克伦生葡萄分级标准

- 格式:doc

- 大小:46.00 KB

- 文档页数:4

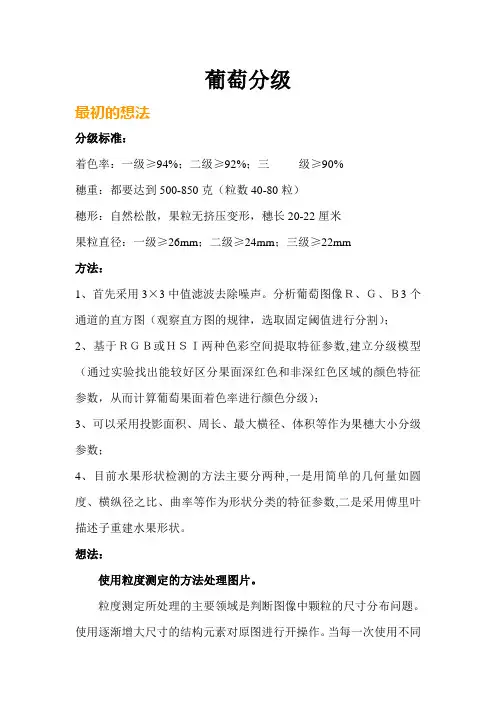

葡萄分级标准代号全文共四篇示例,供读者参考第一篇示例:葡萄分级标准代号是指根据葡萄的品质等级,制定的一套代号系统。

葡萄的品质等级通常通过颜色、味道、成熟度等多个指标来进行评价。

葡萄分级标准代号可以帮助消费者更好地了解葡萄的品质等级,从而在购买时更加明智地做出选择。

葡萄分级标准代号通常是由专业机构或协会制定的,不同的地区和国家可能会有不同的标准代号。

例如在法国,葡萄的分级标准代号通常被称为AOC(Appellation d'origine contrôlée)或IGP (Indication Géographique Protégée),在意大利则常用DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata)或DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita)。

