预期回收率new

- 格式:doc

- 大小:313.00 KB

- 文档页数:10

李强,刘朴真,段敏,等. 食品用PET 瓶回收技术及监管现状[J]. 食品工业科技,2022,43(19):487−493. doi: 10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2022040124LI Qiang, LIU Puzhen, DUAN Min, et al. Recycling Technology and Supervision Strategies of Food Contact PET Bottle[J]. Science and Technology of Food Industry, 2022, 43(19): 487−493. (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2022040124· 专题综述 ·食品用PET 瓶回收技术及监管现状李 强*,刘朴真,段 敏,黄 蓉(中国标准化研究院农业食品标准化研究所,北京 100191)摘 要:聚对苯二甲酸乙二醇酯(PET )因其优良的材料性能,被广泛应用于矿泉水、软饮料、啤酒等食品包装领域,但由此带来的巨量废旧PET 瓶对环境保护产生了巨大的压力。

而随着PET 瓶回收再生技术的发展,废旧PET 瓶再生食品接触材料成为趋势,并已在多个国家成功应用。

本文介绍了PET 瓶化学和物理回收技术及主要的应用企业,同时概述了国际上包括美国、加拿大、欧盟、英国、日本、韩国等国家回收PET 用于食品接触材料的监管措施,对比我国相关法律法规,为我国回收PET 再生并作为可接触食品材料提供参考意见,包括推进垃圾分类管理、完善风险评估体系、制定相关食品安全国家标准等。

关键词:PET ,回收技术,食品接触材料,法律法规本文网刊:中图分类号:TS206 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1002−0306(2022)19−0487−07DOI: 10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2022040124Recycling Technology and Supervision Strategies of Food Contact PET BottleLI Qiang *,LIU Puzhen ,DUAN Min ,HUANG Rong(Institute of Agricultural Food Standardization, China National Institute of Standardization, Beijing 100191, China )Abstract :According to its excellent properties, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is widely used as food containers in mineral water, soft drinks, beers, etc., resulting in a huge waste of PET bottles which increases the environmental burden.With the development of the recycling technology of PET bottles, the discarded PET bottles after consumption have been reused as food containers in many countries successfully. This paper is mainly focused on the new developments of chemical and physical PET recycling technology and its application in enterprises and outlines regulations in the United States, Canada, the European Union, Britain, Japan, South Korea and other countries. The relevant laws and regulations of PET recycling as food containers in our country have also been reviewed. The purpose of this paper is to provide reference opinions on recycling PET to produce food contact materials in China, including promoting waste classification management, improving the risk assessment systems, and formulating relevant national food safety standards.Key words :PET ;recycling technology ;food contact material ;laws and regulationsPET 在世界塑料中具有重要的地位,其因高强度、轻质量、无异味等特点,在食品包装领域特别是PET 饮料瓶中应用广泛。

催收经理的三大关键指标回收率回款率和追回时间催收经理的三大关键指标:回收率、回款率和追回时间催收经理在管理团队的时候,需要关注并评估催收绩效。

而对于催收业务来说,回收率、回款率和追回时间是三大关键指标。

本文将分析这三个指标的重要性以及如何有效跟踪和提升它们。

一、回收率回收率是衡量催收工作的效果和成功率的指标之一。

回收率指的是催收部门成功回收的欠款金额与总欠款金额之间的比例。

回收率的提高可以帮助企业有效降低坏账损失并增加催收效益。

要提升回收率,催收经理需要采取以下措施:1.建立高效的催收团队:催收经理需要招聘有经验且专业的催收人员,并提供持续的培训和激励措施。

2.设定明确的目标和KPI(关键绩效指标):催收经理应该与团队共同设定可量化和可衡量的目标,以激励团队成员追求更高的回收率。

3.制定科学的催收策略:催收经理可以通过数据分析和风险评估来制定个性化的催收方案,提高催收成功率。

二、回款率回款率是指催收部门成功收回的欠款金额与已回款账户欠款总金额之间的比例。

回款率的提高可以帮助企业加速资金流转,增加资金的可用性。

提升回款率的关键措施包括:1.优化还款方式:催收经理可以根据客户的还款能力和偏好,灵活地选择适合的还款方式,如分期付款、信用卡代扣等。

2.提供良好的客户服务:催收经理应确保催收团队与客户之间的有效沟通,解决客户问题,提供帮助和支持,提高客户还款的意愿和主动性。

3.建立催收技巧库:催收经理可以收集整理各类行业催收的最佳实践和技巧,指导团队成员在实际操作中更加有效地与客户进行沟通和协商。

三、追回时间追回时间是指催收部门从开始催收到成功收回欠款的平均时间。

缩短追回时间可以帮助企业快速解决资金困难和降低损失。

为了缩短追回时间,催收经理可以采取以下举措:1.建立高效的案件管理系统:催收经理可以借助信息技术手段建立案件跟踪和管理系统,提高团队协作效率,并及时发现和解决催收难点。

