伍德里奇《计量经济学导论》(第6版)复习笔记和课后习题详解-第二篇(第10~12章)【圣才出品】

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:2.44 MB

- 文档页数:100

伍德里奇计量经济学导论第6版笔记和课后答案

第1章计量经济学的性质与经济数据

1.1 复习笔记

考点一:计量经济学及其应用★

1计量经济学

计量经济学是在一定的经济理论基础之上,采用数学与统计学的工具,通过建立计量经济模型对经济变量之间的关系进行定量分析的学科。

进行计量分析的步骤主要有:①利用经济数据对模型中的未知参数进行估计;②对模型进行检验;③通过检验后,可以利用计量模型来进行相关预测。

2经济分析的步骤

经济分析是指利用所搜集的相关数据检验某个理论是否成立或估计某种关系的方法。

经济分析主要包括以下几步,分别是阐述问题、构建经济模型、经济模型转化为计量模型、搜集相关数据、参数估计和假设检验。

考点二:经济数据★★★

1经济数据的结构(见表1-1)

表1-1 经济数据的结构

2面板数据与混合横截面数据的比较(见表1-2)

表1-2 面板数据与混合横截面数据的比较

考点三:因果关系和其他条件不变★★

1因果关系

因果关系是指一个变量的变动将引起另一个变量的变动,这是经济分析中的重要目标之一。

计量分析虽然能发现变量之间的相关关系,但是如果想要解释因果关系,还要排除模型本身存在因果互逆的可能,

否则很难让人信服。

2其他条件不变

其他条件不变是指在经济分析中,保持所有的其他变量不变。

“其他条件不变”这一假设在因果分析中具有重要作用。

《计量经济学导论》考研伍德里奇考研复习笔记二第1章计量经济学的性质与经济数据1.1 复习笔记一、什么是计量经济学计量经济学是以一定的经济理论为基础,运用数学与统计学的方法,通过建立计量经济模型,定量分析经济变量之间的关系。

在进行计量分析时,首先需要利用经济数据估计出模型中的未知参数,然后对模型进行检验,在模型通过检验后还可以利用计量模型来进行预测。

在进行计量分析时获得的数据有两种形式,实验数据与非实验数据:(1)非实验数据是指并非从对个人、企业或经济系统中的某些部分的控制实验而得来的数据。

非实验数据有时被称为观测数据或回顾数据,以强调研究者只是被动的数据搜集者这一事实。

(2)实验数据通常是通过实验所获得的数据,但社会实验要么行不通要么实验代价高昂,所以在社会科学中要得到这些实验数据则困难得多。

二、经验经济分析的步骤经验分析就是利用数据来检验某个理论或估计某种关系。

1.对所关心问题的详细阐述问题可能涉及到对一个经济理论某特定方面的检验,或者对政府政策效果的检验。

2构造经济模型经济模型是描述各种经济关系的数理方程。

3经济模型变成计量模型先了解一下计量模型和经济模型有何关系。

与经济分析不同,在进行计量经济分析之前,必须明确函数的形式,并且计量经济模型通常都带有不确定的误差项。

通过设定一个特定的计量经济模型,我们就知道经济变量之间具体的数学关系,这样就解决了经济模型中内在的不确定性。

在多数情况下,计量经济分析是从对一个计量经济模型的设定开始的,而没有考虑模型构造的细节。

一旦设定了一个计量模型,所关心的各种假设便可用未知参数来表述。

4搜集相关变量的数据5用计量方法来估计计量模型中的参数,并规范地检验所关心的假设在某些情况下,计量模型还用于对理论的检验或对政策影响的研究。

三、经济数据的结构1横截面数据(1)横截面数据集,是指在给定时点对个人、家庭、企业、城市、州、国家或一系列其他单位采集的样本所构成的数据集。

第12章时间序列回归中的序列相关和异方差性12.1复习笔记考点一:含序列相关误差时OLS 的性质★★★1.无偏性和一致性当时间序列回归的前3个高斯-马尔可夫假定成立时,OLS 的估计值是无偏的。

把严格外生性假定放松到E(u t |X t )=0,可以证明当数据是弱相关时,∧βj 仍然是一致的,但不一定是无偏的。

2.有效性和推断假定误差存在序列相关,即满足u t =ρu t-1+e t ,t=1,2,…,n,|ρ|<1。

其中,e t 是均值为0方差为σe 2满足经典假定的误差。

对于简单回归模型:y t =β0+β1x t +u t 。

假定x t 的样本均值为零,因此有:1111ˆn x t tt SST x u -==+∑ββ其中:21nx t t SST x ==∑∧β1的方差为:()()122221111ˆ/2/n n n t j xt t x x t t j t t j Var SST Var x u SST SST x x ---+===⎛⎫==+ ⎪⎝⎭∑∑∑βσσρ其中:σ2=Var(u t )。

根据∧β1的方差表达式可知,第一项为经典假定条件下的简单回归模型中参数的方差。

因此,当模型中的误差项存在序列相关时,OLS 估计的方差是有偏的,假设检验的统计量也会出现偏差。

3.拟合优度当时间序列回归模型中的误差存在序列相关时,通常的拟合优度指标R 2和调整R 2便会失效;但只要数据是平稳和弱相关的,拟合优度指标就仍然有效。

4.出现滞后因变量时的序列相关(1)在出现滞后因变量和序列相关的误差时,OLS 不一定是不一致的假设E(y t |y t-1)=β0+β1y t-1。

其中,|β1|<1。

加上误差项把上式写为:y t =β0+β1y t-1+u t ,E(u t |y t-1)=0。

模型满足零条件均值假定,因此OLS 估计量∧β0和∧β1是一致的。

误差{u t }可能序列相关。

虽然E(u t |y t-1)=0保证了u t 与y t-1不相关,但u t-1=y t -1-β0-β1y t-2,u t 和y t-2却可能相关。

第1章计量经济学的性质与经济数据1.1复习笔记考点一:计量经济学★1计量经济学的含义计量经济学,又称经济计量学,是由经济理论、统计学和数学结合而成的一门经济学的分支学科,其研究内容是分析经济现象中客观存在的数量关系。

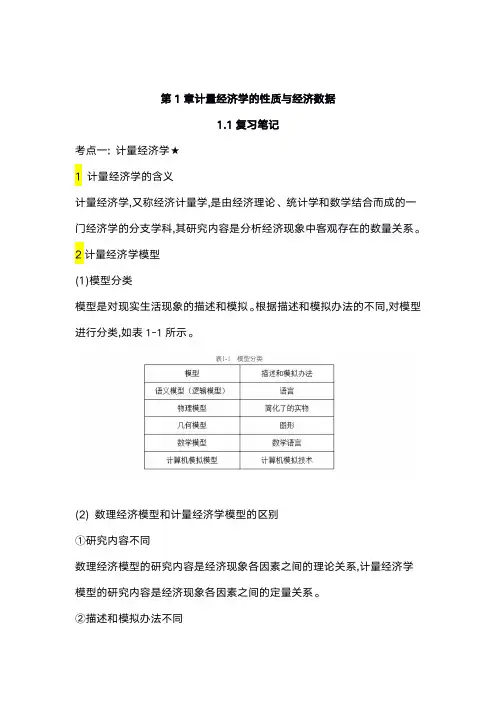

2计量经济学模型(1)模型分类模型是对现实生活现象的描述和模拟。

根据描述和模拟办法的不同,对模型进行分类,如表1-1所示。

(2)数理经济模型和计量经济学模型的区别①研究内容不同数理经济模型的研究内容是经济现象各因素之间的理论关系,计量经济学模型的研究内容是经济现象各因素之间的定量关系。

②描述和模拟办法不同数理经济模型的描述和模拟办法主要是确定性的数学形式,计量经济学模型的描述和模拟办法主要是随机性的数学形式。

③位置和作用不同数理经济模型可用于对研究对象的初步研究,计量经济学模型可用于对研究对象的深入研究。

考点二:经济数据★★★1经济数据的结构(见表1-3)2面板数据与混合横截面数据的比较(见表1-4)考点三:因果关系和其他条件不变★★1因果关系因果关系是指一个变量的变动将引起另一个变量的变动,这是经济分析中的重要目标之计量分析虽然能发现变量之间的相关关系,但是如果想要解释因果关系,还要排除模型本身存在因果互逆的可能,否则很难让人信服。

