翻译-the turns of translation studies

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:395.50 KB

- 文档页数:77

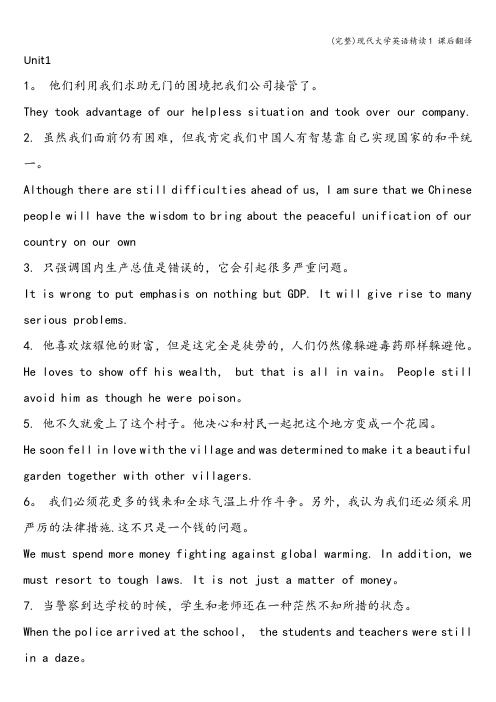

Unit11。

他们利用我们求助无门的困境把我们公司接管了。

They took advantage of our helpless situation and took over our company.2. 虽然我们面前仍有困难,但我肯定我们中国人有智慧靠自己实现国家的和平统一。

Although there are still difficulties ahead of us, I am sure that we Chinese people will have the wisdom to bring about the peaceful unification of our country on our own3. 只强调国内生产总值是错误的,它会引起很多严重问题。

It is wrong to put emphasis on nothing but GDP. It will give rise to many serious problems.4. 他喜欢炫耀他的财富,但是这完全是徒劳的,人们仍然像躲避毒药那样躲避他。

He loves to show off his wealth, but that is all in vain。

People still avoid him as though he were poison。

5. 他不久就爱上了这个村子。

他决心和村民一起把这个地方变成一个花园。

He soon fell in love with the village and was determined to make it a beautiful garden together with other villagers.6。

我们必须花更多的钱来和全球气温上升作斗争。

另外,我认为我们还必须采用严厉的法律措施.这不只是一个钱的问题。

We must spend more money fighting against global warming. In addition, we must resort to tough laws. It is not just a matter of money。

翻译方式的变化英语作文Title: Evolution of Translation Methods。

Translation, as a bridge between different languages and cultures, has undergone significant changes over time. From traditional manual methods to modern technological advancements, the evolution of translation techniques has greatly influenced the way information is conveyed across languages. In this essay, we will explore the historical progression and contemporary innovations in translation methods.Historically, translation was primarily carried out manually by linguists proficient in both the source and target languages. This traditional method involved a deep understanding of the nuances and cultural contexts of both languages to ensure accurate and meaningful translations. Translators relied heavily on dictionaries, glossaries, and their own linguistic expertise to convey the original message faithfully.However, with the advancement of technology,particularly with the advent of computers and the internet, translation methods began to undergo a profound transformation. One significant development was the introduction of machine translation (MT) systems. Initially, early MT systems such as rule-based and statistical machine translation were limited in their capabilities and often produced inaccurate or awkward translations. These systems operated based on predefined rules or statistical models derived from large bilingual corpora.The breakthrough came with the rise of neural machine translation (NMT), which revolutionized the field of translation. NMT employs artificial neural networks to process and translate text, mimicking the human brain's ability to understand and generate language. Unlikeprevious MT systems, NMT models can capture complexlinguistic patterns and contextual nuances, resulting in more fluent and natural-sounding translations. The effectiveness of NMT has significantly narrowed the gap between human and machine translation quality.Moreover, the proliferation of online translation platforms and tools has democratized the translation process, making it more accessible to individuals and businesses worldwide. These platforms leverage the power of crowdsourcing, allowing users to contribute translations collaboratively. Websites and applications such as Google Translate, Microsoft Translator, and DeepL have become indispensable tools for instant translation of text, websites, and documents across multiple languages.Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing (NLP) technologies has enabled the development of innovative translation solutions. AI-driven translation models can learn from vast amounts of bilingual data and continuously improve their performance through iterative training. These models can adapt to various domains and languages, making them versatile and scalable for diverse translation tasks.In addition to machine translation, another emerging trend in translation methods is the use of computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools. CAT tools enhance the efficiency and accuracy of human translators by providing features such as terminology management, translation memory, and quality assurance checks. These tools enabletranslators to streamline the translation process, maintain consistency, and handle large volumes of text more effectively.Despite the advancements in machine translation technology, human translators remain indispensable for handling complex or specialized content that requires cultural sensitivity and creative interpretation. While machines excel at processing large volumes of text quickly, they may struggle with idiomatic expressions, ambiguous meanings, or context-specific nuances that require human insight.In conclusion, the evolution of translation methodsfrom manual to technological approaches has transformed the way languages are translated and understood. Whiletraditional methods relied on human expertise, modern advancements in machine translation and AI have ushered ina new era of efficiency and accessibility in translation. As technology continues to advance, the boundaries between human and machine translation are becoming increasingly blurred, leading to new possibilities and challenges in cross-linguistic communication.。

