房颤复律及控制心室率

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:192.00 KB

- 文档页数:57

房颤复律原则和时机、维持窦性心律和节律控制药物规范及特殊人群房颤处理事项节律控制是心房颤动综合管理的重要部分,能有效降低房颤负荷、减轻患者症状,在早期房颤中有改善预后的证据。

抗心律失常药物是节律控制策略的一线推荐。

房颤患者转复窦性心律1、房颤复律原则及时机血流动力学不稳定者(有意识障碍、休克、低血压、合并心衰、急性冠状动脉综合征或预激综合征等)首选电复律;血流动力学稳定者可先尝试药物复律。

血流动力学稳定但药物转复无效或仍有不可耐受症状的患者,推荐电复律。

大多数阵发性房颤急性发作可在1-2 d内自行转复,房颤持续时间越长,转复成功率越低且血栓形成的风险越大。

复律时机应根据患者症状的严重程度、是否已服抗凝剂、房颤持续时间、既往栓塞病史及CHA2DS2-VASc评分等决定2、房颤复律中AADs的选择可用于房颤复律的AADs有Ⅰc类和Ⅲ类。

射血分数下降的心衰只能选择胺碘酮;对于有瓣膜病、冠状动脉疾病、射血分数保留的心衰或射血分数轻度降低的心衰及左心室肥厚房颤患者应用决奈达隆复律;对于无器质性心脏病的房颤患者应用氟卡尼、伊布利特、普罗帕酮及维纳卡兰复律。

3、“口袋药”复律对于有症状的阵发性房颤患者,症状发作不频繁,并已在医院通过监测确认药物的安全性和有效性,患者可在家中自行服用单剂量Ⅰc类AADs转复窦性心律,此类方案称为“口袋药”复律策略。

➤适应证:房颤发作≥2 h,频率<1次/月;房颤发作期间无晕厥、严重胸痛或呼吸困难等严重症状。

➤禁忌证:严重的结构性心脏病,如左室射血分数(LVEF)<50%,缺血性心脏病或严重的左室肥厚;异常的心电传导;收缩压<100 mmHg (1 mmHg=0.133 kPa)。

➤用法用量:顿服,氟卡尼200-300 mg或普罗帕酮450-600 mg。

部分患者可能发生心动过速,提前30min口服β受体阻断剂。

➤出现的不良反应:严重心动过缓、低血压、传导阻滞。

房颤患者心室率控制目标与方法心房颤动是临床上最常见的心律失常,近年国内外流行病学资料显示普通人群中房颤的患病率约为0.4%~1.0%,估计我国现有约1000万房颤患者,其中1/3为阵发性房颤,2/3为持续或永久性房颤。

房颤不仅降低了患者的生活质量,还可引起脑和肢体重要脏器栓塞,诱发或恶化心力衰竭,增加死亡率。

房颤治疗的关键就在于减少脑栓塞及死亡的发生率,提高患者的生活质量。

现有的资料并不能直接证实心率控制可减少脑栓塞及死亡的发生率,仅是推测房颤室率的控制,可减少或延缓心衰发生的可能性及严重程度,从而降低脑栓塞及死亡发生的概率,缺少大规模临床实验的证实。

