Running Head THIN SLICES OF NEGOTIATION Thin slices of negotiation Thin Slices of Negotiati

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:228.45 KB

- 文档页数:24

Divergent V ocabularyPage oneslide panel: line 1 , [slaɪd]['pæn(ə)l]A panel can slide over something like a mirror.滑动面板If you slide somewhere, you move there smoothly and quietly. 滑动A panel is a flat rectangular piece of wood or other material 平板stool: line 5 [stuːl]A stool is a seat with legs but no support for your arms or back 凳子3 trim: line 6[trɪm]If you trim something, for example, someone's hair, you cut off small amounts of it in order to make it look neater. 修剪4 strand: line 6 [strænd]A strand of something such as hair, wire, or thread is a single thin piece of it. (头发、电线或纱线的) 缕twist : line 9 [twɪst]If you twist something, you turn it to make a spiral shape, for example, by turning the two ends of it in opposite directions. 扭曲; 拧6. knot: line 9[nɔt]If you tie a knot in a piece of string, rope, cloth, or other material, you pass one end or part of it through a loop and pull it tight. 结7. sneak : line 12 [sniːk]If you sneak a look at someone or something, you secretly have a quick look at them. 偷偷地看8.sake: line 13 [seɪk]If you do something for the sake of something, you do it for that purpose or in order to achieve that result. You can also say that you do it for something's sake. 为了…的目的vanity: line 13 /ˈvænɪtɪ/If you refer to someone's vanity, you are critical of them because they take great pride in their appearance or abilities. 虚荣Page 2self-indulgent: line 5['selfin'dʌldʒənt]If you say that someone is self-indulgent, you mean that they allow themselves to have or do the things that they enjoy very much. 自我放纵的reprimand: line 9['reprɪmɑːnd]If someone is reprimanded, they are spoken to angrily or seriously for doing something wrong, usually by a person in authority. 训斥; 谴责[正式]3. aptitude:line 15 ['æptɪtjuːd]Someone's aptitude for a particular kind of work or activity is their ability to learn it quickly and to do it well. 天资eyelash: line 25['aɪlæʃ]Your eyelashes are the hairs that grow on the edges of your eyelids. 睫毛Page 31.abnegation:line 1 [æbnɪ'geɪʃ(ə)n]rejection, refusal拒绝;放弃;克制无私2 skim:line 4[skɪm]If something skims a surface, it moves quickly along just above it. 掠过3 hum : line 5 [hʌm]If something hums, it makes a low continuous noise. 发出连续低沉的声音4 stink:line 7[stɪŋk]To stink means to smell very bad. 发臭5 patch: line 7[pætʃ]A patch on a surface is a part of it that is different in appearance from the area around it. (与周围不同的) 块; 片6 uneven: line 8[ʌn'iːv(ə)n]An uneven surface or edge is not smooth, flat, or straight. 不平坦的; 不直的7 pavement:line 8/ˈpeɪvmənt/The pavement is the hard surface of a road. 路面8 jostle: line 8['dʒɒs(ə)l]If people jostle you, they bump against you or push you in a way that annoys you, usually because you are in a crowd and they are trying to get past you. 推搡; 推挤9 grip :line 9[grɪp]If you grip something, you take hold of it with your hand and continue to hold it firmly. 紧握10 aisle;line 10[aɪl]An aisle is a long narrow gap that people can walk along between rows of seats in a public building(座位间或货架间的) 通道11 rail : line 11[reɪl]A rail is a horizontal bar attached to posts or around the edge of something as a fence or support. 栏杆,铁轨12 dimple : line13['dɪmp(ə)l]A dimple is a small hollow in someone's cheek or chin, often one that you can see when they smile. 酒窝13 inherit :line 17[ɪn'herɪt]If you inherit a characteristic or quality, you are born with it, because your parents or ancestors also had it. 经遗传而得(特征、品质等)14 candor : line 18 ['kændɚ]admission 坦白Page 41 smooth : line 1[smuːð]A smooth surface has no roughness, lumps, or holes. 光滑的2 hub : line 2 [hʌb]You can describe a place as a hub of an activity when it is a very important centre for that activity. 活动中心3 pillar : line 3['pɪlə]A pillar is a tall solid structure that is usually used to support part of a building. 柱子4 elevate : line 4 ['elɪveɪt]If you elevate something, you raise it higher. 举起; 抬高When someone or something achieves a more important rank or status, you can say that they are elevated to it. 提拔[正式]5 dauntless: line 6['dɔːntlɪs]A dauntless person is brave and confident and not easily frightened. 无所畏惧的[文学性]6 repave;line 8[ri'pev]重新铺砌;重新铺筑(道路等)7 crack : line 11 [kræk]If something hard cracks, or if you crack it, it becomes slightly damaged, with lines appearing on its surface. 使…破裂; 破裂8 patchy : line 11 ['pætʃi]A patchy substance or colour exists in some places but not in others, or is thick in some places and thin in others. 分布不均衡的9 sway :line 13 [sweɪ]When people or things sway, they lean or swing slowly from one side to the other. 摇摆10 clutch: line 14[klʌtʃ]If you clutch at something or clutch something, you hold it tightly, usually because you are afraid or anxious. (因为害怕或焦虑而) 抓牢11 stumble: line 20 ['stʌmb(ə)l]If you stumble, you put your foot down awkwardly while you are walking or running and nearly fall over. 踉跄; 绊脚12 slack : line 21 [slæk]Something that is slack is loose and not firmly stretched or tightly in position. 松散的; 松弛的; 宽松的Page 51 devour : line 9[dɪ'vaʊə]If a person or animal devours something, they eat it quickly and eagerly. 狼吞虎咽地吃2 erudite: line 25['erʊdaɪt]If you describe someone as erudite, you mean that they have or show great academic knowledge.3 amity : line 25['æmɪtɪ]Amity is peaceful, friendly relations between people or countries. 和睦; 友好关系[正式]4 mania: line 8['meɪnɪə]If you say that a person or group has a mania for something, you mean that they enjoy it very much or spend a lot of time on it. 狂热Mania is a mental illness which causes the sufferer to become very worried or concerned about something. 狂躁症Page 71 hellion:line 5['heljən]a rough or rowdy person, esp a child; troublemaker 捣蛋鬼(Also called heller)[美国英语][非正式]2 administrator: line 2 [əd'mɪnɪstreɪtə]An administrator is a person whose job involves helping to organize and supervise the way that an organization or institution functions. 行政人员; 管理人员3 eliminate :line 11[ɪ'lɪmɪneɪt]To eliminate something, especially something you do not want or need, means to remove it completely. 根除[正式]4 dictate :line 17[dɪk'teɪt]If you dictate something, you say or read it aloud for someone else to write down. 口授; 使听写5 idle::line 17 ['aidlə]If people who were working are idle, they have no jobs or work. 无事可做的6 supersede: line 17[,suːpə'siːd; ,sjuː-If something is superseded by something newer, it is replaced because it has become old-fashioned or unacceptable. 取代Page 11grin :line 12 [grɪn]When you grin, you smile broadly. 咧嘴笑2. recline: line 26 [rɪ'klaɪn]When a seat reclines or when you recline it, you lower the back so that it is more comfortable to sit in. 使向后倾斜; 向后倾斜Page 131 squeeze:line 4[skwiːz]If you squeeze something, you press it firmly, usually with your hands. (常指用手) 挤压; 紧捏2 vial :line 7['vaɪəl]A vial is a very small bottle that is used to hold something such as perfume or medicine. (装香水、药物等的)小瓶3 scowl : line4 [skaʊl]When someone scowls, an angry or hostile expression appears on their face. 作怒容; 绷着脸4 vibrate: line 18 [vaɪ'breɪt]If something vibrates or if you vibrate it, it shakes with repeated small, quick movements. 使颤动; 颤动Page 151 clench: line 15[klen(t)ʃ]When you clench your fist or your fist clenches, you curl your fingers up tightly, usually because you are very angry. (常指因生气而) 握紧(拳头)When you clench your teeth or they clench, you squeeze your teeth together firmly, usually because you are angry or upset. (常指因生气或不安而) 咬紧(牙)2 cringe: line 21 [krɪn(d)ʒ]If you cringe at something, you feel embarrassed or disgusted, and perhaps show this feeling in your expression or by making a slight movement. 感到局促不安3 vicious ;line 22['vɪʃəs]A vicious person or a vicious blow is violent and cruel. 凶残的Page 161 squeal line 5 [skwiːl]If someone or something squeals, they make a long, high-pitched sound. 发出长而尖的声音2 crumple line 22 ['krʌmp(ə)l]If you crumple something such as paper or cloth, or if it crumples, it is squashed and becomes full of untidy creases and folds. 弄皱; 起皱3 apprehend last line[æprɪ'hend]If the police apprehend someone, they catch them and arrest them. 逮捕[正式] Page 171 dread: line 2[dred]If you dread something which may happen, you feel very anxious and unhappy about it because you think it will be unpleasant or upsetting. 害怕; 担忧2 shudder: line 18 ['ʃʌdə]If you shudder, you shake with fear, horror, or disgust, or because you are cold. (因害怕、恐惧、厌恶或寒冷) 发抖3 irrational: line 18[ɪ'ræʃ(ə)n(ə)l]If you describe someone's feelings and behaviour as irrational, you mean they are not based on logical reasons or clear thinking. 不理性的4 snarl: line 22 [snɑːl]When an animal snarls, it makes a fierce, rough sound in its throat while showing its teeth. (动物) 露齿嗥叫5 ripple;line 23 ['rɪp(ə)l]Ripples are little waves on the surface of water caused by the wind or by something moving in or on the water. 涟漪Page 191 tilt line2 [tɪlt]If you tilt an object or if it tilts, it moves into a sloping position with one end or side higher than the other. 使倾斜; 倾斜2 perplex: line 13 [pə'pleks]If something perplexes you, it confuses and worries you because you do not understand it or because it causes you difficulty. 使困惑和忧虑Page 211 simulation : line 10[,sɪmjʊ'leɪʃən]Simulation is the process of simulating something or the result of simulating it. 模拟; 模拟结果2 linear : line 11 ['lɪnɪə]A linear process or development is one in which something changes or progressesstraight from one stage to another, and has a starting point and an ending point. 线性的Page 241 curb : line 2[kɜːb]Stone around the street .If you curb something, you control it and keep it within limits. 抑制2 dangle : line 6 ['dæŋg(ə)l]If something dangles from somewhere or if you dangle it somewhere, it hangs or swings loosely. 