区域经济一体化导论

- 格式:pptx

- 大小:12.57 MB

- 文档页数:7

《世界经济概论》教学大纲及教案全套第一章:世界经济导论1.1 课程介绍1.2 世界经济的基本概念1.3 世界经济的发展历程1.4 世界经济学的学科体系第二章:国际分工与贸易2.1 国际分工的含义与分类2.2 国际贸易的理论基础2.3 国际贸易政策与措施2.4 世界贸易组织与国际贸易规则第三章:国际金融市场3.1 国际金融市场的概念与功能3.2 国际金融市场的体系与机构3.3 国际金融市场的基本业务3.4 国际金融市场的风险与管理第四章:国际资本流动4.1 国际资本流动的含义与类型4.2 国际资本流动的原因与影响4.3 国际资本流动的管理与调控4.4 国际资本流动与我国经济发展第五章:国际经济合作5.1 国际经济合作的概念与类型5.2 国际经济合作的主要领域5.3 国际经济合作的机制与组织5.4 国际经济合作的前景与挑战第六章:全球宏观经济政策协调6.1 全球经济政策协调的必要性6.2 主要国家的宏观经济政策6.3 国际经济政策协调机制6.4 中国在全球经济政策协调中的角色第七章:区域经济一体化7.1 区域经济一体化的概念与类型7.2 区域经济一体化的理论基础7.3 主要区域经济一体化组织及其特点7.4 中国与区域经济一体化的关系第八章:国际经济关系中的政治因素8.1 国际政治与经济关系的互动8.2 霸权主义与强权政治在经济领域的体现8.3 发展中国家在国际经济关系中的地位与作用8.4 国际经济争端的解决机制第九章:世界经济趋势与挑战9.1 全球化的影响与挑战9.2 新一轮全球产业转移的趋势与影响9.3 可持续发展与绿色经济9.4 新冠疫情对世界经济的影响与展望第十章:中国的世界经济地位与战略10.1 中国世界经济地位的变化与影响10.2 中国参与国际经济合作的战略选择10.3 “一带一路”倡议与国际经济合作10.4 中国在全球经济治理中的角色与责任重点和难点解析重点一:世界经济的基本概念与学科体系难点解析:理解世界经济作为一个独立学科的形成背景、研究方法和学科体系。

《世界经济概论》教学大纲及教案全套第一章:世界经济导论1.1 世界经济的基本概念1.2 世界经济的发展历程1.3 世界经济的组成部分1.4 世界经济的研究方法第二章:国际分工与贸易2.1 国际分工的定义与形式2.2 国际贸易的理论与实证2.3 贸易政策与国际贸易2.4 贸易自由化与保护主义第三章:国际金融市场3.1 国际金融市场的概述3.2 国际货币体系3.3 外汇市场与汇率决定3.4 国际资本流动与金融监管第四章:国际经济组织4.1 国际经济组织的概述4.2 世界贸易组织(WTO)4.3 国际货币基金组织(IMF)4.4 世界银行集团(WBG)第五章:区域经济一体化5.1 区域经济一体化的概念与类型5.2 欧洲联盟(EU)5.3 北美自由贸易区(NAFTA)5.4 亚洲太平洋经济合作组织(APEC)第六章:全球产业分布与跨国公司6.1 全球产业分布的特点与趋势6.2 跨国公司的角色与影响6.3 跨国公司的组织结构与经营策略6.4 跨国公司与全球经济一体化第七章:国际转移定价与税收7.1 转移定价的概念与方法7.2 跨国公司转移定价的策略7.3 国际税收体系与税收协定7.4 转移定价对国家税收的影响及应对措施第八章:国际政治经济关系8.1 国际政治经济关系的基本理论8.2 国家利益与国际合作8.3 国际冲突与经济制裁8.4 发展中国家在国际政治经济中的地位与作用第九章:全球环境问题与可持续发展9.1 全球环境问题的现状与挑战9.2 可持续发展理论及其内涵9.3 国际环境治理与合作9.4 绿色经济和低碳发展第十章:世界经济前景与挑战10.1 世界经济发展趋势分析10.2 全球经济面临的挑战与风险10.3 全球化进程中的政策选择10.4 我国应对全球经济挑战的策略与展望第十一章:国际金融市场与衍生品11.1 国际金融市场的基本构成11.2 金融衍生品市场概述11.3 利率、汇率和股票市场的衍生品11.4 金融衍生品的风险与管理第十二章:国际能源市场12.1 世界能源资源分布与消费12.2 国际能源市场的基本机制12.3 能源价格的决定因素12.4 能源政策与国际合作第十三章:国际劳动力流动13.1 国际劳动力流动的类型与原因13.2 劳动力流动对迁入国和迁出国的影响13.3 国际移民政策与管理13.4 全球化背景下的国际劳动力市场第十四章:国际旅游产业14.1 国际旅游产业的基本特征14.2 旅游需求、供给与国际旅游市场14.3 旅游业的可持续发展14.4 旅游政策与国际合作第十五章:世界经济与中国15.1 中国经济在世界经济中的地位15.2 中国参与国际经济合作与竞争15.3 中国对外经济政策与发展战略15.4 中国与世界经济未来的展望重点和难点解析第一章:世界经济导论重点:理解世界经济的基本概念、发展历程和组成部分。

