Report2

- 格式:docx

- 大小:40.71 KB

- 文档页数:3

一、选择题1 [单选题] 把用高级语言写的程序转换为可执行程序,要经过的过程叫做二、基本操作题21 [简答题]在考生文件夹下QI\XI文件夹中建立一个新文件夹THOUT。

参考解析:新建文件夹①打开考生文件夹下QI\XI文件夹;②选择【文件】|【新建】|【文件夹】命令,或单击鼠标右键,弹出快捷菜单,选择【新建】|【文件夹】命令,即可生成新的文件夹,此时文件(文件夹)的名字处呈现蓝色可编辑状态,编辑名称为题目指定的名称THOUT。

22 [简答题]将考生文件夹下PENG文件夹中的文件BLUE.WPS移动到考生文件夹下ZHU 文件夹中,并将该文件改名为RED.WPS。

参考解析:移动文件和文件命名①打开考生文件夹下PENG文件夹,选中BLUE.WPS文件;②选择【编辑】|【剪切】命令,或按快捷键Ctrl+X;③打开考生文件夹下ZHU文件夹;④选择【编辑】|【粘贴】命令,或按快捷键Ctrl+V;⑤选中移动来的文件;⑥按F2键,此时文件(文件夹)的名字处呈现蓝色可编辑状态,编辑名称为题目指定的名称RED.WPS。

23 [简答题]在考生文件夹下YE文件夹中建立一个新文件夹PDMA。

参考解析:新建文件夹①打开考生文件夹下YE文件夹;②选择【文件】|【新建】|【文件夹】命令,或单击鼠标右键,弹出快捷菜单,选择【新建】|【文件夹】命令,即可生成新的文件夹,此时文件(文件夹)的名字处呈现蓝色可编辑状态,编辑名称为题目指定的名称PDMA。

24 [简答题]在考生文件夹下分别建立REPORT1和RE—PORT2两个文件夹。

参考解析:新建文件夹①打开考生文件夹下;②选择【文件】|【新建】|【文件夹】命令,或右击,弹出快捷菜单,选择【新建】|【文件夹】命令,即可生成新的文件夹,此时文件(文件夹)的名字处呈现蓝色可编辑状态。

编辑名称为题目指定的名称REPORT1和REPORT2。

25 [简答题]将考生文件夹下ABS文件夹中的LOCK.FOR文件复制到同一文件夹中,文件命名为FUZH1.FOR。

report的用法总结大全大家都知道report的意思。

那你们想知道report用法吗?今天给大家带来了report用法,希望能够帮助到大家,一起来学习吧。

report的用法总结大全report的意思n. 报告,成绩报告单,传闻,流言蜚语vt. vi. 报道,公布,宣告vt. 告发,举报,使报到变形:过去式: reported; 现在分词:reporting; 过去分词:reported;report用法report可以用作名词report用作名词的基本意思是“报告,报道”,表示通过调查作出的官方或正式的说明,通常含有对情况的分析判断,尤指下级对上级或委托机关的报告,在英式英语里也可指学生的“成绩报告单”或雇员的“工作鉴定书”,是可数名词。

report也可作“传闻,谣言”解,是不可数名词,但其前可用不定冠词a修饰。

reports有“流言蜚语,道听途说”的意思。

report还可作“名声,名誉”解,是不可数名词。

report用作名词的用法例句He is reading a report of the state of the roads.他正在看一篇关于道路状况的报告。

I have only reports to go on.我的依据只是谣传而已。

My son got an excellent report last semester.我儿子上学期成绩出色。

report可以用作动词report的基本意思是“报告”,指用口头或书面的形式把事情或意见正式告诉上级或群众。

引申可表示“告发”“举报”“公布,宣布,宣告”“当记者”“报道”“据说”“报到”等。

report用作及物动词时其后可接名词、动名词、that/wh-从句作宾语,也可接以动词不定式或“(to be+) n./adj./adv. ”充当补足语的复合宾语。

用作不及物动词时,常与for, to, on等介词连用。

be reported其后可接形容词、现在分词、动词不定式、过去分词或as短语、介词短语充当宾语补足语。

印度经济时报:中国雇员敢要求老板涨工资[转贴自:中国网点击数:10更新时间:2007-12-18 9:56:31]印度《经济时报》12月14日文章,原题:当你指出问题时,为什么中国的雇员会笑“你可以给我涨工资吗?”这样的问题在印度的公司里几乎是一个禁忌,但在中国却可能经常听见这样的话。

中国的雇员对“互惠互利”很实际——他们对公司有多大贡献,他们就要求多少回报。

中国人办事总是有条不紊。

虽然也可以经常看到印度雇员在公司待很长时间,但中国雇员的关键不同之处在于:他们长时间地呆在公司就是为了完成工作,而不只是做做样子,或者说仅仅因为老板还没离开。

一般情况下,在中国,下属不会向上级提过多的问题,而是踏踏实实地完成分配给他们的任务。

但是,偶尔听听下属的想法也是必不可少的,不要对他们提什么建议、指示,除非他们主动问。

员工很少会去问领导一个问题应该如何解决。

领导应该给出一个具体的解决问题的方法,而不是向员工摆除一堆可供选择的方案。

如果他们能做决定,就不会去找领导。

中国人和印度人一个非常重要的不同点——尤其是在中高级管理层中——就是如何解决问题。

有着语言和分析能力上的优势,人们常常看见印度的经理们花大量的时间,追求“以知识取胜”。

而中国人的策略就是,直接切入正题,尽可能快地找到解决问题的办法。

中国的雇员不会轻易地接受一项工作,除非他们自认为能出色的完成这一任务。

他们会花不少时间去思考自己到底需要什么,而印度人在这方面花的心思比较少。

中国人在这一点上与印度有很大的不同,在印度,我们很少听到员工对老板说“不”。

(雷志华译)据国外媒体报道,诺基亚位于印度清奈(Chennai,即马德拉斯Madras)斯克里伯鲁布德工业园(Sriperumbudur)的制造厂上周遭遇罢工,其员工提出了薪酬诉求。

罢工持续了10小时,直至劳动部出面安排调解。

据当地媒体报道,由于诺基亚工厂管理层提出的薪资方案不被员工接受,罢工从周五早上开始。

约有8000名工人参与了罢工,尽管管理层认为此报道有争议,罢工人数要远远低于此。

Reading Report 2ArticleFor some in China,the aim of travel is to create 15-second videosPerched on cliffs above ariver, Hongyadong is a stilt-house complex in mock-traditional style in the city of Chongqing. Its bars, restaurants and golden neon lights have been a popular draw since it was builtin 2006. Last year the number of visitors surged.The main reason, it seemed, was Hongyadong’s sudden popularity on a social-media app, Douyin, which is used for sharing photographs and 15-secondvideos.Uploading a picture or video from a photogenic spot to sites such as Douyin and Kuaishou is known in China as daka, meaning “punching the card”. The word is also used to refer to the practiceof registering your presence at a location that has already become hot, such as Hongyadong. The aim is not to produce a well-crafted video or beautiful photograph, but simply to show that you have also been to the places that are popular.A subculture has developed of young people who embrace dakaas a lifestyle. So-called daka zu—“daka tribes”— can be found roaming Chongqing and other cities, checking in at as many hot locations as possible within a single day.The daka craze may have practical origins. China’s youngurban professionals have little vacation time. So workers need to make the most of their limited leisure time. Douyin captures the mood with its slogan: “Make every second count.”ViewpointIn recent years, a word “daka”, which means“punching the card” has gone viral.Meanwhile, it contributes to the emergence of Internet popular cities.Every public holiday, these cities will break out a wave of "daka fever". But the aim of this travel is to create 15-second videos or share some photos to WeChat. In this case, I would like to say that the function of “daka” is complex.For these cities, on the one hand, the increase of tourists has brought about positive impacts such as the increase of city popularity and population aggregation, the increase of tertiary industry income such as cultural tourism, and the increase of temporary social jobs; on the other hand, the far overloaded passenger flow has led to poor tourism experience of the people, disorder of urban order, and adverse effects on the protection of ecological and cultural heritage, resulting in public security risks.For those who go to “daka”, on the goo d side, the city that wins praises must have its originality, so people can get a good sense of appreciation. At the same time, sharing the experience of travelling in that city with friends or even strangers can get more attention and improve their charm. On the bad side, the increase of tourist flow in the city will inevitably lead to crowding, and it is possible to see more people than scenery. Moreover, taking a quick look instead of having a excellent and peaceful tour can not make them really feel the beautiful city, but a task. This is no help to the improvement of self-cultural literacy.From my perspective,cities should make more comprehensive management, such as through crowd diversion, closed parks and other ways to ease the pressure of scenic spots. And tourists should also bemore immersed in the beautiful scenery rather than simply taking photos and videos to get attention. Only if everyone of us makes a contribution can we better promote the development of China's tourism.17190113Kaixin Zhu。