2.强化沟通和协作:催收经理应与其他部门(例如法务、风控等)建立紧密的合作机制,加强信息共享和工作协同,协助解决催收过程中的问题。

经济金融术语中英文对照D (2)E (3)F (3)G (5)J (8)K (10)L (11)M (12)N (13)P (13)Q (14)R (15)W (15)X (16)Y (18)Z (19)D打白条 issue IOU大额存单 certificate of deposit(CD)大额提现 withdraw deposits in large amounts大面积滑坡 wide-spread decline大一统的银行体制(all-in-one)mono-bank system呆账(请见“坏账”) bad loans呆账准备金 loan loss reserves(provisions)呆滞贷款 idle loans贷款沉淀 non-performing loans贷款分类 loan classification贷款限额管理 credit control;to impose credit ceiling贷款约束机制 credit disciplinary(constraint)mechanism代理国库 to act as fiscal agent代理金融机构贷款 make loans on behalf of other institutions 戴帽贷款 ear-marked loans倒逼机制 reversed transmission of the pressure for easing monetary condition道德风险 moral hazard地区差别 regional disparity第一产业 the primary industry第二产业 the secondary industry第三产业 the service industry;the tertiary industry 递延资产 deferrable assets订货不足 insufficient orders定期存款 time deposits定向募集 raising funds from targeted sources东道国(请见“母国”) host country独立核算 independent accounting短期国债 treasury bills对冲操作 sterilization operation;hedging对非金融部门债权 claims on non-financial sector多种所有制形式 diversified ownershipE恶性通货膨胀 hyperinflation二级市场 secondary marketF发行货币 to issue currency发行总股本 total stock issue法定准备金 required reserves;reserve requirement法人股 institutional shares法人股东 institutional shareholders法治 rule of law房地产投资 real estate investment放松银根 to ease monetary policy非现场稽核 off-site surveillance(or monitoring)非银行金融机构 non-bank financial institutions非赢利性机构 non-profit organizations分税制 assignment of central and local taxes;tax assignment system分业经营segregation of financial business (services);division of business scope based on the type of financial institutions风险暴露(风险敞口) risk exposure风险管理 risk management风险意识 risk awareness风险资本比例 risk-weighted capital ratios风险资本标准 risk-based capital standard服务事业收入 public service charges;user's charges扶贫 poverty alleviation负增长 negative growth复式预算制double-entry budgeting;capital and current budgetary accountG改革试点 reform experimentation杠杆率 leverage ratio杠杆收购 leveraged buyout高息集资 to raise funds by offering high interest个人股 non-institutional shares根本扭转 fundamental turnaround(or reversal)公开市场操作 open market operations公款私存 deposit public funds in personal accounts公用事业 public utilities公有经济 the state-owned sector;the public sector公有制 public ownership工业成本利润率 profit-to-cost ratio工业增加值 industrial value added供大于求 supply exceeding demand;excessive supply鼓励措施 incentives股份合作企业 joint-equity cooperative enterprises股份制企业 joint-equity enterprises股份制银行 joint-equity banks固定资产贷款 fixed asset loans关税减免 tariff reduction and exemption关税减让 tariff concessions关税优惠 tariff incentives;preferential tariff treatment规范行为 to regularize(or standardize)…behavior规模效益 economies of scale国计民生 national interest and people's livelihood国家对个人其他支出 other government outlays to individuals 国家风险 country risk国际分工 international division of labor国际收支 balance of payments国有独资商业银行 wholly state-owned commercial banks国有经济(部门) the state-owned(or public)sector国有企业 state-owned enterprises(SOEs)国有制 state-ownership国有资产流失 erosion of state assets国债回购 government securities repurchase国债一级自营商 primary underwriters of government securities 过度竞争 excessive competition过度膨胀 excessive expansionH合理预期 rational expectation核心资本 core capital合资企业 joint-venture enterprises红利 dividend宏观经济运营良好 sound macroeconomic performance宏观经济基本状况 macroeconomic fundamentals宏观调控 macroeconomic management(or adjustment)宏观调控目标 macroeconomic objectives(or targets)坏账 bad debt还本付息 debt service换汇成本unit export cost;local currency cost of export earnings汇兑在途 funds in float汇兑支出 advance payment of remittance by the beneficiary's bank汇率并轨 unification of exchange rates活期存款 demand deposits汇率失调 exchange rate misalignment混合所有制 diversified(mixed)ownership货币政策态势 monetary policy stance货款拖欠 overdue obligations to suppliers过热J基本建设投资 investment in infrastructure基本经济要素 economic fundamentals基本适度 broadly appropriate基准利率 benchmark interest rate机关团体存款 deposits of non-profit institutions机会成本 opportunity cost激励机制 incentive mechanism积压严重 heavy stockpile;excessive inventory挤提存款 run on banks挤占挪用 unwarranted diversion of(financial)resources(from designated uses)技改投资 investment in technological upgrading技术密集型产品 technology-intensive product计划单列市 municipalities with independent planning status 计划经济 planned economy集体经济 the collective sector加大结构调整力度 to intensify structural adjustment加工贸易 processing trade加快态势 accelerating trend加强税收征管稽查 to enhance tax administration加权价 weighted average price价格放开 price liberalization价格形成机制 pricing mechanism减亏 to reduce losses简化手续 to cut red tape;to simplify(streamline)procedures 交投活跃 brisk trading缴存准备金 to deposit required reserves结构扭曲 structural distortion结构失调 structural imbalance结构性矛盾突出 acute structural imbalance结构优化 structural improvement(optimization)结汇、售汇 sale and purchase of foreign exchange金融脆弱 financial fragility金融动荡 financial turbulence金融风波 financial disturbance金融恐慌 financial panic金融危机 financial crisis金融压抑 financial repression金融衍生物 financial derivatives金融诈骗 financial fraud紧缩银根 to tighten monetary policy紧缩政策 austerity policies;tight financial policies经常账户可兑换 current account convertibility经济特区 special economic zones(SEZs)经济体制改革 economic reform经济增长方式的转变 change in the main source of economic growth(from investment expansion to efficiency gains)经济增长减速 economic slowdown;moderation in economic growth 经济制裁 economic sanction经营自主权 autonomy in management景气回升 recovery in business activity境外投资 overseas investment竞争加剧 intensifying competition局部性金融风波 localized(isolated)financial disturbance 迹象 signs of overheatingK开办人民币业务 to engage in RMB business可维持(可持续)经济增长 sustainable economic growth可变成本 variable cost可自由兑换货币 freely convertible currency控制现金投放 control currency issuance扣除物价因素 in real terms;on inflation-adjusted basis库存产品 inventory跨国银行业务 cross-border banking跨年度采购 cross-year procurement会计准则 accounting standardL来料加工 processing of imported materials for export离岸银行业务 off-shore banking(business)理顺外贸体制 to rationalize foreign trade regime利率杠杆的调节作用 the role of interest rates in resource allocation利润驱动 profit-driven利息回收率 interest collection ratio联行清算 inter-bank settlement连锁企业 franchise(businesses);chain businesses良性循环 virtuous cycle两极分化growing income disparity;polarization in income distribution零售物价指数 retail price index(RPI)流动性比例 liquidity ratio流动资产周转率/流通速度 velocity of liquid assets流动资金贷款 working capital loans流通体制 distribution system流通网络 distribution network留购(租赁期满时承租人可购买租赁物) hire purchase垄断行业 monopolized industry(sector)乱集资 irregular(illegal)fund raising乱收费 irregular(illegal)charges乱摊派 unjustified(arbitrary)leviesM买方市场 buyer's market卖方市场 seller's market卖出回购证券 matched sale of repo贸易差额 trade balance民间信用 non-institutionalized credit免二减三 exemption of income tax for the first two years ofmaking profit and 50% tax reduction for thefollowing three years明补 explicit subsidy明亏 explicit loss名牌产品 brand products母国(请见“东道国”) home countryN内部控制 internal control内部审计 internal audit内地与香港 the mainland and Hong Kong内债 domestic debt扭亏为盈 to turn a loss-making enterprise into a profitable one扭曲金融分配 distorted allocation of financial resources 农副产品采购支出 outlays for agricultural procurement农村信用社 rural credit cooperatives(RCCs)P泡沫效应 bubble effect泡沫经济 bubble economy培育新的经济增长点 to tap new sources of economic growth 片面追求发展速度 excessive pursuit of growth平衡发展 balanced development瓶颈制约 bottleneck(constraints)平稳回升 steady recovery铺底流动资金 initial(start-up)working capital普遍回升 broad-based recovery配套改革 concomitant(supporting)reforms配套人民币资金 lQ企业办社会 enterprises burdened with social responsibilities 企业集团战略 corporate group strategy企业兼并重组 company merger and restructuring企业领导班子 enterprise management企业所得税 enterprise(corporate)income tax企业效益 corporate profitability企业资金违规流入股市 irregular flow of enterprise funds into the stock market欠税 tax arrears欠息 overdue interest强化税收征管 to strengthen tax administration强制措施 enforcement action翘尾因素 carryover effect切一刀 partial application清理收回贷款 clean up and recover loans(破产)清算 liquidation倾斜政策 preferential policy区别对待 differential treatment趋势加强 intensifying trend全球化 globalization权益回报率 returns on equity(ROE)缺乏后劲 unsustainable momentumR绕规模贷款 to circumvent credit ceiling人均国内生产总值 per capita GDP人均收入 per capita income人民币升值压力 upward pressure on the Renminbi(exchange rate)认缴资本 subscribed capital软贷款 soft loans软预算约束 soft budget constraint软着陆 soft landingocal currency funding of…W外部审计 external audit外国直接投资 foreign direct investment (FDI)外汇储备 foreign exchange reserves外汇调剂 foreign exchange swap外汇占款 the RMB counterpart of foreign exchange reserves;the RMB equivalent of offcial foreign exchange holdings外向型经济 export-oriented economy外债 external debt外资企业 foreign-funded enterprises完善现代企业制度 to improve the modern enterprise system 完税凭证 tax payment documentation违法经营 illegal business委托存款 entrusted deposits稳步增长 steady growth稳健的银行系统 a sound banking system稳中求进 to make progress while ensuring stability无纸交易 book-entry(or paperless/scriptless)transaction 物价监测 price monitoringX吸纳流动性 to absorb liquidity稀缺经济 scarcity economy洗钱 money laundering系统内调度 fund allocation within a bank系统性金融危机 systemic financial crisis下岗工人 laid-off employees下游企业 down-stream enterprises现场稽核 on-site examination现金滞留(居民手中) cash held outside the banking system 乡镇企业 township and village enterprises(TVEs)消费物价指数 consumer price index(CPI)消费税 excise(consumption)tax消灭财政赤字to balance the budget;to eliminate fiscal deficit销货款回笼 reflow of corporate sales income to the banking system销售平淡 lackluster sales协议外资金额 committed amount of foreign investment新经济增长点 new sources of economic growth新开工项目 new projects;newly started projects新增贷款 incremental credit; loan increment; credit growth; credit expansion新增就业位置 new jobs;new job opportunities信贷规模考核 review the compliance with credit ceilings信号失真 distorted signals信托投资公司 trust and investment companies信息不对称 information asymmetry信息反馈 feedback(information)信息共享系统 information sharing system信息披露 information disclosure信用扩张 credir expansion信用评级 credit rating姓“资”还是姓“社”pertaining to socialism or capitalism;socialist orcaptialist行政措施 administrative measures需求膨胀 demand expansion; excessive demand虚伪存款 window-dressing deposits削减冗员 to shed excess labor force寻租 rent seeking迅速反弹 quick reboundY养老基金 pension fund一刀切universal application;non-discretionary implementation一级市场 primary market应收未收利息 overdue interest银行网点 banking outlets赢利能力 profitability营业税 business tax硬贷款(商业贷款) commercial loans用地审批 to grant land use right有管理的浮动汇率 managed floating exchange rate证券投资 portfolio investment游资(热钱) hot money有市场的产品 marketable products有效供给 effective supply诱发新一轮经济扩张 trigger a new round of economic expansion 逾期贷款 overdue loans;past-due loans与国际惯例接轨to become compatible with internationally accepted与国际市场接轨 to integrate with the world market预算外支出(收入) off-budget (extra-budgetary) expenditure (revenue)预调 pre-emptive adjustment月环比 on a month-on-month basis; on a monthly basisZ再贷款 central bank lending在国际金融机构储备头寸 reserve position in international financial institutions在人行存款 deposits at (with) the central bank在途资金 fund in float增加农业投入 to increase investment in agriculture增势减缓 deceleration of growth;moderation of growthmomentum增收节支措施revenue-enhancing and expenditure control measures增长平稳 steady growth增值税 value-added tax(VAT)涨幅偏高 higher-than-desirable growth rate;excessive growth 账外账 concealed accounts折旧 depreciation整顿 retrenchment;consolidation政策工具 policy instrument政策性业务 policy-related operations政策性银行 policy banks政策组合 policy mix政府干预 government intervention证券交易清算 settlement of securities transactions证券业务占款 funding of securities purchase支付困难 payment difficulty支付能力 payment capacity直接调控方式向 to increase the reliance on indirect policy instruments间接调控方式转变职能转换 transformation of functions职业道德 professional ethics指令性措施 mandatory measures指令性计划 mandatory plan;administered plan制定和实施货币政策 to conduct monetary policy;to formulate and implement monetary policy滞后影响 lagged effect中介机构 intermediaries中央与地方财政 delineation of fiscal responsibilities分灶吃饭重点建设 key construction projects;key investment project周期谷底 bottom(trough)of business cycle周转速度 velocity主办银行 main bank主权风险 sovereign risk注册资本 registered capital逐步到位 to phase in;phased implementation逐步取消 to phase out抓大放小 to seize the big and free the small(to maintain close oversight on the large state-ownedenterprises and subject smaller ones to market competition)专款专用 use of funds as ear-marked转贷 on-lending转轨经济 transition economy转机 turnaround转折关头 turning point准财政赤字 quasi-fiscal deficit准货币 quasi-money资本不足 under-capitalized资本充足率 capital adequacy ratio资本利润率 return on capital资本账户可兑换 capital account convertibility资不抵债 insolvent;insolvency资产负债表 balance sheet资产负债率liability/asset ratio;ratio of liabilities to assets资产集中 asset concentration资产贡献率 asset contribution factor资产利润率 return on assets (ROA)资产质量 asset quality资产组合 asset portfolio资金成本 cost of funding;cost of capital;financing cost资金到位 fully funded (project)资金宽裕 to have sufficient funds资金利用率 fund utilization rate资金缺口 financing gap资金体外循环 financial disintermediation资金占压 funds tied up自筹投资项目 self-financed projects自有资金 equity fund综合国力 overall national strength(often measured by GDP)综合效益指标 overall efficiency indicator综合治理 comprehensive adjustment(retrenchment);over-haul 总成交额 total contract value总交易量 total amount of transactions总成本 total cost最后贷款人 lender of last resort。