悬挂; 悬摆3 precariously: line 6 [pri'kɛəriəsli]If your situation is precarious, you are not in complete control of events and might fail in what you are doing at any moment. (情况) 不稳定的4 renovation : line 8[,renə'veɪʃn]renovate['renəveɪt]If someone renovates an old building, they repair and improve it and get it back into good condition. 修复; 整修5 marsh : line 10[mɑːʃ]A marsh is a wet, muddy area of land. 沼泽6 genuine: line 20['dʒenjʊɪn]Genuine is used to describe people and things that are exactly what they appear to be, and are not false or an imitation. 真正的7 forsake : line 21 [fə'seɪk]If you forsake someone, you leave them when you should have stayed, or you stop helping them or looking after them. 离弃[文学性]8 sector ;line 23['sektə]A particular sector of a country's economy is the part connected with that specified type of industry. (经济的) 部门9 skeleton: line 24['skelɪt(ə)n]Your skeleton is the framework of bones in your body. 骨骼Page 251 sewage : line 2['suːɪdʒ]Sewage is waste matter such as faeces(粪便排泄物) or dirty water from homes and factories, which flows away through sewers. (下水道排出的) 废物2 initiation: line 5[ɪ,nɪʃɪ'eɪʃn]The initiation of something is the starting of it. 开始; 发起3 sag : line 12 [sæg]When something sags, it hangs down loosely or sinks downward in the middle. (中间部分) 下垂; 下陷Page 261 tug: line 3[tʌg]If you tug something or tug at it, you give it a quick and usually strong pull. 猛拉; 拽retort: line 10[rɪ'tɔːt]To retort means to reply angrily to someone. 反驳[书面]Page 271 adornment : line 2[ə'dɔːnm(ə)nt]Adornment is the process of making something more beautiful by adding something to it. 装饰2 rectangle :line 8 ['rektæŋg(ə)l]A rectangle is a four-sided shape whose corners are all ninety-degree angles. Each side of a rectangle is the same length as the one opposite to it. 长方形3 lawn : line 8[lɔːn]A lawn is an area of grass that is kept cut short and is usually part of someone's garden, or part of a park. 草坪4 crabgrass: line 9['kræbɡræs]杂草Page 281 suppress: line 13[sə'pres]If someone in authority suppresses an activity, they prevent it from continuing, by using force or making it illegal. 镇压; 压制Page 29 :1duplicity: line 1/djuːˈplɪsɪtɪ/you accuse someone of duplicity, you mean that they are deceitful. 奸诈[正式2 tentative: line 14['tentətiv]Tentative agreements, plans, or arrangements are not definite or certain, but have been made as a first step. 初步的Page 301 accusatory : line 6 [ə'kjuːzət(ə)rɪ]An accusatory look, remark, or tone of voice suggests blame or criticism.2 prob : line 6 ][prɒb] probale probably problem probate probabilityPage 311 opinionated: line 11[ə'pɪnjəneɪtɪd]If you describe someone as opinionated, you mean that they have very strong opinions and refuse to accept that they may be wrong. 固执己见的2 recruit : line 20 [rɪ'kruːt]If you recruit people for an organization, you select them and persuade them to join it or work for it. 招收; 招募Page 321 wary: line['weərɪ]If you are wary of something or someone, you are cautious because you do not know much about them and you believe they may be dangerous or cause problems. 小心的; 提防的Page 331 corrupt : line 10 /kəˈrʌpt/Someone who is corrupt behaves in a way that is morally wrong, especially by doing dishonest or illegal things in return for money or power. 腐败的2 impeccable : line 12[ɪm'pekəb(ə)l]If you describe something such as someone's behaviour or appearance as impeccable, you are emphasizing that it is perfect and has no faults. 无可挑剔的[强调]3 fortitude : line 13['fɔːtɪtjuːd]If you say that someone has shown fortitude, you admire them for being brave, calm, and uncomplaining when they have experienced something unpleasant or painful. 刚毅[正式]4 ultimate : line 16 ['ʌltɪmət]You use ultimate to describe the final result or aim of a long series of events. 最终的Page 341 chastise :line 16[tʃæ'staɪz]If you chastise someone, you speak to them angrily or punish them for something wrong that they have done. 训斥; 责罚[正式]2 devastate : line 24['devəsteɪt]If something devastates an area or a place, it damages it very badly or destroys it totally. 严重破坏; 彻底摧毁Page 351 infant : line 1 ['ɪnf(ə)nt]An infant is a baby or very young child. 婴儿; 幼儿[正式]2 lust : line 22[lʌst]A lust for something is a very strong and eager desire to have it. 欲望Page 361 startle : line 20 ['stɑːt(ə)l]If something sudden and unexpected startles you, it surprises and frightens you slightly. 使受惊Page 391 subsume : line 10[səb'sju:m]If something is subsumed within a larger group or class, it is included within it, rather than being considered as something separate. 包括; 归入2 hive : line 10 [haɪv]If you describe a place as a hive of activity, you approve of the fact that there is a lot of activity there or that people are busy working there. 忙碌的地方[表赞许]3 outward : line 11['aʊtwəd]The outward feelings, qualities, or attitudes of someone or something are the ones they appear to have rather than the ones that they actually have.表面看起来的Page 401 reverse :line 40 [rɪ'vɜːs]1. V-T When someone or something reverses a decision, policy, or trend, they change it to the opposite decision, policy, or trend. 使(决定、政策、趋势) 转向; 逆转2. V-T If you reverse the order of a set of things, you arrange them in the opposite order, so that the first thing comes last. 颠倒(顺序)Page 421 precipice : line 5 ['presɪpɪs]A precipice is a very steep cliff on a mountain. 悬崖; 峭壁2 solemn: line 6 ['sɒləm]Someone or something that is solemn is very serious rather than cheerful or humorous. (人) 严肃的; (物) 庄严的3 ideology : line 8[,aɪdɪ'ɒlədʒɪ; ɪd-]An ideology is a set of beliefs, especially the political beliefs on which people, parties, or countries base their actions. 意识形态4 cowardice : line 4['kaʊədɪs]If you call someone a coward, you disapprove of them because they are easily frightened and avoid dangerous or difficult situations. 胆小鬼[表不满]Page 441 muffle: line 6 ['mʌf(ə)l]If something muffles a sound, it makes it quieter and more difficult to hear. 压低(声音)2 syllable : line 9['sɪləb(ə)l]A syllable is a part of a word that contains a single vowel sound and that is pronounced as a unit. So, for example, "book" has one syllable, and "reading" has two syllables. 音节Page 471 blade : line 14[bleɪd]The blade of a knife, axe, or saw is the edge, which is used for cutting. 刃Page 491 wrench: line 8[ren(t)ʃ]If you wrench something that is fixed in a particular position, you pull or twist it violently, in order to move or remove it. 猛拽; 猛扭2 headquarter :line 15['hedkwɔːtə]设立总部在…设总部3 hell: line 23[hel]In some religions, hell is the place where the Devil lives, and where wicked people are sent to be punished when they die. Hell is usually imagined as being under the ground and full of flames. 地狱Page 501 crisp : line 1[krɪsp]Weather that is pleasantly fresh, cold, and dry can be described as crisp. 清爽的(天气)2sprawl: line 4[sprɔːl]If you sprawl somewhere, you sit or lie down with your legs and arms spread out in a careless way. 伸开四肢坐着; 摊开四肢躺着,蔓延3 sprint: line 5[sprɪnt]The sprint is a short, fast running race. 短跑赛4 dissipate: line 6['dɪsɪpeɪt]When something dissipates or when you dissipate it, it becomes less or becomes less strong until it disappears or goes away completely. 驱散; 消散[正式]5 glide : line 18[glaɪd]If you glide somewhere, you move silently and in a smooth and effortless way. 滑行Page 511 slam : line 3 [slæm]If you slam a door or window or if it slams, it shuts noisily and with great force. 砰地关上; 使劲关上2 strain : line 9 [strein]To strain something means to make it do more than it is able to do. 使受到压力3sail: line 10[seɪl]You say a ship sails when it moves over the sea. 航行Page 521 faint :line 17['feint]A faint sound, colour, mark, feeling, or quality has very little strength or intensity. 微弱的Page 531 linger : line 6 ['lɪŋgə]When something such as an idea, feeling, or illness lingers, it continues to exist for a long time, often much longer than expected. (想法、感觉、疾病) 继续存留2 hint:line 6 [hɪnt]A hint is a suggestion about something that is made in an indirect way. 暗示3 smear : line 53 [smɪə]Make sth unclear.Page 541 crook : line 2[krʊk]If you crook your arm or finger, you bend it. 弯曲Page 551 prickle : line 3 ['prɪk(ə)l]If your skin prickles, it feels as if a lot of small sharp points are being stuck into it, either because of something touching it or because you feel a strong emotion. (因被刺或强烈的感触而)感到刺痛2 shin : line 3/ʃɪn/Your shins are the front parts of your legs between your knees and your ankles. 胫3 wail : line 14[weɪl]someone wails, they make long, loud, high-pitched cries which express sorrow or pain. 哀号Page 561 stern:line 3[stɜːn]Stern words or actions are very severe. (话语或行为) 严厉的2 sting: line 16/stɪŋ/If a plant, animal, or insect stings you, a sharp part of it, usually covered with poison, is pushed into your skin so that you feel a sharp pain. 刺; 叮2 scandalous : line 19['skændələs]Scandalous behaviour or activity is considered immoral and shocking. 不道德的; 令人震惊的Page 58Surge: line 21[sɜːdʒ]A surge is a sudden large increase in something that has previously been steady, or has only increased or developed slowly. 剧增Page 591 cradle : line 2['kreɪd(ə)l]A cradle is a baby's bed with high sides. Cradles often have curved bases so that they rock from side to side. 摇篮Page 62Pit : line 16 [pɪt]A pit is a large hole that is dug in the ground. 大坑Page 641 chasm : line 16 ['kæzəm]A chasm is a very deep crack in rock, earth, or ice. (岩石、地面或冰上的) 大裂口2 tame : line 17[teim]A tame animal or bird is one that is not afraid of humans. 驯服的Page 65nudge : line 2 from last: [nʌdʒ]If you nudge someone, you push them gently, usually with your elbow, in order to draw their attention to something. (常用肘为引起注意) 轻推Page 661 twitch : line 12 [twɪtʃ]If something, especially a part of your body, twitches or if you twitch it, it makes a little jumping movement. (身体等) 抽动2 pierce : line 16[pɪəs]If a sharp object pierces something, or if you pierce something with a sharp object, the object goes into it and makes a hole in it. 