The Influence of scenario constraints on the spontaneity of speech A comparison of dialogue

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:97.76 KB

- 文档页数:5

正交实验英语Orthogonal experimentation is a statistical method that is part of the design of experiments. It allows researchers to study the effect of multiple factors on a response variable with a reduced number of experiments. This method is particularly useful in situations where testing all possible combinations of factors is impractical due to time or cost constraints.The essence of orthogonal experimentation lies in its use of orthogonal arrays, which are special matrices that ensure each factor is tested at all levels an equal number of times. By doing so, it minimizes the influence of variables not being studied and allows for the isolation of each factor's effect on the outcome.Consider a scenario where a manufacturer wants to determine the optimal combination of materials and processes to produce the most durable product. Traditional experimentation might require testing every possible combination, which could be time-consuming and expensive. However, with orthogonal experimentation, the manufacturer can select a few representative combinations that will provide insights into how each factor affects durability.The process begins with the selection of factors and levels. For instance, if the manufacturer is testing three materials (A, B, C) and two processes (X, Y), they would have a total of six combinations to test. An orthogonal array can reduce this number by selecting a subset that still provides a full picture of the interactions between materials and processes.Once the experiments are conducted, the data collected is analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). This statistical technique breaks down the observed variance in the results into components attributable to each factor and their interactions. The analysis reveals which factors have a significant impact on the response variable and to what extent.The benefits of orthogonal experimentation are manifold. It provides a systematic approach to experimentation, reduces the number of experiments needed, and offers a clear understanding of the factors that influence the outcome. This method is widely used in various fields, including manufacturing, agriculture, and marketing, to optimize processes and products.In conclusion, orthogonal experimentation is a powerful tool for researchers and practitioners. It enables efficient exploration of the effects of multiple factors on a response variable, leading to better decision-making and optimization of processes and products. The method's reliance on statistical principles ensures that the conclusions drawn are robust and reliable, making it an indispensable part of the experimenter's toolkit.。

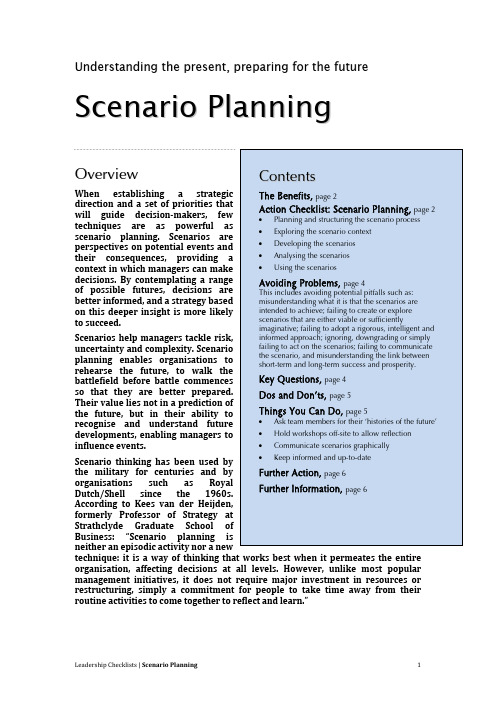

U n d e r s t a n d i n g t h e p r e s e n t , p r e p a r i n g f o r t h e f u t u r eS c e n a r i o P l a n n i n gO v e r v i e wWhen establishing a strategic direction and a set of priorities that will guide decision makers, few techniques are as powerful as scenario planning. Scenarios are perspectives on potential events and their consequences, providing a context in which managers can make decisions. By contemplating a range of possible futures, decisions are better informed, and a strategy based on this deeper insight is more likely to succeed.Scenarios help managers tackle risk, uncertainty and complexity. Scenario planning enables organisations to rehearse the future, to walk the battlefield before battle commences so that they are better prepared. Their value lies not in a prediction of the future, but in their ability to recognise and understand future developments, enabling managers to influence events.Scenario thinking has been used by the military for centuries and by organisations such as RoyalDutch/Shell since the 1960s. According to Kees van der Heijden, formerly Professor of Strategy at Strathclyde Graduate School of Business: “Scenario planning is neither an episodic activity nor a newtechnique: it is a way of thinking that works best when it permeates the entire organisation, affecting decisions at all levels. However, unlike most popular management initiatives, it does not require major investment in resources or restructuring, simply a commitment for people to take time away from their routine activities to come together to reflect and learn.”T h e B e n e f i t sUnderstanding the present. Scenariothinking helps provide a betterunderstanding of how different factorsaffecting a business affect each other. Itcan reveal linkages between apparentlyunrelated factors and, most importantly,it can provide greater insight into theforces shaping the future, delivering real competitive advantage. Overcoming complacency. Scenariosshould be designed to challengeestablished views, overcoming‘business‐as‐usual’ thinking andenabling established formulas and newideas to be tested. Seeing reality fromdifferent perspectives mitigates thepitfalls of groupthink, procrastination,hindsight bias, bolstering commitmentto failing strategies and shiftingresponsibility.Promoting action and ownership ofthe strategy process. Scenario thinkinghelps break the constraints on traditional strategic practices as it enables those involved to discuss the complexity and ambiguity of their perspectives in a wide context. Stimulating creativity and innovation. Scenarios encourage the opening of minds to new possibilities and the excitement of how they may be realised. The process leads to a positive attitude that actively seeks the desired outcome.Promoting learning. Scenarios helppeople to understand theirenvironment, consider the future, shareknowledge and evaluate strategic options. Information is better evaluated and integrated in the scenario planning process, which enables those involved in it to recognise and react to emerging circumstances.Creating a shared view. Scenariothinking works because it looks beyondcurrent assignments, facts andforecasts. It allows discussions to bemore uninhibited and it creates theconditions for a genuinely effectiveshared sense of purpose to evolve.Getting support for strategic decisionsrequires involving those that matter inthe scenario planning process.A c t i o n C h e c k l i s t:S c e n a r i o P l a n n i n gThe scenario thinking process is not oneof linear implementation, itseffectiveness lies in stimulatingdecisions, what is termed the strategic conversation. This is the continuousprocess of planning, analysing theenvironment, generating and testingscenarios, developing options, selecting,refining and implementing – a processthat is itself refined with furtherenvironmental analysis.P l a n n i n g a n d s t r u c t u r i n g t h es c e n a r i o p r o c e s sThe first stage is to identify gaps inorganisational knowledge that relatespecifically to business challengeswhose impact on the organisation isuncertain. To do this, create a team toplan and structure the process. Theteam should probably come fromoutside the organisation and its members should be noted for their creative thinking and ability to challenge conventional ideas. An external team is better placed to provide objective support, free from internal agendas or tensions. In discussion with the team, then decideon the duration of the project; tenweeks is considered appropriate for abig project.Scenarios may not predict the future but they do illuminate the causes of change – helping managers to take greatercontrol when conditions shift. What determines an organisation’s success is not simply how much it knows, but how it reacts to what it does not know.E x p l o r i n g t h e s c e n a r i o c o n t e x t Team members should be interviewedto highlight the main views and toassess if these ideas are shared betweendifferent team members. Questionsshould focus on vital issues such assources of customer value, the currentsuccess formula and future challenges,identifying how each individual views the past, present and future aspects ofeach issue. The interview statementsshould be collated and analysed in aninterview report, structured around therecurring concepts and key themes. Thisnow sets the agenda for the firstworkshop and should be sent to allparticipants. It is also valuable toidentify the critical uncertainties andissues, as perceived by the participants,as a starting point for the workshop.D e v e l o p i n g t h e s c e n a r i o sThe workshop should identify the forcesthat will have an impact over an agreedperiod. Two possible opposite outcomesshould be agreed and the forces that could lead to each of them should be listed. This will help to show how these forces link together. Next, decide whether each of these forces have a low or high impact and a low or high probability. This information should be displayed on a 2 X 2 matrix.By having two polar outcomes and allthe driving forces clearly presented, theteam can then develop the likely‘histories’ – or scenarios – that led toeach outcome. These histories of thefuture can then be expanded throughdiscussion of the forces behind thechanges. The aim is not to develop accurate predictions, it is to understand what will shape the future and how different events interact and influence each other. All the time, discussions are focused on each scenario’s impact on the organisation.This part of the process opens up thethinking of the members in the teamand it makes them alert to signals thatmay suggest a particular direction forthe organisation. The outcomes of different responses are ‘tested’ in the safety of scenario planning, avoiding the risk of implementing a strategy for real.A n a l y s i n g t h e s c e n a r i o sThe analysis stage examines the external issues and internal logic.Consider:•What are the priorities and concerns of those outside theorganisation, who are alsoresponsible for the maindecisions in the scenario?