090110717 董琳 The Results of Oil Price’s Increase

- 格式:doc

- 大小:24.00 KB

- 文档页数:1

2018年考研英语阅读材料之油价下跌是赚是赔Cheaper oil油价下跌Winners and losers赚了还是赔了?America and its friends benefit from falling oil prices;its most strident critics don't美国及其盟友将从油价下跌中获益;最为毒舌的批评者们却不能如此IN EARL Y October the IMF looked at what might happen to the world economy if conflict in Iraqcaused an oil-price shock. Fighters from Islamic State (IS) were pushing into the country'snorth and the fund worried about a sharp price rise, of 20% in a year. Global GDP would fall by0.5-1.5%, it concluded. Equity prices in rich countries would decline by 3-7%, and inflationwould be at least half a point higher.十月初,国际货币基金组织(IMF)预估了一旦伊拉克冲突导致油价震荡会带来怎样的后果。

伊斯兰国(IS)的武装分子在向该国北部进军时,IMF担心今年油价可能会猛增约20%。

它还估计今年全球GDP增速可能会下滑0.5%至1.5%。

富裕国家的股价跌幅可能会达到3%至7%,而通胀率可能至少会上浮0.5个百分点。

IS is still advancing.Russia, the world's third-biggest producer, is embroiledinUkraine.Iraq,Syria,Nigeria and Libya, oil producers all, are in turmoil. But the price of Brentcrude fell over 25% from 115 abarrel in mid-June to under 85 inmid-October, before recoveringa little. Such a shift has global consequences. Who are the winners and losers?IS仍在继续进军。

