生物英文文献.doc

- 格式:doc

- 大小:43.50 KB

- 文档页数:4

生物英语短篇作文高中作文Biological Diversity。

Biological diversity, or biodiversity, refers to the variety of life on earth, including the variety of species, ecosystems, and genetic diversity within species. It is essential for the functioning of ecosystems and the services they provide, such as food, clean water, and air, and for human well-being.Biodiversity is threatened by human activities such as habitat destruction, pollution, overexploitation of resources, and climate change. These activities have led to the extinction of many species and the degradation of ecosystems, which in turn threatens human well-being.To protect biodiversity, we need to take actions at different levels. At the individual level, we can reduce our ecological footprint by consuming less, using renewable energy, and supporting conservation efforts. At thecommunity level, we can promote sustainable practices, such as organic farming and eco-tourism, and protect natural habitats. At the national and international level, we need policies and regulations that promote sustainable development, protect endangered species and habitats, and address the root causes of biodiversity loss.Conserving biodiversity is not only a moral and ethical duty, but also a practical necessity for our survival and well-being. We depend on biodiversity for our food, medicines, and other resources, and for the services that ecosystems provide. By protecting biodiversity, we are also protecting our own future.In conclusion, biodiversity is a crucial aspect of our planet's health and well-being. It is threatened by human activities, but we can take action to protect it. By conserving biodiversity, we are not only protecting the natural world, but also our own future.。

生物给人类的科技贡献英文作文English:Biology has made significant contributions to technology in numerous ways. One of the most important ways is through the field of medicine, where biological discoveries have led to the development of vaccines, antibiotics, and various medical technologies that have saved countless lives. Biotechnology, a branch of biology, has also revolutionized many industries with advancements in genetic engineering, pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and environmental protection. The study of genetics has paved the way for personalized medicine and gene therapy, providing solutions to genetic disorders and improving the overall quality of healthcare. Furthermore, biomimicry, which involves learning from nature to design innovative technologies, has led to the creation of new materials, structures, and systems that are more efficient, sustainable, and resilient. Overall, biology continues to play a crucial role in driving technological advancements that benefit society as a whole.中文翻译:生物学在许多方面为技术的发展做出了重要贡献。

生物医学工程医疗仪器论文中英文资料外文翻译文献Present status and problems of domestic medical instrument engineering. Biomedical EngineehngIn recent years considerable progress has been achieved in domestic medical instrument engineering. Many plants and scientific-research organizations of machine-making and the defense industry have changed their profile toward production of medical equipment.However, medical equipment often meets a reluctant market because of funding cuts in health services. Medical organizations often cannot satisfy even their basic requirements for diagnostic and therapeutic devices.Also, health service organizations tend to buy foreign rather than domestic medical equipment because the former are easily available on the domestic market and prices for both are comparable because of inflation.The transition to a market economy in Russia has had substantial impact on the relations between domestic manufactur- ers and consumers of medical devices. The spectrum and quality of available items has been significantly extended in recentyears. It should be also noted that available models of medical devices are continuously updated, which makes them sufficiently competitive.Representative information on the updating dynamics of domestic medical equipment is summarized in Table 1. The data were provided by the VNIIMP-VITA Joint-Stock Company, which compiles a data bank of such information.Generally, new items account for 37% of total production of medical devices. Routinely produced devices (duration of production, 2-5 years) account for 28%. Medical devices of long-term production (5-10 years) account for 17% and obsolete nomenclature (devices produced for more than 10 years) accounts for 18%.It is seen from Table 1 that in recent years there has been considerable progress in the updating of production of medical equipment. For example, according to the VNIIMP-VITA Joint-Stock Company, the share of the items that have been produced for no longer than 5 years in 1988 did not exceed 35%, while now it is 65%. For the items that have been produced for more than 10 years such shares are 40 and 18%, respectively.Updating of produced medical devices was encouraged by the increase in the number of designers and manufacturers, particularly those of former defense industry facilities. In collaboration with foreign partners they set up joint ventures for producing medical equipment.Analysis of the updating of the various groups of medical equipment is of substantialinterest.It is seen from Table 1 that detoxication devices contribute dominantly to the group of items that have been updated within the standard period of up to 5 years (100% of production, including modern devices for hemodialysis and hemosorption).Comparatively high updating indices are observed for devices for functional diagnosis: 72% of these devices have been produced for no longer than 5 years, and obsolete devices account for only 9% of total production. However, it should be noted that although production of some obsolete devices has been terminated, equipment of similar functional capacity is still urgently needed.Relatively low updating indices are observed among the devices for intensive care and resuscitation: 16% of new items and comparatively many obsolete devices (26%). Among new models apparatuses for artificial lung ventilation are worth mention. However, some apparatuses, which have been developed long ago are still on the market because they have good performance, are quite reliable, and still are in demand. This reduces the updating index of the group as a whole.All-Russian Scientific-Research Institute for Medical Instrument Engineering, Rusaian Academy of Medical Sciences (VNIIMP-VITA Joint-Stock Company), Moscow. Translated from Meditsinskaya Tekhnika, No. 1, pp. 4-9, January-February, 1996. Original article submitted August 23, 1995.0006-3398/96/3001-0001515.00 y Plenum Publishing CorporationTABLE 1. Updating of Basic Groups of Medical Devices and Apparatuses (% of total nomenclature)这里有个表The lowest updating indices are observed for devices for examining a patient's body structures. These are: ophthalmological, otolaryngological, and anthropometric devices, endoscopes, etc. The share of obsolete devices is high (44%), while the devices which have been produced for no more than 5 years account for only 20% of total production.It should be noted that these results on medical equipment updating are important general estimates, although they do not take into consideration specific achievements and shortcomings in the production of individual items. Therefore, some corresponding amendments are required.Our survey of available information, including the VNIIMP-VITA Joint-Stock Company data bank, materials presented at various exhibitions, and recent literature, shows that domestic medical industry has developed a number of original medical devices and apparatuses which were designed to replace similar obsolete models. However, many types of important and necessary medical devices still do not meet contemporary requirements, and some types of devices are not produced at all.For example, in recent years production of some sophisticated medical devices (apparatuses for intensive care, resuscitation, and anesthesiology; devices