonily for a moment, then rose agitatedly and moved to a pew across the aisle.Blanche Devine's face went a dull red beneath her white powder. She never came again--though we saw the minister visit her once or twice. She always accompanied him to the door pleasantly, holding it well open until he was down the little flight of steps and on the sidewalk. The minister's wife did not call.She rose early, like the rest of us; and as summer came on we used to see her moving about in her little garden patch in the dewy, golden morning. She wore absurd pale-blue negligees that made her stout figure loom immense against the greenery of garden and apple tree. The neighborhood women viewed these negligees with Puritan disapproval as they smoothed down their own prim, starched gingham skirts. They saidit was disgusting --and perhaps it was; but the habit of years is not easily overcome. Blanche Devine--snipping her sweet peas, peering anxiously at the Virginia creeper that clung with such fragile fingers to the trellis, watering the flower baskets that hung from her porch--was blissfully unconscious of the disapproving eyes. I wish one of us had just stopped to call good morning to her over the fence, and to say in our neighborly, small-town way: "My, ain't this a scorcher! So early too! It'll be fierce by noon!"But we did not.I think perhaps the evenings must have been the loneliest for her. The summer evenings in our little town are filled with intimate, human, neighborly sounds. After the heat of the day it is pleasant to relax in the cool comfort of the front porch, with the life of the town eddying about us. We sew and read out there until it grows dusk. We call across lots to our next- door neighbor. The men water the lawns and the flower boxes and get together in little, quiet groups to discuss the new street paving. I have even known Mrs. Hines to bring her cherries out there when she had canning to do, and pit them there on the front porch partially shielded by her porch vine, but not so effectually that she was deprived of the sights and sounds about her. The kettle in her lap and the dishpan full of great ripe cherries on the porch floor by her chair, she would pit and chat and peer out through the vines, the red juice staining her plump bare arms.I have wondered since what Blanche Devine thought of us those lonesome evenings--those evenings filled with friendly sights and sounds. It must have been difficult for her, who had dwelt behind closed shutters so long, to seat herself on the new front porch for all the world to stare at; but she did sit there--resolutely--watching us in silence.She seized hungrily upon the stray crumbs of conversation that fell to her. The milkman and the iceman and the butcher boy used to hold daily conversation with her. They--sociable gentlemen--would stand on her door- step, one grimy hand resting against the white of her doorpost, exchanging the time of day with Blanche in the doorway--a tea towel in one hand, perhaps, and a plate in the other. Her little house was a miracle of cleanliness. It was no uncommon sight to see her down on her kneeson the kitchen floor, wielding her brush and rag like the rest of us. In canning and preserving time there floated out from her kitchen the pungent scent of pickled crab apples; the mouth-watering smell that meant sweet pickles; or the cloying, divinely sticky odor that meant raspberry jam. Snooky, from her side of the fence, often used to peer through the pickets, gazing in the direction of the enticing smells next door.Early one September morning there floated out from Blanche Devine's kitchen that fragrant, sweet scent of fresh-baked cookies--cookies with butter in them, and spice, and with nuts on top. Just by the smell of them your mind's eye pictured them coming from the oven-crisp brown circlets, crumbly, delectable. Snooky, in her scarlet sweater and cap, sniffed them from afar and straightway deserted her sand pile to take her stand at the fence. She peered through the restraining bars, standing on tiptoe. Blanche Devine, glancing up from her board and rolling pin, saw the eager golden head. And Snooky, with guile in her heart, raised one fat, dimpled hand above the fence and waved it friendlily. Blanche Devine waved back. Thus encouraged, Snooky's two hands wigwagged frantically above the pickets. Blanche Devine hesitated a moment, her floury hand on her hip. Then she went to the pantry shelf and took out a clean white saucer. She selected from the brown jar on the table three of the brownest, crumbliest, most perfect cookies, with a walnut meat perched atop of each, placed them temptingly on the saucer and, descending the steps, came swiftly across the grass to the triumphant Snooky. Blanche Devine held out the saucer, her lips smiling, her eyes tender. Snooky reached up with one plump white arm."Snooky!" shrilled a high voice. "Snooky!" A voice of horror and of