Early Atherosclerosis Assessed by Novel Indices 263

Tohoku J. Exp. Med., 2017, 241, 263-270263

Received January 12, 2017; revised and accepted March 14, 2017. Published online April 1, 2017; doi: 10.1620/tjem.241.263.*These authors contributed equally to this work.

Correspondence: Zhaofang Yin, M.D., Department of Cardiology, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, No.639 Zhizaoju Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai 200011, China.

e-mail: hhxxapple @https://www.doczj.com/doc/f812511337.html,

Non-Invasive Assessment of Early Atherosclerosis Based on New

Arterial Stiffness Indices Measured with an Upper-Arm Oscillometric Device

Yaping Zhang,1,* Ping Yin,1,* Zuojun Xu,1 Yushui Xie,1 Changqian Wang,1 Yuqi Fan,1 Fuyou Liang 2 and Zhaofang Yin 1

1

Department of Cardiology, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China 2

Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Chiba University International Cooperative Research Center, School of Naval Architecture, Ocean and Civil Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

The clinical significance of detecting early atherosclerosis is now widely recognized. Measurement methods available at present are usually not suitable for use in primary care where rapid screening for a large population is needed. The Arterial Velocity-pulse Index (AVI) and Arterial Pressure-volume Index (API) are new noninvasive arterial stiffness indices that can be rapidly measured using an oscillometric device. The purpose of this study was to determine whether high AVI and API values are predictive of early atherosclerosis prior to the onset of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD). A total of 183 patients were enrolled and allocated to the CAD group (n = 109), early atherosclerosis (AS) group (n = 34) or an apparently healthy (non-AS) group (n = 40) based on the results of angiographic examinations. Measurements for arterial blood pressure, AVI, API and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) were collected. Statistical analyses revealed that AVIs were significantly lower in the non-AS group than in the AS group and the CAD group. The inter-group differences in API were not statistically significant among the 3 patient groups. As a reference, baPWV was found to be statistically higher in the CAD group than in the non-AS group, whereas there was no significant difference between the CAD group and the AS group, or between the AS group and the non-AS group. The AVI and API were both significantly correlated with baPWV. This study demonstrated that AVI was more sensitive than baPWV and API in indicating early atherosclerosis, although elevated AVI and baPWV were both predictive of CAD.

Keywords: arterial stiffness index; atherosclerosis; coronary artery disease; noninvasive measurement; oscillometric method

Tohoku J. Exp. Med., 2017 April, 241(4), 263-270. ? 2017 Tohoku University Medical Press

Introduction

Over the past decade, ischemic heart disease has held the first place in the list of top 30 causes for years of life lost (YLLs) worldwide (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016). In recent years, increasing emphasis has been placed on detecting early arteriosclerosis because this has been proved to be a predictor for future cardiovascular events (Simon et al. 2006). For the manage-ment of patients suspected of having coronary artery dis-ease (CAD), the techniques of coronary angiography, intra-vascular ultrasound (IVUS), or optical coherence tomography (OCT) remain as “the gold standard” for diag-nosis. However, their application in primary prevention of CAD is limited due to their invasive nature and high cost.

It has been well documented that increased arterial stiffness is an independent predictor of adverse cardiovas -cular outcomes, both in the general population (Mattace-Raso et al. 2006; Willum-Hansen et al. 2006) and in patients with cardiovascular disorders (Blacher et al. 1999; Guerin et al. 2001; Laurent et al. 2001). In the last decade, pulse wave velocity (PWV) has been a widely accepted noninvasive measurement of arterial stiffness (Laurent et al. 2006) and its value in predicting negative cardiovascular events (including both CAD and other cardiovascular dis-eases) has been extensively demonstrated (Sugawara et al. 2005; Tomiyama et al. 2005; Meguro et al. 2009; Nakamura et al. 2010; Munakata et al. 2012; Vlachopoulos et al. 2012). Nonetheless, the use of PWV measurement remains to be unsuitable for the patient screening or risk stratifica -

Y. Zhang et al. 264

tion in routine clinical practice due to the relatively high cost, requirement of expertise operation and long measure-ment time. In view of the prevalence of asymptomatic cor-onary atherosclerosis in the general population, there is an urgent need to develop methods capable of detecting the presence of early atherosclerosis in a rapid and noninvasive way.

In this context, new methods that permit rapid assess-ment of arterial stiffness while incurring low cost have been investigated in recent years (Sato et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006; Baulmann et al. 2008). Arterial Velocity-pulse Index (A VI) and Arterial Pressure-volume Index (API) are new arterial stiffness indices measured by a cuff-based oscillometric device (PASESA A VE-1500; Shisei Datum, Tokyo, Japan). The A VI mainly reflects the stiffness of central arteries, while API mainly reflects the stiffness of the brachial artery. These indices were derived by means of quantitatively ana-lyzing the specific characteristics of cuff oscillation waves detected at different cuff-operating pressures (Komine et al. 2012; Liang et al. 2013). So far, studies on A VI and API have been performed mainly in Japan. For example, a pop-ulation-based study (468 outpatients, 85 hospitalized patients) performed at the University of Kurume demon-strated that A VI correlated strongly with the number of car-diovascular risk factors (r = 0.62, P < 0.01) in subjects not taking oral medications. Another study from Saitama Medical University (Akiyama et al. 2010) showed that both A VI and API were significantly related to the development of ischemic cardiac disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Tazawa et al. (2016)found that increased A VI was associ-ated with CAD and reduced exercise capacity in patients with cardiac diseases. A more recent study comprising of 252 participants (149 men and 103 women) revealed that API was independently associated with the Framingham risk score (Sasaki-Nakashima et al. 2017) .

Despite the extensive studies carried out previously, it remains unclear whether A VI and API could predict the risk of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients without significant obstructive lumen changes. Therefore, the main purpose of the present study was to investigate the correlation of A VI and API with the existence of atherosclerosis. In addition, the classical arterial stiffness index baPWV (brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity) was measured as a reference variable.

Methods

Patients

This was a cross-sectional study performed on patients who underwent coronary angiography for the assessment of symptoms indicative of CAD during March, 2016 to October, 2016. The study has been approved by the local institutional review board (Medical Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University, School of Medicine. Approval num-ber: Hu jiuyuan lunshen [2016] No. 21) and written informed con-sents were received from all patients. For each patient, the medical records were reviewed to determine the coronary artery status and to collect information on patient profiles, medical history, medication use, and laboratory data. All the enrolled patients were allocated to 3 groups: the CAD group, the early atherosclerosis (AS) group, and the apparently healthy (non-AS) group. Herein, CAD was defined as the presence of a ≥ 50% stenosis in at least 1 major coronary artery deter-mined by coronary angiography or coronary computed tomography examination. Early atherosclerosis was defined as the presence of detectable coronary atherosclerotic plaques but without significant arterial stenosis that would meet the diagnosis criteria of CAD. Similarly, non-AS was defined as the absence of detectable coronary atherosclerotic plaques.

Measurements of arterial stiffness indices

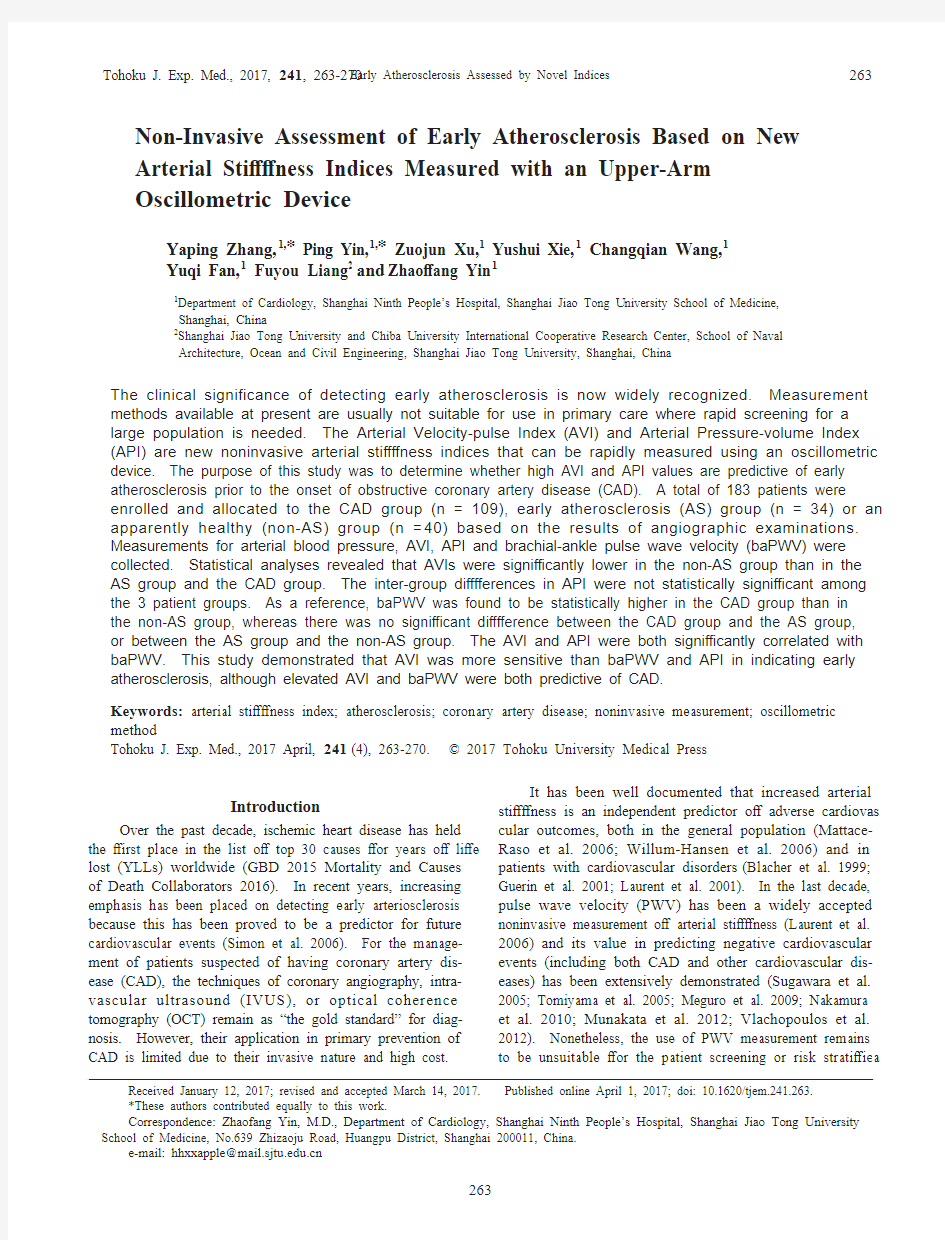

To examine the inter-observer variability which might affect our data during the measurements, we performed a preliminary experi-ment in which 2 observers separately measured the A VI and API in 10 participants. Then a Reliability Analysis was performed and the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for A VI and API were found to be 0.875 (95% CI: 0.578-0.967, type: single absolute agreement) and 0.846 (95% CI: 0.610-0.948, type: single absolute agreement). The A VI and API were measured together with the brachial arterial blood pressures using an oscillometric blood pressure device (PASESA A VE-1500, Shisei Datum, Tokyo, Japan) before coronary angiography. A pattern diagram of the pulsewave for A VI is shown in Fig. 1(Sueta et al. 2015). The increased A VI indicates the enhance-ment of reflected waves. The principles and formulas for A VI and API were previously reported by Sueta et al. (2015). The patients were in a supine position during the measurement. The measurement was performed at least twice for each patient at an interval of 2-5 minutes, with the mean of multiple measurements being recorded.