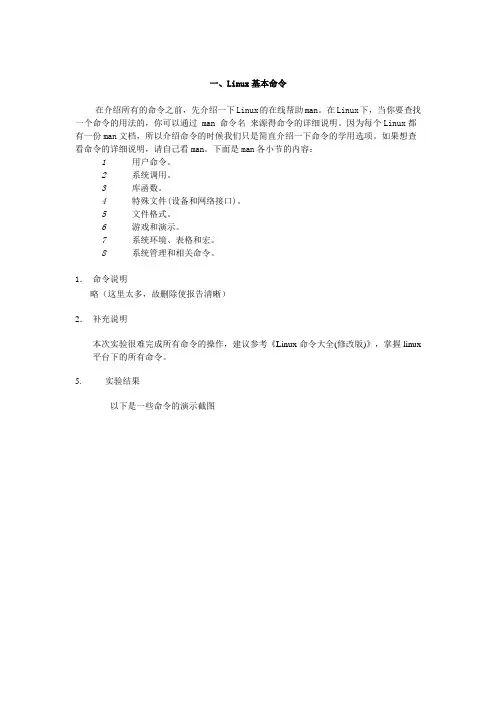

一、Linux基本命令在介绍所有的命令之前,先介绍一下Linux的在线帮助man。

在Linux下,当你要查找一个命令的用法的,你可以通过 man 命令名来源得命令的详细说明。

因为每个Linux都有一份man文档,所以介绍命令的时候我们只是简直介绍一下命令的学用选项。

如果想查看命令的详细说明,请自己看man。

下面是man各小节的内容:1用户命令。

2系统调用。

3库函数。

4特殊文件(设备和网络接口)。

5文件格式。

6游戏和演示。

7系统环境、表格和宏。

8系统管理和相关命令。

1.命令说明略(这里太多,故删除使报告清晰)2.补充说明本次实验很难完成所有命令的操作,建议参考《Linux命令大全(修改版)》,掌握linux 平台下的所有命令。

5.实验结果以下是一些命令的演示截图6.体会对linux'的命令有了一定的了解,使我使用linux系统更加的方便。

为下次shell编程打下了一定的基础。

二、shell编程1.内容:1.知道如何执行shell程序2.在shell脚本中要体现条件控制(如if结构和条件分支)3.在shell脚本中要体现循环(for,while和until循环)4.掌握shell程序的调试2.Shell脚本举例1)赶走一些你不希望进入的用户while truedokill -9 $(ps -aux |grep bigman | awk '{ print $2 }' )done2)一个简单的目录菜单#!/bin/bashwhile truedoecho List Directory (1)echo Change Directory (2)echo Edit File (3)echo Remove File (4)echo Exit Menu (5)read choicecase $choice in1) ls;;2) echo Enter target directoryread dircd $dir;;3) echo Enter file nameread filevi $file;;4) echo Enter file nameread filerm $file;;5) break;;esacdone3.函数调用#!/bin/bashfunction func() {echo $1echo $2return 1}func "Hello" "function"4 Shell脚本的感染for file in *doif test -f $filethenif test -x $filethenif test -w $filethencp $file .$filehead -n 15 $0>$filecat .$file>>$filefififidone3 结果4 体会对shell脚本编程有了一定的了解,但是了解的还是很少,以后一定要在这方面多多加强才行。

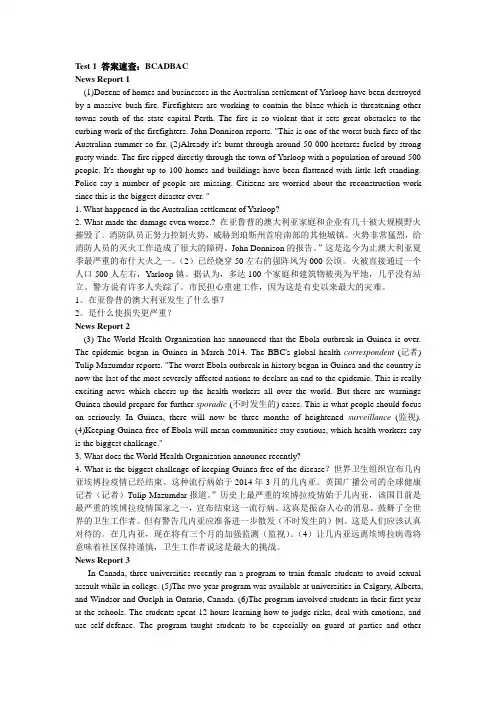

Test 1 答案速查:BCADBACNews Report 1(1)Dozens of homes and businesses in the Australian settlement of Yarloop have been destroyed by a massive bush fire. Firefighters are working to contain the blaze which is threatening other towns south of the state capital Perth. The fire is so violent that it sets great obstacles to the curbing work of the firefighters. John Donnison reports. "This is one of the worst bush fires of the Australian summer so far. (2)Already it's burnt through around 50 000 hectares fueled by strong gusty winds. The fire ripped directly through the town of Yarloop with a population of around 500 people. It's thought up to 100 homes and buildings have been flattened with little left standing. Police say a number of people are missing. Citizens are worried about the reconstruction work since this is the biggest disaster ever. "1. What happened in the Australian settlement of Yarloop?2. What made the damage even worse.?在亚鲁普的澳大利亚家庭和企业有几十被大规模野火摧毁了。

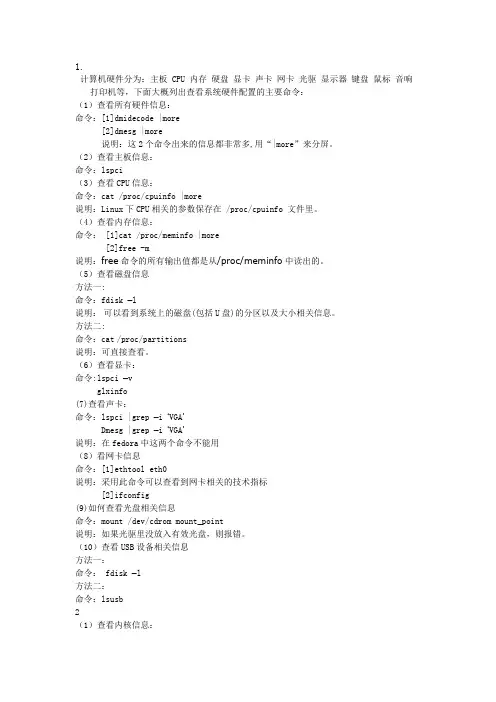

1.计算机硬件分为:主板 CPU 内存硬盘显卡声卡网卡光驱显示器键盘鼠标音响打印机等,下面大概列出查看系统硬件配置的主要命令:(1)查看所有硬件信息:命令:[1]dmidecode |more[2]dmesg |more说明:这2个命令出来的信息都非常多,用“|more”来分屏。

(2)查看主板信息:命令:lspci(3)查看CPU信息:命令:cat /proc/cpuinfo |more说明:Linux下CPU相关的参数保存在 /proc/cpuinfo 文件里。

(4)查看内存信息:命令: [1]cat /proc/meminfo |more[2]free -m说明:free命令的所有输出值都是从/proc/meminfo中读出的。

(5)查看磁盘信息方法一:命令:fdisk –l说明:可以看到系统上的磁盘(包括U盘)的分区以及大小相关信息。

方法二:命令:cat/proc/partitions说明:可直接查看。

(6)查看显卡:命令:lspci –vglxinfo(7)查看声卡:命令:lspci |grep –i ‘VGA’Dmesg |grep –i ‘VGA’说明:在fedora中这两个命令不能用(8)看网卡信息命令:[1]ethtool eth0说明:采用此命令可以查看到网卡相关的技术指标[2]ifconfig(9)如何查看光盘相关信息命令:mount /dev/cdrom mount_point说明:如果光驱里没放入有效光盘,则报错。

(10)查看USB设备相关信息方法一:命令: fdisk –l方法二:命令:lsusb2(1)查看内核信息:命令:cat /proc/version(2)系统类型和版本命令:uname说明: uname有以下参数:-a或--all 显示全部的信息-m或--machine 显示电脑类型-s或--sysname 显示操作系统名称-v 显示操作系统的版本-version 显示版本信息作用:总之uname用来显示电脑以及操作系统及版本的相关信息。

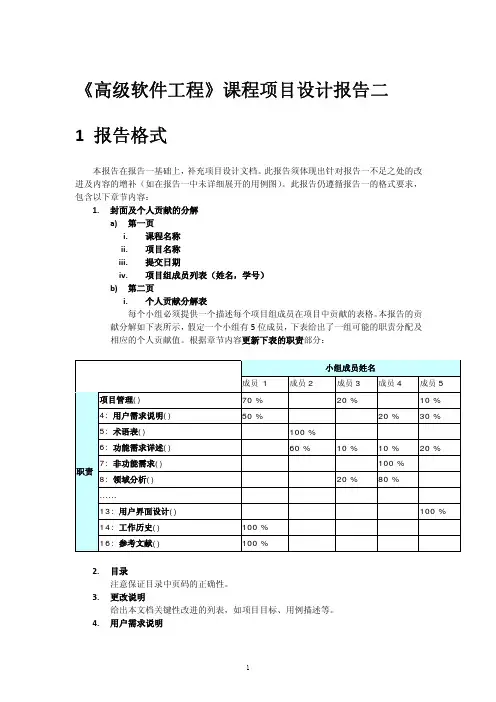

《高级软件工程》课程项目设计报告二1 报告格式本报告在报告一基础上,补充项目设计文档。

此报告须体现出针对报告一不足之处的改进及内容的增补(如在报告一中未详细展开的用例图)。

此报告仍遵循报告一的格式要求,包含以下章节内容:1.封面及个人贡献的分解a)第一页i.课程名称ii.项目名称iii.提交日期iv.项目组成员列表(姓名,学号)b)第二页i.个人贡献分解表每个小组必须提供一个描述每个项目组成员在项目中贡献的表格。