翻译美学视角下的《秘密花园》两汉译本比较研究摘要《秘密花园》是20世纪美国女作家弗朗西斯﹒霍其森﹒伯内特的代表作。

它不仅是一部经典儿童著作,还具有极高的美学价值。

自1911年在美国首次出版以来,就引起国内外学者的热切关注。

迄今为止,已有许多汉语译本出版。

尽管国内外学者对《秘密花园》的研究已取得了一些成果,但对其翻译的深入﹑系统的研究却并不多见。

而从翻译美学的角度对这部作品译作的研究则更是寥寥无几。

鉴于此,本文以李文俊先生和张润芳女士的译本为基础,尝试从翻译美学的新视角对这部经典儿童著作进行一个全面﹑系统的研究。

这部小说有着浓郁的审美价值,笔者认为在这方面大有深入挖掘的空间。

本文主要依据傅仲选先生和刘宓庆先生的翻译美学理论,将其应用于《秘密花园》的原作及两汉语译本文本分析。

笔者依据这部小说中体现的美学特色,从翻译美学所涉及的形式系统美学成分(内在美学成分)和非形式系统的美学成分(外在美学成分)两个方面探讨了《秘密花园》两汉译本中美学意蕴的审美再现。

其中内在美学成分的探讨主要从语音,词汇和句法三个层次,外在美学成分的分析主要从意象和文化两个层次。

本文以充分的实例分析论证翻译美学在儿童文学翻译中的有效阐释力,比较了两个译本的得失。

并且从翻译美学的角度对翻译美学的两大审美主体—译者和译本读者进行了比较分析和探讨。

通过对《秘密花园》原作和译本的美学价值的系统对比分析,发现总体而言,两译本都较好地再现了原文的美学元素,不过李文俊先生的译本在这方面要稍胜一筹。

当然,两个译本都还存在完善的空间。

本文为《秘密花园》译作的研究提供了一个新视角。

并且通过将美学理论应用于翻译理论和实践的研究,也证明了翻译美学是一门能够用来评判翻译作品美学价值,操作性较强的理论。

翻译美学的理论不仅能够指导翻译实践,还能成为评判译作好坏的美学标准,对于翻译批评和翻译实践都有着极大的帮助。

翻译中许多美学问题都和审美标准有着一定的联系,了解这些审美标准有助于指导翻译实践,欣赏美学元素,并对译作做出美学评判。

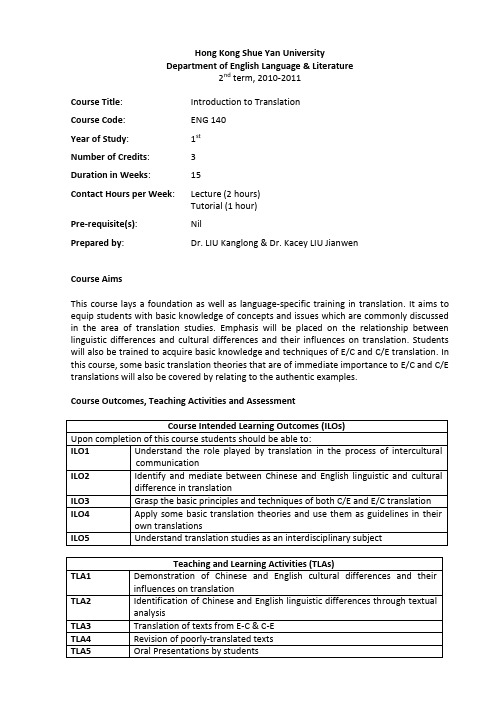

Hong Kong Shue Yan UniversityDepartment of English Language & Literature2nd term, 2010-2011Course Title: Introduction to TranslationCourse Code: ENG 140Year of Study: 1stNumber of Credits: 3Duration in Weeks: 15Contact Hours per Week: Lecture (2 hours)Tutorial (1 hour)Pre-requisite(s): NilPrepared by: Dr. LIU Kanglong & Dr. Kacey LIU JianwenCourse AimsThis course lays a foundation as well as language-specific training in translation. It aims to equip students with basic knowledge of concepts and issues which are commonly discussed in the area of translation studies. Emphasis will be placed on the relationship between linguistic differences and cultural differences and their influences on translation. Students will also be trained to acquire basic knowledge and techniques of E/C and C/E translation. In this course, some basic translation theories that are