内部控制英文文献目录1. 内部控制管制对盈余质量的影响:来自德国的证据( March 2008 )The effect of internal control regulation on earnings quality: Evidence from Germany2. 内部控制制度如何影响财务报告?( Altamuro ,June 24, 2009)How Does Internal Control Regulation Affect Financial Reporting3. 财务报告内部控制缺陷的决定因素( Doyle ,May 15, 2006)Determinants of weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting4. 应计质量与财务报告内部控制( Doyle,January 24, 2007)Accruals Quality and Internal Control over Financial Reporting5. SOX 内部控制缺陷对公司风险与权益资本成本的影响( Ashbaugh-Skaife ,June 10, 2008) The Effect of SOX Internal Control Deficiencies on Firm Risk and Cost of Equity6. 审计委员会质量、审计师独立性与内部控制缺陷( Zhang)Audit Committee Quality, Auditor Independence, and Internal Control Weaknesses7. 小企业受益于内部控制缺陷审计师认证吗Do Small Firms Benefit from Auditor Attestation of Internal Control Effectiveness8. 内部控制缺陷的决定因素( Jahmani)Determinants of Internal Control Weaknesses In Accelerated Filers9. 操控性应计项目能帮助区分内部控制缺陷和欺诈吗Do Discretionary Accruals Help Distinguish between Internal Control Weaknesses and Fraud10. 财务报告质量对债务契约的影响:来自内部控制缺陷报告的证据 ( Costello ,September 4, 2010) The impact of financial reporting quality on debt contracting: Evidence from internal control weakness reports11. 重大内部控制缺陷与盈余管理Material Internal Control Weaknesses and Earnings Management in the Post-SOX Environment12. 家族企业的内部控制( April 2013 )Internal Controls in Family-Owned Firms ()13. 内部控制质量对企业并购绩效的影响研究Study on the Impact of the Quality of Internal Control on the Performance of M&A14. 内部控制质量与信用违约互换利差( January 2014)Internal Control Quality and Credit Default Swap Spreads15. 家族企业内部控制:特征和后果Internal Control in Family Firms: Characteristics and Consequences16. 内部控制报告与会计信息质量:洞察”遵守或解释的“内部控制制度Internal control reporting and accounting quality :Insight "comply-or-explain" internal control regime17. 内部控制报告与会计稳健性Internal Control Reporting and Accounting Conservatism18. 会计信息质量影响产品市场契约吗?来自政府合同授予的证据( March 2014 )Does Accounting Quality Influence Product Market Contracting? Evidence from Government Contract Awards19. 公司特征与财务报告质量:尼日利亚制造业上市公司的证据20. 内部控制情况与专家审计师选择The Association between Internal Control Situations and Specialist Auditor Choices21. 审计费用反应了控制风险的风险溢价吗( 2013-07 )Do Audit Fees Reflect Risk Premiums for Control Risk?22. 内部控制质量与审计定价Internal Control Quality and Audit Pricing under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act23. 内部控制缺陷与权益资本成本:来自萨班斯法案404 节披露的证据Internal Control Weakness and Cost of Equity: Evidence from SOX Section 404 Disclosures24. 内部控制缺陷与信息不确定性Internal Control Weaknesses and Information Uncertainty25. 重大内部控制缺陷与股票价格崩溃危险:来自404 条款披露的证据( May 2013 )Material Weaknessin Internal Control and Stock Price Crash Risk: Evidence from SOX Section 404 Disclosure 26. SOX 内部控制缺陷对公司风险与权益资本成本的影响The Effect of SOX Internal Control Deficiencies on Firm Risk and Cost of Equity27. 信用评级、债务成本与内部控制信息披露:SOX302 和SOX404 法的比较28. 萨班斯-奥克斯利法案对会计信息债务契约价值的影响The Effect of Sarbanes-Oxley on the Debt Contracting Value of Accounting Information29. 财务报告内部控制的不利意见与审计师解聘/辞职Adverse Internal Control over Financial Reporting Opinions and Auditor Dismissals/Resignations30. 新管理人员任命与随后的SOX 法案404 的意见Appointment of New Executives and Subsequent SOX 404 Opinion31. 萨班斯奥克斯利:有关萨班斯法案404 影响的证据Sarbanes-Oxley: The Evidence Regarding the Impact of Sox 40432. 内部控制有效性自愿披露的经济决定因素及后果:从首次公开发行的证据( March 2013 ) Economic Determinants and Consequences of Voluntary Disclosure of Internal Control Effectiveness: Evidence from Initial Public Offerings33. 非营利组织中内部控制问题的原因和后果The Causes and Consequences of Internal Control Problems in Nonprofit Organizations34. SOX 内部控制披露在公司控制权市场中的价值The Value of SOX Internal Control Disclosures in the Market for Corporate Control35. 内部控制缺陷与销售、一般的及行政费用的非对称性行为Internal Control Weakness and the Asymmetrical Behavior of Selling, General, and Administrative Costs36. 内部控制缺陷及补救措施披露对投资者感知的盈余质量的影响The Impact of Disclosures of Internal Control Weaknesses and Remediation on Investor-Perceived Earnings Quality37. 内部控制缺陷与美国上市的中国公司与美国公司的审计师SOX Internal Control Deficiencies and Auditors of U.S.-Listed Chinese versus U.S. Firms38. 内部控制信息披露与代理成本—来自瑞士的非金融类上市公司的证据( January 2013) Internal Control Disclosure and Agency Costs Evidence from Swiss listed non-financial Companies39. 萨班斯奥克斯利法案与公司投资:来自自然实验的新证据The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and Corporate Investment: New Evidence from a Natural Experiment40. 国内投资者保护、所有权结构与交叉上市公司遵守SOX 要求披露内部控制缺陷Home Country Investor Protection, Ownership Structure and Cross-Listed Firms 'Compliance with SOX-Mandated Internal Control Deficiency Disclosure41. 审计师对披露重大缺陷相关风险的看法Auditors ' Percenpsti o f the Risks Associated with Disclosing Material Weaknesses42. 交叉上市公司提供与美国公司相同质量的披露?来自萨班斯-奥克斯利法案302 条款下的内部控制缺陷信息披露的证据Do cross-listed firms provide the same quality disclosure as U.S. firms? Evidence from the internal control deficiency disclosure under Section 302 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act43. 内部控制缺陷与并购绩效Internal Control Weaknesses and Acquisition Performance44. 萨班斯-奥克斯利法案302 条款下的内部控制缺陷对审计费用的影响The Effect of Internal Control Weakness under Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act on Audit Fees45. 审计师对财务报告内部控制的评价对审计费用、债务成本及净遵从收益The Effect of Auditors ' Assessment of Internal Control of over Financial Reporting on Audit Fees, Cost of Debt and Net Compliance Benefit46. 上市公司披露的信息含量与萨班斯-奥克斯利法案Information Content of Public Firm Disclosures and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act47. 财务错报与股票市场的契约:从增发的证据Financial Misstatements and Contracting in the Equity Market: Evidence from Seasoned Equity Offerings48. 公司治理质量与SOX 302 条款下内部控制报告Corporate Governance Quality and Internal Control Reporting Under Sox Section 30249. 审计委员会质量、审计师独立性与内部控制缺陷Audit Committee Quality, Auditor Independence, and Internal Control Weaknesses50. SOX404 条款的影响:成本,盈余质量与股票价格The Effect of SOX Section 404: Costs, Earnings Quality, and Stock Prices51. 内部控制缺陷与银行贷款契约:来自SOX404 条款披露的证据Internal Control Weakness and Bank Loan Contracting: Evidence from SOX Section 404 Disclosures52. 审计师对财务报告内部控制的决策:分析、综合和研究方向Auditors I'nternal Control Over Financial Reporting Decisions: Analysis, Synthesis, and Research Directions 53. 应计质量与财务报告内部控制( Doyle ,The Accounting Review, forthcoming )Accruals Quality and Internal Control over Financial Reporting54. 业绩基础CEO 和CFO 薪酬对内部控制质量的影响The impact of performance-based CEO and CFO compensation on internal control quality55. 内部控制重大缺陷与CFO 薪酬Internal Control Material Weaknesses and CFO Compensation56. 财务报告内部控制缺陷的决定因素Determinants of weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting57. 内部控制与管理指南Internal Control and Management Guidance58. 2002 萨班斯-奥克斯利法案302 条款下内部控制缺陷的市场反应以及这些缺陷的特征Market Reactions to the Disclosure of Internal Control Weaknesses and to the Characteristics of thoseWeaknesses under Section 302 of the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 200259. 自愿报告内部风险管理和控制系统的经济激励Economic Incentives for Voluntary Reporting on Internal Risk Management and Control Systems60. 后萨班斯法案时代审计意见的信息含量The information content of audit opinions in the post-sox era61. 上市公司披露的信息含量与萨班斯-奥克斯利法案( April, 2010 )Information Content of Public Firm Disclosures and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act62. 信息摩擦如何影响公司资产流动性的选择?萨班斯法案404 条款的影响How do Informational Frictions Affect the Firm s Choice of A'sset Liquidity? The Effect of SOX Section 404 63. 已审计的信息披露给资本市场参与者带来利益是什么( December 19, 2013)What are the benefits of audited disclosures to equity market participants64. 诉讼风险与审计定价:公众股权的作用( January 7, 2013)Litigation Risk and Audit Pricing: The Role of Public Equity65. 萨班斯-奥克斯利法案对IPO 和高收益债券发行人的影响The Impact of Sarbanes-Oxley on IPOs and High Yield Debt Issuers66. 来自金融危机的公司治理的经验教训The Corporate Governance Lessons from the Financial Crisis67. 谁对企业欺诈吹口哨Who Blows the Whistle on Corporate Fraud68. 内部控制缺陷与现金持有价值Internal Control Weakness and Value of Cash Holdings69. 民族文化和制度环境对内部控制信息披露的影响The impact of national culture and institutional Environment on internal control disclosures70. 财务报告质量与权益资本成本之间联系的讨论:一些个人的意见( June 6, 2013)Some Personal Observations on the Debate on the Link between Financial Reporting Quality and the Cost of Equity Capital71. 使用盈利预测同时估计企业层面的权益资本成本和长期增长Using Earnings Forecasts to Simultaneously Estimate Firm-Specific Cost of Equity and Long-Term Growth72. 高管薪酬差距与权益资本成本Executive Pay Disparity and the Cost of Equity Capital73. 财务报告质量与公司债券市场(博士论文,Mingzhi Liu, 2011 )Financial Reporting Quality and Corporate Bond MarketsReferencesAboody, D., J. Hughes, and J. Liu. (2005) Earnings quality, insider trading, and cost of capital. Journalof Acco un ti ng Research 43: 651 -673.Akins, B., J. Ng and R. Verdi (2012) Investor competition over information and the pricing of information asymmetry. The Accounting Review 87(1): 35-58.Ali, A., A. Klein and J. Rosenfeld. (1992) Analysts ' use of information abouttrpaenrsmitaonryent andearnings components in forecasting annual EPS. The Accounting Review 67: 183-198.Amihud, Y., and H. Mendelson. (1986) Asset pricing and the bid-ask spread. Journal of Financial Econo mics 17: 223 —49.Artiach, T. and P. Clarkson. (2011) Disclosure, conservatism and the cost of equity capital: A review of the foundation literature. Accounting and Finance 51(1): 2-49.Ashbaugh-Skaiffe, H., D. Collins, W. Kinney, Jr., and R. LaFond (2009) The effect of SOX internal control deficiencies on firm risk and cost of equity. Journal of Accounting Research 47(1): 1-43.Armstrong, C., J. Core, D. Taylor and R. Verrecchia (2011) When does information asymmetry affect the cost of capital? Journal of Accounting Research 49(1): 1-40.Balakrishnan, K., R. Vashishtha and R. Verrecchia (2012) Aggregate competition, information asymmetry and cost of capital: Evidence from equity market liberalization. Working paper, University of Pennsylvania.Barron, O., O. Kim, S. Lim and D. Stevens (1998) Using analysts forecasts to measure properties on analysts ' information environmeTnth.e Accounting Review 73: 421-433.Barry, C., and S. Brown. (1985) Differential information and security market equilibrium. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 20: 407 T22.Barth, M., W. Beaver, and W. Landsman (2001) The relevance of value-relevance literature for financial accounting standard setting: Another view, Journal of A”ccounting and Economics (Sept): 77-104.Barth, M., Y. Konchitchki and W. Landsman (2013) Cost of capital and earnings transparency. Journal of Accounting and Economics , forthcoming.Beyer A., D. Cohen, T. Lys and B. Walther (2010) The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 296-343.Bhattacharya, N., F. Ecker, P. Olsson, and K. Schipper (2012) Direct and mediated association among earnings quality, information asymmetry, and the cost of capital, The Accounting Review 87(2): 449-482. Botosan, C. (1997) Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review 72: 323 -350. Botosan, C., and M. Plumlee. (2002) A re-examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research 40: 21 ZO.Botosan, C., M. Plumlee and Y. Xie (2004) The role of information precision in determining the cost of equity capital. Review of Accounting Studies 9 (2-3): 233-259.Botosan, C., and M. Plumlee. (2005) Assessing alternative proxies for the expected risk premium. The Accounting Review 80: 21-53.Botosan, C., M. Plumlee and H. Wen. (2011) The relation between expected returns, realized returns, and firm risk characteristics. Contemporary Accounting Research 28(4): 1085-1122.Brown, P. and T. Walter (2012) The CAPM: Theoretical validity, empirical intractability and practical applications. Abacus 1-7.Callahan, C., R. Smith and A. Spencer (2012) An examination of the cost of capital implications of FIN 46. The Accounting Review 87(4): 1105-1134.Chava, S., and A. Purnanandam (2010) Is default risk negatively related to stock returns? Review of Financial Studies 23: 2523-2559.Chen, S., B. Miao and T. Shevlin (2013) A new measure of disclosure quality: The level of disaggregation of accounting data in annual reports. Working paper, The University of Texas at Austin. Christensen, P., L. de la Rosa and G. Feltham (2010) Information and the cost of capital: An ex ante perspective. The Accounting Review 85(3): 817-848.Clarkson, P., J. Guedes and R. Thompson (1996) On the diversifiability, observability, and measurement of estimation risk. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 31: 69084.Claus, J., and J. Thomas (2001) Equity premia as low as three percent? Evidence from analysts earnings forecasts for domestic and international stock markets. The Journal of Finance 56(5): 1629-1666.Clinch G., and B. Lombardi (2011) Information and the cost of capital: the Easley- O' Hara(2004) modelwith endogeneous information acquisition. Australian Journal of Management 36(5): 5-14.Coles, J., U. Loewenstein, and J. Suay. (1995) On equilibrium pricing under parameter uncertainty. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 30: 347 -374.Core, J., (2001) A review of the empirical disclosure literature: Discussion. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31: 441-456.Core, J., W. Guay and R. Verdi, (2008) Is accruals quality a priced risk factor? Journal of Accountingand Economics 46: 2-22.Daniel, K. and S. Titman, 1997, Evidence on the characteristics of cross-sectional variation in common stock returns. Journal of Finance 52, 1-33.Daske, H., L Hail, C. Leuz and R. Verdi (2008) Mandatory IFRS reporting around the world: Early evidence on the economic consequences. Journal of Accounting Research 46: 1085-1142.Daske, H., L Hail, C. Leuz and R. Verdi, (2013) Adopting a label: Heterogeneity in the economic consequences around IAS/IFRS adoptions. Journal of Accounting Research 51(3):495-548.Dechow, P. and I. Dichev. (2002) The quality of accruals and earnings: the role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review 77 (Supplement): 35-59.Dechow, P., W. Ge and C. Schrand (2010) Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 344-401.Dhaliwal, D., L. Krull and W. Moser (2005) Dividend taxes and implied cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research 43(5): 675-708.Dhaliwal, D., L. Krull and O. Li (2007) Did the 2003 Tax Act reduce the cost of equity capital? Journal of Accounting and Economics 43(1): 121-150.Diamond, D., and R. Verrecchia. (1991) Disclosure, liquidity, and cost of capital. Journal of Finance 46: 1325 -59. Dye, R., (2001) An evaluation of “ essayson disclosure a”nd the disclosure literature in accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 32: 181-235.Easley, D., S. Hvidkjaer and M. O'Hara.(2002) Is information risk a determinant of asset returns. Journal of Finance 57: 2185-2221.Easley, D., and M. O' Hara. (2004) Information and the cost of capital. Journal of Fi nance 59: 1553-1583. Easton, P. (2004) PE ratios, PEG ratios, and estimating the implied expected rate of return on equity capital. The Accounting Review 79(1): 73-96.Easton, P., and S. Monahan. (2005) An evaluation of accounting based measures of expected returns. The Accounting Review 80: 501 -538.Easton, P., and S. Monahan. (2010) Evaluating accounting-based measures of expected returns: Easton and Monahan and Botosan and Plumlee redux. Working paper, University of Notre Dame.Ecker, F., J. Francis, I. Kim, P. Olsson, and K. Schipper (2006). A returns-based representation of earnings quality. The Accounting Review 81: 749 -780.Fama, E., and J. MacBeth. 1973. Risk, return, and equilibrium: Empirical tests. Journal of Political Economy 81: 607-636.Fama, E., and K. French. (1992) The cross-section of expected stock returns. Journal of Finance 47(2): 427-465. Fama, E., and K. French. (1993) Common risk factors in the returns on bonds and stocks. Journal of Financial Economics 33: 3-56.Francis, J., LaFond, R., Olsson, P., and K. Schipper. (2004) Costs of equity and earnings attributes. The Accounting Review 79: 967-1010.Francis, J., LaFond, R., Olsson, P., and K. Schipper. (2005) The market pricing of accruals quality. Journal of Accounting & Economics 39: 295-327.Francis, J., Nanda, D., and P. Olsson. (2008) Voluntary disclosure, information quality, and costs of capital. Journal of Accounting Research 46 (1): 53-99.Gebhardt,W., C. Lee and B. Swaminathan (2001) Towards an ex ante cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research 39(1): 135-176.Goh, B-W., J. Lee, C-Y. Lim and T. Shevlin (2013) The effect of corporate tax avoidance on the cost of equity. Working paper, Singapore Management University.Gow, I., G. Ormazabal and D. Taylor (2010) Correcting for cross-sectional and time-series dependence in accounting research The Accounting Review 85(2): 483-512.Gray, P., P. Koh and Y. Tong (2009) Accruals quality, information risk and cost of capital: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 36(1-2): 51-72.Guay, W., S.P. Kothari and S. Shu (2011) Properties of implied cost of capital using analysts forecasts. Australian Journal of Management 36(2): 125-149.Hail, L. (2002) The impact of voluntary corporate disclosure on the ex-ante cost of capital for Swiss firms European Accounting Review 11: 741-773.Hail, L., and C. Leuz. (2006) International differences in the cost of equity capital: Do legal institutions and securities regulation matter? Journal of Accounting Research 44(3): 485-531.Healy, P., and K. Palepu (2001) Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31: 405-440. Hirshleifer, D., K. Hou, and S.H. Teoh (2012) The accrual anomaly: Risk or mispricing? ManagementScienee (58-2); 320 -335.Holthausen, R., and R. Watts (2001) The relevance of value-relevance literature for financial accounting standard setting. Journal of Accounting and Economics (Sept): 3-75.Hribar, P. and T, Jenkins. (2004) The effect of accounting restatements on earnings revisions and the estimated cost of capital. Review of Accounting Studies 9(2-3): 337-356.Hughes, J. S., J. Liu, and J. Liu. (2007) Information asymmetry, diversification, and cost of capital. The Accounting Review 82: 705-729.Hughes, J. S., J. Liu, and J. Liu. (2009) On the association between expected returns and implied cost of capital R”eview of Accounting Studies 14: 246-259.Hutchens, M. and S. Rego (2013) Tax risk and the cost of equity capital. Working paper, Indiana University. Hwang, L-S., W-J. Lee, S-Y. Lim and K-H. Park, (2013) Does information risk affect the implied cost of equity capital? An analysis of PIN and adjusted PIN. Journal of Accounting and Economics 55(2-3): 148-167.Kim, D., and Y. Qi (2010) Accruals quality, stock returns, and macroeconomic conditions. The Accounting Review 85(3): 937-978.Klein, R., and V. Bawa. (1977) The effect of estimation risk on optimal portfolio choice. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 215-231.Kothari, S.P., X. Li and J. Short. (2009) The effect of disclosures by management, analysts, and financial press oncost of capital, return volatility, and analyst forecasts: A study using content analysis. The Accounting Review82(5): 1255-1297.Kravet, T. and T. Shevlin. (2010) Accounting restatements and information risk. Review of Accounting Studies 15: 264-294.Kyle, A. (1985) Continuous auctions and insider trade. Econometrica 53(6): 1315-1335.Lambert, R., C. Leuz, and R. Verrecchia. (2007) Accounting information, disclosure, and the cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research 45(2): 385-420.Lambert, R., C. Leuz, and R. Verrecchia. (2012) Information asymmetry, information precision, and the cost of capital. Review of Finance 16: 1-29.Lambert, R., (2009) Discussion of “onthe association between expected returns and implied cost of capital R”eview of Accounting Studies 14: 260-268.Leuz, C., and R. Verrecchia (2004) Firms ' capital allocatio n choices, in formati on qhuaCys tandcapital. Work ing paper, Uni versity of Penn sylva nia.Li, V., T. Shevli n and D. Shores (2013) Revisit ing the AQ measure of accrual quality. Work ing paper, Uni versityof Wash ington.Lys, T., and S. Sohn. (1990) The associati on betwee n revisi ons of finan cial an alyst forecastsearning and security price cha nges. Jour nal of Acco un ti ng and Econo mics 13: 341-363.Mashruwala, C. and S. Mashruwala (2011) The pric ing of accrual quality: January versus the rest of the year. TheAccou nting Review 86(4): 1349-1381.McInnis, J. (2010) Earnings smoothness, average returns and implied cost of equity capital. The Accou ntingReview 85(1): 315-341.Mohanram, P., and D. Gode (2013) Removing predictable analyst forecast errors to improve implied cost of equity estimates. Review of Acco un ti ng Studies 18: 443-478.Ogneva, M., K.R. Subramanyam, and K. Raghunandan (2007) Internal control weakness and cost of equity: Evidenee from SOX Section 404 disclosures. The Accou nti ng Review 82(5) :1255-1297.Ogneva, M., (2012) Accrual quality, realized returns, and expected returns: The importanee of con trolli ng forcash flow shocks, The Accou nting Review 87(4): 1415-1444.Peterse n, M., (2009) Estimati ng sta ndard errors in finance data pan els: Compari ng approaches. Reviewof Financial Studies 22(1): 435-480.Petkova, R. (2006) Do the Fama-Fre nch factors proxy for inno vati on in predictive variables? Journal of Finance61: 581-612.Reidl, E., and G. Serafeim (2011) In formati on risk and fair values: An exam in ati on of equity betas. Journal ofAccounting Research 49(4): 1083-1122.Strobl, G., (2013) Earnings manipulation and the cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, forthco ming. Verrecchia, R. (2001) Essays on disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics 32: 97-180.Vuolteenaho, T. (2002) What drives firm-level stock returns? The Journal of Finance 57: 233 -264.How Do Various Forms of Auditor Rotation Affect Audit Quality? Evidence from China内部控制质量、企业风险与权益资本成本一一理论分析与实证检验1. Accruals Quality and In ternal Con trol over Finan cial Report in g.Acco un ti ng Review, Oct2007, V ol.82 Issue52. Audit Committee Quality and Internal Control An Empirical Analysis.FullAccounting Review, Apr2005, Vol.80 Issue 23. Bala ncing the Dual Resp on sibilities of Busin ess Un it Con trollers Field and Survey Evide nee. Accounting Review, Jul2009, Vol. 84 Issue44. Corporate Governance and Internal Control over Financial Reporting A Comparison ofRegulatory Regimes Accou nting Review, May2009, Vol. 84 Issue 35. Ear nings Man ageme nt of Firms Report ing Material In ternal Con trol Weak nesses un der Sect ion 404of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Auditing, Nov2008, Vol. 27 Issue 26. Economic Incentives for V oluntary Reporting on Internal Risk Management and Control Systems.Auditing, May2008, V ol. 27 Issue 67. Firm Characteristics and Volu ntary Man ageme nt Reports on In ternal Con trol. Audit ing, Nov2006,Vol. 25 Issue28. Former Audit Partners on the Audit Committee and Internal Control Deficiencies. Accounting Review,Mar2009, Vol. 849.Internal Control Quality and Audit Pricing under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act . Auditing, May2008, Vol.2710.Internal Control Weakness and Cost of Equity Evidenee from SOX Section 404 Disclosures Accou nti ngReview, Oct2007, Vol. 8211.I nternal Control Weak nesses and In formatio n Un certai nty. Accou nting Review, May2008, Vol. 8312.lnternal Controls and the Detection of Management Fraud. Journal of Accounting Research, Sprin g99,Vol. 3713.Reduci ng Man ageme nt's In flue nee on Auditors Judgme nts An Experime ntal In vestigati on of SOX404 Assessme nts Acco un ti ng Review, Nov2008, V)l. 8314.SOX Section 404 Material WeaknessDisclosures and Audit Fees.Full Auditing, May2006, Vol. 2515.The Effect of SOX Internal Control Deficiencies and Their Remediation on Accrual Quality. AccountingReview, Jan2008, Vol. 8316.The Impact of SOX Section 404 Internal Control Quality Assessment on Audit Delay in the SOX Era.Auditing, Nov2006, Vol. 25Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D. W., & Kinney Jr., W. R. (2007). The discovery and reporting of internal con trol deficie ncies prior to SOX-ma ndated audits. Jour nal of Acco unting and Economics, 44(1 —2), 166 -92.Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D. W., Kinney Jr, W. R., & Lafond, R. (2009). The Effect of SOX Internal Control Deficiencies on Firm Risk and Cost of Equity. Journal of Accounting Research, 47(1),1 -43.Bahramian, A. (2011), Evaluation of the effectiveness of internal controls in an Investment Company, Master Thesis in Imam Hossein University, Iran.Daraby, M, (2006), analyzing the effect of strengthening internal controls, audit reports of companies listed on the Stock Audit, Master Thesis in Azan Islamic university.Doyle, J., Ge, W., & McVay, S. (2007). Determinants of weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44(1 -2), 193 -223.Feng, M., Li, C., & McVay, S. (2009). Internal control and management guidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 48(2 -3), 190 -209.Maham K., Poriya Nasab, A. (2000), Internal control) Integrated Framework( , Report of the Committee of the Commission Tardy, azman Hesabresy, Pages 118, 135.Ogneva, M., Subramanyam, K. R., & Raghunandan, K. (2007). Internal control weakness and cost of equity: evidence from SOX Section 404 disclosures. The Accounting Review, 82(5), 1255-1297.Rezaie Jahangoshaee, H, (1996). A analytical study of the degree of reliance of independent auditors on firms internal controls, Master Thesis, shahid Beheshti University, Iran.。