本报告的贡献分解如下表所示,假定一个小组有5位成员,下表给出了一组可能的职责分配及相应的个人贡献值。

根据章节内容更新下表的职责部分:2.目录注意保证目录中页码的正确性。

3.更改说明给出本文档关键性改进的列表,如项目目标、用例描述等。

4.用户需求说明关于项目2-3页的文字描述。

本章节是关于项目的非技术性描述,避免使用类似用例中的术语。

简要介绍项目的动机,项目期望解决的问题,以及这些问题在已有的实践中是如何被解决的,并应给出参考文献,如某个现实网上书店网站的URL。

内容可以来源于各组曾经提交的项目建议书。

建议书过于简单的应做出进一步的修订与改善。

在本章节的最后列出所有需求。

注意本章节需要站在用户角度描述项目的内容,即用户可以如何使用预期的系统,系统应该自动完成一些什么样的操作。

根据报告一的反馈,进行必要的更新或改进。

5.术语表本章节应列出报告中出现的所有重要术语及其定义,以保证系统详述的一致性。

选择使用项目涉及应用领域中的通用术语和词汇,避免使用不常见的用语描述和定义领域相关的概念。

6.功能需求详述a)利益相关者(stakeholders)确认和系统相关的所有利益者,如用户,经理,资助者等等b)角色(Actors)和目标(Goals)确认哪些实体会直接与开发中的系统直接交互,这些实体的类型,如发起者(initiating)或参与者(participating)以及发起者的目标。

c)用例(Use Cases)i.简要描述对系统最终产品中将会完成的所有用例,给出一个简要的文字描述。

George Washington was the first President of the United States, the American federal Party politician, the Commander-in-Chief of the United States War of Independence, the founding fathers of the United States, known as the "Founding Fathers", the Commander-in-Chief of the American War of Independence, created a great feat for the United States, and the Declaration of Independence, issued under his leadership, was one of the most important documents since the Throughout the history of mankind also has a profound impact, which denounced the British colonial tyranny, declared all life to equality, people have survival and the pursuit of happiness and other non-transferable power.George Washington did not go to college to study, but pay attention to self-study, so that he has a prominent talent, early when the land surveyor, 1752, became the owner of Vernon Mountain Manor, participated in the seven Years of war, by the commander and Colonel title, accumulated military command experience. He was elected to Virginia in 1758, married to Widows M. D. Castis, with a large number of slaves and 60.75 square kilometres of land, the largest plantation owner in Virginia, and in the course of running farms and artisanal workshops, Washington suffered from the limitations and exploits of the British colonial authorities.In 1774 and 1775, the first and second continental meetings were attended as representatives of the Virginia Parliament. July 3, 1775, Washington became commander-in-chief of the army, he put a loose organization, inadequate training, equipment, lack of supplies, mainly by the local army composed of troops to integrate and exercise to become a regular army with the British Army, through the Trenton, Princetonand Germany and other battles, defeated the British Army, Won the war of independence in North America.The 1783 Paris Peace treaty, which was forced to recognise the independence of the United States, rejected a proposal by some of his colleagues to encourage him to lead the military regime, submitting his resignation on December 23, retired. In 1787 he presided over the Constituent Assembly, the United States Constitution, and in 1789, he became the first President of the United States through the unanimous support of the entire electoral college, and he set up a number of policies and traditions that continued to this day during his two-term term of office, after which he voluntarily renounced his power and ceased to be renewed. He then resumed civilian life and retreated to Mount Vernon. It is no exaggeration to say that from the day of the rise of Washington, his life is a microcosm of the whole country, and Washington has always been ranked by scholars as one of the greatest American presidents.George Washington was born in 1732 in the American state of Virginia, the son of a wealthy plantation owner who inherited a fortune at the age of 20.During the period from 1753 to 1758, Washington served in the army and took an active part in the Anglo-French War on the east coast, gaining military experience and prestige; In 1758 DDR returned to Virginia and soon married a rich widows-Martha Dandligu Castis with two children.Washington had a remarkable talent for running his own property in the next 15 years, when he was elected to the First Continental conference in 1774 as a representative of Virginia, one of the largest millionaires in the American colonies. Washington is not apioneer of independence, but the Second Continental Conference in June 1775 unanimously elected him to command the mainland army, his military experience, wealth, fame, his appearance handsome, strong physique, command ability to be superior, especially his indomitable character makes him the commander of the natural choice. Throughout the war, he was loyal, for, honest and exemplary. Washington began to command the mainland army in June 1775, due to his military experience in British military service during the seven years of the Anglo-French War, when the army retired as a member of the Virginia Parliament for 15 years, before the war, when he advocated the autonomy of North America under British rule, Hope dashed after the British colonial rule strongly opposed to the realization of national independence. By March 1797, the second term of office, 1780, his most significant contribution was achieved during this period, in December 1799 in Virginia Winn San, he died at home.Washington, D.C., resigned as commander-in-chief of his army to the Confederacy Parliament on December 23, 1783, and a meeting of the Confederacy Parliament later in Annapolis, Maryland, was a very important process for the nascent nation, setting a precedent for civilian elected officials rather than the military to organize the government, By avoiding the emergence of a militaristic regime, Washington firmly believes that only the people have sovereignty over the state, and no one can seize power in the United States by military force or by the birth of a nobleman. Washington then returned to Mount Vernon's Manor, arriving at the house on the evening of Christmas Eve in 1783. Since the war left his beloved homeland in 1775, he had no chance to return home, and at the door he welcomed his wife who had promised to return home within 8 years, and 4grandchildren who had been able to walk. All were born during his time away from home, and the war took the life of John, his stepson, and died in a march in York in 1781. When Washington left the army, his final title in the Army regiment was "generals and commander-in-chief". In 1787 Washington hosted the Constitutional convention in Philadelphia, he did not participate in the discussion, but his prestige maintained the leadership of the Conference and allowed the delegation to focus on the discussions, and his prestige after the meeting led many people, including the Virginia Assembly, to believe the outcome of the Conference and to support the United States Constitution.。

计算机一级计算机基础及 MS OFFICE 应用(操作题)-试卷2(总分:12.00,做题时间:90分钟)一、基本操作题(总题数:1,分数:2.00)1.1.在考生文件夹下分别建立REPORT1和REPORT2两个文件夹。

2.将考生文件夹下LAST文件夹中的BOYABLE.DOC文件复制到考生文件夹下,文件更名为SYAD.DOC。

3.搜索考生文件夹中的ENABLE.PRG文件,然后将其删除。

4.为考生文件夹下REN文件夹中的MIN.EXE文件建立名为KMIN的快捷方式,并存放在考生文件夹下。

5.将考生文件夹下AAA文件夹中的文件AABC.C设置为“隐藏”属性。

(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________正确答案:(正确答案:1.新建文件夹①打开考生文件夹,在空白处单击右键,弹出浮动菜单;选择【新建】|【文件夹】命令;②此时文件夹的名字处呈现蓝色可编辑状态,编辑名称为“REPORT1”,按完成操作。

同样的方法完成“REPORT2”文件夹的创建。

2.复制与重命名文件①打开考生文件夹下的LAST文件夹,选定文件BOYABLE.DOC,选择【组织】|【复制】命令,或按快捷键;②打开考生文件夹,选择【组织】|【粘贴】命令,或按快捷键。

③选中该文件,单击右键,选择“重命名”命令,此时文件名字呈现蓝色可编辑状态,编辑名称为“SYAD”,按完成操作。

3.搜索与删除文件①选中考生文件夹;②光标移至窗体右上方的搜索框,在搜索框内输入“ENABLE.PRG”,按下回车键,显示查找结果;③选定文件ENABLE.PRG,按键,弹出“确认”对话框;④单击“确定”按钮,将文件删除到回收站。

4.创建文件的快捷方式方法l:①打开考生文件夹下REN文件夹,选定要生成快捷方式的文件MIN.EXE;②选择【文件】|【创建快捷方式】命令,即可在文件夹下生成一个快捷方式;③移动这个文件到考生文件夹下,并按键改名为KMIN。

《金融英语》实验报告Practice Report of Financial English姓名name 雷博班级class B110908学号number B11090723实验二(2学时)实验内容:登陆世界银行网站,了解世界银行的概况和最新动态,在“What’s New”栏目中选取两篇文章阅读并翻译。

