中国翻译史(英文版详细)

- 格式:doc

- 大小:32.50 KB

- 文档页数:4

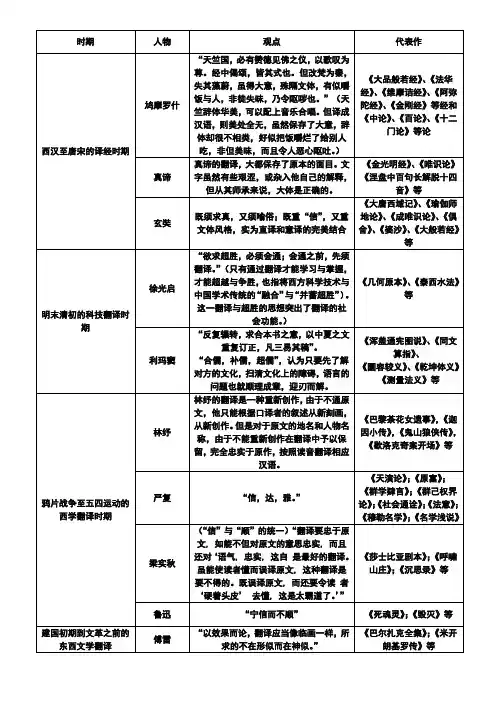

中国翻译史及其著名翻译家中国翻译发展史的五个历史时期•古代:汉隋唐宋的佛经翻译时期•明清之际的科学翻译时期•近代:清末民初的西学翻译时期(鸦片战争后~ “五四运动”前)•现代:“五四”以后的社会科学和文学翻译时期•当代:新中国成立后一、东汉~唐宋的佛经翻译Translation on Buddhism Scripture•中国翻译史上有“译经三大家”的说法•鸠摩罗什:他和弟子僧肇翻译了《金刚经》、《法华经》、《维摩经》、《中观论》和《百论》等共七十四部,三百八十四卷•真谛(印度佛教学者、梁武王)49《摄大乘论》•玄奘:唐高僧,俗称唐僧。

贞观二年(公元826年),玄奘去印度求经, 17年后回国,带回佛经657部。

玄奘主持了更大规模的译场,用19年时间译经75部1335卷。

此外,他还把老子著作的一部分译成梵语,是第一个把汉语著作介绍到国外去的中国人二、明末清初的科技翻译translation on science and technology•徐光启(1562-1633)(与利玛窦):《几何原本》•李之藻(1565-1630):“晓畅兵法,精于泰西之学”,与徐光启齐名。

•杨廷筠(1557—1627)与徐、李被称为中国天主教“三大柱石”三、鸦片战争后~ “五四运动”前Opium war~ May4th Movement•严复(最著名)信、达、雅•梁启超“通学、通文”•马建忠“善译”•林则徐•林纾:"译界之王"、“译才并世数严林”。

不懂外文,由别人在旁边口译,他边听边以古文写作;30多人协助他口译,译出包括英、美、法等十多国家的作品近200部。

四、“五四”~中华人民共和国成立May4th ~ foundation of P.R.C•鲁迅:“宁信而不顺” rather to be faithful than smooth•胡适、•林语堂:”忠实、通顺、美“ Moment in Peking《京华烟云》 My Country and My People《吾国与吾民》•茅盾、•郭沫若、•瞿秋白、•朱生豪、(1912~1944)是中国翻译莎士比亚作品较早和最多的一人“莎士比亚翻译第一人”《仲夏夜之梦》《威尼斯商人》,《第十二夜》等等•朱光潜•梁实秋 rather to be smooth than faithful五、新中国成立以后(当代)•新中国成立初期:环境特殊、“一边倒”苏联著作•“文革”时期:翻译、出版领域,基本上成为一片荒漠•改革开放以来:翻译出版事业蓬勃发展,形成中国翻译史上又一次(第四次)翻译高潮。

中国翻译史及重要翻译家08英本1 杨慧颖 NO.35中国翻译史上有许多为人们所熟知的大家,现就其翻译观点和主要作品做一简介:严复是中国近代翻译史上学贯中西、划时代意义的翻译家,也是我国首创完整翻译标准的先驱者。

严复吸收了中国古代佛经翻译思想的精髓,并结合自己的翻译实践经验,在《天演论》译例言里鲜明地提出了“信、达、雅”的翻译原则和标准。

“信”(faithfulness)是指忠实准确地传达原文的内容;“达”(expressiveness)指译文通顺流畅;“雅”(elegance)可解为译文有文才,文字典雅。