for artificial lung ventilation, respiratory narcosis devices, extracorporeal circulation) significantly rose, particularly at the former defense industry facilities, and their quality has been significantly improved. The functional performance of the devices is generally on par with foreign analogs.Perfusion units have also been improved and their production has expanded. This allowed the demand of the health service organizations for such equipment to be satisfied completely. Modern domestic hemodialysis devices (Renart-10, Renan- 10RT, etc.) have beendeveloped and brought into wide clinical practice.The development and production of diagnostic magnetic resonance imaging systems (Obraz-3, TOROS) are considerable breakthroughs in domestic medical industry. This substantially extends diagnostic capacities of many health service organizations and provides them with topical diagnosis previously unavailable domestically, although it is quite common in developed foreign countries.Domestic medical industry has begun production of pulse oximeters; these are of particular use in surgery and resuscita-tion. This bridged a substantial gap in the spectrum of available domestic medical devices.The Bilitest bilirubin meter, which has been recently developed and produced in Russia, fully meets the requirements of maternity and children's hospitals in devices for diagnosing jaundice.A high-standard radioimmunochemical laboratory was opened at the VNIIMP-VITA Joint-Stock Company to supply customers with necessary radioimmunochemical assay kits.A number of high-quality medical devices and instruments have been developed at the electronic industry plants andinstitutes. The following devices are particularly worthy of mention:- artificial cardiac valves of the Emitron Plant, which are on par with the best foreign analogs;- pH meters (Istok State Scientific-Manufacturing Association);- Ikar long-term (up to 24 h) cardiomonitors with electronic memory (Kometa Central Scientific-Manufacturing Association);- radiothermographs and racliothermoscopes for detecting deeply located thermal fields in the human body (Oktyabr' Manufacturing Association and Design Bureau for Ecological and Medical Equipment);- original thermal imaging system (Institute of Radioelectronics and Automatics, Russian Academy of Sciences; OPTROS, Ltd.);- original computer-assisted system Cardiac Rhythms for monitoring oatient condition and pulsimetry (Institute of Chemical Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences; Ekos, Ltd.);- video system for endoscopic imaging (Zenit Scientific-Manufacturing A~sociation; Elektron Scientific-Research and Manufacturing Association);- streamlined technology for producing disposable and reusable syringes, injection needles, and surgical threads.A number of other problems of domestic medical instrument-making industry have been successfully solved in recent years.For example, the number and quality of therapeutic devices, particularly for laser therapy, is quite sufficient. Research studies are carried out by many organizations including former defense industry facilities. Technologies which have been developed for other purposes give fruitful results in medical industry.According to our data, more than 150 models of such medical devices have been developed over the last 5 years. Some 100 of them are commercially available. Although domestic medical devices are often superior ot foreign analogs in terms of working performance and they are definitely less expensive, many of them are not in short demand and are virtually not used.However, this activity in many other areas of medical instrument engineering cannot beconsidered as sufficiently successful and rational.It should be noted that many newly developed models of domestic medical devices compare unfavorably with foreign analogs. This is particularly the case for X-ray and ultrasonic devices, electrocardiographic monitors, laboratory equipment, etc. Nevertheless, according to the VNIIMP-VITA Joint-Stock Company databank, certain positive trends have been observed in recent years even in these areas. However, most problems still remain unsettled and the conditions required to solve them have not yet been established.It is important to note that the serially produced X-ray apparatus RUM-20 (Mosrentgen Joint-Stock Company) has been significantly updated. The updated model RUM-20M-SG312 is commercially available in combination with the Sapfir domestic image intensifier or an image intensifier of a French manufacturer. The Kruiz fiat image intensifier has been developed at theAll-Russian Scientific-Research Institute for Medical Instrument Engineering in collaboration with MELZ Manufacturing Association and Mosrentgen Joint-Stock Company. This device is designed to replace existing fluorescent screens in the X-ray diagnostic apparatuses RUM-10, RUM-20, RUM-20M, and others. The use of the Kruiz image intensifier significantly increases image information content and allows threefold decrease in the radiation load on patients and medical personnel.The G 202-5 system for lit-par-lit raster imaging of patients in lying position has been developed at the Mosrentgen Joint-Stock Company. This device is commercially available with the PURS power source. It allows both manual and automatic X-ray photography and organ-oriented X-ray examination.The RTS-61 mobile X-ray video diagnostic apparatus has been developed at the Elektron Scientific-Research and Manufacturing Association. This device is designed to be used in surgery, orthopedics, and traumatology.Among the defense industry facilities which have reoriented their production to medical market the Scientific-Research Institute for Electromechanics (Istra) is worth mention. In collaboration with Phillips (Germany) and borrowing their technology and circuitry, the Institute for Electromechanics developed the Mammodiagnost mammographic scanner, which meets international standards of operating performance.The Rentgen-48 X-ray tomographic diagnostic systems with a rotary support table and the Rentgen-60 X-ray diagnostic systems with a remote control support table have been developed at the Sevkavrentgen Plant and received positive recognition by practicing physicians.The models of X-ray diagnostic devices listed above are examples of achievements of domestic medical industry.However, many important and significant problems of the development of domestic medical X-ray equipment remain unsettled, and it is unreasonable to expect that they will be solved in the foreseeable future unless special measures are taken.For example, the most common RUM-20 X-ray apparatuses with the Sapfir image intensifier are equipped with the obsolete X-ray image converter REP-1. To replace the REP-1 image converter, the Moscow Plant for Electronic Tubes has developed the Buer image converter of improved design. This device offers better image contrast, reduced clark background noise, and has an output fiberoptic window of improved design. However, the Buer image converter is not yet commercially available.Digital X-ray diagnostic devices are not yet commercially available from domesticmanufacturers either.The Design Bureau for Medical Engineering in collaboration with Medtekh, Ltd. (Novosibirsk) have developed the Diaskan X-ray digital scanner. Serial production of this device is in progress at the Design Bureau for Medical Engineering.However, devices of sufficient quality are not yet commercially available.Domestic medical industry does not produce X-ray tomographs. Their production in Chelyabinsk has been suspended.Electrocardiographic monitors are very important devices for functional diagnosis. However, domestic medical industry fails substantially behind leading foreign manufacturers and there is a disproportion in the development and production of necessary devices and apparatuses. Many automatic systems for ECG processing, including syndromal diagnosis, have been developed, but they trove not been tested and are of little demand. However, simple three-channel electrocardiographs of