2其他条件不变其他条件不变是指在经济分析中,保持所有的其他变量不变。

“其他条件不变”这一假设在因果分析中具有重要作用。

1.2课后习题详解一、习题1.假设让你指挥一项研究,以确定较小的班级规模是否会提高四年级学生的成绩。

(i)如果你能指挥你想做的任何实验,你想做些什么?请具体说明。

(ii)更现实地,假设你能搜集到某个州几千名四年级学生的观测数据。

你能得到它们四年级班级规模和四年级末的标准化考试分数。

你为什么预计班级规模与考试成绩成负相关关系?(iii)负相关关系一定意味着较小的班级规模会导致更好的成绩吗?请解释。

答:(i)假定能够随机的分配学生们去不同规模的班级,也就是说,在不考虑学生诸如能力和家庭背景等特征的前提下,每个学生被随机的分配到不同的班级。

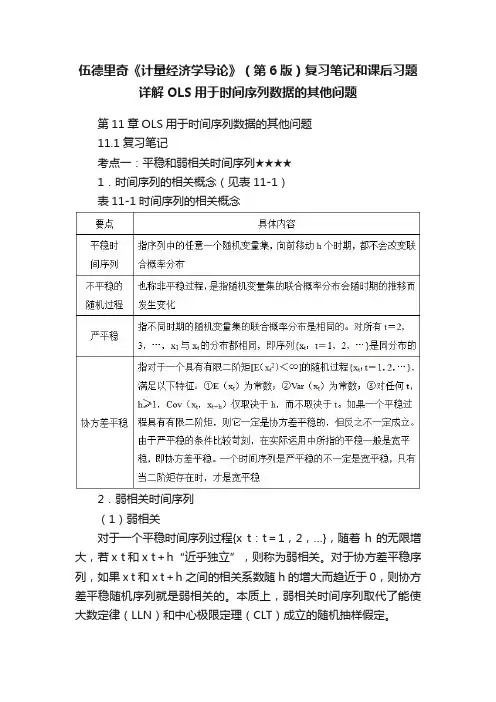

伍德里奇《计量经济学导论》(第6版)复习笔记和课后习题详解OLS用于时间序列数据的其他问题第11章OLS用于时间序列数据的其他问题11.1复习笔记考点一:平稳和弱相关时间序列★★★★1.时间序列的相关概念(见表11-1)表11-1时间序列的相关概念2.弱相关时间序列(1)弱相关对于一个平稳时间序列过程{x t:t=1,2,…},随着h的无限增大,若x t和x t+h“近乎独立”,则称为弱相关。

对于协方差平稳序列,如果x t和x t+h之间的相关系数随h的增大而趋近于0,则协方差平稳随机序列就是弱相关的。

本质上,弱相关时间序列取代了能使大数定律(LLN)和中心极限定理(CLT)成立的随机抽样假定。

(2)弱相关时间序列的例子(见表11-2)表11-2弱相关时间序列的例子考点二:OLS的渐近性质★★★★1.OLS的渐近性假设(见表11-3)表11-3OLS的渐近性假设2.OLS的渐近性质(见表11-4)表11-4OLS的渐进性质考点三:回归分析中使用高度持续性时间序列★★★★1.高度持续性时间序列(1)随机游走(见表11-5)表11-5随机游走(2)带漂移的随机游走带漂移的随机游走的形式为:y t=α0+y t-1+e t,t=1,2,…。

其中,e t(t=1,2,…)和y0满足随机游走模型的同样性质;参数α0被称为漂移项。

通过反复迭代,发现y t的期望值具有一种线性时间趋势:y t=α0t+e t+e t-1+…+e1+y0。

当y0=0时,E(y t)=α0t。

若α0>0,y t的期望值随时间而递增;若α0<0,则随时间而下降。

在t时期,对y t+h的最佳预测值等于y t加漂移项α0h。

y t的方差与纯粹随机游走情况下的方差完全相同。

带漂移随机游走是单位根过程的另一个例子,因为它是含截距的AR(1)模型中ρ1=1的特例:y t=α0+ρ1y t-1+e t。

2.高度持续性时间序列的变换(1)差分平稳过程I(1)弱相关过程,也被称为0阶单整或I(0),这种序列的均值已经满足标准的极限定理,在回归分析中使用时无须进行任何处理。

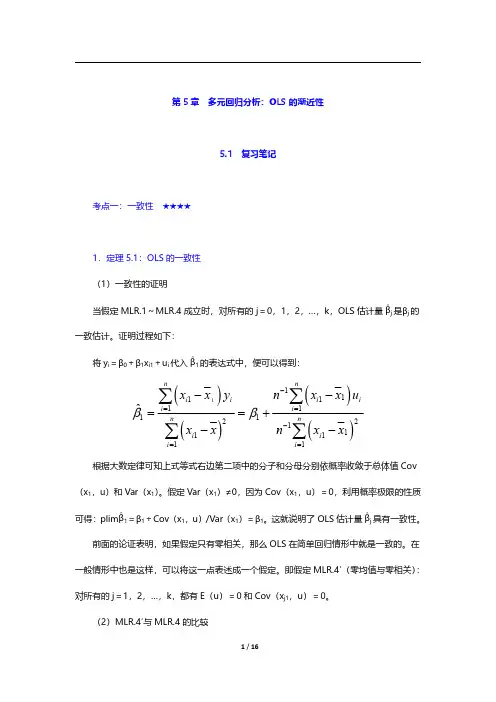

第5章多元回归分析:OLS 的渐近性5.1复习笔记考点一:一致性★★★★1.定理5.1:OLS 的一致性(1)一致性的证明当假定MLR.1~MLR.4成立时,对所有的j=0,1,2,…,k,OLS 估计量∧βj 是βj 的一致估计。

证明过程如下:将y i =β0+β1x i1+u i 代入∧β1的表达式中,便可以得到:()()()()11111111122111111ˆnni ii i i i n ni i i i xx y n x x u xxnxx ββ-==-==--==+--∑∑∑∑根据大数定律可知上式等式右边第二项中的分子和分母分别依概率收敛于总体值Cov (x 1,u)和Var(x 1)。

假定Var(x 1)≠0,因为Cov(x 1,u)=0,利用概率极限的性质可得:plim ∧β1=β1+Cov(x 1,u)/Var(x 1)=β1。

这就说明了OLS 估计量∧βj 具有一致性。

前面的论证表明,如果假定只有零相关,那么OLS 在简单回归情形中就是一致的。

在一般情形中也是这样,可以将这一点表述成一个假定。

即假定MLR.4′(零均值与零相关):对所有的j=1,2,…,k,都有E(u)=0和Cov(x j1,u)=0。

(2)MLR.4′与MLR.4的比较①MLR.4要求解释变量的任何函数都与u 无关,而MLR.4′仅要求每个x j 与u 无关(且u 在总体中均值为0)。

②在MLR.4假定下,有E(y|x 1,x 2,…,x k )=β0+β1x 1+β2x 2+…+βk x k ,可以得到解释变量对y 的平均值或期望值的偏效应;而在假定MLR.4′下,β0+β1x 1+β2x 2+…+βk x k 不一定能够代表总体回归函数,存在x j 的某些非线性函数与误差项相关的可能性。

2.推导OLS 的不一致性当误差项和x 1,x 2,…,x k 中的任何一个相关时,通常会导致所有的OLS 估计量都失去一致性,即使样本量增加也不会改善。

《计量经济学导论》考研伍德里奇版考研复习笔记第1章计量经济学的性质与经济数据1.1 复习笔记一、计量经济学由于计量经济学主要考虑在搜集和分析非实验经济数据时的固有问题,计量经济学已从数理统计分离出来并演化成一门独立学科。