目前对房颤治疗的评价多来源于血流动力学的改善,减少心功能的恶化,增加心输出量及患者的主观症状。

而房颤患者室率的控制对改善症状、提高生活质量以及减少心衰发生率等方面确实有良好的效果【1】。

对房颤患者室率的控制,目前主要存在两种治疗方式,即节律控制或是心率控制。

虽然在理论上,维持窦性心律的临床益处大于控制心室率,但是多项临床研究均没有证实节律控制患者在病死率、住院率、脑卒中等方面优于室率控制【2, 3】。

其原因一方面可能是抗心律失常药物的不良反应降低了窦性节律维持带来的益处;另一方面,在各研究中,节律控制未能完全实现窦律的维持。

本文主要讨论有关室律控制的目标及方法。

1房颤心室率控制的目标所谓心室率控制,就是允许房颤存在的同时将心室率控制在一定范围内。

心房颤动时心室率的快慢与房室结不应期、交感和副交感神经张力及其本身的传导特性有关。

任何能有效延长房室结不应期的药物或是干预房室节传导的措施都可能用于室率的控制。

根据2022年AHA/ACC/ESC以及NICE指南,建议静息时室率控制在60~80次/min,中度运动时控制在90~115次/min【4】。

但事实上,这个数据很大程度上是对房颤患者短期血流动力学改善的观察上得出的,并没有一个很严格的方法来评价这个数值的可靠性。

房颤最好治疗方法:药物治疗方法,药物能恢复或者在一定程度维持心律,且控制并发症得发生。

常用的药物有β受体阻滞剂、洋地黄以及胺碘酮等。

药物治疗的好处是可以控制心室率,并且保证心脏的基本功能,同时降低心房颤动引起的心功能紊乱。

非药物治疗的方法有电复律或者导管消融治疗、以及抗凝治疗等。

抗凝治疗一定要有专业医生来指导,抗凝过度会引发出血,抗凝强度不够就没有疗效,所以千万要谨慎。

一般情况下非药物治疗的创伤比较大,一旦治疗失败,就需要立即使用药物来治疗。

但是无论选择何种方法来治疗心房颤动,其治疗原则都是要恢复窦性心律,这样才能达到应有的治疗效果,所以所有房颤的患者都必须恢复正常心率。

对于那些不可能将心律恢复到正常水平的患者,可以先通过药物把心率降下来,然后继续使用抗凝药物,以防止脑卒中或者血栓形成的发生。

所以,不难看出房颤这种类型的心律不齐对于很多人来说都是比较严重的情况,所以遇到这种情况一定要到附近的大医院进行稳定治疗,防止出现更严重的疾病。

患有房颤这种病的患者通常都是心律过快,相比起正常人来说要快很多,房颤的发病原因也有很多,通常情况下都是与心脏疾病有关,但同时也与压力过大有关系,而上述文章中所介绍的治疗房颤的方法都是经过实践而得来的。

1、药物治疗目前药物治疗依然是治疗房颤的重要方法,药物能恢复和维持窦性心律,控制心室率以及预防血栓栓塞并发症。

转复窦性心律正常节律药物:对于新发房颤因其在48小时内的自行复窦的比例很高24小时内约60%,可先观察,也可采用普罗帕酮或氟卡胺顿服的方法。

房颤已经持续大于48小时而小于7天者,能用静脉药物转律的有氟卡胺、多非利特、普罗帕酮、伊布利特和胺碘酮等,成功率可达50%。

房颤发作持续时间超过一周持续性房颤药物转律的效果大大降低,常用和证实有效的药物有胺碘酮、伊布利特、多非利特等。

控制心室率频率控制的药物:控制心室率可以保证心脏基本功能,尽可能降低房颤引起的心脏功能紊乱。

常用药物包括:1β受体阻滞剂:最有效、最常用和常常单独应用的药物;2钙通道拮抗剂:如维拉帕米和地尔硫卓也可有效用于房颤时的心室率控制,尤其对于运动状态下的心室率的控制优于地高辛,和地高辛合用的效果也优于单独使用。

心房颤动是临床上常见的心律失常之一,其发生率随年龄增长而增高,成人心房颤动发生率为0.3〜0.4% , 60岁以上发生率为2.0〜4.0% , 75岁以上发病率高达8.0〜11.0% 心房颤动可导致心排血量下降、心衰、血栓栓塞等严重合并症,因此面对大量的房颤病人,如何治疗并避免合并症成为治疗的关键。

颤均由心房内多源性折返所致,即心房内存在3〜6个以上颤动即不再维持,而且房颤发生的直接原因90%是因房性早搏的出现,所以治疗的重点应在于预防房早的出现和打断心房内折返。