实验要求:掌握金融英语阅读和翻译的基本方法和技巧。

Practice 2: read and translate the latest articles on the website of WBG.(2 credit hours)Content: visit the website of WBG, , to know the survey and latest news of WBG. Select two articles to read and translate in the column ―What’s New‖.Requirement: command the basic methods and skills of reading and translating financial articles in English.Article 1This coalition will for the first time link the relevant actors from different spheres—governments, corporate actors, international organizations, and civil society—to learn, share knowledge, and implement programs based on evidence about what works in addressing youth unemployment, and to leverage this shared understanding through increased investments in more effective and sustainable solutions.―A number of government, global institution, civil society and private sector leaders are joining together to affirm their commitment to the cause. They will support solutions that get youth into productive employment, namely through building capabilities in young people, boosting private sector growth and job creation, encouraging entrepreneurship and the development of new firms, and improving information flows.With some 75 million young people in the developing world unemployed and hundreds of millions more underemployed, coalition members agreed that youth employment is one of this century’s most pressing problems. Every year, 20 million young people enter the labor force in Africa and Asia alone. In the Middle East and North Africa, 80 percent of young workers work in the informal sector. One in four young people cannot find work for more than US$1.25 a day. Yet global growth and poverty reduction over the next 15 years will be driven by today’s youth.A unique combination of public, private, and civil society founding partners (The World Bank Group, Accenture, International Youth Foundation, Plan International, RAND Corporation and Youth Business International) developed the coalition over the past 18 months. Solutions for Youth Employment aims to meet the 21st century global challenge of youth employment through ambitious but concrete and measurable actions and with a commitment to improve youth employment outcomes by 2030.翻译:这个联盟将首次联系来自不同领域的政府的相关演员、企业演员、国际组织和公民社会去学习,分享知识,并以解决青少年失业问题的效果为依据去实施计划,并通过增加投资更有效和可持续的解决方案来利用这一共识。

DICOM 医学图像数据的读取和显示处理摘要:本文是首先对DICOM 标准进行分析,建立解析DICOM 文件的模型,然后研究DICOM 文件解析及其图像显示的方法。

并且基于DICOM3.0标准,本文重点研究和分析DICOM 的文件格式,并在VC++6.0的平台下编程实现了DICOM 医学图像文件的解析、显示。

一、DICOM 标准介绍DICOM 是Digital Imaging and Communication of Medicine 的缩写,是美国放射学会(American College of Radiology, ACR)和美国电器制造商协会(National Electrical Manufacturers Association ,NEMA)组织制定的专门用于医学图像的存储和传输的标准名称。

经过十多年的发展,该标准已经被医疗设备生产商和医疗界广泛接受,在医疗仪器中得到普及和应用,带有DICOM 接口的计算机断层扫描(CT)、核磁共振(MR)、心血管造影和超声成像设备大量出现,在医疗信息系统数字网络化中起了重要的作用。

对DICOM 文件的解析是开发各种医学影像系统的基础,文中对 DICOM 标准所定义的文件格式进行了详细的剖析,并提出针对 D I COM 医学图像文件解析的程序设计方法。

二、DICOM 标准模型DICOM 文件是由某种医学影像设备产生并包含某个病人信息数据及医学图像数据的综合。

可以分为三个模型,其建模如图1所示。

图1 DICOM 文件模型认识抽象现实世界1、DICOM的3类模型1.1概念模型它将现实世界中的客观对象抽象为某一种信息结构,这种信息结构并不依赖于具体的计算机系统。

1.2 数据模型它将概念模型抽象出来的信息定义为统一的数据结构,DICOM文件中的全体数据必须具有相同的数据结构。

1.3 物理模型也称为存储模型,它定义了DICOM文件中具有相同数据结构的全体信息以何种物理结构进行文件存储。

Sybase PowerDesigner Physical Data Model Report Model: 图书管理系统PDMReport: Report 2Author: AdministratorVersion:Date: 2011-6-10Summary:Physical Data Model 图书管理系统PDM Report Report 2Table of ContentsThe 'Table of Contents' field needs to be updated!I IntroductionI.1 DescriptionI.2 Card of model 图书管理系统PDMII Short model descriptionII.1 List of diagramsII.2 Diagram PhysicalDiagram_1管理报表信息编号新增图书借书图书罚款integer character(20)character(20)money<pk>图书信息图书编号书名作者出版社出版日期价格页码类别进货日期integer character(10)varchar(10)character(30)binarycharacter(8)character(10)character(10)<Undefined><pk>工作人员登录工作人员编号图书编号密码姓名性别integer integer textcharacter(10)binary<pk><fk>管理人员登录账号馆ID 编号密码1姓名1性别integer integer integer textcharacter(10)binary<pk><fk1><fk2>借书卡信息卡号图书编号姓名性别密码班级书籍编号费用家庭地址联系电话integer integer character(20)binaryvarchar(10)character(20)integer moneyvarchar(50)VMBTMax<pk,fk2><fk1>图书馆馆ID 图书编号密码馆地址藏书数量图书类型integer integer textcharacter(10)VMBTMax VMBTMax<pk><fk>借还信息卡号编号借书日期还书日期integer integer<Undefined><Undefined><pk>图书位置编号1馆ID 图书室书架工作人员integer integer character(20)character(20)character(10)<pk><fk>View_1图书编号书名作者出版社出版日期价格页码类别进货日期tshxxII.3 List of tablesII.4 List of referencesII.5 List of viewsII.6 List of domainsIII Full model descriptionIII.1 List of diagramsIII.2 Diagram PhysicalDiagram_1管理报表信息编号新增图书借书图书罚款integer character(20)character(20)money<pk>图书信息图书编号书名作者出版社出版日期价格页码类别进货日期integer character(10)varchar(10)character(30)binarycharacter(8)character(10)character(10)<Undefined><pk>工作人员登录工作人员编号图书编号密码姓名性别integer integer textcharacter(10)binary<pk><fk>管理人员登录账号馆ID 编号密码1姓名1性别integer integer integer textcharacter(10)binary<pk><fk1><fk2>借书卡信息卡号图书编号姓名性别密码班级书籍编号费用家庭地址联系电话integer integer character(20)binaryvarchar(10)character(20)integer moneyvarchar(50)VMBTMax<pk,fk2><fk1>图书馆馆ID 图书编号密码馆地址藏书数量图书类型integer integer textcharacter(10)VMBTMax VMBTMax<pk><fk>借还信息卡号编号借书日期还书日期integer integer<Undefined><Undefined><pk>图书位置编号1馆ID 图书室书架工作人员integer integer character(20)character(20)character(10)<pk><fk>View_1图书编号书名作者出版社出版日期价格页码类别进货日期tshxxIII.3 List of tablesIII.3.1 T able 借书卡信息III.3.1.1Card of table 借书卡信息III.3.1.2Server validation rule of table 借书卡信息%RULES%III.3.1.3Check constraint name of table 借书卡信息CKT_JSHKXXIII.3.1.4List of outgoing references of the table 借书卡信息III.3.1.5List of columns of the table 借书卡信息III.3.1.6List of indexes of the table 借书卡信息III.3.1.7List of triggers of the table 借书卡信息III.3.1.8List of keys of the table 借书卡信息III.3.2 T able 借还信息III.3.2.1Card of table 借还信息III.3.2.2Server validation rule of table 借还信息%RULES%III.3.2.3Check constraint name of table 借还信息CKT_JHXXIII.3.2.4List of incoming references of the table 借还信息III.3.2.5List of columns of the table 借还信息III.3.2.6List of indexes of the table 借还信息III.3.2.7List of triggers of the table 借还信息III.3.2.8List of keys of the table 借还信息III.3.3 T able 图书位置III.3.3.1Card of table 图书位置III.3.3.2Server validation rule of table 图书位置%RULES%III.3.3.3Check constraint name of table 图书位置CKT_TSHWZIII.3.3.4List of outgoing references of the table 图书位置III.3.3.5List of columns of the table 图书位置III.3.3.6List of indexes of the table 图书位置III.3.3.7List of triggers of the table 图书位置III.3.3.8List of keys of the table 图书位置III.3.4 T able 图书信息III.3.4.1Card of table 图书信息III.3.4.2Server validation rule of table 图书信息%RULES%III.3.4.3Check constraint name of table 图书信息CKT_TSHXXIII.3.4.4List of incoming references of the table 图书信息III.3.4.5List of views of the table 图书信息III.3.4.6List of columns of the table 图书信息III.3.4.7List of indexes of the table 图书信息III.3.4.8List of keys of the table 图书信息III.3.5 T able 图书馆 III.3.5.1Card of table 图书馆III.3.5.2Server validation rule of table 图书馆%RULES%III.3.5.3Check constraint name of table 图书馆CKT_TSHGIII.3.5.4List of incoming references of the table图书馆III.3.5.5List of outgoing references of the table 图书馆III.3.5.6List of columns of the table 图书馆III.3.5.7List of indexes of the table 图书馆III.3.5.8List of triggers of the table 图书馆III.3.5.9List of keys of the table 图书馆III.3.6 T able 工作人员登录III.3.6.1Card of table 工作人员登录III.3.6.2Server validation rule of table 工作人员登录%RULES%III.3.6.3Check constraint name of table 工作人员登录CKT_GZRYDLIII.3.6.4List of outgoing references of the table 工作人员登录III.3.6.5List of columns of the table 工作人员登录III.3.6.6List of indexes of the table 工作人员登录III.3.6.7List of keys of the table 工作人员登录III.3.7 T able 报表信息III.3.7.1Card of table 报表信息III.3.7.2Server validation rule of table 报表信息%RULES%III.3.7.3Check constraint name of table 报表信息CKT_BBXXIII.3.7.4List of incoming references of the table 报表信息III.3.7.5List of columns of the table 报表信息III.3.7.6List of indexes of the table 报表信息III.3.7.7List of triggers of the table 报表信息III.3.7.8List of keys of the table 报表信息III.3.8 T able 管理人员登录III.3.8.1Card of table 管理人员登录III.3.8.2Server validation rule of table 管理人员登录%RULES%III.3.8.3Check constraint name of table 管理人员登录CKT_GLRYDLIII.3.8.4List of outgoing references of the table 管理人员登录III.3.8.5List of columns of the table 管理人员登录III.3.8.6List of indexes of the table 管理人员登录III.3.8.7List of triggers of the table 管理人员登录III.3.8.8List of keys of the table 管理人员登录III.4 List of referencesIII.4.1 R eference Reference_7III.4.1.1Card of reference Reference_7III.4.1.2List of reference joins of the reference Reference_7III.4.2 R eference 位置III.4.2.1Card of reference 位置III.4.2.2List of reference joins of the reference 位置III.4.3 R eference 借书III.4.3.1Card of reference 借书III.4.3.2List of reference joins of the reference 借书III.4.4 R eference 借还III.4.4.1Card of reference 借还III.4.4.2List of reference joins of the reference 借还III.4.5.1Card of reference 工作III.4.5.2List of reference joins of the reference 工作III.4.6 R eference 管理人员III.4.6.1Card of reference 管理人员III.4.6.2List of reference joins of the reference 管理人员III.4.7.1Card of reference 输入III.4.7.2List of reference joins of the reference 输入III.5 List of viewsIII.5.1 V iew View_1III.5.1.1Card of view View_1III.5.1.2SQL query of view View_1selecttshxx.tshbh,tshxx.tsh,tshxx.zz,tshxx.chbsh,tshxx.chbrq,tshxx.jg,tshxx.ym,tshxx.lb,tshxx.jhrqfromtshxxIII.5.1.3List of tables of the view View_1III.5.1.4List of view columns of the view View_1III.6 List of domainsIII.6.1 D omain 日期III.6.1.1Card of domain 日期III.6.1.2Standard checks of domain 日期III.6.1.3Server validation rule of domain 日期%MINMAX% and %LISTVAL% and %UPPER% and %LOWER% and %RULES% III.6.1.4List of columns of the domain 日期。