61ARKET ANALYSIS市场分析摘 要:布伦特原油和迪拜原油是原油实货交易的两个重要计价基础,场外的布迪价差合约能够将Brent和Dubai两个计价体系联系起来。

考虑到西非和中东原油的特性和计价特点,通过研究布迪价差与西非和中东原油跨区套利交易之间的关系,发现西非和中东原油现货价差与布迪价差存在相互影响的关系,且这种影响有几天的滞后性。

同时,利用自回归分布滞后模型,较好地将布迪价差与西非和中东原油现货价差进行了拟合,模拟出跨区套利交易对布迪价差影响的可能路径。

关键词:原油,Brent原油,Dubai原油,布迪价差,跨区套利Abstract :Brent and Dubai are two important benchmark assessment of the value of physical. Brent 1st line vs. Dubai 1st line future, an OTC contact called B/D swap, can transfer the pricing of physical from Brent to Dubai. Considering the grades characteristics and benchmark features of crude oil from the West Africa and the Middle East, this paper finds the mutual influence between the West Africa and the Middle East grades spot price differential and B/D swap and its lag effects by studying the relationship between B/D swap and cross-regional arbitrage trading. Meanwhile, it uses autoregressive distributed lag model (which can be abbreviated to ADL) to fit B/D swap and the spot price differential between the West Africa and the Middle East grades, and results in the possible path by which the cross-regional arbitrage trading affects B/D swap.Key words :crude oil; Brent benchmark; Dubai benchmark; B/D swap; cross-regional arbitrage布迪价差与原油跨区套利关系研究雷健( 中化国际石油(伦敦)有限公司)Study on the relationship between B/D swap and cross-regional arbitrageJay Lei(Sinochem International Oil (London) Co., Ltd.)62INTERNATIONAL PETROLEUM ECONOMICS国际石油经济Vol.29, No.32021图1 Brent和Dubai的关系拓展1 研究背景1.1 原油计价体系概述原油实物交易价格通常是以一个基准价格加上升贴水确定。