The baPWV was measured using BP-203RPEIII (Omron, Japan) 5 to 10 minutes after the measurement of the A VI and API. The mean value of the left and right baPWVs was calculated and used in the statistical analysis.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory data were obtained from the medical records of all the patients, which included the level of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), serum creatinine(SCr), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol(LDL-C) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Statistical analysis

All statistical data are presented for each patient cohort in the form of either mean ± standard deviation or percentage. Comparison of variables among the 3 patient groups was carried out using a one-way ANOV A (a post-hoc test of Tukey HSD or Dunnett-T3 was selected in the light of the variance homogeneity or non-homogene-ity). The Chi-square test was adopted when percentage values were compared. The correlations among A VI, API, baPWV, and other vari-ables were quantified by correlation coefficients. We used the Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis method depending on the results of the normality test for variables. For variables exhibiting an extremely large inter-patient variation (i.e., BNP), log transformation was applied prior to correlation analysis to obtain a normal data distribu-tion. Moreover, stepwise regression analysis was conducted to deter-mine the predictive factors of arterial stiffness indices. All probability values were calculated from a two-tailed test, with statistical signifi-cance being inferred at P < 0.05.

Early Atherosclerosis Assessed by Novel Indices

265

Results

Baseline characteristics of all subjects

A total of 183 patients were enrolled in this study, and their baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1: 109 patients in the CAD group, 34 patients in the AS group, and 40 patients in the non-AS group. The mean age of patients did not differ significantly among the three groups (68.0 ± 10.5 years vs. 63.8 ± 8.5 years vs. 65.8 ± 13.7 years, P = 0.127).

Differences of arterial stiffness indices among patient groups

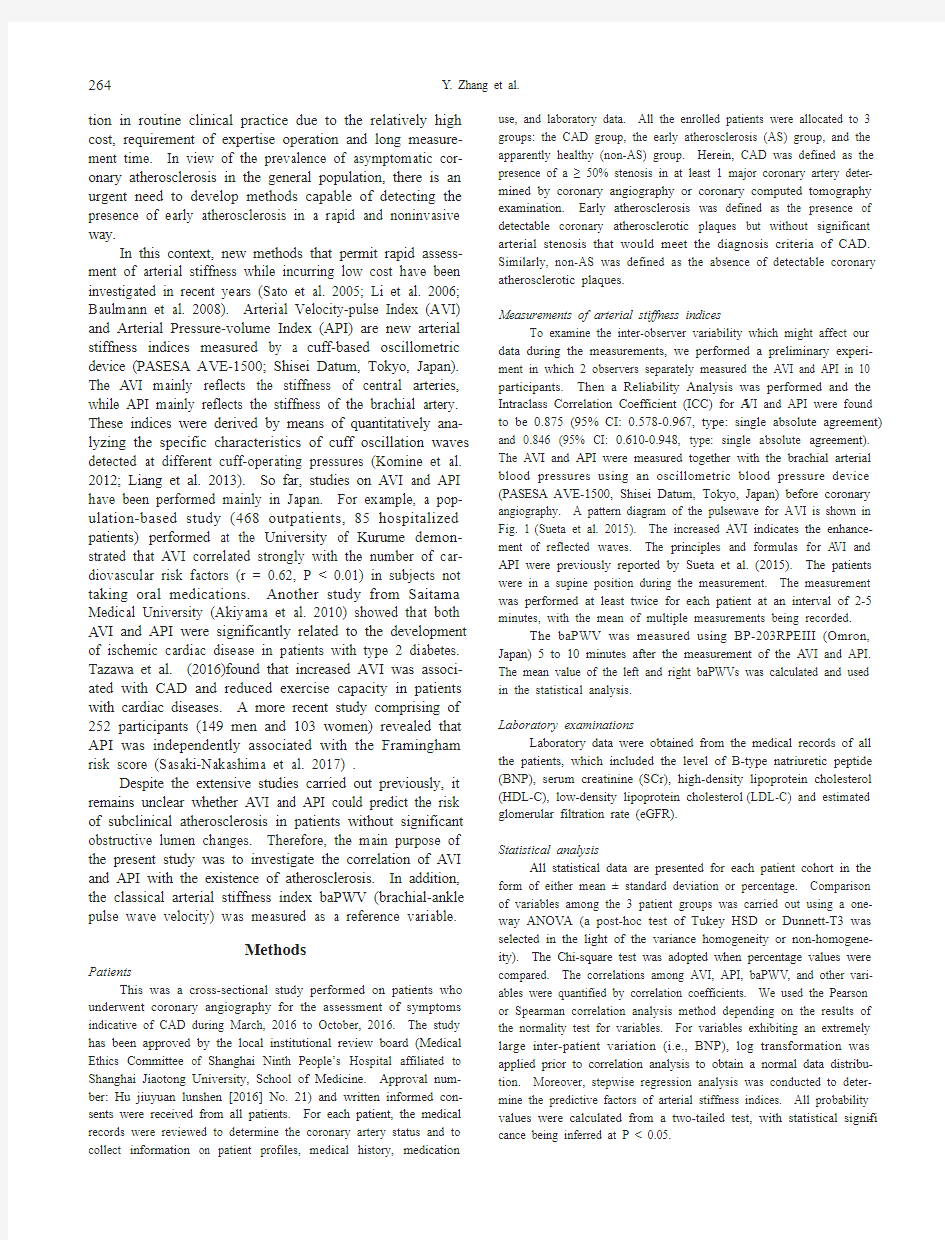

The results from ANOV A indicated that the A VI was significantly different among the 3 patient groups (P < 0.001). Results of multiple comparison showed that the mean values of A VI in the CAD group and the AS group were both significantly higher than that in the non-AS group (25.6 ± 6.7 vs. 19.6 ± 4.4, P < 0.001, 27.0 ± 8.4 vs. 19.6 ± 4.4, P < 0.001, respectively) (shown in Fig. 2A). However, no statistically significant difference in A VI was observed between the CAD group and the AS group (25.6 ±

6.7 vs. 2

7.0 ±

8.4, P = 0.750).

The results from ANOV A for baPWV revealed signifi -cant differences among the 3 patient groups (P = 0.001). The mean baPWV in the CAD group was significantly higher than that in the non-AS group (16.9 ± 3.4 vs. 14.6 ± 2.8, P < 0.001) (shown in Fig. 2B). However, no significant difference between the CAD and AS groups (16.9 ± 3.4 vs. 16.1 ± 2.9, P = 0.426) or between the AS and non-AS groups (16.1 ± 2.9 vs. 14.6 ± 2.8, P = 0.113) was found.

When the measured API values were compared among the 3 patient groups, no statistically significant difference was identified (28.0 ± 6.2 vs. 27.1 ± 7.2 vs. 25.4 ± 5.1, P = 0.071) (shown in Fig. 2C).

With regard to the interrelationships among the arterial stiffness indices, A VI and API were both correlated with baPWV (see Fig. 3).

Results of correlation analysis and regression analysis

Correlation analyses were performed with the data obtained from all the patients. Table 2 shows the calculated correlation coefficients between the arterial stiffness indices (i.e., A

VI, API, baPWV) and other variables (Pearson’s cor-

Fig. 1. Pulsewave pattern diagrams of A VI. The diagrams were adapted from Sueta et al. (2015) Int. J. Cardiol, 189, 244-246 with permission of Elsevier. Pulse-wave (A) and differentiated waveform between pulsewave and time (B) in a young person with normal-vascular compli -ance and an elderly person with low-vascular compliance, respectively. P1 indicates an incident wave while P2 indi-cates a reflected wave. Vf: the first peak of differentiated waveform between pulse wave and time which is not

influenced by the reflected wave, Vr: the bottom of the trough of differentiated waveform between pulse wave and time which mainly reflect the steepness of the pressure decline after the second peak. Therefore, the ratio |Vr|/|Vf| indicates the tendency toward an increase in aortic stiffness.

Y . Zhang et al.

266

relation analysis was performed for the log transferred BNP, while Spearman’s correlation analysis was used for other variables). The values of A VI, API, and baPWV all corre-lated positively with age, brachial systolic blood pressure (SBP), and pulse pressure (PP). Strong correlations were observed especially between API and PP, and between API and SBP. The A VI and baPWV were inversely related to eGFR.

Stepwise regression analysis was carried out to iden-tify the associated factors of A VI and baPWV which have been found to differ significantly between the CAD group and the non-AS group. The results showed that BNP was the primary independent factor of A VI, followed by baPWV

and pulse pressure, and that A VI was the primary indepen-dent factor of baPWV , followed by pulse pressure and eGFR (see Table 3).

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that the A VI is associated with the number of cardiovascular risk factors, the Framingham risk score (Sasaki-Nakashima et al. 2017) and CAD (Tazawa et al. 2016). The predictive value of A VI in ischemic cardiac disease has also been confirmed in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. However, the rela-tionship between A VI and early atherosclerosis remains to be determined, which is a key issue when discussing the

CAD group (n=109)

AS group (n=34) non-CAS group (n=40)

P value

68.0±10.5 63.8±8.5 65.8±13.7 0.127 64.2/35.8 41.2/58.8 37.5/62.5 0.004** 25.5±3.2 25.2±3.3 23.5±3.5 0.007** 127.9±16.9 127.3±21.5 120.0±16.4 0.054 55.4±14.7 56.4±18.4 53.0±15.2 0.613

91.0±12.7 89.7±11.8 84.7±9.3 0.018* 73.4±28.0 80.4±22.3 72.3±23.1 0.373 1.8±0.5 1.7±0.5 1.8±0.4 0.326 4.2±1.1 4.5±0.9 4.0±0.9 0.095 1.8±1.1 1.9±1.0 1.4±1.1 0.147 2.6±0.9 2.9±0.7 2.5±0.8 0.175 0.9±0.3 1.0±0.3 1.1±0.3 0.062 74.3 67.6

52.5 0.04* 32.1 26.5 25.0 0.001** 22.0 14.7 17.5 0.598 Demographic data Age (years) Sex (m/f %) BMI (kg/m2) SBP (mmHg) PP (mmHg) MAP (mmHg) Laboratory data

eGFR (ml/min/1.73m 2) BNP (pg/ml)? CHOL (mmol/l) TG (mmol/l) LDL-C (mmol/l) HDL-C (mmol/l) Comorbidity Hypertension (%) Diabetes (%)

Stroke history (%) Medication

Antihypertensive drugs (%)

75.2

58.8

37.5 <0.001***

ACEI/ARB (%) 61.5

47.1 32.5 0.006**

Ca antagonist (%) 33.9 23.5 15.0 0.060 Diuretics (%) 13.8

17.6 10.0 0.633 Beta blockers (%) 56.9 41.1 45.0 0.184 17.4 5.9 0.0

0.001**

Anti-diabetic drugs (%) Lipid-lowering drugs (%)

96.3

85.3

17.5 <0.001***

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of all patients.

