107 Woodlot Devolution in Northern Ethiopia Opportunities for Empowerment, Smallholder Inco

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:261.96 KB

- 文档页数:47

tpo32三篇托福阅读TOEFL原文译文题目答案译文背景知识阅读-1 (2)原文 (2)译文 (5)题目 (7)答案 (16)背景知识 (16)阅读-2 (25)原文 (25)译文 (28)题目 (31)答案 (40)背景知识 (41)阅读-3 (49)原文 (49)译文 (53)题目 (55)答案 (63)背景知识 (64)阅读-1原文Plant Colonization①Colonization is one way in which plants can change the ecology of a site. Colonization is a process with two components: invasion and survival. The rate at which a site is colonized by plants depends on both the rate at which individual organisms (seeds, spores, immature or mature individuals) arrive at the site and their success at becoming established and surviving. Success in colonization depends to a great extent on there being a site available for colonization – a safe site where disturbance by fire or by cutting down of trees has either removed competing species or reduced levels of competition and other negative interactions to a level at which the invading species can become established. For a given rate of invasion, colonization of a moist, fertile site is likely to be much more rapid than that of a dry, infertile site because of poor survival on the latter. A fertile, plowed field is rapidly invaded by a large variety of weeds, whereas a neighboring construction site from which the soil has been compacted or removed to expose a coarse, infertile parent material may remain virtually free of vegetation for many months or even years despite receiving the same input of seeds as the plowed field.②Both the rate of invasion and the rate of extinction vary greatly among different plant species. Pioneer species - those that occur only in the earliest stages of colonization -tend to have high rates of invasion because they produce very large numbers of reproductive propagules (seeds, spores, and so on) and because they have an efficient means of dispersal (normally, wind).③If colonizers produce short-lived reproductive propagules, they must produce very large numbers unless they have an efficient means of dispersal to suitable new habitats. Many plants depend on wind for dispersal and produce abundant quantities of small, relatively short-lived seeds to compensate for the fact that wind is not always a reliable means If reaching the appropriate type of habitat. Alternative strategies have evolved in some plants, such as those that produce fewer but larger seeds that are dispersed to suitable sites by birds or small mammals or those that produce long-lived seeds. Many forest plants seem to exhibit the latter adaptation, and viable seeds of pioneer species can be found in large numbers on some forest floors. For example, as many as 1,125 viable seeds per square meter were found in a 100-year-old Douglas fir/western hemlock forest in coastal British Columbia. Nearly all the seeds that had germinated from this seed bank were from pioneer species. The rapid colonization of such sites after disturbance is undoubtedly in part a reflection of the largeseed band on the forest floor.④An adaptation that is well developed in colonizing species is a high degree of variation in germination (the beginning of a seed’s growth). Seeds of a given species exhibit a wide range of germination dates, increasing the probability that at least some of the seeds will germinate during a period of favorable environmental conditions. This is particularly important for species that colonize an environment where there is no existing vegetation to ameliorate climatic extremes and in which there may be great climatic diversity.⑤Species succession in plant communities, i.e., the temporal sequence of appearance and disappearance of species is dependent on events occurring at different stages in the life history of a species. Variation in rates of invasion and growth plays an important role in determining patterns of succession, especially secondary succession. The species that are first to colonize a site are those that produce abundant seed that is distributed successfully to new sites. Such species generally grow rapidly and quickly dominate new sites, excluding other species with lower invasion and growth rates. The first community that occupies a disturbed area therefore may be composed of specie with the highest rate of invasion, whereas the community of the subsequent stage may consist of plants with similar survival ratesbut lower invasion rates.译文植物定居①定居是植物改变一个地点生态环境的一种方式。

语法填空名校模拟真题强化练(2024·江西九江·二模)阅读下面短文,在空白处填入1个适当的单词或括号内单词的正确形式。

On Feb 8, 2001, workers at a construction site in Jinsha village, Chengdu, found many pieces of ivory and jade and the hidden ruins of the capital of the ancient Shu Kingdom were brought 1 light by archaeologists. Among the over 5,000 precious relics 2 (excavate)from the ruins, the most eye-catching is the Golden Sun Bird. It is made from delicate gold foil(箔), just one 3 (five)of a millimeter thick. It has two sections: The center is a sun pattern with 12 rays 4 (indicate)the rotation(自转)of the sun and around the sun are four birds flying anticlockwise. According to archaeologists, the four birds symbolize four seasons, while the 12 rays 5 (mean)to represent 12 months of the year. Hence, it could be inferred that over 3000 years ago ancient Shu people possessed 6 good knowledge of astronomy and nature. Furthermore, this masterpiece is believed to be an illustration of an ancient Chinese myth recorded in the classic The Legends of Mountains and Seas, 7 was written about 2,500 years ago. According to the book, ancient people believed the sun was carried up 8 down by birds daily.In 2005, the pattern was 9 (successful)selected as the symbol of China’s cultural heritage to showcase the ancient Chinese people’s 10 ( wise)and aspirations.(2024·山东·模拟预测)阅读下面短文,在空白处填入1个适当的单词或括号内单词的正确形式。

024《名家名作》·评论[摘 要] 利奥波德是现代生态学领域的先驱,他的大地伦理思想内涵丰富,号召将伦理观念拓展到土地以及植物和动物等生物之中,土地应被看作有机体,不再是“死”的。

利奥波德通过这种拓展,开始了他的大地伦理论述,在他的著作《沙乡年鉴》中以一种全新的自然观透视人与自然的关系。

利奥波德强调了人类应将自然界视为道德共同体的成员,强调人与土地的关系是一种伦理关系,而且认为人只有具备生态良知与意识才能更好地尊重和维护自然生态系统的完整性。

利奥波德的大地伦理中蕴含着整体主义思想,通过研究利奥波德的土地伦理观,不仅可以深化我们对人与自然的理解,而且可以为环境保护运动提供理论支持。

[关 键 词] 利奥波德;大地伦理;生态良知;整体主义利奥波德的大地伦理观李秀琳利奥波德生活的年代,工业化快速发展,是环境问题愈发突出的时期,为了应对环境挑战,许多学者提出了各种环境保护的理论和观点,在此期间利奥波德以一种全新的视角提出了大地伦理的观点,重新定义了人与土地的关系。

利奥波德认为我们对待土地不仅要从总体上去尊重它,把它当成一个可供使用的东西,而且要把它当成一个具有生命的东西,具有自己的内在价值。

利奥波德的著作《沙乡年鉴》《寂静的春天》与《增长的极限》一同被认为是环境保护主义三部曲。

利奥波德的大地伦理观,强调将自然环境视为一个整体,人类只是一部分,并非中心,他的这一观点从伦理上对环境的保护具有重要的指导意义,是一种新的尝试和实验,改变了人们对自然的看法以及对待自然的态度。

一、人与土地的伦理关系(一)土地共同体利奥波德是从奥德修斯的故事开始论述其大地伦理观点的,他看到了人类道德身份的演化,在奥德修斯那里奴隶被当作私有财产,他绞死自己奴隶的行为无所谓道德或者不妥当,自从奴隶制被废除之后,利奥波德认为道德身份已经拓展到全部人类,甚至应更进一步将伦理拓展到土地。