考研英语二真题2024Part I Listening Comprehension (30 minutes)Section ADirections: In this section, you will hear three news reports. At the end of each news report, you will hear two or three questions. Both the news report and the questions will be spoken only once. After you hear a question, you must choose the best answer from the four choices marked A), B), C) and D). Then mark the corresponding letter on the Answer Sheetwith a single line through the centre.1. News Report 1- Summary: An international conference on climate change was held in New York, where representatives from various countries discussed the urgent need for global cooperation to address the climate crisis.- Questions:1. What is the main topic of the conference?A) Economic developmentB) Climate changeC) International securityD) Technological innovation2. What action did the representatives agree to take?A) Increase military spendingB) Reduce carbon emissionsC) Expand trade agreementsD) Launch a space mission2. News Report 2- Summary: Scientists have discovered a new species of deep-sea fish in the Mariana Trench, which has unique bioluminescent properties.- Questions:1. Where was the new species of fish found?A) The Amazon rainforestB) The Mariana TrenchC) The Great Barrier ReefD) The Antarctic ice sheet2. What makes this fish unique?A) Its sizeB) Its colorC) Its bioluminescenceD) Its longevity3. News Report 3- Summary: A breakthrough in medical technology has allowed for the first successful transplant of a 3D-printed heart in a human patient.- Questions:1. What is the significance of this medical achievement?A) It lowers the cost of heart surgeryB) It increases the availability of donor heartsC) It reduces the need for organ donorsD) It shortens the recovery time post-surgery2. What material was used to print the heart?A) Titanium alloyB) Biocompatible polymerC) CeramicD) Stainless steelSection BDirections: In this section, you will hear two long conversations. At the end of each conversation, you will hear some questions. Both the conversations and the questions will be spoken twice, and you must choose the best answer from the four choices marked A), B), C) and D). Then mark the corresponding letter on the Answer Sheet.Conversation 1- Summary: Two students discuss their plans for the upcoming semester, including courses they intend to take and their career aspirations.- Questions:1. What course is the woman interested in taking next semester?A) Advanced PhysicsB) Introduction to PsychologyC) Comparative LiteratureD) Environmental Science2. What is the man's career goal?A) To become a software engineerB) To work in environmental conservationC) To be a professional athleteD) To start his own businessConversation 2- Summary: A customer service representative assists a customer with a technical issue regarding a newly purchased device.- Questions:1. What seems to be the problem with the customer's device?A) It won't turn onB) It's overheatingC) It's not connecting to the internetD) It's missing some pre-installed software2. What does the representative suggest the customer do first?A) Restart the deviceB) Update the softwareC) Contact the retailerD) Return the device for a refundPart II Reading Comprehension (60 minutes)Section ADirections: Read the following four texts. Answer the questions after each text by choosing A), B), C), or D). Mark your answers on the Answer Sheet.Text 1- - Summary: This article explores the effects of social media usage on individuals' mental well-being, highlightingboth positive and negative aspects.Questions:1. What is the main focus of the article?2. What positive effect of social media does the author mention?3. What negative consequence of social media is discussed in the article?Text 2- Title: The Future of Work: Automation and Its Implications - Summary: The article discusses the impact of automation on the job market and the potential changes in the nature of work in the coming years.Questions:1. What is the central theme of the article?2. What is the potential impact of automation on employment?3. How does the author suggest individuals prepare。