•Who are the other stakeholders?•Who are the key players and do they change?•Would they really act and make decisions in the way described?Systems and process diagrams can help address these questions, as can discussions with other stakeholders.Remember, we are not trying to pinpoint future events but to consider the forces that may push the future along different paths.U s i n g t h e s c e n a r i o sWorking backwards from the future to the present, the team should formulate an action plan that can influence the It is impossible to manageeffectively in the short-term without forming a medium andlong-term view of the future.Doing the wrong thing, evenefficiently, gets you nowhere. There are two things we can say for certain about the future. It will be different – and it will surprise.organisation’s thinking. Next, it shouldidentify the early signs of change so thatwhen they do occur, they will berecognised and responded to quicklyand effectively. The process thencontinues by identifying gaps inorganisational knowledge. Theparticipatory and creative process sensitises managers to the outsideworld. It helps individuals and teams torecognise the uncertainties in theiroperating environments so that theycan question their everydayassumptions, adjust their mental mapsand think ‘outside the box’.A v o i d i n g P r o b l e m sPeople who work with scenarios find it to be exciting, valuable and enjoyable. It can also lead to a tangible and significant result: a shift in attitude, as well as greater certainty, confidence and understanding. However, it is necessary to keep in mind some of the problems that may arise such as: Misunderstanding what it is that the scenarios are intended to achieve. Scenarios are not predictions, they are a guide to understanding what possible futures lie ahead and what forces may be at work – now and in the future – to make these futures a reality.Failing to create or explore scenarios that are either viable or sufficiently imaginative. Too often people rely on in‐house views, traditional perceptions and internal problems – the resulting scenarios are then too narrowly focused or close to home.Failing to adopt a rigorous, intelligent and informed approach. Scenario planning begins with deep and thorough analysis and understanding of the present.Ignoring, downgrading or simply failing to act on the scenarios. Make sure that scenarios are rigorous and give them status, for example, by off‐site meetings, high‐level sponsors and management feedback. Also, use the scenarios to drive decision‐making bystimulating debate. They should be usedto develop strategy, test business orproject plans and manage risk.Failing to communicate the scenario, with the result that it does not becomeembedded within thinking or decision‐making. Instead, use imaginative and frequent communications to embedscenario thinking into discussion anddecisions.Misunderstanding the link betweenshortterm and longterm successand prosperity. If management orientsthe business towards a successfulfuture, that automatically points thecompany towards opportunities forenhanced profitability, productivity andcustomer satisfaction in the short‐term.Remember, short‐term victories won atthe expense of the future inevitably endup as defeats.K e y Q u e s t i o n s•What are the crucial questions facing the organisation, thequestions whose answers imply: Iwish I had known this five yearsago?•Do current strategic approaches typify traditional, ‘business‐as‐usual’ thinking? Are you prepared toaccept that a strategy is failing or isvulnerable?•Is the organisation in touch with market developments and the needsof customers?•Are you prepared to challenge your confidence in existing orthodoxy?•Is any part of your organisational planning weak and lacking cleardirection?•Do you lack confidence in your ability to engage in strategic debate?•In your decision‐making process do you, as a matter of routine, alwaysconsider multiple options beforedeciding? Is the quality of yourstrategic thinking limited, narrow and uninspired?•Is your organisation afraid of uncertainty, or does it enjoy thinking about it? Do people see it as a threat or as an opportunity? Is it recognised as a potential source of competitive advantage?D o s a n d D o n’t sDo:•Involve people at all levels of the organisation.•Ensure that scenarios are relevant.•Critically assess each scenario and keep the process focused, relevant and valuable.•Ensure that the process is not over‐shadowed by operational pressures, as these can limit energy and creativity.Do not:•Try to predict the future; instead, try to understand the forces that will shape it.•Allow existing biases to guide the process.•Discourage creative thinking.•Ignore or downgrade the insights, instead relate them to the organisation’s future.T h i n g s Y o u C a n D oScenarios are tools for examining possible futures. This gives them a clear advantage over techniques that may be based on a view of the past. In a rapidly changing and largely unpredictable environment, assessing possible futures is one of the best ways to promote responsiveness and directed policy. The following activities can be done with members of your team:Ask team members for their ‘histories of the future’: how things will look (say in five year’s time) andhow we reached that point. Allow oneor two days for people to developscenarios based on existing informationwithin the company. Use scenarios tostimulate debate, develop resilientstrategies and test business plansagainst possible futures.Hold workshops offsite to allowoptimum reflection and absorptiontime. For a single capital project, tryback‐of‐the‐envelope calculations tocapture the essential differences in theviability of alternatives. To assess thelikelihood of a scenario coming true, useearly indicators—events that should beseen in the next year or so. Communicate scenarios graphically,for example, by imaginary newspaperswritten as if in the future, day‐in‐the‐lifestories, film or glossy booklets. Activities that you can completeyourself to plan for the future include: 1.Regularly reading trade andbusiness publications focusing onyour industry, finance, business,politics and economics (for example,the Financial Times, The Economist,Fortune, BusinessWeek).2.Maintaining and reviewinginformation on economic, social,technological and governmental andregulatory trends.3.Delivering to your boss, peersand/or team members apresentation on the major changes(technological, socio‐economic,regulatory and commercial) likely to affect your business over the nextthree years. This could coincidewith the annual planning cycle orcontribute to a strategic plan. Thepresentation should:•Quantify the potential impact of potential changes.•Detail your actions to meet these changes.•Be prepared regularly (twice each year).Keep informed and uptodate by joining a professional membership or trade association. These are especially valuable for networking and attending seminars. Also, find a relevant website and subscribe to their email alerts.F u r t h e r A c t i o nUse the following table to identify areas for further development.Issue Response Further actionDo you think activelyabout the future? What arethe main issues,challenges, opportunitiesand priorities?Do you understand howdifferent circumstancescould affect your businessin the future?Does your organisationencourage creativity anddebate when discussing thefuture?Do you formulate scenariosformally – building modelsand assigning each adifferent probability – orinformally – using themmerely as a base to guidesensible actions?F u r t h e r I n f o r m a t i o nB o o k sScenario Planning: Managing for the Future, G. Ringland, John Wiley & Sons Ltd The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World, P. Schwartz, John Wiley & Sons LtdThe Sixth Sense: Accelerating Organisational Learning With Scenarios, K. van der Heijden, R. Bradfield, G. Burt, G. Cairns and G. Wright, John Wiley & Sons LtdO n l i n e i n f o r m a t i o n is provided by the Economist Intelligence Unit, part of The Economist Group, offering insights into business, politics, economics and technology. In particular, it also provides leading‐edge information about selected major industries. offers a wealth of links useful for business research covering news, magazines, markets and companies, banking and finance, international business, government information, reference guides, office tools, and travel. It also has an Industry Centre with news, information and links relevant to specific sectors. is provided by Michigan State University and features the Resource Desk, a collection of links to international business, finance, and trade sites on the Web, as well as articles, reports, and community facilities that include a discussion forum, chat room and e‐mail list. features Ideas@Work with content taken from the Harvard Business Review and grouped by subject, the full text of articles being available on a pay‐per‐view basis. is an excellent collection of resources provided by the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. Resources covering current business trends and ideas are arranged in 14 subject areas from finance and investment to business ethics. Brief summaries, short articles, academic papers and links to relevant websites are included.O r g a n i s a t i o n sCentre for Scenario Planning and Future Studies. The centre, based in the Graduate School of Business at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, UK, provides information, courses and advice about scenario planning.。