这些代号通常会在葡萄酒的标签上标注,以帮助消费者识别葡萄的品质等级。

葡萄的分级标准代号通常是根据该葡萄产地的特定条件和传统技术来制定的。

例如在法国的AOC系统中,葡萄酒的等级通常会根据产地的土壤、气候、葡萄品种等因素来确定。

而在意大利的DOC系统中,葡萄酒的等级则受到更多地方传统和生产规定的影响。

葡萄的分级标准代号也是保护产地葡萄在市场上的地位和声誉的重要手段。

通过建立一套权威的分级标准代号,消费者可以更加信任产地的葡萄,从而提高葡萄生产者的市场竞争力。

葡萄分级标准代号是一个对葡萄产地和消费者来说都非常重要的系统。

它可以帮助消费者更好地选择适合自己口味的葡萄酒,同时也可以保护产地葡萄的声誉和市场地位。

我们应该更加关注葡萄的分级标准代号,并在购买时加以参考,以获得更好的品尝体验。

第二篇示例:葡萄分级标准代号是葡萄种植管理中一种重要的分类系统,它用来对葡萄的品质等级进行归类和评定。

通过这种标准,种植者和消费者可以更加清晰地了解葡萄的品质和特点,有助于种植者更好地管理葡萄园,提高葡萄的生产质量和市场竞争力。

Characterization and multivariate classification of grapes and wines of two Cabernet Sauvignon clonesCaracterização e classificação multivariada de uva e vinho de dois clones de Cabernet SauvignonVívian Maria Burin I; Aparecido Lima da Silva II; Luciane Isabel Malinovski II; Jean Pierre Rosier III; Leila Denise Falcão IV; Marilde Teresinha Bordignon-Luiz II Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos, Rodovia Admar Gonzaga, nº 1.346, CEP 88034-001 Florianópolis, SC, Brazil.E-mail: viburin@, bordign@cca.ufsc.brII UFSC, Departamento de Fitotecnia.E-mail: alsilva@cca.ufsc.br, lucianeisabel@.brIII Empresa de Pesquisa Agropecuária e Extensão Rural de Santa Catarina, Estação Experimental de Videira, Caixa Postal 21, CEP 89560-000 Videira, SC, Brazil.E-mail: rosier@.brIV Laboratoires Dubernet Oenologie, Rue de la Combe du Meunier, nº 35, 11.100, Montredon-Corbières, France.E-mail: leiladfalcao@.brABSTRACTThe objective of this work was to assess and characterize two clones, 169 and 685, of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes and toevaluate the wine produced from these grapes. The experiment was carried out in São Joaquim, SC, Brazil, during the 2009 harvest season. During grape ripening, the evolution of physical-chemical properties, phenolic compounds, organic acids, and anthocyanins was evaluated. During grape harvest, yield components were determined for each clone. Individual and total phenolics, individual and total anthocyanins, and antioxidant activity were evaluated for wine. The clones were also assessed regarding the duration of their phenological cycle. During ripening, the evolution of phenolic compounds and of physical-chemical parameters was similar for both clones; however, during harvest, significant differences were observed regarding yield, number of bunches per plant and berries per bunch, leaf area, and organic acid, polyphenol, and anthocyanin content. The wines produced from these clones showed significant differences regarding chemical composition. The clones showed similar phenological cycle and responses to bioclimatic parameters. Principal component analysis shows that clone 685 is strongly correlated with color characteristics, mainly monomeric anthocyanins, while clone 169 is correlated with individual phenolic compounds.Index terms:Vitis vinifera, phenolic compounds, phenology, ripeness.RESUMOO objetivo deste trabalho foi avaliar e caracterizar dois clones, 169 e 685, de uvas Cabernet Sauvignon, e avaliar os vinhos produzidos com estas uvas. O experimento foi realizado em São Joaquim, SC, durante a safra de 2009. No período de maturação, foi avaliada a evolução da composição físico-química, dos compostos fenólicos, dos ácidos orgânicos e das antocianinas. Na colheita das uvas, foram determinados os componentes de produtividade para cada clone. Os vinhos foram analisados quanto aos fenólicos individuais e totais, às antocianinas individuais e totais, e à atividade antioxidante. Os clonestambém foram avaliados quanto a seus ciclos fenológicos. Durante o período de maturação, a evolução dos compostos fenólicos e dos parâmetros físico-químicos foi similar para os dois clones; no entanto, no período da colheita, foram observadas diferenças significativas em relação à produtividade, ao número de cachos por planta e de bagas por cacho, à áreafoliar e ao conteúdo de ácidos orgânicos, de polifenóis e de antocianinas. Os vinhos produzidos com estes clones mostraram diferença significativa quanto à composição química. Os clones apresentaram duração do ciclo fenológico eparâmetros bioclimáticos similares. A análise de componentes principais indica que o clone 685 é fortemente correlacionado às características de cor, principalmente às antocianinasmonoméricas, enquanto o clone 169 é correlacionado aos compostos fenólicos individuais.Termos para indexação:Vitis vinifera, compostos fenólicos, fenologia, maturação.IntroductionClonal selection has led to considerable improvements in viticulture, particularly in terms of grape quality and quantity. For Vitis vinifera L., clones are selected mostly for genetic resistance to pests and diseases, and for specific chemical characteristics. Phenotypic variations are often observed among clones of the same variety, and can appear before or after berry ripening (Zamuz et al., 2007).In viticulture, phenology is used to characterize varieties and clones within the same variety, since phenological periods vary according to genotype, climatic conditions, and geographic location (Jones & Davis, 2000).The quality of grapes at harvest is the main factor that influences wine quality. Grape ripening begins with color change and ends at harvest. Studies indicate that different clones of the same variety also show significant differences regarding chemical composition of their grapes. Some clones have the capacity to produce wine with distinct color, aromatic profile, and phenolic content (Santesteban & Royo, 2006).The objective of this work was to assess and characterize two clones, 169 and 685, of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes, cultivatedin São Joaquim, SC, Brazil, during the 2009 harvest season, and to evaluate the wine produced from these grapes.Materials and MethodsThe experiment was carried out at a commercial vineyard located at São Joaquim, SC, Brazil (28°15'12"S and 49°34'51"W, at 1,200-m altitude). The soil of the region is classified as Humic Dystrudept (Cambissolo Húmico alumínico) and is well drained, with medium clay texture, soft friable consistency, high water retention capacity, and absence of stones (Falcão et al., 2008). Meteorological data were obtained from a meteorological station belonging to Centro de Informações de Recursos Ambientais e de Hidrometeorologia de Santa Catarina from Empresa de Pesquisa Agropecuária e Extensão Rural de Santa Catarina (Epagri), located at 1,000 m above sea level and500 m from the vineyard.Two clones, 169 and 685, of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes were evaluated in the 2009 harvest season. The training system used for both clones was the V system, and the rootstock used was 'Paulsen 1103' (Vitis berlandieri Planch x Vitis rupestris Scheele). A random experimental design was used. For all plants, row and vine spacing were 3.0 and 1.5 m, respectively. Twelve plants from each clone were randomly marked in four central rows. The data collected included daily observations of maximum (T max), minimum (T min) and average (T avg) temperatures, rainfall (mm), and air relative humidity (%). These general climatic parameters were used to derive other variables used in viticulture studies, such as thermal amplitude (cumulative difference of daily air temperature, i.e., T max - T min); heat summation requirements, observed for growingdegree-days (GDD) based on 10° C:from Winkler, 1980; and heliothermal index (HI), determined according to Huglin (1978), in which Tb = 10°C (HI = Σ {[(T avg - T b) + (T max - T b)]/2}).Data on budburst, blooming, setting, veraison, and harvest dates for Cabernet Sauvignon vine clones were also evaluated. Budburst, blooming, setting and veraison events are consideredto occur when, for a given varietal, 50% of the plants show physiological response. Harvest data was collected, on the same day, at approximately 23°Brix, which is related to optimal sugar levels, for both clones.The following yield components were evaluated: number of bunches per plant, berry weight (n = 100), bunch weight (n = 10), and number of berries per bunch (n = 10). All parameters were measured at harvest and were used to calculate yield per plant (kg). Plant leaf area (LA) was calculated as the sum of the area of all the leaves of each plant. Individual LA was estimated by nondestructive measuring of the length of the secondary nerves, according to the procedure described by Carbonneau (1976), taking into account the close relationship with the sum of the length of secondary nerves,in which: SN is the sum of the length of secondary nerves. To establish this relationship, the area (cm2) of 150 leaves from each clone was measured using an image analysis system AM 300 (ADC, Hoddesdon, United Kingdom).The monitoring of grape ripening began at veraison, when approximately 50% of the berries had turned red. The samples were collected at ten-day intervals. Each sample consisted of a total of 240 berries (eight berries per vine) for each clone. For ripening analyses, juice was squeezed from 30 fresh randomly selected berries, in triplicate. The samples were analyzed according to Office International de la Vigne et du Vin (1990) procedures for pH, titratable acidity (TA, mg tartaric acid100 g-1 grape skin), and