这条[1]著名的“三字经”对后世的翻译理论和实践的影响很大,20世纪的中国译者几乎没有不受这三个字影响的。

主要翻译作品:《救亡决论》,《直报》,1895年《天演论》,赫胥黎,1896年~1898年《原富》(即《国富论》),亚当·斯密,1901年《群学肄言》,斯宾塞,1903年《群己权界论》,约翰·穆勒,1903年《穆勒名学》,约翰·穆勒,1903年《社会通诠》,甄克斯,1903年《法意》(即《论法的精神》),孟德斯鸠,1904年~1909年《名学浅说》,耶方斯,1909年鲁迅鲁迅翻译观的变化,从早期跟随晚清风尚以意译为主,到后期追求直译、反对归化。

鲁迅的翻译思想主要是围绕"信"和"顺"问题展开的。

他"宁信而不顺"的硬译观在我国文坛上曾经引发过极大的争议。

鲁迅先生说过:凡是翻译,必须兼顾两面,一则当然力求其易解,一则是保存着原作的丰姿。

从实质上来讲,就是要使原文的内容、风格、笔锋、韵味在译文中得以再现。

翻译涉及原语(source language)与译语(target language) 两种语言及其文化背景等各方面的知识,有时非常复杂。

所以,译者要想收到理想的翻译效果,常常需要字斟句酌,反复推敲,仅仅懂得一些基本技巧知识是不够的,必须广泛涉猎不同文化间的差异,必须在两种语言上下工夫,乃至独具匠心。

英文版中国成语故事英文版中国故事,成语故事英文版精选,成语故事是历史的积淀,是几千年以来人民智慧的结晶。

成语故事翻译成英文的难度应该不小。

关于中国成语故事英文版,喜欢就一起看看吧!英文版中国成语故事1:滥竽充数during the warring states period (475-221bc), the king of the state of qi was very fond of listening to yu ensembles. he often got together 300 yu players to form a grand music.the king treated his musician very well. a man named nanguo heard about that and he managed to become a member of the band, even though he wan not good at playing the instrument at all.whenever the band played for the king, nanguo just stood in the line and pretended to play. nobody realized he was making no sound at all.as a result, he enjoyed his treatment just as the other musician did. when the king died, his son became the new ruler who also liked the music played on the yu.however, he preferred solos so that he ordered the musicians to play the yu one by one. therefore, nanguo had to run out of the palace.英文版中国成语故事2:偃旗息鼓In the Three Kingdoms Period, during a battle between Cao Cao and Liu Bei, the latter ordered his generals Zhao Yun and Huang Zhong to capture Cao Cao’s supplies.Cao Cao led a large force against Zhao Yun, who retreated as fas as the gates of his camp.There, he ordered that the banners be lowered and the war drums silenced, and that the camp gates be left wide open.Zhao Yun then stationed(安置,驻扎) his troops in ambush(埋伏) nearly. When Cao Cao arrived and saw the situation, he immediately suspected a trap and withdrew his forces.This idiom is nowadays used to indicate metaphorically(隐喻地) halting an attack or ceasing all activities.英文版中国成语故事3:破镜重圆in the northern and southern dynasties when the state of chen (a.d. 557-589) was facing its demise(死亡,终止) , xu deyan, husband of the princess, broke a bronze mirror into halves.each of them kept a half as tokens(代币,符号) in case they were separated. soon afterwards, they did lose touch with each other, but the two halves of the mirror enabled them to be reunited.this idiom is used to refer to the reunion of a couple after they lose touch or break up.成语故事是中国所特有的,总感觉翻译成英文的就变了味儿。