mass- scale application are not produced by domestic manufacturers.Foreign manufacturers offer various ultrasonic scanners and sophisticated imaging systems. Domestic manufacturers produce only simple devices with manual sector-by-sector scanning and a few simplified models with linear electronic scanning.Some positive results have been achieved in the development of endoscopic devices. These achievements are mainly due to the collaboration between LOMO and some companies from Japan. However, even these devices require further improvement of quality and reliability.Although the level of production of domestic laboratory equipment has noticeably risen in recent years, it is still too little to meet the demand. The number of organizations involved in the development of such equipment has risen. However, the available devices are simple and have limited functional capacity. Many important devices (e.g., automatic analyzers and simple routine devices) are not produced at all.Devices for blood transfusion and preparing blood substitute solutions are still in short supply (40 million items have been produced, while the demand is 200 million). The demand in dialyzers and polymer infusion systems reaches 100 and 150 million items, respectively, although such systems are not produced at all.The correspondence between production and demand, quality and technical performance, and adequate testing of medical production are put in the forefront under conditions of a market economy. The problem of competition with foreign manufacturers is also quite important because of increasing import of medical equipment and reduced sale of the production of domestic manufacturers. In this connection, the following circumstances should be taken into consideration.There is a considerable disproportion between production and demand of some groups of medical devices. For example, there is :~ huge surplus of laser therapeutic devices and their excessive development. Systems for syndromal electrocardiographic diagnosis, magnetotherapy, and electrostimulation are also in excessive supply. However, simple electrocardiographs, routine laboratory equipment, and some other ordinary but necessary devices of mass-scale application are not produced by domestic manufacturers. These disadvantages cause significant economic losses and present difficulties in the development of health service. Domestic and foreign experience show that these problems can be solved by adequate marketing, but this is in its infancy in the domestic medical industry.It should be noted that foreign companies place special emphasis on marketing and market research. They evaluate actual and pending demand as well as consumer requirements. Thefeedback between consumer and manufacturer gives valuable information on the improvement of the product quality and working performance. The marketing service in most leading companies is of paramount importance. The development of a new product often starts from marketing survey rather than from engineering or design research. Many domestic organizations of medical instrument engineering require cardinal measures for increasing the level of marketing.Testing of medical devices also requires substantial improvement. Considerable experience of foreign manufacturers of medical equipment should be taken into account. It should be noted, however, that this experience is often neglected by domestic manufacturers. Technical testing of medical equipment in foreign companies is usually carried out by independent laboratories which assess performance and quality. The specialists of the laboratories may also give recommendations for further improvement of the tested equipment. The basic goal of the testing is to check if the performance of the device matches its specifications and to conclude if the device can be used in medical organizations. However, the specialists of the laboratories usually go beyond this goal and issue comparative reviews of products of different companies. Such reviews contain the following information:- description of tested device, its specifications, and price;- results of technical testing, correspondence between specifications and actual performance, advantages and disadvan- tages, recommendations for improvement (if necessary);- comparative analysis of similar devices and apparatuses produced by different manufacturers. Such analysis is usually concluded by a most preferable model, which is recommended to medical organizations on the basis of functional capacity, reliability, and economic reasons.In the USA, activity of testing laboratories is controlled by governmental, nongovernmental, and independent nonprofit organizations.In Russia, the problem of balance between the demand in medical devices, their production by domestic manufacturers, and import is of considerable importance.The opinion of the Head of the Department of Medical Industry, Russian Ministry of Health and Medical Industry, Yu. F. Doshchitsin, which was published in the weekly "Meditsinskii Biznes" (No. 9, 1995), is that the requirements of Russian medical market must be met by domestic devices, including products of high technology. Russian medicine should not rely on imported devices alone. We certainly agree with this opinion.The total volume of medical equipment purchased from abroad is presently several times greater than purchases from domestic manufacturers. This situation is definitely unacceptable. Cardinal measures are required to boost and stimulate economically domestic manufacturers of medical equipment. This is particularly important for manufacturers of life support systems and devices for military medicine.However, positive aspects of contacts with foreign manufacturers of medical equipment should not be disregarded. International cooperation is very common in foreign practice, but it is clearly insufficient in Russia.International cooperation in medical industry is particularly vital in such areas as computer technology, microprocessors, and electronic engineering. Lack of sufficiently high-quality domestic computers and microprocessors presents considerable problems in the development of sophisticated medical devices and apparatuses.In recent years a number of domestic organizations established joint ventures withleading foreign manufacturers of medical devices. These joint ventures produce high-technology devices on the basis of imported circuitry, modules, and individual finished units. For example, VNIIMP-VITA produces ultrasonic doppler scanners, Kursk Manufacturing Association Pribor in collaboration with Frezenius (Germany) produces mobile apparatuses for hemodialysis and hemosorption, LOMO and some companies from Japan established a joint venture for manufacturing flexible endoscopes of improved design, Moscow Manufac- turing Association EMA produces ultrasonic diagnostic devices, etc.It seems reasonable to continue and extend mutually profitable contacts between domestic and foreign manufacturers of medical equipment.Active participation and patronage of the Russian Ministry of Health and Medical Industry as well as the Russian Government and local authorities are needed to solve the problems of medical industry listed above and to implement programs of development and production of high-quality domestic medical devices.References[1] V. A. Viktorov,V. P. gundarov,A. P. yurkevich. Present status and problems of domestic medical instrument engineering. Biomedical Engineehng~ V oL 30, No. 1, 1996.[2]All-Russian Scientific-Research Institute for Medical Instrument Engineering, Rusaian Academy of Medical Sciences (VNIIMP-VITA Joint-Stock Company), Moscow. Translated from Meditsinskaya Tekhnika, No. 1, pp. 4-9, January-February, 1996. Original article submitted August 23, 1995.国内医学仪器工程的现状和存在的问题近年来,国内在工程医疗器械实现取得了很大进展。

