外文翻译-小额信贷

- 格式:doc

- 大小:49.00 KB

- 文档页数:8

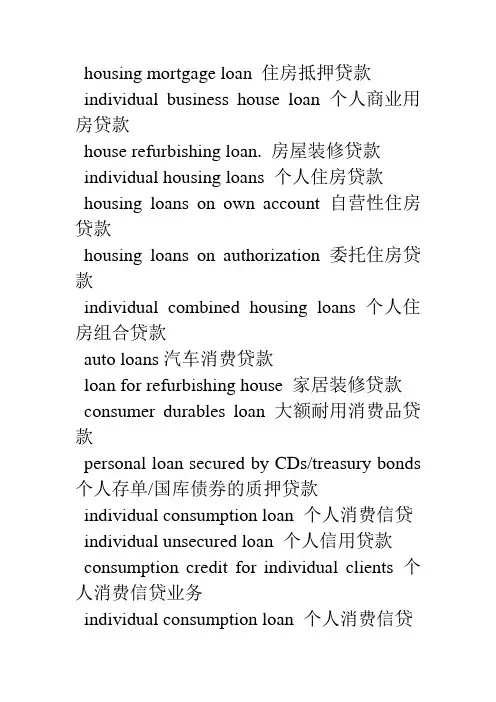

housing mortgage loan 住房抵押贷款individual business house loan 个人商业用房贷款

house refurbishing loan. 房屋装修贷款individual housing loans 个人住房贷款housing loans on own account 自营性住房贷款

housing loans on authorization 委托住房贷款

individual combined housing loans 个人住房组合贷款

auto loans汽车消费贷款

loan for refurbishing house 家居装修贷款consumer durables loan 大额耐用消费品贷款

personal loan secured by CDs/treasury bonds 个人存单/国库债券的质押贷款

individual consumption loan 个人消费信贷individual unsecured loan 个人信用贷款consumption credit for individual clients 个人消费信贷业务

individual consumption loan 个人消费信贷

secured loan 抵押放款(担保放款) small amount private loans 小额贷款industrial loan 工业贷款 agricultural loan 农业贷款

loan office 贷款处

interest-free loans 无息贷款 special-purpose loan 专项贷款。

小额贷款和小额信贷的内容_中和农信小额信贷小额贷款(MicroCredit)是以个人或家庭为核心的经营类贷款,贷款的金额一般为1000元以上,20万元以下。

小额贷款是微小贷款在技术和实际应用上的延伸。

小额贷款在中国:主要是服务于三农、中小企业。

小额贷款公司的设立,合理的将一些民间资金集中了起来,规范了民间借贷市场,同时也有效地解决了三农、中小企业融资难的问题。

小额信贷是一种城乡低收入阶层为服务对象的小规模的金融服务方式。

小额信贷旨在通过金融服务为贫困农户或微型企业提供获得自我就业和自我发展的机会,促进其走向自我生存和发展。

它既是一种金融服务的创新,又是一种扶贫的重要方式。

小额信贷的预防政策对借款人的有关资格资质进行审查,是借款合同签订的前提,也是借贷行为必不可少的程序。

审查的重要意义在于评估贷款风险的大小,近而决定贷款交易的成功与否。

一、审查风险贷款风险的产生,往往在贷款审查阶段就开始了,综合司法实践中发生的纠纷,可以看出,在贷款审查阶段出现的风险主要出现在以下环节。

(一)审查内容遗漏银行审贷人员挂一漏万,造成信贷风险。

贷款审查是一项细致的工作,要求调查人员就贷款主体的资格、资质、信用、财产状况进行系统的考察和调查。

(二)没有尽职调查在实践中,有关审贷人员,往往只重视文件的识别,而缺乏尽职的调查,这样,很难识别贷款中的欺诈,造成信贷风险。

(三)判断错误银行没有对有关内容听取专家意见,或由专业人员进行专业的判断。

审贷过程中,不仅仅要查明事实,更应当就有关事实进行法律、财务等方面进行专业的判断。

二、贷前调查的法律内容(一)关于借款人的合法成立和持续有效的存在审查借款人的合法地位。

如果是企业,应当审查借款人是否依法成立,有无从事相关业务的资格和资质,查看营业执照、资质证书,应当注意相关证照是否经过年检或相关审验。

(二)关于借款人的资信考察借款人的注册资本是否与借款相适应;审查是否有明显的抽逃注册资本情况;以往的借贷和还款情况;以及借款人的产品质量、环保、纳税等有无可能影响还款的违法情况。

贫困,是当今世界“3P”(人口、贫困、污染)问题之一,尤其是发展中国家面临的一个巨大问题。

各个国家也都采取了很多扶贫措施来改变这一现状,但大多并未取得成功。

广大发展中国家贫困户的一个共同特点是缺少发展所需要的资金。

广大贫困户由于缺少可以作为抵押物的资产,他们很难从正规金融途径获得发展所需要的资金,资金这一生产要素的短缺而形成的瓶颈严重制约着劳动、土地等生产要素的生产能力。

传统的扶贫模式也很难解决资金到达贫困户手中的问题,资金的到户率低,贫困户的资金也多数没有被用于生产领域而是用来消费,造成大量贷款无法归还,而政府又没有足够的资金源源不断的投入到这一无底洞之中,扶贫效果很差。

由于没有其他资金参与扶贫活动,扶贫活动难以持久,一些暂时脱贫的农户由于种种原因又返贫的现象经常发生。

各个国家都在努力探索适宜的扶贫方式,小额信贷应运而生。

小额信贷最初作为一种扶贫手段在发展中国家兴起,带有很强的福利性质。

经过数十年的发展,由于成功地推行了一系列金融创新措施,小额信贷机构在解决贫困农户资金短缺和金融机构自我持续发展两个方面取得了双赢成就,它在一些发展中国家成功地帮助了一部分最贫困人口获得了基本谋生手段,显著提高了生活水平,从而促进了社会和谐稳定。

作为一种新型的金融方式,小额信贷所取得的成效是举世公认的。

联合国将2005年确定为“国际小额信贷年”。

2006年,孟加拉乡村银行(GB) 及其创始人穆罕默德·尤努斯更是因为“当大量的人口找到摆脱贫困的出路时,持久的和平才能得以实现”,而获得了该年度的诺贝尔和平奖。

1993年,中国社会科学院农村发展研究所首先将与国际规范接轨的孟加拉“乡村银行”模式的小额信贷引入中国,成立了“扶贫经济合作社”。

1996年在中央扶贫工作会议确定扶贫到户的方针后,由我国政府扶贫资金推动的小额信贷运动在国内大规模铺开。

在十多年的发展过程中,中国的小额信贷实践得到我国政府、中央银行,以及许多国际机构的关注和支持。

国际小额信贷发展趋势中国人民银行研究局焦瑾璞杨骏虽然遍布世界各地的小额信贷各有其发展路径,且已经发展出各具特色的组织和业务模式,但总体而言,随着国际社会和各国政府基于农村经济增长和扶贫目标对各类小额信贷机构(项目)抱持越来越多的期待,小额信贷的发展趋势已经逐渐变得清晰。

一、从小额贷款(Microcredit)到微型金融(Microfinance)基于对低收人人群究竟需要何种金融服务的不同理解,长期以来,不同的机构和项目在小额信贷应该仅仅向其客户提供小额贷款服务,还是应该提供包括小额储蓄(包括自愿储蓄和强制储蓄)、小额保险、汇款和租赁等在内的综合性金融服务,甚或还应该直接以社会发展为己任从而提供除金融服务之外的其他社会服务(如孟加拉GB、BRAC那样)之间,存在着激烈的争论。

但越来越多的机构已经认识到,除小额贷款之外的其他金融服务对于低收人人口至少具有同等的重要性,这意味着国际范围内小额信贷的发展,开始逐步从传统“小额贷款”(Micro—credit)向为低收人客户提供全面金融服务的“微型金融”(Microfinance)过渡。

第一,大多数情况下,自愿储蓄业务为低收人人口提供了安全、方便、可细分的而且付息的储蓄方式,这种方式显然优于落后地区的人们常常采用的以牲畜、实物、现金或者债权进行储蓄的传统方式[1]。

而在孟加拉乡村银行(GB)的传统模式下,强制储蓄和团体贷款是密切结合的,这种情况下的强制储蓄的目的据称是为了“帮助穷人养成储蓄的习惯,而不是让他们因为无法储蓄而把所有的产品都消费掉”。

第二,因为农业先天的弱质性和较大风险的存在,小额保险业务在落后的农业地区更具意义,这有助于减少低收人人口面对风险时的脆弱性。

当然,由于农业本质上具有突出的区域性、行业性协变风险,这种为低收入农业人口提供的保险必须进行某种适切的创新。

第三,收费合理的汇款业务越来越重要,劳动力跨部门、跨地区乃至跨境流动导致对“工资汇寄回乡"从而汇款业务的巨大需求,这不仅对于落后地区的发展日显重要,它的巨大潜在商业价值已经引起一些国际著名商业银行如美洲银行、汇丰银行和花旗银行的关注。

本文部分内容来自网络整理,本司不为其真实性负责,如有异议或侵权请及时联系,本司将立即删除!== 本文为word格式,下载后可方便编辑和修改! ==简单阐述一下小额信贷篇一:什么是小额信贷什么是小额信贷?“小额信贷”(Microfinance),从国际流行观点看,是指专向中低收入阶层提供小额度的持续的信贷服务活动。

以贫困或中低收入群体为特定目标客户并提供适合特定目标阶层客户的金融产品服务,是小额信贷项目区别于正规金融机构的常规金融服务以及传统扶贫项目的本质特征;而这类为特定目标客户提供特殊金融产品服务的项目或机构,追求自身财务自立和持续性目标,构成它与一般政府或捐助机构长期补贴的发展项目和传统扶贫项目的本质差异。