wrath. "Come here to me this minute! And don't you dare to touch those!" Snooky hesitated rebelliously, one pink finger in her pouting mouth."Snooky! Do you hear me?"And the Very Young Wife began to descend the steps of her back porch. Snooky, regretful eyes on the toothsome dainties, turned away aggrieved. The Very Young Wife, her lips set, her eyes flashing, advanced and seized the shrieking Snooky by one arm and dragged her away toward home andsafety.Blanche Devine stood there at the fence, holding the saucer in her hand. The saucer tipped slowly, and the three cookies slipped off and fell to the grass. Blanche Devine stood staring at them a moment. Then she turned quickly, went into the house, and shut the door.It was about this time we noticed that Blanche Devine was away much of the time. The little white cottage would be empty for weeks. We knew she was out of town because the expressman would come for her trunk. We used to lift our eyebrows significantly. The newspapers and handbills would accumulate in a dusty little heap on the porch; but when she returned there was always a grand cleaning, with the windows open, and Blanche--her head bound turbanwise in a towel--appearing at a window every few minutes to shake out a dustcloth. She seemed to put an enormous amount of energy into those cleanings--as if they were a sort of safety valve.As winter came on she used to sit up before her grate fire long, long after we were asleep in our beds. When she neglected to pull down the shades we could see the flames of her cosy fire dancing gnomelike on the wall. There came a night of sleet and snow, and wind and rattling hail-- one of those blustering, wild nights that are followed by morning-paper reports of trains stalled in drifts, mail delayed, telephone and telegraph wires down. It must have been midnight or past when there came a hammering at Blanche Devine's door--a persistent, clamorous rapping. Blanche Devine, sitting before her dying fire half asleep, started and cringed when she heard it, then jumped to her feet, her hand at her breast-- her eyes darting this way and that, as though seeking escape.She had heard a rapping like that before. It had meant bluecoats swarming up the stairway, and frightened cries and pleadings, and wild confusion. So she started forward now, quivering. And then she remembered, being wholly awake now--she remembered, and threw up her head and smiled a little bitterly and walked toward the door. The hammering continued, louder than ever. Blanche Devine flicked on the porch light and opened the door. The half-clad figure of the Very Young Wife next door staggered into the room. She seized Blanche Devine'sarm with both her frenzied hands and shook her, the wind and snow beating in upon both of them."The baby!" she screamed in a high, hysterical voice. "The baby!The baby !"Blanche Devine shut the door and shook the Young Wife smartly by the shoulders."Stop screaming," she said quietly. "Is she sick?"The Young Wife told her, her teeth chattering:"Come quick! She's dying! Will's out of town. I tried to get the doctor. The telephone wouldn't---- I saw your light! For God's sake "Blanche Devine grasped the Young Wife's arm, opened the door, and together they sped across the little space that separated the two houses. Blanche Devine was a big woman, but she took the stairs like a girl and found the right bedroom by some miraculous woman instinct. A dreadful choking, rattling sound was coming from Snooky's bed."Croup," said Blanche Devine, and began her fight.It was a good fight. She marshaled her inadequate forces, made up of the half-fainting Young Wife and the terrified and awkward hired girl."Get the hot water on--lots of it!" Blanche Devine pinned up her sleeves. "Hot cloths! Tear up a sheet--or anything! Got an oilstove? I want a tea- kettle boiling in the room. She's got to have the steam. If that don't do it we'll raise an umbrella over her and throw a sheet over, and hold the kettle under till the steam gets to her that way. Got any ipecac?"The Young Wife obeyed orders, white-faced and shaking. Once Blanche Devine glanced up at her sharply."Don't you dare faint!" she commanded.And the fight went on. Gradually the breathing that had been so frightful became softer, easier. Blanche Devine did not relax. It was not until the little figure breathed gently in sleep that Blanche Devine sat back, satisfied. Then she tucked a cover at the side of the bed, took a last satisfied look at the face on the pillow, and turned to look at the wan, disheveled Young Wife."She's all right now. We can get the doctor when morning comes-- though I don't know's you'll need him."The Young Wife came round to Blanche Devine's side of the bed and stood looking up at her."My baby died," said Blanche Devine simply. The Young Wife gave a little inarticulate cry, put her two hands on Blanche Devine's broad shoulders, and laid her tired head on her