伦理规范的演变一般也是哲学家所研究的问题,利奥波德认为它实际也是一个生态进化的过程。

新闻听力模拟练习100题News Item 1Questions 1 to 2 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.1. What crime have the two police officials in Argentina阿根廷been convicted (给…定罪)of?A.They have been convicted of corruption.B.They have been convicted of baby abduction.C.They have been convicted of bribery.D.They have been convicted of military dictatorship.2. We can infer from the news that the sentence would set a precedent惯例for an attempt to ____.A.stop military dictatorshipB.bring senior officials to trialC.stop baby abductionD.make new constitutes for Argentine courtsNews Item 2Questions 3 to 4 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.3. Lloyds of London was charged by a group of African Americans NOT for ____.A.providing insurance for ships which brought African slaves to AmericaB.aiding the commission of genocide(种族屠杀)C.participating in enslaving African AmericansD.refusing to provide insurance to African Americans4. We can infer from the news that if the claimants(原告)want to win the case,they should first____.A.identify their own as descendants from slavesB.provide the evidence that Lloyds of London was responsible for genocideC.Provide the evidence that Lloyds of London participated in slave tradingD.buy insurance from the Lloyds of LondonNews Item 3Questions 5 to 6 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.5. What does the United Nations require the Turkish Cypriots to do?A.To allow Greeks to come back to Cyprus塞浦路斯(地名).B.To give up some territory领土.C.To expel驱赶the Greeks from Turkish.D.To sign a peace contract with Greeks.6. According to the BBC correspondent通讯员, the Greeks are worried that Annanhas offered too much to the ____ side.A. GreekB. Greek CypriotC. Turkish CypriotsD. the UNNews Item 4Question 7 is based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 5 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.7. What can we learn from news?A.Two Iraqi terrorists killed a journalist working for the Arab satellitetelevision station.B.Two Iraqi journalists working for the Arab satellite television stationwere killed by the US troops.C. A bomb attacked the Arab satellite television station and killed two Iraqijournalists.D. A bomb attacked the Arab satellite television station and killed two USjournalists.News Item 5Questions 8 to 9 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.8. How long will the American airplane carrier stay in Hong Kong?A. 7 days.B. 6 days.C. 5 days.D.4 days.9. Which of the following is TRUE about the American spy plane?A.China refused to let it land in Hong Kong.B.America said it was a normal training flight.C.It crashed with Chinese fighter plane on April 3rd.D.It crashed over the South China Sea.News Item 6Questions 10 to 11 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.10. How many people died in the clashes between Iraqi demonstrators示威者and US troops?A. More than 8.B. More than 13.C. More than 30.D. More than 38.11. According to the news, despite Iraq’s overall instability不稳定, the United States decided to ____.A.send more troops to IraqB.hand over power to Iraq peopleC.withdraw its troops from IraqD.continue controlling Iraqi governmentNews Item 7Questions 12 to 13 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.12. Who did the former创造者chief weapons inspector of the UN criticize?A. Tony Blair.B. George Bush.C. Hans Blix.D. Saddam Hussein.13. What can we infer from the news?A.The US and Britain have made a thorough彻底地examination onweapons before they started war.B.The Un weapons inspection检查has been in abeyance中止because ofthe war.C.The US and Britain have found evidence that Iraq owned some atomicweapons.D.Hans Blix was criticized for giving wrong intelligence(information)about weapons in Iraq.News Item 8Questions 14 to 15 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.14. How many tons of nuclear equipment has been sent to the United States from Libya?A. 5tons.B. 50 tons.C. 500 tons.D. 5000 tons.15. The equipment includes the followings EXCEPT____.A.Uranium铀development centersB.ling distance missilesC.guided missilesD.nuclear warhead核弹头News Item 9Questions 16 to 17 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.16. How many people died during the gun battle?A. 9B. 31C. 40D. more than 4017. What is the possible cause of the gun battle?A.Some gunmen tried to flee from the coalition position.B.Some gunmen tried to attack a coalition position.C.The coalition troops accidentally killed some suspected militants.D.Some Afghan militants tried to cross the border with Pakistan.News Item 10Questions 18 to 19 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item,you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.18. American Secretary of State Collin Powell will visit the following countries EXCEPT ____.A. IndiaB. PakistanC. AfghanistanD. Thailand19. Mr. Powell urges the Pakistani government to give evidence that ____.A.it has stopped the trade of nuclear weapons technology with othercountriesB.it has taken steps to the renewed peace process with IndiaC.it has deployed the troops to the border with IndiaD.it has completely abandoned nuclear weapons researchNews Item 11Questions 20 to 22 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 15 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.20. Why have protesters demonstrated证明in several cities?A.They are demanding that the government increase wages.B.They are demanding that the government of Prime Minister resign.C.They are demanding that the government of Prime Minister increasepeople’s living standard.D.They are demanding that the government of Prime Minister improvemultinational relations.21. How many demonstrators are there in Ankara?A. 20,000B. 40,000C. 60,000D. 70,00022. How many people were injured in the protests?A. More than 100.B. More than 1,000.C. More tan 2,000.D. More than 4,000.News Item 12Questions 23 to 24 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.23. According to the officials, when would the economic or other restrictions against Syria be carried out?A. In November.B. This month.C. Next November.D. Not known.24. We can infer from the news that the U.S is considering restrictions against Syriaprobably because____.A.Syria permits fighters to cross its borders into IraqB.Syria continues its nuclear corporation协会with IranC.Syria provides economic help for Iraqi militantsD.Syria doesn’t accept nuclear weapons inspectionNews Item 13Questions 25 to 26 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.25. Which of the followings is NOT the content of the agreement?A.The Mexican travelers are permitted to enter America without beingphotographed.B.The Mexican travelers can travel into America with only identificationdocuments.C.The Mexican travelers can travel to America much more convenientlythan before.D.The restrictions on all Mexicans visiting the United States will be eased.26. What can we infer from the news?A.President Bush supports this agreement.B.Congress has voted on the agreement.C.Mexican President shows no interests in this agreement.D.There will be an election next year.News Item 14Questions 27 to 28 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.27. Who is the speaker in the sound recording?A.Ayman al-Zawahiri.B.Osama Bin Laden.C.Pervez Musharraf.D.George Bush.28. The sound recording urges all Muslims in Pakistan to do the followings EXCEPT____.A.to overthrow推翻the government of the current PresidentB.to oust驱逐the Pakistani leader who is working with the United StatesC.to stop fighting Al-Qaeda militants and their supportersD.to leave Pakistan for AfghanistanNews Item 15Questions 29 to 31 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 15 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.29. Why does China oppose an American missile defense system?A.Because the missile defense system violates违反an internationalanti-missile treaty条约.B.Because the missile defense system would threaten the balance of powerin the East Asia area.C.Because the missile defense system would threaten the peace of China.D.Because the missile defense system would threaten the peace of the world.30. Why does the United States want the missile defense system?A.The United States wants the missile defense system to protect it and itsallies同盟国from attacks by rebel countries.B.The United States wants the missile defense system to fight againstterrorism.C.The United States wants the missile defense system to protect the world.D.The United States wants the missile defense system to develop the space.31. What is Russian’s idea to the missile defense system?A.The missile defense system is useful to the world peace.B.The missile defense system is harmful to the world peace.C.The missile defense system violates an international anti-missile treaty.D.The missile defense system threatens the safety of Russia.News Item 16Questions 32 to 33 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.32. How many days does Colombia President Alvaro Uribe plan to visit the US?A. Two days.B. Three days.C. Four days.D. Five days.33. Which of the followings is NOT the topic of the meetings between the two presidents?A. Trade.B. Terrorism.C. Illegal drugs.D. Nuclear weapons.News Item 17Questions 34 to 35 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.34. What have NASA scientists discovered on Mars?A.Evidence of life.B.Evidence of water.C.Evidence of oxygen.D.Evidence of human beings.35. What will the NASA scientists do next?A.To study opposite sides of Mars.B.To come back to the earth from the Mars.C.To publicize the discovery to the world.D.To suspend the current exploration on Mars.News Item 18Questions 36 to 37 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.36. Where were the talks between President Bush and Indian Prime Minister Man Mohan Singh?A. In Washington.B. In Bombay.C. In New York.D. In New Delhi.37. What has President Bush announced?A.To create full energy cooperation with India.B.To stop providing nuclear technology to India.C.To change the nuclear non-proliferation不扩散treaty.D.To start United Nation’s inspections on India’s nuclear weapons.News Item 19Questions 38 to 39 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.38. What’s the result of the vote held on Thursday?A.El Salvador would withdraw their troops from Iraq.B.El Salvador would stop financial aid on Iraq.C.El Salvador would extend it military work in Iraq.D.El Salvador would send more than 350 soldiers to Iraq.39. What’s special with El Salvador?A.It is the last country to send troops to Iraq in 2003.B.It is the first country to send troops to Iraq in 2003.C.It is the only Latin country that still has troops in Iraq.D.It is the only Latin country which is against the Iraq war.News Item 20Questions 40 to 41 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.40. What happened on Friday?A. 4 suspects tried to make a bombing in London.B.Police raid took place in London and Rome.C.The suspects were tried in the highest court of Rome.D.There is still one suspect from Eritrea hasn’t been captured.41. What is the nationality of Osman Hussein, the suspect arrested in Rome?A. Somali.B. Italian,C. British.D. Iraqi.News Item 21Questions 42 to 44 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 15 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.42. Thailand is Asia’s biggest production base for____.A. copied CDsB. copies VCDsC. pirated CDsD. pirated VCDs43. How many illegal CDs were exported?A. 50 million.B. 60 million.C. 30 millionD. 2 million44. There was a seminar研究小组on ____.A. trade markB. production rightC. registered rightD. property rightNews Item 22Question 45 is based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 5 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.45. According to the news, the expedition远征will attempt to show that____.A.Denmark is geologically linked to Lomonosov RidgeB.Greenland is geologically liked to Lomonosov Ridge.C.Denmark is geologically linked to Greenland.D.Denmark is part of Greenland.News Item 23Questions 46 to 47 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.46. What should be blamed for the crash?A.Terrorist attacks.B.U.S. sanctions惩罚.C. A lack of spare parts.D. A lack of regular maintenance维护.47. Which CANNOT be learned about the crash?A.There were 115 passengers on board.B.The plane crashed on Tuesday.C.The plane crashed shortly after take-off.D.Only one passenger survived the crash.News Item 24Questions 48 to 49 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.48. How many people have been killed in the accident?A. More than 7.B. More than 43.C. More than 100.D. More than 143.49. Which of the followings is NOT true according to the news?A. A series of bombings took place in the town of Sharm el- Sheikh.B.The attacks on Saturday included 7 bombs.C.The bombers involved in the accident have been captured.D.Two hotels and a market ere reported to be badly damaged.News Item 25Questions 50 to 51 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.50. Who was accused of official wrongdoing and bribery?A.The former Prime Minister of Burma.B.Khin Nyunt.C.Khin Nyunt’s sons.D.All of the above.51. What’s the possible sentence given to Khin Nyunt?A.House arrest.B.Death penalty.C.Prison arrest.D.Ouster punishment.News Item 26Questions 52 to 53 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.52. How many people have been reported dead in the series of bomb attacks?A. More than 9.B. More than 19.C. More than 20.D. More than 29.53. Which of the following places hasn’t been attacked by the bombs?A. Mosiedia.B. Baghdad.C. Tecook.D. Havja.News Item 27Questions 54 to 55 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.54. Where is the town of Afar located?A.On the border between Iraq and Syria.B.On the border between Iraq and Iran伊朗.C.On the border between Iraq and Turkey.D.On the border between Iraq and Kuwait科威特.55. Why did Iraqi militants threaten to kill a Turkey citizen?A.To threaten Turkey government to stop cooperating with the U.S.B.To threaten the U.S. troops to retreat from Iraq.C.To threaten the Turkish troops to retreat from Iraq.D.To force Turkey to cooperate with Iraq.News Item 28Questions 56 to 57 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.56. How many people lived in extreme poverty in sub-Saharan Africa in 1981?A.37% of all the people thereB.42% of all the people thereC.45% of all the people thereD.47% of all the people there57. What happened to the number of people worldwide living in extreme povertyover the past 20 years?A.The number has fallen to 19%(下降到19%.)B.The number has fallen to 20%.(下降到20%)C.The number has fallen by 19%.(下降了19%)D.The number has fallen by 20%.(下降了20%)News Item 29Questions 58 to 59 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.58. What is the main idea of this news item?A.Italy decided to increase anti-terrorism measures.B.Italy would prohibit training people to use explosives for terrorismpurpose.C.The deadly bombings in London earlier shocked Italian government.D.Some Italians participated the terrorist bombings in London.59. What is the attitude of the Italian Prime Minister towards the measures?A. Supportive.B. Neutral.C. Unclear.D. Opponent.News Item 30Question 60 is based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 5 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.60. What can be inferred from the news?A.Ivory trading is prohibited in Spain.B.Most of the seized ivory is not legally bought.C.The ivory came from 4000 African elephants.D.The workshop owner was caught smuggling走私.News Item 31Questions 61 to 62 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item,61. What is the possible sentence if the Muslim man is found guilty?A.He would be sentenced to death.B.He would be sentenced to life imprisonment.C.He would be sentenced to probation.D.He would be set free.62. According to the news, we can infer that____.A. a defendant can’t defend himself at a trial under Dutch lawB.the suspect didn’t adm it his crimeC.the murder probably resulted from racial problemsD.the filmmaker died just before the film he made releasedNews Item 32Questions 63 to 64 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.63. How will UNICEF help the African children?A.Build more schools in Africa.B.Reduce school fees in Africa.C.Return them to school provide them with food and housing.D.Provide them with food and housing.64. Extra money is needed to help____.A.African childrenB.Sudanese childrenC.African refugees难民D.Sudanese refugeesNews Item 33Questions 65 to 66 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.65. What is the journalist accused of?A.Working for the British newspaper.B.Objecting to the new media laws.]C.Violating the Zimbabwean laws.D.Publishing an untrue story.66. Which of the following is NOT true about the journalist?A.He is an American-born journalist.B.He works for the Guardian.C.He finished the story with other journalists.D.His story was not published in Zimbabwe.News Item 34Questions 67 to 68 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item,67. What happened after the disputed parliamentary election?A.The anti-government protesters fired on the Prime Minister.B.The security forces killed at least 36 people.C.The opposition leaders refused to meet with the Prime Minister.D.Two main opposition leaders was injured in the collision.68. How many seats do the opposition groups have in the elections?A. 117.B. 170.C. 236.D. 263. News Item 35Questions 69 to 70 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.69. According to the finance and development officials, what is primary goal to beachieved in the new millennium?A.To solve poverty related problems.B.To curb green house gas emission.C.To populate the primary education.D.To solve the energy related problems.70. Which of the following countries hasn’t been mentioned that the povertyproblem still deteriorates?A. Middle East.B. Africa.C. South Asia.D. Latin America.News Item 36Questions 71 to 72 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.71. What is the date set for the trial of Saddam Hussein?A. Last December.B. This December.C. Last Tuesday.D. Not decided yet.72. What is the possible reason for the attacks?A.To inspire a prison breaker uprising.B.To rescue Saddam Hussein.C.To express the dissatisfaction with the trial.D.To condemn Saddam’s regime政治制度.News Item 37Questions 73 to 74 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.73. What was the original record?A.About 25.86 seconds.B.About 30.86 seconds.C.About 32.86 seconds.D.About 35.86 seconds.74. The old man owed his success to ____,.A.Intensive强烈的exercisesB.physical healthC.balanced dietD.good luckNews Item 38Questions 75 to 76 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.75. What happened to the Cubans?A.They set foot in Florida.B.They drowned off the coast of Florida.C.They were taken into custody.D.They were sent back to Cuba.76. What comments can be made on their way of getting into the U.S.?A.It’s the most common way.B.It’s the most successful way.C.It’s the most unusual way.D.It’s the least expensive way.News Item 39Questions 77 to 78 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.77. Where is former President Calos Mannan now?A. In Chile.B. In Argentina.C. In prison.D. In the U.S.78. What can we learn from the news item?A.Argentine former President has been convicted of corruption.B.Mr. Mannan is suspected to have committed corruption during theconstruction of 2 prisons.C.Mr. Mannan will be sentenced to 2-year imprisonment.D.Mr. Mannan has denied all the accusation.News Item 40Questions 79 to 80 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.79. What is NOT a purpose of the satellite?A.To monitor Beijing’s construction.B.To monitor Beijing’s environment.C.To monitor Beijing’s traffic condition.D.To monitor possible terrorist activity in Beijing.80. What will be the speed of the satellite?A.It will orbit the earth every 600 minutes.B.It will orbit the earth every 100 minutes.C.It will orbit the earth every 190 minutes.D.It was not mentioned in the news.News Item 41Questions 81 to 82 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.81. How long has the Indonesian forest been on fire?A. Six months.B. Over a year.C. Almost one year.D. Six years.82. The fires have caused direct or indirect losses in all of the following areasEXCEPT ____ as mentioned in the news.A.heavy industryB.medicineC.tourist industryD.agriculture outputNews Item 42Questions 83 to 85 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 15 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.83. What are delegates calling for?A.Canceling international trade talks.B.Speeding international trade talks.C.Putting off the meeting of international trade delegations.D.Promoting trade relations between China and other Asian countries.84. How many Asian or Pacific countries made the call at the opening?A. 13.B. 15.C. 20.D. 35.85. According to Colin Powell, what is the best way to make the delegates reach an agreement?A. Cooperation.B. Competition.C. Unity.D. Making concessions.News Item 43Questions 86 to 87 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.86. Former President Ronald Reagan’s funeral will be held on ____.A. FridayB. ThursdayC. WednesdayD. Tuesday.87. Which of the following statements is TRUE about Reagan?A.Former President Reagan died at the age of 92.B.Mr. Reagan began to serve as President in 1980.C.Mr. Reagan’s body will be carried to Washington from California.D.Mr. Reagan died in Washington.News Item 44Questions 88 to 89 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.88. Where did the explosion take place?A.At a wedding hall.B.At a petrol station.C.In a downtown shopping center.D.Near the Turkish Health Ministry.89. How many people have been injured?A. A dozen.B. At least one hundred.C. Over one hundred.D. Two hundred.News Item 45Question 90 is based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 5 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.90. How many ballots from the voting have been declared not legal?A. 3,000.B. 13,000.C. 30,000.D.300,000.News Item 46Questions 91 to 92 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.91. What is the purpose of the United States to send more military employees to Haiti?A.To help the newly-established government repress the possible rebels.B.To support former President back to power.C.To help the new government choose a new council.D.To secure the newly appointed council.92. Which of the following word can best describe the current situation of Haiti?A. Quiet.B. Instable.C. Optimistic.D. Promising.News Item 47Questions 93 to 94 are based on the following news. At the end of the news item, you will be given 10 seconds to answer the question. Now listen to the news.93. Who was H.G. Wells?A. A pioneer.B. A writer.C. A doctor.D. A researcher.94. What causes the problem of having internal organs in wrong order?。