刺穿3 menace : line 18['menəs]If you say that someone or something is a menace to other people or things, you mean that person or thing is likely to cause serious harm. 威胁Page 701 compound : line 20['kɒmpaʊnd]A compound is an enclosed area of land that is used for a particular purpose. 作特定用途的围地2 proportion :line 2 from last [prə'pɔːʃ(ə)n]A proportion of a group or an amount is a part of it. 部分[正式]Page 771 drastically : line 1 ['dræstikəli]A drastic change is a very great change. 剧烈的2 eradicate : line 5 [ɪ'rædɪkeɪt]To eradicate something means to get rid of it completely. 根除[正式]3 idiot : line 17['ɪdɪət]If you call someone an idiot, you are showing that you think they are very stupid or have done something very stupid. 笨蛋[表不满]Page 781 crane : line 5[kreɪn]If you crane your neck or head, you stretch your neck in a particular direction in order to see or hear something better. 伸长(脖子)2 delicate : line 13 ['delɪkət]Something that is delicate is small and beautifully shaped. 精巧的; 精美的3 trigger : line 16 ['trɪgə]The trigger of a gun is a small lever which you pull to fire it. 扳机4 recoil : line 18 [rɪ'kɒɪl]If something makes you recoil, you move your body quickly away from it because it frightens, offends, or hurts you. 躲闪; 畏缩Page 791 massage : last line ['mæsɑːʒ; mə'sɑːʒ; -dʒ]Massage is the action of squeezing and rubbing someone's body, as a way of making them relax or reducing their pain. 按摩Page 811 deception : line 3 [dɪ'sepʃ(ə)n]Deceit is behaviour that is deliberately intended to make people believe something which is not true. 欺骗2 buddy ;line 13 ['bʌdɪ]A buddy is a close friend, usually a male friend of a man. 好朋友(常用于男子之间)3 bump : line 19 [bʌmp]If you bump into something or someone, you accidentally hit them while you are moving.Page 821 strip : line 5 [strɪp]A strip of something such as paper, cloth, or food is a long, narrow piece of it. (纸、布或食物的) 条If you strip, you take off your clothes. 脱衣服2 naked : line 5 ['neɪkɪd]Someone who is naked is not wearing any clothes.3 frigid : line 13['frɪdʒɪd]Frigid means extremely cold. 极冷的4 glint : line 13[glɪnt]IIf something glints, it produces or reflects a quick flash of light. 闪光[书面]5 chuckle : line 3 from last['tʃʌk(ə)l]When you chuckle, you laugh quietly. 轻声地笑Page 831 creaky : line2 ['kriːkɪ]If something creaks, it makes a short, high-pitched sound when it moves. 嘎吱作响2 priority : line 6[praɪ'ɒrɪtɪ]If something is a priority, it is the most important thing you have to do or deal with, or must be done or dealt with before everything else you have to do. 优先处理的事2 punch : line 10[pʌn(t)ʃ]If you punch someone or something, you hit them hard with your fist. 用拳猛击3 demonstrate : last line ['demənstreɪt]To demonstrate a fact means to make it clear to people. 证明Page 841 rip : line 6 from last [rip]When something rips or when you rip it, you tear it forcefully with your hands or witha tool such as a knife. 撕; 撕裂2 cage : line 6 from last [keɪdʒ]A cage is a structure of wire or metal bars in which birds or animals are kept. 笼子Page 851 intimidate : line 11[ɪn'tɪmɪdeɪt]If you intimidate someone, you deliberately make them frightened enough to do what you want them to do. 恐吓; 威胁2 dye : line3 from last [daɪ]If you dye something such as hair or cloth, you change its colour by soaking it in a special liquid. 染色3 bellybutton : last line['belɪ,bʌtn]肚脐Page 861 nipple : line 1['nɪp(ə)l]The nipples on someone's body are the two small pieces of slightly hard flesh on their chest. Babies suck milk from their mothers' breasts through their mothers' nipples. 乳头2 groan : line 2 [grəʊn]If you groan, you make a long, low sound because you are in pain, or because you are upset or unhappy about something. 呻吟3 giddy :line 5['gɪdɪ]If you feel giddy, you feel unsteady and think that you are about to fall over, usually because you are not well. 眩晕的4 fatigue : line5 [fə'tiːg]Fatigue is a feeling of extreme physical or mental tiredness. 疲惫5 parlor : line 7 ['pɑrlɚ]客厅;会客室;业务室6 gigantic : line 13 [dʒaɪ'gæntɪk]If you describe something as gigantic, you are emphasizing that it is extremely large in size, amount, or degree. 巨大的[强调]7 stuck : line 18 the past form of stickPage 891 raven : ['reɪv(ə)n]A raven is a large bird with shiny black feathers and a deep harsh call. 渡鸦2 sketch :last line [sketʃ]A sketch is a drawing that is done quickly without a lot of details. Artists often use sketches as a preparation for a more detailed painting or drawing. 草图; 略图; 素描Page 901wedge : line 13[wedʒ]a thing cause cracks 导致分裂的东西If you wedge something, you force it to remain in a particular position by holding it there tightly or by sticking something next to it to prevent it from moving. 把…楔住; 把…抵牢Page 911 unravel : line 5[ʌn'rævl]If you unravel something that is knotted, woven, or knitted, or if it unravels, itbecomes one straight piece again or separates into its different threads. 解开; 拆散2 reprieve : line 5[rɪ'priːv]If someone who has been sentenced in a court is reprieved, their punishment is officially delayed or cancelled. (被判) 缓刑; 撤销3 wince : line 9[wɪns]If you wince, the muscles of your face tighten suddenly because you have felt a pain or because you have just seen, heard, or remembered something unpleasant. (由于疼痛或看见、听到或记起某些不愉快的事而) 龇牙咧嘴4 shield : line 2 from last [ʃiːld]Something or someone which is a shield against a particular danger or risk provides protection from it. 防护物; 保护人Page 921 crawl: line 16[krɔːl]When you crawl, you move forward on your hands and knees2 womb: line 17[wuːm]A woman's womb is the part inside her body where a baby grows before it is born. Page 931 grimace : line 5 from last ['grɪməs; grɪ'meɪs]If you grimace, you twist your face in an ugly way because you are annoyed, disgusted, or in pain. (因不快、厌恶或痛苦等) 扮怪相Page 951 concede: line 8 [kən'siːd]If you concede something, you admit, often unwillingly, that it is true or correct. (常指不情愿地) 承认2 surrender : line13[sə'rendə]If you surrender, you stop fighting or resisting someone and agree that you have been beaten. 投降; 屈服Page 1001 relent : line 8 from last [rɪ'lent]If you relent, you allow someone to do something that you had previously refused to allow them to do. 发慈悲Page 1041 soak :line 4 from last [səʊk]If you soak something or leave it to soak, you put it into a liquid and leave it there. 浸泡Page 1061 stack : line 15[stæk]A stack of things is a pile of them. 摞; 堆Page 1071antagonize line 1[æn'tæɡənaɪz]If you antagonize someone, you make them feel angry or hostile toward you. 使(某人) 对自己产生敌意Page 1081 irritation : line10[ɪrɪ'teɪʃn]Irritation is a feeling of annoyance, especially when something is happening that you。

初三英语听力细节捕捉技巧单选题40 题1. You will hear a conversation between two people. One says, "I saw Mr. Smith at the place where we can buy books just now." Where did the speaker see Mr. Smith?A. At the libraryB. At the bookstoreC. At the supermarket答案:B。

解析:听力原文提到在可以买书的地方看到了Mr. Smith,书店是可以买书的地方,A选项图书馆主要是借书的地方,C选项超市是购物的地方不是专门买书的地方,所以正确答案是B。

2. Listen to the dialogue. A girl says, "My mother is always busy in the place where she helps sick people." What does the girl's mother do?A. A teacherB. A nurseC. A cook答案:B。

解析:根据原文提到在帮助病人的地方很忙,护士是在医院帮助病人的职业,A选项教师是在学校教书的,C选项厨师是在厨房做饭的,所以答案是B。

3. In the conversation, a boy says, "I'm going to meet my sister at half past three after school." What time will the boy meet his sister?A. 3:00B. 3:30C. 4:00答案:B。

解析:听力中明确提到是三点半见面,A选项是三点,C选项是四点,所以正确答案是B。

2024-2025学年山西省英语初三上学期期中自测试题及答案指导一、听力部分(本大题有20小题,每小题1分,共20分)1、What is the weather like today?A. It’s sunny.B. It’s cloudy.C. It’s rainy.Answer: AExplanation: The question asks about the weather today. The correct answer is “It’s sunny,” which is option A. The other options, B and C, are incorrect as they describe different weather conditions.2、How old is Mike?A. He’s twelve.B. He’s thirteen.C. He’s fourteen.Answer: BExplanation: The question asks about Mike’s age. The correct answer is “He’s thirteen,” which is option B. The other options, A and C, are incorrect as they provide different ages.3、Listen to the conversation and choose the best answer to the question you hear. (Listen to the audio clip provided by your teacher or read the following transcript if no audio is available.)Transcript:W: Hey, Tom, did you finish reading the article about renewable energy for our project?M: Yeah, it was really interesting. I think we should focus on solar power for our presentation.W: That sounds like a great idea. Do you know any specific facts that we could use?Question:What topic are Tom and the woman discussing for their project?A. Wind powerB. Solar powerC. Hydroelectric powerAnswer: B. Solar powerExplanation: In the dialogue, Tom mentions that he finished reading an article about renewable energy and suggests focusing on solar power for their presentation, indicating that solar power is the topic they are considering for their project.4、Listen to the short passage and select the correct answer according to what you hear. (Listen to the audio clip provided by your teacher or read thefollowing passage if no audio is available.)Passage:“The Amazon rainforest is home to millions of species of plants and animals, many of which cannot be found anywhere else in the world. It plays a crucial role in maintaining the Earth’s climate by absorbing carbon dioxide and producing more than 20 percent of the world’s oxygen supply. Unfortunately, deforestation continues to threaten this natural wonder, with thousands of acres being lost every year.”Question:What threat does the passage mention affecting the Amazon rainforest?A. Global warmingB. DeforestationC. PollutionAnswer: B. DeforestationExplanation: The passage explicitly states that “deforestation continues to threaten this natural wonder,” directly identifying deforestation as the threat to the Amazon rainforest.5、Listen to the dialogue between two students, Tom and Lily, talking about their weekend plans. After listening, answer the following question.Question: What does Tom plan to do on Saturday afternoon?A. Go shoppingB. Watch a movieC. Visit a museumD. Go to the gymAnswer: BExplanation: In the dialogue, Tom says, “I think I’ll watch a movie on Saturday afternoon. I’ve been looking forward to it for a while.”6、Listen to a short conversation between a teacher and a student, Alex, discussing the student’s assignment. After listening, answer the following question.Question: What is the teacher’s main concern about Alex’s assignment?A. The deadlineB. The quality of the workC. The difficulty levelD. The subject matterAnswer: BExplanation: The teacher s ays, “I’ve reviewed your assignment, and I must say, the quality of your work is not up to the mark. You need to improve your writing skills.”7、What does the woman want to do this weekend?