of immediate importance to E/C and C/E translations will also be covered by relating to the authentic examples.Course Outcomes, Teaching Activities and AssessmentCourse OutlineWeek 1●Introduction1.Course outline2.Nature of translation3.Types of translation4.What is translation studies?5.Reference toolsReadingsBaker, M. (2000) In Other Words: A Coursebook on Translation, Beijing : Foreign Language and Research Press, 1-9.Munday, Jeremy (2008) Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications 2nd edition, London and New York: Routledge, 4-9.Week 2●Language difference between Chinese and English & Translation (I)1.Translation on word level2.Translation on sentence levelReadingsBaker, M. (2000) In Other Words: A Coursebook on Translation, Beijing: Foreign Language and Research Press, 10-44; 82-118; 110-111張春柏。

北外考博辅导班:2019北外高级翻译学院考博难度解析及经验分享北京外国语大学(以下简称“北外”)是首批双一流学科建设高校。

其前身是1941年成立于延安的抗日军政大学三分校俄文大队,距今已有77年办学历史,是我国办学历史最悠久、规模最大、开设语种最多的外国语大学。

经过几十年的创业与奋斗、几代人的不懈努力,北外目前已发展成为一所多语种、多学科、多层次,以培养高质量、创新型一流外语人才及外语类复合型优秀拔尖人才为目标的国际一流外国语大学。

下面是启道考博辅导班整理的关于北京外国语大学高级翻译学院考博相关内容。

一、院系简介北京外国语大学高级翻译学院成立于1994年,其前身为1979年设立的联合国译员训练班(部),截至2016年,已为联合国系统和国内机构共培养了1500余名专业翻译人才。

学院现有专职教师29人(其中教授3人、副教授4人、讲师18人),校内兼职教授3人,校外客座教授2人。

绝大多数专职教师都在联合国纽约总部、日内瓦欧洲总部、联合国教科文组织、国际劳工组织和世界卫生组织等机构从事过口笔译翻译工作,为国内外举办的各种国际会议提供会议翻译服务,具备丰富的翻译实践经验。

学院每年招收硕士学位研究生,学制2-3年,包括学术硕士和专业硕士两个类型。

学硕分为口译理论与实践和翻译与跨文化研究两个方向,学制3年。

专硕为英语口译,下设英汉同声传译(3年)、英汉口笔译(2年)、英汉会议口译(2年)、英汉复语口译(3年)方向。

学院还与中国外语教育研究中心合作招收翻译研究和语言学方向的博士研究生。

学院在读研究生(包括留学生)稳定在200余人。

学生在读期间有机会到国际组织和专业翻译机构实习,毕业后的就业去向主要是国家各部委、省市外办、跨国公司、大型国企、国有银行和高校等。

北外高翻在翻译人才培养方面具有优良传统,取得了卓越成绩,在社会上享有广泛的声誉。

学院同联合国机构和其他国际组织保持密切关系,多次为联合国组织承办中文翻译人员考试,为WTO-中国项目举办翻译培训班,定期邀请联合国各机构翻译负责人和译员来院举办讲座,每年组织在校生赴国际劳工组织、世界卫生组织、联合国总部担任实习译员,2001年以来已有40余人通过联合国口笔译考试,为联合国贡献近半数新增译员。