纵观多年来治疗房颤的传统方法和近年来治疗房颤的新进展,其原则及方法不外乎以下几个方面:■控制心室率在合理范围达90〜115次/分为宜。

根据病情不同治疗也不相同。

1、心室率快伴严重低血压或肺水肿的房颤病人,急用同步直流电转复,具体方法见后。

脉给药,常用毛地黄类、B受体阻滞剂、钙离子拮抗剂。

女口:西地兰0.4 〜0.8mg静推,美托洛尔 5 〜15mg静推(心功能不全者慎用),硫氮酮10mg静推(对毛地黄类难以控制的肺部疾患、交感神经兴奋、发热等状态时的房颤心室率有较好的效果)。

480mg , qd,或氨酰心安25〜100mg , qd(降低活动后心室率)或地高辛0.1〜0.25mg , qd(降低休息时心室率)。

4.对药物治疗后仍有症状性的心室率快的房颤病人采用介入治疗。

■、恢复窦性心律:1、同步直流电转复:对于经过治疗或未经治疗心室率控制良好者以及无症状或症状轻微者不必考虑;对于恶性肿瘤、麻醉高危者、伴有严重器官功能障碍者、房颤持续数年者、左房内径大于60mm者不予考虑。

首次电转复能量为200焦,若不成功,可增加至360焦,可连续电击3次。

应在心电监护和有良好抢救设备的条件下进行复律,复律前应空腹6小时,同时给予抗凝治疗(具体方法见后)。

转复率在90%左右。

但是它的使用有时受到限制,如患者认为有2、药物转复:首先la类抗心律失常药物奎尼丁,因为是传统药物,使用上有许多经验,一般病例选择好后给药3天,从中午12点给药,第一天0.2g/次,第二天0.3g/次,第三天0.4g/次,间隔2小时给药一次,每天共5次,转为窦性心律后随时停药,第三天服药后仍未转复,停止给药。

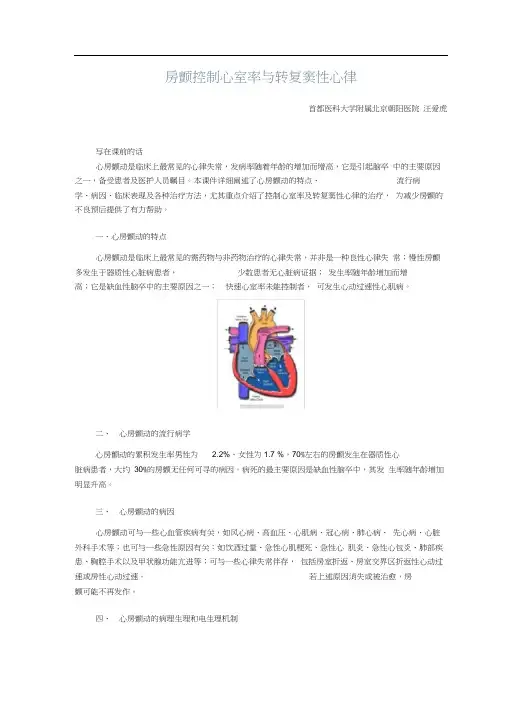

房颤控制心室率与转复窦性心律首都医科大学附属北京朝阳医院汪爱虎写在课前的话心房颤动是临床上最常见的心律失常,发病率随着年龄的增加而增高,它是引起脑卒中的主要原因之一,备受患者及医护人员瞩目。

本课件详细阐述了心房颤动的特点、流行病学、病因、临床表现及各种治疗方法,尤其重点介绍了控制心室率及转复窦性心律的治疗,为减少房颤的不良预后提供了有力帮助。

一、心房颤动的特点心房颤动是临床上最常见的需药物与非药物治疗的心律失常,并非是一种良性心律失常;慢性房颤多发生于器质性心脏病患者,少数患者无心脏病证据;发生率随年龄增加而增高;它是缺血性脑卒中的主要原因之一;快速心室率未能控制者,可发生心动过速性心肌病。

二、心房颤动的流行病学心房颤动的累积发生率男性为 2.2%、女性为1.7 %,70%左右的房颤发生在器质性心脏病患者,大约30%的房颤无任何可寻的病因。

病死的最主要原因是缺血性脑卒中,其发生率随年龄增加明显升高。

三、心房颤动的病因心房颤动可与一些心血管疾病有关,如风心病、高血压、心肌病、冠心病、肺心病、先心病、心脏外科手术等;也可与一些急性原因有关:如饮酒过量、急性心肌梗死、急性心肌炎、急性心包炎、肺部疾患、胸腔手术以及甲状腺功能亢进等;可与一些心律失常伴存,包括房室折返、房室交界区折返性心动过速或房性心动过速。