食品微生物检验英文参考文献1.贾英民主编,食品微生物学.高等职业教育教材,北京:中国轻工业出版社,2004.91. jiayingmin, food microbiology Textbooks for higher vocational education, Beijing: China Light Industry Press, September 20042.万萍主编,食品微生物基础与实验技术.高职高专食品类教材系列,北京:科学出版社,2. edited by Wan Ping, fundamentals and experimental techniques of food microbiology Food textbook series for higher vocational colleges, Beijing: Science Press,2004two thousand and four3.翁连海主编﹐食品微生物基础高职教材,北京:高等教育出版社,2005.43. Weng Lianhai, editor in chief, higher vocational textbook of food microbiology, Beijing: Higher Education Press, April 20054.苏世彦.食品微生物检验手册.北京:中国轻工业出版社,1998.104. sushiyan. Manual for microbiological examination of food. Beijing: China Light Industry Press, 1998.105.牛天贵.食品微生物学实验技术.北京:中国农业大学出版社,2002.85. Niu Tiangui. Experimental technology of food microbiology Beijing: China Agricultural University Press, August 20026.高鼎主编,食品微生物学,北京:中国商业出版社,1996.56. Gao Ding, chief editor, food microbiology, Beijing: China business press, 1996.5 7.谢梅英主编,食品微生物学,北京:中国轻工业出版社,2004.57. Xie Meiying, food microbiology, Beijing: China Light Industry Press, May 20048.中华人民共和国国家标准.食品卫生检验方法(微生物部分).北京:中国标准出版社,8. national standards of the people's Republic of China Methods for hygienic inspection of food (microbiological part) Beijing: China Standards Press,2003two thousand and three9.杨洁彬.食品微生物学.北京:北京农业大学出版社,19959. yangjiebin. Food microbiology Beijing: Beijing Agricultural University Press, 199510.沈萍主编﹒微生物学北京:高等教育出版社,200011.高东主编﹒微生物遗传学济南:山东大学出版社,199610. microbiology, edited by Shenping, Beijing: Higher Education Press, 200011 Gao Dong. Microbial genetics. Jinan: Shandong University Press, 1996。

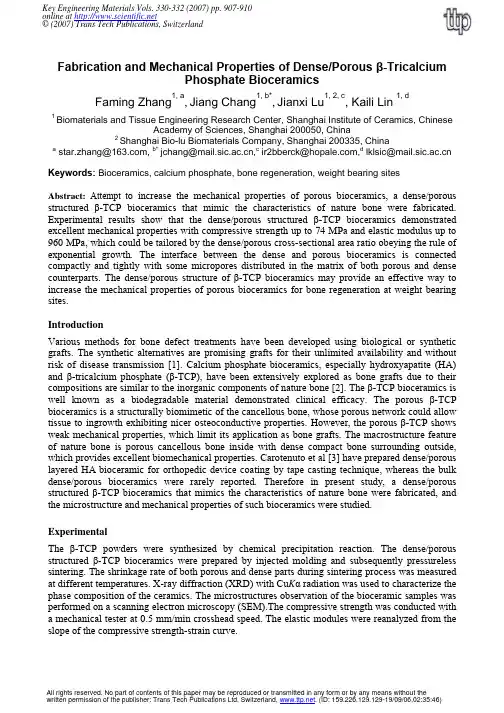

Fabrication and Mechanical Properties of Dense/Porous β-TricalciumPhosphate BioceramicsFaming Zhang1, a , Jiang Chang 1, b*, Jianxi Lu 1, 2, c , Kaili Lin 1, d 1 Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering Research Center, Shanghai Institute of Ceramics, ChineseAcademy of Sciences, Shanghai 200050, China 2 Shanghai Bio-lu Biomaterials Company, Shanghai 200335, China a star.zhang@, b* jchang@,c ir2bberck@,d lklsic@Keywords: Bioceramics, calcium phosphate, bone regeneration, weight bearing sitesAbstract: Attempt t o increase the mechanical properties of porous bioceramics, a dense/porous structured β-TCP bioceramics that mimic the characteristics of nature bone were fabricated. Experimental results show that the dense/porous structured β-TCP bioceramics demonstrated excellent mechanical properties with compressive strength up to 74 MPa and elastic modulus up to 960 MPa, which could be tailored by the dense/porous cross-sectional area ratio obeying the rule of exponential growth. The interface between the dense and porous bioceramics is connected compactly and tightly with some micropores distributed in the matrix of both porous and dense counterparts. The dense/porous structure of β-TCP bioceramics may provide an effective way to increase the mechanical properties of porous bioceramics for bone regeneration at weight bearing sites.IntroductionVarious methods for bone defect treatments have been developed using biological or synthetic grafts. The synthetic alternatives are promising grafts for their unlimited availability and without risk of disease transmission [1]. Calcium phosphate bioceramics, especially hydroxyapatite (HA) and β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), have been extensively explored as bone grafts due to their compositions are similar to the inorganic components of nature bone [2]. The β-TCP bioceramics is well known as a biodegradable material demonstrated clinical efficacy. The porous β-TCP bioceramics is a structurally biomimetic of the cancellous bone, whose porous network could allow tissue to ingrowth exhibiting nicer osteoconductive properties. However, the porous β-TCP shows weak mechanical properties, which limit its application as bone grafts. The macrostructure feature of nature bone is porous cancellous bone inside with dense compact bone surrounding outside, which provides excellent biomechanical properties. Carotenuto et al [3] have prepared dense/porous layered HA bioceramic for orthopedic device coating by tape casting technique, whereas the bulk dense/porous bioceramics were rarely reported. Therefore in present study, a dense/porous structured β-TCP bioceramics that mimics the characteristics of nature bone were fabricated, and the microstructure and mechanical properties of such bioceramics were studied.ExperimentalThe β-TCP powders were synthesized by chemical precipitation reaction. The dense/porous structured β-TCP bioceramics were prepared by injected molding and subsequently pressureless sintering. The shrinkage rate of both porous and dense parts during sintering process was measured at different temperatures. X-ray diffraction (XRD) with Cu K α radiation was used to characterize the phase composition of the ceramics. The microstructures observation of the bioceramic samples was performed on a scanning electron microscopy (SEM).The compressive strength was conducted with a mechanical tester at 0.5 mm/min crosshead speed. The elastic modules were reanalyzed from the slope of the compressive strength-strain curve.All rights reserved. No part of contents of this paper may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher: Trans Tech Publications Ltd, Switzerland, . (ID: 159.226.129.129-19/09/06,02:35:46)Results and DiscussionThe major problem in preparation of the dense/porous bioceramics is the interface adhesion between the dense and porous parts because of their different shrinkage rate during sintering process. The shrinkage rate of dense and porous bioceramics at different temperatures was measured and the results are shown in Fig.1. It can be noticed that the porous β-TCP bioceramics exhibit much higher shrinkage rate than the dense counterpart. The porous bioceramics shows about 23% shrinkage in radial direction; in contrast, the dense bioceramics presents about 17% shrinkage. It can be calculated that from 850 o C to 1100 o C, the porous β-TCP bioceramics shows about 17% shrinkage rate and almost the same with that of the dense counterpart from 600 o C to 1100 o C. So as to avoiding the shrinkage differences, the porous β-TCP bioceramics were pre-sintered at 850 o C, then the dense bioceramics were injected surrounding the porous ceramics, finally the composites were pressureless sintered at 1100 o C for 5 hours and the dense/porous structured β-TCP bioceramics were obtained.Fig.1 The radial shrinkage rate of the porous and dense β-TCP bioceramicsThe phase composition of the as prepared bioceramics was analyzed by X-ray diffraction. The XRD results show that the high temperature sintered β-TCP preserved their original β phase without transform into their α-TCP phase, as shown in Fig.2. Because the α-TCP though bioactive, have proven less useful as bone regeneration materials due to their excessively high resorption rate than the β-TCP phase. And none of the other impurity phases can be detected in the XRD patterns; resultantly, high purity β-TCP bioceramics were prepared.Fig.2 X-ray diffraction pattern of the prepared bioceramics.Fig.3 shows the optical and SEM micrographs of the prepared dense/porous β-TCP bioceramics samples. It is clear to see that the inner porous structure mimics the cancellous bone to some extent, and outer side dense structure mimics the compact bone, as shown in Fig.3(a) and indicated by theS h i n k a g e (%)Temperature (o C)1020304050607080100200300400500600 2theta (deg.)I n t e n s i t y (c p s )arrows. Fig.3 (b) shows the interface of the dense/porous β-TCP bioceramic, it can be found that the interface between the dense and porous bioceramics is connected compactly and tightly. In the porous part, the macropore size is about 500 μm in diameter; the diameter of the interconnected pores is about 100 μm. Additionally, the porosity of the porous parts is about 72%, and the interconnectivity is more than 95%. The microstructure of the macroporous wall was shown in Fig.3(c); it is obvious that there are some micropores with diameter of 1 μm distributed uniformly in the porous wall. As the results, the microstructure of porous part of the bioceramics is a combination of macroporous and microporous. Contrastively, the microstructure of the dense bioceramics shows refined