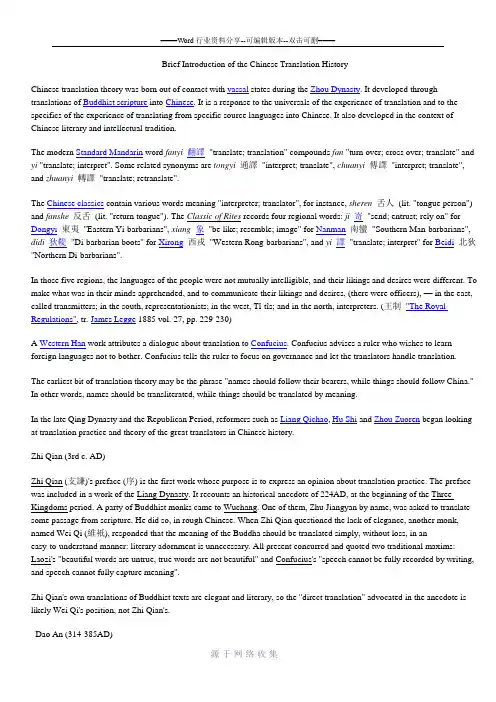

Brief Introduction of the Chinese Translation HistoryChinese translation theory was born out of contact with vassal states during the Zhou Dynasty. It developed through translations of Buddhist scripture into Chinese. It is a response to the universals of the experience of translation and to the specifics of the experience of translating from specific source languages into Chinese. It also developed in the context of Chinese literary and intellectual tradition.The modern Standard Mandarin word fanyi翻譯"translate; translation" compounds fan "turn over; cross over; translate" and yi "translate; interpret". Some related synonyms are tongyi通譯"interpret; translate", chuanyi傳譯"interpret; translate", and zhuanyi轉譯"translate; retranslate".The Chinese classics contain various words meaning "interpreter; translator", for instance, sheren舌人(lit. "tongue person") and fanshe反舌(lit. "return tongue"). The Classic of Rites records four regional words: ji寄"send; entrust; rely on" for Dongyi東夷"Eastern Yi-barbarians", xiang象"be like; resemble; image" for Nanman南蠻"Southern Man-barbarians", didi狄鞮"Di-barbarian boots" for Xirong西戎"Western Rong-barbarians", and yi譯"translate; interpret" for Beidi北狄"Northern Di-barbarians".In those five regions, the languages of the people were not mutually intelligible, and their likings and desires were different. To make what was in their minds apprehended, and to communicate their likings and desires, (there were officers), — in the east, called transmitters; in the south, representationists; in the west, Tî-tîs; and in the north, interpreters. (王制"The Royal Regulations", tr. James Legge 1885 vol. 27, pp. 229-230)A Western Han work attributes a dialogue about translation to Confucius. Confucius advises a ruler who wishes to learn foreign languages not to bother. Confucius tells the ruler to focus on governance and let the translators handle translation.The earliest bit of translation theory may be the phrase "names should follow their bearers, while things should follow China." In other words, names should be transliterated, while things should be translated by meaning.In the late Qing Dynasty and the Republican Period, reformers such as Liang Qichao, Hu Shi and Zhou Zuoren began looking at translation practice and theory of the great translators in Chinese history.Zhi Qian (3rd c. AD)Zhi Qian (支謙)'s preface (序) is the first work whose purpose is to express an opinion about translation practice. The preface was included in a work of the Liang Dynasty. It recounts an historical anecdote of 224AD, at the beginning of the Three Kingdoms period. A party of Buddhist monks came to Wuchang. One of them, Zhu Jiangyan by name, was asked to translate some passage from scripture. He did so, in rough Chinese. When Zhi Qian questioned the lack of elegance, another monk, named Wei Qi (維衹), responded that the meaning of the Buddha should be translated simply, without loss, in aneasy-to-understand manner: literary adornment is unnecessary. All present concurred and quoted two traditional maxims: Laozi's "beautiful words are untrue, true words are not beautiful" and Confucius's "speech cannot be fully recorded by writing, and speech cannot fully capture meaning".Zhi Qian's own translations of Buddhist texts are elegant and literary, so the "direct translation" advocated in the anecdote is likely Wei Qi's position, not Zhi Qian's.Dao An (314-385AD)Dao An focused on loss in translation. His theory is the Five Forms of Loss (五失本):1.Changing the word order. Sanskrit word order is free with a tendency to SOV. Chinese is SVO.2.Adding literary embellishment where the original is in plain style.3.Eliminating repetitiveness in argumentation and panegyric (頌文).4.Cutting the concluding summary section (義說).5.Cutting the recapitulative material in introductory section.Dao An criticized other translators for loss in translation, asking: how they would feel if a translator cut the boring bits out of classics like the Shi Jing or the Classic of History?He also expanded upon the difficulty of translation, with his theory of the Three Difficulties (三不易):municating the Dharma to a different audience from the one the Buddha addressed.2.Translating the words of a saint.3.Translating texts which have been painstakingly composed by generations of disciples.Kumarajiva (344-413AD)Kumarajiva’s translation practice was to translate for meaning. The story goes that