若上述原因消失或被治愈,房颤可能不再发作。

四、心房颤动的病理生理和电生理机制有关心房颤动的电生理机制学说有异位局灶自律性增强学说(Scherf等,1953)、多个子波折返激动学说(Moe等,1959),也可能与触发因素如房早、房扑、房速、AVNRT AVRT交感或迷走神经功能亢进等有关,或与组织与电学基质相关。

心房颤动的病理组织学有三种情况:心房扩张和不均匀分布的纤维化(窦房结),见于器质性心脏病;非特异的散在纤维化,继发于全身性疾病;心房肌细胞离子通道的功能异常或未识别的非病理性结构异常,发生于健康人的阵发性房颤(孤立性房颤)。

(200mg/day). In case of recurrent atrial fibrillation,therapy was left to the treating physician. All patients wereanticoagulated throughout the entire study period(international normalised ratio of 2·0–3·0). The trial wasdone at 21 investigational sites throughout Germany. Thestudy protocol was approved by the local ethicscommittees of participating centres. All patients gavewritten informed consent before randomisation. Eligibility criteriaPatients aged 18 to 75 years presenting with symptomaticpersistent atrial fibrillation of between 7 days and 360days duration were eligible. The following exclusioncriteria were applied: congestive heart failure, New YorkHeart Association (NYHA) class IV; unstable anginapectoris; acute myocardial infarction within 30 days; atrialfibrillation with an average rate of fewer than 50 beats perminute (BPM); known sick-sinus syndrome; atrialfibrillation in the setting of Wolff-Parkinson-Whitesyndrome; coronary artery bypass graft surgery or valvereplacement within the past 3 months; echocardiographicdocumentation of intracardiac thrombus formation;central or peripheral embolisation within the past3months; hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; amiodaronetherapy within the past 6months; acute thyroiddysfunction; pacemaker therapy; contraindications forsystemic anticoagulation therapy; pregnancy.Follow-upAll randomised patients were followed for 12 months withregular visits scheduled for 3 weeks, and 3, 6, and12months after randomisation. Patients were advised tocall at any time if they experienced new symptoms.Study proceduresAt baseline and at follow-up visits, patients underwentone-dimensional and two-dimensional echocardiography,resting electrocardiographic documentation, 24 h Holtermonitoring, and a 6 min walk test. In addition, quality oflife was assessed by the Medical Outcomes Study short-form health survey (SF-36) questionnaire at baseline andafter 12 months.10The SF-36 is a standardised generichealth-survey instrument that has been carefully validatedand has been extensively used in arrhythmia-relatedstudies.11–13Study endpointsSince atrial fibrillation is not necessarily an arryhthmiawith prognostic implications, we used as the main studyoutcome improvement in atrial-fibrillation-relatedsymptoms. Specifically, this endpoint was assessed duringeach follow-up visit by the changes compared withbaseline in the three most frequently reportedsymptoms—palpitations, dyspnoea, and dizziness.14–18Symptomatic improvement was defined (in hierarchicalorder) as either an elimination of palpitations (if present atbaseline), or a reduction in the frequency of episodes ofdyspnoea (if palpitations were not eliminated), or areduction in the frequency of dizzy spells (if palpitationswere not eliminated and dyspnoea was unchanged). Incases where no palpitations were present at baseline,symptomatic improvement was defined as continuedabsence of palpitations and an improvement in dyspnoeaor dizziness, as described above. These symptoms werecarefully assessed by interviews in every patient. We didnot use a specifically designed scoring system whenassessing these symptoms. Another common atrial-fibrillation-related symptom is “easy fatigability”.In group A, 30 (24%) out of 125 patients were admitted to hospital at least once compared with 87 (69%) out of 127 group-B patients (p=0·001). The most frequent cause for hospital admission in group B was admission for electrical cardioversion (67% of all hospital admissions) or for amiodarone-associated unwanted effects (27%). In group A, most admissions were due to unwanted drug-related side-effects (68%).Quality of lifeIn both treatment groups, measures of quality of life were significantly lower at baseline compared with the US norm obtained in individuals with sinus rhythm (table 2).11At the end of the observation period, most measures had improved but there were no significant differences between the two treatment strategies.Tolerance and safety of study medicationsAt least one drug-related side-effect was seen in 58 (47%) out of 125 group-A patients compared with 80 (64%) out of 127 group-B patients (p=0·011). The most frequently encountered diltiazem-associated side-effect was the occurrence of peripheral oedema (17 patients). The most frequently encountered amiodarone-related