•A) Go to a concert•B) Visit a museum•C) See a movieAnswer: C) See a movieExplanation: In the dialogue, the woman expresses her desire to watch the latest superhero film that just came out. The man agrees, and they make plans to go to the cinema on Saturday evening.8、When will the party start?•A) At 6:00 PM•B) At 7:00 PM•C) At 8:00 PMAnswer: B) At 7:00 PMExplanation: The conversation mentions that the guests are expected to arrive at seven o’clock in the evening. The hostess confirms that she has informed all the invitees about the starting time, which is 7:00 PM.9.You hear a conversation between two students in a school corridor. StudentA is discussing a homework assignment with Student B.A. What subject is the homework assignment for?B. Why does Student B seem to be in a hurry?Answer: A. What subject is the homework assignment for?Answer: B. Why does Student B seem to be in a hurry?Correct Answer: A. The homework assignment is for English.B. Student B is in a hurry because he has a soccer practice later.10.You hear a monologue by a teacher in a classroom, discussing the importance of studying for exams.A. What does the teacher recommend for students who are studying for exams?B. How does the teacher describe the impact of proper study habits?Answer: A. What does the teacher recommend for students who are studying for exams?Answer: B. How does the teacher describe the impact of proper study habits?Correct Answer: A. The teacher recommends making study schedules and taking regular breaks.B. The teacher describes the impact of proper study habits as helping students to retain information better and perform better on exams.11、What does the man mean?A. He can’t attend the party.B. He will bring some snacks to the party.C. He forgot to invite his friends.D. He has already prepared everything for the party.Answer: B.Explanation: The man mentions he’ll stop by the store to pick up something for the party, implying he will bring snacks.Conversation 2(Question will be played on the recording.)12、Where will the speakers probably go?A. To the library.B. To the park.C. To the cinema.D. To the restaurant.Answer: C.Explanation: The woman suggests seeing a movie, and the man agrees, indicating they will likely go to the cinema.13.W: Have you finished your homework yet?M: Yes, I finished it last night. It took me about three hours.Q: How long did it take the man to finish his homework?A: 3 hours.解析:对话中男士提到他花了大约三个小时完成作业,因此答案为3 hours。

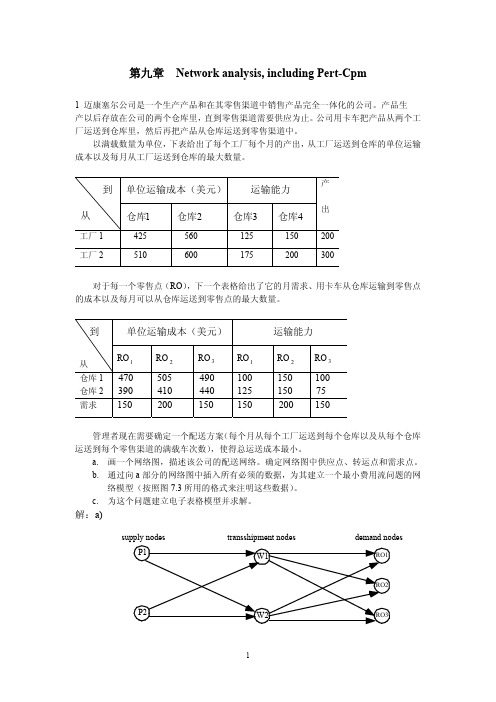

Turning the Tables: Language and Spatial Reasoning*Peggy Li and Lila GleitmanUniversity of Pennsylvania(Submitted December 1999)Running head: LANGUAGE AND SPATIAL REASONING_____________*We thank Kathleen Hoffman, Leslie Koo, Aharon Charnov, Lorraine Daley, Jill Kleczko, and Aurit Lazerus for helping in data collection. We especially thank Kathleen Hoffman for getting us started on the project. We also thank Henry Gleitman, Robin Clark, and the members of the CHEESE seminar for important theoretical and methodological contributions. The research was supported by a predoctoral Fellowship to the first author from the Institute for Research in Cognitive Science, University of Pennsylvania, by NSF Grant # SBR8920230, and by NIH Grant # 1R01HD375071.Requests for reprints should be sent to P. Li or L. R. Gleitman, Institute for Research in Cognitive Science, University of Pennsylvania, 3401 Walnut St. Suite 400A, Philadelphia, PA. 19104. The e-mail addresses for the authors are pegs@ and gleitman@.AbstractThis paper investigates possible influences of the lexical resources of individual languages on the conceptual organization and reasoning processes of their users. That there are such powerful and pervasive influences of language on thought is the thesis of the Whorf-Sapir linguistic relativity hypothesis which, after a lengthy period in intellectual limbo, has recently returned to prominence in the anthropological, linguistic, and psycholinguistic literatures. Our point of departure is an influential group of cross-linguistic studies that appear to show that spatial reasoning is strongly affected by the spatial lexicon in everyday use in a community (Brown and Levinson, 1993b; Pederson et al., 1998). Specifically, certain groups use an absolute spatial-coordinate system to refer to directions and positions even within small and nearby regions ("to the north of that coconut tree") whereas English uses a relative, body-oriented system ("to the left of that tree"). The prior findings have been that users of these two types of spatial systems solve rotation problems in different ways, ways predicted by the language-particular lexicons. The present studies reproduce these different problem-solving strategies in monolingual speakers of English by manipulating landmark cues, suggesting that the prior results were not language effects at all. The results are discussed as buttressing the view that linguistic idiosyncracies do not materially restrict the thought processes of their users.I. IntroductionLanguage has means for making reference to the objects, relations, properties, and events that populate our everyday world. Commonsensically, the relevant linguistic categories and structures are more-or-less straightforward mappings from a preexisting conceptual space, programmed into our biological nature. This perspective would begin to account for the fact that the grammars and lexicons of all languages are broadly similar, despite historical isolation and cultural disparities among them; moreover, that the language learning functions for young species-members look about the same across languages.But having assigned the language identities to underlying conceptual identities among their users, what are we to make of the — less pervasive, but also real — linguistic differences among languages? Could it be that the situation is symmetrical? That insofar as languages do differ from each other, there are corresponding differences in the modes of thought of their users? More marvelously by far, could the linguistic differences be the original causes of distinctions in the way peoples categorize and reason? Benjamin Whorf and Edward Sapir offer a positive answer to such questions. In Sapir’s words:Human beings do not live in the objective world alone, nor alone in the world of social activity as ordinarily understood, but are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression...the “real world” is to a large extent unconsciously built up on the language habits of the group (E. Sapir as quoted by Whorf 1956; p. 134).The popularity of this position has diminished considerably in academic favor in the last half of this century, for two main reasons. First, the universalist position of Chomskian linguistics, with its potential for explaining the similarities of language learning in children all over the world, captured the imagination of a generation of scholars. Second, a series of experimental studiesdocumenting the independence of hue and brightness perception from linguistic color-naming practices seemed to settle the controversy in favor of the universalists (see particularly Berlin and Kay, 1969; Heider, 1972; Heider and Oliver, 1972; Jameson and Hurvich, 1978).Recently, however, a number of discussions and experimental studies have reawakened interest in the question of how language may influence and shape thought. Rightly, the studies of color vision and naming, elegant and compelling as they were, have been judged too topically narrow as the basis for writing off the position as a whole. Even more important, effects of language use, or indeed any learning effects at all, would be least likely in peripheral, low-level perceptual processes such as hue discrimination. Therefore they do not constitute a fair test (Lucy, 1996).Many recent studies have focused on a more central perceptual domain: commonalities and differences in how languages treat spatial properties and relations (Jackendoff, 1996; Talmy, 1978). To be sure, ultimately linguistic-spatial categories must be built upon a universal perceptual base originating in brain structure shared by all nonpathological humans (Landau and Jackendoff, 1993). But within these constraints there is room for languages to differ. This possibility is instantiated in several crosslinguistic differences in spatial encoding (Brown and Levinson, 1992, 1993a, 1993b; Bowerman, 1996a, 1996b). Children appear to find it easy to acquire whatever spatial-linguistic categories their language makes available in its simplest vocabulary and phraseology (Bowerman, 1996a, 1996b; Choi and Bowerman, 1991) and to tailor their speech to accommodate to the domains of applicability of the language-specific terms (Slobin, 1991).We pursue here the further question of whether such linguistic differences in the mapping of space onto language impact the ways that members of a speech community come to conceptualize the world, as Whorf and Sapir would have it. Do the differences in how people talk result indifferences in how they think? Specifically, could