Using continuations to implement thread management and communication in operating systems

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1.54 MB

- 文档页数:15

jetty的continuation的用法Jetty是一款用于构建高性能、可扩展的Java Web服务器和Web应用程序的开源框架。

Jetty中的continuation是一种用于支持异步处理的机制。

通过使用continuation,开发人员可以在请求处理过程中暂停请求,并在稍后的时间点继续处理。

本文将逐步介绍Jetty的continuation的用法,并探讨其在Web开发中的应用。

第一步:导入Jetty库和创建Servlet在使用Jetty的continuation之前,首先需要导入Jetty库到项目中。

可以在项目的构建工具(如Maven或Gradle)中添加Jetty的依赖项。

然后,我们需要创建一个Servlet类来处理请求和响应。

javaimport org.eclipse.jetty.server.Server;import org.eclipse.jetty.servlet.ServletContextHandler;import org.eclipse.jetty.servlet.ServletHolder;import javax.servlet.http.HttpServlet;import javax.servlet.http.HttpServletRequest;import javax.servlet.http.HttpServletResponse;public class MyServlet extends HttpServlet {Overrideprotected void doGet(HttpServletRequest request, HttpServletResponse response){处理GET请求的逻辑}Overrideprotected void doPost(HttpServletRequest request, HttpServletResponse response){处理POST请求的逻辑}public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception { Server server = new Server(8080);ServletContextHandler handler = new ServletContextHandler();handler.setContextPath("/");server.setHandler(handler);handler.addServlet(new ServletHolder(new MyServlet()), "/*");server.start();server.join();}}第二步:启用continuation在处理请求的Servlet方法中,可以通过调用`getContinuation()`方法来获得`Continuation`对象。

implementation的动词implementation一词常常出现在各种技术和商业相关的文献中,特别是在软件和系统的开发、升级和改进过程中经常使用。

它是实现的意思,即将计划中的一项策略、方针、流程、政策、程序、技术等落地,使之成为现实的过程。

1. 实现(Implement)implement是implementation的动词形式,它的基本含义是将计划、策略、方案等真正地付诸行动,使之成为现实。

实现可以是一个庞大的过程,它需要认真的计划、组织、协调、执行和监控,还需要充分的资源、技术和人力支持。

实现的成功与否往往取决于各种因素,如领导能力、沟通协调、技术可行性、预算和时间管理等。

2. 执行(Execute)execute也是implementation的一个同义词,它强调将计划和策略转化为具体的动作和任务,使之得以实现。

与实现不同的是,执行更加注重行动的速度和效率,以确保项目能够按时完工。

执行需要良好的组织能力、安排能力和沟通能力,同时也需要对人员和设备的规划和调配,以保证所有工作有序进行。

3. 部署(Deploy)deploy是指将某个系统或产品推向运行环境中,使其准备好接受用户的使用。

这个动作通常包括软件安装、硬件布置、网络配置、资源分配等。

部署是implementation过程中非常重要的一步,因为它的成功与否直接影响系统的可用性和用户满意度。

部署需要严谨的技术知识和安全意识,以确保系统正常运行且不会遭受黑客攻击等问题。

4. 推广(Promote)promote是指推动某个系统、服务或产品的普及和使用。

在implementation过程中,推广是非常关键的,因为只有得到用户的认可和支持,才能真正获取商业价值。

推广可以通过各种渠道进行,如广告宣传、营销推销、用户体验优化等。

推广需要有一个明确的目标和策略,并且需要有针对性地定位目标用户和市场。

5. 整合(Integrate)integrate是指将多个程序或系统进行无缝集成,使其能够协同工作。

jmeter constant throughput timer使用方法JMeter Constant Throughput Timer 使用方法在性能测试中,我们经常需要模拟不同负载条件下的系统行为。

为了控制负载的稳定性和一致性,JMeter 提供了 Constant Throughput Timer(恒定吞吐量定时器)。

Constant Throughput Timer 允许我们设置固定的请求吞吐量来模拟真实用户在特定时间段内的请求频率。

这对于测试系统在不同负载下的性能和稳定性非常有用。

使用 Constant Throughput Timer 需要以下步骤:1. 添加 Constant Throughput Timer 元件:在 JMeter Test Plan 的适当位置,右键点击选择 Add -> Timer -> Constant Throughput Timer。

2. 配置吞吐量参数:在 Constant Throughput Timer 的属性窗口中,可以设置以下参数:- Target Throughput(目标吞吐量):指定你想模拟的吞吐量(每秒请求数)。