国际主流观点认为,各种模式的小额信贷均包括两个基本层次的含义:第一,为大量低收入(包括贫困)人口提供金融服务;第二,保证小额信贷机构自身的生存与发展。

这两个既相互联系又相互矛盾的方面,构成了小额信贷的完整要素,两者缺一都不能称为是完善或规范的小额信贷。

从本质上说,小额信贷是将组织制度创新和金融创新的信贷活动与扶贫到户(或扶持到户)项目有机地结合成一体。

目前,国际上公认取得成效的小额信贷项目多开始于70~80年代,实施小额信贷的组织机构主要是各类金融机构和非政府组织。

金融机构主要包括:国有商业银行、专门成立的小额信贷扶贫银行和由非政府组织实施的小额信贷项目演变成的股份制银行以及非正规金融中介服务组织,例如信贷联盟、协会、合作社等。

经过20多年的实践,特别是近10年的发展,小额信贷已经从世界的某些区域扩展到几乎覆盖整个发展中国家和一些发达国家。

目前就其展开的规模而言,已有达到全国规模的样板。

就其组织机构而言,有国家正规银行实施小额信贷成功的例证;有非政府组织服务于最贫困人口和实现机构自我生存双重目标的典型;有不断扩展业务的专门小额信贷机构的先锋;有专门成立特殊银行满足特殊需求的成功典范。

尽管如此,规范和成功的小额信贷的历史还不长,成功的比例也不高,在国际社会尚属一件新生事物,仍面临着各种各样的风险和挑战。

国际小额信贷的发展一小额信贷的概念(一)小额信贷的含义小额信贷是金融行业的一部分,也是一种发展工具。

小额信贷的含义可以包括金融服务和社会服务。

它满足了那些从未或很少得到正规金融服务的家庭和企业的金融和社会的需求。

因此,小额信贷机构的主要目标客户是中低收入家庭和微小企业。

若干年前,人们多使用“小额贷款”(microcredit)而不是“小额信贷”(microfinance),反映出当时主要是强调贷款发放。

然而,今天人们清楚地认识到中低收入家庭需要广泛的金融服务,包括:存款服务、信贷服务、支付服务和保险等。

良好的小额信贷操作具有以下特征:①小笔金融交易。

一般来说,每笔贷款和存款额度低于(现也有数倍于)本国的年度人均国内生产总值。

②流畅且简单的表格和程序。

③接近客户的操作方式。

④不延误的和可靠的交易。

⑤一般无需严格的物质抵押担保。

(二)服务对象一般说来,以贫困线划分,社会人群可分为贫困者和非贫困者;从关注贫困的角度,又可细分为6类:赤贫者、极贫者、贫困者、脆弱的非贫困者、一般收入者和富裕者。

根据世界银行扶贫协商小组(CGAP)的意见,小额信贷的服务对象一般覆盖其中的3~4类:极贫者、贫困者、脆弱的非贫困者或可加上一般收入者。

其中,赤贫者约占贫困线以下人口的10%;极贫者占40%;贫困者占50%。

此为理论意义上的说法,实践中则复杂得多。

而且,有的小额信贷机构或产品已将服务对象扩展到小企业甚至中型企业。

(三)小额信贷服务供给者小额信贷代表着一种特殊类型的“业务”,但它不意味着特殊的机构模式或特别的法律形式。

金融服务的供给有正规部门,如各种类型的银行;也有非常不正规的供给者,包括家庭和朋友、存贷轮会和高利贷者等。

吸储小额信贷机构是构成正规金融部门的一个部分,受到专门的银行规制和监督。

相反,半正规的金融机构,如非政府组织和典当行代表一种特殊的机构类型,这类机构不允许动员公众储蓄,不受金融部门的规制,而由其他政府部门批准执照和监督。

小微企业融资外文文献翻译小微企业融资外文文献翻译(文档含中英文对照即英文原文和中文翻译)原文:Micro Enterprise Finance in Uganda: Path Dependence and Other and Determinants of Financing DecisionsDr. Winifred Tarinyeba- KiryabwireAbstractAccess to finance literature in developing countries focuses onaccess to credit constraints of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) micro enterprises because they are considered the drivers of economic growth. However, in low income countries, micro enterprises play a much more significant role than SMEs because of their contribution to non-agricultural self-employment. The predominant use of informal credit rather than formal credit shows that the manner in which micro enterprises are formed and conduct their businesses favors the former over the latter. In addition, other factors such as lengthy credit application procedures, negative perceptions about credit application processes make informal credit more attractive. On the other hand specific factors such as business diversification, the need to acquire business inputs or assets than cannot be obtained using supplier credit are associated with a tendency to use formal credit.IntroductionIt well established that in markets where access to credit is constrained, it is the smaller businesses that have the most difficulty accessing credit. Various policy interventions have been made to improve access to credit including reforming the information and contractual frameworks, macro-economic performance, competitiveness in the financial system, and regulatory frameworks that enablefinancial institutions to develop products for SMEs such as leasing and factoring. Over the past ten years, policy makers in developing and low income countries have focused on microfinance as an intervention to bridge the access to credit gap and improve access to credit for those than cannot obtain credit from mainstream financial institutions such as commercial banks. However, despite, the use of what are often termed as “innovative lending” methods that are designed to ease access to credit, such as use of group lending and other collateral substitutes, micro enterprises continue to rely heavily on informal finance as opposed to formal credit. While other studies have focused broadly on factors that inhibit access to credit, this article seeks to throw some light on specific characteristics of micro enterprises that make them more inclined to use informal credit, as well as specific factors that are more associated with use of formal credit. The former are what I term as path dependence factors.The majority of micro enterprises operate as informally established sole proprietorships. This finding is consistent with the literature on micro enterprises, particularly the fact that they operate in the informal sector. However, nearly all of the enterprises had some form of trading license issued by the local government of the area in whichthey operate. The license identifies the owner of the business and its location, and is renewable every financial year. Most respondents did not understand the concept of business incorporation and thought that having a trading license meant that they were incorporated. Several factors can be attributed to the manner in which micro enterprises are established. First, proprietors generally understand neither the concept of incorporation nor the financial and legal implications of establishing a business as a legal entity separate from its owner. Second, the majority of micro enterprises start as spontaneous business or economic opportunities, rather than as well-thought out business ventures, particularly businesses that operate by the road side, or in other strategic areas, such as telephone booths that operate along busy streets. The owners are primarily concerned with the economic opportunity that the business presents rather than with the formalities of establishing the business. Third, rule of law issues also explain the manner in which businesses generally are established and financed. Although a mechanism exists for incorporating businesses in Uganda, the process and the legal and regulatory burdens, associated with formalizing a business, create costs that, in most cases, far outweigh the benefits or even the economic opportunity created by the business.Commenting on the role of law in determining the efficiency of the economic activities it regulates, Hernando De Soto argues that if laws impede or disrupt economic efficiency, they not only impose unnecessary costs of accessing and remaining in the formal system, but costs of operating informally as well. The former include the time and cost of registering a business, taxes and complying with bureaucratic procedures. On the other hand, the costs of informality include costs of avoiding penalties, evading taxes and labor laws and costs that result from absence of good laws such as not inadequate property rights protection, inability to use the contract system, and inefficiencies associated with extra contractual law.Businesses in Uganda are registered by the Registrar of Companies under the Company’s Act. The office of the Registrar of Companies is located in the capital city of Kampala and this imposes a burden on businesses that operate in other parts of the country that would wish to be registered. However, remoteness of the business registration office was not the primary inhibitor because the tendency not to register was as pronounced in businesses close to the registration office, as it was in those that were remotely placed. In addition, the following fees are required to incorporate a company: a name search andreservation fee of Ugshs. 25,000 ($12.50), stamp duty of 0.5% of the value of the share capital, memorandum and articles of association registration fee of Ugshs. 35,000 ($17.5), and a registration fee ranging from Ugshs. 50,000 to 4,000,000 ($25 to 2000).Legal systems characterized by low regulatory burden, shareholder and creditor rights protection, and efficient bankruptcy processes are associated with incorporated businesses and increased access to finance. On the other hand, inadequate legal protection is associated with limited business incorporation, low joint entrepreneurial activity, and higher financing obstacles. These impediments are what De Soto refers to as the mystery of legal failure. He argues that although nearly every developing and former communist nation has a formal property system, most citizens cannot gain access to it and their only alternative is to retreat with their assets into the extra legal sector where they can live and do business.译文乌干达小微企业融资路径依赖和融资的决定性因素Dr. Winifred Tarinyeba- Kiryabwire摘要通过查阅发展中国家的金融文献,我们往往可以发现由于中小企业是推动发展中国家经济增长的主要动力源,其金融问趣则主要侧重于中小企业的融资受限方面。