one day Kumarajiva criticized his disciple Sengrui for translating “heaven sees man, and man sees heaven” (天見人,人見天). Kumarajiva felt that “man and heaven connect, the two able to see each other” (人天交接,兩得相見) would be more idiomatic, though heaven sees man, man sees heaven is perfectly idiomatic.In another tale, Kumarajiva discusses the problem of translating incantations at the end of sutras. In the original there is attention to aesthetics, but the sense of beauty and the literary form (dependent on the particularities of Sanskrit) are lost in translation. It is like chewing up rice and feeding it to people (嚼飯與人).Huiyuan (334-416AD)Huiyuan's theory of translation is middling, in a positive sense. It is a synthesis that avoids extremes of elegant (文雅) and plain (質樸). With elegant translation, "the language goes beyond the meaning" (文過其意) of the original. With plain translation, "the thought surpasses the wording" (理勝其辭). For Huiyuan, "the words should not harm the meaning" (文不害意). A good translator should “strive to preserve the original” (務存其本).Sengrui (371-438AD)Sengrui investigated problems in translating the names of things. This is of course an important traditional concern whose locus classicus is the Confucian exhortation to “rectify names” (正名). This is not merely of academic concern to Sengrui, for poor translation imperils Buddhism. Sengrui was critical of his teacher Kumarajiva's casual approach to translating names, attributing it to Kumarajiva's lack of familiarity with the Chinese tradition of linking names to essences (名實).Sengyou (445-518AD)Much of the early material of earlier translators was gathered by Sengyou and would have been lost but for him. Sengyou’s approach to translation resembles Huiyuan's, in that both saw good translation as the middle way between elegance and plainness. However, unlike Huiyuan Sengyou expressed admiration for Kumarajiva’s elegant translations.Xuanzang (600-664AD)Xuanzang’s theory is the Five Untranslatables (五種不翻), or five instances where one should transliterate:1.Secrets: Dharani 陀羅尼, Sanskrit ritual speech or incantations, which includes mantras.2.Polysemy: bhaga (as in the Bhagavad Gita) 薄伽, which means comfortable, flourishing, dignity, name, lucky,esteemed.3.None in China: jambu tree 閻浮樹, which does not grow in China.4.Deference to the past: the translation for anuttara-samyak-sambodhi is already established as Anouputi 阿耨菩提.5.To inspire respect and righteousness: Prajna 般若instead of “wisdom” (智慧).Daoxuan (596-667AD)Yan Fu (1898)Yan Fu is famous for his theory of fidelity, clarity and elegance (信達雅), which some believe originated with Tytler. Yan Fu wrote that fidelity is difficult to begin with. Only once the translator has achieved fidelity and clarity should he attend to elegance. The obvious criticism of this theory is that it implies that inelegant originals should be translated elegantly. Clearly, if the style of the original is not elegant or refined, the style of the translation should not be elegant either.Liang Qichao (1920)Liang Qichao put these three qualities of a translation in the same order, fidelity first, then clarity, and only then elegance.Lin Yutang (1933)Lin Yutang stressed the responsibility of the translator to the original, to the reader, and to art. To fulfill this responsibility, the translator needs to meet standards of fidelity (忠實), smoothness (通順) and beauty.Lu Xun (1935)Lu Xun's most famous dictim relating to translation is "I'd rather be faithful than smooth" (寧信而不順).Ai Siqi (1937)Ai Siqi described the relationships between fidelity, clarity and elegance in terms of Western ontology, where clarity and elegance are to fidelity as qualities are to being.Zhou Zuoren (1944)Zhou Zuoren assigned weightings, 50% of translation is fidelity, 30% is clarity, and 20% elegance.Zhu Guangqian (1944)Zhu Guangqian wrote that fidelity in translation is the root which you can strive to approach but never reach. This formulation perhaps invokes the traditional idea of returning to the root in Daoist philosophy.Fu Lei (1951)Fu Lei held that translation is like painting: what is essential is not formal resemblance but rather spiritual resemblance (神似).Qian Zhongshu (1964)Qian Zhongshu wrote that the highest standard of translation is transformation (化, the power of transformation in nature): bodies are sloughed off, but the spirit (精神), appearance and manner (姿致) are the same as before (故我, the old me or the ol。