2007英语一text3 -回复题目:生活中的互联网[2007英语一text3]是关于生活中的互联网的一篇文章。

互联网在过去的几十年里,对人们的生活方式和社会发展产生了深远的影响。

本文将以互联网的发展、应用和影响为主线,一步一步回答题目。

第一部分:互联网的发展互联网最初是冷战时期美国军方为了实现信息的快速通信而建立的。

随后互联网开始融入到学术界和商业领域,并逐渐发展成为了人们日常生活中不可或缺的一部分。

1. 互联网的起源和发展- 在20世纪60年代末,美国军方为了在冷战中维持高效的信息传输系统而开发了互联网。

- 经过几十年的发展,互联网的使用者逐渐从军方和学术界扩大到了普通大众。

2. 互联网的普及- 随着计算机的普及和互联网技术的不断进步,互联网已经成为全球数十亿人的日常生活和工作必需品。

- 我们可以通过互联网获取信息、进行在线购物、社交媒体互动等。

第二部分:互联网的应用3. 互联网的娱乐应用- 互联网为人们提供了丰富多样的娱乐活动,如在线游戏、影视娱乐、音乐、电子书等。

- 人们可以通过互联网轻松找到他们感兴趣的娱乐内容,并与朋友分享。

4. 互联网的商业应用- 互联网为企业提供了广阔的发展机会,如电子商务、在线支付、数字营销等。

- 很多传统企业转型为互联网企业,改变了商业模式和消费者购物方式。

5. 互联网的教育应用- 互联网已经成为教育领域的重要工具,帮助人们获取知识、提升技能。

- 学生可以通过在线课程、教育平台等方式进行远程学习,并与老师和同学进行交流。

第三部分:互联网对生活的影响6. 互联网的便利性- 互联网让人们的生活更加方便。

我们可以随时随地通过手机或电脑上网,完成各种任务,如购物、学习、娱乐等。

- 互联网为人们提供了更多的选择和可能性,节省了时间和精力。

7. 互联网的社交影响- 互联网极大地改变了人们之间的交流方式。

社交媒体使得人们可以随时联系朋友和家人,分享生活中的点滴。

- 互联网也提供了一个平台,让人们可以参与到更广泛的社交活动中,结识新朋友,扩展社交圈。

专题04 语法填空(第1期)-2022届旧高考名校英语好题速递分项汇编用单词的适当形式完成短文【2022届东北三省三校(哈尔滨师范大学附属中学东北师大附中辽宁省实验中学)高三第一次联合模拟】阅读下面材料,在空白处填入1个适当的单词或括号内单词的正确形式。

Even as a young boy, Leonardo da Vinci showed promise as an artist. He trained for seven years, and then ___41___(strike) out on his own. Afterwards, he set out ___42___(work) for wealthy men throughout Italy. Leonardo began his career as a painter, but he most often worked as an engineer. One of the reasons was that Italy was ___43___ war, and people needed engineers.After Leonardo’s death, it ___44___(discover) that he had kept many notebooks illustrating his work. Although his notebooks were popular in the royal families, none of ___45___were published until the late 19th century. Until then, few people had had any idea ___46___ they contained.As it has turned out, his notebooks are ___47___ amazing treasure box of drawings, such as airplanes, tanks, robots, and diving ___48___ (equip). Along with these drawings are notes___49___ (describe) his work. Many of these notes are ____50____ (science) in nature, involving his research in many different fields. His notebooks show that he was the greatest artist and scientist of his time.【答案】41.struck42.to work43.at44.wasdiscovered45.them46.what47.an48.equipment49.describing50.scientific【解析】本文是一篇说明文。