SBP, brachial systolic blood pressure; DBP, branchial diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean blood pressure; PP, brachial pulse pressure; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CHOL, cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Data are presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation), median (interquartile range), or percentage.

The antihypertensive drugs contain all of ACEI / ARB, Ca antagonists, diuretics, and beta blockers. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ?log transformed.

Early Atherosclerosis Assessed by Novel Indices

267

value of AVI in preventive medicine. Our results for

patients with CAD were basically consistent with those reported in previous studies. A new finding was that A VI values were significantly higher not only in the CAD group but also in the AS group in comparison with those in the non-AS group. This implies that increased A VI may be indicative of early atherosclerosis or CAD. It was interest-ing to find that baPWV , as a standard measure of arterial stiffness, could not predict the presence of early atheroscle -rosis, although its predictive value in CAD was confirmed in our study.

With regard to API, there have been some reports of the association of API with cardiovascular disease or Framingham risk score. In our study, however, no statisti-cally significant difference was observed among the 3 patient groups. A potential explanation for this discrepancy is that the small patient sample of our study may have increased the uncertainty of the statistical analysis of the relationship between API and early atherosclerosis. Another explanation is that the patient cohort investigated and the criteria of patient grouping differed between our study and other studies. Our study focused on hospitalized patients with symptoms indicative of AS, while previous studies involved outpatients regardless of the presence or absence of indications of AS. Recalling the mechanisms underlying the measurement of A

VI and API, these 2 indi-

Fig. 2. Differences in A VI, baPWV , and API among CAD, AS, and non-AS groups. Compared were the values of A VI (A), baPWV (B), and API (C) among the CAD group, the AS group, and the non-AS

group. The A VI values were significantly lower in the non-AS group than in the AS group and the CAD group. BaP -WV values were higher in the CAD group than the non-AS group, whereas there was no significant difference between the CAD group and the AS group, or between the AS group and the non-AS group. The inter-group differences in API

values were not statistically significant among the three patient groups.

Fig. 3. Correlation between A VI or API and baPWV . A. Correlation between A VI and baPWV . B. Correlation between API and baPWV . The A VI and API were both significantly correlated with baPWV in a total of 183 patients.

Y . Zhang et al.

268

ces reflect the regional arterial stiffness of the central aorta and the local arterial stiffness of the peripheral artery, respectively. Central aortic stiffness is generally considered to be more valuable than peripheral arterial stiffness in pre -dicting primary coronary events (Boutouyrie et al. 2002; Mattace-Raso et al. 2006). In particular, API seemed more sensitive to the level of blood pressure which was indicated by the strong positive correlation between API and PP, and between API and SBP. For the patients enrolled in the pres-ent study, ACEI/ARB and/or calcium antagonists were rou-tinely prescribed to treat hypertension during hospitaliza-tion. Therefore, the decrease in API secondary to a decrease in blood pressure as a consequence of anti-hyper-tensive treatment may have compromised the analysis on the association between API and CAD.

Used as a reference index, our results showed that baPWV was similar to A VI in predicting the risk of CAD. However, baPWV failed to predict early atherosclerosis. A potential explanation for this phenomenon is that baPWV , by its measurement principle, reflects the regionally aver -aged stiffness of arteries located between the brachial and ankle arteries, which compromises its sensitivity in captur-ing the changes in central arterial stiffness (Vlachopoulos et al. 2015).

Any noninvasively determined arterial stiffness index would be potentially influenced by multiple bio-factors due to the high nonlinearity of systemic hemodynamics (Liang et al. 2013). Correlation analysis and stepwise regression analysis revealed that A VI was positively related to age, PP, SBP and BNP. Advanced age, increased PP and SBP are well documented risk factors for cardiovascular events (Darne et al. 1989; Tokitsu et al. 2015), while increased BNP level is a strong predictor of cardiac dysfunction (Goetze et al. 2003; McLean et al. 2003). In this sense, A VI may be an integrated embodiment of several indicators of cardiovascular disorders.

The study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, this is a single center observational study enrolling a relatively small population with symptoms indicative of AS, which may partly account for the discrepant findings for API. The prognostic value of A VI and API for cardiovascular diseases remains to be confirmed in a larger population with a long-term follow up. Secondly, most patients involved in our study took a variety of cardiovascular medications, such as anti-diabetic, lipid-lowering, and anti-hypertensive medica-tions. It is unclear how such medications would affect the biomechanical properties of the cardiovascular system and the readings of arterial stiffness measurement. To clarify the issue, well-devised longitudinal clinical trials would be required.

In summary, we have provided the first evidence of the predictive value of the new arterial stiffness index A VI for early atherosclerosis. Fully automatic and rapid measure-ment may enhance the practical value of adopting the indi-ces in primary care prevention to identify subjects at high risk of atherosclerosis through large population screening. However, further studies are awaited to extensively validate the clinical utility of the indices in larger patient cohorts.

r P value r P value r P value NS NS 0.151 0.041 NS NS 0.432 <0.001*** 0.711 <0.001 0.436 <0.001*** 0.428 <0.001*** 0.735 <0.001 0.465 <0.001*** 0.23142 0.003 ** NS NS NS NS BMI (kg/m2)

PP (mmHg)

SBP (mmHg)

BNP (pg/ml)?

eGFR (ml/min/1.73m 2

) ?0.2280.003 ** NS NS ?0.303 <0.001***

Independent variables

β t P value AVI 1

baPWV 0.721 4.824 <0.001 BNP ?

1.866 1.985 0.049 baPWV

2

AVI 0.172 5.211 <0.001 PP 0.039 2.576 0.011 eGFR

?0.020

?3.174

0.002

Table 2. Correlations among arterial stiffness indices (A VI, API and baPWV) and other

variables.

mean blood pressure; PP, brachial pulse pressure; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. **P <0.01, ***P<0.001. ?log transformed.

Table 3. Stepwise regression of A VI & baPWV and associated variables.1

Adjusted R-squared value = 0.339, P < 0.001; 2Adjusted R-squared value = 0.295, P < 0.001. ?log transformed.

Early Atherosclerosis Assessed by Novel Indices269

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81370438).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Akiyama, Y., Hisano, Y., Hayakawa, N., Shigeto, M., Masuzawa, M., Okabe, T. & Matsuda, M. (2010) Comparison among indices obtained from oscillometric blood pressure apparatus, flow mediated dilatation, intra-media thickness. Prog. Med., 30, 2003-2007 (in Japanese).

Baulmann, J., Schillings, U., Rickert, S., Uen, S., Dusing, R., Illyes, M., Cziraki, A., Nickering, G. & Mengden, T. (2008) A new oscillometric method for assessment of arterial stiffness: comparison with tonometric and piezo-electronic methods. J.

Hypertens., 26, 523-528.

Blacher, J., Guerin, A.P., Pannier, B., Marchais, S.J., Safar, M.E. & London, G.M. (1999) Impact of aortic stiffness on survival in end-stage renal disease. Circulation, 99, 2434-2439. Boutouyrie, P., Tropeano, A.I., Asmar, R., Gautier, I., Benetos, A., Lacolley, P. & Laurent, S. (2002) Aortic stiffness is an inde-pendent predictor of primary coronary events in hypertensive patients: a longitudinal study. Hypertension, 39, 10-15. Darne, B., Girerd, X., Safar, M., Cambien, F. & Guize, L. (1989) Pulsatile versus steady component of blood pressure: a cross-sectional analysis and a prospective analysis on cardiovascular mortality. Hypertension, 13, 392-400.

GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (2016) Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet, 388, 1459-1544.

Goetze, J.P., Christoffersen, C., Perko, M., Arendrup, H., Rehfeld, J.F., Kastrup, J. & Nielsen, L.B. (2003) Increased cardiac BNP expression associated with myocardial ischemia. F ASEB J., 17, 1105-1107.

Guerin, A.P., Blacher, J., Pannier, B., Marchais, S.J., Safar, M.E. & London, G.M. (2001) Impact of aortic stiffness attenuation on survival of patients in end-stage renal failure. Circulation, 103, 987-992.

Komine, H., Asai, Y., Yokoi, T. & Yoshizawa, M. (2012) Non-invasive assessment of arterial stiffness using oscillometric blood pressure measurement. Biomed. Eng. Online, 11, 6. Laurent, S., Boutouyrie, P., Asmar, R., Gautier, I., Laloux, B., Guize, L., Ducimetiere, P. & Benetos, A. (2001) Aortic stiff-ness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovas-cular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension, 37, 1236-1241.

Laurent, S., Cockcroft, J., V an Bortel, L., Boutouyrie, P., Giannattasio,

C., Hayoz,

D., Pannier, B., Vlachopoulos, C., Wilkinson, I. &

Struijker-Boudier, H. (2006) Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applica-tions. Eur. Heart J., 27, 2588-2605.

Li, Y., Wang, J.G., Dolan, E., Gao, P.J., Guo, H.F., Nawrot, T., Stanton, A.V., Zhu, D.L., O’Brien, E. & Staessen, J.A. (2006) Ambulatory arterial stiffness index derived from 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Hypertension, 47, 359-364.

Liang, F., Takagi, S., Himeno, R. & Liu, H. (2013) A computa-tional model of the cardiovascular system coupled with an upper-arm oscillometric cuff and its application to studying the suprasystolic cuff oscillation wave, concerning its value in assessing arterial stiffness. Comput. Methods Biomech.

Biomed. Engin., 16, 141-157.Mattace-Raso, F.U., van der Cammen, T.J., Hofman, A., van Popele, N.M., Bos, M.L., Schalekamp, M.A., Asmar, R., Reneman, R.S., Hoeks, A.P., Breteler, M.M. & Witteman, J.C.

(2006) Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation, 113, 657-663. McLean, A.S., Tang, B., Nalos, M., Huang, S.J. & Stewart, D.E.

(2003) Increased B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level is a strong predictor for cardiac dysfunction in intensive care unit patients. Anaesth. Intensive. Care, 31, 21-27.

Meguro, T., Nagatomo, Y., Nagae, A., Seki, C., Kondou, N., Shibata, M. & Oda, Y. (2009) Elevated arterial stiffness evalu-ated by brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity is deleterious for the prognosis of patients with heart failure. Circ. J., 73, 673-680.

Munakata, M., Konno, S., Miura, Y. & Yoshinaga, K. (2012) Prog-nostic significance of the brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in patients with essential hypertension: final results of the J-TOPP study. Hypertens. Res., 35, 839-842. Nakamura, M., Yamashita, T., Yajima, J., Oikawa, Y., Sagara, K., Koike, A., Kirigaya, H., Nagashima, K., Sawada, H. & Aizawa, T. (2010) Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity as a risk stratification index for the short-term prognosis of type 2 diabetic patients with coronary artery disease. Hypertens.

Res., 33, 1018-1024.