the cross-linguistically observed differences in spatial categorization influence nonlinguistic spatial categorization? Recently, several commentators have posited that language differences in the spatial domain actually do have such nonlinguistic effects on category formation and category deployment in tasks requiring spatial reasoning.Our point of departure for the current studies comes from a major comparative cross-linguistic research inquiry focusing on the relationship between linguistic patterning and spatial reasoning (Brown and Levinson, 1993b; Pederson, Danziger, Wilkins, Levinson, Kita, and Senet 1998). There are in general three ways in which languages express spatial regions and orientations: in terms of the inherent properties of the objects themselves (“the front of the house,” “ the nose of the plane”), their cardinal positions (“west of Cleveland”), or their positions relative to the orientation of the speaker or listener (“on your left,” “to the right of the toolshed”). Most languages have the formal resources to make reference to spatial arrays in all of these ways. But as Pederson et al. have documented, in most cases a given speech community favors one of them, at least for small-scale description. Though in English we could say “Give me the spoon that’s northeast of your teacup,” this sounds pretty ludicrous. We are strongly inclined to use relative terminology (“...to the left of your teacup”) instead.Conceptually, the first step in the cross-linguistic project has been to document the vocabulary by which speakers typically describe the positions and movements of objects in space. Standardized procedures were established for eliciting these spatial descriptions from the native speakers of a broad range of languages, living in both small-scale traditional (e.g., Mayans, Austronesians) and large-scale (Japanese, Dutch) cultural communities: see Pederson et al., 1998, for a description of these procedures. The second step was to devise experimental procedureswhich required subjects of differing linguistic background to observe spatial arrays, and then to identify or reconstruct “the same” array after being reoriented, usually by 180 degrees. The question under experimental review is whether incommensurabilities in the spatial vocabularies of the subject populations predict differences in their performance on the identification and reconstruction tasks after reorientation.Absolute versus Relative spatial encoding systemsThe major spatio-linguistic distinction studied by Pederson et al. is between absolute versus relative encoding of spatial directions and locations. For example, Los Angeles is always to the west of New York, independent of the position of an observer; hence west is an absolute spatial term. In contrast, for an observer in Cincinnati facing north, Los Angeles is to her left and New York is to her right; but if she turns to face south, Los Angeles is to her right. Hence left is a term describing location relative to the body-orientation of the observer herself.As Pederson et al. have described, most languages with which we are familiar favor relative spatial terminology for describing small-scale spatial layouts. But for many other language communities, the facts about everyday speech conventions are otherwise. An example described in detail in Brown and Levinson (1992) is Tzeltal, a language spoken by about 15,000 Mayans in the area of Municipo Tenejapa, in Chiapas, Mexico. Their village is on a hill. In Brown and Levinson’s words,...there is a system of ‘uphill’/’downhill’ orientation that is fundamental to the spatial system...based on the overall inclination of the terrain of Tenejapa from high South to low North, so that [the term for] ‘uphill’ (and correspondingly, ‘downhill’...) [make] primary reference to the actual inclination of the land...the terms may be used on the flat to refer to cardinal orientations, or prototypical ‘uphill’ direction. This system then replaces our use of left/right in many contexts: when there are two objects oriented such that one is to the South of the other, it can be referred to as the ‘uphill’ object...Now, curiously, this system of North/South alignment is not complemented by a similar differentiation of the orthogonal.There is a named orthogonal...but the term is indifferent as to whether it refers to East or West; what it really means is ‘transverse to the incline.’ So there is a three-way distinction.(p. 596, 1992).An experimental paradigm: Lining up the animalsPederson et al. studied spatial reasoning cross-linguistically in several ways, all variations on a single procedural theme: The subjects memorize the positions of items in an array shown to them. The array is then removed. After a brief delay, the subjects are turned around (usually, 180 degrees) and asked to recall the original array so as to calculate a response. For example, in the variant we will use in the experiment presented below, three left-right symmetrical toy animals are lined up facing the same way on a table top (for a schematic depiction of the procedure, see Figure 1, adapted from Brown and Levinson, 1993b, Pederson et al., 1998). The subject memorizes this array and then, after a brief delay interval, is moved to another table. This second table is oriented 180 degrees from the original. The subject is now handed the three original animals in random order, and asked to position them in “the same way as before.”FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERECross-linguistic outcomes of these studies for Tenejapan and Dutch subject groups are graphically shown in Figure 2, adapted from Brown and Levinson, 1995. The Figure plots the distribution of absolute responses by subjects from the two languages.1 These results can be summarized as follows: The overwhelming majority of speakers of languages favoring absolute terms consistently rearranged the animals such that if they had on the first table been going north, they went north after rotation as well. Whereas speakers of languages favoring relative terms overwhelmingly often rearranged the animals such that if they had been going left on the first table, they went left after rotation as well. The difference is that what is north does not vary under rotation, while what is left certainly does.FIGURE 2 ABOUT HEREIt looks, then, as though a language distinction (absolute versus relative spatial terminology) is influencing reasoning in a very dramatic and straightforward way. However, it is possible that some third variable that differs between the subject populations is responsible both for the linguistic difference between them, and for the way they habitually go about solving spatial tasks. Specifically, each language population in the Brown et al. experiments was tested in its own community under the social and geographical frame-of-reference context that commonly obtain there. For example, the Tenejapan population was tested on its hill, out of doors, near a largish rectangular house. The Dutch population, presumably more used to a school-like situation, was tested indoors in a laboratory room. Reasonable enough. But this means that only part of the required experimentation were done, for two factors were varying at once – the language and the frame of reference in which the spatial task was to be solved. Which one caused the characteristically different behavior of these groups? To find out, it is necessary to determine whether a single linguistic group would change its reasoning style if the spatial-contextual conditions of experimentation were changed. We report on such a set of manipulations below. Because the results do reveal powerful effects of the conditions of test, we will end by suggesting nonlinguistic (or “non-Whorfian”) interpretations for them.II. Spatial reasoning in varying frames of reference: An experimental reviewSubjects for all the experiments that we now report were drawn from a single cultural and linguistic subgroup: monolingual native-English speaking undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania. The experimental question was whether we could induce Tenejapan-like and Dutch-like spatial reasoning behavior in this single population by appropriate changes of the spatial contexts in which they are tested. For comparability, each of the five experiments employed the line-up-the-animals task of Pederson et al., 1998.The rotation paradigm: Line up the animalsAs just noted, we adopted the ingenious method designed by the Pederson et al. group, here described in further detail. The materials and procedure are shown in Figures 1 and 3 (adapted from Pederson et al, 1998). As Figure 1 indicates, the subject was first seated on a swivel chair at a table (the “Stimulus table”) and asked to study an array of three toy animals (out of 5 animals in the total test-set of animals) that had been placed there in advance. Subjects were also asked to name each animal to assure that there was a consensual name for each. Because these were a toy dinosaur, lion, dog, rabbit, and elephant, there was no disagreement about the labels. Each toy was symmetrical along its longitudinal axis and was approximately 10 cm long. Both in practice and test trials, the experimenter always set up the animals so that their noses pointed in the same cardinal direction, either north or south, depending on the trial (equivalently, in the testing circumstances, either to the left or to the right). The subject was instructed to study the array for as long as he liked. Now the animals were scooped up by the experimenter. In an initial practice trial, the subjects were then handed the three animals and asked to set them up again (“make it the same”), again on the Stimulus Table (all of our subjects always did this correctly).Now the experiment proper