particle size and few micropores, as exhibited in Fig.3(d). The dense compact part is much denser than the porous cancellous part.Fig.3 The dense/porous β-TCP bioceramic sample (a), the microstructure of dense/porous interface(b), the macroporous wall (c) and dense compact bone (d).The variation of the compressive strength and Elastic modulus of the bioceramics with different dense/porous cross-sectional area ratio (S dense /S porous ) was illustrated in Fig 4. It is exhibited that the compressive strength increases from 10 MPa to 74 MPa with the dense/porous ratio from 0.1 to 4.7 obeying rule of exponential growth. And the elastic modulus has been increased form 180 MPa to 960 MPa with the dense/porous ratio increment, also following exponential growth. Evidently, the value of the porous bioceramics is only about 2.0 MPa and the elastic modulus is about 20 MPa, indicated by the square in Fig.4. It has been achieved about 5 to 37 times increment in the mechanical properties by the dense/porous structure design. The mechanical properties of the dense/porous bioceramics could be tailored by the dense/porous cross-sectional area ratio.Porous materials always have poor mechanical properties. Applications of calcium phosphates in the body have been limited by their low strength and numerous techniques have been investigated in attempts to retain their useful bioactive properties whilst providing more suitable mechanical properties for particular applications. These include the reinforcement of β-TCP using HA fiber orbioglass additives [4, 5]; however these techniques are limited for the porous calcium phosphate Compact bone Cancellousbone (b)(c) (d)using in the load bearing sites’ bone regeneration. In this study, excellent mechanical properties of the porous β-TCP bioceramics have been achieved by the dense/porous structured design. The compressive strength of human femoral cancellous bone, weight bearing sites, is in the range of 25~90 MPa, so the dense/porous structured β-TCP is comparable to the strength of human femoral cancellous bone. The high interconnective porous structure of the dense/porous β-TCP bioceramics could allow the tissue ingrowths, and the dense structure could bear the load to some extent. The dense/porous structure of β-TCP bioceramics may provide a simple but effective way to increase the mechanical properties of porous bioceramics for the bone regeneration applications at weight bearing sites.Fig.4 The variation of the compressive strength and elastic modulus of the bioceramics withdifferent dense/porous cross-sectional area ratio. ConclusionsThe dense/porous structured β-TCP bioceramics were prepared and revealed excellent mechanical properties with compressive strength from 10 to 74 MPa and elastic modulus from 180 to 960 MPa, which is 5 to 37 times higher than that of the pure porous β-TCP and comparable to the strength of human femoral cancellous bone. The interface between the dense and porous bioceramics is connected compactly and tightly. The dense/porous structure of β-TCP bioceramics may provide a simple but effective way to increase the mechanical properties of porous bioceramics for weight bearing site’s bone regeneration.AcknowledgementFinancial supports from the Shanghai Postdoctoral Scientific Key Program and the Science & Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality of China (No.04DZ52043) are greatly acknowledged.References:[1] Niedhart C, Maus U, Redmann E, Schmidt-Rohlfing B, Niethard FU, Siebert CH: J BiomedMater Res Vol. 65A (2003), p.17[2] Hench Larry L: Journal of the American Ceramic Society Vol. 81(1998), p.1705[3] Carotenuto G: Advanced Performance Materials Vol. 5(1998), p.171[4] Hassna R. R. Ramay, Zhang M.: Biomaterials Vol. 25(2004), p.5171[5] Ashizuka M, Nakatsu M, Ishida E: Journal of the Ceramic Society of Japan, v 98(1990), p.204. 01020304050607080012345020040060080010001200E l a st i c M o d u l u s (M P a ) C o m p r e s s i v e S t r e n g h (M P a )S dense /S porous。

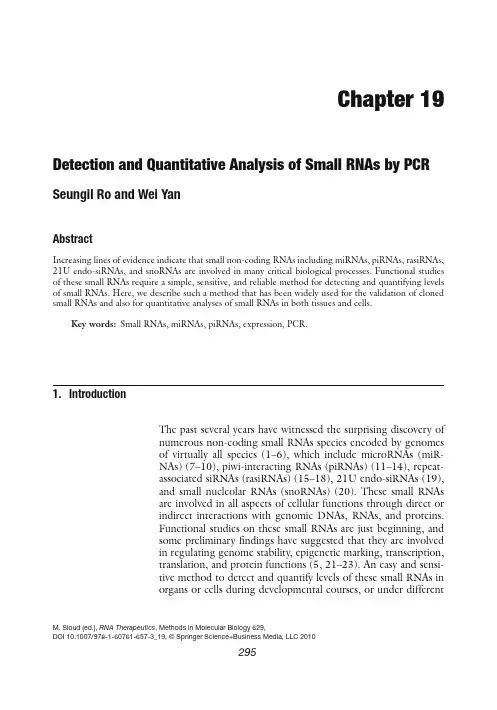

Chapter19Detection and Quantitative Analysis of Small RNAs by PCR Seungil Ro and Wei YanAbstractIncreasing lines of evidence indicate that small non-coding RNAs including miRNAs,piRNAs,rasiRNAs, 21U endo-siRNAs,and snoRNAs are involved in many critical biological processes.Functional studies of these small RNAs require a simple,sensitive,and reliable method for detecting and quantifying levels of small RNAs.Here,we describe such a method that has been widely used for the validation of cloned small RNAs and also for quantitative analyses of small RNAs in both tissues and cells.Key words:Small RNAs,miRNAs,piRNAs,expression,PCR.1.IntroductionThe past several years have witnessed the surprising discovery ofnumerous non-coding small RNAs species encoded by genomesof virtually all species(1–6),which include microRNAs(miR-NAs)(7–10),piwi-interacting RNAs(piRNAs)(11–14),repeat-associated siRNAs(rasiRNAs)(15–18),21U endo-siRNAs(19),and small nucleolar RNAs(snoRNAs)(20).These small RNAsare involved in all aspects of cellular functions through direct orindirect interactions with genomic DNAs,RNAs,and proteins.Functional studies on these small RNAs are just beginning,andsome preliminaryfindings have suggested that they are involvedin regulating genome stability,epigenetic marking,transcription,translation,and protein functions(5,21–23).An easy and sensi-tive method to detect and quantify levels of these small RNAs inorgans or cells during developmental courses,or under different M.Sioud(ed.),RNA Therapeutics,Methods in Molecular Biology629,DOI10.1007/978-1-60761-657-3_19,©Springer Science+Business Media,LLC2010295296Ro and Yanphysiological and pathophysiological conditions,is essential forfunctional studies.Quantitative analyses of small RNAs appear tobe challenging because of their small sizes[∼20nucleotides(nt)for miRNAs,∼30nt for piRNAs,and60–200nt for snoRNAs].Northern blot analysis has been the standard method for detec-tion and quantitative analyses of RNAs.But it requires a relativelylarge amount of starting material(10–20μg of total RNA or>5μg of small RNA fraction).It is also a labor-intensive pro-cedure involving the use of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis,electrotransfer,radioisotope-labeled probes,and autoradiogra-phy.We have developed a simple and reliable PCR-based methodfor detection and quantification of all types of small non-codingRNAs.In this method,small RNA fractions are isolated and polyAtails are added to the3 ends by polyadenylation(Fig.19.1).Small RNA cDNAs(srcDNAs)are then generated by reverseFig.19.1.Overview of small RNA complementary DNA(srcDNA)library construction forPCR or qPCR analysis.Small RNAs are polyadenylated using a polyA polymerase.ThepolyA-tailed RNAs are reverse-transcribed using a primer miRTQ containing oligo dTsflanked by an adaptor sequence.RNAs are removed by RNase H from the srcDNA.ThesrcDNA is ready for PCR or qPCR to be carried out using a small RNA-specific primer(srSP)and a universal reverse primer,RTQ-UNIr.Quantitative Analysis of Small RNAs297transcription using a primer consisting of adaptor sequences atthe5 end and polyT at the3 end(miRTQ).Using the srcD-NAs,non-quantitative or quantitative PCR can then be per-formed using a small RNA-specific primer and the RTQ-UNIrprimer.This method has been utilized by investigators in numer-ous studies(18,24–38).Two recent technologies,454sequenc-ing and microarray(39,40)for high-throughput analyses of miR-NAs and other small RNAs,also need an independent method forvalidation.454sequencing,the next-generation sequencing tech-nology,allows virtually exhaustive sequencing of all small RNAspecies within a small RNA library.However,each of the clonednovel small RNAs needs to be validated by examining its expres-sion in organs or in cells.Microarray assays of miRNAs have beenavailable but only known or bioinformatically predicted miR-NAs are covered.Similar to mRNA microarray analyses,the up-or down-regulation of miRNA levels under different conditionsneeds to be further validated using conventional Northern blotanalyses or PCR-based methods like the one that we are describ-ing here.2.Materials2.1.Isolation of Small RNAs, Polyadenylation,and Purification 1.mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit(Ambion).2.Phosphate-buffered saline(PBS)buffer.3.Poly(A)polymerase.4.mirVana Probe and Marker Kit(Ambion).2.2.Reverse Transcription,PCR, and Quantitative PCR 1.Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR(Invitrogen).2.miRTQ primers(Table19.1).3.AmpliTaq Gold PCR Master Mix for PCR.4.SYBR Green PCR Master Mix for qPCR.5.A miRNA-specific primer(e.g.,let-7a)and RTQ-UNIr(Table19.1).6.Agarose and100bp DNA ladder.3.Methods3.1.Isolation of Small RNAs 1.Harvest tissue(≤250mg)or cells in a1.7-mL tube with500μL of cold PBS.T a b l e 19.1O l i g o n u c l e o t i d e s u s e dN a m eS e q u e n c e (5 –3 )N o t eU s a g em i R T QC G A A T T C T A G A G C T C G A G G C A G G C G A C A T G G C T G G C T A G T T A A G C T T G G T A C C G A G C T A G T C C T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T V N ∗R N a s e f r e e ,H P L CR e v e r s e t r a n s c r i p t i o nR T Q -U N I r C G A A T T C T A G A G C T C G A G G C A G GR e g u l a r d e s a l t i n gP C R /q P C Rl e t -7a T G A G G T A G T A G G T T G T A T A G R e g u l a r d e s a l t i n gP C R /q P C R∗V =A ,C ,o r G ;N =A ,C ,G ,o r TQuantitative Analysis of Small RNAs299 2.Centrifuge at∼5,000rpm for2min at room temperature(RT).3.Remove PBS as much as possible.For cells,remove PBScarefully without breaking the pellet,leave∼100μL of PBS,and resuspend cells by tapping gently.4.Add300–600μL of lysis/binding buffer(10volumes pertissue mass)on ice.When you start with frozen tissue or cells,immediately add lysis/binding buffer(10volumes per tissue mass)on ice.5.Cut tissue into small pieces using scissors and grind it usinga homogenizer.For cells,skip this step.6.Vortex for40s to mix.7.Add one-tenth volume of miRNA homogenate additive onice and mix well by vortexing.8.Leave the mixture on ice for10min.For tissue,mix it every2min.9.Add an equal volume(330–660μL)of acid-phenol:chloroform.Be sure to withdraw from the bottom phase(the upper phase is an aqueous buffer).10.Mix thoroughly by inverting the tubes several times.11.Centrifuge at10,000rpm for5min at RT.12.Recover the aqueous phase carefully without disrupting thelower phase and transfer it to a fresh tube.13.Measure the volume using a scale(1g=∼1mL)andnote it.14.Add one-third volume of100%ethanol at RT to the recov-ered aqueous phase.15.Mix thoroughly by inverting the tubes several times.16.Transfer up to700μL of the mixture into afilter cartridgewithin a collection bel thefilter as total RNA.When you have>700μL of the mixture,apply it in suc-cessive application to the samefilter.17.Centrifuge at10,000rpm for15s at RT.18.Collect thefiltrate(theflow-through).Save the cartridgefor total RNA isolation(go to Step24).19.Add two-third volume of100%ethanol at RT to theflow-through.20.Mix thoroughly by inverting the tubes several times.21.Transfer up to700μL of the mixture into a newfilterbel thefilter as small RNA.When you have >700μL of thefiltrate mixture,apply it in successive appli-cation to the samefilter.300Ro and Yan22.Centrifuge at10,000rpm for15s at RT.23.Discard theflow-through and repeat until all of thefiltratemixture is passed through thefilter.Reuse the collectiontube for the following washing steps.24.Apply700μL of miRNA wash solution1(working solu-tion mixed with ethanol)to thefilter.25.Centrifuge at10,000rpm for15s at RT.26.Discard theflow-through.27.Apply500μL of miRNA wash solution2/3(working solu-tion mixed with ethanol)to thefilter.28.Centrifuge at10,000rpm for15s at RT.29.Discard theflow-through and repeat Step27.30.Centrifuge at12,000rpm for1min at RT.31.Transfer thefilter cartridge to a new collection tube.32.Apply100μL of pre-heated(95◦C)elution solution orRNase-free water to the center of thefilter and close thecap.Aliquot a desired amount of elution solution intoa1.7-mL tube and heat it on a heat block at95◦C for∼15min.Open the cap carefully because it might splashdue to pressure buildup.33.Leave thefilter tube alone for1min at RT.34.Centrifuge at12,000rpm for1min at RT.35.Measure total RNA and small RNA concentrations usingNanoDrop or another spectrophotometer.36.Store it at–80◦C until used.3.2.Polyadenylation1.Set up a reaction mixture with a total volume of50μL in a0.5-mL tube containing0.1–2μg of small RNAs,10μL of5×E-PAP buffer,5μL of25mM MnCl2,5μL of10mMATP,1μL(2U)of Escherichia coli poly(A)polymerase I,and RNase-free water(up to50μL).When you have a lowconcentration of small RNAs,increase the total volume;5×E-PAP buffer,25mM MnCl2,and10mM ATP should beincreased accordingly.2.Mix well and spin the tube briefly.3.Incubate for1h at37◦C.3.3.Purification 1.Add an equal volume(50μL)of acid-phenol:chloroformto the polyadenylation reaction mixture.When you have>50μL of the mixture,increase acid-phenol:chloroformaccordingly.2.Mix thoroughly by tapping the tube.Quantitative Analysis of Small RNAs3013.Centrifuge at10,000rpm for5min at RT.4.Recover the aqueous phase carefully without disrupting thelower phase and transfer it to a fresh tube.5.Add12volumes(600μL)of binding/washing buffer tothe aqueous phase.When you have>50μL of the aqueous phase,increase binding/washing buffer accordingly.6.Transfer up to460μL of the mixture into a purificationcartridge within a collection tube.7.Centrifuge at10,000rpm for15s at RT.8.Discard thefiltrate(theflow-through)and repeat until allof the mixture is passed through the cartridge.Reuse the collection tube.9.Apply300μL of binding/washing buffer to the cartridge.10.Centrifuge at12,000rpm for1min at RT.11.Transfer the cartridge to a new collection tube.12.Apply25μL of pre-heated(95◦C)elution solution to thecenter of thefilter and close the cap.Aliquot a desired amount of elution solution into a1.7-mL tube and heat it on a heat block at95◦C for∼15min.Open the cap care-fully because it might be splash due to pressure buildup.13.Let thefilter tube stand for1min at RT.14.Centrifuge at12,000rpm for1min at RT.15.Repeat Steps12–14with a second aliquot of25μL ofpre-heated(95◦C)elution solution.16.Measure polyadenylated(tailed)RNA concentration usingNanoDrop or another spectrophotometer.17.Store it at–80◦C until used.After polyadenylation,RNAconcentration should increase up to5–10times of the start-ing concentration.3.4.Reverse Transcription 1.Mix2μg of tailed RNAs,1μL(1μg)of miRTQ,andRNase-free water(up to21μL)in a PCR tube.2.Incubate for10min at65◦C and for5min at4◦C.3.Add1μL of10mM dNTP mix,1μL of RNaseOUT,4μLof10×RT buffer,4μL of0.1M DTT,8μL of25mM MgCl2,and1μL of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase to the mixture.When you have a low concentration of lig-ated RNAs,increase the total volume;10×RT buffer,0.1M DTT,and25mM MgCl2should be increased accordingly.4.Mix well and spin the tube briefly.5.Incubate for60min at50◦C and for5min at85◦C toinactivate the reaction.302Ro and Yan6.Add1μL of RNase H to the mixture.7.Incubate for20min at37◦C.8.Add60μL of nuclease-free water.3.5.PCR and qPCR 1.Set up a reaction mixture with a total volume of25μL ina PCR tube containing1μL of small RNA cDNAs(srcD-NAs),1μL(5pmol of a miRNA-specific primer(srSP),1μL(5pmol)of RTQ-UNIr,12.5μL of AmpliTaq GoldPCR Master Mix,and9.5μL of nuclease-free water.ForqPCR,use SYBR Green PCR Master Mix instead of Ampli-Taq Gold PCR Master Mix.2.Mix well and spin the tube briefly.3.Start PCR or qPCR with the conditions:95◦C for10minand then40cycles at95◦C for15s,at48◦C for30s and at60◦C for1min.4.Adjust annealing Tm according to the Tm of your primer5.Run2μL of the PCR or qPCR products along with a100bpDNA ladder on a2%agarose gel.