原文The Question of Sustainability for Microfinance Institutions1.PrefaceMicroentrepreneurs have considerable difficulty accessing capital from mainstream financial institutions. One key reason is that the costs of informationabout the characteristics and risk levels of borrowers are high. Relationship-based financing has been promoted as a potential solution to information as ymmetry problems in the distribution of credit to small businesses. In this paper we seek tobetter understand the implications for providers of “microfinance” in pursuing such as trategy. We discuss relationship-based financing as practiced by microfinance institutions MFIs in the United States analyze their lending process and present amodel for determining the break-even price of a microcredit product. Comparing themodel’s results with actual prices offered by existing institutions reveals that credit isgenerally being offered at a range of subsidized rates to microentrepreneurs. This means that MFIs have to raise additional resources from grants or other funds eachyear to sustain their operations as few are able to survive on the income generated from their lending and related operations. Such subsidization of credit has implications for the long-term sustainability of institutions serving this market andcan help explain why mainstream financial institutions have not directly funded microenterprises. We conclude with a discussion of the role of nonprofit organizations in small business credit markets the impact of pricing on their potential sustain ability and self-sufficiency and the implications for strategies to better structure the creditmarket for microbusinesses.2.The MFI Lending Model in the United StatesMarketing drives the business model in terms of the volume of potential borrowers that an MFI is able to access and the pool of loans it can develop. Given that MFIs do not accept deposits and have no formal prior insight into a fresh potential customer base they must invest in attracting new borrowers. Marketing leads are generated from a variety of sources: soliciting loan renewals from existing borrowers marketing to existing clients for referrals “grassroots” networking with institutions possessing a complimentary footprint in the target environment andthe mass media. At the outset of operations before a borrower base is developed portfolio growth is determined by the effectiveness of marketing through network and mass media channels. Once a borrower pool is established marketing efforts can be shifted toward lower-cost marketing to existing borrowers and their peer networks. Even solo ans will likely attrite from a portfolio at a faster rate than renewals and borrower referrals can replenish it—new leads must continue to be generated through other less effective channels.The Loan Application Process In economic terms the loan application process represents an investment at origination with the aim of minimizing credit losses in the future. All else being equal a greater investment in the credit application process will result in lower subsequent rates of delinquency and default conversely a less stringent process would result in greater rates of credit loss in the future. Setting the appropriate level of rigor in acredit application process is an exercise in analyzing loan applicant characteristics and forecasted future behaviors while being cognizant of thecost of performing these analyses.Three steps characterize the loan application process. Preliminary Screen. The applicant is asked a short set of questions to establish th e applicant’s eligibility for credit under the MFI’s guidelines. This is sufficient todetermine the likely strength of an application and whether an offer of credit could inprinciple be extended. Interview. At the interview stage due diligence is performed to ensure that theloan purpose is legitimate and that the borrower’s business has sufficient capacity andprospects to make consistent repayments. Cash-flow analysis is the core of the MFIdue diligence procedureand for microfinance borrowers the data is often insufficiently formal hindering easy examination of cash flow stability and loan payment coverage. As a result this is a less standardized more timeconsuming task than its equivalent in the formal lending markets. Underwriting and Approval. If a loan is recommended by an officer followingthe interview the application is then stress tested by an underwriter who validates thecash flow and performs auxiliary analysis to ensure that the loan represents a positive addition to the lending portfolio. The dynamics of loan origination illustrate the trade-offs to be made to ensure anefficient credit process. Improved rigor could lead to a higher rate of declined applicants and so higher subsequent portfolio quality but at the expense of increased processing costs. For medium and larger loans as application costs increase past an optimal point the marginal benefit of improved portfolio quality is outweighed by them arginal expense of the credit application itself. However for small loans there exists no such balance point—the optimal application cost is the least that can be reasonably achieved. This motivates a less intensive credit application process administered when a loan request falls beneath a certain threshold typically a principal less than 5000. MFIs can disburse such loans more quickly and cheaply by fast-tracking them through a transaction-based process and context learning.Loan Monitoring Post-loan monitoring is critical toward minimizing loss. In contrast to the credit application process which attempts to preempt the onset of borrower delinquency by declining high risk loans monitoring efforts minimize the economic impact of delinquency once a borrower has fallen into arrears. In addition to the explicit risk to institutional equity through default managing delinquent borrowers is an intensive and costly process. When dealing with repeat clients there exists the opportunity to lever age information captured through monitoring on previous loans enabling the MFI toshorten the full credit application without materially impacting the risk filter. In short there is an opportunity to reduce operational costs without a corresponding increase infuture loss rates. Repeat borrowers enable the information accrued during therelationship to be leveraged to mutual benefit of MFI and borrower. In this case muchof the information required to validate a loan application has been gathered during theprevious lending relationship. An MFI will also possess the borrower’s paymen this tory a more accurate indicator of future performance than an isolated financial snapshot taken during the standard application process. The challenge however isthat for many MFI a part of their mission is to graduate customers into mainstream commercial banking which would not allow the MFI to collect additional interest payments from those customers.Overhead Costs For an MFI to sustain itself each outstanding balance must contribute aproportional amount to institutional costs. Institutional costs are driven primarily bythe size of the portfolio being maintained. The necessary staff tools technology work environment and management are functions of portfolio scale. We outline in Table 2 t he institutional level costs of five MFIs with varying portfolio sizes to identify the proportional cost loading necessary to guarantee that central costs are compensated for. The table shows that institutional costs increase at as lower rate than the rate at which the loan portfolio grows so that the overhead all ocation declines as an MFI achieves scale. We find that an MFI with a 500000portfolio will incur indirect costs of 26 percent while an MFI with a 20 million portfolio will experience a much lower indirect cost loading of 6 percent. In theUnited States the largest institution engaging solely in microfinance presently has aport folio of 15 million.3.Discussion and ConclusionsContinued subsidization of credit also has implications for the long-term sustainability of MFIs. Our high-level analysis of projected self-sufficiency levels ofvarious MFI sizes shows theimportance of pricing appropriately. Even a modest deviation from the value-neutral price has a significant impact on the amount of subsidies needed to sustain the institution. As a consequence it is imperative that MFIs rigorously analyze the true costs and review their pricing structures accordingly. It has yet to be demonstrated that microfinance can be performed profitably in the United States. Nondepository MFIs may not have better information and/or echnology to identify and serve less risky microbusinesses than formal institutions. Itwould therefore appear that formal institutions are acting rationally in choosing not toserve this market at present. However MFIs have succeeded in channeling capital to crouinesses. Still MFIs often operate with certain public and/or private subsidies.Ultimately more research is needed to ascertain whether the provision of microfinance offers a societal benefit in excess of economic costs. This paper is oneof the first to document a very wide dispersion in the difference between value-neutral and actual pricing for a sample of MFIs. This suggests a wide dispersion in theeconomic subsidies inferred by these MFIs. More specifically these subsidies are notbeing allocated on a consistent basis. If subsidies are required to serve the market at palatable interest rates for lender sand borrowers it is incumbent on the microfinance industry to demonstrate that theirs is an efficient mechanism for delivering such subsidies. Once a subsidy is justified institutions must be motivated to improve their operational efficiency so that they may offer microfinance borrowers the lowest possible equitable prices while not jeopardizing institutional viability.外文题目:The Question of Sustainability for Microfinance Institutions出处:Journal of Small Business Management 2007 451 pp. 23–41.作者:J. Jordan Pollinger John Outhwaiteand Hector Cordero-Guzmán。