total soluble solids (TSS, °Brix). The maturation index (MI) was obtained from the TSS/TA ratio. Total phenolics (TP, mg gallic acid 100 g-1 grape skin) (Singleton & Rossi, 1965) and total monomeric anthocyanins (TMA, mg malvidin 3-glucoside 100 g-1 grape skin) (Giusti & Wrolstad, 2001) were determined by extract from grape skins (90 berries) macerated overnight in methanol:HCl (99:1). Organic acid determination (tartaric, malic, citric, succinic, and lactic acid) was carried out using a Shimadzu liquid chromatograph (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan); the column (4.6x250 mm, 5 µm particle size) and guard column (4.6x12.5 mm) were C18 reversed-phase (Hichrom, Berkshire, United Kingdom). For the analyses, grape juice was squeezed from 30 randomly selected fresh berries, in triplicate, and thencentrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min, diluted in Milli-Q purified water by a factor of 10, filtered through a 0.45 µm PTFE membrane (Millipore), and injected into a high pressure liquid chromatograph (HPLC). The analyses were carried out using external standardization, with isocratic elution and detection at 212 nm (Escobal et al., 1998).Wines from each Cabernet Sauvignon clone were produced under the same microvinification conditions at Epagri's Estação Experimental de Videira, Videira, SC, Brazil. Wines were analyzed between six and eight months after microvinification. They were assessed for total polyphenols (TP, mg L-1 gallic acid) (Singleton & Rossi Junior, 1965). 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical activity was measured by the extinction of the maximum absorption at 517 nm (Kim et al., 2002), and TMA was determined by the pH difference method (Giusti & Wrolstad, 2001). Anthocyanin analyses (malvidin, peonidin, and delphinidin-3-glucoside) were carried out using a Shimadzu liquid chromatograph, (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) according to García-Falcón et al. (2007). Phenolic content (catechin, quercetin, trans-resveratrol, gallic acid, ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, and caffeic acid) was analyzed with a method validated in the laboratory, by internal standardization(16.2 mg L-1 of morin solution). The mobile phase consisted of acetic acid in filtered Milli-Q water (pH 2.6) as solvent A, and 20% of solution A in acetonitrile as solvent B. Elution was done using a linear gradient: 0-30% of solvent B for 35 min, 30-50% for 5 min, and 50-100% for 15 min. The flow rate was1.2 mL min-1.All analyses were carried out with two replicates, in triplicate. Linear regression; analysis of variance; principal component analysis (PCA); and Tukey's HSD test at 5% probability were performed using the software Statistica 6 (Statsoft, 2001).Results and DiscussionThe average temperature during grape ripening ranged from 11.9 to 20.5°C. The occurrence of cold nights, characteristic of São Joaquim, SC, Brazil, favored the accumulation of sugars and phenolic compounds, especially anthocyanins. The highest temperature was observed (15.2°C) from veraison until harvest, which is considered an important factor for plant physiology,since it influences photosynthesis/respiration balance and, consequently, the accumulation of energy for grape development during this period (González-Neves et al., 2007). Air relative humidity during the phenological cycle was above 87%, which is typical of southern Brazil and suitable for berry development (Esteban et al., 2002). Total rainfall for the cycle evaluated was around 900 mm. Falcão et al. (2008), in studies carried out in the same location, in 2005 and 2006, with Cabernet Sauvignon grapes, found rainfall values of 900 and 600 mm, respectively.Little difference was observed in the duration of the phenological phases for both clones (Figure 1). Clone 169 had a cycle of 209 days, and clone 685 of 205 days. Regina & Audeguin (2005) evaluated three clones of the Syrah variety and found a four-day difference for the entire phenological cycle. However, a greater difference was observed in this study between the blooming and setting periods: the duration for clone 169 was 23 days longer. Ewart et al. (1993), while assessing Sauvignon Blanc clones in the same year, observed small and insignificant differences from veraison to harvest.The Winkler index (GDD) and Hunglin's HI are widely used to determine the thermal units necessary for the vine to complete the different phases of the phenological cycle, mainly as a guide for the selection of different clones of the same variety, and as a tool to indicate the region's potential for growing quality grapes. In terms of Winkler regions, São Joaquim, SC, Brazil, is classified as 'Region I' (<1,389 GDD), i.e., a "cold region" (Figure 1), taking into account the summed GDD results for the phenological cycle (budburst to harvest) of both clones(approximately 1,200 GDD). These results are in agreement with those found by Falcão et al. (2010) and Gris et al. (2010), who also evaluated different varieties in this location. For the HI, the region is classified as HI1, also considered cold (<1,500), according to the geoviticulture multicriteria climatic classification system (Tonietto & Carbonneau, 2004). There was no significant difference between clones 169 and 685 regarding heat summation requirements. Fallahi et al. (2005), while assessing different clones, observed no significant difference between total thermal requirements for clones of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes, in the same harvest.The determination of LA provides information on the relationship between plant photosynthesis and yield and fruit quality. The clones showed significant difference (p<0.05) for this character (Table 1). Clone 685 had higher LA per plant than clone 169, and showed higher results regarding yield components, which is in agreement with Santesteban & Royo (2006), who reported that LA is related to plant vigor.Clone 685 showed higher yield (p<0.05) than clone 169, with more bunches per plant, higher bunch weight, and more berries per bunch. These differences are directly related to the rainfall amounts during veraison, while yield is positively related to the duration of the phenological cycle. According to Mota et al. (2009), rootstock significantly influences yield. However, in thisstudy, since the clones came from the same location and rootstock, and the harvest period and phenology were similar, the differences observed can be attributed exclusively to the genetic characteristics of each clone. These results are similar to those obtained by Wolpert et al. (1995), when evaluating seven Cabernet Sauvignon clones from California. The authors found significant differences regarding yield, and bunch and berry weights. These results agree with those reported by Alonso et al. (2004), who observed variability between clones of the Albariño variety grown in Spain.The evolution of TSS for the two clones was very similar (Figure 2), with a progressive increase until the end of the ripening period, reaching °Brix values of 23.5 and 24.0 for clones 169 and 685, respectively. The pH values increased up to 50 days from veraison, and then decreased until the end of the ripening period, reaching values of 3.51 and 3.49 for clones 169 and 685, respectively; no significant differences (p<0.05) were observed. A significant correlation (p<0.05) was obtained between pH decrease and acidity increase for clones 169 (r = 0.88) and 685 (r = 0.86). The MI, which indicates sugar-acid balance in grapes, increased progressively during ripening, with end values at harvest of 31.3 and 39.3 for clones 169 and 685, respectively.There was significant difference (p<0.05) for TMA content, which increased during ripening of both clones; clone 685 had the highest concentration at harvest (411.5 mg 100g-1 skin).A significant difference (p<0.05) was also observed between the two clones regarding TP concentration; clone 169 had the highest concentration (685.9 mg 100g-1 skin). According to Mori et al. (2005), the accumulation of phenolic compounds in grape berries is favored mainly by low temperatures during ripening, which was evidenced in São Joaquim, SC, Brazil, and could explain the high phenolic concentration. However, since both clones were evaluated in the same vineyard and vintage, and were influenced by the same temperatures, the differences observed in TP and TMA content may indicate different characteristics regarding the phenolic content of each clone.A significant correlation was observed (p<0.05) between TMA and clone 685 (R>0.9); clone 169 showed a higher correlation with TP content (R>0.9), which indicates that the phenolic data obtained during ripening can be used as a tool to differentiate between these clones.For the two clones, malic acid predominates in the early ripening stage (Figure 3), which is intensely synthesized during the budburst and setting periods; however, its concentration decreases during ripening, due to the predominance of degradation reactions. A decrease in tartaric acid was also observed during ripening. The presence of lactic acid was not detected in