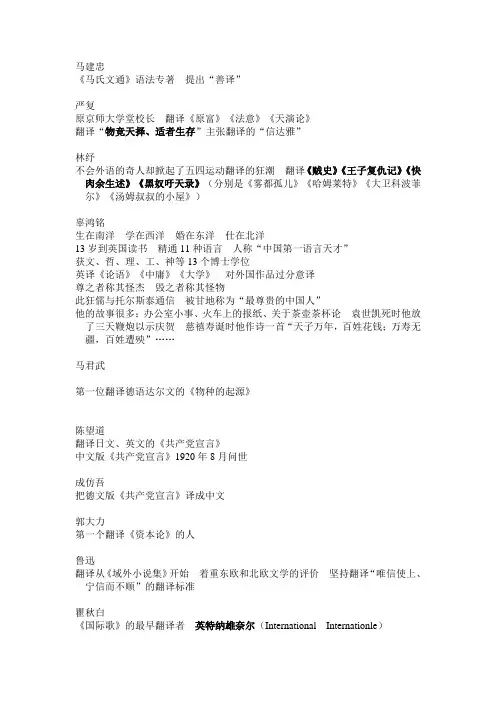

马建忠《马氏文通》语法专著提出“善译”严复原京师大学堂校长翻译《原富》《法意》《天演论》翻译“物竞天择、适者生存”主张翻译的“信达雅”林纾不会外语的奇人却掀起了五四运动翻译的狂潮翻译《贼史》《王子复仇记》《快肉余生述》《黑奴吁天录》(分别是《雾都孤儿》《哈姆莱特》《大卫科波菲尔》《汤姆叔叔的小屋》)辜鸿铭生在南洋学在西洋婚在东洋仕在北洋13岁到英国读书精通11种语言人称“中国第一语言天才”获文、哲、理、工、神等13个博士学位英译《论语》《中庸》《大学》对外国作品过分意译尊之者称其怪杰毁之者称其怪物此狂儒与托尔斯泰通信被甘地称为“最尊贵的中国人”他的故事很多:办公室小事、火车上的报纸、关于茶壶茶杯论袁世凯死时他放了三天鞭炮以示庆贺慈禧寿诞时他作诗一首“天子万年,百姓花钱;万寿无疆,百姓遭殃”……马君武第一位翻译德语达尔文的《物种的起源》陈望道翻译日文、英文的《共产党宣言》中文版《共产党宣言》1920年8月问世成仿吾把德文版《共产党宣言》译成中文郭大力第一个翻译《资本论》的人鲁迅翻译从《域外小说集》开始着重东欧和北欧文学的评价坚持翻译“唯信使上、宁信而不顺”的翻译标准瞿秋白《国际歌》的最早翻译者英特纳雄奈尔(International Internationle)郭沫若翻译《少年维特之烦恼》认为“写作即处女、翻译即媒婆”赵景深戏曲学家、教育家翻译安徒生的《皇帝的新衣》1922年翻译契诃夫的《万卡》把“The Milky Way”翻译成“牛奶路”朱生豪翻译大家《莎士比亚戏剧全集》的第一个翻译者而且翻译的层次相当高莎翁37个剧本145首长诗朱生豪共译31个剧本1936.8.8 传奇剧《暴风雨》是他的第一部译品曹静华主搞苏俄文学翻译张谷若翻译应该文学大师托马斯的《德伯家的苔丝》《还乡》《无名的裘德》前两者最著名他提倡“以地道的译文翻译地道的原文”苏曼殊和尚第一个以古体诗形式翻译拜伦的诗翻译雨果的《悲惨的世界》钱稻孙将但丁的《神曲》一、二、三曲译为骚体刘半农其弟是刘天华《皇帝的新装》是刘半农最早翻译介绍给中国读者的翻译《茶花女》剧本第一个吧苏联作品介绍给中国人巴金翻译《前夜》等傅雷主译法语著作翻译主张“神似说”形成“傅雷体华文语言”文革中夫妇同是自杀萧乾二战时战地记者在联合国成立大会、波茨坦公约会议等上以记者的身份出现与夫人文浩耗五年翻译现代派意识流巨著《尤利西斯》钱钟书1935年以全国第一名成绩考取英国庚子赔款公费留学生主张“化境说”翻译即“原作向译文的投胎转世”夫人杨绛翻译《堂吉诃德》等妹杨必翻译《名利场》卞之琳诗人、翻译家徐志摩的学生1936年翻译《西窗集》翻译《莎士比亚悲剧四种》著名翻译《Hamlet》monolog“to be or not to be”叶君健最早有系统地将安徒生童话引入中国的文艺先锋冰心第一部译品是纪伯伦的散文诗《先知》季羡林主译吐火罗文和梵文杨宪益与妻子戴乃迭合译《离骚》《史记选》《红楼梦》《儒林外史》《长生殿》《牡丹亭》《唐宋诗歌散文选》《白毛女》《老残游记》等张健上学时翻译《格列夫游记》翻译《间谍》《埋伏着的敌人》《莎士比亚和他的四个悲剧》傅东华翻译《飘》的电视台词翻译《红字》《琥珀》《山胡桃集》散文集主张翻译外国作品用本土名字李霁野翻译《简爱自传》翻译技巧相当好伍光健翻译《孤女飘零记》《侠隐记》(即《简爱》《三个火枪手》)翻译的作品很优美许渊冲主张翻译“美化之艺术、创优似竞赛”王佐良翻译弗朗西斯培根的《论读书》。

《中国翻译史》课程教学大纲一、教师或教学团队信息二、课程基本信息课程名称(中文):中国翻译史课程名称(英文):A Brief History of Translation in China课程类别:□通识必修课□通识选修课□专业必修课□专业方向课专业拓展课□实践性环节课程性质*:□学术知识性□方法技能性 研究探索性□实践体验性课程代码:04604141周学时:2 总学时:32 学分: 2先修课程:翻译基础授课对象:英语,英语师范三、课程简介本课程为英语及英语师范专业高年级文化通识课程。

以中国历史上的四次主要翻译期(即东汉至唐代的佛经翻译、明清传教士科技翻译、晚清哲社著作翻译、民国文学翻译)为主线,从宗教典籍、知识传播、民族语的形成、文化价值传递等角度,为学生呈现翻译活动丰富的历史面貌。