side-effects were corneal dispositions (ten patients), thyroid problems (seven patients), and photosensitivity (seven patients). In group A, treatment was prematurely stopped due to side-effects in 17 (14%) patients compared with 31 (25%) patients in group B (p=0·036).DiscussionPIAF is the first randomised multicentre trial to compare two different therapeutic strategies, rate versus rhythm control, in patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation. The results indicate that neither of the two therapeutic strategies is superior in terms of improvement in atrial-fibrillation-related symptoms. The results may have important implications for the care of individual patients who are treated mainly for symptomatic reasons in most cases.For many years, rhythm control has been regarded as the preferred therapy of many physicians for atrial fibrillation. The proposed advantages are that it avoids the necessity of anticoagulation therapy, produces symptomatic relief, and may improve survival.3,8In PIAF, amiodarone pharmacologically restored sinus rhythm in 23% of patients, the remaining majority undergoing at least one direct current cardioversion. Our study confirms previous uncontrolled studies indicating modest converting efficacy of amiodarone and a delay in effect. The PIAF trial shows that 56% of patients who were successfully cardioverted and could be maintained in sinus rhythm on continued low-dose amiodarone treatment over the observation period. This percentage was smaller than expected. When PIAF was designed it was estimated the maintenance rate would be about 70%. The Canadian Trial of Atrial Fibrillation (CTAF) found a maintenance rate of 69% in its amiodarone treatment arm.21The reasons for the lower efficacy rate observed in PIAF are not entirely clear. However, amiodarone was discontinued in 25% of patients due to presumed side-effects. This finding suggests that physicians may be more likely to stop amiodarone when given for a presumably less severe arrhythmia such as atrial fibrillation, even if there is only a vague suspicion of drug-induced side-effects. When amiodarone is given for serious ventricular tachyarrhythmias, the discontinuation rate is lower asobserved in the Antiarrhythmics Versus ImplantableStudy Hamburg (CASH).23There was no report of apotential amiodarone-associated proarrhythmic effect inPIAF, which confirms previous uncontrolled andcontrolled observations.24PIAF patients randomised to rhythm control had abetter exercise tolerance compared with patients whounderwent rate control. This finding may be due toimprovement in haemodynamics after restoration of sinusrhythm as shown previously.25,26However, this improvedexercise tolerance did not translate to an overall improvedquality of life when both treatment groups werecompared. The latter finding is in agreement withpreliminary data from a trial assessing quality-of-lifechanges associated with various treatments of atrialfibrillation.13Rate control has the advantage that antiarrhythmic drugtherapy, and hence its potential side-effects, can beavoided. Furthermore, whereas antiarrhythmic drugtreatment is often initiated in hospital,27this is notmandatory when the aim is only rate control. However,this treatment strategy implies the necessity of permanentanticoagulation.In PIAF, symptomatic improvement was similar inpatients randomised to rate control. This finding re-emphasises the point that careful control of the ventricularrate in atrial fibrillation can result in a substantial benefitfor the patient.8Most of our patients were on digoxintherapy at baseline, which reflects common clinicalpractice in Germany. The addition of diltiazem led to asmall but significant further decrease in mean heart rate.Accordingly, ventricular rate was well controlled by thiscombination in most patients. In fact, cathetermodification of atrioventricular node conduction tocontrol the rate was done in just five patients.The strategy of rate control was associated withsignificantly fewer hospital admissions in our patients,which shows that rate control in atrial fibrillation may beassociated with significant cost-savings—a fact that isparticularly relevant given the number of people who havethis rhythm disturbance.A potential limitation of this study is that electricalcardioversion in patients randomised to rhythm controlwas required per protocol only once with subsequenttreatment left to the treating physician. Repeatedcardioversions may have led to a higher percentage ofpatients in sinus rhythm. Similarly, only amiodaronetherapy was prescribed to maintain sinus