Jürgen Habermas (1968)The Idea of the Theory of Knowledge as SocialTheoryfrom Knowledge and Human Interests bySource:Knowledge & Human Interest, 1968, publ. Polity Press, 1987.Chapter Three: The Idea of the Theory of Knowledge as Social Theoryreproduced here.The interpretive scheme set forth by Marx for the Phenomenology of Mind contains the program for an instrumentalist translation of Hegel's philosophy of absolute reflection:The greatness of Hegel's phenomenology and its end result-the dialectic ofnegativity as motive and productive principle-is thus ... that Hegel graspsthe self-generation of man as a process, objectification as de-objectification,as alienation and the overcoming of this alienation; in other words, that hegrasps the essence of labour and comprehends objective man, who is trueman because of his reality, as the result of his own labour. [Marx, Critiqueof Hegel's Philosophy in General]The idea of self-constitution of the species through labour is to serve as the guide to appropriating the Phenomenology while demythologising it. As we have shown, the assumptions of the identity kept Hegel from reaping the real harvest of Kant, and they dissolve on this materialist basis. Ironically, however, the very viewpoint from which Marx correctly criticises Hegel keeps him from adequately comprehending his own studies. By turning the construction of the manifestation of consciousness into an encoded representation of the self-production of the species, Marx discloses the mechanism of progress in the experience of reflection, a mechanism that was concealed in Hegel's philosophy. It is the development of the forces of production that provides theimpetus to abolishing and surpassing a form of life that has been rigidified in positivity and become an abstraction. But at the same time, Marx deludes himself about the nature of reflection when he reduces it to labour. identifies "transformative abolition (Aufheben), as objective movement which reabsorbs externalisation," with the appropriation of essential powers that have been externalised in working on material.Marx reduces the process of reflection to the level of instrumental action. By reducing the self-positing of the absolute ego to the more tangible productive activity of the species, be eliminates reflection as such as a motive force of history, even though be retains the framework of the philosophy of reflection. His re-interpretation of Hegel's Phenomenology betrays the paradoxical consequences of taking Fichte's philosophy of the ego and undermining it with materialism. Here the appropriating subject confronts in the non-ego not lust a product of the ego but rather some portion of the contingency of nature. In this case the act of appropriation is no longer identical with the reflective re-integration of some previously externalised part of the subject itself. Marx preserves the relation of the subject's prior positing activity (which was not transparent to itself), that is of hypostatisation, to the process of becoming conscious of what has been objectified, that is of reflection. But, on the premises of a philosophy of labour, this relation turns into the relation of production and appropriation, of externalisation and the appropriation of externalised essential powers. Marx conceives of reflection according to the model of production. Because he tacitly starts with this premise, it is not inconsistent that he does not distinguish between the logical status of the natural sciences and of critique.In fact, Marx does not completely obliterate the distinction between the natural sciences and the sciences of man. The outlines of an instrumentalist epistemology enable him to have a transcendental-pragmatistic conception of the natural sciences. They represent a methodically guaranteed form of the kind of knowledge which, on a pre-scientific level, is accumulated in the system of social labour. In experiments, assumptions about the law-like connection of events are tested in a manner fundamentally identical with that of "Industry," that is of pre-scientific situations of feedback-controlled action.In both cases, the transcendental viewpoint of possible technical control, subject to which experience is organised and reality objectified, is the same. With regard to the epistemological justification of the natural sciences, Marx stands with Kant against Hegel, although he does not identify them with knowledge as such. For Marx as for Kant the criterion of what makes science scientific is methodically guaranteed cognitive progress. Yet Marx did not simply assume this progress as evident. Instead, he measured it in relation to the degree to which natural-scientific information, regarded as in essence technically exploitable knowledge, enters the process of production:The natural sciences have developed an enormous activity and appropriatedan ever growing body of material. Philosophy has remained just as foreignto them as they remained foreign to philosophy. Their momentary union[criticising Schelling and Hegel] was only a fantastic illusion ... In a muchmore practical fashion, natural science has intervened in human life andtransformed it by means of industry ... Industry is the real historical relationof nature, and thus of natural science, to man. [Marx, Private Property &Communism,]On the other hand, Marx never explicitly discussed the specific meaning of a science of man elaborated as a critique of ideology and distinct from the instrumentalist meaning of natural science. Although he himself established the science of man in the form of critique and not as a natural science, be continually tended to classify it with the natural sciences. He considered unnecessary an epistemological justification of social theory. This shows that the idea of the self-constitution of mankind through labour sufficed to criticise Hegel but was inadequate to render comprehensible the real significance of the materialist appropriation of Hegel.Invoking the model of physics, Marx claims to represent "the economic law of motion of modern society" as a "natural law." In the Afterword to the second edition of Capital, Volume I he quotes with approval the methodological evaluation of a Russian reviewer. While the latter goes along with Comte ill emphasising the difference between economics and biology on the one hand and physics and chemistry on the other, and calls attention in particular to the restriction of the validity of economic laws to specifichistorical periods, he nevertheless equates this social theory with the natural sciences. Marx has only one concern,to demonstrate through precise scientific investigation the necessity ofdefinite orders of social relations and to register as irreproachably aspossible the facts that serve him as points of departure and confirmation . . .Marx considers the movement of society as a process of natural history,governed by laws that are not only independent of the will, consciousness,and intention of men but instead, and conversely, determine their will,consciousness, and intentions.In order to prove the scientific character of his analysis, Marx repeatedly made use of its analogy to the natural sciences. He I never gives evidence of having revised his early intention, according to which the science of man was to form a unity with the natural sciences:Natural science will eventually subsume the science of man just as thescience of man will subsume natural science: there will be a single science.