此外,还选取具有代表性的汉藉外译个案,让学生了解中国名著在国外的译介情况,并赏析部分名著的翻译片段。

课程有助于提升高年级学生文化素养,开阔翻译视界,深化对翻译的理解,同时也可以有效地启发学生思考当下的语言、文化交际及翻译行为与历史的关系。

四、课程目标使学生了解中国翻译史的发展脉络,知道中西文化交流史重大事件和人物,赏析汉译典籍中的名篇名段,以史鉴今,更好地反思当下全球化,职业化时代的语言文化与交际行为。

五、教学内容与进度安排*六、修读要求(满足对应课程标准的第3条)学生务必严于律己,遵守校规,不迟到,不早退,不旷课,特殊情况必须请假说明。

课内学生务必积极思考问题,认真分析问题,主动回答问题。

课内进行各种形式的互动活动。

要求:学生分组选择主题做课堂展示并参与讨论。

每次课后会推荐中西文化交流史相关参考书目,根据个人兴趣选择阅读。

每人至少精读两本,并提交读书报告。

七、学习评价方案(满足对应课程标准的第4、5、6条)1、闭卷考试:70%2、平时成绩:30%10分为出勤,每缺一次扣2分20分为参与presentation、课堂讨论与课外阅读情况。

中国翻译史的发展及其对当今译学的启示:One can know the alteration of the society by viewing itshistory. After long years of development, Chinese tanslation hasaccumulated its special features and essence. Looking back, therewas so much for us to learn and to think over. Therefore, thestudyof its history could leave people very important implication.翻译作为一门独立的学科发展到现在,已经拥有了一套完整的理论和体系。

而其发展的过程可谓是漫长而曲折。

对于翻译的原则,理论,方法,技巧,译学界曾有过无数次的讨论,而正是这些争论绵延不休的推动着翻译这一门学科的发展。

而俗话说:以史为鉴。

翻阅漫长历史,回顾翻译这门学科所走过的痕迹,给当今留下许多启示。

1、翻译史研究的重要性俗话说,以史为鉴可以知兴替。

对于任何一门学科而言,其发展与进步都离不开回顾和反思。

翻译史的研究对于译学状况的掌握和反思起着举足轻重的作用。

翻译史大致可以分为翻译实践史和翻译理论史。

前者注重具体的翻译作品的探索与研究,后者注重翻译理论的提炼与创新。

20 世纪中期,人们逐渐开始重视对于翻译资料的整理与收集,并且在此基础上进行回顾与反思。

张岂之教授认为 , 传统文化的研究需要有一个突破 , 就必须研究前人在此问题上的经验和不足 , 而学术史的研究恰好具有这样的功能。

首先,对于翻译历史的研究在一定程度上奠定了翻译学成为一门独立学科的基础。

从历史的角度来看,翻译活动无论在中国还是在西方都有着相当长的历史,在上千年的翻译活动中人们积累了十分丰富的经验,这些内容对于任何一门学科来说都是十分宝贵和不可或缺的。

24史英文版

《二十四史》的英文版(Twenty-Four Histories)是《二十四史》的英译本,由多位英国、美国、加拿大等几个国家的汉学家组织翻译,中国大陆和台湾的一些专家也参与了翻译工作。

英文版《二十四史》的翻译工程共耗时15年,包括《史记》、《汉书》、《后汉书》、《三国志》、《晋书》、《宋书》、《南齐书》、《梁书》、《陈书》、《魏书》、《北齐书》、《周书》、《隋书》、《南史》、《北史》、《新唐书》、《新五代史》、《宋史》、《辽史》、《金史》和《元史》。