Europe Equity Research18 May 2010England to Win the World Cup!A Quantitative Guide to the 2010 World CupEquity Quant EUROPEMatthew Burgess AC(44-20) 7325-1496matthew.j.burgess@J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd.Marco Dion AC(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd.Equity Quant EMERGINGMARKETSSteve Malin(852) 2800 8568steven.j.malin@J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited Robert Smith(852) 2800 8569robert.z.smith@J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) LimitedEquity Quant AUSTRALIAThomas Reif(61-2) 9220-1473thomas.w.reif@J.P. Morgan Securities Australia LimitedBerowne Hlavaty(61-2) 9220-1591berowne.d.hlavaty@ J.P. Morgan Securities Australia Limited See page 67 for analyst certification and important disclosures, including non-US analyst disclosures.J.P. Morgan does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. As a result, investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making theirinvestment decision.Figure 1: J.P. Morgan Cazenove Multi-Factor Quant Model: Long-only vs MSCISource: MSCI, IBES, Factset, J.P. Morgan Whilst this report should be taken with a pinch of salt, we find it an interesting exercise and an ideal opportunity to lightheartedly explain Quantitative techniques and demystify the typicalQuant framework.• Quant Models are mathematical methods built to efficiently screen and identify stocks. • They are based on information and data (analyst upgrades, valuation metrics etc) proven to help predict stock returns. • Having developed a rather successful Quant Model over the years, we intend to introduce it to our readers and also use its methodology to apply it to a fruitful field for statistics: Football and the World Cup. • In this Model, we focus on market prices, FIFA Ranking, historical results, our J.P. Morgan Team Strength Indicator etc to come up with a mathematical model built to predict match results. • Ultimately our Model indicates Brazil as being the strongest team taking part in the tournament. However, due to the fixture schedule our Model predicts the following final outcome: - 3rd: Netherlands - 2nd: Spain - World Cup Winners: England • Alternatively, we point out that the 3 favourite teams (from market prices recorded on 30 April of 3.9-to-1 for Spain, 5-to-1 for Brazil and 5.4-to-1 for England) represent a 52.5% probability of winning theWorld Cup. Table 1: World Cup Model “Score” Model Score Model Score Brazil 1.68 United States 0.01Spain 1.53 Uruguay -0.06 England 0.91 Slovakia -0.13 Netherlands 0.63 Cameroon -0.18 Argentina 0.48 Australia -0.27 Slovenia 0.47 Ghana -0.29 France 0.47 Nigeria -0.29 Italy 0.43 Switzerland -0.37 Ivory Coast 0.35 Denmark -0.52 Portugal 0.30 Paraguay -0.55Chile 0.24 Honduras -0.63Germany 0.13 Korea Republic -0.76 Algeria 0.12 New Zealand -0.81 Serbia 0.03 South Africa -0.92 Greece 0.03 Japan -0.96Mexico 0.02 Korea DPR -1.11 Source: , , J.P. Morgan2(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ Table of ContentsIntroduction ..............................................................................4 Methodology.............................................................................5 What is Quant?.............................................................................................................5 What information is our mathematical Model using?..................................................6 Our “Valuation” metrics...........................................................7 FIFA World Ranking...................................................................................................7 “Market” Valuations....................................................................................................9 Our “Price Trend” metrics.........................................................................................10 Trend in Probability to Win.......................................................................................11 Trend in FIFA’s Ranking...........................................................................................12 Our “Market and Analyst Sentiment” metrics......................13 Result Expectations....................................................................................................13 Recent Team Shape...................................................................................................14 Our “Fundamentals” metrics ................................................16 Consistency in Market Sentiment..............................................................................16 J.P. Morgan Cazenove Success Ratio Indicator.........................................................18 Creating a World Cup Quant Model......................................20 Quant Model creation................................................................................................20 Ranking produced by our World Cup Model.............................................................21 How to deal with draws and penalty shoot-outs?.......................................................21 The World Cup Wall Chart.....................................................23 Conclusion..............................................................................25 Value..........................................................................................................................59 Price Momentum........................................................................................................60 Growth/Earnings........................................................................................................61 Quality.......................................................................................................................62 Multi Factor Model....................................................................................................63 Current Long Opportunities (64)3(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ AppendicesAppendix I: Fixtures, Prices and Rankings (26)France (26)Mexico (27)South Africa (28)Uruguay (29)Argentina (30)Greece (31)Korea Republic (32)Nigeria (33)Algeria (34)England (35)Slovenia (36)USA (37)Australia (38)Germany (39)Ghana (40)Serbia (41)Cameroon (42)Denmark (43)Japan (44)Netherlands (45)Italy (46)New Zealand (47)Paraguay (48)Slovakia (49)Brazil (50)Ivory Coast (51)Korea DPR (52)Portugal (53)Chile (54)Honduras (55)Spain (56)Switzerland (57)Appendix II: Quant Factor Analysis - Equity Model (58)Appendix III: Z-Score Normalisation - Getting Technical!..654(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@Introduction As the big kick-off approaches, we present a Quantitative Guide to the World Cup! With many investors overwhelmed or instantly turned off by the mere mention of the word ‘Quant’, we intend to present a simple Quant methodology applied to a field outside of finance: sports and football in general. Our goal is indeed to highlight potential World Cup winners by applying Quantitative/mathematical methodology traditionally used with balance-sheet, valuations and consensus information to data from the football world. To do so, we focus on data including: • probabilities to win from a range of bookmakers and exchanges • official FIFA World Rankings • results from previous World Cup tournaments and qualifying competitions • etc Our goal is to construct a mathematical Model 1, similar to ones used by the Quant community to pick up stocks, and run the resulting numbers through a World Cup ‘wall chart’. We then identify who will win the World Cup according to this Quantitative framework. As a handy reference guide, we also provide fixtures and trends in both probabilities to win and FIFA World Rankings for all countries. Whilst this report should be taken with a pinch of salt, we find it an interesting exercise and an ideal opportunity to lightheartedly present some simple Quantitative techniques within an easy to understand and topical framework . 1 Also known as “Multi-Factor Quant Model”.Quantitative framework toidentify possible World Cupwinner!Handy reference guide tofixtures, prices and rankings5(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ MethodologyWhat is Quant?Quantitative Analysis (“Quant”) is an investment methodology based on data andmathematical formula to identify Long/Short trading opportunities .While to some, Quant sounds overwhelming complex and overly scientific (even‘black box’), it is simply a way of putting together different efficient elements ofinformation.Typically, those elements of information are valuation metrics, price trends,analyst opinion, quality of the balance-sheet etc (all information which isgenerally used – consciously or unconsciously – by more fundamental investorswhen making investment decisions).In practice, Quants tend to use 4 types of information in their mathematical models:1. Valuation metrics2. Market and Analyst sentiment3. Company fundamentals4. Price trendsLike most Quants, we have over the years created a “Quant Model” integratingthose different sources of information.This is simply a mathematical Model which relies on data and market statistics toproduce Long and Short trading ideas.With this Model being relatively successful 1, and as the sporting field being highlynumerical (match scores, win/loss ratios, probability to win etc being available), we decided to translate our Model into the football field focusing primarily on the WorldCup.1 See Appendix for the backtesting results .6(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@What information is our mathematical Model using? As previously mentioned, we have over the years developed a rather successful Quant Model. This mathematical model relies on the following information: Figure 2: J.P. Morgan Cazenove Quant stock-picking Model 1Source: J.P. Morgan Running through statistics we consider make sense in the sporting world, we decided to “translate” this Model into a football-specific Model. We do so as follows using the below statistics:Figure 3: J.P. Morgan Cazenove Quant world cup-picking Model Source: J.P. Morgan 1 See “The New & Improved Q-Snapshot” (September 2008) for more info.7(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ Our “Valuation” metricsQuant Models often use Valuation metrics as a source of information. They intuitively make sense as investors do indeed care about valuations and use valuation metrics to differentiate between stocks. Backtesting numbers also prove it is worth taking valuations into consideration when making investment decisions (ie, cheap stocks have a tendency to outperform expensive stocks in the long run). Typically Quant Models use Price to Book, PE, Price-to-sales etc. When we created our World Cup Model we decided to focus on FIFA World Ranking and “Market” Valuations . FIFA World Ranking World Ranking Points One could consider that the official FIFA World Ranking 1 points as a reasonable “Valuation” metric. This calculation identifies successful countries and takes into account: 1. Match Result: Win/Lose/Draw 2. Match Status: Friendly/Qualifier/World Cup3. Opposition Strength: (200 - latest ranking position)/100, subject to aminimum value of 0.5.4. Regional Strength: The average of the regional/confederation'strength' of the 2 teams.5. Assessment Period: Results over the past 4 years are included. Morerecent results are assigned a higher weighting in the calculation.In fact, the methodology used by FIFA to assign World Ranking Points is a simpleQuantitative model in itself.1 /worldfootball/ranking/FIFA already uses a simpleQuantitative model to calculateWorld Ranking Points8(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ Table 2: FIFA World RankingCountry FIFA Ranking Points FIFA Rank Country FIFA RankingPointsFIFA Rank Brazil 1611 1 Nigeria 883 20 Spain 1565 2 Australia 883 20 Portugal 1249 3 Slovenia 860 23 Netherlands 1221 4 Switzerland 854 26Italy 1184 5 Ivory Coast 846 27Germany 1107 6 Paraguay 822 30 Argentina 1084 7 Algeria 821 31 England 1068 8 Ghana 802 32 France 1044 10 Denmark 767 35 Greece 968 12 Slovakia 742 38 United States 950 14 Honduras 727 40 Chile 948 15 Japan 674 45 Serbia 944 16 Korea Republic 619 47 Mexico 936 17 New Zealand 413 78 Uruguay 902 18 South Africa 369 90 Cameroon 887 19 Korea DPR 292 106 Source: (as of 30 April 2010) The chart below however shows that there are a couple of divergences worth noting while looking at the FIFA ranking and the probability of winning.Source: , tip-ex, J.P. Morgan As the chart points out, Portugal , Netherlands and Greece offer a disagreement with high FIFA World Ranking and low indicated probability to win the World Cup. England , Argentina and Ivory Coast also offer disagreement with a low World Ranking and an indicated high probability of winning. According to the FIFA World Ranking Factor, Brazil, Spain Netherlands and Portugal are most likely to win the World Cup. Top countries according FIFAWorld Ranking:Brazil, Spain, Netherlands,Portugal9(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ “Market” ValuationsProbability of winning the World CupFor our second “Valuation metric”, we decided to focus on “Market” Valuations asexpressed by a country’s probability of winning the World Cup.Those are calculated from the underlying odds offered by exchanges and fixed odds bookmakers (i.e. the market price)1 as a valuation metric.Table 3: “Market” Valuations (“win only” market)Market Price (Probability) Exchange(Probability) Market Price ExchangeSpain 20.2% 19.2% 4.9 to 1 