烤肉制品的油脂提取方法的研究及其过氧化值的测定刘文平1,谭操1,李平1,刘忠义1,*,唐道邦2,*(1.湘潭大学食品与生物工程系,湖南湘潭411105;2.广东省农业科学院蚕业与农产品加工研究所,广东广州510610)摘要:以烤肉制品为原料,采用正己烷-异丙醇溶剂浸提法提取油脂,旨在提高低脂肪烤肉制品中油脂提取率同时准确测定其过氧化值。

油脂提取的最优条件:称取肉样(绞碎混匀)2.000g ,加入正己烷-异丙醇(4ʒ1,v /v )混合溶剂20mL ,浸泡过夜,2500r /min 离心20min ;旋转蒸发至尽干,于真空干燥箱中干燥1.5h 。

用该方法对不同烤肉制品进行验证性实验,均获得了较好的提取效果。

该提取方法回收率为84.51% 113.20%,提取率的相对标准偏差为0.12%0.67%,表明该油脂提取方法准确度和精密度均较高。

测定所提油脂的过氧化值,结果表明该油脂提取方法不会影响其过氧化值测定结果,并解决了石油醚浸提法无法准确测定低脂肪肉制品(鸡肉)中过氧化值的问题。

关键词:烤肉制品,油脂,提取剂,提取率Extraction method of the oils and fats and theperoxide value determination in barbecue productsLIU Wen -ping 1,TAN Cao 1,LI Ping 1,LIU Zhong -yi 1,*,TANG Dao -bang 2,*(1.College of Food and Biological Engineering ,Xiangtan University ,Xiangtan 411105,China ;2.Sericulture&Agri-food Research Institute ,Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences ,Guangzhou 510610,China )Abstract :Oil was extracted from barbecue products by n -hexane -isopropanol (4ʒ1,v /v )solvent extraction method ,in order to improve the oil extraction rate in low -fat barbecue products and the degree of accuracy of peroxide value determination results in barbecue products .The results showed that the optimal conditions of oil extraction in barbecue products were determined to be the minced meat samples 2.000g were soaked in 20mL n -hexane -isopropanol (4ʒ1,v /v )for the night ,and then centrifuged for 20min at the speed of 2500r /min ,and the solvent of the oil extraction was removed with a rotary evaporator ,and then dried for 1.5h in a vacuum oven .When it was used to extract the oil from the different barbecue products as validation experiments ,a good extraction result was gained .The recovery of this method was in the range of 84.51%to 113.20%,and the relative standard deviation of extraction rate was in the range of 0.12%to 0.67%.This method has high accuracy and precision .It did not affect the peroxide value determination ,and it can accurately measure the peroxide value in low -fat meat products ,such as chicken .Key words :barbecue products ;oils and fats ;the extraction agent ;the extraction rate 中图分类号:TS251.7文献标识码:A文章编号:1002-0306(2014)13-0076-05doi :10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2014.13.007收稿日期:2013-10-08*通讯联系人作者简介:刘文平(1987-),女,硕士研究生,研究方向:食品、生物与制药工程。

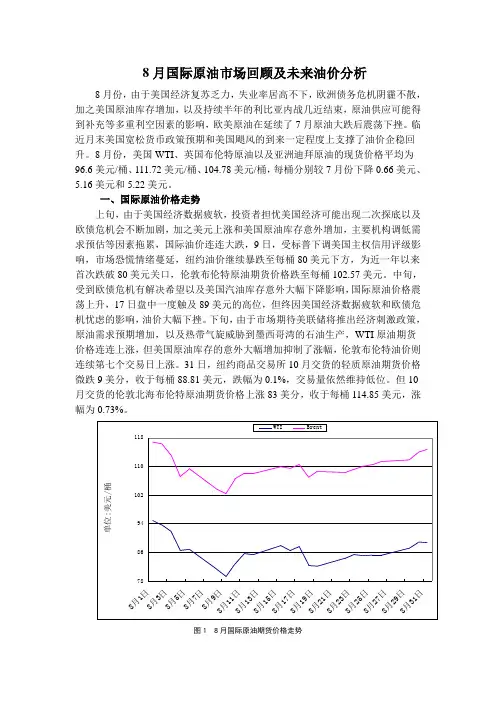

8月国际原油市场回顾及未来油价分析8月份,由于美国经济复苏乏力,失业率居高不下,欧洲债务危机阴霾不散,加之美国原油库存增加,以及持续半年的利比亚内战几近结束,原油供应可能得到补充等多重利空因素的影响,欧美原油在延续了7月原油大跌后震荡下挫。

临近月末美国宽松货币政策预期和美国飓风的到来一定程度上支撑了油价企稳回升。

8月份,美国WTI、英国布伦特原油以及亚洲迪拜原油的现货价格平均为96.6美元/桶、111.72美元/桶、104.78美元/桶,每桶分别较7月份下降0.66美元、5.16美元和5.22美元。

一、国际原油价格走势上旬,由于美国经济数据疲软,投资者担忧美国经济可能出现二次探底以及欧债危机会不断加剧,加之美元上涨和美国原油库存意外增加,主要机构调低需求预估等因素拖累,国际油价连连大跌,9日,受标普下调美国主权信用评级影响,市场恐慌情绪蔓延,纽约油价继续暴跌至每桶80美元下方,为近一年以来首次跌破80美元关口,伦敦布伦特原油期货价格跌至每桶102.57美元。

中旬,受到欧债危机有解决希望以及美国汽油库存意外大幅下降影响,国际原油价格震荡上升,17日盘中一度触及89美元的高位,但终因美国经济数据疲软和欧债危机忧虑的影响,油价大幅下挫。

下旬,由于市场期待美联储将推出经济刺激政策,原油需求预期增加,以及热带气旋威胁到墨西哥湾的石油生产,WTI原油期货价格连连上涨,但美国原油库存的意外大幅增加抑制了涨幅,伦敦布伦特油价则连续第七个交易日上涨。

31日,纽约商品交易所10月交货的轻质原油期货价格微跌9美分,收于每桶88.81美元,跌幅为0.1%,交易量依然维持低位。

但10月交货的伦敦北海布伦特原油期货价格上涨83美分,收于每桶114.85美元,涨幅为0.73%。

图1 8月国际原油期货价格走势二、8月份石油市场特点及影响因素1、WTI较布伦特溢价水平进一步扩宽。

随着美国经济持续显现疲态,复苏乏力,美国原油较布伦特油价格溢价进一步扩大。

72INTERNATIONAL PETROLEUM ECONOMICS国际石油经济Vol.28, No.122020摘 要:新冠肺炎疫情在全球范围内暴发,持续冲击世界经济,2020年4月20日,美国原油期货价格史无前例地跌至-40.32美元/桶,疫情期间国际原油价格驱动因素值得探讨。

选取2020年1月13日至8月3日交易日数据,考虑结构突变,构建国际原油价格驱动因素断点最小二乘法模型。

经实证,原油价格跌至负值当日确为模型的结构断点,结构断点前新冠肺炎疫情对国际原油价格上涨起严重阻碍作用,投资者预期对国际原油价格上涨也存在消极影响;结构断点后货币政策消极程度严重阻碍国际原油价格上涨;原油需求对原油期货价格的影响在结构断点前后有所不同。

据此认为,疫情防控和提升货币的政策积极性是各国的首要任务,保持对投资者具有重大利好的货币政策倾向、提升信息透明度是促进原油价格提升的重要手段。

关键词:新冠肺炎疫情;国际原油价格;断点最小二乘法;邹突变点检验Abstract :The outbreak of COVID-19 on a global scale continues to impact the world economy. On April 20, 2020, the US crude oil futures price fell to USD -40.32/barrel for an unprecedented time due to the impact of the pandemic. It is worth exploring the driving factors of international crude oil price during the pandemic. The paper selects the trading date of solstice on January 13, 2020 to August 3, considers the abrupt change of structure, and constructs driving factors of international crude oil price—the least square model of the breakpoint. Empirical results show that the day when crude oil price falls to the negative is indeed the structural break point of the model. Before the structural break point, COVID-19 has seriously hindered the rise of international crude oil price, and investor’s expectations also have a negative impact on the rise of international crude oil price. After the structural break point, the degree of monetary policy passivity seriously hinders the rise of international crude oil price. The effect of crude oil demand on crude oil futures price varies before and after the structural break point. Therefore, this paper believes that the prevention and control of the pandemic and the promotion of monetary policy initiatives are the top priorities of all countries in the world, and maintaining a monetary policy orientation that is highly beneficial to investors and improving information transparency are also important means to promote the increase of international crude oil prices.Key words :the COVID-19; international crude oil price; least square with breakpoint; Chow breakpoint test新冠肺炎疫情下国际原油价格驱动因素研究——基于断点最小二乘法与邹突变点检验闫勇1,张雪峰2,宋鸽2,付杨3( 1.中国石油集团经济技术研究院;2.北方工业大学经济管理学院;3.北京石油机械有限公司)Research on the driving factors of international crude oil price under COVID-19—Based on least square with breakpoint and Chow breakpoint test YAN Yong 1, ZHANG Xuefeng 2, SONG Ge 2, FU Yang 3(1. CNPC Economics &Technology Research Institute; 2. School of Economics and Management, North China University of Technology; 3. CNPC Beijing Oilfield Machinery Co., Ltd.)FORUM油价论坛731 国际原油价格驱动因素及相关研究2020年初,新型冠状病毒肺炎(下文简称“新冠”)疫情在全球范围内暴发。