breast."I guess I'd better be going," said Blanche Devine.The Young Wife raised her head. Her eyes were round with fright."Going! Oh, please stay! I'm so afraid. Suppose she should takesick again! That awful--breathing ""I'll stay if you want me to.""Oh, please! I'll make up your bed and you can rest ""I'm not sleepy. I'm not much of a hand to sleep anyway. I'll sit up here in the hall, where there's a light. You get to bed. I'll watch and see that everything's all right. Have you got something I can read out here-- something kind of lively--with a love story in it?"So the night went by. Snooky slept in her white bed. The Very Young Wife half dozed in her bed, so near the little one. In the hall, her stout figure looming grotesque in wall shadows, sat Blanche Devine, pretending to read. Now and then she rose and tiptoed into the bedroom with miraculous quiet, and stooped over the little bed and listened and looked--and tiptoed away again, satisfied.The Young Husband came home from his business trip next day with tales of snowdrifts and stalled engines. Blanche Devine breathed a sigh of relief when she saw him from her kitchen window. She watched the house now with a sort of proprietary eye. She wondered about Snooky; but she knew better than to ask. So she waited. The Young Wife next door had told her husband all about that awful night--had told him with tears and sobs. The Very Young Husband had been very, very angry with her-- angry, he said, and astonished! Snooky could not have been so sick! Look at her now! As well as ever. And to have called such a woman! Well, he did not want to be harsh; but she must understand that she must never speak to the woman again. Never!So the next day the Very Young Wife happened to go by with the Young Husband. Blanche Devine spied them from her sitting-roomwindow, and she made the excuse of looking in her mailbox in order to go to the door. She stood in the doorway and the Very Young Wife went by on the arm of her husband. She went by--rather white-faced--without a look or a word or a sign!And then this happened! There came into Blanche Devine's face a look that made slits of her eyes, and drew her mouth down into an ugly, narrow line, and that made the muscles of her jaw tense and hard. It was the ugliest look you can imagine. Then she smiled--if having one's lips curl away from one's teeth can be called smiling.Two days later there was great news of the white cottage on the corner. The curtains were down; the furniture was packed; the rugs were rolled. The wagons came and backed up to the house and took those things that had made a home for Blanche Devine. And when we heard that she had bought back her interest in the House with the Closed Shutters, near the freight depot, we sniffed."I knew she wouldn't last!" we said."They never do!" said we.The Gay Old Dog [1917]Those of you who have dwelt--or even lingered--in Chicago, Illinois, are familiar with the region known as the Loop. For those others of you to whom Chicago is a transfer point between New York and California there is presented this brief explanation:The Loop is a clamorous, smoke-infested district embraced by the iron arms of the elevated tracks. In a city boasting fewer millions, it would be known familiarly as downtown. From Congress to Lake Street, from Wabash almost to the river, those thunderous tracks make a complete circle, or loop. Within it lie the retail shops, the commercial hotels, the theaters, the restaurants. It is the Fifth Avenue and the Broadway of Chicago.And he who frequents it by night in search of amusement and cheer is known, vulgarly, as a Loop-hound.Jo Hertz was a Loop-hound. On the occasion of those sparse first nights granted the metropolis of the Middle West he was always present, third row, aisle, left. When a new Loop cafe' was opened, Jo's table always commanded an unobstructed view of anything worth viewing. On entering he was wont to say, "Hello, Gus," with careless cordiality to the headwaiter, the while his eye roved expertly from table to table as he removed his gloves. He ordered things under glass, so that his table, at midnight or thereabouts, resembled a hotbed that favors the bell system. The waiters fought for him. He was the kind of man who mixes his own salad dressing. He liked to call for a bowl, some cracked ice, lemon, garlic, paprika, salt, pepper, vinegar, and oil and make a rite of it. People at near-by tables would lay down their knives and forks to watch, fascinated. The secret of it seemed to lie in using all the oil in sight and calling for more.That was Jo--a plump and lonely bachelor of fifty. A plethoric, roving- eyed, and kindly man, clutching vainly at the garments of a youth that had long slipped past him. Jo Hertz, in one of those pinch-waist suits and a belted coat and a little green hat, walking up Michigan Avenue of a bright winter's afternoon, trying to take the curb with a jaunty。