1.非实验数据是指并非从对个人、企业或经济系统中的某些部分的控制实验而得来的数据。

非实验数据有时被称为观测数据或回顾数据,以强调研究者只是被动的数据搜集者这一事实。

2.实验数据通常是在实验环境中获得的,但在社会科学中要得到这些实验数据则困难得多。

二、经验经济分析的步骤经验分析就是利用数据来检验某个理论或估计某种关系。

1.对所关心问题的详细阐述在某些情形下,特别是涉及到对经济理论的检验时,就要构造一个规范的经济模型。

经济模型总是由描述各种关系的数理方程构成。

2.经济模型变成计量模型先了解一下计量模型和经济模型有何关系。

与经济分析不同,在进行计量经济分析之前,必须明确函数的形式。

通过设定一个特定的计量经济模型,就解决了经济模型中内在的不确定性。

在多数情况下,计量经济分析是从对一个计量经济模型的设定开始的,而没有考虑模型构造的细节。

一旦设定了一个计量模型,所关心的各种假设便可用未知参数来表述。

3.搜集相关变量的数据4.用计量方法来估计计量模型中的参数,并规范地检验所关心的假设在某些情况下,计量模型还用于对理论的检验或对政策影响的研究。

三、经济数据的结构1.横截面数据(1)横截面数据集,就是在给定时点对个人、家庭、企业、城市、州、国家或一系列其他单位采集的样本所构成的数据集。

有时,所有单位的数据并非完全对应于同一时间段。

在一个纯粹的横截面分析中,应该忽略数据搜集中细小的时间差别。

(2)横截面数据的重要特征①假定它们是从样本背后的总体中通过随机抽样而得到的。

当抽取的样本(特别是地理上的样本)相对总体而言太大时,可能会导致另一种偏离随机抽样的情况。

这种情形中潜在的问题是,总体不够大,所以不能合理地假定观测值是独立抽取的。

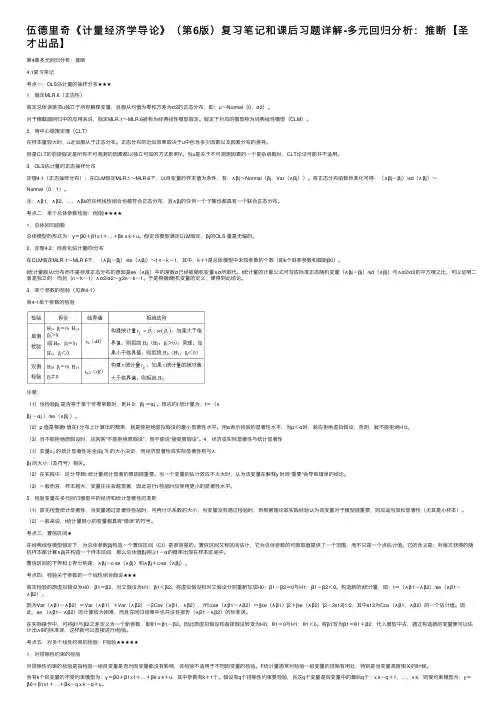

伍德⾥奇《计量经济学导论》(第6版)复习笔记和课后习题详解-多元回归分析:推断【圣才出品】第4章多元回归分析:推断4.1复习笔记考点⼀:OLS估计量的抽样分布★★★1.假定MLR.6(正态性)假定总体误差项u独⽴于所有解释变量,且服从均值为零和⽅差为σ2的正态分布,即:u~Normal(0,σ2)。

对于横截⾯回归中的应⽤来说,假定MLR.1~MLR.6被称为经典线性模型假定。

假定下对应的模型称为经典线性模型(CLM)。

2.⽤中⼼极限定理(CLT)在样本量较⼤时,u近似服从于正态分布。

正态分布的近似效果取决于u中包含多少因素以及因素分布的差异。

但是CLT的前提假定是所有不可观测的因素都以独⽴可加的⽅式影响Y。

当u是关于不可观测因素的⼀个复杂函数时,CLT论证可能并不适⽤。

3.OLS估计量的正态抽样分布定理4.1(正态抽样分布):在CLM假定MLR.1~MLR.6下,以⾃变量的样本值为条件,有:∧βj~Normal(βj,Var(∧βj))。

将正态分布函数标准化可得:(∧βj-βj)/sd(∧βj)~Normal(0,1)。

注:∧β1,∧β2,…,∧βk的任何线性组合也都符合正态分布,且∧βj的任何⼀个⼦集也都具有⼀个联合正态分布。

考点⼆:单个总体参数检验:t检验★★★★1.总体回归函数总体模型的形式为:y=β0+β1x1+…+βk x k+u。

假定该模型满⾜CLM假定,βj的OLS 量是⽆偏的。

2.定理4.2:标准化估计量的t分布在CLM假定MLR.1~MLR.6下,(∧βj-βj)/se(∧βj)~t n-k-1,其中,k+1是总体模型中未知参数的个数(即k个斜率参数和截距β0)。

t统计量服从t分布⽽不是标准正态分布的原因是se(∧βj)中的常数σ已经被随机变量∧σ所取代。

t统计量的计算公式可写成标准正态随机变量(∧βj-βj)/sd(∧βj)与∧σ2/σ2的平⽅根之⽐,可以证明⼆者是独⽴的;⽽且(n-k-1)∧σ2/σ2~χ2n-k-1。

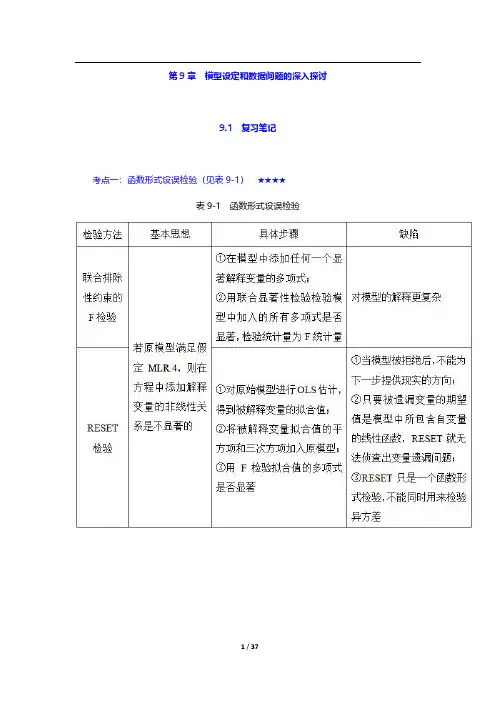

第9章模型设定和数据问题的深入探讨9.1复习笔记考点一:函数形式设误检验(见表9-1)★★★★表9-1函数形式设误检验考点二:对无法观测解释变量使用代理变量★★★1.代理变量代理变量就是某种与分析中试图控制而又无法观测的变量相关的变量。

(1)遗漏变量问题的植入解假设在有3个自变量的模型中,其中有两个自变量是可以观测的,解释变量x3*观测不到:y=β0+β1x1+β2x2+β3x3*+u。

但有x3*的一个代理变量,即x3,有x3*=δ0+δ3x3+v3。

其中,x3*和x3正相关,所以δ3>0;截距δ0容许x3*和x3以不同的尺度来度量。

假设x3就是x3*,做y对x1,x2,x3的回归,从而利用x3得到β1和β2的无偏(或至少是一致)估计量。

在做OLS之前,只是用x3取代了x3*,所以称之为遗漏变量问题的植入解。

代理变量也可以以二值信息的形式出现。

(2)植入解能得到一致估计量所需的假定(见表9-2)表9-2植入解能得到一致估计量所需的假定2.用滞后因变量作为代理变量对于想要控制无法观测的因素,可以选择滞后因变量作为代理变量,这种方法适用于政策分析。

但是现期的差异很难用其他方法解释。

使用滞后被解释变量不是控制遗漏变量的唯一方法,但是这种方法适用于估计政策变量。

考点三:随机斜率模型★★★1.随机斜率模型的定义如果一个变量的偏效应取决于那些随着总体单位的不同而不同的无法观测因素,且只有一个解释变量x,就可以把这个一般模型写成:y i=a i+b i x i。

上式中的模型有时被称为随机系数模型或随机斜率模型。

对于上式模型,记a i=a+c i和b i=β+d i,则有E(c i)=0和E(d i)=0,代入模型得y i=a+βx i+u i,其中,u i=c i+d i x i。

2.保证OLS无偏(一致性)的条件(1)简单回归当u i=c i+d i x i时,无偏的充分条件就是E(c i|x i)=E(c i)=0和E(d i|x i)=E(d i)=0。