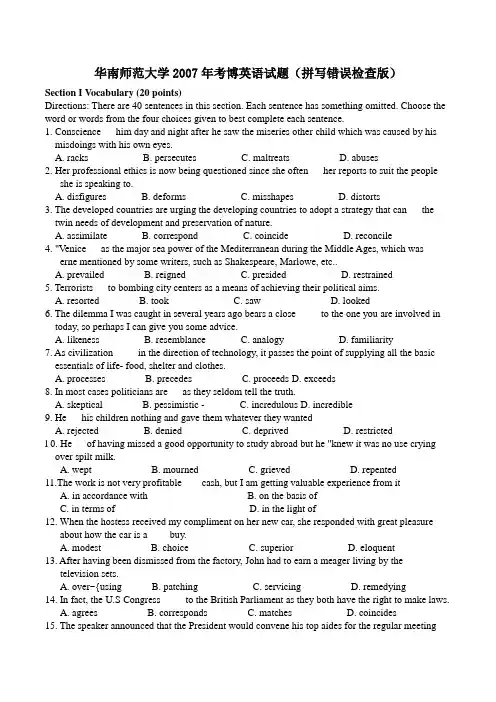

华南师范大学2007年考博英语试题(拼写错误检查版)Section I Vocabulary (20 points)Directions: There are 40 sentences in this section. Each sentence has something omitted. Choose the word or words from the four choices given to best complete each sentence.1. Conscience __ him day and night after he saw the miseries other child which was caused by his misdoings with his own eyes.A. racksB. persecutesC. maltreatsD. abuses2. Her professional ethics is now being questioned since she often __ her reports to suit the peopleshe is speaking to.A. disfiguresB. deformsC. misshapesD. distorts3. The developed countries are urging the developing countries to adopt a strategy that can __ the twin needs of development and preservation of nature.A. assimilateB. correspondC. coincideD. reconcile4. "Venice __ as the major sea power of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages, which waserne mentioned by some writers, such as Shakespeare, Marlowe, etc..A. prevailedB. reignedC. presidedD. restrained5. Terrorists __ to bombing city centers as a means of achieving their political aims.A. resortedB. tookC. sawD. looked6. The dilemma I was caught in several years ago bears a close ____ to the one you are involved in today, so perhaps I can give you some advice.A. likenessB. resemblanceC. analogyD. familiarity7. As civilization ____ in the direction of technology, it passes the point of supplying all the basic essentials of life- food, shelter and clothes.A. processesB. precedesC. proceedsD. exceeds8. In most cases politicians are __ as they seldom tell the truth.A. skepticalB. pessimistic -C. incredulousD. incredible9. He __ his children nothing and gave them whatever they wantedA. rejectedB. deniedC. deprivedD. restrictedl 0. He __ of having missed a good opportunity to study abroad but he "knew it was no use crying over spilt milk.A. weptB. mournedC. grievedD. repented11.The work is not very profitable____cash, but I am getting valuable experience from itA. in accordance withB. on the basis ofC. in terms ofD. in the light of12. When the hostess received my compliment on her new car, she responded with great pleasureabout how the car is a ____buy.A. modestB. choiceC. superiorD. eloquent13. After having been dismissed from the factory, John had to earn a meager living by thetelevision sets.A. over~{usingB. patchingC. servicingD. remedying14. In fact, the U.S Congress ____ to the British Parliament as they both have the right to make laws.A. agreesB. correspondsC. matchesD. coincides15. The speaker announced that the President would convene his top aides for the regular meetingbut he didn't the time and place ..A. designateB. denote "C. manifestD. specify16. The amount of heat produced by this electrical apparatus is --at will by turning a small. handle.A. variableB. variousC. differentD. diverse17. All visitors are requested to with the regulations.A. abideB. complyC. consentD. conform18. I him at Once as an American when he stepped onto the stage with three other actors.A. regardedB. deemedC. spottedD. discerned19. By adapting to your mental condition, you can more in less time.A. complementB. implementC. complimentD. accomplish20. He had to be here at ten o'clock, but because of a traffic accident, he didn't show up untilmidnight.A. overtakenB. undertakenC. guaranteedD. warranted21. When the jury brought in a. of guilt, the defendant who was overwhelmingly arrogantseveral minutes ago drooped his head.A. judgmentB. appraisalC. verdictD. conviction22. He Was. from the competition because he had not complied with the rules.A. forbidden.B. barred ~C. disqualifiedD. excused23. He my authory~, by allowing the children to do things that I have ~'--' ~~,by forbidden.A. impairedB.. disabledC. underminedD. undid24. After completing the big dictionary which was popularly received by readers, this famous scholarset out to compile a. to it.A. complementB. supplementC. accessory 'D. helper25. According to the geological theory put forward by a famous geologist at an academic conference newly held in England, the south of Iceland is to earthquakesA. disposedB. likely:C. liableD. inclined26. At the news, the demonstrators who had put the foreign goods under a boycott for several months protested butA. to naughtB. to nothingC. to no availD. to void27. This country's development of science was greatly undermined for large numbers of scientificwere ejected from their motherland since the dictator came into power.A. galaxyB. eliteC. personnelD. swarm28. The university an honorary doctor's degree on the distinguished scholar who was generally regarded as a credit to his own country.A. donatedB. conferredC. subscribedD. granted29. The people of this country have entrenched themselves to any invaders who refuse to give up their evil intention.A. ward offB. cut offC. work offD. lay off30. The mob was by the fiery speech and then they marched down the main street, and set many Chinese stores on fire.A. wakenedB. aroused ,C. inspiredD. agitated31. The politician is shrewd and deep; he was him. seldom on what he expected others to do forA. transparentB. explicitC. prominentD. conspicuous32. In the eyes of the linguists, there exists no among the languages in the world.A. statusB. scaleC. hierarchyD. gauge33. The radio program was presented a joint venture which was registered several months ago.A. by courtesy ofB. on account ofC. by virtue ofD. in terms of34. Some historians are convinced that Rome was a corrupt kingdom that deserved toA.dieB. expireC. perishD. cease35. In the end they came to the conclusion that the evidence produced by the plaintiff wasA. scarceB. rareC. scantyD. deficient36. The conductor of the orchestra was not satisfied with the ballet for the steps of the dancer wasnot with the rhythm of the music.A. coordinatedB. correspondedC. synchronizedD. reconciled37. It is natural for me to on his motives for the visits for we have not been on speaking termsfor many years.A. reflectB. supposeC. speculateD. meditate38. The president placed a wreath on the monument to the heroes and then made a speech to payto the great achievements of the martyrs.A. complimentB. gratitudeC. tribute.D. commendation39. Bribery the confidence that must exist between buyer and seller.A. aggravatesB. deterioratesC. corrodesD. degenerates40. By evacuating the inhabitants in the densely populated areas of the city and establishing temporary shelters, the city. itself for a possible new quake.A. boltedB. bracedC. reinforcedD. strappedSectionⅡUse of English (20points)Directions: Read the following text. Choose the best word(s) for" each numbered blank and marked A, B, C or D on the answer sheet.The salmon is one of our most valuable fish. It offers us food, sport , and profit. Ever5, ),ear commercial fishing 41 a harvest of over a billion pounds of salmon from the sea. Hundreds of thousands of salmon are caught each year by eager 42 fishers.In autumn, the rivers of the Northwestern United States come 43 with salmon. The salmon have left the ocean and are '44 their yearly run up river to spawn. Yet today, there arefar fewer salmon than 45 because the salmon 46 has suffered from many perils of the modem age.Water pollution has killed many salmon by 47 them of oxygen. Over - fishing has further decreased their numbers. Dams are another 48 because they lock migration paths. Fish ladders, 49 of stepped pools, have been built so that salmon can swim 50 over the dams. But young salmon swimming to the ocean have "trouble 51 the ladders. Often they 52their deaths over the dam or are killed in giant hydroelectric turbines.53 America will continue to have plenty of salmon, conservationists have planned several. lays to 54 the salmon population. Conservation officials have ~had some success 55 salmon in hatcheries and stocking salmon rivers with them. Salmon are also being 56 into new areas. In 1996, hundreds of thousands of young Coho salmon were planted in streams off Lake Michigan. The adults were expected to migrate to the lake and 57 an undesirable fish. The Cohoes 58 so well on this kind of fish in Lake Michigan 59 Cohoes are beingplanted in other Great Lakes.Thanks to the foresight and 60 of conservationists, the valuable salmon should be around American shores, rivers, and lakes for a long time to come41. A. results in B. results from C. results at D. resulted in42. A. commerce B. sports C. salmon D. kindness43. A. alive B. active C. live D. about-44. A. at B. in C. on D. by45. A. ever so B. ever since C. ever after D. ever before46. A. production B. population C. family D. growing47. A. forbidding B. exploiting C. robbing D. endangering48. A. danger B. obstacle C. problem D. element49. A. made up for B. made Up to C. made up D. made up of50. A. properly B. safely C. quickly D. frequently51. A. discover B. to climb C. finding D. measuring52. A. fall to B. fall back C. fall across D. fall away53. A. So that B. So far as C. So much as D. So long as54. A. explode B. develop C. increase D. catch55. A. supporting B. raising C. keeping D. resulting56. A. invaded B. introduced C. found D. given57. A. live on B. feed in C. feed upon D. feed back58. A. activate B. grow C. thrived D. developed59. A. in which B. that C. where D. which60. A. objectives B. planning C. invention D. arrangementSection ⅢReading Comprehension (30 points)Direction: In this part of the test, there are six short passages for you to read. Read each passage carefully, and then do the questions that follow. Choose the best answer A, B, C, or D and mark the corresponding letter on your Answer Sheet.TEXT AIt is frequently assumed that the mechanization of work has a revolutionary effect on the lives of the people who operate the new machines and on the society into' which the machines has been introduced. For example, it has been suggested that the employment of women in industry took them out of the household, their traditional sphere, and fundamentally altered their position in society. In the nineteenth century, when women began to enter factories, Jules Simon, a French politician, warned that by doing so, women would give up their femininity. Friedrich Engels, however, predicted that women would be liberated from the "social, legal, and economic subordination" of the family by technological developments that made possible the recruitment of "the whole female sex into public industry." Observers thus differed concerning the social desirability of mechanization 's effects, but they agreed that it would transform women's lives.Historians, particularly those investigating the history of women, now seriously question this assumption of transforming power. They conclude that such dramatic technological innovations as the spinning jenny, the sewing machine, the typewriter, and the vacuum cleaner have not resulted in equally dramatic social changes in women's economic position or in the prevailing evaluation ofwomen's work. The employment of young women in textile mills during the Industrial Revolution was largely an extension of an older pattern of employment of young, single women as domestics. It was not the change in office technology, but rather the separation of secretarial work, previously seen as an apprenticeship for beginning managers, from administrative work that in the 1880% created a new class of "deadened" jobs, thenceforth considered "women' s work." The increase in the numbers of married women employed outside the home in the twentieth century had less to do with he-mechaniZafi6n of housework and an increase in leisure time for these w0men-than it did with their own economic necessity and with high marriage rates that shrank the available pool of single women workers, previously, in many cases, the only women employers would hire.Women's work has changed considerably in the past 200 years, moving from the household to the office or the factory, and later 5ecoming mostly white-collar instead of blue-coUar work. Fundamentally, however, the conditions under which women work have changed little since before the Industrial Revolution: the segregation of occupations by gender, lower pay for women as a group, jobs that require relatively low levels of skill and offer women little opportunity for advancement all persist, while women's household labor ~remains demanding. Recent historical investigation has led to a major revision of the notion that technology is always inherently revolutionary in its effects on society. Mechanization may even have slowed any change in the traditional position of women both in the labor market and in the home.61. Which of the following statements best summarizes the main idea of the passage?A. The effects of the mechanization of women's work have not borne out the frequently held assumption that new technology is inherently revolutionary.B. Recent studies have shown that mechanization revolutionizes a society's traditional values and the customary roles of its members~C. Mechanization has caused the nature of women's work change since the Industrial Revolution.D. The mechanization of work creates whole new classes of jobs that did not previously exist.62. The author, mentions all of the following inventions as examples of dramatic technological innovations EXCEPT theA. sewing machineB. vacuum cleanerC. typewriterD. telephone63. It can be inferred from the passage that, before the Industrial Revolution, the majority of women's work was done in which of the following settings?A. Textile mills.B. Private households.C. Offices.D. Factories.64. It can be inferred from the passage that the author would consider which of the following to be an indication of a fundamental alteration in the conditions of women's work?A. Statistics showing that the majority of women now occupy white-collar positions.B. Interviews with married men indicating that they are now doing some