began. The experimenter set up three of the animals on the Stimulus Table, as the subject watched. The subject studied this new array as long as he liked, followed by a 30-second delay. The subject was then swiveled on her chair 180 degrees to face the Recall Table, which was empty, and handed the three animals in random order. She was told to “make it the same.” This procedure was repeated (of course, changing the particular animals and their arrangement on each trial) with each subject five times. About 15% of the time subjects asked for clarification (of what we meant by “the same”). The experimenter blandly responded “Just make it the same” and, improbably enough, the subject then always said “OK” and carried out thetask.2FIGURE 3 ABOUT HEREAs schematized in Figure 3, there are two correct ways that subjects could reconstruct the array on the Recall Table: The left-hand column of animals is the relative solution; the right-hand column is the absolute solution. With vanishingly rare exceptions, each of our subjects always chose one of them and individual subjects were consistent across the five trials as to their style of solution. We now describe three frame-of-reference conditions under which (different) subject groups of monolingual English speakers were tested.Experiment 1: Landmarks in the reference world (Blinds-Up/Blinds-Down)This experiment, and those that follow, we altered the context in which subjects carried out the line-up-the-animals task by adding implicit landmark cues of various kinds. For after all, the results found for the Dutch and Tenejapan subjects of Pederson et al. might be attributable to the differential availability of such landmark information in a featureless laboratory room versus complex landscape.FIGURES 4 and 5 ABOUT HERESubjects, materials, and procedure: Twenty subjects participated, 10 in each of two landmark conditions. In both these conditions, subjects were tested in a laboratory room which was essentially featureless except for a floor-to-ceiling window at one side. As shown in Figure 5, the testing tables were set up in such a way as to be similar to the placement of the house that had been visible to Brown and Levinson’s Tenejapan subjects (Figure 4). One half of the subjects were tested in this room with the blinds pulled down, so that they could not see what lay behind the window. For the other 10 subjects, the blinds were in their raised position. Under this latter condition, the subjects if they looked toward the window would view the familiar sight of theuniversity library that lay across the street from the testing laboratory. No mention of the state of the blinds or of landmarks was made to any of the subjects.Results: The results are shown in Figure 6. The subjects in the Blinds-Down condition behaved much as the Dutch subjects in Brown and Levinson (see Figure 2 for comparison). The subjects in the Blinds-Up condition behaved differently, yielding a U-shaped distribution that lies somewhere between the prior Dutch and Tenejapan results. Even with the few subjects tested in each condition, the difference between Blinds-Up and Blinds-Down subjects approaches significance using the same evaluative instrument used in the prior studies by Brown and Levinson (Mann-Whitney U-test, p = .056).FIGURE 6 ABOUT HEREExperiment 2: Strengthening the landmark cues by going OutdoorsAlthough the experiment just presented in its Blinds-Up condition added a landmark cue analogous to the house that was visible to the Tenejapans, raising the blinds by no means reproduced the rich landmark conditions of an outdoor landscape. We therefore now performed an additional manipulation which was truer to what we can surmise about the Tenejapan testing conditions.Subjects, materials, and procedure: Ten new subjects, again undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania, were tested. We found an area of the Penn campus that roughly reproduced surface landmarks of the Tenejapan testing ground, though it was flattish rather than hilly. This was a large grassy area, with buildings and roads visible, as schematized in Figure 7. It being inconvenient to set out tables on this bumpy ground, we laid out large towels as substitute tables. And we used slightly larger animals so that they would be in reasonable scale to these towels. In all other regards, the experiment was just as in Experiment 1 (and just as in Brown andLevinson, 1993b).FIGURE 7 ABOUT HEREResults: The results of this manipulation are shown in Figure 8 (again, see Figure 1 for comparison).3 As inspection of the Figure shows, the subjects now evidenced a bias toward absolute responses, much like the Tenejapan subjects of Brown and Levinson and Pederson et al. To evaluate this finding statistically, we compared the effects for the Blinds-Down (or no landmark) condition against the present one. Again using the Mann-Whitney U-test, the difference between these conditions was highly reliable (p = .006). Notice, then, that the difference previously obtained by Brown and Levinson for Dutch versus Tenejapan speakers (Figure 1) is reproduced here between groups of Americans when they essentially have no landmarks (and thus act like Dutchmen) versus when they have strong landmark cues (and thus act like Tenejapans).FIGURE 8 ABOUT HEREExperiment 3: Controlled landmark cues (Absolute/Relative Ducks)In the experiment just described, we looked at the effects of ambient landmark cues in the visible world. And we found that these biased our subjects toward absolute interpretations of the spatial reasoning task, as compared to the relative bias of other subjects who were tested in the featureless (Blinds-Down) condition of Experiment 1. Yet we cannot say that the landmarks out of doors on the Penn campus matched those of the Tenejapan testing situation, or were greater or lesser in degree of richness or informativeness. Readers with an eye for detail, in fact, upon examining Figure 8 will have noticed that the Americans in the outdoor condition were not quite so absolute in their performances as the Tenejapans had been. Can landmark information, if it is salient enough, completely determine the degree to which a single population solves spatial problems from a body-oriented versus geography-oriented perspective? To find out, we now examined the effects ofmatched absolutely versus relatively placed landmarks.Subjects, materials, and procedure: Twenty subjects participated in this experiment, 10 in each of two conditions. Each of these subjects was tested in the original laboratory room where Experiment 1 had been conducted. Now the blinds were always up. As shown in Figure 9, a little toy stood on the Stimulus Table, to the right/south side of the subject him/her self. This toy was placed there before the subject entered the testing room, and it remained there, unmentioned and unmoved, for all 5 trials. As the Figure shows, it was a pair of kissing styrofoam ducks on a paper lake (i.e., a longitudinally symmetrical toy, approximately 17 cm long). As usual, the subjects’ task was to memorize the positions of the three line-up animals (as in Figure 1) placed on the Stimulus Table as before. No line-up animal was closer than 15 cm to the duck landmark. When subjects swiveled to the Recall table, they always saw an exact replica of the duck landmark to one side of it, placed there in advance. For half the subjects (the relative biasing, or Relative Ducks group), the replica was always on the right of the subject. For the other half (the absolute biasing, or Absolute Ducks group) the replica was always on the south of the Recall table.FIGURE 9 ABOUT HEREResults: The results of this manipulation are graphically shown in Figure 10. Now the results were exactly like those obtained for the Dutch (relative-responding) and Tenejapan (absolute-responding) subjects of Brown and Levinson, 1993b (compare Figure 10 and Figure 2). To evaluate this finding statistically, we again performed the Mann-Whitney U-test and found a highly reliable difference for the absolute-biasing and relative-biasing conditions of the present experiment (p = .003).FIGURE 10 ABOUT HEREIII. General discussionOur investigations were designed to provide further evidence relating to the Whorf-Sapir hypothesis, or rather to its descendant theorizing in the current literature of linguistic relativity. Our starting point was a series of particularly striking demonstrations from Brown and Levinson, 1993b and Pederson et al., 1998, of a correlation between cross-linguistic spatial-terminological differences and the manner of solving simple tasks of spatial reasoning by speakers of those languages (Figure 2). Their subjects whose everyday spatial terminology, for relatively small-scale arrays, was body-oriented solved the rotation problem relatively; whereas subjects whose terminology (at this grain) encoded cardinal direction solved the same problem absolutely. This work has been justly acclaimed for the enhanced perspective it is providing on language-culture relations. At minimum it stands as a welcome antidote to much familiar linguistic and psychological inquiry that assumes by default that all communities are about the same as, say, a community of Ivy League sophomores residing together in a Philadelphia dormitory. At the same time – and as this group of investigators has always been careful to emphasize – the findings are solely of a correlation between language and reasoning, and as such are hard to interpret causally.The manipulations we have described were all conducted with English speakers, to see if the absolute/relative spatial reasoning distinction could be reproduced within a single language community. If so, this would weaken or negate the claim that language differences, and the putative constraints these place on reasoning, were