《老人与海》英语原著阅读(一)Day 1He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish. In the first forty days a boy had been with him.But after forty days without a fish the boy's parents had told him that the old man was now definitely and finally salao, which is the worst form of unlucky, and the boy had gone at their orders in another boat which caught three good fish the first week.It made the boy sad to see the old man come in each day with his skiff empty and he always went down to help him carry either the coiled lines or the gaff and harpoon and the sail that was furled around the mast. The sail was patched with flour sacks and, furled, it looked like the flag of permanent defeat.The old man was thin and gaunt with deep wrinkles in the back of his neck. The brown blotches of the benevolent skin cancer the sun brings from its reflection on the tropic sea were on his cheeks.The blotches ran well down the sides of his face and his hands had the deep-creased scars from handling heavy fish on the cords. But none of these scars were fresh. They were as old as erosions in a fishless desert.Everything about him was old except his eyes and they were the same color as the sea and were cheerful and undefeated."Santiago," the boy said to him as they climbed from the bank where the skiff was hauled up. "I could go with you again. We've made some money."The old man had taught the boy to fish and the boy loved him."No," the old man said. "You're with a lucky boat. Stay with them.""But remember how you went eighty-seven days without fish and then we caught big ones every day for three weeks.""I remember," the old man said. "I know you did not leave me because you doubted.""It was papa made me leave. I am a boy and I must obey him.""I know," the old man said. "It is quite normal.""He hasn't much faith.""No," the old man said. "But we have. Haven't we?""Yes," the boy said. "Can I offer you a beer on the Terrace and then we'll take the stuff home.""Why not?" the old man said. "Between fishermen."They sat on the Terrace and many of the fishermen made fun of the old man and he was not angry. Others, of the older fishermen, looked at him and were sad. But they did not show it and they spoke politely about the current and the depths they had drifted their lines at and the steady good weather and of what they had seen.The successful fishermen of that day were already in and had butchered their marlin out and carried them laid full length across two planks, with two men staggering at the end of each plank, to the fish house where they waited for the ice truck to carry them to the market in Havana.Those who had caught sharks had taken them to the shark factory on the other side of the cove where they were hoisted on a block and tackle, their livers removed, their fins cut off and their hides skinned out and their flesh cut into strips for salting. 1harpoon /hɑ:ˈpu:n/ GREn.鱼镖,鱼叉例:The harpoon drove deep into [into表示进入的意思】the body of the whale.2permanent /ˈpɜ:mənənt/ IELTS/TOEFL/GRE/4/6/考研adj.永久(性)的,永恒的,不变的,耐久的,持久的,经久的;稳定的;常务的,常设的例:The museum will have a permanent exhibition of 60 vintage cars.3benevolent /bəˈnevələnt/ GREadj.好心肠的;与人为善的;乐善好施的;慈善的例:They believe that the country needs a benevolent dictator.4haul /hɔ:l/ IELTS/TOEFL/6/考研vt.& vi.拖,拉例:Revitalising the Romanian economy will be a long haul.5hoist /hɔɪst/ IELTS/GRE/6/考研vt.升起,提起例:Materials are elevated to the top floor by the new hoist.6skiff /skɪf/ GREn.小艇,小型帆船;摩托小快艇例:Huck, I'll take you right to it in a skiff.7gaunt /gɔ:nt/ IELTS/GREadj.憔悴的;骨瘦如柴的;荒凉的例:Above on the hillside was a large, gaunt, grey house.8sturdy /ˈstɜ:di/ IELTS/TOEFL/GRE/6/考研adj.强壮的,健全的;坚固的,耐用的;坚定的;精力充沛的例:Grease two sturdy baking sheets and heat the oven to 400 degrees.9stuff /stʌf/ IELTS/4/6/考研n.材料,原料,资料;〈俚〉钱,现金;填充物;素材资料例:I don't want any more of that heavy stuff.10marlin /ˈmɑ:lɪn/n.枪鱼,青枪鱼,四鳃旗鱼例:It could have been a marlin or a broadbill or a shark.01重点单词/词组harpoon【释】n. a spear with a shaft and barbed point for throwing【译】鱼叉【同】leisterpermanent【释】adj.continuing or enduring without marked change in status or condition or place【译】永久的【延】n.permanence【同】lastingbenevolent【释】adj.intending or showing kindness【译】仁慈的【延】benevolence【同】friendlyhaul【释】v.draw slowly or heavily【译】托拉【搭】haul uphoist【释】v.move from one place to another by lifting【译】吊起【延】n.hoister 起重机【同】lifthoist 和lift的区别:◈hoist 多指用绳索、滑轮等机械把重物升起。