household tasks.C. Surveys of the labor market documenting the recent creation of a new class of jobs in electronics in which women workers outnumber men four to one.D. Census results showing that working women's wages and salaries are, on the average, as high as those of working men.65. The passage states that, before the twentieth century, which of the following was true of many employers?A. They did not employ women in factories.B. They tended to employ single rather than married women.C. They employed women in only those jobs that were related to women's traditional householdwork.D. They resisted technological innovations that would radically change women's roles in the family.TEXT BPhilosophy in the second half of the 19tb century was based more on biology and history than on mathematics and physics. Revolutionary thought drifted away from metaphysics and epistemology and shifted more towards ideologies in science, politics, and sociology. Pragmatism became the most vigorous school of thought in American philosophy during this time, and it continued the empiricist tradition of grounding knowledge on experience and stressing the inductive procedures of experimental science. The three most important pragmatists of this period were the American philosophers Charles Peirce (1839-1914), considered to be the first of the American pragmatists, William James (1842-1910), the first great American psychologist, and John Dewey (1859 ~ 1952), who further developed the pragmatic principles of Peirce and James into a comprehensive system of thought that he called "'experimental naturalism", or "instrumentalism".Pragmatism was generally critical of traditional western philosophy, especially the notion that there are absolute truths and absolute values. In contrast, Josiah Royce (1855 - 1916), was a leading American exponent of idealism at this time, who beli~.,ved in an absolute truth and held that human thought, and the external world were unified. Pragmatism called for ideas and theories to be tested in practice, assessing whether the), produced desirable or undesirable results. Although pragmatism was popular for a time in Europe, most agree that it epitomized the American faith in know-how and practicality, and the equally American distrust of abstract theories and ideologies. Pragmatism is best understood in its historical and cultural context. It arose during a period of rapid scientific advancement, industrialization, and material progress; a time when the theory of evolution suggested to many thinkers that humanity and society are in a perpetual state of progress. This period also saw a decline in traditional religious beliefs and values. As a result, it became necessary t6 rethink fundamental ideas about values, religion, science, community, and individuality. Pragmatists regarded all theories and institutions as tentative hypotheses and solutions. According to their critics, the pragmatist's refusal to affirm any absolutes carried negative implications for society? challenging the foundations of society's institutions.66. What is this passage primarily about?A. The evolution of philosophy in the second half of the 19tu century.B. The three most important American pragmatists of the late 19a century.C. The differences between pragmatism and traditional western philosophy.D. American pragmatism.67. Which of the following is true?A. Idealism was an important part of the pragmatic approach.B. "Pragmatism" was also known as "traditional western philosophy".C. Pragmatism continued the empiricist tradition.D. Pragmatism is best understood independently o~ its historical and cultural context.68. According to the passage, pragmatism was more popular in America than Europe, becauseA. Americans had ~eater acceptance of the theory of evolutionB. it epitomized the American faith in know-how and practicalityC. Europe had a more traditional society based on a much longer historyD. industrialization and material progress was occurring at a faster pace in America at that time69. All of the following are true EXCEPT ..A. revolutionary thought shifted more towards ideologies in science, politics and sociologyB. pragmatists regarded all theories and institutions as tentative hypotheses and solutionsC. Josiah Royce was not a pragmatistD. pragmatism was based on the theory of evolution70. Which of the following can be inferred from the passage?A. Josiah Royce considered Charles Peirce to be challenging the foundations of society's institutions.B. Charles Peirce considered Josiah Royce to be too influenced by the theory of evolution.C. John Dewey would not have developed his system of thought called "experimental naturalism" or "instrumentalism" without the pioneering work of Charles Peirce and William James.D. Josiah Royce was a revolutionary thinker.TEXT CMass transportation revised the social and economic fabric of the American city in three fundamental ways. It catalyzed physical expansion, it sorted out people and land uses, and it accelerated the inherent instability of urban life. By opening vast areas of unoccupied land for residential expansion, the omnibuses, horse railways, commuter trains, and electric trolleys pulled settled regions outward two to four times more distant from city centers than they were in the premodern era. In 1850, for example, the borders of Boston lay scarcely two miles from the old business district; by the turn of the century the radius extended ten miles. Now those who would afford it could live far removed from the old city center and still commute there for work, shopping, and entertainment. The new accessibility of land around the periphery of almost every major city sparked an explosion of real estate development and fueled what we now "know as urban sprawl. Between 1890 and 1920, for example, some 250,000 new residential lots were recorded within the borders of Chicago, most of them located in outlying areas. Over the same period, another 550,000 were plotted outside the city limits but within the metropolitan area, Anxious to take advantage of the possibilities of commuting, real estate developers added 800,000 potential building sites to the Chicago region in just thirty years--lots that could have housed five to six million people.Of course, many were never occupied; there was always a huge surplus of subdivided, but vacant, land around Chicago and other cities. These excesses underscore a feature of residential expansion related to the growth of mass transportation: urban sprawl was essentially unplanned. It was carried out by thousands of small investors who paid little heed to coordinated land use or to future land users. Those who purchased and prepared land for residential purposes, particularly land near or outside city, borders where transit lines and middle-class inhabitants were anticipated, did so to create demand as much as to respond to it. Chicago is a prime example of this process. Real estate subdivision there proceeded much faster than population growth.71. With which of the following subjects is the passage mainly concerned?A. Types of mass transportation.B. Instability of urban life.C. How supply and demand determine land use.D. The effects of mass transportation on urban expansion.72. The author mentions all of the following as effects, of mass transportation on cities EXCEPTA. growth in city areaB. separation of commercial and residential districtsC. changes in life in the inner cityD. increasing standards of living73. Why does the author mention both Boston and Chicago?A. To demonstrate positive and negative effects of growth.B. To show that mass transit changed many cities.C. To exemplify cities with and without mass transportation.D. To contrast their rates of growth.74. According to the passage, what was one disadvantage of residential expansion?A. It was expensive.B. It happened too slowlyC. It was unplanned.D. It created a demand for public transportation.75. The author mentions Chicago in the second paragraph as an example of a cityA. that is largeB. that is used as a model for land developmentC. where land development exceeded population growthD. with an excellent mass transportation systemTEXT DA classic series of experiments to determine the effects of overpopulation on communities of rats was reported in February of 1962 in an article in Scieritific American. The experiments were conducted by a psychologist, John B. Calhoun. and his associates. In each of these experiments, an equal number of male and female adult rats were placed in an enclosure and given an adequate supply of food, water, and other necessities. The rat populations were allowed to increase. Calhoun knew from experience approximately how many rats could live in the enclosures without experiencing .stress due to overcrowding. He allowed the population to increase to approximately twice this number. Then he stabilized the population by removing offspring that were not dependent on their too: hers. He and his associates then carefully observed and recorded behavior in these overpopulated communities. At the end of their experiments, Calhoun and his associates were able to conclude that overcrowding causes a breakdown in the normal social relationships among rats, a kind of. social disease. The rats in the experiments did not follow the same patterns of behavior as rats would in a community without overcrowding. .The females in the rat population were the most seriously affected by the high population density: They showed deviant maternal behavior: they did not behave as mother rats normally do. In fact, many of the pups, as rat babies are called, died as a result of poor maternal care. For example, mothers sometimes abandoned their pups, and, without their mothers’care, the pups died. Under normal conditions, a mother rat would not leave her pups alone to die. However, the experiments verified that in overpopulated communities, mother rats do not behave normally. Their behavior may be considered pathologically diseased.The dominant males in the rat population" were the least affected by overpopulation. Each of these strong males claimed an area of the enclosure as his own. Therefore, these individuals did not experience the overcrowding in the same way as the other rats did. The fact that the dominant males had adequate space in which to live may explain why they were not as seriously affected by overpopulation as the other rats. However, dominant males did behave pathologically at times. Their antisocial behavior consisted of attacks on weaker male, female, and immature rats. This deviant behavior showed that even though the dominant males had enough living space, they too were affected by the general overcrowding in the enclosure.Non-dominant males in the experimental rat communities also exhibited deviant social behavior. Some withdrew completely; they moved very little and ate and drank at times when the other rats were sleeping in order to avoid contact with them. Other non-dominant males were hyperactive; they were much more active than is normal, chasing~ other rats and fighting each other. This segment of the rat population, tike all the other parts, was affected by the overpopulation. The behavior of the non-dominant males and of the other components of the rat population has parallels in human behavior. People in densely populated areas exhibit deviant behavior similar to that of the rats in Cal hour,)s experiments. In large urban areas such as New York, London, Mexican City, and Cairo, there are abandoned children. There are cruel, powerful individuals, both men and women. There are also people who withdraw and people who become hyperactive. The quantity of other forms of social pathology such as murder, rape, and robbery also frequently occur in densely populated human communities. Is the principal cause of these disorders overpopulation? Calhoun's experiments suggest that it might be. In any case, social scientists and city planners have been influenced by the results of this series of experiments.76. Paragraph 1 is organized according toA. reasons B examples C. examples D. definition77. Calhoun stabilized the rat populationA. when it was double the number that could live in the enclosure without stressB. by removing young ratsC. at a constant number of adult rats in the enclosureD. all of the above are correct78. Which of the following inferences CANNOT be made from the information in Para. 1A. Calhoun's experiment is still considered important today.B. Overpopulation causes pathological behavior in rat populations.C. Stress does not occur in rat communities unless there is overcrowdingD. Calhoun had experimented with rats before.79. Which of the following behavior didn't happen in this experiment?A. All the male rats exhibited pathological behavior.B. Mother rats abandoned their pups.C. Female rats showed deviant maternal behaviorD. Mother rats left their rat babies alone.80. The main idea of the paragraph three is thatA. dominant males had adequate living spaceB. dominant males were not as seriously affected by overcrowding as the other ratsC. dominant males attacked weaker ratsD. the strongest males are always able to adapt to bad conditionsTEXT EMurovyovka Nature Park, a private nature resize, is the result of the vision and determination of one man, Sergei Smirenski. The Moscow University Professor has gained the support of international funds as well as local officials, businessmen and Collective farms.Thanks to his efforts, the agricultural project is also under way to create an experimental farm to teach local farmers how to farm without the traditionally heavy use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers. Two Wisconsin farmers, Don and Ellen Padley, spent last summer preparing land in Tanbovka district, where the park is located, and they will return this summer to plant it。