any grape sample. At harvest, grapes showed predominance of different acids in must, with the highest concentration of malic acid for clone 685 and of tartaric acid for clone 169. This difference can be attributed to the larger LA of clone 685, since malic acid is mostly synthesized in leaves.Zamuz et al. (2007), who analyzed different clones of the Albariño variety from the same location and harvest, found similar results. The authors observed a significant difference among clones regarding physical-chemical parameters in must, at harvest, which indicates that classical parameters could be used to differentiate between clones of the same grape variety. Ferrandino & Guidoni (2010), while evaluating different clones of the Barbera variety grown in the same location and in the same and different harvests, also found that ripening data on pH, soluble solids, and total acidity showed significant differences between clones.Flavonoid and nonflavonoid phenolic compounds (Table 2) represent the main polyphenols in red wines, and are widely used to differentiate between wines produced from different grape varieties. However, few studies use the main phenolic compounds to differentiate wines produced with different clones of the same variety. Wines from clone 169 showed the highest concentrations of all individual phenolics determined by HPLC, of which catechin was predominant. This clone also showed the highest antioxidant activity. Wines produced from clone 685 showed the highest concentrations of monomeric anthocyanins, especially malvidin 3-glucoside. Forveille et al. (1996) demonstrated that clones differ regarding anthocyanin composition.Principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out with the data on grape composition at harvest, yield components, LA, and chemical composition of wines produced from the clones (Figure 4); all results showed significant difference (p<0.05). PC1 x PC2 explained 98.69% of the total variability. The first component represented 95% of the total variability and could be considered a "clone", since both clones were distributed along PC1, showing a clear separation of the grape and wine samples according to the clone. Clone 685 showed a strong positive correlation with color parameters, such as TMA, malvidin, delphinidin and peonidin 3-glucoside, as well as with yield components and LA. Clone 169 was strongly positively correlated with individual phenolic compounds determined by HPLC, total polyphenols, and DPPH. These results agree with those observed in other studies, which indicate that it is possible to differentiate between clones of the same grape variety with principal component analysis (Zamuz et al., 2007; Ferrandino & Guidone, 2010).Conclusions1. Clones 169 and 685 of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes show similar performance regarding the phenological cycle and the evolution of the compounds during ripening.2. There are significant differences between the clones in terms of chemical composition of grapes and yield components of vines. Clone 685 has higher productivity, higher bunch weight, more bunches per plant, and more berries per bunch.3. The wines produced with clones 169 and 685 show the same chemical characteristics as their grapes.4. Clone 685 is strongly correlated with individual monomeric anthocyanins, while clone 169 shows a higher correlation with total and individual phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity.5. Differences between clones 169 and 685 are exclusively attributed to their chemical composition and physical characteristics, which are potential tools for the characterization and differentiation of different clones from the same grape variety.ReferencesALONSO, S.B.; BLANCO, J.L.S.; RODIGUEZ, M.C.M. Intravarietal agronomic variability in Vitis vinifera L. cv.Albariño. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture,v.55, p.279-282, 2004. [ Links ]CARBONNEAU, A. Analise de la croissance des feuilles du sarment de vigne: estimation de la surface foliare par enchantillonnage. Connaissance Vigne Vin, v.10, p.141-159, 1976. [ Links ]ESCOBAL, A.; IRIONDO, C.; LABORRA, C.; ELEJALDE, E.; GONZALEZ, I. Determination of acids and volatile compounds in red Txakoli wine by high-performance liquid chromatography and gas chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A, v.823, p.349-354, 1998. [ Links ]ESTEBAN, M.A.; VILLANUEVA, M.J.; LISSARRAGUE, J.R. Relationships between different berry components in Tempranillo (Vitis vinifera L.) grapes from irrigated andnon-irrigated vines during ripening. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, v.82, p.1136-1146,2002. [ Links ]EWART, A.J.W.; GAWEL, R.; THISTLEWOOD, S.P.; MCCARTHY, M.G. Evaluation of must composition and wine quality of six clones of Vitis vinifera cv. Sauvignon Blanc. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture, v.33, p.945-951, 1993. [ Links ]FALCÃO, L.D.; BURIN, V.M.; CHAVES, E.S.; VIEIRA, H.J.; BRIGHENTI, E.; ROSIER, J.P.; BORDIGNON-LUIZ, M.T. Vineyard altitude and mesoclimate influences on the phenology and maturation of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from Santa Catarina State. Journal International des Sciences de la Vigne et du Vin, v.44, p.135-150, 2010. [ Links ]FALCÃO, L.D.; CHAVES, E.S.; BURIN, V.M.; FALCÃO, A.P.; GRIS, E.F.; BONIN, V.; BORDIGNON-LUIZ, M.T. Ripening of Cabernet Sauvignon berries from grapevines grown with two different training systems and environmental conditions in a new grapegrowing region in Brazil. Ciencia e Investigación Agraria, v.35, p.321-332, 2008. [ Links ]FALLAHI, E.; FALLAHI, B.; SHAFII, B.; STARK, J.C. Performance of six wine grapes under Southwest Idaho environmental conditions. Small Fruits Review, v.4, p.77-84,2005. [ Links ]FERRANDINO, A.; GUIDONI, S. Anthocyanins, flavonols and hydroxycinnamates: an attempt to use them to discriminate Vitis vinifera L. cv 'Barbera' clones. European Food Research and Technology, v.230, p.417-427, 2010. [ Links ]FORVEILLE, L.; VERCAUTEREN, J.; RUTLEDGE, D.N. Multivariate statistical analysis of two-dimensional NMR data to differentiate grapevine cultivars and clones. Food Chemistry, v.57, p.441-450, 1996. [ Links ]GARCÍA-FALCÓN, M.S.; PÉREZ-LAMELA, C.;MARTÍNEZ-CARBALHO, E.; SIMAL-GÁNDARA, J. Determination of phenolic compounds in wines: influence of bottle storage of young red wines on their evolution. Food Chemistry, v.105, p.248-259, 2007. [ Links ]GIUSTI, M.M.; WROLSTAD, R.E. Characterization and measurement of anthocyanins by UV-visible spectroscopy. In: WROLSTAD, R.E. (Ed.). Current protocols in food analytical chemistry. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2001.F1.2-1.2.13. [ Links ]GONZÁLEZ-NEVES, G.; FRANCO, J.; BARREIRO, L.; GIL, G.; MOUTOUNET, M.; CARBONNEAU, A. Varietal differentiation of Tannat, Cabernet-Sauvignon and Merlot grapes and wines according to their anthocyanic composition. European Food Research and Technology, v.225, p.111-117,2007. [ Links ]GRIS, E.F.; BURIN, V.M.; BRIGHENTI, E.; VIEIRA, H.; BORDIGNON-LUIZ, M.T. Phenology and ripening of Vitis vinifera grape varieties in São Joaquim, southern Brazil: a new South American wine growing region. Ciencia e Investigación Agraria, v.37, p.61-75, 2010. [ Links ]HUGLIN, P. Nouveau mode d'évaluation des possibilitéshéliothermiques d'un milieu viticole. In: SYMPOSIUMINTERNATIONAL SUR L'ÉCOLOGIE DE LA VIGNE, L., Constança, Roumanie, 1978. Annales. Constança: Ministère del'Agriculture et de l'Industrie Alimentaire, 1978.p.89-98. [ Links ]JONES, G.V.; DAVIS, R.E. Climate influences on grapevine phenology, grape composition, and wine production and quality for Bordeaux, France. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, v.51, p.249-261, 2000. [ Links ]KIM, Y.K.; GUO, Q.; PACKER, L. Free radical scavenging activity of red ginseng aqueous extracts. Toxicology, v.172,p.149-156, 2002. [ Links ]MORI, K.; SUGAYA, S.; GEMMA, H. Decreased anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape berries grown under elevated night temperature condition. Scientia Horticulturae, v.105,p.319-330, 2005. [ Links ]MOTA, R.V. da; SOUZA, C.R. de; FAVERO, A.C.; SILVA, C.P.C. e; CARMO, E.L.; FONSECA, A.R.; REGINA, M. de A. Produtividade e composição físico-química de bagas de cultivares de uva em distintos porta-enxertos. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira, v.44, p.576-582, 2009. [ Links ]OFFICE INTERNATIONAL DE LA VIGNE ET DU VIN. Recueil des methodes internationales d'analyse des vins et des mouts. Paris: OIV, 1990. [ Links ]REGINA, M. de A.; AUDEGUIN, L. Avaliação ecofisiológica de clones de videira cv. Syrah. Ciência e Agrotecnologia, v.29, p.875-879, 2005. [ Links ]SANTESTEBAN, L.G.; ROYO, J.B. Water status, leaf area and fruit load influence on berry weight and sugar accumulation of cv. 'Tempranillo' under semiarid conditions. Scientia Horticulturae, v.109, p.60-65, 2006. [ Links ]SINGLETON, V.L.; ROSSI JUNIOR, A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagent. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, v.16,p.144-158, 1965. [ Links ]STATSOFT. Statistica for Windows. Version 6. Tulsa: Statsoft, 2001. [ Links ]。