全文分为作者个人简介和正文两个部分:作者个人简介:Hello everyone, I am an author dedicated to creating and sharing high-quality document templates. In this era of information overload, accurate and efficient communication has become especially important. I firmly believe that good communication can build bridges between people, playing an indispensable role in academia, career, and daily life. Therefore, I decided to invest my knowledge and skills into creating valuable documents to help people find inspiration and direction when needed.正文:插上科学的翅膀飞时光穿梭机英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1Time Travel with the Wings of ScienceEver since I was a young child, I've been fascinated by the concept of time travel. The idea of journeying through the fabric of the past and future has captivated my imagination for as longas I can remember. What wonders would we discover by unlocking the secrets of the space-time continuum? Whatlong-forgotten civilizations could we explore? What terrible future catastrophes might we prevent? The possibilities seem endless and exhilarating.Of course, time travel has long been confined to the realms of science fiction, from H.G. Wells' seminal novel The Time Machine to the beloved Back to the Future film trilogy. Authors, filmmakers, and dreamers have spun incredible tales transporting us across the centuries. However, could the wings of science one day make this fantasy a reality? Might our technological progress eventually allow us to slip the bonds of the present? I certainly hope so.The core scientific concepts underlying time travel arise from Einstein's theories of relativity. The great physicist fundamentally altered our understanding of space and time, demonstrating that they are inextricably interwoven into a single continuum known as space-time. In this four-dimensional reality, time is no longer constant or absolute, but can dilate based on factors like velocity and gravity.The effects of time dilation predicted by relativity may seem minor in our daily lives on Earth, but they become extreme undermore significant gravitational forces or as objects approach the speed of light. A thought experiment can help illustrate this. Imagine twin paradox scenario where one identical twin remains on Earth while the other embarks on an interstellar voyage moving at an appreciable fraction of light speed. From the perspective of the Earth-bound twin, their sibling will have aged much more slowly due to the effects of time dilation.This bizarre consequence of relativity implies that by moving through space at sufficiently high velocities or by harnessing immense gravitational forces, we could theoretically propel ourselves forward through the river of time relative to another observer. In essence, we would be time traveling into the future, though not in the controlled manner typically depicted in science fiction tales of leaping centuries with technology like a "time machine."Still, even this limited form of time travel into the future demonstrated by Einstein's theories is a profound revelation overturning our classical notions of time as a constant, universal flow marching lockstep across the cosmos. If we can leverage these relativistic effects through future technological marvels like hyper-fast spaceships or artificially generated black holes, could we then possibly learn to navigate the timestream at will?A more daring notion inspired by quantum physics is that backward time travel might also be achievable through exploiting exotic properties of the universe like wormholes –hypothetical tunnels through space-time. While hotly debated, some interpretations of quantum theory leave open the possibility that under the correct conditions it may be possible to create traversable wormholes capable of looping back on themselves in four-dimensional space-time.If feasible engineering solutions could be found to stabilize these wormholes against collapse and usher travelers through their quantum gateways, they could provide portals into the past or future. The energy requirements predicted by calculations are absolutely staggering, however, and may forever remain science fiction. Some theorists have proposed that future civilizations perhaps trillions of years from now could possibly harness energies on that cosmic scale by exploiting exotic physical phenomena. For now, such notions can only serve as mathematical daydreams.The most speculative concepts for achieving time travel arise from fringe theories exploring the fundamental building blocks of reality. Perhaps our current models represent just the first baby steps in a grander unified theory fully describingspace-time. If discovered, such a "Theory of Everything" could potentially reveal loopholes in our present comprehension, allowing scientists to manipulate the cosmic fabric in currently unimaginable ways.While purely hypothetical at this stage, fringe thinkers have proposed such radical possibilities as using cosmic strings or constructing Traversable Acausal Retrohandled Hyperfinite (TARH) pathways looping through space-time to bypass entropy restrictions and accomplish causality violations. Without empirical evidence, however, such fanciful ideas remain the stuff of science fiction writers rather than legitimate theory. They remind us how little we may actually understand about deep aspects of reality.Despite the uncertainties of cutting-edge theorizing, history shows that making leaps into the unknown can unleash tremendous progress. The foundations of modern physics itself were seeded by a handful of wild ideas that flew in the face of prevailing scientific dogmas. Perhaps by following the wings of our curiosity to map the unexplored territory of space-time, we might eventually gain mastery over it. If so, could a fantastic age of time tourism one day open篇2Soaring on the Wings of Science Through a Time MachineEver since I was a young child, I've been fascinated by the concept of time travel. The idea of journeying through the cosmic ocean of the fourth dimension, transcending the linear constraints of chronology, has sparked an insatiable sense of wonder and curiosity within me. Time machines have long been the stuff of science fiction – the iconic DeLorean from Back to the Future, the intricate machinery of H.G. Wells' Time Machine, or the sleek, metaphysical wormholes that theoretical physicists speculate could breach the fabric of space-time itself.However, as I've delved deeper into the realms of science, particularly physics, I've come to realize that the prospect of time travel may not be as far-fetched as it seems. In fact, it might well be an inevitable consequence of our universe's fundamental laws, waiting to be unlocked by the boundless potential of human ingenuity and the relentless march of scientific progress.The theoretical underpinnings of time travel find their roots in Albert Einstein's revolutionary theory of relativity. According to this paradigm-shifting framework, time is not an absolute, universal constant, but rather a malleable dimension inextricably intertwined with space, matter, and energy. The very fabric of space-time can be warped and distorted by the presence ofmassive gravitational fields, opening up tantalizing possibilities for traversing the temporal domain.One of the most intriguing concepts arising from Einstein's theories is that of the "closed timelike curve" – a hypothetical trajectory in space-time that loops back on itself, allowing an object or traveler to theoretically return to their own past. While the precise mechanics of such a phenomenon remain shrouded in mystery, it has captured the imaginations of physicists and science fiction enthusiasts alike.Another intriguing avenue for potential time travel lies in the realm of wormholes – hypothetical tunnels or shortcuts through the cosmic fabric that could, in theory, connect two distant regions of space-time. Traversing a wormhole could potentially enable a traveler to bypass the conventional flow of time, effectively traveling into the future or even the past, depending on the wormhole's properties.Of course, the realization of time travel is fraught with mind-bending paradoxes and logical conundrums that have perplexed philosophers and scientists for decades. The infamous "grandfather paradox," for instance, poses a seemingly insurmountable logical obstacle: if you were to travel back in time and inadvertently (or perhaps intentionally) prevent yourgrandparents from meeting, you would effectively erase your own existence from the timeline – a self-contradictory scenario that challenges our very notions of causality and free will.Despite these daunting challenges, the pursuit of time travel remains an irresistible lure for the human intellect, driving us to push the boundaries of our understanding and to unravel the deepest mysteries of the cosmos. After all, if we were to achieve even the slightest degree of temporal maneuverability, the implications would be nothing short of revolutionary.Imagine being able to witness pivotal moments in human history firsthand, to walk alongside luminaries like Socrates, Leonardo da Vinci, or Marie Curie, and to gain invaluable insights into the triumphs and tribulations that have shaped our collective journey. Or consider the tantalizing prospect of peering into the future, glimpsing the technological marvels