基于ARIMA模型的石油价格短期分析预测基于 ARIMA 模型的石油价格短期分析预测摘要2008年国际石油市场经历了前所未有的大起大落,受多种因素影响,国际市场油价在上半年节节攀升,并在7月11日创下每桶145.66美元的历史昀高纪录;在下半年又迅速跌落,并在 12 月 5 日跌至每桶 37.94 美元,创 4 年来昀低水平。

在短短五个月内下跌了100美元以上,其走势“变幻莫测”。

国际油价从加速膨胀到泡沫破裂,对大到世界经济、政治格局,小到企业、个人的决策都产生了深远的影响。

本文正是基于石油的重要性,选择石油价格展开研究,作出一个计量经济学方面的探讨。

本文首先介绍了ARIMA模型的理论与方法,并以布伦特原油的现货报价为依据,建立 ARIMA 预测模型,昀后分析了 2009年国际以及石油行业的新的局势和动态,将定量分析和定性分析相结合,对石油价格的未来走势进行分析和判断。

这对于国家制定石油贸易策略、参与石油期货交易、企业科学决策都有着一定的意义和作用。

关键词:石油价格;ARIMA模型;预测;时间序列模型I 基于 ARIMA 模型的石油价格短期分析预测AbstractIn 2008, the international petroleum marketplace has experienced big up and down, becauseof many factors, the international petroleum price climbed very quickly in the first half of the2008, and created imal notes of history by 145.66 U. S. dollar per barrel on July 11. Butdropped also quickly and fall to 37.94 U. S. dollar per barrel on December 5, creating lowestlevel in 4 years. In just five months dropped by more than 100 U.S. dollars, the trend wasunpredictable. Accelerate the expansion of international oil prices from the bubble burst. Largeto the world economy, political structure, small to enterprises and individuals in decision-makinghave had a far-reaching impact on. This article is based on the importance of oil, choose to studyin oil prices, make a measurement of economics. The article firstanalyzes the impact of variousfactors in oil prices, and bases on the spot pricing of Brent crude oil, establishes forecastingmodel “ARIMA”. Finally analyze the interna tional oil industry, as well as a new and dynamicsituation, integrate the quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis, on the future direction of oilprices to analyze and judge. There is a big significance for the national strategy for thedevelopment of oil trade, to participate in oil futures, a scientific decision-making for enterpriseThe key words: Oil prices; ARIMA model; Forecast; Time Series Model II 基于 ARIMA 模型的石油价格短期分析预测目录摘要 IAbstract. II目录. III1 绪论 11.1论文的研究背景11.2 论文的研究目的与意义. 21.3 研究现状. 31.4 研究的思路和内容42 时间序列的理论模型与方法概述. 52.1 时间序列模型的含义 52.2 随机时间序列模型52.3 平稳时间序列 52.4 时间序列模型的建模步骤92.5 预测评价中的其他指标 183 石油价格形成及影响因素分析203.1 石油价格构成因素. 203.2 石油价格短期影响因素分析214 ARIMA模型在石油价格中的定量分析 25 4.1 数据来源 254.2 时间序列的平稳性检验 25III 基于 ARIMA 模型的石油价格短期分析预测4.3 检查二阶差分的平稳性 274.4 模型的识别与定阶. 304.5 模型的检验. 354.6 模型的预测. 365 石油价格短期走势的定性分析385.1 世界经济表现385.2 供需形势变化385.3 欧佩克减产政策 405.4 美元走势分析415.5 地缘政治局势425.6 市场投机炒作425.7 小结. 42结论44参考文献. 45附录47致谢49IV 基于 ARIMA 模型的石油价格短期分析预测1 绪论1.1 论文的研究背景[1]2008年的国际石油价格波动剧烈程度超出人们的预料。