克伦生葡萄产地在哪,附种植技术回答美国加州是克伦生葡萄的产地,它是美国加州继红提葡萄后,推出的又一个无核葡萄的新品种。

克伦生葡萄的特点是,它的果实不需要经过任何激素处理,就可以实现无核;而且果粒整齐紧凑,果刷坚固,非常耐储耐运。

一、克伦生葡萄产地在哪1、克伦生葡萄的产地克伦生葡萄的产地,在美国加州。

克伦生是美国加州继红提葡萄后,推出的又一个无核葡萄的新品种,在1997年时,引进了我国。

2、克伦生葡萄的特点(1)无核化:克伦生葡萄的果实不需要经过任何激素处理,就可以实现无核。

(2)耐储耐运:克伦生葡萄的果粒整齐紧凑,果刷坚固,非常耐运;克伦生葡萄在9月中旬后就会成熟,它一般在成熟后,还可以在植株上保留1-2个月;将克伦生葡萄采摘后,在无伤无病虫害的条件下,可以储藏较长的时间。

(3)抗逆性强:克伦生葡萄适应性广,具有很强的抗逆性。

常见的白粉病、白腐病、霉霜病等病害对于克伦生葡萄的危害力很小,在山地、平原、丘陵地区均可栽培克伦生葡萄。

二、克伦生葡萄的种植技术1、建园(1)地点:克伦生葡萄需要在土壤深厚肥沃、疏松的砂壤土,排灌良好的平地或者坡地上进行建园种植。

(2)植株行距:一般情况,克伦生葡萄的行距为1mtimes;3m,每公顷栽3330株。

(3)时间:秋植在10月底左右,而春植在2月初为宜。

(4)定植:在给克伦生葡萄定植后,要浇透水并覆盖地膜,以利保墒,而基肥量,则按常规栽培的施用量放置即可。

2、肥水管理(1)以在昆明地区种植克伦生葡萄为例,因为每年的10月到次年5月是干旱季节,所以在给苗木定植后,应视土壤的情况适时浇水。

(2)在定植当年,需要对幼树追肥3-4次,主要以复合肥为主。

3、植株管理(1)一般可以采用单篱壁架,来栽培克伦生葡萄。

(2)在新梢长到60-70cm时,便需要进行第一次摘心,而且每当副梢长到50-60cm时,就要反复摘心,需要将株高控制在2m以内。

(3)在克伦生葡萄萌芽前,需要喷1次石硫合剂防治病虫害。

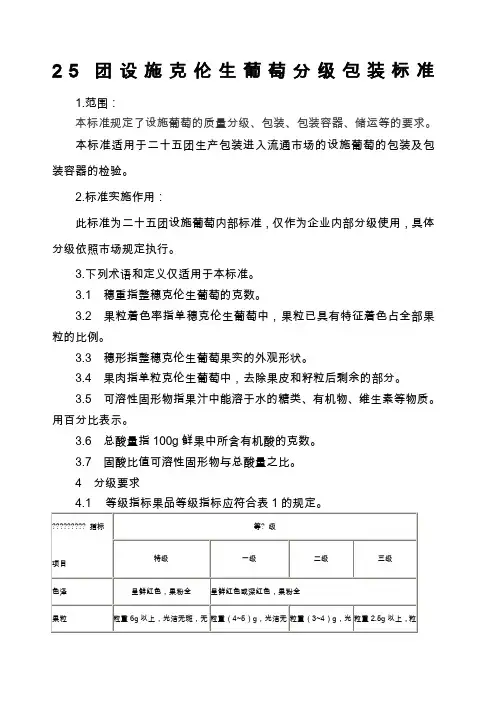

25团设施克伦生葡萄分级包装标准1.范围:本标准规定了设施葡萄的质量分级、包装、包装容器、储运等的要求。

本标准适用于二十五团生产包装进入流通市场的设施葡萄的包装及包装容器的检验。

2.标准实施作用:此标准为二十五团设施葡萄内部标准,仅作为企业内部分级使用,具体分级依照市场规定执行。

3.下列术语和定义仅适用于本标准。

3.1 穗重指整穗克伦生葡萄的克数。

3.2 果粒着色率指单穗克伦生葡萄中,果粒已具有特征着色占全部果粒的比例。

3.3 穗形指整穗克伦生葡萄果实的外观形状。

3.4 果肉指单粒克伦生葡萄中,去除果皮和籽粒后剩余的部分。

3.5 可溶性固形物指果汁中能溶于水的糖类、有机物、维生素等物质。

用百分比表示。

3.6 总酸量指100g鲜果中所含有机酸的克数。

3.7 固酸比值可溶性固形物与总酸量之比。

4 分级要求4.2 卫生指标4.2.1 汞限量按GB2762的规定执行。

4.2.2 六六六、滴滴涕残留量按GB2763的规定执行。

4.2.3 敌敌畏、乐果、马拉硫磷、对硫磷允许残留量按GB5127的规定执行。

5 检验方法5.1 组批同一品种、同一等级、同一批量销售的产品每100件为一个检验批次,不足100件者,以一个批次计。

5.2 抽样按GB/T8855规定执行。

5.3 等级评定5.3.1 色泽、果粒、穗重、果粒着色率、穗形和果肉用目测、口尝、分度值为0.2mm的钢直尺、分度值为0.1g的天平和分度值为20g的度盘秤进行测量。

5.3.2 可溶性固形物、总酸量、固酸比值按附录A执行。

5.3.3 卫生指标5.3.3.1?汞的测定按GB/T5009.17规定的方法测定。

5.3.3.2?六六六、滴滴涕残留量指标按GB/T5009.19规定的方法测定。

5.3.3.3?有机磷农药残留量指标按GB/T5009.20规定的方法测定。

5.3.4 检验规则5.3.4.1?检验时先以感官为主进行初步分级,然后按照表1和4.2中所列各项指标,对样果逐穗进行检查。

栽植克伦生葡萄应注意的问题河北果树HEBEIFRUITS2004(4)它嗣2.3开花期指开花前后各10d(天)内,即新梢长出6~7片叶,此时要在晴天的白天进行充分换气,昼温保持在25~28℃,切勿超过30℃,从见花之日起.夜温上调到18℃左右,不低于15℃为好,若遇特殊天气,短时出现低温10℃左右,也不会出现较大问题.同时终止灌水,湿度控制在60%--70%,但土壤不能干旱.特别是盛花期间,湿度管理重于温度.湿度过大直接影响授粉受精,大大降低坐果率.受精后10~15d(天),将夜温维持在20℃,同时充分补给水分和养分,棚内湿度控制在80%左右为宜.2.4浆果生长期要加大通风量,选晴天彻底换气,棚内昼温控制在28℃左右,夜间尽量降低温度(不关通风窗)在15℃左右,利用降低温度减弱叶片呼吸强度,降低消耗,棚内湿度在70%~80%之间.2.5着色期此时已到4月下旬至5月上旬,要尽量拉大昼夜温差,白天28~30℃,夜温与外界相同,即夜间不关通风窗.当夜温稳定在18℃时,把棚膜推至棚架上下两端,为防大雨冰雹,不能撤膜.3覆盖膜的拆除目前棚膜的处理有两种方式,一是采收基本完毕拆除,二是为了防止雨季病害传播不拆除,晴天将膜推至棚架上下两端,雨天将膜盖上,这样防霜霉病侵害效果极为明显.极早熟葡萄新品种——"早红珍珠"刘令江'.蔡凤臣(1冀鲁果业发展合作会社065000;2廊坊市林业局) 1994年以河北省廊坊市大城县某村葡萄园中发现的"乍娜"芽变单株为基础.自1995年对该母株进行观测与高接试验,通过7年的系统观察及优选繁育,并经高接遗传鉴定,其早熟性状稳定,于2000年在该村建立了试验示范园4.8hm2,2003年7月5日通过了科技局组织的河北省果树专家鉴定小组鉴定, 初定名为"早红珍珠".1成熟期该品种在河北廊坊地区6月20日自然上色,6月28日自然成熟,7月10日左右采摘上市结束,是目前国内最早熟的葡萄品种.2果实品质该品种果实紫红色,均匀一致,酸甜可口,含可溶性固形物16.5%,平均单粒重10g,平均果穗重750g,松紧适度,无脱粒裂果现象.3生态适应性大城地区属黑龙岗流域,土壤pH8.0~8.5左右,年平均气温11.8℃(极高41.2℃.极低一23.6℃),无霜期188d(天),初霜10月21日,终霜4月16日,≥10℃积温5132.7℃.年均降雨量597.7n"gn,该品种休眠期与"乍娜"葡萄相似,但抗旱,耐碱,生长势极强.适应性良好.建议在华北,华东,西北等地区种植发展,在设施栽培条件下,更具有广阔的应用前景.4丰产性该品种每结果枝着生果穗数2个左右,栽植第2年即可挂果,第3年667m2产量可达1750 ,第4~5年进入盛果期,667m2产量可达3000kg以上,丰产性能稳定.栽植克伦生葡萄应注意的I.口]题田少强(河北滦县林业局063700)克伦生葡萄是近几年从国外引进的优良无核晚熟品种,它具有生长势强,抗病,丰产,晚熟,品质好, 耐贮运等优点,深受果农和消费者喜爱,在国内已广泛栽培.但要取得理想的产量和较好的经济效益,必须注意以下几方面的问题.1栽培环境克伦生成熟晚,在无霜期短的区域栽植很难成功,应选择无霜期170d(天)以上的区域栽培.要求土壤质地疏松,排水条件良好.2选择适宜架式克伦生生长势极强,一般管理条件下1年生枝条粗度能达到2cm以上.定植时要适当稀植,株距1.5--2m,行距2.5~3m,采用硼篱架或小棚架架式.3注意肥水管理,控制生长势针对克伦生葡萄生长势强的特点,在栽培管理上要适当控制肥水,主要是少施氮肥,多施磷,钾肥和微量元素肥(如锌,铁,镁肥等);少追肥多施基肥.在不太干旱的情况下.少浇水或不浇水.在北方雨水较多的7,8月份注意雨后及时进行排水,中耕,并用多效唑等进行化控,防止因旺长而影响花芽分化.4注意夏季修剪,合理冬剪栽植克伦生葡萄;)]忌管理粗放.否则很容易造成架面郁闭,新梢徒长,花芽分化不良,影响产量.所以,在整个生长季节要多次修剪,及时去掉那些影响架面通风透光的徒长枝, 细弱枝,对旺长的骨干枝进行多次适当摘心,控制生长势,促发侧枝,在开花前和树体迅速生长期进行主干环剥来提高坐果率,控制树势.45?t曩厦河北果树HEBEIFRUITS2004(4)冬季修剪要因树而异,对幼树,旺树和旺枝采取中,长枝修剪,适当少留枝,多留芽,尽量多保留花芽, 保证足够的结果量,达到以果控树的目的.大量结果以后的树,多采用中,短梢修剪.对夏剪搞的好,树势中庸偏弱的树以短梢修剪为主,适当控制产量.美国早红提葡萄日光温室栽培郭洪涛(河北沧州职业技术学院,沧州061000)早红提(早熟红地球)原产于美国加州,20世纪90年代经山东引入沧州,经过1999~2001年在沧州职业技术学院示范园区栽培,观察到该品种性状稳定,粒大,极早熟,丰产,品质好,耐贮运,上市早,效益高,是温室栽培的理想品种.1植物学特征早红提嫩梢及幼叶呈紫红色,叶面光滑,无茸毛,叶片较薄,成龄叶呈绿色,中大,心脏形,五裂,叶缘锯齿大而锐,叶柄洼拱形,枝条成熟度好,冬芽饱满.2果实特征早红提果穗圆锥形,大穗,一般穗重850g,最大可达2300g,平均粒重9~11g,果形椭圆,整齐,果色鲜红至深红色,着色一致,果肉脆硬,能切片,可溶性固形物含量17%~19%,口感佳,无酸味,果刷长,果粒着生牢固.3生物学特性早红提在沧州地区露地栽培条件下,4月中旬开始萌芽,j{中下旬开花,6月底着色,7月中旬成熟,果实发育期45d(天).比巨峰早30~40d(天).在温室栽培条忤下,2月上旬萌芽,3月下旬开花,4月下旬着色,5月初成熟,从萌芽到果实成熟102d(天).该品种生长旺盛,结实力强,坐果率高,不裂果,不落粒,抗逆性强,保护地栽培基本不感病,是保护地栽培的理想的极早熟品种.4栽培技术要点4.1温室结构温室坐北朝南,东西长80m,南北宽8m,北东西三面用砖砌墙,北墙高2.5ITI,厚50 CTn,内填珍珠岩;每隔3m设一个50cm×50Clll的通风窗,东西墙连接处各设一个门,并建有作业室一处,棚架用无立柱钢架,棚顶高3m.12月20日扣膜,4月30日揭膜,棚膜为聚氯乙烯无滴膜,加盖4 CTn厚草苫,温室内安装暖气管道.4.2栽培密度与架式实行棚篱架栽培,在南边内侧11TI处及离北墙1.51TI处各挖一条定植沟,深宽各46?lrrl,株距0.512"1,用苗320株.4.3肥水管理重施有机肥,整个温室共施用鸡粪(经过发酵)近5000kg;花前叶面喷施0.2%尿素3次;果实膨大期喷4次0.2%磷酸二氢钾.在发芽前,开花前和果实膨大期各浇水一次.4.4枝蔓及果穗管理该品种树势旺,结实率高.棚架部分定植当年昭一主蔓,独龙蔓整枝.篱架部分实行有主干V形架整枝,均为短梢修剪.次年进入结果期,每干留结果枝4~9个.每枝留1花序,弱枝不留果.该品种坐果率高,花前不摘心,让其生理落花落果,以防果实着生过于紧密.果实膨大期后,留20--30片叶再摘心,花序以下副梢抹掉,其他副梢留1~2片叶反复摘心;花序长的要掐去1/4穗尖.花后15--20d(天)进行疏果,疏去形状不正,过密,部位不当,有机械损伤及挤压变形的果粒,每穗留40~70粒为宜,疏果后喷1次多菌灵,然后套袋.开始着色时,铺设反光膜,撕开纸袋,以利于果实上色.4.5温湿度控制萌芽前,温度控制在5℃以上.最高不超过20℃,前期升温缓慢进行.为防止枝条抽干,采取铺地热线的方式,在葡萄株两侧20cm处铺1200W电热线各一根,地下温度控制在3~5℃,以利根系活动;芽眼完全萌发后,再加温10d(天),然后将地热线抽除,铺反光膜.扣棚前10d(天),用5倍石灰氮涂抹结果枝,2月上旬枝条均已萌发,且未发现抽干现象.萌芽至开花期间温度控制l0~22℃之问.发芽至开花期间湿度控制在75%~80%,开花至坐果为70%左右,坐果后为80%左右.5病害防治该品种在温室表现抗病性强,一般不喷药,只在冬剪后萌芽前各喷一次3~5度石硫合剂加200倍五氯酚钠,8月中下旬喷1~3次乙磷铝,以防霜霉病.6果实采收一般在开花后50~65d(天)成熟,开始采收.高温多雨谨防果树炭疽病武深秋(辽宁省辽中县南门街便民巷4l号ll0a00)苹果炭疽病主要危害果实表面,初期出现针头大小的褐色圆形小斑点,之后斑点逐渐扩大并向果肉深入,病斑凹陷,果肉软腐呈圆锥状,变成褐黑色轮纹, 并有同心轮纹状排列的黑色小点,形成分生孢子盘.。