rhythm.Although this drug has been found to be superior tosotalol or propafenone for this indication,21some patientsmay have favourably responded to one of these agents.Moreover, in patients randomised to rhythm control inwhom sinus rhythm could not be maintained, no uniformapproach to control rate had been predefined. This maybe a limitation of a “strategy trial” like PIAF. Accordingly,rate control may have been pursued less vigorouslyresulting in less symptomatic improvement.A specifically designed scoring system for assessingchanges in atrial-fibrillation-related symptoms was notpart of the study protocol. It is conceivable, however, thatwith the use of a prospectively validated scoring systemthe change in symptomatic status could have beenassessed even more precisely.Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that oursample size was too small to detect significant differencesbetween the two treatment strategies.Similar improvements in atrial-fibrillation-relatedsymptoms were seen in the PIAF trial for rate of rhythmcontrol of atrial fibrillation. Until larger trials such as the13Jung W, Herwig S, Newman D, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on quality of life: a prospective, multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol1993;33:104A (abstr).14Bhandri AK, Anderson JL, Gilbert EM, et al. Correlation of symptoms with occurrence of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia or atrial fibrillation: a transtelephonic monitoring study. Am Heart J 1992;124:381–86.15Prystowsky EN, Margiotti R, Fogel R, Evans JJ, Freedberg N, Shaar C. Atrial fibrillation with and without heart disease:clinical characteristics and proarrhythmia risk. Circulation1996:94:191.16Levy S, Marek M, Cournel P, et al, on behalf of the French Cardiologists. Characterization of different subsets of atrial fibrillation in general practice in France: the ALFA study. Circulation1999;99: 3028–35.17Brignole M, Menozzi C, Gianfranchi L, et al. Assessment of atrioventricular junction ablation and VVIR pacemaker versuspharmacological treatment in patients with heart failure and chronic atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled study. Circulation1998;98: 953–60.18Lee S, Chen A, Tai C, et al. Comparisons of quality of life and cardiac performance after complete atrioventricular junction ablation andatrioventricular modification in patients with medically refractory atrial fibrillation.J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:637–44.19Hohnloser SH. Indications and limitations of class II and III antiarrhythmic drugs in atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol1994;17:1019–25.20Lundström T, Ryden L. Ventricular rate control and exercise performance in chronic atrial fibrillation: effects of diltiazem andverapamil.J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;16:86–90.21Roy D, Talajic M, Dorian P, et al. Amiodarone to prevent recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Canadian Trial of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators.N Engl J Med 2000;342:913–20.22The Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators. A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy withimplantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated fromnear-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1576–83.23Kuck KH, Cappato R, Siebels J, Rüppel R, for the CASH Investigators. A randomized comparison of antiarrhythmic drugtherapy with implantable defibrillators resuscitated from cardiac arrest: the Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg (CASH). Circulation2000;102: 748–54.24Hohnloser SH, Klingenheben T, Singh BN. Amiodarone-associated pro-arrhythmic effects: a review with special reference to torsade de pointes tachycardia. Ann Int Med 1994;121:529–35.25Atwood JE, Myers J, Sullivan M, Forbes S, Sandhu S, Callaham P, Froelicher V. The effect of cardioversion on maximal exercise capacity in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 1988;118:913–18.26Gosselink ATM, Crjns HJGM, van den Berg MP, et al. Functional capacity before and after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: acontrolled study. Br Heart J 1994;72:161–66.27Myerburg RJ, Kloosterman M, Yamamury K, Mitrani R, Interian A, Castellanos A. The case for inpatient initiation of antiarrythmictherapy.J Cardiovasc Electrophys 1999;10:482–87.28The Planning and Steering Committees of the AFFIRM Study for the NHLBI AFFIRM Investigators. Atrial fibrillation follow-upinvestigation of rhythm management—the AFFIRM study design.Am J Cardiol 1997;79:1198–202.。