An Anatomy of the Crude Oil PricingSystemBassam Fattouh1WPM 40January 20111 Bassam Fattouh is the Director of the Oil and Middle East Programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies; Research Fellow at St Antony‟s College, Oxford University; and Professor of Finance and Management at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. I would like to express my gratitude to Argus for supplying me with much of the data that underlie this research. I would also like to thank Platts for providing me with the data for Figure 21 and CME Group for providing me with the data for Figure 13. The paper has benefited greatly from the helpful comments of Robert Mabro and Christopher Allsopp and many commentators who preferred to remain anonymous but whose comments provided a major source of information for this study. The paper also benefited from the comments received in seminars at the Department of Energy and Climate Change, UK, ENI, Milan and Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Oxford. Finally, I would like to thank those individuals who have given their time for face-to-face and/or phone interviews and have been willing to share their views and expertise. Any remaining errors are my own.The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of itsmembers.Copyright © 2011Oxford Institute for Energy Studies(Registered Charity, No. 286084)This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.ISBN978-1-907555-20-6ContentsSummary Report (6)1. Introduction (11)2. Historical Background to the International Oil Pricing System (14)The Era of the Posted Price (14)The Pricing System Shaken but Not Broken (14)The Emergence of the OPEC Administered Pricing System (15)The Consolidation of the OPEC Administered Pricing System (16)The Genesis of the Crude Oil Market (17)The Collapse of the OPEC Administered Pricing System (18)3. The Market-Related Oil Pricing System and Formulae Pricing (20)Spot Markets, Long-Term Contracts and Formula Pricing (20)Benchmarks in Formulae Pricing (24)4. Oil Price Reporting Agencies and the Price Discovery Process (30)5. The Brent Market and Its Layers (36)The Physical Base of North Sea (37)The Layers and Financial Instruments of the Brent Market (39)Data Issues (39)The Forward Brent (40)The Brent Futures Market (43)The Exchange for Physicals (44)The Dated Brent/BFOE (45)The Contract for Differences (CFDs) (45)OTC Derivatives (48)The Process of Oil Price Identification in the Brent Market (50)6. The US Benchmarks (52)The Physical Base for US Benchmarks (52)The Layers and Financial Instruments of WTI (55)The Price Discovery Process in the US Market (56)WTI: The Broken Benchmark? (58)7. The Dubai-Oman Market (61)The Physical Base of Dubai and Oman (61)The Financial Layers of Dubai (62)The Price Discovery Process in the Dubai Market (64)Oman and its Financial Layers: A New Benchmark in the Making? (66)8. Assessment and Evaluation (70)Physical Liquidity of Benchmarks (70)Shifts in Global Oil Demand Dynamics and Benchmarks (71)The Nature of Players and the Oil Price Formation Process (73)The Linkages between Physical Benchmarks and Financial Layers (74)Adjustments in Price Differentials versus Price Levels (74)Transparency and Accuracy of Information (76)9. Conclusions (78)References (81)List of FiguresFigure 1: Price Differentials of Various Types of Saudi Arabia‟s Crude Oil to Asia in $/Barrel (21)Figure 2: Differentials of Term Prices between Saudi Arabia Light and Iran Light Destined to Asia (FOB) (In US cents) (23)Figure 3: Difference in Term Prices for Various Crude Oil Grades to the US Gulf (Delivered) and Asia (FOB) (24)Figure 4: Price Differential between Dated Brent and BWAVE ($/Barrel) (26)Figure 5: Price Differential between WTI and ASCI ($/Barrel) (ASCI Price=0) (26)Figure 6: Brent Production by Company (cargoes per year), 2007 (37)Figure 7: Falling output of BFO (38)Figure 8: Trading Volume and Number of Participants in the 21-Day BFOE Market (42)Figure 9: Average Daily Volume and Open Interest of ICE Brent Futures Contract (44)Figure 10: Pricing basis of Dated Brent Deals (1986-1991); Percentage of Total Deals (45)Figure 11: Reported Trade on North Sea CFDs (b/d) (46)Figure 12: US PADDS (52)Figure 13: Monthly averages of volumes traded of the Light Sweet Crude Oil Futures Contract (55)Figure 14:Liquidity at Different Segments of the Futures Curve (October 19, 2010) (56)Figure 15: Spot Market Traded Volumes (b/d) (April 2009 Trade Month) (57)Figure 16: Spread between WTI 12-weeks Ahead and prompt WTI ($/Barrel) (59)Figure 17: WTI-BRENT Price Differential ($/Barrel) (60)Figure 18: Dubai and Oman Crude Production Estimates (thousand barrels per day) (62)Figure 19: Spread Deals as a Percentage of Total Number of Dubai Deals (63)Figure 20: Oman-Dubai Spread ($/Barrel) (64)Figure 21: Dubai Partials Jan 2008 - Nov 2010 (65)Figure 22: daily Volume of Traded DME Oman Crude Oil Futures Contract (67)Figure 23: Volume and Open Interest of the October 2010 Futures Contracts (Traded During Month of August) (68)Figure 24: OECD and Non-OECD Oil Demand Dynamics (71)Figure 25: Change in Oil Trade Flow Dynamics (72)Figure 26: The North Sea Dated differential to Ice Brent during the French Strike (76)Summary ReportThe view that crude oil has acquired the characteristics of financial assets such as stocks or bonds has gained wide acceptance among many observers. However, the nature of …financialisation‟ and its implications are not yet clear. Discussions and analyses of …financialisation‟ of oil markets have partly been subsumed within analyses of the relation between finance and commodity indices which include crude oil. The elements that have attracted most attention have been outcomes: correlations between levels, returns, and volatility of commodity and financial indices. However, a full understanding of the degree of interaction between oil and finance requires, in addition, an analysis of interactions, causations and processes such as the investment and trading strategies of distinct types of financial participants; the financing mechanisms and the degree of leverage supporting those strategies; the structure of oil derivatives markets; and most importantly the mechanisms that link the financial and physical layers of the oil market.Unlike a pure financial asset, the crude oil market also has a …phy sical‟ dimension that should anchor prices in oil market fundamentals: crude oil is consumed, stored and widely traded with millions of barrels being bought and sold every day at prices agreed by transacting parties. Thus, in principle, prices in the futures market through the process of arbitrage should eventually converge to the so-called …spot‟ prices in the physical markets. The argument then goes that since physical trades are transacted at spot prices, these prices should reflect existing supply-demand conditions.In the oil market, however, the story is more complex. T he …current‟ market fundamentals are never known with certainty. The flow of data about oil market fundamentals is not instantaneous and is often subject to major revisions which make the most recent available data highly unreliable. Furthermore, though many oil prices are observed on screens and reported through a variety of channels, it is important to explain what these different prices refer to. Thus, although the futures price often converges to a …spot‟ price, one should aim to analyse the process of convergence and understand what the …spot‟ price in the context of the oil market really means.Unfortunately, little attention has been devoted to such issues and the processes of price discovery in oil markets and the drivers of oil prices in the short-run remain under-researched. While this topic is linked to the current debate on the role of speculation versus fundamentals in the determination of the oil price, it goes beyond the existing debates which have recently dominated policy agendas. This report offers a fresh and deeper perspective on the current debate by identifying the various layers relevant to the price formation process and by examining and analysing the links between the financial and physical layers in the oil market, which lie at the heart of the current international oil pricing system.The adoption of the market-related pricing system by many oil exporters in 1986-1988 opened a new chapter in the history of oil price formation. It represented a shift from a system in which prices were first administered by the large multinational oil companies in the 1950s and 1960s and then by OPEC for the period 1973-1988 to a system in which prices are set by …markets‟. First adopted by the Mexican national oil company PEMEX in 1986, the market-related pricing system received wide acceptance among most oil-exporting countries. By 1988, it became and still is the main method for pricing crude oil in international trade after a short experimentation with a products-related pricing system in the shape of the netback pricing regime in the period 1986-1987. The oil market was ready for such a transition. The end of the concession system and the waves of nationalisation which disrupted oil supplies to multinational oil compan ies established the basis of arm‟s-length deals and exchange outside the vertically and horizontally integrated multinational companies. The emergence of many suppliers outside OPEC and many buyers further increased the prevalence of such arm‟s-length deals. This led to the development of a complex structure of interlinked oil markets which consist of spot and also physical forwards, futures, options and other derivative markets referred to as paper markets. Technological innovations which made electronic trading possible revolutionised these markets by allowing 24-hour trading from any place in theworld. It also opened access to a wider set of market participants and allowed the development of a large number of trading instruments both on regulated exchanges and over the counter.Physical delivery of crude oil is organised either through the spot (cash) market or through long-term contracts. The spot market is used by transacting parties to buy and sell crude oil not covered by long term contractual arrangements and applies often to one-off transactions. Given the logistics of transporting oil, spot cargoes for immediate delivery are rare. Instead, there is an important element of forwardness in spot transactions. The parties can either agree on the price at the time of agreement, in which case the sport transaction becomes closer to a …forward‟ contract. More often though, transacting parties link the pricing of an oil cargo to the time of loading.Long-term contracts are negotiated bilaterally between buyers and sellers for the delivery of a series of oil shipments over a specified period of time, usually one or two years. They specify among other things, the volumes of crude oil to be delivered, the delivery schedule, the actions to be taken in case of default, and above all the method that should be used in calculating the price of an oil shipment. Price agreements are usually concluded on the method of formula pricing which links the price of a cargo in long-term contracts to a market (spot) price. Formula pricing has become the basis of the oil pricing system. Formula pricing has two main advantages. Crude oil is not a homogenous commodity. There are various types of internationally traded crude oil with different qualities and characteristics which have a bearing on refining yields. Thus, different crudes fetch different prices. Given the large variety of crude oils, the price of a particular type is usually set at a discount or at a premium to marker or reference prices, often referred to as benchmarks. The differentials are adjusted periodically to reflect differences in the quality of crudes as well as the relative demand and supply of the various types of crudes. Another advantage of formula pricing is that it increases pricing flexibility. When there is a lag between the date at which a cargo is bought and the date of arrival at its destination, there is a price risk. Transacting parties usually share this risk through the pricing formula. Agreements are often made for the date of pricing to occur around the delivery date.At the heart of formulae pricing is the identification of the price of key …physical‟ benchmarks, such as West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Dated Brent and Dubai-Oman. The benchmark crudes are a central feature of the oil pricing system and are used by oil companies and traders to price cargoes under long-term contracts or in spot market transactions; by futures exchanges for the settlement of their financial contracts; by banks and companies for the settlement of derivative instruments such as swap contracts; and by governments for taxation purposes.Few features of these physical benchmarks stand out. Markets with relatively low volumes of production such as WTI, Brent, and Dubai set the price for markets with higher volumes of production elsewhere in the world. Despite the high level of volumes of production in the Gulf, these markets remain illiquid: there is limited spot trading in these markets, no forwards or swaps (apart from Dubai), and no liquid futures market since crude export contracts include destination and resale restrictions which limit trading options. While the volume of production is not a sufficient condition for the emergence of a benchmark, it is a necessary conditio n for a benchmark‟s success. As markets become thinner and thinner, the price discovery process becomes more difficult. Oil price reporting agencies cannot observe enough genuine arms-length deals. Furthermore, in thin markets, the danger of squeezes and distortions increases and as a result prices could then become less informative and more volatile thereby distorting consumption and production decisions. So far the low and continuous decline in the physical base of existing benchmarks has been counteracted by including additional crude streams in an assessed benchmark. This had the effect of reducing the chance of squeezes as these alternative crudes could be used for delivery against the contract. Although such short-term solutions have been successful in alleviating the problem of squeezes, observers should not be distracted from some key questions: What are the conditions necessary for the emergence of successful benchmarks in the most physically liquid market? Would a shift to assessingprice in these markets improve the price discovery process? Such key questions remain heavily under-researched in the energy literature and do not feature in the consumer-producer dialogue.The emergence of the non-OECD as the main source of growth in global oil demand will only increase the importance of such questions. One of the most important shifts in oil market dynamics in recent years has been the shift in oil trade flows to Asia: this may have long-term implications on pricing benchmarks. Questions are already being raised whether Dubai still constitutes an appropriate benchmark for pricing crude oil exports to Asia given its thin physical base or whether new benchmarks are needed to reflect more accurately the recent shift in trade flows and the rise in prominence of the Asian consumer.Unlike the futures market where prices are observable in real time, the reported prices of physical benchmarks are …identified‟ or …assessed‟ prices. Assessments are needed in opaque markets such as crude oil where physical transactions concluded between parties cannot be directly observed by outsiders. Assessments are also needed in illiquid markets where there are not enough representative deals or where no transactions are concluded. These assessments are carried out by oil pricing reporting agencies (PRAs), the two most important of which are Platts and Argus. While PRAs have been an integral part of the oil pricing system, especially since the shift to the market-related pricing system in 1986, their role has recently been attracting considerable attention. In the G20 summit in Korea in November 2010, the G20 leaders called for a more detailed analysis on …how the oil spot market prices are assessed by oil price reporting agencies and how this affects the transparency and functioning of oil markets‟. In its latest report in No vember 2010, IOSCO points that …the core concern with respect to price reporting agencies is the extent to which the reported data accurately refle cts the cash market in question‟. PRAs do not only act as …a mirror to the trade‟. In their attempt to identify the price that reflects accurately the market value of an oil barrel, PRAs enter into the decision-making territory which can influence market structure. What they choose to do is influenced by market participants and market structure while they in turn influence the trading strategies of the various participants. New markets and contracts may emerge to hedge the risks arising from some PRAs‟ decisions. To evaluate the role of PRAs in the oil market, it is important to look at three inter-related dimensions: the methodology used in indentifying the oil price; the accuracy of price assessments; and the internal measures that PRAs implement to protect the integrity and ensure an efficient assessment process. There is a fundamental difference in the methodology and in the philosophy underlying the price assessment process between the various PRAs. As a result, different agencies may produce different prices for the same benchmark. This raises the issue of which method produces a more accurate price assessment. Given that assessed prices underlie long-term contracts, spot transactions and derivatives instruments, even small differences in price assessments between PRAs have important impl ications on exporters‟ revenues and financial flows between parties in financial contracts. In the last two decades or so, many financial layers (paper markets) have emerged around crude oil benchmarks. They include the forward market (in Brent and Dubai), swaps, futures, and options. Some of the instruments such as futures and options are traded on regulated exchanges such as ICE and CME Group, while other instruments, such as swaps, options and forward contracts, are traded bilaterally over the counter (OTC). Nevertheless, these financial layers are highly interlinked through the process of arbitrage and the development of instruments that links the various layers together. Over the years, these markets have grown in terms of size, liquidity, sophistication and have attracted a diverse set of players both physical and financial. These markets have become central for market participants wishing to hedge their risk and to bet on oil price movements. Equally important, these financial layers have become central to the oil price identification process.At the early stages of the current pricing system, linking prices to benchmarks in formulae pricing provided producers and consumers with a sense of comfort that the price is grounded in the physical dimension of the market. This implicitly assumes that the process of identifying the price of benchmarks can be isolated from financial layers. However, this is far from reality. The analysis in this report shows that the different layers of the oil market form a complex web of links, all of which play a role in the price discovery process. The information derived from financial layers is essential for identifying the pricelevel of the benchmark. In the Brent market, the oil price in the forward market is sometimes priced as a differential to the price of the Brent futures contract using the Exchange for Physicals (EFP) market. The price of Dated Brent or North Sea Dated in turn is priced as a differential to the forward market through the market of Contract for Differences (CFDs), another swaps market. Given the limited number of physical transactions and hence the limited amount of deals that can be observed by oil reporting agencies, the value of Dubai, the main benchmark used for pricing crude oil exports to East Asia, is often assessed by using the value of differentials in the very liquid OTC Dubai/Brent swaps market. Thus, one could argue that without these financial layers it would not be possible to …discover‟ or …identify‟ oil prices in the current oil pricing system. In effect, crude oil prices are jointly or co-determined in both layers, depending on differences in timing, location and quality of crude oil.Since physical benchmarks constitute the pricing basis of the large majority of physical transactions, some observers claim that derivatives instruments such as futures, forwards, options and swaps derive their value from the price of these physical benchmarks, i.e., the prices of these physical benchmarks drive the prices in paper markets. However, this is a gross over-simplification and does not accurately reflect the process of crude oil price formation. The issue of whether the paper market drives the physical or the other way around is difficult to construct theoretically and test empirically and requires further research.The report also calls for broadening the empirical research to include the trading strategies of physical players. In recent years, the futures markets have attracted a wide range of financial players including swap dealers, pension funds, hedge funds, index investors, technical traders, and high net worth individuals. There are concerns that these financial players and their trading strategies could move the oil price away from the …true‟ underlying funda mentals. The fact remains however that the participants in many of the OTC markets such as forward markets and CFDs which are central to the price discovery process are mainly …physical‟ and include entities suc h as refineries, oil companies, downstream consumers, physical traders, and market makers. Financial players such as pension funds and index investors have limited presence in many of these markets. Thus, any analysis limited to non-commercial participants in the futures market and their role in the oil price formation process is incomplete and also potentially misleading.The report also makes the distinction between trade in price differentials and trade in price levels. It shows that trades in the levels of the oil price rarely take place in the layers surrounding the physical benchmarks. We postulate that the price level of the main crude oil benchmarks is set in the futures markets; the financial layers such as swaps and forwards set the price differentials depending on quality, location and timing. These differentials are then used by oil reporting agencies to identify the price level of a physical benchmark. If the price in the futures market becomes detached from the underlying benchmark, the differentials adjust to correct for this divergence through a web of highly interlinked and efficient markets. Thus, our analysis reveals that the level of the crude oil price, which consumers, producers and their governments are most concerned with, is not the most relevant feature in the current pricing system. Instead, the identification of price differentials and the adjustments in these differentials in the various layers underlie the basis of the current crude oil pricing system. By trading differentials, market participants limit their exposure to the risks of time, location grade and volume. Unfortunately, this fact has received little attention and the issue of whether price differentials between different markets showed strong signs of adjustment in the 2008-2009 price cycle has not yet received due attention in the empirical literature.But this leaves us with a fundamental question: what determines the price level of a certain benchmark in the first place? The pricing system reflects how the oil market functions: if price levels are set in the futures market and if market participants in these markets attach more weight to future fundamentals rather than current fundamentals and/or if market participants expect limited feedbacks from both thesupply and demand side in response to oil price changes, these expectations will be reflected in the different layers and will ultimately be reflected in the assessed spot price of a certain benchmark.The current oil pricing system has survived for almost a quarter of a century, longer than the OPEC administered system. While some of the details have changed, such as Saudi Arabia‟s decision to replace Dated Brent with Brent futures in pricing its exports to Europe and the more recent move to replace WTI with Argus Sour Crude Index (ASCI) in pricing its exports to the US, these changes are rather cosmetic. The fundamentals of the current pricing system have remained the same since the mid 1980s: the price of oil is set by the …market‟ with PRAs making use of various methodologies to reflect the market price in their assessments and making use of information in the financial layers surrounding the global benchmarks. In the light of the 2008-2009 price swings, the oil pricing system has received some criticism reflecting the unease that some observers feel with the current system. Although alternative pricing systems could be devised such as bringing back the administered pricing system or calling for producers to assume a greater responsibility in the method of price formation by removing destination restrictions on their exports, or allowing their crudes to be auctioned, the reality remains that the main market players such as oil companies, refineries, oil exporting countries, physical traders and financial players have no interest in rocking the boat. Market players and governments get very concerned about oil price behaviour and its global and local impacts, but so far have showed much less interest in the pricing system and market structure that signalled such price behaviour in the first place.1.IntroductionThe adoption of the market-related pricing system by many oil exporters in 1986-1988 opened a new chapter in the history of oil price formation. It represented a shift from a system in which prices were first administered by the large multinational oil companies in the 1950s and 1960s and then by OPEC for the period 1973-1988 to a system in which prices are se t by …markets‟. But what is really meant by the …market price‟ or the …spot price‟ of crude oil?The concept of the …market price‟ of oil associated with the current pricing regime has often been surrounded with confusion. Crude oil is not a homogenous commodity. There are various types of internationally traded crude oil with different qualities and characteristics which have a bearing on refining yields. Thus, different crudes fetch different prices. In the current system, the prices of these crudes are usually set at a discount or a premium to a benchmark or reference price according to their quality and their relative supply and demand. However, this raises a series of questions. How are these price differentials set? More importantly, how is the price of the benchmark or reference crude determined?A simple answer to the latter question would be …the market‟ and the forces of supply and demand for these benchmark crudes. But this raises additional questions. What are the main features of the spot physical markets for these benchmarks? Do these markets have enough liquidity to ensure an efficient price discovery process? What are the roles of the various financial layers such as the futures markets and other derivatives-based instruments that have emerged around the physical benchmarks? Do these financial layers enhance or hamper the price discovery function? Does the distinction between the different layers of the market matter or have the different layers become so inter-linked that the distinction is no longer meaningful? And if the distinction does matter, what do prices in different markets reflect? It is clear from all these questions tha t the concept of …market price‟ needs to be defined more precisely. The argument that the market determines the oil price has little explanatory power.The above questions have assumed special importance in the last few years. The sharp swings in oil prices and the marked increase in volatility during the latest 2008-2009 price cycle have raised concerns about the impact of financial layers and financial investors on oil price behaviour.2 Some observers in the oil industry and in academic institutions attribute the recent behaviour in prices to structural transformations in the oil market. According to this view, the boom in oil prices can be explained in terms of tightened market fundamentals, rigidities in the oil industry due to long periods of underinvestment, and structural changes in the behaviour of key players such as non-OPEC suppliers, OPEC members, and non-OECD consumers.3On the other hand, other observers consider that the changes in fundamentals or even in expectations, have not been sufficiently dramatic to justify the extreme cycles in oil prices over the period 2008-2009. Instead, the oil market is seen as having been distorted by substantial and volatile flows of financial investments in deregulated or poorly regulated crude oil derivatives instruments.4The view that crude oil has acquired the characteristics of financial assets such as stocks or bonds has gained wide acceptance among many observers but is disputed by others.5Many empirical papers2 For a comprehensive overview, see Fattouh (2009).3 See, for instance, IMF (2008), World Economic Outlook (October), Washington: International Monetary Fund; Commodity Futures Trading Commission (2008), Interagency Task Force on Commodity Markets Interim Report on Crude Oil; Killian and Murphy (2010).4 See, for instance, the Testimony of Michael Greenberger before the Commodity Futures Trading Commission on Excessive Speculation: Position Limits and Exemptions,5 August 2009. Greenberger provides an extensive list of studies that are in favour of the speculation view.5 See, for instance, Yergin (2009). Yergin argues that the excessive …daily trading has helped turn oil into something new -- not only a physical commodity critical to the security and economic viability of nations but also a financial asset, part of that great instantaneous exchange of stocks, bonds, currencies, and everything else that makes up the world's financial portfolio‟.。