读原著,学英语(初级篇)小说原著要怎么读才能学到英语呢?以下就根据笔者个人的学习经验,给初入门的学习者提供几点建议:挑选作品1.浪漫喜剧小说这类小说一般是写给青年人看的,语言通俗浅显,风格轻松活泼,题材软性轻松,每每受到读者喜爱;这类讨论男女关系、家庭生活的小说,时空背景又多设定于现代,书中人物的生活不至于与现实脱节太大,观众很容易就能产生共鸣。

此外,有些对白场景与日常生活情境相关,值得学习者留意,比方说上餐馆点菜或与人辩论等等;甚至,透过故事还能了解英美等国的风土文化,比如说婚礼或节庆的习俗。

2. 其他主题除了上述类型的小说之外,一般故事的主题包罗万象,小自人生哲理,大至国家要事,同样可以拿来当作学习的教材,进一步训练批判性思考或口语简报讨论的能力。

不过,其情节通常要比浪漫喜剧来的多,而且情节较为复杂,探讨的主题若是扯上国家社会问题,也会显得较为严肃,学习者可要有点耐性。

由于各个作家的写作风格不同,文笔也不一,文字难度上会有很大的差异;即使是同一作家,不同作品也会风格迥异。

因此,初学者在挑选上要特别谨慎,否则会挫伤积极性。

一般来说,可以选一些已有中译本的小说,这并不是要鼓励大家完全依赖中文,而是有实在搞不懂的地方,可以参考一下译文。

其次,小说中涉及的主题不应过于专业或文化底蕴不要太丰富,像迈克尔·克莱顿的作品由于涉及很多高科技,很多魔幻小说引用神话故事,这些并不适合初学者。

第三,根据我个人的读书经验来看,小说每页的生词不宜超过3-5%(涉及的地名、人名、产品名等一般不影响阅读,故不算在内),否则就PASS。

3.阅读适合自己水平的作品根据上面的阐述,古典作品难读现代作品易读这样的思想观念是不正确的。

无论古典还是现代,言情还是神话,阅读的驱动力主要还是兴趣和成就感。

前者依赖于个人的口味,而后者则与小说的正确选择有很大的关系。

因为要保证良好的阅读效果,不同级别的英语学习者就需要阅读与自己水平相适应的文学作品。

太难和太易都不能激发学习的动感。

那么应该如何判断自己的水平和小说的水平是否一致呢?最简单的方法就是在不翻阅字典的情况下尝试阅读第一章,然后对照中译本检查自己理解的程度,70%-80%以上既可以说水平合适。