例如,如果你想模拟每秒处理 100 个请求,可以将该值设置为 100。

- Calculate Throughput based on(以何种方式计算吞吐量):有两个选项可供选择,分别是此项的子选项。

- All active threads (所有活动线程):计算当前所有线程的吞吐量。

这是默认选项,适用于模拟所有线程以目标吞吐量发送请求。

- This thread only (仅当前线程):仅计算当前线程的吞吐量。

这对于仅测试单个线程的吞吐量很有用。

3. 应用和保存设置:完成配置后,点击 "Apply" 和 "OK" 以应用和保存Constant Throughput Timer 的设置。

Nominal Rigidities and the Dynamic Effects of a Shockto Monetary Policy∗Lawrence J.Christiano†Martin Eichenbaum‡Charles L.Evans§August27,2003AbstractWe present a model embodying moderate amounts of nominal rigidities that ac-counts for the observed inertia in inflation and persistence in output.The key featuresof our model are those that prevent a sharp rise in marginal costs after an expansion-ary shock to monetary policy.Of these features,the most important are staggeredwage contracts which have an average duration of three quarters,and variable capitalutilization.JEL:E3,E4,E5∗Thefirst two authors are grateful for thefinancial support of a National Science Foundation grant to the National Bureau of Economic Research.We would like to acknowledge helpful comments from Lars Hansen and Mark Watson.We particularly want to thank Levon Barseghyan for his superb research assistance,as well as his insightful comments on various drafts of the paper.This paper does not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve System.†Northwestern University,National Bureau of Economic Research,and Federal Reserve Banks of Chicago and Cleveland.‡Northwestern University,National Bureau of Economic Research,and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.§Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.1.IntroductionThis paper seeks to understand the observed inertial behavior of inflation and persistence in aggregate quantities.To this end,we formulate and estimate a dynamic,general equilibrium model that incorporates staggered wage and price contracts.We use our model to investigate what mix of frictions can account for the evidence of inertia and persistence.For this exercise to be well defined,we must characterize inertia and persistence precisely.We do so using estimates of the dynamic response of inflation and aggregate variables to a monetary policy shock.With this characterization,the question that we ask reduces to:‘Can models with moderate degrees of nominal rigidities generate inertial inflation and persistent output movements in response to a monetary policy shock?’1Our answer to this question is,‘yes’.The model that we construct has two key features.First,it embeds Calvo style nominal price and wage contracts.Second,the real side of the model incorporates four departures from the standard textbook one sector dynamic stochastic growth model.These depar-tures are motivated by recent research on the determinants of consumption,asset prices, investment and productivity.The specific departures that we include are habit formation in preferences for consumption,adjustment costs in investment and variable capital utilization. In addition,we assume thatfirms must borrow working capital tofinance their wage bill.Our keyfindings are as follows.First,the average duration of price and wage contracts in the estimated model is roughly2and3quarters,respectively.Despite the modest nature of these nominal rigidities,the model does a very good job of accounting quantitatively for the estimated response of the US economy to a policy shock.In addition to reproducing the dynamic response of inflation and output,the model also accounts for the delayed,hump-shaped response in consumption,investment,profits,productivity and the weak response of the real wage.2Second,the critical nominal friction in our model is wage contracts,not price contracts.A version of the model with only nominal wage rigidities does almost as well as the estimated model.In contrast,with only nominal price rigidities,the model performs very poorly.Consistent with existing results in the literature,this version of the model cannot generate persistent movements in output unless we assume price contracts of extremely long duration.The model with only nominal wage rigidities does not have this problem.Third,we document how inference about nominal rigidities varies across different spec-ifications of the real side of our model.3Estimated versions of the model that do not in-1This question that is the focus of a large and growing literature.See,for example,Chari,Kehoe and McGrattan(2000),Mankiw(2001),Rotemberg and Woodford(1999)and the references therein.2In related work,Sbordone(2000)argues that,taking as given aggregate real variables,a model with staggered wages and prices does well at accounting for the time series properties of wages and prices.See also Ambler,Guay and Phaneuf(1999)and Huang and Liu(2002)for interesting work on the role of wage contracts.3For early discussions about the impact of real frictions on the effects of nominal rigidities,see Blanchardcorporate our departures from the standard growth model imply implausibly long price and wage contracts.Fourth,wefind that if one only wants to generate inertia in inflation and persistence in output with moderate wage and price stickiness,then it is crucial to allow for variable capital utilization.To understand why this feature is so important,note that in our modelfirms set prices as a markup over marginal costs.The major components of marginal costs are wages and the rental rate of capital.By allowing the services of capital to increase after a positive monetary policy shock,variable capital utilization helps dampen the large rise in the rental rate of capital that would otherwise occur.This in turn dampens the rise in marginal costs and,hence,prices.The resulting inertia in inflation implies that the rise in nominal spending that occurs after a positive monetary policy shock produces a persistent rise in real output.Similar intuition explains why sticky wages play a critical role in allowing our model to explain inflation inertia and output persistence.It also explains why our assumption about working capital plays a useful role:other things equal,a decline in the interest rate lowers marginal cost.Fifth,although investment adjustment costs and habit formation do not play a central role with respect to inflation inertia and output persistence,they do play a critical role in accounting for the dynamics of other variables.Sixth,the major role played by the working capital channel is to reduce the model’s reliance on sticky prices.Specifically,if we estimate a version of the model that does not allow for this channel,the average duration of price contracts increases dramatically.Finally,wefind that our model embodies strong internal propagation mechanisms.The impact of a monetary policy shock on aggregate activity continues to grow and persist even beyond the time when the typical contract in place at the time of the shock is reoptimized.In addition,the effects persist well beyond the effects of the shock on the interest rate and the growth rate of money.We pursue a particular limited information econometric strategy to estimate and evaluate our model.To implement this strategy wefirst estimate the impulse response of eight key macroeconomic variables to a monetary policy shock using an identified vector autoregres-sion(V AR).We then choose six model parameters to minimize the difference between the estimated impulse response functions and the analogous objects in our model.4 The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.In section2we briefly describe our estimates of how the U.S.economy responds to a monetary policy shock.Section3 displays our economic model.In Section4we discuss our econometric methodology.Our empirical results are reported in Section5and analyzed in Section6.Concluding commentsand Fisher(1989),Ball and Romer(1990)and Romer(1996).For more recent quantitative discussions, see Chari,Kehoe and McGrattan(2000),Edge(2000),Fuhrer(2000),Kiley(1997),McCallum and Nelson (1998)and Sims(1998).4Christiano,Eichenbaum and Evans(1998),Edge(2000)and Rotemberg and Woodford(1997)have also applied this strategy in the context of monetary policy shocks.are contained in Section7.2.The Consequences of a Monetary Policy ShockThis section begins by describing how we estimate a monetary policy shock.We then re-port estimates of how major macroeconomic variables respond to a monetary policy shock. Finally,we report the fraction of the variance in these variables that is accounted for by monetary policy shocks.The starting point of our analysis is the following characterization of monetary policy:R t=f(Ωt)+εt.