Sasaki-Nakashima, R., Kino, T., Chen, L., Doi, H., Minegishi, S., Abe, K., Sugano, T., Taguri, M. & Ishigami, T. (2017) Successful prediction of cardiovascular risk by new non-inva-sive vascular indexes using suprasystolic cuff oscillometric waveform analysis. J. Cardiol., 69, 30-37.

Sato, H., Hayashi, J., Harashima, K., Shimazu, H. & Kitamoto, K.

(2005) A population-based study of arterial stiffness index in relation to cardiovascular risk factors. J. Atheroscler. Throm., 12, 175-180.

Simon, A., Chironi, G. & Levenson, J. (2006) Performance of subclinical arterial disease detection as a screening test for coronary heart disease. Hypertension, 48, 392-396. Sueta, D., Yamamoto, E., Tanaka, T., Hirata, Y., Sakamoto, K., Tsujita, K., Kojima, S., Nishiyama, K., Kaikita, K., Hokimoto, S., Jinnouchi, H. & Ogawa, H. (2015) The accuracy of central blood pressure waveform by novel mathematical transforma-tion of non-invasive measurement. Int. J. Cardiol., 189, 244-246.

Sugawara, J., Hayashi, K., Yokoi, T., Cortez-Cooper, M.Y., DeVan,

A.E., Anton, M.A. & Tanaka, H. (2005) Brachial-ankle pulse

wave velocity: an index of central arterial stiffness? J. Hum.

Hypertens., 19, 401-406.

Tazawa, Y., Mori, N., Ogawa, Y., Ito, O. & Kohzuki, M. (2016) Arterial stiffness measured with the cuff oscillometric method is predictive of exercise capacity in patients with cardiac diseases. Tohoku J. Exp. Med., 239, 127-134.

Tokitsu, T., Yamamoto, E., Hirata, Y., Fujisue, K., Sueta, D., Sugamura, K., Sakamoto, K., Kaikita, K., Hokimoto, S., Sugiyama, S. & Ogawa, H. (2015) Clinical significance of pulse pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Int. J.

Cardiol., 190, 299-301.

Tomiyama, H., Koji, Y., Yambe, M., Shiina, K., Motobe, K., Yamada, J., Shido, N., Tanaka, N., Chikamori, T. & Yamashina, A. (2005) Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity is a simple and independent predictor of prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circ. J., 69, 815-822. Vlachopoulos, C., Aznaouridis, K., Terentes-Printzios, D., Ioakeimidis, N. & Stefanadis, C. (2012) Prediction of cardio-vascular events and all-cause mortality with brachial-ankle elasticity index: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Hypertension, 60, 556-562.

Vlachopoulos, C., Xaplanteris, P., Aboyans, V., Brodmann, M., Cifkova, R., Cosentino, F., De Carlo, M., Gallino, A., Landmesser, U., Laurent, S., Lekakis, J., Mikhailidis, D.P., Naka, K.K., Protogerou, A.D., Rizzoni, D., et al. (2015) The

Y. Zhang et al. 270

role of vascular biomarkers for primary and secondary preven-tion. A position paper from the European Society of Cardi-ology Working Group on peripheral circulation: endorsed by the Association for Research into Arterial Structure and Physi-ology (ARTERY) Society. Atherosclerosis, 241, 507-532.Willum-Hansen, T., Staessen, J.A., Torp-Pedersen, C., Rasmussen, S., Thijs, L., Ibsen, H. & Jeppesen, J. (2006) Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation, 113, 664-670.

动脉粥样硬化病理变化 动脉粥样硬化(atherosclerosis)是严重危害人类健康的常见病,近年来发病逐年上升,发达国家发病率高于落后国家。 动脉硬化一般是指一组动脉的硬化性疾病,包括:动脉粥样硬化,主要累及大中动脉,危害较大:动脉中层钙化,老年人常见,危害较小;细动脉硬化,见于高血压病。 一、动脉粥样硬化的危险因素 1.高脂血症(hyperlipemia): 高脂血症是动脉粥样硬化的重要危险因素,研究表明,血浆低密度脂蛋白(LDL),极低密度脂蛋白(VLDL)水平升高与动脉粥样硬化的发病率呈正相关。高甘油三酯亦是本病的独立危险因素。相反,高密度脂蛋白(HDL)有抗动脉粥样硬化作用。 2.高血压: 高血压可引起血管内皮细胞损伤和(或)功能障碍,促使动脉粥样硬化发生。另一方面,高血压时有脂质和胰岛素代谢异常,这些均可促进动脉粥样硬化发生。 3.吸烟: 大量吸烟可使血液中LDL易于氧化;烟内含有一种糖蛋白,可引起SMC增生;吸烟可使血小板聚集功能增强,儿苯酚胺浓度升高,但使不饱和脂肪酸及HDL水平下降,这些均有助于动脉粥样硬化的发生。 4.性别: 女性的血浆HDL水平高于男性,而LDL水平却较男性为低,这是由于雌激素可降低血浆胆固醇水平的缘故。 5.糖尿病及高胰岛素血症: 糖尿病患者血液中HDL水平较低,且高血糖可致LDL糖基化。高胰岛素血症可促进SMC 增生,而且胰岛素水平与血HDL含量呈负相关。 6.遗传因素: 冠心病的家族聚集现象提示遗传因素是本病的危险因素。遗传性高脂蛋白性疾病可导致动脉粥样硬化的发生。 二、动脉粥样硬化发生机制学说: 动脉粥样硬化的发病机制至今尚不明确,主要学说有: 1. 脂源性学说: 高脂血症可使血管内皮细胞损伤及脱落,管壁透性增高,脂蛋白进入内膜引起巨噬C反应,SMC增生并形成斑块。 2. 致突变学说: 认为动脉粥样硬化斑块内的平滑肌细胞为单克隆性,即由一个突变的SMC子代细胞迁入内膜,分裂增殖形成斑块,犹如平滑肌瘤一般。 3. 损伤应答学说: 各种原因引起内皮损伤,使之分泌生长因子,吸引单核C附着于内皮,并移入内膜下刺激SMC增生,并分泌各种因子相互作用形成纤维斑块。 4.受体缺失学说: 若血浆中LDL受体数目过少,则导致细胞从循环血中清除LDL减少,从而使血浆LDL升高。 三、病理变化 动脉粥样硬化病变的发生与年龄的关系十分密切,动脉杈、分支开口,血管弯曲的凸面为病变的发生部位。病变过程由轻至重,分为四期: 1.脂纹(fatty streak):

动脉硬化 引起动脉硬化的病因中最重要的是高血压、高脂血症、抽烟。其他诸如肥胖、糖尿病、运动不足、紧张状态、高龄、家族病史、脾气暴躁等都会引起动脉硬化。动脉硬化症能治疗吗?动脉硬化是随着年龄增长而出现的血管疾病,其规律通常是在青少年时期发生,至中老年时期加重、发病。男性较女性多,近年来本病在我国逐渐增多,成为老年人死亡主要原因之一。 动脉硬化症状 动脉硬化的表现主要决定于血管病变及受累器官的缺血程度,对于早期的动脉硬化患者,大多数患者几乎都没有任何临床症状,都处在隐匿状态下潜伏发展。对于中期的动脉硬化患者,大多数患者都或多或少有心悸、胸痛、胸闷、头痛、头晕、四肢凉麻、四肢酸懒、跛行、视力降低、记忆力下降、失眠多梦等临床症状,不同的患者会有不同的症状。一般表现为脑力与体力衰退,触诊体表动脉如颞动脉、桡动脉、肱动脉等可发现变宽变长、迂曲和变硬。 动脉硬化症调理 ①劳逸结合与精神调节避免精神紧张、烦恼焦虑,生活要有规律,学会 经常用脑,又要避免用脑过度。 ②合理饮食预防动脉粥样硬化,最主要的饮食原则是限制脂肪摄入量。摄 入动物脂肪(主要含饱和脂肪酸)不宜过多,应少食肥肉、猪油、奶油或其他动物油。饱和脂肪酸对心血管系统有不利的影响,可以促进食物中胆固醇的吸收,并使形成的脂蛋白易于附着在血管壁上,有的还能引起“低密度脂蛋白胆固醇”在血液中堆积,从而促进动脉粥样硬化的发展。 ②现代科学研究证实,富含不饱和脂肪酸的食物,可以减低血浆中甘油三

酯的含量,并能抑制血小板功能,从而降低动脉粥样硬化及冠心病的发 病率和死亡率。可多吃一些含不饱和脂肪酸较多的鱼类、植物油、豆制 品等。另外,少吃甜食,多吃新鲜蔬菜和水果,保证足够的维生素和钾、钙等,有益于营养素及植物纤维的摄入。摄入适量的盐(5克/天),不吸 烟、少饮酒或不饮酒等,这些都有利于预防动脉粥样硬化的发生。 ③体力活动积极地参加力所能及的体育锻炼和体力活动,可帮助改善血 液循环,增强体质,并防止肥胖。 ④早期采取治疗措施一级预防的重点有三个:干预血糖、干预血压、干预 血脂。力争在早期采取治疗措施。 动脉硬化的饮食疗法 1、大豆:研究人员发现,每天吃115 克豆类,血胆固醇可降低20% ,特别是与动脉粥样硬化形成有关的低密度脂蛋白降低明显。 2、茶叶:茶能降血脂,茶区居民血胆固醇含量和冠心病发病率明显低于其他地区。 3、大蒜:大蒜可升高血液中的高密度脂蛋白,对防止动脉硬化有利。 4、茄子:茄子在肠道内的分解产物,可与体内过多的胆固醇结合,使之排出体外。 5、香菇及木耳:能降低胆固醇和甘油三脂。据研究,其降胆固醇的作用比降血脂药物的疗效更好。 6、洋葱及海带:洋葱可使动脉脂质沉着、减少;海带中的碘和镁,对防止动脉脂质沉着也有一定作用。 7、鱼类:鱼中含有大量高级不饱和脂肪酸,对降低血胆固醇有利,渔民冠

下肢动脉硬化的治疗 近些年来,随着生活水平的不断提高,会患动脉硬化闭塞症的人群也是每年都会有所增长,而此病也成为了四肢血管的常见疾病之一。而且会得此病的都是一些中老年,此病的危害性也是比较严重的,所以治疗就成了患此病人群所关注的重点了。下面就请专家来介绍一下下肢动脉硬化的治疗方法是什么? 随着年龄的增长会患此病的几率也就越高,所以,一旦患上这种疾病,会严重影响到病患的生活,而此病在早期又没有什么特殊的病症,所以很容易被忽略,而一旦出现了明显症状就说明已经严重了。 (1)戒烟:吸烟与下肢缺血性疾病的关系已经很明确,吸烟者发生间歇性跛行是非吸烟者的9倍。间歇性跛行患者中几乎90%以上是吸烟者。吸烟可以从多方面对动脉硬化产生影响。 因此戒烟是下肢动脉硬化闭塞症的重要治疗措施。对戒烟的重要性无论怎样强调都不过分。Quick报道间歇性跛行的患者停止吸烟后症状改善踝动脉压增高。血管移植术后在戒烟者5年通畅率