由于《二十四史》的内容十分丰富,翻译难度很大,参与翻译工作的汉学家和历史学家付出了艰辛的努力。

英文版《二十四史》的出版对于推动中国历史和文化在国际上的传播和交流具有重要意义,有助于让更多的人了解和认识中国历史和文化,促进中外文化交流和相互理解。

1 中国历史朝代英文翻译A Brief Chinese Chronology夏Xia DynastyC.2100-C.1600 B.C.商Shang DynastyC.1600-C.1100 B.C.周Zhou Dynasty-西周Western Zhou DynastyC.1100-771 B.C. -东周Eastern Zhou dynasty770-256 B.C.-春秋Spring and Autumn period770-476 B.C. -战国Warring States475-221 B.C.秦Qin Dynasty221-206 B.C.汉Han Dynasty-西汉Western Han206 B.C.-24 A.D.-东汉Eastern Han25-220 A.D.三国Three Kingdoms-魏Wei220-265-蜀汉Shu Han221-263吴Wu222-280西晋Western Jin Dynasty265-316东晋Eastern Jin Dynasty317-420南北朝Northern and Southern Dynasty-南朝Southern Dynasty--宋Song420-479--齐Qi479-502--梁Liang502-557--陈Chen557-589-北朝Northern Dynasty--北魏Northern Wei386-534--东魏Eastern Wei534-550--北齐Northern Qi550-577--西魏Western Wei535-556--北周Northern Zhou557-581隋Sui Dynasty581-618唐Tang Dynasty618-907五代Five Dynasties-后梁Later Liang907-923-后唐Later Tang923-936-后晋Later Jin936-946-后汉Later Han947-950-后周Later Zhou951-960宋Song Dynasty-北宋Northern Song Dynasty960-1127-南宋Southern Song Dynasty1127-1279辽Liao Dynasty916-1125金Jin Dynasty1115-1234元Yuan Dynasty1271-1368明Ming Dynasty1368-1644清Qing Dynasty1644-1911中华民国Republic of China1912-1949中华人民共和国People’s Republic of China1949-*C.:Century 世纪B.C.:Before Christ 公元前A.D.:Anno Domini 公元abbrabbreviation(略)略语adj, adjjadjective(s)(形)形容词adv, advvadverb(s)(副)副词adv partadverbial particle(副接)副词接语auxauxiliary(助)助动词[C]countable noun(可数)可数名词conjconjunction(连)连接def art definite article(定冠)定冠词egfor example(例如)例如espespecially(尤指)尤指etcand the others(等)等等iewhich is to say(意即)意即indef artindefinite article(不定冠词)不定冠词infinfinitive(不定词)不定词intinterjection(感)感叹词nnoun(s) (名)名词negnegative(ly)(否定)否定的(地)part adjparticipial adjective(分形)分词形容词persperson(人称)人称pers pronpersonal pronoun(人称代)人称代名词plplural(复)复数(的)pppast participle (过去分词)过去分词prefprefix(字首)字首preppreposition(al) (介词)介词,介系词,介词的pronpronoun (代)代名词ptpast tense(过去)过去式sbsomebody(某人)某人singsingular(单)单数(的)sthsomething(某事物)某物或某事suffsuffix(字尾)字尾[U]uncountable noun(不可数)不可数名词USAmerica(n)(美)美国(的)vverb(s) (动)动词。