房颤心室率控制目标房颤是一种常见的心律失常,特征是心房不规则收缩,导致心室跟随不规则收缩,从而引起心室率增快。

心室率控制是房颤管理的一个关键目标,旨在将心室率保持在适当的范围内,以减轻症状、改善心功能并预防并发症的发生。

一般来说,房颤患者的心室率控制目标为60-100次/分钟。

然而,不同的患者可能有不同的心室率控制目标,如下所示:1. 年轻患者:年轻的房颤患者通常拥有较高的心室率耐受能力,因此目标心室率可以设定在60-80次/分钟。

2. 年长患者:对于年长或有其他心血管疾病的患者,由于机体代谢和心肌收缩功能可能下降,心室率控制目标可设置为60-90次/分钟。

3. 合并心力衰竭或其他心血管并发症的患者:对于有心力衰竭或其他心血管并发症的患者,心室率控制目标应更为严格,维持在60-80次/分钟。

值得注意的是,心室率控制目标的确定应结合患者的具体情况和病情严重程度来制定。

在制定目标时,还需要考虑患者的心功能、症状以及对药物治疗的耐受性。

在实际操作中,常用的心室率控制措施包括药物治疗和电生理治疗。

药物治疗主要包括β受体阻滞剂、钙通道阻滞剂和数字化治疗等,这些药物可以通过减慢窦房结传导速度和延长AV节点传导时间来降低心室率。

在选择药物时,需要考虑心功能、肾功能以及可能的药物相互作用等因素,以确保治疗的安全性和有效性。

电生理治疗主要是通过导管射频消融术或介入式射频消融术来改善房颤患者的心室率控制。

这些治疗方法可以选择性地破坏心房和心室之间的传导路径,以减少快速的心房电活动传导到心室的可能性。

在房颤心室率控制时,需要密切监测患者的心室率,并根据实际情况调整药物剂量。

此外,还要注意可能出现的药物不良反应和药物相互作用,以确保患者的安全。

总结而言,房颤心室率控制目标的设定应根据患者的具体情况、病情严重程度和心功能等因素来确定。

在制定目标时,需要综合考虑患者的个体差异和治疗所能达到的效果,以最大限度地改善患者的生活质量和预防并发症的发生。

心房颤动节律控制总体原则、药物使用、AADs转复窦性心律、房颤复律后维持窦性心律、特殊人群房颤疾病类型和处理措施节律控制总体原则1.症状驱动节律控制房颤节律控制必须在综合管理的基础上进行,包括对有指征者进行抗凝治疗以及基础疾病和危险因素控制等。

AADs节律控制策略的主要目的是消除或减轻症状,提高生活质量,可根据房颤症状评分辅助节律控制治疗决策。

症状在2b及以上者,有指征可考虑节律控制。

2.早期节律控制房颤确诊后应尽早启动节律控制策略。

对仅表现为疲乏或运动耐量下降、缺乏房颤特异性症状的患者,可行试验性复律治疗,因较难辨别房颤与其症状间的关联。

试验性复律治疗有助于判断此类患者的症状是否由房颤所致,若患者症状有所改善,节律控制可作为首选治疗方案。

当决定放弃节律控制策略而采用心室率控制策略时,应停用AADs。

症状驱动节律控制和早期节律控制建议:1.症状性房颤患者结合其意愿,应用AADs和/或导管消融进行节律控制,特别是具备以下临床特征的患者:年轻、初发房颤或房颤病程较短、房颤相关心动过速性心肌病、心房内径正常或稍大/房内电传导正常或稍延缓、室率控制症状缓解不佳。