(2.1)Here,R t is the Federal Funds rate,f is a linear function,Ωt is an information set,andεt is the monetary policy shock.We assume that the Fed allows money growth to be whatever is necessary to guarantee that(2.1)holds.Our basic identifying assumption is thatεt is orthogonal to the elements inΩt.Below,we describe the variables inΩt and elaborate on the interpretation of this orthogonality assumption.We now discuss how we estimate the dynamic response of key macroecomomic variables to a monetary policy shock.Let Y t denote the vector of variables included in the analysis. We partition Y t as follows:Y t=[Y1t,R t,Y2t]0.The vector Y1t is composed of the variables whose time t elements are contained inΩt,and are assumed not to respond contemporaneously to a monetary policy shock.The vector Y2t consists of the time t values of all the other variables inΩt.The variables in Y1t are real GDP, real consumption,the GDP deflator,real investment,the real wage,and labor productivity. The variables in Y2t are real profits and the growth rate of M2.All these variables,except money growth,have been logged.We measure the interest rate,R t,using the Federal Funds rate.The data sources are in an appendix,available from the authors.With one exception(the growth rate of money)all the variables in Y t are include in levels.Altig,Christiano,Eichenbaum and Linde(2003)adopt an alternative specification of Y t,in which cointegrating relationships among the variables are imposed.For example,the growth rate of GDP and the log difference between labor productivity and the real wage are included.The key properties of the impulse responses to a monetary policy shock are insensitive to this alternative specification.The ordering of the variables in Y t embodies two key identifying assumptions.First,the variables in Y1t do not respond contemporaneously to a monetary policy shock.Second,the time t information set of the monetary authority consists of current and lagged values of the variables in Y1t and only past values of the variables in Y2t.Our decision to include all variables,except for the growth rate of M2and real profits in Y1t,reflects a long-standing view that macroeconomic variables do not respond instanta-neously to policy shocks(see Friedman(1968)).We refer the reader to Christiano,Eichen-baum and Evans(1999)for a discussion of sensitivity of inference to alternative assumptions about the variables included in Y1t.While our assumptions are certainly debatable,the anal-ysis is internally consistent in the sense that we make the same assumptions in our economic model.To maintain consistency with the model,we place profits and the growth rate of money in Y2t.The V AR contains4lags of each variable and the sample period is1965Q3-1995Q3.5 Ignoring the constant term,the V AR can be written as follows:Y t=A1Y t−1+...+A4Y t−4+Cηt,(2.2)where C is a9×9lower triangular matrix with diagonal terms equal to unity,andηt is a9−dimensional vector of zero-mean,serially uncorrelated shocks with diagonal variance-covariance matrix.Since there are six variables in Y1t,the monetary policy shock,εt,is the7th element ofηt.A positive shock toεt corresponds to a contractionary monetary policy shock. We estimate the parameters-A i,i=1,...,4,C,and the variances of the elements ofηt-using standard least squares ing these estimates,we compute the dynamic path of Y t following a one-standard-deviation shock inεt,setting initial conditions to zero.This path, which corresponds to the coefficients in the impulse response functions of interest,is invariant to the ordering of the variables within Y1t and within Y2t(see Christiano,Eichenbaum and Evans(1999).)The impulse response functions of all variables in Y t are displayed in Figure1.Lines marked‘+’correspond to the point estimates.The shaded areas indicate95%confidence intervals about the point estimates.6The solid lines pertain to the properties of our structural model,which will be discussed in section3.The results suggest that after an expansionary monetary policy shock there is a:•hump-shaped response of output,consumption and investment,with the peak effect occurring after about1.5years and returning to their pre-shock levels after about three years,•hump-shaped response in inflation,with a peak response after about2years,•fall in the interest rate for roughly one year,•rise in profits,real wages and labor productivity,and5This sample period is the same as in Christiano,Eichenbaum and Evans(1999).6We use the method described in Sims and Zha(1999).•an immediate rise in the growth rate of money.Interestingly,these results are consistent with the claims in Friedman(1968).For example, Friedman argued that an exogenous increase in the money supply leads to a drop in the interest rate that lasts one to two years,and a rise in output and employment that lasts from two tofive years.Finally,the robustness of the qualitative features of ourfindings to alternative identifying assumptions and sample sub-periods,as well as the use of monthly data,is discussed in Christiano,Eichenbaum and Evans(1999).Our strategy for estimating the parameters of our model focuses on only a component of thefluctuations in the data,namely the portion that is due to a monetary policy shock. It is natural to ask how large that component is,since ultimately we are interested in a model that can account for the variation in the data.With this question in mind,the following table reports variance decompositions.In particular,it displays the percent of the variance of the k−step forecast error in the elements of Y t due to monetary policy shocks, for k=4,8and20.Numbers in parentheses are the boundaries of the associated95% confidence interval.7Notice that policy shocks account for only a small fraction of inflation. At the same time,with the exception of real wages,monetary policy shocks account for a non-trivial fraction of the variation in the real variables.This last inference should be treated with caution.The confidence intervals about the point estimates are rather large. Also,while the impulse response functions are robust to the various perturbations discussed in Christiano,Eichenbaum and Evans(1999)and Altig,Christiano,Eichenbaum and Linde (2003),the variance decompositions can be sensitive.For example,the analogous point estimates reported in Altig,Christiano,Eichenbaum and Linde(2003)are substantially smaller than those reported in Table1.3.The Model EconomyIn this section we describe our model economy and display the problems solved byfirms and households.In addition,we describe the behavior offinancial intermediaries and the monetary andfiscal authorities.The only source of uncertainty in the model is a shock to monetary policy.7These confidence intervals are computed based on bootstrap simulations of the estimated VAR.In each artificial data set we computed the variance decompositions corresponding to the ones in Table1.The lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals correspond to the2.5and97.5percentiles of simulated variance decompositions.3.1.Final Good FirmsAt time t,afinal consumption good,Y t,is produced by a perfectly competitive,representative firm.Thefirm produces thefinal good by combining a continuum of intermediate goods, indexed by j∈[0,1],using the technologyY t=·Z10Y jt1f dj¸λf(3.1) where1≤λf<∞and Y jt denotes the time t input of intermediate good j.Thefirm takes its output price,P t,and its input prices,P jt,as given and beyond its control.Profit maximization implies the Euler equationµP t jt¶λfλf−1=Y jt t.(3.2)Integrating(3.2)and imposing(3.1),we obtain the following relationship between the price of thefinal good and the price of the intermediate good:P t=·Z10P11−λf jt dj¸(1−λf).(3.3) 3.2.Intermediate Good FirmsIntermediate good j∈(0,1)is produced by a monopolist who uses the following technology:Y jt=½kαjt L1−αjt−φif kαjt L1−αjt≥φ0otherwise(3.4) where0<α<1.Here,L jt and k jt denote time t labor and capital services used to produce the j th intermediate good.Also,φ>0denotes thefixed cost of production.We rule out entry and exit into the production of intermediate good j.Intermediatefirms rent capital and labor in perfectly competitive factor markets.Profits are distributed to households at the end of each time period.Let R k t and W t denote the nominal rental rate on capital services and the wage rate,respectively.Workers must be paid in advance of production.As a result,the j thfirm must borrow its wage bill,W t L jt, from thefinancial intermediary at the beginning of the period.Repayment occurs at the end of time period t at the gross interest rate,R t.Thefirm’s real marginal cost iss t=∂S t(Y)∂Y,where S t(Y)=mink,l©r k t k+w t R t l,Y given by(3.4)ª,where r k t=R k t/P t and w t=W t/P t.Given our functional forms,we haves t=µ1¶1−αµ1¶α¡r k t¢α(w t R t)1−α.(3.5)Apart fromfixed costs,thefirm’s time t profits are:·P jt P t−s t¸P t Y jt,where P jt isfirm j’s price.We assume thatfirms set prices according to a variant of the mechanism spelled out in Calvo(1983).This model has been widely used to characterize price-setting frictions.A useful feature of the model is that it can be solved without explicitly tracking the distribution of prices acrossfirms.In each period,afirm faces a constant probability,1−ξp,of being able to reoptimize its nominal price.The ability to reoptimize its price is independent across firms and time.If afirm can reoptimize its price,it does so before the realization of the time t growth rate of money.Firms that cannot reoptimize their price simply index to lagged inflation:P jt=πt−1P j,t−1.(3.6) Here,πt=P t/P t−1.We refer to this price-setting rule as lagged inflation indexation.Let˜P t denote the value of P jt set by afirm that can reoptimize at time t.Our notation does not allow˜P t to depend on j.We do this in anticipation of the well known result that, in models like ours,allfirms who can reoptimize their price at time t choose the same price (see Woodford,1996and Yun,1996).Thefirm chooses˜P t to maximize:∞X l=0¡βξp¢lυt+l h˜P t X tl−s t+l P t+l i Y j,t+l,(3.7)E t−1subject to(3.2),(3.5)and.