77%,而继续吸烟者仅42%。 (2)运动锻炼:适当的有规律的进行步行锻炼,可以使80%以上患者的症状得到缓解。通过运动使症状得到缓解的作用机制尚不清楚。以前认为运动可以使侧支血管增多,口径变大,血流量增加,但是现有的资料及检查手段并不支持这一学说。目前认为运动使肌肉内的酶发生了适应性的变化,使之更有效的从血流中吸取氧。从腘静脉采血化验发现经过运动锻炼的患者氧的摄取量明显增加。运动锻炼的方法是,患者坚持步行直到症状出现后停止,待症状消失后再步行锻炼,如此反复运动每天坚持1h。 (3)降血脂药物:血脂过高的病人经饮食控制后血脂仍不降者,可用降血脂药物治疗,目前发现的最强的抗血凝物质(新洷康)天然水蛭素有望成为心脑血管疾病的首选。 (4)降血压药物:动脉硬化闭塞症的病人有40%~50%伴有高血压,常给手术带来一定的危险性,故应同时治疗高血压。常用的降血压药物有复方降压片、美托洛尔(倍他乐克)、卡托普利(开搏通)、珍菊降压片等,需根据降压情况,调节剂量。

动脉粥样硬化得病理改变 首都医科大学陈瑞芬 一、概述 心血管系统疾病就是当今严重威胁人类健康常见得重要疾病。在我国与欧美等一些发达国家, 心血管系统疾病得发病率与死亡率均居第一位。 动脉硬化症就是一组动脉疾病得统称,指动脉壁增厚、硬化、弹性减退,这些疾病包括:动脉粥样硬化症、动脉中膜钙化以及细动脉硬化症。动脉粥样硬化就是指管壁表面得内膜柱出现大小不等得动脉粥样硬化斑块细动脉硬化,主要表现在细动脉出现玻璃样变。动脉中层钙化在我国较少见,病变主要发生在肌型动脉,以中层钙化为特征,常见于老年人。细动脉硬化症常见于高血压。 动脉粥样硬化 (atherosclerosis AS) 就是心血管系统疾病中最常见得疾病 , 主要累及大、中动脉。我国 AS 发病率呈上升趋势 , 多见于中、老年人 , 以 40 ~ 50 岁发展最快。 二、动脉粥样硬化病因发病 动脉粥样硬化病因发病危险因素包括以下方面: (一)高脂血症 高脂血症就是指血浆总胆固醇 (TC) 、甘油三酯 (TG) 得异常增高。胆固醇在血浆中主要表现为血浆低密度脂蛋白 (LDL)、极低密度脂蛋白 (VLDL)以及高密度脂蛋白(HDL、好胆固醇),LDL、VLDL(坏胆固醇)得水平持续升高与 AS 得发病率呈正相关,高密度脂蛋白(HDL、好胆固醇) 水平得降低与 AS 得发病率呈正相关,LDL与VLDL就是判断AS与冠心病得最重要指标。 研究发现:LDL被动脉壁细胞氧化修饰后具有促进动脉斑块形成得作用,氧化得LDL就是最重要得致动脉粥样硬化因子,就是损伤内皮细胞与平滑肌细胞得主要因子,氧化得LDL 不能被正常LDL受体识别,而易被巨噬细胞得清道夫受体识别,而快速被吞噬、摄取,促进巨噬细胞形成泡沫细胞。HDL可运载血中胆固醇到肝脏,因而可以防止胆固醇在血管壁得沉积。

防治动脉硬化的中草药有哪些 文章目录*一、防治动脉硬化的中草药有哪些*二、动脉硬化的症状*三、动脉硬化的食疗方法 防治动脉硬化的中草药有哪些1、防治动脉硬化的中草药有 哪些 1.1、中成药:根据病情在医生指导下可经常选用人参归脾丸、天王补心丹、六味地黄丸、金匮肾气丸、人参鹿茸丸等中成药, 每次服1丸,日服2次,连服2~3个月。 1.2、药枕治疗:取杭菊花500克、冬桑叶500克、野菊花500克、辛夷500克、薄荷200克、红花100克。将上述药混匀粉碎,拌入冰片50克,装入布袋,作睡枕用,可用6个月,若回潮则置太阳下晒。 2、动脉硬化是什么 动脉硬化是动脉的一种非炎症性病变,是动脉管壁增厚、变硬,失去弹性和管腔狭小的退行性和增生性病变的总称,常见的有:动脉粥样硬化;动脉中层钙化;小动脉硬化(arteriolosclerosis)3种。动脉粥样硬化(atherosclerosis) 是动脉硬化中常见的类型,为心肌梗塞和脑梗塞的主要病因。 3、动脉硬化的病理病因 动脉粥样硬化的病理变化主要累及体循环系统的大型弹力 型动脉(如主动脉)和中型肌弹力型动脉(以冠状动脉和脑动脉罹

患最多,肢体各动脉、肾动脉和肠系膜动脉次之,脾动脉亦可受累),而肺循环动脉极少受累。病变分布多为数个组织和器官同时受累,但有时亦可集中在某一器官的动脉,而其他动脉则正常。最早出现病变的部位多在主动脉后壁及肋间动脉开口等血管分支处;这些部位血压较高,管壁承受血流的冲击力较大,因而病变也较明显。 动脉硬化的症状 本病起病缓慢。早期患者常表现为头痛、头晕或眩晕耳鸣。患者自觉疲乏无力、嗜睡或失眠多梦,且注意力不集中,记忆力减退,尤其对近事容易遗忘;经常情绪不稳,易烦躁,激怒,多疑,固执,不听他人劝说;工作效率低,对事物的理解能力和判断力差, 并且随着脑力和体力活动而加重;有的患者则表现为肢体麻木震颤,表情淡漠,性情孤僻,不愿和他人来往,常常沉默寡言或自言 自语,语无伦次;有的患者对事物反应迟钝,对一些简单的基本计算感到困难,甚至发生二便失禁等症。 本病病情可反复发作,每次发作持续数分钟至24小时,发作后症状及体征可基本消失。随着脑动脉硬化的逐渐加重,本病还可出现脑动脉硬化综合征,其表现有:假性延髓麻痹综合征;患者可表现出吞咽困难,饮水时发呛,音哑;精神障碍综合征:患者以 痴呆为主,或出现幻觉、虚构、妄想、多语、人格改变、智能障碍;癫痫综合征:患者表现为局部或全身性痉挛发作。

动脉硬化手术的方法 很多老年人缺乏体育锻炼,就会出现很多种情况,动脉血管硬化就是现在发病率最高的一种疾病,这种疾病可能会使血液反流,出现的问题是相当严重的,严重的患者还会有生命危险,可能大家对于动脉硬化手术的方法的问题还没有一个清晰的认识,下面就让我们一起来了解一下动脉硬化手术的方法的相关问题吧。 1.非手术疗法,包括控制饮食适当锻炼忌烟保暖;应用降血 脂药物血管扩张剂及中医药;肢体负压治疗等以上治疗也可用于手术前后, 2.手术疗法,根据病变部位程度范围及侧支循环情况可选用以下手术方法:(1)动脉旁路手术,应用人工血管或自体静脉在闭塞动脉的近远端作桥式端侧吻合以重建血流可分为解剖位旁路(位于病变附近)和非解剖位旁路(远离病变部位)前者常用后者 仅在局部感染或难以耐受剖腹剖胸手术时应用

3.其原理是利用高速旋转装置将粥样斑块研磨成极细小的 微粒,被粉碎的粥样斑块碎屑及微粒粒可被网状内皮系统吞噬,不致引起远端血管堵塞。下肢动脉硬化闭塞症动脉粥样斑块旋切术理论上能在切除血管壁钙化硬斑同时,不损伤血管壁.该类手术有几个优点:下肢动脉硬化闭塞症(1)介入操作成功率高下肢动脉硬化闭塞症(2)治疗指征宽下肢动脉硬化闭塞症(3)可重复 操作。 4.一组下肢动脉硬化闭塞症46例股胭动脉阻塞病人,病变长度在2-20cm之间,应用Kensey导管治疗的下肢动脉硬化闭塞症临床结果显示,操作成功率为87%,其中有4例下肢动脉硬化闭塞症穿孔但无需进一步手术治疗。下肢动脉硬化闭塞症半年通畅率为72%,下肢动脉硬化闭塞症1年通畅率为70%。但也有报道称下肢动脉硬化闭塞症此项技术与以往PTA的报道相比,虽然该技术初期成功率高,但下肢动脉硬化闭塞症近期和下肢动脉硬化闭塞症无期疗效比PTA低得多,可能原因包括钻头振动引起对血管壁的机械性刺激。 我们应该多吃一些有利于血管软化的食物,同时以上动脉硬化手术的方法效果也非常显著,做好相关的预防对于我们预防出现动脉血管硬化情况非常有帮助,同时适当的加强体育锻炼也是

动脉粥样硬化 【病因和发病情况】2 【发病机制】3 【病理解剖和病理生理】4 【诊断和鉴别诊断】8 【预后】8 【防治】9 动脉粥样硬化(atherosclerosis)是一组称为动脉硬化的血管病中最常见、最重要的一种。各种动脉硬化的共同特点是动脉管壁增厚变硬、失去弹性和管腔缩小。动脉粥样硬化的特点是受累动脉的病变从膜开始,先后有多种病变合并存在,包括局部有脂质和复合糖类积聚、纤维组织增生和钙质沉着形成斑块,并有动脉中层的逐渐退变,继发性病变尚有斑块出血、斑块破裂及局部血栓形成(称为粥样硬化一血栓形成,atherosclerosis-thrombosis)。现代细胞和分子生物学技术显示动脉粥样硬化病变具有巨噬细胞游移、平滑肌细胞增生;大量胶原纤维、弹力纤维和蛋白多糖等结缔组织基质形成;以及细胞、外脂质积聚的特点。由于在动脉膜积聚的脂质外观呈黄色粥样,因此称为动脉粥样硬化。 其他常见的动脉硬化类型还有小动脉硬化(arteriolosclerosis)和动脉中层硬化(Monckeberg arteriosclerosis)。前者是小型动脉弥漫性增生性病变,主要发生在高血压患者。后者多累及中型动脉,常见于四肢动脉,尤其是下肢动脉,在管壁中层有广泛钙沉积,除非合并粥样硬化,多不产生明显症状,其临床意义不大。 鉴于动脉粥样硬化虽仅是动脉硬化的一种类型,但因临床上多见且意义重大,因此习惯上简称之“动脉硬化”多指动脉粥样硬化。