TEST 7READING PASSAGE 3You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40 which are based on Reading Passage 3 below.Sunset for the Oil Business?The world is about to run out of oil. Or perhaps not. It depends whom you believe …Members of Oil Depletion Analysis Centre (ODAC) recently met in London and presented technical data that support their grim forecast that the world is perilously close to running out of oil. Leading lights of this movement, including Colin Campbell, rejected rival views presented by American Geological Survey and the International Energy Agency (IEA) that contradicted their views. Dr Campbell even decried the “amazing display of ignorance, |deliberate ignorance, denial and obfuscation” by governments, industry and aca demics on this topic.So is the oil really running out? The answer is easy: Yes. Nobody seriously disputes the notion that oil is, for all practical purposes, a non-renewable resource that will run out some day, be that years or decades away. The harder question is determining when precisely oil will begin to get scarce. And answering that question involves scaling Hubbert’s peak.M. King Hubbert, a Shell geologist of legendary status among depletion experts, forecast in 1956 that oil production in the United States would peak in the early 1970s and then slowly decline, in something resembling a bell-shaped curve. At the time, his forecast was controversial, and many rubbished it. After 1970, however, empirical evidence proved him correct: oil production in America did indeed peak and has been in decline ever since.Dr Hubbert’s analysis drew on the observation that oil production in a new area typically rises quickly at first, as the easiest and cheapest reserves are tapped. Over time, reservoirs age and go into decline, and so lifting oil becomes more expensive. Oil from that area then becomes less competitive in relation to other sources of fuel. As a result, production slows down and usually tapers off and declines. That, he argued, made for a bell-shaped curve.His successful prediction has emboldened a new generation of geologists to apply his methodology on a global scale. Chief among them are the experts at ODAC, who worry that the global peak in production will come in the next decade. Dr Campbell used to argue that the peak should have come already; he now thinks it is just round the comer. A heavyweight has now joined this gloomy chorus. Kenneth Deffeyes of Princeton University argues in a lively new book that global oil production could peak within the next few years.That sharply contradicts mainstream thinking. America s Geological Survey prepared an exhaustive study of oil depletion last year that put the peak of production somedecades off. The IEA has just weighed in with its new World Energy Outlook, which foresees enough oil to comfortably meet demand to 2020 from remaining reserves. Rene Dahan, one of the ExxonMobil’s top managers, toes further: with an assurance characteristic of the world’s largest energy company, he insists that th e world will be awash in oil for another 70 years. Who is right? In making sense of these wildly opposing views, it is useful to look back at the pitiful history of oil forecasting. Doomsters have been predicting dry wells since the 1970s, but so far the oil is still gushing. Nearly all the predictions for 2000 made after the 1970s oil shocks were far too pessimistic.Michael Lynch of DRI-WEFA, an economic consultancy, is one of the few oil forecasters who has got things generally right. In a new paper, Dr Lynch analyses those historical forecasts. He finds evidence of both bias and recurring errors, which suggests that methodological mistakes (rather than just poor data) were the problem. In particular, he criticized forecasters who used Hubbert-style analysis for relying on fixed estimates of how much ultimately recoverable" oil there really is below ground. That figure, he insists, is actually a dynamic one, as improvements in infrastructure, knowledge and technology raise the amount of oil which is recoverable.That points to what will probably determine whether the pessimists or the optimists are right: technological innovation. The first camp tends to be dismissive of claims of forthcoming technological revolutions in such areas as deep-water drilling and enhanced recovery. Dr Deffeyes captures this end-of-technology mindset well. He argues that because the industry has already spent billions on technology development, it makes it difficult to ask today for new technology, as most of the wheels have already been invented.Yet techno-optimists argue that the technological revolution in oil has only just begun.Average recovery rates (how much of the known oil in a reservoir can actually be brought to the surface) are still only around 30-35%. Industry optimists believe that new techniques on the drawing board today could lift that figure to 50-60% within a decade.Given the industry s astonishing track record of innovation, it may be foolish to bet against it. That is the result of adversity: the oil crisis of the 1970s forced Big Oil to develop reserves in expensive, inaccessible places such as the North Sea and Alaska, undermining Dr Hubbert’s assumption that cheap reserves are developed first. The resulting upstream investments have driven down the cost of finding and developing wells over the last two decades from over $20 a barrel to around $6 a barrel. The cost of producing oil has fallen by half, to under $4 a barrel.Such miracles will not come cheap, however, since much of the world’s oil is now produced in ageing fields that are rapidly declining. The IEA concludes that global oil production need not peak in the next two decades if the necessary investments are made. So how much is necessary? If oil companies are to replace the output lost at tho se ageing fields and meet the world’s ever-rising demand for oil, the agency reckons they must invest $1 trillion in non-OPEC countries over the next decade alone. Ouch.Questions 27-31Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet, writeYES if the statement agrees with the informationNO if the statement contradicts the informationNOT GIVEN if there is no information on this27 Hubbert has a high-profile reputation amongst ODAC members.28 Oil is likely to last longer than some other energy sources.29 The majority of geologists believe that oil will start to run out some time thisdecade.30 Over 50 percent of the oil we know about is currently being recovered.31 History has shown that some of Hubbert’s principles were mistaken. Questions 32-35Complete the sentences below using NO MORE THAN ONE WORD OR NUMBER from the passage.Write your answers in boxes 32-35 on your answer sheet.Many people believed Hubbert’s theo ry was 32_________when it was originally presented.The recovery of the oil gets more 34______as the reservoir gets older.The oilfield can’t be as 35_____ as other areas.Questions 36-40Look at the following statements (Questions 36-40) and the list of people below;Match each statement with the correct person, A-E.Write the correct letter, A-E, in boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet.36 has found fault in geological research procedure.37 has provided the longest-range forecast regarding oil supply.38 has convinced others that oil production will follow a particular model.39 has accused fellow scientists of refusing to see the truth.40 has expressed doubt over whether improved methods of extracting oil are possible.A Colin CampbellB M. King HubbertC Kenneth DeffeyesD Rene DahanE Michael Lynch显示答案27 Yes28 Not Given29 No30 No31 Yes32 controversial33 tapped34 expensive35 competitive36 E37 D38 B39 A40 C题目详解Questions 27-3127.利用细节信息“Hubbert”和“ODAC”定位于原文第三段第一句话“M. King Hubbert,a Shell geologist of legendary status among depletion experts …”。