(3.8)X tl=½πt×πt+1×···×πt+l−1for l≥11l=0In(3.7),υt is the marginal value of a dollar to the household,which is treated as exogenous by thefiter,we show that the value of a dollar,in utility terms,is constant across households.Also,E t−1denotes the expectations operator conditioned on lagged growth rates of money,µt−l,l≥1.This specification of the information set captures our assumption that thefirm chooses˜P t before the realization of the time t growth rate of money.To understand (3.7),note that˜P t influencesfirm j’s profits only as long as it cannot reoptimize its price.The probability that this happens for l periods is¡ξp¢l,in which case P j,t+l=˜P t X tl.The presence of¡ξp¢l in(3.7)has the effect of isolating future realizations of idiosyncratic uncertainty in which˜P t continues to affect thefirm’s profits.3.3.HouseholdsThere is a continuum of households,indexed by j∈(0,1).The j th household makes a sequence of decisions during each period.First,it makes its consumption decision,its capital accumulation decision,and it decides how many units of capital services to supply.Second, it purchases securities whose payoffs are contingent upon whether it can reoptimize its wage decision.Third,it sets its wage rate afterfinding out whether it can reoptimize or not. Fourth,it receives a lump-sum transfer from the monetary authority.Finally,it decides how much of itsfinancial assets to hold in the form of deposits with afinancial intermediary and how much to hold in the form of cash.Since the uncertainty faced by the household over whether it can reoptimize its wage is idiosyncratic in nature,households work different amounts and earn different wage rates.So, in principle,they are also heterogeneous with respect to consumption and asset holdings.A straightforward extension of arguments in Erceg,Henderson and Levin(2000)and Woodford (1996)establish that the existence of state contingent securities ensures that,in equilibrium, households are homogeneous with respect to consumption and asset holdings.Reflecting this result,our notation assumes that households are homogeneous with respect to consumption and asset holdings but heterogeneous with respect to the wage rate that they earn and hours worked.The preferences of the j th household are given by:∞X l=0βl−t[u(c t+l−bc t+l−1)−z(h j,t+l)+v(q t+l)].(3.9)E j t−1Here,E j t−1is the expectation operator,conditional on aggregate and household j idiosyn-cratic information up to,and including,time t−1;c t denotes time t consumption;h jt denotes time t hours worked;q t≡Q t/P t denotes real cash balances;Q t denotes nominal cash balances.When b>0,(3.9)allows for habit formation in consumption preferences.The household’s asset evolution equation is given by:M t+1=R t[M t−Q t+(µt−1)M a t]+A j,t+Q t+W j,t h j,t(3.10)+R k t u t¯k t+D t−P t¡i t+c t+a(u t)¯k t¢.Here,M t is the household’s beginning of period t stock of money and W j,t h j,t is time t labor income.In addition,¯k t,D t and A j,t denote,respectively,the physical stock of capital,firm profits and the net cash inflow from participating in state-contingent securities at time t. The variableµt represents the gross growth rate of the economy-wide per capita stock of money,M a t.The quantity(µt−1)M a t is a lump-sum payment made to households by the monetary authority.The quantity M t−P t q t+(µt−1)M a t,is deposited by the household with afinancial intermediary where it earns the gross nominal rate of interest,R t.The remaining terms in(3.10),aside from P t c t,pertain to the stock of installed capital, which we assume is owned by the household.The household’s stock of physical capital,¯k t, evolves according to:¯k=(1−δ)¯k t+F(i t,i t−1).(3.11)t+1Here,δdenotes the physical rate of depreciation and i t denotes time t purchases of invest-ment goods.The function,F,summarizes the technology that transforms current and past investment into installed capital for use in the following period.We discuss the properties of F below.Capital services,k t,are related to the physical stock of capital byk t=u t¯k t.Here,u t denotes the utilization rate of capital,which we assume is set by the household.8 In(3.10),R k t u t¯k t represents the household’s earnings from supplying capital services.The increasing,convex function a(u t)¯k t denotes the cost,in units of consumption goods,of setting the utilization rate to u t.3.4.The W age DecisionAs in Erceg,Henderson and Levin(2000),we assume that the household is a monopoly sup-plier of a differentiated labor service,h jt.It sells this service to a representative,competitive firm that transforms it into an aggregate labor input,L t,using the following technology:L t=·Z10h1λjt dj¸λw.The demand curve for h jt is given by:h jt=µW t jt¶λwλw−1L t,1≤λw<∞.(3.12) Here,W t is the aggregate wage rate,i.e.,the price of L t.It is straightforward to show that W t is related to W jt via the relationship:W t=·Z10(W jt)11−λw dj¸1−λw.(3.13) The household takes L t and W t as given.8Our assumption that households make the capital accumulation and utilization decisions is a matter of convenience.At the cost of a more complicated notation,we could work with an alternative decentralization scheme in whichfirms make these decisions.Households set their wage rate according to a variant of the mechanism used to model price setting byfirms.In each period,a household faces a constant probability,1−ξw, of being able to reoptimize its nominal wage.The ability to reoptimize is independent across households and time.If a household cannot reoptimize its wage at time t,it sets W jt according to:W j,t=πt−1W j,t−1.(3.14) 3.5.Monetary and Fiscal PolicyWe assume that monetary policy is given by:µt=µ+θ0εt+θ1εt−1+θ2εt−2+...(3.15)Here,µdenotes the mean growth rate of money andθj is the response of E tµt+j to a time t monetary policy shock.We assume that the government has access to lump sum taxes and pursues a Ricardianfiscal policy.Under this type of policy,the details of tax policy have no impact on inflation and other aggregate economic variables.As a result,we need not specify the details offiscal policy.93.6.Loan Market Clearing,Final Goods Clearing and EquilibriumFinancial intermediaries receive M t−Q t from households and a transfer,(µt−1)M t from the monetary authority.Our notation here reflects the equilibrium condition,M a t=M t. Financial intermediaries lend all of their money to intermediate goodfirms,which use the funds to pay for L t.Loan market clearing requiresW t L t=µt M t−Q t.(3.16) The aggregate resource constraint isc t+i t+a(u t)≤Y t.We adopt a standard sequence-of-markets equilibrium concept.In the appendix we discuss our computational strategy for approximating that equilibrium.This strategy involves taking a linear approximation about the non-stochastic steady state of the economy and using the solution method discussed in Christiano(2003).For details,see the previous version of this paper,Christiano,Eichenbaum and Evans(2001).In principle,the non-negativity constraint on intermediate good output in(3.4)is a problem for this approximation.It turns out that the constraint is not binding for the experiments that we consider and so we ignore it.Finally, it is worth noting that since profits are stochastic,the fact that they are zero,on average, 9See Sims(1994)or Woodford(1994)for a further discussion.implies that they are often negative.As a consequence,our assumption thatfirms cannot exit is binding.Allowing forfirm entry and exit dynamics would considerably complicate our analysis.3.7.Functional Form AssumptionsWe assume that the functions characterizing utility are given by:u(·)=log(·)z(·)=ψ0(·)2.(3.17)v(·)=ψq(·)1−σqqIn addition,investment adjustment costs are given by:F(i t,i t−1)=(1−Sµi t i t−1¶)i t.(3.18) We restrict the function S to satisfy the following properties:S(1)=S0(1)=0,andκ≡S00(1)>0.It is easy to verify that the steady state of the model does not depend on the adjustment cost parameter,κ.Of course,the dynamics of the model are influenced byκ. Given our solution procedure,no other features of the S function need to be specified for our analysis.We impose two restrictions on the capital utilization function,a(u t).First,we require that u t=1in steady state.Second,we assume a(1)=0.Under our assumptions,the steady state of the model is independent ofσa=a00(1)/a0(1).The dynamics do depend onσa.Given our solution procedure,we do not need to specify any other features of the function a. 4.Econometric MethodologyIn this section we discuss our methodology for estimating and evaluating our model.We partition the model parameters into three groups.Thefirst group is composed ofβ,φ,α,δ,ψ0,ψq,λw andµ.We setβ=1.03−0.25,which implies a steady state annualized real interest rate of3percent.We setα=0.36,which corresponds to a steady state share of capital income equal to roughly36percent.We setδ=0.025,which implies an annual rate of depreciation on capital equal to10percent.This value ofδis roughly equal to the estimate reported in Christiano and Eichenbaum(1992).The parameter,φ,is set to guarantee that profits are zero in steady state.This value is consistent with Basu and Fernald(1994),Hall (1988),and Rotemberg and Woodford(1995),who argue that economic profits are close to zero on average.Although there are well known problems with the measurement of profits, we think that zero profits is a reasonable benchmark.。