【病因和发病情况】 本病病因尚未完全确定,对常见的冠状动脉粥样硬化所进行的广泛而深入的研究表明,本病是多病因的疾病,即多种因素作用于不同环节所致,这些因素称为危险因素(risk factor)。主要的危险因素为: (一)年龄、性别 本病临床上多见于40岁以上的中、老年人,49岁以后进展较快,但在一些青壮年人甚至儿童的尸检中,也曾发现他们的动脉有早期的粥样硬化病变,提示这时病变已开始。近年来,临床发病年龄有年轻化趋势。男性与女性相比,女性发病率较低,但在更年期后发病率增加。年龄和性别属于不可改变的危险因素。 (二)血脂异常 脂质代异常是动脉粥样硬化最重要的危险因素。总胆固醇(TC)、甘油三酯(TG)、低密度脂蛋白(low density lipoprotein,LDL,特别是氧化的低密度脂蛋白)或极低密度脂蛋白(very low density lipoprotein,VLDL)增高,相应的载脂蛋白B(ApoB)增高;高密度脂蛋白(high density lipoprotein,HDL)减低,载脂蛋白A(apoprotein A,ApoA)降低都被认为是危险因素。此外脂蛋白(a)[Lp(a)]增高也可能是独立的危险因素。在临床实践中,以TC及LDL增高最受关注。 (三)高血压 血压增高与本病关系密切。60%~70%的冠状动脉粥样硬化患者有高血压,高血压患者患本病较血压正常者高3~4倍。收缩压和舒压增高都与本病密切相关。 (四)吸烟 吸烟者与不吸烟者比较,本病的发病率和病死率增高2~6倍,且与每日吸烟的支

主动脉硬化治疗方法标准化管理处编码[BBX968T-XBB8968-NNJ668-MM9N]

主动脉硬化 动脉硬化是动脉的一种非炎症性病变,可使动脉管壁增厚、变硬,失去弹性、管腔狭窄。动脉硬化是随着年龄增长而出现的血管疾病,其规律通常是在青少年时期发生,至中老年时期加重、发病。主动脉硬化是动脉硬化中常见的类型。动脉硬化有三种主要类型: ①细小动脉硬化;②动脉中层硬化;③动脉粥样硬化。本病主要累及主动脉、冠状动脉、 脑动脉和肾动脉,可引起以上动脉管腔变窄甚至闭塞,会导致主动脉夹层、腹动脉瘤;引起其所供应的器官血供障碍,导致这些器官发生缺血性病理变化。 病因 引起主动脉硬化的病因中最重要的是高血压、高脂血症、抽烟。其他诸如肥胖、糖尿病、运动不足、紧张状态、高龄、家族病史、脾气暴躁等都会引起动脉硬化。 临床表现 大多数无特异性症状。叩诊时可发现胸骨柄后主动脉浊音区增宽;主动脉瓣区第二心音亢进而带金属音调,并有收缩期杂音。收缩期血压升高,脉压增宽,桡动脉触诊可类似促脉。X线检查可见主动脉结向左上方凸出,主动脉扩张与扭曲,有时可见片状或弧状的斑块内钙质沉着影。 病变多发生于主动脉后壁和其分支开口处。腹主动脉病变最严重,其次是降主动脉和主动脉弓,再次是升主动脉。病变严重者,斑块破裂,形成粥瘤性溃疡,其表面可有附壁血栓形成。 有的病例因中膜SMC萎缩,弹力板断裂,局部管壁变薄弱,在血压的作用下管壁向外膨出而形成主动脉瘤。这种动脉瘤主要见于腹主动脉。偶见动脉瘤破裂,发生致命性大出

血。有时可发生夹层动脉瘤。有的病例主动脉根部内膜病变严重,累及主动脉瓣,使瓣膜增厚、变硬,甚至钙化,形成主动脉瓣膜病。 检查 血管应从功能与结构两方面来评价:功能为血管的弹性情况;结构为血管的狭窄情况。现有一种最新的无创检查动脉硬化的方法可同时测量两个指标:ABI踝臂指数、PWV 脉搏波传导速度。 1.实验室检查 本病尚缺乏敏感而又特异性的早期实验室诊断方法。患者多有脂代谢失常,主要表现为血总胆固醇增高、LDL胆固醇增高、HDL胆固醇降低、血甘油三酯增高、血脂蛋白增高、载脂蛋白B增高、载脂蛋白A降低、脂蛋白(α)增高增高、脂蛋白电泳图形异常,90%以上的患者表现为Ⅱ或Ⅳ型高脂蛋白血症。 2.血液流变学检查 往往示血黏滞度增高。血小板活性可增高。 3.X线检查 X线检查可见主动脉的相应部位增大;主动脉造影可显示出梭形或囊样的动脉瘤。二维超声显像、电脑化X线断层显像、磁共振断层显像可显示瘤样主动脉扩张。主动脉瘤一旦破裂,可迅速致命。动脉粥样硬化也可形成夹层动脉瘤,但较少见。 4.多普勒超声检查 5.血管内超声和血管镜检查

动态的动脉硬化指数的应用及意义 2006年初,我们提出了一种利用常规的24小时动态血压监测数据反映动脉硬化程度的新指数,称之为动态的动脉硬化指数(Ambulatory Arterial Stiffness Index,AASI)。 实际上,早在1914年,英国学者MacWilliam等已经阐述了收缩压与舒张压的变化与血管弹性之间的关系。如果动脉血管健康而有弹性,当收缩压升高时,舒张压也相应增加。当动脉血管的弹性降低时,随着收缩压的升高,舒张压增高不明显,有时甚至会降低。这说明收缩压和舒张压变化的关系可以反映动脉血管的弹性功能。人类24小时血压的昼夜变化,正好提供了在不同生理情况下的一系列收缩压与舒张压的数值。利用这些血压变异,可以计算出舒张压和收缩压变化之间的关系。因此,我们假设24小时动态的舒张压与收缩压之间的回归斜率可以反映动脉硬化程度。AASI定义为1减去该回归斜率。动脉硬化程度越严重,AASI越趋向于1。 我们首先将AASI与现有的动脉硬化指数进行了比较。采用脉搏波分析仪检测颈-股动脉脉搏波传导速度(PWV)、中心和外周脉搏压、中心(CAIx)和外周(PAIx)反射波增压指数等反映动脉硬化的指标,同时进行24小时动态血压检测。在166例志愿者中,AASI与PWV显著相关(相关系数r=0.51,P <0.0001)。在348例自然人群样本中,AASI与 CAIx(r=0.48)、PAIx(r=0.50)及中心脉压(r=0.50)等密切关联(P<0.0001)。调整可以影响动脉反射波的身高和心率等变量前后,AASI比24小时脉压与CAIx及PAIx相关程度更为密切(P<0.0001)。在年龄小于40岁的年轻人中,24小时脉搏压与收缩期增压指数间没有关联,而AASI则与CAIx和PAIx等均显著相关(P < 0.05)。提示AASI可能是反映动脉硬化程度的早期指标。 AASI随着年龄及平均动脉压的升高而上升,随着身高的增加而下降,而与24小时平均心率无关。女性平均AASI高于男性。在血压正常的受检者中,AASI的95百分位数为0.55。AASI的正常参考值范围是:年轻人(20岁)<0.50,老年人(80岁)<0.70。这一参考值还有待在前瞻性研究中进一步证实。 AASI作为动脉硬化指数,与靶器官损伤密切相关,并可预测心脑血管危险。在188 例未治疗的意大利高血压病人中,AASI每增加一个标准差(0.17单位),患微量白蛋白尿、颈动脉斑块或内中膜增厚、左心室肥厚的危险增加2倍。 AASI与24小时尿蛋白排泄量呈正相关,与肌酐清除率呈负相关。在都柏林心血管研究中,11291例高血压患者平均随访5.3年后,AASI可独立于传统心脑血管病危险因素,预测心血管死亡,尤其对中风有较强的预测能力。在丹麦的一个40岁以上的自然人群中(n=1829),平均随访9.4年,AASI 每增加一个标准差(0.14单位),发生中风的相对危险比为1.62(95%CI 1.14-2.28,P=0.007)。在日本的OHASAMA人群研究中,随着递增的AASI的四分位数,发生心血管死亡和致死性中风的危险呈“U”字型,进一步证实了AASI可在亚洲人群中预测心血管死亡和致死性中风。

心血管动脉硬化治疗的方法 一、症状确诊后,应首先进行非药物治疗。 首先,应注意加强体力和体育锻炼:身体运动有利于改善血液循环,促进脂类物质消耗,减少脂类物质在血管内沉积。 其次,注意控制饮食:饮食宜清淡,不可吃得太饱,最好戒烟忌酒。 第三,药物仪器治疗:目的是降低血液的脂质浓度,扩张血管,改善血液循环,活化脑细胞等。 但我不推荐药物,大家都知道是药三分毒的道理,尽量少吃药。 低强度的净雪激光治疗仪通过特定强度的激光照射,改变血液流变学性质,降低全血粘度及血小板凝集能力,净化血液,清除血液中的毒素、自由基(地球人都知道“血液是健康之本”)配合饮食和体育锻炼, 科学研究证明:全身血液每3分钟流过鼻腔一次,鼻腔粘膜最薄,"净雪激光治疗仪"采用波长为650纳米的低强度激光通过鼻腔照射,能从根本上康复心脑血管疾病。 三者结合,控制饮食和加强体育锻炼,医疗仪器治疗,效果更佳。 二、平时监控血压、血糖、血脂。戒烟戒酒。如果有高血压、高血糖的情况,可以进行心脑血管疾病的一级预防:即口服小剂量的阿司匹林(100mg,每天,年龄最好不要超过80岁)、阿托伐他汀钙(10mg每天、这个药比较贵,要看经济情况),中成药也有很好的,比如丹参。 三、预防动脉硬化的几种常见食物 生姜:有一种油树脂,具有降低血脂和胆固醇的作用。 牛奶:还有一种因子,能降低血清胆固醇的浓度,牛奶中还含有大量的钙质,也能起到减少胆固醇的吸收作用。

大豆:含有一种物质,可以降低血液中胆固醇的含量,多食大豆及豆制品极有好处。 大蒜:含有挥发性辣素,可消除积存在血管中的脂肪,有明显降脂作用。 洋葱:可以降低血脂、防治动脉硬化和心肌梗塞方面有作用。 海鱼类:其鱼油中有较多的不饱和脂肪,有激降血压功效。 蜜桔:含有丰富的维生素C,多吃可以提高肝脏解毒功能,加速胆固醇转化,降低血清胆固醇和血脂的含量。 山楂:含有黄铜成分,具有加强和调节心肌,增强心脏收缩的功能及冠脉血管流量的作用,还能降低血清胆固醇,心血管病人多食有益。 茶叶:含有咖啡碱与茶多酚,有提神、强心、利尿、消腻和降脂功能。经常饮茶,可以防止人体内胆固醇的升高。 茄子:含有较多的维生素P,以增强毛细血管的弹性,因此对防治高血压、动脉硬化及脑溢血有一定作用。 燕麦:含有B族维生素、卵磷脂等具有降低胆固醇和甘油三酯的作用,常食可防治动脉硬化。木耳:含有一种多糖物质,能降低血中胆固醇,亦有减肥和抗癌的作用。可以常年煎服和熬汤佐膳。 红薯:可供给人体大量的胶原和粘多糖类,保持动脉血管的弹性,预防动脉硬化。 喝粥防治动脉硬化 玉米粉粥 玉米粉、粳米各50克,先将玉米粉加适量清水调均,待米粥将煮成时加入调好的玉米粉同煮至稠即可。每日服用1-2次。具有益肺宁心,调中开胃等功效。适用于动脉硬化、高血脂、冠心病及心肌梗塞等心血管病患者。