[Marx, Private Property & Communism]This demand for a natural science of man, with its positivist overtones, is astonishing. For the natural sciences are subject to the transcendental conditions of the system of social labour, whose structural change is supposed to be what the critique of political economy, as the science of man, reflects on. Science in the rigorous sense lacks precisely this element of reflection that characterises a critique investigating the natural-historical process of the self-generation of the social subject and also making the subject conscious of this process. To the extent that the science of man is an analysis of a constitutive process, it necessarily includes the self-reflection of science as epistemological critique. This is obliterated by the self-understanding of economics as a "human natural science." As mentioned, this abbreviated methodological self-understanding is nevertheless a logical consequence of a frame of reference restricted to instrumental action.If we take as our basis the materialist concept of synthesis through social labour, then both the technically exploitable knowledge of the natural sciences, the knowledge of natural laws, as well as the theory of society, the knowledge of laws of human natural history, belong to the same objective context of theself-constitution of the species. From the level of pragmatic, everyday knowledge to modern natural science, the knowledge of nature derives from man's primary coming to grips with nature; at the same time it reacts back upon the system of social labour and stimulates its development. The knowledge of society can be viewed analogously. Extending from the level of the pragmatic self-understanding of social groups to actual social theory, it defines the self-consciousness of societal subjects. Their identity is reformed at each stage of development of the productive forces and is in turn a condition for steering the process of production:The development of fixed capital indicates the extent to which generalsocial knowledge has become an immediate force of production, andtherefore [!] the conditions of the social life process itself have come underthe control of the general intellect. [Grundrisse p594]So far as production establishes the only framework in which the genesis and function of knowledge can be interpreted, the science of man also appears under categories of knowledge for control. At the level of the self-consciousness of social subjects, knowledge that makes possible the control of natural processes turns into knowledge that makes possible the control of the social life process. In the dimension of labour as a process of production and appropriation, reflective knowledge changes into productive knowledge. Natural knowledge congealed in technologies impels the social subject to an ever more thorough knowledge of its "Process of material exchange" with nature. In the end this knowledge is transformed into the steering of social processes in a manner not unlike that in which natural science becomes the power of technical control.In the preliminary studies for the Critique of Political Economy there is a model according to which the history of the species is linked to an automatic transposition of natural science and technology into a self-consciousness of the social subject (general intellect)-a consciousness that controls the material life process. According to this construction the history of transcendental consciousness would be no more than the residue of the history of technology. The latter is left exclusively to the cumulative evolution of feedback-controlled action and follows the tendency to augment the productivity oflabour and to replace human labour power-"the realisation of this tendency is the transformation of the means of labour into machinery." The epochal turning-points in the evolution of technology show how all capacities of the human organism combined in the behavioural system of instrumental action are gradually transferred to the means of labour: First the capacities of the executing organs, then those of the sense organs, the energy production of the human organism, and finally the capacities of the controlling organ, the brain. The stages of technical progress can in principle be foreseen. In the end the entire labour process will have separated itself from man and reside only in the means of labour.The self-generative act of the human species is complete as soon as the social subject has emancipated itself from necessary labour and, so to speak, takes its place alongside scientised production. At that point labour time and the quantity of labour expended also become obsolete as a measure of the value of goods produced. The spell of materialism cast upon the process of humanisation by the shortage of available means and the compulsion to labour will be broken. The social subject (as ego) will have permeated and appropriated the nature objectified through labour (the non-ego), as much as is conceivable under the conditions of production (the activity of the "absolute ego"). Along with the materialist interpretation of his theory of knowledge, Fichte's thought has been translated into a Saint-Simonian perspective. An unusual passage from the Grundrisse der Kritik der Politischen Okonomie, which does not recur in the parallel investigations in Capital, fits into this framework:To the degree ... that large-scale industry develops, the creation of socialwealth depends less on labour time and the quantity of labour expended thanon the power of the instruments that are set in motion during labour timeand which themselves in turn-their powerful effectiveness-themselves inturn are in no proportion to the immediate labour time that their productioncosts. Rather they depend on the general level of science and technologicalprogress, or the application of science to production. (The development ofthis science, especially natural science, and all others along with it, is itselfin turn proportional to the development of material production.) Forexample, agriculture becomes the mere application of the science ofmaterial exchange as it is to be regulated most advantageously for the entiresocial body. Real wealth manifests itself rather-and large industry revealsthis-in the tremendous disproportion between the labour time expended andits product just as in the qualitative disproportion between labour that badbeen reduced to a pure abstraction and the power of the productive processthat it oversees. As man relates to the process of production as overseer andregulator, labour no longer seems so much to be enclosed within the processof production. (What holds for machinery holds just as well for thecombination of human activities and the development of human intercourse.)The labourer no longer inserts a modified natural object between the objectand himself. Instead he inserts the natural process that he has transformedinto an industrial one as a medium between