Ⅰ.重点单词识记1.civilization /ˌsIvəlaI′zeIʃn/n.文明2.found /faʊnd/v t.兴建,创建3.pour /pɔː(r)/v i.涌流,倾泻;v t.倒出(液体)4.disaster /dI′zɑːstə(r)/n.灾难5.commercial /kə′mɜːʃl/adj.商业的,贸易的6.ruin /′ruːIn/n.废墟;毁坏;v t.破坏,毁灭7.beneath /bI′niːθ/prep.在……之下8.material /mə′tIərIəl/n.材料;物质;adj.物质的9.ceremony /′serəmənI/n.仪式,典礼10.march /mɑːtʃ/v i.&n.前进,进发;游行11.ahead /ə′hed/ad v.(时间、空间)在前面;提前,预先;领先12.corrupt /kə′rʌpt/v t.使腐化,使堕落;adj.贪污的,腐败的13.trial /′traIəl/n.审讯,审理;试验;考验14.unfortunate /ʌn′fɔːtʃənət/adj.不幸的,遗憾的→unfortunately ad v.不幸地,遗憾地,可惜地15.decorate /′dekəreIt/v t.装饰,装潢→decoration n.装饰;装饰品16.destroy /dI′strɔI/v t.毁坏,摧毁→destruction n.毁灭,摧毁17.wealthy /′welθI/adj.富有的,富裕的→wealth n.财富;财产18.cultural /′kʌltʃərəl/adj.文化的→culture n.文化19.remains /rI′meInz/n.遗物,遗迹,遗骸→remain v.保持不变,仍然是;剩余,遗留→remaining adj.剩余的20.explode /Ik′spləʊd/v i.爆炸→explosion n.爆炸,爆裂21.extreme /Ik′striːm/adj.极度的;极端的→extremely ad v.极其;极端;非常22.complain /kəm′pleIn/v i.抱怨→complaint n.抱怨,埋怨;投诉23.solution /sə′luːʃn/n.解决办法,解答→solve v t.解决;解答24.expression /Ik′spreʃn/n.表达;表情,神色;词语→express v t.表示;表达;n.快车;速递25.declare /dI′kleə(r)/v t.宣布,宣称→declaration n.宣布,宣告,宣言26.memorial /mə′mɔːrIəl/n.纪念碑,纪念馆;adj.纪念的→memory n.记忆;记忆力;回忆27.educate /′edʒʊkeIt/v t.教育;训练→educated adj.受过教育的;有教养的→education n.教育→educator n.教育工作者,教师;教育(学)家28.aware /ə′weə(r)/adj.意识到的,知道的;察觉到的→awareness n.意识;认识;知道→unaware adj.没意识到,不知道,未察觉29.judge /dʒʌdʒ/n.法官,审判员;裁判员;v.断定;判断;判决→judgement n.判断力;看法,评价;(法律)判决30.poison /′pɒIzn/n.毒药,毒物;v t.毒害,下毒→poisonous adj.有毒的Ⅱ.重点短语识记1.take over夺取;接管,接替,接任2.be decorated with被装饰3.cut down砍倒;削减;删节4.in good condition状况良好;情况很好5.take place发生;举行6.declare war against/on...对……宣战7.in memory of纪念8.no doubt无疑,确实9.rise up against起义,反抗10.stand in one’s path阻碍某人11.stop sb.(from) doing sth.阻止某人做某事12.come down with患(病)13.think of...as...把……看作……;认为……是……14.have had enough of...受够了……,对……已厌烦透了15.take sb.to court把某人告上法庭Ⅲ.经典原句默写与背诵1.We are in Italy now,and tomorrow we are visiting Pompeii.我们现在在意大利,明天将游览庞贝。