脑动脉硬化的治疗方法 动脉硬化 - 来源:爱心中医药资讯网 所谓脑动脉硬化是指脑血管的慢性与增生性改变,主要发生于中老年人。据美国统计,在脑血管死亡的人群中,半数归因于脑动脉硬化。病理改变可分三型:动脉粥样硬化、弥漫性小动脉硬化,微血管玻璃样变与纤维化,分别与血脂代谢紊乱,高血压病和糖尿病较为密切,但相互之间又都关系,其他常见病因为肥胖、吸烟、运动太少、内分泌紊乱,遗传等。 脑动脉硬化除了容易并发各种脑血管病急性发作外,由于严重、广泛的血管硬化、狭窄常可引起局部或全脑血流量减少,而使脑组织缺血、萎缩;脑部细微动脉的硬化,还易引起多发性微栓塞。 当脑功能受到广泛影响并出现特有的临床症状时,就称为脑动脉硬化症。 脑动脉硬化症最常见的临床表现有:(1)神经衰弱征候群:头晕、头痛、失眠、多虑、注意力不集中、记忆力减退(特别是近期记忆)、思维能力缓慢、活动能力下降。(2)脑动脉硬化性痴呆:主要表现为精神情感障碍。不能准确计算和说出时间、地点、人物,出现明显性格改变,如情感淡漠、思维迟缓、行为幼稚、不拘小节,有时其举动象平常所说的"老顽童",严重者还可出现妄想、猜疑、幻觉等各种精神障碍。(3)假性球麻痹("球"指脑干的延髓):表现为四肢肌张力增高,出现难以自我控制的强哭强笑,哭笑相似分不清、吞咽困难伴呛咳及

流涎等。(4)帕金森综合征:面部缺乏表情,直立时身体向前弯,四肢肌强直而肘关节略屈,手指震颤呈搓丸样,步态小而身体前冲。[治法]:活血通络,滋阴补肾 丹参18 玄参15 麦冬12 生地18 石菖蒲10 川芎15 当归18 黄精18 牛膝10 姜黄10 枸杞子18 夏枯草18 [加减]: (1)肢体麻木,加鸡血藤30 (2)腰膝酸痛,加杜仲18 川断15 (3)四肢颤动不定者,加珍珠母30(先煎) 龙齿30(先煎) (4)失眠者,加酸枣仁18 远志9 (5)抽搐者,加全蝎9 广地龙12 病情分析: 1,避免精神紧张,情绪波动,以减少脑血管痉挛的发生. 2,要注意劳逸结合,参加一些力所能及的活动,如散步,体操,打太极拳,下棋,旅游等.这些活动可以使血流畅通,增强体质. 3,吸烟可引起血管硬化,长期大量饮酒可促使动脉硬化,所以应戒烟和少饮酒. 意见建议: 4,合理的饮食对动脉硬化的预防是有效果的,避免食用量脂脉或胆固醇的食物.瓜果蔬菜,含维生素丰富的食物则应注意补充. 5,要认真坚持治疗高血压,糖尿病等,因为这些慢性病的发展可促进脑动脉硬化.

动脉粥样硬化发病机制 动脉粥样硬化的发生发展机制目前仍不能全面解释,但经过多年的研究和探索主要形成了以下几种学说,脂代谢紊乱学说、内皮损伤学说、炎症反应学说、壁面切应力以及肠道微生物菌群失调等,这些学说从不同角度阐述了动脉粥样硬化的发生过程。 1、脂质代谢紊乱学说 高血脂作为AS的始动因素一直是相关研究的热点。流行病学资料提示,血清胆固醇水平的升高与AS的发生呈正相关。在高血脂状态下血浆低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(LDL-C)浓度升高,携带大量胆固醇的LDL-C 在血管内膜沉积,并通过巨噬细胞膜上的低密度脂蛋白受体(LDL-R)携带胆固醇进入细胞内。同时血液中及血管内膜下低密度脂蛋白(LDL)经过氧化修饰后形成氧化型低密度脂蛋白(Ox-LDL),其对单核巨噬细胞表面的清道夫受体(如: CD36,SR-A,LOX1)具有极强的亲和力,导致Ox-LDL 被迅速捕捉并被吞噬。然而Ox-LDL 对巨噬细胞具有极强的毒害作用,可以刺激单核巨噬细胞的快速激活增殖聚集退化,然后凋亡为泡沫细胞,这些泡沫细胞的大量聚集便形成了As 的脂质斑块。此外,Ox-LDL 通过与血管内皮细胞LOX1 结合导致细胞内信号紊乱并引起内皮细胞功能障碍。Ox-LDL还能促进血管平滑肌细胞不断增殖并向外迁移在血管内壁形成斑块。从脂代谢紊乱学说的病变过程中可以看出,血管内皮功能受损和氧化应激是动脉粥样硬化发生的重要环节。同时对于AS 动物模型的诱导当前国内外使用最多的方法是饲喂高脂高胆固醇饲料促使脂代谢紊乱。 2、内皮损伤学说 在正常情况下动脉血管内膜是调节组织与血液进行物质交换的重要屏障。由于多种因素(如: 机械性,免疫性,LDL,病毒等)刺激内皮细胞使其受到严重损伤导致其发生功能紊乱与剥落,进而改变内膜的完整性与通透性。血液中的脂质会大量沉积于受损内膜处,促使平滑肌细胞和单核细胞进入内膜并大量吞噬脂质形成泡沫细胞,泡沫细胞的不断累积便形成脂肪斑块。同时内皮细胞的凋亡与脱落促使血液中血小板大量粘附与聚集,功能紊乱的内皮细胞、巨噬细胞、血小板分泌产生大量生长因子和多种血管活性物质刺激中膜平滑肌细胞不断增生并进入内膜,同时导致血管壁产生收缩。其结果是脂肪斑块不断增大,同时管腔在不断缩小,进而导致AS 病变的形成。 3、炎症反应学说 As 并不是单纯的脂质在血管壁沉积性疾病,而是一个慢性低度炎症反应的过程,氧化应激过程贯穿于动脉粥样硬化的整个过程。某些脂类如溶血磷脂、氧固醇等作为信号分子与细胞的受体结合后可激活特定基因表达,生成许多促进炎性反应的细胞因子。在动脉粥样硬化病变过程中,血管内膜功能受损,导致ICAM1、M-CSF、MCP1、VCAM1、MMP 等细胞因子和炎性因子的表达明显增加,促进单核细胞与内皮细胞粘附、迁移进入内膜并吞噬Ox-LDL 形成泡沫细胞,促使中层平滑肌细胞增殖并向内膜方向迁移摄取脂质形成泡沫细胞。随着动脉粥样硬化的进展,炎性细胞和吞噬了Ox-LDL 的巨噬细胞增多,并产生肿瘤坏死因子-α(TNF-α)、白介素8(IL-8)、白介素1(IL-1)等多种重要的炎性因子进一步加剧动脉粥样硬化的发生与发展。C 反应蛋白(CRP)是一种急性炎症反应物质,在临床研究中常作为全身炎症反应的敏感指标,同时研究证明CRP 是动脉硬化心血管事件的独立危险因子,对于心血管疾病预测的价值超过LDL-C 及一些传统的心血管预测因子。而CRP 不仅是炎症标志物也是一种炎症促进因子,直接参与动脉硬化斑块的形成与聚集,促使炎症反应放大。综上所述,炎症反应可能是众多危险因素致As的共同通路,这为As新的防治策略——以炎症机制的不同环节为靶向研发新的抗炎药物、用于As性疾病的治疗提供了理论基础。 4、壁面切应力

动脉粥样硬化早期诊断及预测 关键词:心血管疾病动脉粥样硬化早期诊断 当冠脉狭窄到一定程度影响正常心肌灌注时才表现出临床症状,可能管腔狭窄程度已经超过60%~70%了,患者可以没有任何症状。而管腔继续狭窄并表现为心绞痛甚至心肌梗死等的症状可能不需要很长的时间。另外,动脉粥样硬化(AS)后血管重塑;冠脉病变的狭窄程度与严重程度不直接相关:多数心血管事件是在易损斑块(斑块破裂、溃疡、出血、糜烂)基础上伴有急性血栓形成,与管腔的狭窄程度没有直接关系;以上各种原因使得动脉粥样硬化的早期诊断和治疗较困难。除了管腔狭窄程度,局部AS的稳定性对急性冠脉综合征的诊断意义更大。易损斑块的检测具有更重要的临床意义。目前,心血管疾病诊治的重点在于发现和治疗心血管管腔狭窄,如血管介入治疗已成为解除由于粥样硬化性动脉管腔堵塞的直接和起效快速的方法之一,但忽视了病变的关键——血管壁。随着对心血管病变的深入研究,逐渐认识到是血管壁的病变而不是管腔病变才是各种心脑血管病事件发生发展的基础,动脉僵硬度(弹性)的改变早于结构改变。早期发现后干预亚临床期血管病变的进展是延缓和控制心脑血管事件的根本措施。因此,动脉粥样硬化的早期诊断就显的相当重要。目前临床上遇到的无论是猝死、心肌梗死、还是脑卒中患者,都是动脉粥样硬化性疾病的“终末期”人群。随着动脉粥样硬化性疾病临床防治重心的前移,人们开始重视动脉粥样硬化临床前期病变(Preclinical Atherosclerosis,PCA)的研究。PCA通常是指已有动脉硬化证据,而尚无重要动脉血管(如冠状动脉、脑动脉、肾动脉以及外周动脉)严重粥样硬化狭窄而导致明确临床症状的情况,也有人称为亚临床动脉粥样硬化病变(Subclinical Atherosclerosis)。如何在高血压、血脂异常、肥胖、糖尿病以及吸烟等传统危险因素上,通过一些无创或者微创的方法加强识别动脉粥样硬化性疾病患者,在他们发展为“终末期”患者之前,采取有效措施进行干预,无论对于群体社会疾病负担的减轻还是个体心血管事件风险的减少都具有重要意义。 AS是一种有局部表现的全身系统性疾病。颈动脉和周围动脉一些易检测部位的动脉斑块可间接反应全身AS情况。周围动脉硬化疾病已经被列为冠心病的等危症,它本身就是个窗口,早期诊断不仅可以检出外周动脉疾病,还对冠心病,脑血管病都有重要的检出意义。早期诊断意义是早期发现和早期干预,周围动脉硬化疾病的病理基础和心脑血管病相同,早期干预对减缓全身动脉硬化的危害有重要意义。近年来,血管结构与功能的检测技术迅速发展,一些能早期发现动脉壁异常的无创性检测方法已经具有临床应用价值。目前无创动脉硬化的检测主要包括以下两个部分,即对动脉功能和结构的评估。动脉功能检测的方法主要包括以下三种:(1)动脉的脉搏波传导速度(Pulse Wave Velocity, PWV);(2)通过进行脉搏波波形分析(Pulse contour analysis),计算反射波增强指数(Augumentation Index,AI); (3)使用超声成像手段,直接检测某个特定动脉管壁的可扩张性和顺应性(Compliance)。动脉结构检测主要有以下二种方法:(1)使用超声、EBCT、螺旋CT和MRI等影像学手段,检测某个动脉的管壁内中膜厚度(Intima-Media Thickness, IMT)、粥样斑块形成情况以及冠状动脉钙化积分等;(2)踝臂血压比值,即Ankle-Brachial Index(ABI),评估下肢动脉血管的开放情况。此外,各种生物标记物如血同型半胱氨酸、脂蛋白a(LP(a))、tPA、PAI-1、纤维蛋白原、微量白蛋白尿和C反应蛋白(CRP)等和内皮功能的检测,也有助于诊断动脉血管结构和功能病变。 1 脉搏波传导速度(PWV)心脏将血液搏动性地射入主动脉,主动脉壁产生脉搏压力波,并以一定的速度沿血管壁向外周血管传导,这种脉搏压力波在动脉壁的传导速度叫脉搏波传导速度(PWV)。PWV与动脉壁的生物力学特性、血管的几何特性及血液的密度等因素有一定的关系,其大小是反映动脉僵硬度的早期敏感指标,数值愈大,表示血管壁愈