himself and inorganic nature, ofwhich he takes command. He takes his place alongside the process ofproduction instead of being its chief agent. In this transformation whatappears as the keystone of production and wealth is neither the immediatelabour performed by man himself nor the time he labours but theappropriation of his own general productive force, his understanding ofnature and its mastery through his societal existence-in a word, thedevelopment of the social individual....Therewith production based on exchange value collapses, and theimmediate material process of production sheds the form of scantiness andantagonism. The free development of individualities and therefore not thereduction of necessary labour time in order to create surplus labour, butrather the reduction of society's necessary labour to a minimum, which thenhas its counterpart in the artistic, scientific, and other education ofindividuals through the time that has become free for all of them andthrough the means that have been created. [Grundrisse p 592]Here it is from the methodological perspective that we are interested in this conception of the transformation of the labour process into a scientific process that would bring man's "material exchange" with nature under the control of a human species totally emancipated from necessary labour. A science of man developed from this point of view would have to construct the history of the species as a synthesis through social labour and only through labour. It would make true the fiction of the early Marx that natural science subsumes the science of man just as much as the latter subsumes the former. For, on the one hand, the scientisation of production is seen as the movement that brings about the identity of a subject that knows the social life process and then also steers it. In this sense the science of man would be subsumed under natural science. On the other hand, the natural sciences are comprehended in virtue of their function in the self-generative process of the species as the exoteric disclosure of man's essential powers. In this sense, natural science would be subsumedunder the science of man. The latter contains principles from which a methodology of the natural sciences resembling a transcendental-logically determined pragmatism could be derived. But this science does not question its own epistemological foundations. It understands itself in analogy to the natural sciences as productive knowledge. It thus conceals the dimension of self-reflection in which it must move regardless.Now the argument which we have taken up was not pursued beyond the stage of the "rough sketch" of Capital. It is typical only of the philosophical foundation of Marx's critique of Hegel, that is production as the "activity" of a self-constituting species. It is not typical of the actual social theory in which Marx materialistically appropriates Hegel on a broad scale. Even in the Grundrisse we find already the official view that the transformation of science into machinery does not by any means lead of itself to the liberation of a self-conscious general subject that masters the process of production. According to this other version the self-constitution of the species takes place not only in the context of men's instrumental action upon nature but simultaneously in the dimension of power relations that regulate men's interaction among themselves. Marx very precisely distinguishes the self-conscious control of the-social life process by the combined producers from an automatic regulation of the process of production that has become independent of these individuals. In the former case the workers relate to each other as combining with each other of their own accord. In the latter they are merely combined,so that the aggregate labour as a totality is not the work of the individualworker, and is the work of the various workers together only insofar as theyare combined and not insofar as they relate to each other as combining oftheir own accord. [Grundrisse p 374]Taken by itself, scientific-technical progress does not yet lead to a reflexive comprehension of the traditional, "natural" operation of the social life process in such a way that self-conscious control could result:In its combination this labour [of scientised production] appears just asmuch in the service of an alien will and an alien intelligence, which directsit. It has its psychic unity outside itself and its material unity subordinated tothe unity of machinery, of fixed capital, which is grounded in the object.Fixed capital, as an animated monster, objectives scientific thought and is infact the encompassing aspect. It does not relate to the individual worker asan instrument. Instead he exists as an animated individual detail, a livingisolated accessory to the machinery. [Grundrisse p 374]The institutional framework that resists a new stage of reflection (which, it is true, is prompted by the progress of science established as productive force) is not immediately the result of a life that has been rigidified to the point of abstraction: in Hegel's phenomenological language, a form of the manifestation of consciousness. What this represents is not immediately a stage of technological development but rather a relation of social force, namely the power of one social class over another. The relation of force usually appears in political form. In contrast, the distinctive feature of capitalism is that the class relation is economically defined through the free labour contract as a form of civil law. As long as this mode of production exists, the most progressive scientisation of production could not lead to the emancipation of a self-conscious subject that knows and regulates the social life process. Of necessity it would only sharpen the "litigant contradiction" of that mode of production:On the one hand it [capital] thus calls to life all the powers of science and ofnature as of social combination and social intercourse, to make the creationof wealth (relatively) independent of the labour time expended on it. On theother, it wants to take the gigantic social forces generated in this way andmeasure them against labour time and confine them within the boundsrequired in order to preserve as value the value already created. [Grundrissep 593]The two versions that we have examined make visible an indecision that has its foundation in Marx's theoretical approach itself. For the analysis of the development of economic formations of society he adopts a concept of the system of social labour that contains more elements than are admitted to in the idea of a species that produces itself through social labour. Self-constitution through social labour is conceived at the categorical level as a process of production, and instrumental action, labour in the sense of material activity, or work designates the dimension in which natural history moves. At the level of his material investigations, on the other hand, Marx always takes account of social practice that encompasses both work and interaction. The processes of natural history are mediated by the productive activity of individuals and theorganisation of their interrelations. These relations are subject to norms