∼PCR products should be∼120–200bp depending on the small RNA species(e.g.,∼120–130bp for miRNAs and piRNAs).4.Notes1.This PCR method can be used for quantitative PCR(qPCR)or semi-quantitative PCR(semi-qPCR)on small RNAs suchas miRNAs,piRNAs,snoRNAs,small interfering RNAs(siRNAs),transfer RNAs(tRNAs),and ribosomal RNAs(rRNAs)(18,24–38).2.Design miRNA-specific primers to contain only the“coresequence”since our cloning method uses two degeneratenucleotides(VN)at the3 end to make small RNA cDNAs(srcDNAs)(see let-7a,Table19.1).3.For qPCR analysis,two miRNAs and a piRNA were quan-titated using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix(41).Cyclethreshold(Ct)is the cycle number at which thefluorescencesignal reaches the threshold level above the background.ACt value for each miRNA tested was automatically calculatedby setting the threshold level to be0.1–0.3with auto base-line.All Ct values depend on the abundance of target miR-NAs.For example,average Ct values for let-7isoforms rangefrom17to20when25ng of each srcDNA sample from themultiple tissues was used(see(41).Quantitative Analysis of Small RNAs3034.This method amplifies over a broad dynamic range up to10orders of magnitude and has excellent sensitivity capable ofdetecting as little as0.001ng of the srcDNA in qPCR assays.5.For qPCR,each small RNA-specific primer should be testedalong with a known control primer(e.g.,let-7a)for PCRefficiency.Good efficiencies range from90%to110%calcu-lated from slopes between–3.1and–3.6.6.On an agarose gel,mature miRNAs and precursor miRNAs(pre-miRNAs)can be differentiated by their size.PCR prod-ucts containing miRNAs will be∼120bp long in size whileproducts containing pre-miRNAs will be∼170bp long.However,our PCR method preferentially amplifies maturemiRNAs(see Results and Discussion in(41)).We testedour PCR method to quantify over100miRNAs,but neverdetected pre-miRNAs(18,29–31,38). AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank Jonathan Cho for reading andediting the text.This work was supported by grants from theNational Institute of Health(HD048855and HD050281)toW.Y.References1.Ambros,V.(2004)The functions of animalmicroRNAs.Nature,431,350–355.2.Bartel,D.P.(2004)MicroRNAs:genomics,biogenesis,mechanism,and function.Cell, 116,281–297.3.Chang,T.C.and Mendell,J.T.(2007)Theroles of microRNAs in vertebrate physiol-ogy and human disease.Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet.4.Kim,V.N.(2005)MicroRNA biogenesis:coordinated cropping and dicing.Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol,6,376–385.5.Kim,V.N.(2006)Small RNAs just gotbigger:Piwi-interacting RNAs(piRNAs) in mammalian testes.Genes Dev,20, 1993–1997.6.Kotaja,N.,Bhattacharyya,S.N.,Jaskiewicz,L.,Kimmins,S.,Parvinen,M.,Filipowicz, W.,and Sassone-Corsi,P.(2006)The chro-matoid body of male germ cells:similarity with processing bodies and presence of Dicer and microRNA pathway components.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A,103,2647–2652.7.Aravin,A.A.,Lagos-Quintana,M.,Yalcin,A.,Zavolan,M.,Marks,D.,Snyder,B.,Gaaster-land,T.,Meyer,J.,and Tuschl,T.(2003) The small RNA profile during Drosophilamelanogaster development.Dev Cell,5, 337–350.8.Lee,R.C.and Ambros,V.(2001)An exten-sive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis ele-gans.Science,294,862–864.u,N.C.,Lim,L.P.,Weinstein, E.G.,and Bartel,D.P.(2001)An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans.Science,294, 858–862.gos-Quintana,M.,Rauhut,R.,Lendeckel,W.,and Tuschl,T.(2001)Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs.Science,294,853–858.u,N.C.,Seto,A.G.,Kim,J.,Kuramochi-Miyagawa,S.,Nakano,T.,Bartel,D.P.,and Kingston,R.E.(2006)Characterization of the piRNA complex from rat testes.Science, 313,363–367.12.Grivna,S.T.,Beyret,E.,Wang,Z.,and Lin,H.(2006)A novel class of small RNAs inmouse spermatogenic cells.Genes Dev,20, 1709–1714.13.Girard, A.,Sachidanandam,R.,Hannon,G.J.,and Carmell,M.A.(2006)A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins.Nature,442,199–202.304Ro and Yan14.Aravin,A.,Gaidatzis,D.,Pfeffer,S.,Lagos-Quintana,M.,Landgraf,P.,Iovino,N., Morris,P.,Brownstein,M.J.,Kuramochi-Miyagawa,S.,Nakano,T.,Chien,M.,Russo, J.J.,Ju,J.,Sheridan,R.,Sander,C.,Zavolan, M.,and Tuschl,T.(2006)A novel class of small RNAs bind to MILI protein in mouse testes.Nature,442,203–207.15.Watanabe,T.,Takeda, A.,Tsukiyama,T.,Mise,K.,Okuno,T.,Sasaki,H.,Minami, N.,and Imai,H.(2006)Identification and characterization of two novel classes of small RNAs in the mouse germline: retrotransposon-derived siRNAs in oocytes and germline small RNAs in testes.Genes Dev,20,1732–1743.16.Vagin,V.V.,Sigova,A.,Li,C.,Seitz,H.,Gvozdev,V.,and Zamore,P.D.(2006)A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline.Science, 313,320–324.17.Saito,K.,Nishida,K.M.,Mori,T.,Kawa-mura,Y.,Miyoshi,K.,Nagami,T.,Siomi,H.,and Siomi,M.C.(2006)Specific asso-ciation of Piwi with rasiRNAs derived from retrotransposon and heterochromatic regions in the Drosophila genome.Genes Dev,20, 2214–2222.18.Ro,S.,Song,R.,Park, C.,Zheng,H.,Sanders,K.M.,and Yan,W.(2007)Cloning and expression profiling of small RNAs expressed in the mouse ovary.RNA,13, 2366–2380.19.Ruby,J.G.,Jan,C.,Player,C.,Axtell,M.J.,Lee,W.,Nusbaum,C.,Ge,H.,and Bartel,D.P.(2006)Large-scale sequencing reveals21U-RNAs and additional microRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in C.elegans.Cell,127, 1193–1207.20.Terns,M.P.and Terns,R.M.(2002)Small nucleolar RNAs:versatile trans-acting molecules of ancient evolutionary origin.Gene Expr,10,17–39.21.Ouellet,D.L.,Perron,M.P.,Gobeil,L.A.,Plante,P.,and Provost,P.(2006)MicroR-NAs in gene regulation:when the smallest governs it all.J Biomed Biotechnol,2006, 69616.22.Maatouk,D.and Harfe,B.(2006)MicroR-NAs in development.ScientificWorldJournal, 6,1828–1840.23.Kim,V.N.and Nam,J.W.(2006)Genomics of microRNA.Trends Genet,22, 165–173.24.Bohnsack,M.T.,Kos,M.,and Tollervey,D.(2008)Quantitative analysis of snoRNAassociation with pre-ribosomes and release of snR30by Rok1helicase.EMBO Rep,9, 1230–1236.25.Hertel,J.,de Jong, D.,Marz,M.,Rose,D.,Tafer,H.,Tanzer, A.,Schierwater,B.,and Stadler,P.F.(2009)Non-codingRNA annotation of the genome of Tri-choplax adhaerens.Nucleic Acids Res,37, 1602–1615.26.Kim,M.,Patel,B.,Schroeder,K.E.,Raza,A.,and Dejong,J.(2008)Organization andtranscriptional output of a novel mRNA-like piRNA gene(mpiR)located on mouse chro-mosome10.RNA,14,1005–1011.27.Mishima,T.,Takizawa,T.,Luo,S.S.,Ishibashi,O.,Kawahigashi,Y.,Mizuguchi, Y.,Ishikawa,T.,Mori,M.,Kanda,T., and Goto,T.(2008)MicroRNA(miRNA) cloning analysis reveals sex differences in miRNA expression profiles between adult mouse testis and ovary.Reproduction,136, 811–822.28.Papaioannou,M.D.,Pitetti,J.L.,Ro,S.,Park, C.,Aubry, F.,Schaad,O.,Vejnar,C.E.,Kuhne, F.,Descombes,P.,Zdob-nov, E.M.,McManus,M.T.,Guillou, F., Harfe,B.D.,Yan,W.,Jegou,B.,and Nef, S.(2009)Sertoli cell Dicer is essential for spermatogenesis in mice.Dev Biol,326, 250–259.29.Ro,S.,Park,C.,Sanders,K.M.,McCarrey,J.R.,and Yan,W.(2007)Cloning and expres-sion profiling of testis-expressed microRNAs.Dev Biol,311,592–602.30.Ro,S.,Park,C.,Song,R.,Nguyen,D.,Jin,J.,Sanders,K.M.,McCarrey,J.R.,and Yan, W.(2007)Cloning and expression profiling of testis-expressed piRNA-like RNAs.RNA, 13,1693–1702.31.Ro,S.,Park,C.,Young,D.,Sanders,K.M.,and Yan,W.(2007)Tissue-dependent paired expression of miRNAs.Nucleic Acids Res, 35,5944–5953.32.Siebolts,U.,Varnholt,H.,Drebber,U.,Dienes,H.P.,Wickenhauser,C.,and Oden-thal,M.(2009)Tissues from routine pathol-ogy archives are suitable for microRNA anal-yses by quantitative PCR.J Clin Pathol,62, 84–88.33.Smits,G.,Mungall,A.J.,Griffiths-Jones,S.,Smith,P.,Beury,D.,Matthews,L.,Rogers, J.,Pask, A.J.,Shaw,G.,VandeBerg,J.L., McCarrey,J.R.,Renfree,M.B.,Reik,W.,and Dunham,I.(2008)Conservation of the H19 noncoding RNA and H19-IGF2imprint-ing mechanism in therians.Nat Genet,40, 971–976.34.Song,R.,Ro,S.,Michaels,J.D.,Park,C.,McCarrey,J.R.,and Yan,W.(2009)Many X-linked microRNAs escape meiotic sex chromosome inactivation.Nat Genet,41, 488–493.Quantitative Analysis of Small RNAs30535.Wang,W.X.,Wilfred,B.R.,Baldwin,D.A.,Isett,R.B.,Ren,N.,Stromberg, A.,and Nelson,P.T.(2008)Focus on RNA iso-lation:obtaining RNA for microRNA (miRNA)expression profiling analyses of neural tissue.Biochim Biophys Acta,1779, 749–757.36.Wu,F.,Zikusoka,M.,Trindade,A.,Das-sopoulos,T.,Harris,M.L.,Bayless,T.M., Brant,S.R.,Chakravarti,S.,and Kwon, J.H.(2008)MicroRNAs are differen-tially expressed in ulcerative colitis and alter expression of macrophage inflam-matory peptide-2alpha.Gastroenterology, 135(1624–1635),e24.37.Wu,H.,Neilson,J.R.,Kumar,P.,Manocha,M.,Shankar,P.,Sharp,P.A.,and Manjunath, N.(2007)miRNA profiling of naive,effec-tor and memory CD8T cells.PLoS ONE,2, e1020.38.Yan,W.,Morozumi,K.,Zhang,J.,Ro,S.,Park, C.,and Yanagimachi,R.(2008) Birth of mice after intracytoplasmic injec-tion of single purified sperm nuclei and detection of messenger RNAs and microR-NAs in the sperm nuclei.Biol Reprod,78, 896–902.39.Guryev,V.and Cuppen,E.(2009)Next-generation sequencing approaches in genetic rodent model systems to study func-tional effects of human genetic variation.FEBS Lett.40.Li,W.and Ruan,K.(2009)MicroRNAdetection by microarray.Anal Bioanal Chem.41.Ro,S.,Park,C.,Jin,JL.,Sanders,KM.,andYan,W.(2006)A PCR-based method for detection and quantification of small RNAs.Biochem and Biophys Res Commun,351, 756–763.。