文献出处:Dietrich A. The Research of Small loan Company Credit Risk [J]. Small Business Economics, 2015, 8(4): 481-494.原文The Research of Small loan Company Credit RiskDietrich A.AbstractMicrofinance is pointing to the tiny enterprises or individual enterprises provide credit service, small loans basic characteristics for the process simple, amount of small, unsecured, etc.The emergence of small loan companies before fill in the blank of traditional financial institutions, to ensure the development of small and medium-sized enterprises and individual enterprises need. However, due to the particularity of micro-credit Company itself exists, there are many deep level problems to be solved. Such as capital source, interest rate limits, etc., especially the credit risk control problem. Credit risk is the main risk facing microfinance institutions. Quality was monopolized by the original financial institutions, loan to customers rely mainly on credit personnel subjective judgments, the weakness of the service object group, partly due to the scarcity of high-quality professionals, in the specific operation and operation on the face of the numerous credit risk. Microfinance is a small loan company's core business, loan assets are an integral part of its assets, loan income is the main income, and credit risk will lead to microfinance institutions to produce a large amount of bad debts will not be repaid, will seriously affect the quality of credit assets. Previous management, risk management is equivalent to afterwards that the understanding for the loan risks management of collection, the processing of bad loans, etc.Practice has proved that this approach will only increase operating costs, and late is no guarantee of the company's asset quality. Risk control is the key to identify risk, credit risk is the main source of customers, choose good customer credit conditions at the time the loan is helpful to reduce the probability of credit risk. Therefore, we should from the source to control risk, when choosing loan customers, carefully screening customers, for customers to make the right evaluation. Key words: small loans; Credit risk; Prevention mechanism;1 IntroductionThe rise of small loan companies, making the private capital to enter the small loan companies, great convenience is provided for the small and medium-sized enterprises and individual industrial and commercial households.Microcredit in absorbing private capital at the same time, broaden the financing channels. As a legitimate financial intermediation, enriched the organization form of the financial system. It also makes a lot of in the "underground" sunlight to folk financing mechanism; standardize the order of the financial market financing. Small Loan Company’s gradual development, make it’s become important force in the future diversified financial market.Small Loan Company since its establishment, has been for many small and medium-sized enterprises and individual industrial and commercial households offers a wide range of financial support, guarantee the good operation of the economy. However, small loans company also has a lot of problems. First of all, according to the small loan companies operating conditions, the management mode for the "credit not only to save”. Can’t absorb deposits, which are also the biggest different microfinance companies and Banks. So its sources of funding are mostly shareholder investment and bank lending. This leads to the size of its capital is limited by great, when it comes to an amount loan amount, small loan company's business is difficult to maintain. Second, the small loan company's clients are difficult to loan from the bank's clients, in this high quality customer was monopolized by the traditional financial institutions, small loans company greatly increase the credit risk. Because we can not from the credit status of customer credit systems, company surveys every loan applicants need to spend a lot of time and energy. Finally, small loan company's products are mostly unsecured, completely by customer credit loans, which accelerate the speed and efficiency of the loan, but at the same time, the company's capital safety not guaranteed, when customer default, can calculate the loss of the company. These weaknesses can require small loan companies from the source to control risk, makes every effort to do it by reducing the credit risk to the minimum.In the process of field research, small loan companies do better on the credit riskcontrol, but also the above problems. Therefore, combined with the characteristics of small loan companies, a set of accord with the actual situation of the simple and easy to use credit evaluation system, through analyzing the characteristics of the default customer, for new loan customer default probability for effective judgment, control and reduce the risk of credit business is the main problems of small loan companies are facing at present stage.2 The necessity of research on theBased on the principle of small loans and related theory, under the guidance of conduct empirical study of Microfinance Company, through analysis of the situation, credit risk has the following practical significance:2.1 Promote microfinance company better risk controlExisting micro credit company risk control relies mainly on the subjective judgment of executives and the loan officer, lack of professional assessment of risk and risk management system, the risk is the intrinsic attributes of financial activities. For microfinance companies the special financial institutions, can effectively control and manage risk, related to the sustainable development of small loan companies can. Small Loan Company’s ultimate goal is profit, improve risk management, and help to reduce non-performing loans, to ensure the safety of the assets of the company, so as to realize the sustainable development of small loan companies.2.2 To perfect the existing financial system of risk controlTraditional financial institutions attach great importance to risk control, the state-owned commercial bank's risk management and internal control are better, on the basis of legal, effective and prudent, set up a specialist team of risk assessment methods. Such as 0, the agricultural bank of China credit rating for business customers, eventually will be divided into enterprise credit grade AAA, AA, A, B, C five grades, China construction bank efficacy coefficient method is used to determine the score, to measure the customer credit risk size, as according to the judgment of borrowers credit risk condition, and issuing different credit lines to different customers.3 Small loans company credit riskMicrofinance company time is not long, data is not complete, so dedicated to small loans of credit risk assessment model is less, because small loans business and loan business of commercial Banks and other financial institutions to traditional similar, so we can draw on the experience of credit risk assessment model of commercial Banks. In the context of index selection, developing countries believe that the most predictive power of microfinance credit risk assessment indicators are: customer own characteristics: age, gender, number of family members, etc;Family or corporate financial data; Loan characteristics and the status of the default in the past. Schreiner (2004) also think that risk is associated with the characteristics of lending institutions, such as the loan officer's experience and branch loan situation. n addition, policy changes, seasonal factors will have an effect to the default. In terms of developed countries, the evaluation index and the developing countries, James Copes take said (2007) through the questionnaire results showed that age, gender, household assets and labor quantity is the determinant of small loans to repay. Italian commercial Banks selected the explanatory power of higher indicators are: personal characteristics: the borrower characteristics and borrowing record; Business features: inventory, number of employees, revenue expenditure, etc; Other features: real estate properties, the current address live time, etc.3.1 Small loans company credit risk definitionCredit Risk (Credit Risk), also known as default Risk, refers to the borrower fails to carry out obligations in the contract within the prescribed time, the possibility of economic loss caused by small loans company. Specifically, the borrower may change because of its environment and cause credit conditions are poor and cannot afford the rest of the loan repayment, or false application materials when apply for a loan, get loans from microfinance company after not getting paid on time. The above conditions will lead to small loans company actual earnings deviating from the expected return, serious when still can cause company losses, credit risk has always been a traditional financial institutions risk, is also the main risk. According to the study, carries on the comparison to all kinds of risks, credit risk has the highest proportion, is considered to be all the factors which lead to debt repayment, thebiggest. This makes the credit risk control important. Small Loan Company profits from customers, but the company the biggest risk comes from the customer. From the causes of credit risk, mainly including: to understand the borrower's information is not complete, no accurate judgment to the borrower's credit status, colluding with collusion between the loan officer and the borrower, the loan examination and approval is not strict, a lack of understanding of customer credit situation, accredit risk arises from the whole process of lending, any mistakes will cause credit risk.3.2 Small loans company forms of credit riskMicro-credit companies are facing the credit risk is the main form of borrower default, delinquent loans, resulting in the delinquent loans, bad debt loss and etching order to prevent and reduce the possibility of loss, make. To minimize the loss, it is necessary for us to study on specialized default. Default refers to the borrowers did not follow the stipulations of the contract, within the prescribed time limit; pay off the loan, thus making the loan payments or delinquent loans. Different microfinance firm definition of default is not the same, if some agency interpret default loans for any overdue payment loans (American education to promote small business network, SEEP), also some think a loan is a loan default or delay paying behavior refers to the returned overdue loans. Specific how long overdue is recorded as the default; in practice of microfinance company is diverse.4 Prevention mechanism to reduce the credit riskThrough analysis, we believe that the individual situation, operation stability, loan borrowers credit records and other factors associated with small loans company customer credit risk, through the empirical study of small loan companies, we also found that good credit score model can help the loan officer found good potential defaulters, in view of the above situation, we put forward the following countermeasures.4.1 Starting from the customer, the establishment of customer resource filesFrom the article analysis shows that any risk assessment model is the basis of data collection, the role of the model is to extract important information from a large number of customer information, and according to the customer's payment tocustomer classification, and data collection is in accordance with the information provided by the customer. Make full use of by the customer, the information provided by the customer bank running water, such as accounts receivable bills for the record, and is an important factor analysis customers repay ability. Establish the borrower repayment ability analysis system, through to the borrower can bear the liabilities of the biggest limit the ability of analysis, control the loan amount and duration of the borrowers, in helping borrowers through financing difficulty, development business at the same time, reduce the loan funds transferred or misappropriate possibility, greatly reduce the occurrence of bad loans.4. 2 Establish and constantly improve microfinance credit reporting databaseBased on field research shows, small loan companies, now of small loan companies can only rely on the loan officer to spend a lot of time and energy to investigate the credit status of customers. As a result of the existence of moral hazard and adverse selection, there is a big risk of small loans to the company's business, if small loan companies can enter the credit reporting system for customer's credit standing, you can quickly understand the customer's information, speed up the lending, at the same time, saving manpower and financial resources, reduce the cost of operation.4. 3 Choose reasonable and scientific credit evaluation modelField survey found in small loan companies, petty loan company's risk management department is research and development of "score CARDS", the so-called "score card", is to report according to the customer manager of customer's basic situation, through certain technical means, the overall customer risk scores. The customer the higher the score, the more performance rate, the lower the score, the more possible risk of default. At present this technology for unsecured customers only, because this part of the customer is the biggest customer base, and because there is no collateral, so the risk is bigger. Unsecured customer loan program is relatively simple, the use of "score CARDS", can quickly determine the client's credit standing, making lending more convenient.译文小额贷款公司信用风险研究Dietrich A.摘要小额信贷是指向微型企业或个体经营户提供额度较小的贷款服务,基本特征为流程简易,额度较小,无抵押等。