implementation在计算机程序中的意思在计算机程序中,implementation(实现)是一个重要的概念。

它指的是将软件系统的设计转化为可执行的代码的过程,也即将程序设计的想法转化为计算机能够理解和运行的指令集合。

在本文中,我们将探讨implementation在计算机程序中的意义以及其在软件开发过程中的重要性。

一、实现的概念及作用实现是指将软件系统的设计转化为计算机程序的过程。

在软件开发中,实现是软件生命周期的重要环节之一。

它是软件开发过程中的一个具体步骤,通过该步骤可以将软件设计的抽象思想转化为可以被计算机执行的实体。

实现的主要作用是实际完成软件系统的设计,并将其转化为计算机可以执行的代码。

通过实现,程序员可以将软件需求和设计的想法付诸实践,使其成为具体可行的计算机程序。

实现的过程中,程序员需要根据设计文档和需求说明书,编写相应的代码,并进行测试和调试,确保程序的正确性和性能。

二、实现的步骤在实现一个计算机程序时,一般会按照以下步骤进行:1. 编写代码:根据软件设计的要求和需求进行代码编写。

在编写代码时,程序员需要使用合适的编程语言,并按照设计的要求实现相应的功能模块。

2. 调试与测试:在编写代码后,程序员需要对代码进行调试和测试。

通过测试,可以发现潜在的错误和不足之处,并修改或完善代码。

3. 代码优化:在确保程序的功能正确性后,程序员还可以对代码进行优化。

优化的目标是提高程序的性能和效率,减少内存占用和运行时间。

4. 文档编写:实现完成后,程序员需要编写相应的文档,包括程序的使用手册、编程说明等。

这些文档有助于其他程序员了解和使用该程序。

5. 部署与发布:最后,实现完成的程序可以进行部署和发布。

部署是指将程序安装到计算机系统中,使用户可以使用;发布是指将程序提供给用户下载或使用。

三、实现的重要性实现是软件开发过程中至关重要的一环。

以下是实现的几个重要方面:1. 将设计转化为现实:实现将软件设计的抽象思想变为计算机可以执行的代码,使设计变得具体可行。

keras中implementation的作用

在Keras中,`implementation`参数是在定义某些层的时候使用的。

它是一个可选的参数,表示层的实现方式,允许用户选择在CPU或GPU 上实现。

在某些情况下,特定的层实现可能更适合在GPU上执行,这会提高训练速度。

例如,在LSTM层中,有两种实现方式:基于CPU的实现和基于GPU的实现。

在使用CPU时,LSTM层的计算是通过CPU来实现的;而在使用GPU时,LSTM层的计算可以通过GPU来并行化加速。

因此,通过设定`implementation`参数,可以根据硬件配置来选择合适的实现方式,从而提高训练速度。

`implementation`参数的取值可以是以下三个字符串中的一个:

- `0`:基于CPU的实现;

- `1`:基于GPU的实现;

- `2`:根据输入数据的大小自动选择实现方式。

关闭流的优化写法如何优化关闭流的写法。

在程序开发中,流是一种常见的数据传输方式。

无论是读取输入还是写入输出,我们经常需要使用流来操作文件、网络连接或其他数据源。

在使用流之后,我们通常需要关闭它们,以确保资源的释放和程序的健壮性。

虽然关闭流看起来像是一个简单的操作,但实际上有许多细节和技巧可以用来优化这个过程。

在本文中,我将一步一步地解释如何优化关闭流的写法。

第一步:正确的使用try-with-resourcesJava 7 引入了一个重要的特性,叫做try-with-resources。

通过使用这个特性,我们可以更简洁地管理资源。

当我们使用try-with-resources语句时,我们只需要在括号内声明和初始化流对象,然后在执行完try块之后,这些流就会自动关闭。

这种方式不仅简化了代码,还确保了资源的正确关闭。

以下是一个使用try-with-resources关闭流的示例代码:try (InputStream inputStream = new FileInputStream("file.txt");OutputStream outputStream = newFileOutputStream("output.txt")) {使用流进行读写操作} catch (IOException e) {处理异常}在这个例子中,我们通过使用try-with-resources来关闭输入流和输出流。

在try块中,我们可以进行读取和写入操作,而不需要显式地关闭流。

一旦try块结束,这些流将被自动关闭。

第二步:正确处理异常当我们操作流时,可能会发生各种异常情况。

在关闭流之前,我们需要确保捕获并正确处理这些异常。

否则,在异常发生时,流可能无法正确地关闭,导致资源泄漏和程序崩溃。

在前面的示例代码中,我使用了一个catch块来捕获IOException异常。

在实际编码中,我们可能需要根据具体的需求来处理不同的异常情况。

Winsorising 是一种数据处理方法,用于处理极端值或异常值。

它的主要目的是减少数据中的极端值对统计分析的影响。

具体来说,Winsorising 方法会将数据中的最小值和最大值替换为指定的界限值,而不是直接删除或忽略这些极端值。

这个界限值通常是数据中的最小值和最大值的某个百分比,例如 1% 或 5%。

通过 Winsorising,可以减少极端值对数据平均值、中位数等统计指标的影响,使这些指标更能反映数据的一般趋势和分布情况。

Winsorising 方法通常在数据预处理阶段使用,特别是在进行统计分析之前,以减少异常值对结果的影响。

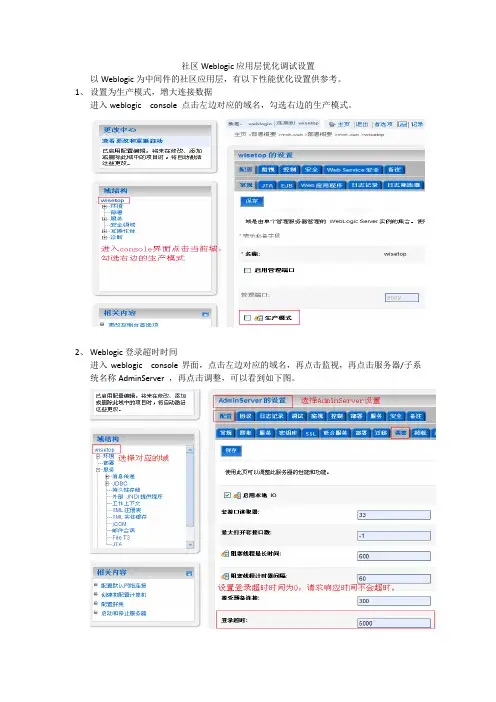

社区Weblogic应用层优化调试设置

以Weblogic为中间件的社区应用层,有以下性能优化设置供参考。

1、设置为生产模式,增大连接数据

进入weblogic console 点击左边对应的域名,勾选右边的生产模式。

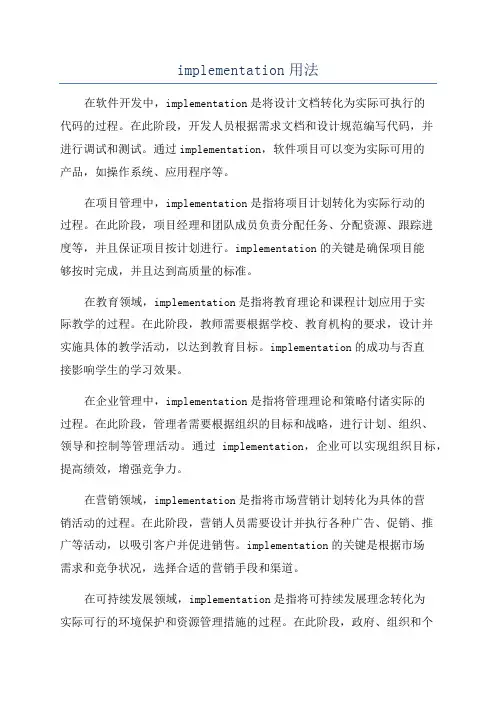

2、Weblogic登录超时时间

进入weblogic console界面,点击左边对应的域名,再点击监视,再点击服务器/子系统名称AdminServer ,再点击调整,可以看到如下图。

3、设置weblogic 占用的内存值

进入weblogic安装域名目录所在的bin文件夹,修改setDomainEnv.sh 文件根据物理机的实际情况设置内存值

4、设置应用服务数据库连接数据

打开应用程序xp-app 的jdbc数据连接文件

根据oracle实际连接数修改jdbc连接数

Oracle连接数据查看show parameter processes;

5、不限制事务数量

修改服务的事务处理数量限制,修改xp-app应用服务的jta.properties

超出默认的50会报错误

Caused by: ng.IllegalStateException: Max number of active transactions reached:50