目 录第1章 导 论第2章 国际贸易的作用第3章 国际分工第4章 世界市场第5章 世界市场价格第6章 国际贸易政策第7章 国际贸易促进、救济与管制第8章 区域经济一体化第9章 世界贸易组织第10章 关 税第11章 非关税壁垒第12章 国际服务贸易第13章 与贸易有关的知识产权保护第14章 国际投资与国际贸易第15章 世界贸易中的中国第1章 导 论1什么是国际贸易?答:国际贸易(International Trade)是指世界各国各地区之间货物、服务和生产要素变换的活动。

国际贸易是各国各地区之间分工的表现形式,反映了世界各国、各地区在经济上的相互依存。

从国家角度可称为对外贸易,从国际角度可称为国际贸易。

2对外贸易的产生需要什么条件?答:对外贸易的产生必须具备以下两个条件:(1)有可供交换的剩余产品。

(2)出现了政治实体。

对外贸易属于历史范畴,是人类社会发展到一定历史阶段的产物,是社会生产发展的必然结果。

3国际贸易如何分类?答:按照不同的分类标准,可对国际贸易进行不同的分类。

(1)按交易内容划分,对外贸易可分为货物贸易、服务贸易和国际技术贸易。

(2)按商品的移动方向划分,对外贸易可分为出口贸易、进口贸易、过境贸易、复出口与复进口、净出口与净进口。

(3)按交易对象划分,对外贸易可分为直接贸易、间接贸易和转口贸易。

(4)按运输方式划分,对外货物贸易可分为海运贸易、陆运贸易、空运贸易、多式联运贸易和邮购贸易等。

其中,海运贸易是国际贸易最主要的运输方式。

4如何区分狭义与广义的对外贸易结构?答:(1)狭义的对外贸易结构狭义的对外贸易结构是指货物贸易或服务贸易本身的结构比较,可分为对外货物贸易结构与对外服务贸易结构。

其中,对外货物贸易结构是指一定时期内一国或世界进出口货物贸易中以百分比表示的各类货物的构成;对外服务贸易结构是指一定时期内一国或世界进出口服务贸易中以百分比表示的各类项目的构成。