中小学教师的课程取向及其特点_职业教育论文摘要:课程取向问卷调查的结果表明:中小学教师对认知过程取向的认同度最高,但也不排斥其他四种取向;男教师比女教师更倾向于学术理性取向;不同教龄的教师在认知过程、科技发展、社会重建、学术理性取向上有显著差异;不同学校类别的教师在科技发展、人文主义、社会重建、学术理性取向上有极其显著的差异;不同学历的教师在科技发展、人文主义、社会重建、学术理性取向上有非常显著的差异;教师的新课程培训状况对科技发展、认知过程、社会重建取向有影响。

在此基础上对我国的课程研究与改革提出了一些建议。

关键词:课程取向;中小学教师Abstract: The results of the curriculum orientationquestionnaires shows that teachers strongly believe in the cognitive process orientation, but they generally do not reject the other four orientations. Male teachers incline more to the academic rationalism orientation than female teachers; there are statistically significant differences among those who have different years of teaching experience in cognitive process, the technological development, the social reconstruction and the academic rationalism orientations; there are rather significant differences among those who are scattered in schools and among those who are with different academic degree in the technological development, humanistic, the social reconstruction and the academic rationalism orientations. Also, the paper has found out that the training state of the new curriculum for teachers has an effect on the technological development, cognitive process, and social reconstruction orientations.And some suggestions on curriculum reform and research in China have been put forward.Key words: curriculum orientation; primary and secondary school teachers一、课程取向的分类及其意义课程取向是人们对课程的总的看法和认识,由于人们的哲学思想、价值观、方法论、文化背景以及对个体的心理发展等方面问题认识上的差异,导致对课程的不同看法,这些不同看法就形成了课程取向。