外文翻译原文Micro Credit in Chiapas, Me´xico: Poverty Reduction Through Group ending Material Source: Journal of Business Ethics, September 2009, V olume 88, Supplement 2, p283-299, DOI: 10.1007/s10551-009-0286-7;Author: Gustavo Barboza and Sandra TrejosIntroductionGeorge Akerlof (1970) brought the issues of asymmetric information and moral hazard (adverse selection) to the forefront of economic theory.While Akerlof relies on the example of the used car market to illustrate the existence of such informational problems, asymmetric information examples are found in everyday life situations, including the functioning of financial markets. In general, riskier borrowers pay higher interest rates to compensate for their higher probability of default, whereas safer borrowers pay lower interest rates. Financial markets use credit ratings to assess the borrowers’ probability of default and therefore, determine the corresponding interest rate to be charged. Collaterals, such as leans on cars or mortgages on land property, secure the loan in case of default. When neither collateral nor credit rating is available, no lending takes place. The lack of collateral or credit ratings inhibits the ability of financial institutions to internalize possible information asymmetries, and limits the prospects for economic activity to develop.Unfortunately, the above-mentioned scenario describes the reality of about half of t he world’s population. The lack of credit rating and/or collateral leaves about two to three billion people with no access to formal credit markets. They are unable to obtain loans for economic activities. This lack of access to financial markets is a major problem when trying to reduce poverty around the world.The 2006 Nobel Peace Prize2 was awarded to Mohammed Yunus and the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh for their pioneer work on developing Micro Credit3 (MC) as a method to reduce poverty through the provision of financial resources to the poorest of the poor. MC programs have emerged in many countries and are aviable option for people with entrepreneurial skills and promising business projects. Under the new organizational model, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) managing MC programs receive financial support from donors, grants, or borrowed money from international organizations at preferential interest rates4 (sometimes interest rate free), to then lend to impoverished people. These programs bridge the gap between no access to financial markets and institutions, and one-time lump sum government aid programs.Poverty and Micro-creditThe recent rise of Micro Credit is a direct response to the failure of the formal financial markets to include the poor as different and unique economic agents. Governments have tried to improve this market failure by providing lump sum aid. But this solution does not correct the situation in which the poor lack access to loan funds. In the early 1970s,Mohammed Yunus initiated the Grameen Bank project, an MC program that provided small loans for poor people who lacked collateral. The Grameen Bank currently has similar and derived programs operating around the world. MC is an innovative approach to lend financial resources to the poor, without making use of collateral, by creating a network of trust where families, neighbors, friends, or even strangers come together to support each other financially. MC programs focus on the poorest of the poor, those that are shunned away from formal financial markets opportunities.How do MC programs work? MC programs receive financial support from socially responsible donors and international organizations because of their positive impact on poverty alleviation while promoting economic development. Financial viability of MC programs is crucial to continuing the provision of resources to those in the lowest income bracket. Achieving and consistently maintaining high repayment rates on outstanding loans is, hence, central not just for survival of the organization, but to achieve the goals of dissemination of wealth and integration into modern society. Alternatively, low repayment rates or high delinquency on outstanding loans would most likely create an adverse effect on the willingness of donors to support MC programs.MC programs are tailored to the specific needs of the clientele they target. For instance, some programs focus on urban areas and provide financial resourcesexclusively to the poor. Other MC programs concentrate their operations in rural areas, and provide access to financial resources and related services, such as educational programs and health services. Furthermore, some programs use the individual group lending model, while others lend to groups, or lend money individually under joint liability contracts. The unifying factor of these programs is that their final goal is to lift the poor out of poverty, not through charity, but through the efficient use of scarce resources and the development of feasible entrepreneurship projects that allow the borrowers to use their capabilities towards reaching their potential. In this regard, some programs, such as BancoSol, are defined as for-profit organizations, while most others are operated by NGOs with a clear non-profit status.The empirical results of MC performance and impacts are generally very impressive. According to the United Nations’ High Level Event fact sheet,65% of all Grameen Bank borrowers ‘‘have managed to lift themselves out of extreme poverty.’’However, there is still work to do given that a great proportion of people around the world still live on less than $1.25 a day (purchasing power parity in 2005 prices). Using this threshold, the World Bank estimates from August 2008 reveal that 1.4 billion people live in extreme poverty.Perhaps the best known MC program in Me´xico is Compartamos, which is active in over 26 Mexican states and provides services mainly to rural borrowers. Compartamos, like many other MC programs, lends mostly to women, though recently its services has been extended to men. Compartamos is one of the first MC institutions to be listed on the Mexican Stock Exchange and it became a commercial bank in 2006 (Sengupta and Aubuchon, 2008). However, Compartamos is different from most MC programs because MC programs operate at a much lower scale than the former.Very little research has been conducted on the impact of MC programs on poverty in Mexico. One Micro Credit in Chiapas, Me´xico 285 study reports that people who have been microfinance clients for more than one year are financially better off than new clients (Woodworth and Hiatt, 2003). The study reported that nonclients earned only $1.69 a day and 22% of the nonclients earned less than $1 a day. MCs offer these poorest of the poor a clear and feasible alternative that is already yielding positive effects for those in most need.A model of Micro-credit lendingFirst, lenders can either loan money directly to borrowers or use a financial intermediary. According to Prescott (1997), lending to the financial intermediary, under the riskier return projects, is the optimal solution for individual lenders. The main reasons are the high monitoring, screening, and administrative costs that the lender would have to incur to secure a full repayment. The financial intermediary has a comparative advantage in these regards (Prescott, 1997).Second, lenders can provide individual loans,group loans, or individual loans under group joint liability.Third, lenders can lend without monitoring but with liquidation, lend and monitor, or lend to groups and have them self-monitor.Fourth, MC institutions lending to small borrowers also need to consider private information on borrowers’ returns, liquidation costs, costly monitoring, and costly screening (Prescott, 1997). The existence of private information on the borrowers istypically unknown, which is one of the reasons why formal financial markets do not to lend to poor people. Borrowers can lie and claim bad performance which the lending institution is not able to verify. Finding mechanisms to ameliorate the existence of private information is the first task for the lending institution, both from the generation of revenue perspective and the use of funds to guarantee high repayment rates. The selected mechanisms will, in turn, dictate the lending approach,loan structure, and corresponding cost structure on the MC lending institution side.Fifth, the operating mechanisms of MC institutions preclude them from receiving direct deposits from savers.Sixth, loans from socially responsible lenders and donors, and other financial resources from donors,can be used either to lend to borrowers or to cover administrative expenses. The most common practice is for socially responsible lenders and donors to earmark that the money be allocated for specific uses.MethodologyOur objective is to provide empirical evidence on poverty reduction, repayment rates, and group dynamics to determine the role that donors can play in assuring thefinancial viability of MC programs. To determine the impact MC programs have on poverty alleviation, repayment rates, and approximate overall program sustainability were estimated using data from the ALSOL Micro Credit Program in Chiapas, Me´xico. The official transaction records of weekly payments were examined from July 2000 to July 2001 for a total of 2151 participants.ALSOL provides loans to urban borrowers at a 30% flat interest rate and rural borrowers at a 20% flat interest rate. Under the progressive loan structure, loans are given out in six levels. Borrowers move to the next loan level upon successful completion of the previous loan.FindingsThe findings reported below are organized based on the following analysis: (1) overall loan sample, (2) active loans versus inactive loans for the overall sample, (3) rural loans versus urban loans for the overall sample, (4) active rural loans versus active urban loans, (5) inactive rural loans versus inactive urban loans, (6) active loans by region and level, and (7) inactive loans by region and level.Overall loan sampleThere were significant weekly variations in loanrepayment patterns. Figure 1 indicates that ALSOL Micro Credit has overall weekly loan repayment rates ranging from a low of 84% (just prior to 9/1/00) to a high of 98% (shortly after 12/10/00), for the period July 2000 to July 2001. Multiple factors can explain this variation: differentiated learning-bydoing process between urban and rural settings, drop outs of poor performers, early cancellation of loans,recomposition among overall rural and urban participants,and relative loan structure recompositions.These elements represent the group dynamics that are inherent in an MC program in the form of peer monitoring, assortative matching, and response of program participants to a given set of dynamic incentives.Figure 1. ALSOL program performance in actual to expected payments.Active loans versus inactive loans for the overall sampleIn the case of active participants (see Figure 2), the lower performance numbers,Figure 2. ALSOL Micro Credit performance of active and inactive loans.relative to inactives,can be attributed to the prevalence of loans that decided to remain in the program as of July 2, 2001despite having a history of arrears (repayment difficulty).For inactives, the relative average performanceincludes two different types of participant groups: (1)women who paid off the loan in full many weeks ago anddecided not to receive a new loan and (2) women who received a loan recently and paid it off in less than 50 weeks. We also identified 21 defaulted cases.Rural loans versus urban loans for the overall samplePerformance differentials are more evident when a rigional specific classification is considered (see Figure 3) For instance, the evidence indicates positive difference in performance in favor of urban women over rural women. On average, urban women had stronger, and more consistent, performance.Urban loan performance, compared to rural loan performance, is closer or above the number one for a larger number of observations. Rural participants display more arrears in the loans, with an overall difference of about 15% for overall program,compared to 10–12% for actives.Figure 3. ALSOL rural and urban loan performance.ALSOL provides economic incentives to rural participants by charging a lower interest rate in comparison to urban loan. This incentive attempts to enhance the likelihood of repayment for rural participants,as it is assumed that they have a more difficult time accessing markets to sell their wares. The results in Figure 3 tend to suggest that the market conditions are indeed more difficult for rural participants. Two key factors come to play in this regard: (1) cash flows are not generated on a daily basis, and (2) the larger physical distance from markets makes it more difficult for these entrepreneurs to interact with consumers and obtain information about market performance. The combination of these elements results in greater difficulty to make payments on a weekly time schedule.A derived issue from the difficulties encountered rural participants is the slower advancement made along the progressive loan ladder. As rural participants are unable to generate a strong and consistent cash flow, their borrowing capacity is proportionally hindered because they are unable to repay as much as fast.Active rural loans versus active urban loansTo further understand the dynamics of repayment patterns, we analyzed the Active/Inactive categories by regional classification. Active urban loans carry relatively low arrears and tend to perform ahead of schedule (see Figure 4). The significant positive performance of active urban loans supports the assumption that projects with higher expected returns have lower levels and frequency of arrears. These require a lower need for peer monitoring and represent an overall reduction in monitoring and administrative costs to the lending institution. Active rural loans, despite displaying an upward trend on repayment rates, do not catch up with those of the urban participants.Figure 4. Active urban and rural loans.Inactive rural loans versus inactive urban loansSimilar patterns of behavior are observed in the inactive classification when dividing the groups into urban and rural categories (see Figure 5). Inactive urban participants tend to outperform inactive rural ones. The difference in performance, however, is not as strong as before. Indeed, during the period between July 2000 and January 2001, rural participants show a considerable improvement in repayment rates and catch up with the performance of urban loans several months into theanalysis.Figure 5. Inactive urban and rural loans.For rural participants this period corresponds to a significant number of cancellations on highly delinquent loans, which results in an improved overall performance. The catching up effect disappears as rural participants increase the number of arrears during the first half of 2001, because the remaining inactive rural loans continue to accumulate arrears. On the other hand, the inactive urban participants show a strong tendency towards early loan payments. The performance of inactive rural loans present a tendency to worsen as many loans are not cancelled and become inactive after accumulating more than 25 weeks without activity. Active loans by region and levelThe tendency of active urban loans to outperform active rural loans is consistently present at all loan levels (see Figures 6 and 7). Active urban loans have a strong tendency to be ahead in terms of payments with a low incidence of arrears. For rural loans, no single category of loan level has a performance indicator equal or greater than 1.Figure 6. Active rural loans by level.Figure 7. Active urban loans by level.Active rural loans by levelActive rural loans display a significantly differentiated performance when classified by level (see Figure 6).First level loans strongly pull down the overall performance. Performance at the first level is always below the average for the overall rural program,which indicates that there are differences associated with newcomers into the program compared to groups and centers that have acquired relevant business experience as they move up in the progressive loan structure.Even within the first loan level, there are distinctive patterns related to learning and improved performance as participants mature on their loans.This suggests that incentives positively affect behaviors. The poorer performance of the active rural first loan level is explained by those that are at the verge of strategic default. Out of a total of 320 active rural first loans, 26.25% are at high risk of default; for 161 second loans, 36.02%; and for 108 third loans, 20.37%. None of the 28 fourth loans are at high risk of default.Active urban loans by levelFigure 7 illustrates the existence of a considerable degree of convergence towards optimal performance for active urban loans. It is of particular relevance that the reduction in the overall variance and the coherent movement of most all categories are in the same direction. Even in the lowest level of performance towards the end of the period, the maximum level of arrears does not exceed 4–5%.Without doubt the active urban participants outperform the active rural ones in many regards.Repayment rates are better, the number and frequency of arrears are much lower with a strong tendency to be ahead of schedule, and there is a faster repayment of loans reinforced by consequently faster upward movement along the loan ladder. In addition, even though there is some small degree of variation in the time trend performance, there is also enough evidence to suggest that all categories tend to move toward the same level of performance for active urban centers.Why? Easier and prompt access to the market translates into a better and more stable cash flow that allows better repayment rates and fewer arrears on average. In addition, a higher return on economic activities is promoted by access to credit, resulting in successful business ventures. Access to credit through MC materializes those economic opportunities urban people have been developing that are economically feasible. This further promotes entrepreneurship development. None of these opportunities could have been propelled to the current status if borrowers relied on access to credit from formal markets.Inactive loans by region and levelAs indicated in Figures 8 and 9, the same general impressions made about active loans apply to Figure 8. There is a difference in magnitude of effects, but not in direction. The same basic structural factors affect both inactive urban and rural participants, but each region has identifying factors that ameliorate their respective performance. Further analysis of the inactive records indicates that the inactive urban loans are more consistent on their performance of repayments, havingsignificant low arrears and, in general, perform ahead of inactive rural loans.Figure 8. Inactive rural loans by level.Figure 9. Inactive urban loans by level.Comparing the degree of arrears of inactive rural loans suggests that these loans maintain a much better record of payments than active rural loans.On the other hand, urban participants, both active and inactive, have relatively comparable performance indicators that appear at first glance not to be correlated with the active/inactive classification. However, this tendency changes towards the end of the period of analysis when inactive rural loans start presenting a significant deterioration as theaverage number of arrears increases. This is particularly significant when one considers that the inactive urban participants considerably improved their performance, remaining ahead of schedule at about 8% for most of 2001.There are several possibilities for the significant performance divergence. First, from a purely statistical point of view, basic indicators for urban participants tend to have a more consistent pattern of repayment. Second, given that the number of urban participants grows faster than rural participants, the overall performance in the urban sector is more dynamic. Thus, instead of being associated with higher risk, the higher returns may be associated with better opportunities and ability of urban participants to use MC incentives.ConclusionsMicro Credit programs are a viable alternative for those in the lowest income bracket. A combination of available funding through socially responsible lenders and donors, and individual lending under joint liability, allows for significantly high recuperation rates on outstanding loans. The ALSOL Micro Credit in Chiapas, Me´xico case study shows that this new organizational approach, through the provision of financial resources to those considered unbankable by the formal financial system, can successfully achieve and maintain high recuperation rates. This, in turn, translates into opportunities for participants to migrate out of poverty.MC programs provide opportunities to poor people and their families in ways that the market fails to address. MC programs also fill empty holes left by market imperfections incapable of assimilating the existence of asymmetric information. These gaps in market functioning, due to the market’s inability to effectively account for private and asymmetric information, create severe and persistent problems for those less fortunate.Poverty alleviation is a persistent challenge requiring immediate attention. Spreading the goodness of access to the market is one form to address this problem. The research reported in this article suggests six implications for poverty reduction.First, contrary to common beliefs held by many formal lending institutions, the poor are capable of borrowing money, developing successful entrepreneurship ideas, making regular repayments, and successfully completing a full lending–borrowing cycle.Second, while formal lending markets fail to incorporate those in most need because of the existence of asymmetric information between lenders and borrowers, MC programs are able to bridge these differences and provide real opportunities toward poverty alleviation.Third, the existence of market imperfections precludes the poor from participating in resource allocation efficiency gains markets provide. Yet, access to markets benefits, precisely, the poor the most. At the margin, an increase in income has a much larger positive effect at initial low levels of income.Fourth, MC programs and full access to market participation complement each other. Differences in performance across urban and rural participants – in favor of the former – indicate that urban borrowers have better access to markets where they sell their wares. This allows urban borrowers to complete the borrowing cycle faster, progress to higher loan levels faster, and consequently escape away from poverty more rapidly.Fifth, despite the impressive performance of MC programs, administrative costs remain high. Continuous financial support from socially responsible lenders and donors is still in much need to secure a long-term positive effect on program development and consequent poverty reduction until an MC program reaches sustainability.Lastly, further research on the overall impact of MC programs is needed. Some issues of interest that remain unresolved include: overall MC program sustainability, actual extent of poverty reduction in Latin America derived fromMCprograms, incidence of social mobility because of MC programs, and inner group dynamics under non-collateralized borrowing.译文小额贷款在帕恰斯,墨西哥:通过集体贷款减少贫困资料来源:商业伦理[J].2009(9), 88卷,附录2, p283 – 299.作者:古斯塔沃·巴尔沃萨,桑德拉·特雷霍斯引言George Akerlof (1970)把信息不对称和道德风险(逆向选择)的问题推到了经济理论最前沿。