that decide, with the force of institutions, how responsibilities and rewards, obligations and charges to the social budget are distributed among members. The medium in which these relations of subjects and of groups are normatively regulated is cultural tradition. It forms the linguistic communication structure on the basis of which subjects interpret both nature and themselves in their environment.While instrumental action corresponds to the constraint of external nature and the level of the forces of production determines the extent of technical control over natural forces, communicative action stands in correspondence to the suppression of man's own nature. The institutional framework determines the extent of repression by the unreflected, "natural" force of social dependence and political power, which is rooted in prior history and tradition.A society owes emancipation from the external forces of nature to labour processes, that is to the production of technically exploitable knowledge (including "the transformation ,of the natural sciences into machinery"). Emancipation from the compulsion of internal nature succeeds to the degree that institutions based on force are replaced by an organisation of social relations that is bound only to communication free from domination. This does not occur directly through productive activity, but rather through the revolutionary activity of struggling classes (including the critical activity of reflective sciences). Taken together, both categories of social practice make possible what Marx, interpreting Hegel, calls the self-generative act of the species. He sees their connection effected in the system of social labour. That is why "production" seems to him the movement in which instrumental action and the institutional framework, or "Productive activity" and "relations of production," appear merely as different aspects of the same process.However, if the institutional framework does not subject all members of society to the same repressions, then the tacit expansion of the frame of reference to include in social practice both work and interaction must necessarily acquire decisive importance for the construction of the history of the species and the question of its epistemological foundation. If production attains the level of producing goods over and above elementary needs, theproblem arises of distributing the surplus product created by labour. This problem is solved by the formation of social classes, which participate to varying degrees in the burdens of production and in social rewards. With the cleavage of the social system into classes that are made permanent by the institutional framework, the social subject loses its unity: "To regard society as one single subject is, moreover, to regard it falsely-speculatively."As long as we regard the self-constitution of the species through labour only with respect to the power of control over natural processes that accumulates in the forces of production, it is meaningful to speak of the social system in general and to speak of the social subject in the singular. For the level of development of the forces of production determines the system of social labour as a whole. In principle the members of a society all live at the same level of mastery of nature, which in each case is given with the available technical knowledge. So far as the identity of a society takes form via this level of scientific-technical progress, it is the self-consciousness of "the" social subject. But as we now see, the self-formative process of the species does not coincide with the genesis of this subject of scientific-technical progress. Rather, this "self-generative act," which Marx comprehended as a materialistic activity is accompanied by a self-formative process mediated by the interaction of class subjects either under compulsory integration or in open rivalry.While the constitution of the species in the dimension of labour appears linearly as a process of production and the growth of complexity, in the dimension of the struggle of social classes it takes place as a process of oppression and self-emancipation. In both dimensions each new stage of development is characterised by a supersession of constraint: through emancipation from external natural constraint in one and from repressions of internal nature in the other. The course of scientific-technical progress is marked by the epochal innovations through which functional elements of the behavioural system of .instrumental action are reproduced step by step at the level of machines. The limiting value of this development is thus defined: the organisation of society itself as an automaton. The course of the social self-formative process, on the other hand, is marked not by new technologies butby stages of reflection through which the dogmatic character of surpassed forms of domination and ideologies are dispelled, the pressure of the institutional framework is sublimated, and communicative action is set free as communicative action. The goal of this development is thereby anticipated: the, organisation of society linked to decision-making processes on the basis of discussion free from domination. Raising the productivity of technically exploitable knowledge, which in the sphere of socially necessary labour leads to the complete substitution of machinery for men, has its counterpart here in the self-reflection of consciousness in its manifestations to the point where the self-consciousness of the species has attained the level of critique and freed itself from all ideological delusion. The two developments do not converge. Yet they are interdependent; Marx tried in vain to capture this in the dialectic of forces of production and relations of production. In vain-for the meaning of this "dialectic" must remain unclarified as long as the materialist concept of the synthesis of man and nature is restricted to the categorical framework of production.If the idea of the self-constitution of the human species in natural history is to combine both self-generation through productive activity and self-formation through critical-revolutionary activity, then the concept of synthesis must also incorporate a second dimension. The ingenious combination of Kant and Fichte then no longer suffices.Synthesis through labour mediates the social subject with external nature as its object. But this process of mediation is interlocked with synthesis through struggle, which, in each case, mediates two partial subjects of society that make each other into objects-in other words, two social classes. Knowledge, the synthesis of the material of experience and forms of the mind, is only one aspect of both processes of mediation. Reality is interpreted from a technical viewpoint in the former and from a practical viewpoint in the latter. Synthesis through labour brings about a theoretical-technical relation between subject and object; synthesis through struggle brings about a theoretical-practical relation between them. Productive knowledge arises in the first, reflective knowledge in the second. The only model that presents itself for synthesis of the second sort comes from Hegel. It treats of the dialectic of the moral life,。