and societal transformations that await us, and using that knowledge to steer humanity towards a brighter, more sustainable path.Of course, such power would also carry immense responsibility, as the potential for abuse or unintended consequences could be catastrophic. Any successful time travel endeavor would necessitate a profound ethical framework,rigorously developed and adhered to, to ensure that the delicate tapestry of causality is not irreparably disrupted.As a student of science, I find myself both awed and humbled by the audacious quest for time travel. It represents the pinnacle of human curiosity and intellectual daring, a bold venture into realms once deemed utterly fanciful and impossible. Yet, it is precisely this unquenchable thirst for knowledge, this relentless drive to push against the boundaries of the known, that has propelled humanity's greatest achievements throughout history.From the rudimentary tools of our prehistoric ancestors to the awe-inspiring marvels of modern technology, our species has consistently defied the limitations imposed by our finite comprehension, venturing forth into uncharted territories with a spirit of fearless exploration. The pursuit of time travel is simply the latest, and perhaps the most ambitious, chapter in this grand narrative of human discovery.As I stand on the precipice of adulthood, poised to embark on my own scientific journey, I cannot help but feel a profound sense of excitement and anticipation. The challenges that lie ahead are daunting, the obstacles seemingly insurmountable,but it is in the crucible of such adversity that true innovation is forged.Perhaps, one day, I will have the privilege of contributing, even in the smallest of ways, to the realization of this age-old dream – to soar on the wings of science, transcending the shackles of linear time, and unlocking the secrets of the cosmic tapestry that binds us all. For now, I can only marvel at the audacity of such an endeavor and embrace the endless possibilities that await us at the forefront of human knowledge.Time travel may yet remain a tantalizing fantasy, a thought experiment to be pondered and debated. But in theever-expanding realm of science, where the impossible is routinely transmuted into reality, one can never discount the power of human ingenuity and the boundless potential that lies waiting to be unveiled. As I gaze skyward, I see not merely the vast expanse of the cosmos, but a canvas upon which the most extraordinary dreams of humanity may one day be etched – a tapestry woven from the threads of curiosity, perseverance, and an unwavering commitment to pushing the frontiers of knowledge ever further.And who knows? Perhaps, in some distant future, or even some long-forgotten past, a traveler from another era willstumble upon these very words, a testament to the enduring spirit of human inquiry and our eternal quest to unravel the mysteries of time itself.篇3Soaring Through Time with the Wings of ScienceEver since I was a young child, my imagination has been captivated by the concept of time travel. The idea of journeying through the cosmic ocean of the past and future has kindled an insatiable curiosity within me. However, as I matured and delved deeper into the realms of science, I realized that this fantasy might not be as implausible as it seems. With the wings of scientific advancement, we may one day conquer the barriers of time itself.The notion of time travel has long been a subject of fascination for scientists, philosophers, and storytellers alike. From H.G. Wells' seminal novel "The Time Machine" to the mind-bending scientific theories of Albert Einstein, the concept has transcended mere fiction and entered the realm of theoretical possibility. Einstein's theory of relativity introduced the groundbreaking idea that time is not an absolute constant,but rather a malleable dimension intricately intertwined with space and matter.This revolutionary understanding paved the way for further exploration into the nature of time and its potential manipulability. Physicists have proposed various hypothetical mechanisms for time travel, including wormholes, cosmic strings, and even the exploitation of the quantum realm. While these concepts may seem outlandish, they are grounded in the fundamental principles of modern physics and have sparked intense scientific debate and investigation.One particularly intriguing avenue of research is the study of wormholes – hypothetical tunnels in the fabric of spacetime that could potentially connect distant regions of the universe or even different eras. Although the existence of traversable wormholes remains purely theoretical, some scientists have proposed methods to stabilize them using exotic matter or cosmic strings. The implications of such a discovery would be nothing short of revolutionary, allowing us to transcend the linear constraints of time and explore the vast tapestry of the cosmos.Another tantalizing possibility lies in the realm of quantum mechanics, where the strange and counterintuitive behavior of subatomic particles defies our classical understanding of reality.Some theories suggest that quantum entanglement, a phenomenon where particles become inextricably linked regardless of distance, could potentially facilitate a form of time travel through the manipulation of information. While the practical applications of such concepts are still the subject of intense speculation, they open up a fascinating realm of possibilities that challenge our fundamental assumptions about the nature of time.Beyond the realm of theoretical physics, technological advancements in fields such as nanotechnology, quantum computing, and advanced propulsion systems may also play a pivotal role in our quest to conquer time. As our understanding of the universe deepens and our capabilities expand, we inch closer to the possibility of engineering solutions that could one day make time travel a tangible reality.Of course, the implications of such a monumental achievement extend far beyond mere scientific curiosity. Time travel could revolutionize our understanding of history, allowing us to witness pivotal moments firsthand and unravel the mysteries of the past. It could also provide invaluable insights into the future, enabling us to anticipate and prepare for potential challenges or disasters before they occur. Furthermore,the ability to traverse time could have profound implications for fields such as medicine, archaeology, and even space exploration, opening up new avenues of discovery and understanding.Yet, as we contemplate the exhilarating prospects of time travel, we must also confront the ethical and philosophical quandaries that accompany such a transformative technology. The potential for abuse or unintended consequences is not to be taken lightly. Would altering the past irrevocably alter the present? Could knowledge of the futureundermine the very fabric of human agency and free will? These are but a few of the complex questions that must be grappled with as we inch closer to this incredible feat.Despite these challenges, the allure of time travel remains undeniable. It represents the pinnacle of human curiosity and ambition, a testament to our relentless pursuit of knowledge and understanding. As a student of science, I am both awed and humbled by the prospect of one day soaring through the vast expanse of time, carried aloft by the wings of our collective scientific endeavors.While the path ahead is shrouded in uncertainty, one thing remains clear: the quest to unlock the secrets of time travel is a testament to the boundless potential of the human mind and ourunwavering determination to push the boundaries of what is possible. With each new discovery, with each theoretical breakthrough, we inch closer to realizing this age-old dream, and I am honored to be a part of this incredible journey.As I stand on the precipice of a future where the constraints of time may be transcended, I am filled with a profound sense of awe and anticipation. The wings of science have carried us this far, and I have no doubt that they will continue to propel us towards even greater heights of understanding and exploration. Time travel may once have been the stuff of dreams and fanciful tales, but today, it stands as a tantalizing reality, beckoning us to take flight and soar through the vast expanse of the cosmic tapestry.。

英语作文 ifHere is a 2000-word essay on the topic "If":If。

If is a small word, but it can have a profound impact on our lives. It is a word that opens up a world of possibilities, allowing us to explore the what-ifs and consider alternative paths. In this essay, we will delve into the power of "if" and examine how it shapes our thoughts, decisions, and the course of our lives.The Power of Possibility。

At its core, "if" is a word that introduces a hypothetical scenario. It allows us to step outside the confines of our current reality and imagine a different set of circumstances. This ability to envision alternative futures is a uniquely human trait, and it is one that has been instrumental in our evolution and progress as aspecies.When we say "if," we are acknowledging that there are multiple ways a situation could unfold. We are recognizing that the present is not the only possible outcome, and that the future is not set in stone. This awareness ofpossibility is a powerful tool that can inspire us to take action, to seek out new opportunities, and to challenge the status quo.The Influence of "If" on Decision-Making。