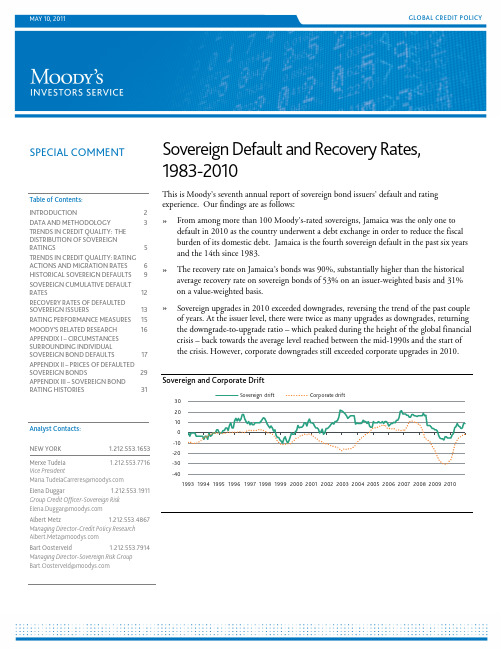

GLOBAL CREDIT POLICYMAY 10, 2011Sovereign Default and Recovery Rates, 1983-2010This is Moody’s seventh annual report of sovereign bond issuers’ default and rating experience. Our findings are as follows:» From among more than 100 Moody’s-rated sovereigns, Jamaica was the only one todefault in 2010 as the country underwent a debt exchange in order to reduce the fiscal burden of its domestic debt. Jamaica is the fourth sovereign default in the past six years and the 14th since 1983. » The recovery rate on Jamaica’s bonds was 90%, substantially higher than the historicalaverage recovery rate on sovereign bonds of 53% on an issuer-weighted basis and 31% on a value-weighted basis. » Sovereign upgrades in 2010 exceeded downgrades, reversing the trend of the past coupleof years. At the issuer level, there were twice as many upgrades as downgrades, returning the downgrade-to-upgrade ratio – which peaked during the height of the global financial crisis – back towards the average level reached between the mid-1990s and the start of the crisis. However, corporate downgrades still exceeded corporate upgrades in 2010.»In 1983, all 12 rated sovereign issuers were investment grade. Since then the sovereign rating mix has gradually drifted downwards, so that by the end of 1999 only 58% of sovereign issuers hadinvestment-grade ratings. Over the period 2000-06, that share climbed back up modestly to 64%, falling back to 61% during the recent global financial crisis.»Sovereigns rated Caa-C have experienced a larger number of upgrades than have similarly rated corporates. This is because, once their defaults are cured, most sovereigns are eventually upgraded. » A comparison between sovereign and corporate default rates shows that sovereign default rates have been, on average, modestly lower than those for corporates, overall and in terms of like-for-like rating symbols. However, the differences are not significant because the overall size of the sovereign sample is small and as default risk has been highly correlated across emerging market sovereign issuers.IntroductionThis year’s sovereign default study examines the rating histories and default e xperience of 108 Moody’s-rated governments issuing local and/or foreign currency bonds. This is an increase of four sovereigns compared with the 2009 study (Exhibit 1). As has been the case during the last decade, the initial ratings assigned to these sovereign issuers were in the middle/upper range of the speculative-grade category, thus contributing to the downward drift in the sovereign rating mix since Moody’s started rating sovereigns.EXHIBIT 1Coverage of Moody’s-Rated Sovereign Issuers Included in the Study, Rating Withdrawals in ParenthesisInitial Rating Date Number Of RatedIssuers Issuer1949-1985 12 United States, Panama, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, Canada, Venezuela, Austria, Finland, Sweden, Norway, United Kingdom, Japan, Switzerland, (Panama, Venezuela)1986 19 Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Italy, Malaysia, Netherlands, Portugal 1987 21 Ireland, Venezuela1988 26 Belgium, China, France, Hong Kong, Spain1989 29 Iceland, Luxembourg, Thailand1990 31 Mexico, Micronesia1991 311992 32 Turkey1993 37 Colombia, Czech Republic, Philippines, Trinidad & Tobago, Uruguay 1994 44 Barbados, Bermuda, Greece, Indonesia, Malta, Pakistan, South Africa 1995 46 Israel, Poland1996 58 Bahrain, Bulgaria, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Lithuania, Mauritius, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Slovenia, United Arab Emirates, Panama1997 70 Bahamas, Costa Rica, Croatia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Lebanon, Macao, Moldova, Oman, Romania, Turkmenistan1998 86 Bolivia, Cyprus, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Hungary, India, Jamaica, Korea, Nicaragua, Papau New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Singapore, Slovakia, Taiwan, Ukraine1999 96 Belize, Chile, Egypt, Estonia, Fiji Islands, Iran, Latvia, Morocco, Qatar, Tunisia 2000 96EXHIBIT 1Coverage of Moody’s-Rated Sovereign Issuers Included in the Study, Rating Withdrawals in Parenthesis2001 96 Botswana, (Iran) 2002 962003 95 (Micronesia)2004 97 Bosnia and Herzegovina, Suriname 2005 99 Mongolia, Vietnam 2006 101 Armenia, Azerbaijan2007 105 Albania, Belarus, Cambodia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines 2008 106 Montenegro 2009 105 (Moldova)2010108Angola, Bangladesh, Georgia, Sri Lanka, Moldova, (Turkmenistan)Exhibit 2 shows t he geographical coverage of Moody’s sovereign bond ratings. The share of developing and emerging market countries has been increasing from around 20% in the mid-1980s to more than 75% today. The Americas comprised 25% of Moody’s rated sovereign issuers in 2010, which also accounts for 35% of all outstanding general government debt in 2010; Europe represented 41% (and30% in terms of government debt outstanding), the Middle East & Africa 14% (1% of government debt), and Asia Pacific 20% (34% of government debt).Data and MethodologyWhile Moody's assigns a variety of sovereign ratings, this study focuses on sovereign bond ratings, as represented by either the sovereign’s foreign currency (FC) bond rating or local currency (LC) bond rating, whichever is lower.1 1Specifically, we construct the sovereign’s rating history by tracking its minimum outstanding bond rating, regardless of which currency it references.Similarly, we consider whether a sovereign defaults on any of its bond obligations, regardless of currency.Historically, Moody’s has often distinguished between a government’s LC and FC bond rating, with any gap usually in favor of the local currency rating.2Sovereign ratings are withdrawn very rarely: since 1983 Moody’s has only withdrawn ratings six times. Both FC and LC r atings are maintained even when there is no outstanding debt. Unlike c orporates, countries do not merge, shift from public to private sources of capital, or go b ankrupt. However, this practice has gradually changed over time and today such rating gaps are infrequent. The evolution of this approach reflects global economic and market developments. As both current and capital account mobility have increased, as currency markets have deepened, and as the investor base has broadened, the justifications for distinguishing between local and foreign currency government bond ratings have weakened. Crucially, it is far more likely than it used to be that a problem servicing debt in one currency will spill over and affect a government’s ability to service its debt in another. As discussed below, a number of rated sovereigns have cured defaults within a grace period, but with one exception (Peru), they all default without cure shortly thereafter.Moody's definition of sovereign default includes the following types of default events:1. A missed or delayed disbursement of a contractually obligated interest or principal payment(excluding missed payments cured within a contractually allowed grace period), as defined in credit agreements and indentures. 2. A distressed exchange whereby:i) the issuer offers creditors a new or restructured debt, or a new package ofs ecurities, cash or assets, that amount to a diminished financial obligation relative tot he original obligation; and ii) the exchange has the effect of allowing the obligor to avoid a payment default in the future. This definition is intended to capture events that change the relationship between the debt holder anddebt issuer from the relationship that was originally contracted, and which subjects the debt holder to an economic loss.3Although rare in practice, certain government actions which change the originally contracted relationship between the government and its creditors and which impose an economic loss on the creditor could also constitute a default. For example, unlike a general tax on financial wealth, the imposition of a tax by a sovereign on the coupon or principal payment on a specific class of government debt instruments (even if retroactive) would represent a default.4 2In most cases the LC bond rating was the same or higher than the sovereign's FC bond rating due to the fact that a government could generally "print" money if necessary to service LC debts and avoid default, but could find it very difficult, at times, to obtain sufficient foreign exchange to service FC debt. Currently, only India has FC bonds which are rated higher than its LC bonds. For more details, see Moody’s Sovereign Methodology Update, “ Unilateral removal of inflation indexation on inflation-indexed bonds and forced maturity extensions would also represent defaults. Likewise, a forced redenomination of debt instruments imposing an economic loss on creditors would also represent a default. In some of these atypical cases, government actions might be motivated by fairness or other considerations rather than inability or unwillingness to pay.Narrowing the Gap – a Clarification of Moody’s Approach to Local vs. Foreign Currency Government Bond Ratings ”, February 2010. 3We do not consider a general inflation to be a default event. 4The credit event in Turkey in 1999, detailed in Appendix I, although unrated by Moody’s at the time, is an example of such an atypical default.For the purpose of calculating issuer-based default rates, we define a sovereign default to have occurredwhenever a country defaults on any of its bonds. Moody’s does not consider missed interest paymentsthat are fully cured within contractually specified grace periods to be defaults.5Trends in Credit Quality: The Distribution of Sovereign RatingsAs shown in Exhibit 3, by the end of 2010, the share of investment-grade sovereign issuers h ad declinedto little over 60%. While all rated sovereign issuers in 1983 were investment g rade, over the years riskieremerging market countries gained access to debt markets. As m ore sovereign issuers obtained Moody’sratings, the share of speculative-grade ratings rose.EXHIBIT 3More recently, the sovereign rating mix drifted upward between 2001 and 2006. The s hare of sovereignsin the Aaa to single-A categories climbed back to about 50% by the end of 2006, that is, to about thesame levels seen in the mid-1990s. However, the 2007-09 global financial crisis has eroded those gains.It has also changed the distribution within the investment-grade category: the proportion of sovereignsrated Aa has increased, both because some advanced economies were downgraded from Aaa and becauseof upgrades into the Aa category for emerging market economies.The rating distributions of sovereign and corporate bond issuers as of year-end 2010 are c ompared inExhibit 4. The share of issuers rated Aaa is substantially larger for sovereigns t han it is for corporates,while the proportion of sovereigns rated A and Caa-C is smaller. On average, however, sovereign issuershave higher ratings.5 A cured grace-period default is often shortly followed by a debt restructuring with most of the loss to investors borne at this stage by means of a lengthening of maturityand/or a lowering of the coupon. However, as in the case of Peru, a fully cured default within its grace period yields virtually no losses to investors when it is not followed by another default event shortly afterwards. In other words, the presence of a grace-period default often signals the materialization of a future loss, but is not a necessary condition on its own.Trends in Credit Quality: Rating Actions and Migration RatesChanges in the distribution of ratings over time can occur either because of ratings drift or because of the entry or exit of issuers. This section focuses exclusively on rating changes.There were as many rating actions in 2010 as there were in 2009 and twice as many as occurred in 2008, impacting 25% of all rated sovereigns (Exhibit 5). The rating volatility (defined as the sum of upgrades and downgrades over a 12-month period relative to the total number of sovereign issuers at the beginning of the period) increased rapidly from the start of 2009 and has remained high through 2010.While the increase in rating volatility in 2009 was coupled with a gradual downward rating drift overall (net percentage of upgrades relative to downgrades), the increase in the volatility in 2010 came with a shift towards a more positive, upward drift (Exhibit 5). In other words, in 2010 the number of upgrades exceeded the number of downgrades – indeed, at the issuer level there were twice as many upgrades as downgrades. The downgrades-to-upgrades ratio, which had peaked by mid-2009 at above 2, has nowreturned to more normal levels (about 0.7 on average), aided by both fewer downgrades and more upgrades. The same pattern was seen among corporate issuers.However, this increase in credit quality was not uniformly distributed across regions (Exhibit 6). The vast majority (70%) of downgrades occurred in Europe,6 while 56% of upgrades were implemented among sovereigns in the Americas region and a further 39% among sovereigns in both Asia-Pacific and the Middle East and Africa regions.7This meant that the median rating for Europe at the end of 2010 was closer to A2, slightly lower than the A1 median we recorded for the previous nine years. In contrast, the median rating for the Americas region rose by one notch to Ba1 for the first time since the end of 1998.In the 2009 sovereign default study, we explained how ratings in Latin America, Asia-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa proved resilient to the 2007-09 global financial crisis. Indeed, the sovereign upgrades in 2010 were driven by prospects for sustained economic growth and resilience of the financial sector. In the Arabian Gulf, buoyant oil prices and accumulated financial assets enabled most Gulf states to maintain a degree of fiscal stimulus in 2010 without weakening their fiscal position. These countries’ banking sectors also experienced less of a credit shock during the crisis, and the volatility in the European financial markets in 2010 did not have a significant effect on the average cost of funding in the Middle East. In both Asia-Pacific and Latin America, sovereign upgrades were also driven by prudent fiscal and monetary policies as well as by structural reforms across several countries. In Asia, economic growth was supported by spillover effects from China’s growth, while countries in Latin America enjoyed spillover effects from Brazil’s economic strength. International debt forgiveness,8The 2009 sovereign study explained that, although the US was the epicentre of the global crisis, Europe was more deeply affected as a result of its economic openness, mutual trade and financialinterdependence, and relatively higher reliance on banks than capital markets as the source of credit. As aon the other hand, helped Nicaragua and Bolivia to improve their key debt metrics. The sovereign upgrade of the Dominican Republic wasadditionally driven by favorable developments in the country’s institutional framework (e.g. strengthened bank supervision and effective enforcement of prudent regulations) and official efforts that were effective in developing a domestic market for government bonds.6Greece (twice), Hungary, Ireland (twice), Portugal and Spain, in Europe and Bahrain, Jamaica and Vietnam, elsewhere, were downgraded in 2010. 7Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Jamaica, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay and Uruguay in the Americas; China, Hong Kong, India and Korea in Asia-Pacific; Lebanon, Oman and Saudi Arabia in the Middle East; and Turkey in Europe, had their sovereign bond ratings upgraded in 2010. 8As part of the IMF/World Bank Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative and the G8 Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI).result, Europe was the main focus of sovereign downgrades in 2009, as had been the case in 2008. Furtherdowngrades to several European sovereigns in 2010 reflected (a) their relatively weak potential growthprospects over the next three to five years, as they transition away from their focus on sectors that hadbeen the engines of growth in the years preceding the financial crisis (i.e. banking, construction and realestate sectors); and (b) the expectation that interest rates will rise from their historically low levels as aresult of concerns about inflation and credit risk.Other factors also contributed to the renewed downgrades in Europe in 2010. For example, Greece wasdowngraded twice by a total of five notches in 2010 to the top of the speculative-grade category becausethe risk of default was considered to be inconsistent with an investment-grade rating. In spite of theIMF/euro area support program, which substantially reduced the risk of a liquidity-driven default over thenext few years, the adjustments needed to stabilize debt metrics were unprecedented and the risks of theprogram implementation substantial.9Ireland was the other European country that suffered a sizeable multi-notch downgrade, although itremained within the investment-grade category at Baa1. In addition to the reasons already mentionedand common to other European countries, Ireland’s six-notch downgrade was driven in part by therepeated crystallization of bank-related contingent liabilities on the government balance sheet; thecontinued severe downturn in the financial services and real estate sectors; the ongoing contraction inprivate sector credit; the required fiscal austerity program, which was likely to weigh on domestic demand;and the significant deterioration of the government’s financial strength.10Jamaica was the only default in 2010 and the fourth sovereign default over the past six years. Moody’sconsidered Jamaica’s debt exchange, which was completed in February 2010, as an event of default (seenext section for a more detail explanation of the circumstances surrounding the default).Separately, in 2010, we also withdrew all ratings on the government of the Republic of Turkmenistan dueto insufficient or otherwise inadequate information to allow us to maintain a credit rating. We first ratedthe government of Turkmenistan in January 2002 when we assigned a B2 issuer rating to its localcurrency obligations.However, in 2010, we also assigned first-time sovereign ratings of B1 to both Angola and Sri Lanka andBa3 to Bangladesh and Georgia. Additionally, Moody’s re-assigned a B3 rating to Moldova after havingpreviously withdrawn all its ratings and country ceilings in 2009 due to lack of adequate information.Rating migration matrices offer a more complete picture of changes in credit quality over t ime. Exhibit 7shows average 12-month migration rates by rating category since 1983. Each c ell in the matrix shows theaverage fraction of issuers that held a given row's r ating at the beginning of the measurement period andthe column rating at the end of the p eriod, including defaults and withdrawn ratings.The largest values in the transition matrix are along the diagonal, as the most likely rating f or an issuer atthe end of a given 12-month period during the 1983-2010 is the rating with which t he issuer began thatperiod. By contrast, those elements that are off the diagonal reflect t ransitions to higher (the trianglebelow the diagonal) or lower (the triangle above the d iagonal) rating categories within a 12-month period.The further one moves away from the diagonal, t he smaller the migration rates, reflecting a relatively low9For more information on the drivers of Greece’s downgrade, please refer to the Special Comment: “Key Drivers of Greece’s Downgrade to Ba1”.10 For more information please refer to: “Key Drivers of Moody’s Decision to Downgrade Ireland to Baa1 from Aa2”.historical frequency of issuers m oving across more than one rating category during the course of 12months.As shown in Exhibit 7, rating changes have on average been somewhat less frequent for s overeign issuersthan they have for corporate issuers. For example, on average, only 3.2% of Aaa-r ated sovereign issuershave been downgraded in any given 12 months compared to 9.8% (or 13.8% if we also countwithdrawals) for Aaa-rated c orporate issuers. Moreover, sovereign ratings also appear more stable thancorporate ratings in the other i nvestment-grade rating categories, with the differences marginallynarrowing as we a pproach the Baa category. The average stability of sovereign r atings derives from anoverwhelmingly lower historical probability of being downgraded w ithin a 12-month period relative tocorporate issuers.EXHIBIT 7Among speculative-grade issuers, sovereign issuers rated Caa-C have experienced a larger number ofupgrades than have similarly rated corporates.11 The higher rate of upgrade among the lowest-ratedsovereigns reflects the different dynamics of sovereign and corporate ratings: once their defaults have beencured, most sovereigns are eventually upgraded. In contrast, many corporations that are downgraded toCaa or below ultimately restructure in bankruptcy and have their ratings withdrawn.Historical Sovereign DefaultsJamaica’s debt exchange, completed in February 2010, represented an event of default. This was the onlydefault event in 2010 and just the fourth sovereign default in the past six years.Over the previous years, attempts to place Jamaica’s public debt on a more sustainable path had provedunsuccessful. The ratio of public debt to GDP had remained above 100% over the past decade and the 11 A smaller sample size can magnify such rating changes.debt-to-revenue ratio stood at around 400%. The cost of servicing Jamaica’s debt was estimated at over 55% of central government revenues and 16% of GDP. Jamaica’s government had never defaulted before. Instead it was trying to run primary surpluses in recent years, some on the order of 10% of GDP, but at the cost of slashing public investment and contributing to the very low economic growth. GDP growth averaged barely 1% annually prior to the default.The debt exchange did not involve external debt, but it included the entire stock of marketable domestic debt, worth around 60% of GDP or 700 billion Jamaican dollars. The exchange proceeded in an orderly fashion with 99% participation. Jamaica’s government bond ratings had been lowered to Caa1 at the end of 2009 in expectation of a possible debt restructuring. At the announcement of the debt exchange in January 2010, the local currency bond rating was placed at Caa2 to reflect the 20% loss implied by the terms of the debt exchange.Indeed, the debt exchange provided for zero reduction in principal, a cut of the average coupon to 11% from 17%, and an extension of the average debt maturity to five years from two. It caused relatively little dislocation to the economy and the financial sector due to the majority of the debt being held by a few local financial institutions and the exchange being designed to strike a balance between a meaningful cash flow alleviation and preserving the health of the banking system.On March 2010, Moody’s upgraded Jamaica’s government bond ratings to B3, balancing the fiscal relief following the debt exchange and the economic and financial vulnerabilities. Jamaica’s overall debt burden is still relatively high – the debt-to-GDP ratio remains at 113% and interest payments represent 42% of government revenues in 2011.As for previous defaults, Exhibit 8 provides a chronological summary of historical Moody’s-rated sovereign defaults, the bond-default volumes associated with these defaults, and the circumstances surrounding the defaults.EXHIBIT 8Moody’s-Rated Sovereign Bond Defaults since 1983DefaultDate CountryTotalDefaultedDebt($ Millions)Rating atDefault CommentsJul-98 Venezuela $270 Ba2 Defaulted on domestic currency bonds in 1998, although the default was curedwithin a short period of time.Aug-98 Russia $72,709 Caa1 Missed payments first on local currency Treasury obligations. Later a debt servicemoratorium was extended to foreign currency obligations issued in Russia butmostly held by foreign investors. Subsequently, failed to pay principal on MINFINIII foreign currency bonds. Debts were restructured in Aug 1999 and Feb 2000. Sep-98 Ukraine $1,271 B3 Moratorium on debt service for bearer bonds owned by anonymous entities. Onlythose entities willing to identify themselves and convert to local currency accountswere eligible for debt repayments, which amounted to a distressed exchange.Jul-99 Pakistan $1,627 Caa1 Pakistan missed an interest payment in Nov 1998 but cured the defaultsubsequently within the grace period (within 4 days). Shortly, thereafter, itdefaulted again and resolved that default via a distressed exchange which wascompleted in 1999.Aug-99 Ecuador $6,604 B1 Missed payment was followed by a distressed exchange; over 90% of bonds wererestructured.Jan-00 Ukraine $1,064 Caa3 Defaulted on DM-denominated Eurobonds in Feb 2000 and defaulted on USD-denominated bonds in Jan 2000. Offered to exchange bonds with longer-term andlower coupon. The conversion was accepted by a majority of bondholders.Sep-00 Peru $4,870 Ba3 Peru missed payment on its Brady Bonds but subsequently paid approximately $80EXHIBIT 8Moody’s-Rated Sovereign Bond Defaults since 1983Default Date CountryTotalDefaultedDebt ($ Millions)Rating atDefaultCommentsmillion in interest payments to cure the default, within the 30-day grace period.Nov-01 Argentina$82,268Caa3Declared it would miss payment on foreign debt in November 2001. Actual payment missed on Jan 3, 2002. Debt was restructured through a distressedexchange offering where the bondholders received haircuts of approximately 70%. Jun-02 Moldova $145 Caa1Missed payment on the bond in June 2001 but cured default shortly thereafter. Afterwards, it began gradually buying back its bonds, but in June 2002, after having bought back about 50% of its bonds, it defaulted again on the remaining $70 million of its outstanding issue.Jul-03 Nicaragua $320 Caa1In July 2003, Nicaragua completed a distressed exchange of CENI bonds (which were initially issued as Central Bank recapitalization bonds in the 2000 banking crisis and which were denominated in US dollars and payable in local currency) held by a few domestic banks. The exchange reduced the interest rate paid on the bonds from 15.3%-21.0% to 8.3-10.0% and extended the maturity from five to ten years. Another debt exchange of the same bonds (face value US$295.7mn at that time, held by two domestic banks) followed in June 2008, when the maturity was extended further from ten to twenty years and the interest rate was reduced to about 5%. The 2008 exchange involved 12.5% of the total debt and a 50% NPV loss.May-03 Uruguay $5,744 B3Contagion from Argentina debt crisis in 2001 led to a currency crisis in Uruguay. To restore debt-sustainability, Uruguay completed a distressed exchange with bondholders that led to extension of maturity by five years.Apr-05 DominicanRepublic$1,622 B3After several grace period defaults (missed payments cured within the graceperiod), the country executed an exchange offer in which old bonds were swapped for new bonds with a five-year maturity extension, but the same coupon and principal.Dec-06 Belize $242 Caa3Belize announced a distressed exchange of its external bonds for new bonds due in 2029 with a face value of U.S.$ 546.8. The new bonds are denominated in U.S. dollars and provide for step-up coupons that have been set at 4.25% per annum for the first three years after issuance. When the collective action clause in one of Belize's existing bonds is taken into account, the total amount covered by this financial restructuring represents 98.1% of the eligible claims.Dec-08 Ecuador $3,210 Caa1In November 2008, Ecuador missed an interest payment of $30.6 million on its $510 million of 12% global bonds due in 2012. Additionally, a $135 million interest payment on the 2030 global bonds ($2.7 billion) was missed in February 2009. The authorities announced that the 2012 and the 2030 securities are “illegal” and “illegitimate.” The restructuring plan announced in May 2009 included a 65% haircut on the face value of the bonds and Ecuador bought back 91% of the defaulted foreign bonds.Feb-10 Jamaica $7,900 Caa1In February 2010, Jamaica completed a debt exchange for its entire stock ofmarketable domestic debt, including J$234.9bn of fixed-rate bonds, J$375.9bn of variable rate bonds, and J$90.6bn of US dollar-indexed domestic bonds, issued prior to 31 December 2009. The exchange replaced 350 old bonds with 23 new benchmark bonds (9 fixed-rate bonds, 9 variable rate, 3 US dollar bonds and 2 CPI-linked bonds). The terms of the exchange provided for zero reduction in principal, a cut of the average coupon to around 11% from 17%, and an extension of the average debt maturity to about five years from two. The exchange entailed about 20% NPV loss. Participation was 99%.Note: The case of Peru represents a grace-period default and is shown in the table for completeness but does not enter t he default rate calculations.Although our sample begins in 1983, there were no Moody’s-rated sovereign bond defaults until 1998. A mixture of cooling global economic conditions, unfavorable market sentiment after the Asian crisis, and external shocks, as well as an increase in the share of speculative-grade sovereign bond issuers in the mid-1990s produced five Moody's-rated sovereign bond defaults in 1998-1999: Russia, Pakistan, Ukraine,。