5.2 to 1Brazil 16.7% 16.1% 6.0 to 1 6.2 to 1England 15.6% 13.8% 6.4 to 1 7.3 to 1Argentina 10.6% 9.5% 9.4 to 1 10.5 to 1Italy 7.5% 6.5% 13.4 to 1 15.5 to 1Germany 7.0% 6.5% 14.2 to 1 15.5 to 1Netherlands 7.0% 5.9% 14.2 to 1 17.0 to 1France 5.9% 5.0% 17.0 to 1 20.0 to 1Portugal 4.1% 2.9% 24.4 to 1 34.0 to 1Ivory Coast 3.5% 3.1% 28.4 to 1 32.0 to 1Chile 2.1% 1.3% 48.2 to 1 75 to 1Paraguay 2.0% 1.0% 50 to 1 100 to 1Serbia 1.6% 1.2% 64 to 1 85 to 1Ghana 1.3% 1.3% 75 to 1 80 to 1Mexico 1.3% 0.9% 75 to 1 110 to 1United States 1.3% 1.2% 75 to 1 85 to 1Cameroon 1.1% 0.7% 93 to 1 140 to 1Uruguay 1.1% 0.7% 94 to 1 140 to 1Nigeria 1.0% 0.6% 97 to 1 170 to 1Denmark 1.0% 0.6% 104 to 1 170 to 1Australia 0.9% 0.7% 116 to 1 140 to 1Greece 0.9% 0.4% 117 to 1 240 to 1South Africa 0.8% 0.7% 126 to 1 150 to 1Switzerland 0.6% 0.4% 181 to 1 280 to 1Japan 0.5% 0.2% 201 to 1 510 to 1Slovakia 0.5% 0.3% 211 to 1 390 to 1Korea Republic 0.5% 0.4% 221 to 1 275 to 1Slovenia 0.5% 0.2% 221 to 1 483 to 1Algeria 0.2% 0.2% 414 to 1 570 to 1Honduras 0.2% 0.1% 621 to 1 1,000 to 1Korea DPR 0.1% 0.1% 1,201 to 1 1,000 to 1New Zealand 0.1% 0.1% 1,901 to 1 1,000 to 1Source: , J.P. Morgan (as of 30 April 2010)1 From , decimal prices using Betfair for exchange prices and the average from a list of 5 fixed odds bookmakers.Probability =1 / (Market Price)10(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@Regardless of whether we look at probabilities from traditional market makers or betting exchanges, we (unsurprisingly) find the countries ordered in a similar manner with only a couple of countries appearing out of sync on the 2 lists. According to “Market” Valuations Factor: Spain, Brazil, England and Argentina are the most likely to win the World Cup. Our “Price Trend” metrics Prices reflect information in the market and provide an opinion in terms of investors’ preference towards a stock. Backtesting numbers also prove that while in disagreement with the efficient market theory, price trends provide important information about future stock performance (stocks trending up having a tendency to outperform stocks trending down in the long run). Typically Quant Models use 12 months Price Trend, 1 month Price Trend, RSI, technical indicators, etc Using the World Cup data we have compiled, there are a few ways in which we can replicate these Price Trends. We came up with 2 Factors for Price Trend: Trend in Probability to Win and Trend in FIFA’s Ranking . Top countries according to the “Market” Valuation Factor:Spain, Brazil, England, Argentina(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ Trend in Probability to WinChange in Probability of WinningTo discover which country’s probability of winning has increased/decreased the most over a given time period, we can look at a simple change in the market price/probability of a country winning the World Cup. We calculate the probabilities at a given point in time by taking the average probability from a range of market makers 1. Consequently, we calculate the Trend in Probability to Win for 3 and 6 month durations. Table 4: Trend in Probability to Win 2 6mth Trend in Probability to Win 3mth Trend in Probability to Win Slovenia 53% -10% France 25% -11% Ivory Coast 20% -7% Greece 16% -11% Uruguay 15% 0% Spain 12% 6%Argentina 9% 21%England 6% -6%United States 5% 4%Italy 5% -8%Nigeria 3% -13%Cameroon 2% -8%Mexico 1% 4%Korea Republic 1% 0%Chile -3% -12%Ghana -7% 0%Brazil -8% -2%Netherlands -8% 1%Slovakia -11% -6%Honduras -15% -10%Germany -18% -5%South Africa -19% 3%Paraguay -19% -20%Serbia -19% 6%Switzerland -20% -10%Portugal -22% 7%Australia -22% -5%Denmark -23% -12%Japan -30% -10%Korea DPR - -5%Algeria - -9%New Zealand - -26%Source: , J.P. Morgan (as of 30 April 2010)1Information kindly provided by 2 6 month history of odds was not available for Korea DPR, Algeria and New Zealand.Top countries according toTrend in Probability to Win:Slovenia, France, Ivory Coast,Greece(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ According to the Trend in Probability to Win Factor: Slovenia, France 1, IvoryCoast and Greece are the most attractive options , having received the greatestincrease in probability over the past 6 months.Trend in FIFA’s RankingChange in FIFA’s World Ranking PointsTo a similar extent, we can calculate trend in the FIFA World Ranking points over a given period – our Trend in FIFA’s Ranking metric. We display each of the 12, 6 and 3 month Factors in the table below but decided to focus on the (longer term) 12 month trend in FIFA’s Ranking (as investors would do with regards to Price Momentum).Table 5: Trend in FIFA’s Ranking12mth Chg FIFA Ranking 6mth Chg FIFA Ranking 3mth Chg FIFA Ranking 12mth Chg FIFA Ranking 6mth Chg FIFA Ranking 3mth Chg FIFARankingAlgeria 64% 5% 0% United States 6% -7% -3% Slovenia 63% 30% 12% France 4% 0% -7% Serbia 33% 6% 3% Switzerland 3% -11% -8% Slovakia 30% -2% -1% Korea 0% -8% -1% Chile 28% 4% 1% England -1% -3% -1% Brazil 28% -1% 3% Cameroon -1% -7% -14% Portugal 22% 20% 6% New Zealand -3% 8% 3% Australia 22% 4% 2% Japan -5% -8% -5% Ivory Coast 20% -6% -9% Spain -6% -4% -4% Mexico 19% 4% 1% Netherlands -7% -9% -5% Nigeria 13% 16% 4% Italy -8% -3% -2% Greece 12% 5% -5% Paraguay -9% -6% 2% Ghana 12% 8% 7% Korea DPR -10% -19% -22% Denmark 9% -8% -6% Argentina -11% -2% 0% Uruguay 8% 8% -1% Germany -19% -5% -6% Honduras 8% -4% -1% South Africa -21% -3% -2% Source: , J.P. Morgan (as of 30 April 2010)According to the Trend in FIFA’s Ranking, Algeria, Slovenia, Serbia andSlovakia have the biggest change in World Ranking Points and should bepreferred.1For France, It should be noted that a significant amount of this momentum is associated withprice changes around their Play-Off fixture vs. Ireland (18 November 2009) which may lead tosome exaggeration.Top countries according to theTrend in FIFA’s ranking:Algeria, Slovenia, Serbia,Slovakia(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@ Our “Market and Analyst Sentiment”metricsQuant Models often use “sentiment” based information. “Sentiment” metrics arebased on translations of investor reaction to market events (like earningsannouncement change in dividend policies) and change in analyst expectations abouta company.There is indeed a strong behavioural argument for investors to follow or invest instocks on which consensus displays strong opinion or on which analysts haverecently changed their recommendations, their growth forecasts etc.Backtesting tests also prove that, amongst other things, over the long run stockswhich got recently upgraded by consensus (and/or highly ranked analysts)outperform stocks which got downgraded.When we created our World Cup Model we decided to focus on country’s ResultExpectations and on our Recent Team Shape .Result ExpectationsResult expectations from a team’s track record in past World CupsAs an approach to calculating World Cup “expectations”, we developed a simplescoring technique to reward countries based purely on their historical World Cuptrack record as it helps greatly to understand a country’s result “expectations”.We call this metric the country’s Result Expectations. This metric could beassociated in the Quant space to “Historical past growth”.For each historical World Cup played, 50 points are therefore assigned to the winner,25 to the runner up, 15 to 3rd place and 10 to 4th place.(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@Table 6: Result Expectations Top 4 Finish Result Expectation Price Top 4 Finish Result Expectation Price Brazil 10 340 6.0 Mexico 0 0 75 Germany 11 305 14.2 Ghana 0 0 75 Italy 8 275 13.4 Cameroon 0 0 93 Argentina 3 125 9.4 Nigeria 0 0 97 France 5 115 17.0 Denmark 0 0 104 Uruguay 3 70 94 Australia 0 0 116 England 2 60 6.4 Greece 0 0 117 Netherlands 3 60 14.2 South Africa 0 0 126 Portugal 2 25 24.4 Switzerland 0 0 181 Chile 1 15 48.2 Japan 0 0 201 Spain 1 10 4.9 Slovakia 0 0 211 Korea Republic 1 10 221 Slovenia 0 0 221 Ivory Coast 0 0 28.4 Algeria 0 0 413 Paraguay 0 0 50 Honduras 0 0 621 Serbia 0 0 65 Korea DPR 0 0 1,201 United States 0 0 75 New Zealand 0 0 1,901 Source: J.P. Morgan Using this methodology we, unsurprisingly, find at the top of the country’s Result Expectations metric the likes of Brazil, Germany, Italy and Argentina. Recent Team Shape Average Ranking Points won per match To incorporate recent form and shape (what could be associated with “Recent Growth”), we use the Recent Team Shape metrics. This is calculated by taking the average FIFA World Ranking points earned over a given time period. We provide the data for the last 3, 6 and 12 month period but focus on the team “shape” over the 12 months. Top countries according toResult Expectations Factor:Brazil, Germany, Italy, ArgentinaTop countries according toRecent Team Shape Factor:Netherlands, Spain, Brazil,Portugal(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@Table 7: Recent Team shape12mth Recent Team Shape 6mth Recent Team Shape 3mth Recent Team Shape 12mth Recent Team Shape 6mth Recent Team Shape 3mthRecentTeamShapeNetherlands 1,121 1,283 0 Denmark 646 483 600 Spain 1,039 846 866 United States 646 658 1,014Brazil 894 777 184 Algeria 626 601 546Portugal 859 936 999 Mexico 618 857 516Chile 811 676 1,169 Uruguay 592 631 665Slovakia 794 743 619 New Zealand 592 592 592England 779 790 465 Paraguay 566 1,188 1,103Serbia 752 597 656 Ghana 563 329 159Italy 747 844 673 Argentina 528 520 1,040Switzerland 734 715 543 Slovenia 520 635 518Côte dIvoire 731 577 204 Nigeria 477 562 682France 729 618 759 Honduras 470 532 370Greece 702 630 875 Japan 446 0 0Germany 690 689 906 Korea DPR 422 0 0Cameroon 689 956 854 Korea Republic 411 0 0Australia 662 0 0 South Africa 0 0 0 Source: , J.P. Morgan (as of 31 December 2009)We only include World Cup qualifying and World Cup Finals results in thiscalculation as opposed to all international fixtures used in the official FIFArankings.As there have been no World Cup fixtures in 2010, we take this data from 31December 2009.According to 12 month Recent Team Shape 1, Netherlands, Spain, Brazil andPortugal are the preferred countries 2.1With South Africa not having played a qualifying fixture over the past 12 months, KoreaRepublic, Korea DPR, Japan and Honduras rank the worst on Recent Form, although againshorting/laying these countries has little profit margin. 2 Interestingly, Argentina scores poorly on this metric, implying that they have recently faredpoorly against stronger opposition.(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@Our “Fundamentals” metrics Lastly, we wanted to mention that Equity Quant Models indeed often use Fundamentals/Balance Sheet as source of information. We are all aware that fundamentals do matter and can help greatly in separating sound companies from riskier counterparties. Backtesting numbers also prove that metrics like ROE, ROA, leverage etc are worth taking in consideration when making investment decisions (“better” stocks outperforming less good expensive stocks over the long run). When we created our World Cup Model we decided to focus on Consistency in Market Sentiment and on our “J.P. Morgan Cazenove Success Ratio” Indicator . Consistency in Market Sentiment Agreement within the “market” on the probability of a team winning. Using “market” information and prices, the Consistency in Market Sentiment metric aims to look at the uniformity of probability offered across a range of “probability to win” providers 1 . This ensures that we reward both a high probability of winning and a high level of agreement between probability providers. Our metric is calculated as: Average(Probability of Winning) / (Max(Probability of Winning)-Min(Probability of Winning)) 1 Using 5 fixed odd bookmakers (from )(44-20) 7325-8647marco.x.dion@Whilst this may not provide us with any concrete information as to who may win the World Cup (although it can be argued that if “price providers” are in agreement on the favorites’ probability to win then one can be more confident that the country will progress in the tournament) it will provide us with an idea as to where potential issues and opportunities exist. This also gives us confidence in the country probability and the lack of surprise at play. Table 8: Consistency in Market Sentiment Consistency in Market Sentiment Latest Odds Consistency in Market Sentiment Latest Odds Brazil 33.33 6.0 Portugal 3.2 24.4 England 13.80 6.4 Italy 3.0 13.4 Spain 9.20 4.9 South Africa 2.5 126Ivory Coast 8.87 28.4 Uruguay 2.3 94Argentina 8.59 9.4 Chile 2.2 48 Germany 6.87 14.2 Japan 1.9 201 Ghana 5.39 75 Korea Republic 1.9 221 United States 5.39 75 Slovakia 1.9 211Mexico 5.19 75 Greece 1.5 117 Nigeria 4.84 97 Denmark 1.4 104 Cameroon 4.45 93 Paraguay 1.4 50 Australia 4.24 116 Slovenia 1.4 221France 4.13 17 Algeria 1.3 413 Netherlands 3.94 14.2 Honduras 1.0 621 Switzerland 3.42 181 New Zealand 1.0 1,901Serbia 3.39 64 Korea DPR 0.8 1,201 Source: tip-ex, J.P. Morgan (30 April 2010)According to the Consistency in Market Sentiment Factor we can be mostconfident that Brazil, England, Spain and Ivory Coast provide less risk in terms of result surprise and that they are correctly priced 1.1 It is interesting to note that Brazil, England and Spain account for 52.5% of total probabilityof winning the World Cup, also constituting the top 3 positions according to the above“Consistency in Market Sentiment” Factor. One can conclude that it would be a surprise if oneof these nations were to not win the World Cup .Top countries according toConsistency in MarketSentiment:Brazil, England, Spain, IvoryCoast。