(2)广义的对外贸易结构广义的对外贸易结构是指货物、服务在一国总进出口贸易或国际贸易中所占的比重。

第1章导论1、“区域”一般指根据一定目的和原则划分的地球表面上一定的空间范围。

2、“经济区域”概念的基本内涵:(1)经济区域是在一个主权国家范围内基于分析、研究、规划、管理需要而划分的经济空间。

(2)经济区域是由在经济上具有同质性、内聚性的地域单元所构成的经济空间。

(3)经济区域是由在经济上具有共同利益、在地缘上彼此邻接的地域单元所构成的经济空间。

(4)经济区域是一个在全国专业化分工中分担一定职能、经济结构较为完整的社会经济综合体。

3、“经济区域”概念的基本内涵:是指一国范围内在经济上具有同质性或内聚性,具有一定的共同利益,经济结构较为完整且在全国专业化分工中承担一定职能的地域空间。

4.经济区域的划分标准:(1)差异性标准或同质性标准。

(2)内聚性标准或集聚性标准。

(3)毗邻性标准。

(4)兼顾行政区划标准。

5、经济区域的构成要素:经济中心、经济腹地、经济网络。

魏后凯等(2006)五要素说:区域的内聚力、结构、功能、规模和边界。

相比而言,三要素说具有较强的理论解释力。

1.经济中心是区域经济活动中心点,即城市。

区域经济空间聚集指向于城市,是由城市具有聚集经济效益的缘故。

2.经济腹地是经济中心的辐射范围,也是经济区域的空间范围。

3. 经济网络是经济联系的实体渠道或载体。

6、区域的经济中心具有四大特征:(1)等级结构的多层次性。

(2)城市选择性。

(3)经济中心性。

(4)功能和职能的综合性。

物质构成内容为交通运输网络、邮电通信网络。

经济中心和腹地的沟通主要依托于交通网络和通信网络,缺乏它经济区域就不能形成。

经济区域的扩大和经济强度的增加都取决于交通通信网络的形成与发展。

7、区域经济的内涵和特征(1)区域经济:是指“一定地域空间内各种经济活动所组合成的有机体”。

(2)区域经济五大鲜明特征:中观性、区域性、差异性、开放性、独立性。

(3)区域经济存在的客观基础:1.人类经济活动的空间依赖性是区域经济存在的一般前提。

区域经济学重点笔记第⼀章导论1 区分经济区域和区域经济。

区域经济学初步形成的标志:1956年胡弗《区域经济学导论》(1)区域经济学所研究的空间:经济区域。

(强调空间)①客观存在的经济区域,多为具有相对完善的点、线、⾯结构的功能区。

如:地域⽣产综合体、⾏政—经济区、核⼼—边缘区,通常为异质区。

②⼈们出于研究的⽬的划分的经济区域,通常属于同质区。

(2)区域经济学研究的内容:区域经济。

(强调经济活动)①区域经济指的是特定的经济区域及其相互之间经济活动。

②区域经济是国民经济或国际经济的组成部分。

¥③在通常情况下,区域经济并不具有宏观经济的基本属性。

④国家尺度以下的地⽅经济,以及城市经济都可以被看作是区域经济。

⑤在中国,区域经济往往还特指⾏政区经济。

2 经济区域的特点。

(1)、有限的空间。

(2)、往往包括在⼀个国家的疆域内。

(3)、经济上完整。

(4)、在经济系统中具备专业化分⼯的职能。

3 古典区位论的缺陷。

(1)假设前提是完全竞争(2)部门最优与整体最优往往不⼀致¥(3)⾃由竞争下的⾃由放任往往导致区际间不平衡(4)研究⽅法局部均衡,静态(5)单纯考虑纯粹的经济因素,忽略了创新环境、制度变迁、不确定的政治因素、社会⽂化背景等对经济活动的影响。

区域早期区位论:重商主义贸易观古典贸易与分⼯理论:绝对优势理论(斯密) ⽐较优势理论(李嘉图)古典的区域经济学时期——古典的区位论:农业区位论⼯业区位论市场区位论中⼼地理论第⼆次世界⼤战后区位论的发展:1)从单个⼚商的区位决策发展到地区总体经济结构及其模型的研究…2)从抽象的纯理论模型的推导,变为⼒求作出接近区域实际的、可具有应⽤型的区域模型第⼆章区域经济学的基本概念1 区位与区位决策的含义。

(1)区位:指可以供(经济)活动选择的位置或者是(经济)活动位置的确定过程。

区位通常指经济活动出现的最有利的有限空间范围。

(特定空间,寻找最优空间过程)(2)区位决策:⼈类在⾃⼰的社会⽣活中,不得不为⾃⾝或所代表的机构(企业、社团、政府等)做出各种各样的选择。

区域经济学第一章导论区域经济学江苏师范大学国土资源研究所渠立权课程介绍:本课程是土地管理专业的重要专业课程,主要包括如下内容:区域经济要素、区域经济增长与发展、区域经济结构、区域经济关系、区域经济制度等。

除此之外,本教材还介绍了区域经济可持续发展、区域经济发展战略、区域经济与城市化道路等内容。

区域经济学是地理学尤其是经济地理学与经济学、规划学等学科的交叉学科,学好区域经济学除了要求同学们具有这些学科的知识外,还要有一定的数学基础和综合分析问题的能力。

第一章导论要点:界定基本概念介绍区域经济学研究对象、主要内容区域经济学的发展历史、发展过程区域经济研究方法和任务一、区域经济学基本概念1、区域区域:区域经济学的研究对象指拥有多种类型的资源、可以进行多种生产性和非生产性社会经济活动的一片相对较大的空间范围(即经济区域,有别于自然区域)。

区域经济学研究的区域主要包括三大类:全国国土,一国范围内特定的区域,以及跨国界的特定区域。

经济区域有以下八个特点区域具有经济含义(社会经济活动在空间上的实现)。

它内部的资源、经济背景、产业特点、经济政策、与其他区域的关系等等是区域经济学研究的主要问题。

区域内部的同质性(相似性)。

区域间的异质性(差异性)。

边界的模糊性和范围的可变性。

统一性(是自然背景条件、物质内容及其结构等要素有机结合而成的地域单元)。

经济区域的系统性(内部各组成部分组成系统的有机整体,外部开放性)。

周期性(具有萌芽、形成、成长、衰退的发展过程)层次性根据区域的特点,一般而言,以行政边界作为区域边界的做法只能带来区域管理上的方便,对区域经济政策上的制定、资源优化配置、促进区域经济发展是不利的。

经济区域的类型根据形态特征,经济区域有均质区域和极化区域。

根据物质内容的差异,经济区域可分为工业经济区、农业经济区、流域经济区等等。

2、区域经济学区域经济学是研究区域经济发展和区际关系的科学。

它要回答一个区域是如何实现经济增长和经济发展的,各个地区以及主要城市在全国劳动地域分工中具有什么样的优势,应该处于什么样的地位,承担什么样的功能;应该与其他地区建立怎样的技术经济联系,如何建立这种联系。