CHAPTER 10TEACHING NOTESBecause of its realism and its care in stating assumptions, this chapter puts a somewhat heavier burden on the instructor and student than traditional treatments of time series regression. Nevertheless, I think it is worth it. It is important that students learn that there are potential pitfalls inherent in using regression with time series data that are not present for cross-sectional applications. Trends, seasonality, and high persistence are ubiquitous in time series data. By this time, students should have a firm grasp of multiple regression mechanics and inference, and so you can focus on those features that make time series applications different from cross-sectional ones.I think it is useful to discuss static and finite distributed lag models at the same time, as these at least have a shot at satisfying the Gauss-Markov assumptions. Many interesting examples have distributed lag dynamics. In discussing the time series versions of the CLM assumptions, I rely mostly on intuition. The notion of strict exogeneity is easy to discuss in terms of feedback. It is also pretty apparent that, in many applications, there are likely to be some explanatory variables that are not strictly exogenous. What the student should know is that, to conclude that OLS is unbiased – as opposed to consistent – we need to assume a very strong form of exogeneity of the regressors. Chapter 11 shows that only contemporaneous exogeneity is needed for consistency. Although the text is careful in stating the assumptions, in class, after discussing strict exogeneity, I leave the conditioning on X implicit, especially when I discuss the no serial correlation assumption. As the absence of serial correlation is a new assumption I spend a fair amount of time on it. (I also discuss why we did not need it for random sampling.)Once the unbiasedness of OLS, the Gauss-Markov theorem, and the sampling distributions under the classical linear model assumptions have been covered – which can be done rather quickly – I focus on applications. Fortunately, the students already know about logarithms and dummy variables. I treat index numbers in this chapter because they arise in many time series examples.A novel feature of the text is the discussion of how to compute goodness-of-fit measures with a trending or seasonal dependent variable. While detrending or deseasonalizing y is hardly perfect (and does not work with integrated processes), it is better than simply reporting the very high R-squareds that often come with time series regressions with trending variables.117118SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS10.1 (i) Disagree. Most time series processes are correlated over time, and many of themstrongly correlated. This means they cannot be independent across observations, which simply represent different time periods. Even series that do appear to be roughly uncorrelated – such as stock returns – do not appear to be independently distributed, as you will see in Chapter 12 under dynamic forms of heteroskedasticity.(ii) Agree. This follows immediately from Theorem 10.1. In particular, we do not need the homoskedasticity and no serial correlation assumptions.(iii) Disagree. Trending variables are used all the time as dependent variables in a regression model. We do need to be careful in interpreting the results because we may simply find a spurious association between y t and trending explanatory variables. Including a trend in the regression is a good idea with trending dependent or independent variables. As discussed in Section 10.5, the usual R -squared can be misleading when the dependent variable is trending.(iv) Agree. With annual data, each time period represents a year and is not associated with any season.10.2 We follow the hint and writegGDP t -1 = α0 + δ0int t -1 + δ1int t -2 + u t -1,and plug this into the right-hand-side of the int t equation:int t = γ0 + γ1(α0 + δ0int t-1 + δ1int t-2 + u t-1 – 3) + v t= (γ0 + γ1α0 – 3γ1) + γ1δ0int t-1 + γ1δ1int t-2 + γ1u t-1 + v t .Now by assumption, u t -1 has zero mean and is uncorrelated with all right-hand-side variables in the previous equation, except itself of course. SoCov(int ,u t -1) = E(int t ⋅u t-1) = γ1E(21t u -) > 0because γ1 > 0. If 2u σ= E(2t u ) for all t then Cov(int,u t-1) = γ12u σ. This violates the strictexogeneity assumption, TS.2. While u t is uncorrelated with int t , int t-1, and so on, u t is correlated with int t+1.10.3 Writey* = α0 + (δ0 + δ1 + δ2)z* = α0 + LRP ⋅z *,and take the change: ∆y * = LRP ⋅∆z *.11910.4 We use the R -squared form of the F statistic (and ignore the information on 2R ). The 10% critical value with 3 and 124 degrees of freedom is about 2.13 (using 120 denominator df in Table G.3a). The F statistic isF = [(.305 - .281)/(1 - .305)](124/3) ≈ 1.43,which is well below the 10% cv . Therefore, the event indicators are jointly insignificant at the 10% level. This is another example of how the (marginal) significance of one variable (afdec6) can be masked by testing it jointly with two very insignificant variables.10.5 The functional form was not specified, but a reasonable one islog(hsestrts t ) = α0 + α1t + δ1Q2t + δ2Q3t + δ3Q3t + β1int t +β2log(pcinc t ) + u t ,Where Q2t , Q3t , and Q4t are quarterly dummy variables (the omitted quarter is the first) and the other variables are self-explanatory. This inclusion of the linear time trend allows the dependent variable and log(pcinc t ) to trend over time (int t probably does not contain a trend), and the quarterly dummies allow all variables to display seasonality. The parameter β2 is an elasticity and 100⋅β1 is a semi-elasticity.10.6 (i) Given δj = γ0 + γ1 j + γ2 j 2 for j = 0,1, ,4, we can writey t = α0 + γ0z t + (γ0 + γ1 + γ2)z t -1 + (γ0 + 2γ1 + 4γ2)z t -2 + (γ0 + 3γ1 + 9γ2)z t -3+ (γ0 + 4γ1 + 16γ2)z t -4 + u t = α0 + γ0(z t + z t -1 + z t -2 + z t -3 + z t -4) + γ1(z t -1 + 2z t -2 + 3z t -3 + 4z t -4)+ γ2(z t-1 + 4z t -2 + 9z t -3 + 16z t -4) + u t .(ii) This is suggested in part (i). For clarity, define three new variables: z t 0 = (z t + z t -1 + z t -2 + z t -3 + z t -4), z t 1 = (z t -1 + 2z t -2 + 3z t -3 + 4z t -4), and z t 2 = (z t -1 + 4z t -2 + 9z t -3 + 16z t -4). Then, α0, γ0, γ1, and γ2 are obtained from the OLS regression of y t on z t 0, z t 1, and z t 2, t = 1, 2, , n . (Following our convention, we let t = 1 denote the first time period where we have a full set of regressors.) The ˆj δ can be obtained from ˆj δ= 0ˆγ+ 1ˆγj + 2ˆγj 2.(iii) The unrestricted model is the original equation, which has six parameters (α0 and the five δj ). The PDL model has four parameters. Therefore, there are two restrictions imposed in moving from the general model to the PDL model. (Note how we do not have to actually write out what the restrictions are.) The df in the unrestricted model is n – 6. Therefore, we wouldobtain the unrestricted R -squared, 2ur R from the regression of y t on z t , z t -1, , z t -4 and therestricted R -squared from the regression in part (ii), 2r R . The F statistic is120222()(6).(1)2ur r ur R R n F R --=⋅-Under H 0 and the CLM assumptions, F ~ F 2,n -6.10.7 (i) pe t -1 and pe t -2 must be increasing by the same amount as pe t .(ii) The long-run effect, by definition, should be the change in gfr when pe increasespermanently. But a permanent increase means the level of pe increases and stays at the new level, and this is achieved by increasing pe t -2, pe t -1, and pe t by the same amount.10.8 It is easiest to discuss this question in the context of correlations, rather than conditional means. The solution here does both.(i) Strict exogeneity implies that the error at time t , u t , is uncorrelated with the regressors in every time period: current, past, and future. Sequential exogeneity states that u t is uncorrelated with current and past regressors, so it is implied by strict exogeneity. In terms of conditional means, strict exogeneity is 11E(|...,,,,...)0t t t t u -+=x x x , and so u t conditional on any subset of 11(...,,,,...)t t t -+x x x , including 1(,,...)t t -x x , also has a zero conditional mean. But the lattercondition is the definition of sequential exogeneity.(ii) Sequential exogeneity implies that u t is uncorrelated with x t , x t -1, …, which, of course, implies that u t is uncorrelated with x t (which is contemporaneous exogeneity stated in terms of zero correlation). In terms of conditional means, 1E(|,,...)0t t t u -=x x implies that u t has zero mean conditional on any subset of variables in 1(,,...)t t -x x . In particular, E(|)0t t u =x .(iii) No, OLS is not generally unbiased under sequential exogeneity. To show unbiasedness, we need to condition on the entire matrix of explanatory variables, X , and use E(|)0t u =X for all t . But this condition is strict exogeneity, and it is not implied by sequential exogeneity.(iv) The model and assumption imply1E(|,,...)0t t t u pccon pccon -=,which means that pccon t is sequentially exogenous. (One can debate whether three lags isenough to capture the distributed lag dynamics, but the problem asks you to assume this.) But pccon t may very well fail to be strictly exogenous because of feedback effects. For example, a shock to the HIV rate this year – manifested as u t > 0 – could lead to increased condom usage in the future. Such a scenario would result in positive correlation between u t and pccon t +h for h > 0. OLS would still be consistent, but not unbiased.SOLUTIONS TO COMPUTER EXERCISESC10.1 Let post79 be a dummy variable equal to one for years after 1979, and zero otherwise. Adding post79 to equation 10.15) gives3t i= 1.30 + .608 inf t+ .363 def t+ 1.56 post79t(0.43) (.076) (.120) (0.51)n = 56, R2 = .664, 2R = .644.The coefficient on post79 is statistically significant (t statistic≈ 3.06) and economically large: accounting for inflation and deficits, i3 was about 1.56 points higher on average in years after 1979. The coefficient on def falls once post79 is included in the regression.C10.2 (i) Adding a linear time trend to (10.22) giveslog()chnimp= -2.37 -.686 log(chempi) + .466 log(gas) + .078 log(rtwex)(20.78) (1.240) (.876) (.472)+ .090 befile6+ .097 affile6- .351 afdec6+ .013 t(.251) (.257) (.282) (.004) n = 131, R2 = .362, 2R = .325.Only the trend is statistically significant. In fact, in addition to the time trend, which has a t statistic over three, only afdec6 has a t statistic bigger than one in absolute value. Accounting for a linear trend has important effects on the estimates.(ii) The F statistic for joint significance of all variables except the trend and intercept, of course) is about .54. The df in the F distribution are 6 and 123. The p-value is about .78, and so the explanatory variables other than the time trend are jointly very insignificant. We would have to conclude that once a positive linear trend is allowed for, nothing else helps to explainlog(chnimp). This is a problem for the original event study analysis.(iii) Nothing of importance changes. In fact, the p-value for the test of joint significance of all variables except the trend and monthly dummies is about .79. The 11 monthly dummies themselves are not jointly significant: p-value≈ .59.121C10.3 Adding log(prgnp) to equation (10.38) givesprepop= -6.66 - .212 log(mincov t) + .486 log(usgnp t) + .285 log(prgnp t)log()t(1.26) (.040) (.222) (.080)-.027 t(.005)n = 38, R2 = .889, 2R = .876.The coefficient on log(prgnp t) is very statistically significant (t statistic≈ 3.56). Because the dependent and independent variable are in logs, the estimated elasticity of prepop with respect to prgnp is .285. Including log(prgnp) actually increases the size of the minimum wage effect: the estimated elasticity of prepop with respect to mincov is now -.212, as compared with -.169 in equation (10.38).C10.4 If we run the regression of gfr t on pe t, (pe t-1–pe t), (pe t-2–pe t), ww2t, and pill t, the coefficient and standard error on pe t are, rounded to four decimal places, .1007 and .0298, respectively. When rounded to three decimal places we obtain .101 and .030, as reported in the text.C10.5 (i) The coefficient on the time trend in the regression of log(uclms) on a linear time trend and 11 monthly dummy variables is about -.0139 (se≈ .0012), which implies that monthly unemployment claims fell by about 1.4% per month on average. The trend is very significant. There is also very strong seasonality in unemployment claims, with 6 of the 11 monthly dummy variables having absolute t statistics above 2. The F statistic for joint significance of the 11 monthly dummies yields p-value≈ .0009.(ii) When ez is added to the regression, its coefficient is about -.508 (se≈ .146). Because this estimate is so large in magnitude, we use equation (7.10): unemployment claims are estimated to fall 100[1 – exp(-.508)] ≈ 39.8% after enterprise zone designation.(iii) We must assume that around the time of EZ designation there were not other external factors that caused a shift down in the trend of log(uclms). We have controlled for a time trend and seasonality, but this may not be enough.C10.6 (i) The regression of gfr t on a quadratic in time givesˆgfr= 107.06 + .072 t- .0080 t2t(6.05) (.382) (.0051)n = 72, R2 = .314.Although t and t2 are individually insignificant, they are jointly very significant (p-value≈ .0000).122。