如何以酒瓶重量辨识葡萄酒的高档和低档

葡萄酒在陈放过程中,会出现少许沉渣,是酒石酸结晶的结果,属于正常现象。

有的酒商为了美观,避免沉渣出现,会在葡萄酒中添加澄清剂,明胶等添加剂,正派酒商很少这样做。

在倒酒时为了让沉渣留在酒瓶底部,葡萄酒瓶底部通常设计出一个凹槽,不同的酒瓶,凹槽深度不同。

酒圈网告诉大家,凹槽越深的瓶子,生产成本会高一些,好酒不会采用平底的玻璃瓶,但是很多低端酒也使用深槽酒瓶。

当然,凹槽越深的酒瓶,分量越沉。

葡萄酒瓶一般分波尔多瓶、勃艮第瓶和莱茵瓶。

为了在倒酒时留住渣滓,波尔多瓶采取了高肩和凹形瓶底的设计。

勃艮第瓶矮粗,莱茵瓶瓶颈细长。

我们今天说说波尔多瓶。

波尔多瓶又分为轻瓶、标准瓶、重瓶三类。

一般的VDP和VDT级别的酒,大多采用轻瓶,因为酒在年轻时就被饮用,轻瓶的底部凹陷一般较浅,瓶的质量也较轻,酒圈网售卖的几款VDT级别的红酒,瓶重为430克左右。

标准的AOC产品,大多使用标准瓶,颜色较深,瓶底比较凹。

瓶重465-475克。

像酒圈网的佛伦古堡,瓶重470克。

鲁兹古堡470克,维利奥特干白470克。

列级庄和一些需要陈年的葡萄酒,一般使用重瓶。

玛歌村的CHATEAU FERME,空瓶质量565克,酒圈网在售1999年老树塞根泽克,瓶重540克。

网友也可以观察,这两个酒瓶的底部凹陷更加深一点。

想要种植好克伦生?技巧很重要克伦生葡萄是非常受人大众喜爱的一种葡萄种类,大家都知道如何种植克伦生葡萄吗?了解克仑生葡萄种植技巧吗?本篇文章让一起带大伙看看吧。

一、种植模式克伦生葡萄适宜在光照量足、温度较为微暖的地区种植,长势旺,对土壤的适应能力很强,适应种植在沙土壤里。

想让|克仑生葡萄早产丰产,提高经济效益,建议以小棚架栽培最好,行间距建议在三米左右,株距80厘米最适宜,建议每亩地定植250株。

二、定植沟与改良土壤葡萄生产要想实现早产丰产目标,我们首先要满足葡萄生长过程中对各方面所需的要求,比如水肥,气温等。

通过研究表面,克仑生定植沟宽深在八十厘米左右最好。

方法:把表面上的土和底土分别放在沟的两侧,栽前对沟内填土。

我们首先要在沟的底部铺上有机质,然后用一定比例的农家肥与土壤相互搅拌回填。

三、栽植方法春季在十厘米深的地温为十度左右进行栽植,为了能让苗木补充好水分,栽植前要先用清水把苗木泡上一段时间,过后再修剪根系与枝梢,搭配好分类,分别栽植,有利于长势整齐方便管理,根据设计好的株行间距离挖好栽穴,栽植时要把苗木根系根系向周围延伸,然后淌平土层面,覆膜,以防土壤内水分流失。

四、管理技巧1.要及时做好幼树栽植管理工作,及时对植株修剪,避免养分不足,影响树势。

2.根据芽的质量情况适当进行抹牙,留强去弱,每个株留1~2个芽,其余的全部抹除3.人工栽培出的卷须对果树是有危害的,会影响植株生长,还会消耗树体养分,因此我们要及时摘除掉。

4.克伦生葡萄长势旺,如果不对其进行及时的摘心,会影响果树生长发育,定植的那年进行摘心三次,避免新梢徒长,促枝蔓生长,促进芽的分化,降低成花时的节位,保障次年的结果。