2024年江西景德镇中考英语试题及答案说明:1.本试题卷满分120分,考试时间120分钟。

2.请按试题序号在答题卡相应位置作答,答在试题卷或其它位置无效。

一、听力理解(本大题共20小题,每小题1分,共20分)现在是试听时间。

请听一段对话,然后回答问题。

What is the boy going to buy?A.Some juice. B.Some oranges. C.Some apples.答案是C。

A)请听下面5段对话。

每段对话后有一小题,从题中所给的A、B、C三个选项中选出最佳选项,并在答题卡上将该项涂黑。

听完每段对话后,你都将有10秒钟的时间回答有关小题和阅读下一小题。

每段对话读两遍。

1.What time does Mike get up every day?A.6:30. B.7:00. C.7:30.2.What will the weather be like in Nanchang tomorrow?A.Cloudy. B.Rainy. C.Sunny.3.What color is the cat’s hair?A.Brown. B.White. C.Black.4.What’s the matter with Julie?A.She has a headache. B.She has a toothache. C.She has a stomachache.5.What does Jack mean?A.Soccer is easy. B.He loves soccer. C.The girl is clever.B)请听下面4段对话。

每段对话后有几个小题,从题中所给的A、B、C三个选项中选出最佳选项,并在答题卡上将该项涂黑。

听每段对话前,你将有时间阅读各个小题,每小题5秒钟;听完后,各小题给出5秒钟的作答时间。

每段对话读两遍。

请听第1段对话,回答第6、7小题。

6.What book did Lily buy last week?A.A story book. B.A history book. C.A science book.7.How soon will Lily finish reading it?A.In 3 days. B.In 5 days. C.In 7 days.请听第2段对话,回答第8、9小题。

蒙娜丽莎的微笑中英文对照台词All her life she had wanted to teach at Wellesley College. So when a position opened in the Art History department she pursued it single-mindedly until she was hired.她一生所梦寐以求的便是在韦尔斯利学院执教。

于是,当该校美术历史系有了一个职位后,她便一门心思去实现这个梦想,直至被聘请.It was whispered that Katherine Watson a first-year teacher from Oakland State made up in brains what she lacked in pedigree. Which was why this bohemian from California was on her way to the most conservative college in the nation.本片讲述了凯瑟琳沃森一位来自于奥克兰市仅有一年教学经历的教师,可以想象她是多么不谙世故.这就是为什么这位在加州长大的的波希米亚人会跑到全国最保守的学院任职的原因.-Excuse me, please. -Oh , sorry.-劳驾,请让一下. -哦,抱歉.Excuse me.抱歉Excuse me. The bus?劳驾. 请问公车在哪里乘?-Keep walking, ma'am. -Thank you.-再往前走,女士. -谢谢.But Katherine Watson didn't come to Wellesley to fit in.但是凯瑟琳沃森不仅想成为韦尔斯利学院的一员.She came to Wellesley because she wanted to make a difference.她来韦尔斯利学院是因为想有所作为.-Violet. -My favorite ltalian professor.-维奥莱特. -我们最受欢迎的意大利文教授.-Nice summer? -Terrific, thanks.-暑假过的如何? -棒极了,谢谢. -Who's that over there? -Where?-那边是谁? -哪儿?Oh, Katherine Watson. New teacher. Art History. I'm dying to meet her.噢,凯瑟琳沃森。