第43卷第5期2021年5月宜春学院学报Journal of Yichun UniversityVol.43*No.5May.2021汽油需求价格弹性的估计!基于48个研究的Meta分析焦雨生(武昌首义学院经济管理学院,湖北武汉430064)摘要:汽油对人类的生产和生活方式产生了重大的影响,因此关于汽油需求价格弹性的估计也成了能源研究领域的重点话题。

自上世纪50年代以来,大量的文献研究了汽油的短期和长期需求价格弹性,但估算的结果差异较大,甚至出现了截然相反的结论。

通过对1974年到2018年48篇涉及汽油需求价格弹性文献的系统编码,得到209个弹性估计值,包括113个短期弹性和96个长期弹性,在进行Meta分析后发现:短期和长期弹性合并分析后的平均值分别为-0.191和-0.647。

由于合并分析中的异质性较大,通过Meta回归分析发现:以短期和长期弹性为效应值的Mra回归分析效果较为理想;研究目标国、文献发表时间和研究方法对汽油需求价格弹性大小的研究存在显著影响;文献来源对汽油需求弹性大小的研究的影响不显著。

关键词:汽油;需求价格弹性;Mra分析中图分类号:F714.1文献标识码:A文章编号:1671-380X(2021)05-0049-08An Estimation of Price Elasticity of Gasoline Demand:Meta Analysis Based on48StudiesJIAO Yu一sheng(Department of Economics and Management*Wuchang Shouyi University*Wuhan430064,China) Abstract:Gasoline has a significant impact on human production and lifestyle,so the estimation of the price elasticity of oit demand has become a key topta in the field of enerry research.Since the1950s,a lag number of lim eratureo have studied the short一term and long一term demand price elasticity of gasoline,but the resulas are quite dmerena,and even the opposite results appear.Based on aie systematta coding of48literatures on the pace elasticity of gasoline demand from1974te2018,this papee obtaint209elasticity estimates,including113short-term and96long一term elasticity.After meta analysit,we found that tie average velue of short一term and long一term elasttc combination analysis was-0.191and-0.647,respectively.Due te the laree heterogeneity in the combined analysis,this papee uses meta reeression analysis and finds that:tte effect of meta reeression analysis wit short一term and long一term elasticity as the effect velue is relatively ideal;the resesrch tareee counay,literature publishing tirne and resesrch metiod have significont influenco on U c resesrch of gasoline demand peco elasticity; U c literature sourco has no signincont influenco on the research of gasoline demand elasticity.Key word:Gasoline;paco elasticity of demand;Meta analysis在当代经济中,汽油不仅是生产商品和服务的关键要素,而且是个人福利的直接来源,关于汽油需求价格弹性的估计也成了能源研究领域的重点话题。

美元汇率与国际油价走势相关性分析

张溢;王珂;姜霖

【期刊名称】《国际石油经济》

【年(卷),期】2014(022)005

【摘要】美元作为石油的定价货币,其汇率与油价有着天然的联系,两者在不同时期呈现不同的相关关系.2001年以后,政策监管的放松使得原油期货的投机活动越发活跃,美元和石油作为两种投资资产,由于替代作用而产生了更加显著的负相关关系.然而,油价持续上升带来的通胀压力可能导致美联储提高利率,造成美元升值,因此油价与美元汇率也可能呈正相关关系.将美国工业产出系数、联邦基金利率与OECD 商业库存水平这三个控制变量引入模型,对于2001年之后的数据进行协整检验,结果显示,原油价格对于美元实际有效汇率的长期弹性系数为-5,即美元每上升1%,油价下跌5%.

【总页数】9页(P55-63)

【作者】张溢;王珂;姜霖

【作者单位】中化石油有限公司;中化石油有限公司;中化石油有限公司

【正文语种】中文

【相关文献】

1.美元汇率:短期波动、中期趋势与长期命运——美元汇率决定要素的分期限研究与走势预测

2.英镑对美元汇率走势浅析

3.从意外反转走向区间震荡——2018年上半年美元汇率走势回顾与展望

4.国际油价大幅下跌回顾及2020年国际油价走势分析

5.美元汇率变动对国际油价的影响

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

投资者行为和市场流动性—基于中国股票市场停牌制度的实证研究*廖静池**,李平,曾勇(电子科技大学经济与管理学院, 成都610054)内容提要:本文使用2006年深圳A股市场的停牌和交易数据,从换手率、深度、价差和流动性比率等方面考察了停牌对投资者交易行为和市场流动性的影响。

研究结果表明,投资者的交易需求中除了有部分会因为停牌的到来而被推迟至复牌后实现外,另有部分交易需求则会被提前至停牌前实现。

停牌前股票的交易活跃程度显著高于非停牌日的情形,同时其流动性更高、交易成本更低;而在复牌后,尽管投资者的交易需求依然强烈,但是交易成本明显增加,市场流动性有所下降。

总体上看,中国股票市场的停牌缺乏效率,公告信息在停牌期间并没有完全释放。

关键词:停牌;复牌;投资者行为;流动性;中国股票市场Investor actions and market liquidity——An empirical study on trading halts mechanism on China stock marketsLiao Jingchi, Li Ping, Zeng Y ong(School of Management and Economics, University of Electronic Science and Technology of C hina, C hengdu 610054, China)Abstract: Using the trading and trading halts data of A-share stocks traded on Shenzhen Stock Exchange in 2006, this paper investigates the impacts of trading halts on investor actions and market liquidity in terms of turnover, depth, spread and liquidity ratio. The results show that, investors tend to advance their trading demand before the trading halts, while some trading demand would be postponed by the halts. Compared with the stocks without trading halts, the stocks before trading halts involve heavier transaction activities, more liquidity and less transaction costs. Furthermore, the stocks after trading halts have more trading demands, more transaction costs and less market liquidity than the stocks without trading halts. In summary, the trading halts of China stock markets are ineffective, and the notice information cannot be completely released during the trading halts periods. Key words: trading halts; resumption; investor action; liquidity; China stock markets一、引言2008年10月1日,深圳和上海证券交易所同时宣布,将在其推出的新版上市规则中对停牌制度实施改革。

战略与决策中国原油价格争取成为国际基准指标的进程研判中国原油价格争取成为国际基准指标的进程研判田洪志1,3,姚峰丨,2,罗浩1,李慧1(1.西北大学经济管理学院,陕西西安710127;2.曰本香川大学经济学部,曰本高松7608523;3.西北大学中国西部经济发展研究院,陕西西安710127)摘要:针对研判中国原油期货价格争取成为国际基准油价指标进程中遇到的理论支撑不足问题,基于多变量时间序列因果分析理论,提出国际基准油价指标的价格发现机制、价格影响机制与价格公认机制等概念。

计量经济分析结果显示:上海国际能源交易中心(IN E)油价在不同周期内均对北美原油市场的西德克萨斯(WTI)油价、欧洲原油市场的布伦特油价、东亚原油市场的东京商品交易所(T C E)油价等产生了显著的单方向因果影响,具备了影响机制;同时受到其他油价的单方向因果作用微小,正在逐步形成价格发现机制;在持仓量、媒体报道、学术征引等方面目前尚未获得价格公认机制。