胡佛《区域经济学导论》英文版(doc 328)部门: xxx时间: xxx整理范文,仅供参考,可下载自行编辑An Introduction toRegional EconomicsEdgar M. Hoover and Frank Giarratani1 Introduction1.1 WHAT IS REGIONAL ECONOMICS?Economic systems are dynamic entities, and the nature and consequences of changes that take place in these systems are of considerable importance. Such change affects the well-being of individuals and ultimately the social and political fabric of community and nation. As social beings, we cannot help but react to the changes we observe. For some people that reaction is quite passive; the economy changes, and they find that their immediate environment is somehow different, forcing adjustment to the new reality. For others, changes in the economic system represent a challenge; they seek to understand the nature of factors that have led to change and may, in light of that knowledge, adjust their own patterns of behavior or attempt to bring about change in the economic, political, and social systems in which they live and work.In this context, regional economics represents a framework within which the spatial character of economic systems may be understood. We seek to identify the factors governing the distribution of economic activity over space and to recognize that as this distribution changes, there will be important consequences for individuals and for communities.Thus, regional or "spatial" economics might be summed up in the question "What is where, and why—and so what?" The first what refers to every type of economic activity: not only production establishments in the narrow sense of factories, farms, and mines, but also other kinds of businesses, households, and private and public institutions. Where refers to location in relation to other economic activity; it involves questions of proximity, concentration, dispersion, and similarity or disparity of spatial patterns, and it can be discussed either in broad terms, such as among regions, or microgeographically, in terms of zones, neighborhoods, and sites. The why and the so what refer to interpretations within the somewhat elastic limits of the economist's competence and daring.Regional economics is a relatively young branch of economics. Its late start exemplifies the regrettable tendency of formal professional disciplines to lose contact with one another and to neglect some important problem areas that require a mixture of approaches. Until fairly recently, traditional economists ignored the where question altogether, finding plenty of problems to occupy them without giving any spatial dimension to their analysis. Traditional geographers, though directly concerned with what is where, lacked any real technique of explanation in terms of human behavior and institutions to supply the why, and resorted to mere description and mapping. Traditional city planners, similarly limited, remained preoccupied with the physical and aesthetic aspects of idealized urban layouts.This unfortunate situation has been corrected to a remarkable extent within the last few decades. Individuals who call themselves by various professional labels—economists, geographers, ecologists, city and regional planners, regional scientists, and urbanists—have joinedto develop analytical tools and skills, and to apply them to some of the most pressing problems of the time.The unflagging pioneer work and the intellectual and organizational leadership of Walter Isard since the 1940s played a key role in enlisting support from various disciplines to create this new focus. His domain of "regional science" is extremely broad. This book will follow a less comprehensive approach, using the special interests and capabilities of the economist as a point of departure.1.2 THREE FOUNDATION STONESIt will be helpful to realize at the outset that three fundamental considerations underlie the complex patterns of location of economic activity and most of the major problems of regional economics.The first of these "foundation stones" appears in the simplistic explanations of the location of industries and cities that can still be found in old-style geography books. Wine and movies are made in California because there is plenty of sunshine there; New York and New Orleans are great port cities because each has a natural water-level route to the interior of the country; easily developable waterpower sites located the early mill towns of New England; and so on. In other words, the unequal distribution of climate, minerals, soil, topography, and most other natural features helps to explain the location of many kinds of economic activity. A bit more generally and in the more precise terminology of economic theory, we can identify the complete or partial immobility of land and other productive factors as one essential part of any explanation of what is where. Such immobility lies at the heart of the comparative advantage that various regions enjoy for specialization in production and trade.This is, however, by no means an adequate explanation. One of the pioneers of regional economics, August Lösch, set himself the question of what kind of location patterns might logically be expected to appear in an imaginary world in which all natural resource differentials were assumed away, that is, in a uniformly endowed flat plain.1In such a situation, one might conceivably expect (1) concentration of all activities at one spot, (2) uniform dispersion of all activities over the entire area (that is, perfect homogeneity), or (3) no systematic pattern at all, but a random scatter of activities. What does actually appear as the logical outcome is none of these, but an elaborate and interesting regular pattern somewhat akin to various crystal structures and showing some recognizable similarity to real-world patterns of distribution of cities and towns. We shall have a look at this pattern in Chapter 8. What the Christaller-Lösch theoretical exercises demonstrated was that factors other than natural-resource location play an important part in explaining the spatial pattern of activities.In developing his abstract model, Lösch assumed just two economic constraints determining location: (1) economies of spatial concentration and (2) transport costs. These are the second and third essential foundation stones.Economists have long been aware of the importance of economies of scale, particularly since the days of Adam Smith, and have analyzed them largely in terms of imperfect divisibility of production factors and other goods and services. The economies of spatial concentration in their turn can, as we shall see in Chapter 5 and elsewhere, be traced mainly to economies of scale in specific industries.Finally, goods and services are not freely or instantaneously mobile: Transport and communication cost something in effort and time. These costs limit the extent to which advantagesof natural endowment or economies of spatial concentration can be realized.To sum up, an understanding of spatial and regional economic problems can be built on three facts of life: (1) natural-resource advantages, (2) economies of concentration, and (3) costs of transport and communication. In more technical language, these foundation stones can be identified as (1) imperfect factor mobility, (2) imperfect divisibility, and (3) imperfect mobility of goods and services.1.3 REGIONAL ECONOMIC