第14章高级面板数据方法14.1复习笔记考点一:固定效应估计法★★★★★1.固定效应变换固定效应变换又称组内变换,考虑仅有一个解释变量的模型:对每个i,有y it =β1x it +a i +u it ,t=1,2,…,T对每个i 求方程在时间上的平均,便得到_y i =β1_x i +a i +_u i 其中,11T it t y T y-==∑(关于时间的均值)。

因为a i 在不同时间固定不变,故它会在原模型和均值模型中都出现,如果对于每个t,两式相减,便得到y it -_y i =β1(x it -_x i )+u it -_u i ,t=1,2,…,T或1 12it it it y x u ,t ,,,T=+=&&&&&&L β其中,it it i y y y =-&&是y 的除时间均值数据;对it x &&和it u &&的解释也类似。

方程的要点在于,非观测效应a i 已随之消失,从而可以使用混合OLS 去估计式1 12it it it y x u ,t ,,,T =+=&&&&&&L β。

上式的混合OLS 估计量被称为固定效应估计量或组内估计量。

组间估计量可以从横截面方程_y i =β1_x i +a i +_u i 的OLS 估计量而得到,即同时使用y 和x的时间平均值做一个横截面回归。

如果a i与_x i相关,估计量是有偏误的。

而如果认为a i 与x it无关,则使用随机效应估计量要更好。

组间估计量忽视了变量如何随着时间而变化。

在方程中添加更多解释变量不会引起什么变化。

2.固定效应模型(1)无偏性原始的非固定效应模型,只要让每一个变量都减去时间均值数据,即可得到固定效应模型。

固定效应模型的无偏性是建立在严格外生性的假定下的,所以FE模型需要假定特异误差u it应与所有时期的每个解释变量都无关。

第6章 多元回归分析:深入专题6.1 复习笔记一、数据的测度单位对OLS 统计量的影响 1.数据的测度单位对OLS 统计量无实质性影响当对变量重新测度时,系数、标准误、置信区间、t 统计量和F 统计量改变的方式,都不影响所有被测度的影响和检验结果。

怎样度量数据通常只起到非实质性的作用,比如说,减少所估计系数中小数点后零的个数等。

通过对度量单位明智的选择,可以在不做任何本质改变的情况下,改进所估计方程的形象。

对任何一个x i ,当它在回归中以log (x i )出现时,改变其度量单位也只能影响到截距。

这与对百分比变化和(特别是)弹性的了解相对应:它们不会随着y 或x i 度量单位的变化而变化。

2.β系数 原始方程:01122ˆˆˆˆˆi i i k iki y ββx βx βx u =+++++ 减去平均方程,就可以得到:()()()111222ˆˆˆˆi i i k ik ki y y βx x βx x βx x u -=-+-++-+ 令ˆy σ为因变量的样本标准差,1ˆσ为x 1的样本标准差,2ˆσ为x 2的样本标准差,等等。

然后经过简单的运算就可以得到方程:()()()()()()11111ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ//////i y y i k y k ik k y i y y y σσσβx x σσσβx x σuσ⎡⎤⎡⎤-=-++-+⎣⎦⎣⎦每个变量都用其z 得分而被标准化,这就得到一些新的斜率参数。

截距项则完全消失:11ˆˆy k kz b z b z =+++误差 新的系数是:()ˆˆˆˆ/,1,,jj y b j k ==σσβ传统上称这些ˆjb 为标准化系数或β系数。

以标准差为单位,由于它使得回归元的度量单位无关紧要,所以这个方程把所有解释变量都放到相同的地位上。

在一个标准的OLS 方程中,不可能只看不同系数的大小,也不可能断定具有最大系数的解释变量就“最重要”。

通过改变x i 的度量单位,可以任意改变系数的大小。

计量经济学导论(伍德里奇)第二章课后作业.txt明骚易躲,暗贱难防。

佛祖曰:你俩就是大傻B!当白天又一次把黑夜按翻在床上的时候,太阳就出生了*用STATA做的*文件位置:"E:\teaching*做do文件doeditcd "E:\teaching"*练习2.3 录入8名学生的ACT分数和GPA(平均积分点)input id GPA ACT1 2.8 212 3.4 243 3.0 264 3.5 275 3.6 296 3.0 257 2.7 258 3.7 30endsave zhangwenwen*回归分析reg GPA ACT,r*方程的斜率为 0.1021978,截距为 0.5681319.display _b[_cons]+_b[ACT]*20*当ACT=20时,GPA的预测值为 2.6120879.*练习2.4use BWGHT.dta , clearreg bwght cigs , rdisplay _b[_cons]+_b[cigs]*0*当吸烟数为0时,婴儿出生时的体重预测值为119.7719盎司。

display _b[_cons]+_b[cigs]*20*当吸烟数为0时,婴儿出生时的体重预测值为109.4965盎司。

*bwght=119.77-0.514cigs 从这个回归中可以得到婴儿出生体重和母亲吸烟习惯之间的关系.*母亲在怀孕期间平均每天的吸烟数增加一个单位,婴儿的体重下降0.514盎司。

*练习2.10use 401K.DTA,clearsum*计划样中平均参与率是87.36291,平均匹配率是0.7315124*下面做回归分析regress prate mrate,robust*Estimated slope(样本斜率) = 5.861079*Estimated intercept(截距) = 83.07546,*Estimated regression line: prate = 83.075+5.861mrate*样本容量是1534,R-平方=0.0747*如果mrate=0,那么参与率就是83.0754%。