根据生长情况及时摘心。

克伦生葡萄抗逆性非常的强,像我国常见的葡萄病毒例如霜霉病、炭疽病等病害对克伦生的影响非常小,克伦生葡萄适宜贮存、运输性强。

通常在9月中旬开始成熟,有1—2个月的挂果期。

以上就是我总结的一些克仑生葡萄种植技巧啦,希望能帮助到大家。

克伦生葡萄栽培技术克伦生无核,别名克里森无核、排红无核、可伦生无核、淑女红。

美国1983年培育,外观漂亮,品质好,耐运耐贮,果实的市场销售很好,价格明显高于红提葡萄。

果穗中等大小,有歧肩,圆锥形,平均单穗重500克,最大穗重1500克。

果粒亮红色,充分成熟时为紫红色,上有较厚白色果霜,平均单粒重4克,环剥和基因的应用可使果粒增加到6-8克。

果肉浅黄色,半透明肉质,果肉较硬,果皮中等厚,不易与果肉分离,风味甜,可溶性固形物含量可达19%以上,糖酸比大于20:1。

采前不裂果,采后不落粒,品质极佳。

嫩稍红绿色,有光泽,无绒毛。

幼叶紫红色,叶缘绿色。

成熟叶片中等大小,绿色,深五裂,锯齿中等锐,叶柄长,叶柄凹闭合圆形或椭圆形。

栽培技术要点:1.建园克伦生葡萄长势旺,最好采用棚架栽培或“高宽垂”架势栽培。

行距为2-4米,株距0.5-1米,亩栽250-300株。

应选择土壤深厚、肥沃、疏松的沙壤土或轻壤土,PH值6-7.5,排水良好的平地或坡地,无霜期在170天以上的地段建园。

春季栽植时应在地下土温达7-10度时进行,栽植深度一般可按苗木在苗圃内的深度栽植。

栽苗时要使根系向四周自然伸展,用细土填埋根部位,再轻轻晃动,顺架向上提苗,然后埋土20厘米,把整个定植沟面整修淌平做好沟梗,小水浇灌。

3日后栽顺植沟覆盖地膜,将苗木地上部分破膜露外,再用细土把苗木破空处连同膜上苗木轻轻盖严,形成馒头状,以利保墒节水,促其发芽,提高苗木成活率。

2.栽后当年管理抹芽时间可在能辨别芽的质量好坏时进行,留强去弱,每株选留1-2个最壮芽,其余一律抹掉。

间隔摘心,克伦生葡萄长势旺,当年栽植的苗就可长到2米以上,按常规管理不但浪费资源,还容易使冬芽萌发,影响第二年的产量。

如果让其自然生长,则下面的芽眼不充实,冬剪后第二年基本没有花序。

正确的做法是当新稍长到60-70公分时第一次摘心,只保留顶端的副稍和需要做结果枝的副稍,其余的全部抹掉。

以后的副稍间隔40-50公分反复摘心,最后控制到1.5-2米。

核鲜食葡萄新秀―克伦生

克伦生是美国加州继红提葡萄之后推出的又一无核葡萄新品种。

由农业部葡萄新品种项目课题组引进我国,经过4年在国内试种,我国葡萄专家在综合考察其生长状况、果实性状和市场前景后认为,该品种是目前较有发展潜力的无核葡萄品种。

其特点如下:

味美色艳。

果穗圆锥形,中等大小,果粒整齐紧凑,穗重800克左右,最大穗重1600克。

果粒椭圆稍长型,颜色鲜红透亮,果霜鲜艳,单粒重6―8克,可溶性固形物含量20%―25%,糖酸比25.9:1,果肉浅红色,肉质脆能切片,既可鲜食又可制干。

果皮脆,可以随果实一起食用。

真正无核化。

克伦生果实不需要任何激素处理而无核。

这是大多无核葡萄不具有的特性。

耐储耐运。

克伦生葡萄果肉坚硬肉质脆能切片,果皮不易剥离,果粒整齐紧凑,果刷坚固,非常耐储、耐运;克伦生9月中旬开始成熟,成熟后在植株上可以继续保留1―2个月,采摘后无伤无病虫害的果穗在自然条件下完全可以储藏至元旦和春节。

抗逆性强,适应性广。

克伦生抗逆性极强,在我国流行的霜霉病、白腐病、炭疽病、白粉病等病害对克伦生的危害力很弱。

山地、平原、丘陵地均可栽培。

市场前景好。

克伦生葡萄在欧美市场很受欢迎。

美国加州连续三年超市价格保持每公斤3.99美元不变,而同期红提的价格仅为每公斤1.99美元;国内于今年9月份有少量

克伦生葡萄上市,主要供应北京和广州、深圳等大城市,超市价格每公斤20―40元人民币。

克瑞森和克伦生区别,附克瑞森葡萄种植技术

一、克瑞森和克伦生区别

1、成熟期不同:克伦的主产地在华北地区,成熟日期为9月20日,它的优点是上色快,整齐度好,成熟后可以集中上市;克瑞森的主产地在华北、华南地区,它的成熟期比较晚,就算在10月10日都不能完全成熟,它的果实上色慢,整齐度不好。

2、抗病性及品质区别:克伦生是比较正规脱毒的品种,所以它的种苗不带病毒,而且抗病性好,叶片较宽厚,各种土壤都可以进行栽培;克瑞森的抗病性和适应性都没有克伦生好,而且它的果实硬度和口感也比较差。

二、克瑞森葡萄种植技术

1、克瑞森葡萄适应性广,可以适合不同的土壤类型。

但土壤不能过于肥厚,否则容易对其造成徒长,消耗大量养分,在种植时一定要选择中等地力,施肥时要控制氮肥施用量。

2、种植时要按株行距0.8m×4m挖定植穴,定植穴的深度不能小于60cm。

在土壤肥力较差的地块,每亩要施腐熟有机肥大概5000kg 与表土混均填入穴底,定植的最佳时间是5月上、中旬,种植前要先对苗木进行修根,然后用3%-5%石灰水消毒。

3、由于该品种长势比较快,所以座果率会比较低,可以在结果初期时,减去不定梢的质感,留壮梢结果。

4、克瑞森是一种高产品种,所以控制其产量对优化葡萄的品质

和色泽非常重要。

在它生长期间,一定要保证床土湿度,这样可以使越冬芽第2年延后萌发,保证其成活率。

葡萄平民品种中的“泰山”,价格让人眼红,你猜是谁?没错,说的是克伦森(也叫克伦生、克瑞森等),是你们猜对的答案吗?不着急,且来看看它到底怎么对得起这个称呼的!克伦森,9月中旬左右成熟,每公斤可达二十多元,亩效益最多十多万,最大的特点是价格一直很稳,小黑用“稳如泰山”来做了个夸张象征,如山东地区收购价基本都是稳定在7~9元1斤。