the underlying cause of the original effects. Moreover, we so designed the experiments as to expose an alternative explanation of the original results: Our subjects behaved absolutely or relatively depending on the presence and strength of the landmark cues made available to them. As landmark cues were strengthened in three steps: Blinds-Up (Experiment 1), to Outdoors (Experiment 2), and finally to Absolute Ducks (Experiment 3), theEnglish-speaking group responses moved progressively toward the Tenejapan absolute behavior, becoming completely equivalent to it under the Absolute Ducks condition. Contrastingly, in the absence of landmarks (Blinds Down, Experiment 1) or with relative-biasing landmarks (Relative Ducks, Experiment 3), the subjects behaved like Pederson et al.’s Dutch and Japanese subjects.When do creatures solve spatial problems “absolutely” versus “relatively”?The present results suggest that it is not the nature, even the learned nature, of an individual to solve spatial problems in the absolute versus relative way. Rather, individuals from the same linguistic-cultural population will solve the same spatial problem differently depending on the cues made available in the environment. This finding is not really a new one at all. Rather, it reproduces in detail the findings from prior lines of investigation of spatial reasoning by animals and young children.During the 1940's and 1950's, the question was asked whether animals are naturally “response learners” or “place learners” in regard to navigating through space to arrive at a goal (e.g., Tolman, Ritchie and Kalish, 1943). This issue, seen as a crucial one for understanding the nature of learning, was operationalized within experimental contexts that are formally analogous to the rotation task as designed by Pederson et al., and replicated in the present article.4 Typically, rats were trained to find food at one leg of a maze. Then either the rat or the training maze itself would be rotated 90 or 180 degrees. If the animal continued to turn in the trained direction on the maze even after rotation, he was judged to have learned only a response (say, “Turn left to get food”). If instead he responded to extralinguistic cues and thus made a different turn on the rotated trials, he was assumed to have learned something more sensible; namely, to turn toward the place where the reward was previously found (say, “Turn North to get food”). But in fact, neither characterization of rat learning was ever shown to be the correct one. As with the experiments we have just。

2024届湖北省襄阳市第四中学高三第一次适应性考试英语试题一、阅读理解With such a strong artistic heritage, it’s no surprise that England knocks it out of the park when it comes to world-class art galleries. These are the galleries you need to add to your must-visit list.Royal Academy of Arts (RA), LondonNot your standard gallery, the Royal Academy of Arts is led by artists to promote not just the appreciation of art, but its practice. It is world-famous for hosting some exhibitions that get everyone talking. Besides, what sets the RA apart is its engagement with the public through participatory experiences, allowing visitors to not only view art but become part of it in innovative ways.Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, NorwichSitting on the edge of the University of East Anglia’s campus, the Sainsbury Centre holds a collection of remarkable works of art spanning over 2,000 years. Inside the seminal Norman Foster building, you’ll find artworks from around the world, including some stunning pieces of European modern art by Degas, Francis Bacon, and Alberto Giacometti.Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West YorkshireTearing up the rulebook when it comes to how we traditionally view art, the Yorkshire Sculpture Park strives to break down barriers by showing works from British and international artists in the open air. Set in hundreds of acres of West Yorkshire parkland, you’ll see sculptures by some of the leading artists of the 20th century.Whitworth, ManchesterAfter a sky-high £15 million development, the Whitworth is becoming one of the premier galleries in the north of England. Making full use of its picturesque park setting, the gallery has a beautiful art garden and a sculpture terrace (露台), all waiting to be explored. Inside the gallery, you can view an exciting programme of ever-changing exhibitions.1.What is special about the Royal Academy of Arts?A.It offers interactive experiences.B.It displays works by senior artists.C.It occupies a vast space in the museum.D.It stages exhibitions in a traditional way.2.What do Yorkshire Sculpture Park and Whitworth have in common?A.They are small in scale.B.They offer outdoor settings.C.They feature long-standing works.D.They host exhibitions on an annual basis. 3.Where is the text probably taken from?A.An art textbook.B.An art student’s paper.C.A personal travel blog.D.A travel guidebook.As a mushroom scientist, you are vastly outnumbered, with estimates suggesting that there are between 2.2 million and 3.8 million species of fungi (真菌), the majority of which are yet to be identified. However, professionals in the field are not alone in their efforts to uncover new species. An enthusiastic community of amateurs has emerged, bridging the gap between professionals and non-professionals. These amateurs have even made significant discoveries. One such amateur is Taylor Lockwood, a 74-year-old mushroom enthusiast and professional photographer.In 1984, while living on the Mendocino coast of California, Taylor Lockwood developed a fascination with mushrooms. “Outside my cottage were these amazing mushrooms,” he says. “And it was as if these mushrooms looked at me and said, ‘Taylor, go out and tell the world how pretty we are.’” Lockwood answered their call and purchased camera equipment to capture their true nature. His passion for photographing mushrooms was so intense that he would even dig holes next to the mushrooms to get the perfect angle for his shots.In the Monongahela National Forest, Taylor Lockwood discovered an unusual mushroom that looked like tiny fingers wearing off-white gloves. Upon deeper investigation, fungi researcher Amy Rossman confirmed that it was a “hazel glove” mushroom, which is a rare find. “Mushrooms are not like plants,” Rossman says. “They don’t come up at the same time every year, and so sometimes it can be decades between when a fungus fruits.” Rossman says that’s why it’s so valuable to have people like Taylor Lockwood searching through the forest with a trained eye.A few years ago, Taylor Lockwood realized that still photos weren’t sufficient, so he choseto create time-lapse (延时拍摄的) videos of mushrooms. “When I do time-lapse, I see so much life happening around the mushrooms—insects, worms and other small creatures interacting with them,” he says. Lockwood’s love for art is evident in his approach to filming mushrooms over time. Although he appreciates the scientific aspect of his work, he identifies himself as an artist at heart.4.What can we learn about mushroom amateurs from paragraph 1?A.They keep close track of the growth of fungi.B.They help identify new species of mushroom.C.They replace professional scientists in the field.D.They classify the majority of mushroom species.5.What inspired Lockwood to photograph mushrooms?A.His desire for knowledge.B.His curiosity about nature.C.The beauty of nearby mushrooms.D.The appeal of outdoor photography.6.Which of the following best describes Lockwood according to paragraph 3?A.Skilled and observant.B.Focused and flexible.C.Talented and optimistic.D.Organized and responsible.7.Why did Lockwood decide to make time-lapse videos of mushrooms?A.To improve his photography techniques.B.To capture dynamic life in an artistic way.C.To collect biological data for deeper research.D.To use a new approach to scientific studies.California’s Water Resources Control Board recently approved new regulations in a unanimous (一致同意的) vote — toilet or shower wastewater will be recycled and pumped into the public drinking water system.In 2023, more than 97% of California has been in moderate to severe drought, while watersuppliers are struggling to keep up. A 2022 water supply and demand report indicated that around 18% of water suppliers were at risk of facing potential shortages. “The reality is that anyone out there on Mississippi River and on Colorado River, and anyone out there taking drinking water downstream is already drinking ‘toilet to tap’,” said Esquivel, a director of the Board.Early in the 1990s, the state was struggling to overcome the distaste its residents had toward drinking recycled water. Their efforts fizzled out when the phrase “toilet to tap” caught on and met with fierce resistance. The idea became too unpopular to be implemented. Despite the negative name, the regulations are the key to ensuring the supply of drinking water.California’s new regulations would let water agencies to treat wastewater, and then put it back into the drinking water system. It has taken officials more than 10 years to develop these regulations, a process that included several studies by independent groups of scientists. To put the scheme into effect and build huge water recycling plants, however, water agencies say they will need to prove to people that recycled water is not only safe to drink but also under monitoring.The new regulations require the wastewater be treated for all bacteria and viruses. In fact, the treatment is so intense that it removes all of the minerals that make fresh drinking water taste good. That means the minerals need to be added back at the end of the process. “What we have here are standards, science, and importantly monitoring that allow us to have safe pure water, and probably better in many instances,” said Esquivel. He added that it takes time and money to build these treatment centers. So, they will only be available for bigger cities at first.8.What is the purpose of paragraph 2?A.To highlight the current severe climate crisis in California.B.To describe the role of California’s new water regulations.C.To reveal the distribution of water resources in California.D.To show the urgency of water supply reform in California.9.What does the underlined phrase “fizzled out” in paragraph 3 mean?A.Failed.B.Worked.C.Stood out.D.Paid off. 10.What is critical for water agencies to conduct the recycling wastewater project?A.Policies from the government.B.The recognition by the public.C.Scientific research on wastewater.D.The construction of recycling plants. 