CHAPTER 2TEACHING NOTESThis is the chapter where I expect students to follow most, if not all, of the algebraic derivations. In class I like to derive at least the unbiasedness of the OLS slope coefficient, and usually I derive the variance. At a minimum, I talk about the factors affecting the variance. To simplify the notation, after I emphasize the assumptions in the population model, and assume random sampling, I just condition on the values of the explanatory variables in the sample. Technically, this is justified by random sampling because, for example, E(u i|x1,x2,…,x n) = E(u i|x i) by independent sampling. I find that students are able to focus on the key assumption SLR.4 and subsequently take my word about how conditioning on the independent variables in the sample is harmless. (If you prefer, the appendix to Chapter 3 does the conditioning argument carefully.) Because statistical inference is no more difficult in multiple regression than in simple regression, I postpone inference until Chapter 4. (This reduces redundancy and allows you to focus on the interpretive differences between simple and multiple regression.)You might notice how, compared with most other texts, I use relatively few assumptions to derive the unbiasedness of the OLS slope estimator, followed by the formula for its variance. This is because I do not introduce redundant or unnecessary assumptions. For example, once SLR.4 is assumed, nothing further about the relationship between u and x is needed to obtain the unbiasedness of OLS under random sampling.Incidentally, one of the uncomfortable facts about finite-sample analysis is that there is a difference between an estimator that is unbiased conditional on the outcome of the covariates and one that is unconditionally unbiased. If the distribution of the x i is such that they can all equal the same value with positive probability – as is the case with discreteness in the distribution –then the unconditional expectation does not really exist. Or, if it is made to exist then the estimator is not unbiased. I do not try to explain these subtleties in an introductory course, but I have had instructors ask me about the difference.SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS2.1 (i) Income, age, and family background (such as number of siblings) are just a fewpossibilities. It seems that each of these could be correlated with years of education. (Income and education are probably positively correlated; age and education may be negatively correlated because women in more recent cohorts have, on average, more education; and number of siblings and education are probably negatively correlated.)(ii) Not if the factors we listed in part (i) are correlated with educ . Because we would like to hold these factors fixed, they are part of the error term. But if u is correlated with educ then E(u|educ ) ≠ 0, and so SLR.4 fails.2.2 In the equation y = β0 + β1x + u , add and subtract α0 from the right hand side to get y = (α0 + β0) + β1x + (u - α0). Call the new error e = u - α0, so that E(e ) = 0. The new intercept is α0 + β0, but the slope is still β1.2.3 (i) Let y i = GPA i , x i = ACT i , and n = 8. Then x = 25.875, y =3.2125, 1ni =∑(x i – x )(y i – y ) =5.8125, and 1ni =∑(x i – x )2 = 56.875. From equation (2.9), we obtain the slope as 1ˆβ= 5.8125/56.875 ≈ .1022, rounded to four places after the decimal. From (2.17), 0ˆβ = y – 1ˆβx ≈ 3.2125 – (.1022)25.875 ≈ .5681. So we can writeGPA = .5681 + .1022 ACTn = 8.The intercept does not have a useful interpretation because ACT is not close to zero for the population of interest. If ACT is 5 points higher, GPA increases by .1022(5) = .511.(ii) The fitted values and residuals — rounded to four decimal places — are given along with the observation number i and GPA in the following table:You can verify that the residuals, as reported in the table, sum to -.0002, which is pretty close to zero given the inherent rounding error.(iii) When ACT = 20, GPA = .5681 + .1022(20) ≈ 2.61.(iv) The sum of squared residuals,21ˆni i u=∑, is about .4347 (rounded to four decimal places), and the total sum of squares,1ni =∑(y i – y )2, is about 1.0288. So the R -squared from the regressionisR 2 = 1 – SSR/SST ≈ 1 – (.4347/1.0288) ≈ .577.Therefore, about 57.7% of the variation in GPA is explained by ACT in this small sample of students.2.4 (i) When cigs = 0, predicted birth weight is 119.77 ounces. When cigs = 20, bwght = 109.49. This is about an 8.6% drop.(ii) Not necessarily. There are many other factors that can affect birth weight, particularly overall health of the mother and quality of prenatal care. These could be correlated withcigarette smoking during birth. Also, something such as caffeine consumption can affect birth weight, and might also be correlated with cigarette smoking.(iii) If we want a predicted bwght of 125, then cigs = (125 – 119.77)/( –.524) ≈–10.18, or about –10 cigarettes! This is nonsense, of course, and it shows what happens when we are trying to predict something as complicated as birth weight with only a single explanatory variable. The largest predicted birth weight is necessarily 119.77. Yet almost 700 of the births in the sample had a birth weight higher than 119.77.(iv) 1,176 out of 1,388 women did not smoke while pregnant, or about 84.7%. Because we are using only cigs to explain birth weight, we have only one predicted birth weight at cigs = 0. The predicted birth weight is necessarily roughly in the middle of the observed birth weights at cigs = 0, and so we will under predict high birth rates.2.5 (i) The intercept implies that when inc = 0, cons is predicted to be negative $124.84. This, of course, cannot be true, and reflects that fact that this consumption function might be a poor predictor of consumption at very low-income levels. On the other hand, on an annual basis, $124.84 is not so far from zero.(ii) Just plug 30,000 into the equation: cons = –124.84 + .853(30,000) = 25,465.16 dollars.(iii) The MPC and the APC are shown in the following graph. Even though the intercept is negative, the smallest APC in the sample is positive. The graph starts at an annual income level of $1,000 (in 1970 dollars).increases housing prices.(ii) If the city chose to locate the incinerator in an area away from more expensive neighborhoods, then log(dist) is positively correlated with housing quality. This would violate SLR.4, and OLS estimation is biased.(iii) Size of the house, number of bathrooms, size of the lot, age of the home, and quality of the neighborhood (including school quality), are just a handful of factors. As mentioned in part (ii), these could certainly be correlated with dist [and log(dist )].2.7 (i) When we condition on incbecomes a constant. So E(u |inc⋅e |inc) = ⋅E(e |inc⋅0 because E(e |inc ) = E(e ) = 0.(ii) Again, when we condition on incbecomes a constant. So Var(u |inc⋅e |inc2Var(e |inc ) = 2e σinc because Var(e |inc ) = 2e σ.(iii) Families with low incomes do not have much discretion about spending; typically, a low-income family must spend on food, clothing, housing, and other necessities. Higher income people have more discretion, and some might choose more consumption while others more saving. This discretion suggests wider variability in saving among higher income families.2.8 (i) From equation (2.66),1β = 1n i i i x y =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ / 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑.Plugging in y i = β0 + β1x i + u i gives1β = 011()n i i i i x x u ββ=⎛⎫++ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑.After standard algebra, the numerator can be written as201111in n ni i i i i i x x x u ββ===++∑∑∑.Putting this over the denominator shows we can write 1β as1β = β01n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ + β1 + 1n i i i x u =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫⎪⎝⎭∑.Conditional on the x i , we haveE(1β) = β01n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫⎪⎝⎭∑ + β1because E(u i ) = 0 for all i . Therefore, the bias in 1β is given by the first term in this equation. This bias is obviously zero when β0 = 0. It is also zero when 1ni i x =∑ = 0, which is the same asx = 0. In the latter case, regression through the origin is identical to regression with an intercept. (ii) From the last expression for 1βin part (i) we have, conditional on the x i ,Var(1β) = 221n i i x -=⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑Var 1n i i i x u =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ = 221n i i x -=⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑21Var()n i i i x u =⎛⎫⎪⎝⎭∑= 221n i i x -=⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑221n i i x σ=⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ = 2σ/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑.(iii) From (2.57), Var(1ˆβ) = σ2/21()n i i x x =⎛⎫- ⎪⎝⎭∑. From the hint, 21n i i x =∑ ≥ 21()ni i x x =-∑, and so Var(1β) ≤ Var(1ˆβ). A more direct way to see this is to write 21()ni i x x =-∑ = 221()ni i x n x =-∑, which is less than 21ni i x =∑ unless x = 0.(iv) For a given sample size, the bias in 1β increases as x increases (holding the sum of the2ix fixed). But as x increases, the variance of 1ˆβincreases relative to Var(1β). The bias in 1β is also small when 0β is small. Therefore, whether we prefer 1β or 1ˆβ on a mean squared error basis depends on the sizes of 0β, x , and n (in addition to the size of 21ni i x =∑).2.9 (i) We follow the hint, noting that 1c y = 1c y (the sample average of 1i c y is c 1 times the sample average of y i ) and 2c x = 2c x . When we regress c 1y i on c 2x i (including an intercept) we use equation (2.19) to obtain the slope:2211121112222221111112221()()()()()()()()ˆ.()n ni iiii i nnii i i niii nii c x c x c y c y c c x x y y c x c x cx x x x y y c c c c x x ββ======----==----=⋅=-∑∑∑∑∑∑From (2.17), we obtain the intercept as 0β = (c 1y ) – 1β(c 2x ) = (c 1y ) – [(c 1/c 2)1ˆβ](c 2x ) = c 1(y – 1ˆβx ) = c 10ˆβ) because the intercept from regressing y i on x i is (y – 1ˆβx ).(ii) We use the same approach from part (i) along with the fact that 1()c y + = c 1 + y and2()c x + = c 2 + x . Therefore, 11()()i c y c y +-+ = (c 1 + y i ) – (c 1 + y ) = y i – y and (c 2 + x i ) – 2()c x + = x i – x . So c 1 and c 2 entirely drop out of the slope formula for the regression of (c 1 + y i )on (c 2 + x i ), and 1β = 1ˆβ. The intercept is 0β = 1()c y + – 1β2()c x + = (c 1 + y ) – 1ˆβ(c 2 + x ) = (1ˆy x β-) + c 1 – c 21ˆβ = 0ˆβ + c 1 – c 21ˆβ, which is what we wanted to show.(iii) We can simply apply part (ii) because 11log()log()log()i i c y c y =+. In other words, replace c 1 with log(c 1), y i with log(y i ), and set c 2 = 0.(iv) Again, we can apply part (ii) with c 1 = 0 and replacing c 2 with log(c 2) and x i with log(x i ). If 01垐 and ββ are the original intercept and slope, then 11ˆββ= and 0021垐log()c βββ=-.2.10 (i) This derivation is essentially done in equation (2.52), once (1/SST )x is brought inside the summation (which is valid because SST x does not depend on i ). Then, just define/SST i i x w d =.