6、优化程序代码

在weblogic安装域目录下的log日志可以看到严重超时方法。

implementation用法在软件开发中,implementation是将设计文档转化为实际可执行的代码的过程。

在此阶段,开发人员根据需求文档和设计规范编写代码,并进行调试和测试。

通过implementation,软件项目可以变为实际可用的产品,如操作系统、应用程序等。

在项目管理中,implementation是指将项目计划转化为实际行动的过程。

在此阶段,项目经理和团队成员负责分配任务、分配资源、跟踪进度等,并且保证项目按计划进行。

implementation的关键是确保项目能够按时完成,并且达到高质量的标准。

在教育领域,implementation是指将教育理论和课程计划应用于实际教学的过程。

在此阶段,教师需要根据学校、教育机构的要求,设计并实施具体的教学活动,以达到教育目标。

implementation的成功与否直接影响学生的学习效果。

在企业管理中,implementation是指将管理理论和策略付诸实际的过程。

在此阶段,管理者需要根据组织的目标和战略,进行计划、组织、领导和控制等管理活动。

通过implementation,企业可以实现组织目标,提高绩效,增强竞争力。

在营销领域,implementation是指将市场营销计划转化为具体的营销活动的过程。

在此阶段,营销人员需要设计并执行各种广告、促销、推广等活动,以吸引客户并促进销售。

implementation的关键是根据市场需求和竞争状况,选择合适的营销手段和渠道。

在可持续发展领域,implementation是指将可持续发展理念转化为实际可行的环境保护和资源管理措施的过程。

在此阶段,政府、组织和个人需要制定并实施各种政策、计划和行动,以减少对环境的影响,保护自然资源。

implementation的成功与否直接影响到环境的可持续发展。

综上所述,implementation在不同领域中都有着重要的作用。

它是将理论和计划转化为实际行动的桥梁,对于实现目标和取得成功至关重要。

线程池饱和策略拒绝策略

线程池饱和策略是指当线程池中的线程都在忙碌时,如何处理新的任务。

拒绝策略是指在任务被拒绝之前,如何处理任务。

常用的线程池饱和策略有四种:

1. CallerRunsPolicy:在任务被拒绝后,主线程会执行该任务。

这种策略可以避免任务丢失,但会导致主线程变慢。

2. AbortPolicy:在任务被拒绝后,会抛出一个RejectedExecutionException异常。

这种策略可以避免主线程变慢,但会丢失任务。

3. DiscardPolicy:在任务被拒绝后,会直接丢弃任务,不会抛出异常。

这种策略可以避免抛出异常,但会丢失任务。

4. DiscardOldestPolicy:在任务被拒绝后,会丢弃最早加入任务队列的任务,然后重新尝试执行任务。

这种策略可以避免丢失任务,但会丢失最早加入队列的任务。

在实际开发中,选择合适的饱和策略非常重要,需要根据具体情况进行选择。

如果任务不能丢失,可以选择CallerRunsPolicy策略;如果不能影响主线程,可以选择AbortPolicy策略;如果不能抛出异常,可以选择DiscardPolicy策略;如果可以丢失最早加入队列的任务,可以选择DiscardOldestPolicy策略。

- 1 -。

istio熔断配置参数

在Istio中,熔断是一种用于保护应用程序免受服务间故障的机制。

您可以通过配置以下参数来进行Istio的熔断配置:

1.maxConnections(最大连接数):定义允许的最大并发连接数。

超过此数量的连接将被拒绝。

2.httpConsecutiveErrors(连续错误阈值):定义在触发熔断之前连续出现的HTTP 错误次数。

达到此阈值后,将触发熔断。

3.httpDetectionInterval(HTTP 探测间隔):定义用于检测失败请求的时间间隔。

在此间隔内,如果出现连续错误次数超过阈值的情况,则会触发熔断。

4.sleepWindow(休眠窗口):定义触发熔断后的休眠时间,即熔断器打开后暂停对服务的请求的时间段。

5.requestV olumeThreshold(请求数量阈值):定义在进行熔断判断之前,必须满足的最小请求数量。

6.errorRatioThreshold(错误比例阈值):定义触发熔断的错误比例阈值。

当请求错误率超过此阈值时,将触发熔断。

这些参数可以在Istio 的DestinationRule 资源中进行配置,以指定适当的熔断策略。

请注意,这些参数可能会根据Istio 版本和配置方式有所不同,建议查阅Istio 官方文档以获取最新的详细信息。

1。

java调用存储过程后处理数据的方法

在Java中调用存储过程后,我们需要对返回的数据进行处理。

以下是一些处理数据的方法:

1. 使用ResultSet对象来获取存储过程返回的结果集。

可以使用ResultSet的getXXX()方法来获取不同类型的数据。

2. 使用CallableStatement对象来调用存储过程,并使用其方法registerOutParameter()来注册输出参数的类型。

然后可以使用getXXX()方法来获取输出参数的值。

3. 使用ORM框架,如Hibernate或MyBatis,可以将存储过程映射为一个Java方法,并使用返回值或输出参数来获取数据。

4. 使用JdbcTemplate(Spring框架中的一个类),可以方便地调用存储过程并获取结果集或输出参数的值。

5. 使用Java8中的Streams API,可以对ResultSet对象进行流式处理,例如使用stream()方法将ResultSet转换为流,然后使用map()、filter()、reduce()等方法来处理数据。

总之,在Java中调用存储过程后,我们有多种处理数据的方式。

我们可以根据具体情况选择最合适的方法。

- 1 -。

节流(Throttling)和去抖(Debouncing)详解这篇⽂章的作者是 ,伦敦的⼀名前端开发⼯程师。

之前我们有⼀篇关于”节流”和”去抖”的⽂章:(译⽂:),但是David的这篇⽂章通过⼀些可交互的Demo来给我们做了⼀个更详细的解释。

“节流”和”去抖”都是⽤来限制⼀些需要⼀直执⾏的函数的技术,它们虽然很相似,但它们是不⼀样的。

当我们需要做⼀些DOM事件绑定时,”节流”和”去抖”是⾮常有⽤的。

因为这样的话,我们在事件和事件函数之间⼜多了⼀层控制。

所以,我们控制的不是事件的触发(事件触发的时机和频率),⽽是事件触发后去限制事件函数的执⾏。

例如我们⾮常常⽤的滚动事件:当我们在电脑上进⾏滚动(⽤触控板、⿏标滚轮、拉动滚动条)的话,事件的触发可能会⽐较好控制⼀些,⽐如我想让它每秒触发30次,那么我滚动的慢⼀点,是可以达到的。