cfa二级 reading1Reading 1 - Corporate FinanceThe first reading in the CFA Level II exam, Corporate Finance, covers various topics related to financial planning and decision-making within corporations. This reading has a significant influence on the overall understanding of finance and investment management. Let us explore some of the key concepts discussed in this reading.1. The Financial Management FunctionThe reading begins by introducing the financial management function and its role in managing the firm's financial resources. It highlights the primary responsibility of financial managers, which is to maximize shareholder wealth. The reading explains how financial managers achieve this goal by making investment decisions and financing decisions.2. Investment Decision AnalysisThis section focuses on evaluating potential investment projects using various methods, such as Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Payback Period. These techniques help financial managers determine the profitability and viability of investment opportunities. The reading also emphasizes the importance of considering risk and uncertainty when making investment decisions.3. Capital Budgeting TechniquesThe reading delves into capital budgeting techniques, including the use of discounted cash flow models, such as the NPV and IRRmethods. It provides step-by-step guidelines for applying these models to determine whether an investment project should be accepted or rejected. Additionally, it discusses the importance of sensitivity analysis and scenario analysis in assessing the impact of changes in key variables on investment decisions.4. Cost of CapitalIn this section, the reading explains how to calculate the cost of capital, which represents the required rate of return for a firm's investments. It covers different sources of capital, including equity and debt, and discusses the impact of taxes on the cost of capital. The concept of the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is also introduced, highlighting its significance in determining the minimum acceptable return for investment projects.5. Capital StructureThe reading explores the concept of capital structure, which refers to the mix of debt and equity financing used by a firm. It discusses factors that influence the optimal capital structure, such as risk, taxes, and the firm's ability to generate cash flows. The Modigliani-Miller theorem is presented as a theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between capital structure and firm value.6. Dividend PolicyThis section focuses on the various factors that influence a firm's dividend policy, including legal constraints, financial flexibility, and shareholder preferences. The reading explores different dividend distribution methods, such as cash dividends and stock dividends, and their impact on the firm's value. It also discussesshare repurchases and their implications for shareholders.7. Corporate GovernanceThe reading concludes by discussing the importance of corporate governance in ensuring efficient and effective decision-making within a firm. It explores the roles and responsibilities of the board of directors, shareholders, and management in corporate governance. The reading also covers the relevance of ethical considerations and social responsible behaviors in corporate finance decisions.In conclusion, the first reading in the CFA Level II exam, Corporate Finance, covers essential topics related to financial planning and decision-making within corporations. It provides a comprehensive understanding of investment decision analysis, capital budgeting techniques, cost of capital, capital structure, dividend policy, and corporate governance. Applying the knowledge gained from this reading is crucial for any finance professional aiming to make informed financial decisions.。

The Academic Word ListSublist 1 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesThis sublist contains the most frequent words of the Academic Word List in the Academic Corpus. The most frequent members of the word families in Sublist 1 are listed below.analysis分析approach方法area地区领域assessment 评价assume假设authority权威available可提供的benefit好处,受益concept概念consistent一致的constitutional宪法的context 环境contract收缩合同create 创造data 数据definition 定义derived由来,派生distribution 分布economic 经济的environment 环境establish 建立estimate 估计evidence 证据export出口factors 因素financial 金融的formula公式function 功能identified确认的income 收入indicate 指出individual 个人的interpretation理解involved 涉及到issues 问题labour 劳动力legal 合法的legislation 立法major 主要的专业method 方法occur 出现percent 百分之period 时期policy 政策principle 原则procedure 步骤process 过程,处理required 必须的research 研究response 回应role 角色,作用section 部分sector 行业区域significant 重要的similar 相似的source 源头specific 具体的structure 结构theory 理论variables 变量Sublist 2 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesThis sublist contains the second most frequent words in the Academic Word List from the Academic Corpus. The most frequent members of the word families in Sublist 2 are listed below.achieve获得acquisition收购获得administration管理affect影响appropriate合适的aspects 方面assistance 协助categories 种类chapter 章节commission委托community社区complex组成的,合成的computer电脑conclusion结论conduct做consequences 后果construction 建设consumer 顾客credit 信用cultural 文化的design 设计distinction 区别elements 元素equation等式evaluation 评价features 特点final 最后的focus 关注impact 影响injury 受伤institute 协会investment 投资items 项目条款journal期刊maintenance 维修normal 正常的obtained 获得participation 参与perceive 认识到positive 积极的potential 潜在的previous 之前的primary 主要的purchase 购买range 范围region 地区regulations 规则relevant 相关的resident 定居者resources 资源restricted 受限security 安全sought 寻找(过去式)select 挑选site 选址strategies 策略survey 调查text 文本1traditional 传统的transfer 转移Sublist 3 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesThis sublist contains the third most frequent words of the Academic Word List in the Academic Corpus. The most frequent members of the word families in Sublist 3 are listed below.alternative 可供选择的circumstance 环境comments评论compensatio n 补偿components 组成部分consent同意considerable 大量的constant连续的constraints 限制contribution 贡献convention 准则coordination 协调core 核心的corporate大公司corresponding相应的criteria 标准deduction减除demonstrate证明document文件dominant 主导的emphasis重要性ensure确保excluded排除framework框架funds资金illustrated给…插图immigration移民implies 暗示initial 开始的instance例子interaction互动justification证明正确layer层link连接location地点maximum 最大minorities 少数negative 消极的outcomes 结果partnership合作philosophy 哲学physical 身体的proportion部分比例publish出版reaction 反应registered 登记reliance 依靠removed 移开scheme 计划方案sequence顺序sex 性shift 转换specified具体说明的sufficient足够的task 任务technical 技术的techniques 技术technology 技术validity合法性volume量Sublist 4 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesThis sublist contains the fourth most frequent words of the Academic Word List in the Academic Corpus. The most frequent members of the word families in Sublist 4 are listed below.access获得adequate足够的annual年度的apparent明显的approximate近似attitudes 态度attributed 归因于civil国内的code代码commitment承诺communication交流concentration浓度conference会议contrast 对比cycle 循环debate 辩论despite尽管dimensions维度domestic 国内的emerge 出现error 错误ethnic 民族的goals 目标granted 授予hence 因此hypothesis 假说implementation 实施implications 含意暗示imposed 强加integration 结合internal 内部多investigation 调查job 工作2label 标签mechanism机制obvious 明显的occupational 职业的option选择output 产出overall 整体的parallel 平行parameters参数phase阶段predicted预测principal 主要的prior 先前的professional 专业的project项目promote促进regime政权resolution决心retained保留series 系列statistics统计status 地位stress 压力subsequent 紧随其后的sum 总量summary 总结undertaken 承担Sublist 5 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesacademic学术的adjustment调整alter 改变amendment修订aware 注意到capacity 能力challenge挑战clause从句compounds混合物conflict 矛盾consultation 咨询contact接触decline 下降discretion谨慎draft 草稿enable 使…能energy能量enforcement 强制执行entities 实物equivalent相等的evolution 进化expansion扩张exposure 接触external 外部的facilitate协助fundamental 根本的generated产生generation 代image图像liberal 开明的licence 执照logic 逻辑marginal 边缘的medical 医学的mental 精神的modified 修改monitoring 监督network 网络notion 概念objective 客观的orientation定位perspective角度precise 精准的prime 主要的psychology 心理学pursue追逐ratio 比例rejected 拒绝revenue 税收stability稳定性styles 风格substitution 代替物sustainable 可持续的symbolic 象征的target 目标transition过度trend 潮流version 版本welfare 福祉whereas却Sublist 6 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesabstract摘要accurate 准确的acknowledge承认aggregate 总计allocation分配assigned指派attached粘附author作者bond纽带brief简洁的capable有能力的cite引用cooperative合作的discrimination歧视display显示diversity多样性domain 领域edition版本enhanced提高estate地产exceed超过expert专家explicit明显的federal联邦的fees费用flexibility 灵活性furthermore而且gender 性别ignored忽视incentive 刺激incidence 发生incorporate纳入index 索引inhibition内抑感initiatives 主动性input输入instructions指示intelligence 智力interval间隔lecture 讲座migration 迁徙minimum 最小ministry 部motivation动机neutral 中立的nevertheless然而overseas 海外的precede先于presumption推测rational合理的recovery恢复revealed揭示scope范围subsidiary次要的tapes 带子trace追踪transformation蜕变transport交通underlying潜在的utility实用效用3Sublist 7 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesadaptation适应adults成年人advocate支持aid 帮助channel渠道chemical 化学的classical经典的comprehensive全面的comprise由…组成confirmed确定contrary 相反的converted 转换couple 一对decade 十年definite明确的deny否认differentiation区分disposal丢弃dynamic动态的eliminate消除empirical经验主义的equipment设备extract 提取file 文件finite有限的foundation 基础global 全球的grade成绩guarantee保证hierarchical分等级的identical相似的ideology意识形态inferred推断innovation创新insert 嵌入intervention 干预isolate使孤立media媒体mode模式paradigm范例phenomenon 现象priority 优先权prohibited禁止publication 出版物quotation 引用release释放reverse倒退simulation 模仿solely独自的somewhat稍微submit提交successive连续的survive幸存thesis论文topic主题transmission传播ultimately最终地unique独特的visible可见的voluntary自愿的Sublist 8 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesabandon放弃accompanied陪伴accumulation积累ambiguous模糊的appendix附录appreciation感激arbitrary武断的automatically自动的bias偏见chart图表clarity清楚conformity遵守commodity商品complement补充contemporary现代的contradiction矛盾crucial 重要的currency货币denote 指示detected察觉deviation偏离displacement位移dramatic戏剧的eventually最后的exhibit展示exploitation充分利用fluctuations波动guidelines指导highlighted强调implicit含蓄的induced引诱inevitably不可避免的infrastructure基础设施inspection检查intensity强度manipulation操控minimised最小化nuclear核offset抵消paragraph段落plus 加practitioners 从业者predominantly主导的prospect前景radical根本的random随意的reinforced加强restore储存revision修订schedule行程表tension紧张termination终结theme主题thereby因此uniform不变的vehicle工具轿车via通过virtually几乎widespread普遍的visual视觉的Sublist 9 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesaccommodation住宿analogous类比的anticipated预料assurance确保attained获得behalf为了...