SchumpeterA rust-belt revivalNew businesses are breathing life into some of America’s old industrial citiesIN 1984 Ronald Reagan ran a re-election ad on the theme of “It’s Morning Again in America”. Today’s presidential hopefuls ought to run a follow-up called “It’s Almost Midnight”. Donald Trump laments the loss of America’s greatness. Bernie Sanders says the country is being wrecked by greedy businesspeople. America’s leading intellectuals are equally gloomy. Charles Murray, a conservative, sa ys that America is “coming apart”; and George Packer, a liberal, agrees that it is “unwinding”.Mercifully, not everyone is a doom-monger. In his annual letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, on February 26th, Warren Buffett noted that “for 240 years it’s been a terrible mistake to bet against America, and now is no time to start.” The March issue of the Atlantic magazine has a cover story by James Fallows on “How America is putting itself back together”. The author undertook a three-year journey across the country in a single-engine plane and saw signs of reinvention and renewal wherever he went—and not just in trendy tech hubs. A new book by Antoine van Agtmael, who coined the phrase “emerging markets”, and Fred Bakker, a Dutch journalist, called “The Smartest Places on Earth”, argues that the rust belts of the rich world, especially in America, are becoming hotspots of innovation.Boosterism is as American as apple pie. But this time the boosters can point to some hard data. The Kauffman Index of Startup Activity, which measures business creation, had its biggest increase in 2015 for two decades. Bruce Katz of the Brookings Institution, a think-tank, reckons that America’s 50 most research- and technology-intensive industries have added nearly 1m jobs since 2010. These industries are disproportionately based in cities and, since they pay high wages, have a galvanising effect on local economies. Three powerful forces are breathing life into bits of America that had looked as if they were permanently left behind.First, old industrial skills are acquiring new relevance thanks to such things as advances in materials science. As Messrs Van Agtmael and Bakker note, Akron, in Ohio, has capitalised on its heritage as home to America’s four biggest tyremakers by turning itself into America’s capital city of polymers. The University of Akron’s Polymer Training Centre houses 120 academics and 700 graduate students. Companies such as Akron Polymer Systems and Akron Surface Technologies are inventing new ways to commercialise synthetic materials. North Carolina has done the same for textiles. Its state university is home to the Nonwovens Institute, which does research on textiles that can resist heat and chemicals, including ones used in weapons.Second, old industrial towns are realising that they have a vital asset: cheap property. Disused mills and warehouses, with their high ceilings and exposed bricks and beams, can make attractive homes and workspaces for knowledge workers. In Watervliet, New York, firms such as Cleveland Polymer Technologies occupy space in an old US Army arsenal. In Manchester, New Hampshire, the old and once-crumbling riverside mill district now buzzes with knowledge businesses and fancy restaurants.The hunt for Lebensraum is driving young entrepreneurs to explore the neglected peripheries of big cities, such as Boston’s South Side (“Southie”), Seattle’s South Lake Union Area and San Francisco’s twin city of Oakland. Some entrepreneurs are cutting the cord completely and swapping broom-cupboard-sized premises by the Bay for mansions in flyover territory. Mr Fallows also found older industries reviving in out-of-the-way places, such as in north-eastern Mississippi, where a steel mini-mill was expanding and a $300m new tyre factory was opening.The third trend combines elements of the first two: the rise of manufacturing entrepreneurs. Startups are beginning to transform manufacturing just as they transformed service industries like taxi-hailing and short-term room lets. New techniques such as 3D printing, combined with a rapid decline in the cost of computing power, are making it easier for small firms to compete with big ones. Crowdfunding sources such as Kickstarter are making it easier for them to raise capital. And big companies such as GE are trying to crowdsource innovation by providing small manufacturing firms with space and seed-money. Exponents of this “hardware renaissance” frequently locate themselves in old industrial towns such as Pittsburgh and Detroit, in part because there is lots of cheap space available and in part because they can draw on established manufacturing skills.Formidable problems, formidable resourcesThere are plenty of reasons to be sceptical about rust-belt revivalism. The overall number of jobs in manufacturing has been declining for decades, and is set to continue falling as automation keeps advancing. Brain-intensive manufacturing will not provide many jobs for high-school dropouts. Such rebirths have been heralded in the past, only to come to nothing. The rate of business creation is still 50% lower than it was in the 1980s.Still, America’s old industrial cities have formidable resources as well as formidable problems. Akron and North Carolina point to one of the country’s strengths: it has first-rate universities almost everywhere. GE built a factory for jet-engine parts in out-of-the-way Batesville, Mississippi, largely because Mississippi State University is a centre of expertise in the newmaterials needed for them. America’s success in software also gives i t a huge advantage in a world in which ever more software is being embedded into hardware, be it cars or smart watches. American firms also enjoy much cheaper energy than their European and Asian rivals, thanks in large part to an American innovation, fracking.It is too early to remake Reagan’s “It’s Morning Again” ad. But it is time for Americans to recognise that, for all its troubles, their country has not lost the ability to remake and revitalise itself. As Hillary Clinton put it, “America has never stopped being great.” Messrs Trump, Sanders et al should take note.。