但是,如果我在移动设备上(⽐如智能⼿机,iPad等设备)上进⾏滑动的话,每秒钟会触发100次左右。

这很显然不是我们想要的结果,因为事件函数执⾏了太多次了。

在2011年,Twitter的⽹站出现过⼀个问题:当你滚动Twitter⽹站到底部进⾏加载数据时,页⾯将会变的⾮常卡,有时甚⾄未响应。

写了⼀篇来说明了这个问题。

John当年(2011年)给出的解决⽅案是在滚动事件的外⾯以250毫秒为单位进⾏循环执⾏函数,这样函数和事件之间就实现了松耦合。

⽤了这个⽅法,⾄少就不会影响到正常的⽤户体验了。

⽽现在,我们有⼀些更好更精细的⽅法来处理这个问题。

下⾯,就让我们来介绍⼀下”去抖”、”节流”和”requestAnimationFrame()“⽅法。

我们将通过对应的案例来进⾏详细的说明。

去抖“去抖”可以让我们把⼀个连续的的函数调⽤”打包”成⼀个。

举个例⼦,假如你正在坐电梯,电梯门即将关上,这时突然有⼀个⼈想上电梯,于是电梯的门⼜开了。

随后⼜来了⼀个⼈,同样的事⼜发⽣了⼀遍。

电梯的根本功能是将你带到其它的楼层,⽽现在它由于很多⼈按电梯,所以到其它楼层这件事⼉就被延误了,但是这样设计的原因是为了最终能节省资源。

一、名词解释(5*3分=15分)(斜体表明仅供参考) 计量经济学:以经济理论和经济数据的事实为依据,运用数学和统计学的方法,通过建立数学模型来研究经济数量关系和规律的一门经济学科。

最小二乘法:指在满足古典假设的条件下,用使估计的剩余平方和最小的原则确定样本回归函数的方法,简称OLS 随机扰动项:总体回归函数中,各个Y值与条件期望的Y值的偏差,又称随机误差项。

是代表那些对Y有影响但又未纳入模型的诸多因素的影响。

总体回归函数:在给定解释变量X i条件下,总体被解释变量Y i的期望轨迹,函数式表示为E(Y i∣X i)=f(Xi)= β0+β1X i 样本回归函数:在总体中抽取若干个样本构成新的总体,然后在新的总体下,给定解释变量X i,被解释变量Y i的期望轨迹,函数式表示为E(Y i∣X i)=Y i^= β0^+β1^X i系数显着性检验:(t检验)对回归系数对应的解释变量是否对被解释变量有显着影响的统计学检验方法方程显着性检验:(F检验)对模型的被解释变量与所有解释变量之间的线性关系在整体上是否显着的统计学检验方法高斯-。

拟合优度多重共线性异方差(εi)=σi2σi2,根据最小自相关≠j)判断题(1234567891011 ( 乂 )12、变量不存在两两高度相关表示不存在高度多重共线性。

( 乂 )13、当异方差出现时,最小二乘估计是有偏的和不具有最小方差特性。

(乂)14、当异方差出现时,常用的t检验和F检验失效。

(√)15、在异方差情况下,通常OLS估计一定高估了估计量的标准差。

(乂)16、如果OLS回归的残差表现出系统性,则说明数据中有异方差性。

(√)17、如果回归模型遗漏一个重要的变量,则OLS残差必定表现出明显的趋势。

(√)18、在异方差情况下,通常预测失效。

(√)19、当模型存在高阶自相关时,可用D-W法进行自相关检验。

(乂)20、当模型的解释变量包括内生变量的滞后变量时,D-W检验就不适用了。

电力建设施工质量验收规程第2部分:锅炉机组前言本规程是根据《国家能源局关于下达2014年第二批能源领域行业标准制(修)订计划的通知》(国能科技〔2015〕12号)的要求,在原《电力建设施工质量验收及评价规程第2部分锅炉机组》DL/T5210.2-2009和《电力建设施工质量验收及评价规程第8部分加工配制》DL/T5210.8-2009基础上修订的。

《电力建设施工质量验收规程》DL/T5210共6个部分:——DL/T 5210.1 第1部分土建工程——DL/T 5210.2 第2部分锅炉机组——DL/T 5210.3 第3部分汽轮发电机组——DL/T 5210.4 第4部分热工仪表及控制装置——DL/T 5210.5 第5部分焊接——DL/T 5210.6 第6部分火电机组调整试验本部分是DL/T 5210的第2部分。

本规程共14章和4个附录,主要内容包括:总则、术语、基本规定、施工质量验收范围划分表、施工质量验收通用表格及记录签证清单、锅炉本体安装、锅炉除尘装置安装、锅炉燃油系统设备及管道安装、锅炉辅助机械安装、输煤设备安装、烟气脱硫设备安装、烟气脱硝装置安装、锅炉炉墙砌筑、加工配制等。

附录A、附录B、附录C、附录D为规范性附录。

本规程由中国电力企业联合会提出。

由电力行业火电建设标准化技术委员会归口。

本规程主要起草单位:中国电建集团核电工程公司、中国能源建设集团天津电力建设有限公司、中国能源建设集团安徽电力建设第一工程有限公司。

本规程参加起草单位:中国电建集团河南工程公司、中国能源建设集团湖南火电建设有限公司、四川电力建设三公司、中国能源建设集团浙江火电建设有限公司、上海电力建设有限责任公司、山东诚信工程建设监理有限公司、中国电力建设工程咨询有限公司。

本规程主要起草人:李鹏庆、张耸、张所庆、贾广明、谢鸿钢、马骁、李俊、曾易成、朱春宝、刘保忠、姚建民、黄庆国、由庆山、徐耀兵、李长翔、付连兵、龙晓周本规程主要审查委员:王立、孙家华、曹生堂、张朝霞、段建林、黄龙平、吴利中、沈建、李双国、罗彬红、张忠华、李强、周明钢、吕永文、郑蓓、魏洪瑞、王宝华、赵子成、李青山庞力平、党小建、辛忠富、李立平本规程自发布实施之日起,原国家能源局颁发的2009年发布的《电力建设施工质量验收及评价规程第2部分:锅炉机组》及《电力建设施工质量验收及评价规程第8部分:加工配制》废止。