11.What can be inferred from the last paragraph?A.The minerals will be preserved in the treatment.B.The treatment centers will be built in rural areas.C.The recycled water seems to be of better quality.D.Bacteria will be produced in the treating process.When we encounter a troublesome problem, we often gather a group to brainstorm. However, substantial evidence has shown that when we generate ideas together, we fail to maximize collective intelligence.To unearth the hidden potential in teams, we’re better off shifting to a process called “brainwriting”. You start by asking group members to write down what is going on in their brains separately. Next, you pool them and share them among the group without telling the authors. Then, each member evaluates them on his or her own, only after which do the team members come together to select and improve the most promising options. By developing and assessing ideas individually before choosing and expanding on them, the team can surface and advance possibilities that might not get attention otherwise.An example of great brainwriting was in 2010 when 33 miners were trapped underground in Chile. Given the urgency of the situation, the rescue team didn’t hold brainstorming sessions. Rather, they established a global brainwriting system to generate individual ideas. A 24-year-old engineer came up with a tiny plastic telephone. This specialized tool ended up becoming the only means of communicating with the miners, making it possible to save them.Research by organizational behavior scholar Anita Woolley and her colleagues helps to explain why this method works. They find that the key to collective intelligence is balanced participation. In brainstorming meetings, it’s too easy for participation to become one-sided in favor of the loudest voices. The brainwriting process ensures that all ideas are brought to the table and all voices are brought into conversation. The goal isn’t to be the smartest person in the room. It’s to make the room smarter.Collective intelligence begins with individual creativity, but it doesn’t end there. Individuals produce a greater volume and variety of novel ideas when they work alone. That means they not only come up with more brilliant ideas than groups but also more terrible ideas. Therefore, it takes collective judgment to find the signal in the noise and bring out the best ideas.12.What is special about brainwriting compared with brainstorming?A.It highlights independent work.B.It encourages group cooperation.C.It prioritizes quality over quantity.D.It prefers writing to oral exchanges. 13.Why does the author mention the Chile mining accident in paragraph 3?A.To introduce a tool developed during brainwriting.B.To praise a young man with brainwriting technique.C.To illustrate a successful application of brainwriting.D.To explain the role of brainwriting in communication.14.How does brainwriting promote collective intelligence according to paragraph 4?A.By blocking the loudest voices.B.By allowing equal involvement.C.By improving individual wisdom.D.By generating more creative ideas. 15.Which step of brainwriting does the author stress in the last paragraph?A.Individual writing.B.Group sharing.C.Personal evaluation.D.Joint discussion.Hop on the Silent Walking TrendSilent walking involves walking outdoors without distractions like music or conversations, focusing on the mind-body-nature connection. 16 That’s a slower, lower-impact way to relax and is great for fitness. Here’s everything you need to know about the trend.Select a natural setting and fully engage your senses. For reaping the mental health benefits, it is recommended to find a quiet and peaceful natural location. 17 Meanwhile, consciously observing the sights, sounds, smells, and physical sensations during the walk can significantly impact cognitive and emotional well-being.To stimulate the mind, consider exploring different routes than usual. Without your favourite podcast or playlist, you might slip into boredom on your walk. 18 And it might even be good for your brain. Scientists applaud the virtue s of boredom for brain health, believing that it boosts creativity and improves social connections. And if you do get bored, rest assured that it shows you’ve disconnected from external distractions. Go with it, and make sure you take a different route each time — it’ll keep you motivated.Start off with five-minute silent walks and eventually build up to thirty minutes. If you’reusually a headphone wearer, it will feel super weird to walk without your go-to tunes, but give yourself a second to adjust. Chances are, once you’re a few minutes into your silent walk, you’ll feel the magic kick in. 19Regular reflection and ongoing documentation are essential. After completing a silent walk, take time to reflect upon any emerging thoughts, feelings, or insights. 20 Journaling about the experience can also solidify connections between thoughts and ideas, providing a valuable tool for self-reflection and growth.A.But being bored won’t hurt you.B.Taking different paths can lead to exciting discoveries.C.However, you’ll start noticing the urban landscape around you.D.Adjusting the routine gradually can help ease into the experience.E.They can deepen understanding and serve as a record of personal growth.F.Unlike exercise-oriented walking, it isn’t about reaching certain speed or steps.G.In such an environment, you can immerse yourself in the natural soundscape (音景).二、完形填空My little niece was wandering through the garden in her home. Her father collected rare and precious plants, which he 21 with great care.My niece was 22 by a plant full of blooming flowers. She approached it and admired its unique beauty. Suddenly she 23 that the plant was in a pile of filth(污秽). She could not put up with the 24 of dirt with such fantastic flowers.She figured out a plan to clean the plant. She 25 the plant with all her might from the dirt and washed its 26 in running tap water till all traces of dirt were washed away. She then placed the plant on a clean stone and went away, proud that she had done a great 27 .Later her father came to the garden and noticed the uprooted plant, which had lain 28 in the baking sun. His little daughter ran over to 29 her achievement. “I have cleaned it, Daddy,” she reported 30 .The father showed her how her treatment had nearly killed the plant and told her that thefilthy soil provided the best 31 to grow that plant. On hearing that, the girl felt guilty that the plant had suffered by her cleaning.A great gardener mixes the 32 soil for each plant. 33 , God provides each of us with the best 34 required for optimum (最佳) spiritual growth. But it may appear to be 35 and we may even complain to God about our difficulty.21.A.attended to B.brought up C.looked out D.fed on 22.A.caught B.attacked C.attracted D.shocked 23.A.recalled B.recognized C.noticed D.concluded 24.A.shortage B.presence C.presentation D.composition 25.A.pulled B.picked C.held D.pushed 26.A.flowers B.roots C.leaves D.branches 27.A.project B.deal C.operation D.deed 28.A.boiling B.bathing C.breathing D.dying 29.A.confirm B.check C.exhibit D.assess 30.A.happily B.coldly C.fearfully D.patiently 31.A.shelter B.medicine C.agency D.medium 32.A.same B.right C.dirty D.loose 33.A.Moreover B.Similarly C.Rather D.Nevertheless 34.A.environment B.style C.neighborhood D.opportunity 35.A.invisible B.disorganized C.improper D.unpleasant三、语法填空阅读下面短文,在空白处填入1个适当的单词或括号内单词的正确形式。

雅思小作文回形针作文The humble paperclip, a tiny yet indispensable office staple, embodies the essence of simplicity and versatility. Its slender form, typically crafted from steel wire bent into a loop with two prongs, serves as a testament to the ingenuity of design.In the bustling world of paperwork and digital documents, the paperclip continues to hold its ground, symbolizing the enduring bond between physical and digital realms. Its primary function, securely attaching sheets of paper together, remains as relevant today as it was decades ago. Yet, its use transcends mere paperwork, extending to creative endeavors like organizing notes, marking pages, or even serving as a makeshift bookmark.The paperclip's adaptability is remarkable. From the mundane task of clipping receipts to the imaginative role it plays in art installations and DIY projects, it demonstrates the power of a simple idea to inspire endless possibilities. Its ubiquitous presence underscores the value of minimalism and resourcefulness in our lives.Moreover, the paperclip serves as a metaphor for resilience. Despite its fragile appearance, it withstandsthe weight of multiple sheets, persevering through thedaily grind of office life. It reminds us that even the smallest objects can play a significant role and that true strength often lies in simplicity and functionality.In conclusion, the paperclip, with its timeless design and myriad uses, stands as a testament to the beauty of simplicity and the power of ingenuity. It continues to be a cherished companion in our daily endeavors, connecting ideas, documents, and ultimately, people.。