回收率是含量测定方法验证的指标之一,它是用来衡量方法的准确度的准确度accuracy 是指测得结果与真实值接近的程度,表示分析方法测量的正确性。

由于“真实值”无法准确知道,因此,通常采用回收率试验来表示。

生物药物分析中,常用标准添加法来计算回收率,即取已准确测定药物含量P present的真实样品如人血浆样品等,再加入药物标准品已知量A added,混合物作为测定液,其测定值为M measured。

测定液要配制成高、中、低三种浓度,每个浓度测定3-5 次,求出每种浓度的平均测定值M,且RSD 应符合要求。

由于预先要准确测定样品中原含有的药物量P,因此也应测定3-5 次,求其平均值P,且RSD 应符合要求。

回收率=(测定液平均测定值M - 原样品液含量平均值P)/ 加入量A×100%回收率结果越接近100%表明分析方法准确度越高。

生物样品分析时,一般控制回收率范围应为85%-115%样品药浓>200ug/L及80-120%样品药浓<200ug/L。

制剂的含量测定时,采用在空白辅料中加入原料药对照品的方法作回收试验及计算RSD,还应作单独辅料的空白测定。

每份均应自配制模拟制剂开始,要求至少测定高、中、低三个浓度,每个浓度测定三次,共提供9 个数据进行评价。

回收率=(平均测定值M -空白值B)/ 加入量A×100%回收率的RSD 一般应为2%以内。

比如:Y1E5X-307805 R0.9999如上在此回归曲线上用外标法就不好回归方程的作用有两个,一是选定一点还是两点法,307805/100001,再用一点法就不行了,因为他们都不成正比例关系。

第二才是看回归的结果。

如果第一个都不能满足,就没有继续下去的必要了,必须换用外标两点法了!准备两个相同的被测样,一个加入已知含量的标准工作液,一个未加,经过相同的处理后,先检测样品所测组分的含量,然后检测加入标准工作液样品的含量,减去开始所测组分含量以后,除以所加标准工作液的已知浓度,然后乘以百分之百,就可得出实际样品的回收率加标回收率计算的定义公式R加标试样测定值-试样测定值/加标量100有文献上说加标回收率在80-120之间属于正常值。