的利益bulk 体积ceases停止coherence协调的coincide同时发生commenced开始4incompatible不兼容的concurrent同时发生的confined限制controversy争执conversely相反的device装置devoted投入diminished减少distorted/distortion 扭曲duration 持续erosion腐蚀ethical道德的format布局founded建立inherent内在的insights洞察力integral必需的intermediate中间的manual用手的mature成熟的mediation调停medium媒介military军事的minimal最小的mutual双方的norms惯例overlap重合passive消极的portion比例preliminary基础的protocol惯例qualitative质的refine提炼relaxed放松的restraints 限制revolution革命rigid严格的route线路scenario梗概sphere球面领域subordinate下级的supplementary补充道suspended暂停team团队temporary暂时的trigger 引起unified 统一的violation违背vision视力Sublist 10 of the Academic Word List - Most frequent words in familiesThis sublist contains the least frequent words of the Academic Word List in the Academic Corpus. The most frequent members of the word families in Sublist 10 are listed below.adjacent 比邻的albeit尽管assembly聚集到一起的人collapse倒塌colleagues同事compiled汇编conceived构思convinced使信服depression 萧条降低encountered 面临enormous 巨大的forthcoming 即将到来的inclination倾向integrity完整,诚实intrinsic内在的invoked引起产生levy 征收likewise同样nonetheless 尽管如此notwithstanding尽管odd 古怪的ongoing持续的panel 委员会,小组persistent 坚持不懈的posed形成构成reluctant不情愿的so-called所谓的straightforward 易懂的undergo经受whereby 借56。

Worst-case robust decisions for multi-periodmean–variance portfolio optimizationNalan Gu ¨lpınara,*,Berc ¸Rustem b aThe University of Warwick,Warwick Business School,Coventry CV47AL,UK b Imperial College London,Department of Computing,180Queen’s Gate,London SW72AZ,UKReceived 15October 2004;accepted 15February 2006Available online 13June 2006AbstractIn this paper,we extend the multi-period mean–variance optimization framework to worst-case design with multiple rival return and risk scenarios.Our approach involves a min–max algorithm and a multi-period mean–variance optimiza-tion framework for the stochastic aspects of the scenario tree.Multi-period portfolio optimization entails the construction of a scenario tree representing a discretised estimate of uncertainties and associated probabilities in future stages.The expected value of the portfolio return is maximized simultaneously with the minimization of its variance.There are two sources of further uncertainty that might require a strengthening of the robustness of the decision.The first is that some rival uncertainty scenarios may be too critical to consider in terms of probabilities.The second is that the return variance estimate is usually inaccurate and there are different rival estimates,or scenarios.In either case,the best decision has the additional property that,in terms of risk and return,performance is guaranteed in view of all the rival scenarios.The ex-ante performance of min–max models is tested using historical data and backtesting results are presented.Ó2006Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.Keywords:Stochastic programming;Nonlinear programming;Risk management;Finance;Worst-case design;Uncertainty modelling;Scenario tree1.IntroductionIn financial portfolio management,the maximization of return for a level of risk is the accepted approach to decision making.A classical example is the single-period mean–variance optimization model in which expected portfolio return is maximized and risk measured by the variance of portfolio return is minimized (Markowitz,1952).Consider n risky assets with random rates of return r 1,r 2,...,r n .Their expected values are denoted byE (r i )or ri ,for i =1,...,n .The single period model of Markowitz considers a portfolio of n assets defined in terms of a set of weights w i for i =1,...,n ,which sum to unity.Given an expected rate of portfolio return r p ,the optimal portfolio is defined in terms of the solution of the following quadratic programming problem:0377-2217/$-see front matter Ó2006Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2006.02.046*Corresponding author.E-mail addresses:Nalan.Gulpinar@ (N.Gu ¨lpınar),br@ (B.Rustem).European Journal of Operational Research 183(2007)981–1000982N.G€u lpınar,B.Rustem/European Journal of Operational Research183(2007)981–1000fh w;K w ij w0 r P r p;10w¼1;w P0g;minwwhere K is the covariance matrix of asset returns.The quadratic program yields the minimum variance port-folio.Note that the classical stochastic linear programming formulation maximizes the expected return but takes no account of risk.A multi-period framework to reformulate the single stage asset allocation problem as an adaptive multi-period decision process has been developed by using multi-period stochastic programming,see for example Birge and Louveaux(1997),Kall(1976),Kall and Wallace(1994)and Prekopa(1995).In the multi-stage case, the investor decides based on expectations and/or scenarios up to some intermediate times prior to the hori-zon.These intermediate times correspond to rebalancing or restructuring periods.The mean or the variance of total wealth at the end of the investment horizon is modelled by either linear stochastic programming or quadratic stochastic programming in Gu¨lpınar et al.(2002,2003).Multi-period portfolio optimization entails the construction of a scenario tree representing a discretised estimate of uncertainties and associated probabilities in future stages.The multi-period stochastic mean–variance approach takes account of the approximate nature of the discrete set of scenarios by considering a variance term around the return scenarios.Hence,uncertainty on return values of instruments is represented by a discrete approximation of a multivariate continuous distribution as well as the variability due to the dis-crete approximation.The mean–variance framework is based on a single forecast of return and risk.In reality, however,it is often difficult or impossible to rely on a single forecast;there are different rival risk and return estimates,or scenarios.Two sources of further uncertainty might require a strengthening of the robustness of the mean–variance decision.Thefirst is that some rival uncertainty scenarios may be too critical to consider in terms of probabilities.A worst-case optimal strategy would yield the best decision determined simultaneously with the worst-case scenario.The second is that the return variance estimate is usually inaccurate and there are different rival estimates,or scenarios.A worst-case optimal strategy protects against risk of adopting the investment strategy based on the wrong scenario.In either case,the best decision has the additional property that,in terms of risk and return,performance is guaranteed in view of all the rival risk and return scenarios. The min–max optimal performance will improve for any scenario other than the worst-case.This guaranteed performance and noninferiority property of min–max are discussed further in Section3.In this paper,multi-period mean–variance optimization framework is extended to the robust worst-case design problem with multiple return and risk scenarios.Our approach involves a min–max algorithm and a multi-period mean–variance optimization framework for the stochastic aspects of the scenario tree,(Gu¨lpınar and Rustem,2004).Since optimal investment decision is based on the min–max strategy,the robustness is ensured by the non-inferiority of min–max.The optimal portfolio is constructed(relative to benchmark) simultaneously with the worst-case to take account of all rival scenarios.The portfolio is balanced at each time period incorporating scalable(notfixed)transaction cost and its relative performance is measured in terms of returns and the volatility of returns.The rest of the paper is organized as follows.In Section2,the multi-period mean variance optimization problem is described.In Section3,we introduce multi-period discrete min–max formulations of multi-period mean–variance optimization problem for robust,optimal investment strategies in view of rival return and risk scenarios(which are input scenarios in the min–max formulation).Section4focuses on the generation of sce-nario tree and forecasting rival risk and return scenarios.In Section5,we present our computational results which are based on worst-case risk-return frontiers and backtesting(out-of-sample).2.Problem statementThe central problem considered in this paper is to determine multi-period discrete-time optimal portfolio strategies over a givenfinite investment horizon.Therefore,we start with the definition of returns and uncertain-ties.Subsequently,we present the model constraints,the expected return and risk formulations based on the sce-nario tree.For the more details of multi-period mean–variance optimization framework,the reader is referred to Gu¨lpınar et al.