小额信贷FAQ小额信贷FAQ【什么是小额信贷】小额信贷指为低收入阶层提供小额度的持续的信贷服务活动,包括贷款、储蓄和汇款等多方面的金融服务,是一种基于接受贷款者信誉的无抵押和担保的小额度信用贷款。

传统意义上的贷款都需要抵押或者担保,因此只能惠及有一定经济实力的客户,不能帮助因为贫困而难以提供抵押和担保的穷人。

目前国内有些金融机构宣称自己从事小额信贷,实际上其准确定义应为小额贷款——额度是小的,但需要担保或者抵押的贷款,从这个精确定义来看,目前中国小额贷款比小额信贷的覆盖面要高。

不过在大多数场合,“小额信贷”和“小额贷款”这两个概念混淆使用,区别并不明显。

【小额信贷的发展】真正意义上的小额信贷起源于孟加拉国,由该国吉大港大学教授穆罕默德·尤努斯与20世纪70年代创立,他也由此被誉为“小额信贷之父”,并获得了2006年的诺贝尔和平奖。

随后,亚洲和拉美的一些国家借鉴孟加拉国乡村银行(Grameen Bank)的经验,并结合国内民间借贷的特点,创建了多种形式的小额信贷模式。

截止2005年底,全球共有超过1亿1300万客户受惠于小额信贷。

其中,有9670万在亚洲,740万在非洲,440万在拉丁美洲和加勒比海。

从国家的范围来看,孟加拉国的小额信贷覆盖率最高,覆盖了75%的贫困家庭,世界上31%的大项目都出自孟加拉国。

·在中国的发展按照上述小额信贷的定义,中国的小额信贷真正开始于1993年,中国社会科学院农村发展研究所在孟加拉乡村银行和福特基金会的资金和技术支持下,引进孟加拉乡村银行的“小组模式”,在河北易县成立了第一个扶贫经济合作社。

随后,各种国际援助和贷款进入,以半官方或者NGO机构的形式开展小额信贷在中国的探索。

随着小额信贷取得了一定成果,其重要作用被政府认可,中国政府从资金和人力方面对小额信贷进行推动,作为实现消除贫困目标的重要手段。

从2000年开始,农信社全面试行推广小额信贷,成为当前小额信贷的主力军。

金融机构通用名称英文译法汇总(银行)1 银行 Bank2 农村商业银行 Rural Commercial Bank3 邮政储蓄银行 Postal Savings Bank4 分行 Branch5 支行 Sub-Branch6 24 小时自助银行 24-Hour Self-Service Banking(保险)1 保险公司 Insurance Company2 财产保险公司 Property Insurance Company3 人身保险公司 Personal Insurance Company4 人寿保险公司 Life Insurance Company5 再保险公司 Reinsurance Company(证券、期货)1 证券公司 Securities Company2 证券交易所 Stock Exchange3 证券投资基金管理公司 Securities Investment Fund Management Company4 期货公司 Futures Company5 期货经纪公司 Futures Brokerage Company(贷款、融资、投资)1 贷款公司 Loan Company2 小额贷款公司 Micro-Loan Company3 典当行 Pawn Shop4 拍卖公司 Auction Company5 拍卖行 Auction House6 信托公司 Trust Company7 信托投资公司 Trust and Investment Company8 投资咨询公司 Investment Consulting Company (财务管理及其他)1 财务公司 Finance Company2 货币经纪公司 Money Brokerage Company3 金融控股公司 Financial Holding Company4 金融资产管理公司 Asset Management Company5 金融租赁公司 Financial Leasing Company6 汽车金融公司 Automobile Finance Company7 消费金融公司 Consumer Finance Company (功能设施)1 客户等候区 Customer Waiting Area2 咨询引导区 Consulting Area3 现金服务区 Cash Service Area4 理财专区 Wealth Management Area5 网银体验区 E-Banking Experience Area6 自助服务区 Self-Service Area7 自助取号机 Queuing Machine8 现金快速通道 Deposit and Withdrawal Counter9 填单处 Form Filling Area10 自动存款机 Cash Deposit Machine11 自动取款机 ATM12 智能柜员机 Smart Teller Machine13 自助缴费机 Bill Payment Machine14 客户服务电话 Customer Service Hotline(营业信息)1 24 小时自助服务 24-Hour Self Service2 节假日营业时间 Public Holiday Opening Hours3 星期六、日休息 Closed on Saturday and Sunday4 节假日不办理(不营业) Closed on Weekends and Public Holidays5 业务办理时间 Business Hours6 理财咨询时间 Wealth Management Consulting Hours(业务信息)1 对公业务(企业银行服务) Corporate Banking2 VIP 服务 VIP Service3 现金业务 Cash Counter4 理财服务Financial Planning Service 或 Wealth ManagementServic(自助服务)1 操作指南 Instructions2 设备维修,暂停使用 Machine Under Repair3 本机每笔最大存款张数:____ Maximum of ____ Bills at One Time4 请输入密码 Please Enter Your Password5 磁卡插口 Card Slot6 存款口 Cash In7 凭条口 Receipt8 取款口;出钞口 Cash Out9 条码扫描口 Barcode Scanner10 账单出口 Bill Out11 自助服务终端 Self-Service Terminal12 活期存款账户 Demand Deposit Account13 账户余额查询 Balance Inquiry14 跨行转账 Interbank Transfer(服务人员名称)1 大堂经理 Lobby Manager2 理财经理 Wealth Management Adviser3 柜员 Teller。