PROBLEMS AND THE PLAN OF THIS BOOKWhat, then, are the actual problems in which an understanding of spatial economics can be helpful? They arise, as we shall see, on several different levels. Some are primarily microeconomic, involving the spatial preferences, decisions, and experiences of such units as households or business firms. Others involve the behavior of large groups of people, whole industries, or such areas as cities or regions. To give some idea of the range of questions involved and also the approach that this book takes in developing a conceptual framework to handle them, we shall follow here a sequence corresponding to the successive later chapters.The business firm is, of course, most directly interested in what regional economics may have to say about choosing a profitable location in relation to given markets, sources of materials, labor, services, and other relevant location factors. A nonbusiness unit such as a household, institution, or public facility faces an analogous problem of location choice, though the specific location factors to be considered may be rather different and less subject to evaluation in terms of price and profit. Our survey of regional economics begins in Chapter 2 by taking a microeconomic viewpoint. That is, all locations, conditions, and activities other than the individual unit in question will be taken as given: The individual unit's problem is to decide what location it prefers.The importance of transport and communication services in determining locations (one of the three foundation stones) will become evident in Chapter 2. The relation of distance to the cost of the spatial movement of goods and services, however, is not simple. It depends on such factors as route layouts, scale economies in terminal and carriage operations, the length of the journey, the characteristics of the goods and services transferred, and the technical capabilities of the available transport and communication media. Chapter 3identifies and explains such relations and will explore their effects on the advantages of different locations.In Chapter 4, an analysis of pricing decisions and demand in a spatial context is developed. This analysis extends some principles of economics concerning the theory of pricing and output decisions to the spatial dimension. As a result, we shall be able to appreciate more fully the relationship between pricing policies and the market area of a seller. We shall find also that space provides yet another dimension for competition among sellers. Further, this analysis will serve as a basis for understanding the location patterns of whole industries. If an individual firm or other unit has any but the most myopic outlook, it will want to know something about shifts in such patterns. For example, a firm producing oil-drilling or refinery equipment should be interested in the locational shifts in the oil industry and a business firm enjoying favorable access to a market should want to know whether it is likely that more competition will be coming its way.While some of the issues developed in Chapter 4 concern factors that contribute to the dispersion of sellers within an industry, Chapter 5 recognizes the powerful forces that may draw sellers together in space. From an analysis of various types of economies of spatial concentration and a description of empirical evidence bearing on their significance, we shall find that the nature of this foundation stone of location decisions can have important consequences for local areas orregions.Chapter 6 introduces explicit recognition of the fact that activities require space. Space (or distance, which is simply space in one dimension) plays an interestingly dual role in the location of activities. On the one hand, distance represents cost and inconvenience when there is a need for access (for instance, in commuting to work or delivering a product to the market), and transport and communication represent more or less costly ways of surmounting the handicaps to human interaction imposed by distance. But at the same time, every human activity requires space for itself. In intensively developed areas, sheer elbowroom as well as the amenities of privacy are scarce and valuable. In this context, space and distance appear as assets rather than as liabilities.Chapter 6 treats competition for space as a factor helping to determine location patterns and individual choices. The focus here is still more "macro" than the discussion of location patterns developed in preceding chapters, in that it is concerned with the spatial ordering of different types of land use around some special point—for example, zones of different kinds of agriculture around a market center. In Chapter 6, the location patterns of many industries or other activities are considered as constituents of the land-use pattern of an area, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Many of the real problems with which regional economies deal are in fact posed in terms of land use (How is this site or area best used?) rather than in terms of location per se (Where is this firm, household, or industry best situated?). The insights developed in this chapter are relevant, then, not only for the individual locators but also for those owning land, operating transit or other utility services, or otherwise having a stake in what happens to a given piece of territory.The land-use analysis of Chapter 6 serves also as a basis for understanding the spatial organization of economic activity within urban areas. For this reason, Chapter 7employs the principles of resource allocation that govern land use and exposes the fundamental spatial structure of urban areas. Consideration is given also to the reasons for and implications of changes in urban spatial structure. This analysis provides a framework for understanding a diverse array of problems faced by city planners and community developers and redevelopers.In Chapter 8, the focus is broadened once more in order to understand patterns of urbanization within a region: the spacing, sizes, and functions of cities, and particularly the relationship between size and function. Real-world questions involving this so-called central-place analysis include, for example, trends in city-size distributions. Is the crossroads hamlet or the small town losing its functions and becoming obsolete, or is its place in the spatial order becoming more important? What size city or town is the best location for some specific kind of business or public facility? What services and facilities are available only in middle-sized and larger cities, or only in the largest metropolitan centers? In the planned developed or underdeveloped region, what size distribution and location pattern of cities would be most appropriate? Any principles or insights that can help answer such questions or expose the nature of their complexity are obviously useful to a wide range of individuals.Chapter 9deals with regions of various types in terms of their structure and functions. In particular, it concerns the internal economic ties or "linkages" among activities and interests that give a region organic entity and make it a useful unit for description, analysis, administration, planning, and policy.After an understanding of the nature of regions is developed in