(2003).We consider n risky assets and construct a portfolio over an investment horizon T.After the initial invest-ment(t=0),the portfolio may be restructured at discrete times t=1,...,TÀ1in terms of both return andrisk,and redeemed at the end of the period (t =T ).A description of our notation is given in Table 1.All quan-tities in boldface represent vectors in R n .The transpose of a vector or matrix will be denoted with the symbol 0.2.1.Scenario treeLet q t {q 1,...,q t }be stochastic events at t =1,...,T .The decision process is non-anticipative (i.e.deci-sion at a given stage does not depend on the future realization of the random events).The decision at t is dependent on q t À1.Thus,constraints on a decision at each stage involve past observations and decisions.A scenario is defined as a possible realization of the stochastic variables {q 1,...,q T }.Hence,the set of scenarios corresponds to the set of leaves of the scenario tree,N T ,and nodes of the tree at level t P 1(the set N t )cor-respond to possible realizations of q t .We denote a node of the tree (or event)by e =(s ,t ),where s is a scenario (path from root to leaf),and time period t specifies a particular node on that path.The root of the tree is 0=(s ,0)(where s can be any scenario,since the root node is common to all scenarios).The ancestor (parent)of event e =(s ,t )is denoted a (e )=(s ,t À1),and the branching probability p e is the conditional probability of event e ,given its parent event a (e ).The path to event e is a partial scenario with probability P e ¼Q p e along Table 1NotationInput parametersn Number of investment assetsT Planning horizonh Current portfolio position (i.e.at t =0,before optimization)w ÃMarket benchmarkc b Vector of unit transaction costs for buyingc s Vector of unit transaction costs for sellinga tWeight for each time period c Scaling constant determining the level of risk aversionk Penalty parameterK i 2R n Ân Covariance matrices for i =1,...,I e (or I t and I k )W t Expected total wealth at time t =1,...,T Scenario treeq t Vector of stochastic data observed at time t ,t =0,...,Tqt {q 0,...,q t }—history of stochastic data up to t N Set of all nodes in the scenario treeN t Set of nodes of the scenario tree representing possible events at time tN IN ÀðN 0[N T Þ,i.e.set of all interior nodes of the scenario tree s Index denoting a scenario,i.e.path from root to leaf in the scenario treee (s ,t )Index denoting an event (node of the scenario tree),which can be identified by an ordered pair of scenario and time period a (e )Ancestor of event e 2N (parent in the scenario tree)p e Branching probability of event e :p e =Prob[e j a (e )]P e Probability of event e :if e =(s ,t ),then P e ¼Q i ¼1...t p ðs ;i Þr t (q t )Stochastic vector of return values for the n assets,t =1,...,Tr e Stochastic realization of r t in event e :r e $N (r t (q t ),K )^r eE (r e (q t j q t À1))—expectation of r t (q t )for event e ,conditional on q t À1Decision variablesw *Decision vector indicating asset balancesb *Decision vector of ‘‘buy’’transaction volumes s *Decision vector of ‘‘sell’’transaction volumesm *Worst-case riskl Worst-case return*Vectors w , w ,b ,and s can be indexed either with t =1,...,T (in which case they represent stochastic quantities with an implied dependence on q t ),or e 2N (in which case they represent specific realizations of those quantities).Variable m is indexed with e ,t ,and k (rival return scenarios)E [Æ]Expectation with respect to q1 (1,1,1,...,1)0u v (u 1v 1,u 2v 2,...,u n v n )0N.G €ulpınar,B.Rustem /European Journal of Operational Research 183(2007)981–1000983that path;since probabilities p e must sum to one at each individual branching,probabilities P e will sum up to one across each layer of tree-nodes N t ;t ¼0;1;...;T .Each node at a level t corresponds to a decision {w t ,b t ,s t }which must be determined at time t ,and depends in general on q t ,the initial wealth w 0and past decisions {w j ,b j ,s j },j =1,...,t À1.This process is adapted to q t as w t ,b t ,s t cannot depend on future events q t +1,...,q T which are not yet realized.Hence w t =w t (q t ),b t =b t (q t ),and s t =s t (q t ).However,for simplicity,we shall use the terms w t ,b t and s t ,and assume their impli-cit dependence on q t .Notice that q t can take only finitely many values.Thus,the factors driving the risky events are approximated by a discrete set of scenarios or sequence of events.Given the event history up to a time t ,q t ,the uncertainty in the next period is characterized by finitely many possible outcomes for the next observation q t +1.This branching process is represented using a scenario tree.An example of scenario tree with three time periods and 2-2-3branching structure is presented in Fig.1.We also model a continuous pertur-bation in addition to the discretised uncertainty;see also Frauendorfer (1995),so that the vector of return val-ues at time t has a multivariate normal distribution,with mean r t (q t ),and specified covariance matrix K .2.2.Mean–variance optimizationThe single period mean–variance optimization problem can be extended to multi-stage programming.In this case,referring to Fig.2,after the initial investment we can rebalance our portfolio (subject to any desired bounds)to maximize profit at the investment horizon and minimize the risk at discrete time periods and redeem at the end of the period.An initial benchmark portfolio is specified as w0(possibly =h ),and benchmarks at later time periods derive from w0by accruing returns,but not allowing any reallocation: w t ðq t Þ¼r t ðq t Þ w t À1ðq t À1Þ;t ¼1;...;T :Henceforth, wt will be referred to without its implicit dependence on q t.Fig.2.Mean–variance optimization on a scenario tree.984N.G €ulpınar,B.Rustem /European Journal of Operational Research 183(2007)981–1000At t=0,the initial budget is normalized to1.If the investor currently has holdings of assets1,...,n,then vector h(scaled so that10h=1)represents his current position.If the investor currently has no holdings(wish-ing to buy in at time t=0),then h=0.The allocation of the initial budget of1can be represented with the following constraints:hþð1Àc bÞb0Àð1þc sÞs0¼w0;ð1Þ10b0À10s0¼1À10h:ð2ÞConstraint(2)enforces the initial budget of unity(whether it is new investment or re-allocation).The net total amount of buying makes up the shortfall of the original portfolio beneath the budget.It is important to note that our model allows money to be added to the portfolio in this way only in the initial time period.The decision at time t>0is clearly dependent on q t and w t(q t)depends on the past and not the future. Therefore,the policy{w0,...,w t}is called non-anticipative.Furthermore,q0is observed before the initial decision and is thus treated as deterministic information.The dynamic structure of the model is captured by investment strategy which are defined by asset weights at each interior node of the scenario tree as follows:r e w aðeÞþð1Àc bÞ b eÀð1þc sÞ s e¼w e;e2N I:ð3ÞWe require subsequent transactions(buy=b t,sell=s t)not to alter the wealth within the period t.Buy and sell decisions are made in view of(3)and subject to Eqs.(6)–(8).Hence,we have the condition 10b eÀ10s e¼0;e2N I:ð4ÞSince transactions of buying and selling at the last time period are not allowed,asset weights at t=T are com-puted asr e w aðeÞ¼w e;e2N T:ð5ÞIn the mean–variance optimization framework,bounds on decision variables prevent the short sale and en-force further restrictions imposed by the investor.Box constraints are defined on w e,b e,s e for each event e2N I asw L e 6we6w Ue;ð6Þ06b e6b Ue;ð7Þ06s e6s Ue:ð8ÞThe objective of an investor is to minimize portfolio risk while maximizing expected portfolio return on invest-ment,or achieving a prescribed expected return.Given the possible events e2N t(the discretisation of q t),the expected wealth at time t,relative to benchmark w t,is given byW t¼E½10ðw tÀ w tÞ ¼E½r tðq t j q tÀ1Þ0ðw tÀ1À w tÀ1Þ¼EXe2N t P eðr0eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞÞ"#¼Xe2N t P eð^r0eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞÞ;ð9Þwhere^r e and w e(e2N t)are the various realizations of stochastic quantities r t(q t j q tÀ1)and w tÀ1(q tÀ1).Risk,for any realization of q t,is measured as the variance of the portfolio return relative to the benchmark w.Once W t is known,the variance of the wealth at time t(relative to the benchmark)can be similarly calculated:Var½r tðq t j q tÀ1Þ0ðw tÀ1À w tÀ1Þ¼E½ðr tðq t j q tÀ1Þ0ðw tÀ1À w tÀ1ÞÞ2 ÀðW tÞ2N.G€u lpınar,B.Rustem/European Journal of Operational Research183(2007)981–1000985¼EXe2N t P eðr0eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞÞ2"#ÀðW tÞ2¼Xe2N t P eððw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0ðKþ^r e^r0eÞðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞÞÀðW tÞ2:ð10ÞThe multi-period portfolio reallocation problem can be expressed as the minimization of risk subject to linear constraints(1)–(8)(which describe the growth of the portfolio along all the various scenarios,bounds on the variables)and the performance constraint.min w;b;s X Tt¼1a tXe2N tP e½ðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0ðKþ^r e^r0eÞðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞsubject to Constraintsð1Þ–ð8Þ;X e2N t P eð^r0eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞÞP W:The performance constraint describes thefinal expected wealth to a particular constant parameter W.The optimization model abovefinds the lowest-variance(least risky)investment strategy to achieve that specified expected wealth,W.The W range varies from the solution of linear programming problem(provides the total risk-seeking investment strategy)max w;b;s Xe2N tP eð^r0eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞÞsubject to Constraintsð1Þ–ð8Þto the value of W corresponding to the solution of