如果没有中译本,也可以把看开头几段,把生词查完后对照查之前的理解程度来判断。

有人也提出了以生词量的多少作为选择的标准,3%-5%的生词量是一般要求。

然而有的作品即使有大量的词汇不认识也不会影响阅读(这类词汇主要包括专业领域的名词和部分形容词,还有少部分可以猜测意思的动词和动词短语),另外一些作品则正好相反。

所以还是主张以理解程度来判断。

平时阅读时只有多多尝试不要轻易放弃,就不会错过一些表面上很难但实际上能读懂的小说。

我个人读过的较容易的作品是西德尼·谢尔顿(Sydney Sheldon)的《天幕降临》(The Sky Is Falling),Dave Berry的Big Trouble,John Grisham的The Brethren。

心态和工具的准备别以为把一部小说重复看十次,英语就能进步,你要懂得方法,重点学习,学什么呢?学作者的遣词用字,想想他们为什么这么说,看看他们如何将语言灵活运用于情境之中,如果可以的话,最好还要学学他们展现在语言上的幽默和思维逻辑,这一点最为困难,即使是苦读英语十年的人也不一定学得来。

照这么说来,利用小说学英语其实工程浩大,无法一蹴而就,这种自我学习是重质不重量,只要功夫下的扎实,就算你每次只花十五分钟或半小时来读一小片段,一年只读一两本小说也绰绰有余了。

(画外音:好啦,别罗嗦啦!举个例子嘛!)先不急,我先讲讲读原著时的常用装备:1. 笔记本(是笔记的本子,也可以是电脑啦)或者小卡片N张,主要用来记录生词、词组、好句子,总结归纳同义表达、近反义词,记录难点。

2. 英汉双解词典一部(或者在线词典),要勤翻词典。

阅读时的心态也很重要,除了不要急功近利以外,还有一些要注意的:刚开始阅读的阶段也是最容易放弃的阶段,因为从新闻英语考试英语转换到阅读小说所改变的不仅仅是阅读的形式,而且是整个英语体系的改变――小说的整个遣词造句都与平时新闻考试里遇到的文章有很大的差别。

所以这样的心理准备一定要做好:刚开始不会很容易的。

尤其是前两个月的阅读,主要目的是用来调整个语言体系和记忆新的词汇短语。

绝大多数英语小说的阅读者都会遇到这个阶段,克服的方法也只有一个就是持续不断的阅读和记忆。

只有在掌握了基本的小说词汇之后,欣赏才有可能。

阅读技巧和方法如何避免复杂的句子和生词影响到阅读的进程?1.首先养成良好的阅读习惯。

2.学会猜测词语的含义。

a 大写的词语一般是专属的名词,可以表示特定的机构和人物,也可以表示现实地区名、河流、山脉某一类特殊的群体以及作者文章中虚构出来的地方和人物。

b 有些动词可以根据主语和宾语猜测出来。

还有一些名词,如各种不同的生物,和医学物理学器具,是不需要知道中文的意思的,比如:bonito的意思是鲣,鱼类的一种,但是鲣到底是什么就是中文里也不知道;还有希腊的许多小神祗的名称,也是一样。