令人不安的假设在热带森林道格拉斯Sheil大卫Burslem2 F.R.P.1国际林业研究中心(CIFOR)主任邮政信箱6596 JKPWB、雅加达10065年,印尼2部门的植物和土壤科学,阿伯丁大学,克鲁克香建筑、圣马开车,阿伯丁AB24 3 UU、英国中间扰动假设(IDH)是一个con-troversial解释为维护热带森林的树的多样性,但是它的基于经验的测试是罕见的。

两个数据密集型评估最近产生了矛盾的后果:一个用于和一个反对IDH。

我们建议,解释这些结果体现在细微之处的不同解读和手法,并的不同特点,研究地点。

看似简单的decep IDH是——命题,因为一系列不同的现象是参与,每一种都可以被定义和检查。

最近的进展提供令人兴奋的机会对于深入地理解如何影响森林多样性的干扰。

康奈尔[1]总结了中间扰动假设(IDH;盒1)为―种类最丰富的热带雨林的树木也应该发生在一个中间阶段纷纷在一场大的干扰或与较小的干扰,是无论是非常频繁或罕见的;要么表示一个打开的非平衡‖。

这是否有助于我们理解维护热带森林的树的差异? 经验证据极为稀少,但是最近的两个数据密集型的研究达到对比的结论。

哈贝尔et al。

[2],致力于Barro Colorado岛(BCI)、巴拿马、检查treefall差距在50-ha情节和指出,虽然物种密度增加了差距,这反映了干密度:物种丰富度校正干密度类似于周围的森林,和变化小,气隙的大小。

Molino和萨巴蒂尔[3]的工作,在Paracou,法属圭亚那、量化的物种丰富性(物种每40茎取样)在森林已被砍伐不均十年以前,和使用相对丰富的高光——要求先锋(见术语表)和HELIOPHILE物种作为衡量过去的干扰。

他们发现,在quadrats树苗丰富性与峰值一个heliophiles中间表示的。

一个类似的驼背的关系被发现只有当森林quadrats无日志记录的检查。

这些研究达到不同的结论,尽管相似的样本大小和当地气候(表1)。

39October 2023WHAT began as a dream by the Chinese government 10 years ago has evolved across various parts of the world as a key catalyst for job creation andpoverty eradication, resulting in economic growth and development. As the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) celebrates its 10th anniversary, it has made a global impression as a vast and ambitious infra-By BENARD AYIEKOConnecting the DotsThe Belt and Road Initiative celebrates 10 years of success in Africa.structure development project whose main objec-tive is to connect Africa, Asia, Europe and other regions via a network of roads, railways, ports and other key infrastructural developments.At the inception stage, critics acted like a wet blanket towards the BRI, particularly on realizing that the growing Sino-African relationship was becoming a great force to reckon with. It became a point of ridicule to critics who label it “debt-trap diplomacy” and “debt colonialism.” But far from it, the BRI has witnessed a decade of inclusive infrastructure development programs in more than 150 countries, with more than 30 organiza-tions supporting the initiative actively since it was launched in 2013.Africa has been among the biggest beneficia-ries of the BRI. In fact, statistics indicate that out of the 54 African countries, 52 have either signed or expressed interest to sign the BRI coopera-tion framework agreements and benefited from projects under this initiative, particularly those of roads, energy, ports, and communications infra-The first phase of the Nairobi-Malaba Standard GaugeRailway (SGR), built by a Chinese company, is open to the public in Kimuka, Kenya on October 16, 2019.Copyright ©博看网. All Rights Reserved.40CHINA TODAYSpecial ReportThe future of the BRI in Africa is promising because it is the only surety for continued infrastructural development and increase in trade.PROMISINGstructural development. These projects are meant to open up African countries to trade by facilitat-ing construction of key domestic and regional infrastructure, to help African countries to access affordable energy for industries and to open up efficient and reliable transportation channels for African exports to international markets.Trade BenefitsIn Africa, the benefits of BRI cannot be gain-said. For the last 10 years, trade has been on the front foot. The BRI has advanced steadily through Sino-African consultative forums such as the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation, which have opened up Chinese markets to exports from African countries. These forums are guided by the principles of extensive consultation, joint contribution and shared benefits for policy coor-dination, unimpeded trade, financial integration, facilities connectivity and people-to-people bond.Sino-African relations have seen monumental growth in trade. According to trade statistics from China’s General Administration of Customs, the total trade between Africa and China surpassed the US $2 trillion mark since the BRI was initiated in 2013. In fact, China has been the leading trad-ing partner for Africa. In 2022, the trade volumebetween China and Africa was recorded as US $282 billion, a significant growth of 11 percent com-pared to 2021.Therefore, it should be noted that the BRI has been a major catalyst for growth of trade in most African economies, promoting trade through improved infrastructure. The connectivity cre-ated through construction and upgrading of roads, railways, ports and airports has improved transportation networks significantly by reduc-ing logistical bottlenecks, lowering shipping costs and facilitating free movement of goods not just between Africa and China, but also within the African countries themselves. Additionally, the new infrastructure network on the continent has dismantled barriers to trade by creating trade corridors that connect African countries to global markets. It is these trade corridors that have be-come essential arteries for the free flow of goods, thereby making trade more efficient and cost-effective. This has played a pivotal role in reducing the market prices of these goods on international markets, making African exports competitive. For instance, the construction of the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) in Kenya at a cost of US $3 billion by China has greatlyreduced the time and cost of transporting goodsUltra-large liquefied petroleum gas stor-age tanks, manu-factured by Shidao Heavy Industry, are shipped to Angola along the Belt and Road route from Rongcheng City, east China’s Shan-dong Province on April 11, 2023.Copyright ©博看网. All Rights Reserved.from the port of Mombasa to other parts of the country and the region at large. The SGR has also been a good catalyst for promoting domestic and international tourism by facilitating more con-venient and accessible movement of goods and people.China’s grand plan is to increase its trade with Africa to US $300 billion by 2025. To show com-mitment towards this cause, the Chinese govern-ment has enacted a zero-tariff policy that covers over 8,800 different types of products, including clothes and footwear, agricultural goods and chemicals.Trade MilestonesThe BRI has also opened up the African con-tinent to trade through increased connectiv-ity by way of digitization — encompassing theexpansion of communication networks and the development of digital infrastructure. This has improved communication and access to informa-tion, especially in rural areas, catapulting most businesses to engage in both domestic and cross-border trade.Just last year, the Chinese government waived tariffs on 98 percent of taxable imports from 18 African countries in two batches. This has ush-ered in an era of increased Chinese investments in the continent. In the last 10 years, according to statistics from China’s Ministry of Commerce, investments from China to Africa stood at US $3.4 billion with more than 3,000 companies investing in Africa. The value of newly contracted Chinese enterprises in African countries in the last 10 years exceeded US $700 billion, with completed turnover of over US $400 billion. The BRI has also been instrumental in ensuring development of economic zones and industrial parks along trade corridors in Africa. These zones are major magnets for foreign and domestic investors, thus stimulating manufacturing and processing for infant industries, resulting in creation of employ-ment opportunities for the youth and boosting trade.The BRI has achieved significant trade mile-stones in resolving potential trade impediments. For instance, the BRI has contributed to trade facilitation by improving transportation linksand connectivity, reducing the turnaround trans-actions period and the cost of moving goodsfor trade between African countries. This hasresulted in growth of trade volumes, which hasbenefited both the African economies and China.In addition, the partnership has also led to an in-crease in agricultural output and food security inAfrica. Increase in output has been brought aboutby reduced post-harvest losses, guaranteeing ade-quate production for both domestic consumptionand exports to global markets.The future of the BRI in Africa is promisingbecause it is the only surety for continued infra-structural development and increase in trade.The construction of more roads, railways, portsand energy projects is a sure bet for enhancedconnectivity and trade between African countriesthemselves, and with China. If Africa has to fullyindustrialize and grow its trade fortunes, theindustrialization strategy must align itself to theBRI in order to accelerate special economic zonesand industrial parks, which are good incubatorsof trade, along the BRI corridors to attract moreforeign investment, promote manufacturing andcreate employment opportunities for the youth.The future is bright. CBENARD AYIEKO, a Kenya-based writer, is an economist,lawyer, consultant and a regional commentator on trade andinvestment.After graduatingfrom university in2018, Leah Uwiho-reye founded an e-commerce platformin Rwanda, helpingwomen survivors ofRwandan genocidesell handmadeaccessories.Copyright©博看网. All Rights Reserved.41 October 2023。