Chapter 9, our attention turns to growth and change and to the usefulness and desirability of locational changes, as distinct from rationalizations of observed behavior or patterns. Chapter 10 deals specifically with people andtheir personal locational preferences; it is a necessary prelude to the consideration of regional and urban development and policy that follows. Migration is the central topic, since people most clearly express their locational likes and dislikes by moving. Some insight into the factors that determine who moves where, and when, is needed by anyone trying to foresee population changes (such as regional and community planners and developers, utility companies, and the like). This insight is even more important in connection with framing public policies aimed at relieving regional or local poverty and unemployment.Chapters 11and 12, dealing with regional development and related policy issues, are concerned wit the region as a whole plus a still higher level of concern; namely, the national interest in the welfare and growth of the nation's constituent regions. Chapter 11, building on the concepts of regional structure developed in Chapter 9, concentrates on the process and causes of regional growth and change. Viewing the region as a live organism, we develop a basic understanding of its anatomy and physiology. Chapter 12 proposes appropriate objectives for regional development (involving, that is, the definition of regional economic "health"). It analyzes the economic ills to which regions are heir (pathology) and ventures to assess the merits of various kinds of policy to help distressed regions (therapeutics).Throughout this text, evidence of the special significance of the "urban" region will be found. Discussions of economies associated with the spatial concentration of activity, land use, and regional development and policy have important urban dimensions. It is fitting, the, that the last chapter of the text, Chapter 13, focuses on some major present-day urban problems and possible curative or palliative measures. Attention is given to four areas of concern (downtown blight, poverty, urban transport, and urban fiscal distress) in which spatial economic relationships are particularly important and the relevance of our specialized approach is therefore strong.It is hoped that this discussion has served to create an awareness of some basic factors governing the spatial distribution of economic activity and their importance in a larger setting. The course of study on which we are about to embark will introduce a framework for understanding the mechanisms by which these factors have effect. It holds out the prospect of developing perspective on associated problems and a basis for the analysis of those problems and their consequences.SELECTED READINGSMartin Beckmann, Location Theory (New York: Random House, 1968).Edgar M. Hoover, "Spatial Economics: Partial Equilibrium Approach," in Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (New York: Macmillan, 1968).Walter Isard, Location and Space-Economy (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1956).August Lösch, Die räumliche Ordnung der Wirtschaft (Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1940; 2nd ed., 1944); W. H. Woglom (tr.), The Economics of Location (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1954).Leon Moses, "Spatial Economics: General Equilibrium Approach," in Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (New York: Macmillan, 1968).Hugh O. Nourse, Regional Economics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968).Harry W. Richardson, "The State of Regional Economics," International Regional Science Review, 3, 1 (Fall 1978), 1-48.Harry W. Richardson, Regional Economics (Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1979).ENDNOTES1. A point of departure for Lösch's work was that of a predecessor, the geographer Walter Christaller, whose studies were more empirically oriented.An Introduction to Regional EconomicsEdgar M. Hoover and Frank Giarratani2 Individual Location Decisions2.1 LEVELS OF ANAL YSIS AND LOCATION UNITSLater in this book we shall come to grips with some major questions of locational and regional macroeconomics; our concern will be with such large and complex entities as neighborhoods, occupational labor groups, cities, industries, and regions. We begin here, however, on a microeconomic level by examining the behavior of the individual components that make up those larger groups. These individual units will be referred to as location units.Just how microscopic a view one takes is a matter of choice. Within the economic system there are major producing sectors, such as manufacturing; within the manufacturing sector are various industries. An industry includes many firms; a firm may operate many different plants, warehouses, and other establishments. Within a manufacturing establishment there may be several buildings located in some more or less rational relation to one another. Various departments may occupy locations within one building; within one department there is a location pattern of individual operations and pieces of equipment, such as punch presses, desks, or wastebaskets.At each of the levels indicated, the spatial disposition of the units in question must be considered: industries, plants, buildings, departments, wastebaskets, or whatever. Although determinations of actual or desirable locations at different levels share some elements,1 there are substantial differences in the principles involved and the methods used. Thus, it is necessary to specify the level to which one is referring.We shall start with a microscopic but not ultramicroscopic view, ignoring for the most part (despite their enticements in the way of immediacy, practicality, and amenability to some highly sophisticated lines of spatial analysis) such issues as the disposition of departments or equipment within a business establishment or ski lifts on a mountainside or electric outlets in a house. Our smallest location units will be defined at the level of the individual dwelling unit, the farm, the factory, the store, or other business establishment, and so on. These units are of three broad types: residential, business, and public. Some location units can make independent choices and are their own "decision units"; others (such as branch offices or chain store outlets) are located by external decision.Many individual persons represent separate residential units by virtue of their status as self-supporting unmarried adults; but a considerably larger number do not. In the United States in 1980, only about one person in twelve lived alone. About 44 percent of the population were living in couples (mostly married); nearly 30 percent were dependent children under eighteen; and a substantial fraction of the remainder were aged, invalid, or otherwise dependent members of family households, or were locationally constrained as members of the armed forces, inmates of institutions, members of monastic orders, and so on. For these types of people, the residential location unit is a group of persons.In the business world, the firm is the unit that makes locational decisions (the location decision unit), but the "establishment" (plant, store, bank branch, motel, theater, warehouse, and。