(ii) Because 111垐Cov(,)E[()] ,u u βββ=- we show that the latter is zero. But, from part (i),()1111ˆE[()] =E E().nn i i i i i i u wu u w u u ββ==⎡⎤-=⎢⎥⎣⎦∑∑ Because the i u are pairwise uncorrelated (they are independent), 22E()E(/)/i i u u u n n σ== (because E()0, i h u u i h =≠). Therefore,(iii) The formula for the OLS intercept is 0垐y x ββ=- and, plugging in 01y x u ββ=++ gives 01111垐?()().x u x u x βββββββ=++-=+--(iv) Because 1ˆ and u β are uncorrelated, 222222201垐Var()Var()Var()/(/SST )//SST x x u x n x n x ββσσσσ=+=+=+,which is what we wanted to show.(v) Using the hint and substitution gives ()220ˆVar()[SST /]/SST x xn x βσ=+ ()()2122221211/SST /SST .nni x i x i i n x x x n x σσ--==⎡⎤=-+=⎢⎥⎣⎦∑∑22111E()(/)(/)0.n n ni i i i i i i w u u w n n w σσ======∑∑∑2.11 (i) We would want to randomly assign the number of hours in the preparation course so that hours is independent of other factors that affect performance on the SAT. Then, we would collect information on SAT score for each student in the experiment, yielding a data set{(,):1,...,}i i sat hours i n =, where n is the number of students we can afford to have in the study. From equation (2.7), we should try to get as much variation in i hours as is feasible.(ii) Here are three factors: innate ability, family income, and general health on the day of the exam. If we think students with higher native intelligence think they do not need to prepare for the SAT, then ability and hours will be negatively correlated. Family income would probably be positively correlated with hours , because higher income families can more easily affordpreparation courses. Ruling out chronic health problems, health on the day of the exam should be roughly uncorrelated with hours spent in a preparation course.(iii) If preparation courses are effective,1β should be positive: other factors equal, an increase in hours should increase sat .(iv) The intercept, 0β, has a useful interpretation in this example: because E(u ) = 0, 0β is the average SAT score for students in the population with hours = 0.2.12 (i) I will show the result without using calculus. Let y ̅ be the sample average of the y i and write221122001112200112201()[()()]()2()()()()2()()()()()n niii i nnni i i i i nni i i i ni i y b y y y b y y y y y b y b y y y b y y n y b y y n y b ========-=-+-=-+--+-=-+--+-=-+-∑∑∑∑∑∑∑∑where we use the fact (see Appendix A) that 1()0ni i y y =-=∑ always. The first term does notdepend on 0b and the second term,20()n y b -, which is nonnegative, is clearly minimized when 0b y =.(ii) If we define i i u y y =-then 11()nni i i i u y y ===-∑∑and we already used the fact that this sumis zero in the proof in part (i).SOLUTIONS TO COMPUTER EXERCISESC2.1 (i) The average prate is about 87.36 and the average mrate is about .732.(ii) The estimated equation isprate= 83.05 + 5.86 mraten = 1,534, R2 = .075.(iii) The intercept implies that, even if mrate = 0, the predicted participation rate is 83.05 percent. The coefficient on mrate implies that a one-dollar increase in the match rate – a fairly large increase – is estimated to increase prate by 5.86 percentage points. This assumes, of course, that this change prate is possible (if, say, prate is already at 98, this interpretation makes no sense).(iv) If we plug mrate = 3.5 into the equation we get ˆprate= 83.05 + 5.86(3.5) = 103.59. This is impossible, as we can have at most a 100 percent participation rate. This illustrates that, especially when dependent variables are bounded, a simple regression model can give strange predictions for extreme values of the independent variable. (In the sample of 1,534 firms, only 34 have mrate≥ 3.5.)(v) mrate explains about 7.5% of the variation in prate. This is not much, and suggests that many other factors influence 401(k) plan participation rates.C2.2 (i) Average salary is about 865.864, which means $865,864 because salary is in thousands of dollars. Average ceoten is about 7.95.(ii) There are five CEOs with ceoten = 0. The longest tenure is 37 years.(iii) The estimated equation issalary= 6.51 + .0097 ceotenlog()n = 177, R2 = .013.We obtain the approximate percentage change in salary given ∆ceoten = 1 by multiplying the coefficient on ceoten by 100, 100(.0097) = .97%. Therefore, one more year as CEO is predicted to increase salary by almost 1%.C2.3 (i) The estimated equation issleep= 3,586.4 – .151 totwrkn = 706, R2 = .103.The intercept implies that the estimated amount of sleep per week for someone who does not work is 3,586.4 minutes, or about 59.77 hours. This comes to about 8.5 hours per night.(ii) If someone works two more hours per week then ∆totwrk = 120 (because totwrk ismeasured in minutes), and so sleep ∆= –.151(120) = –18.12 minutes. This is only a few minutes a night. If someone were to work one more hour on each of five working days, sleep ∆= –.151(300) = –45.3 minutes, or about five minutes a night.C2.4 (i) Average salary is about $957.95 and average IQ is about 101.28. The sample standard deviation of IQ is about 15.05, which is pretty close to the population value of 15.(ii) This calls for a level-level model: wage = 116.99 + 8.30 IQn = 935, R 2 = .096.An increase in IQ of 15 increases predicted monthly salary by 8.30(15) = $124.50 (in 1980 dollars). IQ score does not even explain 10% of the variation in wage .(iii) This calls for a log-level model:log()wage = 5.89 + .0088 IQ n = 935, R 2 = .099.If ∆IQ = 15 then log()wage ∆ = .0088(15) = .132, which is the (approximate) proportionate change in predicted wage. The percentage increase is therefore approximately 13.2.C2.5 (i) The constant elasticity model is a log-log model:log(rd ) = 0β + 1βlog(sales ) + u ,where 1β is the elasticity of rd with respect to sales .(ii) The estimated equation is log()rd = –4.105 + 1.076 log(sales )n = 32, R 2 = .910.The estimated elasticity of rd with respect to sales is 1.076, which is just above one. A one percent increase in sales is estimated to increase rd by about 1.08%.C2.6 (i) It seems plausible that another dollar of spending has a larger effect for low-spending schools than for high-spending schools. At low-spending schools, more money can go toward purchasing more books, computers, and for hiring better qualified teachers. At high levels of spending, we would expend little, if any, effect because the high-spending schools already have high-quality teachers, nice facilities, plenty of books, and so on.(ii) If we take changes, as usual, we obtain1110log()(/100)(%),math expend expend ββ∆=∆≈∆just as in the second row of Table 2.3. So, if %10,expend ∆=110/10.math β∆=(iii) The regression results are21069.34 11.16 log()408, .0297math expend n R =-+==(iv) If expend increases by 10 percent, 10math increases by about 1.1 percentage points. This is not a huge effect, but it is not trivial for low-spending schools, where a 10 percent increase in spending might be a fairly small dollar amount.(v) In this data set, the largest value of math10 is 66.7, which is not especially close to 100. In fact, the largest fitted values is only about 30.2.C2.7 (i) The average gift is about 7.44 Dutch guilders. Out of 4,268 respondents, 2,561 did not give a gift, or about 60 percent.(ii) The average mailings per year is about 2.05. The minimum value is .25 (which presumably means that someone has been on the mailing list for at least four years) and the maximum value is 3.5.(iii) The estimated equation is22.01 2.65 4,268, .0138gift mailsyear n R =+==(iv) The slope coefficient from part (iii) means that each mailing per year is associated with – perhaps even “causes” – an estimated 2.65 additional guilders, on average. Therefore, if each mailing costs one guilder, the expected profit from each mailing is estimated to be 1.65 guilders. This is only the average, however. Some mailings generate no contributions, or a contribution less than the mailing cost; other mailings generated much more than the mailing cost.(v) Because the smallest mailsyear in the sample is .25, the smallest predicted value of gifts is 2.01 + 2.65(.25) ≈ 2.67. Even if we look at the overall population, where some people have received no mailings, the smallest predicted value is about two. So, with this estimated equation, we never predict zero charitable gifts.C2.8 There is no “correct” answer to this question because all answers depend on how the random outcomes are generated. I used Stata 11 and, before generating the outcomes on the i x , I set the seed to the value 123. I reset the seed to 123 to generate the outcomes on the i u . Specifically, to answer parts (i) through (v), I used the sequence of commandsset obs 500set seed 123gen x = 10*runiform()sum xset seed 123gen u = 6*rnormal()sum ugen y = 1 + 2*x + ureg y xpredict uh, residgen x_uh = x*uhsum uh x_uhgen x_u = x*usum u x_u(i) The sample mean of the i x is about 4.912 with a sample standard deviation of about 2.874.(ii) The sample average of the i u is about .221, which is pretty far from zero. We do not get zero because this is just a sample of 500 from a population with a zero mean. The current sample is “unlucky” in the sense that the sample average is far from the population average. The sample standard deviation is about 5.768, which is nontrivially below 6, the population value.(iii) After generating the data on i y and running the regression, I get, rounding to three decimal places,0ˆ 1.862β= and 1ˆ 1.870β= The population values are 1 and 2, respectively. Thus, the estimated intercept based on this sample of data is well above the population value. The estimated slope is somewhat below the population value, 2. When we sample from a population our estimates contain sampling error; that is why the estimates differ from the population values.(iv) When I use the command sum uh x_uh and multiply by 500 I get, using scientific notation, sums equal to 4.181e-06 and .00003776, respectively. These are zero for practical purposes, and differ from zero only due to rounding inherent in the machine imprecision (which is unimportant).(v) We already computed the sample average of the i u in part (ii). When we multiply by 500 the sample average is about 110.74. The sum of i i x u is about 6.46. Neither is close to zero, and nothing says they should be particularly close.(vi) For this part I set the seed to 789. The sample average and standard deviation of the i x are about 5.030 and 2.913; those for the i u are about .077- and 5.979. When I generated the i y and run the regression I get0ˆ.701β= and 1ˆ 2.044β= These are different from those in part (iii) because they are obtained from a different random sample. Here, for both the intercept and slope, we get estimates that are much closer to the population values. Of course, in practice we would never know that.。