quadratic programming problemmin w;b;s X Tt¼1a tXe2N tP e½ðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0ðKþ^r e^r0eÞðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞsubject to Constraintsð1Þ–ð8Þ;which provides total risk-aversion investment strategy.Varying W between the risk-seeking and the risk-averse investment strategies and reoptimizing generate optimal portfolios on the risk-return efficient frontier.3.Min–max optimizationIn the presence of the uncertainty,a robust approach is to compute expectations using the worst-case prob-ability distribution.Aoki(1967)provides a detailed discussion of this approach within the context of general dynamical systems.In this paper,the mean value of the portfolio is described in terms of rival return scenarios, or rival scenario trees,which represent rival views of the future.We assume that all rival scenarios are reason-ably likely and that it is not possible to rule out any of these using statistical analysis.Wise decision making would therefore entail the incorporation of all scenarios to provide an integrated and consistent framework. We propose worst-case robust optimal strategies which yield guaranteed performance.In risk management terms,such robust strategy would ensure that performance is optimal in the worst-case and this will further improve if the worst-case scenarios do not materialize.We note that there may well be more than one scenario corresponding to the worst-case.This noninferiority is the guaranteed performance character of min–max.To illustrate this,consider the problemmin w maxi2If f iðwÞg;where I is the(discrete)index of rival scenarios and f i be a general objective function corresponding to the i th scenario.Let w*be the solution of this problem.Then,by optimality,we have the inequality986N.G€u lpınar,B.Rustem/European Journal of Operational Research183(2007)981–1000min w maxi2If f iðwÞg¼maxi2If f iðwÃÞgP f iðwÃÞ8i2I:Hence,if the worst-case does not materialize,then performance is guaranteed to improve.The mean–variance portfolio allocation problem presented in Section2considers a scenario tree for the stochastic structure of uncertainty and a covariance matrix as an input.It is well known that asset return forecasts and risk estimates are inherently inaccurate.The inaccuracy in forecasting and estimation can be addressed through the specification of rival scenarios.These are used with forecast pooling by stochastic programming;e.g.see Kall(1976),Lawrence et al.(1986)and Makridakis and Winkler(1983).Robust pooling using min–max has been introduced in Rustem et al.(2000)and Rustem and Howe(2002).A min–max algorithm for stochastic programs based on a bundle method is discussed in Breton and El Hachem(1995).Min–max optimization is more robust to the realization of worst-case scenarios than con-sidering a single scenario or an arbitrary pooling of scenarios.It is suitable for situations which need pro-tection against risk of adopting the investment strategy based on the wrong scenario since The min–max mean–variance optimization model constructs an optimal portfolio simultaneously with the worst-case scenario.In this section,we present multi-period min–max mean–variance optimization models with multiple rival risk and return scenarios.Three alternative min–max formulations of the multi-period mean–variance optimi-zation are introduced.The difference between these formulations is characterized by the way the rival risk sce-narios are integrated.An investor might wish to consider the same rival risk scenarios at different stages such as at each node of scenario tree,any/all intermediate time periods of the investment horizon,or with each rival return scenarios.Rival return scenarios are determined by sub-scenario trees rooted at thefirst time period of the scenario tree since the investor wishes to survive at thefirst time period.For example,the scenario tree in Fig.3consists of three rival return scenarios defined by number of events realized at thefirst time period. There are different forecasting methods for rival risk and return scenarios which are discussed in detail in Section4.3.1.Model1:Risk scenarios at each nodeAssume that the risk scenarios are considered at each event of the future realizations.Let I be the num-ber of covariance matrices defining rival risk scenarios and K denote the number of rival returnscenarios.Fig.3.Worst-case scenario tree for Model1.N.G€u lpınar,B.Rustem/European Journal of Operational Research183(2007)981–1000987At each node of the scenario tree,e2N t for t=1,...,T,we have the same number of covariance matrices, denoted by I e.The selection of covariance matrices is the user dependent and an input to the min–max model.Given the rival risk and return scenarios(or scenario tree),the general min–max formulation for multi-period portfolio management problem is as follows;min w;b;scX Tt¼1a tXe2N tmaxi½P eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0ðK iþr0er eÞðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ ()þminw;b;sÀminkXe2N kTP eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0r e24358<:9=; minw;b;scX Tt¼1a tXe2N tmaxi½J ieðwÞ Àmink½R kðwÞ();whereJ i e ðwÞ¼P eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0ðK iþr0er eÞðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ;R kðwÞ¼Xe2N kTP eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0r efor i2I e,k=1,...,K,t=1,...,T and e2N t.Let m e and l be the worst-case risk at node e2N t and the worst-case return,respectively.In order to solve the min–max problem above,we reformulate it as a quadrat-ically constraint mathematical program asmin w;b;s cX Tt¼1a tXe2N tm eÀlsubject to Constraintsð1Þ–ð8Þ;Xe2N kTP eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0r e P l;k¼1;...;K;ð11ÞP eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0ðK iþr0er eÞðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ6m e;i2I e;e2N t;t¼1;...;T:ð12ÞThe level of risk aversion optimized for is determined by the scaling constant c.When c=0,the pure risk-seeking investment strategy(at the highest end of the efficient frontier)is obtained by solving a linear program-ming problem(by ignoring the constraint(12)).When c=1,completely risk-averse strategy(at the lowest end of the efficient frontier)is obtained by solving the quadratic programming problem(by ignoring the con-straint(11)).The worst-case risk m e for each event e2N t is calculated as the maximum risk value,which is computed by implementing the min–max strategy on specific rival risk scenarios and selecting maximum one among K i, i2I e.The worst-case return l is obtained as the minimum expected return at the last time periods amongW1T ;...;W KTcorresponding to each sub-scenario tree(see Fig.3).Notice that the number of quadratic con-straints,P Tt¼1Pe2N tI e,depends on the number of rival risk scenarios considered and the topology of the sce-nario tree.However,the number of risk variables only depends on the structure of the scenario tree since we have one variable m e associated with node e on the scenario tree.3.2.Model2:Risk scenarios at each time periodOne may consider the same number of risk scenarios at each time period of investment horizon.In this case, the general min–max formulation of the multi-period mean–variance optimization problem becomesmin w;b;scX Tt¼1a t maxiXe2N tP eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0ðK iþr0er eÞðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ"# ()þminw;b;smaxkÀXe2N kTP eðw aðeÞÀ w aðeÞÞ0r e24358<:9=; minw;b;scX Tt¼1a t maxi½J itðwÞ Àmink½R kðwÞ();988N.G€u lpınar,B.Rustem/European Journal of Operational Research183(2007)981–1000whereJ it ðw Þ¼X e 2N t P e ðw a ðe ÞÀ w a ðe ÞÞ0ðK i þr 0e r e Þðw a ðe ÞÀ w a ðe ÞÞR k ðw Þ¼Xe 2N k TP e ðw a ðe ÞÀ w a ðe ÞÞ0r e for i 2I t ,k =1,...,K ,t =1,...,T .As can be seen from the scenario tree presented in Fig.4,in Model 2,we have the worst-case risk m t at each time period t =1,...,T .The overall worst case risk is computed as the sum of all worst-case risks determined at t .An equivalent quadratic programming formulation of min–max prob-lem for Model 2is as follows:min w ;b ;s c X T t ¼1a t m t Àlsubject to Constraints ð1Þ–ð8Þ;X e 2N k T P e ðw a ðe ÞÀ wa ðe ÞÞ0r e P l ;k ¼1;...;K ;X e 2N tP e ðw a ðe ÞÀ w a ðe ÞÞ0ðK i þr 0e r e Þðw a ðe ÞÀ w a ðe ÞÞ6m t ;i 2I t ;t ¼1;...;T :Notice that the difference between Model 1and Model 2is characterized by the quadratic constraints.In Mod-el 2,the number of quadratic constraints P Tt ¼1I t depends on the number of rival risk scenarios specified at timeperiod t and length of the investment horizon.The number of risk variables is determined as T since there is one risk variable m t associated with time period t =1,...,T .The optimization problem in Model 2becomes more dense than the one in Model 1,since in Model 2the quadratic constraint at t consists of sum of all worst-case risk terms at node e 2N t at period t .3.3.Model 3:Risk scenarios for each rival return scenarioWe also consider the same number of rival risk scenarios associated with each rival return scenarios,which are defined by the sub-scenario trees rooted at nodes of the first time period.Let K be the number of rival return scenarios and I j be the number of rival risk scenarios associated with each sub-tree j =1,...,K .Refer-ring to Fig.5,we have three (rival return scenarios)sub-scenario trees rooted at a node in the first time period,consequently,three variables represent the worst-case risk corresponding to eachsub-tree.Fig.4.Worst-case scenario tree for Model 2.N.G €u lpınar,B.Rustem /European Journal of Operational Research 183(2007)981–1000989。