本科毕业论文外文翻译外文题目:Italian Banks’ Credit Approach Towards Low-Income Consumers and Microenterprises:Is There a Bias Against Some Segments ofCustomers?出处:New Fronties in banking services,part3,pages299-321.作者:Eliana Angelini译文:意大利银行对低收入消费者和小型企业信贷方针:对某些客户是否存在信贷偏见?在意大利,银行对低收入消费者的感性和微型企业的金融需求的认识似乎仍然相当有限。

低收入客户包括受薪雇员,农民,退休人员,使用临时占用(非典型工人)或失业人士,家庭主妇和移民的年轻人。

Microenterprices,在任何经济运作中最小的经济单位,包括自雇人士,以及家庭经营的企业。

包括从街角的杂货店的裁缝,他们工作在几乎所有的经济部门。

而这些环节的金融需求与其他企业和消费者相比,他们有着个人和业务特点,以及其业务的相对规模,分歧也是明显的。

具体来说,微型企业和其他低收入客户往往经营的属于正规经济和社会经济的边缘,有着频繁的没有必要的许可证和文件。

企业和住户一般只有有限的资产,特别是缺乏有正式头衔,可作为传统的固定资产抵押。

虽然纯收入都在较低的规模,但以百分比计算的微型企业的经营利润率可能会很大。

销售费用和收入的正式记录是稀缺和不可靠的。

企业和家庭混有财务是从多个企业,农业和农业生产活动等各种渠道获得的收入。

访问客户是这部分信贷的一个共同问题,而且往往在发展中国家尤其严重。

有很多原因这包括成本和信用评价的难度。

这些客户,通常被定义“边缘”,往往造成评估和监控信贷风险的具体问题。

贷款被认为是“脆弱”的客观特征,作为一个例子,与以借款人偶然从实践活动或主观方面的特征联系在一起。

银行使用的信用评分模型来产生关于借款人的偿还贷款倾向的信息。

小额贷款公司分析报告范文我们对小额贷款业务开展了前期调研,就国内小额贷款公司的政策环境、发展态势、运作模式和风险控制等方面进行了调研,提出了设立小额贷款公司的意义以及运作模式、产品设计和风险控制框架。

一、设立小额贷款公司的背景意义(一)小额贷款公司的定义小额信贷(microcredits)是国际上新兴的信贷概念。

有别于传统的贷款业务,小额信贷是以低端客户为服务对象,向其提供额度小到可以控制风险的无抵押信用贷款。

小额贷款是目前国内使用的概念,按照央行试点方案的定义,单笔贷款额在贷款机构注册资金5%以下的为小额贷款。

国内现行政策对小额贷款公司的定义是“由自然人、企业法人与其他社会组织投资设立,不吸收公众存款,经营小额贷款业务的有限责任公司或股份有限公司”(《关于小额贷款公司试点的指导意见》(银监发〔2022〕23号))。

(二)小额贷款公司的政策背景近年来,央行和银监会这两大金融监管机构分别发布了小额贷款公司管理的一些试行性质的规定,其中央行发布《关于村镇银行、贷款公司、农村资金互助社、小额贷款公司有关政策的通知》(银发〔2022〕137号),银监会先后发布了《关于调整放宽农村地区银行业金融机构准入政策更好支持社会主义新农村建设的若干意见》、《贷款公司管理暂行规定》(银监发〔2022〕6号)。

2022年,央行和银监会联合发布《关于小额贷款公司试点的指导意见》(银监发〔2022〕23号)。

在此类中央级别的规定之外,一些地方政府也相继发布了小额贷款公司试行规范,如重庆市人民政府发布《关于印发重庆市推进小额贷款公司试点指导意见的通知》(渝府发〔2022〕76号)。

这些中央和地方规定在小额贷款公司试运行方面做了大量尝试,为小额贷款公司业务的正规化、合法化作了铺垫。

银监会和人民银行在各自试点的基础上,逐步取得一些共识。

根据银监会、人行2022年发布的《关于小额贷款公司试点的指导意见》(银监发〔2022〕23号),小额贷款公司是由自然人、企业法人与其他社会组织投资设立,不吸收公众存款,经营小额贷款业务的有限责任公司或股份有限公司。

2010届毕业生毕业论文外文翻译姓名:院(系):专业班级:学号:指导老师:成绩:小额信贷是否帮助穷人?——孟加拉国旗舰计划所带来的新证据摘要:小额信贷运动使金融中介机构得到了创新,同样使贫困家庭减少了贷款的成本和风险。

孟加拉国乡村银行的小额信贷机制已经在全世界得到推广。

虽然小额贷款机制的目的是为客户带来社会和经济效益,但是通过其获得一定量的利益的尝试已经开始实施了。

本文借鉴一个新调查来研究小额信贷是是否真正的帮助穷人,该调查覆盖面近1800个家庭,其中部分家庭获得了孟加拉乡村银行的贷款,而另一部分则没有参与到小额贷款运动中。

有资格获得贷款的家庭,他们的消费水平低于平均消费水平,这种家庭中,绝大部分的孩子不可能上得起学,男子也往往会有更多的工作压力,而女子没有工作。

更明显的,相对于对照组,符合贷款资格的家庭在消费上的变化很小以及可以常年提供劳动力的特点。

最重要的潜在影响不是贫穷本身,而是因而最重要是减少相关的家庭漏洞。

似乎导致消费平滑主要原因是收入平滑,而不是借款和贷款。

评论家有大量的关于低收入国家的其他方案的研究经验。

虽然通常人们都是使用固定效力评估来控制与安置方案有关的不易观察的变量,但是使用固定效力评估会加剧偏见的影响,就如同本方案——在较大的社区里特定人群的方案。

关键词:小额信贷,项目评估,乡村银行,孟加拉1.介绍小额信贷在很多人的脑海里是用来减少贫困。

前提是操作简单。

小额信贷提供小额贷款,以促进小规模的创业活动,而不是向贫困家庭提供救济。

这种信贷除非放债人收取非常高的利率(往往收费高达每月10%),否则不会发生。

放债运作缺乏竞争,因为潜在的进入者很快发现,借款人通常不能提供任何形式的抵押品,这就使贷款存在高成本和该风险。

(拉希德和汤森,1993)。

然而,体制创新下的小额信贷运动似乎大大降低了风险和提供金融服务和为贫困家庭提供服务的费用。

创新包括借款合同、给予奖励、配出不良信用风险和连带借款人的活动,要求每周或每半周还款(Morduch,1997)。

2005年该运动已经在世界银行,联合国领导人,以及其他已加入的国际组织的推动下成为联系100万家庭的全球性的运动(小额信贷首脑会议,1997)。

该运动在美国还得到相当多的支持(包括钱第一夫人希拉里克林顿),现在该方案在美国有300个经营点(经济学家,1997)。

纽约时报(1997)还发表《庆祝这个“继续的反贫穷方案的革命”》文章呼吁支持。

但是,小额贷款到底给贫困家庭带来了怎样的巨大的影响?虽然小额贷款确实做到了减少贫困,但只有极少数研究使用相当大的样本和适当的治疗/控制框架来研究这个问题。

本研究调查了1800户家庭在1991—1992年间的孟加拉国格拉名银行的小额信贷项目,孟加拉国农村发展委员会(BRAC),和孟加拉国农村发展委员会(BRDB),本案例还包括了一组没有任何小额贷款项目服务地区的家庭。