学 号: 经济全球化与区域经济一体化研究内蒙古科技大学《世界经济全球化与区域经济一体化》结课论文完成日期:2012-6-28题 目: ***学生姓名: **********国际经济与贸易专 业: 09级4班 班 级:吕跃聪授课教师:目录一、导论 (1)二、经济全球化 (1)2.1经济全球化的产生 (1)2.1.1经济全球化的定义 (1)2.1.2经济全球化形成的必然性 (1)2.2经济全球化的发展 (2)2.3经济全球化的影响 (2)2.3.1积极影响 (2)2.3.1消极影响 (2)三、区域经济一体化 (3)3.1区域经济一体化的产生 (3)3.1.1概念与内涵 (3)3.1.2区域经济一体化的产生原因 (3)3.2区域经济一体化的形式 (3)3.3区域经济一体化的影响 (4)3.3.1积极影响 (4)3.3.2消极影响 (4)3.4区域经济一体化的性质 (4)四、经济全球化与区域经济一体化的关系 (5)五、中国的应对策略 (6)5.1经济全球化下的中国 (6)5.2区域经济一体化下的中国 (6)六、参考文献 (7)一、导论经济全球化与区域经济一体化是世界经济发展的两种趋势。

然而在20世纪90年代中期以来,在经济全球化屡屡受阻的同时,区域经济一体化却在迅猛推进。

面对当前区域经济一体化的大潮,世界各国,包括发展中国家,都在几集寻求区域合作。

20世纪80年代冷战结束以来,经济全球化再次成为支配世界发展的新趋势。

无可否认,经济全球化加速了商品和要素全球范围的流动,推动了技术的进步,深化了劳动的分工,提高了生产效率,,使许多国家,包括发展中国家从中受益。

各国再也不能独立于世界经济体系之外而封闭发展。

然而随着经济全球化的不断推进,我们在承认经济全球化积极作用的同时,不容忽视它所带来的诸多不利的消极影响和严重后果。

20世纪90年代中期以来,在经济全球化屡屡受阻的同时,区域经济一体化却在迅猛推进。

面对当前区域经济一体化的大潮,世界各国,包括发展中国家,都在几集寻求区域合作。

区域经济一体化的理论基础区域经济一体化的萌芽可追溯到19世纪中叶。

1843年,北德、中德和南德三个关税同盟联合起来建立的德意志关税同盟,可看作是世界上最早开始的区域经济一体化的雏形(池元吉,2003)。

美国学者D. A. 斯奈德在《国际经济学导论》(第四版)中指出,德意志关税同盟的建立可称为区域经济一体化的“历史原型”,“二战”后才发展出比它结合程度低或高的其他类型。

区域经济一体化的真正形成和发展是在第二次世界大战以后。

1976年,经济学家弗瑞茨·迈克卢普(Fritz Machlup,1976)在对经济文献进行广泛研究与评论时了解到:在1947年以前,经济学家几乎没有写过涉及经济一体化的著作,尽管当时存在着经济一体化现象。

[1]随着“二战”后初期欧洲一体化运动的发展,经济学界开始较为关注经济一体化现象,可是理论研究的成果仍然稀稀拉拉,没有使人们对经济一体化的实际进程或后果的理解向前迈进一步。

事实上,当时经济一体化问题的研究基本上仍停留在实证上,而没有上升到理论层面(Bhagwati and Panagariya,2003)。

本书的写作有两条线索,一是建立在制度协调基础之上的区域一体化的组成部分——贸易一体化,二是专业化分工。

因此,本章将分别对传统区域经济一体化的理论基础及分工的理论渊源进行简单回顾,以此作为贸易一体化的理论背景。

[2]此外,由于贸易一体化体现为一个从市场驱动的区域化到制度协调的区域主义的演进过程,因此本章第三部分将对区域化和区域主义的相关理论进行梳理。

第一节传统区域经济一体化的理论框架传统区域经济一体化的理论框架是指以欧洲的区域一体化为背景建立的一体化组织模式。

这种组织模式为研究人员更为简洁地描述区域一体化的进程提供了一条清晰的思路,同时在解释欧洲一体化的进程方面具有一定的说服力。

但同时也应注意到,现实世界中各个经济体之间的“区域”合作动机和目的是比较复杂的,有些合作甚至超出了“区域”的范畴。

区域经济学的书

推荐以下几本关于区域经济学的书籍(按推荐程度排序):