名词解释投资回收率解释说明以及概述1. 引言1.1 概述投资回收率是一个重要的财务指标,用于评估投资项目的经济效益和可行性。

在商业领域中,每个企业都希望通过投资获取高额的回报,并确保资金的有效运用。

因此,了解和计算投资回收率对于企业管理者和投资者来说至关重要。

1.2 文章结构本文将首先解释投资回收率的定义和概念,包括其在不同情境中的应用领域。

然后,我们将详细介绍计算投资回收率的方法,并讨论其重要性以及在决策分析中的作用。

接下来,我们将探讨影响投资回收率的各种因素,如投资规模与期限、预期盈利和风险情况以及市场环境和行业特点。

最后,我们将总结本文,并展望未来有关投资回收率研究的发展方向。

1.3 目的本文旨在深入探讨投资回收率这一重要概念,并帮助读者理解其定义、计算方法以及应用领域。

同时,我们还将分析影响投资回收率的因素,并强调其在经济效益评估和决策分析中的重要性。

通过阅读本文,读者将能够更好地应用投资回收率概念,从而提高企业投资决策的准确性和效果。

2. 投资回收率解释说明2.1 定义和概念投资回收率是一种用于评估投资项目收益水平的指标,它反映了投资项目在规定时间内所产生的经济效益与投入成本之间的比例关系。

简而言之,投资回收率衡量了一个投资项目能够创造多少经济价值相对于其成本。

2.2 计算方法投资回收率的计算方法为:将某一特定时期内的净现金流量除以该时期的总投入成本,并将结果乘以100%。

投资回收率= (某一特定时期内净现金流量/ 总投入成本)* 100%其中,净现金流量指的是从该项目中获得的现金流量减去支付给供应商、雇员和其他相关方的现金流出;总投入成本包括直接成本(如采购费用、设备成本等)和间接成本(如管理费用、维护费用等)。

2.3 应用领域投资回收率常被广泛应用于企业决策过程中,尤其是在评估不同投资机会时。

它可以帮助企业管理者更好地理解不同项目之间的风险和回报,并为决策提供有价值的参考。

此外,投资回收率也被用于评估公共项目、政府计划和非营利组织的效益,以确保资源得到最佳利用。

资讯•海外视野欧盟生物基化学品产量至2025年将保持年增长3.6%欧盟委员会联合研究中心近期发布了一份重要报告,详细介绍了生物基化学品在欧盟市场的潜力,并预测从2018年到2025年,每年的产量将保持3.6%的增长。

在报告中,专家描述了10类关键的生物基化学产品,详细介绍了它们在欧盟市场的生产和消费水平,成熟程度,以及它们未来发展的主要驱动因素和制约因素。

这10类产品分别是平台化学品,溶剂,塑料聚合物,油漆、涂料、油墨和染料,表面活性剂,化妆品和个人护理用品,粘合剂,润滑油,增塑剂及人造纤维。

据统计,欧盟生物基产品生产总量每年约为470万吨,在整个市场中占据3%(即石油基产品为97%),市场多样化且规模巨大,产品类别之间存在差异,预计近几年复合年增长率为3.6%o目前在生物产业的发展中依然存在障碍,如生产成本,但也有很大的机遇。

欧洲纸及纸包装回收率达85.5%创历史新高近日,欧盟公布了最新的回收数据,整个欧洲的纸及纸包装的回收率创历史新高。

根据欧盟28个成员国进行统计,纸和纸包装的回收率高达85.5%,创造有史以来最高的记录,同时在各类包装材料中排名第一。

欧洲纸板纸箱制造商协会ProCarton的总经理T o nyHitchin补充说:看到纸和纸包装回收率如此之高,我很欣慰。

特别巧的是,这次的数据恰好在全球回收日前公布,非常符合主题。

我们的用户调研数据证实了纸箱/纸板不仅是最有利于回收的包装材质,更重要的是对环境的保护。

这次的研究报告还显示,有63%的英国消费者认同纸箱是最可回收的包装材质。

因为,纸箱是替代其他包装形式的绿色包装选择,不仅可再生,而且100%可回收,可生物降解,达到经济效益环境效益的平衡。

2023年美国零售业瓦楞包装需求将达18亿美元美国零售包装对瓦楞产品的需求将以每年3.2%增幅增长,这意味着,到2023年美国零售行业对瓦楞包装的需求将达18亿美元。

由于商场面积有限,因此能够进行展示的商品也有限,这在一定程度上会限制销售业绩。

丝胶占蚕丝的20%~30%[1],蚕丝织物精练就是要脱去丝胶,因此在蚕丝织物精练液废水中含有高浓度的丝胶蛋白。

如果不将丝胶提取出来,废水直接排到污水总管道,一方面会增加污水处理厂生物氧化池的负荷,消耗大量的活性污泥,使污水处理效率降低、成本增加,也会影响后续的污泥脱水干化,使脱水效率降低;另一方面,丝胶蛋白有许多优异的性能,可以广泛应用于织物后整理[2]、化妆品[2]、食品添加剂[3]、功能性生物材料[3]等。

如丝胶蛋白具有优良的吸湿保湿性,可用于合成纤维织物的后整理[4],提高其吸放湿性能,减少静电荷,使穿着更舒适,特别适用于制作内衣、内裤、婴儿衣服、床上用品及汽车内饰材料等。

如用于化妆品添加剂,丝胶是一种理想的天然保湿因子,可使皮肤保持一定水分,而且能抑制酪氨酸酶活性,有效地抑制黑色素形成[5]。

基于以上两点,应将丝胶废水中的丝胶蛋白提取出来,纯化、干燥,变废为宝。

目前,国内外丝胶的提取方法主要有酸析法[6]、摘要丝绸印染厂的蚕丝织物精练液未提取丝胶蛋白就排放到污水处理厂,不仅浪费资源,还增加了后续污水处理的难度。

丝胶蛋白具有许多优异的性能,可用于织物后整理、化妆品、食品添加剂、功能性生物材料等领域。

因此亟需研究高效、简便、易于推广的回收新方法。

在适当pH 条件下,利用单宁沉降法结合冷冻法,详细探讨了提取工艺,确定了最佳工艺。

与酸析法比较,最佳工艺的回收率提高16个百分点,沉降时间大大缩短,效率提高5倍,预期会产生良好的经济效益。

关键词丝胶;回收;单宁;沉降;冷冻;回收率中图分类号:TS195.2文献标志码:A 文章编号:1005-9350(2021)04-0043-03A new method for extracting sericin from silk fabric scouring solutionAbstract The silk fabric scouring solution from silk printing and dyeing plant is discharged to the sewage treatment plant without sericin protein extraction,which not only wastes resources but also increases the difficulty of subsequent sew-age treatment.Sericin possesses many excellent properties,which can be used in fabric finishing,cosmetics,food additives,functional biomaterials and so on.Therefore,it is in urgent need to develop a new recovery method which is efficient,sim-ple and easy to popularization.The extraction process was investigated in detail by using tannin precipitation method com-bined with freezing method under proper pH,and the optimal process was found pared with acid-precipitation method,the recovery rate increased 16%,the settling time was greatly shortened,and the efficiency increased by 5times,which was expected to produce good economic benefits.Key words sericin;recovery;tannin;sedimentation;freezing;recovery rate蚕丝织物精练液中丝胶蛋白提取的新方法收稿日期:2020-07-06基金项目:2019年淄博市重点研发计划(政策引导类项目2019ZC010106);丝胶废水资源化开发应用研究(2018年周村区校城融合项目)作者简介:肖俊梅(1964—),女,山东淄博市人,副教授,本科,主要从事污水处理研究,E-mail:*****************。

违约风险下银行住房抵押贷款预期回收率模型研究骆桦沈红梅(浙江理工大学理学院)【摘要】:住房按揭是商业银行贷款的主要组成部分,但由于房价的波动性下跌,容易造成借款者违约,从而使银行遭受损失。