新潮研究生英语课后翻译新潮研究生英语教程课后翻译主编:关彦齐副主编:陈晓奇陆博孙丹丹一、汉译英:1.没有调查,就没有发言权He who makes no investigation has no right to speak.2.努力实现和平统一We should strive for the peaceful reunification of the motherland.3.把钟拆开比把它再装起来容易It is easier to take a clock apart than to put it together.4.你三个星期之内完成这项设计不容易It was not easy for you to finish the design in three weeks.5.交翻译之前,必须读几遍,看看有没有要修改的地方Before handing in your translation,you have to read it over and over again and see if there is anything in it to be corrected.6.他越是要掩盖她的烂疮疤,就越是会暴露The more he tried to hide his warts,the more he revealed them.7.你干嘛不去问他Why don’t you go and ask him about it?8.最好把毛衣穿上,外面相当冷You should better put on your sweater,for it’s quite cold outside.9.不努力,不会成功One will not succeed unless one works hard10.什么事也不要落在别人后面No matter what you do,you should not lag behind anyone11.我们必须要培养分析问题、解决问题的能力We must cultivate the ability to analyze and solve problems.12.你要母鸡多生蛋,又不它米吃;要马儿跑得快,又要马儿不吃草。

了解翻译原理英文作文高中英文:Translation is the process of converting a text from one language to another while preserving its meaning. It involves understanding the source text, analyzing its structure and content, and then conveying the same message in the target language. The goal of translation is to ensure that the target audience understands the original message as accurately as possible.There are several principles that govern the translation process. One of them is fidelity, which means that the translation should be as faithful as possible to the original text. This means that the translator should not add or omit anything from the original text and should try to convey the same tone and style.Another principle is equivalence, which means that the translation should convey the same meaning as the originaltext. This can be achieved through different techniques such as literal translation, where the translatortranslates word-for-word, or dynamic translation, where the translator adapts the text to the target audience.Context is also an important factor in translation. The translator should consider the cultural context of both the source and target languages in order to ensure that the translation is appropriate and understandable to the target audience. For example, a phrase that makes sense in one language may not make sense in another language due to cultural differences.In addition, the translator should have a good understanding of both the source and target languages, as well as the subject matter of the text being translated. This allows them to accurately convey the intended meaning of the text.Overall, translation is a complex process that requires a deep understanding of language, culture, and subject matter. A skilled translator can effectively bridge the gapbetween languages and ensure that the original message is accurately conveyed to the target audience.中文:翻译是将一种语言的文本转换为另一种语言并保持其意义的过程。