1. 《区域经济学》(第4版)- 胡林、刘明生、吕一沙

该书对区域经济学的基本理论、分析方法和政策实践进行了详细介绍,阐述了城市化、城市体系和产业集聚等重要问题,是一本系统而

全面的教材。

2. 《地理经济学》- 郑裕彤

该书主要探讨了地理与经济之间的关系,涵盖了城市发展、区域发展、经济增长等方面的内容,重点分析了地理条件在区域经济中的影

响作用。

3. 《区域经济学导论》- 陈宗兴

该书系统地介绍了区域经济学的基本理论、分析框架和方法,包括

地理因素、空间结构和区域发展动力等方面的内容,适合初学者入门。

4. 《区域经济学原理》- 荀子杰、李晴

该书对区域经济学的基本概念、基础理论和政策分析进行了讲解,

包括区域发展理论、区域经济政策设计和区域经济研究方法等内容。

5. 《区域经济分析与政策设计》- 王顺洪

该书主要介绍了区域经济学的基本概念、模型和实证分析方法,以

及区域经济政策的设计和评价等方面的内容,是一本实用性较强的教材。

这些书籍涵盖了区域经济学的基本理论、分析方法和政策实践,

对于学习该领域的人士具有较高的参考价值。

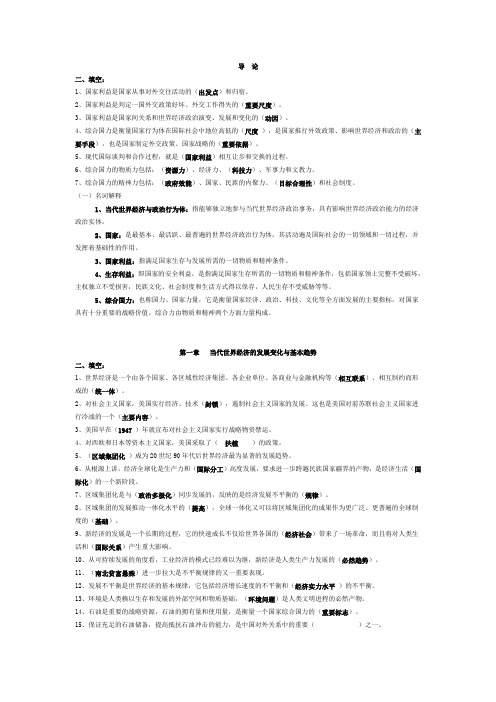

导论二、填空:1、国家利益是国家从事对外交往活动的(出发点)和归宿。

2、国家利益是判定一国外交政策好坏、外交工作得失的(重要尺度)。

3、国家利益是国家间关系和世界经济政治演变、发展和变化的(动因)。

4、综合国力是衡量国家行为体在国际社会中地位高低的(尺度),是国家推行外效政策、影响世界经济和政治的(主要手段),也是国家制定外交政策、国家战略的(重要依据)。

5、现代国际谈判和合作过程,就是(国家利益)相互让步和交换的过程。

6、综合国力的物质力包括:(资源力)、经济力、(科技力)、军事力和文教力。

7、综合国力的精神力包括:(政府效能)、国家、民族的内聚力、(目标合理性)和社会制度。

(一)名词解释1、当代世界经济与政治行为体:指能够独立地参与当代世界经济政治事务,具有影响世界经济政治能力的经济政治实体。

2、国家:是最基本、最活跃、最普遍的世界经济政治行为体,其活动遍及国际社会的一切领域和一切过程,并发挥着基础性的作用。

3、国家利益:指满足国家生存与发展所需的一切物质和精神条件。

4、生存利益:即国家的安全利益,是指满足国家生存所需的一切物质和精神条件,包括国家领土完整不受破坏,主权独立不受损害,民族文化、社会制度和生活方式得以保存,人民生存不受威胁等等。

5、综合国力:也称国力、国家力量,它是衡量国家经济、政治、科技、文化等全方面发展的主要指标,对国家具有十分重要的战略价值。

综合力由物质和精神两个方面力量构成。

第一章当代世界经济的发展变化与基本趋势二、填空:1、世界经济是一个由各个国家、各区域性经济集团、各企业单位、各商业与金融机构等(相互联系)、相互制约而形成的(统一体)。

2、对社会主义国家,美国实行经济、技术(封锁),遏制社会主义国家的发展。

这也是美国对前苏联社会主义国家进行冷战的一个(主要内容)。

3、美国早在(1947 )年就宣布对社会主义国家实行战略物资禁运。

4、对西欧和日本等资本主义国家,美国采取了(扶植)的政策。