2.4. Chemical and microbial analyses Analysis of DM and CP concentration in the experimental diets, excreta and probiotic products was done according to AOAC (1990 methods (930.05 and 976.05, respectively. The GE was measured by using the bomb calorimeter (model 1261, Parr Instrument Co., Moline, IL, and chromium concentration was determined with an automated spectrophotometer (Jasco V-650, Jasco Corp., Tokyo, Japan according to the procedure of Fenton and Fenton (1979. The microbiological assay of faecal samples (d 14 and 28 and intestinal digesta (d 28 was conducted by culturing in different media for the determination of total anaerobic bacteria (Tryptic soy agar, Bifidobacterium spp. (MRS agar, Lactobacillus spp. (MRS agar+0.02% NaN3+0.05% L-cystine hydrochloride monohydrate, Clostridium spp. (TSC agar and coliforms (violet red bile agar. The microbiological assay of probiotic products was also carried out by culturing technique. The L. acidophilus was enumerated using MRS agar+0.02%NaN3+0.05% L-cystine hydrochloride monohydrate, B. Subtilis by using plate count agar, S. cerevisiae and A. oryzae by potato dextrose agar. The anaerobic conditions during the assay of anaerobic were created by using gas pack anaerobic system (BBL, No. 260678; Difco, Detroit, MI. The tryptic soy agar (No. 236950, MRS agar (No. 288130, violet red bile agar (No. 216695, plate count agar (No. 247940, and potato dextrose agar (No. 213400 used were purchased from Difco Laboratories (Detroit,MI, and TSC agar(CM0589 was purchased from Oxoid (Hampshire, UK. The pH of probiotic products was determined by pH meter (Basic pH Meter PB-11, Sartorius, Germany.2.5. Small intestine morphology Three cross-sections for each intestinal sample were prepared after staining with azure A and eosin using standard paraffin embedding procedures. A total of 10 intact, welloriented crypt-villus units were selected in triplicate for each intestinal cross-section as described previously (Jin et al., 2008. Villus height was measured from the tip of the villi to the villus crypt junction, and crypt depth was defined as the depth of the invagination between adjacent villi. All morphological measurements (villus height and crypt depth were made in 10-μm increments by using animage proce ssing and analysis system (Optimus software version 6.5, Media Cybergenetics, North Reading, MA.2.6. Statistical analysesAll the data obtained in the current study were analyzed in accordance with a rand omized complete block design using the GLM procedure of SAS (SAS Inst. Inc., C ary, NC. In Exp. 1, one-way analysis of variance test was used and when signific ant differences (Pb0.05 were determined among treatment means, they were separ ated by using Duncan's multiple range tests. In Exp. 2, the data were analyzed as a 2×2 factorial arrangement of treatments in randomized complete block design. T he main effects of probiotic products (LF or SF, antibiotic (colistin or lincomycin, a nd their interaction were determined by the Mixed procedures of SAS. However, as the interaction (probiotic x antibiotic was not statistically significant (Pb0.05, it wa s removed from the final model. The pen was the experimental unit for all analysis in both experiments. The bacterial concentrations were transformed (log before st atistical analysis.3.1. Experiment 13.1.1. Growth performance and apparent total tract digestibilityDietary treatments had no effect on the performance of pigs during phase I (Table 3. However, during phase II and the overall experimental period, improved (Pb0.05 ADG, ADFI and G:F were observed in pigs fed PC, LF and SF dietswhen compared with pigs fed NC diet. Moreover, pigs fed PC and SF diets had hi gher (Pb0.05 ADG and better G:F than pigs fed LF diet during phase II and the o verall experimentalperiod. The dietary treatments had no influence on the ATTDof DM and GE; however, pigs fed PC and SF diets had greater ATTD of CP whe n compared with pigs fed NC and LF diets (Table 4.3.1.2. Bacterial population in faecesDietary treatments had no effect on the faecal total anaerobes and Bifidobacterium spp. population at d 14 and 28, and Lactobacillus spp. at d 14 (Table 5. However, pigs fed PC (d 14 and 28 and SF (d 28 diets had less (Pb0.05 faecal Clostridium spp. and coliforms than pigs fed NC diet.Moreover, pigs fed SF diet had greater (Pb0.05 faecal Lactobacillus spp. populatio n (d 28 than pigs fed NC, PC and LF diets.3.2. Experiment 23.2.1. Growth performance and apparent total tract digestibilityDuring phase I, pigs fed SF diet consumed more feed than pigs fed LF diet, wher eas the ADG and ADFI were similar between pigs fed LF and SF diets (Table 6. During phase II and the overall experimental period, pigs fed SF diet showed better ADG(Pb0.01, ADFI (Pb0.01 and G:F (Pb0.05 thanpigs fed LF diet. Howev er, different antibiotics had no effect on the performance of pigs. Pigs fed SF diet had greater ATTD of DM and CP during phases I and II (Pb0.01 and 0.001, respe ctively when compared with pigs fed LF diet (Table 7.However, different antibiotics had no effect on the ATTD of DM, CP and GE.3.2.2. Bacterial population in intestinePigs fed SF diet had greater (Pb0.05 Lactobacillus spp. And less Clostridium spp. (Pb0.01 and coliform (Pb0.05 population in the ileum than pigs fed LF diet (Table 8. Additionally,higher (Pb0.05 caecal Bifidobacterium spp. Population was observed in pigs fed SF diet. Antibiotics had no effect on the ileal microbial population; however, pigs fed colistin diet had less number of Bifidobacterium spp. (Pb0.05 and coliforms (Pb0.01 inthe cecum, whereas, feeding of lincomycin diet resulted in reduced (Pb0.05 caecal Clostridium spp.population.3.2.3. Small intestinal morphologyThe different probiotic products and antibiotics had no influence on the morphology of different segments of the small intestine, except for the greater (Pb0.05 villus height:crypt depth at the jejunum and ileum noticed in pigs fed lincomycin diet (Table 9.4.DiscussionPrevious studies on probiotics lack information on the method of production used, however, the preparation of probiotics by LF method is fairly common (Patel et al., 2004. The probiotic products used in the present study differedfrom the previous reports in that harvested probiotic microbes were added directly to the diets. In this study, the microbial biomass grown on the CB was directly sprayed onthe carrier (corn and soybean meal to obtain LF probiotic product. In case of the SF probiotic product, corn and soybean meal was used as a substrate during fermentation and as a carrier of probiotic microbes. We have reported previously that multi-microbe probiotic product prepared by SF method was better than the probiotic product prepared by submerged liquid fermentation in improving performance, nutrient retention and reducing harmful intestinal bacteria in broilers (Shim et al., 2010. In the current study, LF and SF method was used and corn–soybean meal was used as a substrate forthe growth of potential probiotic microbes under optimum conditions.2.4 化学和微生物分析在试验日粮干物质和粗蛋白含量的分析中,排泄物和益生菌产品是根据AOAC(1990方法(分别为930.05和976.05 分析。