计量经济学导论第六版课后答案知识伍德里奇第一章:计量经济学介绍1. 为什么需要计量经济学?计量经济学的主要目标是提供一种科学的方法来解决经济问题。

经济学家需要使用数据来验证经济理论的有效性,并预测经济变量的发展趋势。

计量经济学提供了一种框架,使得经济学家能够使用数学和统计方法来分析经济问题。

2. 计量经济学的基本概念•因果推断:计量经济学的核心是通过观察数据来推断出变量之间的因果关系。

通过使用统计方法,我们可以分析出某个变量对另一个变量的影响。

•数据类型:计量经济学研究的数据可以是时间序列数据或截面数据。

时间序列数据是沿着时间轴观测到的数据,而截面数据是在某一时间点上观测到的数据。

•数据偏差:在计量经济学中,数据偏差是指由于样本选择问题、观测误差等原因导致数据与真实值之间的差异。

3. 计量经济学的方法计量经济学使用了许多统计和经济学方法来分析数据。

以下是一些常用的计量经济学方法:•最小二乘法(OLS):在计量经济学中,最小二乘法是一种常用的回归方法。

它通过最小化观测值和预测值之间的平方差来估计未知参数。

•时间序列分析:时间序列分析是通过对时间序列数据进行模型化和预测来研究经济变量的变化趋势。

•面板数据分析:面板数据是同时包含时间序列和截面数据的数据集。

面板数据分析可以用于研究个体和时间的变化,以及它们之间的关系。

4. 计量经济学应用领域计量经济学广泛应用于经济学研究和实践中的各个领域。

以下是一些计量经济学的应用领域:•劳动经济学:计量经济学可以用来研究劳动力市场的供求关系、工资决定因素等问题。

•金融经济学:计量经济学可以用来研究证券价格、金融市场的波动等问题。

•产业组织经济学:计量经济学可以用来研究市场竞争、垄断力量等问题。

•发展经济学:计量经济学可以用来研究发展中国家的经济增长、贫困问题等。

第二章:统计学回顾1. 统计学基本概念•总体和样本:总体是指我们想要研究的全部个体或事物的集合,而样本是从总体中选取的一部分个体或事物。

第三篇高级专题第13章跨时横截面的混合:简单面板数据方法13.1复习笔记考点一:跨时独立横截面的混合★★★★★1.独立混合横截面数据的定义独立混合横截面数据是指在不同时点从一个大总体中随机抽样得到的随机样本。

这种数据的重要特征在于:都是由独立抽取的观测所构成的。

在保持其他条件不变时,该数据排除了不同观测误差项的相关性。

区别于单独的随机样本,当在不同时点上进行抽样时,样本的性质可能与时间相关,从而导致观测点不再是同分布的。

2.使用独立混合横截面的理由(见表13-1)表13-1使用独立混合横截面的理由3.对跨时结构性变化的邹至庄检验(1)用邹至庄检验来检验多元回归函数在两组数据之间是否存在差别(见表13-2)表13-2用邹至庄检验来检验多元回归函数在两组数据之间是否存在差别(2)对多个时期计算邹至庄检验统计量的办法①使用所有时期虚拟变量与一个(或几个、所有)解释变量的交互项,并检验这些交互项的联合显著性,一般总能检验斜率系数的恒定性。

②做一个容许不同时期有不同截距的混合回归来估计约束模型,得到SSR r。

然后,对T个时期都分别做一个回归,并得到相应的残差平方和,有:SSR ur=SSR1+SSR2+…+SSR T。

若有k个解释变量(不包括截距和时期虚拟变量)和T个时期,则需检验(T-1)k个约束。

而无约束模型中有T+Tk个待估计参数。

所以,F检验的df为(T-1)k和n-T-Tk,其中n为总观测次数。

F统计量计算公式为:[(SSR r-SSR ur)/SSR ur][(n-T-Tk)/(Tk-k)]。

但该检验不能对异方差性保持稳健,为了得到异方差-稳健的检验,必须构造交互项并做一个混合回归。

4.利用混合横截面作政策分析(1)自然实验与真实实验当某些外生事件改变了个人、家庭、企业或城市运行的环境时,便产生了自然实验(准实验)。

一个自然实验总有一个不受政策变化影响的对照组和一个受政策变化影响的处理组。

自然实验中,政策发生后才能确定处理组和对照组。

第二篇时间序列数据的回归分析

第10章时间序列数据的基本回归分析

10.1 复习笔记

考点一:时间序列数据★★

1.时间序列数据与横截面数据的区别

(1)时间序列数据集是按照时间顺序排列。

(2)时间序列数据与横截面数据被视为随机结果的原因不同。

(3)一个时间序列过程的所有可能的实现集,便相当于横截面分析中的总体。

时间序列数据集的样本容量就是所观察变量的时期数。

2.时间序列模型的主要类型(见表10-1)

表10-1 时间序列模型的主要类型

考点二:经典假设下OLS的有限样本性质★★★★

1.高斯-马尔可夫定理假设(见表10-2)

表10-2 高斯-马尔可夫定理假设

2.OLS估计量的性质与高斯-马尔可夫定理(见表10-3)

表10-3 OLS估计量的性质与高斯-马尔可夫定理

3.经典线性模型假定下的推断

(1)假定TS.6(正态性)

假定误差u t独立于X,且具有独立同分布Normal(0,σ2)。

该假定蕴涵了假定TS.3、TS.4和TS.5,但它更强,因为它还假定了独立性和正态性。

(2)定理10.5(正态抽样分布)

在时间序列的CLM假定TS.1~TS.6下,以X为条件,OLS估计量遵循正态分布。

而且,在虚拟假设下,每个t统计量服从t分布,F统计量服从F分布,通常构造的置信区间也是确当的。

定理10.5意味着,当假定TS.1~TS.6成立时,横截面回归估计与推断的全部结论都可以直接应用到时间序列回归中。

这样t统计量可以用来检验个别解释变量的统计显著性,F

统计量可以用来检验联合显著性。

考点三:时间序列的应用★★★★★

1.函数形式、虚拟变量

除了常见的线性函数形式,其他函数形式也可以应用于时间序列中。

最重要的是自然对数,在应用研究中经常出现具有恒定百分比效应的时间序列回归。

虚拟变量也可以应用在时间序列的回归中,如某一期的数据出现系统差别时,可以采用虚拟变量的形式。

2.趋势和季节性

(1)描述有趋势的时间序列的方法(见表10-4)

表10-4 描述有趋势的时间序列的方法

(2)回归中的趋势变量

由于某些无法观测的趋势因素可能同时影响被解释变量与解释变量,被解释变量与解释变量均随时间变化而变化,容易得到被解释变量与解释变量之间趋势变量的关系,而非真正的相关关系,导致了伪回归。

而在模型中加入时间趋势变量可以起到去趋势的作用,消除伪回归。

在回归模型中引进时间趋势,相当于在回归分析中,在使用原始数据之前,便将它们除趋势。

将被解释变量和解释变量及时间趋势t进行回归,便得到拟合方程。

原模型中解释变量的系数估计可通过如下步骤得到:

①将被解释变量y t和解释变量x tj分别对常数项和时间趋势t回归,并记录各回归残差;

②将上一步中得到的被解释变量y t回归得到的残差对解释变量x tj回归得到的残差进行回归(模型中不需要包含截距,但是若保留截距,那么估计出来的截距也是零)得到原模型中解。