不管在国内还是国外,是个市场前景很好的品种。

曾经美国加州连续三年超市价格保持每公斤3.99美元(人民币27.43元左右)不变,而同期红提的价格仅为每公斤1.99美元(人民币13.68元左右)。

一般主要供应北京和广州、深圳等大城市,超市价格每公斤20~40元人民币。

克伦森属于晚熟品种,经过国内4年的试种,现在管理技术方面已相对成熟,被我国葡萄专家认为是较有发展潜力的无核葡萄品种。

9月份左右开始成熟,熟后在树上还可保留1~2个月,无病无虫的果穗采下后在自然条件下还可储存至元旦和春节,冷库储藏可到来年5月份,商品价值非常好。

总的来说,克伦森的储存期很优秀,一般可储存4个月以上。

克伦森吃起来口感像荔枝一样甜,果色红亮色,果霜鲜艳,单粒重6~8克,可溶性固形物含量20%~25%,糖酸比5.9:1,果肉浅红色,肉质脆能切片。

该品种果实不需要任何激素处理而无核,抗逆性极好,抗霜霉病、白腐病、炭疽病、白粉病等病害。

在山地、平原、丘陵地都可以栽培,再加上如今技术也相对成熟了。

当然咯,万物都是有两面性的。

第一个管理关键点是营养供应,因为克伦森的挂果期较长,且根系也比较发达,大肥大水得伺候着,生产成本会高些。

另外一个关键点是上色问题,产量若追求太高,控制不了,那上色就很难,今年有些基地因为产量高导致不上色就很愁人。

克伦森一般标准亩产量要控制在3000~4000斤。

目前克伦森产量有限,价格相对较好,除了市场供求关系的影响,当然也少不了葡农的思想认识。

目前听说四川的品质颜色是最好的,其他地区如山东、山西、河北、河南也有种植。

克伦生葡萄前景克仑生葡萄前景克仑(Cruzan)位于美丽的加勒比海地区,是一个著名的葡萄园。

这里有宜人的气候,充足的阳光和适宜的土壤,非常适合种植葡萄。

随着时代的发展和科技的进步,克仑已经成为一个现代化、高效率的葡萄种植基地。

克仑生葡萄的前景非常明朗,有着巨大的发展潜力。

首先,克仑地区的气候条件非常适宜葡萄的生长。

高温和持续的阳光能够促进葡萄的光合作用,使其能够充分吸收养分和能量。

此外,加勒比海地区的温暖海风也有助于葡萄的适宜生长。

这样的气候条件使得克仑的葡萄更加丰富多样,口感独特。

其次,克仑采用了现代化的种植技术和管理模式,从而提高了葡萄的产量和品质。

在克仑,葡萄园采用了系统化的灌溉和施肥,保证葡萄的生长环境充足的水源和养分。

此外,克仑还配备了先进的气候控制设备和防治病虫害的技术,保护葡萄的健康生长。

这些先进的技术和设备使得克仑的葡萄得到了更好的保护和管理,品质更加稳定。

第三,克仑地区的葡萄产量正在逐年增加。

近年来,克仑不断引进了更加优良的葡萄品种,并进行了大规模的种植。

这些新品种在克仑的气候和土壤条件下生长得非常良好,产量可观。

此外,克仑的农民还通过合作社等形式,开展规模化的种植,提高了葡萄的产量。

这样的增长趋势使得克仑的葡萄成为了加勒比地区的佼佼者,市场前景广阔。

最后,克仑地区不仅有得天独厚的自然条件,也非常注重品质和可持续发展。

克仑的葡萄采用有机种植方式,不使用化学农药和化肥,保证葡萄的品质和食品安全。

同时,克仑还积极参与环境保护和社会公益活动,如水资源保护、土地复原等。

这些做法让克仑的葡萄获得了国际认证,并在市场上享有盛誉。

总之,克仑生葡萄的前景非常广阔。

气候条件良好、现代化的种植技术和管理模式、逐年增加的产量以及注重品质和可持续发展的理念都为克仑的葡萄带来了巨大的发展潜力。

相信未来的克仑将会成为加勒比地区乃至全球最重要的葡萄产地之一。

葡萄新品系——早克无核

作者:暂无

来源:《中国果业信息》 2019年第3期

“早克无核”是在葡萄品种“克伦生”植株中发现的芽变新品系。

果穗平均重360 g,果穗圆锥形,有时带歧肩;果粒平均重1.2 g,圆球形至短椭圆形。

果粒充分成熟时紫黑色至蓝黑色,果粉中等厚。

肉质脆甜,果汁较多,无香味,无核,可溶性固形物含量17.6%,出汁率74.0%。

果实充分成熟时较耐运输。

产量较低,与“郑州早红”相当,比“夏黑”“克伦生”和“红地球”稍低。

2017年,在云南省农业科学院热区生态农业研究所葡萄基地调查露地栽培3年生树产量,每667 m2产量为980 kg。

在云南省元谋县,2016年12月6—8日破眠,12月21—25日萌芽,2017年2月5—12日开花,4月17日至5月10日果实成熟,比“克伦生”早熟40天左右,果实生育期与“夏黑”和“郑州早红”接近。

据《中国果树》(2018年第6期)《葡萄新品系早克无核的选育》,作者张武等(云南省农业科学院热区生态农业研究所,元谋,651300);通信作者徐成东(云南楚雄师范学院),E-

mail:chtown@。

克伦生葡萄种植技术及技巧克伦生又名克瑞森,是一种晚熟的无核品种,口感独特香甜,甜度最高能达到25%,是高产优质的放在清水里浸泡12个小时左右。

定植株行距控制在1×3米,每栽种222株左右,春植在2月初进行,秋植在10月底左右进行,定植后要浇透水覆盖地膜,以便提高植株的成活率。

3、肥水管理

定植后根据*壤情况适时浇水,以保证苗齐,定植后当年的幼树要追肥3-4次,进行防治。

以上就是关于克伦生葡萄种植技术及技巧的介绍了,克伦生葡萄在市场很受欢迎,具有不错的种植前景,可以考虑栽种。

关于克伦生葡萄的知识,您可能对以上的内容感兴趣,敬请下载使用。

25团设施克伦生葡萄分级包装标准

1.范围:

本标准规定了设施葡萄的质量分级、包装、包装容器、储运等的要求。

本标准适用于二十五团生产包装进入流通市场的设施葡萄的包装及包装容器的检验。

2.标准实施作用:

此标准为二十五团设施葡萄内部标准,仅作为企业内部分级使用,具体分级依照市场规定执行。

3.下列术语和定义仅适用于本标准。

3.1 穗重指整穗克伦生葡萄的克数。

3.2 果粒着色率指单穗克伦生葡萄中,果粒已具有特征着色占全部果粒的比例。

3.3 穗形指整穗克伦生葡萄果实的外观形状。

3.4 果肉指单粒克伦生葡萄中,去除果皮和籽粒后剩余的部分。

3.5 可溶性固形物指果汁中能溶于水的糖类、有机物、维生素等物质。

用百分比表示。

3.6 总酸量指100g鲜果中所含有机酸的克数。

3.7 固酸比值可溶性固形物与总酸量之比。

4 分级要求

4.1等级指标果品等级指标应符合表1的规定。

4.2 卫生指标

4.2.1 汞限量按GB2762的规定执行。

4.2.2 六六六、滴滴涕残留量按GB2763的规定执行。

4.2.3 敌敌畏、乐果、马拉硫磷、对硫磷允许残留量按GB5127的规定执行。

5 检验方法

5.1 组批同一品种、同一等级、同一批量销售的产品每100件为一个检验批次,不足100件者,以一个批次计。

5.2 抽样按GB/T8855规定执行。

5.3 等级评定

5.3.1 色泽、果粒、穗重、果粒着色率、穗形和果肉用目测、口尝、分度值为0.2mm的钢直尺、分度值为0.1g的天平和分度值为

20g的度盘秤进行测量。

5.3.2 可溶性固形物、总酸量、固酸比值按附录A执行。

5.3.3 卫生指标

5.3.3.1汞的测定按GB/T5009.17规定的方法测定。

5.3.3.2六六六、滴滴涕残留量指标按GB/T5009.19规定的方法测定。

5.3.3.3有机磷农药残留量指标按GB/T5009.20规定的方法测定。

5.3.4 检验规则

5.3.4.1检验时先以感官为主进行初步分级,然后按照表1和4.2中所列各项指标,对样果逐穗进行检查。

卫生指标经检测不合格不得销售。

5.3.4.2经检验评定合格的果实,应按其实际等级定级。

若合格果实达不到本等级允许指标时,可下降一个等级。

6 标签、包装、运输和贮存

6.1 标签应符合GB7718的规定。

标明产品名称、产品标准号、质量等级、净重、产地、包装日期等。

6.2 包装可用纸箱、苯板箱等包装,盛装果实的各种容器,必须清洁卫生、坚固耐压、无毒、无异味、箱两端须有通气孔。

克伦生葡萄果实采摘后应立即按标准的规定挑选分级,包装验收。

6.3 运输运输中应防止烈日暴晒、雨淋,运输工具必须清洁卫生,严禁与有毒、有异味等有害物品混装、混运。

6.4 贮存

6.4.1 应在阴凉、通风、清洁、卫生的地方进行,严防日晒、雨淋、冻害及有毒有害物等污染。

6.4.2 若进行长期贮存的克伦生葡萄必须在冷库中进行预冷,在短时间内把葡萄品温降到(0~4)℃,以利于贮存。

二十五团

二〇一三年十月二十日。