Brief Introduction of the Chinese Translation HistoryChinese translation theory was born out of contact with states during the . It developed through translations of into . It is a response to the universals of the experience of translation and to the specifics of the experience of translating from specific source languages into Chinese. It also developed in the context of Chinese literary and intellectual tradition.The modern word fanyi"translate; translation" compounds fan "turn over; cross over; translate" and yi "translate; interpret". Some related synonyms are tongyi通譯"interpret; translate", chuanyi傳譯"interpret; translate", and zhuanyi轉譯"translate; retranslate".The contain various words meaning "interpreter; translator", for instance, sheren舌人(lit. "tongue person") and fanshe反舌(lit. "return tongue"). The records four regional words: ji"send; entrust; rely on" for 東夷"Eastern Yi-barbarians", xiang"be like; resemble; image" for 南蠻"Southern Man-barbarians", didi"Di-barbarian boots" for 西戎"Western Rong-barbarians", and yi"translate; interpret" for 北狄"Northern Di-barbarians".In those five regions, the languages of the people were not mutually intelligible, and their likings and desires were different. To make what was in their minds apprehended, and to communicate their likings and desires, (there were officers), — in the east, called transmitters; in the south, representationists; in the west, Tî-tîs; and in the north, interpreters. (王制, tr. 1885 vol. 27, pp. 229-230)A work attributes a dialogue about translation to . Confucius advises a ruler who wishes to learn foreign languages not to bother. Confucius tells the ruler to focus on governance and let the translators handle translation.The earliest bit of translation theory may be the phrase "names should follow their bearers, while things should follow China." In other words, names should be transliterated, while things should be translated by meaning.In the late Qing Dynasty and the Republican Period, reformers such as , and began looking at translation practice and theory of the great translators in Chinese history.Zhi Qian (3rd c. AD)(支謙)'s preface (序) is the first work whose purpose is to express an opinion about translation practice. The preface was included in a work of the . It recounts an historical anecdote of 224AD, at the beginning of the period. A party of Buddhist monks came to . One of them, Zhu Jiangyan by name, was asked to translate some passage from scripture. He did so, in rough Chinese. When Zhi Qian questioned the lack of elegance, another monk, named Wei Qi (維衹), responded that the meaning of the Buddha should be translated simply, without loss, in an easy-to-understand manner: literary adornment is unnecessary. All present concurred and quoted two traditional maxims: 's "beautiful words are untrue, true words are not beautiful" and 's "speech cannot be fully recorded by writing, and speech cannot fully capture meaning".Zhi Qian's own translations of Buddhist texts are elegant and literary, so the "direct translation" advocated in the anecdote is likely Wei Qi's position, not Zhi Qian's.Dao An (314-385AD)focused on loss in translation. His theory is the Five Forms of Loss (五失本):1.Changing the . word order is free with a tendency to . Chinese is .2.Adding literary embellishment where the original is in plain style.3.Eliminating repetitiveness in argumentation and panegyric (頌文).4.Cutting the concluding summary section (義說).5.Cutting the recapitulative material in introductory section.Dao An criticized other translators for loss in translation, asking: how they would feel if a translator cut the boring bits out of classics like the or the ?He also expanded upon the difficulty of translation, with his theory of the Three Difficulties (三不易):municating the to a different audience from the one the Buddha addressed.2.Translating the words of a saint.3.Translating texts which have been painstakingly composed by generations of disciples.Kumarajiva (344-413AD)’s translation practice was to translate for meaning. The story goes that one day Kumarajiva criticized his disciple for translating “heaven sees man, and man sees heaven” (天見人,人見天). Kumarajiva felt that “man and heaven connect, the two able to see each other” (人天交接,兩得相見) would be more idiomatic, though heaven sees man, man sees heaven is perfectly idiomatic.In another tale, Kumarajiva discusses the problem of translating incantations at the end of sutras. In the original there is attention to aesthetics, but the sense of beauty and the literary form (dependent on the particularities of Sanskrit) are lost in translation. It is like chewing up rice and feeding it to people (嚼飯與人).Huiyuan (334-416AD)'s theory of translation is middling, in a positive sense. It is a synthesis that avoids extremes of elegant (文雅) and plain (質樸). With elegant translation, "the language goes beyond the meaning" (文過其意) of the original. With plain translation, "the thought surpasses the wording" (理勝其辭). For Huiyuan, "the words should not harm the meaning" (文不害意). A goo d translator should “strive to preserve the original” (務存其本).Sengrui (371-438AD)investigated problems in translating the names of things. This is of course an important traditional concern whose locus classicus is the exhortation to “rectify names” (正名). This is not merely of academic concern to Sengrui, for poor translation imperils Buddhism. Sengrui was critical of his teacher 's casual approach to translating names, attributing it to Kumarajiva's lack of familiarity with the Chinese tradition of linking names to essences (名實).Sengyou (445-518AD)Much of the early material of earlier translators was gathered by and would have been lost but for him. Sengyou’s approach to translation resembles Huiyuan's, in that both saw good translation as the middl e way between elegance and plainness. However, unlike Huiyuan Sengyou expressed admiration for Kumarajiva’s elegant translations.Xuanzang (600-664AD)’s theory is the Five Untranslatables (五種不翻), or five instances where one should transliterate:1.Secrets: 陀羅尼, Sanskrit ritual speech or incantations, which includes .2.: bhaga (as in the ) 薄伽, which means comfortable, flourishing, dignity, name, lucky, esteemed.3.None in China: tree 閻浮樹, which does not grow in China.4.Deference to the past: the translation for anuttara-samyak-sambodhi is already established asAnouputi 阿耨菩提.5.To inspire respect and righteousness: 般若instead of “wisdom” (智慧).Daoxuan (596-667AD)Yan Fu (1898)is famous for his theory of fidelity, clarity and elegance (信達雅), which some believe originated with . Yan Fu wrote that fidelity is difficult to begin with. Only once the translator has achieved fidelity and clarity should he attend to elegance. The obvious criticism of this theory is that it implies that inelegant originals should be translated elegantly. Clearly, if the style of the original is not elegant or refined, the style of the translation should not be elegant either.Liang Qichao (1920)put these three qualities of a translation in the same order, fidelity first, then clarity, and only then elegance.Lin Yutang (1933)stressed the responsibility of the translator to the original, to the reader, and to art. To fulfill this responsibility, the translator needs to meet standards of fidelity (忠實), smoothness (通順) and beauty.Lu Xun (1935)'s most famous dictim relating to translation is "I'd rather be faithful than smooth" (寧信而不順).Ai Siqi (1937)described the relationships between fidelity, clarity and elegance in terms of Western , where clarity and elegance are to fidelity as qualities are to .Zhou Zuoren (1944)assigned weightings, 50% of translation is fidelity, 30% is clarity, and 20% elegance.Zhu Guangqian (1944)wrote that fidelity in translation is the root which you can strive to approach but never reach. This formulation perhaps invokes the traditional idea of returning to the root in philosophy.Fu Lei (1951)held that translation is like painting: what is essential is not formal resemblance but rather spiritual resemblance (神似).Qian Zhongshu (1964)wrote that the highest standard of translation is transformation (化, the power of transformation in nature): bodies are sloughed off, but the spirit (精神), appearance and manner (姿致) are the same as before (故我, the old me or the ol。