这里考虑的这三个贷款方案在孟加拉国一共超过了400万贫困客户,它们的作用是非常广泛的。

格拉米银行的国际小额信贷旗舰运动,其模式已经被四大洲所复制,包括在美国的阿肯色州和内城芝加哥都取得明显成就。

从其带来的影响我们可以简单得出小额信贷所带来的成就。

例如,如果享受乡村银行服务的家庭按照从小额信贷项目贷款的总数来安排,则前四分之一的家庭享有人均消费相较于在底层四分之一的家庭要高出十五个百分点。

另外,62%的从乡村银行贷款的家庭的男孩可以上学,而34%的上学的男孩的家庭没有贷款。

而女孩的比例分别是55%对40%。

然而,这些简单的比较,大部分是由于选择偏差造成的。

一旦,对照组坐出了适当的比较,不管是受教育的男孩还是受教育的女孩,有权使用小额贷款项目的家庭并没有明显提高人均消费水平。

总之,人均消费水平低于对照组。

这一结论是惊人的,关于小额贷款的反对声音也频繁的在国际响起。

然而,有权获得项目资助确实使常年劳动力变得多元化。

相应的,该方法也降低常年各种各样的消费,所以,尽管该项目并没有提高平均消费水平,但他可以通过稳定收入的方法使这些家庭稳定消费水平。

至于在其弱点上的影响,结果突出了小额贷款的优势,这些优势很少被关于小额信贷的文献所关注(除皮特及科韩德科,1998b)。

该项目得到了一亿美金的援助,由此,我们也可以看到它的优势。

这一结果同样证明,评估者很容易误导项目的成就,而且,他们拥有许多相似评估经验,这些经验包括公众医疗及其他低收入国家的社会项目。

同这里一样,这些项目经常被限制在特殊的区域和特殊的目标人群,尤其是贫困家庭。

不同于那些富有国家,收入为基础意味着测试似乎从未进行过。

反而,例如,孟加拉国乡村小额贷款项目致力于“无地机能”,这条规定要求贷款的家庭必须有超过半英亩的可耕种土地。

如果这条合理要求被强制实施,并且是建立在家庭外因的特殊之上,这条项目规定将是合理统计的基础。

然后,我们就能从参与该项目的家庭组及未参与该项目的家庭组的比较中得到非常明朗的效果。

这一方法是回归间断设计的一个形式(坎贝尔,1969年),其见解提供了皮特和科韩德科工作(1998a和1998 b;在这里,他们用了相同的数据)的基础。

但是我们不能从这个例子里推出任何有效结论,这个数据说明人们经常违反规则。

例如,30%的乡村贷款人拥有远远多于半英亩的土地,他们拥有土地所有权的面的有14英亩之大。

那些记录在案有权借款的家庭或有权参与项目的家庭,其中一部分所拥有的土地大概是2英亩,相对的其他那部分要少一点。

下面的方法反而通过在乡村的比较,运用了测试组及对照组的数据。

乡村中没有参与项目的组中,其采样严格遵循半英亩规定。

然而,参与项目的村里,同组的不对称性在这里同样出现了问题。

采样战略在一开始就是一个解决办法。

采样是设计好的,这样,对照组才可以同测试组作比较。

强制要求测试组需要同对照组一样严格按照规定强制执行要求。

另外需要关注非随机安置方案的是,当考虑到地区固定影响水平或者他们的对等性时(例如皮特和科韩德科,1998a)。

当方案选择已经完成的好的地区的时候,出现向上偏差;当项目倾向于不发达地区时,则出现向下偏差。

然后,柜员频繁声明这并不是解决非随机安置方案的万灵药。

实际上,当项目安置被预测到针对目标人群没有观察到影响时,包括地区固定影响水平能使偏差增大。

这个数据暗示,这是经常出现的状况。

但是,带着减少变化和劳动力供应的期待,主要的定性结果对测试组及对照组的不易观察的乡村水平是健全的。

小额信贷在新兴优势突出的成果使得其很少考虑其脆弱性,这些好处应当判断有数百万美元支持这些方案。

研究结果还表明如何判别简单的误导性的指标,他们持有类似的在低收入国家其他社会项目评估如公共健康和低收入的经验教训。

由于,这些计划往往局限于特定地区和特定目标群体即典型的贫困家庭,所以,以收入为基础的测试方法几乎在较富裕的国家从来没有使用过。

Does Microfinance Really Help the Poor?New Evidence from Flagship Programs in BangladeshAbstractThe microfinance movement has built on innovations in financial intermediation that reduce the costs and risks of lending to poor households. Replications of the movement’s flagship, the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, have now spread around the world. While programs aim to bring social and economic benefits to clients, few attempts have been made to quantify benefits rigorously. This paper draws on a new cross-sectional survey of nearly 1800 households, some of which are served by the Grameen Bank and two similar programs, and some of which have no access to programs. Households that are eligible to borrow and have access to the programs do not have notably higher consumption levels than control households, and, for the most part, their children are no more likely to be in school. Men also tend to work harder, and women less. More favorably, relative to controls, households eligible for programs have substantially (and significantly) lower variation in consumption and labor supply across seasons. The most important potential impacts are thus associated with the reduction of vulnerability, not of poverty per se. The consumption-smoothing appears to be driven largely by income-smoothing, not by borrowing and lending. The evaluation holds lessons for studies of other programs in low-income countries. While it is common to use fixed effects estimators to control for unobservable variables correlated with the placement of programs, using fixed effects estimators can exacerbate biases when, as here, programs target their programs to specific populations within larger communities.Key words: microfinance, project evaluation, Grameen Bank, Bangladesh1. IntroductionMicrofinance has captured the imaginations of many people working to reduce poverty. The premise is simple. Rather than giving handouts to poor households, microfinance programs offer small loans to foster small-scale entrepreneurial activities. Such credit would otherwise not be available -- or would be only available at the very high interest rates charged by moneylenders (who often charge as much as 10% per month). Moneylenders operate with little competition since potential entrants quickly find that costs and risks are high -- and borrowers are usually unable to offer standard forms of collateral, if any at all (Rashid and Townsend, 1993).However, the emerging microfinance movement demonstrates institutional innovations that appear to greatly reduce the risk and cost of providing financial services to poor households. Innovations include contracts that give borrowers incentives to exclude bad credit risks and monitor other borr owers’ activities, schedules of loans that increase over time conditional on successful performance, and weekly or semi-weekly loan repayment requirements (Morduch, 1997). The movement is now global, and leaders at the World Bank, United Nations, and other international organizations have joined in pushing to reach 100 million households around the world by the year 2005 (Microfinance Summit, 1997). The movement has also generated considerable support in the U.S. (including the high-profile support of Hillary Rodham Clinton; Buntin, 1997), and small-scale programs now operate in 300 U.S. sites (Economist, 1997). The New York Times (1997) has celebrated this “much-needed revolution in anti-poverty programs” and called for enhanced support. But how great is the ultimate impact on poor households? While strong claims are made for the ability of microfinance to reduce poverty, only a handful of studies use sizeable samples and appropriate treatment/control frameworks to answer the question. The present study investigates a 1991-92 cross-sectional survey of nearly 1800 households in Bangladesh served by microfinance programs of the Grameen Bank, the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), and the Bangladesh Rural Development Board (BRDB). The sample also includes a control group of households in areas not served by any microfinance programs. The three lending programs considered here together serve over four million poor clients in Bangladesh, but their role is much broader. The Grameen Bank is the flagship of the international microfinance movement, and its model has now been replicated on four continents, including sites in the United States as varied as rural Arkansas and inner-city Chicago. Simple estimates of impacts show clear achievements. For example, if households served by the Grameen Bank are ordered by the amounts they have borrowed from the program, the top quarter enjoys 15% higher consumption per capita than households in the bottom quarter. In addition, 62% of the school-age sons of Grameen Bank borrowers are enrolled in school versus 34% of the sons of eligible households that do not borrow. For daughters, the Grameen advantage is 55% versus 40%.These simple comparisons appear to be driven entirely by selection biases, however. Once appropriate comparisons with control groups are made, access to the threemicrofinance programs does not yield meaningful increases in per capita consumption, the education of sons, nor the education of daughters. If anything, the levels are slightly lower than for control groups. The results are surprising and contradict frequent claims made about the programs in international discussions of microfinance.Access to the programs does, however, appear to aid the diversification of labor supply across seasons. In turn, access is associated with a reduction in the variability of consumption across seasons. Thus, while the programs may not increase consumption on average, they may offer households ways to smooth consumption through smoothing income. In pointing to impacts on vulnerability, the results highlight an advantage that is seldom considered in the emerging microfinance literature (an exception is Pitt and Khandker, 1998a). These benefits should be judged against the tens of millions of dollars that have supported the programs.The results also demonstrate how misleading simple performance indicators can be, and they hold lessons for evaluations of similar public health and other social programs in low-income countries.1 As here, such programs are often limited to particular regions and particular target groups, typically poor households. Unlike in wealthier countries, income-based means tests are almost never used. Instead, for example, the microfinance programs in rural Bangladesh focus on the “functionally landless” -- implemented as a rule barring lending to households owning over a half acre of cultivable land.The program rule can be the basis of a plausible econometric strategy if the eligibility requirement is strictly enforced and built around a feature that is exogenous to the household.Then, clean impacts can be gauged by comparing the status of households clustered just below the arbitrary dividing line to households clustered just above. This approach is a form of regression discontinuity design (Campbell, 1969), and the insights provide t he basis of Pitt and Khandker’s.1Simple evaluations are subject to multiple selection biases: self-selection into the programs by the most able, non-random program placement, and endogenous determination of the intensity of participation (e.g., the size of loans in microfinance). The typical problem stems from the near impossibility of finding good instrumental variables work (1998a and 1998b; they use the same data as used here).But the idea can not be implemented reliably in this sample. The data demonstrate frequent violations of the rules. For example, 30% of Grameen borrowers own more land than the half-acre cut-off, with landholdings as large as fourteen acres. Among households labeled in the survey as “eligible” to borrow and with access to programs, the fraction of borrowers is nearly twice as high for those holding over half an acre versus those below (63% versus 34% for the three programs combined; The first two rows of Table 1 give figures disaggregated by program). Counter to historical observations suggesting an absence of land markets in South Asia, there is also substantial evidence of land sales. The data show that nearly one eighth of borrowerspurchased substantial amounts of land in the six years prior to the survey.The approach below instead exploits the treatment/control aspect of the data through comparisons across villages. The groups in villages not served by programs were sampled with strict adherence to the half acre rule, however, and the asymmetry with groups in program villages creates problems here as well. A solution is to turn the sampling strategy on its head. While the sample was designed so that the control groups are comparable to the “treated” groups, the rule violations require that the treatment groups be redefined in order to bring them into conformity with the controls.An additional concern is given by non-random program placement. Upward biases arise when programs choose regions that are already doing well, and downward biases arise when programs favor disadvantaged areas. The typical response to the problem is to estimate impacts .。