主动脉硬化的治疗方法 脑动脉硬化是指脑动脉的管壁由于脂类物质沉积和内膜受损,血小板、纤维素等物质积聚在损伤的血管壁的内膜上,使管壁结缔组织增生,内膜粗糙,弹性减退,管腔狭窄,以至影响正常的血液循环和供氧。如果患者不加以控制,就会影响脑部的供血供氧。所以,动脉硬化的治疗具有重要意义。 1、发挥病人的主观能动性配合治疗 已有客观证据表明:本病经防治病情可以控制,病变可能部分消退,病人可维持一定的生活和工作能力,病变本身又可以促使动脉侧枝循环的形成,使病情得到改善。因此说服病人耐心接受长期的防治措施至关重要。 2、合理安排工作和生活 生活要有规律,保持乐观、愉快的情绪,避免过度劳累和情绪激动,注意劳逸结合,保证充分睡眠。 3、提倡不吸烟 不饮烈性酒或大量饮酒(少量饮低浓度酒则有提高血HDL的作用)。 4、积极治疗与本病有关的疾病 如高血压、脂肪症、高脂血症、痛风、糖尿病、肝病、肾病综合征和有关的内分泌病等。 5、合理的膳食 ⑴膳食总热量勿过高,以维持正常体重为度,40岁以上者尤应预防发胖。正常体重的简单计算法为:身高(cm数)减110=体重(kg数),可资参考。 ⑵超过正常标准体重者,应减少每日进食的总热量,食用低脂(脂肪摄入量不超过总热量的30%,其中动物性脂肪不超过10%)、低胆固醇(每日不超过500mg)膳食,并限制蔗糖和含糖食物的摄入。 ⑶年过40岁者即使血脂不增高,应避免经常食用过多的动物性脂肪和含饱和脂肪酸的植物油,如:肥肉、猪油、骨髓、奶油及其制品、椰子油、可可油等;避免多食含胆固醇较高的食物,如:肝、脑、肾、肺等内脏,鱿鱼,牡蛎,墨鱼,鱼子,虾子,蟹黄,蛋黄等。若血脂持续增高,应食用低胆固醇、低动物性脂肪食物,如:各种瘦肉,鸡、鸭、鱼肉,蛋白,豆制品等。 ⑷已确诊有冠状动脉粥样硬化者,严禁暴饮暴食,以免诱发心绞痛或心肌梗塞。合并有

动脉粥样硬化 引言 心血管系统部分病理考题较简单,以识记为主,每年考题大都类似,动脉粥样硬化章节需重点把握病理变化。 考纲要求 掌握动脉粥样硬化的病因、发病机制及基本病理变化,动脉粥样硬化所引起的各脏器的病理改变和后果 历年真题 2014 与动脉粥样斑块表面的纤维帽形成关系密切的细胞是 A 平滑肌细胞 B 内皮细胞 C 成纤维细胞 D 单核细胞 答案:A 知识点解析 1. 定义 动脉粥样硬化以血管内膜形成粥瘤或纤维斑块为特征,主要累及大动脉和中等动脉,引起相应器官缺血性改变。 2. 病因(1996,2007) (1)高脂血症:血浆中总胆固醇和甘油三酯异常增高,LDL 和VLDL 增高及HDL 降低与AS 发病率正相关。 (2)高血压:血流对血管壁冲击引起血管内皮损伤。 (3)吸烟:是心梗主要的独立危险因子。由于CO 使血管内皮缺氧性损伤,同时LDL 易于氧化。 (4)致继发性高脂血症疾病:糖尿病,高胰岛素血症,甲减,肾病综合征。 (5)遗传 (6)性别与年龄:女性雌激素作用

(7)代谢综合征 3. 发病机制(1997,2000,2007) (1)脂质渗入学说 (2)损伤应答反应学说: LDL 通过内皮细胞渗入内皮下间隙,单核细胞迁入内膜,ox-LDL 与巨噬细胞表面受体结合形成巨噬细胞源性泡沫细胞; 动脉中膜的SMC 迁入内膜,吞噬脂质形成肌源性泡沫细胞,SMC 增生迁移,合成细胞外基质,形成纤维帽,ox-LDL 使泡沫细胞坏死崩解,形成粥糜样坏死物,粥样斑块形成。 (3)动脉SMC 作用 (4)慢性炎症学说 4. 病理变化(1990,1991,1992,1993,1996,2004,2005,2011,2012,2014,2015,2016,2017) (1)基本病理变化 (A)脂纹:是AS 肉眼可见的最早病变,肉眼观为点状或条纹状黄色不隆起或微隆起于内膜的病灶,常见于主动脉后壁及其分支开口处;光镜下,病灶处内膜下有大量泡沫细胞聚集。泡沫细胞体积大,圆形或椭圆形,胞质内有小空泡,来源于巨噬细胞和SMC,苏丹III 染色橘黄(红)色,为脂质成分。 (B)纤维斑块:由脂纹发展来,肉眼观,内膜表面散在不规则隆起斑块,颜色浅黄,灰黄和瓷白,光镜下,病灶表面一层纤维帽,由大量胶原纤维,蛋白聚糖及散在的SMA 组成,纤维帽下可见数量不等泡沫细胞,SMC,细胞外基质和炎症细胞。 (C)粥样斑块(粥瘤):纤维斑块深层细胞的坏死发展而来,肉眼观,内膜表面可见明显灰黄色斑块,光镜下,纤维帽之下有大量不定形坏死崩解产物,胆固醇结晶,钙盐沉积,斑块底部和边缘出现肉芽组织,少量淋巴细胞和泡沫细胞,中膜因斑块压迫,SMC 萎缩,弹力纤维破坏而变薄。 (D)继发性病变:斑块内出血,斑块破裂,血栓形成,钙化,动脉瘤形成,血管腔狭窄。(2)主要动脉病理变化 (A)主动脉:好发于主动脉后壁及其分支开口处,腹主动脉病变最严重。不引起明显症状,但可导致动脉瘤 (B)冠状动脉:属于中动脉,危害最大,左前降支最多。可导致心梗。 (C)颈动脉和脑动脉:最常见于颈内动脉起始部,基底动脉,大脑中动脉,Willis 环。可致脑萎缩,痴呆,脑梗死(脑软化),可形成动脉瘤(多在Willis 环出),血压突然升高导致脑

1.动脉粥样硬化是动脉硬化的血管病中常见而最重要的一种。各种动脉硬化的共同特点是动脉发生了非炎症性、退行性和增生性的病变,导致管壁增厚变硬,失云弹性和管腔缩小。动脉粥样硬化的特点是在上述病变过程中,受累动脉的病变从内膜开始,先后有多种病变合并存在,包括局部有脂质和复合糖类积聚,纤维组织增生和钙质沉着,并有动脉中层的还渐退化和钙化。现代细胞和分子生物学技术显示动脉粥样硬化病变是具有平滑肌细胞增生,大量胶原纤维、弹力纤维和蛋白多糖等结缔组织基质形成,以及经细胞内、外脂质积聚的特点。由于动脉内膜积聚的脂质外观黄色粥样,因此称为动脉粥样硬化。动肪硬化会导致血液循环不畅、血流受阻,甚至会导致血管破裂,继而导致各种心脑血管疾病,如冠心病、脑血栓、脑溢血等。 2.动脉硬化发生的原因,主要是现在人们过食(过量饮食)、饱食、美食以及饮食了环境污染中的有害物质所造成的。由于现在人们饮食不当,血液中存在着大量脂肪、糖、蛋白质、重金属等物质,也正是由于血液中存在着这些过多的物质,过多脂质、粘多糖、重金属等物质沉淀于血管壁,形成了动脉硬化病。 3.对于早期的动脉硬化病患者,大多数患者几乎都没有任何临床症状,都处在隐匿状态下潜伏发展。 4.对于中期的动脉硬化的病患者,大多数患者都或多或少有心悸、心慌、胸痛、胸闷、头痛、头晕、四肢凉麻、四肢酸懒、跛行、视力降低、记忆力下降、失眠、多梦等临床症状,不同的患者会有不同的症状。此时,做许多常规的医学检查如心电图、血脂、血流变、脑电图、脑血量等,都查不出什么病变。临床医师大都让患者不以为然、无大妨碍,不了了之。这让患者又继续病入膏盲。 5.对于晚期的动肪硬化病患者,大多数患者都已发展成了心绞痛、心肌醒塞、脑卒中、肾动脉硬化等病症,常规的医学检查就很容易检查出了。这时,临床医师再为患者开了许多降脂、降压增加心肌供氧功能等药物,进行对症治疗,比如让高血压患者终年服用降压药、高血脂患者张年服用降脂药等,这些对逆转病情已无能为力了,着时光的流逝而病这终究会一天天加重,直至病入膏盲而死亡于高血压、冠心病等心血管疾病,以及其它的疾病,同时也包括其它的许多种常见的多发病、慢性病,采用西医西药,十有八九都是治不好的,只是对症治疗,病因治疗十分困难,主样病魔无情地夺走了许多患者的宝贵生命。 二、防治要点 1.控制热量:摄入的热量必须与消耗的热量相平衡,要通过合理平衡膳食和加强体力活动,把这种平衡保持在标准体重范围内。 2.低脂饮食:少食动物油,代之以植物油,如豆油、花生油、玉米油等,用量为每人每日25号,每月在750克以内为宜。要限制食物中的胆固醇量,每日每人应在300毫克以内。蛋黄以及肝、肾等动物内脏中脂肪含量较高,应少信用。 3.低糖饮食:限制精制糖和含糖类的甜食,包括点心、糖果和饮料的摄入。随着饮料工业的发展,各种含糖类饮料不断增加,当过多饮用含糖饮料时,体内的糖会黑心化成脂肪,并在体内蓄积,不公会增加体重,而且会增设血粮、血脂及血液粘稠度,对动脉硬化的恢复极为不利,所以也要控制饮料的应用。现在一些厂家生产的保健型饮料,用一些甜味物质来声价十倍代蔗糖,既满足了喜好甜食者的口感,又不会给机体增加负担,受到了人们的普遍欢迎。 4.低盐饮食:动脉硬化病人往往合并高血压,因而要采用低盐饮食,每日食盐不要超过5克,在烹调后加入盐拌匀即可。如果在烹调中放入盐,烹调出来的菜仍然很淡,难以入口,为了增加食欲,可以在炒菜时