本论文主要研究在违约风险条件下住房抵押贷款的预期回收率。

众所周知,住房价值影响违约事件的发生,我们基于结构模型框架研究预期银行回收率。

并且用数值方法分别分析了在贷款期限内不同时刻违约时的回收率,和不同贷款期限、违约成本、贷款额对预期回收率的影响。

关键词:违约风险;预期回收率;违约成本;结构模型中图分类号:F830.5 文献标识码:AThe Expected Recovery Rate Model Of Housing MortgageUnder The Risk Of DefaultLUO Hua SHEN Hong-mei(College of Science , Zhejiang Sci-Tech University , Hangzhou 30018, China)Abstract: Housing mortgage loans is the main loans of commercial banks. However, due to the house prices volatility plummeting, easily leads the borrower to default, so that the bank suffers huge losses. Our paper studies the excepted recovery rate model of housing mortgage under the risk of default. As it is known, the housing value impact on default event, we study the bank’s except ed recovery rate based on the framework of structure models. We also use numerical methods to analyze how the different loan time of maturity, default cost, amount of loans impact the recovery rate, and obtain the recovery rate when the lender defaults at different time.Key words: default risk; expect recovery rate; default cost; structure models0.引言住房抵押贷款是一种有效的住房消费信贷模式。

消费者通过将拟购住房产权抵押给银行,可以从银行获得一笔购房贷款。

近年来随着住房制度改革的深化和住房分配货币化的全面实施,个人住房抵押贷款已成为一种趋势,相关业务风险逐渐体现。

为促进个人住房贷款健康发展,有必要对已经显现或潜在的风险进行认真研究。

现存在着难以预测和控制的风险,如住房毁损风险、债务人信用风险、贷款条件风险、抵押物处理风险等。

而回收率是商业银行实施内部评级高级法的一个重要因素,是银行评量贷款的风险调整度量的重要指标,它是指债务人违约后资产的回收程度,可以估计出信用风险的严重程度。

本文获得基金:浙江省科技厅科研项目(编号2005C25011)和浙江理工大学教研项目资助,编号:114329B2A07022。

若借款者发生违约行为,则银行损失了贷款余额,取而代之的是获得借款者的住房所 有权。

一般在房地产价格下降到住房抵押贷款余额价值以下时会引发借款者的违约行为。

这时候银行就会考虑到一个回收率的问题,以便更好的估计现有资产的损失和价值。

1. 违约回收率的研究现状回收率的估计方法较多,主要包括历史数据平均法、非参数方法(如核密度估计法)、因素模型法、以及人工智能法等。

而常见的信用风险模型主要分为两大类:信用定价模型和信贷组合模型。

信用定价模型又可分为:结构模型和简约 模型。

许多信用风险管理软件中模型的设定都是基于结构模型的思想框架而改进的,如著名风险管理软件公司KMV 公司的产品。

简约模型就假设回收率是一个外生变量,Kamakura 公司就是简约模型的创立者和研究者。

常见的信贷组合模型有:JP 摩根的CreditMetrics 、瑞士信贷的CreditRisk+、麦肯锡公司的CreditPortfolioview 和KMV 公司的Credit Port —folioManager 。

Robert C Merton [1]在1974年发表的“On the Pricing of Corporate Debt: the Risk Structure of Interest Rate ”是现代信贷概率和回收率分析的理论基础文章。

在Merton 模型中将违约回收率隐含为随机,但不足之处是没有解决信用资产质量的实际观测问题。

Carty 和Lieberman [2](1996)以穆迪公司1989-1996年间58例优先担保违约应行贷款为对象,根据其次级市场交易价格进行实证研究,结果表明平均回收率为71%,中位数为77%,标准差为32%。

研究发现回收率明显向高端偏离。

Altman 和Brady [3]研究发现回收率和违约概率之间存在负相关关系。

总体来说目前的研究中对债券回收率的研究较多,对商业银行违约贷款回收率的研究较少,对零售贷款(如住房按揭和信用卡)或特殊贷款(如项目融资)回收率的研究更少。

所以本论文希望结合已有模型来研究有违约风险的住房抵押贷款回收率模型。

2. 预备知识——贷款余额计算目前个人住房贷款主要有两种还款方式[4,5]。

一是等额本息还款法,即在一定的期限内借款人每月以相等的金额偿还贷款本息,又称等额法,在贷款期间内,每个月的贷款偿付额是固定的。

二是等额本金法。

即在一定期限内借款人每月以等额偿还本金,贷款利息随本金递减,还款额逐月递减,因此又称递减法。

贷款余额()M t 根据等额本息还款法和等额本金还款法有两种计算方法: 等额本息还款法:(1)(1)1n n P i i A i ⨯⨯+=+-则在第t 期时的贷款余额为:()(1)[(1)*]M t M t A M t i =----(1)(1)i M t A =+--等额本金还款法:1(1)l P l A P i n n-=+-⨯⨯ 则在第t 期时的贷款余额为:()(1)[(1)*]l M t M t A M t i =----(1)(1)l i M t A =+--其中:A ——每月还本付息额,P ——初始贷款额,i ——贷款月利率,n ——按月计算的还款总期数。

以上每月还款额和贷款余额的定价法是在离散事件下的,为了以下模型的计算,我们主要考虑连续时间下的连续支付情形.设(0)M 为借款总额,首期付款额为L ,则(0)M 应为风险资产(0)H 与首期付款额之差,即(0)(0)M H L =-。

假定c 为固定月贷款利率,T 表示贷款期限,A 表示借款者每月还本付息额(假设为等额本息还款法),若看做连续支付,则t 时刻剩余贷款额()M t 满足以下常微分方程:()()dM t cM t dt Adt =- ()0M T =易得:(0)1cTcM A e-=- 解得:()(0)()(1)1c T t cTM M t e e---=--3. 住房抵押贷款预期回收率模型 3.1 基本假设(1)考虑连续时间的金融市场,时间区间[0,]T ,0表示现在,T 表示到期日;(2)市场是无套利的,可假设为有效的,无摩擦的,存在风险中性的鞅测度;(3)房产价格()H t 服从几何Brown 运动:()()()H H H t dH t q dt dW H t μσ=-+ (1) 由Iton 引理可知:21ln ()()2HH H H t H t q dt dW μσσ=--+对上式两边积分可得:21()(0)exp[()]2H t H t H q t μσ=--+其中H μ和H σ分别表示房价的瞬时漂移率和瞬时波动率,q 为住房服务收益系数(相当于同期住房租金,为住房价格的一定比例); (4)市场无风险利率为常数r ;(5)允许借款人在任意一个付款期内以抵押贷款的当前价值将住房出售给贷款机构,即违约可以发生在贷款发放和到期日之间的任何时间。

3.2 银行预期回收率如果在贷款期内,发生违约情况,期权持有人将房产权抵押给银行,银行有权将房屋出售以挽回因借款者违约引起的损失。

那么银行的预期回收价值是依赖于房价和贷款余额的,它可以分成两部分:在t 时刻,当()()H t M t >没有违约时,银行预期能收回贷款总额;当()()H t M t <时,龙海明等[6]发现借款者不会立即选择违约的,因为考虑到违约成本约束,包括信用等级降低、搬迁成本、房产变现交易成本等违约成本来看,借款者会慎重考虑是否违约,假设违约成本为k ,当()()H t k M t +<,借款者会选择理性违约。

这时银行预期能回收已付贷款额(0)()M M t -和房屋价值()H t 。

所以银行到期的回收价值为:()()()()()(0)[(0)()()]H t k M t H t k M t G t M I M M t H t I +>+<=⋅+-+⋅,其中{}A B I >表示式性函数:{}01A B if A B I ifA B><⎧=⎨>⎩则回收价值的贴现值为:()()()()E()[(0)[(0)()()]]H t k M t H t k M t G E M I M M t H t I +>+<=⋅+-+⋅我们在贷款初始时刻,若考虑违约因素下预测在t 时刻银行能回收的价值,则在违约条件下,预期回收价值为:()()[((0)()())][/]H t k M t E M M t H t I E G X PD+<-+⋅=其中X 表示借款者发生违约的条件。

违约概率为:()21()()(0)exp[()]()2H H H t PD P H t k M t P H q t M t k μσσ⎛⎫=+<=--+<- ⎪⎝⎭2()1ln ()()H H H t M t k q t P W N a μσ-⎛⎫--- ⎪ =<= ⎝⎭ 其中:2()1ln()H H M t k q t a μσ----=则借款者违约时银行预期回收率为:[/](0)E G X RR M =所以计算回收率我们关键是计算[/]E G X 。