2.诊断1年内的无症状性房颤,合并CHA2DS2 -VASc ≥ 2分,结合患者意愿,尽早进行节律控制治疗,治疗策略包括AADs和消融。

节律控制药物1.氟卡尼和普罗帕酮氟卡尼和普罗帕酮为Ⅰc 类 AADs,可阻断心脏Na+通道,延长有效不应期,减慢心房和心室内传导,延长QRS波时程及H-V间期。

Ⅰc类药物对急性房颤转复作用强。

氟卡尼和普罗帕酮可用于左心室功能正常、无明显左心室肥厚和心肌缺血的房颤患者转复和维持窦性心律。

口服单剂量可在医院外用于终止发作不频繁、药物耐受性良好、无严重心脏病患者的房颤发作。

静脉注射较口服药物起效更快。

增加剂量疗效更佳,但会引起更多的不良反应。

Ⅰc类AADs治疗过程中,如房颤转换为房扑,常可致1︰1房室下传诱发快速心室率,故建议同时使用阻断房室结药物,但需注意有负性肌力、负性频率及房室传导阻滞的风险。

房颤心室率控制标准

房颤时,静息状态下心室率一般应控制在90次/分以下,运动状态下心室率应控制在110次/分以下。

不过,近年来对于这一标准已经不再那么严格,可以笼统地认为房颤的心室率控制在100次/分以下即可。

对于永久性房颤的患者,一般建议心室率控制在70~80次/分。

请注意,以上信息仅供参考,并不构成专业的用药建议。

如果有房颤相关的问题,建议及时咨询医生或专业人士。

另外,房颤时心室率过快可能会导致一系列严重后果,包括心脏扩大、心动过速心肌病、肺静脉压升高等。

因此,必须有效控制房颤的心室率。

2020ESC房颤诊断和管理指南解读:选择节律控制、室率控制(全文)房颤是临床上最常见的心律失常之一,能明显增加死亡、中风、心力衰竭、认知功能障碍、抑郁、生活质量下降和住院的风险。

阵发性房颤可以进展为持续性房颤,由于房颤相关的不适症状、加重心脏功能恶化、引发缺血性卒中和/或抗凝所致的严重出血事件,均可导致患者反复住院或门诊治疗,不仅增加医疗费用,同时也可增加患者致残和致死风险,故房颤是一个重大的健康和社会经济负担。

房颤的处理包括抗凝治疗预防卒中、节律和室律控制症状、治疗合并疾病和危险因素等。

本文主要讨论房颤的节律和室律控制相关内容。

一.房颤的节律与室律控制的药物治疗比较:房颤的节律控制指在充分室率控制、抗凝治疗和综合心血管疾病和/或危险因素预防治疗基础上进行抗心律失常药物(AAD)治疗、心脏电复律、导管消融治疗恢复和维持窦性心律。

房颤的节律与室律控制的优劣之争在AAD治疗时代长期没有定论,关于房颤AAD节律控制和单纯室率控制相比较的几项临床试验(如AFFIRM、RACE、STAF、AF-HeFT等研究)结果显示,AAD维持窦律的比例不高,与室率控制相比无明显获益。

然而,需要注意的是,AAD进行节律控制的临床研究均有一定的局限性:(1)AAD成功维持窦律比例较低,且维持窦律改善临床结局被AAD的毒副作用所稀释。

而在AFFIRM等临床试验中,患者若能维持窦律,则能改善临床结局。

(2)随机临床试验存在患者选择偏倚,如仅纳入具有治疗意愿的患者,其中包括较多维持窦律失败的患者,此类患者长期维持窦律的可能性较小。

(3)随机临床试验的随访时间均偏短,有研究显示节律控制组直到第五年才体现出临床获益。

(4)部分临床试验中,由于节律控制组停用口服抗凝药的比例较高,导致缺血性卒中事件增多。

总之,维持窦律策略之所以未显示出优势,很可能在于缺乏真正安全、有效的节律控制策略。

二.房颤导管消融与AAD室律控制比较:近年来,房颤导管消融取得了迅速的发展,一些小规模临床试验如CACAF、RAAFT、APAF以及4A等研究结果表明,导管消融比传统AAD 明显减少房颤复发。