只要能根据上下文的意思确定不认识的名词属于某个专业的范围,就连字典都不用查。

读得多了见得多了自然而然就记住了。

就像汉语里的专业词汇一样,有许多我们也看不懂;只是熟悉了就不在乎了。

c 形容词和动词词组。

个人感觉这两个是英文小说阅读里最难的。

除了多读多查多记,没有其他方法。

3.阅读速度。

如果刚开始阅读第一本小说,速度一定不快。

但是应该强迫自己把速度提高上去。

因为据心理学研究表明,高速度阅读不但有利于提高阅读的理解能力,还能在一定程度上改善阅读疲乏的症状;可以保证更长时间的持续阅读。

那么如何提高阅读速度?第一是不要一遇到生词就查词典,第二适当掠过不影响剧情的生词,第三,参考专门的速读教程。

阅读时该留意哪些字词句呢?1.留意小词的灵活用法英语中象come,go等一类的小词用法特别灵活,一个词能表达好多意思。

我们平时搜肠刮肚想了半天才找到个词表达的意思,一个小词往往就可以解决。

比如,要表达“他在我们公司说了算”,我们可以轻松地说‘In our company, what he says goes’。

类似的例子还有The deal is off, I'm right on it, It's been two hours into the movie.2.留意已学过的词的新用法不要以为你学过某个单词就没事啦。

阅读小说时,你会经常发现明明是已学过的单词,可意思怎么也对不上号。

比如He was lifted high up in the air, legs whisking desperately as if they were trying to gain a purchase. 这里的purchase 似乎怎么也跟购买扯不上关系,但从小学到大学,似乎也没哪位老师提过purchase还有别的意思。

其实,这里是指A position, as of a lever or one's feet, affording means to move or secure a weight. 支撑的位置:如杠杆上的位置或某人的双脚等用于移动或支撑重量的位置。

3. 词组和习语见一个记一个4. 留意好句子从学英语的角度说,好句子大致可分几种情况:a.生活化口语(I heard a lot about you 久仰大名)b.评论性话语(可以拿来套用在你的议论文写作上,比如Michael Crichton的侏罗纪公园的引子里有大量评论现代科技发展的文字,非常值得借鉴)c.一些中文耳熟能详的句子但地道英文不知咋说(数量有限,欲购从速limited availability, order soon)d.一些中文耳熟能详的句子、地道英文也知道咋说,可小说中又有别的或补充表达(魔戒中表达良药苦口,忠言逆耳是并未用我们熟知的good medicine tastes bitter,good advice is harsh to the ear,而是用了Faithful heart may have forward tongue)。

e.感动你的文(比如竞选演说)5.留意文中的描写片段我们中国学生最不会写的当是用英语描写人物、场景。

学会一些常见的场景描述对写作绝对有好处。

例如,在自传体小说Sounds of the River里,作者在登上火车进入车厢时,对车厢内那种气味,人群混杂作了一段精彩的描述。

这种场景相信大家挤火车时都见过,但用英文恐怕还不是那么好说的。

再比如,雨水拍打在窗户上,然后蜿蜒流下的场景大家都知道吧,但英文该怎么讲呢?我在一篇小说里就看到过这段文字 A light rain pattered tiny wet fingers on the windows and water beaded and ran down in meandering rivulets.注意总结归纳阅读不是被动吸收的过程,而是主动参与。

不论你在阅读中学到什么,都不要学一个记一个,学两个,记一双。

要善于对所学东西进行归类,发现规律,这样会大大提高学习效率。

就单词而言,因为词汇在人脑中是以激活扩散的方式提取的,就象往河里扔石子,会产生涟漪一样,遇见一个单词,你往往还会激活其他相关的单词。

我们要善于把学到的生词建立成网络状,要由一个词联想到其他词。

这种联想可以是近反义词,也可以是某个特定的场合下的其他单词(比如你最喜爱的电影片段)。

比如alien一词,你可以一下子联想到著名的电影《异形》,同时表达外星人的还有E.T.(extraterrestrial), 既然alien指异于其他,自然还可以指外国的,不同的,象医学上的“异物”可以说alien object。

再例如围绕打电话我们可以总结一些常用语,有初高中就教的Can I take a message? I will put you through on the office line. 还有课本内没有的Could you please put Mr. Smith on? (你能叫Smith先生听电话吗?)。